Abstract

Tamoxifen, a pioneering selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), has long been a therapeutic choice for all stages of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. The clinical application of long-term adjuvant antihormone therapy for the breast cancer has significantly improved breast cancer survival. However, acquired resistance to SERM remains a significant challenge in breast cancer treatment. The evolution of acquired resistance to SERMs treatment was primarily discovered using MCF-7 tumors transplanted in athymic mice to mimic years of adjuvant treatment in patients. Acquired resistance to tamoxifen is unique because the growth of resistant tumors is dependent on SERMs. It appears that acquired resistance to SERM is initially able to utilize either E2 or a SERM as the growth stimulus in the SERM-resistant breast tumors. Mechanistic studies reveal that SERMs continuously suppress nuclear ER-target genes even during resistance, whereas they function as agonists to activate multiple membrane-associated molecules to promote cell growth. Laboratory observations in vivo further show that three phases of acquired SERM-resistance exists, depending on the length of SERMs exposure. Tumors with Phase I resistance are stimulated by both SERMs and estrogen. Tumors with Phase II resistance are stimulated by SERMs, but are inhibited by estrogen due to apoptosis. The laboratory models suggest a new treatment strategy, in which limited-duration, low-dose estrogen can be used to purge Phase II-resistant breast cancer cells. This discovery provides an invaluable insight into the evolution of drug resistance to SERMs, and this knowledge is now being used to justify clinical trials of estrogen therapy following long-term antihormone therapy. All of these results suggest that cell populations that have acquired resistance are in constant evolution depending upon selection pressure. The limited availability of growth stimuli in any new environment enhances population plasticity in the trial and error search for survival.

Keywords: selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), resistance, estrogen, estrogen-induced apoptosis

1. Introduction

The estrogen receptor (ER), including estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor (ERβ), mediates the biological effects of estrogen for the development and progression of breast cancer, and serves as an important diagnostic and therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment. Targeted therapy to ERα is the most successful strategy in breast cancer treatment and prevention. These endocrine therapies include the aromatase inhibitors (AIs) that indirectly target the ER by blocking the synthesis of estrogen from androgen in peripheral tissues, show improved efficacy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients (1, 2). Another strategy option is to use pure antiestrogens (also called selective estrogen receptor down-regulators, SERDs), such as fulvestrant, which have no agonist activity and cause degradation of ER (3). Fulvestrant has been approved to treat advanced breast cancer after tamoxifen failure (4, 5). The most widely used therapy for ER-positive breast cancer are the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), which are synthetic molecules that bind to ER and can modulate its transcriptional capabilities in different estrogen target tissues. Tamoxifen (Figure 1), the pioneering SERM, is extensively used for targeted therapy of ER-positive breast cancers (6) and is also approved as the first chemo-preventive agent for lowering breast cancer incidence in high risk women (7). The therapeutic and preventive efficacy of tamoxifen was initially proven by a series of experiments in the laboratory which laid the foundation of its clinical applications (8). A 5-year course (long-term) of adjuvant tamoxifen treatment in patients is superior to 1–2 years of treatment, demonstrating that longer is better (9–11). This illustrates the translation of the earlier laboratory principle (12). Currently, 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen is recommended to be optimal, however, two recent trials of 5 versus 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy show 10-year is superior (13, 14). Unfortunately, the use of tamoxifen is associated with de novo and acquired resistance and some undesirable side effects, such as thromboembolic events and increased rates of endometrial cancer (15). However, this latter effect is only noted in postmenopausal patients. The study of the molecular mechanisms of resistance provides an opportunity to precisely understand the mechanism of SERMs action which may further help in designing new and improved SERMs. Clinical studies demonstrate that another SERM, raloxifene (Figure 1), which is primarily used to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis; simultaneously reduces the risk of breast cancer (16–18). Raloxifene is as effective as tamoxifen in preventing breast cancer in postmenopausal women but with fewer side effects (19, 20). The third generation SERM, bazedoxifene (Figure 1), administrated with conjugated estrogens, represents a promising alternative to hormone therapy for the prevention of osteoporosis and the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms in non-hysterectomized postmenopausal women (21, 22). Overall, these findings open a new horizon for SERMs as a class of drug which can not only be used for therapy and prevention of breast cancer, but also for various other diseases and disorders. We will provide a basic background of SERMs, the current progress of the SERMs, and focus in detail on the evolution of acquired resistance to endocrine therapy by selection pressure on cell populations.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of three SERMs--- tamoxifen, raloxifene, and bazedoxifene.

2. Basic Molecular Mechanisms of SERM action

The antitumor effects of SERMs are thought to be due to its antiestrogenic activity, mediated by competitive inhibition of estrogen binding to ER (23). SERMs are antiestrogenic in the breast but estrogen-like in the bones and reduce circulating cholesterol levels. This discovery in the laboratory suggests the clinical application to simultaneously prevent osteoporosis, coronary heart disease, and breast cancer (24, 25). However, SERMs also have different degrees of estrogenicity in the uterus. Tamoxifen exhibits partial agonistic activity thought to be associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer (26–30), but raloxifene and bazedoxifene do not (30–32). Coregulators are crucial in determining the final tissue outcome in terms of transcriptional activation or repression mediated by SERMs (33–36). Now dozens of coactivators are known, and corepressor molecules also exist to prevent the gene transcription by unliganded receptors (33–36). X-ray crystallography of the ligand binding domains (LBD) of the ER liganded with either estrogens or antiestrogens show the potential of ligands to promote or prevent coactivator binding based on the shape of the estrogen or anti-ER complex (37, 38). Evidence has accumulated that the broad spectrum of ligands that bind to the ER can create a broad range of ER complexes that are either fully estrogenic or antiestrogenic at a particular target site (39). Thus, a mechanistic model of estrogen action and antiestrogen action has emerged (40, 41) based on the shape of the ligand that programs the complex to adopt a particular shape that ultimately interacts with coactivators or corepressors in target cells to determine the estrogenic or antiestrogenic response, respectively.

The three homologous members of the p160 SRC family (SRC1, SRC2 and SRC3) mediate the transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors and other transcription factors, and are the most studied of all the transcriptional co-activators (42). The relative abundance of SRC1 in uterine cells is responsible for the agonistic activity of tamoxifen, whereas the low SRC1 level in breast cancer cells (33). However, raloxifene does not recruit SRC1 even in the uterine cells (33), suggesting that the interaction with each specific ligand elicits a unique conformation of the receptor that is critical for the interaction of co-regulators. Our finding indicates that tamoxifen does not recruit SRC3 to the promoter of ER-target gene, pS2 and acts as an estrogen antagonist in wild-type breast cancer cells (43). These observations further provide an explanation for the earlier studies, where tamoxifen has been reported to induce growth of endometrial cancer cells but not of breast cancer cells in athymic mice (29) and also that the agonistic property of raloxifene is less in endometrial cancer cells (30). Currently, there is no direct evidence about the interaction between bazedoxifene and coactivators. Molecular modeling studies demonstrate that bazedoxifene binds to ERα in an orientation similar to raloxifene (44). Tamoxifen, raloxifene, and bazedoxifene all exhibit antiestrogenic activity to inhibit ER-target genes and modulate the ER signal transduction pathway in breast cancer (45). However, bazedoxifene is distinct from other SERMs in its ability to inhibit antihormone resistant breast cancer growth in vitro and in vivo (44, 45). In our SERM-resistant cell line, bazedoxifene reduces levels of ERα protein and blocks stimulation induced by 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

3. Drug Resistance to SERMs

There are three types of resistance to SERMs: metabolic resistance, de novo resistance and acquired resistance (46). Metabolic (47) and de novo (46) resistance have been extensively reviewed and will not be considered further because they do not influence the modulation or inhibition of long-term growth in breast cancer. The fact that SERMs initially act as estrogen antagonists in breast cancer to switch off growth during the successful treatment of breast cancer, but then cause SERM-stimulated breast cancer growth is a unique form of acquired drug resistance. The cell populations are clearly being modulated over years of therapy so that those cells that can adapt and grow in an antiestrogenic environment now dominate. Understanding this process provides an opportunity to save more lives.

The aforementioned studies (section 2) describe the mechanics of antiestrogen action, but do not define the modulation of estrogenic properties of individual SERMs at the ER or in fact, how ER-positive tumor cells grow spontaneously in an estrogen-deprived environment. An early study of acquired resistance to tamoxifen identified a D351Y mutation in vivo, in some but not all, tamoxifen-stimulated tumors grown in athymic mice (48, 49). Subsequent studies, in engineered cells, showed that this amino acid could modulate estrogenic action of SERMs at an estrogen response gene target (50–52). Indeed, the D351Y would convert the antiestrogenic raloxifene-ER complex to an estrogenic complex (53, 54). This was the first natural mutation to convert an antiestrogenic to an estrogenic complex. The significance of the D351Y amino acid has recently been illustrated in five reports (55–59) which find that mutations in amino acid D537 and Y538 are associated with acquired resistance to antihormone therapy in breast cancer metastases. It is argued that the unoccupied receptor is now able to close helix 12 and trigger growth by anchoring at D351.

The mutations in the ER is an interesting and significant finding in patient metastases, although none or very fewer are noted in primary tumors (55–59). So the question arises how the development of acquired resistance occurs to subvert an effective antiestrogenic therapy like tamoxifen for the long-term treatment of breast cancer. The evidence all points to the evolution of cell populations that initially respond to therapy, but through Darwinian principles of survival, cells with chance mutation in growth pathway replicate in the face of adversity. The plasticity of cell populations ebb and flow like the tide with each new antihormonal treatment. This results in cell lines that eventually thrive in each new environment. It is the story of cellular changes that occur over years in patients that can only be understood by creating selection studies over years in the laboratory. We will present the story so far.

3.1 Models of Acquired Resistance to Antihormone Therapy

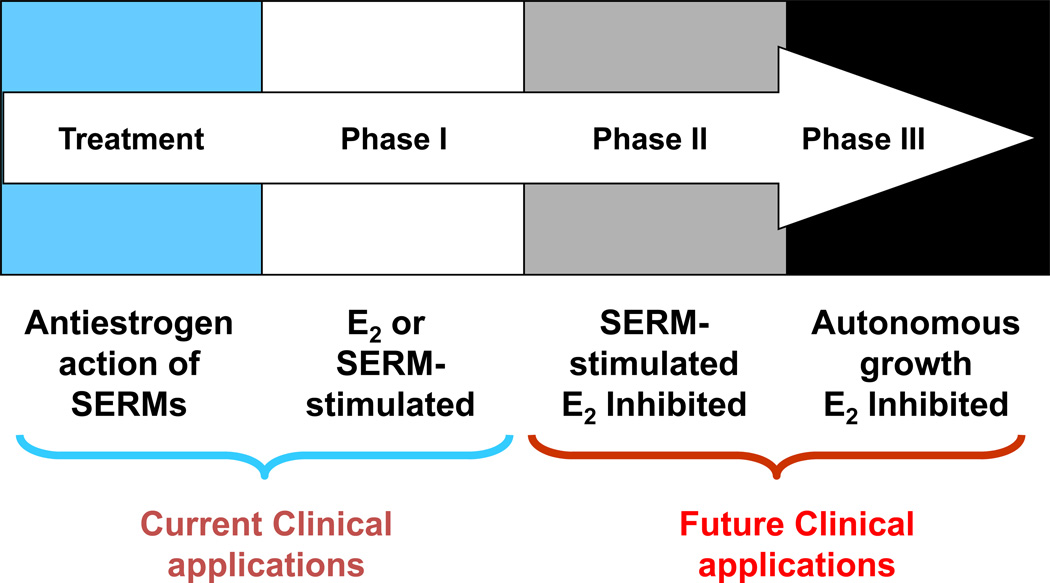

The evolution of acquired resistance to SERM treatment was primarily discovered using MCF-7 tumors transplanted in athymic mice to mimic years of adjuvant treatment in patients (60–62). Acquired resistance to SERMs is unique because the growth of resistant tumors is dependent on SERMs (60–62). Thus, it appears that acquired resistance to SERMs is initially able to utilize either E2 or a SERM as the growth stimulus in the ER-positive SERM-resistant breast tumors (63, 64). However, no mechanism has been established to explain this paradox. Laboratory observations further show that three phases of acquired tamoxifen-resistance exists (Figure 2), which depend on the length of tamoxifen exposure (65). Tumors with Phase I resistance are stimulated by estrogen and tamoxifen but inhibited by AIs and fulvestrant (63, 64). This form of acquired resistance to tamoxifen takes about a year or two to develop during retransplantation of tumors into tamoxifen-treated athymic mice. Subsequent clinical studies more than a decade later showed that both AIs and fulvestrant were equivalent options following tamoxifen failure in metastatic breast cancer (4, 5). Tumors with Phase II resistance are stimulated by tamoxifen but are inhibited by estrogen due to apoptosis (65). The results of laboratory models (62, 66) suggested new treatment strategies, in which limited-duration, low-dose estrogen can be used to purge Phase II-resistant breast cancer cells and act as a salvage therapy following long-term antihormone therapy. This discovery provides an invaluable insight into the evolution of drug resistance to SERMs (67) and this knowledge has been used to justify clinical trials of estrogen therapy following long-term antihormone therapy (68–70).

Figure 2.

The evolution of resistance to SERMs after long-term therapy. Phase I acquired resistance develops after a year or two of therapy of ER positive metastatic breast cancer. Phase II acquired resistance occurs after 5 years of SERM treatment in the laboratory or potentially as occult disease during 5 years adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Phase III acquired resistance potentially develops after indefinite therapy for ER positive breast cancer.

However, the rapid development of Phase I resistance to tamoxifen begs to question “why is long-term (5 years or more) adjuvant tamoxifen therapy so effective as an adjuvant treatment? There is a 50% decrease in mortality compared to historical no treatment controls in the 10 years of tamoxifen has stopped (14). If the athymic mouse model replicates human disease (71), the clinical studies of more than 2 years of adjuvant tamoxifen would all have failed.” But micrometastatic disease is clearly not established metastatic breast cancer. There is not the same bulk or vascularity, nor is there the same genetic variation and cellular plasticity eager to survive. The answer emerged from laboratory studies of the retransplantation of tamoxifen-stimulated tumors over a 5 year period. What emerged was the serendipitous finding that physiological estrogen is now a trigger for death, but tamoxifen therapy is the signal to sustain cancer cell homeostasis. Phase II acquired resistance evolved from Phase I acquired resistance to tamoxifen and exposes a vulnerability in breast cancer. Estrogen, the signal for breast cancer cell survival and growth, could also become the signal for apoptosis to be triggered in a prepared population of cells only able to grow in estrogen-deprived conditions. The ER is paradoxically selective either in the cells that have been previously programmed for growth in an estrogen-rich environment or prepared for execution in those cells that cling to their survival after year in a long-term estrogen-free environment.

A similar story has also occurred over the past 20 years with the development of models to study antihormone resistance to AIs. This followed the vigorous evaluation of multiple AIs for the treatment of breast cancer, and AIs became the antihormone therapy of choice for adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal patients with ER-positive disease (2). The discovery that breast cancer cells, in particular MCF-7 cells, had been grown routinely in the redox indicator phenol red (72) that contains a contaminant with estrogenic activity, revolutionized options to solve the question of what happens to hormone-responsive cells once starved of estrogen i.e. AI therapy. Short-term estrogen withdrawal results in expansion of the ER pool in ER-positive MCF-7 cells and following a crises period during the first month, a population of cells grows out that is hormone-independent for growth (73, 74). The Santen’s group provided compelling evidence that the long-term estrogen-deprived cells (LTED) had acquired hypersensitivity to low estrogen concentration in the local environment (75, 76). He proposed that this was a reasonable explanation for the failure of AI therapy i.e. the drug could not prevent the synthesis of all estrogen and there is also estrogen in the environment e.g. phytoestrogens or endocrine disruptors. In other words, the cells survive with a minimal survival system; the population grows successfully with what is available. However, in the wake of findings (62) that physiological estrogen causes tamoxifen (estrogen withdrawal) resistant MCF-7 tumor regression in athymic mice after LTED (5 years of tamoxifen), some other process must be occurring; the growth stimulus returns–cells die! Long-term estrogen-deprived MCF-7 cells in culture have a concentration related apoptotic response to exogenous estrogen (77). High concentrations kill all cells thereby providing an explanation for Haddow’s 1944 earlier observation that estrogen can be used at high doses to treat breast cancer a decade after menopause (78). However, the trigger actually is initiated in LTED cells by low concentrations of estrogen in the physiological range (77, 79). However, Santen had been using a population of LTED MCF-7 cells and another approach to answer the question occurred in parallel by others. Two clones of LTED MCF-7 breast cancer cells were derived, characterized, and stored without further study following their initial reports in the 1990’s (80, 81). The MCF-7:5C clone (80) was originally described as being completely refractory to either estrogen or antiestrogen despite in fact it was ER-positive and progesterone receptor (PgR)-negative. By contrast, the MCF-7:2A clone (81) was unaffected by estrogen in a 7 day growth assay, but antiestrogens inhibited spontaneous growth; estrogen increased PgR synthesis in these ER-positive cells.

However, re-evaluation of these clones (2A and 5C) a decade later created a surprise. The MCF-7:2A cells had a delayed apoptotic response based on increased glutathione levels; slow cell death could be triggered by physiological estrogen after 7 days and enhanced apoptosis facilitated using the blocker of glutathione synthesis, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) (82–84). Changing media conditions caused early catastrophic apoptosis with physiological estrogen in MCF-7:5C cells within a week (85, 86). Cells grew spontaneously in ovariectomized athymic mice and physiological estrogen caused complete tumor regression within 14 days (86). Our supersensitive MCF-7:WS8 cells that grew with minute, radioimmunologically undetectable levels of estrogen, MCF-7:5C and MCF-7:2A cells all became the conduit for understanding estrogen-induced apoptosis as a consequence of acquired resistance to both AIs and phase II tamoxifen- or raloxifene-resistant growth (87–97).

3.2 Melding the models

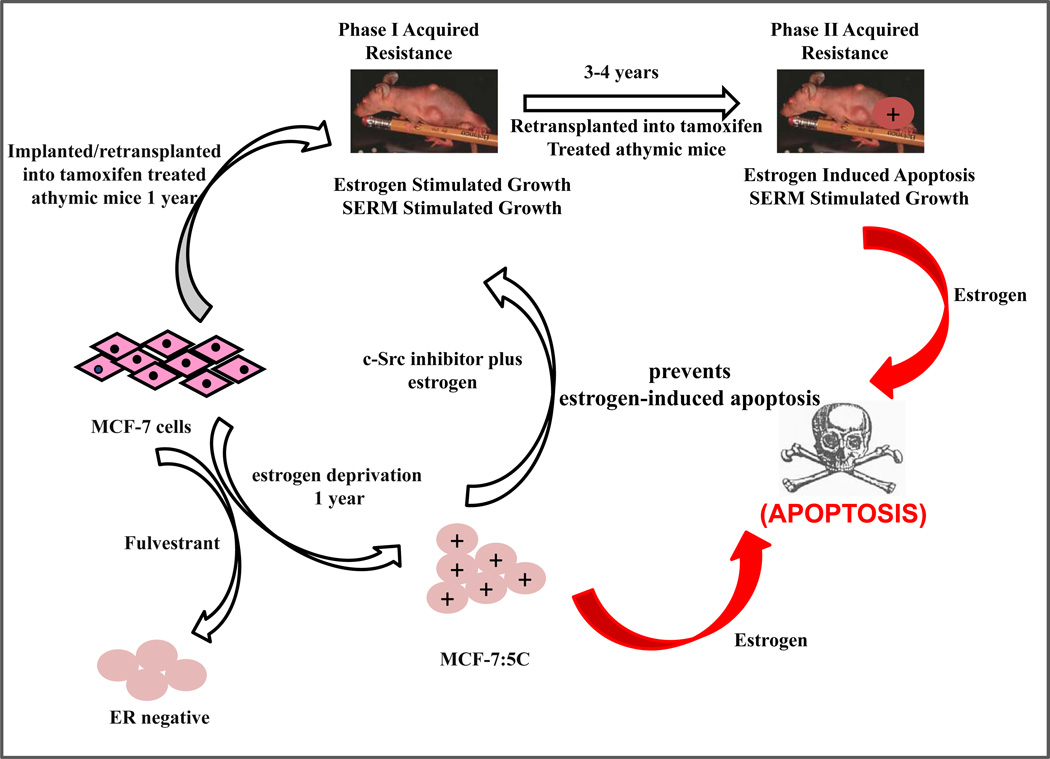

By creating selection pressure over months or years, the development of acquired resistance to antihormone resistance is forced to evolve and create new surviving cell populations based on the restrictions in the environment. In Figure 3, we have illustrated how models in vivo of acquired resistance to tamoxifen that requires 5 years to evolve and consolidate, can potentially be linked to models of AI resistance in vitro (MCF-7:5C).

Figure 3.

The melding of model systems. During the past 25 years, the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line has been used to recapitulate an evolving model in vivo of acquired tamoxifen resistance (62) observed in clinical breast cancer. In parallel, the same cell line has been used to recapitulate models in vitro of estrogen deprivation using either fulvestrant, that destroys the ER protein, or aromatase inhibitors that create a long-term estrogen-deprived state. The cells derived from estrogen deprivation with fulvestrant loose the ER (90), but estrogen deprivation in an estrogen-free environment in vitro increases the ER level. Clones grow out that are sensitive to estrogen-induced apoptosis (86). A c-Src inhibitor blocks estrogen-induced apoptosis in the short-term (94), but long-term (2 months) treatment with estrogen plus a c-Src inhibitor results in a new populations of cells (MCF-7:PF) (96) that recapitulates in vitro Phase I resistance to SERMs in vivo. These data, accumulated over decades, illustrate the plasticity of cell populations in that successful attempt to adapt to hostile environment.

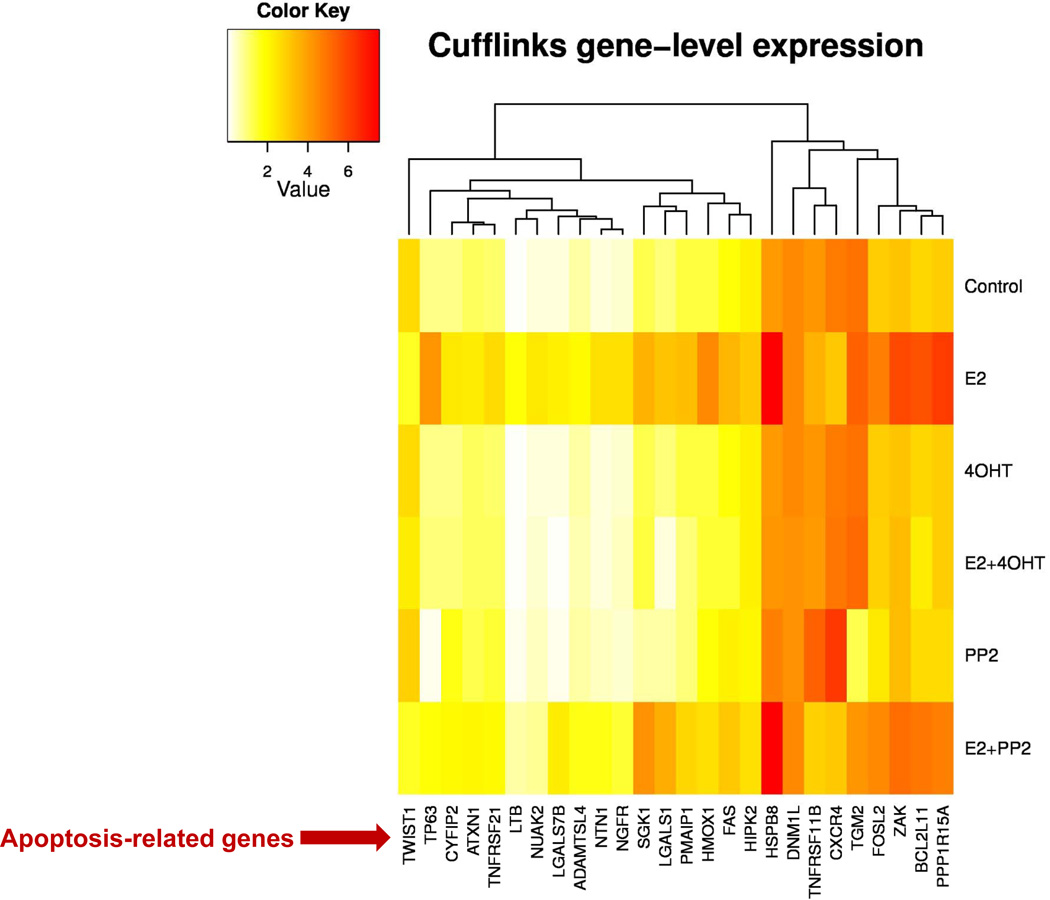

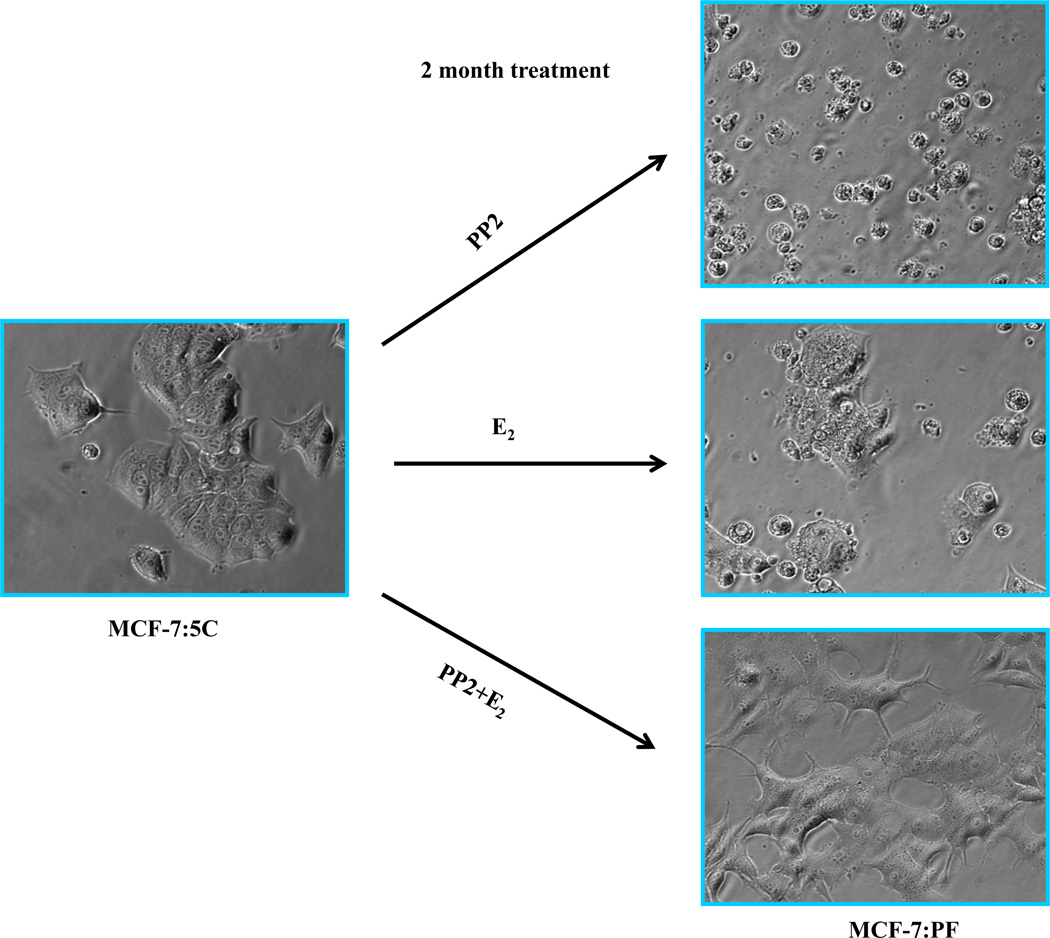

Our recent publications establish that estrogen induces apoptosis through endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress (84, 87, 94). A variety of apoptosis-related genes are activated by estrogen in MCF-7:5C and MCF-7:2A cells (84, 94, and Fig. 4). The finding that the c-Src tyrosine kinase is increased in MCF-7:5C cells (94) and inhibition of c-Src in short-term (7 days) experiments will reversibly block estrogen-induced apoptosis (94, 95), created an opportunity to determine what long-term inhibition of c-Src in the presence of estrogen would do to the biological properties of the cell populations (96). A two month period of selection pressure was chosen, as this is the time period used clinically to evaluate tumor response to therapy. The results of the three long-term therapies are illustrated in Figure 5 based on analysis of the resulting populations. Estrogen alone causes early catastrophic apoptosis but the resulting cell population that results after 2 months of continuous treatment consists of a balance of apoptosis and growth thereby restricting the outgrowth of cells. The c-Src inhibitor is a reversible blocker and the cells revert to the original MCF-7:5C cell phenotype with estrogen-induced apoptosis upon wash out (96). However, the cell populations (MCF-7:PF) that grow out under the pressure of estrogen plus the c-Src inhibitor is particularly interesting as, for the first time, it replicates Phase I acquired resistance to SERMs in vitro. The cells grow robustly with estrogen but also SERMs will stimulate growth in vitro based on their individual intrinsic estrogenic efficacy as partial agonists.

Figure 4.

The c-Src inhibitor and 4-hydroxytamoxifen block apoptosis-related genes induced by estrogen in MCF-7:5C cells. This result has been reported in reference 94. MCF-7:5C cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), E2 (10−9mol/L), 4-OHT (10−6mol/L), E2 (10−9mol/L) plus 4-OHT (10−6 mol/L), PP2 (5×10−6mol/L), E2 (10−9mol/L) plus PP2 (5×10−6mol/L) respectively for 72 hours. Cells were harvested in TRIzol for RNA-sequence analysis.

Figure 5.

The c-Src inhibitor completely blocks E2-induced apoptosis after long-term treatment. MCF-7:5C cells were long-term treated with vehicle (0.1% EtOH), PP2 (5×10−6mol/L), E2 (10−9 mol/L), and E2 (10−9mol/L) plus PP2 (5×10−6mol/L) in T25 flasks for 8 weeks. Cells were photographed under bright field illumination at (×20) magnification (Zeiss).

Further investigation suggests that ER is a major driver of growth utilized by both E2 and SERMs in resistant models in vivo (60, 63) and in vitro (96). In contrast to E2 that activates classical ER-target genes, SERMs continue to act as effective antiestrogens to inhibit classical ER-target genes, even at the time of growth stimulation. This result is consistent with our previous finding in vivo that growth of tumors by tamoxifen or fulvestrant is potentially independent of ER transcriptional activity, as evidenced by lack of induction of E2-responsive genes (90). Other groups have reported similar observations with tamoxifen suppressing classical ERE-regulated genes despite acquired resistance in vitro (98) or in vivo (99). A significant alteration of ER function observed in SERM-resistant cells is the activation of multiple membrane-associated molecules including focal adhesion molecules, adapter proteins, and growth factor receptor (Fig. 6). All of these integral adaptations contribute to SERM-resistance.

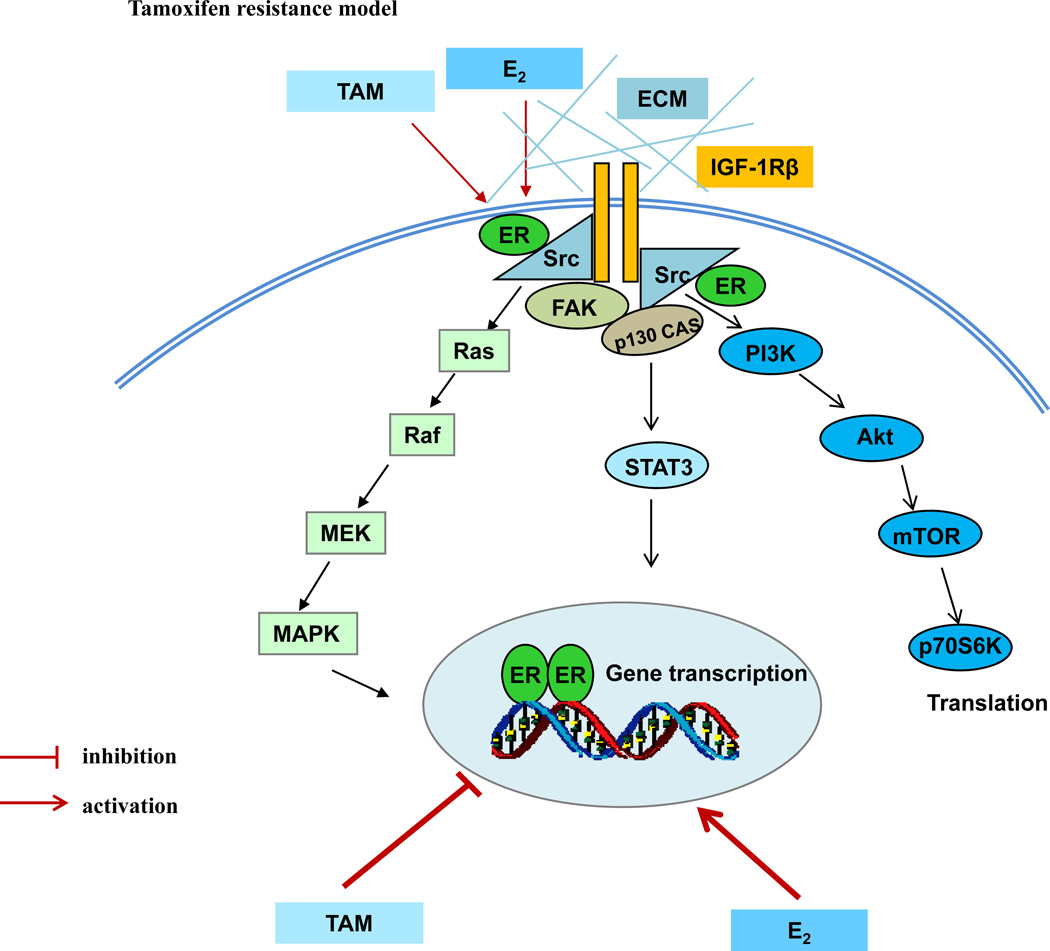

Figure 6.

Genomic and nongenomic signal transduction pathways in tamoxifen-resistant model. Estrogen (E2) and tamoxifen (TAM) exert differential functions on nuclear ER. E2 activates classical ER-target genes but TAM acts to block gene activation. Both E2 and TAM increases the non-genomic activity of ER through membrane-associated molecules such as extracellular matrix (ECM), c-Src, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor beta (IGF-1Rβ), and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) to enhance downstream signaling cascades.

4. Challenges and conclusions

Over the past 40 years, we have witnessed a dramatic improvement in the survivorship of the majority of patients with a diagnosis of ER-positive breast cancer (100, 101). Although extensive studies have advanced the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the acquired SERM-resistance, acquired resistance to SERMs is not one-dimensional with a simple solution. Resistant cell populations are in constant evolution depending upon selection pressure and the availability of growth stimuli that enhances population plasticity and survival of new clones. Breast cancer cells have the potential to integrally modulate a variety of membrane-associated molecules to subvert long-term nuclear pressure exerted by SERMs. This results in the promotion of cell growth (Figure 6). These functional alterations lead to acquired SERM resistance. As a result, the strategic definition of molecular mechanisms driving the development of endocrine resistance is an important and proactive first step to improve therapy. How to prioritize and advance individualized treatment is another challenge to improve the therapeutic efficacy of antihormone therapy (102).

Acknowledgements

VCJ is supported by the Department of Defense Breast Program under Award number W81XWH-06-1-0590 Center of Excellence; subcontract under the SU2C (AACR) Grant number SU2C-AACR-DT0409; the Susan G Komen For The Cure Foundation under Award number SAC100009; GHUCCTS CTSA (Grant # UL1RR031975) and the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Core Grant NIH P30 CA051008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jordan VC, Brodie AMH. Development and evolution of therapies targeted to the estrogen receptor for the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Steroids. 2007;72:7–25. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, Coates A, Forbes J, Bliss J, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:509–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariazi EA, Lewis-Wambi JS, Gill SD, Pyle JR, Ariazi JL, Kim HR, et al. Emerging principles for the development of resistance to antihormonal therapy: implications for the clinical utility of fulvestrant. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne CK, Pippen J, Jones SE, Parker LM, Ellis M, Come S, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and tolerability of fulvestrant versus anastrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer progressing on prior endocrine therapy: results of a North American trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3386–395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howell A, Robertson JF, Quaresma Albano J, Aschermannova A, Mauriac L, Kleeberg UR, et al. Fulvestrant, formerly ICI 182,780, is as effective as anastrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer progressing after prior endocrine treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3396–3403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen EV, Jordan VC. The estrogen receptor: a model for molecular medicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1980–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: catalyst for the change to targeted therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelber RD, Cole BF, Goldhirsch A, Rose C, Fisher B, Osborne CK, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy plus tamoxifen compared with tamoxifen alone for postmenopausal breast cancer: meta-analysis of quality-adjusted survival. Lancet. 1996;347:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Darby S, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan VC. Laboratory studies to develop general principles for the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer with antiestrogens: problems and potential for future clinical applications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1983;3:S73–S86. doi: 10.1007/BF01855131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The aTTom Collaborative Group. aTTom: Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6,953 women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, Gray R, Arriagada R, Raina V, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:805–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzick J, Powles T, Veronesi U, Forbes J, Edwards R, Ashley S, et al. Overview of the main outcomes in breast cancer prevention trials. Lancet. 2003;361:296–300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan VC. The rise of raloxifene and the fall of invasive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:831–833. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, Grady D, Powles TJ, Cauley JA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189–2197. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, et al. The Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR): Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-2 Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, et al. Update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial: Preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan VC. A(nother) scientific strategy to prevent breast cancer in postmenopausal women by enhancing estrogen-induced apoptosis? Menopause. 2014 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000220. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher JC, Shi H, Mirkin S, Chines AA. Changes in bone mineral density are correlated with bone markers and reductions in hot flush severity in postmenopausal women treated with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:1126–1132. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828ac8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen (ICI 46,474) as a targeted therapy to treat and prevent breast cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S269–S276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerner LJ, Jordan VC. Development of antiestrogens and their use in breast cancer: eighth Cain memorial award lecture. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4177–4189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan VC. SERMs: meeting the promise of multifunctional medicines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:350–356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Regan RM, Cisneros A, England GM, MacGregor JI, Muenzner HD, Assikis VJ, et al. Effects of the antiestrogens tamoxifen, toremifene, and ICI 182,780 on endometrial cancer growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1552–1558. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.20.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grese TA, Sluka JP, Bryant HU, Cullen GJ, Glasebrook AL, Jones CD, et al. Molecular determinants of tissue selectivity in estrogen receptor modulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14105–14110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Cedermark B, Glas U, Mattsson A, Silfverswärd C, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen in early breast cancer: occurrence of new primary cancers. Lancet. 1989;1:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottardis MM, Robinson SP, Satyaswaroop PG, Jordan VC. Contrasting actions of tamoxifen on endometrial and breast tumor growth in the athymic mouse. Cancer Res. 1988;48:812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottardis MM, Ricchio ME, Satyaswaroop PG, Jordan VC. Effect of steroidal and nonsteroidal antiestrogens on the growth of a tamoxifen-stimulated human endometrial carcinoma (EnCa101) in athymic mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3189–3192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, Pan K, Chines AA, Mirkin S, et al. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E189–E198. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirkin S, Komm BS, Pan K, Chines AA. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on endometrial safety and bone in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2013;16:338–346. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.717994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shang Y, Brown M. Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs. Science. 2002;295:2465–2468. doi: 10.1126/science.1068537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith CL, O'Malley BW. Coregulator function: a key to understanding tissue specificity of selective receptor modulators. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:45–71. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, et al. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/co-activator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engström O, et al. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wijayaratne AL, Nagel SC, Paige LA, Christensen DJ, Norris JD, Fowlkes DM, et al. Comparative analyses of mechanistic differences among antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5828–5840. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaufele F, Chang CY, Liu W, Baxter JD, Nordeen SK, Wan Y, et al. Temporally distinct and ligand-specific recruitment of nuclear receptor-interacting peptides and cofactors to subnuclear domains containing the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:2024–2039. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.12.0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall JM, McDonnell DP, Korach KS. Allosteric regulation of estrogen receptor structure, function, and coactivator recruitment by different estrogen response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:469–486. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.3.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Wu RC, O'Malley BW. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:615–630. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sengupta S, Obiorah I, Maximov PY, Curpan R, Jordan VC. Molecular mechanism of action of bisphenol and bisphenol A mediated by oestrogen receptor alpha in growth and apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:167–178. doi: 10.1111/bph.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis-Wambi JS, Kim H, Curpan R, Grigg R, Sarker MA, Jordan VC. The selective estrogen receptor modulator bazedoxifene inhibits hormone-independent breast cancer cell growth and down-regulates estrogen receptor α and cyclin D1. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:610–620. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.072249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wardell SE, Nelson ER, Chao CA, McDonnell DP. Bazedoxifene exhibits antiestrogenic activity in animal models of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: implications for treatment of advanced disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2420–2431. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan VC, O’Malley BW. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators and antihormonal resistance in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5815–5824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brauch H, Schwab M. Prediction of tamoxifen outcome by genetic variation of CYP2D6 in post-menopausal women with early breast cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:695–703. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf DM, Jordan VC. The estrogen receptor from a tamoxifen stimulated MCF-7 tumor variant contains a point mutation in the ligand binding domain. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;31:129–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00689683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf DM, Jordan VC. Characterization of tamoxifen stimulated MCF-7 tumor variants grown in athymic mice. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;31:117–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00689682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu H, Park WC, Bentrem DJ, McKian KP, Reyes Ade L, Loweth JA, et al. Structure-function relationships of the raloxifene-estrogen receptor-alpha complex for regulating transforming growth factor-alpha expression in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9189–9198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108335200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu H, Lee ES, Deb Los Reyes A, Zapf JW, Jordan VC. Silencing and reactivation of the selective estrogen receptor modulator-estrogen receptor alpha complex. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3632–3639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schafer JM, Liu H, Tonetti DA, Jordan VC. The interaction of raloxifene and the active metabolite of the antiestrogen EM-800 (SC 5705) with the human estrogen receptor. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4308–4313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levenson AS, Catherino WH, Jordan VC. Estrogenic activity is increased for an antiestrogen by a natural mutation of the estrogen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;60:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levenson AS, Jordan VC. The key to the antiestrogenic mechanism of raloxifene is amino acid 351 (aspartate) in the estrogen receptor. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1872–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeselsohn R, Yelensky R, Buchwalter G, Frampton G, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-α mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1757–1767. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merenbakh-Lamin K, Ben-Baruch N, Yeheskel A, Dvir A, Soussan-Gutman L, Jeselsohn R, et al. D538G mutation in estrogen receptor-α: A novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6856–6864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li S, Shen D, Shao J, Crowder R, Liu W, Prat A, et al. Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1116–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1446–1451. doi: 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, Green B, Sakr RA, Will M, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gottardis MM, Jordan VC. Development of tamoxifen-stimulated growth of MCF-7 tumors in athymic mice after long-term antiestrogen administration. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5183–5187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottardis MM, Wagner RJ, Borden EC, Jordan VC. Differential ability of antiestrogens to stimulate breast cancer cell (MCF-7) growth in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4765–4769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao K, Lee ES, Bentrem DJ, England G, Schafer JI, O'Regan RM, et al. Antitumor action of physiological estradiol on tamoxifen-stimulated breast tumors grown in athymic mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2028–2036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gottardis MM, Jiang SY, Jeng MH, Jordan VC. Inhibition of tamoxifen-stimulated growth of an MCF-7 tumor variant in athymic mice by novel steroidal antiestrogens. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4090–4093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee ES, Schafer JM, Yao K, England G, O'Regan RM, De Los Reyes A, et al. Cross-resistance of triphenylethylene-type antiestrogens but not ICI 182,780 in tamoxifen-stimulated breast tumors grown in athymic mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4893–4899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jordan VC. Selective estrogen receptor modulation: concept and consequences in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf DM, Jordan VC. A laboratory model to explain the survival advantage observed in patients taking adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1993;127:23–33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-84745-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jordan VC. The 38th David A. Karnofsky Lecture. The paradoxical actions of estrogen in breast cancer: survival or death? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3073–3082. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jordan VC, Lewis JS, Osipo C, Cheng D. The apoptotic action of estrogen following exhaustive antihormonal therapy: a new clinical treatment strategy. Breast. 2005;14:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lønning PE, Taylor PD, Anker G, Iddon J, Wie L, Jørgensen LM, et al. High-dose estrogen treatment in postmenopausal breast cancer patients heavily exposed to endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;67:111–116. doi: 10.1023/a:1010619225209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ellis MJ, Gao F, Dehdashti F, Jeffe DB, Marcom PK, Carey LA, et al. Lower-dose vs highdose oral estradiol therapy of hormone receptor-positive, aromatase inhibitor-resistant advanced breast cancer: a phase 2 randomized study. JAMA. 2009;302:774–780. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Howell A, Dodwell DJ, Anderson H, Redford J. Response after withdrawal of tamoxifen and progestogens in advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1992;3:611–617. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berthois Y, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Phenol red in tissue culture media is a weak estrogen: implications concerning the study of estrogen-responsive cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2496–2500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welshons WV, Jordan VC. Adaptation of estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells to low estrogen (phenol red-free) culture. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:1935–1939. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katzenellenbogen BS, Kendra KL, Norman MJ, Berthois Y. Proliferation, hormonal responsiveness, and estrogen receptor content of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells grown in the short-term and long-term absence of estrogens. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4355–4360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Masamura S, Santner SJ, Heitjan DF, Santen RJ. Estrogen deprivation causes estradiol hypersensitivity in human breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2918–2925. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yue W, Wang JP, Conaway M, Masamura S, Li Y, Santen RJ. Activation of the MAPK pathway enhances sensitivity of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to the mitogenic effect of estradiol. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3221–3229. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song RX, Mor G, Naftolin F, McPherson RA, Song J, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of long-term estrogen deprivation on apoptotic responses of breast cancer cells to 17beta-estradiol. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:714–723. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haddow A, Watkinson JM, Paterson E, Koller PC. Influence of synthetic oestrogens upon advanced malignant disease. BMJ. 1944;23:393–398. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4368.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jordan VC, Liu H, Dardes R. Re: Effect of long-term estrogen deprivation on apoptotic responses of breast cancer cells to 17 beta-estradiol and the two faces of Janus: sex steroids as mediators of both cell proliferation and cell death. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1173. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang SY, Wolf DM, Yingling JM, Chang C, Jordan VC. An estrogen receptor positive MCF-7 clone that is resistant to antiestrogens and estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;90:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90104-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pink JJ, Jiang SY, Fritsch M, Jordan VC. An estrogen-independent MCF-7 breast cancer cell line which contains a novel 80-kilodalton estrogen receptor-related protein. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2583–2590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lewis-Wambi JS, Kim HR, Wambi C, Patel R, Pyle JR, Klein-Szanto AJ, et al. Buthionine sulfoximine sensitizes antihormone-resistant human breast cancer cells to estrogen-induced apoptosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R104. doi: 10.1186/bcr2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis-Wambi JS, Swaby R, Kim H, Jordan VC. Potential of l-buthionine sulfoximine to enhance the apoptotic action of estradiol to reverse acquired antihormonal resistance in metastatic breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sweeney EE, Fan P, Jordan VC. Mechanisms underlying differential response to estrogen-induced apoptosis in long-term estrogen-deprived breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:1529–1538. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lewis JS, Osipo C, Meeke K, Jordan VC. Estrogen-induced apoptosis in a breast cancer model resistant to long-term estrogen withdrawal. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lewis JS, Meeke K, Osipo C, Ross EA, Kidawi N, Li T, et al. Intrinsic mechanism of estradiol-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells resistant to estrogen deprivation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1746–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ariazi EA, Cunliffe HE, Lewis-Wambi JS, Slifker MJ, Willis AL, Ramos P, et al. Estrogen induces apoptosis in estrogen deprivation-resistant breast cancer through stress responses as identified by global gene expression across time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18879–18886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115188108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Osipo C, Gajdos C, Liu H, Chen B, Jordan VC. Paradoxical action of fulvestrant in estradiol-induced regression of tamoxifen-stimulated breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1597–1608. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu H, Lee ES, Gajdos C, Pearce ST, Chen B, Osipo C, et al. Apoptotic action of 17betaestradiol in raloxifene-resistant MCF-7 cells in vitro and in vivo. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1586–1597. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Osipo C, Meeke K, Cheng D, Weichel A, Bertucci A, Liu H, et al. Role for HER2/neu and HER3 in fulvestrant-resistant breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Obiorah IE, Sengupta S, Curpan R, Jordan VC. Defining the conformation of the estrogen receptor complex that controls estrogen induced apoptosis in breast cancer. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:789–799. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Obiorah I, Sengupta S, Fan P, Jordan VC. Delayed triggering of oestrogen induced apoptosis that contrasts with rapid paclitaxel-induced breast cancer cell death. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1488–1496. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Obiorah I, Jordan VC. Scientific rationale for postmenopause delay in the use of conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women that causes reduction in breast cancer incidence and mortality. Menopause. 2013;20:372–382. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828865a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fan P, Griffith OL, Agboke FA, Anur P, Zou X, McDaniel RE, et al. c-Src modulates estrogen-induced stress and apoptosis in estrogen-deprived breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4510–4520. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fan P, McDaniel RE, Kim HR, Clagett D, Haddad B, Jordan VC. Modulating therapeutic effects of the c-Src inhibitor via oestrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in breast cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3488–3498. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fan P, Agboke FA, McDaniel RE, Sweeney EE, Zou X, Creswell K, et al. Inhibition of c- Src blocks oestrogen-induced apoptosis and restores oestrogen-stimulated growth in long-term oestrogen-deprived breast cancer cells. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balaburski GM, Dardes RC, Johnson M, Haddad B, Zhu F, Ross EA, et al. Raloxifene-stimulated experimental breast cancer with the paradoxical actions of estrogen to promote or prevent tumor growth: a unifying concept in anti-hormone resistance. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:387–398. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hutcheson IR, Knowlden JM, Madden TA, Barrow D, Gee JM, Wakeling AE, et al. Oestrogen receptor-mediated modulation of the EGFR/MAPK pathway in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81:81–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1025484908380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, Qin L, Tsimelzon A, Huang S, et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res. 2008;68:826–833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen: a most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:205–213. doi: 10.1038/nrd1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jordan VC, Obiorah I, Fan P, Kim HR, Ariazi E, Cunliffe H, et al. The St. Gallen Prize Lecture 2011: evolution of long-term adjuvant anti-hormone therapy: consequences and opportunities. Breast. 2011;20:S1–S11. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jordan VC. A century of deciphering the control mechanisms of sex steroid action in breast and prostate cancer: the origins of targeted therapy and chemoprevention. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1243–1254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]