Abstract

Legislation proposed in the 100th Congress and debated during the summer of 1987 would cover prescription drug spending by Medicare enrollees after the enrollee had met a deductible. However, at the time that the legislation was proposed, there were no comprehensive estimates of the extent of current expenditures for prescription drugs by that population, nor of the expected cost of the proposed coverage.

In this article, the author estimates “current-law” drug spending by Medicare enrollees. A distribution around the average expenditure is developed, demonstrating the proportion of users that exceed any given annual expenditure and the proportion of total expenditures comprised by spending in excess of that “deductible.”

Introduction

Aged and disabled Medicare enrollees will spend an estimated $310 per person for outpatient prescription drugs in 1987. Mean spending is expected to rise to $342 in 1988 and to $432 in 1991 under current-law assumptions (that is, without considering the effects of proposed coverage of prescription drug spending by the Medicare program or of any other proposed caps on out-of-pocket health expenditures).

Spending for prescription drugs has increased more than can be explained merely by price inflation. For example, aged users of prescription drugs spent an average of $96 in 1977, according to the Current Medicare Survey for that year (Grindstaff, Hirsch, and Silverman, 1981). Had the average changed by no more than the growth in the prescription drug component of the consumer price index (CPI), that figure would reach $240 in 1987. In fact, however, there is considerable evidence of trends for the aged population in the number of prescriptions per capita and in the “real” (CPI-adjusted) cost per prescription, both of which raise the rate of growth in spending for drugs.

The distribution of spending for prescription drugs seems to be changing as well. Not only has the mean level of expenditure increased (due to price and use changes); the variance (“spread”) has increased commensurately, although the overall shape of the distribution has remained the same. Consequently, correct modeling of prescription drug spending must take into account trends in price, use, and distribution of that spending.

The purpose of this article is to present current-law estimates of prescription drug spending by Medicare enrollees. The derivation of use per capita and of cost per prescription is shown, as is the development of a distribution of that spending. The mean and distribution of expenditure are used to estimate a premium needed to cover the cost of that expenditure.

The problem of estimating drug spending is compounded by the absence of recent surveys on the subject. Subsequent to the last of the Current Medicare Surveys in 1977, the National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey (NMCUES) in 1980 and the Consumer Expenditure Surveys of 1982 through 1984 measured health expenditures. Other surveys addressed some facets of health spending or some facets of health care delivery. Consequently, the estimates presented in this article are the product of a piecing together of information found in a variety of other surveys, rather than the results of a direct survey of drug spending. However, the results of the process are, by their nature, consistent with most other estimates of drug expenditure.

Estimating prescriptions per capita

In this article, “prescriptions” refers to outpatient use of prescription drugs. Medicare hospital insurance pays for almost all prescription drugs when they are furnished to beneficiaries confined to a hospital or skilled nursing facility, but these prescription drugs are not counted in this article. However, prescription drugs given by physicians to supplementary medical insurance beneficiaries who are outpatients or who are patients in nursing homes are counted. Prescriptions include those filled or refilled by registered pharmacists in retail drug stores or hospital clinics and those dispensed in person or by telephone by physicians, with or without charge (Grindstaff, Hirsch, and Silverman, 1981).

The number of prescriptions per capita for Medicare enrollees was estimated for each of six groups: aged institutionalized, four age cohorts of the noninstitutionalized aged population (ages 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, and 80 or over), and the (nonaged) disabled.

Prescription rates for the aged population are based on results from the Current Medicare Survey (CMS), which provided annual estimates of spending in calendar years 1967 through 1977. The CMS covered a random sample of institutionalized and noninstitutionalized enrollees and elicited information on covered and noncovered medical goods and services consumed (excluding inpatient care).

The first step in estimating prescription rates was to establish a relationship between use by institutionalized and noninstitutionalized aged enrollees. Published data for 1973 show that the institutionalized used twice as many prescriptions per capita on average as did the noninstitutionalized (Deacon, 1977). In the absence of any published information to the contrary (the institutionalized population has not been surveyed since termination of the CMS in 1977), that relationship was assumed to be constant over time.

The second step in estimating prescription rates was to establish relative use among the noninstitutionalized population. Because published CMS data included only two age breaks, data from a report on the 1980 NMCUES were used (LaVange and Silverman, 1987). It was assumed that relative use of drugs among the age cohorts of the noninstitutionalized population was invariate over time. The 1980 use rates were adapted to the 1973 noninstitutionalized total through use of population estimates and the assumption of relative invariance of use over time among cohorts.

The third step in the estimation of use per capita for the aged was to establish figures for the 1967-77 period. Because the CMS had already generated estimates of aggregate prescriptions per capita, this step merely disaggregated that overall average into the various subgroups (institutionalized, and noninstitutionalized aged 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, and 80 years or over). Once again, this was done by using population estimates and assuming the Constance of relative use rates over time.

The fourth step in estimating prescription rates was to extend the 1977 figures through 1980, using data from the 1977 CMS, the 1977 National Medical Care Expenditure Survey (NMCES), and the 1980 NMCUES. NMCES and NMCUES both understated actual experience during their respective years, and it was necessary to inflate the estimates of prescription rates produced from them to conform to the results of the more representative CMS figures. To do so, relationships among the three surveys were compared with independent estimates of outpatient prescription drug sales for the total population (Trapnell and Genuardi, 1987). As a result of the comparison, NMCES figures were increased by 28 percent and NMCUES figures by 22 percent.

The fifth step in the process of estimating use per capita was to derive figures for 1980-85. Although there have been no surveys of the population concerning drug use since 1980, the National Ambulatory Care Survey (NAMCS) did survey office-based physicians in 1980 and again in 1985 to determine characteristics of drug use (Koch, 1982, 1987). The NAMCS figures are for drug “mentions,” which cover drugs prescribed or provided during a physician office visit (about 80 percent of which involve prescription drug use as defined in this article). Drugs provided or prescribed during other contacts (telephone, hospital visit, nursing home visit, etc.) are excluded. Growth in drug mentions, adjusted for population growth, was used to extend prescription rates after 1980; the 1.7 percent annual rate was slightly lower than a figure for the 1981-86 period established by similar estimates from the National Diagnostic and Therapeutic Index.

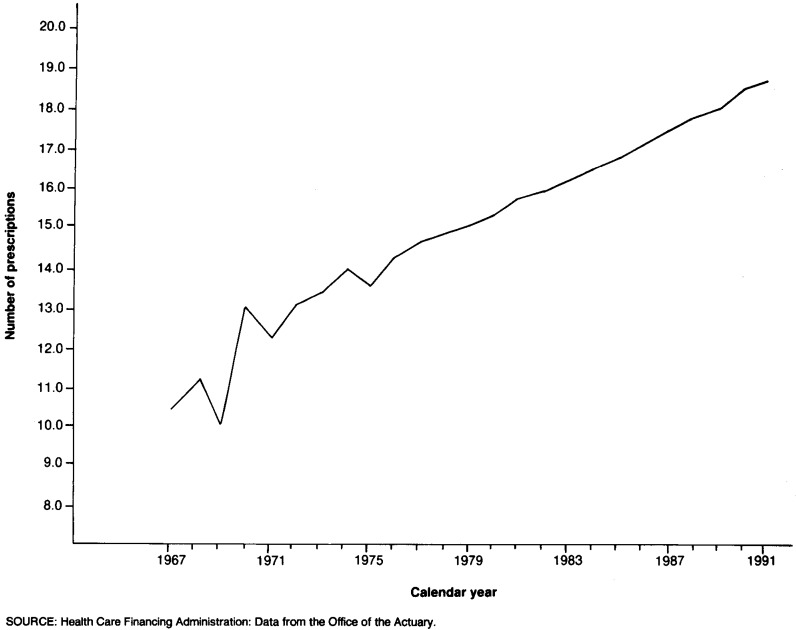

Finally, prescription rates were carried forward from 1985. In the absence of more recent data, the trend established between 1973 and 1985 was used to project prescription rates under current-law assumptions. The resulting time series, covering 1967 through 1991, shows rapid growth in use per capita between 1967 and 1973, and more moderate growth since that time (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual prescriptions per capita for the aged population: 1967-91.

Rates for the disabled population were based on a tabulation of the 1977 NMCES file. In that tabulation, prescription rates were calculated for aged Medicare enrollees and for nonaged Medicare enrollees; the latter group was presumed to be disabled. Disabled people were found to use about 30 percent more prescriptions than noninstitutionalized aged use, a factor that was assumed to hold constant over time.

Estimating cost per prescription

Estimating cost per prescription for Medicare enrollees was done using methods parallel to those used to estimate prescriptions per capita.

During the first years of the analysis, CMS data were available to estimate cost per prescription for the aged (Grindstaff, Hirsch, and Silverman, 1981). Estimates for five subgroups of the aged (institutionalized, and noninstitutionalized aged 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, and 80 years or over) were controlled to the CMS aggregate figure for years 1967 through 1977 using population, estimated prescription rates developed with the methodology described above, and relative cost per prescription for the subgroups. (Relative cost per prescription was held constant at factors determined by the 1973 CMS study [Deacon, 1977] and NMCUES data for the noninstitutional population [LaVange and Silverman, 1987].

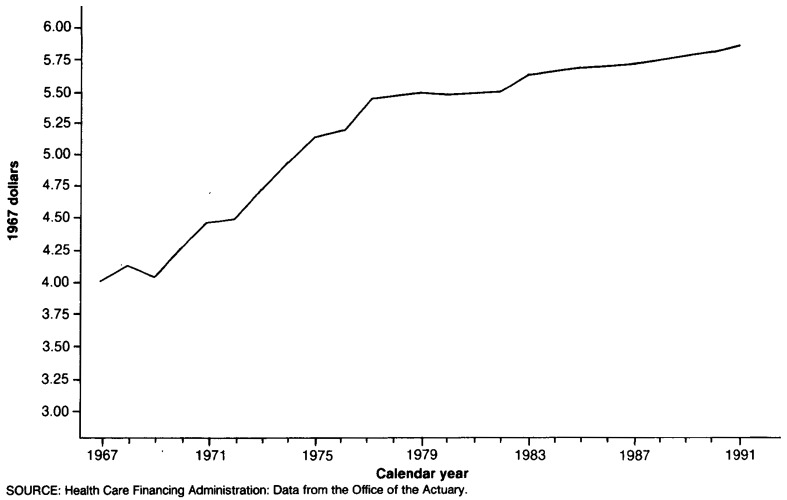

Subsequent to 1977, two methods were used to estimate cost per prescription. From 1977 through 1986, data from the National Prescription Audit conducted by IMS America were used to stand for the growth rate for cost per prescription for each of the aged subgroups. Then cost per prescription was deflated by the prescription drug component of the consumer price index (CPI-Rx) (Figure 2). Forecasted values of the CPI-Rx through 1991 were combined with an extension of the observed trend in the deflated cost per prescription to arrive at a nominal (current-dollar) cost for the aged population.

Figure 2. Constant-dollar cost per prescription for the aged population: 1967-91.

The disabled population was assumed to have the same cost per prescription as did the aged population. This assumption was based on the tabulation of NMCES data described earlier.

Estimating cost per enrollee

Once prescriptions per capita and cost per prescription were estimated, it was a simple matter to weight each group's expenditure by an enrollment count to arrive at an aggregate figure for expenditure per Medicare enrollee (Table 1). Enrollment subsequent to 1985 was estimated: The number of disabled enrollees was held constant, while the proportion of the aged population enrolled in Medicare Parts A or B was assumed to increase from 97.5 percent in 1985 to 98.0 percent in 1991.

Table 1. Medicare enrollee prescriptions per capita and prescription costs, by age, institutional status, and disability status: Selected calendar years, 1967-91.

| Reason for eligibility | 1967 | 1973 | 1977 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual prescriptions per capita | ||||||||||

| All enrollees | 10.4 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 17.4 | 17.8 | 18.1 | 18.3 | 18.7 | 19.1 |

| Aged | 10.4 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 18.0 | 18.4 | 18.7 |

| Institutionalized | 19.8 | 25.5 | 27.3 | 31.3 | 31.8 | 32.4 | 32.9 | 33.5 | 34.1 | 34.7 |

| Noninstitutionalized | 9.9 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 16.0 | 16.3 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 17.5 | 17.8 |

| 65-69 years | 8.2 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 14.4 | 14.7 |

| 70-74 years | 9.9 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 16.3 | 16.6 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.5 |

| 75-79 years | 12.3 | 15.9 | 17.0 | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 20.7 | 21.0 | 21.4 | 21.8 |

| 80 years or over | 10.9 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 18.7 | 19.0 | 19.3 |

| Disabled | — | 16.5 | 17.7 | 20.5 | 20.9 | 21.3 | 21.7 | 22.0 | 22.5 | 22.9 |

| Cost per prescription | ||||||||||

| All enrollees | $4.00 | $4.74 | $6.60 | $14.41 | $15.78 | $17.43 | $18.96 | $20.19 | $21.32 | $22.66 |

| Aged | 4.00 | 4.74 | 6.60 | 14.41 | 15.78 | 17.43 | 18.97 | 20.19 | 21.32 | 22.67 |

| Institutionalized | 4.02 | 4.74 | 6.62 | 14.72 | 16.10 | 17.80 | 19.33 | 20.59 | 21.79 | 23.10 |

| Noninstitutionalized | 4.01 | 4.73 | 6.59 | 14.41 | 15.76 | 17.43 | 18.92 | 20.15 | 21.32 | 22.60 |

| 65-69 years | 4.23 | 4.99 | 6.97 | 15.24 | 16.66 | 18.42 | 19.99 | 21.28 | 22.52 | 23.87 |

| 70-74 years | 4.10 | 4.84 | 6.76 | 14.80 | 16.19 | 17.90 | 19.43 | 20.69 | 21.90 | 23.22 |

| 75-79 years | 3.81 | 4.50 | 6.28 | 13.80 | 15.10 | 16.70 | 18.14 | 19.33 | 20.47 | 21.71 |

| 80 years or over | 3.75 | 4.42 | 6.17 | 13.54 | 14.82 | 16.40 | 17.81 | 18.98 | 20.10 | 21.32 |

| Disabled | — | 4.73 | 6.59 | 14.41 | 15.76 | 17.43 | 18.92 | 20.15 | 21.32 | 22.60 |

| Annual cost per enrollee | ||||||||||

| All enrollees | $42 | $65 | $97 | $247 | $275 | $310 | $342 | $370 | $400 | $432 |

| Aged | 42 | 64 | 95 | 242 | 270 | 304 | 336 | 364 | 392 | 424 |

| Disabled | 51 | 78 | 117 | 295 | 329 | 371 | 411 | 443 | 480 | 518 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Office of the Actuary.

Comparability with national health expenditures estimates

National health expenditure (NHE) estimates of drug spending are published by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) for years 1965 through 1986, with projections through the year 2000 (Lazenby, Levit, and Waldo, 1986; Health Care Financing Administration, 1987). The published figures combine prescription drugs with nonprescription drugs and medical sundries and represent spending for the entire population.

The NHE estimates of spending for drugs and sundries are based mainly on personal consumption expenditures (PCE) for medical nondurables, published by the Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) as part of the gross national product (GNP). PCE levels are adjusted to remove estimated payments through Medicaid and other transfer-type programs, and HCFA's estimate of government spending is added to arrive at the NHE level.

There are two reasons why the growth in the NHE figures for consumption of drugs and sundries is not a good proxy for that of Medicare enrollees' spending for prescription drugs.

First, the growth of NHE for drugs and sundries understates that of prescription drug spending. This, in turn, stems from the composition of the NHE figure and from the technique by which the PCE estimate (on which it is based) is calculated. NHE includes nonprescription drugs and drug sundries, consumption of which has grown more slowly than has consumption of prescription drugs. According to the Census Bureau's quinquennial census of retail trade, prescription drug sales through drug stores and grocery stores grew at an annual rate of 12.8 percent between 1977 and 1982 (the most recent period available), one-half a percent per year faster than growth of total retail sales of the broader “drugs, health aids, and beauty aids” (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1980, 1985). In addition, the techniques used to extrapolate PCE from the quinquennial census base tend to underestimate the growth of prescription drug spending. PCE for drugs and sundries (which, like NHE, includes more than just prescription drugs) grew at an average annual rate of 9.3 percent between 1977 and 1982, clearly less than the 12.8 percent growth or retail prescription drugs. Consequently, the NHE figures for drugs and drug sundries understate the growth in spending for prescription drugs alone.

A second reason why the NHE series cannot serve as a proxy for growth in spending for drugs by the aged is that the aged population appears to have a different trend in consumption of drugs than does the rest of the population. Data from the 1980 and 1985 NAMCS show a decline in drug mentions per capita for the total population and for the population under age 65, while those for the aged population increased over the same period.

Estimating the distribution of spending

From the standpoint of program expenditures, it is just as important to know the distribution of spending as it is to know the mean expenditure. The proportion of enrollees who spend more than a given amount per year and the amount spent by those enrollees are essential pieces of information in the calculation of program costs.

A useful candidate for the theoretical distribution is the gamma. In this distribution, the probability of a value X occurring is:

where the arithmetic mean and variance of the distrubution are:

A nonlinear least-squares fit of interval frequencies for each of the years 1967 through 1977 (Grindstaff, Hirsch, and Silverman, 1981) yields estimates of the two parameters of the gamma distribution. The values of b appear to be constant over time, and the average value of b from the 1967-77 regressions has been carried forward through time. Values for a, the scale factor, have been determined by the value of b and the arithmetic mean; in this way, the distribution for any given year will be centered on the average expenditure per enrollee.

The gamma distribution is not defined when x = 0, so that the distribution applies only to users of prescription drugs. Therefore, mean expenditure per enrollee must be translated into mean expenditure per user. Evidence from CMS, NMCES, and NMCUES suggest that the user rate has stabilized at about 78 percent since 1977. This assumption was used when projecting the distribution forward in time.

Estimating cost per enrollee

Knowledge of the mean and distribution of spending for prescription drugs allows one to calculate the current-law cost per enrollee of that spending over and above any given annual amount. To do so requires three pieces of information. First, one needs to know the proportion of users who exceed the annual spending limit. This is found by integrating the gamma function from the annual limit through infinity:

where f(x) is the gamma density function. The second piece of information needed is the proportion of expenditures over the given annual amount:

Third, one needs to know the proportion of enrollees who are users of prescription drugs. As explained earlier, it is assumed in this article that 78 percent of enrollees are users. These three pieces are then combined to determine the monthly cost per enrollee were expenditures over the deductible spread over all enrollees (users or not). If M is the average expenditure per user and P is the proportion of enrollees who are users, then the monthly cost per enrollee of expenditures in excess of k dollars per year is:

The data in Table 2 show these monthly costs for a number of alternative deductibles. By their nature, the current-law estimates shown in Table 2 do not measure the full cost of proposed Medicare coverage of prescription drugs: They exclude administrative costs and changes in consumption that would occur due to enactment of the proposed coverage. The latter item, in particular, is of unknown magnitude at this point. Based on a review of the literature, Ginsburg and Curtis (1978) suggested that a sensible range for the increase in demand caused by going from no insurance to full insurance coverage would be 50 to 150 percent. The relative size of “own-price” elasticity of demand for prescription drugs as opposed to “cross-price” elasticities (with physician services, for example) is still debated, as is the extent to which prescription drugs complement or substitute for other medical goods and services. The price of a good or service historically has risen when third-party coverage is introduced, which could raise program costs. On the other hand, program features such as generic substitution could reduce the program cost per prescription. The net effect of all these factors, although important to the ultimate decision regarding proposed coverage of drug spending, is outside the scope of this article.

Table 2. Distribution of Medicare users and their expenditures for prescription drugs and monthly expenditures per enrollee in excess of a specified deductible, by amount of deductible: Calendar years 1988-91.

| Deductible | Proportion of users who meet or exceed the annual deductible | Proportion of total expenditures that exceeds the annual deductible | Monthly expenditure per enrollee in excess of the annual deductible | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | |

| $50 | 0.8667 | 0.8751 | 0.8829 | 0.8902 | 0.9930 | 0.9939 | 0.9947 | 0.9954 | $25.50 | $27.80 | $30.30 | $32.90 |

| 100 | 0.7660 | 0.7800 | 0.7931 | 0.8054 | 0.9760 | 0.9791 | 0.9818 | 0.9841 | 22.80 | 25.10 | 27.60 | 30.20 |

| 150 | 0.6809 | 0.6990 | 0.7162 | 0.7323 | 0.9519 | 0.9579 | 0.9631 | 0.9677 | 20.50 | 22.70 | 25.10 | 27.70 |

| 200 | 0.6071 | 0.6284 | 0.6486 | 0.6677 | 0.9226 | 0.9319 | 0.9401 | 0.9473 | 18.40 | 20.60 | 22.90 | 25.40 |

| 250 | 0.5426 | 0.5660 | 0.5884 | 0.6099 | 0.8896 | 0.9024 | 0.9138 | 0.9239 | 16.50 | 18.60 | 20.90 | 23.40 |

| 300 | 0.4856 | 0.5105 | 0.5347 | 0.5578 | 0.8540 | 0.8704 | 0.8851 | 0.8981 | 14.90 | 16.90 | 19.10 | 21.50 |

| 350 | 0.4351 | 0.4611 | 0.4863 | 0.5107 | 0.8167 | 0.8366 | 0.8545 | 0.8705 | 13.40 | 15.30 | 17.40 | 19.70 |

| 400 | 0.3903 | 0.4168 | 0.4427 | 0.4680 | 0.7784 | 0.8016 | 0.8227 | 0.8417 | 12.00 | 13.90 | 15.90 | 18.10 |

| 450 | 0.3503 | 0.3770 | 0.4033 | 0.4291 | 0.7397 | 0.7661 | 0.7901 | 0.8119 | 10.80 | 12.60 | 14.50 | 16.70 |

| 500 | 0.3146 | 0.3412 | 0.3677 | 0.3937 | 0.7012 | 0.7303 | 0.7571 | 0.7816 | 9.80 | 11.40 | 13.30 | 15.30 |

| 600 | 0.2542 | 0.2800 | 0.3059 | 0.3319 | 0.6257 | 0.6596 | 0.6912 | 0.7204 | 7.90 | 9.40 | 11.10 | 13.00 |

| 700 | 0.2057 | 0.2301 | 0.2550 | 0.2802 | 0.5542 | 0.5915 | 0.6268 | 0.6599 | 6.40 | 7.80 | 9.30 | 11.00 |

| 800 | 0.1667 | 0.1893 | 0.2128 | 0.2368 | 0.4877 | 0.5273 | 0.5653 | 0.6014 | 5.20 | 6.40 | 7.80 | 9.30 |

| 900 | 0.1353 | 0.1560 | 0.1777 | 0.2004 | 0.4269 | 0.4676 | 0.5074 | 0.5456 | 4.30 | 5.30 | 6.50 | 7.90 |

| 1,000 | 0.1098 | 0.1286 | 0.1486 | 0.1696 | 0.3719 | 0.4130 | 0.4535 | 0.4930 | 3.50 | 4.40 | 5.50 | 6.70 |

| 1,500 | 0.0391 | 0.0494 | 0.0612 | 0.0745 | 0.1774 | 0.2112 | 0.2470 | 0.2843 | 1.20 | 1.70 | 2.30 | 3.00 |

| 2,000 | 0.0141 | 0.0192 | 0.0254 | 0.0330 | 0.0799 | 0.1022 | 0.1276 | 0.1559 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 1.30 |

| 3,000 | 0.0019 | 0.0029 | 0.0045 | 0.0066 | 0.0147 | 0.0218 | 0.0311 | 0.0429 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| 4,000 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 | 0.0008 | 0.0013 | 0.0025 | 0.0043 | 0.0071 | 0.0110 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| 5,000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0008 | 0.0015 | 0.0027 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

NOTES: This table is based on a gamma distribution in which the shape parameter is set at .87 and the scale parameter is adjusted to accommodate the mean expenditure per user. The estimates presented in this table are based on average expenditures per enrollee of 342, 370, 400, and 432 in 1988-91, respectively. Expenditures per user are estimated to be 438, 474, 513, and 554, in 1988-91, respectively. Enrollees include both users of prescription drugs and persons who are eligible for Medicare benefits but who do not use prescription drugs. An estimated 78 percent of enrollees are prescription drug users.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to a number of colleagues for their invaluable insights and comments: Charles R. Fisher, Mark S. Freeland, Roland E. King, and Gordon R. Trapnell (Actuarial Research Corporation). In addition, Greg Savord and Larry Schmid are owed a vote of thanks for their guidance in the development and estimation of expenditure distributions.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Daniel R. Waldo, L1, 1705 Equitable Building, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

References

- Deacon R. Current Medicare Survey report: Supplementary Medical Insurance: Characteristics of aged institutionalized enrollees, 1973. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Oct. 1977. HEW Pub. No. (SSA) 78-11702. Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg P, Curtis M. Choice of Demand Parameters for Congressional Budget Office National Health Insurance Cost Estimates. Congressional Budget Office; Washington, D.C.: Nov. 1978. Unpublished memorandum. [Google Scholar]

- Grindstaff G, Hirsch B, Silverman H. Medicare—Use of Prescription Drugs by Aged Persons Enrolled for Supplementary Medical Insurance, 1967-1977 Health Care Financing Program Statistics. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Mar. 1981. HCFA Pub. No. 03080. Office of Research, Demonstrations, and Statistics, Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary. Health Care Financing Review. No. 4. Vol. 8. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug. 1987. National health expenditures, 1986-2000. HCFA Pub. No. 03239. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Koch H. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 65. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Mar. 1982. Drug utilization in office-based practice, a summary of findings: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: United States, 1980. (13). DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 83-1726. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch H. NCHS Advance Data. No. 134. Hyattsville, MD.: May 19, 1987. Highlights of drug utilization in office practice: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1985. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 87-1250. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- LaVange L, Silverman H. National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Apr, 1987. Outpatient prescription drug utilization and expenditure patterns of noninstitutionalized aged Medicare beneficiaries. (B). Descriptive Report No. 12. DHHS Pub. No. 86-20212. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazenby H, Levit K, Waldo D. Health Care Financing Notes. No. 6. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1986. National health expenditures, 1985. HCFA Pub. No. 03232. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Adminstration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell G, Genuardi J. Consumer Expenditures for Prescription Drugs, 1971-1985. Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association; Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1987. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1977 census of retail trade: Merchandise line sales, United States. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1980. Report No. RC77-L. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1982 census of retail trade: Merchandise line sales, United States. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug. 1985. Report No. RC82-1-3. [Google Scholar]