Abstract

Rhinovirus infection is typically associated with the common cold and has rarely been reported as a cause of severe pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. A 55-year-old previous healthy woman, who consumed half a bottle of alcohol daily, presented with respiratory failure after one week of upper respiratory infection symptoms. Radiography revealed bilateral, diffuse ground glass opacity with patchy consolidation in the whole lung field; bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis indicated that rhinovirus was the causative organism. After five days of conservative support, the symptoms and radiographic findings began to improve. We report this rare case of rhinovirus pneumonia in an otherwise healthy host along with a review of references.

Keywords: Rhinovirus, Pneumonia, Alcohol Drinking

Introduction

Rhinovirus infection is typically associated with the common cold1,2 and exacerbation of asthma symptoms3. Rhinovirus infection can extend to lower respiratory tract in children4,5,6 or immunocompromised hosts7,8, but is generally not concerned as singular cause of severe pneumonia, especially in immunocompetent adults. Although polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods have enhanced the detection of respiratory viral infection, PCR cannot help distinguish between causative and commensal pathogens in specimen obtained by nasopharyngeal aspiration. Data on viral pneumonia are increasing; however, severe rhinovirus pneumonia resulting respiratory failure in an immunocompetent host is still regarded as extremely unusual.

Case Report

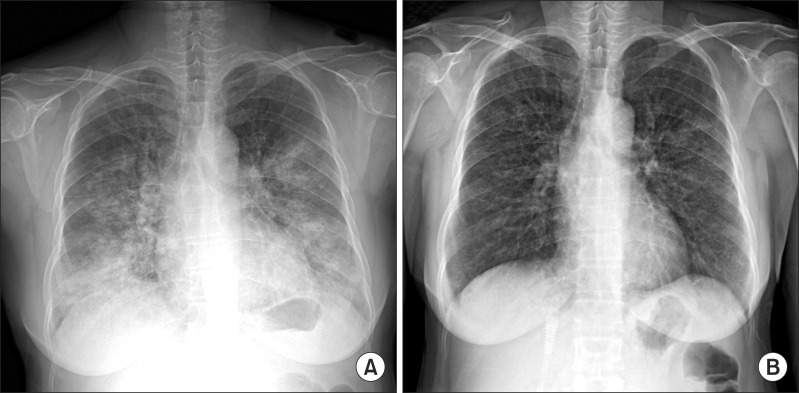

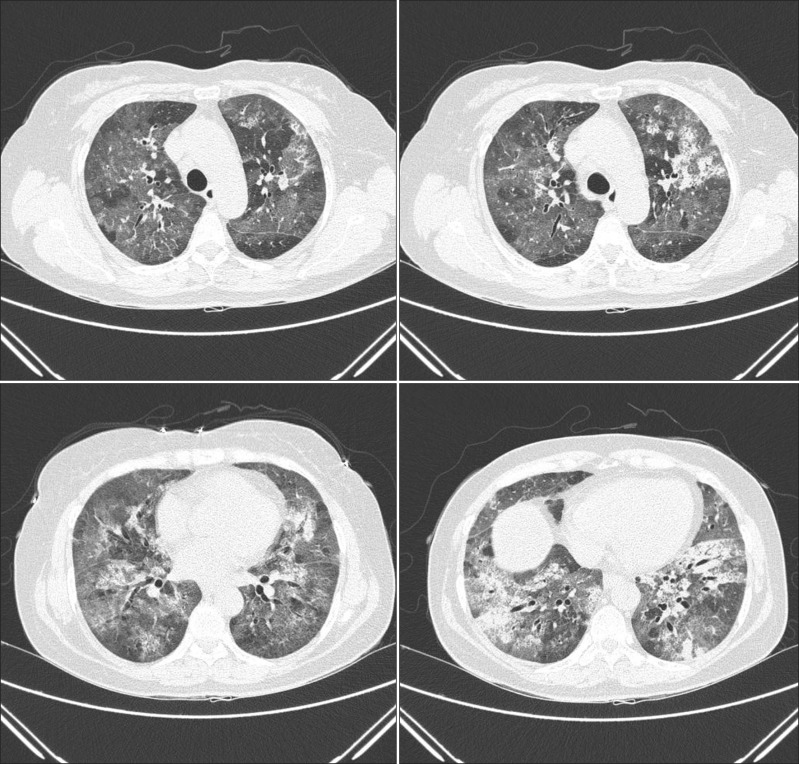

A 55-year-old woman visited our emergency department in September with two-day history of progressive dyspnea. The patient had never smoked and had no other previous medical history, but consumed half a bottle of alcohol daily. The patient had got a common cold one week prior, but her symptoms aggravated despite empirical treatment. After 5 days, she began to experience shortness of breath. Exertional dyspnea progressed to resting dyspnea the following day and at the emergency room, her initial peripheral oxygen saturation was 70%. Wet crackles and expiratory wheezing sounds were present in the whole lung field area. Evaluation of the patient's vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg, body temperature of 36.6℃, pulse rate of 108 beats per minute, and respiration rate of 30 breaths per minute. Simple chest radiography showed the predominance of bilateral consolidation with ground glass opacity (GGO) in both lower lobes (Figure 1A). Chest computed tomography indicated diffuse GGO with patchy consolidations in the whole lung field, but pleural effusion was not present (Figure 2). Laboratory tests revealed a white cell count of 20,930/mm3 (differential count: 91.5% neutrophils, 6.4% lymphocytes, and 0% eosinophil), hemoglobin concentration 12.7 g/dL, platelet count 366,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 84 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein level 43.1 mg/dL. Analysis of arterial blood gases indicated a PaO2 of 33.5 mm Hg, PaCO2 26.1 mm Hg, HCO3 19.7 mmol/L, and SaO2 71.1% without acidosis. The patient's liver and renal function tests were within normal range. High-flow O2 therapy and broad-spectrum antibiotics with oseltamivir (Tamiflu, Roche, Utley, NJ, USA) were started empirically, and bronchoscopy was performed immediately. Total cell counts of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were 240 cells/mm3, including 75% neutrophils, 4% mononuclear cells, 1% eosinophil, and 20% macrophages. Cultures for common bacteria, acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were all negative. PCR for Pneumocystis jirovecii, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were also negative. However, PCR of BAL fluid indicated the presence of rhinovirus, which was not detected following PCR of the nasopharyngeal specimen. Mycoplasma antibody and urinary pneumococcal antigen test were negative. Serologic test for venereal disease research laboratory test, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B, C antibodies, and human immunodeficiency virus, as well as for autoantibodies such as anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were all negative. Clinical symptoms and infiltration on chest X-ray began to improve after five days (Figure 1B), and the patient was discharged from hospital after three weeks.

Figure 1.

Chest radiography findings at the initial visit and after 1 week. (A) Initial chest X-ray. (B) After 1 week.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography findings of initial lung infiltration.

Discussion

Although technical advances have allowed for increased detection of viral pneumonia, viral infections other than influenza are generally not considered as causes of severe respiratory tract infection in immunocompetent hosts, because viral clearance usually occurs rapidly in healthy individuals. However, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, avian influenza A (H5N1) virus, and the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus raised the importance of lower respiratory tract viral infections. Additionally, new respiratory viruses, such as human metapneumovirus, coronavirus, and human bocavirus were found to be causes of severe viral pneumonia. The use of molecular diagnostic assays has enhanced the detection of respiratory virus infection; however, the identification of virus does not necessarily mean that it is a lower respiratory tract infection pathogen9,10,11. Therefore, it is still believed that severe viral pneumonia caused by frequently exposed rhinovirus could hardly occurs in immunocompetent adults. According to Choi et al.12, viruses are frequently detected in the airway of pneumonia patients who require intensive care unit admission, and may cause severe forms of pneumonia. In this study, rhinovirus was identified in 8.6% of respiratory specimens evaluated, but most of patients were the elderly individuals who had underlying comorbidities including structural lung disease, diabetes mellitus, solid cancer, or hematologic malignancies. On the contrary, our relatively young immunocompetent patient suffered severe rhinovirus pneumonia without bacterial co-infection, which was confirmed by BAL fluid analysis, and not by the nasopharyngeal specimen.

Two possible explanations exist for the occurrence of this extremely rare case. First, despite prior indications, severe rhinovirus pneumonia may actually occur in an immunocompetent host. Second, chronic alcoholic ingestion could be a major immune modulator for respiratory viral infection, apart from alcoholic liver damage. Some previous reports revealed the influence of alcohol on innate immunity in the respiratory system13,14,15, but the unfavorable impact could play a more critical role in viral defense mechanisms than expected.

In conclusion, although the clinical significance of habitual alcoholic ingestion in viral pneumonia requires further evaluation, viral etiology should be considered in cases of severe pneumonia even though in immunocompetent adults, especially if alcoholics.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Hobson D, Schild GC. Virological studies in natural common colds in Sheffield in 1960. Br Med J. 1960;2:1414–1418. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5210.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsyth BR, Bloom HH, Johnson KM, Chanock RM. Patterns of illness in rhinovirus infections of military personnel. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:602–606. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196309192691203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. BMJ. 1993;307:982–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvo C, Garcia-Garcia ML, Blanco C, Pozo F, Flecha IC, Perez-Brena P. Role of rhinovirus in hospitalized infants with respiratory tract infections in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:904–908. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31812e52e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louie JK, Roy-Burman A, Guardia-Labar L, Boston EJ, Kiang D, Padilla T, et al. Rhinovirus associated with severe lower respiratory tract infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:337–339. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ffc1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayden FG. Rhinovirus and the lower respiratory tract. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14:17–31. doi: 10.1002/rmv.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks LA, Shepard CW, Britz PH, Erdman DD, Fischer M, Flannery BL, et al. Two outbreaks of severe respiratory disease in nursing homes associated with rhinovirus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longtin J, Marchand-Austin A, Winter AL, Patel S, Eshaghi A, Jamieson F, et al. Rhinovirus outbreaks in long-term care facilities, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1463–1465. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings LC, Anderson TP, Beynon KA, Chua A, Laing RT, Werno AM, et al. Incidence and characteristics of viral community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax. 2008;63:42–48. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.075077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnstone J, Majumdar SR, Fox JD, Marrie TJ. Viral infection in adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: prevalence, pathogens, and presentation. Chest. 2008;134:1141–1148. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011;377:1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi SH, Hong SB, Ko GB, Lee Y, Park HJ, Park SY, et al. Viral infection in patients with severe pneumonia requiring intensive care unit admission. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:325–332. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201112-2240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi PC, Guidot DM. The alcoholic lung: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and potential therapies. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L813–L823. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00348.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polikandriotis JA, Rupnow HL, Elms SC, Clempus RE, Campbell DJ, Sutliff RL, et al. Chronic ethanol ingestion increases superoxide production and NADPH oxidase expression in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:314–319. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0320OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang M, Bala S, Kodys K, Catalano D, Szabo G. Inhibition of TLR8- and TLR4-induced Type I IFN induction by alcohol is different from its effects on inflammatory cytokine production in monocytes. BMC Immunol. 2011;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]