Abstract

Purpose

This study examined whether: a) dose frequency of Milieu Communication Teaching (MCT) affects children's canonical syllabic communication, and b) the relation between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary is mediated by parental linguistic mapping in children with intellectual disabilities (ID).

Method

We drew on extant data from a recent differential treatment intensity study in which 63 toddlers with ID were randomly assigned to receive either five, 1 hour MCT sessions per week (i.e., daily treatment) or one, 1 hour MCT session per week (i.e., weekly treatment) for nine months. Children's early canonical syllabic communication was measured after three months of treatment and later spoken vocabulary was measured at post-treatment. Mid-point parental linguistic mapping was measured after 6 months of treatment.

Results

A moderate-sized effect in favor of daily treatment was observed on canonical syllabic communication. The significant relation between canonical syllabic communication and spoken vocabulary was partially mediated by linguistic mapping.

Conclusions

These results suggest that canonical syllabic communication may elicit parental linguistic mapping, which may in turn support spoken vocabulary development in children with ID. More frequent early intervention boosted canonical syllabic communication, which may jumpstart this transactional language-learning mechanism. Implications for theory, research, and practice are discussed.

Keywords: Milieu Communication Teaching, treatment intensity, intellectual disabilities, language, vocabulary, intervention

Children with intellectual disabilities (ID) present with extremely diverse developmental profiles and achieve variable outcomes that are most likely the result of differences in child and family characteristics, as well as in quantity and quality of early intervention (Guralnick, 2005). One area in which children with ID vary greatly is their ability to use spoken language to communicate (Hart, 1996; Rondal & Edwards, 1997). Explaining the variability in spoken language use of young children with ID not only improves our understanding of why these children are so different from one another, but also helps us determine how we can intervene to support optimal outcomes in this population.

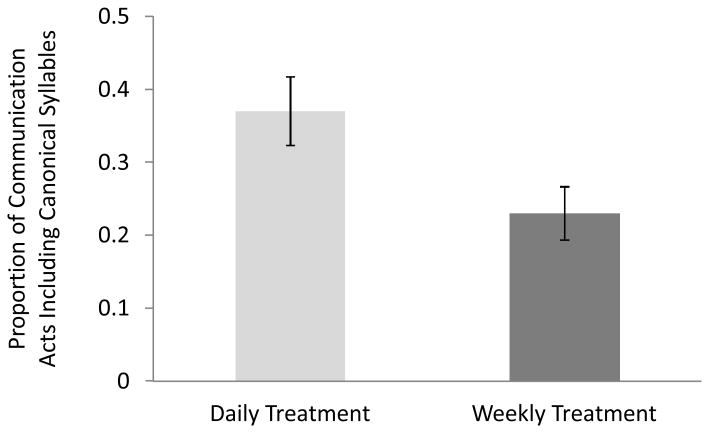

In this study, we use a transactional model to explain individual differences in the spoken vocabulary of toddlers with ID (McLean & Snyder-McLean, 1978; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). From this perspective, we assume that any complete account of variability in the development of spoken vocabulary in children with ID must consider both child and family variables and the complex ways in which they interact (Yoder & Warren, 2001). For example, several researchers have proposed that early prelinguistic child acts elicit parental responses, some of which provide a scaffold for subsequent linguistic development (Goldberg, 1977; Locke, 1996; McCune, 1992; Snyder-McLean, 1990). In this study, we test one specification of the transactional model that involves the parental response referred to as linguistic mapping. Linguistic mapping occurs when a parent responds to a child's prelinguistic communication act with words that reflect the child's meaning. We aimed to determine whether parental linguistic mapping partially or completely accounts for (i.e., mediates) the positive association between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary in toddlers with ID that has been observed in previous studies (Yoder & Warren, 2004; Yoder, Warren, & McCathren, 1998). In other words, we tested a statistical model that is compatible with the hypothesis that canonical syllabic communication “indirectly” impacts later spoken vocabulary through the elicitation of parental linguistic mapping. Additionally, we evaluated whether increasing the frequency of early intervention sessions boosts canonical syllabic communication and, therefore, more effectively jumpstarts this dynamic language learning mechanism. Refer to Figure 1 for an illustration of our proposed model.

Figure 1.

A transactional model of spoken vocabulary development. More frequent treatment may boost canonical syllabic communication, increasing the clarity of children's prelinguistic communication acts. Canonical syllabic communication may then elicit parental linguistic mapping, which provides a semantic and phonological basis for spoken vocabulary development in children with intellectual disabilities.

The Link between Early Canonical Syllabic Communication and Later Spoken Vocabulary

Canonical syllabic communication acts are intentional acts that serve a communication function and contain at least one canonical syllable (i.e., a consonant and vowel sequence produced with adult-like speech timing)(Yoder et al., 1998). Two previous studies have found that canonical syllabic communication accounts for variability in spoken vocabulary outcomes in young children with ID (Yoder & Warren, 2004; Yoder et al., 1998). Similar measures of vocalization complexity covary with spoken language outcomes of typically developing children (Menyuk, Liebergott, & Schultz, 1986; Stoel-Gammon, 1989; Watt, Wetherby, & Shumway, 2006; Wetherby, Cain, Yonclas, & Walker, 1988), as well as children with specific expressive language delays (Wetherby, Yonclas, & Bryan, 1989; Whitehurst, Smith, Fischel, Arnold, & Lonigan, 1991) and children with autism spectrum disorders (Plumb & Wetherby, 2013). Therefore, we expected to replicate the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary in our present sample of toddlers with ID.

The Correlation between Canonical Syllabic Communication and Parental Linguistic Mapping

In contrast, canonical syllabic communication has not previously been linked with parental linguistic mapping in young children with ID. However, we know that parents respond more frequently to typically developing infants when they perceive the infants to be intentionally communicating (Yoder & Munson, 1995). Adults are also more likely to provide a linguistic map in response to acts of children with ID when those acts are clearly communicative (Yoder, Warren, Kim, & Gazdag, 1994). Adults tend to view typically developing infants as more intentionally communicative or “really talking” when they produce syllabic vocalizations (Beaumont & Bloom, 1993), and they are more likely to provide a linguistic map in response to vocalizations that include canonical syllables (Gros-Louis, West, Goldstein, & King, 2006). Parents of children with ID may view canonical syllabic communication as “trying to talk” and, in turn, more frequently provide words for the presumed meaning of child communication acts through linguistic mapping.

The Relation between Parental Linguistic Mapping and Spoken Vocabulary

The specific association between parental linguistic mapping and later spoken vocabulary size also has not been established in children with ID. However, previous research involving typically developing infants has found that maternal responsivity and maternal linguistic input during the period of canonical babbling predict later spoken vocabulary (Goldin-Meadow, Goodrich, Sauer, & Iverson, 2007; Masur, 1982; Masur, Flynn, & Eichorst, 2005; Nicely, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 1999; Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, & Baumwell, 2001), as well as broader spoken language use (Nicely et al., 1999; Rollins, 2003; Rollins & Snow, 1998; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001). Additional studies have demonstrated associations between parents' linguistic responses (including expansion and interpretation of child communication acts) and subsequent spoken vocabulary size in toddlers with expressive language delays (Girolametto, Weitzman, Wiigs, & Pearce, 1999) and young children with autism spectrum disorders (McDuffie & Yoder, 2010).

Prior work has found that various indices of parental responsivity and parental input during the pre linguistic stage also predict broader spoken language outcomes in children with ID. For example, Yoder and Warren (2004) reported that parent responses to child communication (including, but not limited to, parental linguistic mapping) accounted for individual differences in later spoken language use in children with ID, when controlling for initial language level. In another sample of prelinguistic children with ID, Yoder, McCathren, Warren, & Watson (2001) found that the number of parental linguistic mapping responses to intentional child communication (including, but not limited to, canonical syllabic communication) predicted later spoken language use and understanding, even after controlling for initial language level. In this second study, Yoder and Warren) found that parental responses predicted spoken language use and understanding and mediated the relation between intentional prelinguistic communication and subsequent spoken language use and understanding. Thus, evidence from the extant literature suggests that parental linguistic mapping may mediate the relation between canonical syllabic communication and subsequent spoken vocabulary in young children with ID. However, this mediation model has not been previously tested.

The Possible Effect of Treatment Dose Frequency on Canonical Syllabic Communication

Given that the production of canonical syllables has been consistently linked with later spoken vocabulary in children with ID (possibly because this type of vocalization elicits linguistic mapping from parents), it is critical to determine whether canonical syllabic communication is malleable with treatment. The treatment employed in our study was Milieu Communication Teaching (MCT; Fey et al., 2006). In children not yet talking, MCT aims to systematically improve the frequency, complexity, and clarity of children's communication, starting with foundational prelinguistic skills, such as vocalizations, eye gaze, and gestures. MCT has been found to produce moderate sized effects on prelinguistic skill (i.e., rate of intentional communication) in young children with ID when offered at a relatively low dose frequency of one hour per week (Fey et al., 2006). However, recent studies suggest that the effects of MCT may be enhanced at a higher dose frequency - at least for some children with ID (Fey, Yoder, Warren, & Bredin-Oja, 2013; Yoder, Woynaroski, Fey, & Warren, in press). Thus, it is possible that more frequent MCT may boost canonical syllabic communication in young children with ID. Woynaroski, Fey, Warren, and Yoder (in press) provide an in-depth review of previous findings for MCT treatment and a summary of treatment intensity effects observed across a broader range of interventions and populations.

In the present differential treatment intensity study, prelinguistic toddlers with ID were randomly assigned to receive MCT at a dose frequency of either one hour per week (i.e., weekly treatment) or five hours per week (i.e., daily treatment). A differential treatment intensity study systematically compares the effects of a single type of treatment delivered at different intensities (Warren, Fey, & Yoder, 2007). This study contrasts different MCT dose frequencies, as opposed to contrasting a treatment condition with a non-treatment or business-as-usual control condition. As such, it is a very conservative test of whether canonical syllabic communication is responsive to our intervention.

Summary

In summary, there is evidence that canonical syllabic communication is correlated with later spoken vocabulary in young children with ID. However, we do not know whether environmental manipulations, such as frequency of communication intervention, can increase canonical syllabic communication in young children with ID. Additionally, there is evidence that advanced prelinguistic vocalizations are likely to elicit parental responses and that parental responses, such as linguistic mapping, are associated with subsequent spoken language. However, researchers have not determined whether parental linguistic mapping mediates the relation between canonical syllabic communication and subsequent spoken vocabulary in children with ID.

Research Questions

Thus, we addressed the following two research questions:

Does daily MCT treatment increase canonical syllabic communication more than weekly MCT treatment in toddlers with ID?

Is the association between early child canonical syllabic communication and later child spoken vocabulary mediated by parental linguistic mapping?

Methods

Overview of Study Design

To answer these research questions, we drew on an extant database from a recent differential treatment intensity study in which pre linguistic toddlers with ID were randomly assigned to receive either daily (five, 1 hour sessions per week) or weekly (one, 1 hour session per week) MCT over a period of nine months (Fey et al., 2013; Yoder et al., in press). Parents of all children participated in a parent training program over the first three months of the treatment period, regardless of their child's assigned treatment dose frequency. A broad range of child communication skills and parent utterance types were assessed at entry to the study (Time 1), following three months of treatment (Time 2), following six months of treatment (Time 3), and after completion of the entire nine month treatment protocol (Time 4). The data of interest in the current report included: a) child canonical syllabic communication at Time 2, b) parental linguistic mapping at Time 3, and c) child spoken vocabulary at Time 4. Recruitment and study procedures were conducted in accordance with the approval of the Vanderbilt University and University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Participants

Participants included 63 parent-child dyads recruited at Vanderbilt University and the University of Kansas Medical Center. Inclusion criteria for children were: a) chronological age between 18 and 27 months; b) expressive vocabulary less than or equal to 20 signed or spoken words excluding animal sounds, caregiver names, and routinized games and activities as reported by a primary caregiver on the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: Words and Gestures vocabulary checklist (MB-CDI; Fenson et al., 2003); c) Mental Development Index between 55 and 75 on the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development: 3rd Edition (Bayley-III); d) score less than or equal to 2.75 on the Screening Tool for Autism in 2-year olds (STAT) confirming low-risk for autism; e) normal hearing in at least one ear confirmed by sound field hearing screening; f) normal or corrected to normal vision; g) sufficient motor skill to sit unsupported and interact with an interventionist; h) primarily English-speaking household; and i) completion of at least two-thirds of the prescribed treatment protocol.

A computer program using a random number generator was utilized to assign children to either daily or weekly MCT. The final sample comprised 33 children assigned to daily intervention and 30 children assigned to weekly intervention. Parents of children with ID reported achieving a mean formal education level of three to four years of college.

Pre-treatment group comparisons

As indicated in Table 1, daily and weekly treatment groups were non-significantly different on several important variables, including canonical syllabic communication and expressive spoken vocabulary, at entry to the study. Group comparisons on 34 additional variables of interest confirmed that randomization successfully produced treatment groups with similar characteristics at entrance to the study, p > .08 (d < |.45|) (Fey et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Pre-experimental Characteristics by Dose Frequency Group.

| Pre-treatment characteristic | Daily M(SD) | Weekly M(SD) | t(61) | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronological age in months | 21.83 (2.71) | 22.95 (3.33) | -1.47 | 0.15 | -0.37 |

| Bayley III mental age in months | 12.61 (2.08) | 12.47 (2.15) | 0.26 | 0.79 | 0.07 |

| Bayley III Cognitive Composite | 66.06 (6.82) | 64.67 (6.69) | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.21 |

| Canonical syllabic communication | 0.21 (0.20) | 0.15 (0.14) | 1.45 | 0.15 | 0.34 |

| Number of words spoken on MB-CDI | 1.15 (1.39) | 0.97 (1.50) | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.12 |

Daily = Five, 1 hour sessions per week. Weekly = One, 1 hour session per week.

Participation in non-project treatment

Parent reports indicated that most children enrolled in the project were participating in early intervention programs that involved speech-language pathology services over the course of the study; however, daily and weekly treatment groups did not differ in the mean number of hours spent in non-experimental interventions (Daily M = 3.2 hours/month, SD = 2.4; Weekly M = 2.7 hours/month, SD = 2.4), t(62) = 1.5, p > .13. The specific treatment type and targets of non-project speech-language services are unknown.

Treatment

Parent-child dyads received MCT, comprising Prelinguistic Milieu Teaching (Yoder & Warren, 1998), Milieu Language Teaching (Hancock & Kaiser, 2006), and Responsivity Education (Yoder & Warren, 2002). Prelinguistic Milieu Teaching is a direct child intervention approach that employs principles of incidental learning to teach pivotal prelinguistic skills, such as vocalizations, gestures, and coordinated attention, that set the stage for language learning (Yoder & Warren, 1999, 1999b). Milieu Language Teaching is a direct child intervention approach (Hancock & Kaiser, 2006) that is used to directly target linguistic skills once the children have surpassed an empirically derived threshold for mastery of prelinguistic skills (i.e., more than 2 intentional communication acts per minute or more than 5 functional words or signs; Fey et al., 2006; Yoder & Warren, 2002). Research staff delivered direct child intervention components of MCT in homes or child care centers according to parent preference.

Responsivity Education is a parent training component of MCT that is intended to increase parental responsivity to child communication to foster growth and generalization across settings, interaction partners, activities, materials, and interaction styles (Yoder & Warren, 1999, 2001, 2001b). Responsivity Education content is based on the Hanen Centre program, It Takes Two to Talk (Pepper & Weitzman, 2004). This program strives to impart parental strategies, such as observing the child and following the child's lead, that scaffold communication and language development in everyday settings. One component of Responsivity Education specifically involves teaching the parent to use linguistic mapping. Primary caregivers completed nine 1 hour sessions of Responsivity Education. Individual sessions with a clinician were conducted in the participants' homes approximately once per week over the first three months of the intervention period.

A more detailed description of MCT is provided in Fey et al. (2013) and Warren et al. (2008). Interventionists were para-professionals who were supervised by licensed and certified speech-language pathologists at the University of Kansas (5 interventionists and 2 supervisors) and Vanderbilt University (3 interventionists and 1 supervisor) sites. All interventionists had baccalaureate degrees in a relevant field, such as psychology or special education, and previous experience with children with special needs. Details of interventionist training have been described in Fey et al. (2013).

Fidelity of dose, dose frequency, and treatment duration

Thirty minutes of one 60-minute treatment session per child per month were coded from media files by the supervisor at the site opposite the clinician whose session was being evaluated. As such, the supervisor at the University of Kansas coded 30 minutes of a randomly selected treatment session for each child enrolled at Vanderbilt University each month, and the supervisor at Vanderbilt University coded 30 minutes of a randomly selected treatment session for each child enrolled at the University of Kansas each month. Thus, treatment fidelity was estimated on a random sample of 5% of sessions for daily treatment group and 23% of sessions for the weekly treatment group. Absolute agreement intra-class correlation coefficients ranged from .91 to .98 for the number of correctly implemented teaching episodes. The average rate of correctly administered teaching episodes per minute (M = 1.10, SD = .30) did not differ across groups, F(1, 60) = 1.69, p >.20. However, children in the daily treatment group (M = 149.3, SD = 12.17) experienced, on average, 4.19 times more cumulative teaching episodes than the weekly treatment group (M = 35.67 SD = 2.31), F(1, 60)= 2609.23, p < .001.

Data Collection

As we indicated previously, data on child communication and spoken language, as well as parental responsivity, was assessed at entry to the study (Time 1), following three months of treatment (Time 2), following six months of treatment (Time 3), and after completion of the entire nine month treatment protocol (Time 4). Child canonical syllabic communication at Time 2 was measured in three sampling contexts that varied in the level of structure provided and in the familiarity of the examiner: a) the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (CSBS; Wetherby & Prizant, 1993), b) an examiner-child semi-structured free play (ECSS), c) and a parent-child free play (PCFP). Parental linguistic mapping at Time 3 was measured in the context of the PCFP. Child spoken vocabulary at Time 4 was measured via the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: Words and Gestures vocabulary checklist (MB-CDI; Fenson et al., 2003).

CSBS

Of the three communication sampling contexts included in the Time 2 evaluations, the CSBS was the most structured. The CSBS is a standardized assessment of communication skill for children in the prelinguistic and early linguistic stages of language acquisition. The examiner in this context was unfamiliar to the child outside of the assessment context and unaware of the child's treatment condition. Two CSBS components composed this sample: a) Communicative Temptations, and b) Book Sharing. In the Communicative Temptations procedure, an unfamiliar examiner presented a series of eight activities, including action-based toys, edibles, and social games, and provided planned temptations and prompts to entice the child to communicate. In the Book Sharing component, the examiner presented a series of picture books, allowed the child to select a few books of interest, and followed the child's lead to support spontaneous communication acts. The CSBS sample varied in duration across participants, ranging from 15-20 minutes.

ECSS

The ECSS served as a less structured sampling context relative to the CSBS for measurement of canonical syllabic communication. The examiner, who was unfamiliar to the child outside the assessment context and blind to the child's treatment condition, presented the participant with three standard sets of toys in succession, according to the child's degree of interest and engagement with each set. The examiner transitioned between toy sets: a) when the child appeared to become disinterested in a toy set; b) when a child directly expressed a desire for a different set; or c) when the child appeared distressed. The examiner followed the child's lead and provided limited scaffolding for communication and play behaviors, serving primarily as a respondent to child initiations. However, direct prompts for child communication and actions were not provided. The total duration of the ECSS was 15 minutes.

PCFP

The PCFP sampling context was the least structured of the communication samples, but the adult interaction partner (a parent or primary caregiver) was familiar to the child. Additionally, the parent was aware of the frequency of the child's MCT sessions. The PCFP involved 10 minutes of free play and 5 minutes of unstructured book sharing between each parent-child dyad. In the free play component, the parents were provided with two sets of toys. They were instructed that they should offer their child a choice of the two play sets and proceed to play as they would typically play at home. They were also told that they could switch to the second toy set if their child became disinterested in the first set. Following the free play, the examiner provided the parent with three board books. Parents were told that they should “look at” the books with their child for 5 minutes, but they were not directly instructed to read the books. Parents were not told to respond to communication acts in any particular way. However, parents' participation in Responsivity Education over the first three months of the study could certainly have impacted the quantity and quality of their responses to child communication acts.

MB-CDI

Parents were asked to check items on the MB-CDI vocabulary list to indicate whether their child either “understands” or “understands and signs (does not say)” or “understands and says (may also sign)” early lexical items in semantic categories, such as actions, household items, and animals. Parents completed the MB-CDI checklists in the clinic and reviewed responses with a research staff member during the Time 4 evaluation visit.

Data Reduction

Communication sample coding

The three communication samples were transcribed and coded by personnel who completed a training protocol including: a) a review of the coding manual; b) practice coding communication samples; and c) coding of three consecutive samples with 80% accuracy or higher. Each communication sample was coded by a primary coder, and 20% of the samples were randomly selected for independent transcription and analysis by a secondary coder. A coding supervisor reviewed primary and secondary transcripts to identify any potential threats to reliability and to resolve any discrepancies. The coding supervisor regularly corresponded with both primary and secondary coders regarding any concerns.

All three communication samples were coded for intentional child communication acts and the production of canonical syllables at Time 2. Intentional child communication acts were defined as: a) vocal or gestural acts combined with coordinated attention to object and person, or b) conventional gestures (e.g., showing, pointing) with attention to adult,or c) symbolic forms (i.e., words, sign language). Canonical syllables were defined as vocalizations in which a rapid transition occurred between vowel-like and consonant-like speech sounds. At Time 3, PCFP samples were coded for intentional child communication acts (as defined above) and instances of parental linguistic mapping. Linguistic mapping was defined as a parental utterance that put into words a reasonable guess at the presumed meaning of an immediately preceding child communication act.

Dependent variables

Canonical syllabic communication at Time 2 was defined as the proportion of intentional communication acts that included canonical syllables. To derive this dependent variable, the total number of Time 2 canonical syllabic communication acts summed across all three sampling contexts was divided by the total number of intentional communication acts across the communication sampling contexts. These counts were summed over the three contexts to increase the likelihood of obtaining a stable, and thus valid, estimate of the children's canonical syllabic communication (Sandbank & Yoder, in progress). The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) estimate of the reliability of inter-observer agreement, based on a random sample of 17% of the total sets of the three communication sampling sessions and calculated in a way that included both unitizing errors (i.e., errors in identifying the presence of a communication act) and classifying errors (i.e., errors in identifying whether the act has a canonical syllable), was .97.

Parental linguistic mapping at Time 3 was defined as the raw number of parental linguistic mapping utterances provided in response to all intentional child communication acts observed during the Time 3 PCFP. The ICC for parental linguistic mapping at Time 3, based on a random sample of 16% of the PCFP sessions, was .99.

Spoken vocabulary at Time 4 was defined as the raw number of words that parents indicated their child “understands and says (may also sign)”on the MB-CDI with a few specified exceptions. Our principle long-term goal was to facilitate children's use of spoken words to promote grammatical development. To ensure that we were measuring gains in vocabulary with which children could eventually build grammatical utterances, sound effects, animal sounds (e.g., “meow” or “quack quack”), caregiver names (e.g., “daddy” and “papa”), and items associated with routinized games and activities (e.g., “please” or “hi”) were not counted.

Data Analysis

Test of treatment intensity effect

We evaluated whether daily treatment increased canonical syllabic communication more than weekly treatment in toddlers with ID by conducting an independent samples t-test to compare the means of daily versus weekly treatment groups at Time 2 (i.e., following three months of treatment).

Evaluation of proposed mediation

We evaluated whether the relation between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary was mediated by mid-point parental linguistic mapping by statistically testing the significance of the indirect effect of canonical syllabic communication on spoken vocabulary through parental linguistic mapping (Hayes, 2009).In this study, the two components of the indirect effect are: a) the relation between early canonical syllabic communication and mid-point parental linguistic mapping, and b) the relation between mid-point parental linguistic mapping and later spoken vocabulary controlling for early canonical syllabic communication. It has been shown that the product of the unstandardized coefficients for these two relations represents the magnitude of the combined indirect effect (Hayes, 2009). An unstandardized regression coefficient indicates the change in the criterion variable (e.g., the number of words produced at Time 4) per change of one raw score unit in the predictor (e.g., the parents' use of linguistic mapping at Time 3) controlling for any covariates (e.g., the children's use of canonical syllabic communication at Time 2). The indirect effect is deemed statistically significant when the 95% confidence interval for the product of the unstandardized coefficients representing the two components of the indirect effect does not include 0. When the confidence interval does not include zero, it can be concluded, with 95% certainty, that the combined effect of the two components of the indirect effect is greater than zero in the population.

A significant indirect effect could partially or completely mediate the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary. In partial mediation, the size of the correlation between canonical syllable production and spoken vocabulary would be significantly reduced, but still statistically significant, after controlling for linguistic mapping. In complete mediation, this correlation would be rendered statistically non-significant when parental linguistic mapping is controlled (Hayes, 2009). Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors were estimated for each component of the indirect effect via linear regression in SPSS, and the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was computed using the PRODCLIN software program (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007).

Results

Does Treatment Dose Frequency Affect Canonical Syllabic Communication?

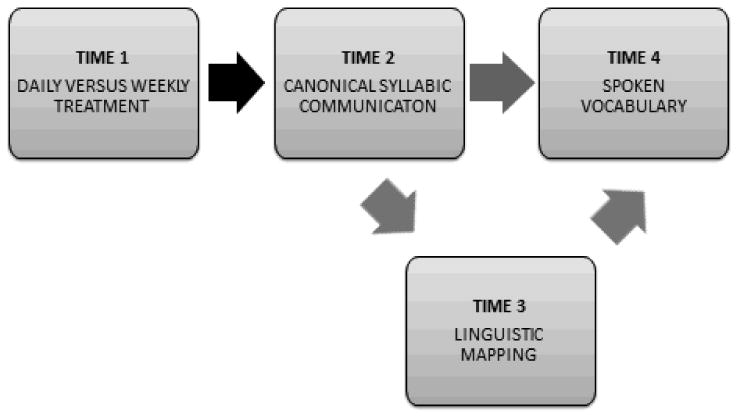

Analyses confirmed that daily treatment did increase canonical syllabic communication more than weekly treatment in our sample of toddlers with ID, t(61) = 2.34, p = .02. After three months of treatment, participants produced a higher proportion of communication acts including canonical syllables if they had received five, 1 hour MCT sessions per week (M = .37 , SD = .27) than if they received only one, 1 hour MCT session per week (M = .23 , SD = .20).This effect was moderate in magnitude (g = .58)(Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of treatment dose frequency on canonical syllabic communication. Daily treatment (five, 1 hour sessions per week) increased canonical syllabic communication more than weekly treatment (one, 1 hour session per week) (p < .05). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Does Parental Linguistic Mapping Mediate the Relation Between Early Canonical Syllabic Communication and Later Spoken Vocabulary?

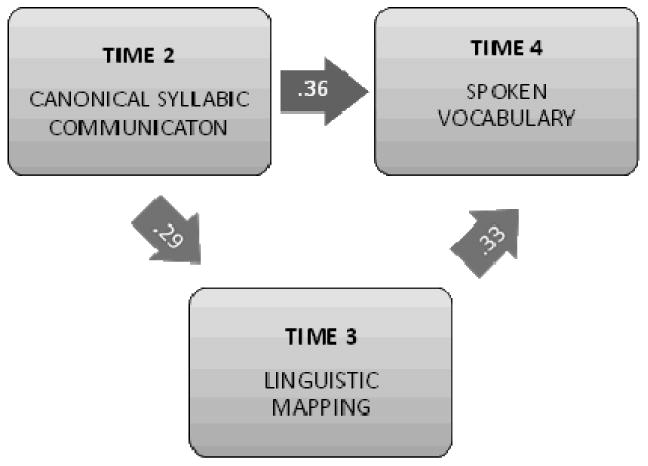

As expected, canonical syllabic communication at Time 2 was positively associated with child spoken vocabulary at Time 4 (r = .52, p <.001). Additionally, canonical syllabic communication at Time 2 was positively correlated with parental linguistic mapping at Time 3 (r = .29, p < .05). Furthermore, parental linguistic mapping at Time 3 was positively associated with spoken vocabulary at Time 4, controlling for Time 2 canonical syllabic communication (r = .33, p = .004). As such, both components of the indirect effect were statistically significant.

The confidence interval for the product of the un standardized coefficients of the two components of the indirect effect (.26) did not include 0, 95% CI [.005, .56]. Accordingly, the strength of the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary was significantly reduced when mid-point parental linguistic mapping was controlled (i.e., reduced from r = .52 to part r = .40, p <.001). However, early canonical syllabic communication continued to significantly predict later spoken vocabulary even after statistically controlling for parental linguistic mapping. Therefore, the association between early child canonical syllabic communication and later child spoken vocabulary was only partially mediated by parental linguistic mapping (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Support for a transactional model of spoken vocabulary variation in toddlers with intellectual disabilities. The association between early child canonical syllabic communication and later child spoken vocabulary was partially mediated by parental linguistic mapping. Coefficients included in the figure are standardized regression coefficients. All p values are < .05.

However, a “partial” mediation effect does not necessarily suggest a “small” mediation effect. The magnitude of a mediation effect may be indexed by kappa-squared (k2), which quantifies the proportion of the indirect effect relative to the maximum possible indirect effect that could have been obtained, considering the scales and sample variations of the variables involved (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). Values for k2 range from 0 to 1, wherein 0 indicates that there is no indirect effect and 1 indicates that the indirect effect is as large as possible given the data. The values for k2 may be interpreted according to Cohen's guidelines for squared correlation coefficients, whereby .01 indicates a small effect, .09 indicates a medium effect, and .25 indicates a large effect (Cohen, 1988). According to these criteria, our partially mediated effect is moderate in magnitude (k2 = .11).

Discussion

This study drew on extant data from a recent differential treatment intensity study to investigate whether dose frequency of MCT differentially affected canonical syllabic communication and to test whether parental linguistic mapping mediated the relationship between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary in young children with ID. The results demonstrated that daily treatment increased canonical syllabic communication more than weekly treatment did in toddlers with ID. Findings also confirmed that the relation between early child canonical syllabic communication and later child spoken vocabulary was partially mediated by parental linguistic mapping. These results have important implications for theory, research, and practice.

Effect of Dose Frequency on Canonical Syllabic Communication

MCT has previously been shown to produce unconditional effects of moderate size on other prelinguistic skills (i.e., rate of intentional prelinguistic communication) in young children with ID when provided at a relatively low dose frequency (approximately one hour per week) over six months (Fey et al., 2006). Recent studies have found enhanced effects for more frequent MCT in some children with ID after a more extended total duration of treatment (Fey et al., 2013; Yoder et al., in press). For example, children with high object interest (Fey et al., 2013) and children with Down syndrome (Yoder et al., in press) had better spoken vocabulary outcomes after nine months of treatment if they had received five, 1 hour MCT sessions per week than if they had received only one, 1 hour MCT session per week. The present result extends these findings by demonstrating that the four-fold increase in MCT dose frequency that we achieved yielded an unconditional, medium-sized effect on children's canonical syllabic communication after only three months of treatment.

Empirical Support for a Transactional Model of Spoken Vocabulary in Children with ID

Our findings indicate further that increased canonical syllabic communication is associated with increased parental linguistic mapping and that this increased parental linguistic mapping is linked with larger spoken vocabularies in children with ID. Our statistical test of the indirect effect confirmed that increased parental linguistic mapping partially accounts for the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary that has been observed in prior work (Yoder & Warren, 2004; Yoder et al., 1998). Yoder and Warren (1999) previously found that the relation between early intentional communication and later spoken language is mediated by maternal responsivity. Our partially mediated association provides additional empirical support for the transactional model of language acquisition in young children with ID (McLean & Snyder-McLean, 1978; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975; Yoder & Warren, 1999). These findings collectively suggest that clinicians may enhance their support of spoken language development in children with ID by increasing parental responsivity, and linguistic mapping in particular, in addition to directly targeting child skills.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our conclusion is mitigated by one important detail. Over the first three months of this study, all parents participated in Responsivity Education sessions, in which increased use of linguistic mapping was a primary objective. It is unclear whether such training had an effect on the amount of linguistic mapping provided by parents because dose frequency groups completed the same parent training protocol and this study did not include a control group that did not receive Responsivity Education. How ever, we know that parents in both dose frequency groups significantly increased their use of linguistic mapping from Time 1 to Time 2 and from Time 2 to Time 3 and that the frequency of parental linguistic mapping was non-significantly different between dose frequency groups for each time point (Fey et al., 2013). Gains for both groups may have been related, in part, to Responsivity Education. Thus, at present we can conclude that parental linguistic mapping partially mediates the relation between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary when parents have received some education in responsive strategy use. However, we cannot decisively say that this mediation relation will “hold up” or generalize when parents have not been trained to respond to their children's communication acts using strategies such as linguistic mapping. As such, the external validity of the mediated relation that we observed may be limited some what. Future studies may seek to replicate these relationships in parents of children with ID who have not received Responsivity Education.

Additional work is also needed to identify other factors that may account for the association between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary. Parental linguistic mapping only partially mediates the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later word use, and thus does not fully account for this correlation. That is, explanations other than parental linguistic mapping contribute to the relation between canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary. Several other child factors, including motor skill and/or the accuracy of phonological representations, are possible candidates. Other parent factors could contribute to this replicated correlation as well.

Finally, although the assumption of temporal precedence was met for the mediation components of the current design, all correlational mediation models are subject to third variable explanations. Although these “third variables” would have to be correlated with all three variables of our mediation model (i.e., child canonical syllabic communication, parental linguistic mapping, and child spoken vocabulary) to account for the mediation relation that we report, it is possible that they do exist. Thus, we cannot yet confidently conclude that canonical syllabic communication elicits parental linguistic mapping. Nor can we confidently conclude that parental linguistic mapping facilitates spoken vocabulary. These causal inferences can only be tested in experiments specifically designed to test the causality of the relations while controlling for alternative explanations. In contrast, we can conclude that the greater dose frequency of MCT had a causal influence on canonical syllabic communication. To test the dose frequency effect, we used a design with strong internal validity, including many important controls (e.g., blind assessors, blind coders, low attrition, high fidelity of treatment, equal non-project treatment attendance).

Conclusion

In summary, we found that boosting the dose frequency of early communication intervention can increase canonical syllabic communication in toddlers with ID, at least when parents have received training that directly targets increased linguistic mapping of child communication acts. This effect was moderate in magnitude (g = .58).Mediation analyses confirmed that child canonical syllabic communication may have elicited increased parental linguistic responses that, in turn, may have facilitated subsequent spoken vocabulary development in our sample. However, parents' linguistic mapping only partially accounts for the association between early canonical syllabic communication and later spoken vocabulary in young children with ID. As such, additional work is necessary to determine what other factors play a role in this replicated relation. Nonetheless, these results suggest that a transactional model, considering both child and parent variables, provides a useful framework for considering why children with ID are so heterogeneous in their ability to use spoken words to communicate. Furthermore, these findings add to the literature suggesting that treatment targeting both child communication and parental responsivity supports more favorable spoken language outcomes in children with ID.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant R01DC007660 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Center Grant P30 NICHD HD 002528 from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development, and grant H325D080075 from the U.S. Department of Education. The authors acknowledge the significant contributions of Jayne Brandel, Shelley Bredin-Oja, Catherine Bush, Debby Daniels, Elizabeth Gardner, Nicole Thompson and Peggy Waggoner.

Contributor Information

Tiffany Woynaroski, Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University.

Paul Yoder, Special Education Department, Vanderbilt University.

Marc E. Fey, Hearing and Speech Department, University of Kansas Medical Center

Steven F. Warren, Institute for Life Span Studies, University of Kansas

References

- Beaumont SL, Bloom K. Adults' attributions of intentionality to vocalizing infants. First Language. 1993;13(38, Pt 2):235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciencies. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale P, Reznick J, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, Reilly J. MacArthur communicative development inventories: User's guide and technical manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fey ME, Warren SF, Brady N, Finestack LH, Bredin-Oja SL, Fairchild M, Yoder PJ. Early effects of responsivity education/prelinguistic milieu teaching for children with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2006;49(3):526–547. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/039). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fey ME, Yoder PJ, Warren SF, Bredin-Oja S. Is more better? Milieu communication teaching in toddlers with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2013;56(2):679–693. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0081). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girolametto L, Weitzman E, Wiigs M, Pearce PS. The relationship between maternal language measures and language development in toddlers with expressive vocabulary delays. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 1999;8(4):364–374. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S. Social competence in infancy: A model of parent-infant interaction. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1977;23:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Goodrich W, Sauer E, Iverson J. Young children use their hands to tell their mothers what to say. Developmental Science. 2007;10(6):778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis J, West MJ, Goldstein MH, King AP. Mothers provide differential feedback to infants' prelinguistic sounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30(6):509–516. doi: 10.1177/0165025406071914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ. Early intervention for children with intellectual disabilities: current knowledge and future prospects. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2005;18(4):313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock TB, Kaiser AP. Enhanced milieu teaching. In: McCauley RJ, Fey ME, editors. Treatment of language disorders in children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2006. pp. 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B. The initial growth of expressive vocabulary among children with Down Syndrome. Journal of Early Intervention. 1996;20(3):211–221. doi: 10.1177/105381519602000305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JL. Why do infants begin to talk? Language as an unintended consequence. Journal of Child Language. 1996;23(2):251–268. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900008783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur E. Mothers' responses to infants' object-related gestures: influences on lexical development. Journal of Child Language. 1982;9(01):23–30. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur E, Flynn V, Eichorst D. Maternal responsive and directive behaviours and utterances as predictors of children's lexical development. Journal of Child Language. 2005;32(1):63–91. doi: 10.1017/S0305000904006634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune L. First words: A dynamic systems view. In: Ferguson CA, Menn L, Stoel-Gammon C, editors. Phonological Development: Models, research, implications. Timonium, MD: York Press; 1992. pp. 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie AS, Yoder PJ. Types of parent verbal responsiveness that predict language in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53(4):1026–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J, Snyder-McLean L. A transactional approach to early language training. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Menyuk P, Liebergott J, Schultz M. Predicting phonological development. In: Lindstrom B, Zetterstrom R, editors. Precursors of early speech. New York: Stockton Press; 1986. pp. 70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nicely P, Tamis-LeMonda C, Bornstein M. Mothers' attuned responses to infant affect expressivity promote earlier achievement of language milestones. Infant Behavior & Development. 1999;22(4):557–568. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper J, Weitzman E. It takes two to talk. Toronto: The Hanen Centre; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Plumb A, Wetherby A. Vocalization development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2013;56(2):721–734. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0104). doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0104)1092-4388_2012_11-0104 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. doi: 10.1037/a00226582011-07788-001 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins P. Caregivers' contingent comments to 9-month-old infants: Relationships with later language. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24(2):221–234. doi: 10.1037/0012 -1649.27.2.236. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins P, Snow C. Shared attention and grammatical development in typical children and children with autism. Journal of Child Language. 1998;25(3):653–673. doi: 10.1017/s0305000998003596. doi: 10.1037/0012 -1649.27.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondal JA, Edwards S. Language in mental retardation. Philadelphia, PA: Whurr Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A, Chandler M. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. In: Horowitz M, Hetherington M, Scarr-Salapatek S, Siegel G, editors. Review of child development research. Chicago, IL: University Park Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sandbank M, Yoder PJ. Measuring representative communication in 3-year-olds with intellectual disabilities (in progress) [Google Scholar]

- Snyder-McLean L. Communication development in the first two years: A transactional process. Zero to Three. 1990:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C. Prespeech and early speech development of two late talkers. First Language. 1989;9(26):207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda C, Bornstein M, Baumwell L. Maternal responsiveness and children's achievement of language milestones. Child Development. 2001;72(3):748–767. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SF, Fey ME, Finestack LH, Brady NC, Bredin-Oja SL, Fleming KK. A randomized trial of longitudinal effects of low-intensity responsivity education/prelinguistic milieu teaching. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2008;51(2):451–470. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SF, Fey ME, Yoder PJ. Differential treatment intensity research: a missing link to creating optimally effective communication interventions. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabililities Research Reviews. 2007;13(1):70–77. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt N, Wetherby A, Shumway S. Prelinguistic predictors of language outcome at 3 years of age. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49(6):1224–1237. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/088). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A, Cain D, Yonclas D, Walker V. Analysis of intentional communication of normal children from the prelinguistic to the multiword stage. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1988;31(2):240–252. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3102.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A, Prizant BM. Communication and symbolic behavior scales- normed edition. Balitmore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby A, Yonclas D, Bryan A. Communicative profiles of preschool children with handicaps: Implications for early identification. Journal of Speech & Hearing Disorders. 1989;54(2):148–158. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5402.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Smith M, Fischel JE, Arnold DS, Lonigan CJ. The continuity of babble and speech in children with specific expressive language delay. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1991;34(5):1121–1129. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3405.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woynaroski T, Fey M, Warren S, Yoder P. Prelinguistic communication intervention for young children with intellectual disabilities: a focus on treatment intensity. In: Romski M, Sevcik RA, editors. Examining the science and practice of communication interventions for individuals with severe disabilities. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, McCathren RB, Warren SF, Watson A. Important distinctions in measuring maternal responses to communication in prelinguistic children with disabilities. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2001;22(3):135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Munson LJ. The social correlates of co-ordinated attention to adult and objects in mother-infant interaction. First Language. 1995;15(44):219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Maternal responsivity predicts the prelinguistic communication intervention that facilitates generalized intentional communication. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 1998;41(5):1207–1219. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4105.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Maternal responsivity mediates the relationship between prelinguistic intentional communication and later language. Journal of Early Intervention. 1999;22(2):126–136. doi: 10.1177/105381519902200205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Facilitating self-initiated proto-declaratives and proto-imperatives in prelinguistic children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Early Intervention. 1999b;22(4):337–354. doi: 10.1177/105381519902200408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Intentional communication elicits language-facilitating maternal responses in dyads with children who have developmental disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2001;106(4):327–335. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0327:icelfm>2.0co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Relative treatment effects of two prelinguistic communication interventions on language development in toddlers with developmental delays vary by maternal characteristics. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2001b;44(1):224–237. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Effects of prelinguistic milieu teaching and parent responsivity education on dyads involving children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2002;45(6):1158–1174. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/094). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF. Early predictors of language in children with and without Down Syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;109(4):285–300. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<285:epolic>2.0co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF, Kim K, Gazdag GE. Facilitating prelinguistic communication skills in young children with developmental delay: II. Systematic replication and extension. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1994;37(4):841–851. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Warren SF, McCathren RB. Determining spoken language prognosis in children with developmental disabilities. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 1998;7(4):77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Woynaroski T, Fey M, Warren S. Effects of dose frequency of early communication intervention in young children with and without Down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.1.17. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]