Abstract

NPM1 mutations represent frequent genetic alterations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) associated with a favorable prognosis. Different types of NPM1 mutations have been described. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the relevance of different NPM1 mutation types with regard to clinical outcome. Our analyses were based on 349 NPM1-mutated AML patients treated in the AMLCG99 trial. Complete remission rates, overall survival and relapse-free survival were not significantly different between patients with NPM1 type A or rare type mutations. The NPM1 mutation type does not seem to play a role in risk stratification of cytogenetically normal AML.

Introduction

The gene encoding nucleophosmin (NPM1), a nucleo-cytoplasmatic shuttling protein with prominent nucleolar localization is located on 5q35.1 and contains 12 exons. NPM1 is involved in epigenetic control (binding of nucleic acids, centrosome duplication), ribosomal protein assembly as molecular chaperon and regulation of the ARF-p53-tumor suppressor pathway [1], [2].

NPM1 mutations can be found in 35% of patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (AML). They are associated with a favorable prognosis in the absence of an additional internal tandem duplication in the fms-related tyrosine 3 gene (FLT3-ITD), female gender, high white blood count (WBC), high amount of bone marrow blasts as well as a high platelet count [1].

In the vast majority of cases NPM1 mutations result in a frameshift due to an insertion of four bases, which cluster in exon 12. Different types of NPM1 mutations have been described according to the inserted tetranucleotide, the most common being type A mutations (TCTG) in 80%, followed by type B (CATG) and type D (CCTG) mutations in about 10%, and a spectrum of other mutations accounting for 10% of cases. In rare cases, insertions from 2 to 9 bases can occur (e.g. types E, F) [1].

The altered NPM1 protein (NPM1c+) contains an additional C terminal nuclear export signal (NES) motif and loses at least one tryptophan residue, causing an aberrant cytoplasmatic localization of the protein [3].

Little is known about the prognostic relevance of the variable NPM1 mutation types. In FLT3-ITD negative patients, a Korean study found an adverse impact on overall survival (OS) and duration of complete remission (CR) in NPM1 mutations other than type A [4]. In FLT3-ITD positive patients, another recent study reported an adverse OS in NPM1 type A mutations [5] whereas - in contrast to Koh et al. - they did not observe an effect of NPM1 mutation type in FLT3-ITD negative patients.

We aimed at studying the clinical relevance of NPM1 mutation types on prognosis in a large homogeneously treated cohort of cytogenetically normal AML patients.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Our analyses were based on a total of 783 patients with newly diagnosed cytogenetically normal AML treated within the randomized multicenter German AML Cooperative Group 99 (AMLCG99) trial comparing a double induction therapy with thioguanine, cytarabine and daunorubicin (TAD) and high dose mitoxantrone (HAM) versus HAM-HAM [6].

The AMLCG99 trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00266136) and was approved by the local institutional review boards of all participating centers. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cytogenetic and molecular analyses

All cytogenetic and molecular analyses were performed on bone marrow aspirates. Cytogenetic analyses were based on the assessment of at least 20 metaphases and performed according to the international system of cytogenetic nomenclature (ISCN) guidelines [7]. Mutations of NPM1 [1], FLT3-ITD [8], the FLT3-ITD mRNA level [9], [10], CEBPA [11], [12], were analyzed as previously described. The nomenclature of the NPM1 mutation type was performed according to the literature [1], [13], [14]. NPM1 mutations other than type A mutations were grouped together as rare type mutations (NPM1-rare), NPM1 mutations other than type A, B or D were grouped together as other mutations (NPM1-other).

Outcome Parameters

OS was calculated from the date of randomization until death from any cause. Surviving patients were censored at the date of last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was determined for responders from the first day of CR until relapse or death from any cause. Patients in CR that did not experience a relapse were censored at the last disease assessment.

For patients who had undergone allogeneic transplantation according to the study protocol, OS and RFS times were censored at the time of transplantation.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous characteristics between patient groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for 2 groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test for 3 groups. The  2-test for was applied for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier estimation for OS and RFS was performed comparing NPM1-mutated patients with a type A mutation (NPM1-A) versus NPM1-mutated patients with another type of NPM1 mutation (rare type: NPM1-RA) as well as both groups combined with either FLT3-ITD or without FLT3-ITD. In a second analysis, patients with NPM1 mutations types A, B and D were analyzed independently and compared to patients carrying other mutations than A, B and D who were grouped together as “NPM1- other”.

2-test for was applied for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier estimation for OS and RFS was performed comparing NPM1-mutated patients with a type A mutation (NPM1-A) versus NPM1-mutated patients with another type of NPM1 mutation (rare type: NPM1-RA) as well as both groups combined with either FLT3-ITD or without FLT3-ITD. In a second analysis, patients with NPM1 mutations types A, B and D were analyzed independently and compared to patients carrying other mutations than A, B and D who were grouped together as “NPM1- other”.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals between the different groups were estimated by Cox regression analyses.

Independent prognostic parameters for OS and RFS were identified by univariable Cox regression analyses and a multivariable Cox regression model using backward elimination with an exclusion significance level of 5%. For all analyses, a p-value<0.05 was considered significant. For the estimation of the median follow-up time, the reversed Kaplan-Meier method was applied [15].

Results

Patient characteristics

Analyses were performed in 349 NPM1-mutated patients of 667 patients with CN-AML treated within the AMLCG99 trial, after exclusion of 106 patients without information of the NPM1 mutation status. For an overview of patient selection, please refer to Figure S1 in File S1.

Out of 349 patients, 16% underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first CR. Median follow-up for OS was 45.3 months. Median OS was 45.6 months with 151 events. In 74% of patients who achieved a CR, median RFS was 37.1 months with 115 events.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table S1 in File S1. The selected 677 patients from whom the 349 NPM1-mutated patients were analyzed displayed similar patient characteristics and outcome (OS and RFS, not significantly different) as the unselected patients.

The majority of patients (77%) carried NPM1 type A mutations, followed by 9% with NPM1 type D, 5% with NPM1 type B mutations and 2% with NPM1 type I mutations. All other mutations occurred in ≤1% of patients (Table S2 in File S1).

NPM1 mutation type does not influence outcome

A) NPM1 mutation type A versus rare type mutations

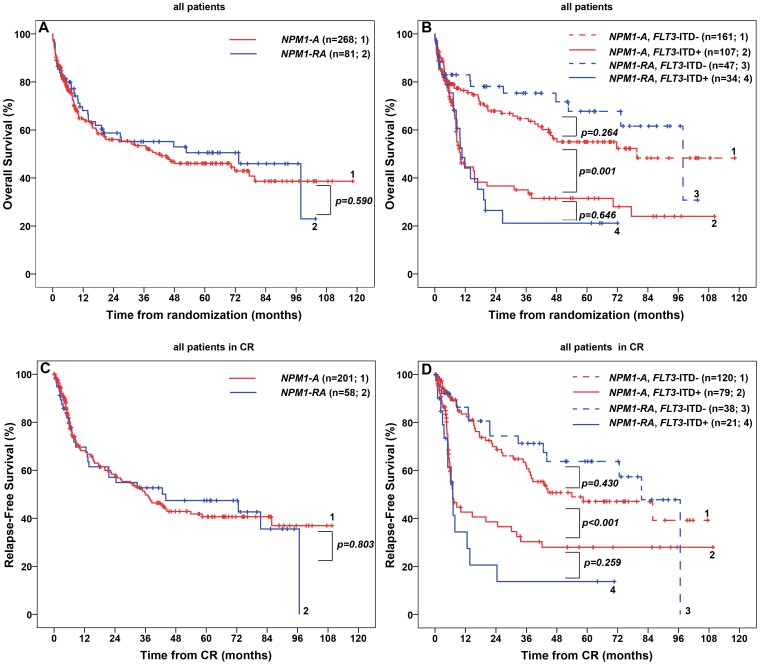

We did not observe any significant difference between patients with NPM1 type A and rare mutations in clinical or molecular parameters, in particular, there was no difference regarding OS and RFS ( Figures 1A and 1C , Table S1 in File S1).

Figure 1. Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 349 patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study.

(A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. (C) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; FLT3-ITD+, presence of an internal tandem duplication in the fms-related tyrosine 3 gene; FLT3-ITD-, absence of an internal tandem duplication in the fms-related tyrosine 3 gene; NPM1-A, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene consisting of an insertion of the tetranucleotide TCTG; NPM1-RA, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene other than type A.

In patients with NPM1 mutation (NPM1+), the presence of an FLT3-ITD (FLT3-ITD+) caused significant changes in WBC, LDH level, amount of bone marrow blasts and a decrease in OS and RFS compared to patients without FLT3-ITD (FLT3-ITD-) (Figure S2 in File S1).

We did not observe any difference in patient characteristics, OS or RFS between NPM1-A/FLT3-ITD- versus NPM1-RA/FLT3-ITD- patients ( Figure 1B and 1D , Table S1 in File S1). Similar results were obtained for NPM1-A/FLT3-ITD+ versus NPM1-RA/FLT3-ITD+ patients, except for WBC which was higher in the rare type group (p = 0.005).

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, parameters with independent adverse impact on OS and RFS were older age, a high WBC and the presence of an FLT3-ITD. Importantly, the NPM1 mutation type (NPM1-A versus NPM1-RA) was not significantly correlated with OS or RFS, neither in univariable, (Table S3 in File S1) nor in multivariable Cox regression models ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Multivariable Cox regression models for OS and RFS in 349 NPM1-mutated patients.

| independent prognostic factors | comparison | OS | RFS | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Age | per 10 years | 1.71 | 1.44–2.03 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.28–1.87 | <0.001 |

| WBC | 109/L, per 10-fold increase | 1.63 | 1.16–2.30 | 0.005 | 1.71 | 1.15–2.56 | 0.009 |

| FLT3-ITD | positive versus negative | 2.04 | 1.40–2.96 | <0.001 | 2.45 | 1.60–3.75 | <0.001 |

| NPM1 mutation type | NPM1-A | 1.06 | 0.71–1.59 | 0.764 | 0.89 | 0.57–1.38 | 0.590 |

| versus | |||||||

| NPM1-RA | |||||||

White blood cell count, platelet count, hemoglobin level, lactase dehydrogenase level, bone marrow blasts, de novo AML versus non de novo AML, performance status, sex, age, type A versus rare type NPM1 mutation, FLT3-ITD, monoallelic CEBPA mutations, biallelic CEBPA mutations were included in the Cox regression models for OS and RFS with backward elimination. The analyses were performed using 313 patients for OS and 227 RFS who had data for all these variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as indicating significant differences. All parameters that did not have a significant impact on OS or RFS are not shown in the table, except for the NPM1 mutation type.

Abbreviations: CEBPA, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha gene; CI, confidence interval; FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene; HR, hazard ratio; negative, absence of FLT3-ITD; NPM1, nucleophosmin gene; NPM1-A, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene leading to the insertion of the tetranucleotide TCTG; NPM1-RA, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene other than type A; OS, Overall survival; p, p value; positive, presence of FLT3-ITD; RFS, Relapse-free survival; WBC, white blood cell count.

Similar results were obtained for the effect of NPM1-A versus NPM1-RA on OS and RFS in patients receiving chemotherapy only (without allogeneic transplantation in first CR), patients with de novo AML and patients <60 or ≥60 years (text and Figures S3, S4 and S5 in File S1).

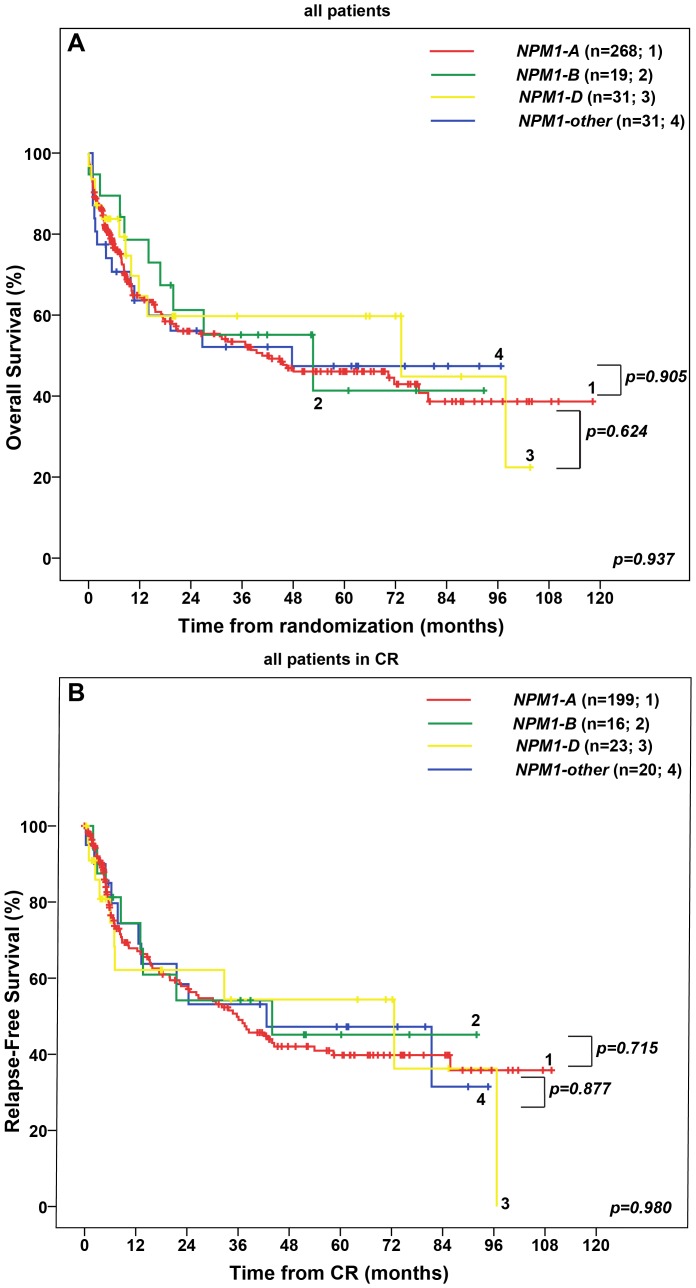

B) NPM1 mutation types A versus B versus D versus other mutations

We did not find a statistical difference with regard to OS and RFS in patients with NPM1 type A, B, D and other mutations (p = 0.937, p = 0.980) ( Figures 2A and 2B ). Furthermore, OS and RFS were similar between patients with type A, B, D and other mutations without an additional FLT3-ITD (data not shown). NPM1-A/FLT3-ITD+ patients showed similar OS and RFS as patients with NPM1-B/FLT3-ITD+, NPM1-D/FLT3-ITD+ and NPM1-other/FLT3-ITD+ patiens (data not shown). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, older age, a high WBC and presence of a FLT3-ITD were associated with an adverse prognosis, whereas the type of NPM1 mutation (A versus B versus D versus other) was not significantly associated with OS or RFS (Table S4 in File S1). Similar results were obtained for patients not receiving allogeneic transplantation (text in File S1).

Figure 2. Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 349 patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study.

(A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 type B mutation versus NPM1 type D mutation versus NPM1 type other mutation. (B) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 type B mutation versus NPM1 type D mutation versus NPM1 type other mutation. Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; FLT3-ITD+, presence of an internal tandem duplication in the fms-related tyrosine 3 gene; FLT3-ITD-, absence of an internal tandem duplication in the fms-related tyrosine 3 gene; NPM1-A, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene consisting of an insertion of the tetranucleotide TCTG; NPM1-B, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene consisting of an insertion of the tetranucleotide CATG, NPM1-D, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene consisting of an insertion of the tetranucleotide CCTG, NPM1-other, mutation in the nucleophosmin gene other than NPM1 mutation types A, B, D.

Conclusions and Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the relevance of different NPM1 mutation types with regard to clinical and molecular patient characteristics and outcome.

In the literature only few published studies have addressed this topic revealing controversial results. Koh et al who investigated only patients without an additional FLT3-ITD, found a negative prognostic impact of rare type mutations on OS and duration of CR [4]. Their analyses were based on 18 NPM1-mutated de novo AML patients, 13 of which had a type A mutation versus 5 with a rare type mutation. Thus, conclusions are limited due to small sample size and, furthermore, patients were not treated homogeneously within a clinical trial.

In contrast, another study recently presented at the ASH meeting involving 603 NPM1-mutated patients with intermediate risk karyotype showed a trend towards a longer OS in rare type versus type A NPM1 mutations [5]. In the presence of an FLT3-ITD, type A patients had a worse OS compared to rare type mutations, whereas there was no difference between these groups in the absence of a FLT3-ITD.

Our study of a homogenous cohort with respect to treatment (all patients are treated within one clinical trial) and cytogenetics (all patients had a normal karyotype) did not reveal any difference in molecular and clinical parameters including CR rates, OS and RFS between type A and rare type NPM1 mutations. Even when our patients were stratified according to FLT3-ITD status the type of NPM1 mutation was not relevant for clinical outcome. This was also true comparing NPM1 mutation types A, B, D versus other. Moreover, the type of NPM1 mutation was not an independent prognostic factor in a multivariable analysis.

Except for the addition of a NES causing an aberrant cytoplasmatic localization of the mutated NPM1 protein, other biochemical consequences of different NPM1 mutation types on a protein level which might alter the binding of NPM1 targets have not been fully explored and warrant further investigation.

In light of the low frequency and diversity of rare NPM1 mutations, however, it is very challenging to assess their individual clinical relevance.

We conclude that the type of NPM1 mutation does not seem to play a role in risk stratification of cytogenetically normal AML.

Supporting Information

Data supplement. Text, NPM1 mutation type does not influence outcome - Subgroup analyses. A) NPM1 mutation type A versus rare type mutationsin 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only in 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only; in 330 patients with de novo AML; in patients <60 and ≥60 years of age. B) NPM1 mutation types A versus B versus D versus other mutations in 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only. Table S1, Characteristics of NPM1-mutated patients and comparison between those with type A and rare type with or without a FLT3-ITD. Table S2, Frequency of different types of NPM1 mutations. Table S3, Univariable Cox regression for overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). Table S4, Multivariable Cox regression models for OS and RFS in 349 NPM1-mutated patients. Figure S1, Overview of patient Selection. Figure S2, Influence of a FLT3-ITD in 349 NPM1-mutated patients on outcome. (A) OS in 349 NPM1-mutated patients. (B) RFS in NPM1-mutated patients in CR. Figure S3, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 292 patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study, not receiving allogeneic transplantation. (A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. (C) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. Figure S4, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 330 patients with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study. (A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. (C) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. Figure S5, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 197 patients <60 years and 152 patients ≥60 years with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study. (A) OS in patients <60 years with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients ≥60 years with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (C) RFS in patients <60 with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients ≥60 with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all centers and patients that participated in the AMLCG99 trial.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. The data cannot be made available in a public repository due to ethical restrictions (case sensitive private patient data). The data can be made available upon request, and requests may be sent to the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, et al. (2005) Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med 352: 254–266 10.1056/NEJMoa041974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Federici L, Falini B (2013) Nucleophosmin mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: a tale of protein unfolding and mislocalization. Protein Sci 22: 545–556 10.1002/pro.2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falini B, Bolli N, Shan J, Martelli MP, Liso A, et al. (2006) Both carboxy-terminus NES motif and mutated tryptophan(s) are crucial for aberrant nuclear export of nucleophosmin leukemic mutants in NPMc+ AML. Blood 107: 4514–4523 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koh Y, Park J, Bae EK, Ahn KS, Kim I, et al. (2009) Non-A type nucleophosmin 1 gene mutation predicts poor clinical outcome in de novo adult acute myeloid leukemia: differential clinical importance of NPM1 mutation according to subtype. Int J Hematol 90: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alpermann T, Haferlach C, Dicker F, Eder C, Kohlmann A, et al. (2013) Evaluation Of Different NPM1 Mutations In AML Patients According To Clinical, Cytogenetic and Molecular Features and Impact On Outcome. Blood 122: 51–51 Available: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/content/122/21/51.abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Büchner T, Berdel WE, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, Schnittger S, et al. (2009) Age-related risk profile and chemotherapy dose response in acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 27: 61–69 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaffer LG, McGowan-Jordan J, Schmid M (2013) ISCN 2013: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (2013) - International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Karger publishers.

- 8. Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, Schaich M, Schäkel U, et al. (2002) Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood 99: 4326–4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schnittger S, Schoch C, Dugas M, Kern W, Staib P, et al. (2002) Analysis of FLT3 length mutations in 1003 patients with acute myeloid leukemia: correlation to cytogenetics, FAB subtype, and prognosis in the AMLCG study and usefulness as a marker for the detection of minimal residual disease. Blood 100: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider F, Hoster E, Unterhalt M, Schneider S, Dufour A, et al. (2012) The FLT3ITD mRNA level has a high prognostic impact in NPM1 mutated, but not in NPM1 unmutated, AML with a normal karyotype. Blood 119: 4383–4386 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dufour A, Schneider F, Metzeler KH, Hoster E, Schneider S, et al. (2010) Acute myeloid leukemia with biallelic CEBPA gene mutations and normal karyotype represents a distinct genetic entity associated with a favorable clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol 28: 570–577 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benthaus T, Schneider F, Mellert G, Zellmeier E, Schneider S, et al. (2008) Rapid and sensitive screening for CEBPA mutations in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 143: 230–239 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, Mecucci C, Tschulik C, et al. (2005) Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood 106: 3733–3739 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dohner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, Scholl C, Rücker FG, et al. (2005) Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: interaction with other gene mutations. Blood 106: 3740–3746 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schemper M, Smith TL (1996) A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials 17: 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data supplement. Text, NPM1 mutation type does not influence outcome - Subgroup analyses. A) NPM1 mutation type A versus rare type mutationsin 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only in 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only; in 330 patients with de novo AML; in patients <60 and ≥60 years of age. B) NPM1 mutation types A versus B versus D versus other mutations in 292 patients receiving chemotherapy only. Table S1, Characteristics of NPM1-mutated patients and comparison between those with type A and rare type with or without a FLT3-ITD. Table S2, Frequency of different types of NPM1 mutations. Table S3, Univariable Cox regression for overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). Table S4, Multivariable Cox regression models for OS and RFS in 349 NPM1-mutated patients. Figure S1, Overview of patient Selection. Figure S2, Influence of a FLT3-ITD in 349 NPM1-mutated patients on outcome. (A) OS in 349 NPM1-mutated patients. (B) RFS in NPM1-mutated patients in CR. Figure S3, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 292 patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study, not receiving allogeneic transplantation. (A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. (C) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. Figure S4, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 330 patients with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study. (A) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. (C) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation with or without an additional FLT3-ITD. Figure S5, Overall Survival (OS) and Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) in 197 patients <60 years and 152 patients ≥60 years with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and NPM1 mutation treated in the AMLCG99 study. (A) OS in patients <60 years with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (B) OS in patients ≥60 years with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (C) RFS in patients <60 with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation. (D) RFS in patients ≥60 with NPM1 type A mutation versus NPM1 rare type mutation.

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. The data cannot be made available in a public repository due to ethical restrictions (case sensitive private patient data). The data can be made available upon request, and requests may be sent to the corresponding author.