Abstract

Skeletal muscle fibres are large and highly elongated cells specialized for producing the force required for posture and movement. The process of controlling the production of force within the muscle, known as excitation–contraction coupling, requires virtually simultaneous release of large amounts of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) at the level of every sarcomere within the muscle fibre. Here we imaged Ca2+ movements within the SR, tubular (t-) system and in the cytoplasm to observe that the SR of skeletal muscle is a connected network capable of allowing diffusion of Ca2+ within its lumen to promote the propagation of Ca2+ release throughout the fibre under conditions where inhibition of SR ryanodine receptors (RyRs) was reduced. Reduction of cytoplasmic [Mg2+] ([Mg2+]cyto) induced a leak of Ca2+ through RyRs, causing a reduction in SR Ca2+ buffering power argued to be due to a breakdown of SR calsequestrin polymers, leading to a local elevation of [Ca2+]SR. The local rise in [Ca2+]SR, an intra-SR Ca2+ transient, induced a local diffusely rising [Ca2+]cyto. A prolonged Ca2+ wave lasting tens of seconds or more was generated from these events. Ca2+ waves were dependent on the diffusion of Ca2+ within the lumen of the SR and ended as [Ca2+]SR dropped to low levels to inactivate RyRs. Inactivation of RyRs allowed re-accumulation of [Ca2+]SR and the activation of secondary Ca2+ waves in the persistent presence of low [Mg2+]cyto if the threshold [Ca2+]SR for RyR opening could be reached. Secondary Ca2+ waves occurred without an abrupt reduction in SR Ca2+ buffering power. Ca2+ release and wave propagation occurred in the absence of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. These observations are consistent with the activation of Ca2+ release through RyRs of lowered cytoplasmic inhibition by [Ca2+]SR or store overload-induced Ca2+ release. Restitution of SR Ca2+ buffering power to its initially high value required imposing normal resting ionic conditions in the cytoplasm, which re-imposed the normal resting inhibition on the RyRs, allowing [Ca2+]SR to return to endogenous levels without activation of store overload-induced Ca2+ release. These results are discussed in the context of how pathophysiological Ca2+ release such as that occurring in malignant hyperthermia can be generated.

Key points

Prolonged Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ waves have been observed in mammalian skeletal muscle upon reducing the normal resting inhibition of the ryanodine receptor (RyR)/Ca2+ release channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) by lowering cytoplasmic [Mg2+] ([Mg2+]cyto). The mechanism driving Ca2+ release under these conditions may have pathophysiological implications but is poorly understood.

The lowering of [Mg2+]cyto induced a leak of Ca2+ from the SR that triggered a local reduction of the SR Ca2+ buffering power to induce the rise in [Ca2+]SR, an intra-SR Ca2+ transient. Prolonged Ca2+ transients always developed following this event and evolved as propagating Ca2+ waves. No classical hallmarks of cytoplasmic Ca2+ propagation mechanisms were observed in conjunction with these waves.

In conjunction with the spread of Ca2+ release, Ca2+ was observed to diffuse through the SR away from the site of the intra-SR Ca2+ transient. Ca2+ release was sustained by the action of SR Ca2+ pumps, presumably to maintain [Ca2+]SR above an inactivation threshold for closure of the RyRs. Inactivation of prolonged Ca2+ release allowed [Ca2+]SR to recover to threshold for activation of further Ca2+ waves, which were always briefer in duration than the initial Ca2+ release transients, consistent with a reduced SR Ca2+ buffering capacity.

These observations reveal activation of Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle by [Ca2+]SR in the absence of the normal resting inhibition of the RyR and changes in voltage. Diffusion of Ca2+ within SR promotes propagation of Ca2+ release.

Introduction

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is a highly specialized organelle in both cardiac and skeletal muscle for Ca2+ storage and rapid regulation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. The SR forms a junction with the internalization of the plasma membrane, known as the tubular (t-) system, at every sarcomere. As this junction forms regularly across the fibre it allows the voltage control of Ca2+ release to be conducted, as well as other mechanisms, such as store-operated Ca2+ entry (Edwards et al. 2010b), uniformly across all sarcomeres with local control (Melzer et al. 1995).

The initiating step in excitation–contraction coupling is the spread of excitation, controlled by the sarcolemma (outer plasma membrane of the muscle) and the t-system network within the fibre. It is known that the t-system network is intricate and electrically connected in all directions within the fibre (Edwards et al. 2012; Jayasinghe & Launikonis, 2013). There is reason to suspect that the SR is a similarly connected network also. Fluorescent dyes trapped within the SR diffuse across many sarcomeres in skeletal muscle (Ziman et al. 2010). Furthermore the similarly structured cardiomyocytes have been shown able to allow Ca2+ to diffuse within the SR for virtually the length of the cell (Wu & Bers, 2006; Bers & Shannon, 2013). It follows that Ca2+ is most likely diffusible through the SR network of skeletal muscle.

If the SR is a connected network along a skeletal muscle fibre, the potential for Ca2+ moving long distances within the SR exists, which may have implications for normal skeletal muscle function and pathophysiology. Evidence in favour of potential pathophysiological Ca2+ release mechanisms having underlying causes at the level of Ca2+ handling alterations within the SR do exist. Early evidence of this was the observation of an intra-SR Ca2+ transient that appeared as the driving force for a large and prolonged release of Ca2+ in frog muscle, elicited when cytoplasmic [Mg2+] ([Mg2+]cyto) was lowered (Launikonis et al. 2006). This result is significant as the [Mg2+]cyto levels are critical to the normal inhibition of the SR ryanodine receptors (RyR)/Ca2+ release channels (Smith et al. 1986; Lamb & Stephenson, 1991, 1994; Jacquemond & Schneider, 1992; Lamb, 1993; Laver et al. 1997). The intra-SR transient was suggested to be induced by a change in Ca2+ buffering capacity of the resident SR Ca2+ buffer calsequestrin (CSQ) (Park et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006; Royer & Rios, 2009).

The coupling of lowered [Mg2+]cyto and a large release of Ca2+ is significant in our understanding of the pathophysiology of diseases such as malignant hyperthermia (MH). MH is a hypermetabolic response to volatile anaesthetics or succinylcholine in the operating theatre or a response to an increase in body temperature that can be fatal. A large release of Ca2+ underlines the condition, where muscles go rigid for a long period, generating heat and protons that enter the body's circulation (Hopkins, 2011; Bandschapp & Girard, 2012). Susceptibility to this condition is through one of many mutations in the RyR or associated proteins (MacLennan et al. 1990; Fujii et al. 1991). Muscle fibres isolated from biopsies of people known to be MH susceptible or MH non-susceptible, when challenged with halothane (a volatile anaesthetic), were found to respond with a release of Ca2+. The sensitivity to halothane was inversely related to [Mg2+]cyto and the conclusion from a series of papers (Duke et al. 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2010) was that defective Mg2+ regulation of the RyR was causative for MH (Steele & Duke, 2007), consistent with previous studies (Lamb, 1993; Laver et al. 1997; Owen et al. 1997).

Importantly, in many cases Steele and colleagues observed that the response of the MH susceptible and MH non-susceptible muscle fibres to low [Mg2+]cyto and halothane was a wave of Ca2+ release along the fibre, at a rate in the order of tens of μm s−1 (Duke et al. 2010). We hypothesized that the cytoplasmic Ca2+ wave may be driven by a wave of Ca2+ inside the SR network if the initial release of Ca2+ was localized and driven by an intra-SR Ca2+ transient. An intra-SR Ca2+ transient has recently been shown to occur during a uniform, long depolarization in the muscle of a mouse model of MH (Manno et al. 2013) and our previous work showed some evidence of low Mg2+-induced Ca2+ release starting in a local manner and spreading longitudinally along skeletal muscle fibres (Edwards et al. 2010a,b2010b, 2011). Our aim here was to determine whether a locally activated intra-SR Ca2+ transient could underlie a Ca2+ transient throughout the SR, a possible mechanism driving pathophysiological Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle.

Methods

All experimental methods using rodents were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at the University of Queensland, and conform to the principles of the UK regulations, as described in Drummond (2009). C57/BL6 mice and Wistar rats (University of Queensland Biological Resources, Brisbane) were killed by cervical dislocation and the extensor digitorum longus muscles were rapidly excised. Muscles were then placed in a Petri dish under paraffin oil above a layer of Sylgard. Segments of individual fibres were then isolated and mechanically skinned to remove the surface membrane completely. Skinned fibres were transferred to a custom-built experimental chamber with a coverslip bottom, where they were bathed in an ‘internal solution’. In some cases, skinned fibres were exposed to 10 μm fluo-5N-AM cell permeant form at 30°C for 30 min, followed by >10 min at room temperature in internal solution before imaging to trap the dye in the SR (Kabbara & Allen, 2001). For some experiments fluo-5N salt was trapped in the sealed t-system as described (Launikonis et al. 2003). Briefly, small bundles of fibres from extensor digitorum longus muscles were isolated and exposed to a ‘dye solution’ while still intact and time was allowed for the dye to diffuse into the t-system.

Solutions

The ‘dye solution’ was a Na+-based physiological solution that was applied before skinning the mouse fibres and contained (mm): NaCl, 145; KCl, 3; CaCl2, 2.5; MgCl2, 2; fluo-5N salt, 1; and Hepes, 10 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The composition of internal solutions used in this study are shown in Table 1. ‘Standard’ solutions were used to load the SR and t-system with Ca2+ or pre-equilibrate fibres to determined levels of Ca2+ or EGTA. ‘Low Mg2+ solution’ was designed to induce cell-wide SR Ca2+ release (Lamb & Stephenson, 1994), which was followed by release inactivation and resequestration of SR Ca2+ (Launikonis et al. 2006). In some experiments, ‘medium EGTA release’ or ‘high EGTA release’ was used following pre-equilibration in ‘medium EGTA’ or ‘high EGTA’ solution, respectively, to induce a thorough release of Ca2+ from the SR. Note that 50 μm cyclopianzonic acid was added to ‘medium EGTA release’ solution. n-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide was added to all solutions to inhibit contraction. All chemicals were from Sigma (Sydney, NSW, Australia) unless otherwise stated.

Table 1.

Internal solution composition

| Solution | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | EGTA | HDTA | Caffeine | Rhod-2 | Fura-red |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard-0 Ca2+ | 0 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Standard-100 Ca2+ | 0.0001 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Standard-200 Ca2+ | 0.0002 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Standard-800 Ca2+ | 0.0008 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild inhibitory | 0.0001 | 0.4 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Medium EGTA | 0 | 1 | 10 | 40 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Medium EGTA release | 0 | 0.01 | 10 | 40 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 |

| High EGTA | 0.0001 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Low Mg2+ | 0 | 0.01 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| High EGTA release | 0 | 0.01 | 50 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0.05 |

All concentrations are in mm. Additionally, solutions contained (mm): K+, 126; Na+, 36; creatine phosphate, 10; ATP, 8; Hepes, 90; n-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide, 0.05. Mg2+ was added as MgO and Ca2+ was added as Ca2CO3. Note that ‘Ca2+’ and ‘Mg2+’ refer to the free ionic compositions in solution and that the total concentrations of Mg and Ca were much higher. Osmolality was adjusted to 290 ± 10 mosmol kg−1 with sucrose. Note also that HDTA2− (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) is used as the anion replacement of EGTA2−. pH was adjusted to 7.1 with KOH in all solutions.

The consequence of increasing the buffering capacity of the bathing solution from 1 to 50 mm EGTA can be described by the predicted dynamic effect on its length constant, μ, which approximates the distance that Ca2+ can freely travel from a source, such as the RyRs, before it binds to the buffer (Naraghi & Neher, 1997). The distance for solutions buffered by EGTA, μE, is approximately: (DE/[EGTA].kE)0.5, where DE is the diffusion coefficient for EGTA, 220 μm2 s−1; and kE is the Ca2+ binding rate constant to EGTA, 1.5 μm s−1. It follows that the μE for 1 and 50 mm EGTA is 383 and 54 nm, respectively.

Confocal imaging

The experimental chamber containing a skinned fibre was placed above a water immersion objective (40×, NA 0.9) of the confocal laser scanning system (FV1000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Simultaneous acquisition of two images (F1 and F2) was achieved by line-interleaving of two excitation wavelengths (488 and 543 nm) with a group scanning speed of 2 ms line−1 while collecting emitted light in two emission ranges (500–540 nm and 562–666 nm), respectively. In experiments where fura red replaced rhod-2 as the [Ca2+]cyto indicator, the 488 nm laser line excited both fluo-5N and fura-red with the fluorescent emission collected in the range 500–540 nm and 560–666 nm, respectively. Imaging was performed at 21–24°C.

Confocal image analysis

All imaging in this study was performed in xy mode, in most cases at 0.2056 μm pixel distance and 2.162 ms line interval. xy scanning lent itself to a method of image analysis illustrated in Fig. 1, in a fashion that has been described previously (Launikonis & Rios, 2007). Briefly, the scanning line, defining the variable x, was transversal to the fibre axis. xy imaging provided information in two dimensions of space and in a temporal dimension as well, along the y axis. The temporal evolution of [Ca2+]-dependent fluorescence signals could be derived by averaging, over x within the borders of the preparation, to obtain a function of y that mapped proportionally to elapsed time. The correspondence factor between t and y is determined by the scanning speed. For the approach to be valid, the fibre must be homogeneous along the y-axis, which usually can be decided by inspection of the xy image at rest. Uniformity is considered reasonable when changes of R(y) in the resting fibre are minor relative to the magnitude and rate of the dynamic changes R(y(t)) = G(t) of interest during stimulated release. For instance, in the image indicated at ‘61 s’ in Fig. 1 the spatially averaged profile R(y(t)) shows only minor irregularities. This degree of uniformity is sufficient if the goal is to reveal greater, faster or longer-lasting components in G(t). This is observed as Ca2+ waves propagate into this section of the fibre (image at ‘62 s’). The event illustrated clearly satisfies this criterion.

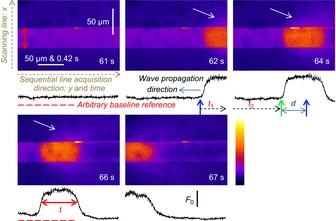

Figure 1. Image acquisition and analysis.

xyt imaging of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence from rhod-2 containing internal bathing solution surrounding a skinned fibre from mouse. The scanning line of the laser was transversal to the fibre axis, x, with each line (512) sequentially acquired along the long axis of the fibre, y. The spatially averaged profiles of F/F0 from within the borders of the preparation, indicated by vertical, double red arrows in first image, are shown below each image in black. Note that y maps proportionally to time and that each image was acquired at a rate of 1.622 s but the timestamp placed in the bottom right-hand corner of each image is rounded to the nearest second (these images are a subset of the experiment displayed in Fig. 7A, with corresponding time-stamp). Ca2+ waves pass along the fibre within the imaging region across four consecutive images. The conversion of the spatially averaged profile of fibre from y to t allows the determination of Ca2+ wave propagation rate (d/t1+t2) and full duration at half magnitude (t) with a temporal resolution two orders of magnitude better than that of the xyt scanning mode (1.662 s). The white arrows indicate diffusion of Ca-rhod-2 from the preparation during Ca2+ release.

This mode of analysis of xyt imaging allows us to determine the propagation rate and full duration at half-magnitude (FDHM) of the Ca2+ waves observed in this study. In this example (Fig. 1) the Ca2+ wave propagates from right-to-left (indicated on image, ‘62 s’). The blue vertical arrow on the image ‘62 s’ marks the position of the Ca2+ wave front. The wave progresses forward in the next image, at ‘64 s’. The front of the wave is marked by the green vertical arrow in the ‘64 s’ image while the blue arrow is reproduced on this image to show the distance the wave front has propagated. The calculation of the propagation rate of the wave front is the distance, d, divided by the time, t1 + t2, which is the time taken for the scanning laser to reach the front of the Ca2+ wave in the images at 64 s from the time of the wave front in the image at 62 s. The propagation rate observed in Fig. 1 was 46.4 μm/1.259 s = 36.8 μm s−1.

The FDHM can be deduced from the profile R(y(t)), as indicated by the horizontal, red double arrows in the image marked ‘66 s’. The FDHM in this image is 0.58 s. Where Ca2+ waves persisted for periods much longer than a second, the FDHM can be simply derived from the spatially averaged profile, for example in Fig. 2A.

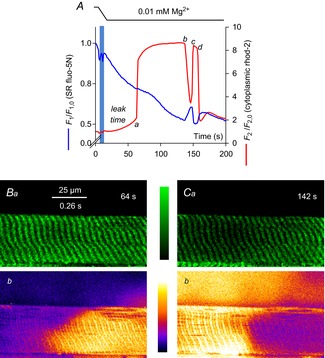

Figure 2. SR and cytoplasmic Ca2+ during prolonged Ca2+ release.

The spatially averaged fluorescence values for each frame in an xyt series of SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence (blue line) and cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence (red line) from a rat skinned fibre during the lowering of [Mg2+]cyto is plotted in A. The interval of solution change is indicated by the horizontal bars at top and the vertical blue bar on the profile. a–d refer to the Ca2+ release and termination of release events. These events are described in the text and analysed in Fig. 6. Lowering [Mg2+]cyto causes Ca2+ to initially leak from SR, marked leak time and indicated by the rise in cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence up to the position marked a (see Fig. 5). Images from the rise (B) and decline (C) of the Ca2+ transient induced by lowering [Mg2+]cyto are shown. The background of the fluo-5N fluorescence image has been subtracted and the image median filtered. Time stamp in top right-hand corner of fluo-5N fluorescence image corresponds to that of the spatially averaged values of rhod-2 and fluo-5N fluorescence shown in A. A ‘halo’ of Ca2+ released from the fibre was observed in C (see Methods). SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

A feature of imaging Ca2+ release in skinned fibres is the ejection of released Ca2+ from the fibre to the surrounding bathing solution (note the cytoplasm of skinned fibres is open to the bathing solution). This can be observed in Fig. 1 as the Ca2+ wave passes along the images marked ‘62 s’–‘66 s’ by the white arrows. This is Ca2+ rhod-2 diffusing from the fibre, which we describe as the ‘halo’ of the Ca2+ release event. The magnitude of the halo will be dependent on the combination of the SR Ca2+ release flux, the Ca2+ buffering power of the internal bathing solution and that of the fibre (largely the SR Ca2+ pump). ‘Ca2+ halos’ surrounding Ca2+ releasing sites in skinned fibres are observed in Figs 3 and 10. Note the [Ca2+] and duration of the halos differ across these examples.

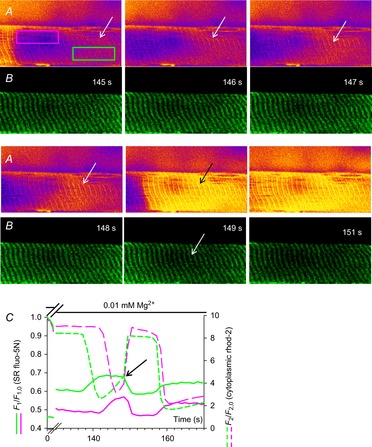

Figure 3. Following prolonged Ca2+ release resequestered cytoplasmic Ca2+ provides the driving force for briefer Ca2+ transients to start.

Selected images cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence (A) and SR trapped fluo-5N fluorescence (B) following the exchange of standard internal bathing solution for low [Mg2+]cyto solution bathing a rat skinned fibre. The spatially restricted fluorescence values of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence and SR trapped fluo-5N fluorescence of the fibre bound by the pink and green boxes (indicated in the first image in A) are plotted against time in C for a selected section of this experiment (full experiment presented in Fig. 2). The white arrows in B from time-points 145 s to 148 s indicate a region of increasing cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence intensity while the SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence remains relatively high and constant. The black arrow in A at time-point 149 s indicates a rapid increase in cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence compared to the previous 3 s and a rapid decline in SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence. These events in this restricted region of the fibre are shown in profile in the green lines in C. The black arrow in C indicates the change in rate of increase of rhod-2 cytoplasmic fluorescence that correlates with net SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence turning negative. The profiles in the pink line in C represents the fluorescence values of SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence and cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence from the area marked with the pink box in A. A delay in Ca2+ movements is observed between the two locations (C). SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 10. Propagation of Ca2+ waves is not driven by a cytoplasmic mechanism.

Selected cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence image from Fig. 8 has been enlarged. The base of the first white arrow indicates the front of the Ca2+ wave, which is in the central region of the fibre, and the point of the arrow indicates a possible direction of propagation of the wave front. The second arrow indicates where the front of the wave meets the fibre edge. The distance, y, between the arrowheads, which also maps proportionally to t is used to determine the propagation rate if cytoplasmic propagation of Ca2+ is assumed to spread the wave front across the short axis of the fibre. Under this assumption, the rate of propagation would be close to 1 mm s−1.

Results

This section includes images of the evolution of cytoplasmic Ca2+-dependent fluorescence with, in most cases, simultaneously recorded images of SR-trapped Ca2+-dependent fluorescence during voltage-independent Ca2+ release induced by lowering the [Mg2+]cyto. Distinct cytoplasmic Ca2+ release events are observed under this stimulus. To probe what was driving the release of Ca2+ under this stimulus, cytosolic Ca2+ buffering capacity was changed, ionic conditions were localised across single preparations and the local Ca2+ leak from the SR was sampled by monitoring t-system trapped Ca2+-sensitive dye.

Prolonged Ca2+ release, [Ca2+]SR and changes in SR Ca2+ buffering power induced by lowering [Mg2+]cyto

Simultaneously acquired images of SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence and cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence are shown in the spatially averaged profile in Fig. 2A. This figure displays the temporal evolution of [Ca2+]SR and [Ca2+]cyto determined by averaging the fluorescence from within the borders of the preparation in each consecutive xy image. Note that the membrane potential is held constant during the experiment by the maintenance of [K+]cyto and [Na+]cyto (Table 1; Lamb & Stephenson, 1994).

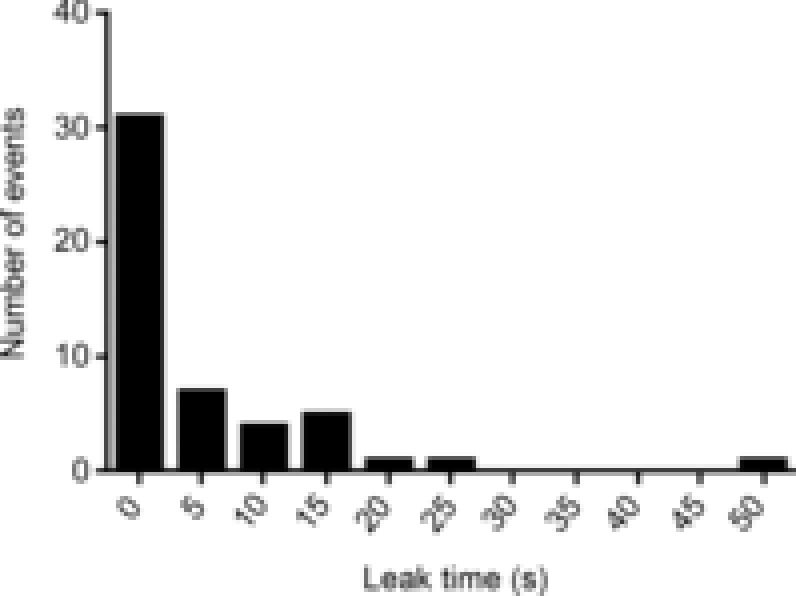

Changing the internal bathing solution from standard solution containing 100 nm Ca2+ and 1 mm EGTA to low Mg2+ solution containing 0.01 mm Mg2+, 1 mm EGTA and no added Ca2+ caused the release of Ca2+ from the SR. The release of Ca2+ from SR following the lowering of [Mg2+]cyto occurred after a delay of ∼50 s. This delay is indicated as ‘leak time’ on Fig. 2A. The cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence signal is increased slowly during this period reaching values higher than that in the standard solution.

The fluo-5N fluorescence signal from the SR shows a steady decline in the same period (‘leak time’; Fig. 2A). This decline can be attributed to: (i) a net loss of Ca2+ from the SR, or (ii) a bleaching of the fluo-5N by the scanning lasers of the confocal microscope or a combination of both. The fluorescence profile of fluo-5N (t) has not been corrected for bleaching to avoid the probable introduction of artefacts to this profile. Net changes in fluo-5N fluorescence are observable over t allowing the temporal evolution of [Ca2+]SR to be described without such a correction. In previous work with compartmentalized fluorescent dyes, rates of bleaching lower than that observed here (Fig. 2) were recorded (Launikonis & Stephenson, 2002). The rate of bleaching can vary and will be dependent on the scanning load, a combination of the scanning laser intensity and the duration of scanning. In the SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence signal displayed in Fig. 2, there is more intense bleaching than in the previously reported work with compartmentalized dyes because here scanning was continuous unlike the work of Launikonis & Stephenson (2002). Therefore, we can expect the declining rate of fluorescence of the compartmentalized dye in Fig. 2 is probably largely due to bleaching. This would suggest that the SR is able to maintain [Ca2+]SR during the ‘leak time’ in the absence of normal cytoplasmic RyR inhibition. (This assumption is consistent with result derived below from Fig. 3).

Following the leak phase, the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient rose rapidly while [Ca2+]SR showed a net increase (Fig. 2A at ∼64 s, marked by ‘a’). A net increase of [Ca2+]SR is clear immediately after the large release of SR Ca2+ from the changes in fluo-5N fluorescence (t) (see also Fig. 3).

Later in the Ca2+ transient, from about 100 to 140 s, the net fluo-5N fluorescence declined, indicating [Ca2+]SR was declining while [Ca2+]cyto remained constant over this time.

At the point marked ‘b’ on Fig. 2A the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient declined sharply over a few seconds concurrently with a sharp net recovery of fluo-5N fluorescence.

The fluorescence images of rhod-2 and fluo-5N fluorescence at the start of the Ca2+ release from the SR is shown in Fig. 2B. Note that the y-axis of the fluorescence image maps proportionally to time along the long axis of the fibre (see Methods and Fig. 1; this is indicated by the common spatial and temporal scale bar on Fig. 2B). The rhod-2 fluorescence image shows that Ca2+ release started during the acquisition of this image (Fig. 2Bb). In the simultaneously acquired fluo-5N fluorescence image no net change was observed at the increase in [Ca2+]cyto even though [Ca2+]SR was the source of the Ca2+ release. This would suggest there must be a source of Ca2+ inside SR to sustain [Ca2+]SR during release.

Rhod-2 and fluo-5N fluorescence images are shown in Fig. 2C. These images show the point the Ca2+ transient had declined about 50% of its peak amplitude, at 142 s. The rhod-2 fluorescence image shows the Ca2+ transient that was terminating abruptly (in contrast to a ‘graded’ decline, see Edwards et al 2010b); i.e. it declined suddenly and this decline tracked along the axis of the fibre, from right-to-left, as the image is presented. The Ca2+ halo (see Methods) around the fibre is also consistent with the release of Ca2+ from the SR ending in a highly spatially segregated manner where it declined in intensity around the section of the fibre that is no longer releasing Ca2+. The simultaneously acquired fluo-5N fluorescence signal from the SR showed an inversely proportional increase in intensity to the rhod-2 signal from the cytoplasm. This indicated that as Ca2+ release terminated locally that there was a spatiotemporally coupled net recovery of [Ca2+]SR (Fig. 2C).

At the point of maximal recovery of fluo-5N fluorescence and termination of the prolonged Ca2+ transient, marked by ‘c’ on Fig. 2A, a second Ca2+ transient rose at a similar rate as Ca2+ release did previously at the point marked ‘a’. In contrast to the first Ca2+ transient the fluo-5N fluorescence signal indicated a rapid decline in [Ca2+]SR. This Ca2+ transient was much briefer than the first, lasting only several seconds, between the points marked ‘c’ and ‘d’. The decline of the Ca2+ transient at ‘d’ again showed a concurrent net recovery of [Ca2+]SR. This phase of the response to lowering [Mg2+]cyto is addressed in more detail in Fig. 3.

A further subset of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence images is shown (Fig. 3A) that were simultaneously acquired with SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence images (Fig. 3B) in the presence of low Mg2+ solution seen in full in Fig. 2. The time points marked on Fig. 3A and B correspond to those in Figs 2A and 3C. A further spatially restricted profile averaged from the areas marked on the fibre in Fig. 3A at 145 s by the pink and green boxes is shown in Fig. 3C.

Figure 3A and B capture the rise of the secondary Ca2+ release (147–153 s). The region of the fibre that becomes quiescent first, indicated by the white arrow in the image at 145 s, shows a progressive increase in cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence at this region across the next three images. The image at 149 s with a black arrow shows significantly increased rhod-2 fluorescence at this point.

In the region where cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence increased over several seconds (indicated by the white arrows), the net SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence remained relatively constant. At the image marked 149 s the cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence rose sharply and the fluo-5N fluorescence dropped sharply (indicated by black arrow on Fig. 3C). A dark region in the fluo-5N fluorescence image at 149 s in Fig. 3B developed, marked by the arrow. This depletion of [Ca2+]SR increased in Fig. 3C to support a further rise of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence.

In Fig. 3C the spatially averaged fluorescence profiles from the pink boxed area in Fig. 3A show the same events occurring as in the area bound by the green box but with a delay. A difference is a reduced length of time of the slowly rising increase of the cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence (only occurred across images marked 147 and 148 s, in contrast to 145–149 s in the green box). The cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient within the area marked by the pink box then rose rapidly with a corresponding rapid decline in [Ca2+]SR.

There are two issues to address here. First, there are two distinct events of Ca2+ increasing in the cytoplasm but with different rates, which are commonly referred to as leak and release. The spatiotemporally coupled measurements of SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence allow Ca2+ leak and release to be defined. Ca2+ leak can be defined as a rising [Ca2+]cyto (x,y), which induces no net change in [Ca2+]SR (x,y) (there must be an active SR Ca2+ pump to maintain this situation) and Ca2+ release can be defined as a rising [Ca2+]cyto (x,y), which induces a relatively rapid reduction in [Ca2+]SR (x,y). (However, this situation is different in the initial rising phase of the Ca2+ transient in Fig. 2A, where [Ca2+]SR and [Ca2+]cyto both rise. This is addressed below.)

Secondly, that there were different leak times of Ca2+ to the cytoplasm at different locations on the same fibre before Ca2+ release occurred at both locations. It must be noted that the two locations (indicated by the green and pink boxes in Fig. 3A) are connected by an apparent ‘spreading’ Ca2+ release. This suggests that a threshold for release is breached at the first location (green box) and this trigger is somehow transferred to the second location (pink box). This trigger could be expected to be the cytoplasmic increase in Ca2+ itself. This issue is addressed below.

In other experiments it was found that increasing the [EGTA]cyto to 10 mm (a common intervention to reduce the influence of the SR Ca2+ pump on the temporal evolution of Ca2+ release; Manno et al. 2013) and introducing the SR Ca2+ pump blocker, cyclopiazonic acid, in to the low Mg2+ solutions reduced the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient to one phase only with a duration of about a second or so (Fig. 4). In the ‘medium EGTA release’ solution (Table 1) the cytoplasmic Ca2+-dependent fluorescence increased rapidly and peaked after a hundred milliseconds or so and the signal declined monophasically (Fig. 4). This result was repeated on two other fibres. These results indicate that the SR Ca2+ pump has an integral role in maintaining the duration of the Ca2+ transient as observed in Figs 2 and 3 and the observed net recovery of [Ca2+]SR at points b and d in Fig. 2A and Fig. 3.

Figure 4. Inhibition of the SR Ca2+ pump during Ca2+ release depletes the SR in seconds.

The spatially averaged cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence values versus elapsed time (which maps proportionally to the abscissa of xy scans, see Methods) is plotted at top during the exchange of solutions in a skinned fibre from medium EGTA solution for medium EGTA releasing solution (Table 1). The lines above the figure and the vertical, pale grey bar indicate the exchange of solutions. The high amplitude of the rhod-2 fluorescence immediately after the solution exchange indicates the largest amount of Ca2+ is released in the first few hundreds of milliseconds. The xy image during the release of SR Ca2+ is shown at bottom. Note that no Ca2+ halo is observed in 10 mm EGTA (see Methods). Ca2+ is prevented from re-entering SR by 10 mm EGTA and the SR Ca2+ pump blocker CPA. CPA, cyclopianzonic acid; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The reduction in [Mg2+]cyto removes an inhibition from the RyRs, to make them leaky to Ca2+ (Lamb, 1993). Lowering of [Mg2+]cyto from 1 to 0.01 mm has been found to raise the permeability of the SR to Ca2+, PSR, 11-fold in mammalian skeletal muscle (Launikonis & Stephenson, 2000). In the present study it was found that 50 of 60 fibres yielded a Ca2+ release response when [Mg2+]cyto was lowered. The induced leak of Ca2+ from SR upon lowering Mg2+ showed a monotonic decaying relationship with time required to induce Ca2+ release (Fig. 5). This suggests that an underlying stochastic process was at work to convert the imposed cytoplasmic ionic conditions in to the large and prolonged Ca2+ release, as observed in Fig. 2A. The increased PSR induced here is non-physiological, where it is different to that at rest (1 mm Mg2+) and during an action potential (AP), where PSR, 1 mm Mg < PSR, 0.01 mm Mg < PSR, AP, and is expected to create an imbalance between the ability to release Ca2+ (and leak, see above) and buffering Ca2+ inside SR (BSR) (Manno et al. 2013). An abrupt reduction in the Ca2+ buffering power of the SR (Launikonis et al. 2006; Manno et al. 2013), probably via a depolymerization of CSQ inside SR terminal cisternae (Ikemoto et al. 1991; Park et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006; Manno et al. 2013), causes the increase in [Ca2+]SR inducing Ca2+ release.

Figure 5. Frequency plot of leak times.

Plot of ‘leak times’ as defined in Fig. 2.

As Ca2+ can be resequestered by the SR in the experiments shown here (there is an efficiently operating SR Ca2+ pump), and multiple ‘intra-SR Ca2+ transients’ were observed (Fig. 2) the prevalence of multiple abrupt changes in BSR inducing subsequent releases of SR Ca2+ in low Mg2+ is possible. This can be addressed with a simple model of calcium movements inside the major Ca2+ buffering compartments of the fibre. If we assume that the sum of the total calcium contained in the cytoplasm and SR will be constant at all times, including during periods of Ca2+ release. This assumption holds for intact fibres, where not much Ca2+ is lost during repetitive excitation-induced contractions (Armstrong et al. 1972). This assumption can hold for skinned fibres as well, even though the cytoplasmic environment is open to the bathing solution. Skinned fibres consistently resequester all of the released Ca2+ following successive depolarizations without the need to reload the SR with exogenous Ca2+ (Lamb & Stephenson, 1991, 1994; Posterino et al. 2000; Posterino & Lamb, 2003). Therefore, for resting state and during physiological, non-fatiguing Ca2+ release we can say that:

| (1) |

where BSR and Bcyto are the buffering capacity in the SR and cytoplasm, respectively. B is defined further by its relationship with Ca2+ such that we can describe its ‘buffering power’ or ‘capacity’ as:

| (2) |

It follows that for constant values of B, that during Ca2+ release or reuptake that for Ca2+ to increase in one compartment it must decline in the other. If this is the case then during Ca2+ release from SR and at release termination, respectively, the ratios:

| (3) |

| (4) |

must be positive values, as we expect the rate of each parameter to have a positive sign. The ratios from the experiment in Fig. 2A are plotted in Fig. 6. Equation (3) is applied to the rates of Ca2+ change during release, a and c; eqn (4) is applied during the termination of Ca2+ release, b and d, for both prolonged and brief releases. The ratios for b, c and d are positive, indicating a constant BSR and Bcyto during these events. The ratio for a is negative, indicating that a value of B in eqn (1) must have changed during the initial large release of Ca2+ to meet the condition that the sum of total calcium contained in the SR and cytoplasm must remain constant.

Figure 6. Analysis of prolonged Ca2+ release.

Ratios of SR depletion rate to Ca2+ release rate at a and c; and the SR Ca2+ uptake rate to cytoplasmic Ca2+ decline rate at b and d from Fig. 2 (see text). SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

A reduction in the value of BSR during the rise of the prolonged release is favoured with supporting evidence for this from in vitro and vesicle experiments showing that CSQ is a dynamic Ca2+ buffer (Ikemoto et al. 1991; Park et al. 2004); that during long depolarizations in muscle from a MH mouse model that the BSR also changed (Manno et al. 2013); and from the experiments presented below. As the assumption that total calcium remains constant in the fibre even during releases holds for fibres excited by APs (Posterino et al. 2000; Posterino & Lamb, 2003), it follows from eqn (1) that the values of B do not change during normal, non-fatiguing excitation of healthy muscle. This is consistent with the absence of intra-SR Ca2+ transients during AP-induced Ca2+ release in imaging studies (Launikonis et al. 2006; Rudolf et al. 2006; Canato et al. 2010).

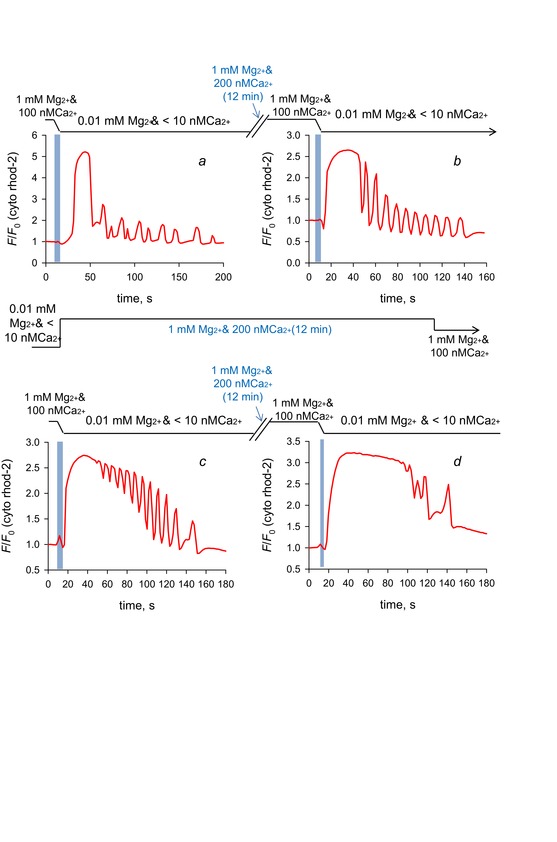

Restitution of BSR

Figure 7 shows the spatially averaged values of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence from a single mouse skinned fibre through four repetitions of loading the SR with Ca2+ in a standard solution with 200 nm Ca2+ and 1 mm Mg2+, a brief pre-equilibration period in standard solution with 100 nm Ca2+ and 1 mm Mg2+ followed by exposure to low Mg2+ solution with no added Ca2+ (see Table 1 for solution compositions). Each iteration of this cycle showed Ca2+ transients in low Mg2+ and in each case, prolonged Ca2+ transients were followed by briefer transients (Fig. 7A–D). The shortening of the transient duration with time in low Mg2+ solution is consistent with reduction in BSR without recovery.

Figure 7. Restitution of BSR by lowering sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) permeability and reloading the SR with Ca2+.

The spatially averaged values of the frames of a xyt series capturing cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence images from a skinned fibre from mouse exposed to four cycles of exposure to 200 nm Ca2+ and 1 mm Mg2+ followed by low Mg2+ and nominally 0 Ca2+. Each response to low Mg2+ produced release of Ca2+ that was initially prolonged, lasting many seconds to tens of seconds, which was followed by much briefer transients. The order of the exposure to low Mg2+ is left-to-right, top-to-bottom, labelled a–d. Images of Ca2+ release from this series of exposures to low Mg2+ are shown in Figs 1, 7 and 9.

Because a reduction in the value of BSR is expected by the initial release of Ca2+ in low Mg2+ (Fig. 6) not all Ca2+ released during the prolonged wave could be recovered from the internal bathing solution of a skinned fibre. Ca2+ diffuses to the bathing solution, as shown by the Ca2+ halos in Figs 3. The result must be lower total calcium available to the SR for continuing releases of Ca2+, consistent with the reduced duration of Ca2+ transients that follow the initial prolonged Ca2+ transient. The result is a net shift in Ca2+ from the SR to the cytoplasm.

The recovery of the long duration Ca2+ transients following bathing in standard solution (1 mm Mg2+ and 100 or 200 nm Ca2+; Fig. 7B–D) indicate an increase in BSR. This only occurred after addition of 1 mm Mg2+ and raised [Ca2+]cyto.

In addition, note that the waveforms of Ca2+ release during each iteration of introducing low Mg2+ solution were very different, consistent with an underlying stochastic mechanism being at work to generate Ca2+ release under these conditions.

Ca2+ release propagates in low Mg2+

Figure 8 shows selected cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence images of a mouse skinned fibre in the presence of low Mg2+. The first row of three images shows a wave that propagates left-to-right with a wave front apparent in the imaged marked 19 s (right-hand side of image). The image marked 20 s shows a Ca2+ halo around the fibre that increases in intensity around the fibre in regions consistent with Ca2+ release occurring for a longer period.

Figure 8. Low Mg2+-induced Ca2+ releases are prolonged Ca2+ waves, brief Ca2+ waves and a composite.

Selected images of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence following the application of low [Mg2+]cyto to a mouse skinned fibre. Three distinct types of Ca2+ wave are shown. A ‘halo’ of Ca2+ in the surrounding bathing solution of the skinned fibre is observed. The spatially averaged values of the complete experiment from which these images have been extracted are displayed in Fig. 7C.

The rows of images marked 64–82 s show a stuttering decline of the prolonged Ca2+ release, which we have termed a composite wave. In each of the three rows of images a section of the fibre at left shows a decline in the cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence, which recovers. This progression is very similar in the images from 64 to 69 s and the images in 71 to 75 s. In the images from 79 to 82 s the declining section of the Ca2+ transient moves further along the fibre, from left-to-right.

During the ‘composite waves’ the intensity of the Ca2+ halo was high. The intensity of the halo declined as the Ca2+ release from the fibre terminated locally. SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence was not imaged in this experiment. However Figs 2 and 3 show that as the Ca2+ transient terminates locally, [Ca2+]SR recovers locally, which is expected here.

The last row of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence images shows a brief wave that propagates from right-to-left. The intensity of the cytoplasmic fluorescence and the proportionally generated Ca2+ halo is lower than the other waves.

The high intensity of the Ca2+ halo around the composite wave (similar to that of the prolonged wave) is used to define it from the brief wave, which has a low intensity Ca2+ halo. The composite waves always lasted more than 1 s, in contrast to brief waves. The non-uniformity of the composite wave (stuttering) separates it from the prolonged wave.

The propagation rate of Ca2+ waves along the long axis of the fibres were 52.8 ± 6.9 (n = 16) and 37.2 ± 10.0 μm s−1 (n = 39) for prolonged and brief waves, respectively (not statistically different, t test, P > 0.1). The FDHM of the prolonged waves was 23.02 ± 3.2 s (n = 38) and all brief waves were less than 1 s. Prolonged waves always occurred when Ca2+ was successfully released following lowering [Mg2+]cyto. However, composite and brief waves did not always occur. The probability of observing composite or brief waves following a prolonged wave was less than 25% (nine of 39 fibres).

Properties of Ca2+ waves

Figures 9 and 10 show activation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in mammalian muscle that were consistent through all fibres examined (mouse and rat, >80 fibres in total). Figure 9 shows images of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence soon after the exchange of a standard solution containing 100 nm Ca2+ for low Mg2+ solution. The transient develops locally, with Ca2+ increasing in a diffuse fashion (that is, with no discrete release events). The transient rises in the right-hand side of the fibre across the images marked 86–93 s. From the images marked 93–98 s the local transient propagates from right-to-left. Note that the skinned fibre preparations were typically a mm or so long, meaning the confocal microscope imaged only a small section of the fibre.

Figure 9. A local and eventless rise of the prolonged Ca2+ transient.

Selected images of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence following the exchange of standard internal bathing solution for low [Mg2+]cyto solution bathing a mouse skinned fibre. A gradual increase of Ca2+ over seconds (images marked 84–91 s) occurs locally without any obvious discrete events. At the imaged marked 93 s the locally increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ began to spread as an apparent Ca2+ wave.

Figure 10 shows an image of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence reproduced from Fig. 8. This figure displays a fibre with a wave front that is relatively uniform across the transverse axis of the fibre. How the wave spreads across the short axis of the fibre is important to understand the mechanisms underlying wave propagation. If it is assumed that the wave originates from a point and the start of the wave shown in Fig. 10 is the central region of the fibre (where the wave front appears first, from the base of the first arrow), then the time elapsed for the wave to propagate from the central area of the fibre to the fibre edge (∼20 μm, length of first arrow) was ∼17 ms (time elapsed between the two arrows). This equates to a propagation rate of ∼1 mm s−1.

From previous work it is known that diffuse Ca2+ release (Fig. 9) is typical of mammalian skeletal muscle where Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) does not play a major role, if any (Shirokova et al. 1998). Furthermore, cytoplasmic propagation of Ca2+ release by CICR does not occur at rates greater than 0.1 mm s−1 (Figueroa et al. 2012), excluding such a mechanism from propagating Ca2+ release across the fibre short axis. Although the apparent rate of ‘transversal Ca2+ release propagation’ is consistent with the rate of AP propagation within the t-system of skeletal muscle (Edwards et al. 2012), APs would also rapidly propagate Ca2+ release at a similar rate along the long axis of the fibre, which was not the case ( Figs 2, 3 and 10). This result and the data presented below are consistent with the propagation of Ca2+ waves in mammalian skeletal muscle being due to a coordinated, lumenal factor and not a cytoplasmic mechanism. Note that the prolonged Ca2+ wave (Fig. 8) also had a slightly concave front, consistent with the absence of CICR propagating the release of Ca2+.

Ca2+ movements inside sarcoplasmic reticulum

The intra-SR Ca2+ transient is suspected to be a result of a change in conformation and subsequent Ca2+ buffering capacity of CSQ (Park et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2010b; Manno et al. 2013). The generation of a local Ca2+ transient inside the SR presents a potential means of fibre excitability that could underlie pathophysiological-type Ca2+ release if the SR is a network that can support the longitudinal mobilization of Ca2+ within it. Note that decreasing BSR locally will favour diffusion of the increased free Ca2+ from such a region inside the SR.

To test this possibility the ionic conditions that favoured the local generation of an intra-SR Ca2+ transient were isolated to a section of skinned fibre while clamping conditions that held the SR more permeant than normal but below the threshold for generating the intra-SR Ca2+ transient elsewhere. These conditions were achieved by isolating two sections of a skinned fibre of mouse with a single line of Vaseline. In this configuration, the two sections of the preparation could be bathed by two separate pools of internal solution. In preliminary experiments (not shown) it was found that by applying the membrane permeant fluo-5N-AM to one pool, the fluorescence from its salt form could subsequently be observed in the SR of the adjacent pool, indicating fluo-5N salt passed longitudinally through the SR under the Vaseline wall.

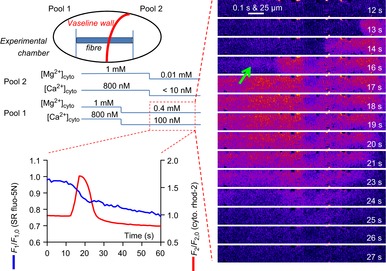

Figure 11 shows a schematic diagram of the experimental conditions where a skinned fibre was separated allowing it to be bathed by two separated pools of solution. This figure also displays images of cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence and the spatially averaged profiles of the simultaneously acquired cytoplasmic rhod-2 and SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence signals.

Figure 11. The skeletal muscle SR is a network that can mobilize Ca2+ along the fibre.

The schematic diagram at top left shows the experimental chamber with a skinned fibre preparation and a Vaseline wall built perpendicular to the axis of the fibre. The Vaseline wall creates two pools that allow different ionic conditions to be imposed across the halves of the preparation. Cytoplasmic rhod-2 fluorescence and SR-trapped fluo-5N fluorescence were imaged in pool 1. The [Mg2+] and [Ca2+] contained in the internal bathing solutions in each pool and the timing of the solution exchanges in an experiment performed in this chamber is shown by the lines below the schematic diagram. The red box indicates the positioning and point in time from which the spatially averaged fluorescence values of rhod-2 and fluo-5N (bottom, left) are derived and the cytoplasmic rhod-2 images (right). At about 10 s after the change in pool 2 from 1 mm to 0.01 mm [Mg2+]cyto a Ca2+ wave propagated along the fibre in pool 1. This was accompanied by a persistent decrease in [Ca2+]SR. The nadir of [Ca2+]SR depletion during the wave was significantly after the peak of the cytoplasmic response. Ca2+ waves were generated in all five preparations challenged in this manner. SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The [Mg2+]cyto and [Ca2+]cyto were changed in either pool bathing the fibre (see blue lines below the schematic diagram in Fig. 11). Initially the entire fibre was loaded with Ca2+ in standard solution with 800 nm Ca2+. In the imaging pool (pool 1), the internal bathing solution was changed to mild inhibitory solution containing 0.4 mm Mg2+ and 100 nm Ca2+ while pool 2 remained with 1 mm Mg2+ and 800 nm Ca2+. There was no noticeable change in cytoplasmic or SR Ca2+-dependent fluorescence. Some 20 s later, the internal solution in pool 2 was changed to low Mg2+ to induce a local Ca2+ release and an intra-SR Ca2+ transient (as in Fig. 2). About 10 s after this change a Ca2+ wave passed along the fibre in pool 1 with a direction consistent with its origin being pool 2.

At time point 16 s in Fig. 11 a diffuse rise of Ca2+ was observed preceding the propagating wave (marked by an arrow). We saw similar behaviour in our experiments where a single pool of internal solution was applied to the whole preparation but in those cases, the low Mg2+ stimulus was everywhere. However, in this example, the Ca2+ release observed in pool 1 must have resulted from the stimulus applied in pool 2. This suggests that Ca2+ has diffused through the SR network ahead of the propagating wave at a level not initially high enough to invoke Ca2+ release. This was not clear from the fluo-5N signal from the SR, presumably due to its dynamic range.

To probe the possibility further that Ca2+ diffusing through the SR was exciting the fibres, a technique that increased the dynamic range and specificity of our compartmentalized signal of Ca2+ movements was employed, which was imaging of Ca2+ inside the sealed t-system of mechanically skinned fibres with fluo-5N (Launikonis et al. 2003). This approach specifically reports the Ca2+ within the ‘microdomain’ of the junctional space between the SR terminal cisternae and the t-system, as the t-system Ca2+ pumps sequester Ca2+ that is locally released to this space by the SR (Edwards et al. 2010b). Furthermore, we introduced 50 mm EGTA to the cytoplasm to reduce significantly the ability of the bulk cytoplasm and SR Ca2+ pumps to act as carriers of Ca2+ along the fibre, where the distance Ca2+ travelled freely from the RyRs was restricted to 54 nm (see Methods). Thus, Ca2+ leaked or released from the RyR can be expected to reach the t-system wall, some 20 nm away but not the junctional membranes at the other A-I bands of the sarcomere or neighbouring sarcomeres through the cytoplasm.

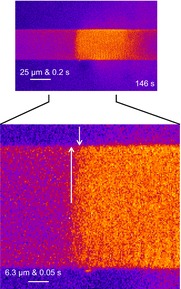

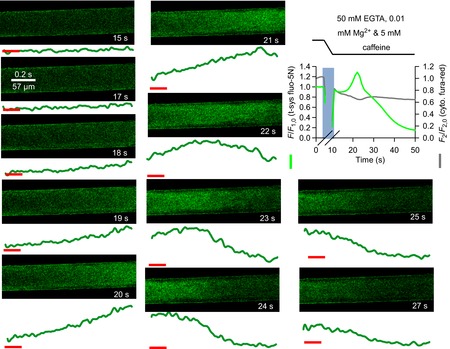

Figure 12 shows fluo-5N fluorescence from the t-system. Spatially averaged values of the fluorescence emitted from within the fibre are presented versus elapsed time (which maps proportionally to y, see Methods and Fig. 1) immediately below each image. A spatially averaged profile of t-system fluo-5N fluorescence values simultaneously acquired with cytoplasmic fura-red fluorescence values are also presented to the top right of the figure.

Figure 12. t-system Ca2+ during prolonged sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in low Mg2+, 5 mm caffeine and 50 mm EGTA.

Spatially averaged values of t-system trapped fluo-5N fluorescence and cytoplasmic fura-red fluorescence during Ca2+ release induced by low Mg2+ and 5 mm caffeine in the presence of 50 mm EGTA following exchange from a solution containing 50 mm EGTA, 1 mm Mg2+ and 100 nm Ca2+ in a rat skinned fibre is shown top right. The lines at the top and pale vertical bar on the spatially averaged profile indicate the solution change. A slow uptake of Ca2+ by the t-system followed by a slow depletion is reported by t-system fluo-5N. The fura-red signal shows a peak trailed that of the t-system signal. Note that fura-red fluorescence is inversely proportional to [Ca2+]. Selected images of t-system trapped fluo-5N fluorescence are shown with time-stamps corresponding to that in the spatially averaged profile. Below each image are the spatially averaged values of t-system trapped fluo-5N fluorescence versus elapsed time (which maps proportionally to the abscissa of xy scans, see Methods). The horizontal red lines mark the arbitrary baseline for all images. Ca2+ increases in the t-system at right as the image is presented and moves to the left, followed by a depletion of Ca2+.

In this experiment, a high EGTA solution was exchanged for a high EGTA release solution, at the time indicated by the vertical pale blue bar. Following this solution exchange, the t-system took up Ca2+ (at 15 to 20 s) after a lag of several seconds. This indicated a local release of SR Ca2+ had occurred. This was followed by a decline of the t-system fluorescence signal. This can be attributed to chronically activated store-operated Ca2+ entry consistent with local [Ca2+]SR depletion (Launikonis et al. 2003).

The simultaneously acquired cytoplasmic fura-red fluorescence signal shows an increase in bulk [Ca2+]cyto that trails that of the peak uptake of Ca2+ by the t-system. This result can be attributed to the heavy Ca2+ buffering of the bulk cytoplasm by 50 mm EGTA.

The spatially and temporally resolved images of t-system fluo-5N fluorescence in the presence of high EGTA release solution show an increase in [Ca2+]t-sys from the right-hand side of the fibre as it is presented, across the next three to four images until a peak is reached in the sixth image. This peak moves through the t-system over the next three images. A similar profile was seen in two other preparations (10 other preparations showed a uniform and rapid release of Ca2+).

The [Ca2+]t-sys transient observed in Fig. 12 is consistent with a diffusion of Ca2+ longitudinally within the SR. This conclusion is reached because alternative possibilities can be excluded: the narrow longitudinal tubules of the t-system (Edwards & Launikonis, 2008) and the 50 mm EGTA present in the cytoplasm exclude the propagation of Ca2+ through the t-system and cytoplasm.

Discussion

Here we have shown that by lowering [Mg2+]cyto to mimic a situation where RyR affinity for Mg2+ is altered and thus lowering inhibition of RyR opening, produces Ca2+ release that propagates along the fibre. The removal of RyR inhibition or increase in Ca2+ leak is the trigger for a reduction in BSR. This induces a rise of an intra-SR Ca2+ transient to promote the diffusion of Ca2+ through the SR network, lumenally activated opening of RyRs and a release of Ca2+ that appears as a propagating wave ( Figs 2). No evidence could be found for a role of CICR in the propagation of Ca2+ release upon lowering [Mg2+]cyto ( Figs 2). The reduction in BSR in the presence of a constant amount of calcium causes a net shift in calcium from the SR to the cytoplasm. The result in muscle would be a persistent rise in [Ca2+]cyto and activation of all calcium ATPases causing muscle rigidity, and heat and acid generation. This situation is maintained until the normally high value of BSR can be restored (Fig. 7). These properties of voltage-independent Ca2+ release upon the removal of inhibition of RyRs has implications for understanding pathophysiological Ca2+ release as observed clinically (MacLennan et al. 1990; Lamb, 1993; Steele & Duke, 2007).

Ca2+ waves driven from inside the sarcoplasmic reticulum

We observed two basic types of Ca2+ waves in mammalian skeletal muscle, prolonged and brief. Both types of waves were generated only after a reduction in RyR inhibition and BSR. Neither could be attributed to propagation via cytoplasmic mechanisms but there are some critical differences that allow us to deduce the mechanism underlying this type of propagating release.

Prolonged waves

Our results ( Figs 2) suggest that local intra-SR Ca2+ transients cause a diffusion of Ca2+ through the SR network and a subsequent release of locally rising lumenal Ca2+ to the cytoplasm. The transversally uniform front of the observed Ca2+ waves ( Figs 1) and diffuse rise of the cytoplasmic transient are at odds with the involvement of a cytoplasmic mechanism of Ca2+ wave initiation or propagation (Shirokova et al. 1998). Instances of CICR would promote Ca2+ sparks or the propagation of Ca2+ waves across the short axis of the fibre at a rate not much more than ∼0.1 mm s−1 (Figueroa et al. 2012). Neither of these scenarios was observed in this study. Furthermore, by separating the halves of a skinned fibre and clamping the ionic conditions it was possible to cause propagation of Ca2+ release in to the other half of the fibre held under resting ionic conditions (0.4 mm Mg2+ and 100 nm Ca2+; Fig. 11). Others have shown that under similar ionic conditions that photolysis of caged Ca2+ in the cytoplasm could never elicit such a response in mouse fibres (Figueroa et al. 2012). Collectively these results are very strong evidence that Ca2+ waves in mammalian skeletal muscle ( Figs 2) are not using CICR or any other cytoplasmic mechanism to promote their propagation.

The exclusion of cytoplasmic means of propagation limits the mechanism of voltage independent Ca2+ release observed here to a lumenal one. A lumenal Ca2+ sensing property of the RyR in mammalian skeletal muscle was identified some time ago (Palade et al. 1983; Volpe et al. 1983). This suggests the mode of Ca2+ release observed in this study is store overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR). We note that some level of inhibition of the RyR may have been relieved also by the change in CSQ form (Beard et al 2002, 2005, 2009; Wei et al 2006; Sztretye et al. 2011).

The lumenal sensing gate on the RyR for SOICR has recently been identified. This site is common to all RyR isoforms (Chen et al. 2014) and so can be expected to open the RyR1 of mammalian skeletal muscle upon [Ca2+]SR (x,y) rising high enough. The threshold for SOICR is reduced under conditions of reduced RyR inhibition (Chen et al. 2014), which is probably only slightly above endogenous [Ca2+]SR of ∼0.5 mm in low [Mg2+]cyto (Lamb & Stephenson, 1991, 1994; Jacquemond & Schneider, 1992; Lamb, 1993; Launikonis & Stephenson, 2000). However, such lumenal sensing of locally rising [Ca2+]SR does not yet explain the ‘spreading’ of Ca2+ release.

The locally rising intra-SR Ca2+ transient ( Figs 2, 3 and 9) provides the increase in [Ca2+]SR (x,y) required to trigger SOICR. Lowering [Mg2+]cyto allows the increased leak of Ca2+ from the SR ( Figs 2 and 3) to create an imbalance between the rate of Ca2+ leak and uptake. Under these conditions this triggers the reduction in BSR through the presumed depolymerization of CSQ (Ikemoto et al. 1991; Park et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006; Royer & Rios, 2009; Manno et al. 2013). The reduction in BSR causes [Ca2+]SR to rise, which results in its local release to the cytoplasm via SOICR; and to its diffusion through the SR, to induce SOICR resolved as a cytoplasmic Ca2+ wave.

The role of the SR Ca2+ pump is important to Ca2+ release duration (see Fig. 2), as it maintained [Ca2+]SR above the inactivation threshold for RyRs. In low [Mg2+]cyto this value of [Ca2+]SR is expected to be close to 0.1 mm (Laver et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006). This [Ca2+]SR will be reached quickly if the SR Ca2+ pump is denied Ca2+ and/or BSR is low. Release inactivation allows the SR to re-accumulate Ca2+ with the RyRs closed, again priming the SR for SOICR (as observed in Figs 2 and 3) but only to evolve as much briefer waves.

Brief waves

The situation during the occurrence of brief Ca2+ waves is different from that of the prolonged waves. Even before the brief waves start, BSR is at its lowest level, consistent with their duration ( Figs 3, 6 and 9). The genesis of the prolonged Ca2+ wave is the intra-SR transient evoked by the reduction in BSR, followed by the diffusion of Ca2+ within the SR from this source with the support of SR Ca2+ pumps keeping [Ca2+]SR high. An abrupt reduction in BSR does not seem to be involved in the initiation of brief waves.

A feature of Ca2+ waves in mammalian skeletal muscle allows us to understand how the threshold for SOICR is reached to generate these waves. As we have shown here ( Figs 3, 5 and 9) the propagating front is always relatively parallel to or slightly concave across the short axis of the fibre. This feature excludes the participation of cytoplasmic mechanisms in the propagation of Ca2+ release (compared with cardiac muscle that shows an oblique angle to the transverse axis of the fibre in time, e.g. Keller et al. 2007), as argued above. As no waves propagated from a point we can conclude that the lumenal coordinating factor driving the Ca2+ wave must be applied uniformly across the short axis of the fibre for the wave to start and to move forward. Therefore for SOICR to initiate the brief wave a uniform rise in [Ca2+]SR across the fibre short axis is required.

It seems probable that point increases in [Ca2+]SR would occur. One can simply expect therefore that local rises in [Ca2+]SR simply diffuse away across the short axis of the fibre within the SR to prevent SOICR.

Thus the coordinating factor of Ca2+ waves in mammalian skeletal muscle is [Ca2+]SR. The generation of the spatially required [Ca2+]SR threshold probably underlies the stocasticity of Ca2+ wave generation in mammalian skeletal muscle. This will be an interplay between (i) the rate that the SR Ca2+ pumps are loading Ca2+ into the SR, a process dependent on the local [Ca2+]cyto, and (ii) the Ca2+ gradients inside SR determining the diffusion of Ca2+ and the rise of [Ca2+]SR (x,y). If [Ca2+]SR is high in all directions preventing diffusion of Ca2+ away from the site of increase is coupled with more Ca2+ being pumped into the region due to relatively high [Ca2+]cyto (x,y) the chance of the intra-SR Ca2+ transient breaching the threshold for SOICR is increased.

Ca2+ waves inside sarcoplasmic reticulum and pathophysiological Ca2+ release

While we have shown a change in BSR causes an intra-SR transient following a voltage independent mean of activation, there are also examples that voltage activation of skeletal muscle under conditions where the normal resting inhibition of the RyR is altered causing intra-SR Ca2+ transients. Jacquemond and Schneider (1992) lowered the [Mg2+]cyto in a voltage-clamped frog fibre to see ‘amazing, ultra-slow bumps’ of Ca2+ release following brief voltage pulses (fig. 7 in Jacquemond & Schneider, 1992). The activation of voltage-controlled Ca2+ release under conditions where the RyR was not inhibited by the normal cytoplasmic divalent concentration must have caused a reduction in BSR, as observed here ( Figs 2). The use of photometry hides the possibility that Ca2+ waves occurred in this experiment but this was probably the case. Therefore, the ‘ultra-slow bumps’ following voltage activation form as do the brief waves described above.

The identification of Ca2+ waves inside the SR allow us to propose a mechanism for the type of Ca2+ release observed during a MH crisis. From ours and others in vitro work (Lamb, 1993; Steele & Duke, 2007; Manno et al. 2013), it appears that in the presence of an MH trigger (e.g. halothane) the array of RyRs that are exposed increase their rate of SR Ca2+ leak, PSR. This leak may be balanced by uptake of Ca2+ via the SR Ca2+ pump for a period. When the pump cannot balance the leak, CSQ experiences a reduction in its Ca2+ buffering capacity (BSR), probably via depolymerization of its complex structure (Perni et al. 2013) causing a loss of Ca2+-binding sites and an increase in [Ca2+]SR follows (Park et al. 2004; Launikonis et al. 2006). This is the intra-SR Ca2+ transient ( Figs 2).

It is the intra-SR transient that will generate longitudinal Ca2+ waves in SR as the local [Ca2+]SR rises. This will create ‘propagating’ SOICR where, by diffusion and supported by the action of SR Ca2+ pumps, Ca2+ moves along the fibre within the SR ( Figs 2). The highly permeant RyRs in the presence of the MH trigger (which lowers the threshold for SOICR) will support Ca2+ release at the site of the intra-SR Ca2+ transient generation ( Figs 2 and 3) and as the SR Ca2+ wave passes ( Figs 2). This type of Ca2+ release induces further CSQ depolymerization and reduction in BSR (Fig. 11). So despite the constant action of SR Ca2+ pumps, released Ca2+ cannot be cleared by the SR because of its reduced BSR; therefore, both [Ca2+]SR and [Ca2+]cyto remain persistently high until the situation is arrested. The major effect of the reduction in BSR is that the previously bound Ca2+ within the SR becomes the source for the increased free Ca2+ in the cytoplasm (due to the reduction of BSR) causing the prolonged activation of all cytoplasmic Ca2+ ATPases. This underlies the hypermetabolic state of an MH episode. Restitution of BSR (Fig. 7) is required to restore the resting condition, which we showed here as a readmission of mm Mg2+ to inhibit RyR Ca2+ leak but in the operating theatre will require Dantrolene or equivalent (Hopkins, 2011; Maclennan & Zvaritch, 2011).

We predict that many μ-intra-SR Ca2+ transients (intra-SR transient within a sarcomere) occur but do not necessarily trigger MH. When many μ-intra-SR Ca2+ transients occur in relative synchrony within an array of adjacent sarcomeres then the locally increased [Ca2+]SR will diffuse within the volume of the local SR network, inducing back-inhibition on the SR Ca2+ pump (de Meis & Sorenson, 1989) increasing net leak. This will initiate more μ-intra-SR Ca2+ transients and increase the probability of initiating a ‘macro’ intra-SR transient.

An alternative initiating event to that caused by halothane would be that via chronic depolarization induced by succinylcholine that is often administered in the operating theatre (Hopkins, 2011). Succinylcholine will cause a large release of Ca2+ from SR and a reduction in BSR, similar to that shown by Jacquemond & Schneider (1992). In this situation Ca2+ re-entry to the SR via the Ca2+ pumps will generate a large rise in [Ca2+]SR to activate SOICR in the now poorly Ca2+-buffered environment of the SR, to generate waves in the same manner observed here ( Figs 3 and 2).

Here we have shown that the generation of an intra-SR Ca2+ transient is an event activating Ca2+ release and propagation, occurring in the absence of voltage activation in mammalian skeletal muscle. A local rise of SR Ca2+ can trigger prolonged Ca2+ waves via SOICR with its propagation supported by movement of Ca2+ inside SR. Under conditions of reduced BSR, rises in [Ca2+]SR can trigger Ca2+ waves. Intra-SR transients are not observed during non-fatiguing, physiological Ca2+ release (Launikonis et al. 2006; Rudolf et al. 2006; Canato et al. 2010) and require alterations in the way the Ca2+ release unit handles divalent cations to be generated (Lamb, 1993; Laver et al. 1997; Duke et al. 2002, 2004, 2006, 2010; Launikonis et al. 2006; Manno et al. 2013). Waves can also be generated following voltage-dependent Ca2+ release where a reduction in BSR is induced (Jacquemond & Schneider, 1992; Manno et al. 2013), an event that succinylcholine could produce in the operating theatre. Ca2+ waves within the SR represent a novel way in which skeletal muscle fibres can be excited and probably underlie pathophysiological events such as MH and environmental or exertional heat stroke. Furthermore the commonality of the lumenal sensing gate of all RyRs to SOICR (Chen et al. 2014) suggests that any manipulation that would render cardiac RyR2, for example, non-responsive to CICR would promote cardiac cells to generate the unique ‘uniform-fronted’ Ca2+ waves observed in mammalian skeletal muscle.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Andrew Bjorksten and Robyn Gillies (Royal Melbourne Hospital) and Neil Street and Sandra Cooper (Westmead Hospital, Sydney) for helpful discussions on malignant hyperthermia. We also thank Christel van Erp for expert technical assistance.

Glossary

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- CSQ

calsequestrin

- FDHM

full duration at half-magnitude

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- t-system

tubular system

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- SOICR

store overload-induced Ca2+ release

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

T.R.C., J.N.E. and B.S.L. designed the study, performed and analysed experiments; B.S.L. wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council and the National Health & Medical Research Council (Australia) to B.S.L.

References

- Armstrong CM, Bezanilla FM, Horowicz P. Twitches in the presence of ethylene glycol bis(-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetracetic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;267:605–608. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandschapp O, Girard T. Malignant hyperthermia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13652. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard NA, Sakowska MM, Dulhunty AF, Laver DR. Calsequestrin is an inhibitor of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Biophys J. 2002;82:310–320. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard NA, Wei L, Dulhunty AF. Control of muscle ryanodine receptor calcium release channels by proteins in the sarcoplasmic reticulum lumen. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36:340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard NA, Casarotto MG, Wei L, Varsányi M, Laver DR, Dulhunty AF. Regulation of ryanodine receptors by calsequestrin: effect of high luminal Ca2+ and phosphorylation. Biophys J. 2005;88:3444–3454. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Shannon TR. Calcium movements inside the sarcoplasmic reticulum of cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canato M, Scorzeto M, Giacomello M, Protasi F, Reggiani C, Stienen GJ. Massive alterations of sarcoplasmic reticulum free calcium in skeletal muscle fibers lacking calsequestrin revealed by a genetically encoded probe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22326–22331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Wang R, Chen B, Zhong X, Kong H, Bai Y, Zhou Q, Xie C, Zhang J, Guo A, Tian X, Jones PP, O'Mara ML, Liu Y, Mi T, Zhang L, Bolstad J, Semeniuk L, Cheng H, Zhang J, Chen J, Tieleman DP, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Fill M, Song LS, Chen SR. The ryanodine receptor store-sensing gate controls Ca2+ waves and Ca2+-triggered arrhythmias. Nat Med. 2014;20:184–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meis L, Sorenson MM. ATP regulation of calcium transport in back-inhibited sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;984:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Steele DS. Effects of Mg2+ and SR luminal Ca2+ on caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle from humans susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. J Physiol. 2002;544:85–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Steele DS. Mg2+ dependence of halothane-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003;551:447–454. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Halsal JP, Steele DS. Mg2+ dependence of halothane-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle from humans susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1339–1346. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200412000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Halsall PJ, Steele DS. Mg2+ dependence of Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum induced by sevoflurane or halothane in skeletal muscle from humans susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:320–328. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Calaghan SC, Halsall JP, Steele DS. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible human skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25645–25653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Launikonis BS. The accessibility and interconnectivity of the tubular system network in toad skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2008;586:5077–5089. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Friedrich O, Cully TR, von Wegner F, Murphy RM, Launikonis BS. Upregulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry in dystrophic mdx mouse muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010a;299:C42–C50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00524.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Murphy RM, Cully TR, von Wegner F, Friedrich O, Launikonis BS. Ultra-rapid activation and deactivation of store-operated Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle. Cell Calcium. 2010b;47:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Blackmore DG, Gilbert DF, Murphy RM, Launikonis BS. Store-operated calcium entry remains fully functional in aged mouse skeletal muscle despite a decline in STIM1 protein expression. Aging Cell. 2011;10:675–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Cully TR, Shannon TR, Stephenson DG, Launikonis BS. Longitudinal and transversal propagation of excitation along the tubular system of rat fast-twitch muscle fibres studied by high speed confocal microscopy. J Physiol. 2012;590:475–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.221796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa L, Shkryl VM, Zhou J, Manno C, Momotake A, Brum G, Blatter LA, Ellis-Davies GC, Rios E. Synthetic localized calcium transients directly probe signalling mechanisms in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2012;590:1389–1411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii J, Otsu K, Zorzato F, de Leon S, Khanna VK, Weiler JE, O'Brien PJ, MacLennan DH. Identification of a mutation in porcine ryanodine receptor associated with malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1991;253:448–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1862346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins PM. Malignant hyperthermia: pharmacology of triggering. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:48–56. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto N, Antoniu B, Kang JJ, Meszaros LG, Ronjat M. Intravesicular calcium transient during calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5230–5237. doi: 10.1021/bi00235a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemond V, Schneider MF. Low myoplasmic Mg2+ potentiates calcium release during depolarization of frog skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:137–154. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe ID, Launikonis BS. Three-dimensional reconstruction and analysis of the tubular system of vertebrate skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4048–4058. doi: 10.1242/jcs.131565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbara AA, Allen DG. The use of the indicator fluo-5N to measure sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium in single muscle fibres of the cane toad. J Physiol. 2001;534:87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Pignier C, Egger M, Niggli E. Calcium waves driven by “sensitization” wave-fronts. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD. Ca2+ inactivation, Mg2+ inhibition and malignant hyperthermia. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1993;14:554–556. doi: 10.1007/BF00141551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD, Stephenson DG. Effect of Mg2+ on the control of Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle fibres of the toad. J Physiol. 1991;434:507–528. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD, Stephenson DG. Effects of intracellular pH and [Mg2+] on excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 1994;478(Pt 2):331–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launikonis BS, Rios E. Store-operated Ca2+ entry during intracellular Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2007;583:81–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launikonis BS, Stephenson DG. Effects of Mg2+ on Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum of skeletal muscle fibres from yabby (crustacean) and rat. J Physiol. 2000;526(Pt 2):299–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]