Abstract

Postganglionic cardiac parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves are physically proximate in atrial cardiac tissue allowing reciprocal inhibition of neurotransmitter release, depending on demands from central cardiovascular centers or reflex pathways. Parasympathetic cardiac ganglion (CG) neurons synthesize and release the sympathetic neurotrophin nerve growth factor (NGF), which may serve to maintain these close connections. In this study we investigated whether NGF synthesis by CG neurons is altered in heart failure, and whether norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons promotes NGF synthesis. NGF and proNGF immunoreactivity in CG neurons in heart failure rats following chronic coronary artery ligation was investigated. NGF immunoreactivity was decreased significantly in heart failure rats compared to sham-operated animals, whereas proNGF expression was unchanged. Changes in neurochemistry of CG neurons included attenuated expression of the cholinergic marker vesicular acetylcholine transporter, and increased expression of the neuropeptide vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. To further investigate norepinephrine’s role in promoting NGF synthesis, we cultured CG neurons treated with adrenergic receptor (AR) agonists. An 82% increase in NGF mRNA levels was detected after 1hr of isoproterenol (β-AR agonist) treatment, which increased an additional 22% at 24hr. Antagonist treatment blocked isoproterenol-induced increases in NGF transcripts. In contrast, the α-AR agonist phenylephrine did not alter NGF mRNA expression. These results are consistent with β-AR mediated maintenance of NGF synthesis in CG neurons. In heart failure, a decrease in NGF synthesis by CG neurons may potentially contribute to reduced connections with adjacent sympathetic nerves.

Keywords: Nerve Growth Factor, Heart Failure, Autonomic, Cardiac Ganglion, Adrenergic Receptor, Parasympathetic

1. Introduction

Postganglionic cardiac parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves normally interact reciprocally in modulating heart rate, and presynaptic norepinephrine (NE) release by sympathetic nerves, or acetylcholine (ACh) release by parasympathetic nerves, are important regulatory mechanisms for heart rate control in the effector pacemaker and conduction regions (Levy, 1990; Loiacono et al., 1986; Vanhoutte et al., 1980; Wetzel et al., 1985; Yang et al., 1992). With the progression of congestive heart failure (CHF), however, autonomic disturbances occur including sympathetic overactivity and reduced vagal tone (Bibevski et al., 2011; Binkley et al., 1991; Dunlap et al., 2003; Eckberg et al., 1971; Kinugawa et al., 1995; Ondicova et al., 2010; Porter et al., 1990; Ramchandra et al., 2009). Functionally, sympathetic nerves in CHF convert from a balanced NE synthesis, release, re-uptake system to one that predominantly releases NE, resulting in excessive myocardial stimulation (and eventual fatigue) and catecholamine toxicity (Backs et al., 2001; Bohm et al., 1995; Kreusser et al., 2008). Reduced vagal activity in CHF has been correlated with attenuated heart rate variability and therefore elevated risk of sudden cardiac death (La Rovere et al., 1998; Lechat et al., 2001; Lombardi et al., 1998). Attenuated vagal tone may also manifest as reduced cardiac postjunctional innervation that will result in fewer inhibitory connections on co-projecting sympathetic fibers (Azevedo et al., 1999; Bibevski et al., 2011; Deneke et al., 2011; Du et al., 1990; Dunlap et al., 2003; Nihei et al., 2005).

The mechanism for altered autonomic axo-axonal communication in heart failure is unclear. However in control rats, parasympathetic cardiac ganglion (CG) neurons synthesize the neurotrophin nerve growth factor (NGF) (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009); since the mature NGFβ moiety exerts a powerful trophic effect on sympathetic neurons, its release from CG neurons may be critical for maintaining axo-axonal appositions and hence for maintaining parasympathetic inhibition of sympathetic function in CHF. In turn, impulse activity from sympathetic neurons promotes NGF synthesis by CG neurons (Hasan et al., 2009). In contrast to mature NGFβ, the precursor pro-form of NGF (proNGF) is involved in promotion of nerve pruning, degeneration and apoptosis of sympathetic neurons (Al-Shawi et al., 2008; Bierl et al., 2007; Lobos et al., 2005), and proNGF expression by CG neurons is not directly regulated by adjacent sympathetic nerve impulse activity (Hasan et al., 2009). The relative expression of NGFβ to proNGF may determine the extent of sympathetic-parasympathetic axo-axonal associations in CHF; evaluating NGFβ and proNGF protein expression in CG neurons from CHF rats is therefore a central focus of this study.

Although we have previously shown that impulse activity, and not physical presence of sympathetic nerves, is necessary for regulating NGF synthesis by parasympathetic nerves (Hasan et al., 2009), whether NE is directly responsible has not been determined. In several cell types, activation of adrenergic receptors (ARs), primarily β-ARs, has been shown to augment NGF synthesis (Carswell et al., 1992; Colangelo et al., 1998; Colangelo et al., 2004; Culmsee et al., 1999; Dal Toso et al., 1988; Hayes et al., 1995; Samina Riaz et al., 2000; Semkova et al., 1996). We hypothesize that adrenergic heteroreceptors on CG neurons will similarly promote NGF synthesis. We therefore evaluate, in an in vitro CG dissociated neuronal system, the effects of adrenergic agonists on NGF synthesis by CG neurons.

In addition to regulating NGF expression, we have previously shown that another consequence of cardiac sympathectomy is a decrease in the cholinergic phenotype of rat CG neurons (Hasan et al., 2009). We propose that reduced cross-talk between autonomic neurons in CHF will similarly promote alterations in the neurochemistry of CG neurons from CHF animals. We examine therefore cholinergic, peptidergic and adrenergic markers in CG from CHF animals.

Together these studies attempt to identify alterations in NGF expression and neurochemistry within CG neurons from heart failure rats. The role of AR-mediated mechanisms in regulating NGF synthesis by CG neurons is also evaluated. Understanding the mechanisms involved in disruption of cardiac autonomic nerve interactions is crucial for future development of targeted therapies to reverse dysfunctional autonomic activity in the progression of CHF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Coronary artery ligation

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (60–70 days postnatal, ~225g, Harlan Breeding Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg/kg ketamine, 8 mg/kg xylazine, and 0.4 mg/kg atropine. Rats were intubated, respired mechanically, and a left lateral thoracotomy performed as in our previous studies (Hasan et al., 2006; Wernli et al., 2009). The left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated (6-0 silk suture with an atraumatic needle) approximately 8 mm distal to its emergence beneath the left atrium (n=20) (Hasan et al., 2006; Wernli et al., 2009). This elicited a visible infarct corresponding to the ischemic region of the myocardium in the coronary artery ligation (CAL) group. Sham surgery (SHAM, n=21) involved similarly passing a suture around the artery but leaving it untied for a comparable period. The incision was closed with 4-0 suture and the animals allowed to recover. After 15±2 weeks, a subgroup of rats (n=7) underwent in vivo hemodynamic measurements while the rest of the animals were sacrificed for tissue harvest under pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia. All experimental manipulations were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center and conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (8th edition, revised 2011).

2.2 In vivo hemodynamics

A subset of rats (see Table 1) were anaesthetized (1.5g/kg urethane, i.p) and the cervical right carotid artery exposed prior to its rostral bifurcation. An intraventricular conductance catheter (SPR-838, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX), sensitive to pressure and volume, was inserted from the right carotid artery into the left ventricle and pressure-volume recordings made using PowerLab with LabChart software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). A femoral artery was cannulated for measuring blood pressure and heart rate (HR) using a blood pressure transducer (MLT0699, ADInstruments). Body temperature was monitored using a rectal probe and digital monitor (BAT-12, Physitemp, Clifton, NJ), and maintained at 37°C using a heating pad.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic measurements from rats following coronary artery ligation (CAL) or sham surgery.

| BL HR (bpm) | MAP (mmHg) | SP (mmHg) | PP (mmHg) | EF (%) | Ea mmHg/μl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM (n=10) | 278±15(10) | 82±1(10) | 113±2(10) | 47±3(10) | 100±1(n=5) | 1.21±0.16(n=4) |

| CAL (n=10) | 274±11(10) | 71±6(10)* | 93±7(10)* | 34±3(10)* | 69±2(n=3)* | 2.51±0.41(n=3)* |

Resting heart rate (RHR), mean arterial pressure (MAP); systolic pressure (SP); pulse pressure (PP); ejection fraction (EF); arterial elastance (Ea). Data are mean ±SEM, n in parenthesis;

<0.05.

2.3 Immunohistochemistry

The base of the heart including atria and major cardiac vessels, which includes the cardiac ganglia, was removed, embedded in tissue freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, NC, USA), frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C. Sets of 15μm sections perpendicular to the basal-apical axis of the atria were collected as consecutive sections onto 5 slides as a stepped series. Sections were collected beginning ~2 mm superior from the point of entry of the aorta into the heart and continued until at least two cardiac ganglia had been identified under differential interference microscopy and completely sectioned. Ganglia were generally identified in epicardial fat pads or embedded within the atrial walls. Sections were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by 90 min incubation with cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies as previously (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009). Combinations of primary and secondary antibodies were evaluated to exclude the possibility of antibody cross-reactivity. Antibodies were raised against the cholinergic marker vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT, goat IgG, 1:100, Chemicon), the adrenergic marker vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT, rabbit IgG, 1:100, Chemicon), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP, rabbit IgG, 1:250, Immunostar), proNGF (rabbit IgG, 1:100, Chemicon) and mature NGFβ (rabbit IgG, 1:100, Santa Cruz). Antibody omission, pre-adsorption to the relevant antigen, and substitution of naïve immunoglobulin for the primary antibody served as negative controls.

2.3.1 Quantitation of immunoreactive neurons

Within every 2nd section in one stepped series through the entire ganglion, all neurons displaying immunofluorescence and a nucleus whose uppermost membrane boundary was contained within the section, were counted and divided by the total number of neuronal nuclei in that section. Total neuron counts per ganglion within sampled sections ranged from 50–250 neurons. Percentages of stained neurons were averaged to obtain a mean value per ganglion (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009). All data are expressed as means ±SEM. Comparisons were performed by Student’s t-tests (SHAM vs. CAL groups, significance at p<0.05).

2.4 Cardiac Ganglion cultures

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (21 days post natal, Harlan Breeding Laboratories, n=6 rats per culture, data from 5 separate cultures) were anesthetized with Beuthanasia-D (0.2ml kg−1, Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ). The heart and major blood vessels were removed and placed in HBSS medium (Ca/Mg free, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Tissue was cut into 1mm saggital slices with a rat brain slicer (Zivic, Pittsburgh, PA) and CG isolated under a dissecting scope from cardiac tissue, particularly from around the entrance of the superior vena cava into the base of the heart. Tissue was enzymatically digested with a collagenase-dispase solution in HBSS (collagenase type 1a, 1mg/ml, Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ; 5 Units Dispase, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 30min at 37°C then triturated in Neurobasal A medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with fine-bore Pasteur pipettes. After filtering the cell suspension (40μm cell strainer, BD Biosciences) cells were plated onto 48-well matrigel-coated plates (100μl per plate) and incubated in Neurobasal A medium (200μl per plate, plus glutamine (0.5mM), B27 (0.4μl/ml), and primocin antibiotic (0.1mg/ml), InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) at 37°C in 95% air, 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 24h, medium was changed with Neurobasal A plus the mitotic inhibitor cytosine arabinoside (10mM, Sigma-Adrich) for the next 24h only. Forty-eight hours after the start of the culture, cells were treated with adrenoceptor agonist, or antagonist followed by agonist (60 min later), or Neurobasal A medium alone; RNA was isolated 1h or 24h after start of treatment (all treatments in triplicate). RNA was isolated by washing cells with Neurobasal A medium then adding 500μl TRIzol (Life Technologies) per well for 5min; RNA purification was per TRIzol manufacturer’s instructions. A subset of wells was processed for immunocytochemistry (see below).

Adrenoceptor agonists/antagonists were: Isoproterenol (β-adrenergic agonist, 1μM), Propanolol (β-adrenergic antagonist, 10μM), Phenylephrine (α-adrenergic agonist, 1μM), and Phentolamine (α-adrenergic antagonist, 10μM); all drugs from Sigma-Aldrich).

2.5 Immunocytochemistry

Wells from untreated CG cultures (see above, n=6 wells per antibody) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (60min) then immunostained (see immunohistochemistry section) with peripherin (cy3, red), or double immunostained for the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (PGP, cy2, green) and the cholinergic marker VAChT (cy3, red) or for VAChT alone. The number of peripherin or PGP-immunoreactive neurons was quantitated per well and numbers of neurons were similar between wells (data not shown). To confirm that CG neurons in culture retain a cholinergic phenotype in culture, the percentage of VAChT-immunoreactive neurons was quantitated and data compared with in vivo sectional staining data from control rats and with both in vivo (sectional percentage) and in vitro (dissociated culture) data from the parasympathetic pterygopalatine ganglion (n=9 wells from 2 separate cultures for in vitro data, n=4 rats for in vivo data) cultured with an identical protocol to that of CG neurons.

2.6 Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from cardiac ganglia cell lysates was quantitated and qualitated with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Quantum Analytics, Foster City, CA) with RNA6000 Pico kit (RNA integration number greater than 8 for downstream processing). Fifty nanograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed (BioRad iscript cDNA synthesis kit, BioRad, Hercules, CA) utilizing manufacturer’s instructions in an MJ Mini thermal cycler (BioRad) with rat heart total RNA (Life Technologies) as positive and negative (no transcriptase) control. The cDNA was diluted to 1:4 for a final estimated cDNA concentration of 0.625ng/μl and PCR products were synthesized with the SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) and were analyzed in real time with the detection system (iCycler iQ real-time cycler, BioRad) in triplicate. Each 25μl SYBR Green reaction contained 1μl cDNA, 0.3 μM forward primer and 0.3 μM reverse primer. For amplification of both NGF and the reference gene GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase), the following PCR protocol was applied: 95°C for 3min (initial denaturing), followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturing), 55°C for 1min (annealing) and completed with a dissociation step for melting point analysis with 95°C for 1min, 60°C for 1min and 80 cycles of 60°C to 100°C (in increments of 0.5°C) for 10 seconds. Primers utilized for the real-time reaction were, for NGF, forward: 5′-ATGGTACAATCTCCTTCAAC′-3′ and reverse 5′-GGCTGTGGTCTTATCTCC-3′, and for GAPDH, forward: 5′CTCTACCCACGGCAAGTT-3′ and reverse: 5′CTCAGCACCAGCATCACC-3′ (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

2.6.1 Primer efficiency

Standard curves for NGF and GAPDH were prepared with serial dilutions of rat heart cDNA (1:1=2.5ng/μl; dilutions of 1:4 to 1:1024) in triplicate to determine the percentage efficiency for each amplification. Cycle numbers were plotted against the fluorescence intensity to visualize the PCR amplification. Standard curve regression lines and slope from serial dilution data showed high primer efficiencies for both NGF (98.7%) and GAPDH primers (107%), and with high linearity (Pearson Correlation coefficient r2 =0.98 for NGF, and 0.99 for GAPDH; n=4 runs). Therefore, the amplification efficiencies for the target and reference gene were within the range (90–100%) needed for utilization of the ΔΔCT method for quantification purposes (Livak and Schmittgen 2001, Pfaffl, 2001). Dissociation (melting) curves showed a single-product melting at 85 C for NGF and 86.5 C for GAPDH. Single peaks illustrated that only one product was formed, and the lack of any other peaks illustrated that the primers did not form primer dimers.

Data are expressed as an n-fold change in gene expression (2(−ΔΔCT) normalized to the reference gene GAPDH and expressed as fold change relative to control untreated neurons. Analysis by two-way ANOVA (treatment, time) and one-way ANOVA (per time point, Kruskal-Wallis test), and post-hoc analysis by the Student-Newman-Keuls or Dunn’s method respectively (SigmaStat, Systat Software).

3. Results

3.1 Hemodynamic measurements

We assessed cardiac performance in rats with and without coronary artery ligation to determine whether infarction in our model produced changes consistent with HF. Resting heart rate, measured while rats were anesthetized but otherwise unperturbed, was comparable in both ligated and sham-operated subjects (Table 1). Mean arterial pressure, systolic pressure and pulse pressure were all reduced in ligated relative to sham-operated rats (p<0.05, Table 1). Ejection fraction, recorded during pressure-volume loop measurements, was divided by the mean of the sham group to provide the normalized ejection fraction; this was reduced in rats receiving coronary artery ligation relative to sham-operated rats (p=0.013, Table 1). Arterial elastance (Ea) was increased in ligated animals (p=0.022, Table 1); however, ventricular elastance (Ees) was not significantly different between groups and the Ea/Ees ratio did not therefore change (data not shown).

3.2 Cardiac ganglia nerve growth factor expression is reduced in CHF

Percentage of proNGF immunoreactive neurons was 38% (Fig. 1A–E) in CG from SHAM rats, and was similar in CG from CAL rats (Fig. 1C–E). Immunoreactivity for mature NGFβ in SHAM rats was present within a similar percentage of CG neurons (42%, Fig. 1B, E) to that of the pro-form, and appeared to be expressed in a similar population of neurons. In contrast to proNGF immunoreactivity, NGFβ-immunoreactivity in CG from CAL animals was reduced by 34% (Fig. 1D, E; p=0.001). Our data suggest that the NGFβ-proNGF ratio may be tilted towards proNGF in CG from CHF rats.

Figure 1.

ProNGF (A, C) and NGFβ (B, D) immunoreactive neurons in cardiac ganglia from rats after coronary artery ligation (CAL) or sham surgery. ProNGF immunoreactivity (-ir) was prominent within neuronal soma (white arrowheads; A, C), nerve bundles (nb; B) and vascular smooth muscle (v; C). Percentage of proNGF-ir neurons was stable between groups (E). NGFβ-ir was prominent in cardiac ganglia from sham rats (B, white arrowheads); however after CAL, NGFβ-ir was present in fewer neurons with most not displaying NGFβ-ir (grey arrowheads; 34% reduction, p=0.001, D, E). Data are mean ±SEM, ***p<0.001. Scale bar in D= 40μm for all panels.

3.3 Cholinergic phenotype is altered in CHF cardiac ganglia

Immunoreactivity for the cholinergic marker vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) was present within the majority (60%) of CG neurons from SHAM rats (Fig. 2A, G). In CAL rats, a 22% reduction in VAChT-ir neurons was observed (Fig. 2B, G; p<0.0001). In contrast, VIP-ir neurons were present in 31% of SHAM CG, and increased by 47% in CAL rats (Fig. 2C, D, G; p=0.04). The catecholaminergic marker vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT) was expressed by a small but significant proportion (32%) of CG neurons from SHAM animals and this percentage was unaltered in CAL rats (Fig. 2E–G).

Figure 2.

VAChT (A, B), VIP (C, D) and VMAT (E, F) immunoreactive neurons in cardiac ganglia (CG) from rats after coronary artery ligation (CAL) or sham surgery. Cytoplasmic VAChT immunoreactivity (-ir) was strong in 60% of CG neurons (white arrowheads, A). Following CAL, VAChT-ir was less prominent (grey arrowheads= negative neurons, B; 22% reduction, E). VIP-ir was present in a small subpopulation of CG neurons; after CAL, the percentage of VIP-ir neurons increased by 47% (D, E; p=0.04). VMAT-ir was observed in nerve fibers (E, arrows) and a small subpopulation of CG neuronal soma (32%, E, G) in sham rats; this percentage did not significantly alter after CAL (F, G). Data are mean ±SEM, *<0.05, ***p<0.001. Scale bar in D= 50μm for all panels.

3.4 Cultured cardiac ganglia

Cultured neurons from control rats, both from the CG (Fig. 3A, peripherin-stained), and from the model parasympathetic ganglion, the pterygopalatine ganglion (PPG) (Fig. 3B, PGP9.5-stained), formed small groups of microganglia and elaborated multi-length neurites containing growth cones and terminal boutons. CG (Fig. 3C) and PPG (Fig. 3D) neurons were stained with VAChT and immunoreactivity was observed to be prominent within cultured neurons. Quantitation of immunoreactive neurons showed a similar proportion of VAChT immunoreactivity in CG neurons in vitro and in vivo (60–61%, Fig. 3E). A similar percentage of PPG neurons displayed VAChT immunoreactivity (59%, Fig. 3E) to that observed for CG in vivo, and this percentage was not different in either tissue sections or in cultured neurons (Fig. 3D, E).

Figure 3.

VAChT immunoreactivity (-ir) in cultured parasympathetic cardiac ganglion (CG; A, B) and pterygopalatine (PPG; C, D) neurons. CG neurons in vitro stained strongly in neuronal soma (arrowhead) and neurites for the pan-neuronal marker peripherin (A) and VAChT (B), VAChT-ir being prominent in 60% of neurons, very similar to that in vivo (E). Cultured PPG neurons stained strongly in neuronal soma (arrowhead) and processes for both the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (PGP; C) and VAChT (D) with a similar percentage (59%) to that in vivo (E) and to that in CG neurons. Data are mean ±SEM. Scale bar in D= 40μm for all panels.

3.5 Adrenergic receptor agonists increase nerve growth factor synthesis by cardiac ganglion neurons in vitro

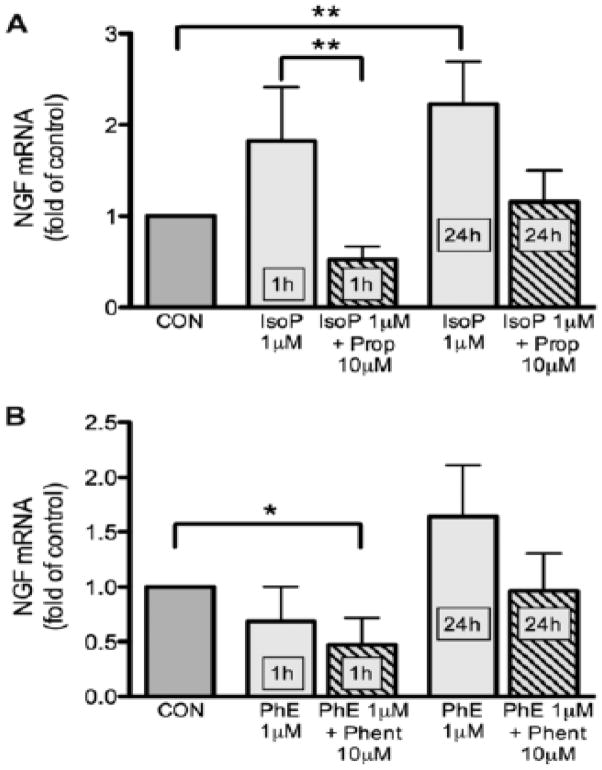

With qRT-PCR we determined NGF transcript expression in cultured CG neurons treated with adrenoceptor agonists. Treatment of CG neuronal cultures with the β-adrenoceptor agonist isoproterenol (1μM) increased NGF transcript expression by 82% over control wells after 1h (p=0.0084); this increase in NGF transcripts was maintained over 24h (123% increase over control wells, p=0.0014, Fig. 4A). Parallel wells were also treated with 0.1μM and 10μM isoproterenol; however, the agonist effect was clearest at 1μM, hence only these data are shown. In contrast, the α-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine (1μM) did not significantly alter NGF transcript expression after 1h or 24h of treatment (Fig. 4B). Addition of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol (10μM) blocked the isoproterenol-induced increase in NGF mRNA (Fig. 4A), while phentolamine-treated wells (10μM) were similar to phenylephrine-only treated wells (Fig. 4B). In summary, the β-adrenoceptor agonist, but not the α-adrenoceptor agonist, increased NGF transcript expression by CG neurons compared to untreated control CG neuron wells.

Figure 4.

NGF mRNA quantitation in cardiac ganglion neurons after adrenergic agonist treatment. For isoproterenol (IsoP; A), a significant increase (p<0.01) over control levels was seen after 1 and 24 hr of treatment that was blocked by propranolol (Prop). In contrast, neither 1 nor 24 hr treatment with phenylephrine (PhE) altered NGF transcript expression over controls (B). Data are mean ±SEM, *<0.05, ***p<0.001.

4. Discussion

As heart failure progresses, overactive sympathetic drive is accompanied by attenuated vagal tone. At the level of the effector organ, the parasympathetic system normally dampens sympathetic activity through prejunctional inhibition; however, this ability is compromised in heart failure. A mechanism for maintaining sympathetic-parasympathetic appositions in the adult heart is likely through paracrine release of NGF by parasympathetic neurons (Hasan et al., 2009); whether CG NGF levels are altered in the failing heart was a central question in this study. We also sought to determine if NGF synthesis by cardiac ganglion neurons was promoted by a direct effect of sympathetic agonists. To examine these questions, we utilized a well-established model of chronic coronary artery ligation for induction of myocardial infarction and CHF that we have previously characterized (Clarke et al., 2010; Donohue et al., 2009; Hasan et al., 2006). Previous studies (Clarke et al., 2010; Hasan et al., 2006) show post-infarction morphological changes in ligated animals, including fibrosis and scarring, ventricular wall thinning, and ventricular enlargement. In our model we observed significant decreases in mean arterial pressure, pulse pressure, and systolic pressure, as well as reduced ventricular ejection fraction similar to those reported previously (Henze et al., 2008; Henze et al., 2013; Kruger et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997; Mulder et al., 2004). Despite reduced arterial pressure, the arterial elastance was increased in our rats consistent with increased stiffness and therefore reduced arterial contractility. Our studies are therefore conducted in a validated model of CHF following chronic coronary artery ligation.

Since NGF from cardiac ganglion neurons is believed to be responsible for maintaining axo-axonal appositions with sympathetic neurons, we reasoned that, in heart failure, NGF expression might be altered. With quantitative immunohistochemistry studies, we sought to determine NGFβ and proNGF expression in cardiac ganglia from CHF rats. We demonstrated reduced sectional percentage of NGFβ in CHF cardiac ganglia although proNGF expression was stable. As a generalized phenomenon in CHF, NGF protein expression is decreased in ventricles resulting in reduced trophic support for sympathetic neurons (Kaye et al., 2000; Kreusser et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2002). ProNGF has been shown to promote degeneration of sympathetic axons in the relative absence of the mature form (Al-Shawi et al., 2008; Bierl et al., 2007; Lobos et al., 2005). A reduction in the mature NGF form, accompanied by stable levels of the pro form, would potentially decrease sympathetic-parasympathetic appositions in the failing heart. The consequent lack of parasympathetic inhibitory control over NE release from sympathetic terminals would likely promote the detrimental excessive NE release reported in experimental and clinical CHF.

Although reduced NGFβ expression in CG neuronal soma may reflect reduced NGF synthesis, it is also possible that NGFβ is transported at higher rates to nerve terminals in CHF. Although we have no direct evidence for increased NGFβ transport in CHF, since proNGF is the predominant NGF isoform expressed in the heart (Bierl et al., 2005), any decrease in NGFβ, either from reduced intracellular cleavage or increased transport, would probably not substantially impact overall proNGF levels. Indeed, in a previous study we showed that decreased NGF transcripts in CG neurons after cardiac sympathectomy correlated with similar declines in NGFβ protein, whereas proNGF expression remained stable (Hasan et al., 2009). Although we have not examined atrial innervation in this study, decreases in parasympathetic markers, and increases in sympathetic markers, have been reported by others (Lund et al., 1983; Ng et al., 2011; Roskoski et al., 1975; Xu et al., 2006). However, depending on the model, regional variations in innervation patterns are observed for both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Future studies directed at examinations of sites for terminal NGF release will indicate how this regional heterogeneity in cardiac autonomic patterning in heart failure occurs.

Our data from NGF expression in cardiac ganglia are consistent with a lack of crosstalk between parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons in heart failure. We have previously shown that sympathetic neurons have a critical role in promoting NGF synthesis by parasympathetic neurons. Indeed, neurochemical transmission, not physical presence of sympathetic axons, is key to increased NGF expression by these neurons (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009). Changes in NGFβ and proNGF within CG neurons from CHF rats in our study are similar to those observed after sympathectomy, suggesting a common mechanism at play. Whereas after sympathectomy, sympathetic activity is decreased, an interesting contrast with heart failure is that overall sympathetic activity is actually increased in this pathological state. As such, we were curious as to possible mechanisms for regulation of NGF synthesis in cardiac ganglion neurons. Since ARs are expressed by CG neurons, we investigated the effect of adrenergic agonists on NGF synthesis by CG neurons in dissociated cell culture. Our results indicate that β-ARs, but not α-ARs, promote NGF synthesis from CG neurons in culture. The presence of AR heteroreceptors on CG neurons has been previously reported (Ishibashi et al., 2003; Xu et al., 1993); however, this is the first report of a role for these receptors in regulating NGF synthesis in these neurons. ARs promote NGF synthesis in various cell types (Carswell et al., 1992; Colangelo et al., 1998; Colangelo et al., 2004; Culmsee et al., 1999; Dal Toso et al., 1988; Hayes et al., 1995; Samina Riaz et al., 2000; Semkova et al., 1996). Intriguingly, while β-ARs have been shown to promote NGF expression, α-AR stimulation may promote an attenuation of NGF in the heart (Kimura et al., 2010; Qin et al., 2002). Our data are therefore consistent with previous findings, in that adrenergic agonists promote NGF synthesis; however, this is the first demonstration of such a phenomenon in a parasympathetic neuronal population.

With regard to timeline, it appears quite clear that β-AR-mediated increases in NGF transcripts occur very rapidly, similar to observations in other cell types (Dal Toso et al., 1988; Furukawa et al., 1989; Samina Riaz et al., 2000), and that this augmentation in NGF is maintained over 24h treatment in culture. These data are consistent with dynamic changes in neurotrophin expression by CG neurons in response to adrenergic agonists, and suggest that rapid re-modeling of sympathetic nerves occurs in pathological states such as heart failure. A limitation of the current study is that we have not examined the effect of adrenergic agonists on NGF expression by CG neurons from heart failure rats. From a clinical standpoint, treating with catecholamines or sympathetic agonists may not be ideal however as increased catecholamine release in heart failure is detrimental to cardiac function. Whether any alterations occur in AR expression on CG neurons as heart failure progresses remains to be determined. However, we do have preliminary data from a microarray study on CG neurons suggesting that β-AR transcripts are decreased and adrenergic receptor kinase β1 (BARK1) expression increased in CG neurons from heart failure rats (unpublished). These preliminary data are consistent with β-AR downregulation and desensitization in CHF, which would certainly promote attenuated NGF synthesis by CG neurons in heart failure.

If crosstalk between autonomic neurons is disrupted in heart failure due to attenuated NGF release from CG neurons, does this result in any functional consequences for parasympathetic neurons? In previous studies where cardiac sympathectomy was carried out, the cholinergic marker VAChT was decreased in CG neurons (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009) suggesting a crucial role for sympathetic neurons in maintaining parasympathetic phenotype. Similarly, we now report that in CHF, a decrease in VAChT expression also occurs. Since cardiac sympathetic drive is increased in CHF, decreased parasympathetic VAChT expression may appear somewhat counterintuitive. However, we suspect that due to reduced NGFβ release from parasympathetic terminals, crosstalk between cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic nerves may be attenuated, resulting in suboptimal parasympathetic neurochemistry.

In contrast to VAChT expression, VIP expression in CG neurons was augmented following CAL. Given that a decrease in parasympathetic cholinergic function may occur in CHF as evidenced by the decline in VAChT, it is possible that increased VIP further exacerbates the cardiac overload in CHF, as this peptide is known to promote tachycardia (Hill et al., 1995; Markos et al., 2006). Whether VIP-promoting tachycardia occurs in heart failure remains to be determined; however our data point to an interesting avenue for future research. A subpopulation of CG neurons express the adrenergic marker VMAT; however, we have previously shown that these are a subpopulation of cholinergic parasympathetic neurons that do not display catecholamine histofluorescence and therefore are not regarded as true catecholaminergic neurons (Hasan et al., 2000; Hasan et al., 2009). In CG from CHF rats, VMAT expression was unchanged (similar to tyrosine hydroxylase expression, data not shown) compared to sham-operated animals. In our model, therefore, catecholaminergic traits in CG neurons are stable and contrast with sympathetic neurons that acquire cholinergic traits in CHF, while adrenergic traits decrease (Kanazawa et al., 2010). Although mechanisms for phenotypic changes may differ from that in sympathetic ganglia, it is evident that adult CG neurons also have the ability to respond to pathological states like heart failure with demonstrable alterations in their neurochemical profile.

In summary, we provide evidence demonstrating a β-AR mediated increase in NGFβ expression within parasympathetic CG neurons. We also show that, in heart failure, autonomic crosstalk impairment may be facilitated by reductions in NGFβ expression by CG neurons. Lack of input from sympathetic neurons may also be responsible for alterations in CG neurochemistry in heart failure rats. Together, these data suggest that therapies directed towards increased cardiac parasympathetic tone (Li et al., 2004; Sabbah, 2011; Sabbah et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2009) may be beneficial through normalization of crosstalk between sympathetic and parasympathetic postganglionic nerves.

Acknowledgments

We thank Clark Bloomer and the Genome Sequencing Facility at KUMC for technical support with RNA Bioanalyzer analysis. We also acknowledge Dr. Timothy Donohue for help with the hemodynamic studies. This work was supported by NIH HL079652 (PGS).

Abbreviations

- CG

Cardiac Ganglion

- NGF

Nerve Growth Factor

- AR

Adrenergic Agonist

- NE

Norepinephrine

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- CHF

Congestive Heart Failure

- CAL

Coronary Artery Ligation

- HR

Heart rate

- VAChT

Vesicular Acetylcholine Transporter

- VMAT

Vesicular Monoamine Transporter-2

- VIP

Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate

- IsoP

Isoproterenol

- Prop

Propranolol

- PhE

Phenylephrine

- Phent

Phentolamine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Shawi R, Hafner A, Olsen J, Chun S, Raza S, Thrasivoulou C, Lovestone S, Killick R, Simons P, Cowen T. Neurotoxic and neurotrophic roles of proNGF and the receptor sortilin in the adult and ageing nervous system. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2103–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo ER, Parker JD. Parasympathetic control of cardiac sympathetic activity: normal ventricular function versus congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1999;100:274–279. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs J, Haunstetter A, Gerber SH, Metz J, Borst MM, Strasser RH, Kubler W, Haass M. The neuronal norepinephrine transporter in experimental heart failure: evidence for a posttranscriptional downregulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:461–472. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibevski S, Dunlap ME. Evidence for impaired vagus nerve activity in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierl MA, Isaacson LG. Increased NGF proforms in aged sympathetic neurons and their targets. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierl MA, Jones EE, Crutcher KA, Isaacson LG. ‘Mature’ nerve growth factor is a minor species in most peripheral tissues. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkley PF, Nunziata E, Haas GJ, Nelson SD, Cody RJ. Parasympathetic withdrawal is an integral component of autonomic imbalance in congestive heart failure: demonstration in human subjects and verification in a paced canine model of ventricular failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:464–472. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm M, La Rosee K, Schwinger RH, Erdmann E. Evidence for reduction of norepinephrine uptake sites in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:146–153. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00353-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell S, Hoffman EK, Clopton-Hartpence K, Wilcox HM, Lewis ME. Induction of NGF by isoproterenol, 4-methylcatechol and serum occurs by three distinct mechanisms. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;15:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GL, Bhattacherjee A, Tague SE, Hasan W, Smith PG. β-adrenoceptor blockers increase cardiac sympathetic innervation by inhibiting autoreceptor suppression of axon growth. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12446–12454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1667-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo AM, Johnson PF, Mocchetti I. beta-adrenergic receptor-induced activation of nerve growth factor gene transcription in rat cerebral cortex involves CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10920–10925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo AM, Mallei A, Johnson PF, Mocchetti I. Synergistic effect of dexamethasone and beta-adrenergic receptor agonists on the nerve growth factor gene transcription. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;124:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culmsee C, Semkova I, Krieglstein J. NGF mediates the neuroprotective effect of the beta2-adrenoceptor agonist clenbuterol in vitro and in vivo: evidence from an NGF-antisense study. Neurochem Int. 1999;35:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Toso R, De Bernardi MA, Brooker G, Costa E, Mocchetti I. Beta adrenergic and prostaglandin receptor activation increases nerve growth factor mRNA content in C6–2B rat astrocytoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;246:1190–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneke T, Chaar H, de Groot JR, Wilde AA, Lawo T, Mundig J, Bosche L, Mugge A, Grewe PH. Shift in the pattern of autonomic atrial innervation in subjects with persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue T, Smith P. Parasympathetic withdrawal in heart failure involves reduced vagal prejunctional inhibition of sympathetic nerves. Experimental Biology Abstracts 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Du XJ, Dart AM, Riemersma RA, Oliver MF. Failure of the cholinergic modulation of norepinephrine release during acute myocardial ischemia in the rat. Circ Res. 1990;66:950–956. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap ME, Bibevski S, Rosenberry TL, Ernsberger P. Mechanisms of altered vagal control in heart failure: influence of muscarinic receptors and acetylcholinesterase activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1632–1640. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg DL, Drabinsky M, Braunwald E. Defective cardiac parasympathetic control in patients with heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197110142851602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y, Tomioka N, Sato W, Satoyoshi E, Hayashi K, Furukawa S. Catecholamines increase nerve growth factor mRNA content in both mouse astroglial cells and fibroblast cells. FEBS Lett. 1989;247:463–467. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan W, Jama A, Donohue T, Wernli G, Onyszchuk G, Al-Hafez B, Bilgen M, Smith PG. Sympathetic hyperinnervation and inflammatory cell NGF synthesis following myocardial infarction in rats. Brain Res. 2006;1124:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan W, Smith PG. Nerve growth factor expression in parasympathetic neurons: regulation by sympathetic innervation. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4391–4397. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan W, Smith PG. Modulation of rat parasympathetic cardiac ganglion phenotype and NGF synthesis by adrenergic nerves. Auton Neurosci. 2009;145:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes VY, Isackson PJ, Fabrazzo M, Follesa P, Mocchetti I. Induction of nerve growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor mRNA following clenbuterol: contrasting anatomical and cellular localization. Exp Neurol. 1995;132:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze M, Hart D, Samarel A, Barakat J, Eckert L, Scrogin K. Persistent alterations in heart rate variability, baroreflex sensitivity, and anxiety-like behaviors during development of heart failure in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H29–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01373.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze M, Tiniakov R, Samarel A, Holmes E, Scrogin K. Chronic fluoxetine reduces autonomic control of cardiac rhythms in rats with congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H444–454. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MR, Wallick DW, Mongeon LR, Martin PJ, Levy MN. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide antagonists attenuate vagally induced tachycardia in the anesthetized dog. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1467–1472. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi H, Umezu M, Jang IS, Ito Y, Akaike N. Alpha 1-adrenoceptor-activated cation currents in neurones acutely isolated from rat cardiac parasympathetic ganglia. J Physiol. 2003;548:111–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa H, Ieda M, Kimura K, Arai T, Kawaguchi-Manabe H, Matsuhashi T, Endo J, Sano M, Kawakami T, Kimura T, Monkawa T, Hayashi M, Iwanami A, Okano H, Okada Y, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Ogawa S, Fukuda K. Heart failure causes cholinergic transdifferentiation of cardiac sympathetic nerves via gp130-signaling cytokines in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:408–421. doi: 10.1172/JCI39778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye DM, Vaddadi G, Gruskin SL, Du XJ, Esler MD. Reduced myocardial nerve growth factor expression in human and experimental heart failure. Circ Res. 2000;86:E80–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Kanazawa H, Ieda M, Kawaguchi-Manabe H, Miyake Y, Yagi T, Arai T, Sano M, Fukuda K. Norepinephrine-induced nerve growth factor depletion causes cardiac sympathetic denervation in severe heart failure. Auton Neurosci. 2010;156:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinugawa T, Dibner-Dunlap ME. Altered vagal and sympathetic control of heart rate in left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R310–316. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.2.R310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreusser MM, Buss SJ, Krebs J, Kinscherf R, Metz J, Katus HA, Haass M, Backs J. Differential expression of cardiac neurotrophic factors and sympathetic nerve ending abnormalities within the failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger C, Kalenka A, Haunstetter A, Schweizer M, Maier C, Ruhle U, Ehmke H, Kubler W, Haass M. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in conscious rats with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2240–2247. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet. 1998;351:478–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechat P, Hulot JS, Escolano S, Mallet A, Leizorovicz A, Werhlen-Grandjean M, Pochmalicki G, Dargie H. Heart rate and cardiac rhythm relationships with bisoprolol benefit in chronic heart failure in CIBIS II Trial. Circulation. 2001;103:1428–1433. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.10.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MN. Autonomic interactions in cardiac control. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;601:209–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb37302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zheng C, Sato T, Kawada T, Sugimachi M, Sunagawa K. Vagal nerve stimulation markedly improves long-term survival after chronic heart failure in rats. Circulation. 2004;109:120–124. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105721.71640.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YH, Yang XP, Nass O, Sabbah HN, Peterson E, Carretero OA. Chronic heart failure induced by coronary artery ligation in Lewis inbred rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H722–727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobos E, Gebhardt C, Kluge A, Spanel-Borowski K. Expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) isoforms in the rat uterus during pregnancy: accumulation of precursor proNGF. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1922–1929. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiacono RE, Story DF. Effect of alpha-adrenoceptor agonists and antagonists on cholinergic transmission in guinea-pig isolated atria. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1986;334:40–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00498738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi F, Mortara A. Heart rate variability and cardiac failure. Heart. 1998;80:213–214. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DD, Schmid PG, Roskoski R., Jr Neurochemical indices of autonomic innervation of heart in different experimental models of heart failure. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1983;161:179–198. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4472-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markos F, Snow HM. Vagal postganglionic origin of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) mediating the vagal tachycardia. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:419–422. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder P, Barbier S, Chagraoui A, Richard V, Henry JP, Lallemand F, Renet S, Lerebours G, Mahlberg-Gaudin F, Thuillez C. Long-term heart rate reduction induced by the selective I(f) current inhibitor ivabradine improves left ventricular function and intrinsic myocardial structure in congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:1674–1679. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118464.48959.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng J, Villuendas R, Cokic I, Schliamser JE, Gordon D, Koduri H, Benefield B, Simon J, Murthy SN, Lomasney JW, Wasserstrom JA, Goldberger JJ, Aistrup GL, Arora R. Autonomic remodeling in the left atrium and pulmonary veins in heart failure: creation of a dynamic substrate for atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:388–396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihei M, Lee JK, Honjo H, Yasui K, Uzzaman M, Kamiya K, Opthof T, Kodama I. Decreased vagal control over heart rate in rats with right-sided congestive heart failure: downregulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Circ J. 2005;69:493–499. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondicova K, Mravec B. Multilevel interactions between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems: a minireview. Endocr Regul. 2010;44:69–75. doi: 10.4149/endo_2010_02_69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter TR, Eckberg DL, Fritsch JM, Rea RF, Beightol LA, Schmedtje JF, Jr, Mohanty PK. Autonomic pathophysiology in heart failure patients. Sympathetic-cholinergic interrelations. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1362–1371. doi: 10.1172/JCI114580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Vulapalli RS, Stevens SY, Liang CS. Loss of cardiac sympathetic neurotransmitters in heart failure and NE infusion is associated with reduced NGF. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H363–371. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00319.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandra R, Hood SG, Denton DA, Woods RL, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM, May CN. Basis for the preferential activation of cardiac sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:924–928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811929106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R, Jr, Schmid PG, Mayer HE, Abboud FM. In vitro acetylcholine biosynthesis in normal and failing guinea pig hearts. Circ Res. 1975;36:547–552. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.4.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah HN. Electrical vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78(Suppl 1):S24–29. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78.s1.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah HN, Ilsar I, Zaretsky A, Rastogi S, Wang M, Gupta RC. Vagus nerve stimulation in experimental heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samina Riaz S, Tomlinson DR. Pharmacological modulation of nerve growth factor synthesis: a mechanistic comparison of vitamin D receptor and beta(2)-adrenoceptor agonists. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semkova I, Schilling M, Henrich-Noack P, Rami A, Krieglstein J. Clenbuterol protects mouse cerebral cortex and rat hippocampus from ischemic damage and attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons by induction of NGF. Brain Res. 1996;717:44–54. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM, Levy MN. Prejunctional cholinergic modulation of adrenergic neurotransmission in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:H275–281. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.3.H275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernli G, Hasan W, Bhattacherjee A, van Rooijen N, Smith PG. Macrophage depletion suppresses sympathetic hyperinnervation following myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:681–693. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel GT, Brown JH. Presynaptic modulation of acetylcholine release from cardiac parasympathetic neurons. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H33–39. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.1.H33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XL, Zang WJ, Lu J, Kang XQ, Li M, Yu XJ. Effects of carvedilol on M2 receptors and cholinesterase-positive nerves in adriamycin-induced rat failing heart. Auton Neurosci. 2006;130:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZJ, Adams DJ. Alpha-adrenergic modulation of ionic currents in cultured parasympathetic neurons from rat intracardiac ganglia. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1060–1070. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Levy MN. Sequence of excitation as a factor in sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions in the heart. Circ Res. 1992;71:898–905. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Popovic ZB, Bibevski S, Fakhry I, Sica DA, Van Wagoner DR, Mazgalev TN. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation improves autonomic control and attenuates systemic inflammation and heart failure progression in a canine high-rate pacing model. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:692–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.873968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]