Abstract

Background

Carbapenem-resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii has gradually become a global challenge. To identify the genes involved in carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii, the transcriptomic responses of the completely sequenced strain ATCC 17978 selected with 0.5 mg/L (IPM-2 m) and 2 mg/L (IPM-8 m) imipenem were investigated using RNA-sequencing to identify differences in the gene expression patterns.

Results

A total of 88 and 68 genes were differentially expressed in response to IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m selection, respectively. Among the expressed genes, 50 genes were highly expressed in IPM-2 m, 30 genes were highly expressed in IPM-8 m, and 38 genes were expressed common in both strains. Six groups of genes were simultaneously expressed in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m mutants. The three gene groups involved in DNA recombination were up-regulated, including recombinase, transposase and DNA repair, and beta-lactamase OXA-95 and homologous recombination. The remaining gene groups involved in biofilm formation were down-regulated, including quorum sensing, secretion systems, and the csu operon. The antibiotic resistance determinants, including RND efflux transporters and multidrug resistance pumps, were over-expressed in response to IPM-2 m selection, followed by a decrease in response to IPM-8 m selection. Among the genes over-expressed in both strains, blaOXA-95, previously clustered with the blaOXA-51-like family, showed 14-fold (IPM-2 m) to 330-fold (IPM-8 m) over-expression. The expression of blaOXA-95 in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells was positively correlated with the rate of imipenem hydrolysis, as demonstrated through Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry, suggesting that blaOXA-95 plays a critical role in conferring carbapenem resistance. In addition, A. baumannii shows an inverse relationship between carbapenem resistance and biofilm production.

Conclusion

Gene recombination and blaOXA-95 play critical roles in carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii. Taken together, the results of the present study provide a foundation for future studies of the network systems associated with carbapenem resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-815) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, Carbapenem resistance, Transcriptome profiling

Background

In the last decades, A. baumannii has gradually emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen worldwide, reflecting antimicrobial resistance, tolerance to desiccation and disinfection and biofilm formation on common abiotic surfaces in healthcare settings [1]. Carbapenems, primarily imipenem and meropenem, have been used to treat multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii infections [1]. However, the increasing incidence of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) infections in Taiwan and many other countries has become of critical concern [2].

Currently, several MDR determinants contribute to the antimicrobial resistance observed in this microorganism. The most prevalent MDR determinants in A. baumannii include genes for efflux pumps, class B β-lactamase (metallo-beta-lactamase), class C chromosomal β-lactamase AmpC, class D β-lactamase (OXA-type carbapenemase), integrons and associated insertion sequence (IS) elements [1]. Virulence factors associated with resistance, including biofilm formation, and surface and extracellular polysaccharides associated with capsule formation have also been demonstrated [3]. While progress has been made in characterizing the determinants of antibiotic resistance in this organism, few reports have shown the expression patterns or mechanisms underlying the acquisition or control of these genes.

To characterize the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms underlying MDR in A. baumannii, several approaches to examine gene expression profiles have been developed. Proteomics methods using two-dimensional electrophoresis (2D) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) have been used to examine changes in A. baumannii protein expression associated with drug resistance [4–6]. Yun et al. [4] identified 484 proteins with expression differences in the clinical MDR strain DU202 subjected to sub-minimum inhibitory concentration levels of tetracycline and imipenem. Chopra et al. [5] compared the proteome of the MDR strain BAA-1605 and a reference strain, identifying nearly 200 proteins with expression differences between the two strains. Indeed, the proteomics approaches using 2D and LC-MS/MS might provide large-scale proteomics involved in antibiotic resistance; however, less than 25% of proteins could be detected, reflecting the limitations of 2D approaches. Also, microarray technology has been used to screen and quantify the expression profiles of antibiotic resistance genes in A. baumannii [7]. However, this approach has been restricted to the study of previously known genes, which would not reveal the entire transcriptional profile of genes expressed upon exposure to antibiotics.

Among the recent techniques used to analyze the whole RNA profiles of microorganisms are next generation sequencing (NGS), 454 GS_FLX (Roche), MiSeq or HiSeq (Illumina Inc.) platforms, and ABI SOLiD (Life Technology). RNA sequencing using the Illumina system has been regarded as an extremely informative technique for the study of transcriptional profiles of microorganisms, as these techniques are sensitive and rapid [8, 9]. However, in the last two years, there have only very few studies using RNA-sequencing technologies in A. baumannii [10–12]. Using transcriptional profiling and functional assays in a mutant strain, Cerqueira et al. [12] identified a global virulence regulator in A. baumannii that controls the phenylactic acid catabolic pathway. Using the same approach, Eijkelkamp et al. [10] also identified a role for the gene encoding a homolog of the histone-like nucleoid structuring (H-NS) protein involved in A. baumannii virulence. Currently, there is only one report concerning the whole transcriptome analysis of the genes involved in biofilm formation in A. baumannii [11]. Rumbo-Feal et al. [11] identified 1621 genes over-expressed in biofilms relative to stationary phase cells and 55 genes expressed only in biofilms. Among the genes over-expressed in biofilms were those involved in quorum sensing and the CsuAB-A-B-C-D-E chaperone-usher secretion system. Although biofilm formation has been implicated in antibiotic resistance in bacteria [13], the correlation between antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation in A. baumannii remains poorly understood.

In a previous study [14], we employed genome-wide analysis to characterize the potential resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 following imipenem exposure. Genome-wide analysis showed that exposure to 0.5 mg/L imipenem mediated the transposition of ISAba1, located upstream of the blaOXA-95 gene, resulting in the overexpression of the blaOXA-95 gene. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the carbapenem resistance mechanism in A. baumannii using the Illumina RNA-sequencing technologies. We therefore obtained transcriptome profiles from A. baumannii ATCC 17978 and its carbapenem-selected mutants, and these profiles were compared to identify differences in the gene expression profiles. The results of the present study will provide insight into the mechanisms underlying carbapenem resistance and their association with biofilm formation in A. baumannii.

Results

Susceptibility testing

Antibiotic-selected mutants were generated from the ATCC 17978 type strain. The identities of the selected mutants originated from ATCC 17978 were confirmed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The results of antibiotic susceptibility testing for these mutants and the parental strain are shown in Table 1. The reference strain 17978 was susceptible to all antibiotics tested. The MICs to meropenem and imipenem were increased more than four-fold in response to IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m selection at concentrations of 0.5 and 2 mg/L imipenem. In addition, the MICs of the imipenem-selected mutants to the other antibiotics were similar compared with the ATCC 17978 strain.

Table 1.

Susceptibility of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 selected with imipenem

| Antibiotics | 17978 | IPM-2 m | IPM-8 m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imipenem-selected concentration (mg/L) | |||

| 0 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| Imipenema | ≦0.25 | 1 | ≧16 |

| Meropenema | ≦0.25 | 2 | ≧16 |

| Ceftazidime | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cefepime | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Amikacin | ≦2 | ≦2 | ≦2 |

| Gentamicin | ≦1 | ≦1 | ≦1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≦0.25 | ≦0.25 | ≦0.25 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ampicillin/subactam | ≦2 | 4 | 4 |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | 160 | 160 | 160 |

aA more than fourfold induction is indicated in boldface.

Determination of the transcriptomes of imipenem-selected mutants and the parental strains

The total RNA fractions purified from IPM-2 m, IPM-8 m and ATCC17978 strains were analyzed to determine the respective gene expression levels and identify differentially expressed genes. Three libraries were constructed and subjected to paired-end sequencing using HiSeq 2000 (Illumina). The reads were aligned against the chromosomes and plasmids of A. baumannii ATCC 17978. A total of 11,995,382, 11,933,930, and 12,036,770 paired reads with lengths of 90 bases × 2 were obtained for IPM-2 m, IPM-8 m, and ATCC 17978, respectively. Approximately 99% of the transcribed genes aligned in the A. baumannii ATCC 17978 genome database (NC_009085.1) were recorded.

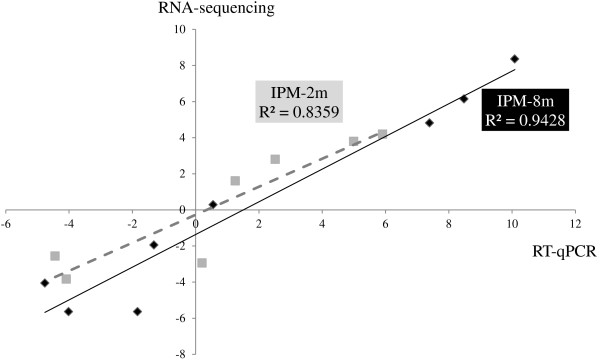

The transcriptomic results, obtained using RNA sequencing, were validated through the RT-qPCR analysis of a subset of differentially expressed genes as shown in Figure 1. A good correlation was observed between the RT-qPCR data and the results obtained from the transcriptome analysis of IPM-2 m (R2 = 0.8359) and IPM-8 m (R2 = 0.9428).

Figure 1.

Validation of the transcriptome results. The transcriptomic results obtained through RNA sequencing were validated using qualitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. The level of differential expression of eight genes was compared, showing a correlation between RNA sequencing (Y-axis) and RT-qPCR analysis (X-axis). The level of differential expression between A. baumannii ATCC 17978 and their mutants is given as Log2-values. R2, the coefficient of determination.

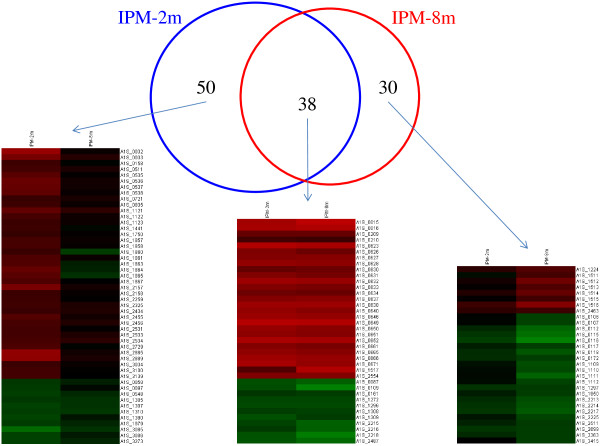

The gene expression profiles of imipenem-selected cells

The expression patterns of IPM-2 m vs. ATCC 17978 cells and IPM-8 m vs. ATCC 17978 cells were compared to identify differentially expressed transcripts. The up- and down-regulated genes were determined based on differences with p values below 0.05. Figure 2 shows the differentially expressed genes in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m relative to the ATCC 17978 strain. A total of 88 and 68 genes were differentially expressed in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m, respectively. Among these, 50 genes were highly expressed in IPM-2 m, 30 genes were highly expressed in IPM-8 m, and 38 genes were expressed common in both strains.

Figure 2.

The differentially expressed genes in IMP-2 m and IMP-8 m relative to the ATCC 17978 wild-type strain. A Venn Diagram showing the relationship of differentially expressed genes between IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m. The heatmaps shown below demonstrate the expression patterns of the 50 genes unique to IPM-2 m, the 30 genes unique to IPM-8 m, and the 38 genes common to both strains.

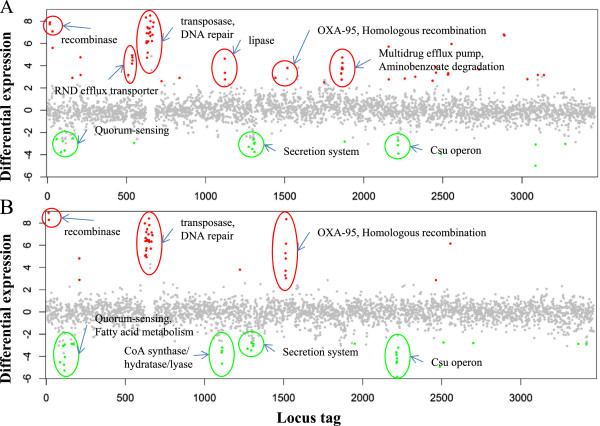

Figure 3 summarizes the transcriptional responses of ATCC 17978 upon selection with 0.5 mg/L (IPM-2 m) and 2 mg/L (IPM-8 m) imipenem. The differentially expressed genes were classified into functional groups based on COG category or KEGG pathways as shown in Table 2. Six groups of genes were identified: three groups were up-regulated, including recombinase, transposase and DNA repair, and beta-lactamase OXA-95 and homologous recombination, and three groups were down-regulated, including quorum sensing, secretion systems, and the csu operon, and these gene groups were simultaneously expressed in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m mutants. In addition, three groups of genes, including the RND efflux pump, lipase, the multidrug efflux pump and aminobenzoate degradation, were up-regulated in IPM-2 m, and two groups of genes, including fatty acid metabolism and CoA synthase, hydratase and lyase, were down-regulated only in IPM-8 m. The genes with the highest overexpression were located in recombinase and transposase and DNA repair groups in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells, highlighting the potential importance of these genes in carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii. Moreover, a rapid increase in blaOXA-95 (A1S_1517) expression from 14-fold (IPM-2 m) to 330-fold (IPM-8 m) suggests that blaOXA-95 might participate in carbapenem resistance. The rapid reduction gene expression upon imipenem induction was observed in the following groups: homoserine lactone synthase (A1S_0109), 17- (IPM-2 m) to 70-fold (IPM-8 m) reduction; quorum sensing group (A1S_0112, 0115, 0116,0117 and 0118), average 5- to 20-fold reduction; CoA synthase, hydratase and lyase group (A1S_1109, 1110 and 1111 ), 1.5- to 17-fold reduction; and the csu operon (A1S_2213 to A1S_2218), 8- to 25-fold reduction. Notably, many up-regulated genes were only restricted to IPM-2 m. Among 50 up-regulated genes, ten genes annotated as putative signal peptides were highly expressed in IPM-2 m cells, followed by a decrease in expression in IPM-8 m cells.

Figure 3.

Overview of the transcriptional difference between the IPM strains and the ATCC 17978 wild-type strain. Comparative transcriptomics are displayed as differential expression (log2 transformed fold change) in (A) IPM-2 m and (B) IPM-8 m relative to ATCC 17978. The dots indicate the differential expression of all open reading frames, sorted on the x-axis according to the locus tag. Genes with p-values < 0.05 are considered differentially expressed. The red dots indicate up-regulated genes, whereas the green dots indicate down-regulated genes. Some differentially expressed genes are indicated in the literature and KEGG pathway information.

Table 2.

Functional groups of differentially expressed genes between mutant strains and ATCC 17978

| Locus tag | log2 (fold change) | log2 (fold change) | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|

| in IPM-2 m | in IPM-8 m | ||

| Recombinase | |||

| A1S_0015 | 7.74 | 8.92 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0015 |

| A1S_0016 | 7.90 | 8.30 | Site-specific tyrosine recombinase |

| Fatty acid metabolism | |||

| A1S_0106 | -0.23 | -3.05 | Putative enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase |

| A1S_0107 | -0.27 | -3.08 | Putative enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase family protein |

| A1S_0109 | -3.62 | -6.03 | Homoserine lactone synthase |

| Quorum sensing | |||

| A1S_0112 | -1.86 | -4.76 | Acyl-CoA synthetase/AMP-acid ligases II |

| A1S_0115 | -2.47 | -5.27 | Amino acid adenylation |

| A1S_0116 | -2.97 | -6.01 | RND superfamily transporter |

| A1S_0117 | -1.38 | -2.92 | Hypothetical proteinA1S_0117 |

| A1S_0118 | -2.01 | -4.06 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0118 |

| Transposase | |||

| A1S_0209 | 4.76 | 4.82 | Transposase |

| A1S_0210 | 3.17 | 2.89 | Transposase |

| RND eflux transporter | |||

| A1S_0535 | 4.19 | 0.28 | RND efflux transporter |

| A1S_0536 | 4.93 | 0.86 | Macrolide transport protein |

| A1S_0537 | 4.74 | 0.83 | RND efflux transporter |

| A1S_0538 | 4.48 | 0.39 | RND efflux transporter |

| Transposase and DNA repair | |||

| A1S_0623 | 8.34 | 7.98 | DNA mismatch repair enzyme |

| A1S_0626 | 6.04 | 5.06 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0626 |

| A1S_0627 | 6.20 | 6.38 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0627 |

| A1S_0628 | 6.93 | 6.67 | Putative transposase |

| A1S_0630 | 4.72 | 5.14 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0630 |

| A1S_0631 | 6.12 | 5.52 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0631 |

| A1S_0632 | 7.45 | 7.19 | DNA primase |

| A1S_0633 | 6.13 | 5.74 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0633 |

| A1S_0634 | 5.17 | 4.93 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0634 |

| A1S_0637 | 6.21 | 6.52 | DNA-directed DNA polymerase |

| A1S_0638 | 7.37 | 7.45 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0638 |

| A1S_0640 | 6.91 | 6.41 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0640 |

| A1S_0646 | 7.36 | 7.00 | IcmB protein |

| A1S_0649 | 8.52 | 8.43 | Putative phage primase |

| A1S_0650 | 7.02 | 6.46 | Conjugal transfer protein |

| A1S_0651 | 6.67 | 6.32 | TraB protein |

| A1S_0652 | 8.02 | 7.83 | Putative ferrous iron transport protein A |

| A1S_0661 | 6.22 | 5.70 | Phage integrase family protein |

| A1S_0665 | 6.79 | 6.34 | Conjugal transfer protein TrbJ |

| A1S_0666 | 7.50 | 7.16 | TrbL/VirB6 plasmid conjugal transfer protein |

| A1S_0671 | 7.89 | 6.92 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase |

| CoA synthase/hydratase/lyase | |||

| A1S_1109 | -0.77 | -3.66 | Feruloyl-CoA synthase |

| A1S_1110 | -0.48 | -3.48 | Hydroxybenzaldehyde dehydrogenase |

| A1S_1111 | -0.41 | -4.66 | P-hydroxycinnamoyl CoA hydratase/lyase |

| A1S_1112 | -0.53 | -3.19 | Putative 3-hydroxyphenylpropionic transporter MhpT |

| Lipase | |||

| A1S_1121 | 4.63 | 2.24 | Lipase/esterase |

| A1S_1122 | 3.36 | 0.67 | Putative short-chain dehydrogenase |

| A1S_1123 | 2.77 | 0.59 | Putative flavin-binding monooxygenase |

| Bacterial secretion system, OOP family | |||

| A1S_1272 | -3.30 | -3.31 | Putative transcriptional regulator |

| A1S_1296 | -3.49 | -3.45 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1296 |

| A1S_129 | -2.42 | -2.77 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1297 |

| A1S_1305 | -2.59 | -2.36 | Putative outer membrane lipoprotein |

| A1S_1307 | -3.03 | -2.35 | Putative ClpA/B-type chaperone |

| A1S_1308 | -2.93 | -3.06 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1308 |

| A1S_1309 | -3.75 | -2.86 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1309 |

| A1S_1310 | -2.91 | -2.58 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1310 |

| Homologous recombination; Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | |||

| A1S_1511 | -0.58 | 3.30 | Biotin synthase |

| A1S_1512 | 0.96 | 5.28 | Putative ferredoxin |

| A1S_1513 | 0.27 | 3.71 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1513 |

| A1S_1514 | 1.61 | 4.81 | Holliday junction nuclease |

| A1S_1515 | 0.24 | 3.04 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1515 |

| A1S_1516 | 2.80 | 6.15 | Putative antibiotic resistance |

| A1S_1517 | 3.79 | 8.36 | Beta-lactamase OXA-95 |

| Multidrug efflux pump; Aminobenzoate degradation | |||

| A1S_1750 | 2.52 | 0.26 | AdeB |

| A1S_1857 | 3.29 | 0.51 | Vanillate O-demethylase oxidoreductase |

| A1S_1858 | 3.32 | 0.36 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR |

| A1S_1860 | 2.74 | -2.86 | Ring hydroxylating dioxygenase Rieske (2Fe-2S) protein |

| A1S_1861 | 3.70 | 0.53 | Benzoate dioxygenase large subunit |

| A1S_1863 | 3.84 | -1.41 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1863 |

| A1S_1864 | 4.73 | -1.58 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-like protein |

| A1S_1865 | 4.25 | -2.30 | Glu-tRNA amidotransferase |

| A1S_1867 | 3.71 | 0.03 | Major facilitator transporter |

| Csu Operon | |||

| A1S_2213 | -2.06 | -3.63 | CsuE |

| A1S_2214 | -2.40 | -3.86 | CsuD |

| A1S_2215 | -3.14 | -4.57 | CsuC |

| A1S_2216 | -2.73 | -4.45 | CsuB |

| A1S_2217 | -2.53 | -4.18 | CsuA |

| A1S_2218 | -3.89 | -5.88 | CsuA/B |

| ABC transporters | |||

| A1S_2531 | 3.20 | 0.22 | Sulfate transport protein |

| A1S_2533 | 3.21 | 1.45 | Putative esterase |

| A1S_2534 | 3.34 | 2.02 | Sulfate transport protein |

| Others | |||

| A1S_0032 | 7.09 | 0.49 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_0033 | 5.60 | 1.73 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_0058 | -2.62 | -1.47 | Glycosyltransferase |

| A1S_0087 | -3.76 | -4.52 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR |

| A1S_0097 | -2.79 | -0.41 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0097 |

| A1S_0158 | 2.91 | -0.15 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0158 |

| A1S_0161 | -2.53 | -2.86 | MFS family transporter |

| A1S_0172 | -2.10 | -2.92 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0172 |

| A1S_0511 | 3.17 | 1.25 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0511 |

| A1S_0548 | -2.94 | -1.92 | TetR family transcriptional regulator |

| A1S_0721 | 2.62 | 1.15 | Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| A1S_0835 | 2.91 | 0.52 | Outer-membrane lipoprotein precursor |

| A1S_1224 | 2.03 | 3.81 | Transposase |

| A1S_1390 | -3.20 | -0.97 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1390 |

| A1S_1441 | 2.91 | -0.31 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_1879 | -2.81 | -1.76 | Hypothetical protein A1S_1879 |

| A1S_1950 | -1.32 | -2.85 | Putative universal stress protein |

| A1S_2157 | 5.72 | 1.02 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2158 | 2.78 | 0.36 | Putative monooxygenase |

| A1S_2225 | -1.04 | -3.21 | Hypothetical protein A1S_2225 |

| A1S_2259 | 2.84 | 0.15 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2325 | 3.00 | 1.40 | Putative outer membrane protein |

| A1S_2434 | 2.65 | 1.60 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2455 | 3.89 | 0.89 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2456 | 3.38 | 1.59 | LysR family transcriptional regulator |

| A1S_2463 | 2.16 | 2.87 | Putative ribosomal large subunit pseudouridine synthase A(RluA-like) |

| A1S_2487 | -3.93 | -4.93 | Hypothetical protein A1S_2487 |

| A1S_2511 | -1.62 | -2.74 | Phenylacetic acid degradation-related protein |

| A1S_2554 | 5.96 | 6.16 | Putative transposase |

| A1S_2699 | -2.51 | -2.80 | Putative transcriptional regulator |

| A1S_2729 | 3.67 | -0.15 | Outer-membrane lipoproteins carrier protein |

| A1S_2885 | 6.80 | 0.78 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2889 | 6.72 | 1.25 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_3034 | 2.80 | 0.44 | Hypothetical protein A1S_3034 |

| A1S_3085 | -5.00 | -2.34 | Putative flavohemoprotein |

| A1S_3086 | -3.09 | -1.21 | Hypothetical protein A1S_3086 |

| A1S_3100 | 3.18 | 0.18 | Putative toluene tolerance protein (Ttg2D) |

| A1S_3139 | 3.16 | 0.03 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_3273 | -3.03 | -1.79 | Putative peptide signal |

| A1S_3363 | -1.98 | -2.86 | Membrane metalloendopeptidases proteins |

| A1S_3415 | 0.09 | -2.84 | Maleylacetoacetate isomerase |

Table 3 shows the comparative results of differentially expressed genes in imipenem-selected mutants and biofilm-associated ATCC 17978, as previously described [11]. Many biofilm-associated genes, including quorum sensing-associated genes (A1S_0109, A1S_0112 and A1S_0115) and the CsuAB-A-B-C-D-E chaperone-usher secretion system (A1S_2214, A1S_2215 and A1S_2218), were inversely expressed in imipenem-selected mutants. However, four genes encoding the RND efflux transporter, sulfate transport protein and putative signal peptides, were overexpressed in both strains, indicating that those genes might participate in pathways overlapping carbapenem resistance and biofilm formation.

Table 3.

Comparison of differentially expressed genes between imipenem-selected mutants (this study) and biofilm-associated ATCC 17978 cells as decribed by Rumbo-Feal et al. (12)

| Locus tag | Log2 (fold change) in IPM-2 m | Log2 (fold change) in IPM-8 m | Log2 (fold change) biofim vs.expotenetial phase cells a | Protein Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inverse expressed between imipenem-resistant mutants and biofilm-associated cells | ||||

| NameA1S_0087 | -3.76 | -4.52 | 1.36 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR |

| A1S_0109 | -3.62 | -6.03 | 5.91 | Homoserine lactone synthase |

| A1S_0112 | -1.86 | -4.76 | 6.23 | Acyl-CoA synthetase/AMP-acid ligases II |

| A1S_0115 | -2.47 | -5.27 | 7.24 | Amino acid adenylation |

| A1S_0116 | -2.97 | -6.01 | 5.81 | RND superfamily transporter |

| A1S_0117 | -1.38 | -2.92 | 4.58 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0117 |

| A1S_0118 | -2.01 | -4.06 | 3.21 | Hypothetical protein A1S_0118 |

| A1S_2214 | -2.40 | -3.86 | 7.49 | CsuD |

| A1S_2215 | -3.14 | -4.57 | 7.65 | CsuC |

| A1S_2218 | -3.89 | -5.88 | 7.36 | CsuA/B |

| Overexpressed both in imipenem-resistant mutants and biofilm-associated cells | ||||

| A1S_0538 | 4.48 | 0.39 | 2.72 | RND efflux transporter |

| A1S_2534 | 3.34 | 2.02 | 4.40 | Sulfate transport protein |

| A1S_0032 | 7.09 | 0.49 | 5.01 | Putative signal peptide |

| A1S_2889 | 6.72 | 1.25 | 5.54 | Putative signal peptide |

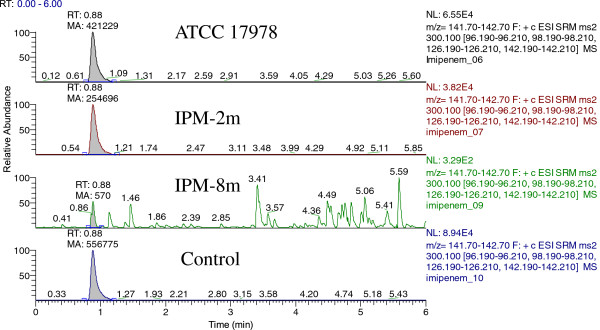

Measurement of carbapenemase hydrolysis

To examine carbapenemase hydrolysis in ATCC 17978, IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells, LC-MS/MS was performed, and the results are shown in Figure 4. The rate of imipenem hydrolysis was calculated by dividing the imipenem area after the incubation procedure by A. baumannii ATCC 17978 area. Compared with IPM-2 m, the rate of imipenem hydrolysis in IPM-8 m showed a 430-fold increase.

Figure 4.

LC-MS/MS chromatogram of imipenem under co-incubating with A. baumannii ATCC 17978, IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells. Control, imipenem standard solution.

Quantitative analysis of biofilm formation

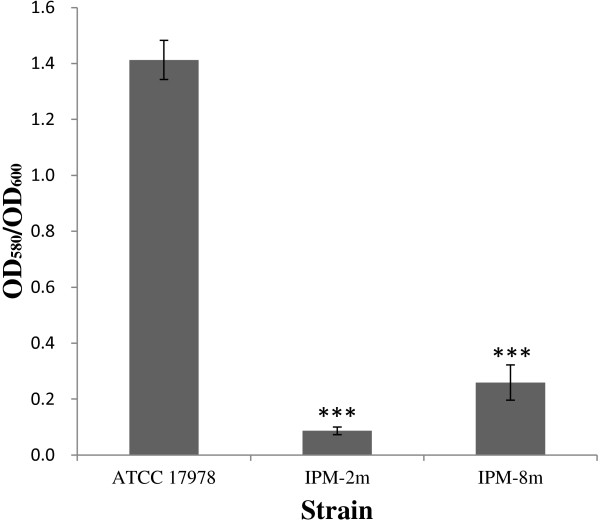

To clarify the association between biofilm formation and carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii, biofilm formation in ATCC 17978 and imipenem-selected mutants was quantitative analyzed as shown in Figure 5. A significant decrease in biofilm formation (p < 0.001) was observed in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells, indicating an inverse relationship between carbapenem resistance and biofilm production in A. baumannii ATCC 17978.

Figure 5.

Quantification of biofilm formation in A. baumannii strains on plastic surface. To determine total cell mass the OD600 was measured after the cultures were briefly sonicated to resuspend most of the cells. The OD580 was measured after the stained tubes were incubated with ethanol-acetone. The error bar show the S.D. ***,p < 0.0001 using Student’s t-test comparing mutant and wild-type strains.

Discussion

In the present study, we successfully constructed an antibiotic-induction platform to observe dynamic transcriptome changes upon carbapenem selection. A. baumannii ATCC 17978 was selected as the study material based on three advantages. First, the complete genome of this organism has been sequenced since 2007 [15]. Second, the MICs for most commonly used antibiotics, such as the 3rd cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, are still susceptible; thus, A. baumannii ATCC 17978 would be a model candidate for antibiotic selection experiments. Third, the gradual increase of MIC observed only for carbapenem suggests that the carbapenem-specific resistance mechanism could be studied using an imipenem-selected platform.

In our previous study using genome-wide analysis [14], we demonstrated that imipenem exposure at a concentration of 0.5 mg/L only mediated the transposition of ISAba1 upstream of the blaOXA-95 gene. None of the other genes in imipenem-selected mutants were modified, rearranged or acquired by horizontal-gene transfer upon imipenem exposure compared to their parental strains. To continue the previous study, herein, we examined the transcriptional profiles of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 upon selection with imipenem gradient. Despite all the gene expression analysis were done with strains cultured in the absence of antibiotics, the MICs to imipenem in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m remained unchangeable, indicating that these mutants were stable. Besides, the MICs observed in response to imipenem selection in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells were 1 and >16 mg/L, respectively, reflecting imipenem-susceptibility and imipenem-resistance according to the CLSI guidelines [16]. Thus, the results of the present study showed the dynamic changes in the transcriptome profiles, from imipenem-susceptible to imipenem-resistance during the selection period, representing the first study to demonstrate the potential mechanisms underlying carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii ATCC 17978.

Thus, several novel findings have been revealed in the present study. First, many of the highly expressed genes encoding proteins for recombinase, transposase, and DNA repair were simultaneously observed in IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m cells. This result suggests that genome recombination might play an important role in conferring carbapenem resistance, consistent with the conclusions of several reports using genetic analysis [17, 18]. Second, the overexpression of several genes involved in RND efflux transporters and fatty acid metabolism were observed in IPM-2 m cells, and this expression was reduced in IPM-8 m cells. Despite several reports emphasizing the major role of efflux pumps in the development of antimicrobial resistance in Acinetobacter spp. [19, 20], the results obtained herein are consistent with those of previous reports showing that efflux pumps, particularly RND-type transporters, play an important role in the initial exposure to imipenem and are subsequently down-regulated during carbapenem resistance. In other words, efflux pumps alone may be not sufficient to provide protection against a high concentration of carbapenem. Third, several genes involved in quorum sensing and the CsuAB-A-B-C-D-E chaperone-usher secretion system are down-regulated upon selection with imipenem. The disruption of these genes has been associated with a decrease in biofilm formation [11]. The results of other studies concerning carbapenem resistance and biofilm formation showed reduced biofilm formation in meropenem (MEM)-resistant A. baumannii isolates compared with MEM-susceptible strains [21], consistent with the results obtained in either biofilm-associated gene expression or the phenotypic determination of biofilm production in A. baumannii strains. To date, the ability of A. baumannii to form biofilms that adhere to and persist on a broad range of surfaces might be key to revealing the pathogenic mechanisms of this microorganism [22]. Therefore, we hypothesize that carbapenem resistance might reduce virulence through the reduction of biofilm production in some A. baumannii strains.

The rapid adaption to the environment might emphasize the ability of microorganisms to live under external stress. Dynamic changes in genome architecture and gene expression are required for organisms to survive in their environment. Dynamic changes in the gene expression of A. baumannii have been observed in biofilm compared with planktonic cells using whole transcriptome analysis [11]. Also, the transcriptional responses of A. baumannii to environmental stress have been reported [23, 24]. For example, several siderophore biosynthesis genes were up-regulated in response to iron starvation and therefore are likely to be important for the survival of A. baumannii in iron-limited environments. In addition, various type IV pilus genes were also down-regulated [23]. In the present study, dynamic changes in the transcriptional responses to carbapenem concentrations ranging from 0.5 mg/L (mild stress) to 2 mg/L (stringent stress) have also been observed. Herein, we propose a "bacterial energy conversion hypothesis" to describe the dynamic changes in the transcriptome upon carbapenem stress in A. baumannii ATCC 17978. First, the net energy required for metabolism is constant throughout the life of the cell. For rapid adaption and survival upon environmental stress, many genes in cells are monitored and up-regulated to overcome the external stress, and much energy is required for the expression of these genes. However, several genes that are not required for survival are down-regulated to save energy. In the present study, several genes, including the RND efflux transporter, lipase, recombination-associated proteins, and blaOXA-95, are up-regulated in A. baumannii upon exposure to mild carbapenem stress. Several biofilm-associated genes, including quorum sensing, protein secretion system and the CsuAB-A-B-C-D-E chaperone-usher secretion system, which could be not required against for imipenem pressure, have been down-regulated. To adapt to a more stringent environment, the overexpression of target survival genes, e.g. blaOXA-95, is needed, resulting in the consumption of most of the energy in the cell. Thus, some of the genes up-regulated during mild stress, e.g. efflux pumps, are down-regulated so as to transform excess energy and maintain cell viability despite efflux pumps play important roles in the resistance to antibiotics [25]. The bacterial energy conversion hypothesis requires more evidences to verify, however, in the present study, the results of transcriptomic analysis and LC-MS/MS demonstrated that blaOXA-95 might play a critical role in survival upon exposure to stringent carbapenem stress in A. baumannii ATCC 17978. Moreover, the transposition of ISAba1 upstream of the blaOXA-95 gene is observed upon exposure to mild carbapenem stress, suggesting that the upstream signaling pathway linking external stress and ISAba1 transposition may be a critical mechanism for carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii ATCC 17978.

Conclusions

This study defined the global transcriptional response of A. baumannii to imipenem exposure. The up-regulation of recombination-associated genes and blaOXA-95 was the predominant feature of this transcriptional response. Several genes involved in biofilm formation, such as quorum sensing, protein secretion system and the CsuAB-A-B-C-D-E chaperone-usher secretion system, were down-regulated upon imipenem selection, resulting in the reduction of biofilm production. Overall, the results indicated that A. baumannii adapts to an environment with carbapenem availability.

Methods

Bacterial strains

A. baumannii ATCC 17978 was used as a parental strain. The carbapenem-selected mutants were generated from the parental strain using a previously described method [26]. The selected strains exposed to 0.5 and 2 mg/L imipenem were collected during the induction period and referred to as IPM-2 m and IPM-8 m. The genotypic patterns in the selected mutants and the parental strain were determined using PFGE, as previously described [27].

Antimicrobial susceptibility

The susceptibility of the Acinetobacter mutants and the parental strain to antimicrobial agents was determined using a microdilution method in accordance with the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [16]. The agents tested included ampicillin/sulbactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, imipenem and meropenem. Escherichia coli strain ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain ATCC 27853 were used as reference controls for the susceptibility testing. A four-fold or greater induction in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values after exposure to imipenem was considered significantly different from the control.

RNA isolation and library preparation for transcriptome sequencing

A. baumannii cultures were grown to log phase (OD600 1.00) in Muller Hinton broth with shaking at 37°C before RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated from cells using the PureLink™ Micro-to-Midi Total RNA Purification System (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA quantity and quality were assessed using a BIOANALYZER 2100 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Germany), followed by RNA-Seq. The RNA integrity number (RIN) of total RNA should be greater than 8.0, and rRNA ratio (23S/16S) should be greater than 1.2.

The RNA-sequencing library was prepared as previously described [28]. The constructed sequencing libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at Beijing Genome Institute (BGI, Shenzhen, China).

Analysis of the RNA-Seq data

The sequenced libraries were mapped against predicted transcripts from the Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 genome using TopHat v2.0.4 [29]. The transcript abundance (FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped) and significant changes in transcript expression were estimated using Cufflinks v2.0.2 [30, 31]. Transcripts with p-values less than 0.05, determined using CuffDiff [31], were considered differentially expressed between mutant and wild-type strains. The transcripts were annotated with Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) and protein functions according to their locus tags [32]. The functional groups comprising differentially expressed transcripts were manually curetted based on COG annotation, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [33], and studies cited in the corresponding main text. Raw sequences were deposited at the NCBI sequence Read Archive under the Bioproject accession number PRJNA244702.

Quantitative biofilm formation

Biofilm formation on polystyrene was assessed through the crystal violet staining of cells cultured in LB broth as previously described [34]. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

Reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Gene expression was analyzed using a previously described method [26]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from 1 × 109A. baumannii cells. After DNase treatment of the RNA samples and cDNA synthesis, RT-qPCR was performed as previously described [26]. The template cDNA was diluted 1:100, and 2.5 μl was added to SYBR green PCR master mix (Biogenesis Technologies, Inc., Taiwan) for each reaction. An Eco Real-Time PCR System (Illumina) was used for analysis. Internal forward and reverse primers for each gene were designed using the DesignStudio web-based tool (Illumina), as described in supporting information (Additional file 1: Table S1). The experiments were repeated in triplicate independent experiments. Normalization to the 16S ribosomal gene facilitated the calculation of the fold-changes using the threshold cycle (CT) method [35].

Detection of carbapenemase hydrolysis using LC-MS/MS

Each strain was analyzed using LC-MS/MS to detect imipenem hydrolysis as previously described [36]. Briefly, the strains were cultured overnight on Mueller-Hinton agar. The bacteria were dissolved in normal saline solution and adjusted to OD600 = 2.0. A 1-mL volume of this suspension was incubated with 5 μg/mL of imipenem for 1 h at 37°C with smooth agitation. The suspensions were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min, and 300 μL of supernatant was mixed with 700 μL of methanol. After centrifugation at 12,000 g for 5 min, 200 μL of supernatant was mixed with 800 μL of water. The abundance of imipenem was measured through LC-MS/MS using the Thermo Accela LC system (Waltham, MA) coupled to a TSQ Quantum tandem triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer. Briefly, the chromatography step was performed using a fused-core Poroshell C18 column (Agilent) and eluted with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in methanol). Chromatographic separation was achieved through gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.32 mL/min. The injection volume was 10 μL. The retention time for imipenem was 0.88 min. Ionization was achieved using electrospray in positive ionization mode (ESI+). The multiple-reaction-monitored parameters were optimized through post-column infusion of the stock solution (1 μg/mL) using Quantum TuneMaster software (ThermoFisher).The parameters included tube lens (72.3) and collision energy (27 V) for imipenem transition (m/z 300.1 > 142.2).

Statistical analysis

The differences in biofilm production between imipenem-selected mutants and the parental strains were analyzed using Student’s t-test, as appropriate. The differences between the two groups of isolates were considered significant at the p < 0.05 level. The data entry and analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Table S1: Oligonucleotides used in RT-qPCR. (XLSX 10 KB)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Hsin-Yu Li, Ms. Hui-Wen Yeh and Ms. Jhih-Hua Peng for technical support. The present study was partially supported through a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology (grant MOST 103-2627-M-126 -001; grant MOST 103-2622-E-126-002-CC1) and Taiwan University Hospital Hsin Chu Branch (grant HCH102-15).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HYK, KCC and MLL designed the research project. KCC, CWC, CWL, CYT, CCL, HRL and KHC carried out the experiment. MLL wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kai-Chih Chang, Email: kaichih@mail.tcu.edu.tw.

Han-Yueh Kuo, Email: han_yueh@hotmail.com.

Chuan Yi Tang, Email: cytang@pu.edu.tw.

Cheng-Wei Chang, Email: d924546@oz.nthu.edu.tw.

Chia-Wei Lu, Email: d9762807@oz.nthu.edu.tw.

Chih-Chin Liu, Email: ccliu@chu.edu.tw.

Huei-Ru Lin, Email: rita0107@mail.tcu.edu.tw.

Kuan-Hsueh Chen, Email: f309942@yahoo.com.tw.

Ming-Li Liou, Email: d918229@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(10):3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsueh PR. Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) in the Asia-pacific region, 2002–2010. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40(Suppl):S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(12)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(3):538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yun SH, Choi CW, Kwon SO, Park GW, Cho K, Kwon KH, Kim JY, Yoo JS, Lee JC, Choi JS, Kim S, Kim SI. Quantitative proteomic analysis of cell wall and plasma membrane fractions from multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(2):459–469. doi: 10.1021/pr101012s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra S, Ramkissoon K, Anderson DC. A systematic quantitative proteomic examination of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Proteomics. 2013;84:17–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siroy A, Cosette P, Seyer D, Lemaitre-Guillier C, Vallenet D, Van Dorsselaer A, Boyer-Mariotte S, Jouenne T, De E. Global comparison of the membrane subproteomes between a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain and a reference strain. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(12):3385–3398. doi: 10.1021/pr060372s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne S, Guigon G, Courvalin P, Perichon B. Screening and quantification of the expression of antibiotic resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii with a microarray. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):333–340. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camarena L, Bruno V, Euskirchen G, Poggio S, Snyder M. Molecular mechanisms of ethanol-induced pathogenesis revealed by RNA-sequencing. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):e1000834. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dotsch A, Eckweiler D, Schniederjans M, Zimmermann A, Jensen V, Scharfe M, Geffers R, Haussler S. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptome in planktonic cultures and static biofilms using RNA sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eijkelkamp BA, Stroeher UH, Hassan KA, Elbourne LD, Paulsen IT, Brown MH. H-NS plays a role in expression of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence features. Infect Immun. 2013;81(7):2574–2583. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rumbo-Feal S, Gomez MJ, Gayoso C, Alvarez-Fraga L, Cabral MP, Aransay AM, Rodriguez-Ezpeleta N, Fullaondo A, Valle J, Tomas M, Bou G, Poza M. Whole transcriptome analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii assessed by RNA-sequencing reveals different mRNA expression profiles in biofilm compared to planktonic cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerqueira GM, Kostoulias X, Khoo C, Aibinu I, Qu Y, Traven A, Peleg AY. J Infect Dis. 2014. A global virulence regulator in Acinetobacter baumannii and its control of the phenylacetic acid catabolic pathway. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo HY, Chang KC, Liu CC, Tang CY, Peng JH, Lu CW, Tu CC, Liou ML. Microb Drug Resist. 2014. Insertion sequence transposition determines imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, Gerstein M, Snyder M. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21(5):601–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1510307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard [ http://www.clsi.org/source/orders/free/m07-a8.pdf]

- 17.Mugnier PD, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Functional analysis of insertion sequence ISAba1, responsible for genomic plasticity of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(7):2414–2418. doi: 10.1128/JB.01258-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Montero CI, Stock F, Mijares L, Murray PR, Segre JA. Genome-wide recombination drives diversification of epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(33):13758–13763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vila J, Marti S, Sanchez-Cespedes J. Porins, efflux pumps and multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(6):1210–1215. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu WS, Yao SM, Fung CP, Hsieh YP, Liu CP, Lin JF. An OXA-66/OXA-51-like carbapenemase and possibly an efflux pump are associated with resistance to imipenem in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(11):3844–3852. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez LR. J Chemother. 2014. Acinetobacter baumannii displays inverse relationship between meropenem resistance and biofilm production. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(12):939–951. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eijkelkamp BA, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT, Brown MH. Investigation of the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii under iron limiting conditions. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs AC, Sayood K, Olmsted SB, Blanchard CE, Hinrichs S, Russell D, Dunman PM. Characterization of the Acinetobacter baumannii growth phase-dependent and serum responsive transcriptomes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;64(3):403–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyne S, Courvalin P, Perichon B. Efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):947–953. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01388-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo HY, Chang KC, Kuo JW, Yueh HW, Liou ML. Imipenem: a potent inducer of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo HY, Yang CM, Lin MF, Cheng WL, Tien N, Liou ML. Distribution of blaOXA-carrying imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. in 3 hospitals in Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;66(2):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Yu YH, Cao SY, Niu XN, Jiang W, Liu GF, Jiang BL, Tang DJ, Lu GT, He YQ, Tang JL. Transcriptome profiling of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris grown in minimal medium MMX and rich medium NYG. Res Microbiol. 2013;164(5):466–479. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12(3):R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomaras AP, Dorsey CW, Edelmann RE, Actis LA. Attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: involvement of a novel chaperone-usher pili assembly system. Microbiology. 2003;149(Pt 12):3473–3484. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carricajo A, Verhoeven PO, Guezzou S, Fonsale N, Aubert G. Detection of carbapenemase-producing bacteria by using an ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(2):1231–1234. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01540-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1: Oligonucleotides used in RT-qPCR. (XLSX 10 KB)