Abstract

Background

Despite treatment recommendations from various organizations, oral rehydration therapy (ORT) continues to be underused, particularly by physicians in high-income countries. We conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to compare ORT and intravenous therapy (IVT) for the treatment of dehydration secondary to acute gastroenteritis in children.

Methods

RCTs were identified through MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, authors and references of included trials, pharmaceutical companies, and relevant organizations. Screening and inclusion were performed independently by two reviewers in order to identify randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials comparing ORT and IVT in children with acute diarrhea and dehydration. Two reviewers independently assessed study quality using the Jadad scale and allocation concealment. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second. The primary outcome measure was failure of rehydration. We analyzed data using standard meta-analytic techniques.

Results

The quality of the 14 included trials ranged from 0 to 3 (Jadad score); allocation concealment was unclear in all but one study. Using a random effects model, there was no significant difference in treatment failures (risk difference [RD] 3%; 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 0, 6). The Mantel-Haenzsel fixed effects model gave a significant difference between treatment groups (RD 4%; 95% CI: 2, 5) favoring IVT. Based on the four studies that reported deaths, there were six in the IVT groups and two in ORT. There were no significant differences in total fluid intake at six and 24 hours, weight gain, duration of diarrhea, or hypo/hypernatremia. Length of stay was significantly shorter for the ORT group (weighted mean difference [WMD] -1.2 days; 95% CI: -2.4,-0.02). Phlebitis occurred significantly more often with IVT (number needed to treat [NNT] 33; 95% CI: 25,100); paralytic ileus occurred more often with ORT (NNT 33; 95% CI: 20,100). These results may not be generalizable to children with persistent vomiting.

Conclusion

There were no clinically important differences between ORT and IVT in terms of efficacy and safety. For every 25 children (95% CI: 20, 50) treated with ORT, one would fail and require IVT. The results support existing practice guidelines recommending ORT as the first course of treatment in appropriate children with dehydration secondary to gastroenteritis.

Background

Gastroenteritis is characterized by the acute onset of diarrhea, which may or may not be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain [1]. It can be caused by a variety of infectious agents [2]. Worldwide, 12% of deaths among children less than five years of age are due to diarrhea [3]. Almost 50% of these deaths are due to dehydration and most involve children less than one year of age [4].

Widespread use of oral rehydration salt solutions began in the 1970s as an effective and inexpensive method of treating mild to moderate dehydration [5]. Despite the success of oral rehydration therapy (ORT), its proven efficacy [6] and recommendations for use by various organizations [1,5], studies show that ORT continues to be underused globally [7], and specifically by physicians in high-income countries [8-11]. A recent report showed that ORT is being delivered to only 20% of the world's children who could benefit and that widespread use could prevent 15% of deaths among children under five years [8]. Postulated reasons for underuse include the fear of inducing iatrogenic hypernatremia, time requirements, questionable efficacy in moderate dehydration, and parental preference [12].

Although intravenous therapy (IVT) is rapid and effective in promptly reversing hypovolemic shock, it has some disadvantages. Since it must be administered in an outpatient or inpatient setting by specially trained staff, it is expensive both financially and in terms of human resources. IVT is associated with complications related to rapid over-correction of electrolyte imbalances [13], extravasation of infused solutions into surrounding tissues [14], and infection or inflammation [14]. Though ORT should not be used in cases of paralytic ileus, it can be used safely in children of all ages, in cases of acidosis, and in cases of hyponatremic or hypernatremic dehydration [15]. It is less traumatic to the child [15], simpler to administer, and can be administered by parents in a variety of settings including the home [1]. Research has shown ORT to be less expensive than IVT, and to be associated with lower hospital admission rates and shorter lengths of stay [16,17].

In an earlier meta-analysis, Gavin et al found that failure of ORT was uncommon and that ORT may be associated with more favorable outcomes [6]. The review was critically appraised by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) which concluded that the findings were likely reliable [18]. In addition, we evaluated the review by applying Oxman and Guyatt's index of the scientific quality of research overviews [19]. Weaknesses identified were a limited search (English only and all included studies were from high-income countries) and lack of assessment and consideration of the validity of the included studies.

Despite the existing evidence, ORT continues to be underused worldwide, and researchers continue to publish studies comparing ORT and IVT [20]. The purpose of this review was to update and expand on the work begun by Gavin et al with increased scope (countries of all income levels) and comprehensiveness (language of publication). Our aim was to conduct a systematic review according to rigorous methodological standards in order to synthesize the available evidence comparing ORT to IVT in the treatment of dehydration secondary to acute gastroenteritis in children. A secondary objective was to evaluate whether further research, comparing ORT and IVT, is warranted. This review has been registered with the Cochrane Collaboration; regular updates will be available in the Cochrane Library.

Methods

We searched CENTRAL (Issue 2, 2003), EMBASE (1988–2003), and MEDLINE (1966–July 2003). The complete search strategies are presented in an additional file (See Additional File 1: search_strategies.pdf). In addition, we contacted the primary authors of included studies, relevant organizations, and manufacturers of commercial rehydration solutions for additional trials. Finally, we examined the reference lists of existing reviews and relevant trials.

Two reviewers (SB, KR, or LH) independently screened the output from the searches to identify potentially relevant studies. Two reviewers (KR, DM, or LH) independently assessed each trial for inclusion using predetermined eligibility criteria. We considered studies for inclusion if they were randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials comparing ORT (administered orally [PO] or via nasogastric tube [NG]) and IVT in children one day to 18 years of age with acute diarrhea and dehydration. Studies that included malnourished children were considered. We excluded studies that evaluated populations with cholera. We did not restrict inclusion by language of publication, country of study, or publication status.

Two reviewers (SB, WC or KR, LH) independently assessed study quality. We evaluated studies using the validated Jadad scale that assesses randomisation, double-blinding, and withdrawals and drop-outs [21]. We assessed allocation concealment as adequate, inadequate, or unclear [22]. Assessment was based on information provided in the published manuscript. We resolved any differences by consensus.

One reviewer (SB, KR, or LH) extracted data using a standard data extraction form. A second reviewer (KR or NW) checked data for accuracy and completeness and entered data into Review Manager 4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2001). We requested additional data from authors as necessary. The primary outcome was failure of rehydration as defined by the primary studies. Secondary outcomes included death, weight gain, length of inpatient hospital stay, incidence of hypernatremia and hyponatremia, duration of diarrhea, total fluid intake, total sodium intake, and serum sodium levels. We also collected data on complications and adverse events.

We analyzed data using Review Manager 4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2001) and Splus 2000 (Insightful Corporation, 1999). We expressed dichotomous data as a risk difference. When outcomes were significant, we calculated the number needed to treat to help clarify the degree of benefit for the given IVT risk. We calculated IVT risks using the weights from the appropriate risk difference meta-analysis. We converted continuous data to a mean difference and calculated an overall weighted mean difference. One study [23] stratified their data by the two sites (USA and Panama); these were weighted separately in the analysis and considered as two studies in the tables. We analyzed the results using a random effects model. The Chi-square test for heterogeneity [24] was assessed at P = 0.10. We explored possible sources of heterogeneity by subgroup and sensitivity analyses on the primary outcome using meta-regression in Stata 7.0 (Stata Corporation, 2001). These included: inpatient/outpatient status, patient age, state of nourishment, extent of dehydration, country's income status, Jadad score, allocation concealment, and funding support. The relationship between the osmolarity of the ORT solution and failure to rehydrate was explored post hoc using a Chi-square subgroup test [25]. Osmolarity was calculated based on the reported constituent concentrations in the solutions (see Additional File 2: ORS compositions). We also examined the choice of model for sensitivity to the results. We performed intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. In addition, we created a more homogeneous failure definition post hoc and applied it to each article in order to check the robustness of the per protocol failure results. We identified and explored all statistical outliers.

We assessed publication bias visually using a funnel plot and quantitatively using the adjusted rank correlation test [26], the regression asymmetry test [27], and the trim and fill method [28] using Stata 7.0.

Results

Trial flow

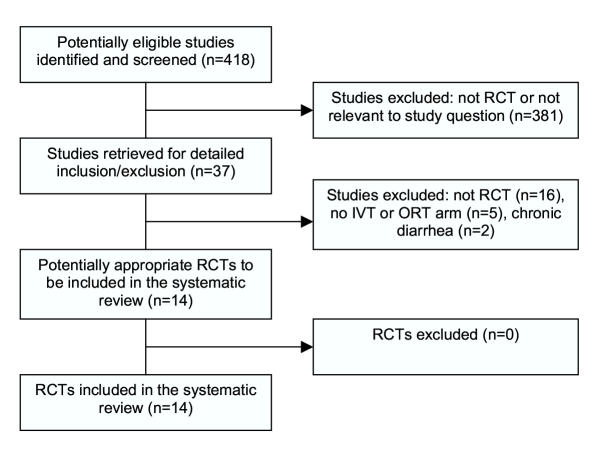

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of studies considered for inclusion in the review. 14 studies met the inclusion criteria [16,17,23,29-39]; one study stratified their data by two sites (USA and Panama) and we treated this as two studies in the quantitative analysis [23].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies considered for inclusion in the review. RCT, randomised controlled trial; IVT, intravenous therapy; ORT, oral rehydration therapy.

Study characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 describe the included studies (See Additional files 3 and 4, respectively). The average quality score was 2; allocation concealment was adequate in one study [39] and unclear in the others. Six studies received funding/sponsorship from the pharmaceutical industry [16,17,23,29,32,38]. One study received funding from other external sources [23]. Source of funding was not mentioned in the published version of the remaining studies. Though three studies [33,36,38] had incomplete follow up and one other [32] counted a withdrawal as a failure, none of the studies reported doing an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

Treatment failure

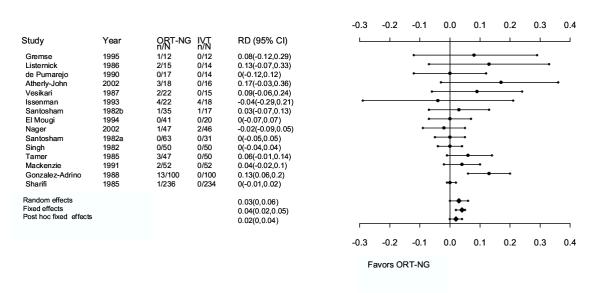

Based on a random effects (RE) model, there was no significant difference in failure to rehydrate (risk difference [RD] 3%; 95% CI: 0, 6; Table 3 [Additional File 5], Figure 2). The ORT failure risk was 4.6%; the IVT failure risk was 0.7%. The results for failure to rehydrate were sensitive to the choice of model. The fixed effects Mantel-Haenszel (FE-MH) model showed a significant risk difference in failure rate between treatment groups (RD 4%; 95% CI: 2, 5), favoring the IVT group (Table 3 [Additional File 5], Figure 2). Fixed effects inverse-variance method did not give a significant result.

Figure 2.

Metagraph for primary outcome (failure to rehydrate). Studies are arranged in order of increasing sample size. ORT-NG, oral rehydration therapy-nasogastric; IVT, intravenous therapy; RD, risk difference; CI, confidence intervals.

One study was a statistical outlier because its risk difference, given its sample size, was large (RD 13%; 95% CI: 6, 20; n = 200; Figure 2) [31]. Removing this study shifted the overall risk difference closer to the null (FE-MH RD 2%, 95% CI: 0.2, 4; NNT [number needed to treat] 50, 95% CI: 25, 1000). The heterogeneity in this model was reduced (P<0.001 vs. P = 0.213).

The definition of "failure" varied by study. We evaluated the sensitivity of a more homogeneous definition. We limited failures to the following: children with persistent vomiting; having some level of dehydration persisting; and experiencing shock or seizures. Children with paralytic ileus, intussusception, cerebral palsy, septicemia, urinary tract infection, and duodenal ulcer were excluded from this analysis. This post hoc failure definition was insignificant for both RE and MH-FE models (RD 2%; 95% CI: -0.1, 4; Table 3 [Additional File 5], Figure 2) and the heterogeneity was also reduced (P<0.001 vs. P = 0.108). Subsequently, subjects who had withdrawn or dropped-out were reclassified as failures, as in an ITT analysis. The FE-MH estimate for this model did show significant differences in failure rate between treatment groups, favoring the IVT group (RD 3%; 95% CI: 1, 5).

Deaths

Three studies reported deaths and supplemental data were obtained from a fourth author [33]. Singh reported that all patients were successfully rehydrated, however one patient succumbed to a "severe pyrogenic reaction" [35]. El-Mougi reported one death in the IVT group due to pneumonia and ileus [30]. Sharifi reported seven deaths: two in the ORT group and five in the IVT group [34]. The cause of death was not reported although four of the seven deaths occurred in patients below the third percentile weight class. Mackenzie reported no deaths [33]. All reported deaths occurred in low-middle income countries [40].

Other outcomes, complications, and adverse events

There were no differences between ORT and IVT for all secondary outcomes except length of stay and the occurrence of ileus and phlebitis (Table 3 [Additional File 5]). The ORT group had a shorter length of stay (WMD -1.2 days; 95% CI: -2.4, -0.02) although when the statistical outlier [31] was excluded, the result was no longer significant (WMD -0.3 days; 95% CI: -0.8, 0.08).

Since the individual study results were homogeneous for all complications and adverse events, these were assessed using the fixed effects model. There was insufficient data available to generate an adequate analysis of sodium levels.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Patient status (inpatient vs. outpatient), state of nourishment (well nourished vs. some malnourished), country's income (low-middle vs. high) [40], funding source (funded vs. not reported), allocation concealment (adequate vs. unclear), and Jadad scores were explored in meta-regression using failure to rehydrate as the dependent variable. All were found to be insignificant although the evidence for country's income was close to significance (P = 0.091); treatment differences in low-middle income countries may be smaller. The remaining a priori subgroup comparison results were not reported by subgroup (age, extent of dehydration) and could not be analyzed. Since the constant variance assumption was not met, we did not explore the post hoc osmolarity subgroups with meta-regression. Instead, we divided the trials into low osmolarity (range 208 to 270 mOsmol/L) and high osmolarity (range 299 to 331 mOsmol/L) subgroups; these cut-offs were similar to those used by Hahn et al [41]. The difference found by Deek's Chi-square subgroup test [25] was significant (P<0.0001) and favored the low osmolarity group. The RD for the low osmolarity group was 1% (95% CI: -1, 2) and it was homogeneous (P = 0.82); for the high osmolarity group, the RD was 4% (95% CI: 0, 8) and heterogeneous (P = 0.04). One study was found to be influential [31]; the one study that was quasi-randomised was not influential [35].

Post-hoc subgroup analyses examined exclusion of persistent vomiters as well as ORT route (NG vs. PO vs. a combination). Neither analysis showed significant differences.

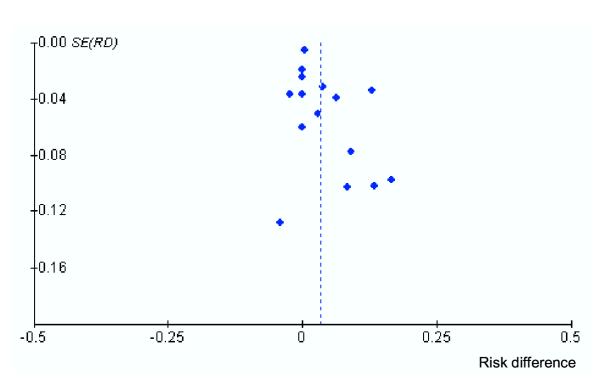

Publication bias

The regression asymmetry test suggested publication bias (P = 0.05, bias = 0.84); the adjusted rank correlation test was not significant (P = 0.11, r = 33). The trim and fill method indicated two missing studies; the adjusted overall effect size was not reduced. The funnel plot appears somewhat asymmetrical (Figure 3). A small amount of publication bias may be present suggesting that missing studies are more likely to favor ORT.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot based on primary outcome (failure to rehydrate). SE, standard error; RD, risk difference.

Discussion

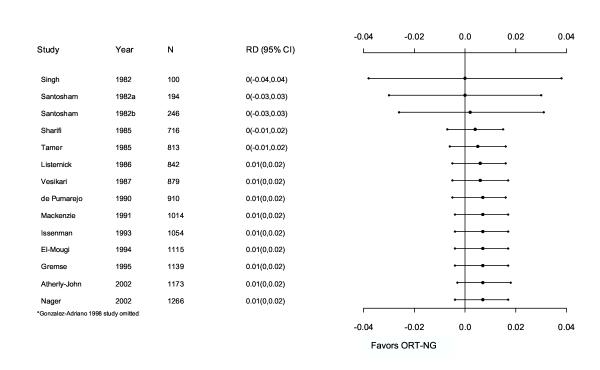

The most conservative model showed no important clinical differences between ORT and IVT in terms of safety and efficacy. For every 25 children treated with ORT, one would fail and require IVT. The results were consistent among different populations (e.g. state of nourishment) but further analyses are required for countries with different income levels. These results support existing practice guidelines recommending ORT as the first course of treatment in children with dehydration secondary to gastroenteritis. A cumulative metagraph (Figure 4), which adds studies by ascending year, shows that the overall estimate is unlikely to change substantially with further trials. Overall, more than 1400 children were studied providing adequate power to support the observed results.

Figure 4.

Cumulative meta-graph of studies comparing ORT versus IVT from 1982–2002. RD, risk difference; CI, confidence intervals; ORT-NG, oral rehydration therapy-nasogastric.

The median quality score according to the Jadad scale was two. Because it is impossible to double-blind studies on this topic, the quality of studies was limited to a maximum of three (rather than five). Therefore within this therapeutic approach, the studies represented reasonable quality. However it is important to note that studies that are not double blind can lead to an overestimate of the treatment effect [42] and that this is an inherent limitation in this literature. While double-blinding is probably not feasible in a trial comparing IVT and ORT, allocation can always be properly concealed. Allocation concealment was unclear in all but one study; this can lead to an overestimate of treatment effects by as much as 40% [22]. These factors could skew the results in favor of either ORT or IVT depending on the biases of the investigators.

In applying the evidence to clinical practice, the objective output of the meta-analysis must be weighed with other less easily measured factors that support the use of ORT. These include the amount of discomfort experienced by the child, the difference in treatment costs, and the amount of time and labor required to administer ORT. ORT is less invasive than IVT even when administered via NG [38]. ORT is less costly than IVT and can be administered as rapidly as IVT [38]. In addition, it can be administered by the child's caregiver and in a setting outside of the hospital. A recent RCT demonstrated that the use of ORT in a high-income country pediatric emergency department resulted in significantly lower costs, less time spent in the emergency department, and a more favorable impression of caregivers for this form of therapy [39].

Though there was no statistical heterogeneity between studies when the one outlying study [31] was omitted, there were important clinical variations. Rehydration was accomplished at different rates, by different routes, and with various solutions in different populations (Table 2 [Additional File 4] and Additional File 2). Comparisons of different oral rehydration solutions have been the subject of other reviews [41,43]. A meta-analysis comparing reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution (<270 mOsmol/l) with the standard solution (311 mOsmol/l) showed unscheduled intravenous infusion was significantly less in the reduced osmolarity group (odds ratio 0.59; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.79) [41]. The World Health Organization and UNICEF now recommend the reduced osmolarity solution. Our post-hoc analysis comparing low and high osmolarity solutions supported these findings.

Another source of variation was the definitions of "treatment failure" (Table 3 [Additional File 5]). We examined the effect of different failure definitions through a post hoc refined-definition analysis and found that it reduced heterogeneity and made our most conservative model insignificant. The ITT version of this model involved re-classifying seven ORT withdrawals as failures; this model was significant and favored IVT. If the seven withdrawals were systematically related to treatment benefit then this ITT analysis is less biased.

One study had a significantly greater failure rate [31]. The authors of the study attributed it to the fact that many of the children who failed were younger than six months of age. This study was the only one to include neonates. The authors argue that the burden of illness can be more severe in younger infants. Our data neither prove nor disprove this statement. When this study was removed from the analysis, the remaining study results were homogeneous and the overall risk difference shifted towards the null.

These results may not be generalizable to all children with dehydration secondary to gastroenteritis but only to those with dehydration secondary to diarrhea. A post-hoc look at studies with different inclusion criteria suggests that there may be an important difference in response to ORT among vomiters and non-vomiters. The risk difference for studies that excluded persistent vomiters was 1% (95% CI: -4, 6) compared to 4% (95% CI: -2, 10) in studies that did not exclude persistent vomiters. The issue of how vomiting affects the efficacy of ORT needs further study. However, in practice, treatment failure only means than one switches to IVT.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis clearly demonstrates that further RCTs for children with dehydration secondary to diarrhea are not warranted, or indeed, may be unethical to perform. Future research efforts in this area should focus on methods to improve the uptake of this effective and efficient intervention in both low- and high-income countries so children around the world can benefit from ORT.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

SB contributed to protocol development, literature searching, relevance screening of articles, assessment of study quality, data extraction, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. LH provided overall project coordination and contributed to protocol development, literature searching, relevance and inclusion screening of articles, assessment of study quality, data extraction, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. NW conducted the statistical analysis and contributed to the protocol development and manuscript preparation. KR contributed to relevance and inclusion screening of articles, data extraction and entry, and manuscript preparation. WRC contributed to protocol development, quality assessment, manuscript preparation and provided content expertise. DM contributed to protocol development, screening studies for inclusion, and reviewed the final manuscript. TPK contributed to protocol development and manuscript preparation and provided methodological and content expertise.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Search strategies. This file contains the detailed search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL (Cochrane Library).

Description of oral rehydration solutions. This table describes the oral rehydration solutions used in the included studies.

Study characteristics. This file presents Table 1 describing characteristics of the included studies. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; PO, orally; NG, nasogastric.

Study quality and definitions. This file presents Table 2 describing the methodological quality of the included studies and definitions used in the included studies. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; PO, orally; NG, nasogastric; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Comparison of ORT and IVT by outcome. This file presents Table 3 displaying the results of meta-analysis. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; RD, risk difference; WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Marlene Dorgan and Ellen Crumley for their assistance with literature searching. The Alberta Research Centre for Child Health Evidence is supported by an establishment grant from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

Contributor Information

Steven Bellemare, Email: sb6@ualberta.ca.

Lisa Hartling, Email: hartling@ualberta.ca.

Natasha Wiebe, Email: nwiebe@ualberta.ca.

Kelly Russell, Email: krussell@ualberta.ca.

William R Craig, Email: wcraig@cha.ab.ca.

Don McConnell, Email: DMcConne@cha.ab.ca.

Terry P Klassen, Email: terry.klassen@ualberta.ca.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Provisional committee on quality improvement, subcommittee on acute gastroenteritis, Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. Pediatrics. 1996;97:424–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armon K, Elliott EJ. Acute gastroenteritis. In: Moyer VA, editor. In Evidence based pediatrics and child health. London: BMJ Books; 2000. pp. 273–86. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (Child and Adolescent Health and Development) Child Health Epidemiology http://www.who.int/child-adolescent-health/overview/child_health/child_epidemiology.htm [Cited 2002 May 6]

- World Health Organization The challenge of diarrhoeal and acute respiratory disease control. In Point of Fact No 77 Geneva: World Health Organization. 1996. pp. 1–4.

- Duggan C, Santosham M, Glass RI. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: The management of acute diarrhea in children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1992;41:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin N, Merrick N, Davidson B. Efficacy of glucose-based oral rehydration therapy. Pediatrics. 1996;98:52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, the Bellagio Child Survival Study Group How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozuah P, Avner J, Stein R. Oral rehydration, emergency physicians, and practice parameters: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2002;109:259–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners GP, Barker WH, Mushlin AI, Goepp JGK. Oral versus intravenous: rehydration preferences of pediatric emergency medicine fellowship directors. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16:335–8. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis EC, Goepp JG, Katz S, Santosham M. Barriers to use of oral rehydration therapy. Pediatrics. 1994;93:708–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JD. Use and misuse of oral therapy for diarrhea: Comparison of US practices with American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations. Pediatrics. 1991;87:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santosham M. Oral rehydration therapy – Reverse transfer of technology (editorial) Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1177–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.12.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The treatment of diarrhea – a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. third. World Health Organization; 1995. Division of diarrheal and acute respiratory disease control. [Google Scholar]

- Garland JS, Dunne WM, Jr, Havens P, Hintermeyer M, Bozzette MA, Wincek J, Bromberger T, Seavers M. Peripheral intravenous catheter complications in critically ill children: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1145–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A, Barnes G. Oral rehydration in infantile diarrhoea in the developed world. Drugs. 1988;36:48–60. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198800364-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremse D. Effectiveness of nasogastric rehydration in hospitalized children with acute diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:145–8. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listernick R, Zieserl E, Davis AT. Outpatient oral rehydration in the United States. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:211–15. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140170037024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Library, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness Efficacy of glucose-based oral rehydration therapy. The Cochrane Library. 2002.

- Oxman A, Guyatt GH. Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1271–8. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90160-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen TP, Hartling L. In children with moderate dehydration, oral rehydration reduced ED stay and staff time compared with intravenous rehydration (see commentary) Evid Based Med. 2003;8:116. doi: 10.1136/ebm.8.4.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trial. JAMA. 1995;273:408–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santosham M, Daum RS, Dillman L, Rodriguez JL, Luque S, Russell R, Kourany M, Ryder RW, Bartlett AV, Rosenberg A, Benenson AS, Sack RB. Oral rehydration therapy of infantile diarrhea- a controlled study of well-nourished children hospitalized in the United States and Panama. NEJM. 1982;306:1070–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205063061802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Toronto: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editor. Systematic reviews in health care. 2. London, UK: BMJ Books; 2001. p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. British Medical Journal. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pumarejo MartinM, Lugo CE, Alvarez-Ruiz JR, Colon-Santinl JL. [Oral rehydration: experience in the mangerment of patients with acute gastroenterltis in the emergency room at the Dr. Antonio Ortiz pediatric hospital] Bol Asoc Med PR. 1990;82:227–33. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Mougi M, el-Akkad N, Hendawi A, Hassan M, Amer A, Fontaine O, Pierce NF. Is a low-osmolarity ors solution more efficacious than standard WHO ors solution? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;19:83–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Adriano SR, Valdes-Garza HE, Garcia-Valdes LC. Hidratacion oral versus hidratacion endovenosa en pacientes con diarrea aguda. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1988;45:165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issenman RM, Leung AK. Oral and intravenous rehydration of children. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:2129–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A, Barnes G. Randomised controlled trial comparing oral and intravenous rehydration therapy in children with diarrhoea. BMJ. 1991;303:393–96. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6799.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi J, Ghavami F, Nowrouzi Z, Fouladvand B, Malek M, Rezaeian M, Emami M. Oral versus intravenous rehydration therapy in severe gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:856–60. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.9.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Mahmoodi A, Arya LJ, Azamy S. Controlled trial of oral versus intravenous rehydration in the management of acute gastroenteritis. Indian J Med Res. 1982;75:691–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tamer AM, Friedman LB, Maxwell SRW, Cynamon HA, Perez HN, Cleveland WW. Oral rehydration of infants in a large urban U.S. medical center. J Pediatr. 1985;107:14–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesikari T, Isolauri E, Baer M. A comparative trial of rapid oral and intravenous rehydration in acute diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76:300–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1987.tb10464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nager AL, Wang VJ. Comparison of nasogastric and intravenous methods of rehydration in pediatric patients with acute dehydration. Pediatrics. 2002;109:566–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherly-John YC, Cunningham SJ, Crain EF. A randomized trial of oral vs intravenous rehydration in a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1240–3. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.12.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistics Division Economic Trade and Other Groupings of Countries or Areas New York, NY: United Nations Statistics Division [WWW Document] Accessed November 14, 2001.

- Hahn S, Kim S, Garner P. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for treating dehydration due to diarrhoea in children: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:81–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Miller JN, Mosteller F. How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy, I: medical. Stat Med. 1989;8:411–54. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine O, Gore SM, Pierce NF. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: 2000; Vol. 2. Oxford: Update Software; 2003. Rice-based oral rehydration solution for treating diarrhoea. CD001264 Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategies. This file contains the detailed search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL (Cochrane Library).

Description of oral rehydration solutions. This table describes the oral rehydration solutions used in the included studies.

Study characteristics. This file presents Table 1 describing characteristics of the included studies. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; PO, orally; NG, nasogastric.

Study quality and definitions. This file presents Table 2 describing the methodological quality of the included studies and definitions used in the included studies. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; PO, orally; NG, nasogastric; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Comparison of ORT and IVT by outcome. This file presents Table 3 displaying the results of meta-analysis. ORT, oral rehydration therapy; IVT, intravenous therapy; RD, risk difference; WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval.