Abstract

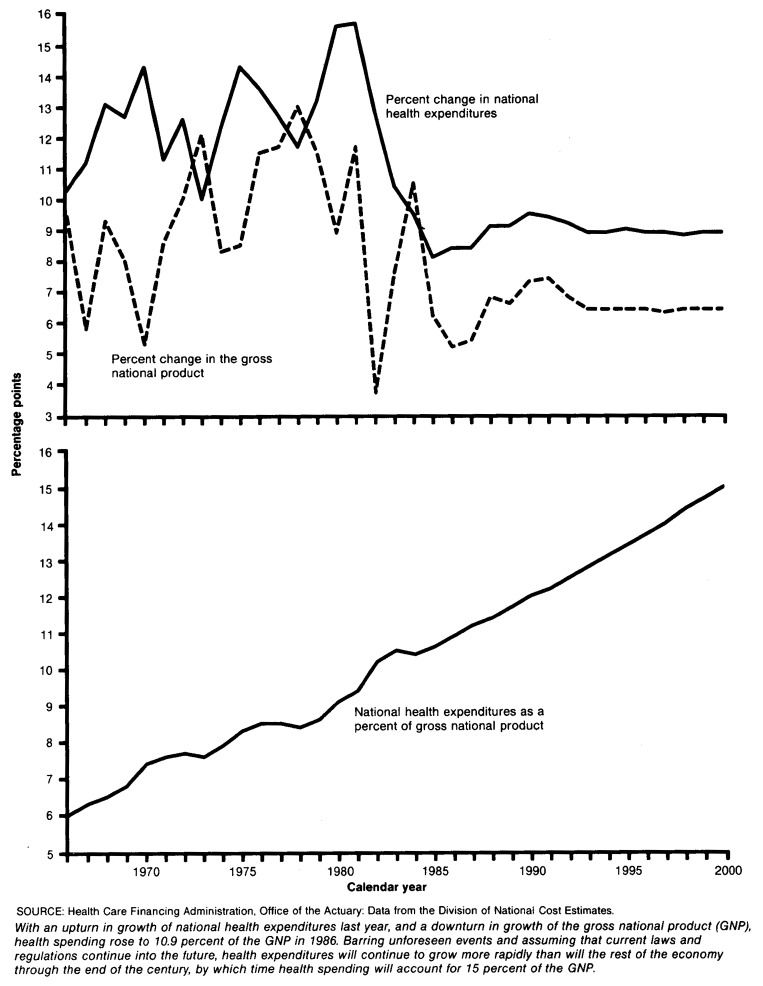

Patterns of spending for health during 1986 and beyond reflect a mixture of adherence to and change from historical trends. From a level of $458 billion in 1986—10.9 percent of the GNP—national health expenditures are projected to reach $1.5 trillion by the year 2000—15.0 percent of the GNP.

This article presents a provisional estimate of spending in 1986 and projections of spending (under the assumption of current law) through the year 2000. Also discussed are the effects of the demographic composition of the population on spending for health, and how spending would increase in the future simply as a result of the evolution of that composition.

National health expenditures in 1986

Nationwide in 1986, a total of $458 billion was spent for health, an amount equal to 10.9 percent of the gross national product (GNP). The growth of that spending accelerated slightly in 1986 to a rate of 8.4 percent, following an 8.1 percent increase in 1985. Most of the acceleration is accounted for by higher price inflation.

Spending for health rose more rapidly between 1985 and 1986 than did the GNP, so that spending as a share of the GNP rose from 10.6 to 10.9 percent. This increase is attributable less to acceleration of health spending than it is to a sluggish performance by the economy as a whole. The 8.4 percent growth in national health expenditures from 1985 to 1986 was the second lowest in over two decades, but so was the 5.2 percent growth in nominal GNP.

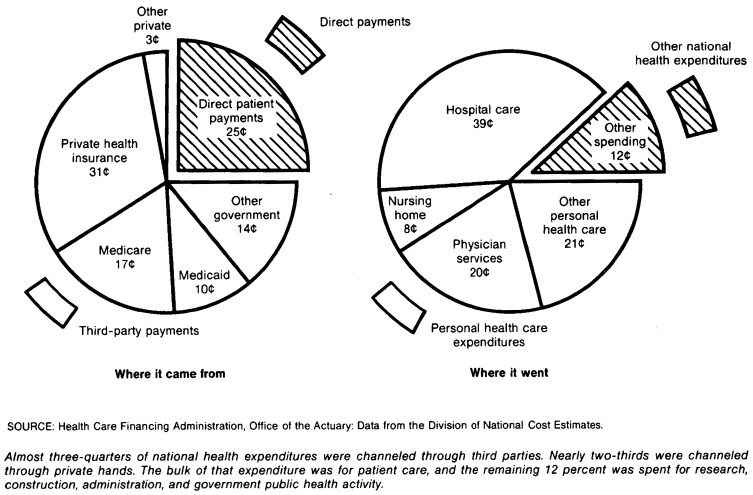

As shown in Tables 12-21 at the end of this article, spending for health in the United States during 1986 amounted to an allocation of resources equal to $1,837 per person. Roughly 60 percent of those funds were channeled through private hands, either patients themselves or private health insurers. The remaining 40 percent was channeled through Federal, State, or local governments, mainly through the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Table 12. National health expenditures aggregate and per capita amounts, percent distribution, and average annual percent change, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-2000.

| Item | 2000 | 1995 | 1990 | 1987 | 1986 | 1985 | 1984 | 1980 | 1970 | 1965 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $1,529.3 | $999.1 | $647.3 | $496.6 | $458.2 | $422.6 | $391.1 | $248.1 | $75.0 | $41.9 |

| Private | 879.4 | 575.5 | 378.2 | 294.8 | 268.5 | 246.6 | 231.3 | 142.9 | 47.2 | 30.9 |

| Public | 649.9 | 423.5 | 269.0 | 201.7 | 189.7 | 176.0 | 159.7 | 105.2 | 27.8 | 11.0 |

| Federal | 498.6 | 317.7 | 195.5 | 142.7 | 134.7 | 124.5 | 111.6 | 71.0 | 17.7 | 5.5 |

| State and local | 151.3 | 105.8 | 73.6 | 59.0 | 55.0 | 51.5 | 48.1 | 34.2 | 10.1 | 5.5 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $5,551 | $3,739 | $2,511 | $1,973 | $1,837 | $1,710 | $1,597 | $1,054 | $349 | $205 |

| Private | 3,192 | 2,154 | 1,467 | 1,172 | 1,076 | 998 | 945 | 607 | 220 | 152 |

| Public | 2,359 | 1,585 | 1,044 | 802 | 760 | 712 | 652 | 447 | 129 | 54 |

| Federal | 1,810 | 1,189 | 758 | 567 | 540 | 504 | 456 | 302 | 82 | 27 |

| State and local | 549 | 396 | 285 | 235 | 221 | 208 | 196 | 145 | 47 | 27 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 57.5 | 57.6 | 58.4 | 59.4 | 58.6 | 58.4 | 59.2 | 57.6 | 63.0 | 73.8 |

| Public | 42.5 | 42.4 | 41.6 | 40.6 | 41.4 | 41.6 | 40.8 | 42.4 | 37.0 | 26.2 |

| Federal | 32.6 | 31.8 | 30.2 | 28.7 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 28.5 | 28.6 | 23.6 | 13.2 |

| State and local | 9.9 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 13.0 |

| Average annual percent change from previous year shown | ||||||||||

| U.S. population | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | — |

| Gross national product | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 7.6 | — |

| National health expenditures | 8.9 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 12.0 | 12.7 | 12.3 | — |

| Private | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 8.9 | 6.6 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 8.8 | — |

| Public | 8.9 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 14.2 | 20.4 | — |

| Federal | 9.4 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 14.9 | 26.1 | — |

| State and local | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 13.0 | 13.1 | — |

| Number in millions | ||||||||||

| U.S. population1 | 275.5 | 267.2 | 257.8 | 251.6 | 249.5 | 247.2 | 244.9 | 235.3 | 214.9 | 204.1 |

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Gross national product | $10,164 | $7,467 | $5,414 | $4,433 | $4,206 | $3,998 | $3,765 | $2,732 | $1,015 | $705 |

| Percent of gross national product | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 15.0 | 13.4 | 12.0 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 5.9 |

July 1 social security area population estimates.

NOTE: Figures for 1986 are preliminary and those for 1987-2000 are projected.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 21. Financial experience of private health insurers, by type of insurance: Calendar years 1977-86.

| Item and insurance type | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 19861 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Total premiums earned | $48.0 | $53.6 | $62.0 | $72.6 | $84.4 | $98.7 | $109.7 | $121.5 | $130.1 | $140.7 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 19.6 | 21.5 | 23.5 | 26.3 | 30.4 | 34.3 | 37.6 | 40.0 | 41.5 | 44.6 |

| Blue Cross | 13.6 | 14.9 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 20.7 | 23.3 | 25.6 | 27.2 | 28.2 | 30.3 |

| Blue Shield | 5.9 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 14.4 |

| Insurance companies | 19.1 | 21.1 | 24.4 | 28.9 | 34.0 | 41.4 | 46.9 | 50.9 | 53.1 | 55.5 |

| Group policies | 15.6 | 16.9 | 18.7 | 20.0 | 22.1 | 24.3 | 27.1 | 26.6 | 27.3 | 28.2 |

| Individual policies | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| Minimum premium plans | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 12.9 | 15.1 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 21.0 |

| Self-insured plans | 7.2 | 8.4 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 18.4 | 22.7 | 26.2 | 30.3 |

| Administrative services only | 3.2 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 14.0 |

| Self-administered | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 11.0 |

| Third-party administered | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 5.3 |

| Prepaid health plans | 2.2 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 9.4 | 10.3 |

| Total benefits incurred | 43.0 | 49.1 | 56.9 | 67.5 | 78.4 | 89.9 | 98.0 | 104.9 | 113.0 | 122.9 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 17.8 | 19.5 | 21.7 | 25.5 | 29.2 | 32.1 | 34.4 | 35.5 | 37.5 | 41.1 |

| Blue Cross | 12.7 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 17.5 | 20.1 | 22.2 | 23.6 | 24.2 | 25.8 | 27.9 |

| Blue Shield | 5.2 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 11.8 | 13.1 |

| Insurance companies | 16.4 | 19.1 | 21.8 | 25.8 | 30.3 | 36.4 | 40.1 | 41.3 | 43.1 | 45.0 |

| Group policies | 14.0 | 15.7 | 17.0 | 18.2 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 22.8 | 20.6 | 21.4 | 22.3 |

| Individual policies | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.2 |

| Minimum premium plans | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 12.0 | 14.2 | 17.1 | 17.7 | 18.5 |

| Self-insured plans | 6.8 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 16.0 | 17.3 | 21.0 | 24.1 | 27.7 |

| Administrative services only | 3.1 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 12.3 |

| Self-administered | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 10.4 |

| Third-party administered | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 5.0 |

| Prepaid health plans | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 8.3 | 9.1 |

| Net cost of private health insurance | 5.1 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 16.6 | 17.1 | 17.8 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| Blue Cross | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Blue Shield | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Insurance companies | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.5 |

| Group policies | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| Individual policies | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Minimum premium plans | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Self-insured plans | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Administrative services only | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Self-administered | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Third-party administered | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Prepaid health plans | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Administration expenses | $5.2 | $5.9 | $6.7 | $7.9 | $9.4 | $11.2 | $12.8 | $14.3 | $16.3 | $17.8 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Blue Cross | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Blue Shield | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Insurance companies | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 10.8 |

| Group policies | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.6 |

| Individual policies | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Minimum premium plans | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Self-insured plans | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Administrative services only | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Self-administered | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Third-party administered | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Prepaid health plans | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Net underwriting gain or loss | −0.2 | −1.4 | −1.6 | −2.8 | −3.4 | −2.5 | −1.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −0.3 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.2 | −0.8 |

| Blue Cross | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 | −0.7 | −0.3 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | −0.2 |

| Blue Shield | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.5 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.6 |

| Insurance companies | −0.8 | −1.8 | −1.7 | −1.8 | −2.3 | −2.4 | −1.7 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.3 |

| Group policies | −0.5 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −2.1 | −1.0 | 0.5 | −0.2 | −0.7 |

| Individual policies | −0.2 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −0.6 | −0.7 | −0.9 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.3 |

| Minimum premium plans | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Self-insured plans | 0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Administrative services only | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Self-administered | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Third-party administered | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Prepaid health plans | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Percent | ||||||||||

| Loss ratio | 89.5 | 91.6 | 91.8 | 93.0 | 92.9 | 91.1 | 89.3 | 86.3 | 86.8 | 87.3 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 91.2 | 90.3 | 92.6 | 96.7 | 95.9 | 93.6 | 91.5 | 88.9 | 90.4 | 92.0 |

| Blue Cross | 93.1 | 90.6 | 94.2 | 97.2 | 97.1 | 95.3 | 92.3 | 89.1 | 91.5 | 92.3 |

| Blue Shield | 86.6 | 89.8 | 89.0 | 95.6 | 93.3 | 90.0 | 89.6 | 88.5 | 88.2 | 91.3 |

| Insurance companies | 86.2 | 90.5 | 89.5 | 89.1 | 89.1 | 87.9 | 85.6 | 81.2 | 81.2 | 81.1 |

| Group policies | 90.1 | 93.3 | 91.0 | 91.1 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 83.8 | 77.5 | 78.6 | 79.2 |

| Individual policies | 61.3 | 70.3 | 70.5 | 66.5 | 68.2 | 67.7 | 67.7 | 68.9 | 68.0 | 66.7 |

| Minimum premium plans | 98.4 | 97.9 | 100.6 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 92.8 | 94.1 | 89.6 | 88.6 | 87.9 |

| Self-insured plans | 94.6 | 98.2 | 95.5 | 94.2 | 95.4 | 93.7 | 94.3 | 92.5 | 92.0 | 91.7 |

| Administrative services only | 98.5 | 97.9 | 98.7 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 92.8 | 94.1 | 89.6 | 88.6 | 87.9 |

| Self-administered | 91.1 | 99.1 | 92.2 | 91.3 | 93.6 | 94.3 | 94.3 | 94.9 | 94.9 | 94.9 |

| Third-party administered | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.3 | 94.3 | 95.1 |

| Prepaid health plans | 85.6 | 89.7 | 90.4 | 92.3 | 91.9 | 91.9 | 90.3 | 88.7 | 88.3 | 88.3 |

| Combined ratio | 100.4 | 102.6 | 102.6 | 103.9 | 104.0 | 102.5 | 101.0 | 98.1 | 99.3 | 100.0 |

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | 98.0 | 97.3 | 99.9 | 104.1 | 103.3 | 100.8 | 98.7 | 96.8 | 99.4 | 101.8 |

| Blue Cross | 98.2 | 96.0 | 100.1 | 103.3 | 103.3 | 101.4 | 98.4 | 95.8 | 99.2 | 100.8 |

| Blue Shield | 97.3 | 100.2 | 99.4 | 105.8 | 103.3 | 99.6 | 99.2 | 99.0 | 99.8 | 103.9 |

| Insurance companies | 104.0 | 108.4 | 107.0 | 106.4 | 106.6 | 105.8 | 103.6 | 99.1 | 100.2 | 100.5 |

| Group policies | 103.5 | 107.5 | 106.0 | 107.4 | 106.8 | 108.8 | 103.8 | 98.2 | 100.6 | 102.6 |

| Individual policies | 107.1 | 116.3 | 115.0 | 108.9 | 117.9 | 116.5 | 120.2 | 123.8 | 123.4 | 120.6 |

| Minimum premium plans | 102.4 | 101.8 | 104.6 | 101.0 | 101.7 | 96.6 | 98.2 | 93.6 | 93.0 | 91.8 |

| Self-insured plans | 99.3 | 103.0 | 99.9 | 99.0 | 100.3 | 98.6 | 99.3 | 97.4 | 97.0 | 96.5 |

| Administrative services only | 102.4 | 101.8 | 102.7 | 100.9 | 101.7 | 96.6 | 98.2 | 93.6 | 93.0 | 91.8 |

| Self-administered | 96.7 | 105.2 | 97.3 | 97.4 | 99.7 | 100.6 | 100.7 | 101.3 | 101.3 | 101.3 |

| Third-party administered | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 98.9 |

| Prepaid health plans | 93.5 | 97.6 | 99.3 | 101.2 | 100.8 | 100.9 | 100.7 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Provisional estimates.

NOTE: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million for aggregate amounts, and 0 denotes less than $.50 for per capita amounts.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Industry summary

Before examining expenditure patterns, it may be useful to consider some of the trends evinced by the health industry itself. These trends demonstrate some interesting aspects of the demand for health care and shed some light on patterns within the industry.

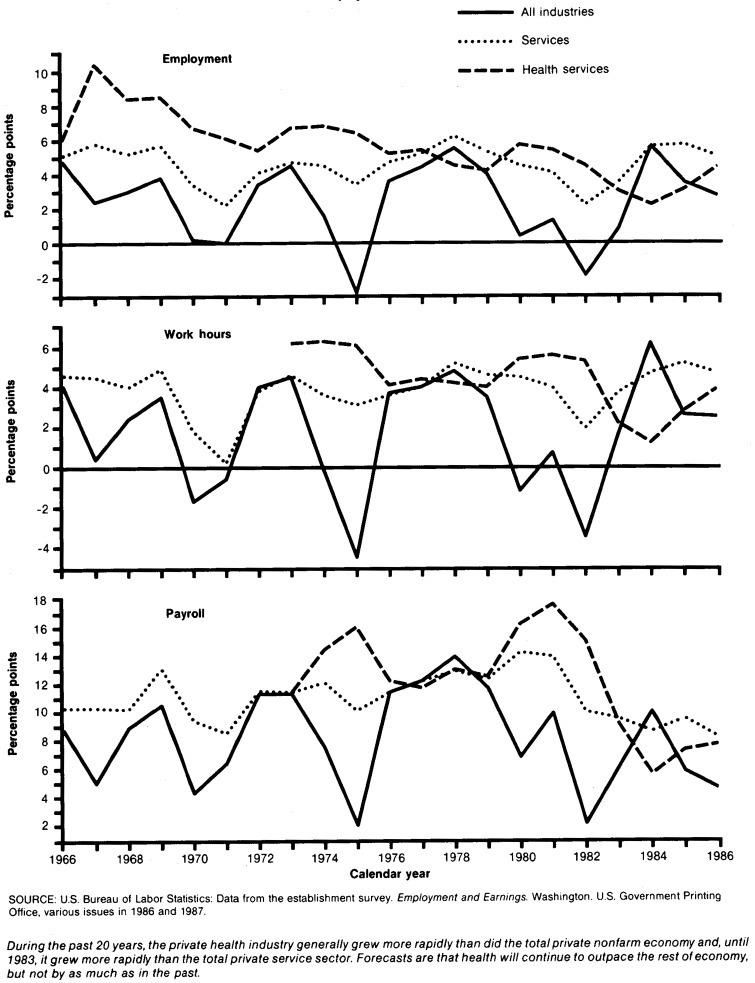

In terms of employment, the health services industry is still recovering from a short-term dip in economy share. The trend in the private health services industry share of total employment is quite pronounced: that share nearly doubled from 1965 to 1983. However, the growing effects of cost containment (including a large degree of uncertainty) served to depress employment growth after 1983. Coupled with substantial industrial growth elsewhere in the economy in 1984, this produced a slight dip in the health industry share of total nonfarm employment. There is reason to expect that that share will resume its rise, but perhaps at a lower rate than has been seen historically.

The growth of hours worked and of payroll in the private health sector has followed a pattern similar to that of employment (Table 1). Generally speaking, both have outpaced their economy-wide counterparts, frequently by substantial amounts. On the other hand, recent years have seen a different pattern. Following nearly identical growth rates in 1983, the total private nonfarm economy handily outperformed the health industry in 1984. Again in 1985, the two groups performed very similarly, and only in 1986 did the health industry re-emerge with faster growth. The effects of cost containment seem to have reduced the annual rate of growth, but it is too early to tell whether that shift is a shortrun or a longrun phenomenon.

Table 1. Annual percent change in employment, hours, and earnings in selected components of the private nonfarm economy: Selected periods and calendar years 1965-86.

| Item | 1965-70 | 1970-75 | 1975-80 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Annual percent change | |||||||||

| All private nonfarm industries | |||||||||

| Total employment | 2.8 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 1.3 | −1.9 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 2.7 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: | |||||||||

| Employment | 2.6 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.0 | −2.4 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| Workhours | 1.7 | 0.6 | 3.0 | 0.7 | −3.5 | 1.6 | 6.2 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| Payroll | 7.4 | 7.7 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 4.6 |

| All private service industries | |||||||||

| Total employment | 5.0 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.0 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: | |||||||||

| Employment | 4.8 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 4.7 |

| Workhours | 4.0 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.7 |

| Payroll | 10.6 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 8.2 |

| Private health services (SIC 80) | |||||||||

| Total employment | 8.0 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 4.4 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: Employment | — | — | 4.8 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.2 |

| Workhours | — | — | 4.4 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Payroll | — | — | 13.1 | 17.6 | 15.0 | 9.1 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Offices of physicians and surgeons (SIC 801) | |||||||||

| Total employment | — | — | 5.3 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 6.6 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: | |||||||||

| Employment | — | — | 4.4 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 7.9 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 6.3 |

| Workhours | — | — | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 7.3 |

| Payroll | — | — | 12.5 | 15.6 | 8.3 | 12.9 | 5.2 | 8.8 | 11.8 |

| Nursing and personal care facilities (SIC 805) | |||||||||

| Total employment | — | — | 5.6 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 6.1 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: | |||||||||

| Employment | — | — | 5.4 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 |

| Workhours | — | — | 5.2 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 6.7 |

| Payroll | — | — | 13.5 | 13.9 | 13.1 | 10.0 | 7.2 | 9.2 | 10.3 |

| Private hospitals (SIC 806) | |||||||||

| Total employment | 6.6 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 5.6 | 3.8 | 0.7 | −1.1 | −0.2 | 1.5 |

| Nonsupervisory workers: | |||||||||

| Employment | — | 3.8 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 0.6 | −1.5 | −0.3 | 1.4 |

| Workhours | — | 4.1 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 5.5 | −0.6 | −1.5 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Payroll | — | 12.0 | 12.5 | 18.3 | 17.0 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| Total employment in government hospitals | — | — | — | 0.1 | −0.4 | −0.9 | −2.2 | −0.5 | 1.0 |

| Total employment in private and government hospitals combined | — | — | — | 4.3 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

NOTE: SIC is Standard Industrial Classification.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Data from the establishment survey. Employment and Earnings. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, various issues in 1986 and 1987.

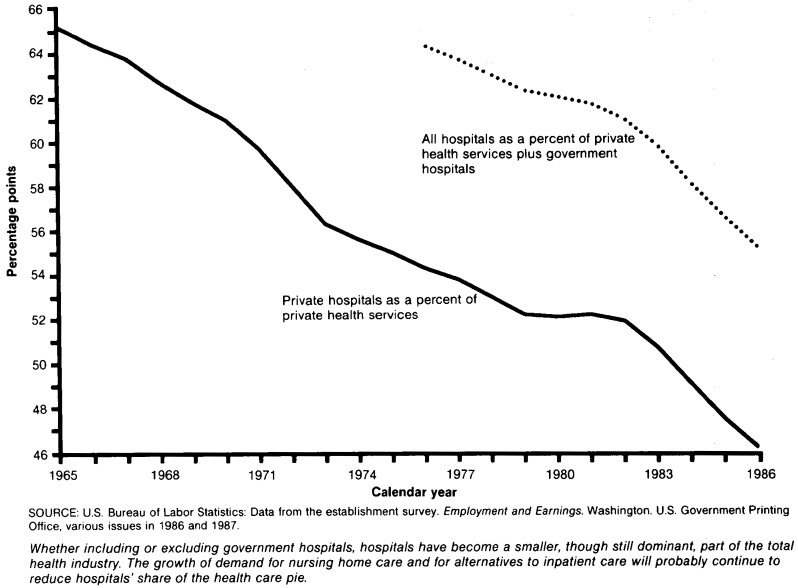

Within the health industry, however, one very clear longrun trend is the increasing importance of providers outside of hospitals. In 1976, hospital employment (including government hospitals) accounted for almost two-thirds of all health service employment; a decade later, that share had fallen to 55 percent. There can be no doubt that cost containment has played a role in this trend. The rate of decline increased markedly after 1982, coincident with the beginning of the drop in hospital admissions.

The trends in health services employment, hours, and earnings are consistent with our understanding of the U.S. economy. Health care is principally a service, and service industries tend to grow more rapidly than do manufacturing or agriculture as an economy reaches the level of maturity currently evinced in the United States. Most of this growth stems from the longrun income elasticity of demand for services in general (and for health care in particular). Also, third-party financing obscured the true price of health care, leading consumers to use more of it than they otherwise would have done. In addition, health care increasingly had come to be treated not as just another commodity in the consumer's market basket, but rather as a socially ensured right of existence. Consequently, the market demand for health care took a life of its own, independent of price and income pressures. It was not until the early-to mid-1980's that private industry, followed by government, began to challenge the social perception of health care as a right rather than as a part of a total consumption market basket. The ensuing interactions between consumers, providers, and financers have modified the long-term trends in growth, at least for the short run.

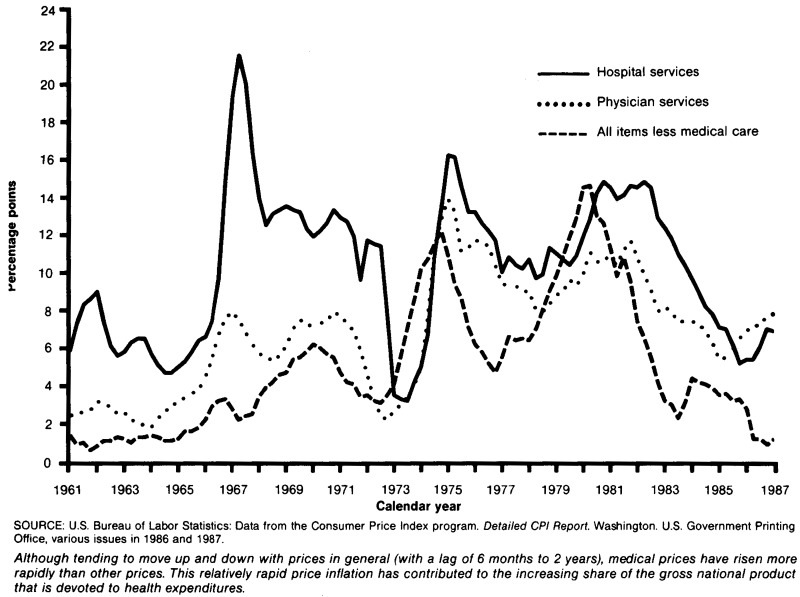

Price inflation is another area in which the health industry differs from other parts of the U.S. economy. Prices paid by consumers for medical care rose 7.7 percent from December 1985 to December 1986, 1 percent faster than the 1984-85 change. Taken together, the 12 months of 1986 averaged 7.5 percent higher than the 12 months of 1985 (Table 2).

Table 2. Annual percent change in selected components of the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers: 1970-86.

| Item | 1970-75 | 1975-80 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Annual percent change | ||||||||

| All items | 6.7 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 1.9 |

| All items less energy | 6.5 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 6.7 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Medical care | 6.9 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 8.7 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 7.5 |

| Medical care services | 7.6 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 11.9 | 8.7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 7.7 |

| Professional services | 6.6 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 6.1 | 6.4 |

| Physicians' services | 6.9 | 9.7 | 11.0 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 7.2 |

| Dental services | 6.3 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 5.6 |

| Other professional services1 | — | — | 9.4 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 6.9 | 5.4 |

| Other medical care services2 | 8.7 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 15.0 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 8.8 |

| Hospital and other medical services1 | — | — | 14.2 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 8.6 | 6.4 | 6.0 |

| Hospital room | 10.2 | 12.2 | 14.8 | 15.7 | 11.3 | 8.3 | 5.9 | 6.0 |

| Other hospital and medical care services1 | — | — | 13.9 | 12.8 | 11.4 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 6.0 |

| Medical care commodities | 2.8 | 7.2 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.6 |

| Prescription drugs | 1.6 | 7.2 | 11.4 | 11.7 | 10.9 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 8.6 |

| Nonprescription drugs and medical supplies1 | — | — | 10.5 | 9.1 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| Eyeglasses1 | — | — | 6.9 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 |

| Internal and respiratory over-the-counter drugs | 4.1 | 7.7 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 4.9 |

| Nonprescription medical equipment and supplies1 | — | — | 9.2 | 9.3 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.9 |

| All items less medical care | 6.7 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 1.5 |

| Food and beverages | 8.4 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 3.2 |

| Housing | 6.8 | 9.9 | 11.5 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 2.9 |

| Shelter | 6.5 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 7.1 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| Fuel and other utilities | 9.3 | 10.7 | 14.6 | 9.9 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 1.6 | −2.3 |

| Apparel and upkeep | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Transportation | 6.0 | 10.6 | 12.1 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 2.6 | −3.9 |

| Gasoline | 10.1 | 16.7 | 11.3 | −5.3 | −3.3 | −1.6 | 0.8 | −21.9 |

| Entertainment | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| Other goods and services | 5.7 | 6.9 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

| Commodities | 6.9 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.1 | −1.0 |

| Services | 6.5 | 10.2 | 13.1 | 9.0 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.0 |

| Services less medical care | 6.3 | 10.1 | 13.4 | 8.7 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

Not available prior to December 1977.

Comprises hospital and other medical (nursing home) services and private health insurance (not calculated separately).

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Data from the Consumer Price Index program. Detailed CPI report. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, various issues in 1986 and 1987.

This acceleration in health care price inflation came at a time when the rate of increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all items had slowed dramatically. The aggregate CPI change from 1985 to 1986 was only 1.9 percent, the lowest growth of the last two decades. Gasoline prices had dropped 22 percent and other energy prices had also fallen, although not nearly as much.

However, it is not entirely appropriate to compare the CPI for medical care with the CPI for all items on their face values. First, the deep cuts in gasoline prices masked an underlying inflation rate of 3.9 percent in other categories of goods and services; the 13.2 percent deflation seen in energy prices did not translate into price cuts elsewhere. Second, service prices in general (including household utility prices) rose 5.0 percent from 1985 to 1986, compared with a drop of 1.0 percent in commodity prices. Service prices, in general, are likely to rise faster than commodity prices, because of lower productivity growth in the labor-intensive service sector. Thus, when evaluating health care prices, it is more appropriate to use service prices as a gauge than it is to use all prices. Third, the CPI for medical care contains a conceptual “price” of health insurance, which is not strictly a personal health care item. In the absence of this insurance component, the CPI for medical care would have risen 6.2 percent from 1985 to 1986. When looking at the relative growth of medical care prices, then, the best comparison may be between 6.2 percent and 5.0 percent. However, although less dramatic than the difference between the change in the CPI for medical care and the change in the CPI for all items, this margin is substantial in its own right.

Within the medical care “market basket” priced for the CPI, the largest price increase—8.6 percent—was for prescription drugs. Physician fees were up 7.2 percent and hospital prices increased 6.0 percent.

Use of community hospital services

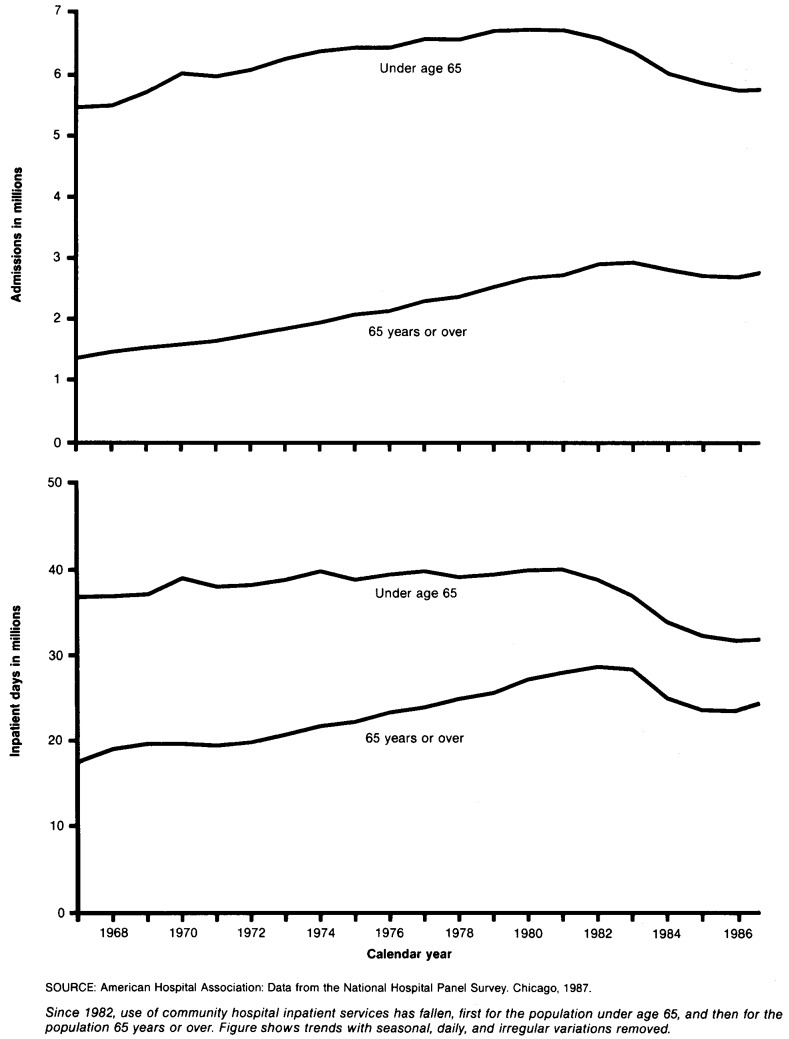

A substantial portion of the slowdown in growth of personal health care spending in recent years is attributable to changes in the use of community hospital services.

The effect of private sector initiatives to reduce hospital use appear to predate by about 2 years those of the more well known Medicare prospective payment system (PPS). Inpatient days for people under 65 years of age began to fall in mid-1981, as did admissions for that group. Days and admissions for the population 65 years of age or over began to fall in mid-1983, just into the first phase of PPS. Although some of the change in use by those under age 65 may be attributable to government programs such as Medicaid, the principal source of payment for that part of the population is private insurance. The latter group found itself under pressure from employers to reduce health care costs when insurance premiums became a major labor cost late in the 1970's.

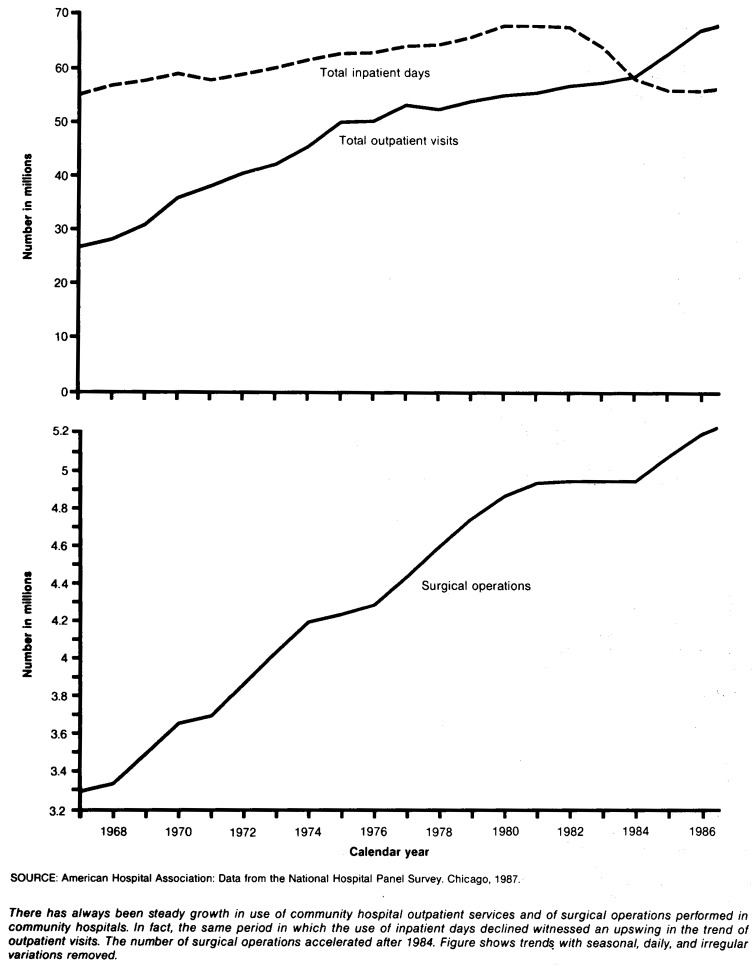

Although total inpatient days have fallen since early in 1983, the opposite has occurred for outpatient visits. In fact, the trend of growth of visits began to accelerate early in 1985. Part of this phenomenon may be attributable to the changes in the sites that were once used for inpatient services. Many insurers encouraged patients to have preadmission testing done on an outpatient basis rather than an inpatient basis; other procedures, such as lens implantation, were moved from an inpatient to an outpatient setting in their entirety. Although the bulk of hospitals' revenue continues to come from inpatient services, outpatient visits began to outnumber inpatient days beginning in 1985, a change that appears to be permanent.

One other trend in community hospital use that may be worth examination is that of surgical procedures, because surgery tends to be associated with use of intensive (and expensive) hospital services. Beginning in 1981, the slope of the trend line flattened rather abruptly, and the number of operations remained roughly unchanged for 4 years. Beginning in 1985, however, the trend line resumed its former growth, a resumption that continued unabated through 1986.

The patterns of use of community hospital services demonstrate three things about that use. First, inpatient services have experienced a major reversal in trend. Admissions are at a 16-year low for patients under age 65 and at a 5-year low for patients 65 years of age or over; inpatient days are at an 18-year low. Second, hospitals have had some success in recovering those inpatient services in an outpatient setting. Third, surgical procedures in aggregate seem to be back on historical trendlines.

Elements of national health expenditures

Personal health care

Total spending for the direct provision of medical care goods and services—personal health care expenditures—amounted to $404 billion in 1986, 8.8 percent more than in 1985. That is an amount equal to $1,620 per person and represents 12 percent of U.S. personal income.

Compared with 1985 estimates, the data for 1986 indicate a slight increase in the direct patient payment share of personal health care expenditures, 28.7 percent of the total, up from 28.4 percent. There are a number of partial explanations of that increase. For example, almost one-fifth of it is attributable to the Medicare program. Medicare coinsurance and deductible amounts were increased in 1986, reaching an aggregate level of $12.7 billion. There is anecdotal evidence of similar changes in private health insurance programs as well. In addition, the 1986 national health expenditures estimates are preliminary, and subsequent data revisions may reduce or even reverse the change in the direct payment share of total spending.

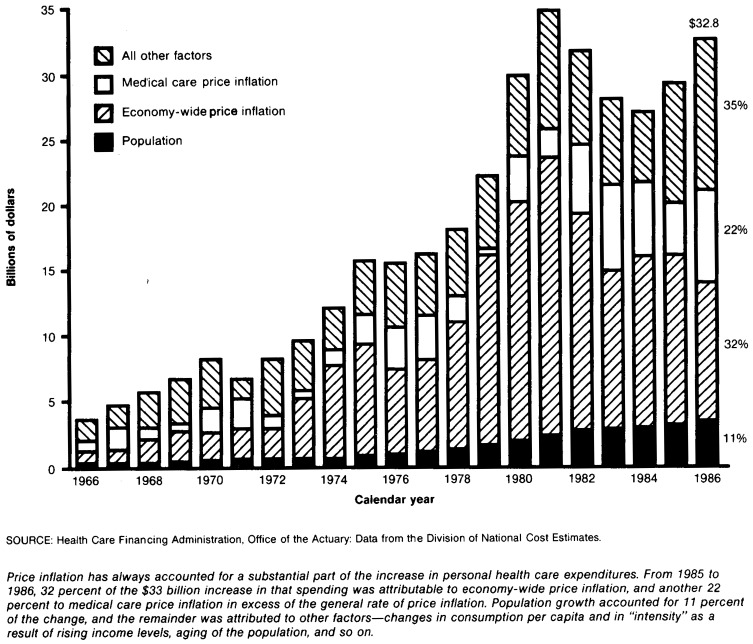

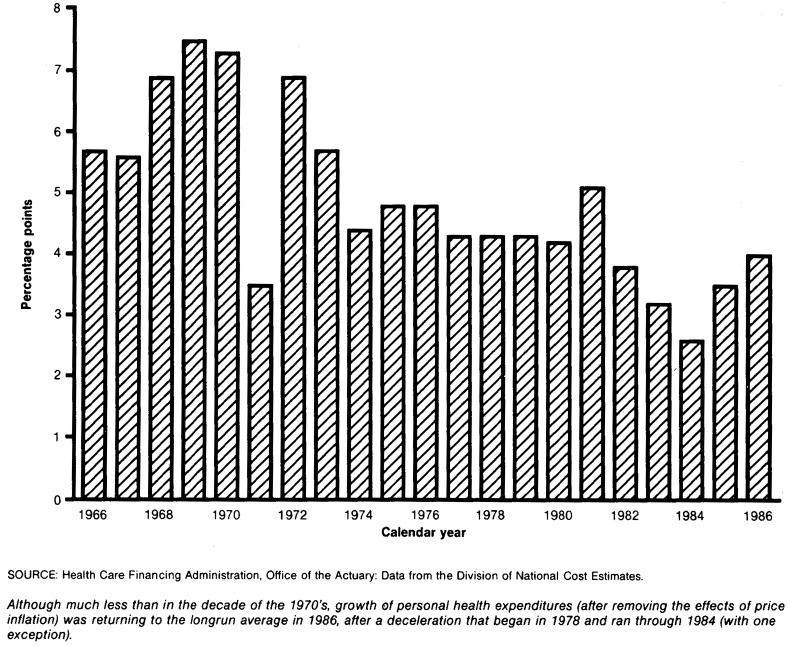

A substantial proportion of the increase in personal health care expenditures is attributable to price inflation, but the underlying trend in spending has been essentially unchanged for the last decade. Price inflation—both economy-wide and health-specific—accounted for 54 percent of the 1985-86 change in personal health care expenditures. Population growth accounted for another 11 percent, and the remaining 35 percent is attributable to changes in consumption per capita and in the “intensity” of consumption because of demographic change of the population, changes in income levels and distribution, and so on. Personal health care expenditures grew about 4 percent from 1985 to 1986 (after removing the effects of price inflation), close to the 10-year average growth in “real” (price-deflated) spending.

Another way to measure the changing effect of personal health care spending on society is to measure the “opportunity cost” of consumption. The opportunity cost of health care consumption is defined to be the amount of other goods and services society could have purchased with the same amount of money. Constant-dollar opportunity cost, which allows us to measure change over time, is measured by deflating personal health expenditures by the CPI for all items except health care. That opportunity cost rose 7.2 percent from 1985 to 1986 (largely as a result of lower energy prices), well above the 1965-85 average rate of 5.8 percent.

A third measure of the effect of health care spending on consumers is the share of personal income that that spending represents. This measure shows what portion of the Nation's household budget is devoted to health. Personal health care expenditures as a fraction of personal income grew from 11.2 percent in 1985 to 11.6 percent in 1986, a relative increase of 3.5 percent. Had personal health expenditures grown at the same rate as personal income, consumers would have had $13.6 billion more to spend on other goods and services.

Hospital care

Hospital revenues in 1986 amounted to $180 billion, 7.4 percent more than in 1985. Most of that money came from third parties. Private health insurers paid 36 percent of the total, Medicare and Medicaid paid 38 percent, and other government programs paid 15 percent. However, the amount paid directly by consumers increased disproportionately from 1985 to 1986, from 8.7 percent to 9.4 percent.

The increase in the direct payment portion of hospital revenues is attributable to changes in third-party financing and in coverage. Medicare beneficiaries were liable for increased deductible and coinsurance amounts in 1986, because of changes in the cost per day of hospital care. Many privately insured employees and dependents faced similar changes in copayment schedules, as employers sought to shift some of the cost of health care back to workers. In addition, there is evidence that the number of uninsured people in the United States is increasing (Sulvetta and Schwartz, 1986), raising the amount of consumer liability.

Concommitant with the increased direct payment share of hospital spending, the Medicare share of spending dropped from 1985 to 1986, the first decrease since the early 1970's. This decline can be traced back to relatively low growth in Medicare payments per admission; the share of community hospital inpatient days and admissions accounted for by patients 65 years of age or over was unchanged from 1985 to 1986.

New data from the American Hospital Association's annual survey of hospitals have resulted in revised estimates of hospital spending in 1984 and 1985. The new 1984 estimate is 0.6 percent higher than reported previously, and the 1985 estimate has been raised 0.3 percent.

Physician services

Spending for the services of physicians reached $92 billion in 1986, an increase of 11.1 percent from 1985.

Data on use of physician services show mixed growth. For example, both hospital admissions and inpatient days were lower in 1986 than in 1985, suggesting fewer physician contacts in an inpatient setting. On the other hand, emergency room visits grew 6.2 percent (American Hospital Association, 1987), implying increased outpatient contact. Further, the number of surgical procedures performed in community hospitals increased 2.2 percent, an indication that surgical income had increased as well. (Estimates of office visits were not available when this article was written, so the trend in that part of physician activity is not clear.)

Data on employment and hours suggest strong growth in physician activity in 1986. Total employment in offices of physicians and surgeons (Standard Industrial Classification 801) increased 6.6 percent, and hours worked by nonsupervisory employees increased 7.3 percent; both these figures were the highest in a decade (Table 1). Nonsupervisory payroll was up 11.8 percent from 1985, again suggesting considerable strength in office business.

The 1986 estimates of expenditure for physician services embody a shift of financing from private health insurance to direct payment. There is a substantial body of anecdotal evidence suggesting that privately insured people are paying higher proportions of their health bills in the form of copayments, which supports the shift observed in financing shares. Further, we estimate that “reasonable charge reductions” under Medicare Part B—the difference between what is billed and what the program recognizes as valid charges—will be shown to have increased some $200 million from 1985 to 1986; these reductions are the beneficiary's liability. On the other hand, the Medicare Part B deductible ($75 per year) was unchanged from 1985, effectively lowering the beneficiary share of total Part B allowed charges. The net effect of these occurrences is unclear.

Nursing home care

We estimate the 1986 revenue of nursing homes to be $38 billion, up 9.1 percent from 1985.

In the estimates presented in this article, the Medicaid share of total expenditures has been falling. This may be attributable to State efforts at containment of total program costs. Medicaid certification has been tightened (Weissert et al., 1983), and nursing homes are giving priority to private pay patients. Recent General Accounting Office reports on access to care underscored this trend and added the observation that hospitals are encountering increasing difficulty in placing Medicare patients as well (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1983, 1987). Both of these phenomena may be reflected in the upward trend in the direct payment share of total nursing home expenditures.

Other personal health care

In addition to the three large expenditures categories mentioned previously, $94 billion was spent in 1986 for other personal health care. That amount—9.2 percent more than in 1985—was used to purchase dental care, drugs and drug sundries, eyeglasses and other medical commodities, home health and other professional services, and other medical goods and services.

Home health services comprise about one-third of the category called “other professional services.” Although an estimate of total industry activity is not yet available1, it may be possible to infer trends in the whole by examining Medicare reimbursement for home health services, often placed at one-half of industry activity. That reimbursement—$2.0 billion in 1986—increased about 10.5 percent both in 1985 and in 1986, down sharply from the 31.2-percent average for 1973-84. The slowdown was attributable in part to payment delays in fiscal year 1986 resulting from introduction of a new bill form and new reporting requirements.

Other national health expenditures

In addition to personal health care expenditures, $54 billion was spent in 1986 for other categories of health.

Government public health activity, programs such as those at the Centers for Disease Control which target diseases and conditions rather than beneficiary populations, cost $13 billion, increasing 9.2 percent—a rate consistent with historical experience.

The cost of administering public and private health programs, plus the net cost of private health insurance—the difference between earned premiums and incurred benefits—amounted to $24.5 billion. New data on commercial insurance carrier experience in 1985 have led to a downward revision of previously published estimates for this category, resulting in a growth of 4.7 percent from 1984 to 1985, and of 3.8 percent from 1985 to 1986.

Noncommercial biomedical research consumed $8 billion in 1986, and another $8 billion was put in place as new hospital and institutional construction. The continued decline in construction is attributable to falling occupancy rates and to the uncertainty created by cost containment programs such as PPS regarding the future of inpatient care and capital reimbursement.

Financing health expenditures

The estimates of 1986 health spending shown in this report reflect the changes in financing of care that have been occurring over the last 4 years.

Medicare

Facing hospital insurance trust fund insolvency near the turn of the century, the Medicare administrators have actively sought ways to reduce spending while maintaining or improving the quality of care provided to more than 31 million aged and disabled program enrollees.

Medicare program benefits amounted to $76 billion in 1986, 7.8 percent more than in 1985. Because of the nature of the program, two-thirds of benefit payments were for hospital services; almost all of the remainder were for physician services. Nationwide, Medicare is the largest single purchaser of hospital care and physician services, accounting for 29 percent of all hospital revenue and for 21 percent of physician services.

Now in the third year of PPS, Medicare has actively sought to make hospitals more prudent providers of care. The decline in length of stay for the population age 65 or over, 98 percent of whom are eligible for Medicare hospital benefits, is attributable largely to the incentives created by PPS. The decline in admissions for the same group may be related to review activities carried out under the auspices of the program.

Medicaid

Originally intended to provide medical services to low-income women and children, Medicaid has evolved over time into the largest third-party financer of long-term care in the United States. Total Medicaid benefits (including both Federal and State shares) came to $44 billion in 1986, of which $16 billion were for nursing home care.

Counts of recipients demonstrate the extent to which Medicaid has become a long-term care vehicle. In fiscal year 1985, 21.8 million people received program benefits. Of that number, 2.5 percent received skilled nursing facility (SNF) care, and 3.8 percent received intermediate care facility (ICF) services (excluding ICF services for the mentally retarded). Yet, of fiscal year 1985 vendor payments, 13.5 percent were for SNF care and 17.4 percent were for ICF services. Nursing home recipients received an average of $9,300 in skilled nursing care and $7,900 in intermediate care in that year (Health Care Financing Administration, 1986).

Private health insurance

As has been the case in recent years, growth in private health insurance was more rapid among self-insured policies than among the traditional carriers—the Blues and commercial carriers. Taken together, health insurance benefits rose 7.7 percent in 1985 (the most recent year with reasonably complete data), to a total of $113 billion.

For insurers, 1985 was a profitable year, but less so than 1984. The difference between premiums and losses grew 3.2 percent from 1984 to 1985. Administrative expenses grew 13.9 percent, reducing the net underwriting gain experienced in 1984. The size of that gain varied across insurance types: Traditional group and individual policies generated net underwriting losses, while minimum-premium plans, the Blues, and self-insured plans booked net underwriting gains (Table 21). Preliminary and projected data for 1986 indicate net underwriting losses for the industry, caused by very low growth in premiums (low by historical standards). Early 1987 data indicate that the situation will change dramatically: Some health policies are experiencing 20-to 30-percent increases in premium rates.

Direct patient payments

In 1986, $116 billion was spent for health care that was not covered by a third party. For the most part, this money came from patients or their families directly. Unlike total spending, less than one-third of direct patient payments were for institutional (hospital or nursing home) care. The largest amounts of direct payments were for physician services and drugs and sundries. Direct spending for nursing home care was only the third largest component.

During the last 4 years, the steadily downward trend in the share of personal health care expenditures paid directly by consumers has begun to waver. Part of this is attributable to changes in private and public health insurance copayment schedules, and part of it is because of changes in the size and nature of the uninsured population.

The method by which direct patient payments is calculated in the national health accounts precludes an easy analysis of the out-of-pocket burden of health care. Because there are no continuous surveys of out-of-pocket spending for health by the entire population, direct payments are found as a residual. That is, total spending is measured for a given service, usually from provider records, and then known third-party reimbursements are subtracted. The resulting remainder is termed “direct patient payments,” but includes (in addition to out-of-pocket spending) the net effects of estimation errors as well as nonpatient revenues. The effects of estimation error are impossible to determine; nonpatient revenues are a factor only in the case of hospital and nursing home care (Table 3). Current benchmarking efforts are being directed at “cleaning” the direct payment category, but will not bear fruit for another year.

Table 3. Net revenues for all registered hospitals as a percent of total revenues: United States, hospital financial years 1980-85.

| Source of revenue | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Percent distribution | ||||||

| Total revenue from all sources | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Net revenue from government sources | 41.3 | 40.7 | 40.4 | — | — | — |

| Net revenue from nongovernment sources | 42.4 | 43.0 | 43.0 | — | — | — |

| Net revenue from patients | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Operating revenue | 13.8 | 14.1 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 15.0 | 15.9 |

| Nonoperating revenue | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

SOURCE: American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, unpublished data.

Effects of demographic change

Population is often cited as an engine of demand for goods and services. Abrupt alterations in demographic structure—usually caused in modern times by rapid fertility changes—can create new needs or eliminate old ones. Because many industries require several years to adjust to demand changes, population shifts can result in dislocation of production.

The educational system, as a case in point, has already had to cope with the effects of the roller coaster birth rates since World War II. Demand for teachers rises and falls with the size of the school-age population. Yet the response to teacher shortages takes time, because it takes several years to train teachers (and even more to train the teachers of teachers). For the same reason, reaction to teacher surpluses is delayed by the number of teachers-in-training “in the pipeline.” Consequently, elementary and secondary school systems, and then colleges and universities, often find themselves with excesses or shortages of personnel and other forms of educational capital stock.

So far, the effects of recent demographic changes have only modestly influenced the health care industry. Hospitals and obstetricians have seen demand wax and wane for fertility-related services. Recently, the echo of the postwar baby boom is being felt again in maternity wards.

But the biggest impacts are expected to occur in the next century because health care use rises rapidly after about age 65. The aged population is expected to continue growing rapidly until the mid-1990's. Then a temporary slowing will set in as the small birth cohort of the 1930's depression turns 65 years of age. By 2010 the postwar baby boom will reach retirement age and the rapid growth of the aged population will resume until the peak year birth cohort (about 1970) reaches age 65 in 2035.

The age distribution is also affected by changing mortality patterns. Because mortality change is usually spread over a wider age band than is change in fertility, the effect tends to be more gradual. There are exceptions to this, of course. War losses among young men drastically changed the French demographic structure after World War I and the Soviet population after World War II. Famine and certain diseases are quite age specific also. Most projections of U.S. mortality, however, are for gradual improvement, which reinforces the aging of the population in the next century.

If these age shifts occur as predicted, they may have profound effects on the demand for medical services and on the ability of society to pay for those services. The distribution of health care spending by age is reasonably well known, but the financing of spending by age has received much less attention. The rapid growth of the aged population in the next century may not be matched by growth in the working age population unless birth rates rebound. This would then limit the tax base that supports some medical care for the aged. But other financing is provided by the individual patient through insurance or direct payments. Some financing is provided through employer premiums and corporate taxes, which are undoubtedly borne by various sectors of the population in the form of reduced wages, higher prices for consumer goods, and so on.

Generally, aging of the population has not been a major factor in determining medical care costs in the past. Factors other than population have dominated in the past few decades and may continue to do so for the next few decades as well. Reference was made earlier to the willingness of society to devote an ever-increasing share of national income to health care. Some payers—corporate and government—are now resisting this unbridled growth. Demographic factors may well be a catalytic factor in future willingness to pay for improved health care, because they will influence the aggregate cost of providing current standards of care to all.

One way to visualize the effects of age shifts on health care spending is to recalculate the cost of health care in the current year as if the age-sex composition of the population were as it was several decades ago or as it is projected to be several decades in the future (Table 4). This approach freezes prices, technology, and population size. In 1986, spending for care in hospitals was $180 billion, or about $720 per person. If the younger population mix of 1946 had been in place in 1986, spending would have been only about $631 per person or a total of $157 billion. The difference is small because the effects of aging in that period were small. On the other hand, if the age-sex mix of 2026 were imposed on the 1986 hospital system, it would generate spending of about $231 billion, or $926 per person, to deliver the same age/sex-specific quantity and quality of services. For other services, the effects of aging are more or less dramatic, depending on the nature of the service. Table 4 also shows, for example, that the cost of nursing home care would have been cut nearly in half if the 1946 age composition had applied, or increased by about 70 percent if the 2026 age and sex structure were in place. In this case, past growth looks more dramatic than the future, because nursing home services are concentrated in the group age 85 or over. The peak of the baby boom in 1970 will not reach age 85 until 2055.

Table 4. Hypothetical 1986 expenditures under the age and sex structure of selected calendar years.

| Type of expenditure | Calendar year from which age and sex structure is drawn | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1946 | 1966 | 1986 | 2006 | 2026 | |

|

| |||||

| Amount in billions | |||||

| Total personal health | $356.7 | $365.6 | $404.0 | $449.8 | $508.2 |

| Hospital | 157.3 | 161.6 | 179.6 | 200.0 | 230.9 |

| Physician | 88.9 | 87.3 | 92.0 | 96.6 | 105.6 |

| Nursing home | 20.9 | 26.8 | 38.1 | 52.4 | 64.8 |

| All other | 89.6 | 89.9 | 94.3 | 100.8 | 106.9 |

NOTES: Figures in this table combine the age and sex composition of selected calendar year populations with 1986 prices and patterns of health care use. Calendar year 1986 spending figures are shown to establish a reference point.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

In Table 5, we show how the demographic mix of the population would change the distribution of spending by age from that reported by Fisher for 1978 (Fisher, 1980). Because the median age of the population is expected to increase over time, the portion of total costs for those 65 years of age or over will increase for most services, while the portion for both children and adults under age 65 will decline, all other things held constant. The change in age distribution of spending also will affect who pays for the services, provided that financing channels remain as they are today. Data presented in Table 6 show that for major acute care services, the Medicare share of total spending would increase and the insurance share would decrease over the next several decades. These changes would occur because Medicare spending is concentrated on the aged and because there is less private insurance coverage of hospital and physician services for the aged than for the rest of the population.

Table 5. Hypothetical distribution of total spending among three age groups under the age and sex structure of selected calendar years.

| Type of expenditure and age | Calendar year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1978 | 2000 | 2020 | 2040 | |

| Median age of population | 29 | 36 | 39 | 41 |

| Percent distribution | ||||

| Hospital | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Under 19 years | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| 19-64 years | 63 | 61 | 56 | 45 |

| 65 years or over | 28 | 32 | 38 | 50 |

| Physician | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Under 19 years | 15 | 12 | 10 | 10 |

| 19-64 years | 60 | 62 | 59 | 54 |

| 65 years or over | 25 | 26 | 31 | 36 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 6. Hypothetical distribution of spending among sources of funds under the age and sex structure of selected calendar years.

| Type of expenditure | Calendar year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1986 | 2000 | 2020 | 2040 | |

|

| ||||

| Percent distribution | ||||

| Hospital | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Direct | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Insurance | 36 | 35 | 33 | 28 |

| Medicare | 29 | 30 | 34 | 39 |

| Medicaid | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Other | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Physician | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Direct | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 |

| Insurance | 42 | 42 | 40 | 38 |

| Medicare | 21 | 21 | 26 | 30 |

| Medicaid | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

NOTES: Figures in this table combine the age and sex composition of selected calendar years with 1986 age/sex-specific sources of funds. Calendar year 1986 is shown to establish a reference point.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Although demographic change is an important factor in the determination of health expenditures, it is by no means the most important factor. Nor does the projected demographic change of the population necessarily mean that the United States will inevitably have an increasing share of the GNP devoted to health spending. To demonstrate these proposals, consider expenditures for inpatient hospital care (Table 7). Similar analyses have been conducted for physician services and nursing home care (Tables 8 and 9).

Table 7. Factors contributing to percent change of inpatient hospital expenditures as a share of gross national product (GNP): Selected years 1965-2040.

| Year | Inpatient hospital expenditures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Percent of GNP | Average annual percent change in percent of GNP | Change in factors related to demographic mix | Change in factors other than demographic mix | Change in real GNP per capita | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Deflated price | ||||

| Percent change | ||||||||

| 1965 | 1.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1970 | 1.8 | 8.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 6.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 1975 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| 1980 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| 1985 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | −0.1 | −5.0 | 8.0 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| 1990 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | −0.1 | −1.5 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| 1995 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| 2000 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 | −0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Projected percent change based on demographics only | ||||||||

| 2005 | 3.4 | −1.0 | 0.7 | −0.1 | — | — | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 3.3 | −0.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | — | — | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 3.2 | −0.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | — | — | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 3.2 | −0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 3.2 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 3.1 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.2 | — | — | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 2.9 | −1.0 | 0.7 | −0.3 | — | — | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 2.7 | −1.4 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 1.6 | |||

| Projected percent change allowing intensity to grow at rate of the GNP | ||||||||

| 2005 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | −0.1 | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | — | 1.3 | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.1 | — | 1.2 | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.1 | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | −0.2 | — | 1.4 | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | −0.3 | — | 1.5 | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.2 | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

NOTE: Change in expenditures as a percent of GNP equals the combined changes in demographic and nondemographic factors minus the change in real GNP per capita.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 8. Factors contributing to percent change in physician services expenditures as a share of gross national product (GNP): Selected years 1965-2040.

| Year | Physician services expenditures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Percent of GNP | Average annual percent change in percent of GNP | Change in factors related to demographic mix | Change in factors other than demographic mix | Change in real GNP per capita | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Deflated price | ||||

| Percent change | ||||||||

| 1965 | 1.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1970 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| 1975 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 0.2 | −0.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 | −0.2 | 1.3 |

| 1980 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.3 | −0.0 | −0.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| 1985 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

| 1990 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 0.2 | −0.0 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| 1995 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| 2000 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| Projected percent change based on demographics only | ||||||||

| 2005 | 2.9 | −1.3 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | — | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 2.8 | −1.0 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | — | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 2.7 | −0.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | — | — | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 2.6 | −0.7 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 2.5 | −0.8 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 2.4 | −1.1 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | — | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 2.2 | −1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | — | — | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 2.0 | −1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | — | — | — | 1.6 |

| Projected percent change allowing intensity to grow at rate of the GNP | ||||||||

| 2005 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | 1.3 | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | — | 1.2 | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | −0.0 | — | 1.4 | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | — | 1.5 | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

NOTE: Change in expenditures as a percent of GNP equals the combined changes in demographic and nondemographic factors minus the change in real GNP per capita.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 9. Factors contributing to percent change in nursing home care expenditures as a share of gross national product (GNP): Selected years 1965-2040.

| Year | Nursing home care expenditures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Percent of GNP | Average annual percent change in percent of GNP | Change in factors related to demographic mix | Change in factors other than demographic mix | Change in real GNP per capita | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Utilization per day | Intensity per day | Deflated price | ||||

| Percent increase | ||||||||

| 1965 | 0.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1970 | 0.5 | 9.5 | 2.2 | — | 6.9 | −0.6 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| 1975 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 2.0 | — | 3.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| 1980 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 1.8 | — | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.5 |

| 1985 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 1.8 | — | −0.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| 1990 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 2.0 | — | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| 1995 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 2.0 | — | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| 2000 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | — | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Projected percent change base d on demographics only | ||||||||

| 2005 | 1.2 | −0.2 | 1.3 | — | — | — | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 1.1 | −0.3 | 1.0 | — | — | — | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 1.1 | −0.5 | 0.7 | — | — | — | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 1.1 | −0.2 | 0.9 | — | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | — | — | — | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 2.4 | — | — | — | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 2.5 | — | — | — | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.9 | — | — | — | — | 1.6 |

| Projected percent change allowing intensity to grow at rate of the GNP | ||||||||

| 2005 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | — | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

| 2010 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | — | — | 1.3 | — | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | — | — | 1.2 | — | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | — | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2025 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | — | — | 1.1 | — | 1.1 |

| 2030 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 | — | — | 1.4 | — | 1.4 |

| 2035 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | — | — | 1.5 | — | 1.5 |

| 2040 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | — | — | 1.6 | — | 1.6 |

NOTE: Change in expenditures as a percent of GNP equals the combined changes in demographic and nondemographic factors minus the change in real GNP per capita.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Historically, the age and sex compositions of the population have contributed relatively little to growth of inpatient hospital care as a percent of GNP. The largest contribution (5.7 percent per year from 1965 to 1985) was from “intensity” of care—real goods and services provided per inpatient day. The second largest contribution to annual growth, 1.1 percent per year, was by hospital price inflation over and above general price inflation. Changes in the age and sex mix of the population, in contrast, added only 0.6 percent per year to expenditure growth.

At the same time that spending for inpatient care was growing, so was GNP—the resource base from which that spending was financed. In the historical period, hospital spending outpaced GNP growth by some 4.5 percent per year. Consequently, inpatient hospital expenditures rose as a share of the GNP, reaching 3.0 percent in 1985.

Will that trend continue? To answer this question, we constructed two scenarios. In the first, hospital spending through the year 2000 was as described later in this article. After the turn of the century, however, it grew only as fast as dictated by demographic change. In this scenario, GNP growth projected by the Social Security Board of Trustees (Social Security Administration, 1987) was more than adequate to accommodate the required change in spending; hospital expenditures as a percent of the GNP actually fell back to near its 1980 level by the year 2040. However, this first scenario is very generous in its assumption that no factor other than demographics will affect the growth of spending.

A second scenario was developed to reflect some of these other factors. In this scenario after the year 2000, intensity per day was allowed to grow at the same rate as the real per capita GNP (although the results would have been the same had any other factor or combination of factors been allowed to grow by that amount). Here, hospital spending continues to rise as a share of the GNP, but much more slowly than during the historical period.

However, even the second scenario is generous. It presumes that nondemographic factors will grow at the same rate as the real per capita GNP in the future. In the past, however, those factors have grown 4 percent faster than real GNP.

Similar results obtain when physician and nursing home care are examined (Tables 8 and 9). Even in the latter case, in which aging of the population is expected to play a significant role, real GNP growth is projected to nearly offset the rise in spending. Clearly, if health expenditures rise as a share of the GNP, it will be as a result of factors other than demographics.

Projections to the year 2000

Based on historical trends and relationships and on recent experience, we project that national health expenditures will reach $1.5 trillion by the year 2000, 15.0 percent of the gross national product (Tables 12—19). Total spending per capita will rise from $1,837 in 1986 to $5,550 in 2000.

Table 19. Other personal health care expenditures1 aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1980-2000.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private Health insurance | Other Private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | Medicare2 | Medicaid3 | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1980 | $50.9 | $32.0 | $18.8 | $8.6 | $1.5 | $8.7 | $5.7 | $3.0 | $1.5 | $3.4 |

| 1985 | 86.4 | 50.3 | 36.0 | 16.8 | 2.4 | 16.9 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 6.8 |

| 1986 | 94.4 | 53.7 | 40.7 | 19.0 | 2.5 | 19.1 | 13.1 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 8.0 |

| 1987 | 103.3 | 58.1 | 45.2 | 21.2 | 2.8 | 21.2 | 14.7 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 9.0 |

| 1990 | 136.0 | 74.2 | 61.7 | 28.7 | 3.7 | 29.3 | 20.3 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 12.9 |

| 1995 | 213.2 | 112.1 | 101.1 | 45.6 | 6.4 | 49.1 | 34.1 | 15.0 | 12.7 | 22.8 |

| 2000 | 328.5 | 167.5 | 161.1 | 70.7 | 10.7 | 79.8 | 54.8 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 40.0 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1980 | $216 | $136 | $80 | $37 | $6 | $37 | $24 | $13 | (4) | (4) |

| 1985 | 350 | 204 | 146 | 68 | 10 | 68 | 47 | 22 | (4) | (4) |

| 1986 | 378 | 215 | 163 | 76 | 10 | 77 | 53 | 24 | (4) | (4) |

| 1987 | 410 | 231 | 179 | 84 | 11 | 84 | 58 | 26 | (4) | (4) |

| 1990 | 527 | 288 | 239 | 111 | 15 | 114 | 79 | 35 | (4) | (4) |

| 1995 | 798 | 420 | 378 | 171 | 24 | 184 | 128 | 56 | (4) | (4) |

| 2000 | 1,193 | 608 | 585 | 256 | 39 | 289 | 199 | 91 | (4) | (4) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1980 | 100.0 | 63.0 | 37.0 | 17.0 | 2.9 | 17.2 | 11.2 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 6.7 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 58.3 | 41.7 | 19.4 | 2.7 | 19.6 | 13.4 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 7.9 |

| 1986 | 100.0 | 56.9 | 43.1 | 20.2 | 2.7 | 20.3 | 13.9 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 8.5 |

| 1987 | 100.0 | 56.3 | 43.7 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 20.5 | 14.2 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 8.7 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 54.6 | 45.4 | 21.1 | 2.7 | 21.5 | 14.9 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 9.5 |

| 1995 | 100.0 | 52.6 | 47.4 | 21.4 | 3.0 | 23.0 | 16.0 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 10.7 |

| 2000 | 100.0 | 51.0 | 49.0 | 21.5 | 3.2 | 24.3 | 16.7 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 12.2 |

Personal health care expenditures other than those for hospital care, physician services, and nursing home care.

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimates is inappropriate.

NOTE: Per capita amounts based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Assuming the continuation of current laws and regulations, we see little change in the distribution of services or of financing sources between now and the turn of the century. In fact, we project that hospital care will increase slightly as a share of total spending—cost containment notwithstanding (though we have recognized and extended the shift in composition between inpatient and outpatient care). Aging of the population will cause Medicare's share of total spending to rise a small amount as well, but the overall patterns of spending look remarkably similar over the 14-year span.

Still, growth in health spending is expected to moderate in the future. During the period 1965 through 1986, national health expenditures grew at an average annual rate of 12.1 percent. In contrast, the average growth from 1986 to 2000 is projected to be 9.0 percent. That historical growth in health spending will be more rapid than growth in our ability to pay is one factor prompting Congress, States, and private industry to initiate alternate ways to pay for health care, alternatives such as health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations, and Medicare's prospective payment system.

The future being unknowable as it is, we have tried to steer a middle course in constructing our projections. We have focused on average annual rates of change, assuming no unanticipated events. Historical patterns in health spending were evaluated, with special emphasis given to the effects of Medicare's prospective payment system and to the recent impact of private sector initiatives on expenditure patterns. The resulting scenario serves as a baseline from which alternative estimates can be constructed to meet the needs of or to satisfy differing views of the reader.

Projection methodology and assumptions

The projection model used in this article builds on the underlying sources of demand and supply to project spending for various goods and services. Consumption growth is divided into several factors:

The effect of the demographic composition of the population (age and sex) on use per capita and on intensity of service per contact.

Use per capita and intensity of service exclusive of age and sex effects.

Population growth.

Price growth in the general economy.

Price changes for the goods or services over and above those in the general economy.

The future of some of these factors is determined by exogenous assumptions, as explained later. The other factors are projected by using a combination of actuarial, economic, statistical, demographic, and judgmental processes. Projections of supply factors such as hospital beds and physician counts are incorporated to capture changes in the balance between demand and supply and to generate internally consistent projections.

Central to the model are assumptions concerning growth of Medicare expenditures. Our model is built around the relationships between Medicare and the various health care markets. We have incorporated projections of Medicare expenditures made by the two Medicare boards of trustees (Health Care Financing Administration, 1987a, b) as assumptions in our model.

In addition to examining the relationships between Medicare and the general health care sector, we model the relationships between the health sector and the general economy. Our assumptions for the general economy and for population are taken from the Social Security Trustees' alternative II-B assumptions concerning the future (Table 10). The Trustees' forecasts assume that current regulations and policies will continue into the future. In this sense, our projections are based on “current law” assumptions. Additional assumptions, concerning counts of health personnel, physicians, and dentists have been taken from projections made by the Bureau of Health Professions (Table 11).

Table 10. Historical estimates and projections of gross national product, inflation, and population: Selected calendar years 1950-2000.

| Calendar year | Gross national product | Total population in thousands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Current dollars in billions | 1982 dollars in billions | Implicit price deflator | ||

| Historical | ||||

| 1950 | $288 | $1,204 | 23.9 | 159,386 |

| 1955 | 406 | 1,495 | 27.2 | 175,439 |

| 1960 | 515 | 1,665 | 30.9 | 190,081 |

| 1965 | 705 | 2,088 | 33.8 | 204,056 |

| 1970 | 1,015 | 2,416 | 42.0 | 214,895 |

| 1975 | 1,598 | 2,695 | 59.3 | 224,720 |

| 1980 | 2,732 | 3,187 | 85.7 | 235,305 |

| 1981 | 3,053 | 3,249 | 94.0 | 237,785 |

| 1982 | 3,166 | 3,166 | 100.0 | 240,259 |

| 1983 | 3,406 | 3,279 | 103.8 | 242,647 |

| 1984 | 3,765 | 3,490 | 107.9 | 244,918 |

| 1985 | 3,998 | 3,585 | 111.5 | 247,170 |

| 1986 | 4,206 | 3,675 | 114.5 | 249,459 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1987 | 4,433 | 3,762 | 117.8 | 251,639 |

| 1990 | 5,414 | 4,107 | 131.8 | 257,769 |

| 1995 | 7,467 | 4,643 | 160.8 | 267,175 |

| 2000 | 10,164 | 5,195 | 195.7 | 275,493 |

| Average annual percent change | ||||

| Historical | ||||

| 1970-86 | 9.3 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 0.9 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1986-90 | 6.5 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.8 |

| 1990-2000 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 0.7 |

| 1986-2000 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 0.7 |

SOURCE: (Social Security Administration, 1987.)

Table 11. Historical estimates and projections of the number of active physicians and dentists as of December 31: Selected years 1950-2000.

| Year | Number of active physicians | Dentists | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total | Medical doctors | Doctors of osteopathy | ||

| Historical | ||||

| 1950 | 219,900 | 209,000 | 10,900 | 79,190 |

| 1955 | 240,200 | 228,600 | 11,600 | 84,370 |

| 1960 | 259,500 | 247,300 | 12,200 | 90,120 |

| 1965 | 288,700 | 277,600 | 11,100 | 95,990 |

| 1970 | 326,200 | 314,200 | 12,000 | 102,220 |

| 1975 | 384,400 | 370,400 | 14,000 | 112,000 |

| 1978 | 424,000 | 408,300 | 15,700 | 120,620 |

| 1980 | 457,500 | 440,400 | 17,100 | 126,240 |

| 1981 | 466,700 | 448,700 | 18,000 | 129,180 |

| 1982 | 483,700 | 465,000 | 18,700 | 132,010 |

| 1983 | 501,200 | 481,500 | 19,700 | 135,120 |

| 1984 | 506,500 | 485,700 | 20,800 | 137,950 |

| 1985 | 520,700 | 498,800 | 21,900 | 140,770 |

| 1986 | 534,800 | 511,600 | 23,200 | 143,230 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1987 | 548,500 | 524,100 | 24,400 | 145,450 |

| 1988 | 562,000 | 536,300 | 25,700 | 147,410 |

| 1990 | 587,700 | 559,500 | 28,200 | 150,760 |

| 1995 | 645,500 | 611,100 | 34,400 | 156,800 |

| 2000 | 696,500 | 656,100 | 40,400 | 161,180 |

| Average annual percent change | ||||

| Historical | ||||

| 1970-86 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 2.1 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1986-90 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 1.3 |

| 1990-2000 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 0.7 |

| 1986-2000 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 0.8 |

SOURCE: Bureau of Health Professions: Fifth Report to the President and Congress on the Status of Health Personnel in the United States. DHHS Publication No. HRS-P-0D-86-1, HRP-0906767. Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office. Mar. 1986.

More generally, the projections are predicated on the assumption that the competitive structure, conduct, and performance of the health delivery system will continue to evolve along patterns observed from recent historical experience. This in turn implies that the use of medical care, including intensity of services per case, will grow in accordance with historical trends and relationships. Health care prices are assumed to vary with the implicit price deflator for the GNP in accordance with historical trends. Modifications have been made in longrun trends to reflect recent changes in reimbursement incentives by both the public and private sectors.

Because they are based on current law, these projections do not account for any alternative scenarios, however likely. For example, no provision can be made for the possibility of a federally mandated cost containment program such as prospective payment by all payers. Nor has any allowance been made for any major new, publicly financed program of medical care such as a catastrophic health insurance program or a comprehensive national health insurance program. Neither do we account for any technological breakthrough in the treatment of acute and chronic illnesses that would significantly alter the evolving patterns of morbidity and mortality.2

Specific assumptions

The economy

The outlook for the economy from 1986 to 1990 is for inflation rates (measured by the GNP implicit price deflator) to drift upward, reaching 4.2 percent per year by 1990 and averaging 3.6 percent per year during the period. As a reference point, the GNP deflator increased 2.6 percent in 1986, the latest year of historical experience. Real (constant-dollar or inflation-adjusted) GNP is expected to increase an average 2.8 percent annually from 1986 to 1990. Combining the growth of real GNP and of prices, nominal GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 6.5 percent. In the longer term years (1990-2000), the GNP deflator is predicted to increase at an average annual rate of 4.0 percent and real GNP at a 2.4-percent rate.

During the period covered in this projection, inflation will play a smaller role in driving health care expenditures than it has played in the recent past. For the entire projection period (1986-2000), the GNP deflator is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent. This is a deceleration from the last decade (1976-86), when the GNP deflator increased at an average annual rate of 6.1 percent. The deceleration in the economy-wide inflation has an impact on health care spending because approximately 60 percent of the growth in this spending can be accounted for by changes in the general inflation rate.

Demographic change

Growth and change of the population is another factor accounting for growth in the level of health care spending. The U.S. population is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 0.7 percent from 1986 to 2000, somewhat slower than the 0.9 percent rate from 1970 to 1986. However, beyond the effects of population growth itself, health care expenditure growth is affected by shifts in the age composition of the population. The effects of those shifts vary by type of service, as was demonstrated in the previous section of this article.

Health professions