Abstract

Data from the Social Security Administration's 1982 New Beneficiary Survey and Master Beneficiary Record were matched with 1984 data from the Medicare Automated Data Retrieval System to study the effects of self-reported health on subsequent health service usage and survival. Proportionately, more new retired workers who reported poorer health in 1982 were deceased by December 1984. Functionally dependent beneficiaries as determined by the Functional Capacity Limitation Index had death rates four to five times greater than those who reported no limitations. The health status of retired workers who received Social Security benefits before age 65 was no better than beneficiaries 65 or over. Decedents were more likely than survivors to incur Medicare charges, and to have substantially higher median charges—$8,834 compared with $285.

Introduction

This article analyzes the validity of health status based on subjective survey responses, using longitudinal health outcomes in Medicare administrative records. We report preliminary findings of an analysis of the 1984 Medicare service experience and survival status of retired-worker beneficiaries interviewed in the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey (NBS).

The 1982 NBS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey that collected detailed data on job histories, health, income, and assets for a sample of persons who received their first Social Security cash benefits as retired workers in June 1980 through May 1981. In this article, retired workers include persons who received Social Security retired-worker benefits whether they had left the labor force or not. NBS interviews were conducted from October through December 1982. NBS included about 9,000 retired workers whose mean age at receipt of first benefit was 63.7 years for men and 63.1 years for women. (For further information about NBS see Maxfield, 1983.)

To compare indicators of initial 1982 health status with subsequent health outcome, data from the NBS were matched with administrative data from the Health Care Financing Administration's (HCFA) Medicare Automated Data Retrieval System (MADRS).

The MADRS is a computerized data file system maintained by HCFA which covers both Medicare Part A and Part B data, including medical service utilization and billing information for inpatient hospital, inpatient skilled nursing facilities, outpatient, home health agency, hospice, and physician services. Other types of information include reasons for entitlement to Medicare benefits, diagnosis codes for inpatient and outpatient episodes, number of admissions and length of stay, surgical indicators, hospital discharge destination, and place and type of services received. In addition to Medicare data, date of death information from the Master Beneficiary Record of the Social Security Administration (SSA) was also used.

This initial analysis deals with the first stage of a 5-year data augmentation (1984-88) pertaining to Medicare services utilization and charges incurred by NBS respondents. In addition to the study of health outcomes, enhancement of NBS with SSA and Medicare administrative data makes possible an assessment of effectiveness of self-reported health and functional status as indicators of subsequent health service utilization and survival. The resulting linked longitudinal data bases essentially represent a historical prospective design which should provide a useful analytic tool for following the life course of respective cohorts of beneficiaries, including retired and disabled workers, as they age, use health services, and die.

Procedures and overview

Health status and health outcome behavior were examined in three ways: (1) as the number and kinds of disease conditions reported in the 1982 survey; (2) as rank on a functional capacity limitation index based on survey responses to a series of items on bodily movement and manual limitations, and (3) as utilization of specific kinds of Medicare services and associated charges.

It is important to point out that, in order to be eligible for Medicare benefits, Social Security retired-worker beneficiaries must be at least 65 years of age. Hence, many of the retired-worker respondents would not have been eligible for benefits when they were interviewed in 1982. Most of the new retired-worker beneficiaries were younger than age 65 at retirement; 76 percent of the men and 84 percent of the women chose to receive their first benefit before age 65. However, by the middle of 1984 all of these younger beneficiaries were fully eligible for Medicare.

Disabled-worker beneficiaries are eligible for Medicare after 2 years of receiving disability insurance, but they are not included here. The retired worker sample of new beneficiaries was defined to exclude converted disability insurance (DI) program cases; that is, none of the retired workers interviewed had any immediate prior participation in the DI program.

We first compare the health status of new retired-worker beneficiaries by sex and age group. The health status of men and women who received Social Security benefits at 62-64 years of age is contrasted with that of beneficiaries who received benefits at the “normal” retirement age of 65 or over. We then examine the effects of the 1982 health status on subsequent survival and on Medicare services utilization as represented in the 1984 administrative data. In the final phase of analysis, we compare Medicare charges by survival status and by other factors to examine whether, as reported elsewhere (Helbing, 1983; Lubitz and Prihoda, 1984), decedents incur substantially higher charges in their last year than survivors.

We expected new retired-worker beneficiaries who reported more health conditions or who were otherwise more seriously limited in functional ability in 1982 to subsequently use more health services and to experience higher mortality. The findings generally support this expectation—poorer health status (as measured by the prevalence and types of conditions and by diminished functional capacity) was a generally satisfactory predictor of subsequent health outcome (medical services utilization, amount of charges incurred, and survival). However, there were mitigating factors that appear to have weakened the effectiveness of the survey measures as predictors. It is also evident from the findings presented in this section that the interview measures decayed in predictive power for outcomes during the 2 years following NBS.

As the results show, the relationship between prior health status reported in the survey and survival is problematical. While some beneficiaries who were rated as “healthy” in 1982 subsequently died, some “sick” beneficiaries survived through 1984.1 Some deceased beneficiaries who either did not report health conditions or who were not found to be in poor health status in 1982 subsequently incurred comparatively high medical charges in 1984, the year of death.

Retired workers who first received Social Security benefits at 62-64 years of age consistently reported, on average, more health conditions than new beneficiaries 65 years of age or over. They also reported more physical limitations. These combined measures of health status suggest that the “health” of early retirees was generally no better than that of persons who chose to retire at the “normal” retirement age of 65 or over. Our findings, however, are more suggestive than explicative when considering whether or not persons who elected to receive benefits before age 65 did so primarily for health related reasons. (For further information concerning the “early retirement health debate” see Myers, 1982; Muller and Boaz, 1988; Sherman, 1985; and Boaz and Muller, 1990.)

Measurement of initial health status

Initial health status was assessed in the NBS by questions about the presence of specified disease conditions. Functional status was measured by a series of items concerning physical functioning ability. Responses to these were combined to form an index of functional capacity limitation. Developed primarily for the disabled population, the index was designed to determine level of impairment in physical functioning associated with ability to walk, carry loads of varying weights, stoop, bend, kneel, reach or grasp, and use the fingers (Haber, 1970). Haber provided a rational scaling procedure for ranking respondents on the index. Body movement and manual limitations were combined into a single scale that included limitations in either type of physical activity. These were categorized into four major groupings: (1) no limitations in any of the specified activities; (2) manual or body movement limitations other than in walking or in the ability to use one or both hands; (3) limitations in walking or severe manual limitations; and (4) limitations in walking and in manual limitations. Following Haber, personal care and mobility limitations were added to the physical activity limitations scale to provide an index of functional limitations. Persons who were confined to home or bed, needed assistance to go outside, or who needed help with self-care activities, were classified as functionally dependent, regardless of the extent of their physical limitation.

Scores on this index are designed to represent the following five levels of functional capacity limitation: no limitation, minor, moderate, severe, and functionally dependent. NBS respondents who were classified as “functionally dependent” were bedfast or chairfast, or else unable to wash or dress. They also manifested severe morbidity as evidenced by an above average incidence of cancer and other serious disorders. New beneficiaries with severe functional activity limitations were somewhat less reliant on others for personal assistance than were functionally dependent persons, but they were otherwise very seriously limited in their ability to walk, move extremities, or carry out basic daily activities. They had the highest prevalence rates for almost all of the health conditions surveyed, which emphasizes the severity of their limitations.

Subsequent health outcome is proxied in the analysis by Medicare charges represented in the MADRS for inpatient, outpatient, physician, and home health care services.2 All fee-for-service charges billed to Medicare were used rather than Medicare payments or only “covered charges” because the primary focus is on health services usage as a proxy for health outcome. This was done to ensure that all Medicare eligible users were included. It was reasoned that charges are a better indicator of medical resources consumed rather than if only payments were used. An implicit assumption is that higher charges represent poorer concurrent health status and that persons with inpatient charges, in particular, were generally in poorer health than persons who did not receive inpatient hospital care.

Statistical reliability

In general, any difference of at least 4 percentage points is statistically significant at the .05 level of confidence. However, particular care should be taken in the interpretation of figures based on relatively small numbers of cases as well as small differences between figures. NBS is based on a complex multistage area probability sample design. Thus, the usual simple random sample estimates of sampling error are inappropriate. Conservative generalized sampling errors of estimated percentages for differences between two subgroups are available in the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey Users' Manual (Social Security Administration, 1986). A more complete discussion of the procedures for the derivation of sampling errors is found in the Manual.3

Results

Differences in functional status

Female retired workers were found to be generally more limited in their functional ability than male retired workers. As shown in Table 1, almost 6 out of 10 women (57 percent) compared with about one-half of the men (48 percent) had functional limitations. Women were also more likely than men to have severe and dependent limitations (women, 19 percent versus men, 14 percent). Beneficiaries 62-64 years of age at retirement, regardless of sex, were slightly more likely than those who retired at older ages to report severe and dependent limitations (women, 19 percent versus 17 percent; men, 15 percent versus 12 percent).

Table 1. Functional status of retired workers, by sex and age at first receipt of retired workers benefits: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Functional status | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | Age at retirement | Total | Age at retirement | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| 62-64 | 65 or over | 62-64 | 65 or over | |||

| Beneficiaries in thousands | 689.7 | 517.6 | 172.1 | 524.4 | 452.9 | 71.5 |

| Percent | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Functional status:1 | ||||||

| No limitations | 51.6 | 49.3 | 58.6 | 43.2 | 42.8 | 45.6 |

| With limitations | 48.4 | 50.7 | 41.4 | 56.8 | 57.2 | 54.4 |

| Minor | 17.8 | 16.4 | 15.7 | 21.4 | 21.5 | 21.2 |

| Moderate | 16.3 | 17.1 | 13.9 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 15.8 |

| Severe | 7.7 | 8.5 | 5.5 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 9.5 |

| Dependent | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.9 |

Coded according to the procedure developed in Haber (1970).

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

Sex and age health differences

Reversing the functional limitations findings, men were more likely to report health conditions than women and were more likely to report multiple conditions (mean among those reporting conditions: men, 2.6; women, 2.4) (Table 2).4 Fifty-six percent of the men, compared with 52 percent of the women, reported two or more conditions. Men retiring at 62-64 years of age were clearly more likely than men retiring at older ages to report multiple conditions (58 percent versus 50 percent). The differences among women were smaller and less consistent.

Table 2. Health conditions reported at initial interview, by sex and age at first receipt of retired workers benefits: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Health condition | Percent reporting selected conditions1 | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Total | Age at retirement | Total | Age at retirement | ||||

|

|

|

||||||

| 62-64 | 65 or over | 62-64 | 65 or over | ||||

| Beneficiaries in thousands | 1,214.1 | 689.7 | 517.6 | 172.1 | 524.4 | 452.9 | 71.5 |

| Percent reporting selected conditions1 | |||||||

| Disease of bones, muscles | 50.2 | 48.0 | 49.3 | 44.1 | 53.2 | 53.7 | 49.9 |

| Current heart problems | 38.5 | 37.9 | 39.1 | 34.2 | 39.3 | 39.5 | 38.2 |

| Digestive system | 18.8 | 19.5 | 21.0 | 15.0 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 16.5 |

| Stiffness or deformity | 17.4 | 18.2 | 19.8 | 13.7 | 16.4 | 16.9 | 13.3 |

| Respiratory conditions | 13.7 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 13.2 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 8.2 |

| Heart attack or stroke | 11.5 | 15.2 | 15.1 | 15.5 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Vision impairment | 10.4 | 11.4 | 12.2 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 9.8 |

| Eye disease | 10.6 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 15.2 |

| Cancer | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Nervous system condition | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Number of conditions reported | |||||||

| None | 20.7 | 19.5 | 18.5 | 22.5 | 22.4 | 21.9 | 25.3 |

| One condition | 24.9 | 24.4 | 23.2 | 27.9 | 25.7 | 25.8 | 24.6 |

| Two or more conditions | 54.3 | 56.1 | 58.3 | 49.6 | 52.0 | 52.3 | 50.1 |

| Mean excluding zero | 2.53 | 2.61 | 2.70 | 2.35 | 2.41 | 2.42 | 2.38 |

Percents add to more than 100 because of multiple reports of conditions.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

Although women were more limited in physical functioning, men appeared to have somewhat more serious health problems, judging by a greater prevalence of prior heart attacks, strokes, and respiratory conditions. Both groups, however, had similar prevalence rates for current heart problems (men, 38 percent versus women, 39 percent). Women, on the other hand, were more likely to report arthritis, rheumatism, and other conditions relating to the bones and muscles which, in part, may explain their relatively greater limitation in functional status compared with men. Sex differences for other health conditions were small.

In general, new beneficiaries 62-64 years of age reported a higher prevalence of all conditions except for current eye disease. There were no significant age related differences in the prevalence of cancer, prior heart attack, or stroke. Younger men reported the highest prevalence of problems with the digestive system (21 percent), the respiratory system (17 percent), stiffness or deformity (20 percent) and vision impairment (12 percent). Younger women had the highest prevalence of arthritis, rheumatism, and other conditions relating to the bones and muscles (54 percent).

Functional limitations and health conditions

As functional status declined, the prevalence of reported disorders generally increased among both men and women (Table 3). The mean number of health conditions for male beneficiaries reporting a health condition increased from 1.9 for those with no limitations to 4.0 for those with severe functional limitations; female beneficiaries reporting a health condition increased from 1.7 for those with no limitations to 3.5 for those with severe limitations. Functionally dependent persons, on the other hand, reported somewhat fewer conditions than those who were otherwise severely impaired (men, 3.4; women, 3.1). These results clearly indicate a positive association between Haber's functional status measure and the number of health conditions reported. However, it is also evident that a corresponding association between an increasing number of disorders and severity of health impairment should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3. Health conditions reported at initial interview, by sex and functional status: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Health condition | Total | No limitations | Minor | Moderate | Severe | Dependent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||||

| Beneficiaries in thousands | 689.7 | 354.6 | 121.9 | 112.0 | 53.2 | 45.2 |

| Reported selected conditions:1 | Percent | |||||

| Disease of bones, muscles | 48.0 | 31.8 | 63.1 | 64.9 | 83.4 | 52.0 |

| Current heart problems | 37.9 | 27.5 | 39.6 | 55.6 | 60.6 | 44.4 |

| Digestive system | 19.5 | 12.1 | 23.0 | 29.4 | 35.3 | 25.0 |

| Hearing impairment | 18.6 | 13.8 | 22.5 | 22.9 | 33.0 | 19.9 |

| Stiffness or deformity | 18.2 | 7.3 | 24.2 | 28.3 | 47.9 | 27.6 |

| Respiratory conditions | 16.2 | 9.2 | 17.9 | 26.5 | 32.0 | 21.4 |

| Heart attack or stroke | 15.2 | 9.6 | 15.4 | 24.6 | 28.5 | 17.8 |

| Vision impairment | 11.4 | 6.5 | 12.7 | 16.4 | 26.7 | 15.2 |

| Eye disease | 10.1 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 15.3 | 14.6 |

| Cancer | 3.8 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 10.2 |

| Nervous system condition | 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 4.9 | 5.2 |

| Number of conditions reported: | ||||||

| None | 19.5 | 30.9 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 20.4 |

| One condition | 24.4 | 32.1 | 21.7 | 13.9 | 5.3 | 20.6 |

| Two or more conditions | 56.1 | 37.0 | 70.4 | 81.8 | 94.2 | 59.0 |

| Mean excluding zero | 2.61 | 1.90 | 2.70 | 3.18 | 4.01 | 3.43 |

| Female | ||||||

| Beneficiaries in thousands | 524.4 | 225.7 | 112.0 | 87.4 | 57.9 | 39.3 |

| Reported selected conditions:1 | Percent | |||||

| Disease of bones, muscles | 53.2 | 29.5 | 68.1 | 67.1 | 89.6 | 62.7 |

| Current heart problems | 39.3 | 27.7 | 43.0 | 50.5 | 60.7 | 39.7 |

| Digestive system | 18.0 | 8.2 | 20.8 | 26.5 | 33.2 | 24.9 |

| Hearing impairment | 7.7 | 4.3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 10.5 |

| Stiffness or deformity | 16.4 | 3.3 | 18.0 | 25.9 | 41.9 | 28.6 |

| Respiratory conditions | 10.5 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 19.9 | 23.1 | 13.4 |

| Heart attack or stroke | 6.6 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 10.7 | 17.4 | 12.2 |

| Vision impairment | 9.0 | 5.2 | 8.6 | 10.5 | 18.0 | 15.8 |

| Eye disease | 11.3 | 8.7 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 14.2 | 13.9 |

| Cancer | 3.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 6.3 |

| Nervous system condition | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 5.1 |

| Number of conditions reported: | ||||||

| None | 22.4 | 39.6 | 11.8 | 7.5 | 0.9 | 16.5 |

| One condition | 25.7 | 34.1 | 26.7 | 17.5 | 8.9 | 17.6 |

| Two or more conditions | 52.0 | 26.3 | 61.5 | 75.0 | 90.1 | 65.9 |

| Mean excluding zero | 2.41 | 1.66 | 2.37 | 2.75 | 3.47 | 3.06 |

Percents add to more than 100 because of multiple reports of conditions.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

Although severely impaired persons reported more disorders on average, functionally dependent persons may have had conditions that were progressively more debilitating and subsequently more lethal in the short run. Functionally dependent men were more likely to report cancer than severely limited men (10.2 percent versus 6.0 percent). As the findings in the next section show, the life spans of functionally dependent men were shorter than those for severely limited men.

Health status and subsequent survival

Nearly all new retired-worker beneficiaries survived through 1984; men, 95 percent; women, 98 percent (Table 4). Survival rates for both younger and older men were similar despite the higher expected death rate for the older group. This lends support to the earlier observation that younger male beneficiaries were generally in poorer health. Survival rates for both older and younger women, like those of men, were very similar despite a higher expected death rate for the older group.

Table 4. Survival status by sex, age, and functional status: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Selected characteristics | Number of beneficiaries in thousands | Total percent | Survival status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Alive through 1984 | Deceased during 1984 | Deceased before 1984 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 689.7 | 100.0 | 95.0 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Age at retirement: | |||||

| 62-64 years | 517.6 | 100.0 | 94.9 | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| 65 years or over | 172.1 | 100.0 | 95.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Female | 524.4 | 100.0 | 97.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Age at retirement: | |||||

| 62-64 years | 452.9 | 100.0 | 97.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| 65 years or over | 71.5 | 100.0 | 96.8 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| Functional status | |||||

| Male: | |||||

| No limitations | 354.6 | 100.0 | 97.0 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Minor | 121.9 | 100.0 | 96.2 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| Moderate | 112.0 | 100.0 | 91.6 | 3.1 | 5.3 |

| Severe | 53.2 | 100.0 | 92.4 | 3.8 | 3.8 |

| Dependent | 45.2 | 100.0 | 87.3 | 3.8 | 9.0 |

| Female: | |||||

| No limitations | 225.7 | 100.0 | 99.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Minor | 112.0 | 100.0 | 98.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Moderate | 87.4 | 100.0 | 97.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Severe | 57.9 | 100.0 | 96.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| Dependent | 39.3 | 100.0 | 90.0 | 3.1 | 6.9 |

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

Functional status was clearly associated with survival. Beneficiaries who reported no limitations or who had minor limitations in 1982 were the most likely to survive through 1984, while those rated as functionally dependent were the least likely to survive. Eighty-seven percent of functionally dependent men and 90 percent of functionally dependent women survived, a much lower survival rate than for all men or all women (men, 95 percent; women, 98 percent) (Table 4). A substantial proportion of deaths among functionally dependent beneficiaries occurred prior to 1984. This suggests, as noted earlier, that functional dependency reflects not only multiple disorders associated with higher mortality but, more important, a level of declining vitality not clearly evident in the subjective survey reports indicative of morbidity.

Health care service charges

The combined fee for Medicare service charges for the 1.2 million new retired-worker beneficiaries who survived to 1984 totalled $1.6 billion (Table 5).5

Table 5. Percent distribution of 1984 Medicare charges incurred by retired workers, by type of charge and survival status: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Survival status and type of Medicare service | Number of persons in thousands | 1984 medical charges1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Dollars in millions | Median2 | Percent | None | Less than $1,000 | $1,000-$4,999 | $5,000-$9,999 | $10,000 or more | ||

| All beneficiaries | 1,189.0 | $1,637.2 | $296.49 | 100.0 | 42.0 | 41.0 | 10.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Died in 19843 | 21.4 | 261.3 | 8,834.19 | 100.0 | 24.6 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 36.5 |

| Alive through 1984 | 1,167.6 | 1,375.9 | 284.55 | 100.0 | 42.4 | 41.5 | 10.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Beneficiaries with charges | 689.1 | 1,637.2 | 296.49 | 100.0 | — | 70.8 | 17.8 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Died in 19843 | 16.1 | 261.3 | 8,834.19 | 100.0 | — | 18.9 | 18.8 | 13.8 | 48.4 |

| Alive through 1984 | 673.0 | 1,375.9 | 284.55 | 100.0 | — | 72.0 | 17.8 | 5.6 | 4.6 |

| Type of charges | |||||||||

| Inpatient | 175.6 | 1,290.6 | 3,598.68 | 100.0 | — | 6.3 | 55.0 | 20.2 | 18.5 |

| Died in 19843 | 13.2 | 243.1 | 11,634.68 | 100.0 | — | 4.3 | 21.5 | 19.4 | 54.8 |

| Alive through 1984 | 162.3 | 1,047.5 | 3,458.51 | 100.0 | — | 6.4 | 57.7 | 20.3 | 15.6 |

| Inpatient with surgery | 117.9 | 1,011.9 | 4,591.60 | 100.0 | — | 4.3 | 48.6 | 24.3 | 22.8 |

| Died in 1984 | 8.8 | 182.1 | 13,167.00 | 100.0 | — | 5.1 | 17.3 | 18.9 | 58.7 |

| Alive through 1984 | 109.1 | 829.8 | 4,296.33 | 100.0 | — | 4.3 | 51.1 | 24.7 | 19.9 |

| Inpatient without surgery | 57.7 | 278.6 | 2,541.30 | 100.0 | — | 10.2 | 68.1 | 12.0 | 9.8 |

| Died in 1984 | 4.4 | 61.0 | 8,058.92 | 100.0 | — | 2.8 | 29.7 | 20.3 | 47.2 |

| Alive through 1984 | 53.2 | 217.7 | 2,355.89 | 100.0 | — | 10.8 | 71.3 | 11.3 | 6.7 |

| Outpatient | 317.7 | 161.3 | 160.23 | 100.0 | — | 90.7 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Died in 19843 | 9.0 | 12.1 | 331.50 | 100.0 | — | 76.4 | 17.2 | 3.9 | 2.5 |

| Alive through 1984 | 308.7 | 149.2 | 156.51 | 100.0 | — | 91.1 | 8.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Physician | 602.9 | 164.1 | 156.99 | 100.0 | — | 96.3 | 3.6 | 0.1 | — |

| Died in 19843 | 8.7 | 4.0 | 131.70 | 100.0 | — | 89.1 | 10.0 | 0.9 | — |

| Alive through 1984 | 594.2 | 160.2 | 157.07 | 100.0 | — | 96.4 | 3.5 | 0.1 | — |

| Home health | 15.7 | 21.2 | 607.16 | 100.0 | — | 62.1 | 30.7 | 7.2 | — |

| Died in 19844 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 801.56 | 100.0 | — | 62.0 | 38.0 | — | — |

| Alive through 1984 | 13.1 | 19.0 | 605.69 | 100.0 | — | 62.2 | 29.2 | 8.6 | — |

Includes all charges billed under the Medicare program: Inpatient, outpatient, physician, home health, and hospice care.

Excludes zero values.

Beneficiaries deceased in 1982 through 1983 are not shown.

Figure may have low statistical reliability because of a cell size of less than 30 cases.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

The mean Medicare charge for those with charges was almost $2,400, but this average was extremely inflated by the large charges of a few beneficiaries. About two-fifths of the retired-worker beneficiaries had no charges in 1984, and another two-fifths had charges of less than $1,000. Only 3 percent had charges of $10,000 or more. A more stable measure of usage is the median medical charge, which was just below $300 for those with any charge.6

Charges were substantially higher for those who died during the year.7 Decedents represented only 2 percent of new retired-worker beneficiaries, but accounted for 16 percent of the total 1984 charges (Table 5). Although one-fourth had no charges, one-third of the decedents had charges of $10,000 or more, compared with only about 3 percent of the survivors. Similarly, among beneficiaries with charges, decedents had a much higher median charge than survivors: $8,834 compared with $285. Even among the select group with charges of $10,000 or more, decedents had a higher median: $26,170 versus $17,541.

Inpatient charges

Among the types of charges submitted for Medicare payment (inpatient, outpatient, home health, and physician services), inpatient charges were by far the most substantial. Almost 80 percent of total medical charges were for inpatient services, even though only slightly more than 25 percent of the beneficiaries with charges received inpatient care. The median inpatient care ($3,599) was more than 20 times greater than the median outpatient or physician charge (about $160 each). Charges were especially high when inpatient episodes included surgical procedures (median: with surgery $4,592; without surgery $2,541) (Table 5).

Inpatient charges were also especially high for those who died in 1984. Decedents were much more likely than survivors to incur them (62 percent versus 14 percent), and—for those with charges—the median inpatient charge for decedents ($11,635) was more than three times that for survivors ($3,459). Almost three-fourths of the decedents with charges had inpatient charges of at least $5,000; over one-half had charges more than $10,000. In contrast, nearly two-thirds of the survivors with charges had inpatient charges less than $5,000 and only one out of six had inpatient charges as high as $10,000. The large portion of decedents with inpatient charges and the high median charge combined to make inpatient charges 93 percent of all decedent charges. By comparison only 76 percent of total survivor charges were for inpatient care.

Outpatient charges

Forty-six percent of new beneficiaries with medical charges received outpatient care and 91 percent of these charges were less than $1,000. Beneficiaries who died had a median outpatient charge of about twice that of survivors ($332 versus $157).

Physician charges

More than one-half of all new retired-worker beneficiaries had medical charges for physician services, and almost 90 percent of those with any medical charges received them. However, most of the 1984 physician service charges were not very large—only $157 on average, and 96 percent of the charges were less than $1,000.

Although a greater proportion of decedents used inpatient and outpatient services, and had higher median charges for them, the opposite pattern was observed for physician services. Only 41 percent of decedents had charges for physician services, compared with 51 percent of survivors; moreover, the median charge for physician services was lower for decedents ($132 versus $157).8

Home health care charges

Approximately one-sixth of decedents with medical charges had home health care charges compared with only 2 percent of all survivors with medical charges. The median home health care charge was substantially lower than the median inpatient charge ($600 versus $3,600) but higher than the median outpatient charge ($160).

Sex and age charge patterns

Women beneficiaries were more likely than men to incur charges (60 percent versus 56 percent). However, the total charge for men was greater than that for women. A larger proportion of those who became entitled to benefits at age 65 or over had charges (Table 6).

Table 6. Percent distribution of selected 1984 Medicare charges at receipt of retired worker benefits, by sex and age: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey1.

| Selected Medicare charges | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | Age at retirement | Total | Age at retirement | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| 62-64 | 65 or over | 62-64 | 65 or over | |||

| Total persons in thousands | 670.5 | 502.8 | 167.7 | 518.5 | 447.9 | 70.7 |

| Total with charges | 375.5 | 270.2 | 105.3 | 313.6 | 267.7 | 45.9 |

| Percent with charges | 56.0 | 53.8 | 62.8 | 60.5 | 59.8 | 64.9 |

| Total charges in millions | $1,026.3 | $714.6 | $311.7 | $610.8 | $506.1 | $104.8 |

| Percent distribution2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Inpatient | 81.6 | 82.8 | 78.8 | 74.2 | 73.7 | 76.7 |

| Outpatient | 9.1 | 8.0 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 9.7 |

| Physician | 8.4 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 10.7 |

| Home health | 0.9 | 1.1 | .4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.9 |

| Percent of beneficiaries | ||||||

| Inpatient | 28.4 | 28.1 | 29.0 | 22.0 | 22.4 | 19.7 |

| Outpatient | 46.5 | 46.3 | 47.0 | 45.6 | 45.9 | 44.0 |

| Physician | 85.3 | 83.9 | 88.7 | 90.1 | 90.0 | 91.1 |

| Home health | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 3.7 |

Excludes beneficiaries who died before 1984.

Hospice charges were less than 1 percent and are not shown.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

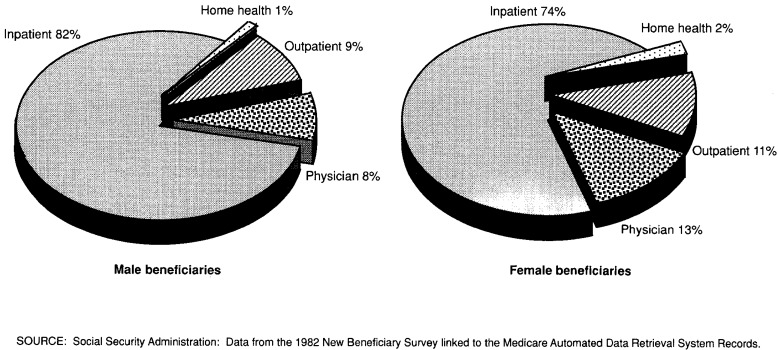

Among those with Medicare charges, men were more likely than women to incur charges for inpatient services (28 percent versus 22 percent), and correspondingly a greater share of their total charges were for inpatient services (82 percent versus 74 percent) (Figure 1). This is the major reason why men had higher average Medicare charges than women.

Figure 1. Percent of total selected Medicare charges, by sex: 1984.

Functional status charge patterns

For men, the degree of functional limitation did not make much difference in the percentage with charges. This ranged from 54 percent for the dependent group to 59 percent for those with minor functional limitations (Table 7). However, the type of charge varied substantially. The percentage with inpatient charges rose incrementally with the severity of their 1982 reported functional limitations (no limitations, 24 percent; dependent, 41 percent). The percentage with charges for outpatient and home care also rose as functional limitations increased but to a much lesser degree. In contrast, the percent with charges for physician services incurred by men diminished as the functional limitation level increased.

Table 7. Percent distribution of selected 1984 Medicare charges, by functional status and sex: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey1.

| Selected Medicare charges | Total | No limitations | Minor | Moderate | Severe | Dependent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||||

| Total persons in thousands | 670.5 | 349.0 | 120.2 | 106.0 | 51.2 | 41.3 |

| Total with charges | 375.5 | 193.1 | 70.6 | 59.5 | 28.8 | 22.1 |

| Percent with charges | 56.0 | 55.3 | 58.7 | 56.1 | 56.2 | 53.5 |

| Total charges in millions | $1,026.3 | $397.4 | $184.5 | $220.0 | $108.9 | $106.7 |

| Percent distribution2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Inpatient | 81.6 | 77.2 | 82.4 | 84.3 | 87.5 | 84.0 |

| Outpatient | 9.1 | 10.3 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 10.8 |

| Physician | 8.4 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 4.9 |

| Home health | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| Percent of beneficiaries: | ||||||

| Inpatient | 28.4 | 23.7 | 28.5 | 32.6 | 40.4 | 41.2 |

| Outpatient | 46.5 | 44.3 | 48.5 | 47.9 | 50.1 | 49.7 |

| Physician | 85.3 | 86.3 | 86.2 | 84.7 | 83.4 | 78.3 |

| Home health | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.4 |

| Female | ||||||

| Total persons in thousands | 518.5 | 225.4 | 111.0 | 86.3 | 57.2 | 36.6 |

| Total with charges | 313.6 | 126.1 | 71.5 | 55.2 | 35.9 | 23.3 |

| Percent with charges | 60.5 | 55.9 | 64.4 | 64.0 | 62.8 | 63.7 |

| Total charges in millions | $610.8 | $177.3 | $136.6 | $139.6 | $86.2 | $65.8 |

| Percent distribution2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Inpatient | 74.2 | 72.1 | 70.0 | 78.7 | 74.7 | 77.5 |

| Outpatient | 11.2 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 9.5 |

| Physician | 12.7 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 7.8 |

| Home health | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 5.2 |

| Percent of beneficiaries: | ||||||

| Inpatient | 22.0 | 17.0 | 22.3 | 27.8 | 26.4 | 27.1 |

| Outpatient | 45.6 | 44.3 | 46.1 | 47.0 | 49.0 | 42.2 |

| Physician | 90.1 | 90.5 | 91.5 | 89.6 | 85.4 | 92.2 |

| Home health | 2.2 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 4.5 |

Excludes beneficiaries who died before 1984.

Hospice charges were less than 1 percent and are not shown.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

These Medicare charge patterns found to be associated with male functional status were not generally observed for women (Table 7). A larger percentage of men who were severely limited or dependent were more likely than were women to use inpatient services (14 percent difference). Also, even those men who were less functionally limited were more likely to use inpatient services (6 percent difference). Dependent women, on the other hand, were more likely than their male counterparts to use physician services (92 percent versus 78 percent).

The distributions further show that the types of charges incurred follow the same pattern found previously—inpatient charges represent the majority of charges for both men and women; outpatient and physician charges each account for about 10 percent of total charges. Charges for inpatient care represent a greater share of total charges for men than for women (82 percent versus 74 percent). A necessary consequence is that the share of total charges for physician, outpatient, and home health services is slightly greater for women.

Health conditions and subsequent charges

Better health and functional status in 1982 were expected to result in fewer subsequent medical service charges. This appears to be the case for beneficiaries who survived through 1984 (Table 8). Surviving beneficiaries who reported no health conditions in 1982 tended to incur no charges, or at least no fee-for-service charges (53 percent compared with 39 percent). These survivors also had lower median charges than those who reported health conditions ($224 versus $301). As noted previously, decedents were more likely to incur 1984 charges.

Table 8. Selected characteristics of retired worker beneficiaries, by 1984 Medicare charges: 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

| Selected characteristics | Number of persons in thousands | 1984 medical charges1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Dollars in millions | Median2 | Percent | None | Less than $1,000 | $1,000-$4,999 | $5,000-$9,999 | $10,000 or more | ||

| All beneficiaries | 1,189.0 | $1,637.2 | $296.49 | 100.0 | 42.0 | 41.0 | 10.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Died in 19843 | 21.4 | 261.3 | 8,834.19 | 100.0 | 24.6 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 36.5 |

| Alive through 1984 | 1,167.6 | 1,375.9 | 284.55 | 100.0 | 42.4 | 41.5 | 10.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| 1982 Health conditions | |||||||||

| None reported | 249.1 | 209.2 | 230.52 | 100.0 | 53.2 | 36.3 | 6.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Died in 19844 | 2.9 | 36.7 | 13,472.39 | 100.0 | 12.1 | 26.0 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 50.7 |

| Alive through 1984 | 246.2 | 172.5 | 223.72 | 100.0 | 53.7 | 36.4 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| Some reported | 939.9 | 1,427.9 | 312.60 | 100.0 | 39.1 | 42.3 | 11.3 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Died in 1984 | 18.5 | 224.6 | 8,363.06 | 100.0 | 26.5 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 11.0 | 34.3 |

| Alive through 1984 | 921.4 | 1,203.3 | 301.11 | 100.0 | 39.3 | 42.9 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 3.1 |

| 1982 Functional status | |||||||||

| No limitations | 574.4 | 574.8 | 249.41 | 100.0 | 44.4 | 42.1 | 8.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| Died in 1984 | 5.9 | 68.2 | 11,846.44 | 100.0 | 29.7 | 16.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 38.7 |

| Alive through 1984 | 568.5 | 506.6 | 243.86 | 100.0 | 44.6 | 42.4 | 8.6 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Some limitations | 609.9 | 1,048.3 | 348.85 | 100.0 | 39.8 | 40.0 | 11.9 | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| Died in 1984 | 15.0 | 181.4 | 8,012.51 | 100.0 | 23.4 | 13.7 | 17.5 | 11.8 | 33.6 |

| Alive through 1984 | 594.9 | 866.9 | 332.78 | 100.0 | 40.3 | 40.6 | 11.7 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| 1982 Median income | |||||||||

| At or above median | 597.4 | 827.4 | 296.29 | 100.0 | 37.0 | 45.2 | 10.7 | 3.8 | 3.2 |

| Died in 1984 | 9.5 | 102.6 | 7,681.00 | 100.0 | 23.0 | 15.4 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 33.1 |

| Alive through 1984 | 587.9 | 724.8 | 286.55 | 100.0 | 37.3 | 45.7 | 10.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

| Below median | 591.6 | 809.7 | 296.79 | 100.0 | 47.1 | 36.8 | 9.9 | 2.9 | 3.3 |

| Died in 1984 | 12.0 | 158.7 | 10,689.87 | 100.0 | 25.9 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 8.5 | 39.2 |

| Alive through 1984 | 579.6 | 651.0 | 282.04 | 100.0 | 47.5 | 37.2 | 9.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| 1982 Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 926.1 | 1,223.0 | 290.41 | 100.0 | 41.2 | 41.9 | 10.6 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Died in 1984 | 14.8 | 177.3 | 8,022.32 | 100.0 | 20.1 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 12.4 | 35.4 |

| Alive through 1984 | 911.3 | 1,045.7 | 279.29 | 100.0 | 41.5 | 42.3 | 10.5 | 3.1 | 2.6 |

| Not married | 262.9 | 414.2 | 318.21 | 100.0 | 45.2 | 37.9 | 9.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| Died in 1984 | 6.6 | 84.0 | 14,505.81 | 100.0 | 34.7 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 6.0 | 39.0 |

| Alive through 1984 | 256.3 | 330.1 | 305.61 | 100.0 | 45.4 | 38.6 | 9.4 | 3.5 | 3.0 |

Includes all charges billed under the Medicare program: Inpatient, outpatient, physician, home health, and hospice care.

Excludes zero values.

Beneficiaries deceased in 1982 through 1983 are not shown.

Figure may have low statistical reliability because of cell size of less than 30 cases.

SOURCE: Social Security Administration: Data from the 1982 New Beneficiary Survey.

Income status and Medicare charges

The research literature generally concludes that low income and poor health are correlated and to some degree mutually reinforcing, but, in general, low income results in poor health status (National Center for Health Statistics, 1964; Luft, 1978). Income9 appears to have had little effect on the amount of charges survivors incurred in 1984. However, low-income survivors were less likely to have Medicare charges. Only one-half (53 percent) of survivors with incomes below the median income incurred charges, compared with nearly two-thirds (63 percent) with median or higher income. The median charge for survivors was almost identical for those with below median ($282) and above median ($287) income.

Although low-income decedents were also slightly less likely to incur Medicare charges, their charges were higher (Table 8). About three-quarters of all decedents, regardless of income level, had Medicare charges in 1984, but the median 1984 Medicare charge was $3,000 higher among low-income decedents. A number of explanations are suggested:

Lower-income persons may not engage in health maintenance behavior to the extent that persons of higher income status do, perhaps because of a lack of health insurance coverage. Thus, when serious life-threatening events occur, health care costs are greater.

Lower income persons' prior employment in more physically demanding occupations had subsequent detrimental health effects.

Lower income persons may have had a protracted lack of adequate insurance coverage at younger ages which served as barriers to needed health care.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the high cost of dying reported elsewhere (Lubitz and Prihoda, 1984; Helbing, 1983; Piro and Lutens, 1973). Medicare charges for decedent beneficiaries greatly exceeded those for survivors, and inpatient hospital care accounted for the largest proportion by far of all charges. However, in the entire cohort of retired workers, the much larger pool of survivors accounted for most of the Medicare charges (84 percent or 1.4 billion dollars).

Prior self-reported health and physical functioning capacity proved, by and large, to be viable and reliable predictors of survival and subsequent medical service utilization in terms of dollars charged. However, the time interval between the survey measures of health status and the administrative measures of health outcomes raises methodological questions.

The findings suggest that health status, as measured by respondent awareness of one or more health conditions, was a more sensitive measure of subsequent health services utilization than was functional capacity limitation. On the other hand, functional limitation appears to be an overall more sensitive indicator of survival status, probably because it reflects severity of morbidity, particularly among the functionally dependent population. As noted earlier, beneficiaries who were functionally dependent at the initial interview were the least likely to survive through 1984. However, it is clear that each of these measures need further evaluation within the context of a multivariate analytical framework in order to more effectively assess their predictive performance capabilities.

The study findings suggest a picture of substantial change in an aging population whose health service and personal needs are growing over time. The findings of association between self-reported health and subsequent health utilization experience raise several questions that deserve further examination. How does changing health status affect health services utilization in general, and Medicare utilization in particular, over a protracted period of time? To what extent are health conditions that can be identified shortly after retirement important in explaining subsequent Medicare utilization and charges? What kinds of predictive models or scenarios of health care are most appropriate in identifying the future needs of Social Security beneficiary populations? How do these special beneficiary groups differ from groups of similar sex and age composition in the general population?

These initial findings call for further analysis of prior health status indicators as epidemiological variables among an aging population of retired-worker (and disabled-worker) beneficiaries. The findings also indicate a need for further research concerning the role played by sociodemographic factors, including income and wealth as well as health insurance coverage, in the prediction and explanation of Medicare utilization patterns and charges. Knowledge of the extent to which functionally limited retired and disabled workers have similar patterns of utilization will provide further understanding on the relation of health demand to income and wealth.

Future plans call for extensive use of the linked MADRS data elements and information to be obtained in the New Beneficiary Followup (NBF) that will be completed approximately 10 years after initial data collection. These future studies will include longitudinal analysis of utilization experience during a 5-year period, 1984-88, and will focus on multivariate aspects of health service utilization as related to combinations of sociodemographic and other factors.

Some of the research and policy issues being considered for analysis include: the extent to which low-income beneficiaries differ from middle and higher income groups in their utilization of hospital services; how utilization varies by marital status and by social support network factors; the extent to which prior health status and socioeconomic factors explain subsequent patterns of morbidity as indicated by principal diagnoses represented in the MADRS data and how these morbidity factors, in turn, explain mortality among Social Security beneficiaries; and whether decedents incur high medical charges during a protracted period or whether their relatively high charges are compressed into a short time period immediately prior to death.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Clark of the Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Lawrence Haber, a private consultant in the field of disability, Mary Grace Kovar, of the National Center for Health Statistics, and Gerald Riley of the Health Care Financing Administration for their comments on earlier drafts. We are also indebted to Janet O'Leary and David Gibson for their valuable advice concerning MADRS.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: John L. McCoy, Ph.D., Social Security Administration, Van Ness Centre, 4301 Connecticut Avenue, Washington, D.C. 20008.

These seeming discrepancies between health status measures and outcomes are perhaps best explained by: time measurement differences between the two periods 1982 and 1984; the impact of more chronic non-lethal conditions versus the rapid terminal decline associated with certain health disorders; and measurement error.

Since only one respondent was reported having hospice care in 1984, these charges are not included in the analysis. It is anticipated that as health needs and mortality increase in later years, hospice usage will become more prevalent.

A technical discussion of statistical reliability procedures is available from the authors on request.

NBS only obtained data on the existence of a health condition, not on the severity of the condition.

The charges shown represent the total annual charges and were not adjusted for the period of time retired workers were alive.

The median value is the value at the midpoint of a distribution. In this case, one-half of the beneficiaries with medical charges had charges of $296.49 or more, and one-half had charges less than that amount.

The amount and types of medical charges represented in the MADRS files can be considered as proxies for health status and, when associated with survival status, indicate a severity of illness and morbidity that is not otherwise available. Higher overall inpatient charges, in particular, are reasoned to be viable and dependable indicators of poorer health status.

People with life threatening illnesses or injuries may be taken directly to hospitals immediately prior to death and may never have direct contact with the family or personal physician. Charges for these terminal episodes would be billed directly by the hospital as inpatient services. Lower median physician charges may also be explained by the possibility that decedents had less opportunity than survivors to make multiple visits to their physicians. Even if decedents had higher per visit charges than the average Medicare beneficiary, a smaller average number of visits could result in a lower median charge.

The effects of income status are represented in the analysis as an aggregate summary measure. The 1982 NBS identified income amounts in each of 3 previous months from different sources. The objective is to compare the relative income of individuals, otherwise respondents with spouses would have higher income status reflecting the total combined income of the unit. Income from all sources was summed over 3 months and a per capita estimate was derived for currently married beneficiaries by dividing couples' income in half.

References

- Boaz RF, Muller CF. The Validity of Health Limitations as a Reason for Deciding to Retire. Health Services Research. 1990 Jun;25(2):361–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber L. Social Security Survey of the Disabled: 1966. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jul, 1970. The Epidemiology of Disability: II. The Measurement of Functional Capacity Limitation. Report No. 10. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing C. Health Care Financing Notes. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration; 1983. Medicare: Use and reimbursement for aged persons by survival status, 1979. HCFA Pub. No. 03166. [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz J, Prihoda R. Health Care Financing Review. 3. Vol. 5. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Spring. 1984. Use and costs of Medicare services in the last 2 years of life; pp. 117–131. HCFA Pub. No. 03169. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft H. Poverty and Health. Ballinger: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield LD. Social Security Bulletin. No. 1. Vol. 48. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov. 1983. The New Beneficiary Survey: An Introduction. Pub. No. 13-11700. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CF, Boaz RF. Health as a Reason or a Rationalization for Being Retired? Research on Aging. 1988 Mar.10(1):37–55. doi: 10.1177/0164027588101002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RJ. Social Security Bulletin. No. 9. Vol. 45. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1982. Why Do People Retire From Work Early? Pub. No. 13-11700. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Medical Care, Health Status and Family Income. No. 9. Series 10. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1964. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Packard M. Social Security Bulletin. No. 2. Vol. 48. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Feb. 1985. Health status of new retired-worker beneficiaries: Findings from the New Beneficiary Survey. Pub. No. 13-11700. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piro PA, Lutins T. Health Insurance Statistics. Washington: Oct. 1973. Utilization and reimbursement under Medicare for persons who died in 1967 and 1968. HI 51. DHEW Pub. No. 74-11702. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SR. Social Security Bulletin. No. 3. Vol. 48. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Mar. 1985. Reported Reasons Retired Workers Left Their Jobs: Findings From the New Beneficiary Survey. Pub. No. 13-11700. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. The 1982 New Beneficiary Survey Users' Manual. Department of Health and Human Services; Apr. 1986. [Google Scholar]