Abstract

This article describes a randomized controlled trial conducted to evaluate the effects of an intensive, individualized, Tier 3 reading intervention for second grade students who had previously experienced inadequate response to quality first grade classroom reading instruction (Tier 1) and supplemental small-group intervention (Tier 2). Also evaluated were cognitive characteristics of students with inadequate response to intensive Tier 3 intervention. Students were randomized to receive the research intervention (N = 47) or the instruction and intervention typically provided in their schools (N = 25). Results indicated that students who received the research intervention made significantly better growth than those who received typical school instruction on measures of word identification, phonemic decoding, and word reading fluency and on a measure of sentence- and paragraph-level reading comprehension. Treatment effects were smaller and not statistically significant on phonemic decoding efficiency, text reading fluency, and reading comprehension in extended text. Effect sizes for all outcomes except oral reading fluency met criteria for substantive importance; however, many of the students in the intervention continued to struggle. An evaluation of cognitive profiles of adequate and inadequate responders was consistent with a continuum of severity (as opposed to qualitative differences), showing greater language and reading impairment prior to the intervention in students who were inadequate responders.

Keywords: reading difficulties, reading intervention, response to intervention, Grade 2

Schools across the United States are increasingly providing multitiered reading interventions in the primary grades as a component of Response to Intervention (RTI) initiatives (Berkeley, Bender, Peaster, & Saunders, 2009). RTI models are schoolwide general education initiatives that include the provision of tiers of increasingly intensive intervention (Kovaleski & Black, 2010) if response is inadequate in less intensive tiers (Gersten et al., 2008). In typical RTI models that address reading difficulties in the primary grades, Tier 1 intervention is quality classroom reading instruction provided to all students using a research-validated core reading program, along with universal screening to identify students in need of supplemental intervention, progress monitoring assessments, and teacher professional development. Students identified as at risk for reading difficulties are provided with supplemental, short-term instructional interventions (Tier 2), and students with persistently inadequate response in Tier 2 are given more intensive Tier 3 intervention (Gersten et al., 2008). In the United States, data documenting a student’s response to evidence-based intervention can be used as part of the process of identification of a learning disability (Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 2004).

The intensity of interventions can be increased at Tier 3 by decreasing group size and increasing time in intervention (Vaughn, Denton, & Fletcher, 2010), by extending the duration of each lesson (e.g., from 45 min. to 2 hr), providing daily lessons, and providing intervention for several months or for more than 1 school year. Certain instructional characteristics have also been associated with increased intensity, including the frequency of teacher–student interactions (Warren, Fey, & Yoder, 2007) and the pacing of instruction both within and across lessons (Vaughn et al., 2010). Planning instruction to target specific student needs may also increase instructional intensity by increasing its efficiency.

Effects of Reading Intervention in the Primary Grades

There is a well-developed research base establishing the characteristics of effective early reading instruction (e.g., National Reading Panel, 2000; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002) and showing that most children can learn to read adequately, given quality classroom reading instruction (Torgesen, 2000). There is also converging research evidence supporting the effectiveness of supplemental small-group or individual reading intervention for primary-grade students for whom classroom reading instruction is insufficient (Al Otaiba & Torgesen, 2009; Torgesen, 2004; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007). Research supports the effectiveness of instructional practices to support development in word reading, fluency, and comprehension for students at-risk for reading difficulties in the primary grades. There is considerable evidence that providing explicit, teacher-directed instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, with the opportunity to apply skills in connected text with teacher feedback, is effective for improving word reading and word reading fluency (e.g., Blachman et al., 2004; Case et al., 2010; Denton et al., 2010; Gunn, Smolkowski, Biglan, Black, & Blair, 2005; Jenkins, Peyton, Sanders, & Vadasy, 2004; Mathes et al., 2005; Rashotte, MacPhee, & Torgesen, 2001; Scanlon, Vellutino, Small, Fanuele, & Sweeney, 2005; Torgesen et al., 2001; Torgesen, Wagner, Rashotte, Rose, et al., 1999; Vadasy, Sanders, & Tudor, 2007). Research suggests that text reading fluency is best supported through repeated or wide text reading practice with modeling and feedback (Chard, Vaughn, & Tyler, 2002; O’Connor, White, & Swanson, 2007; Vadasy & Sanders, 2008). Finally, explicit instruction in comprehension strategies has been shown to result in improved reading comprehension (Berkeley, Scruggs, & Mastropieri, 2010; Gajria, Jitendra, Sood, & Sacks, 2007; National Reading Panel, 2000).

Positive results have been reported by a number of experimental and quasi-experimental studies evaluating outcomes across two or more increasingly intensive tiers of reading intervention (Coyne, Kame’enui, Simmons, & Harn, 2004; Kamps et al., 2008; Mathes et al., 2005; O’Connor, Fulmer, Harty, & Bell, 2005; Simmons et al., 2008; Vadasy, Sanders, Peyton, & Jenkins, 2002; Vaughn et al., 2009). There have been fewer studies evaluating outcomes for primary-grade students who receive intensive intervention (usually Tier 3 in an RTI context) after demonstrating inadequate response in Tiers 1 and 2. These studies have had mixed results and have typically shown that outcomes within the Tier 3 group vary, with some students demonstrating significant gains while others make little or no progress, even in highly intensive intervention. For example, Vaughn et al. (2009) reported no significant main effects for Tier 3 intervention provided to students in Grade 2 who had demonstrated weak response to Tier 1 plus Tier 2 in first grade; however, they found that Tier 3 students who had started the intervention with the highest scores in oral reading fluency (ORF) improved significantly in both word reading and reading comprehension. In a study that examined four layers of intervention provided across kindergarten and first grade, O’Connor (2000) reported that some students moved in and out of the at-risk category but that overall the proportion of students who remained at-risk decreased as each layer of intervention was added. In a quasi-experimental study, Denton, Fletcher, Anthony, and Francis (2006) provided intervention to students with inadequate response to previous Tier 1 or Tier 1 plus Tier 2 intervention, along with a group of similarly impaired readers. Tier 3 intervention was provided in daily sessions that were 1– 2 hr long, resulting in strong mean growth in domains aligned with instruction; nevertheless, there were some students with weak response to this highly intensive intervention.

Cognitive Characteristics of Inadequate Responders

There is an emerging research base examining cognitive characteristics of students who do not respond adequately to Tier 2 intervention. To our knowledge, there are no studies of characteristics of inadequate responders to Tier 3 instruction, representing a potentially highly intractable group. After Tier 2 intervention, studies have generally identified inadequate responders as simply more impaired in both reading and cognitive skills, especially in the language domain (Al Otaiba & Fuchs, 2002; Fletcher et al., 2011; Nelson, Benner, & Gonzalez, 2003; Vellutino, Scanlon, Small, & Fanuele, 2006). A literature synthesis by Al Otaiba and Fuchs (2002) and a meta-analysis by Nelson et al. (2003) both showed that measures closely related to reading development (i.e., phonological awareness, rapid naming), along with general verbal skills (e.g., vocabulary), were most closely related to inadequate response. Fletcher et al. (2011) also found that phonological awareness and rapid naming were most related to inadequate response to Grade 1 Tier 2 intervention, with verbal knowledge and listening comprehension having smaller, but meaningful relations. Vellutino et al. (2006) classified students at the end of Grade 3 as poor readers who had been difficult and less difficult to remediate in Grade 1. The degree of impairment in rapid naming, phonological processing, vocabulary, and verbal knowledge in Grade 1 was linearly related to each group’s level of word reading skills in Grade 3. Vellutino et al. interpreted these results as indicative of a continuum of severity in which the same sets of variables are related to the ease and difficulty with which children learn to read. Like Fletcher et al. (2011), they found no evidence of qualitative differences in the cognitive attributes of adequate and inadequate responders, only evidence of levels of impairment of the same cognitive characteristics directly related to level of reading ability. What is unknown is whether this pattern is also evident in children with poor response to even intensive Tier 3 intervention, or whether these children have qualitatively different cognitive profiles from children who respond adequately to intensive intervention. Given the use of data documenting response to intervention in the identification of learning disabilities, this information has implications for classification and instruction.

Individualized Interventions

Early reading interventions vary in the degree to which instructional content and activities are standardized or individualized. Researchers conducting reading intervention studies have generally used highly standardized intervention programs to assure the provision of empirically validated instruction to all students (Al Otaiba & Torgesen, 2007). Individualized approaches take a more clinical approach, allowing a teacher to more precisely target the needs of specific learners based on diagnostic assessments. In individualized interventions, the amount of time dedicated to instruction in various reading domains, as well as the instructional content (e.g., specific sound-spelling patterns, fluency-building activities, comprehension strategies), instructional materials (supplying letter tiles for word building vs. writing words on paper), and instructional activities (e.g., activities designed to provide extra practice to bring skills to automaticity) may be differentiated according to student needs and strengths (Bryant, Smith, & Bryant, 2008). The flexibility afforded by individualized approaches may be important for students in Tier 3 interventions who have previously demonstrated poor response to evidence-based reading instruction; however, the effects of individualized reading interventions for primary-grade students have seldom been studied (Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007).

There is evidence that, when teachers individualize the amounts of code-focused (e.g., decoding, letter-sound correspondences, word recognition) and meaning-focused (e.g., comprehension, vocabulary, writing, text-based discussion) instruction provided to students in classroom reading programs, reading outcomes are improved for students in kindergarten (Al Otaiba et al., 2011), Grade 1 (Connor, Morrison, Fishman, Schatschneider, & Underwood, 2007, 2009), and Grade 3 (Connor et al., 2011). Other dimensions of instruction that were individualized in these studies were (a) the size of the instructional group and (b) whether activities were teacher directed or child directed (e.g., independent and small-group activities, peer tutoring). This line of research has shown that there are child-by-instruction interactions, such that students benefit from different instructional content and delivery depending on their word recognition skills and vocabulary knowledge and that optimal instructional approaches for individual students change across the school year.

Interventions designed for primary-grade students with persistent reading difficulties may need to take a more fine-grained approach to individualization. It is likely that the majority of poor readers in the early grades need some kind of code-focused instruction. Instruction for these students may be differentiated by determining more exactly what phonics and word recognition skills they know and what they need to learn based on diagnostic assessment. For example, a second grade student may know some letter-sound correspondences and recognize some high-frequency words, but struggle with others.

In this study, we evaluated the effects of an intervention that takes such a fine-grained approach. In this intervention, all teachers addressed word reading, fluency, text reading with comprehension, and writing daily; however, they determined the duration of each of these components, planned the instructional objectives for each, and selected from a list of instructional activities to implement during each component based on student data. We theorized that a program with this design would provide a supportive structure to aid lesson planning and provide sufficient specificity to ensure high-fidelity implementation but would also allow teachers the flexibility to individualize instruction, resulting in accelerated progress of students with persistent reading difficulties that are difficult to remediate.

Study Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of an individualized, intensive reading intervention for students in Grade 2 (or repeating Grade 1) who had demonstrated insufficient response to a highly standardized intervention provided the previous year in first grade. Although several researchers have reported improved outcomes for students who receive reading interventions, there is a need for experimental research examining outcomes specifically for students provided with Tier 3 intervention after demonstrating inadequate response in lower tiers (Denton, 2012). There is also a need for empirical evaluations of supplemental early reading interventions that allow for individualization to meet the needs of students with reading difficulties (Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007). Because of the current use of data documenting intervention response in the identification of learning disabilities, our second purpose was to identify what proportion of children respond adequately to Tier 3 intervention and to evaluate cognitive characteristics of children who demonstrated inadequate response.

We addressed three research questions: (a) Do students with persistent reading difficulties, who demonstrated inadequate response to quality classroom instruction and supplemental reading intervention provided in Grade 1, demonstrate significantly better outcomes in word reading accuracy, word reading efficiency, text reading fluency, comprehension of sentences and brief passages, and comprehension of extended text when provided with an intensive, individualized reading intervention compared with similar students who receive the reading instruction and intervention typically provided to at-risk readers in their schools? (b) Do a larger proportion of students who receive the research intervention meet benchmarks denoting adequate response to intervention, relative to students who receive typical school instruction? and (c) What baseline cognitive attributes distinguish children who respond adequately and inadequately to Tier 3 intervention? We hypothesized that students who received the research intervention would have better reading outcomes and a higher rate of positive response to intervention than those who received typical school instruction. We also hypothesized that students who responded inadequately to Tier 3 intervention would have cognitive characteristics consistent with those identified in poor responders to Tier 2 intervention and would thus be primarily impaired in language domains, specifically vocabulary and general concept knowledge, phonological awareness, rapid retrieval of verbal information, and listening comprehension. Finally, we hypothesized that nonverbal reasoning would not distinguish the Tier 3 adequate and inadequate responders, as this would indicate more global impairment rather than language-based impairment.

Method

Participants

Schools and context

This study was conducted in 10 elementary schools located in the southwestern United States. Four were part of a school district located near a small city. During the year of the study, the populations of participating schools in this district were primarily Hispanic (81%), with 12% African American, 6% White, and 1% Asian and other ethnicities; about 89% of the students attending these schools qualified for free or reduced-price lunch (an indication of low socioeconomic status). The other six schools were located in a large urban school district about 150 miles from the smaller district. The populations of the participating schools in this district were predominantly African American (55%) and Hispanic (31%), with 10% White and 5% Asian and other ethnicities; about 77% of students in these schools qualified for free or reduced-priced lunch.

Student participants

The participants in this study were 72 students who had received Tier 1 first grade classroom instruction along with Tier 2 supplemental reading intervention during the previous year but had not met year-end criteria for adequate intervention response (Denton et al., 2011). First we describe the process of identification of the full cohort who received Tiers 1 and 2 in first grade and then those participating in the current study. For clarity, we refer to the current study as the Grade 2 study, although some participants were retained in and repeating first grade when they received the Tier 3 intervention.

Grade 1 intervention

In fall of first grade, 680 students were screened to identify those at-risk for reading difficulties. Of these, 461 failed to meet criteria on the screen and were considered potentially at-risk; their progress was monitored in Tier 1 using ORF measures for 8 weeks. At that time, the data indicated that 273 students had made insufficient progress in Tier 1 and were thus determined to be in need of Tier 2 intervention. The number of children identified exceeded available resources, so a subset was randomly selected to receive Tier 2 intervention. This process resulted in a group of 218 students considered at risk for reading difficulties and assigned to receive Tier 2 supplemental intervention; 193 of these completed the intervention. Students were excluded from the study if they received their primary reading instruction outside the regular general education classroom or in a language other than English or had school-identified severe intellectual disabilities or severe emotional disturbance. The Tier 2 intervention was highly standardized, consisting of a manualized adaptation of a well-specified early reading program with a strong emphasis on decoding, word recognition, and fluent reading, and secondary emphasis on vocabulary and comprehension (Sprick, Howard, & Fidanque, 1998). The Tier 1 and Tier 2 interventions, and their effects, are described in detail in Denton et al. (2011).

Grade 2 study sample

In May of Grade 1, we applied fluency and decoding criteria to identify students from this group of 193 who demonstrated inadequate response to the Tier 1 plus Tier 2 interventions. Students were considered inadequate responders to intervention if they met any one of the following criteria (or their combinations) at the end of first grade: (a) standard score equal to or below 93 on the Woodcock–Johnson III (WJ III; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) Basic Reading Skills composite, (b) standard score equal to or below 90 on the Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE; Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999) composite, or (c) ORF equal to or below 20 words correct per minute (wcpm). Of the 193 students who completed Tier 2 intervention, 105 were classified as inadequate responders to Tiers 1 and 2. Of these, 103 participated in the current study and were randomly assigned at the end of Grade 1 to receive the research Tier 3 intervention the following school year (Tier 3 group) or to a Typical School Instruction (TSI) comparison group. In order to maximize the number of students who received intervention and ensure that the intervention group was large enough to evaluate response, we randomized students in a 2:1 ratio. To control for school-level effects, we randomized students within their schools.

Effects of attrition

Twenty-eight students (of the 103 students randomized to treatment) were lost to attrition either before (i.e., during the summer break) or during the school year in which Tier 3 intervention was provided. To examine the effects of attrition, we compared these students to the 75 who remained in the study. The attritted and nonattritted students differed in racial distribution, χ2(3) = 8.37, p < .05. Among the attritted students, 64% were African American, 21% Hispanic, and 14% White. Among the nonattritted students, 35% were African American, 49% Hispanic, and 15% White. The two groups did not differ in (a) treatment assignment (Tier 3 vs. TSI), χ2(1) = 0.06, p > .05; (b) gender, χ2(1) = 0.83, p > .05; (c) site, χ2(1) = 0.55, p > .05; (d) free lunch status, χ2(1) = 2.74, p > .05; or (e) age, t(101) = 1.12, p > .05; nor did they differ on scores on Kaufmann Brief Intelligence Test 2 (KBIT 2; Kaufmann & Kaufmann, 2004) Verbal Knowledge, t(101) = −1.03, p > .05; TOWRE, t(101) = 0.50, p > .05; WJ III Basic Reading Skills, t(101) = 1.07, p > .05; or WJ III Passage Comprehension, t(101) = 0.24, p > .05.

Intent-to-treat sample

Three of the 75 students did not receive their assigned treatments. One student was assigned to the TSI condition but inadvertently was provided with the experimental Tier 3 intervention. Two students were assigned to Tier 3 intervention but did not receive intervention because of scheduling conflicts. Two sets of analyses were conducted: one set on the intent-to-treat sample (N = 75), in which students were analyzed according to their original treatment assignments regardless of the actual treatment received, and the second set on the final analyses sample (N = 72), which included only the students who completed treatment as originally assigned. Both sets of analyses included t tests on pretest measures to determine if the two treatment groups differed on beginning of year performance and repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to determine if treatment influenced gains in achievement. There were no differences between the intent-to-treat sample and the final analysis sample in the treatment effects. Therefore, the reported results of all subsequent analyses are based on the final analysis sample (N = 72), with 47 students in the Tier 3 group and 25 in the TSI group.

Table 1 illustrates the demographic characteristics of students assigned to each research condition. There were no significant demographic differences between TSI and Tier 3 students on age: t(70) = −0.95, p > .05; gender: χ2(1) = 0.33, p > .05; race/ ethnicity: χ2(3) = 4.10, p > .05; free or reduced-price lunch eligibility: χ2(1) = 0.29, p > .05; site: χ2(1) = 0.20, p > .05; limited English proficiency status: χ2(1) = 0.03, p > .05; or special education status: χ2(1) = 0.09, p > .05. The difference in the number of students repeating Grade 1 across groups was marginally significant, χ2 (1) = 3.76, p < .06.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Treatment Condition

| Demographic | Tier 3 (n = 47)

|

TSI (n = 25)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years (SD) | % | Years (SD) | % | |

| Mean age (SD) | 7.8 (0.5) | 7.7 (0.4) | ||

| Female | 51 | 44 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 28 | 48 | ||

| Hispanic | 57 | 36 | ||

| White | 13 | 16 | ||

| American Indian | 2 | 0 | ||

| Free/reduced-price lunch | 79 | 84 | ||

| Special educationa | 31 | 35 | ||

| Limited English proficiency | 30 | 28 | ||

| Repeating Grade 1 | 21 | 4 | ||

| Urban site | 43 | 48 | ||

Note. There were no significant differences between groups as evaluated by chi-square analyses and t test (p > .05). TSI = typical school instruction.

No data available for two Tier 3 and two TSI students.

Interventionists

Tier 3 intervention was provided by six interventionists who were certified teachers or experienced clinical reading tutors. All were selected, trained, and supervised by the researchers. Three held master’s degrees, and three held bachelor’s degrees. All were White women who had prior experience teaching students with reading difficulties (M = 9.83 years, SD = 11.05). Interventionists received approximately 18 hr of training in the intervention procedures at the beginning of the school year and an additional 6 hr of training at midyear. Ongoing professional development was provided through weekly meetings, which became biweekly as the interventionists became more proficient, totaling about 22 hr. Interventionists also received frequent informal observations and coaching sessions.

Description of Intervention

Participants who were randomly assigned to the Tier 3 group were provided with daily intervention in 45-min sessions over 24–26 weeks from October through May. Intervention was provided in groups of two or three students during the school day in a location in children’s home schools but outside the regular classroom. Students received intervention on an average of 102.1 days (SD 9.2; range 68.5–116; approximately 76.5 hr). The primary intervention program was an adaptation of Responsive Reading Instruction (RRI; Denton & Hocker, 2006). An adaptation of a separate fluency-oriented program, Read Naturally (RN; Ihnot, Matsoff, Gavin, & Hendrickson, 2001), was incorporated for students who needed increased emphasis on fluency.

RRI provides a flexible framework for providing supplemental reading intervention in the early grades. Each RRI lesson addresses word study, ORF, reading comprehension, the application of skills and strategies while reading connected text, and written response to text. Within this framework, teachers determine individualized instructional objectives based on diagnostic assessments of their students’ strengths and needs. RRI provides a menu of instructional and practice activities from which teachers select as they plan daily lessons designed to target their students’ needs (see the Appendix). Procedures for each of these activities are described in detail in the RRI handbook. Instructional activities include explicit modeling of skills and strategies with guided practice and independent practice; other activities provide opportunities for extended practice and for application of skills and strategies in reading and writing. A key component of the intervention is the provision of instructional scaffolding, and the description of each activity includes suggestions for scaffolding student responses. Teachers in this study were provided with DVDs containing video clips illustrating the implementation of most of the RRI activities. RRI also includes a guide to assist teachers in selecting appropriate activities to address specific student needs (e.g., activities for a student who fails to self-correct their errors or a student who can produce the sounds of letters but has problems blending the sounds to read unknown words). The published RRI program was adapted for this study by adding activities addressing reading and spelling multisyllable words with common syllable patterns; additional fluency and comprehension activities were also added. The Appendix lists all activities available to teachers in this study. Descriptions of lesson components follow.

Word study

Teachers used a variety of instructional activities to provide explicit instruction and practice in phonological awareness, letter-sound correspondences, high-frequency word recognition, phonemic decoding, structural analysis, and spelling, depending on student needs (see the Appendix). Teachers followed a prespecified order for introducing letter-sound correspondences, orthographic patterns, and irregular words but taught only those items needed by their students based on frequent assessment of knowledge and skills in each area. Word study included a variety of practice activities designed to foster active student involvement. Instruction was fast-paced, with between three and five different activities included in a typical 10-min segment. During the first half of the intervention, all students received word study instruction, as all needed improvement in accurate and fluent word identification. During the second half of the intervention, some had decreased emphasis on decoding, with significantly more lesson time devoted to instruction in fluency and comprehension.

Fluency

Teachers provided instruction designed to support the development of fluent reading in increasingly challenging text, including modeling of phrased, expressive reading and repeated oral text reading with and without teacher feedback. Students practiced oral reading individually with the teacher, independently, and in pairs. Some students also practiced reading lists of words with common sound–spelling patterns until they met goals for fluency and accuracy.

Assessment

Each day, teachers individually assessed one student in the group while the other students engaged in partner reading or individual reading practice for fluency (3–5 min). Teachers selected one assessment per week for each student from a variety of brief assessments available to them, depending on the information they needed to plan instruction (see the Appendix). All assessments were closely aligned with program objectives.

Supported oral reading and reading comprehension

Each day, teachers provided interactive modeling, scaffolding, and feedback as students read increasingly difficult text. To identify unknown words, students were taught to look for recognizable orthographic and morphemic patterns (e.g., letter combinations, affixes) and then to use phoneme–grapheme associations to “sound out” words. Students were discouraged from using pictures or context to identify words, but they were taught to use context to self-monitor and self-correct errors. Text was matched to students’ reading levels and was not decodable using instructed letters and words; teachers primarily used books that were leveled according to the Fountas and Pinnell (1999) system.

Daily text reading included integrated comprehension instruction. Before reading, teachers provided a brief text introduction focused on a particular comprehension skill and set a purpose for reading with a guiding question related to this skill; teachers and students discussed the question briefly during and after reading. In the supported writing component of the lesson, students wrote a response to the guiding question. Teachers could also plan brief instructional activities to support text reading; for example, students could play a game in which they determined whether orally presented sentences “make sense” or “do not make sense” to support comprehension self-monitoring.

Supported writing

Each day, students wrote one or more complete sentences in response to the book’s guiding question. With teacher scaffolding, students applied skills in phonemic analysis and knowledge of orthographic patterns to spell words and write them accurately. The resulting sentence was correctly written, with appropriate punctuation and capitalization. In later lessons, students were taught how to edit their writing.

Additional fluency instruction

In the second half of the intervention period, teachers could reduce the time devoted to word study instruction and incorporate a second published program, an adaptation of RN (Ihnot et al., 2001), for students whose decoding was adequate but who needed more intensive support in fluency. The primary components of RN are (a) reading along with a model of fluent reading (provided by an audio or computerized recording or the teacher; b) repeated reading of instructional-level expository passages, and (c) goal setting and progress monitoring (i.e., repeatedly measuring and graphing ORF rates and comparing rates to preset goals). For each RN passage, students followed a sequence of procedures until established criteria were met, including achievement of a fluency goal, acceptable accuracy, and appropriate pausing at the ends of sentences. Depending on students’ needs, some also responded to written or oral comprehension questions about each passage.

Motivation

Student motivation was addressed primarily by planning instruction and selecting text that was at an appropriate level of difficulty and by providing instructional scaffolding so that students had to put forth effort to complete tasks but were usually successful. Teachers gave specific praise that highlighted successful responses. Motivation and engagement were also fostered by planning hands-on activities and keeping lesson pacing brisk. When needed, teachers implemented a behavior game in which students were awarded points when they followed rules and participated actively, and the teacher received points when they did not. Students could earn stickers or other small prizes on days when their group “beat the teacher.” To support motivation in RN sessions, teachers affixed a sticker on a reward chart each time students met criteria on a passage; when a specified number of stickers had been earned, students were allowed to select a small prize from the teacher’s “treasure chest.”

Individualizing instruction

Interventionists were provided with graphs of students’ progress in ORF, and coaches on the research staff assisted them in adjusting instruction when students made insufficient progress. Although students’ ORF was monitored less frequently in this study (i.e., every 4 weeks) than often recommended for Tier 3 students, they received frequent diagnostic assessment, as described earlier. Teachers were trained and received ongoing coaching support in making data-based decisions and had many options for instructional and practice activities that they could incorporate into their lessons to address individual students’ objectives in various ways (see the Appendix).

Individualization of instruction was accomplished through both planning and implementation. Planning instruction entailed (a) determination of the instructional content (e.g., specific sound-spelling correspondences to be taught and practiced; the comprehension skill to be emphasized in text reading; emphasis on comprehension monitoring, word identification strategies, or self-correction of errors during text reading), (b) selection of the instructional activities to be used to teach or practice this content (from the list in the Appendix), (c) selection of appropriate new instructional-level text, and (d) development of an introduction to the text and a guiding question for comprehension instruction. During the lesson, individualization included (a) the provision of deliberate instructional scaffolding and positive and corrective feedback and (b) the regulation of pacing throughout the lesson, including repeated modeling and provision of extra practice opportunities when needed.

Individualization of instruction for students served in small groups rather than in one-to-one formats entails a degree of compromise. This issue was addressed in two ways in this study. First, students were grouped as homogeneously as possible and were regrouped when possible if the rates of progress of students within a group diverged. Second, teachers planned lessons specifically designed for one student in the group each day (the “Star Reader”), rotating systematically among the students in the group. Each day, one student in the group was designated the Star Reader; this student sat in a specific chair next to the teacher and received individualized attention in several ways. The teacher planned each daily lesson specifically with the Star Reader in mind, selecting lesson objectives and instructional activities within each lesson component (e.g., word study, fluency) to address the needs of this student and selecting text at this student’s level. Each student had the opportunity to be the Star Reader at least 1 day per week. Table 2 describes in greater detail the individualized instruction provided to this daily focus student during each lesson component and the instruction provided to other students in the group when they were not the Star Reader.

Table 2.

Instruction and Practice Activities Provided to a Daily Focus Student and Other Students During Each Component of the Intervention

| Component | Daily focus student | Other students in the group |

|---|---|---|

| Word Study | Activities and instructional content (e.g., new letter-sounds, irregular words taught) planned with the focus student in mind. | All students participate in all activities; students for whom the content is difficult receive support from teacher to enable success; teacher monitors responses, adjusts pace of instruction, and provides additional modeling and scaffolding when needed. |

| Fluency | Focus student spends 3–5 min rereading familiar text individually with the teacher while the teacher provides modeling and prompting for fluent reading. | All students practice orally rereading familiar text with partners or individually. |

| Supported Reading and Comprehension | During the first 3–5 min, focus student reads a portion of the new book to the teacher (and the group), as the teacher provides modeling, scaffolding, and feedback to support application of word reading strategies and skills, self- monitoring of meaning, and self-correction of errors. | All students read the remainder of the book chorally or individually; all participate in comprehension instruction and discussion; as time allows, all students reread all or part of the book for fluency. |

| Supported Writing | The focus student orally composes a complete sentence, with teacher support if needed, to respond to a comprehension question about the book just read. | All students repeat the focus student’s sentence and write the same sentence in their journals. After the early lessons, each student may add a second sentence that he or she composes. All students receive instruction in using sound analysis to spell words, spelling irregular words, and editing their writing. |

Fidelity of implementation

Project coordinators conducted direct observations of the intervention lessons to verify fidelity of implementation on five occasions across the school year using a protocol designed to reflect key features of the intervention. At each time point, each interventionist was observed during an entire small-group session using a form developed to capture ratings of adherence to prescribed program procedures and quality of implementation. Cross-site observations were held on two occasions in order to establish interobserver reliability and promote consistent implementation across sites. Observers co-observed live lessons and discussed differences in coding and then repeated the process until they reached at least 85% absolute agreement (i.e., number of agreements divided by total ratings).

Adherence to the program procedures was coded by rating each of the individual instructional activities (e.g., letter-sound instruction, high-frequency word instruction; repeated reading for fluency) on a 3-point Likert-type rating scale (with 3 being the highest); then each teacher’s score was calculated as a percentage of a “perfect” score. Program adherence was defined as implementing the activity according to the described procedures in the RRI handbook, appropriate provision of scaffolding, appropriate lesson pacing, and student on-task participation. Adherence also included providing each lesson component (e.g., word study, fluency) for the appropriate number of minutes during the lesson. The mean program adherence score across intervention components and across tutors was 93% (SD = 0.07).

Quality of implementation was rated globally for overall lessons on a 2-point scale (yes–no), and percentages of a perfect score were similarly calculated. Items included (a) organization of materials to maximize instructional time, (b) appropriate student seating arrangement, (c) warmth and enthusiasm displayed toward students, (d) monitoring student responses and providing positive and corrective feedback, (e) clear communication of expectations for each activity, and (f) recording student responses on anecdotal records throughout the lesson. The mean quality score across components and across teachers was 99% (SD = 0.02).

School-provided reading instruction

All study participants received regular daily classroom reading instruction. Classroom reading teachers received graphs of scores on researcher-collected repeated measures of oral reading fluency for all student participants in their classrooms (i.e., both treatment and comparison group students) along with instructions for interpreting these graphs to determine whether students were on-track to meet year-end benchmarks.

As a component of typical school practice, some participants received supplemental reading intervention provided by their schools in addition to classroom reading instruction, outside of the researcher-provided intervention. To document the nature and amount of this additional reading instruction, we conducted structured interviews of the classroom teachers of all participating students. During the intervention period, 16 students in the TSI group (64%) received school-provided reading intervention, including occasional tutoring and regularly scheduled small-group lessons. These 16 students received an average of 70.3 hr of intervention (SD = 66.8; range 10.4–236.3 hr). Six received intervention from a dyslexia specialist or designated reading interventionist, and 11 received intervention from their regular classroom teachers (one received intervention from both a reading interventionist and the classroom teacher). Teachers reported using a variety of materials to provide the tutoring, and several students received tutoring provided with more than one type of materials or approach (so the following numbers total more than 16). Three students received tutoring using an explicit multisensory dyslexia program, and five received other phonics instruction. One student received one-to-one intervention using the Reading Recovery program (Clay, 2005), and another student received a comprehensive explicit reading intervention program. Six received tutoring using their regular core classroom reading programs, and six received guided reading lessons. Six students received fluency-oriented intervention, including three whose teacher reported using the RN program (a component of the research Tier 3 intervention), but the extent to which this program was used with these comparison group students is not known.

During the same period, concurrent with the researcher-provided intervention, eight Tier 3 students (17%) received an average of 15.2 hr of school-provided reading intervention (SD = 10.5; range 2.1–27.1 hr) consisting primarily of intermittent small-group tutoring. None of this intervention was provided by a designated reading specialist; five students were tutored by their classroom teachers and three by paraprofessionals. Five students were tutored using their classroom core reading programs, and one received guided reading lessons. Teachers provided intervention to two students using fluency-oriented programs and to one student using a phonics program. Two teachers used English language arts workbooks. None of the Tier 3 students received school-provided intervention using comprehensive supplemental intervention programs.

Measures

We measured student outcomes in word reading, word reading efficiency, text reading fluency, comprehension of sentences and brief passages, and comprehension of extended text. In addition, we measured cognitive variables hypothesized to be related to responsiveness to Tier 3 intervention.

Outcome measures

Word reading accuracy for real words and pseudowords was measured with the Letter–Word Identification and Word Attack subtests of the WJ III. Test–retest reliabilities are .85 and .81 for the two subtests, respectively, at the age of interest (McGrew & Woodcock, 2001). Standard scores were evaluated in the analyses.

The Sight Word Efficiency and Phonemic Decoding Efficiency subtests of the TOWRE were used to assess word reading efficiency. Students read lists of real words and pseudowords, and the raw score is the number of words or nonwords read correctly in 45 s. Alternate forms reliability exceeds .90, and test–retest reliabilities range from .83 to .96 (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999). Standard scores were evaluated in the analyses.

The Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) subtest from the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2002) assessed reading fluency in connected text. Test–retest reliabilities range from .92 to .97. Raw scores (words read correctly per minute) were evaluated in the analyses.

Reading comprehension was measured using the WJ III Passage Comprehension subtest and the Gates–MacGinitie Reading Comprehension subtest (GM Comprehension; Gates; MacGinitie, MacGinitie, Maria, Dryer, & Hughes, 2000). WJ III Passage Comprehension is a close-based assessment in which students read brief sentences or paragraphs and supply missing words. Test–retest reliability is .86 (McGrew & Woodcock, 2001). The standard score was the primary dependent measure. GM Reading Comprehension involves reading a passage and responding to multiple-choice questions. The coefficient alpha in second grade is .92 in the fall and .93 in the spring (MacGinitie et al.). The percentile score was the primary dependent measure.

Cognitive measures

Based on prior assessments of the cognitive attributes of Tier 2 inadequate responders (e.g., Fletcher et al., 2011; Vellutino et al., 2006), we evaluated adequate versus inadequate responder profiles using measures of (a) receptive vocabulary and general knowledge, (b) phonological awareness, (c) rapid retrieval of letter names in a repeated array, (d) listening comprehension in elaborated text, and (e) listening comprehension with heavy demands on working memory, operationalized as the ability to understand and follow increasing complex oral directions. We also measured nonverbal reasoning to rule out general low ability as contrasted with difficulties in language domains.

We administered the KBIT–2 Verbal Knowledge subtest as an assessment of receptive vocabulary and general knowledge and KBIT–2 Matrices as a measure of nonverbal reasoning. The KBIT–2 is an individually administered intellectual screening measure. In the Verbal Knowledge subtest, the participant is required to choose one of six illustrations that best responds to an examiner question. Internal consistency ranges from .86 to .89. The KBIT–2 Matrices subtest requires students to choose a diagram that either “goes with” a series of other diagrams, completes a series, or completes a 2 × 2 analogy. Internal consistency ranges from .87 to .89 for students’ between the ages of 6 and 8 years. Standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15) for both Verbal Knowledge and Matrices were used in the analyses.

Phonological awareness was represented by two subtests of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999): Blending Words and Elision. The Blending Words subtest measures students’ ability to orally combine separately pronounced phonemes to form whole words. The coefficient alphas range from .79 to .89. The Elision subtest measures the extent to which an individual can first say a word and then say what remains after deleting specific sounds from the word. The coefficient alphas range from .89 to .92. For the analyses, the scaled scores (M = 10, SD = 3) for Blending Words and Elision were averaged to form a Phonological Awareness Composite (PA) and then converted to standard scores. We also administered the Rapid Naming of Letters (RAN) subtest of the CTOPP. The CTOPP RAN Letters measures the speed of naming repeated letters. To reduce assessment time, we administered Form A, so a norm-referenced score could not be computed. The score used for analysis was time per letter, computed as the number of letters identified divided by the total time to identify all items. Alternate form and test–retest reliability coefficients are at or above .90 for students in the age range of this study.

We measured listening comprehension with two subtests of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–4 (CELF–4; Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003), a norm-referenced assessment of language abilities. The CELF–4 Concepts and Directions subtest (CFD) measures listening comprehension and puts high demands on verbal working memory; it assesses the ability to understand, recall, and execute oral commands containing syntactic structures that increase in length and complexity. The coefficient alphas range from .91 to .92. The Understanding Spoken Paragraphs (USP) subtest is a three-paragraph, 15-item assessment that evaluates the ability to understand oral narrative texts. Questions probe for understanding of the main idea, understanding and memory of important details, the sequence of events, and the ability to make predications and inferences. The coefficient alphas range from .64 to .74. Scaled scores for these measures were converted to standard scores for the analyses.

Test Administration Procedures

We assessed reading performance prior to the onset of Tier 3 intervention in September of Grade 2 and at posttest in May of second grade. We administered the DIBELS ORF measure approximately every 4 weeks throughout the intervention to monitor progress. The cognitive tasks were administered in December of Grade 1, except for KBIT–2 Matrices, which was administered in May of Grade 1. All assessments were administered by examiners who completed an extensive assessment training program. A manual for training and test administration was developed and used to train the examiners in a 3-day workshop that included observation of test administration and practice. Prior to assessing a child, each examiner administered the test to the coordinator, who used a checklist to ensure that the examiners followed appropriate procedures. The assessment coordinators were present in all schools during the assessment periods and observed examiners at work. All assessments were completed in the students’ elementary schools in quiet locations.

Analyses

To address Research Question 1, we conducted analyses using a repeated-measures ANOVA to evaluate reading gains and factors that influenced gains. First, we evaluated treatment effects and calculated effect sizes by dividing the difference in gain scores by the pooled standard deviation corrected for the correlation between the pre- and posttest (the SD of the gain ; McGaw & Glass, 1980). For DIBELS ORF, we first included all data points in the analysis, finding that the results were the same when we analyzed only pretest and posttest data. Since there were missing data for some participants on the progress monitoring assessments, we report results on pre–post differences. Next, we evaluated instructional variables to determine if these factors influenced reading gains.

Because our sample was composed of students with inadequate response to previous intervention, the sample size was small. Given this small sample size, we had competing concerns regarding the multiple outcomes that we were evaluating causing inflated Type 1 error and the inflation of Type 2 error that results from the application of corrections in alpha for multiple comparisons. To illustrate, Schochet (2008) reported on a simulation that demonstrated that if an experiment has the statistical power to detect real differences at .80 for an individual measure, that power is reduced to .59 if Bonferroni corrections are applied to account for the analyses of five outcome measures. To balance these concerns, we grouped our outcomes into domains consistent with the hypothesized effects of the intervention: word reading, word reading efficiency, text reading fluency, comprehension of sentences and brief passages, and comprehension of extended text, and evaluated measures of each domain with an alpha of .05. For word reading and word reading efficiency, if there were statistically significant group differences, we then examined subcomponents (WJ III Letter–Word Identification and Word Attack; TOWRE Phonemic Decoding Efficiency and Sight Word Efficiency) to determine if the intervention influenced specific aspects of each domain). Finally, we adopted the practices of the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse (WWC; U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2011) and examined effect sizes for all measures (regardless of statistical significance) to determine whether the group differences were substantively important; we applied the WWC criteria of considering effect sizes greater than or equal to the absolute value of .25 as indicators of substantive importance.

A second concern was the potential for dependency due to the nesting of students within classroom and intervention groups. At this level of nesting, there were 52 classroom (TSI) and classroom/ intervention (Tier 3) clusters with between one and four students per cluster. The small sample made estimating multilevel models problematic. However, we examined intraclass correlations (ICCs) of the posttest performance controlling for pretest performance to determine if there were clustering effects at this level. For all outcomes except WJ III Letter–Word Identification and GM Passage Comprehension, the ICCs were 0. For WJ III Letter–Word Identification, the ICC was .50, and for GM Passage Comprehension, it was .11. In the case of the GM, the between cluster variance was not statistically significant (p > .05). The between cluster variance in these cases did not meaningfully change the effects reported (i.e., the intervention had a statistically significant effect on WJ III Letter–Word Identification but not GM Passage Comprehension; discussed later).

To address Research Question 2, we conducted chi-square analyses to determine if there were group differences in responder status. To address the third research question, we compared cognitive profiles of adequate versus inadequate responders among the Tier 3 students who received intervention. We used the multivariate methods described by Fletcher et al. (2011), which were derived from Huberty and Olejnik (2006), to conduct a descriptive discriminant analysis. Thus, we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to determine if Tier 3 adequate responders differed from inadequate responders on measures of vocabulary and verbal knowledge, nonverbal reasoning, phonological awareness, listening comprehension/working memory, and listening comprehension. We then interpreted the discriminant function maximally separating groups on these variables.

Results

We compared pretest means using t tests to determine if Tier 3 and TSI students differed on beginning of year performance. As expected, given the randomized assignment of students to treatment conditions, there were no significant differences in pretreatment performance on any of the achievement measures (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre- and Posttest Means by Treatment Group and Effect Sizes

| Measure | Time | Group

|

t/Fa | Effect sizeb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 3

|

Typical school instruction

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| WJ III Basic Reading | Pre | 90.17 | 12.23 | 91.76 | 8.33 | 0.58 | |

| Post | 94.34 | 9.82 | 90.32 | 9.18 | 8.13* | .56 | |

| WJ III Letter–Word Identification | Pre | 87.62 | 12.62 | 90.04 | 9.49 | 0.84 | |

| Post | 91.96 | 9.63 | 89.68 | 9.48 | 7.90* | .44 | |

| WJ III Word Attack | Pre | 94.15 | 11.67 | 95.04 | 8.79 | 0.33 | |

| Post | 98.06 | 10.78 | 92.20 | 10.11 | 5.78* | .65 | |

| TOWRE Word Reading Efficiency | Pre | 80.47 | 10.17 | 81.80 | 9.62 | 0.54 | |

| Post | 88.91 | 12.44 | 85.60 | 9.62 | 4.35* | .42 | |

| TOWRE Phonemic Decoding Efficiency | Pre | 85.57 | 7.54 | 85.52 | 7.14 | −0.03 | |

| Post | 91.36 | 9.38 | 88.00 | 7.14 | 2.25 | .40 | |

| TOWRE Sight Word Efficiency | Pre | 81.79 | 10.76 | 84.16 | 10.40 | 0.90 | |

| Post | 90.21 | 12.65 | 88.12 | 10.04 | 5.07* | .39 | |

| DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency | Pre | 18.15 | 10.23 | 17.08 | 12.50 | −0.39 | |

| Post | 51.28 | 23.50 | 47.32 | 23.24 | 0.41 | .12 | |

| WJ III Passage Comprehension | Pre | 82.06 | 9.75 | 84.48 | 7.89 | 1.07 | |

| Post | 87.55 | 8.63 | 86.92 | 8.82 | 3.95* | .34 | |

| Gates Passage Comprehension | Pre | 12.87 | 15.21 | 11.36 | 9.79 | −0.45 | |

| Post | 20.91 | 18.57 | 13.80 | 15.29 | 1.60 | .35 | |

Note. Typical school instruction (TSI) n = 25 for all measures; Tier 3 n = 47 for all measures except Gates and DIBELS posttest; for these measures, n = 46. WJ III = Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Achievement; TOWRE = Test of Word Reading Efficiency; DIBELS = Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills; Gates = Gates–MacGinitie Reading Comprehension.

T tests were conducted to compare TSI and Tier 3 students at pretest. Repeated-measures analyses of variance were conducted to compare groups on pretest/posttest gains. The F value represents the Time*Treatment effect.

Effect sizes were calculated by dividing the difference in gain scores by the pooled standard deviation corrected for measurement error (the SD of the gain (McGaw & Glass, 1980).

p < .05.

Research Question 1: Effects of the Intervention

Tier 3 students demonstrated greater gains than TSI students on every reading measure, but this difference was not always statistically significant. Analyses indicated significant time-by-treatment interactions for the WJ III Basic Reading Skills cluster (and for both WJ III Letter–Word Identification and Word Attack individually), the TOWRE composite (and for TOWRE Sight Word Efficiency but not Phonemic Decoding Efficiency), and WJ III Passage Comprehension (see Table 3). There were no significant time-by-treatment interactions on DIBELS ORF or GM Passage Comprehension. Effect sizes for all measures except DIBELS ORF met the benchmark for substantive importance (i.e., exceeded .25; U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2011). Although group differences were not statistically significant, the effect size for TOWRE Phonemic Decoding Efficiency was comparable to that for Sight Word Efficiency (.40 and .39, respectively), and the effect size for the GM comprehension measure was comparable to that for the WJ III comprehension measure (.35 and .34, respectively).

Effects of instructional variables

We evaluated certain instructional variables to determine if they moderated the effects of treatment. Moderators affect the strength of the relation between treatment and outcomes (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Statistically, a significant time by treatment by moderator interaction implies that treatment effects differ at different levels of the moderating variable. As for instructional variables, neither tutor assignment nor attendance at intervention sessions had significant effects on reading gains among Tier 3 students for any of the outcome measures (p > .05). Considering both the Tier 3 and TSI groups, additional intervention status (i.e., whether a student received school-provided intervention outside the research intervention) did not interact with treatment (Tier 3 vs. TSI), nor did it have a main effect on reading gains when treatment was controlled for (based on repeated-measures ANOVA, p > .05). Finally, we evaluated the effects of site on outcomes, finding no interaction with treatment group. When the effects of treatment group were controlled, there was a main effect for site on WJ III Passage Comprehension. Students in the larger site demonstrated greater gains on this measure than students in the smaller site: large site pre/post = 82.6/88.8, small site pre/post = 83.2/86.1, F(1, 68) = 4.16, p < .05.

Research Question 2: Proportions of Students With Adequate Response

To increase sample size for the two-group multivariate analysis of cognitive profiles, we categorized the students as adequate responders if their scores were greater than a standard score of 90 on all three of the following measures: WJ III Basic Reading Skills, WJ III Passage Comprehension, and the TOWRE composite. The cut point of 90 for the WJ III Basic Reading Skills is slightly lower than the threshold used to select the sample, but this threshold equates cut points for all three measures. There were no students who would have qualified for the study at baseline based only on WJ Basic Reading scores of 90–92. In addition, we visually plotted scores of different subgroups on the outcome variables, and they were not obviously different.

Based on the stringent criterion of achieving the benchmark on all three measures, 25.5% of Tier 3 students and 20% of TSI students were adequate responders. The groups did not statistically differ in the proportions of adequate responders, χ2(1) = 0.28, p > .05. We also evaluated the proportions of adequate responders in the two groups based on each measure individually, finding that (a) 72.3% of Tier 3 and 56% of TSI students met the criterion of a standard score of more than 90 for WJ III Basic Reading, not a statistically significant difference, χ2(1) = 1.96, p > .05; (b) 42.6% of Tier 3 and 32% of TSI students met the criterion for the TOWRE composite, also not statistically different, χ2(1) = 0.76, p > .05; and (c) 36.2% of Tier 3 and 36% of TSI students met the criterion for WJ III Passage Comprehension, proportions that did not differ between groups, χ2(1) = 0.00, p > .05.

Research Question 3: Cognitive Attributes of Adequate and Inadequate Responders

We analyzed the scores on KBIT–2 Verbal Knowledge and Matrices; a composite of CTOPP Blending Words and Elision; CTOPP RAN; and CELF–4 CFD and LSP for adequate (n = 17 in Tier 3 and TSI combined) and inadequate (n = 55) responders to Tier 3 intervention based on the combined criterion of a standard score greater than 90 on all three measures (i.e., WJ III Basic Reading Skills, WJ III Passage Comprehension, and the TOWRE composite). Two of the inadequate responders were missing scores for CTOPP RAN. We replaced the missing values with the mean of the inadequate responders group to avoid losing cases with the multivariate approach.

Based on MANOVA, there was a statistically significant effect of responder status on the cognitive variables, F(6, 40) = 3.77, p < .01, η2 = .36. Table 4 shows the means by responder status as well as canonical coefficients.

Table 4.

Group Means and Canonical Coefficients on Cognitive Variables for Adequate and Inadequate Responders to Tier 3 Intervention

| Variable | Adequate responders (n = 12)

|

Inadequate responders (n = 35)

|

Canonicals r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| KBIT–2 Verbal Knowledge | 82.00 | 14.75 | 75.31 | 14.66 | .33 |

| KBIT–2 Matrices | 92.33 | 11.92 | 85.40 | 10.81 | .45 |

| CTOPP Phonological Awareness | 97.71 | 9.01 | 85.79 | 10.83 | .76† |

| CELF–4 Understanding Spoken Paragraphs | 90.83 | 17.30 | 77.14 | 15.96 | .58 |

| CELF–4 Concepts & Following Directions | 84.17 | 14.12 | 71.43 | 12.04 | .68† |

| CTOPP Rapid Naming of Lettersa | 93.56 | 10.70 | 84.16 | 10.75 | .60 |

Note. r = canonical structure correlation; KBIT–2 = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test–2; CTOPP = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; CELF–4 = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–4.

The CTOPP Rapid Naming of Letters (RAN) scores were standardized (M = 100, SD = 15) in a sample of 416 students weighted to reflect population proportions of typical (61%) and struggling (39%) readers (see Denton et al., 2011). The mean RAN items per second were 1.38, 1.05, 1.09, and 0.88 for typical, Tier 2 adequate, Tier 3 adequate, and Tier 3 inadequate responders, respectively.

Univariate p < .008.

Table 4 shows that CTOPP phonological awareness and CELF CFD were the most highly correlated with a linear composite maximally separating the groups. Canonical correlations were smaller for CELF USP and CTOPP RAN, and even smaller for the KBIT Verbal Knowledge and Matrices scores. Because the canonical correlations do not yield statistical significance tests (Huberty & Olejnik, 2006), we conducted follow- up univariate analyses using p < .008 (.05/6) as the critical level of alpha. These analyses yielded statistically significant group differences only for CTOPP phonological awareness and CELF CFD (see Table 4).

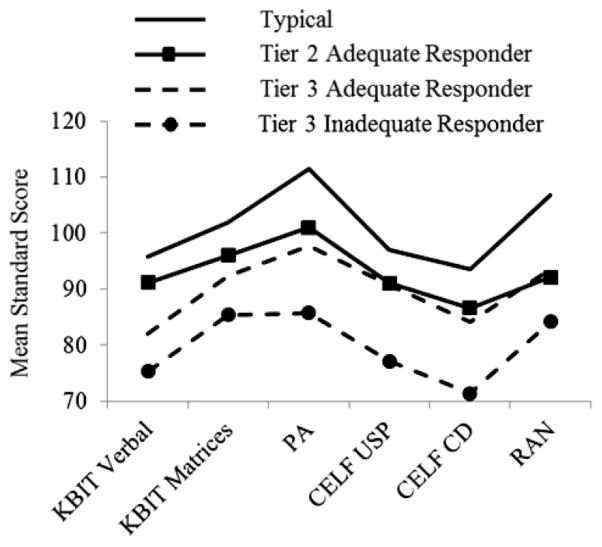

Figure 1 shows the cognitive profiles of Tier 3 adequate and inadequate responders, based on the data analyzed for this study. For descriptive purposes, we standardized the CTOPP RAN against a sample of typically developing children and a weighted sample of poor readers to have M = 100 and SD = 15. We also included the 85 adequate responders to the previous Tier 2 intervention from the Grade 1 study (Denton et al., 2011) and 69 typically developing readers (i.e., not at-risk) who were evaluated following Tier 2. The profiles across the four groups are largely parallel; the differences in levels of performance among the six measures (e.g., the tendency for scores on verbal knowledge to be lower than PA) are apparent for all four groups and reflect differences in the normative samples for the KBIT–2, CTOPP, and CELF-4. Note that except for a tendency for lower scores on KBIT–2 Verbal Knowledge, the profiles for Tier 2 adequate responders and Tier 3 adequate responders are very similar. In addition, the group that showed inadequate response is generally impaired on language skills, especially PA and listening comprehension. Although the inadequate responders have low average scores on KBIT Matrices, they are much lower on KBIT Verbal Knowledge, which along with the results of the descriptive discriminant analysis supports our hypothesis of greater impairment on reading-related and language skills.

Figure 1.

Cognitive profiles of adequate and inadequate responders to Tier 3 intervention in relation to typically developing readers and Tier 2 adequate responders from Denton et al. (2011). KBIT Verbal = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test–2 Verbal Knowledge; KBIT Matricies = Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test–2 Matricies; PA = a composite of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) Blending Words and Elision; CELF USP = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–4 Understanding Spoken Paragraphs; CELF CD = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–4 Concepts and Following Directions; RAN = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing Rapid Naming of Letters. The CTOPP Rapid Naming of Letters scores were standardized (M = 100, SD = 15) in a sample of 416 students weighted to reflect population proportions of typical and struggling readers.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of an intensive, individualized Tier 3 reading intervention for children who had experienced inadequate response to a highly standardized Tier 2 intervention provided in first grade. A second goal was to compare the percentages of students who met post-intervention benchmarks for adequate intervention response. The third purpose was to compare the cognitive profiles of adequate and inadequate responders to Tier 3 intervention on key cognitive variables associated with inadequate response to less intensive intervention.

Research Question 1: Effects of the Intervention

Our hypothesis that students who received the individualized Tier 3 intervention would significantly outperform comparison students who received typical school instruction was partially supported; the intervention was associated with significantly greater gains than typical instruction in word reading, phonemic decoding, word reading fluency, and sentence and paragraph-level reading comprehension. Although the Tier 3 group outperformed the comparison group in phonemic decoding fluency and on a measure of reading comprehension in extended text, these differences were not statistically significant. Effect sizes in all domains except for oral reading fluency were substantively important according to the standards of the What Works Clearinghouse (U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Science, 2011).

The results of this study indicated that an intensive, individualized supplemental reading intervention can be efficacious for students requiring Tier 3 intervention, particularly in remediating word reading and phonemic decoding difficulties and in supporting comprehension of sentences and brief passages. Although many students in the comparison group received alternate school-provided interventions of various types, this intervention was generally not sustained and comprehensive, and students in the Tier 3 research intervention had better outcomes.

Although outcomes were significantly better for the Tier 3 group on several measures, on average, students who received the Tier 3 intervention remained seriously impaired in text reading fluency and passage comprehension at the end of the study, with mean scores below the 20th percentile on DIBELS ORF and WJ III Passage Comprehension and just at the 20th percentile for Gates–MacGinitie Passage Comprehension. According to DIBELS norms, the 20th percentile in the spring of Grade 2 is 68 wcpm (Good, Wallin, Simmons, Kame’enui, & Kaminski, 2002). The Tier III treatment group gained an average of about 33 wcpm from pretest to posttest, but their pretest mean ORF level, about 18 wcpm, was far below expected levels for the beginning of second grade. Their mean second grade posttest score (about 51 wcpm) was similar to the DIBELS ORF 50th percentile for the spring of Grade 1. Given the often-reported high correlations between ORF and reading comprehension in the primary grades (Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, & Jenkins, 2001), the Tier 3 students’ impaired comprehension may be due in part to their limited automaticity of basic skills.

The disappointing outcomes of the treatment group in text reading fluency are consistent with results reported in other studies of remedial interventions with students who have moderate to severe reading difficulties. In a review of research on remedial interventions for students with impaired word reading, Torgesen (2004) reported that even interventions that result in significant improvements in word reading and comprehension for such students commonly have weaker effects on text reading fluency. To explain this consistent finding, Torgesen suggested that students beyond Grade 1 who have reading difficulties have a large practice deficit relative to typically developing readers their age; struggling readers read less and thus have little opportunity to develop automaticity in word recognition, a component of fluent reading. This theory suggests that students in second grade and higher who respond adequately to interventions in terms of improved word reading may need extended text reading practice to reach appropriate levels of automaticity.

Research Question 2: Proportions of Students with Adequate Response

We applied the benchmark of performance above a standard score of 90 (i.e., the 20th percentile) in word reading, word reading efficiency, and passage comprehension to evaluate the proportions of students who demonstrated adequate response to intervention in the Tier 3 and TSI groups. Although a larger percentage of Tier 3 than TSI students attained the benchmarks for word reading and word reading fluency, the proportions did not differ significantly between the groups.

As has been reported in previous studies of Tier 3 interventions (e.g., Denton et al., 2006), the responsiveness of individual students was highly variable. At posttest, the majority of Tier 3 students (72%) performed within the average range in word reading and phonemic decoding (i.e., basic reading skills); however, fewer than half met the posttest benchmarks for word reading fluency (43%) and passage comprehension (36%) at the end of the study. Students with reading difficulties that are resistant to remediation may require a longer term intervention than we provided in this study to achieve performance in the average range. Alternately, students may have responded more positively to intervention that devoted more time to explicit instruction in comprehension strategies. Future research should investigate more directly the optimal balance between instruction in word-level and text-level skills for students with severe and intractable difficulties in multiple reading domains.

Research Question 3: Cognitive Attributes of Adequate and Inadequate Responders

The descriptive discriminant analysis showed that measures of phonological awareness and listening comprehension were most closely associated with responder status. However, as Figure 1 shows, students who responded inadequately to Tier 3 intervention were generally more impaired on all language measures. Moreover, in comparison with adequate responders to Tier 2 intervention, the profiles of the Tier 3 responders were similar, differing slightly in elevation. In contrast, inadequate responders to both Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention showed more severe and pervasive language impairments. Because these language impairments were apparent before even Tier 2 intervention, these results imply that persistent language impairment, especially after Tier 2 intervention, may indicate elevated risk for a persistently inadequate intervention response. Although our sample size is not adequate to attempt individual predictions of response, the results are consistent with prior studies of the cognitive attributes of Tier 2 adequate and inadequate responders, suggesting a continuum of severity corresponding with the level of reading ability at baseline. These results show little evidence of qualitative differences that might suggest differences in the type of intervention or alternative approaches to intervention other than a more intense focus on oral language development.

Limitations and Implications of the Study

This study was primarily limited by the relatively small number of participants. Conducting research examining Tier 3 intervention is challenging, in that ensuring an adequate sample size at Tier 3 necessitates beginning with a very large sample in the lower tiers. Because of our relatively small sample, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution.

Despite this limitation, this study has implications for theory and practice. The pattern of results, indicating stronger outcomes for word-level reading skills than for oral passage reading fluency and reading comprehension, are consistent with developmental models of reading acquisition (Chall, 1983; Ehri, 2005). In such models, reading acquisition is described as essentially a “bottom-up” process in which children master word identification at increasingly complex levels, and then, through practice, begin to execute these skills with increasing efficiency. Under this theoretical framework, it would be expected that students with impaired word reading would need to attain a level of proficiency in foundational sub-skills before they are able to orchestrate these skills to support fluent reading.

From such a developmental perspective, it might be expected that reading comprehension would develop in tandem with, or after, fluency. The fact that outcomes in this study were stronger for comprehension than for fluency is not totally aligned with this expectation. Perfetti, Landi, and Oakhill (2005) described a more interactive model of reading comprehension, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between the development of reading comprehension and word reading. In this model, “Children must come to readily identify words and encode their relevant meaning into the mental representation that they are constructing” (p. 229), but the development of word identification—conceptualized as the acquisition of high-quality representations of the’ phonology, orthography, and meanings of words—is supported when children read with comprehension. Thus, children may progress in word reading and comprehension while lagging behind in fluency. Moreover, although there is a strong positive correlation between fluency and comprehension in the primary grades (Fuchs et al., 2001), research has not informed the field of the threshold of fluency required for adequate comprehension of text at different stages of reading acquisition, especially for children with reading difficulties. In such students, the finding that fluency outcomes are weaker than word reading and comprehension outcomes is common (Torgesen, 2004).