Abstract

In this article, the authors present a scenario for health expenditures during the 1990s. Assuming that current laws and practices remain unchanged, the Nation will spend $1.6 trillion for health care in the year 2000, an amount equal to 16.4 percent of that year's gross national product. Medicare and Medicaid will foot an increasing share of the Nation's health bill, rising to more than one-third of the total. The factors accounting for growth in national health spending are described as well as the effects of those factors on spending by type of service and by source of funds.

Introduction

Concern over rapid increases in health care spending is reaching a fevered pitch. Rapid growth in expenditures is not new: Spending for health care has grown faster than the overall economy in almost every one of the last 30 years. As a direct result of differential growth, health expenditures have risen as a share of our Nation's gross national product (GNP), from 5.3 percent in 1960 to 11.6 percent in 1989. This percentage is widely perceived as a measure of the impact of health expenditures on the Nation's ability to finance health care. Therefore, a flurry of renewed concern resulted when the combination of economic stagnation and “business as usual” in the health care sector drove health expenditures as a percent of the GNP to a projected 12.3 percent in 1990.

This concern has been heightened by two additional factors. First, government health programs are in serious financial difficulty. The trust fund for the Federal hospital insurance (HI) program (better known as Medicare Part A), which derives most of its income from payroll taxes, is currently projected to be exhausted in 2005. Unless additional sources of revenue are tapped, benefits would need to be reduced by $46 billion in that year. Ultimately, the program would need to be cut by more than 50 percent. In addition, State-operated Medicaid programs, which are financed through a combination of State and Federal taxes, are in generally dire financial straits. State income taxes dwindle during economic slowdowns, but program demands increase with the cost of health care in general and with the number of unemployed and low-income residents of the State.

Second, private financing of health care is reaching a watershed. Employer payments for health care (including health-related payroll taxes), which amounted to 14 percent of aggregate after-tax profits in 1965, today exceed after-tax profits (Levit et al., 1991a). The distribution of that burden is uneven across employers, further disadvantaging some. Yet, despite the large private expenditure for health care insurance, as many as 15 percent of Americans lack even the most rudimentary health insurance. Between 33 and 38 million people have—either by choice or not—neither private nor public insurance. And many Americans have little insurance protection against truly catastrophic medical expenses.

Given these factors, an unusual chorus of voices is calling for reform of the U.S. health care system. Some large employers and conservative policymakers, traditionally leery of government intervention in private matters, see national reform as a way to relieve themselves of a fringe benefit that is uncontrollable as well as being a source of contract dispute. Liberal policymakers see reform as necessary to extend health care coverage to the uninsured and underinsured population. Even provider organizations, some of which have traditionally been hostile to government attempts to change market rules, have recently offered proposals for reform of the system.

In light of the clamor for reform, it is instructive to speculate on what health expenditures might look like in the next 10 years in the absence of any such reform. To do so can yield insights regarding which services and goods will experience more demand than others. In addition, a projection scenario can provide a “big picture” for the various parties paying for health care.

In this article, we have used an actuarial projection model of the health care sector to project national health expenditures (NHE) through the end of the century. The scenario is tied to the assumptions and conclusions of the Medicare actuaries concerning progress of that program, providing the context for discussion of the future of Medicare. Use of the projection model also facilitates a discussion of the trends in the use, intensity, and price of various types of health goods and services.

Of course, such a model does not predict the future. Macroeconomic shocks, reforms in health care financing and delivery, technological breakthroughs, and unexpected changes in morbidity and mortality all affect what will happen. What the model does show is what might plausibly happen if current mechanisms, laws, and programs continue in existence through the end of the century. Thus, the model provides a “base case” against which the advantages and disadvantages of proposed reforms can be measured.

Detailed Tables 6-10 at the end of this article show expenditures for health care for selected years 1966 through 2000, both by type of service and by source of funds. Data figures from the detailed tables are highlighted throughout this article.

Table 6. National health expenditures aggregate and per capita amounts, percent distribution, and average annual percent growth, by source of funds: Selected years 1965-2000.

| Item | 1965 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1989 | Projected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $41.6 | $132.9 | $249.1 | $420.1 | $604.1 | $670.9 | $738.2 | $809.0 | $1,072.7 | $1,615.9 |

| Private | 31.3 | 77.8 | 143.9 | 245.0 | 350.9 | 389.3 | 421.1 | 457.4 | 592.2 | 859.4 |

| Public | 10.3 | 55.1 | 105.2 | 175.1 | 253.3 | 281.6 | 317.1 | 351.6 | 480.5 | 756.5 |

| Federal | 4.8 | 36.4 | 72.0 | 123.6 | 174.4 | 192.2 | 215.7 | 238.8 | 324.8 | 517.6 |

| State and local | 5.5 | 18.7 | 33.2 | 51.5 | 78.8 | 89.4 | 101.4 | 112.8 | 155.7 | 238.8 |

| Number in millions | ||||||||||

| U.S. population1 | 204.0 | 224.7 | 235.3 | 247.2 | 257.0 | 259.6 | 262.1 | 264.6 | 272.0 | 282.9 |

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Gross national product | 705 | 1,598 | 2,732 | 4,015 | 5,201 | 5,463 | 5,650 | 6,045 | 7,284 | 9,865 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 204 | 592 | 1,059 | 1,699 | 2,351 | 2,585 | 2,817 | 3,057 | 3,944 | 5,712 |

| Private | 154 | 346 | 612 | 991 | 1,365 | 1,500 | 1,607 | 1,729 | 2,178 | 3,038 |

| Public | 50 | 245 | 447 | 708 | 985 | 1,085 | 1,210 | 1,329 | 1,767 | 2,674 |

| Federal | 24 | 162 | 306 | 500 | 679 | 741 | 823 | 902 | 1,194 | 1,830 |

| State and local | 27 | 83 | 141 | 208 | 307 | 344 | 387 | 426 | 572 | 844 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 75.3 | 58.5 | 57.8 | 58.3 | 58.1 | 58.0 | 57.0 | 56.5 | 55.2 | 53.2 |

| Public | 24.7 | 41.5 | 42.2 | 41.7 | 41.9 | 42.0 | 43.0 | 43.5 | 44.8 | 46.8 |

| Federal | 11.6 | 27.4 | 28.9 | 29.4 | 28.9 | 28.7 | 29.2 | 29.5 | 30.3 | 32.0 |

| State and local | 13.2 | 14.1 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 14.8 |

| Percent of gross national product | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 5.9 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 14.7 | 16.4 |

| Average annual percent growth from previous year shown | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | — | 12.3 | 13.4 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 8.5 |

| Private | — | 9.5 | 13.1 | 11.2 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 7.7 |

| Public | — | 18.3 | 13.8 | 10.7 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 9.5 |

| Federal | — | 22.4 | 14.6 | 11.4 | 9.0 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 9.8 |

| State and local | — | 13.1 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 11.3 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 8.9 |

| U.S. population1 | — | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Gross national product | — | 8.5 | 11.3 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 6.3 |

July 1 Social Security area population estimates.

NOTE: Columns may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Table 10. Factors accounting for growth in expenditures for selected categories of national health expenditures, by 5-year periods: 1975-2000.

| Type of expenditure and period | Total | Economywide factors | Health-sector specific factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| General inflation1 | Population | Utilization2 | Intensity3 | Sector-specific price inflation | ||

|

| ||||||

| Percent distribution | ||||||

| Physician services | ||||||

| 1975-1980 | 100.0 | 63.3 | 7.7 | −5.9 | 20.8 | 14.1 |

| 1980-1985 | 100.0 | 45.7 | 8.6 | 2.0 | 23.3 | 20.4 |

| 1985-1990 | 100.0 | 29.2 | 8.3 | 3.7 | 37.5 | 21.4 |

| 1990-1995 | 100.0 | 35.2 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 37.5 | 10.8 |

| 1995-2000 | 100.0 | 42.0 | 8.3 | 5.2 | 36.5 | 8.0 |

| Inpatient hospital | ||||||

| 1975-1980 | 100.0 | 50.3 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 28.6 | 9.3 |

| 1980-1985 | 100.0 | 51.4 | 9.7 | −42.8 | 60.1 | 21.6 |

| 1985-1990 | 100.0 | 44.6 | 12.7 | −23.2 | 41.4 | 24.5 |

| 1990-1995 | 100.0 | 44.1 | 10.9 | 8.8 | 16.8 | 19.4 |

| 1995-2000 | 100.0 | 47.8 | 9.5 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 16.1 |

| Outpatient hospital | ||||||

| 1975-1980 | 100.0 | 43.0 | 5.2 | 8.7 | 35.1 | 8.0 |

| 1980-1985 | 100.0 | 32.7 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 39.9 | 13.7 |

| 1985-1990 | 100.0 | 21.2 | 6.0 | 30.6 | 30.6 | 11.6 |

| 1990-1995 | 100.0 | 24.5 | 6.1 | 26.2 | 32.4 | 10.8 |

| 1995-2000 | 100.0 | 37.2 | 7.4 | 14.0 | 28.9 | 12.6 |

| Nursing home excluding ICF/MR | ||||||

| 1975-1980 | 100.0 | 56.8 | 6.9 | 14.2 | 16.7 | 5.5 |

| 1980-1985 | 100.0 | 50.6 | 9.5 | 1.1 | 26.8 | 12.0 |

| 1985-1990 | 100.0 | 38.4 | 10.9 | 2.6 | 32.6 | 15.4 |

| 1990-1995 | 100.0 | 40.7 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 31.0 | 9.4 |

| 1995-2000 | 100.0 | 45.9 | 9.1 | 13.6 | 24.4 | 7.1 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | ||||||

| 1975-1980 | 100.0 | 84.9 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 7.8 | −2.9 |

| 1980-1985 | 100.0 | 54.8 | 10.3 | 0.0 | −9.3 | 44.2 |

| 1985-1990 | 100.0 | 41.9 | 11.9 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 46.4 |

| 1990-1995 | 100.0 | 55.7 | 13.8 | 0.0 | −11.3 | 41.8 |

| 1995-2000 | 100.0 | 66.5 | 13.1 | 0.0 | −2.7 | 23.0 |

General inflation is measured by the gross national product implicit price deflator.

Per capita days or visits.

Real services per day or per visit.

NOTE: ICF/MR is intermediate care facility for the mentally retarded.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Projection model

The model used to develop the scenario we discuss is built upon actuarial models described in previous articles on projections of expenditure (Arnett et al., 1986; Division of National Cost Estimates, 1987). It is actuarial in nature, relying on trend analysis rather than econometric fitting of dependent to independent variables, and consists of a series of identities, the factors of which are projected and reconciled.

The projections are based on historical estimates of NHE. Estimates of annual expenditure by type of service and by source of funds comprise the overall framework within which the model operates. The scenario we present was developed using historical figures through 1989 (Lazenby and Letsch, 1990); elsewhere in this issue, colleagues present updated figures for the last several years, along with a preliminary figure for 1990 (Levit et al., 1991b). To the extent that these newer figures differ from those used to prepare our projections, particularly for professional services, the level of the projected expenditures (especially in 1991) may not be strictly comparable with the newest history, but the longrun trends we discuss are not significantly affected by the revisions.

The projection scenario incorporates several exogenous factors. As already mentioned, it is tied to the assumptions and conclusions of the Medicare trustees' reports for 1991. Projected values of hospital insurance and supplementary medical insurance benefits are built into the projection model.

Similarly, the scenario takes as given the macroeconomic assumptions used to prepare the Medicare and Social Security trust fund reports. Those reports contain three different sets of assumptions: optimistic, intermediate, and pessimistic. We used Alternative II assumptions (the intermediate scenario) to prepare our projections. In theory, differential growth of health care spending should affect macroeconomic activity as well as sector-specific activity, but at present, the former effects are not explicitly modeled. We are working to incorporate the projection model with a model of the general macroeconomy, but results of that effort are not yet available. However, because our scenario assumes the continuation of current practices and mechanisms, we expect that the projection results are quite consistent with what would have resulted from a fully integrated model.

In addition to exogenous macroeconomic assumptions, our model incorporates projections of provider manpower. Projections of the number of physicians and dentists made by the Health Resources and Services Administration (Bureau of Health Professions, 1990) have been used when projecting expenditures for the services of those professionals.

As mentioned earlier, the model used for our projections consists of a series of identity equations. The typical equation consists of seven factors that describe expenditure for a good or service:

where the factors are defined as follows:

Pop—This is the number of people in the United States as of July 1. Projections are made by Social Security Administration actuaries and are exogenous to the model (Board of Trustees of the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Trust Fund, 1991).

PGNP—This represents the GNP implicit price deflator, which is a measure of economywide price inflation. It is exogenous to the model, having been projected by the Social Security and Medicare trustees (Board of Trustees of the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Trust Fund, 1991).

—This measure compares the price of the health good or service to general inflation, that is, it reflects sector-specific price inflation. It captures demand-pull inflationary pressures such as changes in income or insurance status. It also captures supply-push factors such as differential productivity and wage growth and provider-pricing strategies.

Ua—This is a factor that reflects the effect of the age-sex composition of the population on use of that good or service. For example, as the proportion of the population 75 years of age or over increases, we can expect to see greater use of nursing home care, even in the absence of any other changes. The construction of this factor, which is exogenous, has been described elsewhere (Arnett et al., 1986).

—This factor captures use per capita other than that generated by demographics. The specific measure varies by type of service. For example, inpatient days are used to project hospital inpatient expenditure, and outpatient visits are used to project hospital outpatient expenditure.

Ra—This term captures the effect of the age-sex composition of the population on the intensity of service, that is, on expenditures per unit of use, net of price effects. As with the term “Ua,” this factor is exogenous, and its construction is similar to that of the age-sex use factor as well.

—This term is a residual. It reflects intensity net of age and sex effects and might be called “real expenditure per unit of service.” It incorporates the effects of changes in technology and in the mix of procedures performed during the unit of service. It also reflects changes in regulations or policies that affect the quantity and quality of resources used to produce a unit of service. Like any residual, this term also reflects the accumulation of measurement errors, as well as the effects of all other factors not specifically or implicitly identified elsewhere.

Macroeconomic and other exogenous assumptions

The economy

The U.S. economic outlook to the year 2000 is characterized by low inflation and modest growth rates in real output (Table 1). The economy is projected to recover from its recession in mid-1991, with real GNP growth increasing from −0.1 percent in 1991 to 3.1 percent in 1992. Real growth rates then eventually stabilize at about 2.2 percent in the second half of the decade. Price inflation (measured by the implicit price deflator for GNP) falls from 4.1 percent in 1990 to 3.5 percent in 1991, before rising gradually to 4.0 percent in 1996 and thereafter. Nominal (current-dollar) GNP therefore reaches a steady 6.2-percent growth rate after the economy recovers from the current business cycle.

Table 1. Macroeconomic assumptions used to project national health expenditures: Selected years 1965-2000.

| Year | Gross national product | Population in thousands | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Current dollars in billions | 1982 dollars in billions | Implicit price deflator | Total | 65 years of age or over | 75 years of age or over | |

| Historical | ||||||

| 1965 | $705 | $2,088 | 33.8 | 203,990 | 19,068 | 6,904 |

| 1975 | 1,598 | 2,695 | 59.3 | 224,653 | 23,228 | 9,103 |

| 1980 | 2,732 | 3,187 | 85.7 | 235,252 | 26,125 | 10,413 |

| 1985 | 4,015 | 3,619 | 110.9 | 247,166 | 29,023 | 11,972 |

| 1989 | 5,201 | 4,118 | 126.3 | 256,995 | 31,415 | 13,205 |

| Projections | ||||||

| 1990 | 5,463 | 4,156 | 131.5 | 259,573 | 31,995 | 13,516 |

| 1991 | 5,650 | 4,152 | 136.1 | 262,102 | 32,527 | 13,827 |

| 1992 | 6,045 | 4,282 | 141.2 | 264,630 | 33,039 | 14,156 |

| 1995 | 7,284 | 4,598 | 158.4 | 271,975 | 34,402 | 15,187 |

| 2000 | 9,865 | 5,118 | 192.7 | 282,889 | 35,682 | 17,035 |

SOURCE: Board of Trustees of the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability trust funds: The 1991 annual report of the board, pursuant to section 201 (c)(2) of the Social Security Act as amended. Social Security Administration, May 1991.

The slower growth of real output parallels forecasts of slower civilian labor force growth in the 1990s, as the rate of growth of the working-age population falls and the labor force participation rate (which has increased steadily since the 1960s) levels off. For the 1990s, our projections incorporate average real GNP growth of 2.1 percent, as opposed to 2.7 percent in the 1980s and 2.8 percent in the 1970s. Similarly, inflation in the 1990s will average 3.9 percent, compared with 4.4 percent in the 1980s and 7.4 percent in the 1970s.

Demographic change

The total U.S. population is projected to increase about 0.9 percent per year in the 1990s, slowing slightly from the 1.0-percent rate in the 1980s (derived from Table 1). Social Security Administration actuaries project that the population 65 years of age or over will increase 1.1 percent per year and that the population 75 years of age or over will increase 2.3 percent per year in the 1990s (Board of Trustees of the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Trust Fund, 1991).

The aging of the population is frequently cited as a major factor in the growth of health care expenditures, but such is not yet the case. Although it is true that changes in demographics will have an effect on spending, the impact is relatively small during the projection period. People 65 years of age or over spend an average of four times as much on health care as do those under the age of 65 (Waldo et al., 1989), but the proportion of the population 65 or over is projected to increase only slightly during the 1990s, from 12.3 percent in 1990 to 12.6 percent in 2000. Using age-sex indexes described in a previous article (Arnett et al., 1986), we estimate that changes in the age-sex composition of the population will contribute only 4.6 percent to the 147-percent increase in total personal health care expenditures from 1990 to 2000.

The biggest influence of demographic change will not occur until well into the next century, when the baby boom generation enters the cohorts of 65 years of age and over. After 2015, the aged proportion of the population increases rapidly, reaching 20.4 percent by 2030.

Although the contribution of demographic change to total growth during the next 10 years is small, the impact is not uniform across all services (Table 2). The age-sex factor adds only about one-half of 1 percent per year to the use of inpatient hospital services and actually has a negative effect on the growth in intensity (cost per day is lower for aged patients). The impact on physician expenditures is also small, adding only 0.2 percent a year to its growth. However, an increase in the 1990s of the proportion of the population that is 75 years of age or over has a fairly large effect on the services used by the very old, primarily nursing home and home health services. The age-sex factors add 1.3 percent to the average annual growth of these services during the period.

Table 2. Effects of the age-sex composition of the population on growth in personal health care expenditures, between 1990 and 2000, by selected type of service.

| Percent difference | |

|---|---|

| Personal health care | 4.6 |

| Hospital inpatient care | 5.1 |

| Hospital outpatient care | 2.2 |

| Physician services | 2.3 |

| Dentist services | 1.2 |

| Other professional services | 12.6 |

| Home health care | 21.4 |

| Drugs and medical non-durables | 4.8 |

| Nursing home care | 13.4 |

NOTE: Figures reflect how much higher expenditure is projected to be in the year 2000 than it would have been in the absence of demographic change in the population after 1990.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Health professions manpower

Our model incorporates exogenous estimates of health manpower made by the Public Health Service (Table 3).

Table 3. Historical estimates and projections of the number of active physicians and dentists as of December 31: Selected years 1965-2000.

| Year | Active physicians | Dentists | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total | Medical doctors | Doctors of osteopathy | ||

| Historical | ||||

| 1965 | 288,700 | 277,600 | 11,100 | 95,990 |

| 1975 | 384,400 | 370,400 | 14,000 | 112,450 |

| 1980 | 457,500 | 440,400 | 17,100 | 126,200 |

| 1985 | 534,457 | 512,849 | 21,608 | 140,700 |

| 1989 | 587,454 | 560,937 | 26,517 | 148,300 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1990 | 601,060 | 573,310 | 27,750 | 149,700 |

| 1991 | 614,300 | 585,400 | 28,900 | 152,000 |

| 1992 | 627,300 | 597,200 | 30,100 | 152,000 |

| 1995 | 664,700 | 631,100 | 33,600 | 154,000 |

| 2000 | 721,600 | 682,120 | 39,480 | 154,600 |

SOURCE: (Bureau of Health Professions, 1990); unpublished data from the Bureau of Health Professions: Data developed by the authors.

The rate of growth in the number of physicians will slow in the 1990s but will remain considerably above the rate of population growth. Thus, the number of physicians per person will continue to increase in the next decade (Table 3).

The rate of growth of the number of practicing dentists fell considerably in the late 1980s, and Public Health Service analysts expect that decline to continue in the 1990s. The number of dentists per capita will begin falling in the early 1990s, although the absolute number of active dentists will actually peak just before the year 2000 before declining (Bureau of Health Professions, 1990).

Projection results: Types of service

National health expenditures

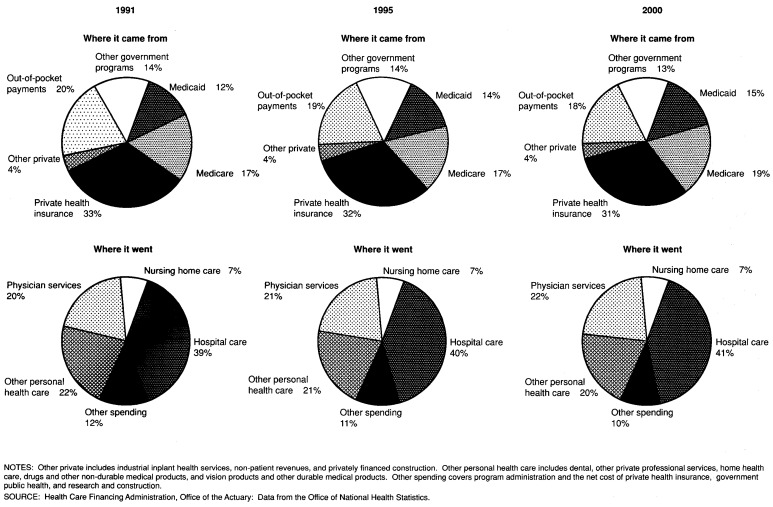

With the impetus imparted by current laws and practices, NHE will rise to $1.6 trillion in the year 2000, an amount equal to 16.4 percent of that year's GNP (Figure 1). The projected percentage of GNP accounted for by health spending at the end of the century is higher than the 15.0 percent figure reported in the most recent of a series of projections articles produced by the Health Care Financing Administration (Division of National Cost Estimates, 1987). In part, this reflects a higher level of projected health expenditures: The $1.6 trillion is 5.5 percent higher than our projection made 4 years ago. In addition, the projected GNP incorporated in this model is 3 percent lower than our previous projections.

Figure 1. Percent change in national health expenditures (NHE) and gross national product (GNP), and NHE as a percent of GNP: 1966-89 and projections 1990-2000.

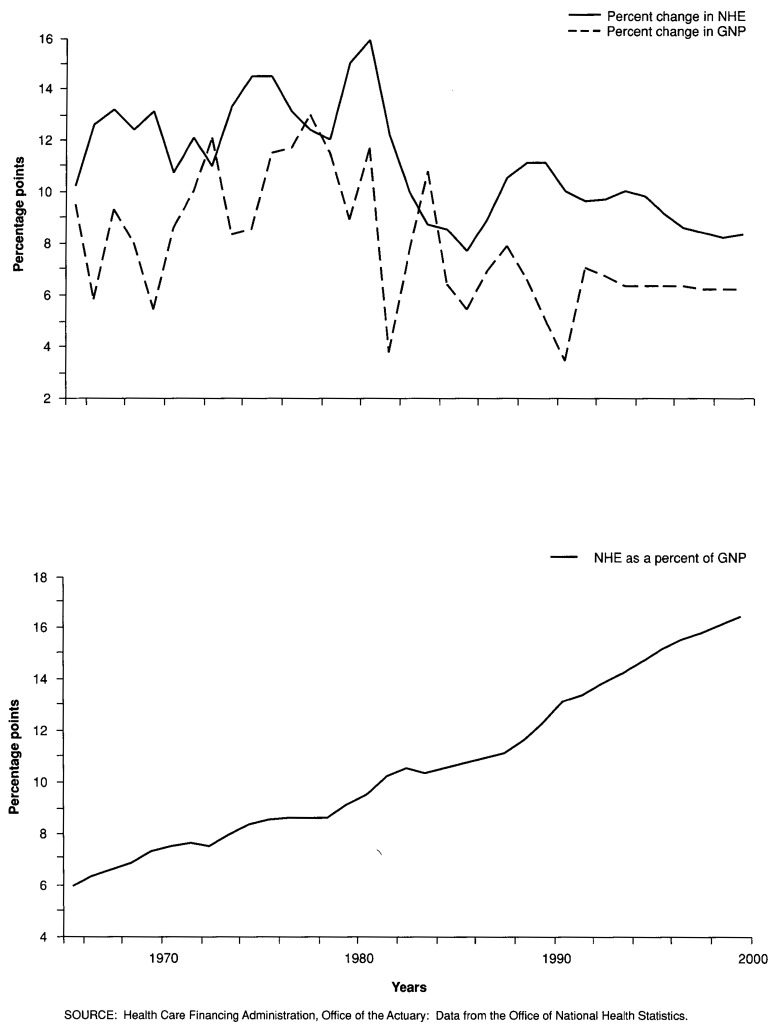

During the 1990s, an increasing share of NHE will be spent for hospital and physician services (Figure 2). Driven by that shift, Medicare and Medicaid will account for an increasing share of total spending as well, because the bulk of Medicare expenditures, and almost one-half of Medicaid's, are devoted to those services.

Figure 2. The Nation's health dollar—sources and destinations: 1991, 1995, and 2000.

NHE is projected to increase at an average rate of 9.2 percent from 1990 to 2000, reflecting changes in prices, population, and consumption per capita (Table 4). The overall growth rate is lower than the 12.8-percent average for the 1970s and the 10.4-percent average for the 1980s, mostly because of a projected abatement of price inflation.

Table 4. Average annual growth of nominal and real national health expenditures (NHE) and gross national product (GNP), of implicit price deflators for NHE and GNP, and of the opportunity cost of NHE: Selected periods, 1965-2000.

| Period | National health expenditures | Gross national product | Non-health care GNP price deflator | Opportunity cost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Nominal | Real | Price | Nominal | Real | Price | |||

| Average annual growth | ||||||||

| 1965-70 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 7.5 |

| 1970-75 | 12.3 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 9.5 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 4.8 |

| 1975-80 | 13.4 | 4.3 | 8.7 | 11.3 | 3.4 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 5.4 |

| 1980-85 | 11.0 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.7 |

| 1985-90 | 9.8 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 6.5 |

| 1990-95 | 9.8 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 6.1 |

| 1995-00 | 8.5 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| 1965-75 | 12.3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.2 |

| 1975-85 | 12.2 | 3.8 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 3.0 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 5.5 |

| 1985-95 | 9.8 | 4.2 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 6.3 |

| 1970-80 | 12.8 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 2.8 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 5.1 |

| 1980-90 | 10.4 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 6.1 |

| 1990-00 | 9.2 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Average annual growth per capita | ||||||||

| 1965-70 | 11.2 | 5.6 | — | 6.5 | 1.9 | — | — | 6.4 |

| 1970-75 | 11.3 | 4.4 | — | 8.5 | 1.3 | — | — | 3.8 |

| 1975-80 | 12.3 | 3.3 | — | 10.3 | 2.5 | — | — | 4.5 |

| 1980-85 | 9.9 | 2.3 | — | 6.9 | 1.6 | — | — | 4.6 |

| 1985-90 | 8.7 | 3.0 | — | 5.3 | 1.8 | — | — | 5.4 |

| 1990-95 | 8.8 | 3.4 | — | 4.9 | 1.1 | — | — | 5.1 |

| 1995-00 | 7.7 | 2.5 | — | 5.4 | 1.4 | — | — | 3.8 |

| 1965-75 | 11.2 | 5.0 | — | 7.5 | 1.6 | — | — | 5.1 |

| 1975-85 | 11.1 | 2.8 | — | 8.6 | 2.0 | — | — | 4.5 |

| 1985-95 | 8.8 | 3.2 | — | 5.1 | 1.4 | — | — | 5.3 |

| 1970-80 | 11.8 | 3.8 | — | 9.4 | 1.9 | — | — | 4.2 |

| 1980-90 | 9.3 | 2.7 | — | 6.1 | 1.7 | — | — | 5.0 |

| 1990-00 | 8.3 | 3.0 | — | 5.2 | 1.2 | — | — | 4.5 |

NOTE: Opportunity cost is defined to be nominal national health expenditures divided by the implicit price deflator for non-health gross national product.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

In real terms, NHE growth during the last decade of the century is projected to be close to that of the 1980s, at least in aggregate. “Real NHE” is found by stripping individual service components (hospital care, physician services, etc.) of their own price inflation and summing the resulting figures. Measured thus, it follows that change in real NHE per capita reflects change in “quantity” per capita (an amalgamation of contacts per person and intensity per contact). We project real NHE growth to average 3.8 percent per year from 1990 to 2000, compared with an average rate of 4.8 percent in the 1970s and 3.7 percent in the 1980s. Real growth will vary by type of service, and those variations are discussed later in this article.

We have projected slower health price inflation during the 1990s than had been the case in previous decades. The implicit deflator for health, defined as the ratio of nominal and real NHE, measures price inflation and shifts in use between high-price and low-price services. In our scenario, this deflator increases at an average rate of 5.2 percent between 1990 and 2000; the comparable figures for the 1970s and the 1980s were 7.7 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively. As with real growth, price inflation is projected to vary by type of good or service under consideration.

Using the growth rates just discussed, one may conclude that about one-third of the growth in NHE per capita between now and the end of the century will be attributable to quantity changes and the remainder to price inflation. Population growth will average 0.9 percent per year, a rate very close to that of the 1970s and 1980s. The balance between real growth and price inflation is also similar to that posted for those decades.

In addition to examining growth in nominal and real NHE, it is useful to look at changes in the real opportunity cost of that expenditure. Recall that changes in real NHE reflect changes in the amounts and intensity of health goods and services purchased. The real opportunity cost of expenditure measures the flip side of that coin: the amount of non-health goods and services that the Nation could have purchased with the dollars spent on health care. This measure is found by dividing nominal health care expenditure by the implicit price deflator for non-health GNP, and it is projected to grow 5.3 percent per year between 1990 and 2000. Put in other words, the Nation is projected to spend enough in the 1990s to increase its consumption of health goods and services 3.8 percent per year (real NHE). However, the size of the bundle of non-health goods and services that it could have purchased instead (real opportunity cost) is projected to increase 5.3 percent per year. This rate is similar to the 5.1-percent rate of the 1970s and lower than the 6.1-percent rate of the 1980s.

Personal health care expenditures

Assuming the continued influence of current laws and practices, expenditures for personal health care are projected to reach $957 billion in 1995 and $1,456 trillion in 2000. Personal health care expenditures (PHCE) comprise spending for those goods and services used to treat individual patients. PHCE excludes administration expenses, research, construction, and other types of spending that are not directed at patient care. The dollar values mentioned above imply an average annual growth rate of 9.5 percent during the 1990s, compared with 12.9 percent in the 1970s and 10.4 percent in the 1980s.

Our scenario shows a slight shift in the composition of spending for personal health care toward ambulatory services and away from inpatient care (Table 5). In 1990, community hospital outpatient revenues accounted for 8.7 percent of PHCE, and spending for physician services accounted for another 22.5 percent. By the end of the century, we project that hospital outpatient care will account for 12.8 percent of PHCE, and physician services will account for 24.8 percent. During the same period of time, other hospital revenues (including non-patient revenues) will decline as a share of total spending, from 35.0 percent in 1990 to 32.1 percent in 2000. Driven by demographic pressures, spending for nursing home care, home health services, and other professional services will maintain their respective shares of the total.

Table 5. Percent distribution of personal health care expenditures, by type of service: Selected years 1980-2000.

| Type of expenditure | 1980 | 1985 | Projected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | |||

|

| |||||

| Percent distribution | |||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital care | 46.9 | 45.7 | 43.7 | 44.5 | 44.9 |

| Community inpatient revenue | 31.7 | 30.8 | 28.1 | 26.5 | 26.3 |

| Community outpatient revenue | 4.8 | 6.3 | 8.7 | 11.4 | 12.8 |

| Other hospital care | 10.5 | 8.7 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 5.9 |

| Physician services | 19.2 | 20.1 | 22.5 | 23.6 | 24.8 |

| Dental services | 6.6 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

| Other professional services | 4.0 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| Home health care | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 9.2 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 6.3 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Nursing home care | 9.2 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Other personal health care | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

NOTES: Columns may not add to totals because of rounding. Non-patient revenues of community hospitals are included in “other hospital care.”

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Reflecting the growth of spending for physician services, we also project a strong shift toward government financing of PHCE. Medicaid's share of the total will grow from 12.1 percent in 1990 to 16.1 percent in 2000, a trend that is visible across the spectrum of services. Medicare will also increase in importance, especially in its role of paying for physician services. During the 1990s, the private share of PHCE will shrink from 59.1 percent to 53.6 percent, reflecting the increased share accounted for by government programs.

To understand the trends in consumption and financing of personal health care, it is important to study the individual types of goods and services that comprise the total. The following sections contain a discussion of the major components of expenditures.

Hospital care

We project that expenditures for hospital care will reach $425 billion in 1995 and $654 billion at the end of the century. Average annual growth slightly faster than that of the rest of NHE results in hospital care consuming a larger share of the NHE pie in the year 2000: 40.5 percent of the total compared with 38.5 percent in 1989. During the course of the decade to come, current laws and practices suggest that government programs, especially Medicaid, will finance a larger share of total hospital spending than had been the case in the past. Out-of-pocket expenditures and private health insurance benefits will decline as a percent of the total.

In making our projections of hospital expenditure, we divided that category into five parts. Two parts reflect the inpatient and outpatient revenue of community hospitals—short-term, non-Federal hospitals open to the public, which account for three-quarters of all hospital beds. (The other parts, which reflect activity in non-community hospitals and in Federal hospitals, and community hospital non-patient revenues, are not discussed in detail here.)

Community hospital inpatient revenue

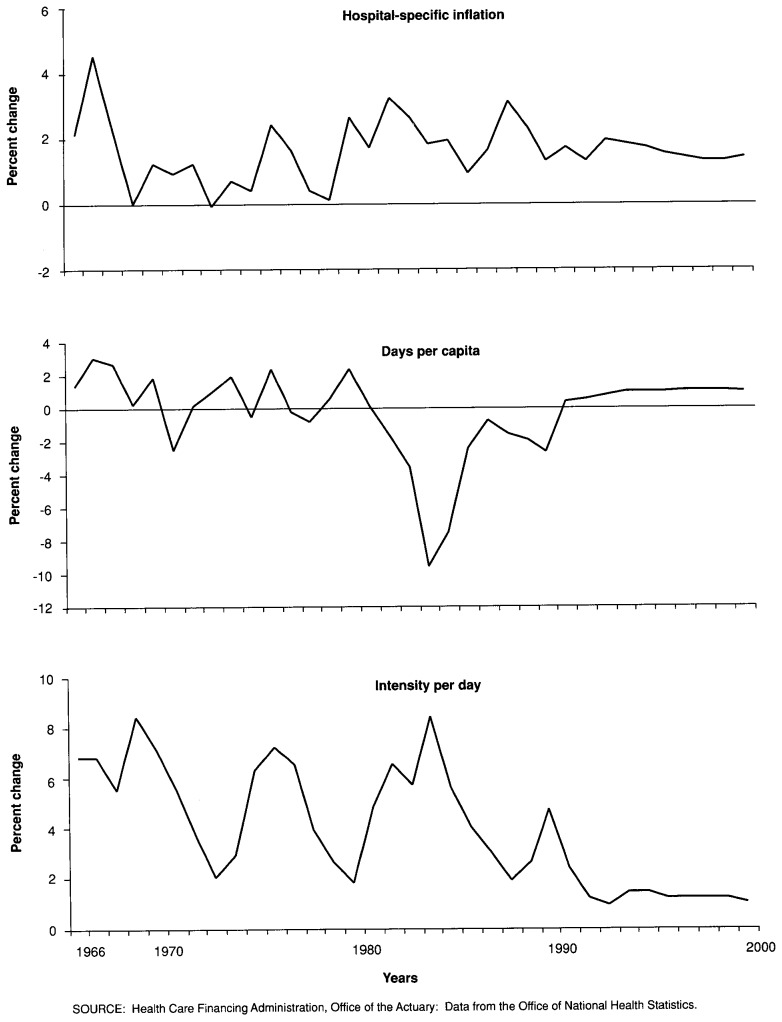

Between 1990 and 2000, inpatient revenue of community hospitals is projected to grow at a rate slightly faster than that seen during the previous decade. This roughly similar growth is the result of offsetting changes in the growth of inpatient days and of inpatient intensity, as the relative price of care is projected to grow at rates comparable to those of the past decade (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Annual change in use, intensity, and deflated price of expenditures for community hospital inpatient services: 1966-2000.

Medicare's prospective payment system (PPS) and concurrent private and government cost-reduction measures had a profound effect on the growth of community hospital inpatient revenues after 1980. Annual growth of revenues decelerated rapidly between 1980 and 1985, from a high of 18 percent to a low of 4 percent. The average annual rate for the period was 10.3 percent. After 1985, nominal growth rates accelerated, reaching 8.7 percent in 1990, but even that rate was scarcely one-half the average posted prior to 1980. Our projection is that growth will change very little through the end of the century.

A substantial part of the growth in inpatient revenue will continue to be general price inflation, but the decline in inpatient days per capita will reverse itself. Change in the GNP deflator has accounted for about one-half of the growth in inpatient revenue since 1980 and is projected to continue to do so in the future. The differential between hospital prices and prices in general is projected to stay at roughly historical levels as well. However, we project that the 9-year decline in inpatient days per capita will be reversed beginning in 1991. Medicare actuaries predict strong growth in days of care for people 65 years of age or over, as the industry completes its adjustment to PPS. Aging of the elderly population should contribute between one-quarter and one-half of 1 percent per year to growth throughout the decade. The growth of days per capita for the population under the age of 65 is projected to begin midway through the decade. That annual growth will be boosted by an age-sex factor the contribution of which rises from one-quarter of 1 percent per year early in the decade to three-quarters of 1 percent per year by decade end.

At the same time that growth in days per capita accelerates, growth in inpatient intensity decelerates. During the last 25 years, there has been a gradual (if intermittent) deceleration of growth in this factor, and that trend is projected to continue into the next decade.

Community hospital outpatient revenue

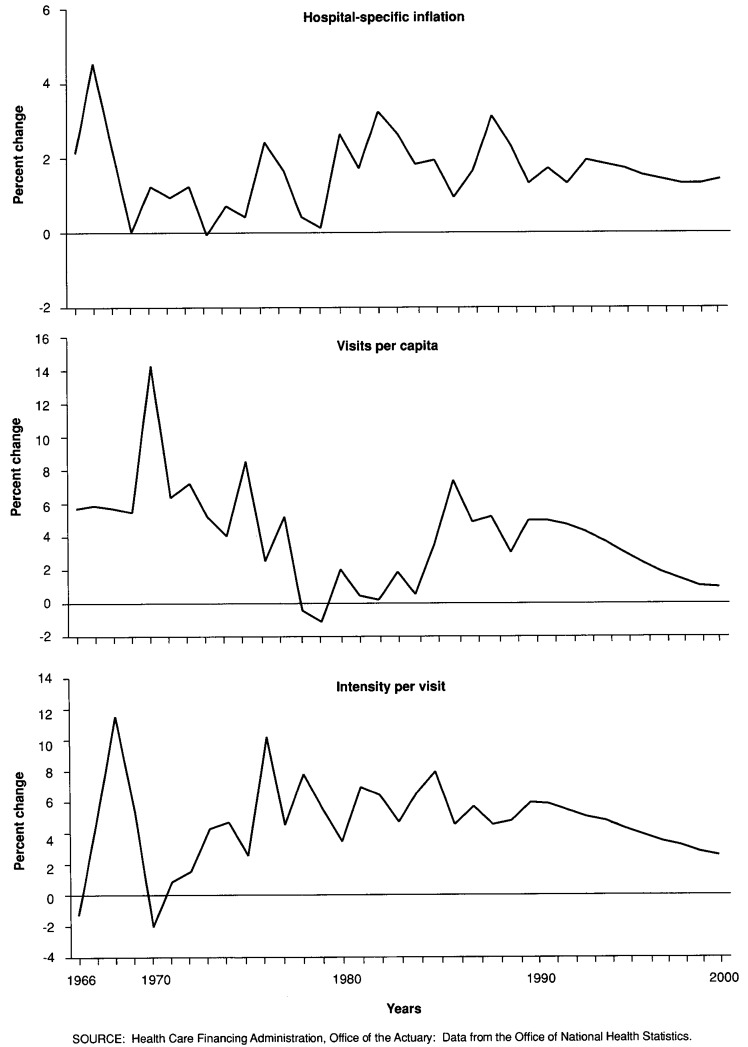

Growth of community hospital outpatient revenue is projected to continue to subside over the next 10 years. That decline in growth can be traced to both use of outpatient services and the intensity of that use (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Annual change in use, intensity, and deflated price of expenditures for community hospital outpatient services: 1966-2000.

Just as PPS and other hospital cost-reduction measures affected use of inpatient services in the mid-1980s, they affected use of outpatient services as well. Throughout the 1970s, the number of outpatient visits per capita had been growing, but the rate of change had dropped steadily, stabilizing at about 1 percent per year in the early 1980s. The introduction of inpatient cost containment resulted in a surge in outpatient visits beginning in 1985, as hospitals responded to changed incentives by shifting much pre-admission testing and many procedures to an outpatient setting. The rate of growth began to decline again after 1986 and is projected to continue to decline through the end of the century, reaching an annual rate of 1 percent by the year 2000.

We also project that outpatient intensity will grow at diminishing rates over the next 10 years. The previous 25 years have been characterized by accelerating growth in intensity, although the rate of acceleration dropped to or below zero in the mid- to late 1980s. We have projected a deceleration in the 1990s, tapering the growth of intensity to just over 2 percent per year by the end of the decade.

In the absence of a good time-series price for outpatient services, we have used the same price measure as for inpatient services. Any differential price changes will be reflected in the outpatient intensity measure already discussed. About one-half of the growth in community hospital outpatient revenues is attributable to price inflation, mostly general inflation. Growth in use and intensity, which is strong relative to growth of inpatient services, accounts for most of the rest of nominal expenditure growth.

Physician services

National spending for physician services is projected to be $226 billion by 1995 and $360 billion by the year 2000. This growth rate for the 1990s is slightly slower than in the 1970s or 1980s.

General price inflation accounts for slightly more than one-third of the projected increase in physician spending over the next 10 years. The prices that physicians charge in excess of the general inflation rate are expected to comprise less than one-tenth of the growth in the next decade, in part because Medicare is forecasting only slow growth in its allowable fees.

Demographic factors play a fairly small role in our projection of physician expenditures. Population change itself will account for less than one-tenth of the projected growth. The aging of the population does not add much to the use or intensity of physician services, partly because the baby boom does not mature into the higher use ages until the next century and partly because the increase in utilization with age is not as dramatic in the case of physician services as it is for hospitals and nursing homes.

Aside from price inflation, most of the growth in expenditures for physician services has been in intensity. Use of physician services, as measured by office and hospital visits, has changed little in the past two decades, and, in our projections, it grows only slowly in the future. Such is not the case with intensity. Intensity measures the increase in the number and quality of such items as lab tests, radiology for diagnosis and treatment, more complex operative procedures, etc. It has risen steadily in the past and is projected to constitute about one-third of the growth in spending for physician services by 2000.

Nursing home care

Nursing homes included in this projection consist of skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, a large number of homes with both certifications, some homes with neither certification, and some intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded (ICF/MR). (Certification levels refer to Medicare or Medicaid certification.) Expenditure for this type of care is projected to reach $86 billion in 1995 and $131 billion in 2000.

We project that use of nursing home services will continue to grow less than would be predicted by age-sex-specific use patterns. In part, this is attributable to a bed supply that has grown less rapidly than has the population most at risk. It also is attributable to a trend toward deinstitutionalization of ICF/MR patients. And, in part, it is attributable to a preference on the part of patients and payers for alternative modes of long-term care that are both economical and acceptable to users.

Medicaid pays and will continue to pay about 45 percent of the costs of nursing homes. Approximately another 45 percent is paid directly by the patient or the patient's family. The remaining costs are spread among several payers. Of great interest is whether private insurance in either its present form or some modification will meet a significant portion of the cost in the 1990s, helping some private payers budget for these costs and providing relief for the public programs.

Drugs and other non-durable goods

Total expenditures for drugs and sundries have grown at remarkably stable rates over the last 25 years—average annual growth rates of drug expenditures for 5-year periods from 1965 to 1990 have not been lower than 8.1 percent nor higher than 10 percent. Yet this stability masks some dramatic changes in the composition of that expenditure—price increases as opposed to quantity increases.

Prescription drug prices have followed a different pattern than have prices in general. They fell uniformly from the 1960s through the mid-1970s relative to overall price levels in the economy. From the mid-1970s through 1981, they grew at about the same rate as overall prices, and since then they have grown much more rapidly than have general prices.

The pattern for prescription quantity (expenditures adjusted for price change) is the mirror image of that for price, but less pronounced. During the 1960s and early 1970s, volume increased significantly more rapidly than real GNP. Real spending grew more slowly than did real GNP beginning as early as the late 1970s and especially after 1982.

During the 1990s, we project that relative price inflation will account for less of the growth in expenditure for drugs and non-durable goods than has been the case since the early 1980s. Growth of the relative price of goods in this category will slow during the 1990s from 4 percent in 1990 to 1 percent in 2000. Real spending per capita, although continuing to fall, will do so at diminishing rates and will in fact begin to grow slightly by the end of the decade.

Other categories of personal health care

Dentist services

Expenditures for dentist services are expected to be $63 billion in 2000, up from $31 billion in 1989. We project an average annual growth rate for dentist expenditures of 6.4 percent in the 1990s, down from 8.9 percent in the 1980s and 11.9 percent in the 1970s. This reduced rate of growth in the 1990s reflects a forecast of prices increasing 1.8 percent per year faster than the general inflation rate, and slightly negative growth in real (inflation-adjusted) per capita services. The projected number of practicing dentists will peak in 1999 and actually decline slightly in 2000.

It is widely assumed that past increases in private health insurance coverage of dental services have supported higher dental expenditures despite advances in preventive dental care. We project private health insurance to finance a smaller share of total dental expenditures in the 1990s, reversing the trend toward increasing insurance expenditure shares from 1965 to the present.

Home health care

In our scenario for the 1990s, recent rapid increases in Medicaid spending for home health care are projected to continue, only slightly abated, through the coming decade. Medicaid spending for home health care was almost $2 billion in 1989 and is projected to reach $5.1 billion in 1995 and $9.7 billion in 2000. State Medicaid programs have been using additional flexibility granted by Congress to attempt to meet the demand for long-term care services that, in the past, have been provided almost exclusively by nursing homes under the Medicaid program. It was intended that the additional flexibility in designing long-term care solutions would result in cost savings and also more satisfactory programs for the aged and disabled who depend on Medicaid for their long-term care needs.

Medicare is anticipating continued growth in its home health outlays at a slower rate than Medicaid. The Medicare benefit is closely circumscribed to be an acute care benefit intended to substitute for more expensive acute institutional care in hospitals and skilled nursing facilities.

Most surveys have noted a very large demand for home health care, some of it met by public or private financial resources, much of it met by volunteers, and some of it not met at all. Most of that care is used by the very elderly, and some pressure on spending is already being exerted by aging cohorts born at the beginning of this century.

Other professional services

Expenditure growth rates for other professional services are projected to remain moderate in the 1990s. “Other professional services” covers spending for services of licensed health practitioners other than physicians and dentists and expenditures for services rendered in outpatient clinics. Expenditures had increased more than 19 percent per year in the 1970s, a rate of increase that slowed to 13.5 percent per year in the 1980s. We project annual growth rates of 9.4 percent for spending in the 1990s, reflecting price increases of 1.5 percent over the general inflation rate and real expenditure per capita growth of almost 3 percent. Total expenditures for other professional services will reach $75 billion in 2000, up from 27 billion in 1989.

Private health insurance coverage for other professional services is expected to moderate in the 1990s. As a result of this and rapid growth in government programs, total spending financed by insurance will peak at about 38 percent early in the decade and fall to less than 35 percent by 2000.

Eyeglasses and other durable goods

Expenditures for this class of goods have grown at double-digit rates since the end of the 1982 recession. These high growth rates were driven largely by rapid increases in real spending. In fact, prices seem to have grown slightly less than the GNP deflator in the 1980s. Our projection shows continued strong growth in real spending, but the rates of growth are moderated somewhat from historical rates. Prices are assumed to grow at the rate of general economy prices, so that expenditure grows roughly 1 percent faster than GNP.

Spending for durables has a consistent cyclical pattern, following the economy's business cycles. Thus, spending will be restrained in 1991 and will recover as the economy is predicted to recover in the mid- and late 1990s.

Other personal health care

The category labeled “other personal health care” in the tables presented in this article consists of items not definable in the usual categories or not specified by kind by the reporting agency. Much of the spending is financed by government, Medicaid being the largest payer. Total expenditures will reach almost $34 billion in 2000, up from $10.5 billion in 1989. Spending in this category continues to increase more rapidly than GNP, as Medicaid expenditure growth remains very high in the 1990s.

Research and construction

Expenditures for biomedical research and research on the delivery of health care will increase at roughly the same rate as GNP in the 1990s, reaching $22.3 billion in 2000. Construction spending will grow more slowly than GNP throughout much of the 1990s, and will reach $17.5 billion in 2000, up from $9.6 billion in 1989. To project construction, we first estimated the capital stock needed to supply our projected hospital and nursing home services; a key variable in the determination was the number of beds in service in the various institutions. We then projected the level of new construction needed to achieve that capital stock.

Projection results: Sources of funds

During the 1980s, the proportion of NHE funded by public and private sources stabilized, with the private sector paying just under 60 percent of the total. A gradual shift from private to public sources is projected for the next decade, reducing the private share to 53 percent by the year 2000.

Spending for Medicare and Medicaid, the two major sources of government financing for health, is projected to increase as a percent of the total. The Medicare increase is primarily the result of growth in the proportion of the population 65 years of age or over, especially the cohort 75 or over, which has the highest health care costs. The Medicaid share is projected to rise as a result of several factors, including expanded eligibility.

Government financing

Total Federal spending for health care is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 10.4 percent between 1990 and 2000, about the same rate as for the 1980s. We project that Federal expenditures will reach $517.6 billion by 2000 and finance 32 percent of NHE, up from 28.7 percent in 1990. Both the Medicare and Federal Medicaid share of total health spending will increase during the projection period; the share funded by other Federal sources, mainly the Departments of Veterans Affairs and of Defense, is projected to decline slightly.

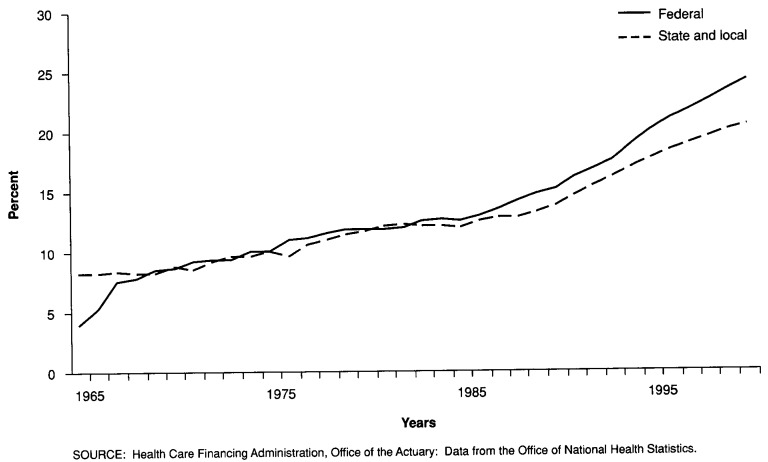

Although the growth in total Federal spending represents a small increase in the share of total health spending, it represents a sizable increase in the share of total Federal Government spending. In 1980, federally financed health expenditures accounted for 11.7 percent of Federal expenditures; in 1990, the share was 15.1 percent, and it is projected to account for 24.1 percent by the year 2000 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Government expenditures for health as a percent of total government expenditures: 1965-97.

State and local government expenditures for health care are also projected to rise both as a share of NHE and as a share of total State and local government spending. Driven primarily by projected increases in Medicaid spending, State and local government expenditures are projected to grow from $89.4 billion in 1990 to $238.9 billion in 2000. This results in an increase of 1.6 percent in the State and local share of NHE, and a 6.7-percent increase in health's share of their budget (Figure 5).

Medicare

Medicare's HI and SMI programs are projected to account for $182.3 billion of health expenditures in 1995 and for $302.8 billion in 2000. These sums represent an increasing share of total NHE: After remaining relatively stable between 16.5 percent and 17.0 percent of total spending through 1995, Medicare's share of total spending is projected to rise to 18.7 percent by the end of the decade.

Outlays for physician services will consume an increasing amount of Medicare payments. Accounting for 27.6 percent of the Medicare budget in 1990, these payments will rise to 32.6 percent by the year 2000.

Effective January 1, 1992, Medicare will begin paying physicians on the basis of a resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) that is intended to relate payment for any service to the effort, time, and skill required by the physician. The current payment system, based on the lowest of actual, customary, or prevailing fees, has its roots in the traditional charge patterns of physicians in each geographic area, but has been modified substantially by congressional actions over the past several years.

The RBRVS is intended to rationalize Medicare payment levels. To help control increases in utilization and intensity of services, a “volume standard” is promulgated annually. This volume standard is a target growth rate for aggregate Medicare spending on physician services. If physician spending in any year exceeds the target, Medicare will lower a future fee scale increase. If the spending target is exactly met, the fee scale would be increased by the Medicare Economic Index. A bonus fee increase can be paid if spending is less than the volume standard.

There is great interest in how effectively this new payment system will influence future trends in Medicare costs and whether it will affect other payers. During the last half of the 1980s, Medicare payments to physicians rose more than 13 percent per year on average, in spite of fee freezes in some years. In its most recent report, the Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund forecasts physician increases in excess of 10 percent per year through the year 2000 (Alternative II).

Medicare inpatient hospital costs, on the other hand, have increased much more slowly since PPS was instituted in fiscal year 1984. In the 5 years after 1984, Medicare inpatient payments increased less than 6 percent annually. In the 5 years ending with 1984, they increased more than 15 percent annually. The Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund projects Medicare hospital inpatient costs to increase about 10 percent annually through the year 2000 (Alternative II). These rates are somewhat higher than in the recent past. In part, this is because Medicare actuaries do not anticipate a continuation of the decreases in hospital use that occurred following PPS. In addition, laws reducing the increase in PPS hospital payment rates will expire in fiscal year 1993.

(For a more detailed discussion of Medicare projections, see the 1991 annual reports by the Board of Trustees of the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund [1991] and Board of Trustees of the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund [1991].)

Medicaid

Preliminary data indicate that Medicaid spending ballooned abruptly in 1990 following several years of much more modest growth rates. Following the 1982 recession, Medicaid grew less than 11 percent per year through 1989. It appears that 1990 costs were about 20 percent above those for 1989. Most spending for acute care services rose much more rapidly than in the recent past and there was sizable growth in home and community-based alternatives to long-term care.

As part of the Federal budget process, State Medicaid programs prepare quarterly estimates of what they expect to be spending in the current and next two fiscal years. These planning estimates indicate that State administrators are forecasting continued high growth through fiscal year 1992.

The reasons for this upturn in spending are not yet well understood, and thus it is difficult to foresee what it implies for the longer term. The current recession probably plays some role. Also, Congress has expanded eligibility somewhat in recent years. Providers in some States have brought successful court cases to increase reimbursement levels. In short, there are many plausible explanations, but so far a shortage of evidence to quantify the effects of most of them.

In light of this uncertainty, our projections follow a middle course. Aggregate Medicaid growth averages 15.5 percent per year through 1995, bringing outlays to $154.1 billion. During the last half of the decade, the average annual growth slows to 9.6 percent, so that spending in the year 2000 is projected to be $243.8 billion.

Private financing

Private expenditures for health care are projected to reach $859 billion by 2000, financing 53.2 percent of NHE. For the 1990-2000 period, private health expenditures are projected to grow at an average annual rate of 8.2 percent, slower than the 10.5-percent rate of the previous 10-year period, and slower than the projected rate of growth for total NHE.

Private health insurance premiums, which make up about one-third of NHE and 60 percent of total private funding, are projected to more than double in the next 10 years, from $222.5 billion to $507.7 billion. The proportion of personal health care paid for by private health insurance benefits is projected to decline slightly during this period, reversing the trend of the past 10 years, mostly as a result of more rapid relative growth in public payments.

Out-of-pocket payments for health care are projected to increase to $290.9 billion by the turn of the century. The out-of-pocket share of PHCE is projected to continue its decline from 26.8 percent in 1980, through 23.4 percent in 1990, to 20.0 percent by 2000.

Expenditures of other private funds (which include non-patient revenues of hospitals and nursing homes, spending for industrial inplant services, and so on) are projected to reach $61.6 billion by 2000 and account for 3.8 percent of all health spending, including research and construction.

During the past 25 years, there has been a continuous shift from out-of-pocket to private health insurance spending for personal health care. However, this shift is projected to slow during the projection period, resulting in an increase in the insurance share of NHE of only 2 percent, compared with its 5.2-percent share increase during the 1980s.

This projected slowing in the growth of private health insurance is the result of several factors: an increase in the number of uninsured and underinsured people because of the recent recession; the prohibitive cost of purchasing private health insurance by small employers and individuals; and reductions in retiree health care coverage as a result of the implementation of the Financial Accounting Standards Board regulations requiring employers to show future retiree health care costs as a liability on their financial statements.

There also is evidence that employers plan to require employees to pay higher deductibles and copayments and to reduce or eliminate supplemental benefits such as dental and prescription drug coverage in an attempt to control the escalating costs of providing health benefits to employees.

Summary

Health care expenditures have grown more rapidly than has the rest of the economy during the past 30 years, much of which is attributable to natural factors. Rising income levels, the introduction of new services and new technologies, and changes in the social and demographic composition of the population have all contributed to growth in spending for health. Reimbursement practices, perverse incentives created by the financing system, and market failures caused by lack of consumer information have played a part as well.

It is clear that at least some of these factors will continue to operate in the future. Real GNP per capita will continue to grow, although more slowly in the longrun than has been the case in the recent past. The aging of America's population will serve to raise the demand for health care, although the effect will be fairly trivial through the next 30 years. Also, there is no reason to doubt that new technologies and new services will continue to be introduced, although when and where is open to debate. Whether perverse incentives to consume care continue into the future is a policy issue to be resolved.

To assist that resolution, we have shown how health care spending would grow in the next 10 years under current law and current practices. Our scenario, however, is only one of an almost infinite number of different scenarios (some more plausible than others) describing the effects of current law and current practice. Each scenario embodies a different set of assumptions about the shape of things to come. For example, extension of our scenario through the year 2030 yields a level of NHE equal to 26.1 percent of the GNP. In testimony before Congress, the director of the Office of Management and Budget suggested that, in the absence of change, health care spending would reach 17 percent of GNP by 2000 and 37 percent by 2030. Even were we to reduce differential price growth to zero immediately and to permit combined use and intensity to grow no more rapidly than real GNP per capita, we would still have a health expenditure figure equal to 15 percent of the 2030 GNP.

Table 7. National health expenditures aggregate amounts and average annual percent change, by type of expenditure: Selected years 1965-2000.

| Type of expenditure | 1965 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1989 | Projected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $41.6 | $132.9 | $249.1 | $420.1 | $604.1 | $670.9 | $738.2 | $809.0 | $1,072.7 | $1,615.9 |

| Health services and supplies | 38.2 | 124.7 | 237.8 | 404.7 | 583.5 | 648.6 | 714.4 | 783.8 | 1,043.1 | 1,576.1 |

| Personal health care | 35.6 | 116.6 | 218.3 | 367.2 | 530.7 | 589.3 | 651.1 | 716.7 | 956.5 | 1,456.0 |

| Hospital care | 14.0 | 52.4 | 102.4 | 167.9 | 232.8 | 257.7 | 285.4 | 313.9 | 425.4 | 654.2 |

| Physican services | 8.2 | 23.3 | 41.9 | 74.0 | 117.6 | 132.7 | 148.5 | 165.5 | 225.6 | 360.5 |

| Dental services | 2.8 | 8.2 | 14.4 | 23.3 | 31.4 | 33.8 | 36.1 | 38.6 | 47.1 | 63.1 |

| Other professional services | 0.9 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 16.6 | 27.0 | 30.7 | 34.5 | 38.7 | 51.6 | 75.4 |

| Home health care | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 12.1 | 18.8 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 5.9 | 13.0 | 20.1 | 32.3 | 44.6 | 48.5 | 51.8 | 55.5 | 67.7 | 91.0 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 1.2 | 3.1 | 5.0 | 8.4 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 14.9 | 16.1 | 20.0 | 28.4 |

| Nursing home care | 1.7 | 9.9 | 20.0 | 34.1 | 47.9 | 53.6 | 59.1 | 64.9 | 85.8 | 130.8 |

| Other personal health care | 0.8 | 2.7 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 21.3 | 33.9 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 1.9 | 5.1 | 12.2 | 25.2 | 35.3 | 40.5 | 43.3 | 45.9 | 60.8 | 85.3 |

| Government public health activities | 0.6 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 17.5 | 18.8 | 20.0 | 21.2 | 25.8 | 34.8 |

| Research and construction | 3.5 | 8.3 | 11.3 | 15.4 | 20.6 | 22.3 | 23.8 | 25.2 | 29.6 | 39.8 |

| Research1 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 11.0 | 11.7 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 16.1 | 22.3 |

| Construction | 1.9 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 13.5 | 17.5 |

| Average annual percent change from previous year shown | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | — | 12.3 | 13.4 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 8.5 |

| Health services and supplies | — | 12.6 | 13.8 | 11.2 | 9.6 | 11.2 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 8.6 |

| Personal health care | — | 12.6 | 13.4 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 8.8 |

| Hospital care | — | 14.1 | 14.3 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 9.0 |

| Physician services | — | 11.0 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 9.8 |

| Dental services | — | 11.4 | 11.7 | 10.1 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.0 |

| Other professional services | — | 15.0 | 19.9 | 13.8 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 10.0 | 7.9 |

| Home health care | — | 21.4 | 27.2 | 23.3 | 8.7 | 21.4 | 14.7 | 13.7 | 12.5 | 9.2 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | — | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.1 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | — | 9.4 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| Nursing home care | — | 19.3 | 15.0 | 11.3 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 8.8 |

| Other personal health care | — | 12.6 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 11.3 | 10.1 | 15.4 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 9.7 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | — | 10.1 | 19.3 | 15.5 | 8.8 | 14.8 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 9.9 | 7.0 |

| Government public health activities | — | 17.0 | 18.9 | 11.3 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 6.2 |

| Research and construction | — | 9.1 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 6.1 |

| Research1 | — | 8.1 | 10.4 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.8 |

| Construction | — | 9.9 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 10.1 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 5.3 |

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

NOTE: Columns may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Table 8. National health expenditures, by source of funds and type of expenditure: Selected years 1980-2000.

| Year and type of expenditure | Total | Private | Government | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| All private funds | Consumer | Other | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Total | Out-of-Pocket | Private insurance | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

| 1980 | Amount in billions | ||||||||

| National health expenditures | $249.1 | $143.9 | $131.8 | $58.4 | $73.4 | $12.1 | $105.2 | $72.0 | $33.2 |

| Health services and supplies | 237.8 | 139.7 | 131.8 | 58.4 | 73.4 | 7.8 | 98.1 | 66.8 | 31.4 |

| Personal health care | 218.3 | 131.3 | 123.7 | 58.4 | 65.3 | 7.6 | 87.1 | 63.5 | 23.6 |

| Hospital care | 102.4 | 47.8 | 42.8 | 5.3 | 37.5 | 5.0 | 54.6 | 41.3 | 13.3 |

| Physician services | 41.9 | 29.2 | 29.2 | 11.3 | 18.0 | 0.0 | 12.6 | 9.7 | 3.0 |

| Dental services | 14.4 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 9.4 | 4.4 | — | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Other professional services | 8.7 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| Home health care | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 20.1 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 16.0 | 2.5 | — | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 5.0 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 0.4 | — | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Nursing home care | 20.0 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 10.5 | 6.1 | 4.4 |

| Other personal health care | 4.6 | 0.9 | — | — | — | 0.9 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 12.2 | 8.4 | 8.1 | — | 8.1 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Government public health activities | 7.2 | — | — | — | — | — | 7.2 | 1.2 | 6.0 |

| Research and construction | 11.3 | 4.2 | — | — | — | 4.2 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 |

| Research | 5.4 | 0.3 | — | — | — | 0.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 0.5 |

| Construction | 5.8 | 4.0 | — | — | — | 4.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Percent distribution | |||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 57.8 | 52.9 | 23.5 | 29.5 | 4.8 | 42.2 | 28.9 | 13.3 |

| Health services and supplies | 100.0 | 58.7 | 55.4 | 24.6 | 30.9 | 3.3 | 41.3 | 28.1 | 13.2 |

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 60.1 | 56.7 | 26.8 | 29.9 | 3.5 | 39.9 | 29.1 | 10.8 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 46.7 | 41.8 | 5.2 | 36.6 | 4.9 | 53.3 | 40.4 | 12.9 |

| Physician services | 100.0 | 69.8 | 69.8 | 26.9 | 42.9 | 0.1 | 30.2 | 23.1 | 7.1 |

| Dental services | 100.0 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 65.2 | 30.5 | — | 4.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Other professional services | 100.0 | 79.9 | 69.3 | 43.5 | 25.8 | 10.6 | 20.1 | 14.9 | 5.2 |

| Home health care | 100.0 | 27.6 | 17.7 | 10.2 | 7.6 | 9.9 | 72.3 | 61.3 | 11.0 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 100.0 | 91.8 | 91.8 | 79.4 | 12.4 | — | 8.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 100.0 | 87.8 | 87.8 | 78.9 | 8.9 | — | 12.2 | 10.3 | 1.9 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 47.3 | 44.2 | 43.3 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 52.7 | 30.7 | 21.9 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 19.1 | — | — | — | 19.1 | 80.9 | 54.7 | 26.2 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 100.0 | 68.6 | 66.6 | — | 66.6 | 2.0 | 31.4 | 16.9 | 14.5 |

| Government public health activities | 100.0 | — | — | — | — | — | 100.0 | 17.3 | 82.7 |

| Research and construction | 100.0 | 37.5 | — | — | — | 37.3 | 62.5 | 46.2 | 16.3 |

| Research | 100.0 | 5.0 | — | — | — | 5.5 | 95.0 | 85.4 | 9.6 |

| Construction | 100.0 | 67.8 | — | — | — | 68.6 | 32.2 | 9.6 | 22.6 |

| 1989 | Amount in billions | ||||||||

| National health expenditures | $604.1 | $350.9 | $324.5 | $124.8 | $199.7 | $26.3 | $253.3 | $174.4 | $78.8 |

| Health services and supplies | 583.5 | 342.7 | 324.5 | 124.8 | 199.7 | 18.2 | 240.8 | 164.8 | 76.1 |

| Personal health care | 530.7 | 315.3 | 297.7 | 124.8 | 172.9 | 17.6 | 215.4 | 158.4 | 57.0 |

| Hospital care | 232.8 | 108.3 | 96.9 | 12.7 | 84.2 | 11.4 | 124.5 | 92.9 | 31.6 |

| Physician services | 117.6 | 78.5 | 78.4 | 22.4 | 56.1 | 0.0 | 39.2 | 31.8 | 7.4 |

| Dental services | 31.4 | 30.7 | 30.7 | 17.2 | 13.4 | — | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Other professional services | 27.0 | 21.6 | 18.7 | 8.5 | 10.2 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 1.4 |

| Home health care | 5.4 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 0.9 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 44.6 | 39.3 | 39.3 | 32.3 | 7.0 | — | 5.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 13.5 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 1.2 | — | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.3 |

| Nursing home care | 47.9 | 22.7 | 21.8 | 21.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 25.2 | 16.2 | 9.0 |

| Other personal health care | 10.5 | 2.1 | — | — | — | 2.1 | 8.4 | 5.2 | 3.3 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 35.3 | 27.4 | 26.8 | — | 26.8 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Government public health activities | 17.5 | — | — | — | — | — | 17.5 | 2.1 | 15.4 |

| Research and construction | 20.6 | 8.2 | — | — | — | 8.2 | 12.4 | 9.7 | 2.8 |

| Research | 11.0 | 0.8 | — | — | — | 0.8 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 1.4 |

| Construction | 9.6 | 7.4 | — | — | — | 7.4 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| Percent distribution | |||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 58.1 | 53.7 | 20.7 | 33.1 | 4.4 | 41.9 | 28.9 | 13.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 100.0 | 58.7 | 55.6 | 21.4 | 34.2 | 3.1 | 41.3 | 28.2 | 13.0 |

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 59.4 | 56.1 | 23.5 | 32.6 | 3.3 | 40.6 | 29.8 | 10.7 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 46.5 | 41.6 | 5.5 | 36.2 | 4.9 | 53.5 | 39.9 | 13.6 |

| Physician services | 100.0 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 19.0 | 47.6 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 27.0 | 6.3 |

| Dental services | 100.0 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 54.9 | 42.7 | — | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Other professional services | 100.0 | 79.8 | 69.2 | 31.5 | 37.7 | 10.6 | 20.2 | 15.2 | 5.0 |

| Home health care | 100.0 | 24.4 | 18.2 | 11.4 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 75.6 | 58.3 | 17.2 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 100.0 | 88.2 | 88.2 | 72.5 | 15.6 | — | 11.8 | 5.6 | 6.3 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 100.0 | 81.4 | 81.4 | 72.7 | 8.7 | — | 18.6 | 16.6 | 2.1 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 47.4 | 45.4 | 44.4 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 52.6 | 33.8 | 18.8 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 19.6 | — | — | — | 19.6 | 80.4 | 49.3 | 31.1 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 100.0 | 77.5 | 76.0 | — | 76.0 | 1.5 | 22.5 | 12.3 | 10.3 |

| Government public health activities | 100.0 | — | — | — | — | — | 100.0 | 11.9 | 88.1 |

| Research and construction | 100.0 | 39.7 | — | — | — | 39.7 | 60.3 | 46.8 | 13.5 |

| Research | 100.0 | 7.1 | — | — | — | 7.1 | 92.9 | 80.3 | 12.6 |

| Construction | 100.0 | 76.7 | — | — | — | 76.7 | 23.2 | 8.7 | 14.5 |

| 1990 | Amount in billions | ||||||||

| National health expenditures | $670.9 | $389.3 | $360.1 | $137.7 | $222.5 | $29.2 | $281.6 | $192.2 | $89.4 |

| Health services and supplies | 648.6 | 380.3 | 360.1 | 137.7 | 222.5 | 20.2 | 268.3 | 182.0 | 86.4 |

| Personal health care | 589.3 | 348.4 | 328.9 | 137.7 | 191.2 | 19.5 | 240.9 | 175.2 | 65.7 |

| Hospital care | 257.7 | 118.6 | 106.1 | 13.6 | 92.5 | 12.5 | 139.1 | 102.5 | 36.6 |

| Physician services | 132.7 | 88.4 | 88.3 | 25.4 | 63.0 | 0.0 | 44.3 | 35.7 | 8.6 |

| Dental services | 33.8 | 32.9 | 32.9 | 18.5 | 14.4 | — | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Other professional services | 30.7 | 24.4 | 21.1 | 9.5 | 11.6 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| Home health care | 6.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 1.1 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 48.5 | 42.3 | 42.3 | 34.9 | 7.4 | — | 6.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 14.3 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 10.4 | 1.2 | — | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| Nursing home care | 53.6 | 26.3 | 25.2 | 24.6 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 27.3 | 16.9 | 10.3 |

| Other personal health care | 11.5 | 2.2 | — | — | — | 2.2 | 9.3 | 5.7 | 3.6 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 40.5 | 31.9 | 31.2 | — | 31.2 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 4.6 | 4.1 |

| Government public health activities | 18.8 | — | — | — | — | — | 18.8 | 2.2 | 16.6 |

| Research and construction | 22.3 | 9.0 | — | — | — | 9.0 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 3.0 |

| Research | 11.7 | 0.8 | — | — | — | 0.8 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

| Construction | 10.6 | 8.2 | — | — | — | 8.2 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| Percent distribution | |||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 58.0 | 53.7 | 20.5 | 33.2 | 4.4 | 42.0 | 28.7 | 13.3 |

| Health services and supplies | 100.0 | 58.6 | 55.5 | 21.2 | 34.3 | 3.1 | 41.4 | 28.1 | 13.3 |

| Personal health care | 100.0 | 59.1 | 55.8 | 23.4 | 32.5 | 3.3 | 40.9 | 29.7 | 11.1 |

| Hospital care | 100.0 | 46.0 | 41.2 | 5.3 | 35.9 | 4.9 | 54.0 | 39.8 | 14.2 |

| Physician services | 100.0 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 19.1 | 47.5 | 0.0 | 33.4 | 26.9 | 6.5 |

| Dental services | 100.0 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 54.9 | 42.6 | — | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Other professional services | 100.0 | 79.4 | 68.9 | 30.9 | 37.9 | 10.6 | 20.6 | 15.4 | 5.2 |

| Home health care | 100.0 | 25.3 | 18.9 | 11.7 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 74.7 | 58.1 | 16.5 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 100.0 | 87.3 | 87.3 | 72.0 | 15.3 | — | 12.7 | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 100.0 | 80.9 | 80.9 | 72.3 | 8.6 | — | 19.1 | 17.0 | 2.0 |

| Nursing home care | 100.0 | 49.1 | 47.1 | 45.9 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 50.9 | 31.6 | 19.3 |

| Other personal health care | 100.0 | 19.4 | — | — | — | 19.4 | 80.6 | 49.2 | 31.5 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 100.0 | 78.7 | 77.1 | — | 77.1 | 1.6 | 21.3 | 11.2 | 10.1 |

| Government public health activities | 100.0 | — | — | — | — | — | 100.0 | 11.7 | 88.3 |

| Research and construction | 100.0 | 40.6 | — | — | — | 40.6 | 59.4 | 46.1 | 13.3 |

| Research | 100.0 | 7.0 | — | — | — | 7.0 | 93.0 | 80.2 | 12.7 |

| Construction | 100.0 | 77.5 | — | — | — | 77.5 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 14.0 |

| 19911 | Amount in billions | ||||||||

| National health expenditures | $738.2 | $421.1 | $389.4 | $148.0 | $241.5 | $31.7 | $317.1 | $215.7 | $101.4 |

| Health services and supplies | 714.4 | 411.4 | 389.4 | 148.0 | 241.5 | 22.0 | 302.9 | 204.7 | 98.3 |

| Personal health care | 651.1 | 378.4 | 357.1 | 148.0 | 209.1 | 21.3 | 272.6 | 196.9 | 75.8 |

| Hospital care | 285.4 | 128.8 | 115.2 | 14.6 | 100.6 | 13.6 | 156.6 | 114.2 | 42.4 |

| Physician services | 148.5 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 28.4 | 70.0 | 0.1 | 50.0 | 40.1 | 9.9 |

| Dental services | 36.1 | 35.1 | 35.1 | 19.8 | 15.3 | — | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Other professional services | 34.5 | 27.3 | 23.6 | 10.5 | 13.1 | 3.6 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 1.8 |

| Home health care | 7.5 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 1.3 |

| Drugs and other medical non-durables | 51.8 | 44.5 | 44.5 | 36.8 | 7.7 | — | 7.3 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Vision products and other medical durables | 14.9 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 1.3 | — | 3.0 | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| Nursing home care | 59.1 | 28.1 | 27.0 | 26.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 31.0 | 19.2 | 11.8 |

| Other personal health care | 13.3 | 2.4 | — | — | — | 2.4 | 10.9 | 6.6 | 4.2 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 43.3 | 33.0 | 32.3 | — | 32.3 | 0.7 | 10.3 | 5.5 | 4.9 |

| Government public health activities | 20.0 | — | — | — | — | — | 20.0 | 2.4 | 17.6 |