Introduction

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is an extremely rare autosomal recessive primary immunodeficiency disease. The first case was reported in 1943. Since its first description, around 200 cases have been reported worldwide [1] and about 10 cases have been reported from India [2]. CHS is characterized by partial ocular and cutaneous albinism, increased susceptibility to pyogenic infections, the presence of large lysosomal-like organelles in most granule-containing cells and a bleeding tendency. Other clinical features include silvery hair, photophobia, horizontal and rotatory nystagmus and hepatosplenomegaly. Definitive diagnosis can only be made when the pathognomic abnormal large granules are noted in the leucocytes and other granule-containing cells [3].

Due to the rarity of the condition and the characteristic clinical and hematological findings, we are hereby reporting a case of Chediak-Higashi syndrome.

Case Report

A 2 years old male child presented with fever and pain abdomen for 9 days. There was history of loose watery stools for 2 days, increased frequency of micturition and 1 kg weight loss over last 9 days. Past history revealed similar episodes occurring almost every one to 2 months and each episode lasting 4–5 days ever since birth and history of post vaccine abscess right thigh at 8 months of age. There were silver grey hair and white spots on face since 2 months of age increasing to present stage by 5 months. The child weighed 9,700 g (3rd centile) and length of 84 cm (between 10th and 25th centile). On examination, there were silver grey hair (Fig. 1), patchy alopecia, hypopigmentation in peri-oral region, cheek, back and gluteal region, abdomen, forearm, hands, feet including palms and sole (Figs. 2, 3), bilateral cataract, brachydactyly, erythematous papules over axilla and foot associated with itching along with pallor and hepatosplenomegaly. Investigations revealed pancytopenia with febrile neutropenia. Routine urine and CSF examination were normal. Blood cultures and urine cultures were negative. Serology for TORCH group of infections, dengue and typhoid were negative. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatosplenomegaly. Chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly. Peripheral smear examination revealed mild anisocytosis, platelets were reduced and differential leucocyte count revealed 13 % neutrophils, 85 % lymphocytes and 2 % monocytes. Neutrophils revealed inclusion like structures and coarse granules (Fig. 4). Bone marrow examination revealed cellular preparations with M:E ratio 1:4 (erythroid hyperplasia). Erythropoeisis was megaloblastic with features of dyserythropoeisis. The most characteristic feature was presence of one to two to numerous intracytoplasmic eosinophilic coarse granules and inclusion-like granules in the granulocytic cells, lymphocytes and monocytes (Figs. 5, 6). The granules were positive for myeloperoxidase (Fig. 7). Histiocytes revealed phagocytosis of hematopoietic cells. Thus a diagnosis of Chediak-Higashi syndrome in accelerated phase was made. Unfortunately, the child died within 1 month of diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Silver grey hair on scalp and eyebrows

Fig. 2.

Hypopigmented lesions on back and gluteal region

Fig. 3.

Hypopigmented lesions on chest, abdomen and forearm

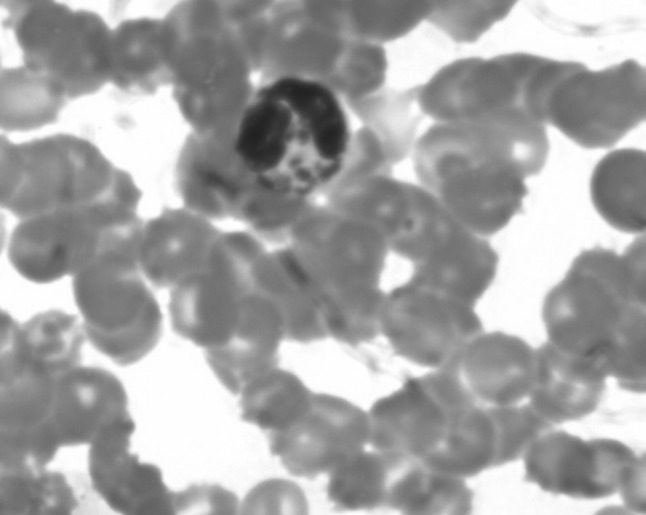

Fig. 4.

PBF: eosinophilic coarse granules in neutrophils

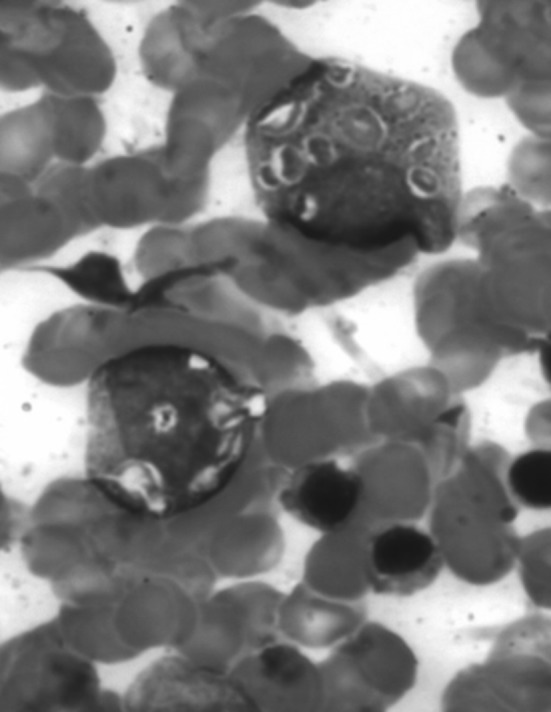

Fig. 5.

BMA: inclusion like granules in myeloid precursors

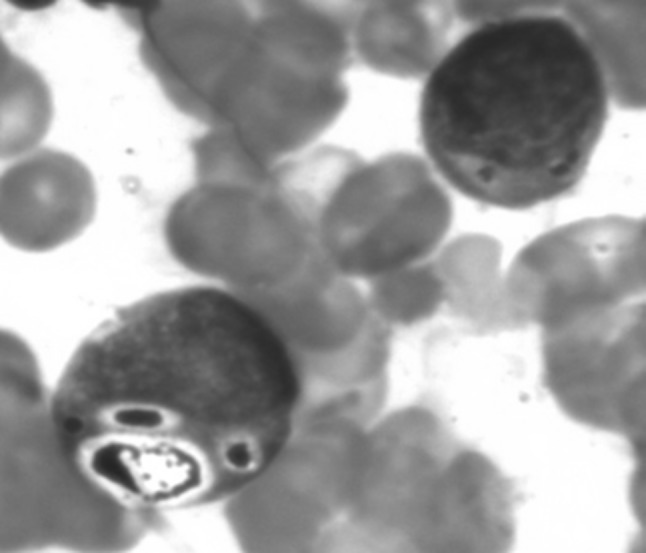

Fig. 6.

BMA: eosinophilic inclusion like granules

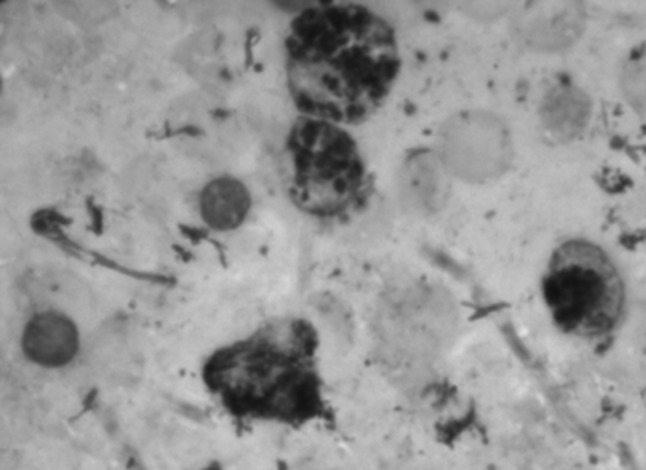

Fig. 7.

BMA: myeloperoxidase positive granules

Discussion

CHS was first described by Bequez-cesar in 1943. Later Chediak, a Cuban hematologist and Higashi, a Japanese paediatrician described a series of cases in 1952 and 1954 respectively. In 1955 Sato coined the term Chediak-Higashi syndrome [2]. Mean age of presentation is 2 years and male to female ratio is 1:1 [4].

The basic pathology in CHS is defect in the lysosomal trafficking regulator (LYST) gene on chromosome 1, whose gene product regulates intracellular protein trafficking to and from the lysosome. Impaired function of this protein disrupts the size, structure and function of lysosomes in the body, resulting in the accumulation of large intracellular vesicles within:

Granulocytes resulting in impaired phagolysosome fusion, thus increasing susceptibility to bacterial infections.

Platelets resulting in coagulopathies, thus easy bruisability and bleeding diathesis.

Melanocytes resulting in faulty intracellular transportation of melanin and the presence of giant melanosomes in the melanocytes leading to partial oculo-cutaneous albinism, fair skin and silver hair.

They may also present with sensory and/or motor neurological disorders or nystagmus [1]. An additional finding that has not been reported in any previous case reports but seen in our case is bilateral cataract.

Uyama et al. suggested two distinct clinical presentations: (1) the more commonly recognized childhood form with a typical history of recurrent infections leading to early death or an accelerated phase and (2) the rare adult type in which neurological defects resembling parkinsonism, dementia or spinocerebellar degeneration and peripheral neuropathy dominate with a lack of increased susceptibility to infections [5].

Roy et al. [6] in 2011 studied the clinicohematological profile of 5 cases of CHS and concluded that the diagnostic hallmark of CHS is the occurrence of giant inclusion bodies (granules) in the peripheral leukocyte and their bone marrow precursors.

The condition has to be differentiated from various clinical entities. The clinical features of Griscelli syndrome are similar to Chediak-Higashi syndrome but the presence of myeloperoxidase positive inclusions in the bone marrow helped to delineate the condition. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is a platelet storage deficiency disorder manifesting as easy bruising and a bleeding tendency associated with oculo-cutaneous albinism and pulmonary fibrosis but there is no defect in circulating lymphocytes or neutrophils which differentiates this disease from the condition of our patient. In patients of Prader Willi’s syndrome and Angelman’s syndrome, there is hypopigmentation but usually no typical ocular features of albinism. In Prader Willi’s syndrome, the characteristic features are neonatal hypotonia, hyperphagia, hypogonadism and mental retardation while in Angelman’s syndrome, there is severe mental retardation, microcephaly, neonatal hypotonia, ataxic movements and inappropriate laughter. Waardenburg syndrome is a neural crest disorder. Pie-baldism, with a white forelock hypopigmentation, congenital deafness, synophrys and dystopia canthorum (broad nasal root) are the distinct clinical features. Myeloblasts also fail to survive. In lazy leukocyte syndrome, pus is absent in cutaneous lesions and neutrophilia is a constant finding [7]. Acute and chronic myeloid leukemia may show giant granules resembling those seen in CHS, also referred to as pseudo-Chediak-Higashi anomaly [2].

About 50–85 % of the patients with CHS enter into an accelerated phase manifested by fever, jaundice, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and widespread lymphohistiocytic infiltration of various organs with hemophagocytosis leading to pancytopenia and bleeding disorder secondary to low platelets and fibrinogen levels. This child had five out of seven clinical features and evidence of hemophagocytosis on bone marrow examination thus concluding that the child had progressed to the accelerated phase of Chediak-Higashi syndrome and died within 1 month of diagnosis.

Bone marrow transplant (BMT) is the treatment of choice before the accelerated phase. Without BMT, children of CHS die before 10 years of age [4]. Familial consanguinity has been described in 50 % of CHS cases in the literature, yet there have been many reports of CHS in children of unrelated parents. Prenatal diagnosis is a technically difficult process, but can be made by measuring acid phosphatase-positive lysosomes from cultures of amniotic fluid cells, chorionic villous cells, or leukocytes isolated from foetal blood [1].

To conclude, CHS is an extremely rare condition with a poor prognosis. Characteristic clinical features and typical blood and bone marrow findings are essential for early diagnosis and treatment.

Contributor Information

Shivani Sood, Phone: +1772807748, Phone: +9418026680, Email: shivanisood343@rediff.com.

Biswajit Biswas, Email: drbiswajit2031@gmail.com.

Vijay Kaushal, Email: drkaushalvijay@gmail.com.

Tanish Mandal, Email: tanishmandal@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Saeed N, Al-Saed K, Shome D, Jamsheer H. A child with Chediak-Higashi and trisomy 21 syndromes. Royal Coll Surg Ireland Stud Med J. 2012;5:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rani H, Kanabur D. Accelerated phase of Chediak-Higashi syndrome—a case report with review of literature. J Pediatr Sci. 2012;4:e167. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayaranee S, Menaka N. Chediak-Higashi syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pathol. 2004;26:53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farhoudi A, Chavoshzadeh Z, Pourpak Z, Izadyar M, Gharagoslou M, Movahedi M, et al. Report of six cases of Chediak-Higashi syndrome with regard to clinical and laboratory findings. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;2:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pujani M, Agarwal K, Bansal S, Ahmad I, Puri V, Verma D, et al. Chediak-higashi syndrome- a report of two cases with unusual hyperpigmentation of the face. Turkish J Pathol. 2011;27:246–248. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2011.01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy A, Kar R, Basu D, Srivani S, Badhe M. Clinico-hematologic profile of Chediak-Higashi syndrome: experience from a tertiary care centre in south India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:547–551. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.77324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masood A, Nadeem M, Aman S, Kazmi A. Chediak-Higashi syndrome—a case report. Annals. 2008;14:119–122. [Google Scholar]