Abstract

Preterm birth is associated with 5-18% of pregnancies and is a leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality. Spontaneous preterm labor, a syndrome caused by multiple pathologic processes, leads to 70% of preterm births. The prevention and treatment of preterm labor have been a long-standing challenge. We summarize the current understanding of the mechanisms of disease implicated in this condition, and review advances relevant to intra-amniotic infection, decidual senescence, and breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance. The success of progestogen treatment to prevent preterm birth in a subset of patients at risk is a cause for optimism. Solving the mystery of preterm labor, which compromises the health of future generations, is a formidable scientific challenge worthy of investment.

Preterm birth, defined as birth prior to 37 weeks of gestation, affects 5-18% of pregnancies. It is the leading cause of neonatal death and the second cause of childhood death below the age of 5 years (1). Approximately 15 million preterm neonates are born every year, and the highest rates occur in Africa and North America (2). Neonates born preterm are at an increased risk of short-term complications attributed to immaturity of multiple organ systems, as well as neurodevelopmental disorders, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and vision/hearing impairments (3). Preterm birth is a leading cause of disability-adjusted life years, the number of years lost due to ill health, disability or early death (4), and the annual cost in the United States is at least $26.2 billion per year and climbing (5).

Two-thirds of preterm births occur after the spontaneous onset of labor, whereas the remainder is medically indicated due to maternal or fetal complications, such as preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction (6). Herein we propose that preterm labor is a syndrome caused by multiple pathologic processes, summarize important gains in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth, and highlight promising areas for investigation.

Preterm Labor: Not Just Labor Before Term

A tacit assumption underlying the study of parturition is that preterm labor is merely labor that starts too soon. In other words, the main difference between preterm and term labor is when labor begins. This is perhaps understandable given that both involve similar clinical events: increased uterine contractility, cervical dilatation, and rupture of the chorioamniotic membranes (7). These events represent the “common pathway” of labor. The current understanding of this process is that the switch of the myometrium from a quiescent to a contractile state is accompanied by a shift in signaling between anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory pathways, including chemokines (interleukin-8), cytokines (interleukin-1 and -6), and contraction-associated proteins (oxytocin receptor, connexin 43, prostaglandin receptors). Progesterone maintains uterine quiescence by repressing the expression of these genes. Increased expression of the miR-200 family near term can derepress contractile genes and promote progesterone catabolism (8). Cervical ripening in preparation for dilatation is mediated by changes in extracellular matrix proteins, which include a loss in collagen cross-linking, and an increase in glycosaminoglycans, as well as changes in epithelial barrier and immune surveillance properties (9). This decreases the tensile strength of the cervix, key for cervical dilatation. Decidual/membrane activation refers to the anatomical and biochemical events involved in withdrawal of decidual support for pregnancy, separation of the chorioamniotic membranes from the decidua, and eventually, membrane rupture. Increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1) and chemokines, increased activity of proteases (MMP-8 and MMP-9), dissolution of cellular cements such as fibronectin, and apoptosis have been implicated in this process (10, 11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Labor (term and preterm) is characterized by increased myometrial contractility, cervical dilatation, and rupture of the chorioamniotic membranes. Collectively, these events have been referred to as the “common pathway of parturition.” The switch of the myometrium from a quiescent to a contractile state is associated with a change in nuclear progesterone receptor isoforms and an increase in the expression of the miR-200 family, as well as an increase in estrogen receptor α signaling. Cervical ripening is mediated by changes in extracellular matrix proteins, as well as changes in epithelial barrier and immune surveillance properties. Decidual/membrane activation, in close proximity to the cervix, occurs in preparation for membrane rupture, and to facilitate separation of the chorioamniotic membranes and placenta from the uterus. E: epithelium; M: mucus; Os: cervical os.

In our view, the common pathway is activated physiologically in the case of labor at term, whereas several disease processes activate one or more of the components of the common pathway in the case of preterm labor. This conceptual framework has implications for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of spontaneous preterm labor. For example, interest in myometrial contractility, the most recognizable sign/symptom of preterm labor, has led clinical and translational research to focus on the use of pharmacologic agents to arrest or decrease uterine contractility (i.e. tocolytics) with the goal of preventing preterm delivery. Yet, after decades of investigation, there is no persuasive evidence that inhibiting or arresting uterine contractility per se decreases the rate of preterm delivery or improves neonatal outcome, although these agents can achieve short-term prolongation of pregnancy for steroid administration and maternal transfer to tertiary care centers. We consider that, in most cases, tocolytic agents address a symptom, and not the underlying cause(s) that activate the parturitional process. The extent to which the physiologic signals that mediate labor at term can be co-opted in the context of pathologic processes in preterm labor remains to be elucidated.

Preterm Labor as a Syndrome Associated with Multiple Mechanisms of Disease

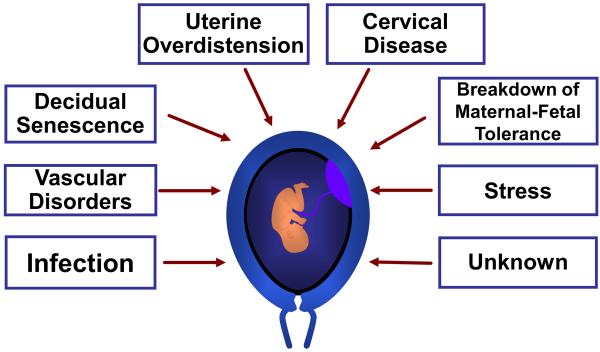

Spontaneous preterm labor is often treated implicitly or explicitly as if it were a single condition. Accumulating evidence suggests that it is a syndrome attributable to multiple pathologic processes (7). Figure 2 illustrates the mechanisms of disease implicated in spontaneous preterm labor. Of these, only intra-amniotic infection has been causally linked to spontaneous preterm delivery (12). The others are largely based on associations reported by clinical, epidemiologic, placental pathologic, or experimental studies.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanisms of disease implicated in spontaneous preterm labor. Genetic and environmental factors are likely contributors to each mechanism.

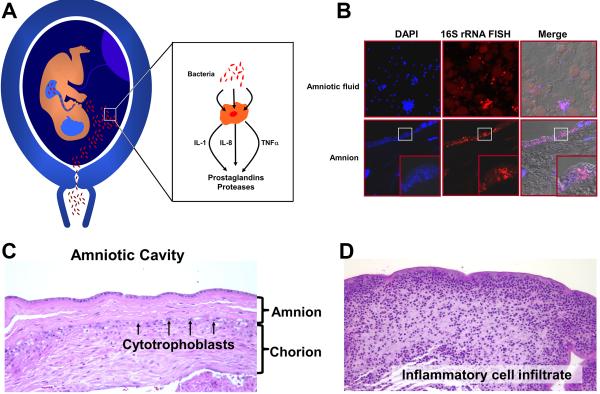

Microbial-Induced Inflammation

One of every three preterm infants is born to mothers with an intra-amniotic infection that is largely subclinical (12). Microorganisms isolated from the amniotic fluid are similar to those found in the lower genital tract, and therefore, an ascending pathway is considered the most frequent route of infection. Bacteria involved in periodontal disease have been found in the amniotic fluid, suggesting that hematogenous dissemination with transplacental passage can also occur (13). Microbial-induced preterm labor is mediated by an inflammatory process. Microorganisms and their products are sensed by pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) which induce the production of chemokines (e.g. IL-8, IL-1, CCL-2), cytokines (e.g. IL-β, TNF-α), prostaglandins, and proteases leading to activation of the common pathway of parturition (12, 14, 15) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of microbial-induced preterm labor. (A) Bacteria from the lower genital tract gain access to the amniotic cavity and stimulate the production of chemokines and cytokines (IL-1α, TNFα), as well as inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins and reactive oxygen radicals) and proteases. These products can initiate myometrial contractility and induce membrane rupture. (B, upper left) Amniotic fluid containing bacteria that was retrieved by amniocentesis from a patient with preterm labor. Bacteria and nuclei stain with DAPI (blue). (upper middle) Bacteria identified with a probe against 16S rRNA using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). (B, lower left and middle) Bacteria invading the amnion epithelium. Note the absence of bacteria in the subepithelial part of the amnion, suggesting that the pathway of microbial invasion is ascending into the amniotic cavity. (C) Chorioamniotic membranes without evidence of inflammation. Amnion and chorion are identified. (D) A similar membrane section as C from a patient with intramniotic infection. Inflammatory cells from the mother infiltrate the chorion and amnion.

In 30% of cases of intra-amniotic infection, bacteria are identified in the fetal circulation (16), resulting in a fetal systemic inflammatory response (17). Such fetuses have multi-organ involvement and are at risk for long-term complications, such as cerebral palsy and chronic lung disease, underscoring that complications of infants born preterm are not only due to immaturity, but also to the inflammatory process responsible for preterm labor. This has important implications since recent evidence suggests that downregulation of congenital systemic inflammation in the neonatal period using nanodevices coupled with anti-inflammatory agents can reverse a cerebral palsy-like phenotype in an animal model (18).

From an evolutionary perspective, the onset of preterm labor in the context of infection can be considered to have survival value, as it allows the mother to expel infected tissue and maintain reproductive fitness. In a remarkable example of evolutionary co-option, the molecular mechanisms developed for host defense against infection in primitive multicellular organisms (e.g. pattern recognition receptors in sponges) have been deployed in viviparous species to initiate parturition in the context of infection. This unique mechanism of maternal host defense comes at a price - prematurity. In terms of the fetus, inflammation may also have survival value near term, contributing to infant host defense against infection and accelerating lung maturation (19).

A central question is why some women develop an ascending intra-amniotic infection, whereas most do not. The relationship between the mucosa of the lower genital tract (vagina and cervix) and the microbial ecosystem appears key. Bacterial vaginosis – a change in the microbial ecosystem in which there is proliferation of anaerobic bacteria – confers risk for intra-amniotic infection and spontaneous preterm delivery. However, antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic women with bacterial vaginosis has not reduced the rate of preterm delivery. A comprehensive understanding of microbial ecology, genetic factors that control susceptibility to infection and the inflammatory response is required, particularly in light of evidence that gene-environment interactions may predispose to preterm labor (20). Viral infection has recently been shown to alter mucosal immunity in the lower genital tract, and to predispose to ascending bacterial infection (21).

Early studies of the vaginal microbiota in normal pregnancy using sequence-based techniques suggest that this ecosystem, which is different from that of the non-pregnant state, is more stable (22). Whether the vaginal microbiota and the local immune response of the vagina are different between women who subsequently deliver preterm and those who deliver at term are important unanswered questions (23, 24). The factors responsible for changes in the vaginal microbiota during pregnancy remain to be established. Sex steroid hormones are attractive candidates, given that estrogens can induce the accumulation of glycogen in the vaginal epithelium and also modify glycosylation (25). Carbohydrate structures are key for bacterial adherence to mammalian cells, and therefore, sex steroid hormones could alter the microbiota of the lower genital tract.

At a mechanistic level, little is known about how preterm labor-related infections occur. On the pathogen side, the Group B Streptococcus pigment plays a role in the hemolytic and cytolytic activity required for ascending infection related to preterm birth (26). Further work is required to elucidate the role of the host. One intriguing possibility involves the “glyco-code,” specific aspects of human carbohydrate structures that mediate the binding of bacteria via lectins and, subsequently, adherence. For example, Helicobacter pylori adhere via the Lewis b blood group glycan, making populations that express this antigen more susceptible to infection. Conversely, blood group O provides a selective advantage for surviving malaria (27). Whether similar mechanisms may help explain the increased frequency of spontaneous preterm birth in some ethnic groups is a question for in-depth exploration.

Although the maternal-fetal interface has traditionally been considered sterile, bacteria and viruses have been identified in decidua of the first and second trimesters (28). Moreover, a placental microbiota has been described using sequence-based techniques (29), along with differences reported between patients who delivered preterm and term (29). Large studies, such as those under consideration by the Human Placenta Project (30), are required to clarify the role of a putative placental microbiota and the maternal and fetal immune response in normal pregnancy and spontaneous preterm labor. However, recent studies using a combination of cultivation and molecular techniques suggest that intra-amniotic inflammation associated with spontaneous preterm labor occurs in the absence of demonstrable microorganisms, suggesting a role for sterile intra-amniotic inflammation (31).

Extra-uterine infections are also associated with spontaneous preterm delivery (e.g., malaria, pyelonephritis, pneumonia). Indeed, from a global health perspective, malaria may be a major contributor to preterm birth in endemic areas. The mechanisms whereby malaria leads to preterm labor remain to be determined.

Decidual Hemorrhage and Vascular Disease

A subset of patients with preterm labor with intact membranes and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM) have vaginal bleeding, attributed to defective decidual hemostasis. Thrombin generated during the course of decidual hemorrhage can stimulate myometrial contractility and degrade extracellular matrix in the chorioamniotic membranes, predisposing to rupture (32, 33). Mothers with evidence of increased thrombin generation are at greater risk for spontaneous preterm labor. Uterine bleeding has also been observed with vascular lesions of the placenta. During normal pregnancy, cytotrophoblast invasion physiologically transforms uterine spiral arteries—small diameter, high resistance vessels—into large diameter, low resistance conduits that perfuse the chorionic villi of the placenta (Figure 4A, B and D). Approximately 30% of patients with preterm labor have placental lesions consistent with maternal vascular underperfusion, and a similar number have failure of physiologic transformation of the myometrial segment of the spiral arteries (34). In these cases, the vessel lumen fails to expand (Figure 4C and E), a pathological feature that is commonly associated with preeclampsia (maternal high blood pressure, protein in the urine) (35). An abnormal maternal plasma anti-angiogenic profile in the midtrimester, which predates the symptoms of preeclampsia (36), has also been reported in a subset of patients who deliver preterm and have placental vascular lesions of underperfusion (37). Understanding why some women with these vascular lesions and an abnormal angiogenic profile develop preeclampsia and others preterm labor, can provide insights into the pathophysiology of both conditions.

Figure 4.

A subset of patients with preterm labor has placental vascular lesions, including failure of physiologic transformation of the uterine spiral arteries. (A) Schematic drawing of the maternal-fetal interface in normal pregnancy. A physiologically transformed uterine spiral artery with a wide lumen delivers blood to the intervillous space of the placenta to supply blood to villi. (B) A spiral artery with an expanded ostium that normally enables adequate perfusion of the intervillous space. (C) Ostium of a narrow spiral artery with failure of physiologic transformation in a patient with spontaneous preterm labor. (D) PAS staining of a histological section of the maternal-fetal interface in normal pregnancy shows a spiral artery transformed by cytokeratin 7-positive cytotrophoblasts (brown) that line the lumen (200x). (E) Failure of physiologic transformation of a spiral artery in a patient with preterm labor. The lumen is narrow and cytotrophoblasts have not invaded the muscular wall (200×).

Decidual Senescence

Around the time of implantation, the endometrium undergoes anatomical and functional changes to become the decidua, which is crucial for successful implantation, maintenance of pregnancy, and parturition. Decidualization is characterized by extensive proliferation and differentiation of uterine stromal cells into specialized cell types called decidual cells. The tumor suppressor protein p53 plays an important role in decidual growth, and its deletion causes implantation failure or, if pregnancy is established, inadequate decidualization. Premature decidual senescence has been implicated in implantation failure, fetal death, and preterm birth. In mice, conditional deletion of uterine Trp53 leads to spontaneous preterm birth in 50% of cases (38), which is associated with decidual senescence demonstrated by increased mTORC1 signaling, p21 levels, and β-galactosidase staining but without progesterone withdrawal (38, 39). The administration of rapamycin (an mTOR inhibitor) and/or progesterone attenuates premature decidual senescence and preterm birth. Evidence of decidual senescence has been demonstrated in the basal plate of the placenta (placental surface in direct contact with the uterine wall) in cases with preterm labor, but not in women who delivered at term (39). Whether other mechanisms of preterm labor (e.g., infection, uterine bleeding) converge on decidual senescence is an open question. Additionally, it would be interesting to determine whether tissue stiffness, measured by atomic force microscopy, is a proxy for decidual senescence and therefore, a biomarker (40).

Disruption of Maternal-fetal Tolerance

The fetus and placenta express both maternal and paternal antigens and are therefore, semi-allografts (41). Immune tolerance is required for successful pregnancy (42, 43), and a breakdown in tolerance can lead to a pathologic state (Figure 2) with features of allograft rejection. Chronic chorioamnionitis, the most common placental lesion in late spontaneous preterm birth, which is characterized by maternal T-cell infiltration of the chorion laeve with trophoblast apoptosis, resembles allograft rejection (44). Maternal sensitization to fetal HLAs is frequently found in patients with chronic chorioamnionitis, and is accompanied by complement deposition in umbilical vein endothelium (45, 46). A novel form of fetal systemic inflammation characterized by overexpression of T-cell chemokines (e.g., CXCL-10) (47) has been observed in chronic chorioamnionitis. Breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance may be particularly relevant to preterm labor occurring after fetal surgery or stem cell transplantation - interventions in which there is an increase in the number of maternal T-cells in the fetal circulation (48). The mechanisms linking disorders in tolerance and spontaneous preterm labor remain to be defined.

Decline in Progesterone Action

Progesterone is key to pregnancy maintenance, and a decline in progesterone action precedes labor in most species, which can be mediated by a reduction in serum levels of progesterone, local changes in metabolism, and/or alterations in receptor isoforms/co-activators (49, 50). The administration of progesterone receptor antagonists, such as mifepristone (RU-486), induces cervical ripening, spontaneous abortion, and labor in both animals and humans – hence the concept that a decline in progesterone may be responsible for some cases of preterm labor. Indeed, progesterone has effects on each component of the common pathway of parturition. Throughout gestation, progesterone promotes myometrial quiescence by reducing the expression of contraction-associated proteins (51) and inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-8, CCL2) (50). Near term, increased myometrial expression of miR-200 family members counteracts many actions of progesterone, increasing its catabolism and inducing expression of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines and prostaglandin synthase 2 (8). Progesterone’s effects on the decidua and chorioamniotic membranes include inhibition of basal- and TNFα-induced apoptosis, which protects the component cells from calcium-induced cell death and attenuates cytokine-induced MMP expression/activity (52). Progesterone has been implicated in the control of cervical ripening by regulating extracellular matrix metabolism (9). It is possible that the efficacy of progesterone in reducing preterm birth is due to a pharmacological effect rather than treatment of a progesterone deficiency.

Other Mechanisms of Disease

Uterine overdistension has been implicated in spontaneous preterm birth associated with multiple gestations and polyhydramnios (an excessive amount of amniotic fluid). In non-human primates, inflation of intra-amniotic balloons can stimulate uterine contractility, preterm labor, and an “inflammatory pulse,” which is characterized by increased maternal plasma concentrations of IL-β, TNFα, IL-8 and IL-6 (53). This finding is consistent with the observation that stretching human myometrium results in the overexpression of inflammatory cytokines. Maternal stress is also a risk factor for preterm birth. Stressful stimuli range from a heavy workload to anxiety and depression, occurring at any time during the preconceptional period and/or pregnancy. Stress signals increase the production of maternal and fetal cortisol, which in turn, stimulate placental production of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and its release into the maternal and fetal circulations (54).

Cell-free Fetal DNA

A role for cell-free fetal (cff) DNA as a signal for the onset of labor has recently been proposed (55). In pregnant women, cff DNA is normally present in the plasma, and concentrations increase as a function of gestational age - peaking at the end of pregnancy just prior to the onset of labor. cff DNA (in contrast with adult cell-free DNA) is hypomethylated, can engage TLR-9 (56, 57) and induce an inflammatory response. The downstream consequences could include activating the common pathway of labor. Interestingly, patients who have an elevation of cff DNA in the midtrimester are at increased risk for spontaneous preterm delivery later in gestation (58), and those with an episode of preterm labor and high plasma concentrations of cff DNA are also at increased risk for preterm delivery (59, 60). The concept that cff DNA can mediate a fetal/placental/maternal dialogue to signal the onset of labor in normal pregnancy as well as preterm labor after insult is a fascinating hypothesis worthy of investigation.

Progress in the Prevention of Spontaneous Preterm Birth

After decades of clinical and basic investigation, major progress has been made towards the prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth. The two most important predictors of spontaneous preterm birth are a sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester (61), and spontaneous preterm birth in a prior pregnancy. As for prevention, vaginal progesterone administered to asymptomatic women with a short cervix in the midtrimester reduces the rate of preterm birth < 33 weeks by 45%, and decreases the rate of neonatal complications, including neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (62). In women with a previous spontaneous preterm birth, the administration of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate reduces the rate of preterm birth <37 weeks by 34%, and decreases the need for oxygen supplementation (63). Cervical cerclage in patients with a previous spontaneous preterm birth and a short cervix reduces the rate of preterm birth <35 weeks by 30%, as well as composite perinatal mortality/morbidity. However, vaginal progesterone is as efficacious as cervical cerclage in these patients, and does not require anesthesia or a surgical procedure.

The combination of transvaginal ultrasound in the midtrimester to identify women with a short cervix and treatment with vaginal progesterone represents an important step in reducing the rate of preterm birth. This approach is anchored in the knowledge that progesterone plays a role in cervical ripening, and has the potential to save the U.S. health care system $500-750 million per year.

Looking Forward

Progress in the understanding and prevention of preterm labor will require recognition that preterm parturition has multiple etiologies, and further elucidation of the mechanisms underlying each. The definition of pathologic processes, identification of specific biomarkers, and implementation of therapeutic interventions within the unique complexity of pregnancy are particularly challenging. In pregnanacy, two individuals with different genomes and exposomes co-exist, largely with overlapping interests, but occasionally in potential conflict. Inaccessibility of the human fetus also poses a formidable obstacle to elucidating the physiology of in utero development, maternal responses to this process, and the changes in both when pathologic processes arise.

High-throughput techniques and systems biology can be used to improve the understanding of the preterm labor syndrome. Early studies using unbiased genomic/epigenomic (64-66), transcriptomic (67, 68), proteomic (69, 70), and metabolomic approaches (71) have been informative, yet require verification and validation. Progress will also depend on the generation and availability of multidimensional data sets, with detailed phenotypic characterization of disaggregated patient groups according to the mechanism of disease. Longitudinal studies are required to determine if any of the discriminators, at molecular or pathway levels, can serve as biomarkers during the preclinical disease stage, and enable risk assessment and/or non-invasive monitoring of fetal health and disease. The recent demonstration that in vivo monitoring of cell-free RNA during human pregnancy can provide information about fetal tissue-specific transcription is also an exciting development (72, 73). Since a stereotypic blood transcriptome has been identified in fetuses with acute and chronic placental inflammatory lesions, there are opportunities to determine if, and when, during the course of pregnancy, these changes can be detected in maternal blood. This information could have enormous diagnostic and prognostic value to inform the selection of therapeutic interventions. Thus, we envision that the goal of reducing the rate of spontaneous preterm birth will be grounded in a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of disease responsible for this syndrome.

Acknowledgements

The authors regret that due to page limitations, the contributions of many investigators to the study of parturition could not be credited in this article. The authors thank S. Curtis for editing the manuscript. The work of R. Romero is supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH/DHHS. Studies from SK Dey’s lab were supported in part by grants from the NIH (HD068524 and DA06668) and March of Dimes (21-FY12-127). The work of S. Fisher is supported by R37 HD076253 and U54 HD055764. We thank M. Gormely for assistance preparing the Figures.

References

- 1.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, et al. Lancet. 2012;379:2151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, et al. Lancet. 2012;379:2162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, Newton CR. Lancet. 2012;379:445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, et al. Lancet. 2012;380:2197. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrman RE, Butler AS, editors. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Lancet. 2008;371:75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, et al. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renthal NE, Williams KC, Mendelson CR. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:391. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahendroo M. Reproduction. 2012;143:429. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon R, Fortunato SJ. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:467. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore RM, Mansour JM, Redline RW, Mercer BM, et al. Placenta. 2006;27:1037. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero R, Gomez R, Chaiworapongsa T, Conoscenti G, et al. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(Suppl 2):41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madianos PN, Bobetsis YA, Offenbacher S. J Periodontol. 2013;84:S170. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elovitz MA, Wang Z, Chien EK, Rychlik DF, et al. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2103. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal V, Hirsch E. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:12. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carroll SG, Ville Y, Greenough A, Gamsu H, et al. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1995;72:F43. doi: 10.1136/fn.72.1.f43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannan S, Dai H, Navath RS, Balakrishnan B, et al. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:130ra46. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jobe AH. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51:7. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macones GA, Parry S, Elkousy M, Clothier B, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1504. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racicot K, Cardenas I, Wunsche V, Aldo P, et al. J Immunol. 2013;191:934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, Tarca AL, et al. Microbiome. 2014;2:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyman RW, Fukushima M, Jiang H, Fung E, et al. Reprod Sci. 2014;21:32. doi: 10.1177/1933719113488838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero R, Hassan S, Gajer P, Tarca AL, et al. Microbiome. 2014 doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Science. 1997;277:1669. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whidbey C, Harrell MI, Burnside K, Ngo L, et al. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anstee DJ. Blood. 2010;115:4635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonagh S, Maidji E, Ma W, Chang HT, et al. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:826. doi: 10.1086/422330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NICHD. [Accesed July 2014]. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/meetings/2014/Pages/052814.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, Korzeniewski SJ, et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/aji.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elovitz MA, Saunders T, Ascher-Landsberg J, Phillippe M. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:799. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han CS, Schatz F, Lockwood CJ. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:407. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YM, Bujold E, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1063. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00838-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, et al. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Tarca A, Kusanovic JP, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1122. doi: 10.3109/14767050902994838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirota Y, Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Xie H, et al. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:803. doi: 10.1172/JCI40051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha J, Bartos A, Egashira M, Haraguchi H, et al. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:4063. doi: 10.1172/JCI70098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erlebacher A. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:23. doi: 10.1038/nri3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mold JE, Michaelsson J, Burt TD, Muench MO, et al. Science. 2008;322:1562. doi: 10.1126/science.1164511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Way SS. Nature. 2012;490:102. doi: 10.1038/nature11462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim CJ, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Yoo W, et al. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1000. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J, Romero R, Xu Y, Kim JS, et al. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J, Romero R, Xu Y, Miranda J, et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:162. doi: 10.1111/aji.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee J, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Dong Z, et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:265. doi: 10.1111/aji.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wegorzewska M, Nijagal A, Wong CM, Le T, et al. J Immunol. 2014;192:1938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Condon JC, Hardy DB, Kovaric K, Mendelson CR. Molecular endocrinology. 2006;20:764. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan H, Yi L, Rote NS, Hurd WW, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E719. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shynlova O, Tsui P, Jaffer S, Lye SJ. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strauss JF., 3rd Reprod Sci. 2013;20:140. doi: 10.1177/1933719111424454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldorf KM, Sooranna S, Gravett M, Paolella L, et al. Reproductive Sciences. 2014;21:96A. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petraglia F, Imperatore A, Challis JR. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:783. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillippe M. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1404324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thaxton JE, Romero R, Sharma S. J Immunol. 2009;183:1144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scharfe-Nugent A, Corr SC, Carpenter SB, Keogh L, et al. J Immunol. 2012;188:5706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jakobsen TR, Clausen FB, Rode L, Dziegiel MH, et al. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:840. doi: 10.1002/pd.3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leung TN, Zhang J, Lau TK, Hjelm NM, et al. Lancet. 1998;352:1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farina A, LeShane ES, Romero R, Gomez R, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:421. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romero R, Yeo L, Miranda J, Hassan SS, et al. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:27. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, Tabor A, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:124e1. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, Dombrowski MP, et al. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang H, Ogawa M, Wood JR, Bartolomei MS, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1087. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muglia LJ, Katz M. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bezold KY, Karjalainen MK, Hallman M, Teramo K, et al. Genome Med. 2013;5:34. doi: 10.1186/gm438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heng YJ, Pennell CE, Chua HN, Perkins JE, et al. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haddad R, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:394e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gravett MG, Novy MJ, Rosenfeld RG, Reddy AP, et al. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:462. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esplin MS, Merrell K, Goldenberg R, Lai Y, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:391e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:1344. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.482618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koh W, Pan W, Gawad C, Fan HC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405528111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bianchi DW. Nat Med. 2012;18:1041. doi: 10.1038/nm.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]