Abstract

Based on a review of community care demonstrations, we conclude that expanding public financing of community services beyond what already exists is likely to increase costs. Small nursing home cost reductions are more than offset by the increased costs of providing services to those who would remain at home even without the expanded services. However, expanded community services appear to make people better off and not to cause substantial reductions in family caregiving. Policymakers should move beyond asking whether expanding community care will reduce costs to addressing how much community care society is willing to pay for, who should receive it, and how it can be delivered efficiently.

Evolution of community care research

The existing long-term care system, it has been argued, favors nursing home over community care for the frail elderly for two reasons. First, difficulty finding out about and managing the services needed to live at home leads to unnecessary decisions to enter nursing homes. Second, public programs pay for nursing home care for chronic conditions but not for long-term care in the community (Morris, 1971; Congressional Budget Office, 1977; Mechanic, 1979; Kane and Kane, 1980). These arguments led to a series of demonstrations of expanded government financing for case management and formal community services. In this article, we assess the findings of these demonstrations in terms of effects on nursing home and hospital use, informal caregiving, costs, and the quality of clients' lives.

Research on community care began, not with long-term care, but with acute care. The hypothesis underlying this approach was that, if nursing care were provided at home, patients could leave the hospital sooner. The cost savings from reducing the length of hospital stays would more than offset the costs of visiting nurses. Two methodologies were used to test this hypothesis. In one, the hypothetical cost of nursing care at home was compared with the cost of hospital care (for example, Scutchfield and Freeborn, 1971; Bryant, Candland, and Lowenstein, 1974). In the other, hospital patients were randomly assigned to two groups, one with home health care available after the hospitalization and the other without (for example, Bakst and Marra, 1955; Katz et al., 1968; Stone, Patterson, and Felson, 1968; Gerson and Collins, 1976). Regardless of methodology, the authors generally concluded that the total costs of acute care could be reduced by expanding home health benefits (Hammond, 1979; Hedrick and Inui, 1986).

The focus of attention gradually shifted to whether home care, including nonmedical services such as personal care and homemaker services, can substitute for nursing home care. Here the hypothesis was that long-term care for chronic conditions would cost less if the disabled person received care at home rather than moving permanently to a nursing home. Again, two methodologies were used. Bell (1973), Greenberg (1974), Rathbone-McCuan and Lohn (1975), Brickner and Scharer (1977), U.S. General Accounting Office (1977), Piland (1978), Sager (1979), Anderson, Patten, and Greenberg (1980), and Arkansas Office on Aging (1981) compared the cost of home care for a sample of impaired clients in the community with the cost that would have been incurred if they had been admitted to a nursing home. These hypothetical cost comparisons demonstrated that many impaired older people, including some who reside in nursing homes, could be cared for in the community at lower cost. Findings from other research indicated that from 10 to 40 percent of those in nursing homes were inappropriately placed there (Morris, 1971; Williams et al., 1973; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1979). Together these findings supported the argument that public financing of community care should be expanded to reduce unnecessary nursing home use.

Other researchers used randomized experiments to test the effect of limited expansions of community services: caseworkers (Goldberg, 1970); protective service caseworkers and home health aides (Blenkner, Bloom, and Nielsen, 1971); monitoring visits by nurses (Katz et al., 1972); and personal care, housekeeping, and escort services (Nielsen et al., 1972). All employed random assignment to treatment and control groups, but the samples were relatively small (100 to 300). Katz et al. (1972) and Nielsen et al. (1972) found statistically significant reductions in nursing home use. Blenkner, Bloom, and Nielsen (1971) reported an unexpected increase in nursing home placement, although it was not statistically significant. These early field trial, also found some evidence of effects on other outcomes. Nielsen et al. (1972) reported increased contentment; Goldberg (1970) reported increased social activities; and Blenkner, Bloom, and Nielsen (1971) reported decreased stress among informal caregivers.

Because the use of home health care under Medicare and Medicaid had not grown to present levels at the time of these field trials, their findings may not be useful in assessing current policies. These studies did, however, lay the foundation for demonstrations of case management and expanded community services during the 1970's and 1980's.

In this article, we review the demonstrations from this period that provided case-managed community care to impaired elderly populations and were funded through special waivers of certain Medicaid or Medicare regulations. The 16 such demonstrations are listed together with their variants when more than one model was tested:

Worcester Home Care.

National Center for Health Services Research (NCHSR) Day Care/Homemaker Experiment: Day Care Model, Homemaker Model, and Combined Day Care and Homemaker Model.

Triage.

Washington Community Based Care (CBC).

ACCESS.

Georgia Alternative Health Services (AHS).

Wisconsin Community Care Organization (CCO).

On Lok Community Care Organization for Dependent Adults.

Organizations Providing for Elderly Needs (OPEN).

Multipurpose Senior Services Project (MSSP).

South Carolina Community Long-Term Care (CLTC).

Nursing Home Without Walls.

New York City Home Care.

Florida Pentastar.

San Diego Long-Term Care (LTC).

Channeling: Basic Model and Financial Model.

In limiting our study to demonstrations that provided case-managed community care to the elderly population, we have not reviewed all long-term care demonstrations funded through waivers. Demonstrations we have not reviewed include the effort to deinstitutionalize patients in Level II intermediate care facilities in Texas; the Flexible Intergovernmental Grant demonstration, designed to foster cooperation among local agencies that provide community services to elderly people in Oregon; the Medicare and Medicaid hospice demonstration of alternative care for the terminally ill; the Aid to Families with Dependent Children home health aide demonstration, which trained AFDC recipients to provide home care; and the social health maintenance organization demonstration, which integrates acute and long-term care under capitation financing. (Hamm, Kickham, and Cutler, 1982, describe these waiver-funded demonstrations.) In addition, numerous State governments have undertaken community care initiatives under waivers or State financing, but they typically have not been rigorously evaluated (Greenberg, Schmitz, and Lakin, 1983; Health Care Financing Administration, 1984). Finally, several demonstrations reviewed here—Triage, ACCESS, and On Lok—evolved into different interventions. We have reviewed only their initial phases.

In limiting our study to demonstrations funded through waivers of Medicare and Medicaid regulations, we have not reviewed community care demonstrations undertaken during this period with other funding. Information on these demonstrations can be found, for example, in Papsidero et al. (1979); Hughes (1981); and Groth-Juncker et al. (1983). Findings from these projects are generally consistent with those reported here. Finally, studies of interventions other than case-managed community care—for example, sheltered housing (Sherwood et al., 1981) and personal care homes (Sherwood and Morris, 1983; Ruchlin and Morris, 1983)—have not been included in this review.

Our review builds on previous reviews by Applied Management Sciences (1976); LaVor and Callender (1976); Doherty, Segal, and Hicks (1978); Greenberg et al. (1980); Steiner and Needleman (1981); Stassen and Holahan (1980); Toff (1981); U.S. General Accounting Office (1982); Zawadski et al. (1984); Palmer (1982a and 1982b); Hughes (1985); Kotler et al. (1985); Capitman, Haskins, and Bernstein (1986); Capitman (1986); Hedrick and Inui (1986). We base our review on the final evaluation reports of the 16 demonstrations and a cross-cutting evaluation of several of the demonstrations performed by Berkeley Planning Associates (Haskins et al., 1985). The source documents are preceded by asterisks in the reference list at the end of the article. Interested readers are referred to Kemper, Applebaum, and Harrigan (1987) for the detailed review that is summarized here.

Interventions tested

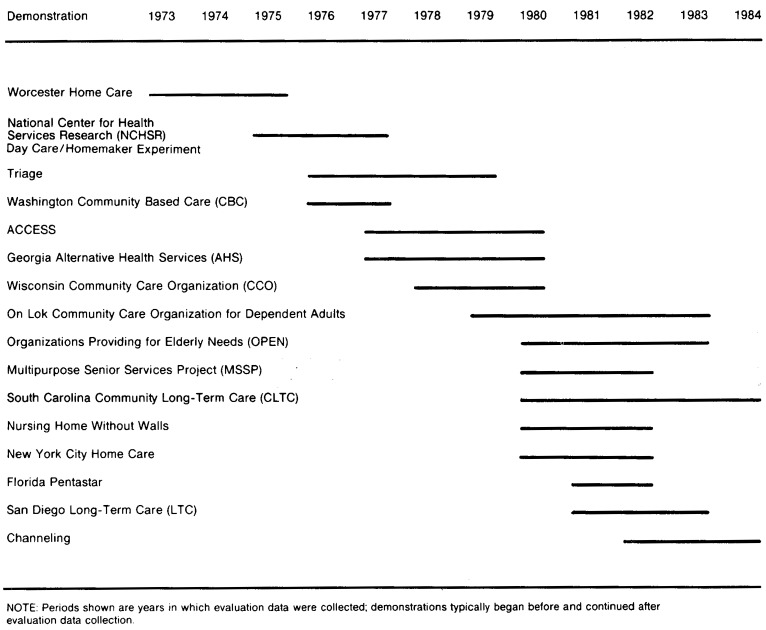

The community care demonstrations funded through waivers began in the early 1970's with the Worcester Home Care demonstration and continued to the completion of the South Carolina CLTC and Channeling demonstrations in 1984 (Figure 1). Despite varied designs, all the demonstrations shared the common objective of substituting community care for nursing home care whenever appropriate. Meeting this objective was expected to reduce long-term care costs and improve the quality of clients' lives. Case management and an expanded package of community services were the key program elements of these demonstrations.

Figure 1. Timing of evaluation data collection, by time period.

Case management consists of assessment of needs, design of a care plan, arrangement of services, and ongoing monitoring of clients. Most demonstrations used individual case managers, but four used teams made up of professionals from different disciplines. Only the NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker experiment did not provide ongoing case management. Because it did not provide a broad range of services (one model provided adult day care; the second, homemaker services; and the third, adult day care and homemaker services), coordination of services through ongoing case management was not essential to the intervention.

The intensity of the case management varied across the demonstrations that provided it. Triage had the highest average caseload, 125 cases per case manager. Caseloads of other demonstrations ranged from 45 to 80 clients.

Expanded community services were funded through waivers of Medicare or Medicaid regulation's to permit payment for services not normally covered (e.g., homemaker services), in situations not normally covered (e.g., personal care without a need for skilled nursing care), or to individuals not normally eligible (e.g., those who would be eligible for Medicaid if in a nursing home but not in the community). These waivers made it possible to pay for a broader range of community care services over a longer period to different types of people than is typically possible under Medicaid and Medicare. (The only exception to funding through waivers was for the Basic Model of the Channeling demonstration, which had only limited funds to pay for services to fill in the gaps in the existing system. These services were funded directly through demonstration contracts rather than through waivers. The Financial Model of Channeling paid for the full range of community services through waivers of Medicaid and Medicare regulations.)

In all the demonstrations, in-home service coverage was expanded to include nonmedical services. All except the NCHSR Day Care Model covered homemaker services or personal care, the services most needed by chronic care patients at home. Other services often covered included chore, companion, transportation, and home-delivered meals. Most demonstrations could pay for nurses and home health aides in circumstances not normally covered by Medicare and Medicaid. Some also covered one or more other services: adult day care, foster care, escort services, housing improvements, respite care, medical equipment, mental health counseling, prescription drugs, etc. The demonstrations generally did not cover acute medical care. The one important exception was On Lok, which covered physician, hospital, and nursing home care.

The extent to which case managers can authorize payment for the full package of community services determines whether they can control service delivery or must act as brokers and advocates for their clients, coordinating care paid for by other agencies. Typically, the demonstrations had power to authorize only expanded services, the intent being to rely on existing programs before using demonstration funds. However, the authority of several demonstrations was extended to include services covered by other programs, such as Medicaid or Medicare.

There was some concern that costs might increase with expanded government financing for community services. In an effort to control costs, seven demonstrations implemented limits on the amount that could be spent on community services for each individual. These cost caps ranged from 60 to 85 percent of nursing home reimbursement rates.

A second cost control element, client cost sharing, was implemented by three demonstrations. Clients with incomes above a specified dollar amount were required to contribute to the cost of services purchased by the demonstration. Because clients' incomes were typically low, the extent of cost sharing turned out to be quite small.

Populations served

Ten demonstrations were directed toward the elderly, with mininum ages ranging from 50 to 65 years; one had no minimum age; and the other five served the entire adult disabled population. All of the demonstrations required that clients be eligible for an existing program, usually the program (Medicare or Medicaid) under whose waivers services were funded.

The demonstrations sought to serve those at risk of nursing home placement and developed specific need or disability criteria to identify the high-risk population. (The only exception was the first phase of the Triage demonstration; in its second phase, disability requirements were added.) Eight demonstrations required that clients have a service need but did not have formalized disability criteria. Five imposed specific disability requirements. Finally, ACCESS and South Carolina CLTC identified clients as part of a nursing home preadmission screening process; only clients who met Medicaid requirements for nursing home admission were eligible.

The targeting approach determined the frailty of the population served. In Table 1, four measures of frailty are presented: disability in activities of daily living (ADL's), such as eating, bathing, or dressing; impairment in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL's), such as cooking and shopping; incontinence; and cognitive impairment, which was determined by responses to 10 questions about the respondents' age, the day of the week, the name of the U.S. President, etc. Demonstrations are grouped by their approach to targeting. Clients' frailty increases with the stringency of the disability requirements. At one extreme, Triage had neither need nor disability criteria, and 54 percent of the clients served turned out to have at least one disability in ADL's. At the other extreme, South Carolina CLTC relied on preadmission screening, and 95 percent of the clients served turned out to have at least one ADL disability.

Table 1. Client disability at enrollment, by enrollment criteria.

| Enrollment criteria and demonstration | Percent disabled in at least 1 ADL | Percent impaired in at least 1 IADL | Percent incontinent | Cognitive impairment1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No need or disability criteria | ||||

| Triage | 54 | 94 | — | 1.7 |

| Service need criteria2 | ||||

| Worcester Home Care | 41 | — | — | — |

| NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker | 77 | — | — | — |

| OPEN | 50 | 81 | 24 | 0.6 |

| MSSP | 61 | 80 | 47 | 1.7 |

| New York City Home Care | 78 | 100 | 38 | 2.6 |

| Florida Pentastar | 58 | 97 | 22 | 1.4 |

| San Diego LTC | 55 | 97 | 43 | 2.3 |

| Disability criteria | ||||

| Georgia AHS | 60 | — | — | 3.1 |

| Wisconsin CCO | 62 | 97 | — | — |

| On Lok | 85 | 93 | 60 | 3.2 |

| Nursing Home Without Walls | 76 | — | — | — |

| Channeling | 84 | 100 | 55 | 3.5 |

| Preadmission screen | ||||

| ACCESS | 82 | 99 | 44 | 2.4 |

| South Carolina CLTC | 95 | 97 | 58 | 3.5 |

Cognitive impairment is determined by the number of incorrect answers to 10 questions about basic facts.

Washington CBC falls in this category but is not included in the table because comparable disability measures were unavailable.

NOTES: The full names of all demonstrations are shown in Figure 1. ADL is activity of daily living. IADL is instrumental activity of daily living.

Evaluation designs

In Table 2, some important features of the evaluation designs are presented. Sample sizes, which determine the ability to detect effects, varied considerably, ranging from 139 to 6,326. The number of replications of the intervention and the diversity of service environments in which it is tested affect the generalizability of the findings. Most demonstrations were conducted in only one State, although some were tested in more than one site within the State. One demonstration was conducted in 4 States, and another in 10.

Table 2. Evaluation methodology and size of demonstration.

| Demonstration | Comparison methodology | Number of States | Number of sites | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worcester Home Care | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 485 |

| NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker | Random assignment | 4 | 6 | 1,566 |

| Triage | Comparison group outside area | 1 | 1 | 502 |

| Washington CBC | County-level comparison | 1 | 2 | — |

| ACCESS | County-level comparison | 1 | 1 | — |

| Georgia AHS | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 1,332 |

| Wisconsin CCO | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 417 |

| On Lok | Comparison group outside area | 1 | 1 | 139 |

| OPEN | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 335 |

| MSSP | Comparison group within and outside area | 1 | 8 | 4,200 |

| South Carolina CLTC | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 1,867 |

| Nursing Home Without Walls | Comparison group within and outside area | 1 | 9 | 1,373 |

| New York City Home Care | Comparison group outside area | 1 | 1 | 704 |

| Florida Pentastar | Random assignment plus comparison group outside area | 1 | 5 | 1,046 |

| San Diego LTC | Random assignment | 1 | 1 | 831 |

| Channeling | Random assignment | 10 | 10 | 6,326 |

NOTE: The full names of all demonstrations are shown in Figure 1.

The most important design feature is the comparison methodology. To measure the effect of expanded community care, the experiences of the persons to whom the expanded services were made available must be compared with some measure of what the experiences of the same persons would have been without the expanded services.

Nine evaluations used a randomized experimental design. Eligible applicants were randomly assigned either to receive demonstration services (treatment status) or to receive only those services regularly available in the community (control status). Random assignment is a powerful design because it ensures that, for a large sample, the treatment group will be similar to the control group on both measured and unmeasured characteristics. Thus, the nine randomized experiments are most likely to obtain unbiased estimates of demonstration effects.

The other evaluations were quasi-experiments in which comparison groups similar to the treatment group were selected, but not by using random assignment. A quasi-experimental design is generally a weaker design because the comparison group may differ from the treatment group on measured and unmeasured characteristics. As it turned out, even the measured characteristics of the treatment and comparison groups differed for all the quasi-experiments, in some cases substantially. (Several of the quasi-experiments sought to mitigate the risk of bias by controlling for pretreatment differences using multivariate statistical analysis, but such statistical control is limited in its ability to deal with pretreatment noncomparabilities on unmeasured characteristics.)

Selecting a group that is similar to the treatment group is particularly difficult for community care demonstrations because the central outcome of interest, nursing home use, is extremely difficult to predict. Research has shown that measured characteristics explain little of the variation in nursing home placement rates (Grannemann, Grossman, and Dunstan, 1986). Moreover when, as was often the case, comparison groups are chosen from outside the demonstration site, many factors other than the demonstrations affect outcomes. (Because ACCESS and Washington CBC were county-wide interventions, outside comparison groups were necessary. Aggregate Medicaid cost and nursing home use in the demonstration counties were compared with the corresponding estimates for the set of comparison counties.)

Recent research on the bias of quasi-experimental methodologies is not reassuring. LaLonde (1986) and Fraker and Maynard (to be published) found that the actual results of a randomized employment and training experiment differed substantially from quasi-experimental evaluation of the same demonstration. LaLonde (1986) concludes that “policymakers should be aware that the available nonexperimental evaluations… may contain large and unknown biases …. ”

Because of the inherent weakness of the quasi-experimental methodology, we base our assessment on the randomized experiments. For interested readers, the results of the quasi-experiments are included in the tables and footnotes.

In interpreting the evaluation results, the reader should be aware that expanded case-managed community care is compared with the long-term care system at the time of the demonstration, which covered some community care under Medicare, Medicaid, and other government programs. The demonstrations tested the expansion of community care beyond what already existed, not community care versus its total absence. Moreover, some of the demonstrations were undoubtedly tested in environments where nursing home bed supply was constrained by restrictions on reimbursement rates and construction of new beds. It is difficult to determine how the effect of community care might differ in other service environments.

Nursing home use

All the demonstrations sought to substitute community care for nursing home care, and all the evaluations analyzed nursing home use as an outcome. The comprehensiveness with which nursing home use was measured, however, depended on the data available. Medicaid and private individuals are the major payers for nursing home care. Therefore, evaluations that relied on Medicare records alone measured only a fraction of nursing home use. Medicaid and Medicare records do not cover use paid for by private individuals (although this is, of course, unimportant if clients are required to be eligible for Medicaid). The omission of privately financed nursing home care is potentially important because many people enter nursing homes as private-pay patients, only later spending down their assets to the point of Medicaid eligibility. Indeed, about one-half of nursing home residents covered by Medicaid enter as private-pay patients. In presenting the results in Table 3, therefore, we report the data sources and distinguish between studies that measure essentially all use and those with only partial measures.

Table 3. Nursing home days during the first year for treatment and control group, by type of experiment.

| Type of experiment and demonstration | Data source | Number of days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Treatment mean | Control mean | Difference | Percent difference | |||

| Randomized experiments, all use | ||||||

| Worcester Home Care | Interviews1 | 46 | 46 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Georgia AHS | Medicaid records1 | 22 | 29 | −7 | −24.1 | |

| Medicare records | ||||||

| South Carolina CLTC | Medicaid records1 | 90 | 130 | *−40 | −30.8 | |

| Medicare records | ||||||

| Florida Pentastar | Interviews1 | — | — | — | −10.6 | |

| Channeling: |

|

Medicaid records | ||||

| Basic Model | Medicare records | 25 | 29 | −4 | −13.8 | |

| Financial Model | Provider records | 23 | 26 | −3 | −11.5 | |

| Randomized experiment, Medicaid use only | ||||||

| Wisconsin CCO | Medicaid records1 | 25 | 33 | −8 | −24.2 | |

| Randomized experiments, Medicare use only | ||||||

| NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker: | ||||||

| Day care | Medicare records | 5 | 7 | −2 | −28.6 | |

| Homemaker | Medicare records | 3 | 4 | −1 | −25.0 | |

| Combined | Medicare records | 4 | 5 | −1 | −20.0 | |

| OPEN | Medicare records | 0.1 | 0.3 | −0.2 | −66.7 | |

| San Diego LTC | Medicare records | 0.5 | 0.9 | −0.4 | −44.4 | |

| Quasi-experiments, all use | ||||||

| Triage | Interviews Diaries |

7 | 4 | 3 | 75.0 | |

| On Lok | Interviews Diaries |

20 | 117 | *−97 | −82.9 | |

| MSSP | Medicaid records1 | 39 | 45 | −6 | −13.3 | |

| Medicare records | ||||||

| Quasi-experiment, Medicaid and Medicare use only | ||||||

| Nursing Home Without Walls: | ||||||

| Upstate New York |

|

Medicaid records | 6 | 99 | *−93 | −93.9 |

| New York City | Medicare records | 5 | 40 | *−35 | −87.5 | |

| Quasi-experiment, Medicare use only | ||||||

| New York City Home Care | Medicare records | 0.2 | 1.1 | −0.9 | −81.8 | |

Denotes statistical significance.

All clients were required to be eligible for Medicaid.

NOTE: The full names of all demonstrations are shown in Figure 1.

Of the six studies that used randomized designs and had essentially complete data on nursing home use, five yielded consistent results. For Worcester Home Care, Georgia AHS, Wisconsin CCO, and Channeling, treatment group nursing home use was equal to or less than control group use. However, the differences were small, ranging from 0 to 8 days during the year after enrollment, and not statistically significant. Nursing home days were not measured in the Florida Pentastar evaluation. However, nursing home use as measured by the percent who had entered a nursing home by 18 months after enrollment was slightly lower for the treatment group than for the control group: 7.6 versus 8.5 percent, a difference that was not statistically significant. There is no evidence that any of these demonstrations reduced nursing home use after the first year.

In all of these cases, the populations served turned out to be at relatively low risk of nursing home placement, precluding large reductions in nursing home use. The control groups, which represent the risk of nursing home use in the absence of expanded services, spent only 26-46 days in nursing homes during the first year after enrollment. Even if these demonstrations had cut nursing home use in half, the number of nursing home days saved would have been modest. Moreover, actual reductions were well below 50 percent, ranging from 0 to 24 percent.

The South Carolina CLTC findings stand in contrast to the findings of these five experiments: high control group use (130 days during the first year after enrollment) and a large, statistically significant reduction (40 days) for the treatment group compared with the control group. Three-year followup data indicate that the reduction persists.

The distinguishing feature of South Carolina CLTC appears to have been its integration with a nursing home preadmission screen. Clients were among the most disabled of any of the demonstrations (Table 1) and were at greatest risk of nursing home use. By identifying clients “at the nursing home door” and requiring nursing home eligibility under Medicaid, South Carolina CLTC appears to have identified the intended target population and reduced its nursing home use. In addition to its success in identifying a high-risk population, South Carolina CLTC's relative reduction of nursing home use was higher as well (31 percent).

The three randomized experiments that measured only nursing home use under Medicare also found that treatment group use was below control group use. As indicated earlier, however, Medicare claims cover only a small fraction of all nursing home use. Moreover, none of the differences was statistically significant, and the magnitudes of the measured differences were small.1

In attempting to identify groups for which expanded community care can substitute for nursing home care, several of the evaluations analyzed differences in effects across subgroups. The evidence is limited by the small subgroup samples, small number of evaluations analyzing subgroups, and lack of consistency of subgroup definitions and methodology. The limited evidence suggests that larger nursing home use reductions may be associated with being more disabled (up to some level), having less informal support, being in a nursing home (certified for discharge), and having a higher statistically predicted probability of nursing home placement (up to some level). In many cases, however, subgroups associated with high nursing home use were not associated with larger reductions in use, and many of the subgroups for which significant reductions were observed were small.

Hospital use

Except for San Diego LTC and OPEN, reduction in hospital use was not a main objective of the demonstrations. Nonetheless, community care might be a substitute for hospital care by permitting patients awaiting nursing home placement to be discharged to their homes instead. On the other hand, expanding community care might increase hospital use. For example, increased monitoring of patients might increase admissions, or patients at home may require more hospitalizations because nursing homes may be able to treat some conditions otherwise requiring hospitalization.

Among the randomized experiments, control group use during the first year after enrollment varied from 4 to 25 days. Treatment group use was typically 1 day lower than control group use, but it ranged up to 3 days lower for OPEN and 9 days lower for Wisconsin CCO. Only the Wisconsin CCO difference was statistically significant, however, and it was based only on use under Medicaid, which is not the primary payer for hospital care.2

Hospital use thus appears to be unaffected or at most slightly reduced by case-managed community care. On the other hand, concern that hospital use might be increased by expanded case management and community services does not appear to be justified.

Costs

Analysis of effects on costs is limited by the data collected. Comprehensive cost data are difficult to collect because they are dispersed across numerous providers and funding sources. Among the randomized experiments, Worcester Home Care and Florida Pentastar did not collect sufficient cost information for meaningful cost analysis. NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker collected only Medicare costs; Wisconsin CCO, only Medicaid costs; and Georgia AHS, South Carolina CLTC, and San Diego LTC, Medicare and Medicaid but not other public or private costs. Given the partial nature of most studies' data, the cost estimates must be interpreted cautiously.

OPEN reported a reduction in costs of $65 per person per month, and Wisconsin CCO essentially broke even. The cost estimates for both demonstrations are subject to question.3 In both demonstrations, lower costs resulted from reductions in hospital use, not nursing home use. Since the time of the demonstrations, the service environment has changed. The advent of Medicare prospective payment using diagnosis-related groups has increased pressure to reduce hospital lengths of stay. Although this change may have increased the need for home care, expanding public financing for such care is less likely to reduce hospital use now than at the time of these demonstrations.

South Carolina CLTC appears to have broken even by substituting community care for nursing home care. Compared with the control group, total Medicaid and Medicare costs rose an average of $53 per person per month during the first year after enrollment, an increase of 7.7 percent. For the subsample followed for 3 years, total Medicaid and Medicare costs for the treatment group averaged $15 per month, or 2.2 percent, higher than costs for the control group.4 Total costs probably increased somewhat more, however, if private costs are included. Because more clients remained in the community, they incurred more room and board costs themselves.

Without substantial reductions in nursing home use, all the other randomized experiments increased costs: Basic Model Channeling ($82 per person per month), Georgia AHS ($123), Financial Model Channeling ($286), NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker ($279-$396, depending on the model), and San Diego LTC ($346).5

Informal caregiving

Publicly financed community services have the potential to be a partial substitute for informal care that is provided by family and friends without cost to the government. Two views of substitution differ in their implications for public costs. One view is that paid formal services will partially replace informal care, perhaps with benefits to informal caregivers and clients but at increased public cost. The other view is that formal services will supplement informal care, leading to some substitution in the short run but enabling caregivers to continue giving care longer, thereby reducing total public costs in the long run (Spivak, 1984; Christianson, 1986).

Only six evaluations estimated effects on informal caregiving, and their measures were generally limited. The South Carolina CLTC project substantially increased the proportion of the sample receiving informal care at home. This increase was directly associated with the decrease in nursing home placement. Because more of the treatment group remained at home, where they relied on informal care, a higher proportion of the treatment group than the control group received informal care. (Informal care in nursing homes was not measured.)

In the absence of reductions in nursing home use, formal care appears, to a small extent, to be a substitute for informal help with IADL tasks. Of the demonstrations that used randomized experimental designs but did not significantly reduce nursing home use, Worcester Home Care, OPEN, and Basic Model Channeling had no significant effect on informal caregiving. Compared with the control group, San Diego LTC and Financial Model Channeling did not affect informal help with ADL tasks but decreased informal help with IADL tasks. The reduction for Financial Model Channeling was small in magnitude. It was concentrated among the caregivers least closely associated with clients (visiting caregivers, friends or neighbors, and relatives other than spouses or children); the amount of care by primary caregivers, who provide the bulk of care, was unaffected. The San Diego LTC study did not report magnitudes.6

The question of whether the small amount of substitution of formal for informal IADL care in the short run enables informal caregivers to continue giving care in the long run remains unresolved. The small reductions in informal help with IADL's by the San Diego LTC and Financial Model Channeling demonstrations did not lead to substantial reductions in nursing home use during the 18-month followup period.

Quality of life, functioning, and longevity

All of the demonstrations shared the objective of improving the quality of clients' lives. Providing clients the opportunity to choose to live in their own homes rather than nursing homes was one mechanism expected to improve quality of life. Providing needed services to those who would live at home even without expanded community services was another. Attempts to measure life quality varied considerably across the evaluations, making overall assessment of effects and comparisons across projects difficult.

Unmet needs and satisfaction with service arrangements

In two randomized experiments, questions were asked about the care received. Georgia AHS staff asked whether sample members were getting enough help. Channeling staff asked about satisfaction with arrangements for house cleaning, meals, laundry, and shopping. Both demonstrations found small but statistically significant benefits compared with the control group. Channeling also reported significant increases in clients' confidence about getting help and significant reductions in reported unmet needs for care. Financial Model Channeling also significantly increased primary informal caregivers' satisfaction with care arrangements.7

Social interaction

Although it is not their central focus, case managers might be expected to encourage more social activity. Six randomized experiments analyzed one or more measures of social interaction. NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker Combined Model, Basic Model Channeling, and OPEN found significant increases compared with the control groups.8

Health and functioning

Health status and functional ability were expected to be improved, or their deterioration slowed, through regular monitoring to identify problems and through increased access to services such as physical therapy. In addition, deterioration in functioning was expected to be slowed by reducing nursing home placements. Nursing homes are believed to increase functional dependence because staff do not permit patients to perform some activities, such as bathing, without help.

Three randomized experiments analyzed self-rated health. Compared with the control group, San Diego LTC found a significant increase in self-rated health at 6 months, and Basic Model Channeling found significant increases at 12 months. Financial Model Channeling, however, found more worry about health reported by clients at 6 months. Worcester Home Care found no effect.

The eight randomized experiments that tested effects on disability in ADL's were split about evenly on the outcome. Two reported statistically significant results. Compared with the control group, South Carolina CLTC found a significant reduction in reported disability at 6 months. Financial Model Channeling found that the treatment group reported significantly more disability than the control group at 6 and 12 months.

Two conflicting interpretations could explain these results. The first is that receipt of services leads to overreporting of disability. Because most questions about ADL's refer to receipt of help rather than ability to perform an activity (e.g., “Does someone help you take a bath?”), answers may identify those who receive help as more disabled even if they are not. The second interpretation is that those who receive services become more dependent, or in fact more disabled, as a result of getting help: When individuals do less for themselves, either psychological dependence may develop or skills may atrophy. The South Carolina CLTC and Financial Model Channeling results, although in opposite directions, are both consistent with either interpretation. South Carolina CLTC clients probably got less help with ADL's than they would have received without the intervention, whereas Financial Model Channeling clients got more help than controls.9

Because questions on IADL's typically measure capacity rather than performance, these measurement problems do not apply. Five randomized experiments analyzed IADL impairment. Only in the Florida Pentastar demonstration did the treatment group report more IADL impairment than the control group, a result that may have been biased by noncomparable data for the two groups. Georgia AHS, South Carolina CLTC, Channeling, and OPEN found no effect.10

Life satisfaction and morale

Global measures of psychological well-being ranged from single-item questions concerning overall life satisfaction (e.g., “In general, how satisfying do you find the way you are spending your life these days?”) to multiple-item morale scales (e.g., the Philadelphia Geriatric Center's morale scale, which has a dozen items, including whether life is worth living, whether there is a lot to be sad about, etc.). All six randomized experiments that analyzed global life satisfaction reported that treatment group life satisfaction was higher than that of the control group in at least one period, but the differences were generally small and usually not statistically significant.11

Expansion of community care might also be expected to improve the well-being of informal caregivers. Channeling confirmed this expectation. Both Channeling models significantly increased the percent of primary informal caregivers reporting satisfaction with life.

Longevity

Case-managed community care may indirectly affect clients' longevity. Two countervailing effects are possible. On the one hand, the possibility that medical conditions that would be treated in a nursing home might go untreated in the community could increase the risk of dying. Because there was little evidence of substitution of community for nursing home care, this hypothesis is unlikely to hold. On the other hand, case manager monitoring of the medical conditions of those in the community may reduce the risk of death.

Treatment and control group mortality rates 1 year after enrollment are shown in Table 4. Death rates were high, ranging from 7 percent to 35 percent among the randomized control groups. The variation is generally associated with the level of disability of the clients served.

Table 4. Mortality rates after 1 year for treatment and control group, by type of experiment.

| Type of experiment and demonstration | Treatment mean | Control mean | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Percent | |||

| Randomized experiment | |||

| Worcester Home Care | 13 | 16 | −3 |

| NCHSR Day Care/Homemaker: | |||

| Day Care | 17 | 18 | −1 |

| Homemaker | 30 | 35 | −5 |

| Combined | 21 | 24 | −3 |

| Georgia AHS | 13 | 21 | *−8 |

| Wisconsin CCO | 6 | 8 | −2 |

| OPEN | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| South Carolina CLTC | 30 | 32 | −2 |

| Florida Pentastar | 8 | 11 | −3 |

| San Diego LTC | 21 | 23 | −2 |

| Channeling: | |||

| Basic Model | 28 | 30 | −2 |

| Financial Model | 27 | 27 | 0 |

| Quasi-experiment | |||

| Triage | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| On Lok | 15 | 23 | −8 |

| Nursing Home Without Walls: | |||

| Upstate New York | 12 | 22 | *−10 |

| New York City | 17 | 24 | −7 |

| New York City Home Care | 17 | 15 | 2 |

Denotes statistical significance.

NOTE: The full names of all demonstrations are shown in Figure 1.

Of the randomized experiments, treatment group death rates were 2 percentage points higher than control group rates in one case; equal in a second; but lower in all the rest, with differences ranging from 1 to 8 percentage points. Only the reduction of 8 percentage points for Georgia AHS was statistically significant, however.12

Conclusions

Early research demonstrated that community care can be a cost-saving substitute for nursing home care for some individuals. To the extent that financial incentives under Medicaid, lack of information about community services, or inability to manage those services result in nursing home placement of those individuals, caring for them at home will reduce costs. Because people generally prefer to live in their own homes rather than in nursing homes, moreover, their life quality is likely to improve. The case-managed community care demonstrations were based on this logic.

Summary of findings

The demonstrations have shown that expanding publicly financed community care does not reduce aggregate costs, and it is likely to increase them—at least under the current long-term care service system, which already provides some community care. Small reductions in nursing home costs for some people are more than offset by the increased costs of providing expanded community services to others who would remain at home even without expanded services.

An exception to this conclusion was the South Carolina CLTC demonstration, which essentially broke even with respect to public costs. Several conditions had to be met for it to do so. South Carolina CLTC identified a high-risk population by requiring Medicaid nursing home eligibility certified through a nursing home preadmission screen. It effected a relatively high rate of nursing home reduction, 31 percent versus 0-24 for the other randomized experiments with complete data. It kept community care costs low: Its case-management cost was only $49 per client per month, compared with a range of $85-$145 for the other demonstrations for which data are available, and it increased community service costs less than most of the demonstrations did.

A single demonstration in a single State cannot show us whether these conditions can be replicated and maintained in an ongoing program. Findings can only suggest that it may be possible under some conditions to expand public financing of community care without increasing aggregate public costs. The bulk of the demonstration experience suggests, however, that costs are likely to increase with increased public financing of community care. This is because it is difficult to serve only those at high risk of nursing home placement, difficult to effect large relative reductions in placement rates, and costly to provide the level of community care that many feel is appropriate.

Although it is likely to increase aggregate costs, expanding public financing for community services does appear to make people better off. The measures of well-being are imperfect in many respects, but compared with the control groups, a pattern of higher life quality for the treatment groups was apparent. The magnitude of the increase and its value to society are difficult to assess. However, some improvement in life quality without reduction in longevity does appear to result from the expanded services. It is wrong, therefore, to conclude that expanding public financing for community care is not cost effective. Costs are likely to go up, but so are benefits.

Moreover, the limited available evidence suggests that the demonstrations did not cause wholesale substitution of publicly financed formal services for care provided informally by family and friends. Although some substitution appears to occur in the area of help with IADL's, the extent of substitution is small, certainly less than some had feared.

Cost reductions through improved targeting

Our interpretation of the cost results, that expanded community care benefits are likely to increase aggregate costs, will not be universally accepted. Some will assert that improved targeting—developing mechanisms for identifying and serving only those who would otherwise be placed in nursing homes at higher cost—could result in interventions that reduce costs. For several reasons, we believe that changes in the approach to targeting are not likely to reduce aggregate costs. (This subject is also discussed in Weissert, 1985.)

First, the targeting issue is not new. The demonstrations have sought, to varying extents, to serve precisely the population at risk of nursing home placement. Failure to identify this population is not for lack of trying. Indeed, theoretical work by Greene (1986) shows that when the at-risk group is rare, a high proportion of people passing even a relatively accurate screen will not turn out to be at risk. Therefore, the nursing home placement rates that were observed in the demonstrations may be consistent with more accurate screening than is generally understood.

Second, demonstrations may overstate success in targeting. In a permanent program, participation rates of those not at risk of nursing home placement may increase over time. More potential clients may learn about the expanded benefits and how to gain access to them, and case managers' commitment to enforcing eligibility criteria may weaken after the special demonstration. (Neither was the case for the South Carolina CLTC demonstration, however, suggesting that it may be possible to maintain consistent targeting through quality control.)

Third, differences in effects across subgroups were limited. Subgroup differences do not translate directly into changes in eligibility criteria that will reduce costs. Although reductions in nursing home use seem to be greater for some subgroups, the evidence is far from definitive, the cutoff levels between subgroups cannot be well defined, and many of the subgroups appear to be quite small. Nursing home placement is simply very difficult to predict.

Finally, as the need for care and the associated risk of nursing home placement increase, the cost advantage of community care over nursing home care diminishes. Therefore, the cost saving from serving those at high risk may not be great.

This does not imply that the population served is an unimportant issue. On the contrary, who gets served is a central issue. However, because expanded community care has usually been justified based on cost savings, relatively little thought has been given to who should receive publicly financed community care. In light of the demonstration results, we believe that determining eligibility criteria is not primarily an issue of targeting efficiency: For whom will cost reduction through substitution of community care for nursing home care be greatest? Rather, it is primarily an issue of equity: Who deserves the limited community care that society can pay for? For example, should clients pass a means test to be eligible and, if so, should family income be counted? What level of physical or mental disability defines need? Does the availability of family and friends to help with care affect eligibility? These questions pose extraordinarily difficult societal choices, but they are policy decisions that must be made.

The community care demonstrations, in short, should alter the nature of the debate about expanding case-managed community care. Given current evidence, expansion of community care must be justified based not on its cost savings but on its benefits to the disabled elderly and the family and friends who care for them. The debate should move the next step forward. It should move beyond asking whether expanded public financing of community care will reduce costs to addressing how much community care society is willing to pay for, who should receive it, and how a more efficient long-term care system can be designed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Don Blackman, John Capitman, Donald Goldstone, Vernon Greene, Mary Harahan, Rosalie Kane, Leslie Saber, William Saunders, and Robyn Stone for their helpful comments on the longer version of this article.

This research was begun under the small grants program sponsored by the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It builds on work done as part of the evaluation of the National Long-Term Care Channeling Demonstration under Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. The views expressed are those of the authors and not those of any organization.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Publications and Information Branch, National Center for Health Services Research, 18-12 Parklawn Building, 5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, Maryland 20857.

The quasi-experimental findings varied widely. Triage and New York City Home Care reported small, nonsignificant differences; MSSP reported a 6-day decrease (statistical significance not reported); and On Lok and Nursing Home Without Walls reported large, statistically significant reductions (Table 3). The two evaluations that used county-level comparisons both reported reductions in nursing home use relative to the comparison counties. Washington CBC reported annual declines in Medicaid nursing home populations of -3.0 and -4.5 percent in the two demonstration sites, compared with -0.6 in the balance of the State (Solem et al., 1979). ACCESS reported that Medicaid nursing home expenditures rose 5.7 percent in the demonstration site, compared with 23.1 percent in the six comparison counties (Price and Ripp, 1980).

Results for the quasi-experiments are not statistically significant and are without pattern.

Wisconsin CCO measured only Medicaid costs, thus omitting any effects on Medicare, other public, or private costs. Two estimates are available for OPEN. An estimate by the project staff (Sklar and Weiss, 1983) shows reduced costs. Another estimate, made as part of a cross-cutting evaluation of several community care demonstrations (Haskins et al., 1985), shows increased costs. The evidence suggests to us that Medicare costs including community services paid for under waivers were increased; combined private and other public costs were reduced; and overall, total costs were reduced. However, there is clearly more uncertainty about the OPEN estimates than the cost estimates generally.

This estimate is based on multiple regression, which controls for treatment-control differences in baseline characteristics. The unadjusted treatment-control differences indicate that costs were reduced by $21 (3.1 percent) over the 3-year period.

Evidence from the quasi-experiments is inconsistent. Large increases were found in four and large decreases in two.

New York City Home Care, a quasi-experiment, found a reduction in informal help with ADL tasks.

New York City Home Care, a quasi-experiment, significantly reduced unmet needs in two areas, medical and economic-social-environmental, but not in ADL and IADL care.

The results of the one quasi-experiment that examined social interaction, New York City Home Care, are consistent with these results.

Results of the quasi-experiments are consistent with those of the randomized experiments. Nursing Home Without Walls, which reported a very large reduction in nursing home use, found significant reductions in ADL disability compared with the control group. New York City Home Care, which reported a substantial increase in community service costs but no significant effect on nursing home use, reported a significant increase in disability.

Results for the quasi-experiments are inconsistent. New York City Home Care reported more IADL impairment, but On Lok reported less impairment, when compared with the control groups.

On Lok, the only quasi-experiment to analyze a related measure (psychological requirements of living), reported a significant increase in well-being compared with the control group.

The results of the quasi-experiments are generally consistent with those of the randomized experiments: two small, nonsignificant increases and three large decreases, one of which was significant.

Asterisk indicates source document.

References

- Anderson NN, Patten SK, Greenberg JN. A Comparison of Home Care and Nursing Home Care for Older Persons in Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota; 1980. Grant No. 90-A-682. Prepared for Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- *.Applebaum RA, Harrigan M. Channeling Effects on the Quality of Clients' Lives. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; Apr. 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Applied Management Sciences. Evaluation of Personal Care Organizations and Other In-Home Alternatives to Nursing Home Care for the Elderly and Long-Term Disabled, Final Report and Executive Summary (Revised) Silver Spring, Md.: May, 1976. Contract No. HEW-OS-74-294. Prepared for Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Arkansas Office on Aging. The In-Home Option: An Evaluation of Non-Institutional Services for Older Arkansans. Little Rock, Ark.: Arkansas Department of Human Services; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bakst HJ, Marra EF. Experience with home care for cardiac patients. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 1955 Apr.45(4):444–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.45.4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. Community care for the elderly: An alternative to institutionalization. Gerontologist. 1973;13(3, Part 1):350–55. doi: 10.1093/geront/13.3_part_1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Birnbaum H, Gaumer G, Pratter F, Burke R. Nursing Home Without Walls: Evaluation of the New York State Long-Term Home Health Program. Cambridge, Mass.: Abt Associates; Dec. 1984. Contract No. 500-79-0052. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Blenkner M, Bloom M, Nielsen M. A research demonstration project of protective services. Social Casework. 1971 Oct.52(8):483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Brickner P, Scharer LK. Hospital provides home care for elderly at one-half nursing home cost. Forum. 1977 Nov-Dec;1(2):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown RS, Mossel PA. Examination of the Equivalence of Treatment and Control Groups and the Comparability of Baseline Data. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; Oct. 1984. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown TE, Jr, Blackman D, Learner RM, Witherspoon MB. South Carolina Community Long-Term Care Project: Report of Findings. Spartanburg, S.C.: South Carolina State Health and Human Services Finance Commission; Jul, 1985. Grant No. 11-P-97493/4. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant NH, Candland L, Lowenstein R. Comparison of care and cost outcomes for stroke patients with and without home care. Stroke. 1974 Jan-Feb;5:54–59. doi: 10.1161/01.str.5.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitman JA. Community-based long-term care models, target groups, and impacts on service use. Gerontologist. 1986 Aug.26(4):389–397. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitman JA, Haskins B, Bernstein J. Case management approaches in coordinated community-oriented long-term care demonstrations. Gerontologist. 1986 Aug.26(4):398–404. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Carcagno G, Applebaum R, Christianson J, et al. The Evaluation of the National Long-Term Care Demonstration: The Planning and Operational Experience of the Channeling Projects. 1 and 2. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- *.Christianson JB. Channeling Effects on Informal Care. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Long-Term Care for the Elderly and Disabled. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office; Feb. 1977. Budget Issue Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty N, Segal I, Hicks B. Alternatives to institutionalization for the aged. Aged Care and Services Review. 1978;1:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker T, Maynard R. The adequacy of comparison group designs for evaluations of employment-related programs. J Hum Resour. To be published. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson LW, Collins JF. A randomized controlled trial of home care: Clinical outcomes for five surgical procedures. Can J Surg. 1976 Nov.19(6):519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M. Helping the Aged, A Field Experiment in Social Work. London: George Allen and Unwin Limited; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- *.Grannemann TW, Grossman JB, Dunstan SM. Differential Impacts Among Subgroups of Channeling Enrollees. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J. A Planning Study of Services to Noninstitutionalized Older Persons in Minnesota, Part Two, The Costs of In-Home Services. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota; 1974. Report prepared under contract to the Governor's Citizens Council on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JN, Doth D, Johnson A, Austin C. A Comparative Study of Long-Term Care Demonstration Projects: Lessons for Future Inquiry. Minneapolis, Minn.: Center for Health Services Research, University of Minnesota; Mar. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JN, Schmitz MP, Lakin KC. An Analysis of Responses to the Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Long-Term Care Waiver Program (Section 2176 of Public Law 97-35) Washington, D.C.: State Medicaid Information Center, National Governors' Association; Jun, 1983. Grant Nos. 18-P-97923/3-3/03 and 18-P-98078-5-01. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Greene VL. Nursing Home Admission Risk and the Cost-Effectiveness of Community-Based Long-Term Care. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; Chicago. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Groth-Juncker A, Zimmer JG, McCusker J, Williams TF. Home Health Care Team: Randomized Trial of a New Team Approach to Home Care. 1983 Grant No. HS-03030. Prepared for National Center for Health Services Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm LV, Kickham TM, Cutler DA. Research, demonstrations, and evaluations. In: Vogel RJ, Palmer HC, editors. Long-Term Care: Perspectives from Research and Demonstrations. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1982. Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J. Home health care cost effectiveness: An overview of the literature. Public Health Rep. 1979 Jul-Aug;94(4):305–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Haskins B, Capitman J, Collignon F, et al. Evaluation of Coordinated Community Oriented Long-Term Care Demonstrations. Berkeley, Calif.: Berkeley Planning Associates; 1985. Contract No. 500-80-0073. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. Studies Evaluating Medicaid Home and Community-Based Care Waivers. Office of Research and Demonstrations; Baltimore, Md.: Dec. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick SC, Inui TS. The effectiveness and cost of home care: An information synthesis. Health Serv Res. 1986 Feb.20(6, Part II):851–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SL. Evaluation of a Comprehensive Long-Term Care Program for Chronically Impaired Elderly. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms International; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SL. Apples and oranges? A review of evaluations of community-based long-term care. Health Serv Res. 1985 Oct.20(4):461–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Kane RA. Alternatives to institutional care of the elderly: Beyond the dichotomy. Gerontologist. 1980 Jun;20(3):249–259. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.3_part_1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Amasa B, Downs TD, et al. Effects of Continued Care: A Study of Chronic Illness in the Home. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1972. DHEW Pub No. HSM 73-3010. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Vignos PJ, Moskowitz RW, Thompson HM. Comprehensive outpatient care in rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1968;206(6):1219–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P, Applebaum R, Harrigan M. A Systematic Comparison of Community Care Demonstrations. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Institute for Research on Poverty; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- *.Kemper P, Brown RS, Carcagno GJ, et al. The Evaluation of the National Long Term Care Demonstration: Final Report. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler M, Wright G, Jaskulski T, Kreisberg I. Synthesis of Cost Studies on the Long-Term Care of Health-Impaired Elderly and Other Disabled Persons: Final Report. Silver Spring, Md.: Macro Systems, Inc.; Jun, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- LaLonde RJ. Evaluating the econometric evaluations of training programs with experimental data. American Economic Review. 1986 Sept.76(4):604–620. [Google Scholar]

- LaVor J, Callender M. Home health cost effectiveness: What are we measuring? Med Care. 1976 Oct.14(10):866–872. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Maurer J, Ross NL, Bigos Y, et al. Final Report and Evaluation of the Florida Pentastar Project. Tallahassee: Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services; 1984. Report E-84-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Future Issues in Health Care: Social Policy and the Rationing of Medical Services. New York: Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller L, Clark M, Walter L, et al. The Comparative Evaluation of the Multipurpose Senior Services Project—1981-1982: Final Report. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California; 1984. Grant No. 11-P-97553/9-04. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. Alternatives to Nursing Home Care: A Proposal. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Oct. 1971. Long-term disability: A missing dimension in medical care and public welfare reform. Prepared for Special Committee on Aging, U.S. Senate. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Blenkner M, Bloom M, et al. Older persons after hospitalization: A controlled study of home aide service. Am J Public Health. 1972 Aug.62(8):1094–1101. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.8.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer HC. The alternatives question. In: Vogel RJ, Palmer HC, editors. Long-Term Care: Perspectives from Research and Demonstrations. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1982a. Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer HC. Home care. In: Vogel RJ, Palmer HC, editors. Long-Term Care: Perspectives from Research and Demonstrations. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1982b. Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Papsidero JA, Katz S, Kroger MH, Akpom CA, editors. Chance for Change: Implications of a Chronic Disease Module Study. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Piland NF. Feasibility and Cost-Effectiveness of Alternative Long-Term Care Settings. Menlo Park, Calif.: SRI International; May, 1978. Contract No. SRS-74-39. Prepared for Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Social and Rehabilitation Services, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- *.Pinkerton A, Hill D. Long-Term Care Demonstration Project of North San Diego County: Final Report. San Diego: Allied Home Health Association; 1984. Grant No. 95-P-97325/9-04. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *.Price LC, Ripp HM. Third Year Evaluation of the Monroe County Long-Term Care Program, Inc. Silver Spring, Md.: Macro Systems, Inc.; Nov. 1980. HCFA Grant No. 05-011-P90-130 and AoA Grant No. 2A-50A. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration and Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone-McCuan E, Lohn H. Cost Effectiveness of Geriatric Day Care: A Final Report. Baltimore Md.: Levindale Geriatric Research Center; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchlin HS, Morris JN. Pennsylvania's domiciliary care experiment: II, Cost-benefit implications. Am J Public Health. 1983 Jun;73(6):654–660. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.6.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager A. Learning the Home Care Needs of the Elderly: Patient, Family, and Professional Views of an Alternative to Institutionalization. Waltham, Mass.: The Levison Policy Institute, Brandeis University; Nov. 1979. AoA Grant No. 90-A-1026 (01) (02). Prepared for Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- *.Sainer JS, Brill R, Horowitz A, et al. Delivery of Medical and Social Services to the Homebound Elderly: A Demonstration of Intersystem Coordination. New York: New York City Department for the Aging; 1984. HCFA Grant No. 95-P-97492 and AoA Grant No. 90-AM-2187. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration and Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Scutchfield FD, Freeborn DK. Health Reports. No. 4. Vol. 86. Health Services and Mental Health Administration; Apr. 1971. Estimation of need, utilization, and costs of personal care homes and home health services. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Seidl F, Applebaum R, Austin C, Mahoney K. Delivering In-Home Services to the Aged and Disabled—The Wisconsin Experiment. Madison, Wisc.: Fay McBeath Institute, University of Wisconsin; 1980. Grant No. 11-P-255549/5-05. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *.Shealy MJ, Hicks BC, Quinn JL. Triage: Coordinated Delivery of Services to the Elderly, Final Report. Plainville, Conn.: Triage, Inc.; Dec. 1979. Grant No. HS02563. Prepared for National Center for Health Services Research. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood S, Morris JN. The Pennsylvania domiciliary care experiment: I, Impact on quality of life. Am J Public Health. 1983 Jun;73(6):646–653. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.6.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood S, Greer DS, Morris JN, et al. An Alternative to Institutionalization—The Highland Heights Experiment. Boston: Ballinger; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- *.Sherwood F, Morris JN, Gutkin CE. Department of Gerontological Research, Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for the Aged; 1975. Final Report Concerning the Impact of Services on Health and Weil-Being. HRS Grant No. HS01134. Prepared for Bureau of Health Services Research. [Google Scholar]

- *.Skellie A, Strauss R, Favor F, Tudor C. Alternative Health Services Project Final Report. Atlanta: Georgia Department of Medical Assistance; Jan. 1982. Grant No. 11-P-90334/4-05. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *.Sklar BW, Weiss LJ. Project OPEN: Final Report. San Francisco: Mt. Zion Hospital and Medical Center; Dec. 1983. Grant No. 95-P-97231/9-04. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *.Solem R, Garrick M, Nelson H, et al. Community-Based Care Systems for the Functionally Disabled: A Project in Independent Living. Olympia, Wash.: State of Washington Department of Social and Health Services; Jul, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak S. A Review of Research on Informal Support Systems. Berkeley, Calif.: Berkeley Planning Associates; Mar. 1984. Contract No. 500-80-0073. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Stassen M, Holahan J. A Comparative Analysis of Long-Term Care Demonstrations and Evaluations. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute; Sept. 1980. AoA Grant No. 90-A-1371 (01). Prepared for Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner P, Needleman P. Expanding Long-Term Care Efforts: Options and Issues in State Program Design: A Synthesis of Findings from Health Services Research and Demonstration Projects. Washington, D.C.: Lewin and Associates, Inc.; Mar. 1981. Contract No. 233-79-3018. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JR, Patterson E, Felson L. Effectiveness of home care for general hospital patients. JAMA. 1968 Jul;205(7):145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Thornton C, Dunstan SM. The Evaluation of the National Long-Term Care Demonstration: Analysis of the Benefits and Costs of Channeling. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- *.Thornton C, Will J, Davies M. The Evaluation of the National Long Term Care Demonstration: Analysis of Channeling Project Costs. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Toff GE. Alternatives to Institutional Care for the Elderly: An Analysis of State Initiatives. Washington, D.C.: Intergovernmental Health Policy Project, George Washington University; Sept. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Home Health—The Need for a National Policy to Better Provide for the Elderly. Washington, D.C.: Dec. 1977. GAO Pub. No. HRD-78-19. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Entering a Nursing Home—Costly Implications for Medicaid and the Elderly. Washington, D.C.: Nov. 1979. GAO Pub. No. PAD-80-12. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. The Elderly Should Benefit from Expanded Home Health Care but Increasing These Services Will Not Insure Cost Reductions. Washington, D.C.: Dec. 1982. Pub. No. GAO/IPE-83-1. [Google Scholar]

- Weissert WG. Seven reasons why it is so difficult to make community-based long-term care cost-effective. Health Serv Res. 1985 Oct.20(4):423–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Weissert WG, Wan TTH, Livieratos BB. Effects and Costs of Day Care and Homemaker Services for the Chronically Ill: A Randomized Experiment. Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1980. Pub. No. (PHS) 79-3258. Office of Health Research, Statistics, and Technology, National Center for Health Services Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TF, Hill JG, Fairbank ME, Knox TG. Appropriate placement of the chronically ill and aged: A successful approach by evaluation. JAMA. 1973 Nov.226(11):1332–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wooldridge J, Schore J. The Evaluation of the National Long-Term Care Demonstration: Channeling Effects on Hospital, Nursing Home, and Other Medical Services. Princeton: Mathematica Policy Research; 1986. Contract No. HHS-100-80-0157. Prepared for Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- *.Zawadski RT, Shen J, Yordi C, Hansen J. On Lok's Community Care Organization for Dependent Adults: A Research and Demonstration Project (1978-1983): Final Report. San Francisco: On Lok; Dec. 1984. HCFA Grant No. 95-P-97293 and AoA Grant No. 18-P-00156/9. Prepared for Health Care Financing Administration and Administration on Aging. [Google Scholar]