Abstract

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) are a class of small-molecule chemical compounds that bind to estrogen receptor (ER) ligand binding domain (LBD) with high affinity and selectively modulate ER transcriptional activity in a cell- and tissue-dependent manner. The prototype of SERMs is tamoxifen, which has agonist activity in bone, but has antagonist activity in breast. Tamoxifen can reduce the risk of breast cancer and, at same time, prevent osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen is widely prescribed for treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Mechanistically the activity of SERMs is determined by the selective recruitment of coactivators and corepressors in different cell types and tissues. Therefore, understanding the coregulator function is the key to understanding the tissue selective activity of SERMs.

Keywords: SERM, Nuclear receptor, Coregulator

Introduction

The pleiotropic effects of estrogens are mediated by their two cognate nuclear receptors, Estrogen Receptor alpha and beta (ERα and ERβ), which are members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily[1]. Estrogens are essential for the maintenance of normal functions of the female reproductive tissues and non-reproductive tissues including metabolic homeostasis, skeletal homeostasis, the cardiovascular system, and central nervous system (CNS) [2, 3]. Diminished estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are associated with dysfunctions in those tissues. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT; estrogen plus progestin) is effective in relieving the symptoms associated with menopause but is associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer. Replacement with pure estrogen is associated with increased risk of uterine cancers [4, 5]. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) can selectively activate or inhibit ER transcriptional activity in different tissues, and therefore retain beneficial effects while reducing harmful effects [6]. SERMs have been widely used for treatment of ER-positive breast cancer which occurs in 70% of breast cancer cases. The most commonly used SERMs in clinic is tamoxifen, and it has been used clinically for more than 30 years as a front-line treatment for the ERα-positive breast tumors at all stages[7]. Other second generation SERMs that have decreased stimulatory effects on the uterus are now available.

Structure and function of estrogen receptors

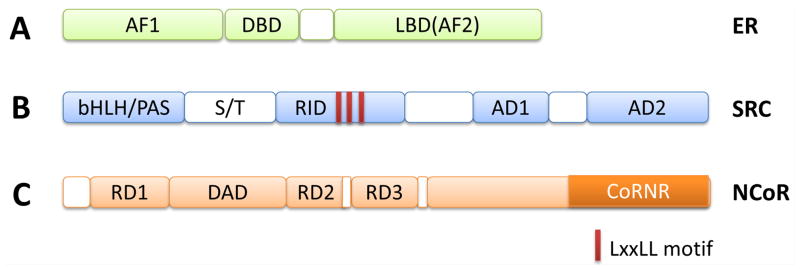

Estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ contain three major functional domains including an amino-terminal Activation Function-1 (AF-1) domain, a central DNA-binding domain (DBD), and a carboxyl-terminal Ligand binding domain (LBD) (Figure 1A). The variable NH2-terminal AF-1 domains of ERs are not conserved among the nuclear receptor superfamily. The AF-1 domain is intrinsically unstructured in solution and forms secondary structure when engaged in interaction with coregulators. The transcriptional activity of AF-1 is controlled by phosphorylation through the MAPK pathway [8, 9] and is hormone-independent. The centrally located DBD is the most conserved region and is a signature domain of nuclear receptors. The DBD is composed of two C4-type zinc fingers and recognizes specific DNA sequences in enhancer or promoter regions of target genes, known as hormone response elements (HREs). The carboxyl-terminal LBD contains 12 alpha helices (H1 to H12) which form alpha helical sandwich conformation [10]. The hydrophobic ligand binding cavity is within the interior of the LBD and binds estrogen with high specificity and affinity. Hormone binding subsequently induces a conformational change and creates a novel interacting surface for coregulators. The primary sequence of LBDs is moderately conserved among nuclear receptors.

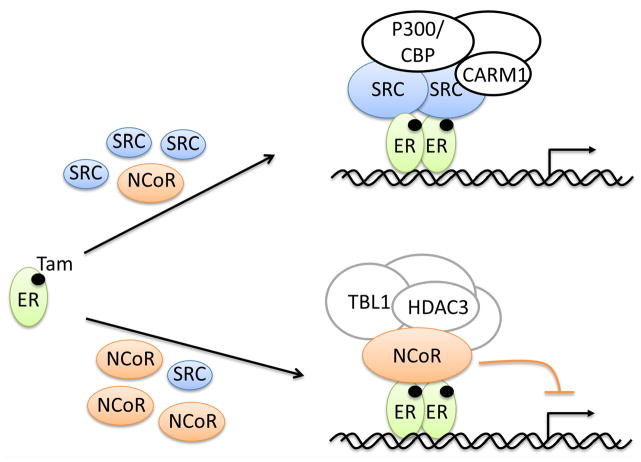

Figure 1.

Domain structure of ER, SRC coactivators and NCoR corepressors. (A) ER is composed of NH2-terminal AF1, DBD (DNA binding domain), and carboxyl-terminal LBD (Ligand binding domain). There is a hinge region between DBD and LBD. (B) SRC coactivators contain several major domains, including bHLH/PAS, RID that contains three LxxLL motifs, AD1 that interacts with p300/CBP, and AD2 that interacts with CARM1. (C) NCoR coreporessors, NCoR1 and NCoR2(SMRT), contain several repression domains including RD1, RD2, RD3 and DAD (Deacetylase activating domain) that interact with HDACs, and CoRNR (nuclear receptor interacting domain in corepressors) domain that interacts with nuclear receptor.

ERα mainly functions as a transcription factor in the nucleus. Hormone-bound ER protein binds to estrogen response elements (EREs) located on enhancer/promoter regions of target genes, and directly regulates gene expression in response to estrogens. ERα protein itself does not possess intrinsic enzymatic activity. Instead ERα recruits coregulators that contain diverse enzymatic activities, including histone acetyltransferase (HAT), histone methyltransferase (HMT), kinase, etc. These coregulators have no DBD and cannot bind directly to genomic DNA. They are targeted to specific genomic sites by interactions with DNA-bound ER protein. Once enriched at the specific genomic regions, the coregulators can covalently modify histones and DNA, and subsequently alter chromatin structure to facilitate or suppress the transcription of target genes. Thus, the transcriptional activity of ER is essentially carried out by coregulators. More than 450 coregulators have been reported for nuclear hormone receptors in the literature, and many of them contain a variety of different enzymatic activities.

The SRC family of transcriptional coactivators are “primary” ER coactivators

The SRC/p160 family of coactivators are the best characterized coactivators for steroid hormone receptors including ER. This family consists of three members. Steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) is the first bona fide nuclear receptor coactivator, cloned in 1995 as an interacting partner for the progesterone receptor LBD through a yeast two-hybrid screening [11]. The subsequent identification and characterization of SRC-2 (GRIP1, TIF2) and SRC-3 (p/CIP, RAC3, ACTR, AIB1, and TRAM-1) has established the SRC/p160 family of coactivators [12]. Although SRCs are named as coactivators for steroid hormone receptors, it is clear that they also function as coactivators for non-steroid groups of nuclear receptors, such as thyroid hormone receptors, retinoid receptors, vitamin D3 receptor, and many non-nuclear receptor transcription factors as well, such as E2F1 [13], Ets-2 [14] and NF-κB [15].

The three SRC family members are highly homologous and share an overall similarity of 50–55% in their primary sequences [16]. SRC coactivators contain several functional domains, including a NH2-terminal basic helix-loop-helix-Per/Ah receptor nuclear translocation/Sim (bHLH/PAS) domain, a receptor interacting domain (RID), and carboxyl-terminal Activation Domains 1 (AD1) and 2 (AD2) (Figure 1B). The RID contains three amphipathic leu-x-x-leu-leu (LxxLL) motifs [17] and is responsible for direct interaction with agonist-bound receptor LBD [18]. Upon estrogen binding, the carboxyl-terminal alpha helix 12 of ER folds back toward the ER LBD and, together with helix 3 and 5, forms a hydrophobic cleft, which interacts with the hydrophobic surface of LxxLL motifs of SRCs. Because they are directly recruited by hormone-bound ER, SRC coactivators are considered as primary coactivators. Subsequently SRCs serve as bridging molecules to bring in secondary coactivators through AD1 and AD2, including p300/CBP [19] and CARM1 [20]. P300 and CBP are potent histone acetyltransferases, whereas CARM1 is a histone methyltransferase. The AD1 of SRCs physically associates with p300/CBP and shows potent transcriptional activity in reporter gene assay when tethered to a heterologous DNA binding domain such as GAL4 DBD[21]. AD2 binds to CARM1 and shows relatively weaker transcriptional activity when tethered to GAL4 DBD [21]. Interestingly SRC-1 and SRC-3 also possess intrinsic acetyltransferase activity toward histones [19, 22]. However their HAT activity is weak, suggesting that their cognate substrates might not be histones.

In addition to conventional reporter gene assays, recruitment of SRC coactivators by ER to its target genes is strongly supported by state-of-the-art genome-wide chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis. In MCF7 breast cancer cells, mapping of the chromatin binding sites of the three members of SRCs revealed that the genomic recruitment of SRC proteins clearly followed ERα ligand stimulation, indicating that SRC recruitment by ER indeed occurs in real time in cells [23]. However the targeting genes regulated by SRC-3 are not shared with the other two SRC family members. This is in agreement with other studies showing that each SRC protein regulates a unique set of genes in MCF7 cells, suggesting that they play non-redundant roles in breast cancer development [24].

There also is ample biochemical evidence showing that SRC coactivators are bona fide coactivators for ER. In Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry analyses, purification of E2-bound ER-associated protein complexes revealed that all there SRC members interact with ER in a hormone-dependent manner [25]. Similarly, purification of SRC3-associated protein complexes confirms that CBP/p300 form a complex with SRC3 [25]. In chromatin-based in vitro transcription assays, SRCs and CBP/p300 significantly enhance ER-mediated transcription [26]. Our recent Cryo-EM study reveals that two SRC-3 molecules simultaneously interact with an ERα dimer on DNA and form an asymmetric protein surface, providing a structural basis for further recruitment of a large number of secondary coactivators (unpublished).

The in vivo biological roles of SRC coactivators in female reproductive functions in animal have been well documented. For instance, SRC-1 null mice show partial resistance to steroid hormones [27]. SRC-2 is essential for progesterone-dependent uterine function and mammary gland morphogenesis in mouse models [28]. SRC-3 is required for female reproductive function and mammary gland development [29]. Finally it is worthy to note that SRC-3/AIB1 is a bona fide oncogene in breast cancer. The SRC3 gene is amplified in ~10% of breast tumor samples [30] and SRC3 mRNA is overexpressed in the majority of primary breast cancers. Forced overexpression of SRC-3 in mammary gland caused mammary tumor development [31]. Collectively, these molecular, cellular, biochemical, and animal data have unequivocally established that SRC proteins are bona fide coactivators for nuclear receptors and are key components of the estrogen/ER signaling pathway.

The NCoR1/SMRT corepressor family

In contrast to coactivators, there are a group of transcriptional factors, termed corepressors, which oppose the action of coactivators in nuclear receptor-mediated transcriptional regulation; the existence of coactivators and corepressors suggests a yin-yang relationship for regulation of gene transcription. NCoR1 (nuclear receptor corepressor 1) and SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) are prototypical nuclear receptor corepressors. NCoR1 and SMRT were initially cloned as hormone-independent TR or RXR interacting proteins in yeast two-hybrid screening [32, 33]. NCoR1 and SMRT interact with nuclear receptors in the absence of hormone and their interaction is disrupted by agonist binding. NCoR1 and SMRT contain a receptor interacting domain (RID) and repression domains (RDs) (Figure 1C). The RID contains a L/I-x-x-I/V-I motif (CORNR motif) to interact with nuclear receptors [34–36], reminiscent of the L-x-x-L-L motif (also known as NR box) of coactivators. Importantly NCoR1 and SMRT do not have intrinsic enzymatic activity. Instead NCoR1 and SMRT function as scaffold proteins, and they recruit histone deacetylases including HDAC3 through several repression domains (RD1, RD2 and RD3) [37, 38]. In the absence of hormone, nuclear receptors TR, RAR and RXR bind to enhancers of target genes, and recruit NCoR1 and/or SMRT and associated HDACs to remove histone acetylation marks that suppress gene transcription. When receptors bind an agonistic ligand, the corepressors NCoR1/SMRT and their associated HDACs are dissociated, and SRC coactivators in turn are loaded to the agonist-bound receptors to stimulate gene transcription [39].

It is important to note that although NCoR1 and SMRT were initially identified as corepressors for non-steroid nuclear receptors, later studies have clearly established that NCoR1/SMRT can also function as corepressors for steroid receptors and suppress their target gene transcription [40–43]. For example, NCoR1 is recruited to the pS2 gene promoter by ER in the absence of hormone, and tamoxifen treatment enhances NCoR recruitment [44]. NCoR1 and SMRT can also function as corepressors for many non-nuclear receptor transcriptional factors [45].

Determination of SERM activity by coactivators and corepressors

The unique feature of a SERM is its cell- and tissue-selective activity. The first implication that relative expression of coactivator and corepressors in cells contribute to SERM function is based on transient transfection luciferase reporter assays. In this study, overexpression of SRC-1 enhanced 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT)-stimulated ER activity, whereas overexpression of SMRT strongly suppressed 4HT-stimulated ER activity [40]. When SRC-1 and SMRT were co-overexpressed, SMRT blocked the SRC-1 coactivation of 4HT-depependent ER activity [40]. For the first time, these results suggested that the relative expression of SRC-1 and SMRT can modulate the 4HT-dependent ER activity.

This observation is further supported by a study showing that tamoxifen is antiestrogenic in breast cells but estrogenic in endometrial cells. It was found that a high expression level of SRC-1 in endometrial carcinoma cell lines is responsible for induction of c-Myc and IGF-1 by tamoxifen-stimulated ER. Growth stimulatory effects of tamoxifen in uterine cells were abolished by depletion of SRC-1 by siRNA, indicating the SRC-1 levels are critical for agonist activity of tamoxifen in the endometrium [46].

In an in vitro model, up-regulated SRC-3 coactivator expression is associated with acquired tamoxifen resistance in MCF-7 cells cultured in tamoxifen-containing media [47]. Importantly in breast cancer patients, high SRC-3 level also correlates with tamoxifen resistance [48]. In cultured breast cancer cells, overexpression of SRC-3 and Her2 is able to convert tamoxifen from an antagonist into an ER agonist, resulting in de novo resistance [49]. Under this condition, tamoxifen treatment causes recruitment of coactivator complexes (SRC-3 and p300/CBP) to, and dissociation of corepressor complexes (NCoR/HDAC3) from, the ER-regulated pS2 gene promoter. In agreement with this, depletion of SRC-3 expression by siRNA restored the inhibitory effect of tamoxifen on cell proliferation in breast cancer BT474 cells [50]. PKA-induced tamoxifen resistance is associated with increased recruitment of SRC-1 by phosphorylation of S305 [51].

On the other hand, in breast cancer cells, corepressor NCoR1 and SMRT are required for the antagonistic effects of tamoxifen. They prevent tamoxifen from stimulating proliferation through suppression of a subset of ERα target genes involved in cell proliferation. Silencing of NCoR1 and SMRT promoted tamoxifen-induced cell cycle progression and proliferation [52]. In a breast cancer mouse model, reduced expression levels of NCoR1 correlate with the development of tamoxifen resistance [53]. In a cohort of ERα-positive unilateral invasive primary breast tumors from 99 postmenopausal patients who only received tamoxifen as adjuvant hormone therapy after primary surgery, low NCoR1 expression was associated with a significantly shorter relapse-free survival [54], substantiating a role of corepressor NCoR1 in tamoxifen resistance. In further support of this notion, based on ChIP analysis, over-expression of coactivator SRC-1 or corepressor SMRT is sufficient to alter the transcriptional action of tamoxifen on a number of target genes in breast and endometrial cancer cells [55].

Recent data reveal another mechanism of tamoxifen resistance caused by increased SRC-3 level. It is shown that the paired box 2 gene product (PAX2) is a tamoxifen-recruited transcriptional repressor of the ERBB2 gene. Increased SRC-3 can compete with PAX2 for ERRB2 gene binding and result in overexpression of ERRB2 and cause subsequent tamoxifen-resistant cell growth [56].

The importance of coregulators in determination of tamoxifen activity is also true for other SERMs. For instance, raloxifene promotes ERα interaction with NCoR1 both in vivo and in vitro [42]. In rat uterus, ormeloxifene antagonizes in vivo ERα activity by increasing the recruitment of NCoR1 corepressor and reducing the recruitment of SRC-1 coactivator [57]. In addition to SRCs, other coactivators can also play a role in SERM activity. For example, recruitment of Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC)-1β with ER LBD induced by tamoxifen contributes to the agonistic activity of tamoxifen in cultured cells [58].

SERMs regulate coregulator expression level and activities

Coregulators determine the SERM activity. On the other hand, SERMs can regulate the expression levels of coregulators, forming a feedback regulatory loop. For instance, in cultured cells, 4-hydroxytamoxifen and raloxifene increased protein stability and function of SRC-1 and SRC-3 coactivators in an ERα-dependent manner [59]. The increased coactivators subsequently enhance the transcriptional activity of other nuclear receptors, suggesting that these SERMS have broad biological actions in the cells [59]. In human patients, tamoxifen therapy leads to significantly increased expression of coactivators, particularly SRC-3, in both normal and malignant breast tissues [60]. In human skeletal muscle cells, tamoxifen and raloxifene increase SRC-1 mRNA levels while decreasing SMRT mRNA levels [61].

SERMs not only impact coactivator protein stability, but also can regulate the coactivator activity though posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation. In response to anti-estrogen treatment, multiple growth signaling pathways are up-regulated (HER2, PI3K, PKC, etc). Activated kinases phosphorylate SRC-3, enhance its coactivator activity, affect cell growth, and eventually contribute to resistance [62, 63].

Summary

Since the cloning of the first nuclear receptor coactivator SRC-1 in 1995 [11], the last two decades have seen explosive growth of the coregulator field, with total numbers of about 450 coregulators characterized to date. Numerous studies have established that coregulators play pleiotropic roles in animal pathophysiology. In this review, we focused on the critical role of coregulators in SERM function since the literature reveals growing evidence to support that SERM activity is mainly determined by the selective recruitment of coactivators and corepressors to ER target gene in specific types of cells and tissues (Figure 2). Better understanding of coactivator and corepressor functions should enhance future development of new generations of SERMs which have more beneficial and less harmful effects.

Figure 2.

The selective recruitment of coactivators and corepressors determines the SERM activity. Shown in the diagram is one representative mechanism in which the relative abundance of SRCs and NCoRs governs the recruitment. Other mechanisms could also influence recruitment, such as increased SRC recruitment by PKA-induced phosphorylation (See text for details).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annual review of biochemistry. 1994;63:451–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Della Torre S, Benedusi V, Fontana R, Maggi A. Energy metabolism and fertility--a balance preserved for female health. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2014;10:13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maggi A, Ciana P, Belcredito S, Vegeto E. Estrogens in the nervous system: mechanisms and nonreproductive functions. Annual review of physiology. 2004;66:291–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.154945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108, 411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:1047–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beral V. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362:419–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan VC. Selective estrogen receptor modulation: a personal perspective. Cancer research. 2001;61:5683–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: a most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2003;2:205–13. doi: 10.1038/nrd1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato S, Endoh H, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T, Uchiyama S, Sasaki H, et al. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1995;270:1491–4. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajbhandari P, Finn G, Solodin NM, Singarapu KK, Sahu SC, Markley JL, et al. Regulation of estrogen receptor alpha N-terminus conformation and function by peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:445–57. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06073-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, et al. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–8. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–7. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson AB, O’Malley BW. Steroid receptor coactivators 1, 2, and 3: critical regulators of nuclear receptor activity and steroid receptor modulator (SRM)-based cancer therapy. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;348:430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie MC, Zou JX, Rabinovich A, Chen HW. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:5157–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-azawi D, Ilroy MM, Kelly G, Redmond AM, Bane FT, Cocchiglia S, et al. Ets-2 and p160 proteins collaborate to regulate c-Myc in endocrine resistant breast cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:3021–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Na SY, Lee SK, Han SJ, Choi HS, Im SY, Lee JW. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 interacts with the p50 subunit and coactivates nuclear factor kappaB-mediated transactivations. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:10831–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Wu RC, O’Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nature reviews Cancer. 2009;9:615–30. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker MG. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–6. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, et al. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, et al. Nuclear receptor coactivator ACTR is a novel histone acetyltransferase and forms a multimeric activation complex with P/CAF and CBP/p300. Cell. 1997;90:569–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang SM, Schurter BT, et al. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voegel JJ, Heine MJ, Tini M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. The coactivator TIF2 contains three nuclear receptor-binding motifs and mediates transactivation through CBP binding-dependent and -independent pathways. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:507–19. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer TE, Jenster G, Burcin MM, Allis CD, Zhou J, Mizzen CA, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature. 1997;389:194–8. doi: 10.1038/38304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwart W, Theodorou V, Kok M, Canisius S, Linn S, Carroll JS. Oestrogen receptor-co-factor-chromatin specificity in the transcriptional regulation of breast cancer. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:4764–76. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karmakar S, Foster EA, Smith CL. Unique roles of p160 coactivators for regulation of breast cancer cell proliferation and estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional activity. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1588–96. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malovannaya A, Lanz RB, Jung SY, Bulynko Y, Le NT, Chan DW, et al. Analysis of the human endogenous coregulator complexome. Cell. 2011;145:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulds CE, Feng Q, Ding C, Bailey S, Hunsaker TL, Malovannaya A, et al. Proteomic analysis of coregulators bound to ERalpha on DNA and nucleosomes reveals coregulator dynamics. Molecular cell. 2013;51:185–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Qiu Y, DeMayo FJ, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Partial hormone resistance in mice with disruption of the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) gene. Science. 1998;279:1922–5. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee A, Soyal SM, Fernandez-Valdivia R, Gehin M, Chambon P, Demayo FJ, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator 2 is critical for progesterone-dependent uterine function and mammary morphogenesis in the mouse. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:6571–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00654-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Liao L, Ning G, Yoshida-Komiya H, Deng C, O’Malley BW. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:6379–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120166297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, et al. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–8. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres-Arzayus MI, Font de Mora J, Yuan J, Vazquez F, Bronson R, Rue M, et al. High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer cell. 2004;6:263–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377:454–7. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, Kurokawa R, et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377:397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu X, Lazar MA. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1999;402:93–6. doi: 10.1038/47069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perissi V, Staszewski LM, McInerney EM, Kurokawa R, Krones A, Rose DW, et al. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes & development. 1999;13:3198–208. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy L, Kao HY, Love JD, Li C, Banayo E, Gooch JT, et al. Mechanism of corepressor binding and release from nuclear hormone receptors. Genes & development. 1999;13:3209–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guenther MG, Lane WS, Fischle W, Verdin E, Lazar MA, Shiekhattar R. A core SMRT corepressor complex containing HDAC3 and TBL1, a WD40-repeat protein linked to deafness. Genes & development. 2000;14:1048–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagy L, Kao HY, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, et al. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89:373–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen YD, Perissi V, Staszewski LM, Yang WM, Krones A, Glass CK, et al. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor corepressors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:7202–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith CL, Nawaz Z, O’Malley BW. Coactivator and corepressor regulation of the agonist/antagonist activity of the mixed antiestrogen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:657–66. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson TA, Richer JK, Bain DL, Takimoto GS, Tung L, Horwitz KB. The partial agonist activity of antagonist-occupied steroid receptors is controlled by a novel hinge domain-binding coactivator L7/SPA and the corepressors N-CoR or SMRT. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:693–705. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb P, Nguyen P, Kushner PJ. Differential SERM effects on corepressor binding dictate ERalpha activity in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:6912–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto Y, Wada O, Suzawa M, Yogiashi Y, Yano T, Kato S, et al. The tamoxifen-responsive estrogen receptor alpha mutant D351Y shows reduced tamoxifen-dependent interaction with corepressor complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:42684–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang S, Meyer R, Kang K, Osborne CK, Wong J, Oesterreich S. Scaffold attachment factor SAFB1 suppresses estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transcription in part via interaction with nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:311–20. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen TA, Hoivik D, Lee JE, Safe S. Interactions of nuclear receptor coactivator/corepressor proteins with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1999;367:250–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shang Y, Brown M. Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs. Science. 2002;295:2465–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1068537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott DJ, Parkes AT, Ponchel F, Cummings M, Poola I, Speirs V. Changes in expression of steroid receptors, their downstream target genes and their associated co-regulators during the sequential acquisition of tamoxifen resistance in vitro. International journal of oncology. 2007;31:557–65. doi: 10.3892/ijo.31.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, Chamness GC, Hilsenbeck SG, Fuqua SA, et al. Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:353–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Wakeling AE, Ali S, Weiss H, et al. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:926–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su Q, Hu S, Gao H, Ma R, Yang Q, Pan Z, et al. Role of AIB1 for tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Oncology. 2008;75:159–68. doi: 10.1159/000159267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zwart W, Griekspoor A, Berno V, Lakeman K, Jalink K, Mancini M, et al. PKA-induced resistance to tamoxifen is associated with an altered orientation of ERalpha towards co-activator SRC-1. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:3534–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keeton EK, Brown M. Cell cycle progression stimulated by tamoxifen-bound estrogen receptor-alpha and promoter-specific effects in breast cancer cells deficient in N-CoR and SMRT. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1543–54. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavinsky RM, Jepsen K, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Mullen TM, Schiff R, et al. Diverse signaling pathways modulate nuclear receptor recruitment of N-CoR and SMRT complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:2920–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Girault I, Lerebours F, Amarir S, Tozlu S, Tubiana-Hulin M, Lidereau R, et al. Expression analysis of estrogen receptor alpha coregulators in breast carcinoma: evidence that NCOR1 expression is predictive of the response to tamoxifen. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:1259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romano A, Adriaens M, Kuenen S, Delvoux B, Dunselman G, Evelo C, et al. Identification of novel ER-alpha target genes in breast cancer cells: gene- and cell-selective co-regulator recruitment at target promoters determines the response to 17beta-estradiol and tamoxifen. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2010;314:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Geistlinger TR, Hutcheson IR, Nicholson RI, Brown M, et al. Regulation of ERBB2 by oestrogen receptor-PAX2 determines response to tamoxifen. Nature. 2008;456:663–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daverey A, Saxena R, Tewari S, Goel SK, Dwivedi A. Expression of estrogen receptor co-regulators SRC-1, RIP140 and NCoR and their interaction with estrogen receptor in rat uterus, under the influence of ormeloxifene. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2009;116:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kressler D, Hock MB, Kralli A. Coactivators PGC-1beta and SRC-1 interact functionally to promote the agonist activity of the selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:26897–907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lonard DM, Tsai SY, O’Malley BW. Selective estrogen receptor modulators 4-hydroxytamoxifen and raloxifene impact the stability and function of SRC-1 and SRC-3 coactivator proteins. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:14–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.14-24.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haugan Moi LL, Hauglid Flageng M, Gandini S, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, Bonanni B, Lazzeroni M, et al. Effect of low-dose tamoxifen on steroid receptor coactivator 3/amplified in breast cancer 1 in normal and malignant human breast tissue. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2176–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dieli-Conwright CM, Spektor TM, Rice JC, Todd Schroeder E. Oestradiol and SERM treatments influence oestrogen receptor coregulator gene expression in human skeletal muscle cells. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;197:187–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu RC, Qin J, Yi P, Wong J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, et al. Selective phosphorylations of the SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator integrate genomic reponses to multiple cellular signaling pathways. Molecular cell. 2004;15:937–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yi P, Wu RC, Sandquist J, Wong J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, et al. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase 1 (Pin1) serves as a coactivator of steroid receptor by regulating the activity of phosphorylated steroid receptor coactivator 3 (SRC-3/AIB1) Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:9687–99. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9687-9699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]