Abstract

In recent years, concern has increased over the rapid growth of health care spending, especially spending on behalf of the aged. In 1987, those 65 years or over comprised 12 percent of the population but consumed 36 percent of total personal health care. This article is an examination of the current and future composition of the population and effects on health care spending. National health accounts aggregates for 1977 and 1987 are split into three age groups, and the consumption patterns of each group are discussed. The variations in spending within the aged cohort are also examined.

Introduction

These are troubled times for public policy on health care. The income of the aged and the portion of that income going to health care have been and continue to be high-priority issues on Capitol Hill. Concerns about these matters led to the initial passage of Medicare in 1965 and, more recently, to passage of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988. However, countervailing issues, most notably the budget deficit, generate forces to restrain growth in assistance for the aged and their health care. For these reasons, analysis of health care spending in general and spending for the aged in specific are of vital importance as the Nation sorts out its priorities.

Generally speaking, spending for health care has risen faster than has the rest of the U.S. economy over the last several decades. During the period 1977-87, personal health care expenditures grew 11.5 percent per year on average, compared with a growth rate of 8.6 percent in the gross national product. According to published estimates, personal health care expenditures—defined as spending for the direct consumption of health care goods and services— amounted to $443 billion in 1987, or almost 10 percent of the Nation's gross national product (Letsch, Levit, and Waldo, 1989).

It is well known that the aged population (people 65 years of age or over) account for a disproportionate share of health care expenditures. An estimated $162 billion was spent for personal health care during 1987 by or on behalf of the 30 million aged people in the United States; that is, 12 percent of the population accounted for 36 percent of all such spending.

In this article, we look first at the current and future composition of the Nation's population and then at its health care spending. The national health accounts aggregates are split into age groups, and the consumption patterns of each group are traced. We have emphasized spending by the aged, as this is the principal area of program responsibility of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). Concluding the report is a description of the data sources used to estimate spending for health care by age cohorts and the methods used to combine the information available.

The population data used in the report are estimates from the Social Security Administration (SSA). The health expenditure estimates come from HCFA's Office of the Actuary, Office of National Cost Estimates. Estimates for spending by age cohort are developed in a model based on microdata from the National Medical Care Expenditure Survey, aged by the SSA data and controlled to the national health accounts.

Profile of population

The U.S. population is aging steadily. People age 65 years or over (the aged cohort) currently comprise 12 percent of the 251.8 million people in the United States, and those age 19 years or under (the young cohort) account for another 29 percent (Table 1). By the year 2030, the population will have grown to 316.8 million, reflecting an average annual growth rate of only .5 percent a year. However, the size of the aged cohort will have grown by 1.8 percent a year, to 21 percent of the population. The young cohort, in contrast, will have shrunk to 23.5 percent of the total.

Table 1. Number and percent distribution of the population, by age: United States, selected calendar years 1987-2030.

| Age | 1987 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population in millions1 | |||||

| Total | 251.8 | 277.3 | 293.4 | 307.7 | 316.8 |

| Under 20 years | 73.4 | 75.9 | 73.8 | 74.2 | 74.4 |

| 20-64 years | 148.1 | 165.8 | 179.6 | 180.6 | 175.9 |

| 65 years or over | 30.2 | 35.6 | 40.0 | 52.8 | 66.5 |

| 65-69 years | 9.8 | 9.6 | 12.2 | 17.6 | 19.0 |

| 70-74 years | 7.8 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 13.8 | 17.3 |

| 75-79 years | 5.8 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 13.3 |

| 80-84 years | 3.7 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 9.0 |

| 85 years or over | 3.0 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.9 |

| Percent distribution of total population | |||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Under 20 years | 29.2 | 27.4 | 25.2 | 24.1 | 23.5 |

| 20-64 years | 58.8 | 59.8 | 61.2 | 58.7 | 55.5 |

| 65 years or over | 12.0 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 17.2 | 21.0 |

| 65-69 years | 3.9 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| 70-74 years | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 5.5 |

| 75-79 years | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 4.2 |

| 80-84 years | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.8 |

| 85 years or over | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| Percent distribution of aged population | |||||

| 65 years or over | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 65-69 years | 32.5 | 27.0 | 30.5 | 33.3 | 28.6 |

| 70-74 years | 25.8 | 25.0 | 22.7 | 26.1 | 26.0 |

| 75-79 years | 19.2 | 20.8 | 17.8 | 17.4 | 20.0 |

| 80-84 years | 12.3 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 11.0 | 13.5 |

| 85 years or over | 9.9 | 12.9 | 15.0 | 12.3 | 11.9 |

Social Security area populations as of July 1.

NOTES: Population growth is taken from the intermediate (II-B) assumptions used to prepare the 1989 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Fund. Totals may not add to 100.0 because of rounding.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the Office of the Actuary.

Changes within the aged cohort are also interesting, with a general migration toward older age. However, this trend will be reversed, starting around the turn of the century and lasting until around the year 2030 (Table 1). The reversal of trend is caused by the birth cohorts from the late 1930's and early 1940's (during which time birth rates were comparatively low) entering and passing through the aggregate aged cohort.

The impact of an ever more aged population on overall health care expenditures becomes evident once one considers that the aged consumed four times as much health care per capita as the rest of the population. If that ratio remains relatively constant in the future, aging of the population will inevitably lead to higher health expenditures.

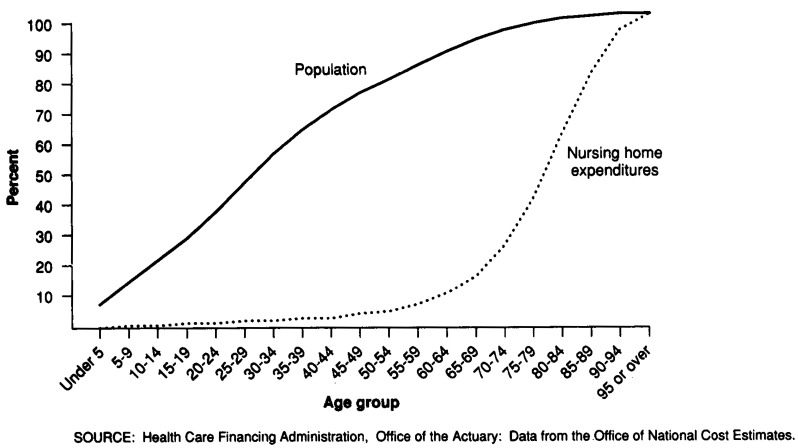

The skew in consumption of health care toward the aged population is clear from graphic analysis. The most striking example is in consumption of nursing home care (Figure 1). Almost 90 percent of 1987 nursing home expenditures were for persons age 65 or over, a group that constituted only 12 percent of the population. If consumption of nursing home care were uniform across all ages, the two lines in Figure 1 would coincide.

Figure 1. Cumulative percent distributions of population and nursing home expenditures, by age: United States, calendar year 1987.

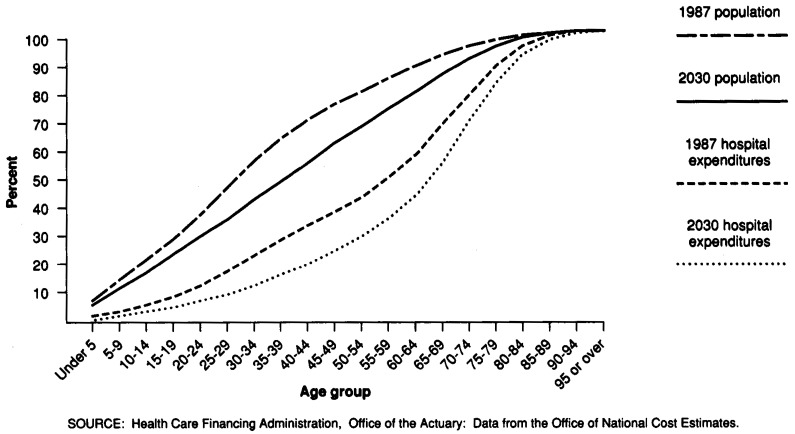

The effects of the aging of the population on hospital expenditures can be seen in Figure 2. In 1987, the aged accounted for 35 percent of hospital expenditures. In contrast, the young, although they comprised 29 percent of the population, consumed only 11 percent of hospital care. Within 50 years, the aged share will have increased to 56 percent and the share for the young will have dropped to 6 percent, shifting the expenditure curve in Figure 2 to the right.

Figure 2. Cumulative percent distributions of population and hospital expenditures, by age: United States, calendar years 1987 and 2030.

Expenditures by age

Total personal health expenditures tripled during the period 1977-87, rising from $150.3 billion to $447.0 billion (Tables 2 and 3). Spending for hospital care grew at an average annual rate of 11.1 percent. By 1987, it had reached $194.7 billion, 44 percent of all personal health care expenditures. Aggregate nursing home care expenditures rose from $13.0 billion to $40.6 billion during this period. The nursing home spending growth rate was 12.1 percent per year over the interval, a rate exceeded by the 12.4-percent annual growth of expenditures for physicians' services. Physician expenditure levels were $31.9 billion in 1977 and $102.7 billion in 1987.

Table 2. Personal health care expenditures, by age, source of funds, and type of service: United States, calendar year 1977.

| Type of service | All ages | Under 19 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| All sources | Private | Public | All sources | Private | Public | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | Medicare | Medicaid | Total | Medicare | Medicaid | |||||

| Aggregate amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $150.3 | $92.6 | $57.8 | $21.8 | $16.9 | $19.5 | $14.4 | $5.2 | $0.0 | $3.0 |

| Hospital care | 68.1 | 31.6 | 36.5 | 16.0 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Physicians' services | 31.9 | 23.8 | 8.1 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Nursing home care | 13.0 | 5.8 | 7.2 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Other personal health care | 37.3 | 31.3 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $658 | $405 | $253 | $95 | $74 | $269 | $198 | $71 | $0 | $41 |

| Hospital care | 298 | 138 | 160 | 70 | 28 | 106 | 63 | 42 | 0 | 22 |

| Physicians' services | 139 | 104 | 35 | 20 | 8 | 63 | 52 | 11 | 0 | 8 |

| Nursing home care | 57 | 26 | 32 | 2 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Other personal health care | 163 | 137 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 97 | 82 | 14 | 0 | 7 |

| Percent distribution by type of service | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital care | 45.3 | 34.2 | 63.2 | 73.6 | 38.4 | 39.3 | 32.1 | 59.2 | 58.8 | 54.4 |

| Physicians' services | 21.2 | 25.7 | 14.0 | 21.1 | 10.9 | 23.3 | 26.1 | 15.4 | 12.2 | 19.2 |

| Nursing home care | 8.7 | 6.3 | 12.5 | 1.7 | 36.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 9.5 |

| Other personal health care | 24.8 | 33.9 | 10.4 | 3.6 | 14.0 | 35.9 | 41.7 | 19.8 | 29.0 | 16.9 |

| Percent distribution by source of funds | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 61.6 | 38.4 | 14.5 | 11.2 | 100.0 | 73.5 | 26.5 | 0.1 | 15.3 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 46.4 | 53.6 | 23.5 | 9.5 | 100.0 | 60.1 | 39.9 | 0.2 | 21.3 |

| Physicians' services | 100.0 | 74.6 | 25.4 | 14.4 | 5.8 | 100.0 | 82.4 | 17.6 | 0.1 | 12.7 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 44.8 | 55.2 | 2.8 | 47.3 | 100.0 | 8.9 | 91.1 | 0.0 | 88.2 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 84.0 | 16.0 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 100.0 | 85.4 | 14.6 | 0.1 | 7.2 |

| Aggregate amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $85.6 | $62.3 | $23.2 | $2.6 | $6.8 | $45.2 | $15.9 | $29.3 | $19.1 | $7.0 |

| Hospital care | 40.2 | 24.6 | 15.6 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 20.2 | 2.4 | 17.8 | 14.1 | 1.4 |

| Physicians' services | 19.5 | 16.8 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 0.3 |

| Nursing home care | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 10.5 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 0.3 | 4.6 |

| Other personal health care | 23.6 | 20.1 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $651 | $474 | $177 | $20 | $52 | $1,856 | $653 | $1,204 | $785 | $288 |

| Hospital care | 306 | 187 | 119 | 15 | 26 | 830 | 98 | 732 | 578 | 57 |

| Physicians' services | 148 | 128 | 21 | 4 | 8 | 319 | 132 | 187 | 169 | 10 |

| Nursing home care | 17 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 10 | 432 | 207 | 224 | 14 | 190 |

| Other personal health care | 179 | 153 | 27 | 2 | 8 | 275 | 215 | 60 | 23 | 31 |

| Percent distribution by type of service | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital care | 47.0 | 39.5 | 67.1 | 73.6 | 50.6 | 44.7 | 15.1 | 60.8 | 73.6 | 19.7 |

| Physicians' services | 22.8 | 27.0 | 11.7 | 18.1 | 14.8 | 17.2 | 20.2 | 15.5 | 21.6 | 3.6 |

| Nursing home care | 2.6 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 18.4 | 23.2 | 31.7 | 18.6 | 1.8 | 66.0 |

| Other personal health care | 27.6 | 32.3 | 15.0 | 7.8 | 16.2 | 14.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 10.6 |

| Percent distribution by source of funds | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 72.8 | 27.2 | 3.1 | 8.0 | 100.0 | 35.1 | 64.9 | 42.3 | 15.5 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 61.2 | 38.8 | 4.8 | 8.6 | 100.0 | 11.8 | 88.2 | 69.6 | 6.8 |

| Physicians' services | 100.0 | 86.1 | 13.9 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 100.0 | 41.4 | 58.6 | 53.0 | 3.3 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 34.6 | 65.4 | 0.6 | 57.0 | 100.0 | 48.0 | 52.0 | 3.3 | 44.0 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 85.2 | 14.8 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 100.0 | 78.2 | 21.8 | 8.5 | 11.1 |

NOTES: Public funds include programs not shown separately. Hospital care and physicians' services include both inpatient and outpatient care.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Cost Estimates.

Table 3. Personal health care expenditures, by age, source of funds, and type of service: United States, calendar year 1987.

| Type of service | All ages | Under 19 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| All sources | Private | Public | All sources | Private | Public | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | Medicare | Medicaid | Total | Medicare | Medicaid | |||||

| Aggregate amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $447.0 | $271.8 | $175.3 | $81.2 | $49.4 | $51.9 | $38.1 | $13.8 | $0.1 | $8.9 |

| Hospital care | 194.7 | 92.6 | 102.2 | 53.3 | 17.8 | 21.2 | 12.9 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 5.2 |

| Physicians' services | 102.7 | 70.9 | 31.8 | 22.3 | 4.4 | 12.6 | 10.5 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| Nursing home care | 40.6 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 0.6 | 17.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Other personal health care | 109.0 | 87.6 | 21.4 | 5.1 | 9.4 | 17.3 | 14.6 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $1,776 | $1,079 | $696 | $323 | $196 | $745 | $547 | $198 | $1 | $128 |

| Hospital care | 773 | 368 | 406 | 212 | 71 | 305 | 186 | 119 | 1 | 74 |

| Physicians' services | 408 | 282 | 126 | 89 | 18 | 181 | 151 | 30 | 0 | 20 |

| Nursing home care | 161 | 82 | 79 | 2 | 71 | 11 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Other personal health care | 433 | 348 | 85 | 20 | 37 | 248 | 210 | 39 | 0 | 24 |

| Percent distribution by type of service | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital care | 43.6 | 34.1 | 58.3 | 65.6 | 36.0 | 40.9 | 33.9 | 60.3 | 60.5 | 58.0 |

| Physicians' services | 23.0 | 26.1 | 18.1 | 27.4 | 9.0 | 24.3 | 27.6 | 15.0 | 17.7 | 15.8 |

| Nursing home care | 9.1 | 7.6 | 11.4 | 0.7 | 36.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 7.7 |

| Other personal health care | 24.4 | 32.2 | 12.2 | 6.3 | 19.0 | 33.3 | 38.3 | 19.6 | 21.9 | 18.4 |

| Percent distribution by source of funds | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 60.8 | 39.2 | 18.2 | 11.0 | 100.0 | 73.5 | 26.5 | 0.1 | 17.2 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 47.5 | 52.5 | 27.4 | 9.1 | 100.0 | 60.9 | 39.1 | 0.2 | 24.4 |

| Physicians' services | 100.0 | 69.1 | 30.9 | 21.7 | 4.3 | 100.0 | 83.6 | 16.4 | 0.1 | 11.2 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 50.9 | 49.1 | 1.4 | 43.9 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 92.7 | 0.0 | 91.7 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 80.4 | 19.6 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 100.0 | 84.4 | 15.6 | 0.1 | 9.5 |

| Aggregate amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $233.1 | $173.0 | $60.0 | $8.9 | $21.0 | $162.0 | $60.6 | $101.5 | $72.2 | $19.5 |

| Hospital care | 105.5 | 69.6 | 36.0 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 67.9 | 10.1 | 57.9 | 47.3 | 3.3 |

| Physicians' services | 56.7 | 48.5 | 8.2 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 33.5 | 11.9 | 21.6 | 20.3 | 0.5 |

| Nursing home care | 7.0 | 1.4 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 32.8 | 19.2 | 13.6 | 0.6 | 11.9 |

| Other personal health care | 63.9 | 53.5 | 10.4 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 27.8 | 19.5 | 8.3 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | $1,535 | $1,139 | $395 | $59 | $138 | $5,360 | $2,004 | $3,356 | $2,390 | $644 |

| Hospital care | 695 | 458 | 237 | 39 | 61 | 2,248 | 333 | 1,915 | 1,566 | 110 |

| Physicians' services | 373 | 319 | 54 | 13 | 17 | 1,107 | 393 | 714 | 671 | 17 |

| Nursing home care | 46 | 9 | 37 | 0 | 34 | 1,085 | 634 | 452 | 19 | 395 |

| Other personal health care | 421 | 353 | 68 | 7 | 26 | 920 | 644 | 276 | 135 | 123 |

| Percent distribution by type of service | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital care | 45.3 | 40.2 | 59.9 | 66.0 | 44.1 | 41.9 | 16.6 | 57.1 | 65.5 | 17.1 |

| Physicians' services | 24.3 | 28.0 | 13.6 | 22.6 | 12.1 | 20.7 | 19.6 | 21.3 | 28.1 | 2.6 |

| Nursing home care | 3.0 | 0.8 | 9.3 | 0.2 | 24.7 | 20.2 | 31.6 | 13.5 | 0.8 | 61.2 |

| Other personal health care | 27.4 | 30.9 | 17.2 | 11.1 | 19.1 | 17.2 | 32.2 | 8.2 | 5.6 | 19.1 |

| Percent distribution by source of funds | ||||||||||

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 74.2 | 25.8 | 3.8 | 9.0 | 100.0 | 37.4 | 62.6 | 44.6 | 12.0 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 65.9 | 34.1 | 5.6 | 8.8 | 100.0 | 14.8 | 85.2 | 69.7 | 4.9 |

| Physicians' services | 100.0 | 85.6 | 14.4 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 100.0 | 35.5 | 64.5 | 60.6 | 1.5 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 20.6 | 79.4 | 0.3 | 74.1 | 100.0 | 58.4 | 41.6 | 1.7 | 36.4 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 83.8 | 16.2 | 1.6 | 6.3 | 100.0 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 14.7 | 13.3 |

NOTES: Public funds include programs not shown separately. Totals differ from those published elsewhere because of the inclusion of preliminary benchmarked prescription drug figures. Hospital care and physicians' services include both inpatient and outpatient care.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Cost Estimates.

Reflecting the increasing numbers of people age 65 years or over, consumption of health care by the aged grew at an average annual rate of 13.6 percent, reaching $162.0 billion in 1987. Consumption by the aged in 1987 constituted 36 percent of all personal health care, up from 30 percent in 1977. In 1987, $67.9 billion were spent for hospital care of the aged and $33.5 billion for physicians' services. The growing share of spending accounted for by this cohort reflects mostly the change in their relative numbers, as expenditure per capita has exhibited similar trends across age groups.

The age groups differed not only in the level of spending but also in the different means of paying for the care consumed. Overall, private sources paid for 61 percent of personal health care, with Medicare and Medicaid picking up most of the remainder. However, private sources paid for 74 percent of care for people under age 65, and public sources paid for 63 percent of consumption by the aged. These payment shares have remained fairly constant over time.

The distribution of payment sources for any given health service, although fairly constant over time, varies across services and age groups. In 1987, private sources paid for 48 percent of aggregate hospital care, 69 percent of physicians' services, and 51 percent of nursing home care. (Public sources paid for the remainder in each category.) Medicare, a public program, paid for 27 percent of hospital care, 22 percent of physicians' services, and 1 percent of nursing home care.

For the aged, the private share of spending was 15 percent for hospital care, 36 percent for physicians' services, and 58 percent for nursing home care. Public payments comprised 85, 64, and 42 percent of spending for those same service types. Medicare paid for about 70 percent of hospital care and about 61 percent of physicians' services for the aged, as well as for 2 percent of their nursing home care. Medicaid paid for 36 percent of nursing home care expenditures for the aged. Given that long-term care insurance is relatively new and that few people have this type of coverage, most private nursing home payments must be made by the aged or their families.

Variances within aged cohort

Per capita spending for personal health care across the entire population in 1987 was $1,776. Spending for the non-aged amounted to $1,286 per person; that for the aged was $5,360. Within the aged cohort, per capita spending increased by age and varied considerably by type of service and source of payment (Table 4).

Table 4. Per capita personal health care expenditures for persons 65 years of age or over, by source of funds, age, and type of service: United States, calendar year 1987.

| Source of funds and age | Total | Private | Medicare | Medicaid | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal health care | |||||

| 65 years or over | $5,360 | $2,004 | $2,391 | $645 | $321 |

| 65-69 years | 3,728 | 1,430 | 1,849 | 245 | 204 |

| 70-74 years | 4,424 | 1,564 | 2,234 | 357 | 268 |

| 75-79 years | 5,455 | 1,843 | 2,685 | 569 | 358 |

| 80-84 years | 6,717 | 2,333 | 3,023 | 908 | 453 |

| 85 years or over | 9,178 | 3,631 | 3,215 | 1,742 | 591 |

| Hospital care | |||||

| 65 years or over | 2,248 | 333 | 1,566 | 110 | 239 |

| 65-69 years | 1,682 | 312 | 1,144 | 67 | 158 |

| 70-74 years | 2,062 | 327 | 1,431 | 93 | 212 |

| 75-79 years | 2,536 | 341 | 1,786 | 127 | 283 |

| 80-84 years | 2,935 | 355 | 2,070 | 161 | 348 |

| 85 years or over | 3,231 | 376 | 2,246 | 198 | 411 |

| Physicians' services | |||||

| 65 years or over | 1,107 | 393 | 671 | 17 | 26 |

| 65-69 years | 974 | 380 | 558 | 14 | 22 |

| 70-74 years | 1,086 | 389 | 655 | 17 | 25 |

| 75-79 years | 1,191 | 398 | 745 | 19 | 29 |

| 80-84 years | 1,246 | 407 | 789 | 20 | 31 |

| 85 years or over | 1,262 | 420 | 792 | 20 | 31 |

| Nursing home care | |||||

| 65 years or over | 1,085 | 634 | 19 | 395 | 38 |

| 65-69 years | 165 | 94 | 5 | 60 | 6 |

| 70-74 years | 360 | 205 | 11 | 131 | 13 |

| 75-79 years | 802 | 461 | 22 | 292 | 28 |

| 80-84 years | 1,603 | 927 | 37 | 584 | 56 |

| 85 years or over | 3,738 | 2,191 | 56 | 1,361 | 131 |

| Other personal health care | |||||

| 65 years or over | 920 | 644 | 135 | 123 | 18 |

| 65-69 years | 907 | 644 | 142 | 103 | 18 |

| 70-74 years | 916 | 644 | 137 | 117 | 18 |

| 75-79 years | 925 | 644 | 133 | 130 | 18 |

| 80-84 years | 934 | 644 | 128 | 144 | 18 |

| 85 years or over | 947 | 645 | 121 | 164 | 18 |

NOTE: Hospital care and physicians' services include both inpatient and outpatient care.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Cost Estimates.

In 1987, per capita spending on personal health care for those 85 years of age or over was 2½ times that for people age 65-69 years. For hospital care, per capita consumption was twice as great for those age 85 or over as for those age 65-69, and for nursing homes, it was 23 times as great. However, consumption of physicians' services was relatively even among the aged subgroups.

Among payers, the difference in per capita spending for personal health care was most pronounced for Medicaid. In 1987, Medicaid spending for those 85 or over was seven times that for people 65-69 years and three times greater than the spending for people 75-79 years. This variance is attributable to the heavy concentration of Medicaid money in nursing home care, which the old-old (85 years or over) use much more than do others. The difference is smaller in Medicare, whose spending for the oldest group was double that for the young-old (65-69 years). Medicare paid for 45 percent of the personal health care consumption of the aged, but the Medicare share decreased from 50 percent to 35 percent as age increased. This resulted from the increased importance among the old-old of nursing home care expenditures, a category of spending for which Medicare is a negligible source of funds.

As mentioned earlier, the biggest factor in spending difference among aged subgroups is expenditure for nursing home care. In 1987, nursing home care accounted for only 4 percent of the total per capita spending for those age 65-69 but accounted for 41 percent of spending for those age 85 or over. Similarly, nursing home care accounted for 24 percent of Medicaid money spent for the young-old and for 78 percent of funds spent for the oldest old.

Sources of data

Our ability to separate health care spending among age groups is severely limited by the absence of a recent, reliable data base from which to operate. Subsequent to a 1980 national survey of the noninstitutionalized population, there had been no national person-level survey of health expenditures until the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES). Unfortunately, even preliminary expenditure data from NMES will not be available until well into 1989 at the earliest, leaving us with a considerable time gap to be filled in. Compounding the difficulty posed by the absence of expenditure data are the fundamental changes in health care financing brought about by cost-containment pressures in the period since 1980. Presumably, these payment reforms will have had an effect on the consumption patterns that were measured in the surveys conducted prior to that time.

Lacking a single, consistent source of data on health care spending, we made use of several different sources of information to prepare the estimates discussed earlier.

Program data

Administrative data from the Medicare and Medicaid programs and from the Veterans Administration were used to split those programs' expenditures among the age groups reported here.

National Medicare Care Expenditure Survey (NMCES) and National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey (NMCUES)

In 1977, the National Center for Health Services Research conducted NMCES, a survey of the noninstitutionalized population's use of and spending for health care. Data from NMCES were used to create the basic splits among age groups, as described later. In 1980, NMCUES was conducted by HCFA and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to determine roughly the same types of information. Data on spending for other professional services from the NMCUES data base rather than data from NMCES are used here because they conform more closely to the definitions of the national health accounts.

Current Medicare Survey (CMS)

From 1967 through 1977, the Social Security Administration (predecessor to HCFA in responsibility for the Medicare program) conducted a monthly survey of Medicare supplementary medical insurance enrollees. A detailed analysis of the 1973 CMS data on institutionalized enrollees (Deacon, 1977) was used to augment NMCES information on the noninstitutionalized population.

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

NCHS conducts a recurrent survey of the noninstitutionalized population to determine use of health care goods and services. Data from NHIS were used in part to extrapolate NMCES data on physicians' and dentists' services forward in time.

National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS)

NCHS also conducts an ongoing survey of short-stay hospital discharge records. NHDS data were used in part to extrapolate NMCES data on inpatient hospital use forward in time.

1980 Census of Population

Date from the 1980 census were used to determine institutionalization rates for age and sex cohorts of the population. These rates were combined with other data, as described later.

We have not mentioned the recurrent Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX), conducted by the Labor Department's Bureau of Labor Statistics. Information on family (more accurately, “consumer unit”) out-of-pocket spending for medical care is collected in CEX, but survey output cannot be disaggregated to the person-level data needed to make age splits of health care spending. In addition, information on third-party spending is largely absent from CEX, as is spending by the institutionalized population (including nursing home residents). Finally, the trend in CEX medical care data is not easily ascertained. For these reasons, we did not rely on the survey.

Estimation methods

To split health care spending among age groups, we disaggregated spending for various types of health goods and services for each constituent source of payment (Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) and then split those sources' payments among the age groups. However, the heterogeneity of the data sources required a concomitant heterogeneity of estimation techniques and procedures.

For this article, we separated the population into three age groups. The youngest group comprises people under 19 years of age; the oldest group comprises those 65 years of age or over. The balance of the population (ages 19-64) falls into the middle category.

Medicare

Medicare provides hospital and other medical benefits to 31.7 million people, of whom 28.8 million are eligible on the basis of age and 2.9 million on the basis of disability. During the estimation period, the program was divided into two parts: hospital insurance (HI) and supplementary medical insurance (SMI). Each part required different handling.

HI benefits were split between the aged and disabled using program benefit payment data. A further split of benefits for the disabled between those under 19 years of age and those 19 or over was made using special tabulations of HCFA's Person Summary Files, collections of bills received within 12 months (currently) of the end of the year for a sample of enrollees (presently 25 percent of disabled enrollees).

SMI benefits were split between the aged and the disabled using actuarial data tabulations of benefits by Medicare status code (which identifies the basis of an enrollee's eligibility) and type of service. Again, the disabled were split into two age groups using the Person Summary File. However, additional service disaggregation was needed for the SMI benefit data. Physicians' services, durable medical equipment, ambulance services, and other professional services were separated at the national level using payment record data, SMI summary data, and analytic files. Each age group was assumed to have the same pattern of disaggregation as was exhibited at the national level. In addition, spending for services of freestanding dialysis centers was separated from other outpatient hospital billings, and benefits were split using published program statistics and tabulations of the 5-percent provider bill file.

Medicaid

Medicaid benefits (vendor payments) were divided among age groups using data tabulated from HCFA Form 2082, an annual report filed by each State at the close of the year. Form 2082 contains aggregate information on expenditures for various services, by age of recipient. For the purposes of this article, adjustments were made to the tabulated data to make them conform to the desired age groups and to national health expenditures service definitions.

Veterans Administration

Hospital care and nursing home care were disaggregated using special Veterans Administration (VA) tabulations of 1977, 1980, 1985, and 1987 patient treatment files covering VA facilities. The same characteristics were assumed to apply to patients in non-VA facilities.

Benefits from the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the VA (CHAMPVA) were split among age groups in two steps. First, inpatient care and outpatient physician visits were allocated to the various cohorts using distributions of beneficiaries from the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services. These distributions were available for 1982 and 1987 and were interpolated and extrapolated using data on the CHAMPVA-eligible population. Second, NMCES data were used to construct expenditure ratios for each group, comparing each type of expenditure (dentist, drugs, etc.) with physician spending. These ratios, combined with the CHAMPVA physician figures, were used to allocate the remaining CHAMPVA spending among the age groups.

Outpatient care provided by the VA was treated in three parts. First, hospital outpatient care was separated from other outpatient care and was allocated among the three age groups using VA data on overall medical and surgical hospital discharges. VA data on the characteristics of physician visits and on age-adjusted visit rates were used to split physician services. Finally, the NMCES-based ratios were combined with outpatient physician spending and used to disaggregate the remaining service outlays.

Medicare copayments and related spending

Given our emphasis on the aged population, we created a separate subsource for payments related to Medicare benefits. These payments take two forms for estimation purposes.

Deductible and coinsurance amounts are the beneficiaries' portion of Medicare allowed charges. For the HI program, Medicare actuaries had completed estimates of total copayments and of copayments by the aged population. The difference between the two—copayments by beneficiaries under age 65—was split between the age groups under 19 years and 19-64 years on the basis of benefit payments themselves. SMI copayment estimates had been made by status code, allowing separation of the aged and disabled populations. Again, the disabled portion was allocated to the two younger age groups on the basis of benefit payments. In both cases, copayments were distributed among services in proportion to benefits (taking into account differences in coinsurance requirements).

Disallowed charges and reasonable-charge reductions on unassigned claims are charges that Medicare does not recognize. The former are charges for services not covered by Medicare or for people not covered by Medicare; the latter are the difference between the actual charge and the maximum allowed by the program. Both types of charges were split among the three age groups on the basis of benefit payments.

Although these payments were allocated as a separate subsource, in fact, they may be made by any of a number of payers—medigap insurer, patient, Medicaid, etc.—or may not be paid at all. For the purposes of allocating expenses among age groups, however, HCFA assumed that all such payments were made from private funds. The estimation error resulting from this simplification is probably negligible.

Other private and other government

For these two subsources of payment, a three-step process was employed. First, a 1977 level was established using NMCES data and the other sources. Second, in each subsequent year estimated, the 1977 level for each group was increased to account for three factors:

Gross population change.

Changes in the age and sex distribution within the age group. This factor was developed using various NMCES, NMCUES, NHIS, and NHDS data.

Changes in use per capita. This factor, which captures changes other than those created by demographic shifts, was based on data from NHIS and NHDS. It was used only for hospital care and physicians' and dentists' services.

After the 1977 level had been adjusted for these trend changes, it was further adjusted to reflect use by institutionalized members of the age group. This adjustment was made using information on population growth, institutionalization rates from the 1980 census, and relative use factors for the institutionalized from the 1973 CMS.

Control to published figures

After each source of payment had been disaggregated into three age groups, the results were scaled up or down to match the national amount reported for that service and source in HCFA's annual series on national health expenditures. As explained later, an exception to this rule was made for drugs and medical sundries, for which a revised time series of national spending was substituted for the published data.

Weakness of estimates produced

As mentioned earlier, the process of estimating health spending by the various age groups is hampered by the absence of recent expenditure data. This weakness takes several forms.

The sources of information on dollar volume are not well suited to the purpose at hand. For example, Medicaid data are much more reliably disaggregated by basis of eligibility than by age of recipient. VA program data do not have the age orientation required, and even the Medicare data contain little distinction among age groups other than the aged. The NMCES and CMS data bases are more than 10 years old by now, and the market for health care has changed considerably in that time. Further, a one-time snapshot of the institutionalized population's use of care relative to that of the noninstitutionalized population will not capture changes that occur over time.

Surveys of provider contacts are not entirely appropriate to the study either. NHIS, for example, has been affected by definitional changes over time, reducing the effectiveness of NHIS data in reflecting trends. Both NHIS and NHDS are limited to specific subpopulations—NHIS to the noninstitutionalized population and NHDS to short-stay hospitals; thus, their data do not reflect trends in use completely. More importantly, data from surveys of this sort cannot reflect intensity of service, an essential determinant of the cost of the contact.

Finally, the national figures to which the results of the estimation process are controlled are scheduled for revision. HCFA staff are reexamining the data sources, methods, and definitions used in constructing estimates of national health expenditures. This benchmark effort is time consuming and not straightforward, and it is not clear at this time what the final effect of the revisions would be on the age estimates presented here.

Earlier, it was noted that revised national figures for drugs and sundries were used in preparing this article. This was done to avoid a serious distortion of the age groups' shares of the total. As part of the benchmark effort, it was determined that the current national figures for drugs and sundries do not include spending for outpatient drugs dispensed by mail order establishments, grocery stores, and other nonpharmacy stores. The dollar volume omitted was substantial and growing as a proportion of the total. In order accurately to reflect spending by the aged population for drugs (Waldo, 1987), we felt it advisable to insert preliminary revised figures for the total as well; otherwise, spending by the two younger age groups would be understated.

Conclusion

From the bits and pieces of information available, we have constructed a mosaic that shows that the aged spend four times as much per capita for health care as the non-aged do. Further, the evidence is that, within the aged cohort, which is grossly defined, the old-old spend much more than the young-old do. Although a mosaic is not the same as a photograph, it can serve as a credible stand-in for an actual observation of what is happening, provided that one remembers the limitations of the construct.

Throughout this article, we have called attention to the risk that is run when estimating expenditures in the absence of pertinent data. The evidence presented here is fragmentary and often indirect. The aggregate levels of expenditure themselves are subject to revision. The actual trends in consumption and financing shares depend on the correct imputation of intensity, of relative price, and of other factors, but data on these topics are not available from current surveys.

Availability of data from the. 1987 NMES should help our understanding, or at least our quantification, of age differences in health care spending. NMES will provide a unified measurement of level and distribution of health care spending in the aftermath of public and private cost-containment efforts. For that reason, this article must be viewed as a stop-gap device, with better information to come.

Perhaps even more important than collection of reliable point estimates, however, is a reliable recurrent survey of the population. Data from cross-sectional surveys cannot be used to identify trends such as spousal impoverishment and acute care preceding institutionalization. HCFA staff currently are exploring the feasibility of a recurrent survey of the Medicare population that combines longitudinal and cross-sectional components, but the results of such a survey, even with the most expeditious implementation, would be unavailable in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared in the Office of National Cost Estimates—Ross H. Arnett, III, Director. The authors are grateful to Helen Lazenby for preparing the estimates of spending by age for the public programs and to Gerald Adler, George Chulis, Charles Fisher, Mark Freeland, and Katharine Levit for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Carol Pearson, Room L-1, EQ05, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

References

- Deacon R. Current Medicare Survey Report: Supplementary Medical Insurance: Characteristics of Aged Institutionalized Enrollees, 1973. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Oct. 1977. DHEW Pub. No. (SSA) 78-11702. Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Letsch S, Levit K, Waldo D. Health Care Financing Review. No. 2. Vol. 10. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Winter. 1988. National health expenditures, 1987. HCFA Pub. No. 03276. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo D. Health Care Financing Review. No. 1. Vol. 9. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Fall. 1987. Outpatient prescription drug spending by the Medicare population. HCFA Pub. No. 03240. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]