Abstract

Background

Daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective HIV prevention strategy, but adherence is required for maximum benefit. To date, there are no empirically supported PrEP adherence interventions. This manuscript describes the process of developing a PrEP adherence intervention and presents results on its impact on adherence.

Methods

The Partners PrEP Study was a placebo-controlled efficacy trial of daily oral tenofovir and emtricitabine/tenofovir PrEP among uninfected members of HIV serodiscordant couples. An ancillary adherence study was conducted at three study sites in Uganda. Participants with <80% adherence as measured by unannounced pill count received an additional adherence counseling intervention based on Lifesteps, an evidence-based HIV treatment adherence intervention, based on principles of cognitive-behavioral theory.

Findings

Of the 1,147 HIV seronegative participants were enrolled in the ancillary adherence study, 168 (14.6%) triggered the adherence intervention. Of participants triggering the intervention, 62% were male; median age was 32.5 years. The median number of adherence counseling sessions was 10. Mean adherence during the month before the intervention was 75.7%, and increased significantly to 84.1% in the month after the first intervention session (p<0.001). The most frequently endorsed adherence barriers at session one were travel and forgetting.

Interpretation

A PrEP adherence intervention was feasible in a clinical trial of PrEP in Uganda and PrEP adherence increased after the intervention. Future research should identify PrEP users with low adherence for enhanced adherence counseling and determine optimal implementation strategies for interventions to maximize PrEP effectiveness.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis, adherence, intervention, serodiscordant couples, HIV prevention

Introduction

Over 34 million people across the globe were living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2011, with an estimated 2.5 million new infections occurring in 2011 alone1. While there have been tremendous advances in developing effective treatments for HIV/AIDS, identifying effective HIV prevention strategies remains of paramount importance as the epidemic enters its fourth decade. Antiretrovirals as HIV prophylaxis (PrEP) may be an important tool in HIV prevention efforts.

Four PrEP trials conducted among individuals with sexual behavior as a primary HIV risk factor have yielded positive results, while two trials were negative. The heterogeneity of these findings has been largely attributed to differences in adherence2. The two trials that did not show efficacy, Fem-PrEP3 and the VOICE trial4, had low adherence based on tenofovir drug levels. While adherence support was provided at monthly visits in all trials, data on the efficacy of the approaches are not available. The positive trials include CAPRISA 0045, the iPrEx trial 6 the CDC TDF2 study7, and the Partners PrEP Study8.

The Partners PrEP Study was a placebo-controlled trial of oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC)/TDF among uninfected members of HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa. The primary trial demonstrated a 67% HIV risk reduction in the TDF arm and a 75% reduction in the FTC/TDF arm.8 Detection of tenofovir in plasma samples was associated with even higher protection from HIV (86% in the TDF arm and 90% in the FTC/TDF arm).9 Adherence across both arms was high (97%) based on clinic-based pill counts. The Partners PrEP Study included an ancillary adherence study in 1,147 participants with objective adherence measures and an intensive adherence counseling intervention was provided for those participants whose adherence dropped <80%. Median adherence was 99.1% based on unannounced pill counts and 97.2% by medication event monitoring system (MEMS); there were no HIV infections among participants who received active drug in the ancillary adherence study, suggesting 100% PrEP efficacy in this subset (95% confidence interval 83.7-100%, p <0.001).9

In summary, the preponderance of evidence to date suggests that TDF or FTC/TDF used as PrEP can be an effective biomedical HIV prevention strategy, given sufficient adherence. While all PrEP efficacy trials included adherence counseling, they were generally designed to support overall adherence to obtain an accurate estimate of PrEP efficacy rather than to specifically evaluate a potential effect of the adherence counseling. There have been no rigorous evaluations of PrEP adherence interventions. The goal of this manuscript is to describe the PrEP adherence intervention delivered in the adherence ancillary study of the Partners PrEP Study and to present data on its usefulness for supporting adherence.

Methods

Partners PrEP Study

The Partners PrEP Study was a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-arm clinical trial of daily oral TDF and FTC/TDF PrEP provided to HIV-uninfected members of 4,758 HIV serodiscordant couples enrolled at nine clinical research sites in Kenya and Uganda, beginning in July 2008. The design, procedures, and outcomes of the Partners PrEP Study clinical trial are described elsewhere.8 Briefly, HIV-uninfected partners were randomly assigned to once-daily TDF, combination FTC/TDF, or matching placebo and followed monthly for safety assessments and HIV seroconversion for up to 36 months. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. After an interim review of study data by the data safety and monitoring board (University of Washington) revealed that pre-specified efficacy bounds had been crossed, efficacy findings were released on July 10, 2011.

Ancillary Adherence Study

Participants were recruited to participate in an ancillary adherence study from one urban (Kampala) and two rural (Tororo and Kabwohe) Ugandan sites of the Partners PrEP Study. The ancillary adherence study was designed to determine the level, pattern, and predictors of PrEP adherence using objective adherence measures (i.e., the medication event monitoring system [MEMS], unannounced pill count, and drug levels) and both quantitative and qualitative data collection. Data on drug levels, overall patterns of adherence, and the qualitative study are reported elsewhere8–10. Another goal was to develop and implement an intervention targeted to HIV-negative participants with low (<80%) unannounced pill count adherence. The threshold value of 80% was chosen based on biologic plausibility based on thresholds for efficacy in macaques11 and is consistent with a level of adherence conferring a high level of protection in the CAPRISA 004 topical tenofovir gel study5, although the exact level of adherence needed to protect against HIV acquisition is unknown. All participants already enrolled or simultaneously enrolling in the parent trial in these three sites were offered participation in the ancillary adherence trial without knowledge of study arm. Participants were asked to complete at least one intervention session with the option to attend additional follow-up sessions. The number of sessions was flexible, and determined by the adherence counselor (based on the needs of the participant) and the participants' preferences.

Goals of the adherence intervention

The intervention is based on work conducted by Safren and colleagues on increasing ART adherence, specifically the Life-Steps intervention.12,13 Life-Steps is a brief adherence intervention that uses general principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and problem-solving therapy 14,15, and was used in two large scale antiretroviral therapy as prevention intervention trials 16,17. The intervention manual was developed to: (1) standardize the provision of information related to adherence while preserving the flexibility to tailor counseling messages to meet the needs of individual participants; (2) allow for delivery by staff members with various levels of training; and (3) provide a reference for future counseling sessions.

Process of intervention development

The intervention was developed over several months using an iterative process. First, six study team members (CP, SS, JEH, DB, KM, ENJ) had informal community advisory meetings with ten participants in the Partners PrEP Study from the Kampala site. Discussions focused on experiences with PrEP use (including beliefs about PrEP and experiences with stigma) and barriers to PrEP adherence, with the goal of learning more about the cultural setting in which PrEP was being used, as well as ways in which adherence to PrEP may vary from adherence to ART. Second, team members reviewed qualitative data examining reasons for adherence among participants, collected as part of the ancillary adherence study from the Kabwohe site.10. Lastly, feedback from the adherence counselors at all three sites was collected as part of monthly supervision calls. This feedback allowed for adaptive intervention design during the first few months of implementation, including the addition of culturally relevant metaphors to explain the concept of adherence, and increasing the counselors' flexibility to skip modules less relevant for individual participants, particularly at follow-up sessions.

Intervention delivery

The intervention manual was divided into sections, each of which is described below. The counselors, who were lay counselors with the equivalent of a high school education, were trained over two days on general counseling skills, the use of CBT strategies in effecting health-related behavior change, and the intervention content. Counselors then participated in supervision calls every four to six weeks with a study investigator (CP), during which time cases were reviewed in detail and feedback on the intervention was provided. Site visits were also conducted for continued training/supervision and problem-solving issues related to intervention delivery.

Description of intervention components

The first intervention session began with information gathering, educational information and rapport building, and later involved motivational interviewing and assistance with specific problem-solving strategies. Because the study population consisted of individuals in HIV serodiscordant partnerships, the intervention was couples-based; the initial portion of the first session was conducted with just the participant taking PrEP, and the second part with both members of the dyad when possible. Subsequent counseling sessions began with a review of prior session content; the skills were then used to target additional barriers to adherence and/or plan for anticipated barriers to adherence. A description of each of the intervention components is provided in Table I.

Table I. Description of intervention components.

| Component | Description and Goals |

|---|---|

| Educational and informational | Opportunities for counselor to gather relevant information (e.g., history of the relationship with the HIV-positive partner, occupation, experiences with PrEP, and expectations for the adherence counseling sessions), provide information about PrEP (e.g., dispel myths about PrEP, explain why adherence is important, and describe the protocol for seroconversion), and orient the participant to the counseling sessions (e.g., highlight that the counseling sessions would focus on adherence to PrEP). Participants' sexual behavior and daily routines as they related to PrEP adherence were also discussed. |

| Motivational interviewing30 | Involved reviewing the pros and cons of achieving high levels of adherence to PrEP. Counselors encouraged to focus on the idea that motivation was dynamic and attempted to resolve any ambivalence about adherence, thus moving participants to a higher level of readiness to adhere. Potential cons were addressed later in the session as part of the problem-solving protocol. |

| Problem solving 13,16 | Involved identifying barriers to PrEP adherence and generating solutions to each identified barrier. For each barrier, counselors encouraged to generate a plan and a back-up plan based on the perceived effectiveness and acceptability of the solution to the participant. Counselors also encouraged to use rehearsal strategies when relevant (e.g., setting cell phone reminders in session, practicing asking for help with adherence). |

| Couples session | Optional (but encouraged), and allowed counselors to address any concerns of the HIV-positive partner around PrEP use, address any relational barriers to adherence, and generate a plan for the HIV-positive partner to support the HIV-negative partner's PrEP adherence. Before this session, counselor and participant reviewed what information could be shared with the partner and what information should be kept private (e.g., details about additional partners or relationships). |

| Follow-up sessions | Optional and provided at the discretion of the counselors. Followed a similar format whereby the prior session content was reviewed, the success of the adherence plan was evaluated and adjusted as necessary, and new barriers to adherence were addressed as needed. |

Measures

Adherence to PrEP

Adherence assessment for participants in the adherence ancillary study was performed using two validated objective measures 18,19. First, pill counts were unannounced (i.e., participants were not informed of the date of the visit) on a randomly selected day every month for the first six months and quarterly thereafter. The random nature of the visit was intended to lessen the chance that participants would manipulate pill bottles (i.e., dump pills) prior to the measurement to appear more adherent than they were. Second, MEMS (Aardex, Switzerland) was used to electronically record the date and time of pill bottle openings; data were downloaded monthly. Unannounced pill count was used to trigger the intervention. MEMS data were used to examine adherence relative to the intervention because the daily frequency of the MEMS measurement allowed for closer linkage of behavior with the intervention than would have been possible with the quarterly summary measures obtained through unannounced visits for pill counts.

Adherence intervention process measure

This measure was completed by the counselor after each intervention session. It tracked the duration of sessions, use of specific intervention modules, barriers to PrEP adherence, and the counselor's assessment of how well a participant was able to implement their adherence plan (follow-up counseling sessions only).

Covariates and descriptive data

Most enrollment characteristics (e.g., age, gender, time to clinic) were collected at enrollment into the ancillary adherence study; data on income, main source of income, marital status, cohabitating status, years cohabitating, years known discordant, and polygamous relationship were collected at parent study enrollment. Socio-economic status (SES) was calculated as a principal components analysis based on the Filmer-Pritchett Index. The index involved the presence of running water, a concrete floor, electricity, a metal roof, a television, and two or more rooms in the residence. 20 Heavy alcohol use was defined as a positive Rapid Alcohol Problems Screen.21

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of participants who did and did not trigger the intervention were described and compared using Fisher's exact test (categorical covariates), or Wilcoxon rank sum test (continuous covariates). To compare adherence before versus after the intervention, time intervals were defined as follows: (a) the 28 days immediately preceding the unannounced pill count <80%, (b) the time immediately preceding the first intervention session, defined as up to the last 28 days of the time between the unannounced pill count <80% and the first intervention session (often at the next clinic visit), and, (c) the 28 days immediately following the first intervention session. The interval between triggering and receiving the first intervention session could be several months due to the need to process data and participant related factors (e.g., travel and scheduling challenges). Medication adherence was calculated by dividing the number of doses taken by the number of prescribed doses. Adherence before versus after the first intervention session was compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Sensitivity analyses were conducted limiting data to the blinded study period (i.e., prior to release of efficacy findings on July 10, 2011).

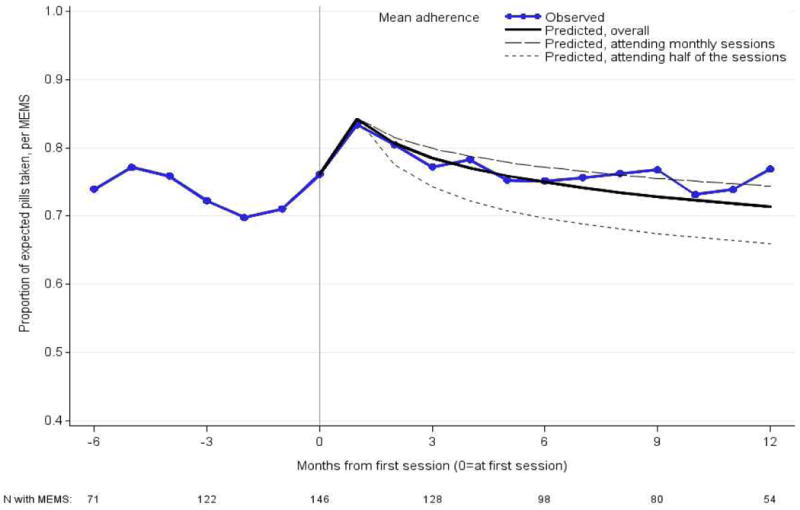

Adherence after the intervention was calculated by study month for each participant. The relationship between adherence and the intervention was estimated using data from 0-12 months post-intervention in a linear mixed model with a random intercept and slope for each participant. Predictors of interest were chosen based on the work of Haberer and colleagues9 and included time since the first intervention session (in months) and the number of adherence sessions completed; linear and non-linear relationships (e.g., log-linear, square root) between each of these factors and adherence were considered. Adjustment for confounding was considered for age, gender, sex with study partner in the prior month, polygamy, time on PrEP, and alcohol use at time of trigger9. Crude adherence before and up to 12 months post-intervention is presented in a plot. To illustrate model predictions for the 12 months following the intervention, predicted adherence overall by months since the first intervention session was also plotted along with two scenarios for number of sessions attended: (a) assuming a session was attended every month; (b) assuming that after the first session, additional sessions were only attended on average half the months. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3; p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical review

All study procedures were approved by institutional review boards and ethics committees from Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Healthcare, the University of Washington, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the Uganda Virus Research Institute.

Results

Supplemental content figure I depicts the flow of participants through the adherence intervention. 1,147 participants were eligible for the current analysis based on an enrollment date prior to July 10, 2011 (when the preliminary results from the Partners PrEP Study were released); participants were followed until the end of the parent study. A total of 168 (14.6%) of participants triggered the intervention due to <80% unannounced pill count adherence; of those, 9 were ineligible for follow-up analysis for the following reasons: taken off drug due to exit from study (N=1), seroconversion (N=1), or triggering immediately before unblinding of the placebo arm during the parent study (N=7). Of the remaining 159, 154 (91.7%) received at least one intervention session and 146 (94.8%) had adequate MEMS data based on time intervals described above to examine adherence following the intervention.

Participant characteristics are depicted in Table II and characteristics of the intervention are shown in Table III. The median number of sessions was 10 (IQR 5, 16). The length of the intervention sessions varied. The first session was the longest with a median of 40 minutes (IQR 30,50); session length decreased to a median of 20 minutes (IQR 15,30) by session four. Fourteen percent of participants participated in a couples session as part of their first intervention session. Per counselor report, the most frequently endorsed barriers to adherence at session one were travel (identified as a barrier for 50% of participants) and forgetting (identified as a barrier for 45% of participants). While the frequency of identified barriers to adherence decreased over time, travel and forgetting remained among the most commonly endorsed barriers across all sessions.

Table II.

Enrollment characteristics of intervention participants. N and % or median and IQR, unless otherwise specified.

| Enrollment characteristics | Participants who did not trigger N=979 |

Participants who triggered N=168 |

P-value | At the time of trigger N=168 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | ||||

| Female gender | 476 (49%) | 63 (38%) | 0.01 | |

| Age In years | 35 (31, 41) | 32.5 (28, 38) | <0.001 | |

| Time to clinic | 0.52 | |||

| < 30 minutes | 18 (2%) | 4 (2%) | ||

| 30-60 minutes | 102 (10%) | 23 (14%) | ||

| 1 – 2 hours | 317 (32%) | 54 (32%) | ||

| More than 2 hours | 542 (55%) | 87 (52%) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Monthly income (in US dollars) | $11.66 ($3.89, $31.09) | $15.54 ($3.89, $38.86) | 0.02 | |

| SES principle component 1 | -0.6 (-0.6, 0.4) | -0.3 (-0.6, 0.6) | <0.001 | |

| Positive alcohol screen per RASP | 82 (8%) | 11 (7%) | 0.54 | |

| Main source of income | 0.001 | |||

| Professional | 58 (6%) | 10 (6%) | ||

| Laborer | 187 (19%) | 44 (26%) | ||

| Trade/sales | 116 (12%) | 35 (21%) | ||

| Farming | 600 (61%) | 76 (45%) | ||

| Other | 18 (2%) | 3 (2%) | ||

| Partnership characteristics | ||||

| Married | 969 (99%) | 166 (99%) | 0.69 | |

| Living together | 963 (98%) | 166 (99%) | >0.99 | |

| Number of years living together | 9 (4, 16) | 7 (3.2, 12) | 0.001 | |

| Number of children in partnership | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 0.02 | |

| Number of years known discordant | 0.8 (0.1, 2.3) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.01 | |

| Polygamous relationship | 246 (25%) | 36 (22%) | 0.33 | |

| Outside partner in prior month | 96 (10%) | 19 (11%) | 0.59 | 35 (21%) |

| Sexually active together | 878 (90%) | 157 (94%) | 0.12 | 118 (71%) |

| Months on PrEP at time of trigger | 15.1 (7.0,20.7) |

Notes: Enrollment characteristics are at enrollment into the ancillary adherence study except income, main source of income, marital status, cohabitating status, years cohabitating, years known discordant, polygamous relationship, and HIV-infected partner HIV-1 viral load, which were collected at PrEP enrollment. Ancillary adherence study enrollment means when MEMS cap was issued. Outside partner in prior month and sexually active together were the only time varying variables, hence these data are provided at the time of trigger also, among those who triggered. P-values for continuous variables are computed using Wilcoxon rank sum test, and for categorical variables, including those with more than two categories, using Fisher's exact test.

Table III. Intervention Characteristics.

| Session Characteristics | Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | Session 4 | Sessions 5-9 | Sessions 10+ (10-28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 153 | 149 | 137 | 130 | 505 (mean per session = 101) | 457 (mean per session=23) |

| Length of session | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 40 (30-50) | 30 (20-30) | 25 (15-35) | 20(15-30) | 20(15-30) | 20(10-30) |

| Mean | 43.5 | 29.9 | 27.0 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 21.7 |

| Most frequently endorsed barriers to adherence | ||||||

| Side Effects | 14 (9%) | 5 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 2 (0%) |

| Forgot | 69 (45%) | 32 (21%) | 16 (12%) | 23 (18%) | 75 (15%) | 58 (13%) |

| Travel | 77 (50%) | 33 (22%) | 23 (17%) | 23 (18%) | 74 (15%) | 55 (12%) |

| Partner discord | 19 (12%) | 6 (4%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (1%) | 2 (0%) |

| Stigma/privacy | 15 (10%) | 6 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Missing transport | 16 (10%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Participants completing a couples session | 22 (14%) | 9 (6%) | 6 (4%) | 12 (9%) | 32 (6%) | 14 (3%) |

| Counselor estimate of adherence plan(% of participants)* | ||||||

| None or minimal | 18 (12%) | 12 (9%) | 11 (8%) | 39 (8%) | 36 (8%) | |

| Some | 35 (23%) | 24 (18%) | 28 (22%) | 68 (13%) | 35 (8%) | |

| Most/all/more than discussed | 96 (64%) | 101 (74%) | 91 (70%) | 398 (79%) | 386 (84%) |

This rating reflects the counselors' perception of how well a participant implemented the adherence plan set at the prior session. Data are not available for session one as session one represents the first time an adherence plan could be generated.

The mean adherence in the 28 days prior to the intervention trigger unannounced pill count was 64.6% and increased significantly to 75.7% (p<0.001) in the time interval immediately before the intervention (Table IV). Adherence after the intervention increased by an additional 8.4% compared to adherence immediately before the intervention (75.7% versus 84.1%, p <0.001). Seventy-five percent (N=110) of participants achieved adherence ≥ 80% at the study visit immediately after the first intervention session. Per sensitivity analyses, results after the intervention were very similar when limited to the blinded period of the study (data not shown). Results of the regression analysis of adherence over time following the first intervention session indicate that mean adherence increased by 8.1% in the first month after the intervention, followed by a log linear decline corresponding to a decline of 3.6% in the second month post-intervention, 0.9% by 6 months post-intervention, and 0.5% by 12 months post-intervention. The overall decline was 0.05 log per month (95% CI, 0.03-0.07, p<0.001), which was composed of a decrease of 0.18 log per month associated over time (95%CI, 0.10-0.25, p<0.001) and an increase of 0.14 log (95% CI, 0.06-0.22, p<0.01) for every session attended. These associations correspond to a steeper predicted decline for those attending only some sessions versus attending a session each month (figure I). Crude mean adherence at 12 months post-intervention remained higher than at the time of trigger, but not compared to the time immediately before the intervention. Crude mean adherence reached the level seen immediately before the intervention at 5 months post-intervention.

Table IV. Mean adherence before and after the first intervention session.

| Trigger | Immediately before intervention* | p-value** | Post intervention | Difference from time immediately before intervention to post intervention | p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS (N=146) | 64.6% | 75.7% | <0.001 | 84.1% | 8.4% | <0.001 |

Adherence is by MEMS caps. Trigger interval is the 28 day period prior to the home visit at which the participant triggered (adherence by unannounced pill count <80%). Immediately before intervention includes the last 28 days of the time after the trigger but before the first intervention, i.e., the time from the home visit to the subsequent clinic visit at which the first intervention session occurred. Post intervention is the 28 day period immediately following the intervention.

p-value obtained using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Figure I.

Mean crude and predicted adherence by months since the first intervention session, among those with adherence measured both before and after the first intervention. Predicted adherence overall by months since the first intervention session is given, along with two scenarios for number of sessions attended: (a) assuming a session was attended every month (b) assuming that after the first session, additional sessions were only attended on average half the months. Negative numbers refer to the months immediately before the first intervention session. Note that the trigger interval could be several months before the first intervention session (e.g., due to participant travel, scheduling challenges, etc.), and therefore no single month on this graph captures the mean of the trigger intervals across all participants.

Discussion

This adherence substudy within the context of a PrEP efficacy trial among HIV serodiscordant couples in Uganda found that a PrEP adherence intervention delivered was associated with a temporal improvement in electronically-monitored adherence to daily PrEP pill-taking. Adapting an evidence-based, behavioral ART treatment intervention to support PrEP adherence in a trial of HIV serodiscordant couples was also feasible. Most participants who triggered the intervention completed at least one intervention session, and nearly all participants completed additional sessions. Travel and forgetting were the most frequently addressed barriers. Men, younger persons, those with higher income, and those who identified themselves as laborers or employed in trade / sales reached the <80% adherence trigger more frequently than women, older persons, those with lower income, or those employed in other occupations, such as farming. This is consistent with findings from Haberer et al.9 and may indicate work or travel associated adherence barriers such as forgetting pills during travel or seasonal planting or that individuals perceive themselves at less risk while traveling for occupational reasons.

Some improvement in adherence was noted in between the time the intervention was triggered and the first intervention session was delivered. This improvement may be due to the resolution of time-limited barriers such as unanticipated travel for work or burials that resolved independently of the intervention. However, a problem-solving based adherence intervention may help individuals anticipate these events and minimize their impact on adherence. This approach is especially beneficial if periods of travel represent times of sexual risk, such as acquiring new partners while away from home. Such strategies are particularly important in sub-Saharan Africa, where travel to secure employment is common.22 In this study population, 26% of participants who triggered the intervention were classified as “laborers” and 21% identified their source of income as trade or sales.

Adherence increased from a mean of 75.8% to a mean of 84.1% in the period of time after the first intervention session. The level of PrEP adherence necessary to confer maximum benefit is currently unknown; current guidelines indicate that PrEP should be taken daily. Recent modeling data from a sample of men who have sex with men suggests that four doses of PrEP per week confers greater than 97% protection from HIV. 23 Thus, adherence interventions may be best targeted to those who are unable to meet this threshold of approximately 57% adherence, or four doses per week. However, these findings may not apply to heterosexual serodiscordant couples as concentrations of tenofovir diphosphate are higher in rectal tissue than vaginal tissue, 24 and more frequent dosing may be required to reach protective drug levels. Prior studies have shown a strong association between adherence and efficacy, thus supporting the use of adherence interventions. 8,9 Alternatively, the increase in adherence observed directly after the trigger could be explained by natural regression back to the mean after observing low adherence or that the pill count may have raised participants' awareness of recent adherence lapses and had an effect on increasing adherence.

Counseling sessions subsequent to the initial session were conducted at the discretion of the counselor and many individuals received multiple sessions. However, the data suggest that the majority of the benefit was seen after the first session. While the data imply that those who continued to attend monthly sessions had higher adherence than those who attended sessions less frequently, participants who attended a greater number sessions may also inherently be more adherent. In the absence of a control group, the effect of subsequent sessions remains uncertain. In either scenario, these sessions appeared to serve as relatively brief check-ins for many participants, and may have reflected the value of time with counselors. In implementation settings, it may be possible to deliver one-on-one counseling to PrEP users as presented in this intervention with fewer sessions, especially if adherence monitoring can identify those with particular need for support. Additionally, participants receiving the intervention can transition to other types of adherence support, such as groups or peer-based interventions, which are less resource intensive once barriers to adherence have resolved.

Sub-Saharan Africa bears a substantial amount of the global HIV burden. PrEP has the potential to fill an important gap in HIV prevention. While treating HIV positive persons with ART is also an important HIV prevention strategy16, not all HIV positive persons are able to access treatment, not all HIV positive persons want to initiate early treatment25 and not all HIV positive persons are able to adhere at the level that confers the maximum benefit needed for HIV prevention.26 PrEP use offers direct control of HIV prevention to uninfected individuals. In addition, individuals may have multiple partners and could benefit from PrEP even if their main partner is on effective HIV treatment. In this sample, 17% of participants reported an outside partner.9 In support of the need for HIV prevention, in recent studies of HIV serodiscordant couples, 25-30% of HIV transmissions were determined to be from an outside partner, based on genetic linkage of transmitted viruses. 16,27

The current study had several strengths, including an iterative process of intervention development based on an evidence-based antiretroviral therapy adherence intervention and rigorous adherence measurement. Because of the absence of a control group, inferences about the effect of the intervention on adherence are limited, though important information can still be generated when randomized designs are not possible.28 An additional limitation to the interpretation of the data results from the fact that the intervention was delivered in the context of a clinical trial conducted among individuals in heterosexual serodiscordant couples. Thus, results may not be fully generalizable to populations of other PrEP users. Lastly, interim trial results were announced in July 2011, after which time participants knew they were taking active drug. Knowledge that participants were taking an active compound may have also impacted adherence after unblinding, although we found the change in adherence at the time of the first intervention session was similar when limited to the period prior to unblinding.

In summary, PrEP, given sufficient adherence, is a promising biomedical intervention strategy for HIV-negative people to prevent infection. Nonadherence is one of the biggest threats to successful PrEP implementation. Based on findings from PrEP trials, it is likely that at least some subset of PrEP users will require adherence support. The World Health Organization stresses the importance of providing PrEP in contexts that support high adherence.29 Thus, future research must elucidate how to best identify PrEP users with low adherence for timely intervention and determine optimal duration of interventions to maximize PrEP effectiveness. Methods to identify PrEP users with low-adherence need to be cost-effective and accurate, as it is unlikely that electronic monitoring30 will be available outside of the clinical trial setting in the near future. Randomized controlled trials of PrEP interventions are also needed, and need to be conducted among various populations of PrEP users. Effective interventions may be feasible, even in busy clinical practices, if targeted to those in need. In some cases, those who stand to benefit the most from PrEP may also experience circumstances that negatively impact adherence, such as poverty, stigma, and psychiatric comorbidities. Such barriers to PrEP adherence require further study. Moving forward, biomedical agents for prevention of HIV should be used in conjunction with behavioral interventions to maximize their biologic effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This study and the Partners PrEP Study were both supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grants OOP47674 and OOP52516). Additional author time was supported by K23MH096651 (Psaros) and K24MH87227 (Bangsberg).

The authors would like to thank the study participants, DF/Net for data coordination, Dr. Stephen Becker from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the study sites: Tororo (Dr. Aloysious Kakia, and other team members), Kampala (Dr. Edith Nakku-Joloba, and other team members), and Kabwohe (Dr. Stephen Asiimwe, Deo Agaba, Dr. Rogers Twesigye, and other team members).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Psaros has served as a consultant to Bracket Global in the past; this work is unrelated to the submitted manuscript. For the remaining authors none were declared.

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 6th and 7th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, Miami, FL, in May 2011 and June 2012.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update. 2011 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_FactSheet_Global_en.pdf.

- 2.Van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS Lond Engl. 2012;26(7):F13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Microbicide Trials Network. MTN-003-VOICE. 2013 Available at: http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn003.

- 4.Marazzo J, Birbeck G, Nair G, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in women: Daily oral tenofovir, oral tenofovir/emtricitabine or vaginal tenofovir gel in the VOICE study. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329(5996):1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: A substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What's love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2012;59(5):463–468. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Lerma JG, Otten RA, Qari SH, et al. Prevention of rectal SHIV transmission in macaques by daily or intermittent prophylaxis with emtricitabine and tenofovir. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cogn Behav Pract. 1999;6(4):332–341. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(99)80052-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Tan JY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Social Competence Approach to Clinical Intervention. Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nezu A, D'Zurilla T. Social problem solving and negative affective conditions. In: Kendall P, Watson D, editors. Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features. New York: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell MS, Mullins JI, Hughes JP, et al. Viral linkage in HIV-1 seroconverters and their partners in an HIV-1 prevention clinical trial. PloS One. 2011;6(3):e16986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS Lond Engl. 2000;14(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Charlebois ED, et al. Multiple validated measures of adherence indicate high levels of adherence to generic HIV antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2004;36(5):1100–1102. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115. doi: 10.2307/3088292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, et al. Cross-national performance of the RAPS4/RAPS4-QF for tolerance and heavy drinking: data from 13 countries. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(3):428–432. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: a study of migrant and nonmigrant men and their partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(2):149–156. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151–ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louissaint NA, Cao YJ, Skipper PL, et al. Single dose pharmacokinetics of oral tenofovir in plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, colonic tissue, and vaginal tissue. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(11):1443–1450. doi: 10.1089/AID.2013.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heffron R, Ngure K, Mugo N, et al. Willingness of Kenyan HIV-1 serodiscordant couples to use antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2012;61(1):116–119. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825da73f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adakun SA, Siedner MJ, Muzoora C, et al. Higher baseline CD4 cell count predicts treatment interruptions and persistent viremia in patients initiating ARVs in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;62(3):317–321. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182800daf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Celum C, Wald A, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir and transmission of HIV-1 from persons infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):427–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West SG, Duan N, Pequegnat W, et al. Alternatives to the randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1359–1366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidance on pre-exposure oral prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV: Recommendations for use in the context of demonstration projects. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Accessed November 7, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK132003/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, et al. Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1340–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.