Abstract

Health maintenance organizations (HMO's) are paid a capitated amount for enrolled Medicare beneficiaries that is 95 percent of what these enrollees would be expected to cost in the fee-for-service sector. However, it appears that HMO enrollees are less costly than other Medicare beneficiaries. With a simulation model, we demonstrate that with a 95-percent pricing rule, any significant degree of biased selection leads to increased cost to the payer, even when HMO's are cost effective compared with the fee-for-service sector. Optimal pricing percentages from the point of view of cost minimization are considerably less than 95 percent.

Introduction

In 1983, the Medicare program of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) paid $57.4 billion to hospitals and physicians on behalf of 30.0 million aged and disabled beneficiaries, making Medicare the largest single buyer of health services in the United States. Medicare's costs rose from $7.1 billion in 1970, a compound annual growth rate of 17.4 percent from 1970 to 1983.

In order to contain costs, Medicare is aggressively pursuing policies of prospective payment, altering incentives to providers by disassociating payment received from services rendered. In October 1983, HCFA began phasing in the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment system for hospital costs. By October 1986, HCFA was paying most hospitals a prospectively determined amount for each inpatient episode, dependent on the DRG within which a patient is classified at discharge.1 Participation in the DRG system is mandatory for all but a few classes of hospitals. (Those presently exempt are children's, psychiatric, rehabilitation, and long-term care facilities.)

In another prospective payment policy initiative, Medicare allows beneficiaries to enroll in health maintenance organizations (HMO's) that contract with HCFA. By mid-1986, more than 660,000 beneficiaries had enrolled in HMO's. As currently structured, for persons 65 years of age or over not suffering from end stage renal disease, Medicare pays to the HMO a premium equal to 95 percent of the average Part A and Part B Medicare cost per Medicare beneficiary in the county, adjusted for the enrollee's age, sex, and welfare and institutional status. This is the adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) program, and participation is voluntary for both HMO's and beneficiaries.

The AAPCC program has the potential of benefiting HCFA by allowing it to take advantage of the demonstrated ability of HMO's to reduce health costs (Manning et al., 1984; Luft, 1981). The program also has the potential of benefiting Medicare enrollees themselves by expanding their choice to include a comprehensive care provider virtually free of the deductibles, copayments, and limits associated with the regular Medicare program.

On the other hand, patterns of biased selection may prevent the new program from fulfilling its potential. Biased selection exists whenever the average cost of a group of patients differs systematically from the payments for treating those patients. Biased selection is a concern for any form of prospective payment system in which a provider bears the financial risk of treatment costs in exchange for an indemnity-like payment. In the DRG system, participation by facilities is mandatory, so the burden of biased selection falls on certain classes of facilities. HCFA has direct control over its average payment per inpatient episode and can therefore take steps to ensure that the DRG system is, from its point of view, budget neutral. By contrast, in the voluntary AAPCC program, HCFA does not directly control the overall average cost. If the more costly patients remain in the fee-for-service sector, biased selection can increase total costs to HCFA.

Private corporations have faced similar selection problems in relation to HMO's since the HMO Act of 1973 forced employers with 25 or more employees to offer enrollment in HMO's as a health benefit option. A corporation paying “community rates” to its HMO's may end up paying more for total health benefits after adding the HMO option if HMO's attract a favorable selection of low-cost enrollees. Price negotiation with HMO's will become an increasingly important part of private corporation efforts to contain health care costs.

It has been found in numerous studies that biased selection is a serious concern. In a survey by Rossiter and Wilensky (1986), it was found that essentially all of the studies done since 1973 produced evidence that HMO's attract enrollees with costs lower than (or in a few cases, equal to) costs of those remaining in the fee-for-service sector. For Medicare beneficiaries, biased selection into HMO's is particularly significant. Eggers and Prihoda (1982) found that enrollees in the Fallon Health Plans of Worcester, Massachusetts, and the Kaiser-Permanente Plan of Portland, Oregon, had average medical costs during the 4 years preceding enrollment that were 30-percent lower than those of the county control group during the same period of time. Adjustments for differences in age, sex, and welfare and institutional status (i.e., the population characteristics in the AAPCC) between the enrollee and control groups accounted for one-third of the difference in reimbursement costs between these groups for the Fallon Plan and one-quarter of the difference for the Kaiser Plan.

Earlier, Eggers (1980) conducted a study of the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Washington, the first HMO to enter a Medicare risk contract with the Federal Government. He found an even larger difference, 40 percent, between prior health care costs of enrollees and costs of individuals in the county control group. Finally, Eggers and Friedlob (1984) found that four HMO's in Minneapolis also had significant favorable selection.

The only exception to this pattern of favorable selection by HMO's was for the Greater Marshfield Community Health Plan of Marshfield, Wisconsin, an HMO organized as an independent practice association. After controlling for differences in AAPCC population characteristics, Eggers and Prihoda (1982) found no significant difference in prior medical care costs between individuals who joined the plan and those who did not. Thus, in seven of the eight HMO's to accept risk contracts for Medicare enrollees that were studied by Eggers and associates, favorable selection for the HMO has been found.

This favorable selection could result from activities of the HMO itself or from beneficiary choice. Luft (1982) discussed ways in which HMO's seek to attract preferred groups of enrollees. Berki and Ashcraft (1980), Neipp and Zeckhauser (1985), and others have pointed out that the main deterrent to HMO enrollment is an established tie to a fee-for-service physician. If high-use beneficiaries have closer ties with their physicians, HMO's will tend to attract lower cost enrollees.

If an HMO has a favorable selection of Medicare beneficiaries, the average adjusted per capita cost is an overestimate of costs to the HMO. Basing the average on those who remain in the fee-for-service (FFS) system exacerbates the discrepancy because the FFS average is increased as low-cost beneficiaries join the HMO. The problem for HCFA is to design a classification and payment system that takes advantage of the cost-effective care offered by HMO's without allowing biased selection to turn the AAPCC into a cost-increasing program for HCFA.

One strategy for reducing the detrimental impact of biased selection is to improve the AAPCC classification system. If payments were more closely tied to expected costs through improved classification, the lower cost enrollees attracted to HMO's would bring with them lower revenues. The potential of incorporating measures of prior use into the AAPCC formula has been explored by Anderson, Resnick, English, and Gertman (1982); Anderson, Resnick, and Gertman (1983); Gruenberg and Lambert (1984); and Beebe, Lubitz, and Eggers (1985). Welch (1985) has provided a useful conceptual discussion of empirical models incorporating prior use. Gruenberg and Stuart (1982) investigated disability status as a predictor of subsequent health costs. All of these researchers have demonstrated that the explanatory power of the AAPCC classification system can be noticeably improved and that some revisions of the classifications are probably warranted.

Nevertheless, the overall explanatory power of the revised classification system is likely to remain quite low, at best about 10 percent. If all the unexplained variance were uncorrelated with factors known to the enrollees or the HMO's, favorable selection for HMO's would be small. However, individuals are likely to retain special knowledge of health conditions not captured in any classification system. As a result, biased selection will continue to be the main pitfall in the AAPCC program.

We take the potential for biased selection as a starting point for our work and ask, “How should payments be set in the AAPCC to best attain its goal of cost control?” This question is relevant to HCFA as well as to any other payer contracting with an HMO or other provider bearing risk.

In the following section, we set out the assumptions of our model of cost and selection behavior. The degree of biased selection is operationalized to be used in the analysis to follow. In the next section, we apply the model, considering the implications of price-setting rules by a payer. We show that a 95-percent rule is very likely to increase total costs to the payer. We then go on to derive the optimal price, as a percent of FFS costs, that HMO's should receive from a payer. In subsequent sections, we examine the potential impact of the market structure of HMO supply on the AAPCC program and suggest alternative pricing strategies that hold promise of fulfilling a payer's cost-control objectives. In the text discussion, graphical depiction of our results is emphasized. Algebraic description of the model is contained in a technical note.

AAPCC cost and selection

Costs to the payer, social costs, and costs and revenues to HMO's in the AAPCC program are determined by the expected cost of treating patients in the fee-for-service and HMO sectors and on the distribution of patients between the two sectors. In this section, we develop a model of these factors that rests on five key assumptions. The first is that HMO's draw a favorable selection of enrollees. The second is that HMO's can serve a given group of enrollees at a lower cost than the FFS sector can. For example, in a randomized controlled trial, Manning et al. (1984) found HMO's to be 25 percent less expensive than the FFS sector, primarily through reduced inpatient use. We do not try to model the processes through which favorable selection and cost savings take place, but instead we focus on their implications. The third assumption is that the quality of care provided is the same in the FFS and HMO sectors. This assumption serves to focus attention on cost questions associated with the AAPCC program. Fourth, we assume that enrollment in HMO's is supply constrained. In other words, we assume that enrollment is determined by the number of spaces HMO's desire to fill.

Finally, we examine biased selection for the special case in which all Medicare beneficiaries fall in a single classification group, with HCFA paying a fixed payment to the HMO's for each HMO enrollee in that group. Differences in costs across classification groups are not a concern for biased selection because these difference can be reflected in the AAPCC payments. As noted before, we realize that the existing and proposed alternative classification and payment systems involve different payments for different groups of enrollees, but any such system is bound to remain imperfect. Our goal is to model the impact of the biased selection that remains even after a classification system, which partially captures differences in costs, is in place. The model is cast in terms of Medicare's AAPCC program but would be applicable to other payers contracting with HMO's as well. Our model bears important similarities to that of Feldman and Dowd (1982), who examined biased selection from the point of view of private employers. Differences and similarities between the two approaches are identified later.

Cost

In total, N beneficiaries are eligible for Medicare coverage in either HMO's or the FFS sector. Suppose that we rank beneficiaries according to the order in which they enroll in HMO's. Here, and throughout the article, we need not specify whether this order is a result of efforts by the HMO's to attract certain types of enrollees or the preferences of the enrollees themselves. Feldman and Dowd (1982) also rank people entering HMO's and assume that those most likely to enter have lower expected costs. They use a more complicated model and assume normally distributed HMO taste parameters.

It is worth highlighting that we do not assume that the first few enrollees into the HMO are necessarily the lowest cost enrollees. Some high-cost individuals may be included among the first enrollees. Despite this, available evidence suggests that the expected cost of the first enrollees is below the average of all enrollees. For this reason, we focus on the expected costs of serving patients in the HMO and FFS sectors.

Let C(n) be the expected cost of serving the nth person in the HMO sector, and let (1 +B)C(n) be the expected cost of serving the same person in the FFS sector. B is thus the relative inefficiency of the FFS sector, expressed as a fraction of HMO costs. For simplicity, we treat n as a continuous variable ranging from 0 to N, so C(0) and C(N), referred to later as Cmin and Cmax, are the expected costs of the first and last beneficiaries, respectively, to enroll in HMO's.

It is important to emphasize that C(n) is defined in terms of the expected costs of serving enrollees rather than actual costs. During any year, the distribution of actual costs for serving beneficiaries has a large variance and is highly skewed, with about one-third of the enrollees incurring no reimbursable Medicare costs at all and a large portion of the total costs being accounted for by a small portion of the people. Gruenberg and Tompkins (1984) report that annual Medicare expenditures for 1977 had a mean of $764 and standard deviation of $1,985. Thirty-six percent of people had no expenditures, and the top 5 percent of people accounted for more than one-half of all expenditures. However, actual costs in 1 year are not a perfect predictor of what could be expected for costs in subsequent years. As Welch (1985) and others have pointed out, Medicare expenditures regress toward the mean over time. Many of those incurring no cost in 1 year will incur positive costs in future years, and many with high expenditures will cost less in the future. Therefore, expected costs will be less widely distributed than actual costs in any 1 year. In particular, virtually everyone should have a positive expected cost.

Biased selection

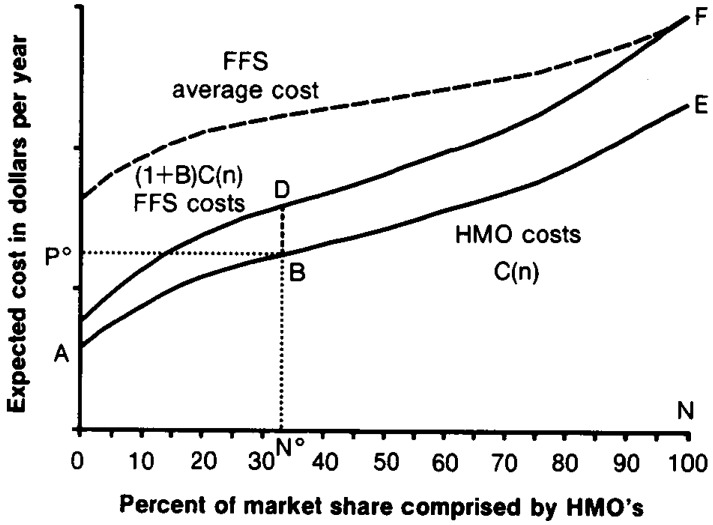

The dark solid curves in Figure 1 depict plausible relationships between the number of enrollees selecting the HMO and the expected cost per beneficiary of serving those enrollees in either the HMO or FFS sector. Because of favorable selection for the HMO's, the first enrollees may have relatively low expected costs. As more and more individuals are enrolled, however, costs increase. For the reasons discussed perviously, it is likely that the distribution of costs is skewed so that the individuals who are the last to enroll in the HMO's also have disproportionately high expected costs.

Figure 1. Health maintenance organization (HMO) and fee-for-service (FFS) expected cost curves.

The slope of the C(n) curve is an indicator of the degree of biased selection. If C(n) is perfectly flat, no biased selection takes place, and beneficiaries who are the first to join HMO's are typical of the entire group of enrollees (that is, have expected costs equal to the average for the population). If C(n) is steep, then the first to enroll in HMO's tend to be the least expensive beneficiaries.

The C(n) function shows the order in which an HMO can expect beneficiaries to enroll. For enrollment to take place, the beneficiary must select the HMO, and the HMO must be willing to accept the enrollment. The AAPCC payment is set by HCFA and does not serve to clear the market for places, which means equalizing the demand and supply for HMO enrollment. For a given price, there could be excess demand for spaces by beneficiaries or excess supply of spaces by HMO's. However, AAPCC price setting affects incentives to HMO's, and we believe that HMO's can significantly influence the number of HMO enrollees through marketing and increasing access. We have therefore assumed, as noted earlier, that enrollment is determined by the number of spaces HMO's desire to fill.

The broken line shown at the top of Figure 1 is the average cost curve for beneficiaries in the FFS sector, which increases as more and more beneficiaries enroll in HMO's. This curve will prove useful when examining the costs to HCFA of paying HMO's a price that is set as a percentage of average FFS costs.

To draw conclusions about the impact of biased selection, a specification for the expected cost function C(n) is needed. In the absence of relevant information about the properties of C(n), we examine first the case in which it is a linear function. (In their simulations, Feldman and Dowd, (1982), assume a linear tradeoff between premiums and prior-year health expenditures, rather than between enrollment and expected costs, as we have assumed.) The results we generate will be approximately true even if the C(n) function is only approximately linear. The impact of a skewed distribution of expected costs is considered later.

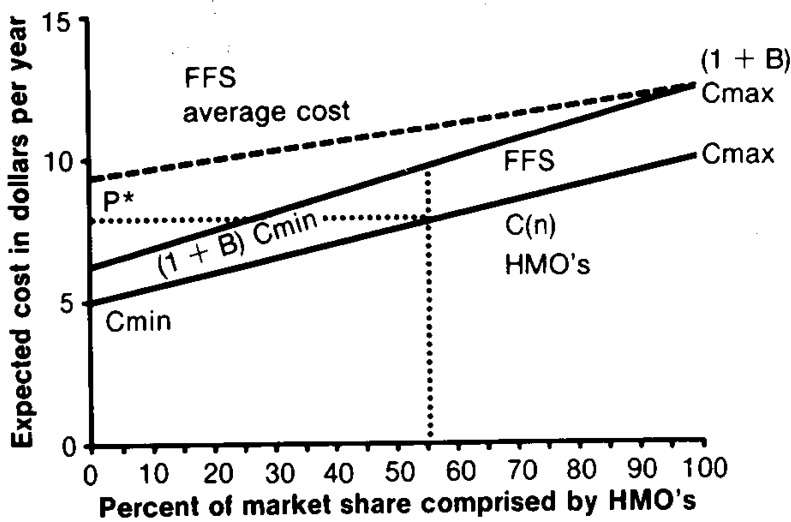

In Figure 2, we illustrate linear expected cost curves for the HMO and FFS sectors that differ by the proportionality factor (1 + B), as before. Details of the linear specification are discussed in a technical note. As in Figure 1, the broken line at the top shows the average cost of beneficiaries in the FFS sector for different sizes of the HMO sector. The upward slope of the C(n) line indicates that biased selection is occurring (i.e., that the first to join HMO's have a lower expected cost than the average).

Figure 2. Health maintenance organization (HMO) and fee-for-service (FFS) sector expected cost curves—linear case.

Price setting by payer

In this section, we first examine the cost implications of various percentage pricing rules. We show that setting the payment at 95 percent of the FFS average cost leads to losses for the payer if HMO's draw even a mildly favorable selection of patients. We next examine optimal price-setting rules and address the following questions. If the payer sets a price, what price minimizes its costs? How large should the HMO sector be? How do the price and size of the HMO sector depend on the cost distribution, on the degree of biased selection, and on the cost advantage of HMO's?

Implications of percentage pricing rules

What are the expected costs of different percentage rules? The answer to this question will quite clearly depend on the size of the HMO sector and the degree of favorable selection by HMO's. It is useful to note that even without biased selection, the maximum savings that can be achieved through enrolling people in HMO's that are paid 95 percent of the average FFS cost are only 5 percent, and this is achievable only if all persons (but one) are in the HMO sector. With only one-half of the people enrolled in the HMO sector, the maximum attainable savings are 2.5 percent, even if there is no biased selection.

Once favorable selection by HMO's becomes a possibility, pricing rules such as the 95-percent rule can increase total costs to the payer. We first examine the impact of alternative percentage pricing rules when the size of the HMO sector is given, as if the payer could determine how many people enroll in HMO's separately from the price that HMO's are offered. HMO's may still, of course, be capable of favorably attracting enrollees. Suppose that the expected cost function is linear, and consider the expected average cost curve shown as a broken line in Figure 2. The total costs for different pricing rules and for different HMO market shares can readily be calculated from information shown in the technical note.

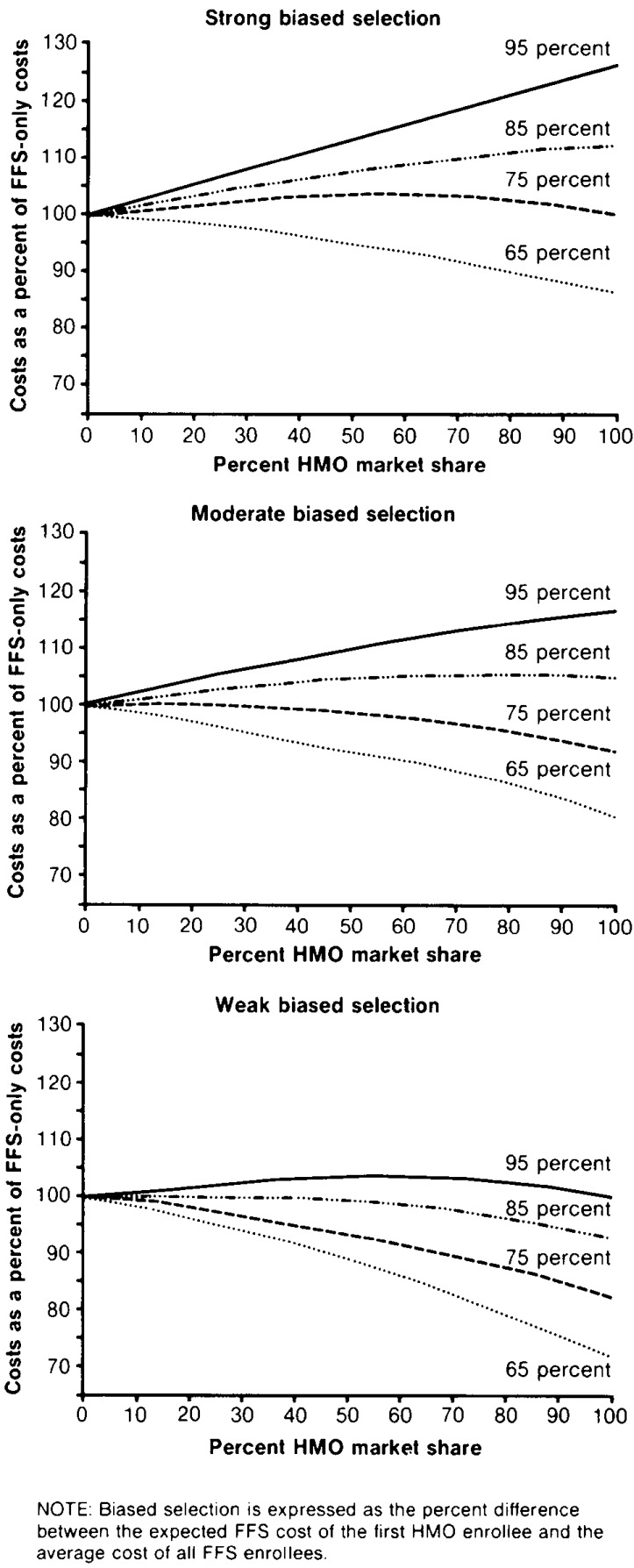

The results are shown in Figure 3 for the cases of strong, moderate, and weak biased selection. Strong biased selection is equivalent to expected costs for the first beneficiary enrolling in the HMO sector that are 33.3 percent lower than costs for the average beneficiary in the FFS sector. With moderate biased selection, expected costs for the first enrollee would be 23.1 percent lower than average, and with weak biased selection, they would be 9.1 percent lower. The key finding is that, in all three cases, using the 95-percent rule is more costly than using an FFS system only. For the case in which the HMO sector enrolls 50 percent of all beneficiaries, the excess costs range from 1.9 percent to 13.8 percent. For strong biased selection, only the 65-percent pricing rule reduces costs. Savings in this case increase as the size of the HMO sector increases.

Figure 3. Costs to Health Care Financing Administration of payment to health maintenance organizations (HMO's) for Medicare beneficiaries as a percent of fee-for-service (FFS) sector costs, by type of selection bias and HMO market share.

In constructing Figure 3, as noted earlier, we assumed that the payer can control how many beneficiaries are enrolled in HMO's but not which beneficiaries are enrolled. It is likely that the payer will not be able to induce HMO's to enroll as many people as it would like at low pricing levels. In the next section, we consider the HMO supply response to pricing policy.

HMO response to AAPCC pricing

In an earlier section, we assumed that the payer was able to determine both the number of beneficiaries enrolling in HMO's and the price. In this section, we examine the more reasonable case in which the payer can determine the price, but HMO's determine the number of people they enroll at that price. Each HMO is assumed to supply places to the point where the marginal revenue of another enrollee is just equal to the expected marginal cost. This behavior maximizes expected net revenue to the HMO.

As before, the payer is assumed to be interested in minimizing total Medicare payments for the N beneficiaries. An alternative policy goal would be to minimize the total costs of treatment, or social costs. In the model as described so far, this would be achieved if all beneficiaries joined an HMO. Payments exceed social costs because HMO profits are counted as a payment but do not represent resource use. If, however, competition for beneficiaries enforces zero profits on the HMO industry, higher marketing costs or provision of unnecessary services to attract beneficiaries will bring payments in equality with social costs. If HMO's compete by enhancing quality, an assumption that the quality of care in the two sectors is equal may no longer hold.

Total costs (TC) are the sum of HMO costs and FFS costs. HMO costs are the price, P, times the number of beneficiaries in the HMO, n. FFS costs are the actual cost of serving the beneficiaries in the FFS sector.

Total costs are shown graphically in Figure 1. By offering payment P0, a payer can induce HMO's to enroll n0 beneficiaries at a cost of P0n0. If HMO's are able to favorably select enrollees, then they are also able to capture some profits, which are represented by the approximately triangular region P0AB. Total payment to the FFS sector, including the cost inefficiency of this sector, is represented by the area n0NEFDB. Looking at Figure 1, one can see that the cost inefficiency of the FFS sector can be reduced by increasing the size of the HMO sector. However, this involves paying HMO's a greater margin of price over costs. The optimal size of the HMO sector depends on the tradeoff between profits to HMO's resulting from favorable selection and excess cost of services provided in the FFS sector. Minimizing total cost with respect to n gives the number of HMO enrollees that minimizes costs.

Optimal pricing and numerical examples

In Table 1, we present values for optimal payments and market shares for a variety of B's and degrees of biased selection. The optimal pricing formula and additional theoretical results are presented in the technical note. As shown in Table 1, if the gain in cost efficiency from using HMO's is small (5 or 10 percent), then even for a moderate degree of biased selection (i.e., where the first enrollees entering the HMO have expected costs that are 23.1 percent below the average), the optimal size of the HMO sector is less than 30 percent. If costs in the FFS sector are 20-25 percent higher than costs in HMO's, as available evidence would suggest, then a completely HMO-based reimbursement system is optimal if there is a low level of biased selection. HMO's should be encouraged to enroll more than one-half of all beneficiaries as long as the degree of biased selection remains below 50 percent.

Table 1. Optimal payment to health maintenance organizations (HMO's) as a percent of average fee-for-service (FFS) cost and resulting HMO market share, by degree of biased selection and cost inefficiency of FFS sector.

| Cost inefficiency of FFS sector1 | Degree of biased selection2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 9.1 percent | 23.1 percent | 33.3 percent | |

|

| |||

| Percent | |||

| 5 percent | |||

| HMO payment | 89.0 | 75.6 | 65.7 |

| HMO share | 26.3 | 8.8 | 5.3 |

| 10 percent | |||

| HMO payment | 87.4 | 74.5 | 64.9 |

| HMO share | 55.6 | 18.5 | 11.1 |

| 15 percent | |||

| HMO payment | 86.1 | 73.7 | 64.4 |

| HMO share | 88.0 | 29.6 | 17.6 |

| 20 percent | |||

| HMO payment | (3) | 73.1 | 64.1 |

| HMO share | 100.0 | 41.7 | 25.0 |

| 25 percent | |||

| HMO payment | (3) | 72.7 | 64.0 |

| HMO share | 100.0 | 55.6 | 33.3 |

| 30 percent | |||

| HMO payment | (3) | 72.6 | 64.1 |

| HMO share | 100.0 | 71.4 | 42.9 |

| 35 percent | |||

| HMO payment | (3) | 72.6 | 64.4 |

| HMO share | 100.0 | 89.7 | 53.8 |

Cost inefficiency of FFS sector relative to HMO sector.

Biased selection is expressed as the percent difference between the expected FFS cost of the first HMO enrollee and the average cost of all FFS enrollees.

Cannot be expressed as a percentage of FFS costs because the HMO share is 100 percent.

Feldman and Dowd (1982) also demonstrated that the optimal HMO market share ranges from 0 to 100 percent and depends on the degree of biased selection. They examined alternative employer contributions to premiums but did not examine the structure currently in place by HCFA, in which the premium is a constant proportion of the average FFS cost.

Given our specifications, the optimal price, expressed as a percentage of FFS costs, lies between 65 and 90 percent of the FFS costs. It is particularly notable that in all cases shown the optimal price to pay HMO's, expressed as a percentage of average FFS costs, is much less than the present 95-percent rule.

We believe this finding to be important. Across a range of assumptions about the costs of HMO's in relation to FFS costs and across a range of assumptions about biased selection, cost minimization requires an aggressive price formula for HMO's. For what is perhaps the most likely set of parameter values using this framework (25 percent cost-efficiency advantage and moderate biased selection), the optimal price to pay HMO's is only 73 percent of the average FFS cost. With moderate biased selection, the person least likely to join an HMO has expected costs 60-percent higher than the person most likely to join. Expressed another way, given an HMO relative efficiency of 25 percent, the first enrollee in the HMO with a moderate degree of biased selection would have costs that are about 23-percent lower than the FFS average. This difference is in accord with existing research on biased selection in HMO's. It seems very likely that a payer would benefit by lowering the price paid to HMO's below 95 percent of the AAPCC.

Note that in spite of the lower payments shown in Table 1, the HMO shares are larger than at present. This is to be expected because the choice of joining an HMO has only recently been offered to Medicare beneficiaries. Our model is of a steady state in which HMO's have filled all the places they desire to fill at the existing AAPCC price. Our model predicts that, in response to AAPCC optimal prices, the HMO market share would eventually approximate the values shown in Table 1. Although the present provides a weak test of the predictions in Table 1, early indications are that the AAPCC program is growing in popularity with HMO's, as our model would predict.

A lower AAPCC price would certainly not encourage growth of the program. According to our analysis, however, if HMO's are about 20 percent less costly than the FFS sector, HCFA has considerable ability to lower the AAPCC price and still make the program attractive to HMO's.

Skewed distribution of expected costs

As noted earlier, the linear form for C(n) probably underestimates the expected cost of serving the people who are the least likely to enroll in the HMO sector. In this section, we briefly consider the effect of a highly skewed distribution of health costs on the optimal pricing rule. Suppose that the model that previously applied to the entire group of N beneficiaries is now applied to only 95 percent of that group, the beneficiaries who are the first to enroll in the HMO's. The 5 percent least likely to enroll are those with the highest expected costs. We examined circumstances in which these high-cost cases accounted for 10-50 percent of total costs.

It is interesting to note that the number of people to enroll in an HMO in response to optimal pricing is not really affected by the concentration of costs among a few beneficiaries because the number enrolling is determined by the costs of those first entering the HMO, not the last. However, the average cost of serving the FFS beneficiaries is increased by this concentration of costs in the upper tail. Hence, the price paid to HMO's as a percentage of the average cost in the FFS sector is substantially affected by the skewed cost distribution. When costs are disproportionately accounted for by a few beneficiaries unlikely to join HMO's, the payer should adopt a pricing rule that pays HMO's a relatively smaller share of FFS costs.

In our simulations, if the degree of biased selection is 60 percent (for the 95 percent of the beneficiaries not in the high-cost category) and the HMO cost advantage is 25 percent, the optimal price to set as a percentage of FFS costs ranges from 67 percent when high-cost cases are 10 percent of total costs to only 24 percent when high-cost cases are 50 percent of total costs. Similar results for other degrees of biased selection and HMO relative efficiency suggest that a payer should price quite aggressively when expected costs are highly skewed.

Entry and dissipation of profits

In the model as shown thus far, HMO's have the opportunity of making profits at any given AAPCC price. We would expect competitive forces to reduce these profits over time. One way in which competition might occur is in the form of entry of HMO's into the AAPCC program. This should happen only if entry barriers are low. If there are fixed costs to an HMO associated with serving a Medicare population, new entry will tend to distribute beneficiaries among more and more HMO's, raising industry average cost.

Competition could also take the form of aggressive marketing by HMO's to potential low-cost enrollees. If all HMO profits are eroded by promotional expenditures, then payer costs are also social costs, and the problem of minimizing payer costs becomes identical to that of minimizing social costs.

One last way in which competition among HMO's may take place is in the form of quality or service competition. In response to changes in the AAPCC prices, HMO's may try to offer new or higher quality service features or reduce private premiums, strategies designed to attract low-cost enrollees. In the process, the expected cost of serving enrollees will increase. Unlike the previous two types of competition, for which minimizing costs of a fixed set of services was an appropriate objective of the payer, here the value of services provided will also change. This would require a more complex model structure.

An important feature of the three forms of competition described here is that in all cases HMO's will not compete for potential high-cost enrollees. They continue to have incentives to attract only beneficiaries with expected costs that are less than the AAPCC payment. Therefore, competition appears unlikely to reduce the problem of favorable selection.

We have assumed thus far that HMO's can select among enrollees on the basis of individual rather than group attributes. Relaxing this assumption probably weakens but does not eliminate the potential for favorable selection for HMO's. Even if HMO's are legally forbidden to refuse enrollment to enrollees with high expected health costs, subtle ways of discouraging the high-cost enrollees remain. HMO's could locate facilities in the suburbs or away from public transport and focus promotional efforts on recent retirees or on other groups of people who might have favorable AAPCC prices relative to expected costs. Thus, HMO's could still face an upward sloping expected cost function, so that favorable enrollment patterns would result in HMO profits. We believe that our model provides insights even under the existing legal restrictions on favorable selection by HMO's.

Conclusions

Summary

In this article we have developed a simple model of the relationship among biased selection, AAPCC pricing, HMO supply, and cost of the AAPCC program. As we anticipated, cost to the payer is very sensitive to the degree of biased selection. Even when HMO's are considerably more efficient in production that the FFS sector, biased selection can prevent a payer from participation in those savings. These findings have relevance for HCFA and other payers, including private corporations, that contract with HMO's for health care services. Our main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

The present system of setting the AAPCC price at 95 percent of the FFS average cost almost certainly increases costs to the payer. A small amount of biased selection, well within the range of current research evidence, is enough to increase total costs.

If the AAPCC price is to be set as a percentage of FFS costs, that percentage should be tied to the expected cost advantage of HMO's. Thus, if HMO's are thought to be 25 percent less costly than the FFS sector, the AAPCC price should be no more than 75 percent of the FFS cost.

For wide ranges of biased selection and HMO relative efficiency, the optimal price is from 70 to 80 percent of FFS sector costs. This optimal price falls when there are a few high-cost beneficiaries who are least likely to join the HMO.

Directions for research and policy

It is critical for HCFA to consider alternatives to the current 95-percent pricing rule in the AAPCC program. Although enrollment in HMO's is clearly being encouraged, our analysis strongly suggests that this is being accomplished at a higher total cost for the Medicare program.

AAPCC pricing has the goal of encouraging HMO enrollment by Medicare beneficiaries and at the same time minimizing the potential for biased selection to increase total costs to HCFA. To accomplish this, HCFA should seek a price-setting formula by which HMO's are paid a higher amount than the anticipated cost of serving that person in HMO's (to encourage supply) but no more than is necessary to encourage supply (to return the cost savings to HCFA rather than generating HMO profits).

Improvements in the classification of beneficiaries according to their likely costs is one direction for improvement that should be vigorously pursued. Limitations of these classification systems will, nonetheless, leave room for biased selection to interfere with the cost-containment objectives of the AAPCC.

Payment system reform should accompany improvements in classification. One general strategy for payment reform would be to partly relate payment to cost of services received by beneficiaries. The prospective component of the AAPCC payment could be reduced, and some payment to the HMO could depend on measures of service use: visits, admissions, or inpatient days. Such a system could be quite simple. For example, if the payment per additional hospital day were set at a moderate level, such as $150 per day, incentives to conserve on hospital care would remain, risk to the HMO would be reduced, and HCFA would have a mechanism to pay less for less costly beneficiaries. In a more sophisticated reimbursement system, the cost-related payment would be tied to specific procedures or diagnoses according to a fee schedule.

Partly tying payments to services actually provided would moderate incentives for HMO's to reduce health care costs and require HMO's to maintain payer-level information on utilization. Moderation of the cost-reduction incentives in a prospective payment system may be appropriate, especially in the case of the elderly (Ellis and McGuire, 1986). Improved HMO accountability to payers appears inevitable, and use of some of this information for payment purposes would probably present no additional administrative burden on the payer. A reinsurance system, by which a payer would share the cost burden with the HMO if an average cost per beneficiary were exceeded during a year, is another way to accomplish the same goal.

One final strategy for the payer would be to contract with a single HMO in a market area. Terms of payment could be negotiable, and considerations of the implications of biased selection for costs to the HMO could be dealt with directly. Competitive promotional expenditures would also be avoided. Limitations on beneficiary choice would be undesirable, however, and locking beneficiaries into a single organization might eliminate constructive competitive pressure.

Technical note

This technical note derives results for the linear expected cost formulation that is used extensively in the main text.

Letting Cmin and Cmax be the minimum and maximum expected costs, respectively, for the HMO sector, the expected cost function for this sector can be written as

| (1) |

where δ is defined as the difference between Cmin and Cmax relative to Cmin. The parameter δ is a useful measure of the degree of biased selection. In this article, we examine three cases corresponding to weak, moderate, and strong degrees of biased selection, which correspond to values of δ of 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. These values are equivalent to the first beneficiary enrolling in the HMO sector having expected costs that are 9.1, 23.1, and 33.3 percent lower than the average-cost beneficiary in the FFS sector, starting at the point where everyone is in the FFS sector. It appears to us that these values are reasonable for use in bracketing the likely range of biased selection possible under the AAPCC pricing system.

Let γ be the percent of average FFS costs (ACFFS) paid to HMO's. Total costs to HCFA can be written as

For Figure 3, this total cost is then expressed as a percentage of the total costs that would be incurred if there were no HMO sector (i.e., of

Letting P be the AAPCC price, HMO's will enroll beneficiaries up to the point at which

| (2) |

Because the function C(n) is the industry marginal cost function, it is also the supply function when the industry is made up of price takers.

The mathematical expression for total costs to the payer is:

| (3) |

From the payer's perspective, the objective is to choose the price, P*, that will induce the cost minimizing HMO enrollment, n*. Because the relationship between P and n is characterized by (2), an equivalent approach is to solve for the optimal n*, which implicitly defines P*.

Substituting C(n) for P and taking the derivative of (3) with respect to n yields the following first-order conditon for a minimum:

| (4) |

The optimal enrollment, described by (4), occurs when the change in the price that must be paid to induce the HMO's to accept one more enrollee, multiplied by the number of HMO enrollees, is just equal to the cost inefficiency of HMO's for the marginal enrollee.

Using equation (4), it is a simple matter to show that for this case the optimal fraction of enrollees in HMO's for a linear C(n) function should be

| (5) |

The payment to HMO's (price) that would elicit this level of enrollment is

| (6) |

This formula shows that, as long as some but not all persons enroll in HMO's, as the inefficiency of the FFS sector (B) goes up, the optimal price to pay the HMO sector increases. Also, as the degree of favorable selection increases (δ rises), the optimal price falls. Thus the optimal HMO price increases with the relative efficiency of HMO's and decreases as adverse selection increases.

Because the HMO payment is determined as a percentage of average costs in the FFS sector under the current AAPCC reimbursement system, it is useful to express the price to be paid to HMO's in these percentage terms. Doing so results in the optimal percentage pricing rule for the AAPCC:

| (7) |

Further results emerge from this formulation. First, the optimal price to pay to HMO's, as a percentage of FFS average costs, is always less than the percentage cost efficiency. If HMO's are 20 percent less expensive than the FFS sector, then the optimal reimbursement rate is always at least 20 percent below the average FFS sector cost. Second, as the degree of cost inefficiency increases, the optimal price ratio increases, as long as the degree of adverse selection is not too great. Taking the derivative of (7) with respect to B and simplifying yields

For B < 1/2, the derivative will be positive as long as Cmax is less than four times Cmin, as appears likely.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Allen Dobson, Lenny Gruenberg, Matt Klionsky, Chris Tompkins, Stan Wallack, and members of the Microeconomics Workshop at Boston University for helpful comments on an early draft.

This research was supported by Grant No. 18-C-98526/1-03 from the Health Care Financing Administration and a grant from the Pew Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

For a useful overview, see Vladeck (1984).

Reprint requests: Randall P. Ellis, Ph.D., Boston University, Department of Economics, College of Liberal Arts, 270 Bay State Road, Boston, Massachusetts 02215.

References

- Anderson J, Resnick A, English P, Gertman PG. Prediction of Subsequent Year Reimbursement Using the Medicare History File: I. Results from the Preliminary Model. Discussion Paper No. 45a, University Health Policy Consortium, Brandeis University; Waltham, Mass.. May 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Resnick A, Gertman PG. Prediction of Subsequent Year Reimbursement Using the Medicare History File: II. A Comparison of Several Models. Discussion Paper No. 45b, University Health Policy Consortium, Brandeis University; Jan. 1983.Waltham, Mass.: [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J, Lubitz J, Eggers P. Health Care Financing Review. No. 3. Vol. 6. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Spring. 1985. Using prior utilization to determine payments for Medicare enrollees in health maintenance organizations. HCFA Pub. No. 03198. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berki SF, Ashcraft MLF. HMO enrollment: Who joins what and why: A review of the literature. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1980 Fall;58(4):588–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers P. Health Care Financing Review. No. 3. Vol. 1. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Winter. 1980. Risk differential between Medicare beneficiaries enrolled and not enrolled in an HMO. HCFA Pub. No. 03027. Office of Research, Demonstrations, and Statistics, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers, P., and Friedlob, A.: Personal communication, 1984.

- Eggers P, Prihoda R. Health Care Financing Review. No. 2. Vol. 4. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1982. Pre-enrollment reimbursement patterns of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in “at-risk” HMO's. HCFA Pub. No. 03146. Office of Research, Demonstrations, and Statistics, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Provider behavior under prospective reimbursement: Cost sharing and supply. Journal of Health Economics. 1986 Sept.5(3):129–151. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Dowd B. Simulation of a health insurance market with adverse selection. Operations Research. 1982 Nov-Dec;30(6):1027–1042. doi: 10.1287/opre.30.6.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg L, Lambert D. Prior Utilization and the AAPCC: Simulating the Effect of Using a New Reimbursement Model on Medicare Premiums Paid to HMOs. Discussion Paper No. 57, University Health Policy Consortium, Brandeis University; Waltham, Mass.. May 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg L, Stuart N. A Health Status-Based AAPCC: The Disability-Level Approach. Discussion Paper No. 55, University Health Policy Consortium, Brandeis University; Waltham, Mass.. Dec. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg L, Tompkins C. An Analysis of Risk-Sharing and Reinsurance in Medicare HMOs. Health Policy Center, Brandeis University; Waltham, Mass.: Jun, 1984. Discussion Paper No. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Luft HS. Health Maintenance Organizations: Dimensions of Performance. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Luft HS. Health maintenance organizations and the rationing of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1982 Spring;:268–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WG, Leibowitz A, Goldberg GA, et al. A controlled trial of the effect of a prepaid group practice on use of services. N Engl J Med. 1984 Jun 7;310(23):1505–1510. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198406073102305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neipp J, Zeckhauser R. Persistence in the choice of health plans. In: Scheffler RM, Rossiter LF, editors. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research: Biased Selection in Health Care Markets. Vol. 6. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press; 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter LF, Wilensky G. Patient self-selection in HMOs. Health Affairs. 1986 Spring;:66–80. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.5.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck B. Medicare hospital payment by diagnosis-related groups. Ann Intern Med. 1984 Apr.100(4):576–591. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-4-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WP. Medicare capitation payments to HMOs in light of regression towards the mean in health care costs. In: Scheffler RM, Rossiter LF, editors. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research: Biased Selection in Health Care Markets. Vol. 6. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press; 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]