To the Editor

In 2010, Xin et al. described a new autosomal-recessive syndrome which includes mental retardation, dysmorphism, skeletal and neurological findings in an Amish family secondary to mutations in the Transmembrane and coiled-coil domain-containing protein 1 (TMCO1) gene (1). Here, we report the first non-Amish case with a TMCO1 mutation. Our index case is a 7-year-old boy, SA (Fig. 1a, IV-3), who presented to paediatric neurology clinic due to delayed development (Fig. S1, Supporting information). His parents were first-cousins (Fig. 1a) and he was born at 37 weeks gestation with a head circumference of 38 cm (90%). SA was hypotonic at birth with feeding difficulties and was diagnosed with hypothyroidism. He later was found to have significant delays with the neurodevelopmental milestones, being unable to walk and with minimal speech. His family noted him to be anxious and showing self-mutilating behavior like chewing his fingers. When he was examined at the referring paediatric neurology clinic at 7 years of age, his head circumference was 53 cm (75–90%), his weight was 17 kg, (<5%) and height 113 cm (5%). His general physical examination was remarkable for several dysmorphic features including short neck, low hairline, low set ears, synophrys, hypertelorism, antevert nares, high-arched palate, prognatism, hyperextensbile fingers, pectus carinatum, scoliosis and genu varus. On neurological examination, he was awake but unable to speak except a few basic words. He was unable to walk, feed himself or perform activities of daily living. There were no abnormalities in routine laboratory tests, including complete blood count (CBC), blood chemistries, urine test, and plasma aminoacid levels. Chest X-ray was remarkable for rib and scapula abnormalities. On brain magnetic resonance imaging, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum and cerebellar herniation were detected (Fig. S2).

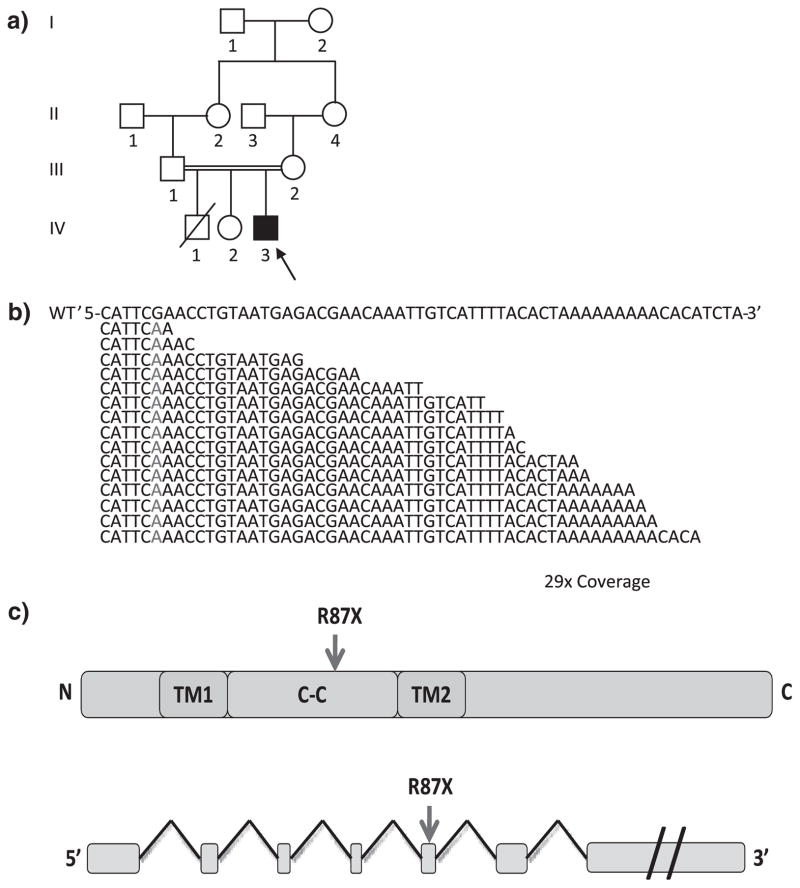

Fig. 1.

TMCO1 mutation in NG 109-1. (a) The pedigree structure of NG 109 (index case, NG 109-1, black arrow) is shown, which reveals a first cousin marriage. (b) Exome sequencing shows a G>A transition cause premature stop codon (marked in red, in the wild-type (WT) sequence on top) in the TMCO1. The depth of coverage across the variant was 29×, and all but one of the reads showed the deletion. (c) Representative TMCO1 structure and mutation location.

In order to identify the disease causing variant, we performed homozygosity mapping followed by whole exome sequencing using Nimblegen solid phase arrays (Roche NimbleGen, Inc., Madison, WI) and the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). We achieved a mean coverage of 30.5×, and 91.47% of all targeted bases were covered more than four times, sufficient to identify novel homozygous variants with high specificity (2) (Tables S1 and S2). We identified three novel homozygous missense variants and one novel homozygous nonsense mutation within the homozygosity intervals (Table S3). The nonsense mutation occurred in the 5th exon of the TMCO1 gene (R87X) (Fig. 1b,c). The mutation was confirmed to be homozygous in the affected subject and heterozygous in the one available parent sample based on Sanger sequencing (Fig. S3).

Our patient’s pre- and neonatal clinical and phenotypic findings were highly similar to that of 11 patients previously reported with the TMCO1 defect syndrome (1), with a few differences. Our case did not show craniosynostosis or spinal fusion, which occurred in 18% and 55%, of the original cases, respectively. Our case revealed more profound developmental impairment, being able to sit up at 5 years of age, and rolling over at 6 years of age, compared with the average ages of 11 and 19 months for these milestones in the original sample, respectively. The Amish patients were able to walk around at 36 months and talk at around 33 months while SA could not walk and was able to say a few basic words at 7 years of age.

In summary, we describe the 12th case of ‘TMCO1 defect syndrome’ in a child who is not Amish and has no ethnic or historical connection to the Amish population, suggesting that this syndrome may be more prevalent. Although the molecular function of the TMCO1 gene function is not fully understood, transcription studies revealed it to be highly expressed in human adult and fetal tissues indicating a critical role in human development (3). Further studies are needed for a mechanistic understanding of its biological function in cortical development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the family for participating in this study. This work was supported by the Yale Program on Neurogenetics and NIH grants RC2 NS070477 (to M. G.), the Yale Center for Mendelian Disorders, U54HG006504 (to R. P. Lifton, M. G., M. Gerstein and S. Mane) Gregory M. Kiez and Mehmet Kutman Foundation and The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) (to A. O. C.).

Footnotes

The following Supporting information is available for this article:

Fig. S1. Clinical images of patients NG 109-1, (a) general view of the patient (b) patient’s scoliosis. Pictures of patients are published with written informed consent from their parents.

Fig. S2. Midsagittal T1-weighted sagittal image shows a hypoplastic corpus callosum (a). Lateral ventricles are dysmorphic and parallel to each other on T2-weighted axial image (b). Coronal T2-weighted images demonstrate ‘Viking helmet’ sign on T2-weighted coronal images (c).

Fig. S3. Sequence traces of wild-type along with the index case. From up to down, the panels show the sequence traces in the patient’s and the mother’s and a control subject’s, respectively. The predicted amino acids corresponding to each codon are represented above the nucleotide sequences which are marked in bold letters above the chromatograms. For each sequence, the mutated base(s) are shown in red, as are resultant amino acid substitutions. For the wild-type sequences, the altered bases are shown in green. Note that the patient is homozygous for the mutations whereas mother’s heterozygous as we expected.

Table S1. Blocks of homozygosity in affected individual of family NG109.

Table S2. Coverage distributions and error rates across the whole exome and homozygosity intervals.

Table S3. Sensitivity and specificity for the detection of variants.

Table S4. Novel homozygous variants identified within the homozygosity intervals of NG 109-1.

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Xin B, Puffenberger EG, Turben S, Tan H, Zhou A, Wang H. Homozygous frameshift mutation in TMCO1 causes a syndrome with craniofacial dysmorphism, skeletal anomalies, and mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:258–263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908457107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilguvar K, Ozturk AK, Louvi A, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies recessive WDR62 mutations in severe brain malformations. Nature. 2010;467:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nature09327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, Mo D, Cong P, et al. Molecular cloning, expression patterns and subcellular localization of porcine TMCO1 gene. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37:1611–1618. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.