Background: Fbxo45 is an atypical E3 ligase that plays an important role in neuronal development.

Results: Fbxo45 binds to N-cadherin intracellularly and prevents its degradation.

Conclusion: By protecting N-cadherin from proteolysis, Fbxo45 plays a key role in promoting N-cadherin-mediated neuronal differentiation.

Significance: This study reveals a novel mechanism of Fbxo45-mediated neuronal differentiation.

Keywords: Calcium, Cell Differentiation, Endocytosis, Intramembrane Proteolysis, Plasma Membrane

Abstract

Fbxo45 is an atypical E3 ubiquitin ligase, which specifically targets proteins for ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Fbxo45 ablation results in defective neuronal differentiation and abnormal formation of neural connections; however, the mechanisms underlying these defects are poorly understood. Using an unbiased mass spectrometry-based proteomic screen, we show here that N-cadherin is a novel interactor of Fbxo45. N-cadherin specifically interacts with Fbxo45 through two consensus motifs overlapping the site of calcium-binding and dimerization of the cadherin molecule. N-cadherin interaction with Fbxo45 is significantly abrogated by calcium treatment. Surprisingly, Fbxo45 depletion by RNAi-mediated silencing results in enhanced proteolysis of N-cadherin. Conversely, ectopic expression of Fbxo45 results in decreased proteolysis of N-cadherin. Fbxo45 depletion results in dramatic reduction in N-cadherin expression, impaired neuronal differentiation, and diminished formation of neuronal processes. Our studies reveal an unanticipated role for an F-box protein that inhibits proteolysis in the regulation of a critical biological process.

Introduction

Fbxo45 is one of the six F-box proteins that are evolutionarily conserved from Caenorhabditis elegans (FSN-1), Drosophila melanogaster (DFsn), to Mus musculus (1). Unlike other F-box proteins that interact with CUL1 to form a SCF (Skp1, CUL1, F-box protein) complex (2). Fbxo45 along with Skp1 interacts with MYCBP2 (Myc binding protein 2) also known as protein associated with Myc (PAM) to form an atypical E3 ligase (3–5). Structurally, Fbxo45 contains an F-box motif at its N terminus that interacts with Skp1 and a SPRY (SplA and ryanodine receptor) domain at its C terminus, which has been shown to function as a substrate recognition motif in other SPRY-containing E3 ligases (6–8). However, in the F-box protein family, Fbxo45 is the only member that contains a SPRY domain. Previous studies have indicated that Fbxo45 is involved in controlling synapse formation (3), neurotransmitter release (9), as well as neural differentiation (4, 10). However, the molecular mechanisms leading to such diverse effects of Fbxo45 are complex and poorly understood. Both Fbxo45 and MYCBP2 knock-out mice exhibit perinatal lethality and display similar neurological defects suggesting that both molecules may functionally interact and play key roles in neuronal development (4, 11).

N-cadherin (neural-cadherin, CDH2) is one of the classical cadherins that mediate calcium-dependent homophilic cell-cell adhesion (12). N-cadherin is abundantly expressed in neural tissues and has been shown to play important roles in morphogenesis (13), synaptogenesis (14, 15), growth, and guidance of axons during development (16). Its functions are modified by changes in the quantity, subcellular localization, as well as expression pattern during development (13). However, little is known about how these changes are regulated at the post-translational level. Although multiple E3 ligases (17–19) have been identified to target E- or VE-cadherin for degradation, there is no report of any E3 ligase associated with N-cadherin function.

In this study, we isolated Fbxo45-associated immunocomplexes and subjected them to analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Using this approach, we identified N-cadherin as a specific interactor of Fbxo45. Biochemical studies revealed that the interaction is sensitive to high concentrations of calcium and Fbxo45 serves to protect N-cadherin from proteolysis in the absence of calcium. We also demonstrated that Fbxo45 plays a key role in N-cadherin-dependent neuronal differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Antibodies

Fbxo45 cDNA was cloned from a K562 cell line into pENTR/d-TOPO vector and subcloned into a streptavidin-HA tandem affinity purification tag vector (kindly provided by Dr. Stephane Angers). FLAG-tagged F-box protein constructs, including Fbxl1(Skp2), Fbxw1(β-TrCP), Fbxw2, Fbxw4, Fbxw5, Fbxw7, and Fbxo22 were kindly provided by Dr. Michele Pagano. Both Skp2 and β-TrCP were also subcloned into the tandem affinity purification tag vector (20). Skp1 and N-cadherin cDNAs were obtained from Open Biosystems. The following antibodies were used in the studies: N-cadherin-3B9, Skp1 (Invitrogen), N-cadherin-EPR1791–4 (Abcam), V5-HRP, M2-FLAG (Sigma), HA (Covance), MYCBP2 (Novus Biologicals), R-cadherin, β-catenin, actin, and tubulin (Cell Signaling).

Co-immunoprecipitation Studies

Cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C. For immunoprecipitation (IP),2 cells were lysed for 30 min in IP buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on ice. Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation and immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies for 2 h to overnight at 4 °C. Protein complexes were collected by incubation for 2 h with strepavidin-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) or protein A/G-agarose beads (Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were washed four times with IP buffer, boiled in SDS sample buffer, and analyzed by immunoblotting. Cell lysates containing equal amount of total protein were separated on 4% to 12% gradient gels by SDS-PAGE using the NuPage Novex Bis-Tris Mini Gel System (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences) by semidry transfer. Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline, 0.05% Tween 20, 3.0% nonfat dry milk). Membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with indicated antibodies diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer. Membranes were washed four times, 15 min each, in Tris-buffered saline and 0.05% Tween 20. This was followed by a 1-h room temperature incubation in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) diluted 1:4000 in blocking buffer. Membranes were washed and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Identification of Fbxo45 Immunocomplex Components by Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Immunoprecipitated samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie stain. In-gel digestion by trypsin was carried out using procedure standardized at the Proteomics Resource Facility (University of Michigan). Tryptic peptides were resolved on a nano-capillary reverse phase column and introduced directly into a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (LTQ XL, Thermo). The mass spectrometer was set to collect one survey scan (MS1), followed by MS/MS spectra on the nine most intense ions observed in MS1 scan. Proteins were identified by searching the MS/MS spectra against human protein database using X!Tandem/TransProteomic Pipeline software suite. All proteins identified with a probability of ≥0.9 were kept for further analysis.

Transient Transfection and Lentivirus-mediated Gene Silencing

SMARTpool siRNA targeting at human Fbxo45 and Non-Targeting SMARTpool siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific). The siRNA duplexes were transfected in subconfluent 293T cells with X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer's instructions. For lentivirus-mediated gene transduction, 293FT cells were co-transfected with lentiviral construct of shRNA and packaging vectors (Invitrogen). Virus-producing supernatant was harvested 48 h after transfection and supplemented with polybrene and used to infect mouse embryonic stem cells. Lentiviral vectors pGIPZ containing shRNA targeting different region of mouse Fbxo45 (V2LHS_182000, V2LHS_222040, and V2LHS_254545) as well as non-silencing control were purchased from Open Biosystems.

Conventional and Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the PureLink RNA mini kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real time-PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out using the QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen), and data were analyzed using Rotor-Gene Q software package (Corbett Life Science-Qiagen, Inc.) as described (21).

The following sets of human- and mouse-specific Fbxo45 primers were used to measure levels of Fbxo45 mRNA: human, 5′-AGT GCC AAG GTT ATG TGG CAT TGC TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGA AAG CCA CTG TCA TCC GTC CAA AG-3′ (reverse); and mouse, 5′-GTT GGT GTT CTC CTA CCT GGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAT TCG TGC TGA AGG CAT GTT-3′ (reverse). The following sets of human- and mouse-specific GAPDH primers were used as normalization controls: human, 5′-CCT GAC CTG CCG TCT AGA AAA ACC TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCC TGT TGC TGT AGC CAA ATT CGT TG-3′ (reverse); and mouse, 5′-AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGT AGA CCA TGT AGT TGA GGT CA-3′ (reverse).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cultured cells grown on coverslips were fixed and permeabilized with methanol/acetone (1:1). Cells were incubated with indicated primary antibodies followed by Alexa Fluor-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 594, red) or anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor 488, green) secondary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted on standard slides with mounting medium supplemented with DAPI. The images were captured and recorded using an Olympus BX-51 upright light microscope equipped with an Olympus DP-70 camera. Confocal images were obtained on an Olympus FluoView 500 laser-scanning confocal system mounted on an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope.

Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Culture and Neuronal Differentiation

Mouse ES cells were maintained in Glasgow media (Sigma) with 10% fetal bovine serum and supplemented with leukemia inhibitory factor (1,000 units/ml, Chemicon). Cells were plated on tissue culture dishes coated with 0.1% gelatin and split every 48 h. Before differentiation, cells were immunostained with SSEA-1 (mouse ES cell marker, Millipore) to confirm the cells are properly maintained in the undifferentiated state. Neural differentiation of control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells were initiated according to the protocols described in the mouse embryonic stem cell neurogenesis kit (Millipore). In brief, mouse ES cells were cultured in embryoid body formation medium in a non-adhesive 10-cm Petri dish for 4 days in the absence of leukocyte inhibitory factor to help form tight clusters of cells called embryoid bodies. Directed differentiation of ES cells to the neuronal lineage was initiated upon the addition of neuronal inducer solution containing 0.5 μm retinoic acid for an additional 4 days. Neuronal induced embryoid bodies are subsequently transferred to poly-l-ornithine- and laminin-coated slides and in embryoid body formation medium for an additional 8 days. After differentiation, cells were stained with either Cy3-labeled βIII-tubulin antibody (Millipore) or FITC-labeled N-cadherin antibody (Life Technologies). DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain.

RESULTS

Identification of N-cadherin as a Specific Interactor of Fbxo45

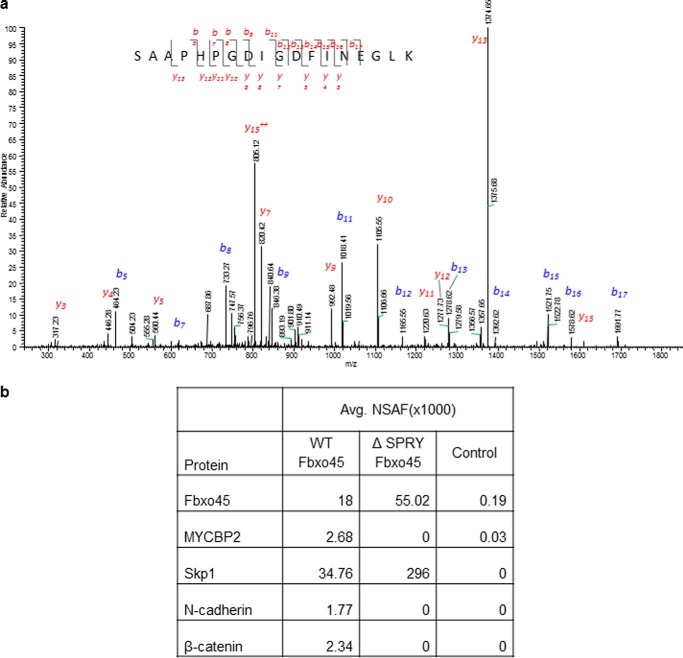

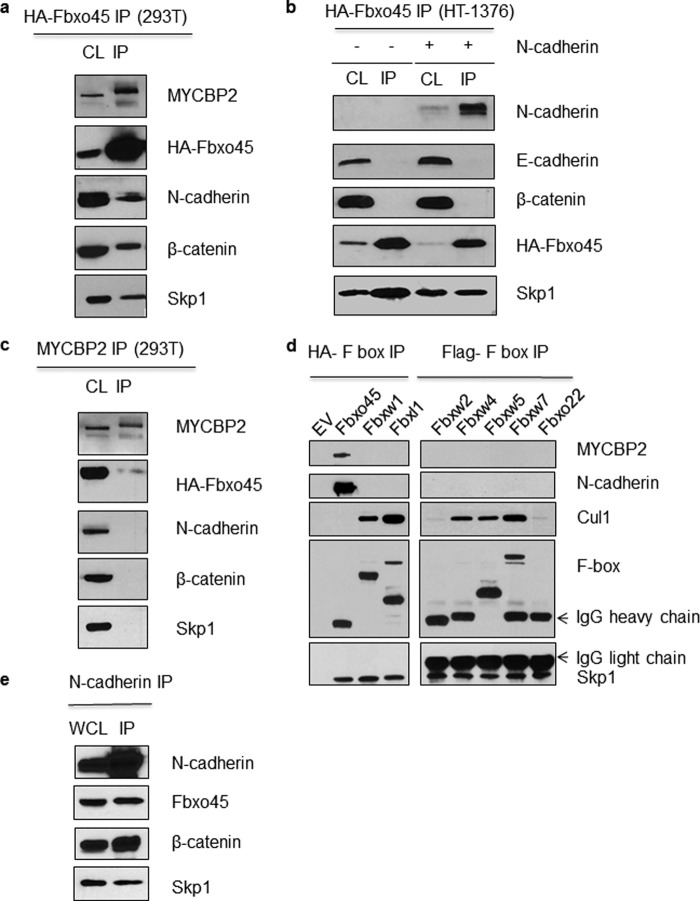

To identify potential interactors of Fbxo45, we performed a tandem affinity purification of Fbxo45 complexes followed by LC-MS/MS analysis using lysates of U87MG cell expressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45. As shown in Fig. 1a, one of the prominent peptides identified in the analysis belongs to N-cadherin. Both known interactors of Fbxo45, Skp1 and MYCBP2, were also identified to co-immunoprecipitate with Fbxo45 (Fig. 1b). As shown by the normalized spectral abundance factor analysis in Fig. 1b, in the absence of the SPRY domain (ΔSPRY), the F-box domain-only protein immunoprecipitated Skp1 but not MYCBP2, indicating that the SPRY domain is required for this interaction. β-Catenin, another protein that belongs to the adherens junction complex, was also identified by MS/MS as to co-immunoprecipitate with Fbxo45 (Fig. 1b). Both N-cadherin and β-catenin, components of the adherens junction complex, were further confirmed in Western blot analysis (Fig. 2a). To determine which of the two proteins is a direct interactor of Fbxo45, we performed an immunoprecipitation experiment in HT-1376 cells that express β-catenin and E-cadherin (CDH1) but not N-cadherin (CDH2). In these cells, HA-Fbxo45 immunoprecipitated Skp1 but not β-catenin, indicating that β-catenin alone is not sufficient for the interaction to occur (Fig. 2b). Co-transfection of N-cadherin in these cells, allow N-cadherin but not β-catenin to be immunoprecipitated by Fbxo45 (Fig. 2b). These results clearly demonstrate that N-cadherin is a direct interactor of Fbxo45. We further showed that Fbxo45 does not interact with E-cadherin, another classical cadherin closely related to N-cadherin (Fig. 2b), suggesting that the interaction is quite specific among cadherin proteins. Because MYCBP2 is also part of the Fbxo45-mediated E3 ligase complex, we postulated that N-cadherin may interact indirectly through MYCBP2. As shown in Fig. 2c, in the MYCBP2 co-immunoprecipitation experiment, as expected as part of the atypical E3 ligase complex, Fbxo45 was co-immunoprecipitated by MYCBP2. However, no N-cadherin or β-catenin were immunoprecipitated by MYCBP2, indicating that MYCBP2 is not a direct interactor of N-cadherin.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of N-cadherin as a specific interactor of Fbxo45. a, U87MG cells were transfected with empty vector (control) or streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 (F45) and whole cell extracts (WCE) were subjected to IP with streptavidin resin. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Following in-gel digestion with trypsin, MS/MS spectra were acquired using an Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. Protein/peptide identification was carried out by searching MS/MS spectra against human protein database using X!Tandem/TPP software suite. Representative MS/MS spectrum of a peptide from N-cadherin (824SAAPHPGDIGDFINEGLK841) is shown. Observed b- and y-ions are indicated. b, identification of proteins in MS analysis of Fbxo45 IP. Quantitation of proteomic data were achieved by normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) analyses based on an isoform-specific algorithm generating a minimally redundant set of protein annotations explaining all of the peptide identifications. Avg., average.

FIGURE 2.

Specificity of the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin. a, 293T cell line overexpressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 (F45) was generated and cell lysate (CL) from the cell line were subjected to IP with streptavidin resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. b, HT-1376 cells were transfected with streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 (F45) with or without N-cadherin as indicated and CL were subjected to IP with streptavidin resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. c, the CL from the Fbxo45-overexpressing cell line were subjected to IP with anti-MYCBP2 antibody followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. d, exclusive interaction of N-cadherin (CDH2) with Fbxo45. 293T cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or the indicated streptavidin/HA-tagged (Fbxo45, Fbxw1, Fbxl1) and FLAG-tagged (Fbxw2, Fbxw4, Fbxw5, Fbxw7, and Fbxo22) F-box protein constructs. CL were subjected to IP with anti-FLAG or streptavidin/HA resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. e, reciprocal interaction of N-cadherin with Fbxo45. Whole cell lysate (WCL) from 293T cells stably expressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 were subjected to IP with anti-CDH2 antibody followed by Western blotting with the indicated antibody.

N-cadherin Interacts Specifically with Fbxo45

To assess the specificity of the interaction between N-cadherin and Fbxo45, seven additional F-box proteins were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 2d, among F-box proteins examined, N-cadherin interacted exclusively with Fbxo45. As expected, Fbxo45 was also the only F-box protein that interacted with MYCBP2 and did not interact with CUL1 (Fig. 2d). In contrast, other F-box proteins efficiently immunoprecipitated their respective protein complex components, including CUL1 and Skp1. In reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 2e), endogenous N-cadherin immunoprecipitated Fbxo45, thus providing further support for a direct interaction between the two proteins.

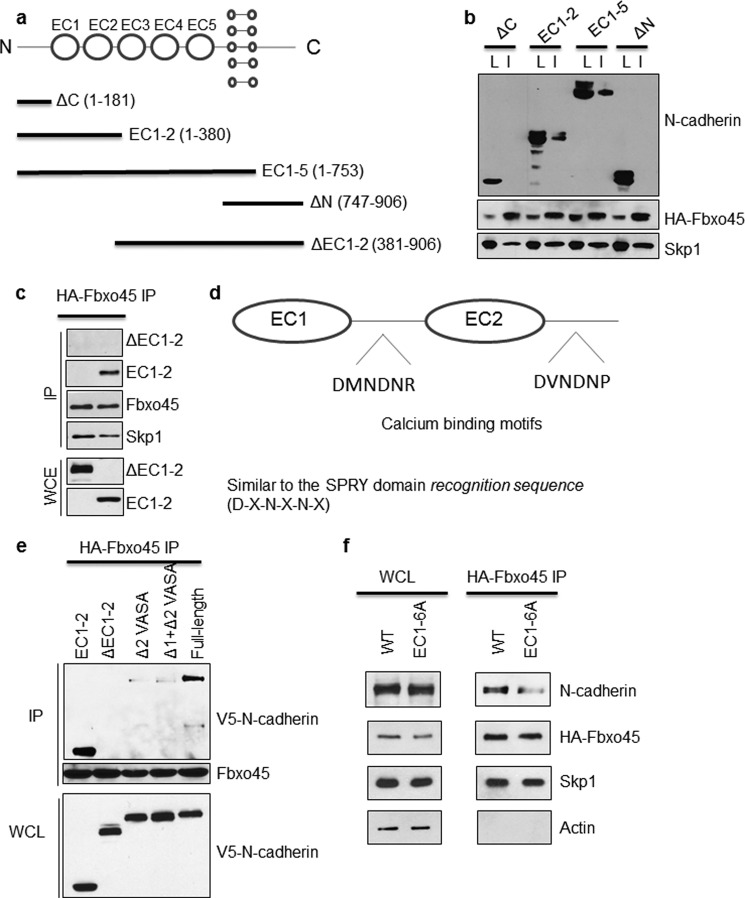

Identification of the Fbxo45-interacting Domains in N-cadherin

As depicted in Fig. 3a, N-cadherin is a membrane protein with five extracellular cadherin (EC) domains involved in cell adhesion. It also has a cytoplasmic C-terminal tail involved in cell signaling and a single transmembrane domain (22, 23). To identify domains necessary for the interaction with Fbxo45, a series of N-cadherin truncation mutants were constructed (Fig. 3a). Co-expression of truncated C-terminal V5-tagged N-cadherin mutants with HA-Fbxo45 followed by Fbxo45 co-immunoprecipitation was performed in 293T cells. Interestingly, our results indicated that neither N-terminal nor C-terminal of N-cadherin is necessary for the interaction (Fig. 3b). However, mutants containing only EC1–5 or EC1–2 of N-cadherin demonstrated interaction with Fbxo45, suggesting that the interacting motifs are mostly confined within the first two EC domains. To confirm that these are critical regions for the interaction of Fbxo45 with N-cadherin, an additional N-cadherin mutant (ΔEC1–2) was constructed, in which only the critical EC1–2 region was deleted. As shown in Fig. 3c, this ΔEC1–2 mutant does not interact at all with Fbxo45, indicating that the interacting motifs reside in the EC1–2 region.

FIGURE 3.

Identification of the Fbxo45 interacting domain in N-cadherin. a, illustration of various C-terminal V5-tagged N-cadherin constructs used for identification of the Fbxo45-interacting domain of N-cadherin. b, WCE from 293T cells stably expressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 were transfected with indicated C-terminal V5-tagged N-cadherin deletion mutants. The whole cell extracts were subjected to IP with HA resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. c, WCE from 293T cells stably expressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 were transfected with indicated V5-tagged N-cadherin deletion mutants. The WCE were subjected to IP with HA resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. d, illustration of putative calcium binding motifs in N-cadherin ECs, which are similar to SPRY domain recognition sequence. e and f, WCE from 293T cells stably expressing streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 were transfected with indicated V5-tagged N-cadherin deletion mutants. The WCE were subjected to IP with HA resin followed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies.

Detailed sequence analysis of this region identified two calcium-binding motifs (DMNDNR and DVNDNP) located at the linker region of EC1 and EC2, respectively (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, both motifs closely resemble the SPRY binding consensus sequence (DXNXNX) (6). To test whether these two consensus motifs are essential for the interaction, two additional mutants were constructed in which either both consensus motifs (Δ1+Δ2 VASA) or a single motif (Δ2 VASA) was deleted. As shown in Fig. 3e, both deletion mutants showed greatly reduced binding to Fbxo45, indicating that the second consensus motif plays a major role in the interaction. To confirm this finding, an additional substitution mutant (EC1–6A mutant) was constructed in which all six amino acids in the first consensus motif were replaced with alanine. Alanine substitution of six residues in the EC1 calcium-binding domain results in diminished interaction with Fbxo45 (Fig. 3f). These data suggest that both motifs in EC1 and EC2 contribute to the interaction.

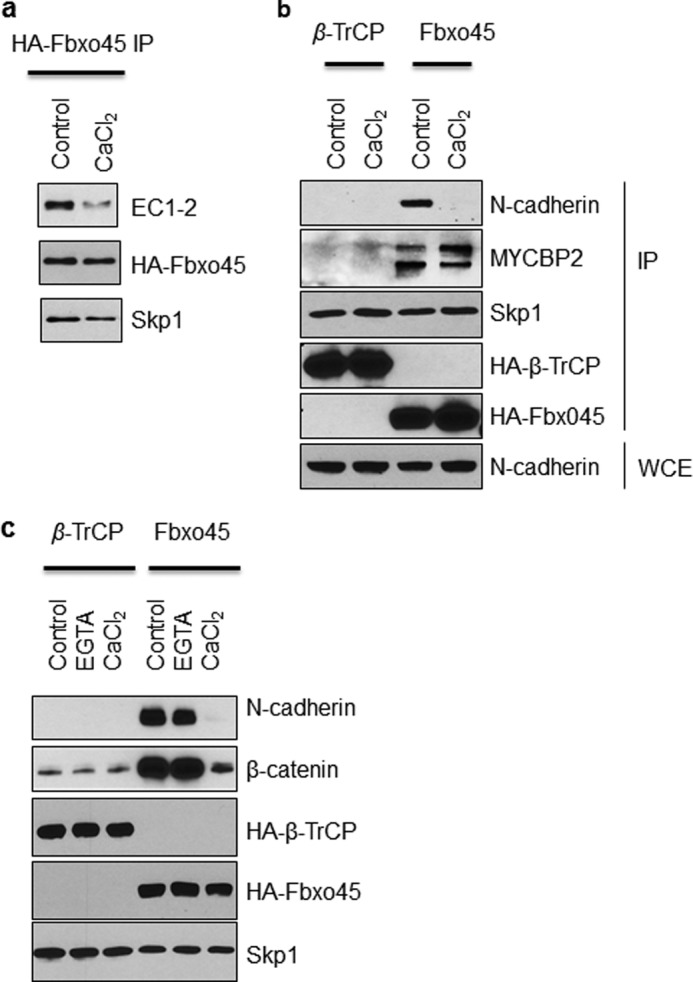

The Interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin Is Sensitive to Calcium

Because the identified Fbxo45-binding motifs in N-cadherin overlap with its calcium binding sites (Fig. 3d), we hypothesized that the SPRY domain of Fbxo45 could compete with calcium for the same binding sites. To test our hypothesis, we performed multiple co-immunoprecipitation experiments in the presence or absence of calcium. As shown in Fig. 4a, in the absence of calcium, Fbxo45 interacted strongly with the EC1–2 mutant, which contains both putative calcium-binding motifs. However, in the presence of 2 mm calcium chloride, the Fbxo45-N-cadherin interaction was greatly reduced (Fig. 4a). To confirm the calcium effect, we repeated the IP experiment with endogenous full-length N-cadherin. As shown in Fig. 4b, the interaction between Fbxo45 and endogenous full-length N-cadherin was greatly diminished following calcium chloride treatment. In contrast, calcium had no effect on the ability of Fbxo45 to interact with MYCBP2 and Skp1 or for β-TrCP to bind Skp1, indicating that the formation of a functional E3 ligase complex is not affected by the presence or absence of calcium (Fig. 4b). To examine whether the calcium effect is specific for the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin, we also examined the effect of calcium on another related F-box protein, β-TrCP. As shown in Fig. 4c, 2 mm calcium chloride had no effect on the interaction of β-TrCP with its known substrate, β-catenin. Next, we examined whether depletion of calcium by treatment with EGTA, a chelator of calcium, affects the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin. As shown in Fig. 4c, addition of 2 mm of EGTA in the binding buffer did not disrupt the strong interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin or the interaction between β-TrCP and β-catenin. Taken together, these results clearly indicate that calcium plays an important role in regulating the specific interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin.

FIGURE 4.

The interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin is sensitive to calcium. a, HT1376 cells were transfected with streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 and C-terminal V5-tagged N-cadherin deletion mutant (EC1–2). WCE were treated with 2 mm CaCl2 or solvent control followed by IP with streptavidin resin. The Western blotting was performed with indicated antibodies. b, 293T cells were transfected with streptavidin/HA-tagged Fbxo45 (F45) or β-TrCP (Fbxw1), and WCE were treated with 2 mm CaCl2 or solvent control followed by IP with streptavidin resin. Western blotting was performed with indicated antibodies. c, the experiment was performed as described in B. 2 mm EGTA was used wherever indicated.

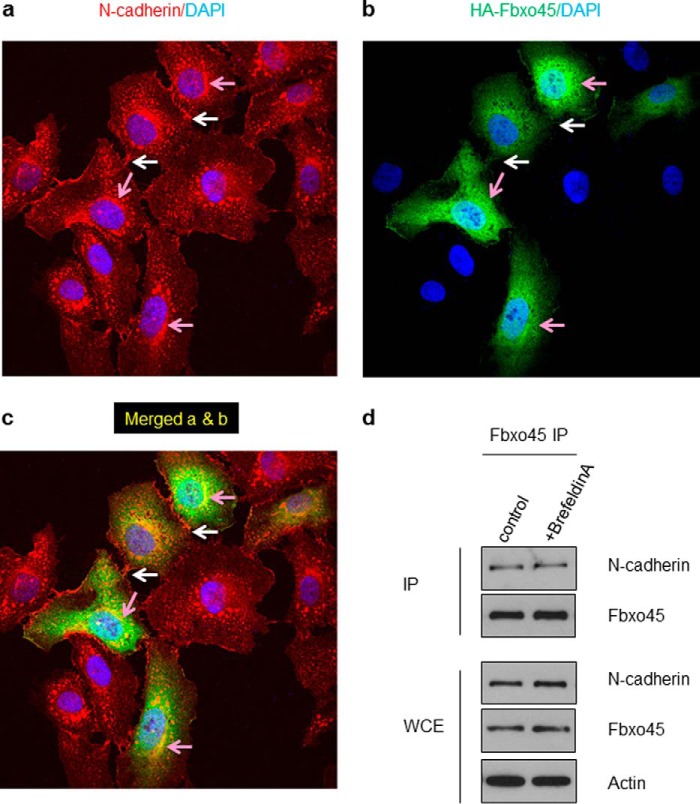

Fbxo45 and N-cadherin Are Co-localized in the Perinuclear and Cytoplasmic Compartments

To determine the subcellular compartment in which the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin occurs, we used fluorescently labeled antibodies against endogenous N-cadherin and transiently transfected HA-tagged Fbxo45 in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were chosen in the immunostaining study instead of 293T cells to take the advantage of the larger cell size of HeLa, more defined adeherens junctions and rich expression of N-cadherin. In addition to intense staining observed in the adherens junctions as expected (indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 5a), there was also strong N-cadherin staining in the areas surrounding the nucleus (pink arrows in Fig. 5a). Transient transfection of HeLa cells with HA-Fbxo45 also showed strong HA staining both in the cytosol and in the perinuclear space (pink arrows in Fig. 5b), but no staining was found in the adherens junctions, indicating that the interaction does not occur in the plasma membrane (white arrows in Fig. 5b). Using confocal microscopy, we confirmed strong co-staining and co-localization of N-cadherin and Fbxo45 in the perinuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (Fig. 5c, pink arrows). However, co-localization in the adherens junctions was not observed (Fig. 5c, white arrows). To further investigate the cellular localization of the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin, cells were treated with brefeldin A (5 μm) for 16 h to block protein transport from the Golgi complex/endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 5d, brefeldin A treatment did not interfere with the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin, further indicating that the interaction occurs inside of the cells.

FIGURE 5.

Co-localization of Fbxo45 and N-cadherin in perinuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. HeLa cells were seeded on glass coverslips and transient transfected with HA-tagged Fbxo45. After 24 h, cells were fixed and immunostained for N-cadherin (a and c) and HA-tagged Fbxo45 (b and c) and subjected to confocal immunofluorescent analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The white arrows indicated localization of N-cadherin in adherens junctions. The pink arrows indicated perinuclear and cytoplasmic areas where Fbxo45 and N-cadherin were colocalized; DAPI was being used as a nuclear counterstain. d, cells transfected with HA-Fbxo45 were treated with vehicle or brefeldin A (5 μm) for 16 h. After treatment, whole cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with HA resin and analyzed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies.

Fbxo45 Protects N-cadherin from Calcium-sensitive Proteolysis

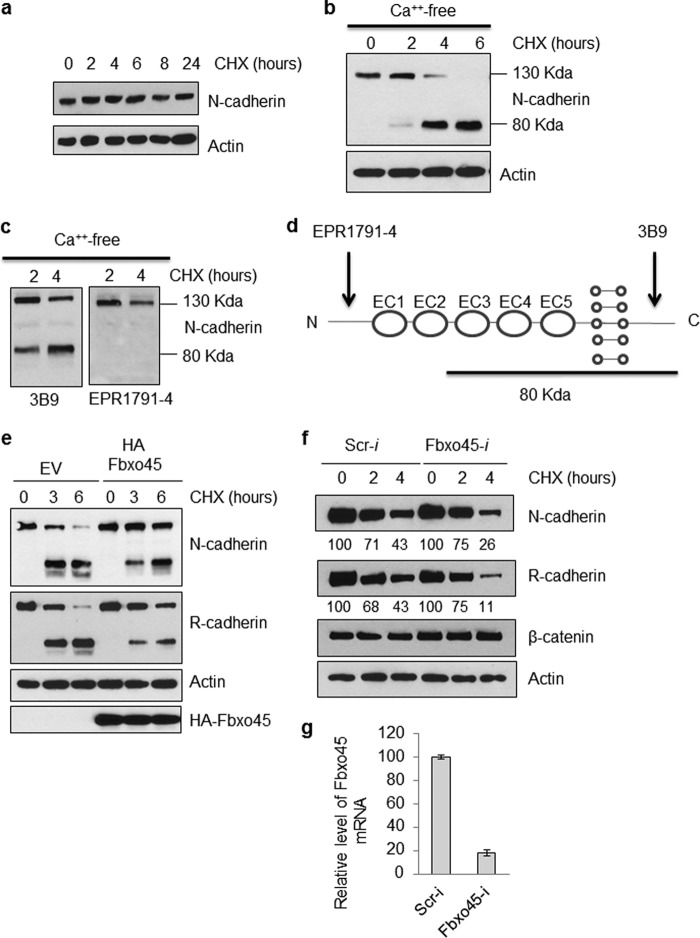

To investigate whether the stability of N-cadherin is affected by Fbxo45, we examined the normal turnover rate of N-cadherin in 293T cells. As shown in Fig. 6a, treatment of 293T cells with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for up to 24 h did not affect the stability of N-cadherin, indicating that it is a very stable protein under normal conditions. The removal of calcium in the media has been shown previously to significantly reduce the stability of N-cadherin as a result of destabilization of the adherens junctions (24, 25). It has been demonstrated that calcium depletion mimics the dynamics of N-cadherin endocytosis and turnover at neuronal adhesion sites (26). N-cadherin endocytosis, degradation, and recycling has been demonstrated to play key roles in neuronal migration and maturation (16, 27, 28). As shown in Fig. 6b, under calcium-free conditions, cycloheximide treatment for 6 h resulted in complete processing of full-length N-cadherin into a smaller 80-kDa fragment. As shown in Fig. 6c-d, whereas both N-cadherin antibodies can detect the full-length protein, the 80-kDa fragment can only be detected with a C-terminal-specific N-cadherin antibody (3B9), but not by an N-terminal-specific antibody (EPR1791–4). This result suggests that the processing occurs at the N-terminal end of N-cadherin in a region near the EC1–2 domain.

FIGURE 6.

Fbxo45 protects N-cadherin from calcium-sensitive proteolysis. a, 293T cells were grown in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. At 80% confluency, cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 100 μg/ml) for the indicated time period. Whole cell lysates were prepared at each time point and analyzed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. b, the 293T cell line overexpressing HA-tagged Fbxo45 and vector control were treated with calcium-free media containing 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for the indicated time. The whole cell extract were examined by Western blotting for indicated antibodies. c, the 293T cells were grew to 80% confluency then treated with calcium-free media for indicated time. The whole cell extracts were examined by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. d, illustration of N-terminal and C-terminal specific antibody recognition sites on N-cadherin. Location of the 80-kDa N-cadherin proteolytic fragment was estimated based on the data from c. e, 293T cells transfected with HA-tagged Fbxo45 or empty vector (EV) were treated with calcium-free media containing 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for indicated time. The whole cell extract were examined by Western blotting for indicated antibodies. f, 293T cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (Scr-i) or Fbxo45 siRNA (Fbxo45-i) for 2 days. Cells were then treated with calcium-free media containing 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for the indicated time. The whole cell extracts were examined by Western blotting for indicated antibodies. Numbers underneath the graph are normalized relative values calculated using the ImageJ program. g, total RNA from aliquotes of cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Scr-i) or Fbxo45 siRNA (Fbxo45-i) for 2 days were isolated. Real time-PCR was carried out to quantitate relative level of Fbxo45 mRNA using GAPDH as a normalization control.

To further investigate whether Fbxo45 plays a role in affecting stability of N-cadherin under calcium-free conditions, we examined the turnover rate of N-cadherin in cells transfected with Fbxo45. As shown in Fig. 6e, cells transfected with Fbxo45 demonstrated enhanced half-life of N-cadherin compared with control cells with reduced generation of N-cadherin cleavage fragments (Fig. 6e). This result is quite unexpected and suggests that N-cadherin is not a proteolytic substrate of Fbxo45. Next, we examined the half-life of N-cadherin in Fbxo45 knockdown 293T cells and observed a faster turnover of N-cadherin (Fig. 6f), suggesting that Fbxo45 may play a protective role in preventing proteolysis of N-cadherin. We also found a similar proteolysis pattern with R-cadherin (Fig. 6, e and f), which is also another confirmed interactor of Fbxo45 (data not shown). R-cadherin is the only classical cadherin that can form heterodimers with N-cadherin due to their structural homology. However, under the same conditions, the half-life of β-catenin, a substrate of β-TrCP but not Fbxo45, was not affected by Fbxo45 silencing (Fig. 6f). The efficiency of Fbxo45 knockdown in 293T cells was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 6g). These results suggest that Fbxo45 may play a similar role as calcium in protecting N-cadherin from proteolysis.

Fbxo45 Is Required for N-cadherin-dependent Neuronal Differentiation

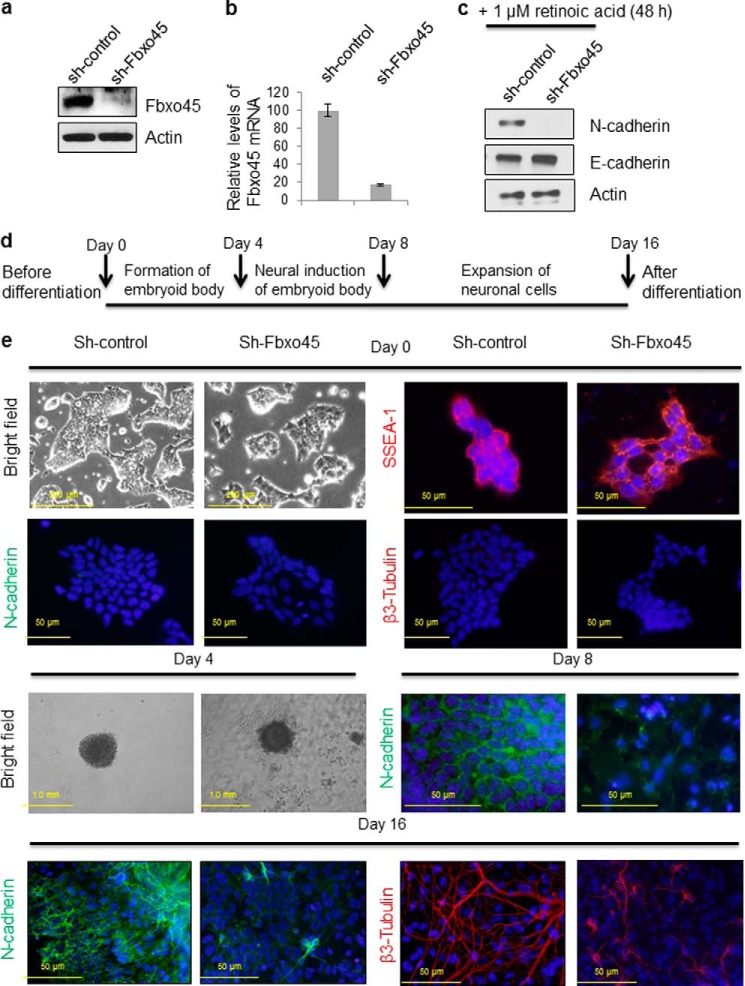

Fbxo45 and N-cadherin are both known to play important roles in neuronal development and synaptogenesis (16, 29). To explore the biological significance of the observed interaction between both proteins, we stably depleted Fbxo45 using shRNA-mediated silencing in a mouse ES cell line to study its effect on N-cadherin. As shown in Fig. 7a, using an Fbxo45 antibody (kindly provided by Dr. Hideyuki Okano) in a Western blot, a 26-kDa band was observed in control mouse ES cell lysates but not in the Fbxo45 knockdown cell lysates, suggesting an effective knockdown of Fbxo45. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR of Fbxo45 mRNA in these cells also confirmed the efficiency of the knockdown (Fig. 7b). To investigate the effect of Fbxo45 silencing on stability of N-cadherin, both control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells were treated with 1 μm of retinoic acid for 48 h to induce expression of N-cadherin. As shown in Fig. 7c, retinoic acid treatment increases N-cadherin accumulation in control cells but not in Fbxo45 knockdown cells, suggesting that Fbxo45 might play a key role in controlling expression and/or protein stability of N-cadherin. Fbxo45-null mice are embryonically lethal, and currently, there is no Fbxo45-inducible knock-out available to perform in vivo experiments. To investigate the role of Fbxo45 on N-cadherin stability and expression in a more biologically relevant setting, we selected the differentiation of mouse ES cells into neurons as a model for studying Fbxo45 knockdown phenotype.

FIGURE 7.

Fbxo45 is required for N-cadherin-dependent neural differentiation. a, mouse ES cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding either shRNA targeting Fbxo45 or non-silencing control shRNA to generate the Fbxo45 knockdown cell line and the control cell line, respectively. The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blotting of whole cell extract with indicated antibodies. b, the knockdown efficiencies were also confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR which is normalized with GAPDH. c, both control and Fbxo45 knockdown mouse ES cells were treated with 1 μm of retinoic acid for 48 h to induce expression of N-cadherin. After treatment, whole cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. d, the timeline of 16-day protocol for mouse ES cell differentiation to neurons. Mouse ES cells are cultured in embryoid body formation medium for 4 days in the absence leukemia inhibitory factor, followed by 4 additional days of incubation in neural inducer solution containing retinoic acid. Cells are subsequently transferred to poly-l-ornithine- and laminin-coated slides and cultured in embryoid body formation medium for another 8 days. e, both control and Fbxo45 shRNA transfected mouse ES cells were allowed to differentiate into neurons using the 16-day protocol described in d. At different stages of differentiation (days 0, 4, 8, and 16), both control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells were examined either by bright field microscopy to observe morphological changes (day 0 and 4) or by immunostaining (days 0, 8, and 16) to monitor changes in key protein markers involved in neuronal differentiation as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

In this model, the mouse ES cells were allowed to differentiate for 16 days into neurons using the method described under “Experimental Procedures” and outlined in Fig. 7d. As shown in Fig. 7e (bright field), prior to initiation of neurogenesis, both control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells displayed typical mouse ES morphological characteristics with tight round colonies and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Both control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells also expressed SSEA-1 (stage-specific embryonic antigen-1, an undifferentiated mouse ES cell marker) but not N-cadherin or β3-tubulin (both neuronal markers). These results suggested that Fbxo45 knockdown does not affect either morphological or biochemical characteristics of undifferentiated mouse ES cells. Four days following the initiation of embryoid body formation, both control and Fbxo45 knockdown cells formed similar spherical cellular aggregate structures, indicating that Fbxo45 also has no apparent effect on the formation of embryoid bodies (Fig. 7e, day 4, bright field). However, at day 8 (4 days after neural induction), the control cells started to express N-cadherin and form tight adherens junctions. In contrast, Fbxo45 knockdown cells only accumulated modest levels of N-cadherin and were loosely connected to each other (Fig. 7e, day 8). These results and those from Fig. 6, e and f, suggest that through its interaction with N-cadherin, Fbxo45 plays a key role in regulating stability of N-cadherin. After differentiation (day 16), cells were stained with fluorescently labeled β3-tubulin (a neuronal marker) antibody and FITC-N-cadherin antibody. As shown in Fig. 7e, day 0, using DAPI as a nuclear counterstain (blue), before differentiation, ES cells expressed little N-cadherin (green) or β3-tubulin (red). However, after differentiation, an elaborate network of β3-tubulin-positive neurites was observed in the scramble shRNA transfected control cells, indicating that ES cells had been successfully differentiated into neurons (Fig. 7e, day 16). Intense staining of N-cadherin was also observed both in adherens junctions and in neuronal processes. In contrast, Fbxo45 knockdown cells only showed sparse staining of β3-tubulin (Fig. 7e, day 16), indicating that the neuronal differentiation was either delayed or incomplete. Similarly, Fbxo45-depleted cells exhibited only weak staining of N-cadherin in adherens junctions and in neuronal processes (Fig. 7e, day 16). These results suggested that Fbxo45 plays an important role in maintaining stability of N-cadherin and in its absence, neuronal N-cadherin dependent differentiation is either delayed or impaired.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described a novel functional interaction between the SPRY-domain containing F-box protein Fbxo45 and N-cadherin. Instead of targeting N-cadherin as an E3 ligase substrate for degradation, Fbxo45 protected N-cadherin from proteolysis. Interestingly, the extracellular domains EC1–2 of N-cadherin, which include the minimal interaction module necessary for N-cadherin interaction with Fbxo45, also contain both the adhesive dimer interface and an essential calcium-binding pocket (30). The two linker regions C-terminal to the first and second extracellular domains contain residues essential for calcium binding (DXNDNX) and bear close resemblance to the consensus SPRY domain binding motifs (Fig. 3d) (31). In this regard, the SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein SPSB2 has been demonstrated to interact with inducible nitric oxide synthase through a SPRY-binding motif in which the Asp-23, Asn-25, and Asn-27 residues in inducible nitric oxide synthase make the major contribution to the binding (6). In our study, the same three corresponding residues in the extracellular domains EC1 and EC2 of N-cadherin (Fig. 3d), which are involved in Fbxo45 binding, were also completely conserved, suggesting that DXNXNX could be a new functional consensus motif for SPRY domain binding. N-cadherin and R-cadherin exhibit high levels of sequence homology (74%) and are the only two classical cadherins that can interact to form heterodimers (32). It is noteworthy that both linker sequences containing the consensus SPRY domain interacting motif were completely conserved between N-cadherin and R-cadherin, and we showed here that both directly interacted with Fbxo45.

To further investigate the direct binding between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin, we performed experiments using HT-1376 cells that do not express endogenous N-cadherin. As shown in Fig. 2b, ectopic expression of N-cadherin in cells allows Fbxo45 to immunoprecipitate N-cadherin without binding to its adherens junction partner β-catenin. These results suggest that the interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin is direct. In experiments to address the cellular localization of binding between N-cadherin and Fbxo45, immunocytochemistry studies in HeLa cells showed that Fbxo45 and N-cadherin co-localize in the perinuclear compartment and cytoplasm, rather than in the adherens juctions (Fig. 5). Interestingly, a similar observation has also been reported for the interaction of Drosophila Hakai (another cytoplasmic E3 ligase) and E-cadherin (33), wherein a cytoplasmic tail deleted E-cadherin still interacts with Drosophila Hakai, suggesting that extracellular domains of E-cadherin participate in an interaction with a cytoplasmic E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Another unanticipated observation from our study is the effect of Fbxo45 in preventing calcium-depletion induced proteolysis of N-cadherin and R-cadherin. It is well established that calcium ions induce conformational changes in cadherins and facilitate dimerization, which allows cadherins to assume a more rigid structure that prevents them from being targeted by proteolytic enzymes (34). It has been reported that during neural development, stability of N-cadherin is regulated through its dynamic endocytic pathways (16). Surface N-cadherin can undergo both constitutive and activity-regulated endocytosis (28). After endocytosis, N-cadherin can be sorted through multiple intracellular trafficking pathways, including degradation to lysosomes, retrograde transport to the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum network, and recycling to the plasma membrane. Our data in Fig. 5 suggested that in the presence of Fbxo45, N-cadherin is mainly colocalized with Fbxo45 in the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum compartment and thus reducing its chance of trafficking through lysosome for degradation. This hypothesis is also consistent with other data in this work, including the fact that low concentrations of calcium inside the cell (35) favor interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin (Fig. 4) and the strong interaction results in enhanced stability of N-cadherin (Fig. 6). In this manner, Fbxo45-mediated retention of N-cadherin in the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum compartment may reduce its trafficking through the lysosome for degradation. These observations suggest that F-box proteins may exhibit unconventional functions through binding-mediated antagonism of proteolysis of their interactors.

Given the observation that both Fbxo45 and N-cadherin play critical roles in neuronal development and synaptogenesis (4, 9, 14, 15). Fbxo45-mediated inhibition of N-cadherin proteolysis could be a plausible mechanism for Fbxo45 regulation of neuronal development. A recent report provides clues on how reduction of N-cadherin can impair the neurogenesis in vitro (35). Using shRNA to N-cadherin and dominant negative N-cadherin overexpression in cell culture, it was shown that N-cadherin can regulate β-catenin-dependent transcriptional activation through activating both Wnt and AKT signaling pathways. Conditional knock-out of N-cadherin also demonstrated that reduced β-catenin signaling resulted in impaired cortical development due to premature neuronal differentiation and increased apoptotic cell death (35). Another recent in vitro study using mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells also demonstrated that forced expression of N-cadherin in mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells substantially enhanced differentiation efficiency, whereas knockdown of N-cadherin by shRNA blocked the neural differentiation (36). These findings are consistent with our data in Fig. 7, which showed that knockdown of Fbxo45 in mouse ES cells reduced N-cadherin stability and impaired the neurogenesis in vitro.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a unique calcium-regulated interaction between Fbxo45 and N-cadherin. Fbxo45 binding inhibited N-cadherin proteolysis and promoted neuronal differentiation. Our study diversifies the mechanistic repertoire of F-box proteins in demonstrating an antagonistic rather than an effector role for intracellular proteolysis. We predict that Fbxo45 will be shown to exhibit yet unidentified regulatory functions based on its recognition of the consensus binding motif present in several cellular proteins (37, 38).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Damian Fermin for normalized spectral abundance factor analysis of MS/MS data. We thank Dr. Stephane Angers for providing the tandem affinity purification tag vector, Dr. Michele Pagano for FLAG-tag F-box protein constructs, and Dr. Hideyuki Okano for Fbxo45 antibody.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DE119249, R01 CA136905 (to K. S. J. E.-J.), and R01 CA140806 (to M. S. L.).

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- EC

- extracellular cadherin

- WCE

- whole cell extract(s)

- β-TrCP

- β-transducin repeat containing protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jin J., Cardozo T., Lovering R. C., Elledge S. J., Pagano M., Harper J. W. (2004) Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes Dev. 18, 2573–2580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cardozo T., Pagano M. (2004) The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liao E. H., Hung W., Abrams B., Zhen M. (2004) An SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex that controls presynaptic differentiation. Nature 430, 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saiga T., Fukuda T., Matsumoto M., Tada H., Okano H. J., Okano H., Nakayama K. I. (2009) Fbxo45 forms a novel ubiquitin ligase complex and is required for neuronal development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 3529–3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu C., Daniels R. W., DiAntonio A. (2007) DFsn collaborates with Highwire to down-regulate the Wallenda/DLK kinase and restrain synaptic terminal growth. Neural Dev 2, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuang Z., Lewis R. S., Curtis J. M., Zhan Y., Saunders B. M., Babon J. J., Kolesnik T. B., Low A., Masters S. L., Willson T. A., Kedzierski L., Yao S., Handman E., Norton R. S., Nicholson S. E. (2010) The SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein SPSB2 targets iNOS for proteasomal degradation. J. Cell Biol. 190, 129–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nishiya T., Matsumoto K., Maekawa S., Kajita E., Horinouchi T., Fujimuro M., Ogasawara K., Uehara T., Miwa S. (2011) Regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by the SPRY domain- and SOCS box-containing proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9009–9019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Filippakopoulos P., Low A., Sharpe T. D., Uppenberg J., Yao S., Kuang Z., Savitsky P., Lewis R. S., Nicholson S. E., Norton R. S., Bullock A. N. (2010) Structural basis for Par-4 recognition by the SPRY domain- and SOCS box-containing proteins SPSB1, SPSB2, and SPSB4. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 389–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tada H., Okano H. J., Takagi H., Shibata S., Yao I., Matsumoto M., Saiga T., Nakayama K. I., Kashima H., Takahashi T., Setou M., Okano H. (2010) Fbxo45, a novel ubiquitin ligase, regulates synaptic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3840–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Niessen C. M., Leckband D., Yap A. S. (2011) Tissue organization by cadherin adhesion molecules: dynamic molecular and cellular mechanisms of morphogenetic regulation. Physiol. Rev. 91, 691–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bloom A. J., Miller B. R., Sanes J. R., DiAntonio A. (2007) The requirement for Phr1 in CNS axon tract formation reveals the corticostriatal boundary as a choice point for cortical axons. Genes Dev. 21, 2593–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vunnam N., Pedigo S. (2011) Calcium-induced strain in the monomer promotes dimerization in neural cadherin. Biochemistry 50, 8437–8444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki S. C., Takeichi M. (2008) Cadherins in neuronal morphogenesis and function. Dev. Growth Differ. 50, S119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinés A., Bernier L. P., McAdam R., Belkaid W., Shan W., Koch A. W., Séguéla P., Colman D. R., Dhaunchak A. S. (2012) N-cadherin prodomain processing regulates synaptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 32, 6323–6334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka H., Shan W., Phillips G. R., Arndt K., Bozdagi O., Shapiro L., Huntley G. W., Benson D. L., Colman D. R. (2000) Molecular modification of N-cadherin in response to synaptic activity. Neuron 25, 93–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawauchi T., Sekine K., Shikanai M., Chihama K., Tomita K., Kubo K., Nakajima K., Nabeshima Y., Hoshino M. (2010) Rab GTPases-dependent endocytic pathways regulate neuronal migration and maturation through N-cadherin trafficking. Neuron 67, 588–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujita Y., Krause G., Scheffner M., Zechner D., Leddy H. E., Behrens J., Sommer T., Birchmeier W. (2002) Hakai, a c-Cbl-like protein, ubiquitinates and induces endocytosis of the E-cadherin complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang J. Y., Zong C. S., Xia W., Wei Y., Ali-Seyed M., Li Z., Broglio K., Berry D. A., Hung M. C. (2006) MDM2 promotes cell motility and invasiveness by regulating E-cadherin degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 7269–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qian L. W., Greene W., Ye F., Gao S. J. (2008) Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus disrupts adherens junctions and increases endothelial permeability by inducing degradation of VE-cadherin. J. Virol. 82, 11902–11912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sahasrabuddhe A.A., C. X., Chung F., Velusamy T., Lim M.S., Elenitoba-Johnson K.S.J. (2013) Oncogenic Y641 mutations in EZH2 prevent Jak2/βTrCP-mediated degradation. Oncogene 10.1038/onc.2013.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sahasrabuddhe A. A., Dimri M., Bommi P. V., Dimri G. P. (2011) betaTrCP regulates BMI1 protein turnover via ubiquitination and degradation. Cell Cycle 10, 1322–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kowalczyk A. P., Nanes B. A. (2012) Adherens junction turnover: regulating adhesion through cadherin endocytosis, degradation, and recycling. Subcell Biochem. 60, 197–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ratheesh A., Yap A. S. (2012) A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lelièvre E. C., Plestant C., Boscher C., Wolff E., Mège R. M., Birbes H. (2012) N-cadherin mediates neuronal cell survival through Bim down-regulation. PLoS One 7, e33206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tran N. L., Adams D. G., Vaillancourt R. R., Heimark R. L. (2002) Signal transduction from N-cadherin increases Bcl-2. Regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway by homophilic adhesion and actin cytoskeletal organization. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32905–32914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marrs G. S., Theisen C. S., Brusés J. L. (2009) N-cadherin modulates voltage activated calcium influx via RhoA, p120-catenin, and myosin-actin interaction. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 40, 390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawauchi T. (2012) Cell Adhesion and Its Endocytic Regulation in Cell Migration during Neural Development and Cancer Metastasis. International journal of molecular sciences 13, 4564–4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tai C. Y., Mysore S. P., Chiu C., Schuman E. M. (2007) Activity-regulated N-cadherin endocytosis. Neuron 54, 771–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu X., Li W. E., Huang G. Y., Meyer R., Chen T., Luo Y., Thomas M. P., Radice G. L., Lo C. W. (2001) Modulation of mouse neural crest cell motility by N-cadherin and connexin 43 gap junctions. J. Cell Biol. 154, 217–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vunnam N., McCool J. K., Williamson M., Pedigo S. (2011) Stability studies of extracellular domain two of neural-cadherin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 1841–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuang Z., Yao S., Xu Y., Lewis R. S., Low A., Masters S. L., Willson T. A., Kolesnik T. B., Nicholson S. E., Garrett T. J., Norton R. S. (2009) SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein 2: crystal structure and residues critical for protein binding. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 662–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Inuzuka H., Miyatani S., Takeichi M. (1991) R-cadherin: a novel Ca2+-dependent cell-cell adhesion molecule expressed in the retina. Neuron 7, 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaido M., Wada H., Shindo M., Hayashi S. (2009) Essential requirement for RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase Hakai in early embryonic development of Drosophila. Genes Cells 14, 1067–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nagar B., Overduin M., Ikura M., Rini J. M. (1996) Structural basis of calcium-induced E-cadherin rigidification and dimerization. Nature 380, 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang J., Shemezis J. R., McQuinn E. R., Wang J., Sverdlov M., Chenn A. (2013) AKT activation by N-cadherin regulates β-catenin signaling and neuronal differentiation during cortical development. Neural Dev. 8, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Su H., Wang L., Huang W., Qin D., Cai J., Yao X., Feng C., Li Z., Wang Y., So K. F., Pan G., Wu W., Pei D. (2013) Immediate expression of Cdh2 is essential for efficient neural differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 10, 338–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woo J. S., Suh H. Y., Park S. Y., Oh B. H. (2006) Structural basis for protein recognition by B30.2/SPRY domains. Mol. Cell 24, 967–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Foster M. W., Thompson J. W., Forrester M. T., Sha Y., McMahon T. J., Bowles D. E., Moseley M. A., Marshall H. E. (2013) Proteomic analysis of the NOS2 interactome in human airway epithelial cells. Nitric Oxide 34, 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]