Abstract

In a previous issue of Psychological Science, we (Gernsbacher, 1993) reported that less skilled readers are less able than more skilled readers to quickly suppress irrelevant information (e.g., the contextually inappropriate meaning of a homonym, such as the playing-card meaning of spade, in the sentence He dug with the spade, or the inappropriate form of a homophone, such as patience, in the sentence He had lots of patients). In the current research, we investigated a ramification of that finding: If less skilled readers are less able to suppress a contextually inappropriate meaning of a homonym, perhaps less skilled readers might be better than more skilled readers at comprehending puns. However, intuition and previous research suggest the contrary, as do the results of the research presented here. On a task that required accepting, rather than rejecting, a meaning of a homonym that was not implied by the sentence context, more skilled readers responded more rapidly than less skilled readers. In contrast, on a task that required accepting a meaning of a homonym that was implied by the sentence context, more and less skilled readers performed equally well. We conclude that more skilled readers are more able to rapidly accept inappropriate meanings of homonyms because they are more skilled at suppression (which in this case involves suppressing the appropriate meanings).

Irrelevant or inappropriate information is often activated, unconsciously retrieved, or naturally perceived during comprehension. However, for successful comprehension, this inappropriate or irrelevant information must not be allowed to affect ongoing processes. Several experiments (reviewed in Gernsbacher, 1993) have demonstrated that less skilled readers are less able than more skilled readers to quickly suppress inappropriate, irrelevant, or should-be-ignored information. The results of these experiments provide an informative link toward understanding the complex nature of comprehension skill. If less skilled readers are less able to suppress inappropriate information, that would surely impede their comprehension processes.

In the experiments that demonstrate this phenomenon (Gernsbacher & Faust, 1991; Gernsbacher, Varner, & Faust, 1990), more and less skilled university-age readers were selected after their comprehension skill was measured on a multimedia comprehension battery (Gernsbacher & Varner, 1988). This battery measures subjects’ ability to comprehend written stories, spoken stories, and picture stories, although comprehension of the three media is very highly correlated. For each experiment, a sample of subjects was tested on the comprehension battery, and the more and less skilled readers were selected from the top and bottom thirds of the distribution, respectively.

One of the experiments (Gernsbacher et al., 1990, Experiment 4) indicated that less skilled readers are less able to quickly suppress the inappropriate meanings of homonyms. In this experiment, the subjects read a series of sentences, for example, He dug with the spade; following each sentence, the subjects were shown a test word, for example, ACE. The subjects’ task was to decide whether the test word fit the meaning of the sentence they had just read. Subjects’ latencies to decide that a test word like ACE did not fit the meaning of a sentence like He dug with the spade were compared with their latencies to decide the same test word did not fit the meaning of a comparison sentence, such as He dug with the shovel.

When the test words were presented immediately after subjects read the sentences, both the more and the less skilled readers took longer to reject test words (e.g., ACE) that were related to the inappropriate meanings of sentence-final homonyms (e.g., spade in He dug with the spade) than they took to reject the same test words when they were unrelated to the sentence and the sentence-final word (e.g., shovel in He dug with the shovel). This result suggests that activation from the inappropriate meanings caused interference for both the more and the less skilled readers, at the immediate test interval.

However, when the test words were presented 850 ms after subjects read the sentences, the more skilled readers no longer showed any interference, suggesting that they had successfully suppressed the inappropriate meanings of the homonyms. But even after the 850-ms delay, the less skilled readers still experienced interference. The results seem to indicate that less skilled readers are less able than more skilled readers to quickly suppress the inappropriate meanings of homonyms.

An experiment with homophones (Gernsbacher & Faust, 1991, Experiment 1) had similar results. In this experiment, a homophone was the final word of each critical sentence (e.g., He had lots of patients), and the test word was related to the other form of the homophone (e.g., CALM). When test words were presented immediately after subjects read the sentences, both the more and the less skilled readers took longer to reject a test word after reading a sentence with a related homophone than they did to reject the same test word after reading a sentence that did not contain a homophone (e.g., He had lots of students). Thus, both more and less skilled readers immediately experienced interference caused by the activation of the inappropriate form of the homophone. After a delay, which in this experiment was 1,000 ms, the more skilled readers no longer showed interference, whereas the less skilled readers did. Apparently less skilled readers are also less able than more skilled readers to quickly suppress the inappropriate forms of homophones.

These experiments and others suggest that less skilled readers are less able than more skilled readers to suppress inappropriate information quickly. However, these experiments appear to suggest a rather unintuitive prediction: If less skilled readers are less able to quickly suppress the inappropriate meanings of homonyms and homophones, then—ironically—less skilled readers might be better than more skilled readers at understanding puns. To understand a pun promptly, one has to quickly access the unexpected meaning of a homonym or homophone. For example, to understand the joke “Two men walk into a bar, and a third man ducks,” one has to access the meaning of bar not typically associated with jokes or things that men typically walk into.

However, intuition suggests that it is the more skilled readers who should be more skilled at comprehending puns. After all, more skilled readers are, by definition, more skilled. Research seems to agree, although none has been conducted specifically to test this hypothesis. Comparison of more and less skilled university-aged readers has shown the more skilled are more facile at drawing inferences (Long & Golding, 1993) and at revising erroneously drawn inferences (Whitney, Ritchie, & Clark, 1991). A striking marker of the development of language comprehension skill is the ability to comprehend riddles and other plays on words. Longitudinal (Hirsh-Pasek, Gleitman, & Gleitman, 1978) and cross-sectional (Fowles & Glanz, 1977; Yuill & Oakhill, 1991) research both demonstrate that as children become more skilled in language comprehension, they become more proficient at understanding riddles. Riddles, like puns, often play off of the unexpected meanings of homonyms and homophones.

The research presented here specifically investigated whether less or more skilled university-aged readers were more facile at selecting a meaning of a homonym that was not implied by the sentence context in which the homonym occurred. Subjects read a series of sentences and, following each sentence, responded to a test word. In one block of trials, we measured how rapidly the subjects could select the inappropriate meanings of homonyms, that is, the meanings not implied by the sentence contexts. The subjects were told to respond “yes” to a test word if that word was related to one meaning of the final word of the sentence, but not the meaning implied by the sentence. For example, if subjects read the sentence He dug with the spade and were tested with the word ACE, they were to respond “yes” because ACE is related to one meaning of the word spade, but not to the meaning of the word spade implied in the sentence. This procedure enabled us to examine whether more and less skilled readers differed in how rapidly they accepted the inappropriate meanings of homonyms.

We compared how rapidly the two groups of readers accepted inappropriate meanings of homonyms with how rapidly they accepted the appropriate meanings. In a different block of trials, the subjects’ task was to judge whether each test word was related to both the sentence-final word and the meaning of the sentence. When performing this task, for example, if subjects read the sentence He dealt the spade and were tested with the word ACE, they were to respond “yes” because ACE is related to a meaning of the word spade, and also to the meaning of the word spade implied in the sentence. This task is similar in spirit to a task used in previous studies (Gernsbacher et al., 1990; Gernsbacher & Faust, 1991). In those studies, subjects were told to judge whether the test word “fit the meaning of the sentence.” Based on the earlier results (Gernsbacher & Faust, 1991, Experiment 4), we predicted that more and less skilled readers would not differ in their speed at correctly accepting the appropriate meanings of homonyms.

To summarize, we compared more and less skilled readers’ latencies to accept the inappropriate meanings of homonyms with their latencies to accept the appropriate meanings. Subjects read sentences and made two types of judgments to test words: In one block of trials, they judged whether each test word was related to the sentence-final word but not to the sentence; in another block of trials, they judged whether each test word was related to both the sentence-final word and the sentence. We presented each test word 1,000 ms after subjects read each sentence, so that we could measure subjects’ responses after a period of time that in our previous work allowed at least the more skilled readers to employ suppression successfully.

METHOD

Subjects

The subjects were 80 undergraduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Half (40) were classified as more skilled readers, and half (40) were classified as less skilled readers, on the basis of their performance on the reading component of the multimedia comprehension battery. The more and less skilled readers were selected from the top and bottom thirds of a sample of 127 subjects. On the comprehension battery, the mean performance of all 127 subjects was 70.5% correct (SD = 10%). The mean performance of the 40 more skilled readers was 81% correct (SD = 5%), and the mean performance of the 40 less skilled readers was 59% correct (SD = 7%).

Procedure

Subjects were told that they would read a series of sentences, and following each sentence, they would see a test word. During one block, the subjects’ task was to judge whether the test word was related to a meaning of the final word of the sentence, but not the meaning implied by the sentence. Subjects were told that after reading a sentence such as He dug with the spade, if they were tested with the word ACE, they should respond “yes” because ACE is related to one meaning of the word spade, but not to the meaning of the word spade implied in the sentence. In the block of trials for which subjects performed this task, there were 20 trials for which the correct response was “yes” and 20 trials for which the correct response was “no.” On half of the latter trials, the test word was unrelated to both the sentence-final word and the sentence (e.g., ACE and He dug with the shovel). For the remaining half of the trials for which the correct answer was “no,” the test word was related to one meaning of the sentence-final word, and that was the meaning implied by the sentence (e.g., ACE and He dealt the spade). These three types of trials are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example stimuli for the two tasks

| Sentence | Test word |

Correct response |

Number of trials |

Trial type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task: Related to sentence-final word but not sentence | ||||

| He dug with the spade. | ACE | Yes | 20 | Accept inappropriate meanings |

| He dealt the spade. | ACE | No | 10 | Reject appropriate meanings |

| He dug with the shovel. | ACE | No | 10 | Reject unrelated test words |

| Task: Related to both sentence-final word and sentence | ||||

| He dealt the spade. | ACE | Yes | 20 | Accept appropriate meanings |

| He dug with the spade. | ACE | No | 10 | Reject inappropriate meanings |

| He dug with the shovel. | ACE | No | 10 | Reject unrelated test words |

During another block of trials, the subjects’ task was to judge whether the test word was related to both the sentence-final word and the meaning of the sentence. Subjects were told that after reading a sentence such as He dealt the spade, if they were tested with the word ACE, they should respond “yes” because ACE is related to a meaning of the word spade and also to the meaning of the word spade implied in the sentence. In the block of trials for which subjects performed this task, there were 20 trials for which the correct response was “yes” and 20 trials for which the correct answer was “no.” On half of the latter trials, the test word was unrelated to either the sentence-final word or the sentence itself (e.g., ACE and He dug with the shovel). For the remaining half of the trials for which the correct answer was “no,” the test word was related to a meaning of the sentence-final word, but that was not the meaning implied by the sentence (e.g., ACE and He dug with the spade). These three types of trials are also illustrated in Table 1.

Half the subjects of each skill level completed a block of 40 trials performing one task first, and then a block of 40 trials performing the other task. The other half of the subjects of each skill level completed the two blocks in the opposite order. Subjects were not given instructions for a second task until they had completed all the trials performing the first task.

The length of time each sentence was presented depended on the number of words in the sentence: Duration equaled a constant of 2,000 ms plus 33 ms per word. Each test word was presented 1,000 ms after its sentence disappeared and remained on the screen until the subject responded or 2,500 ms elapsed. Subjects practiced on 20 sentences before each of the two blocks, using the task they would be performing for that block. During the experiment, they were given feedback after each trial as to whether their response was correct. Data from subjects who performed with less than 70% accuracy were discarded.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

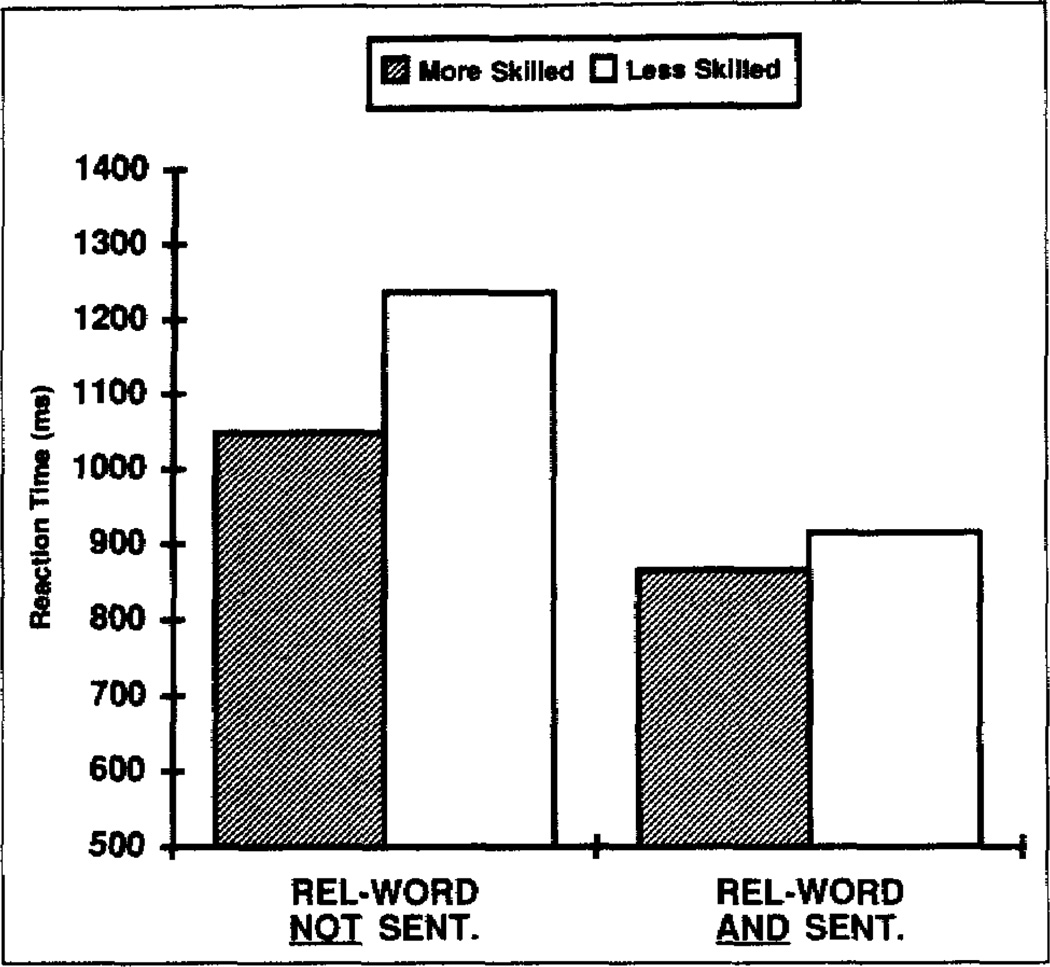

Table 2 presents the subjects’ average reaction time (in milliseconds) and percentage of correct responses for the three types of trials within each of the two task blocks. Of primary interest is subjects’ performance on the trials for which they should have responded “yes”; these trials demonstrate ability to accept inappropriate meanings and ability to accept appropriate meanings. Figure 1 displays the subjects’ average reaction times on those trials. The two leftmost bars illustrate more versus less skilled readers’ latencies to accept the inappropriate meanings of homonyms, and the two rightmost bars illustrate more versus less skilled readers’ latencies to accept the appropriate meanings of the homonyms.

Table 2.

Subjects’ average reaction time (in milliseconds) and percentage correct

| More skilled readers | Less skilled readers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial type | Reaction time | Percentage correct | Reaction time | Percentage correct |

| Task: Related to sentence-final word but not sentence | ||||

| Yes trials | ||||

| Accept inappropriate meanings | 1,047 | 85 | 1,235 | 84 |

| No trials | ||||

| Reject appropriate meanings | 1,096 | 80 | 1,298 | 75 |

| Reject unrelated test words | 1,251 | 82 | 1,308 | 80 |

| Task: Related to both sentence-final word and sentence | ||||

| Yes trials | ||||

| Accept appropriate meanings | 865 | 93 | 914 | 91 |

| No trials | ||||

| Reject inappropriate meanings | 932 | 91 | 1,074 | 87 |

| Reject unrelated test words | 974 | 93 | 1,011 | 93 |

Fig. 1.

Subjects’ mean reaction times on the trials for which the correct response was “yes.” The two leftmost bars illustrate subjects’ reaction times when they judged that a test word was related to a meaning of the sentence-final word but not to the sentence; the two rightmost bars illustrate subjects’ reaction times when they judged that the test word was related to both a meaning of the sentence-final word and the sentence.

As the two leftmost bars in Figure 1 illustrate, when the task required correctly accepting test words related to the inappropriate meanings, the more skilled readers responded more rapidly than did the less skilled readers, F(1, 76) = 9.49, p < .003. In contrast, as the two rightmost bars in Figure 1 illustrate, when the task required correctly accepting test words related to the appropriate meanings, the more and less skilled readers did not differ reliably in their speed, F ~ 1. This latter finding replicates our earlier observation (Gernsbacher & Faust, 1991, Experiment 4) that more and less skilled readers did not differ in their speed at correctly accepting test words related to the appropriate meanings of homonyms. The interaction between task (accepting inappropriate meanings vs. accepting appropriate meanings) and reading-skill group (more skilled vs. less skilled) was reliable, F(1, 77) = 10.68, p < .02.

Although the two reading-skill groups’ reaction times differed on one task (accepting inappropriate meanings), but not on the other task (accepting appropriate meanings), the two groups’ accuracy did not differ within the two tasks. As illustrated in Table 1, the more and less skilled readers performed with 85% and 84% accuracy, respectively, when accepting inappropriate meanings and with 93% and 91% accuracy, respectively, when accepting appropriate meanings. Neither of these differences was statistically reliable (both Fs < 1). Thus, the interaction found for reaction time did not result from a speed-accuracy trade-off.

We also suggest that the interaction displayed in Figure 1 is unlikely to be a scaling artifact. As shown in the bottom half of Table 2, when the task was to judge whether a test word was related to both the sentence-final word and the sentence, both groups’ latencies to reject unrelated test words were on average 100 ms slower than their latencies to accept test words related to the appropriate meanings (the latter being the data presented in the two rightmost bars of Fig. 1); yet on these trials with slower reaction times, the difference between the two groups’ latencies was even smaller and still unreliable (F < 1). Thus, slower reaction times did not lead to larger differences between the two skill groups.

We conclude that more skilled readers can more rapidly accept the inappropriate meanings of homonyms, suggesting that more skilled readers—rather than less skilled readers—should be more skilled at comprehending puns rapidly. But we are left with a puzzle: Why are less skilled readers slower than more skilled readers to accept inappropriate meanings but equal to more skilled readers in their speed of accepting appropriate meanings?

To solve this puzzle, consider the following. First, less skilled readers are not impaired in their ability to maintain the activation of the inappropriate meanings of homonyms. As we described in the beginning of this article, we have observed ample evidence to support this proposal in our previous work (Gernsbacher et al., 1990). Indeed, keeping inappropriate information activated is often less skilled readers’ embarrassment of riches. In our previous work, we observed that even 850 ms after less skilled readers read a sentence such as He dug with the spade, they continued to show interference from the inappropriate meaning of the homonym (the playing-card meaning of spade). In the present experiment, we observed the same phenomenon. As shown in Table 2, in the block of trials for which the subjects’ task was to judge whether a test word was related to both the sentence-final word and the sentence, the less skilled readers rejected test words related to the inappropriate meanings more slowly than test words that were completely unrelated, whereas the more skilled readers rejected words related to inappropriate meanings faster than unrelated words (F[1, 77] = 3.618, p < .06, for the interaction between task type [rejecting inappropriate meanings vs. rejecting unrelated test words] and reading skill [more vs. less skilled]). If less skilled readers were unable to maintain the activation of these inappropriate meanings, they should not have experienced this interference. Instead, these data demonstrate that less skilled readers are not impaired in their ability to maintain the activation of the inappropriate meanings of homonyms, if they have activated those meanings (Just & Carpenter, 1992).

Second, less skilled readers are not impaired in their ability to maintain the activation of the appropriate meanings of homonyms. We have reported evidence that supports this proposal in our previous work, and we observed replicating evidence in the current experiment. The less skilled readers responded as rapidly and as accurately as the more skilled readers when the task was to accept the appropriate meanings of the homonyms. This finding suggests that less skilled readers do not have difficulty keeping activated the appropriate meanings of homonyms, even for as long as 1,000 ms. Other experiments document that less skilled readers have no difficulty activating and maintaining the activation of contextually appropriate information (e.g., Perfetti & Roth, 1981).

Third, less skilled readers are impaired in employing suppression quickly. In our previous work, we observed that less skilled readers are less able to quickly suppress the inappropriate meaning of a homonym, the incorrect form of a homophone, a typical-but-absent object in a scenic array, and a printed word superimposed on a picture or a picture surrounding a printed word. Less skilled readers’ slower latencies to reject the inappropriate meanings in the current experiment (when their task was to accept the appropriate meanings) further demonstrates that less skilled readers are impaired in employing suppression quickly.

Next, we suggest that accepting an inappropriate meaning of a homonym might require suppressing the appropriate meaning. Consider again the pun “Two men walk into a bar, and a third man ducks.” Intuition suggests that to understand this play on words, one must move beyond the “appropriate” meaning of bar—the meaning typically brought to mind when one hears the word in a joke context. It is as though the ability to appreciate the contextually less predictable meaning of bar (as an obstruction that men might walk into) hinges on the ability to ignore the contextually more predictable meaning of bar (as a place men are considerably more likely to walk into).

Protocols collected from less skilled elementary school readers, who have difficulty understanding riddles, suggest a similar sequence of events. When less skilled elementary school readers who are unable to solve the spoken riddle “What’s black and white and /red/ all over?” are informed that the correct answer is “a newspaper,” they continue to perseverate on the color meaning of /red/. They say, “But newspapers don’t come in red, only black and white,” or “I don’t understand; a newspaper would look funny if it was red,” as though they are unable to move beyond (i.e., suppress) the contextually related meaning of /red/—the meaning associated with the terms black and white (Yuill & Oakhill, 1991).

Therefore, we propose that less skilled readers are slower to accept inappropriate meanings because they are less able than more skilled readers to suppress the appropriate meanings. Data from the current experiment support this proposal. In the block of trials for which the subjects’ task was to judge whether a test word was related to the sentence-final word but not to the sentence, there was a type of trial that measured how quickly subjects could reject the appropriate meanings. For example, subjects had to reject ACE after reading He dealt the spade. As illustrated in Table 2, the less skilled readers responded considerably more slowly than the more skilled readers on this type of trial, for which they had to reject the appropriate meanings. F(1, 76) = 11.46, p < .001. Thus, less skilled readers are not slower than more skilled readers to accept appropriate meanings (when their task is to accept appropriate meanings), but they are slower to reject appropriate meanings (when their task is to accept inappropriate meanings). This pattern suggests that less skilled readers’ greater latency in accepting inappropriate meanings could derive from their greater difficulty in suppressing appropriate meanings.

Solving this puzzle provides a more complete picture of the relation between reading skill and suppression. The present research augments our previous research by demonstrating that depending on the nature of the comprehension task, suppression is employed not only to reject inappropriate information but also to accept inappropriate information (by dampening the activation of appropriate information). In our laboratory, we created a task requiring accepting inappropriate information by asking subjects to judge whether test words were related to the inappropriate meanings of homonyms. Outside the laboratory, comprehending puns and other plays on words imposes a similar task. Our conclusion is that skilled reading depends on skilled suppression—even suppression of appropriate information.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS 29926 and K04 NS 01376), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR 89-0258), and the Army Research Institute (DASW0194-K-004). We are grateful to Caroline Bolliger, Jennifer Deaton, and Heather Rippl for their help in testing subjects, and to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Fowles B, Glanz ME. Competence and talent in verbal riddle comprehension. Journal of Child Language. 1977;4:433–452. [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA. Less skilled readers have less efficient suppression mechanisms. Psychological Science. 1993;4:294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA, Faust ME. The mechanism of suppression: A component of general comprehension skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1991;17:245–262. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.17.2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA, Varner KR. The Multi-Media Comprehension Battery. Eugene: University of Oregon, Institute of Cognitive and Decision Sciences; 1988. (Technical Report No. 88-03). [Google Scholar]

- Gernsbacher MA, Varner KR, Faust M. Investigating differences in general comprehension skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;I6:430–445. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.3.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, Gleitman LR, Gleitman H. What did the mind say to the brain? A study of the detection and report of ambiguity by young children. In: Sinclair A, Jarvella RJ, Levelt WJM, editors. The child’s conception of language. New York: Springer; 1978. pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review. 1992;99:122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DL, Golding JM. Superordinate goal inferences: Are they automatically encoded during comprehension? Discourse Processes. 1993;16:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Roth S. Some of the interactive processes in reading and their role in reading skill. In: Lesgold AM, Perfetti CA, editors. Interactive processes in reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 269–297. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P, Ritchie BG, Clark MB. Working-memory capacity and the use of elaborative inferences in text comprehension. Discourse Processes. 1991;14:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yuill N, Oakhill J. Children’s problems in text comprehension: An experimental investigation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]