Abstract

The purpose of this study was to present descriptive information on the characteristics of 2,873 Medicare home health clients, to quantify systematically their patterns of service utilization and allowed charges during a total episode of care, and to clarify the bivariate associations between client characteristics and utilization.

The model client was female, 75-84 years of age, living with a spouse, and frail based on a variety of indicators. The mean total episode was approximately 23 visits, with allowed charges of $1,238 (1986 dollars). Specific subgroups of clients, defined by their morbidities and frailties, used identifiable clusters of services. Implications for case-mix models and implications for capitation payments under health care reform are discussed.

Introduction

Several factors contribute to the heightened recent interest in understanding the role of home health care in the continuum of services for Medicare beneficiaries. First, Medicare home health agencies (HHAs) command growing importance in the Medicare budget, almost doubling expenditures from $1.6 billion in fiscal year (FY) 1983 to $3.2 billion in FY 1989 (approximately 6 percent of the total expenditures) and almost doubling again in the next 2 years to $5.7 billion in FY 1991 (Letsch et al., 1992). Second, the increasing numbers of the very old among the Medicare beneficiaries are expected to contribute to more demand beyond the 2.2 million HHA clients in 1991 (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1993). Third, the number of Medicare-certified providers also has been growing steadily over the past several years, increasing 43 percent from 1983 to 1989 to 6,100 HHAs (U. S. General Accounting Office, 1989) and leveling off at 6,000 in 1991. This growth in the number of providers is expected to continue as hospitals continue to enter this market and as recent legal and administrative changes increase the Medicare services available to Medicare beneficiaries. Last, the incentives of Medicare's hospital prospective payment system (PPS) have also contributed to increased use; shortened stays and more care needs at discharge have contributed to greater home care demand post-discharge (Noether, 1988).

All these factors have increased concerns about the growing expense of home care and, hence, interest in promoting its efficiency. PPS and capitation systems are viewed as complimentary ways to redirect incentives from the current cost-based system, with its traditional inflationary incentives, to more cost-conscious behavior among the providers.

An initial step towards promoting efficiency, either by PPS, a capitated managed care system, or any other policy redirection, is to document systematically the characteristics of current HHA clients, the actual services they receive, the charges for these services, and more importantly any significant associations between client characteristics and types, amount, and charges for services received. Once current practices are systematically documented, the implications of redirections can be considered. A prior analysis of the present data examined the concordance between planned and approved visits during the first 60 days of home care (Branch, Goldberg, and Cheh, 1991). The present analyses present descriptive information for total episodes of Medicare home health care.

Data

Sites

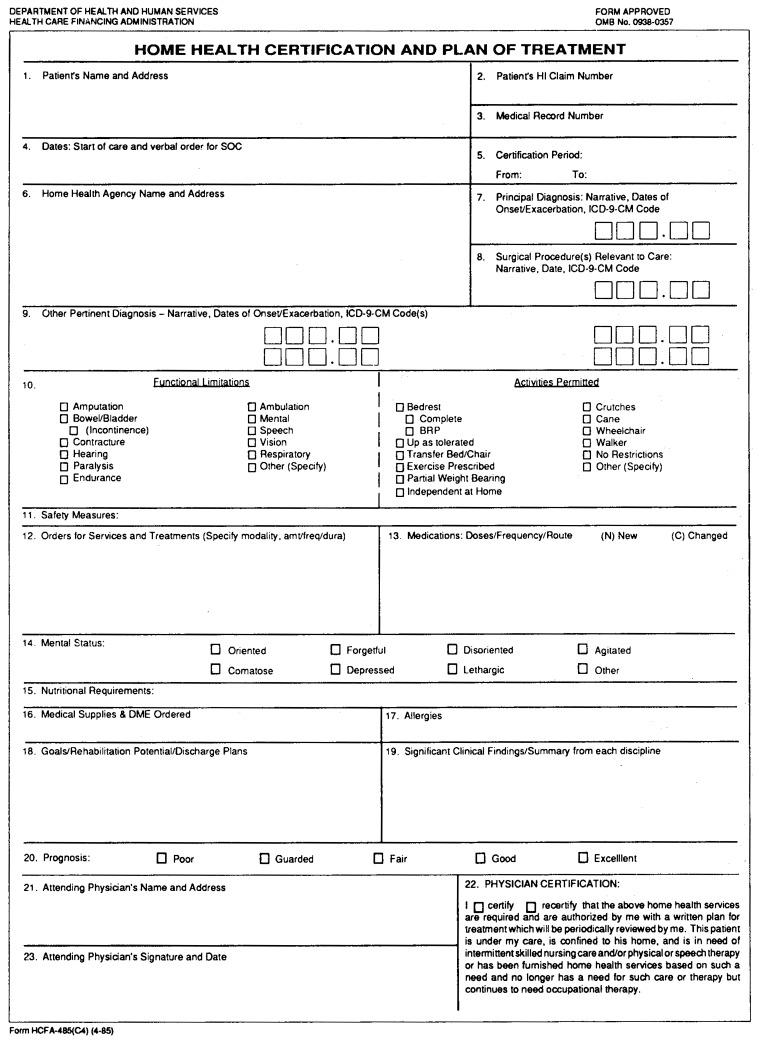

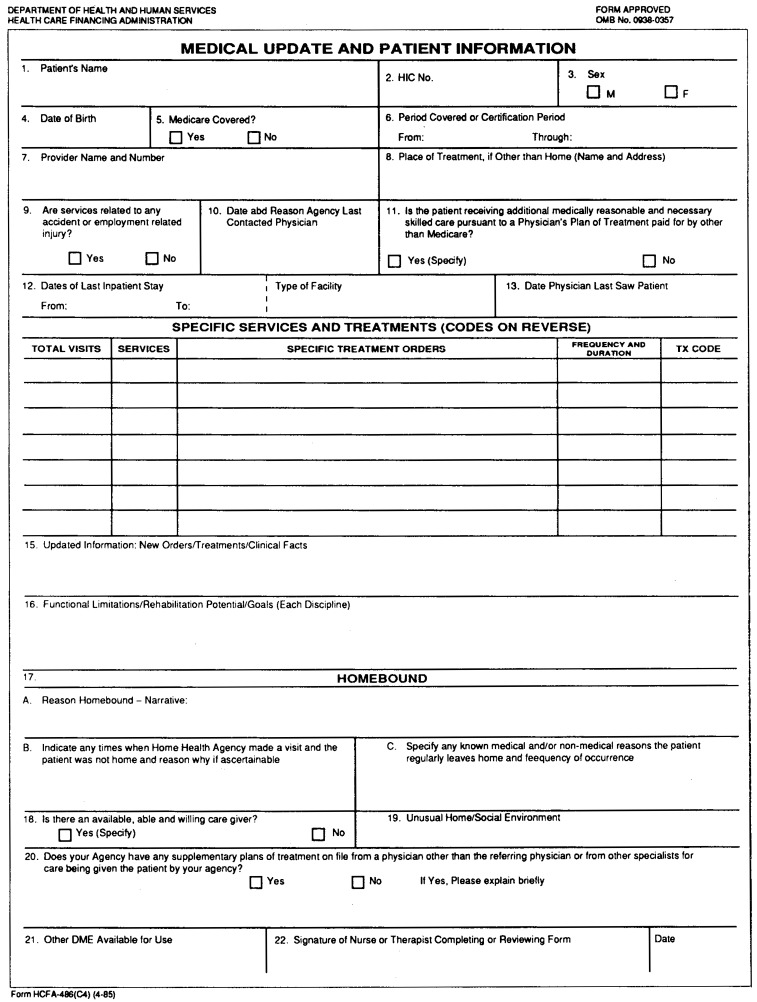

The data for this analysis were obtained in 1987 from a sample of the Medicare-certified HHAs that the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) had recruited in 1985 to participate in an HHA prospective payment demonstration that was not implemented at that time. These agencies had been recruited within 10 States (California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin) from the universe of known HHAs in those States that met three inclusion criteria (urban location, non-government operated, and established before January 1, 1983). A total of 235 agencies met the criteria and were approached; 127 expressed initial interest in participating in this data collection effort; and of these, 86 agencies actually submitted data. Each agency submitted copies of HCFA Forms-485 and 486 (Figures 1 and 2) for a sample of clients who began an episode of care in 1986 and submitted copies of the agency's Medicare cost reports for 1986.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Subjects

From each of the participating agencies, a systematic sample of clients was selected, designed to yield approximately 80 to 200 Medicare HHA clients per agency who were admitted for a new episode of care during calendar year 1986. Of those clients for whom data were received, only those who had verified Medicare claim numbers ending in 0, 4, 5, or 8 (and, therefore, whose complete HHA billing information would be available on the HCFA Bureau of Data Management and Strategy [BDMS] HHA 40-percent Bill Skeleton file) and for whom data on allowed visits were actually received were considered conditionally eligible for this analysis (unweighted n = 3,614 clients).

The sampling fraction for each HHA varied; consequently, the individual responses were weighted by the inverse of the sampling fraction. The sample sizes indicated in the tables are the number of respondents; the percents are based on the weighted data.

Episodes

For each client admitted to HHA care, HCFA Forms-485 and 486 are completed to establish medical necessity for home health care and to document treatment plans and other aspects of the case. HCFA Forms-485 and 486 also include a certification “from” and “to” date. However, because of inconsistencies in agency practice, the “from” date on HCFA Form-485 was found not necessarily to be the starting date of a new episode for every client. Therefore, for this analysis, the conceptual definition of a new episode was that the client had not been receiving HHA services for the preceding 60 days.

The operational definition of the start of a new episode relied on the HHA 40-percent Bill Skeleton file in the following way. Starting with the “to” date on HCFA Form-485, each patient's billing record was examined retrospectively to identify a 60-day interval with no home health services. The day after this 60-day billing gap was designated as the episode start date for this analysis. For nearly three-fourths of the conditionally eligible clients (72 percent; unweighted n = 2,615 clients), the episode start date thus defined was identical to the “from” date on HCFA Form-485; and for another 7 percent (unweighted n = 258), the episode start date was within 5 days of the “from” date on HCFA Form-485. These 2,873 clients comprise the analytic group for this analysis, and their data were appropriately weighted.

The end of an episode was defined as the last day of home health care following the start date that preceded another 60-day gap in the HHA 40-percent Bill Skeleton file. Treatment plans for every 60-day period following the initial “end” date on HCFA Form-485 are recorded on a series of HCFA Forms-486 for each client. The HHA 40-percent Bill Skeleton file included all claims processed through September 1987, which is 9 months after the start date of the last possible new episode during the study window of calendar year 1986. However, previous experience has shown that a 6-month lag in the processing of home health claims can exist, which could cause some distortions in exceedingly long episodes and some of the episodes that began in late 1986. We estimate that only a small percent may be truncated in our analysis.

Table 1 presents the weighted distribution of episode lengths of stay according to this definition. More than 40 percent of the Medicare HHA clients completed their home care within 30 days (41.2 percent), and another one-third completed their episodes within 30-60 days (30.9 percent). Only about 5 percent of the clients had episodes lasting 6 months or longer.

Table 1. Weighted Percent Distribution of Episode Lengths in Days Among Medicare Home Health Care Clients, by Length of Stay.

| Length of Stay | Percent Distribution |

|---|---|

| Less than 30 days | 41.2 |

| 30-59 days | 30.9 |

| 60-89 days | 10.6 |

| 90-179 days | 11.7 |

| 180 days or over | 5.5 |

NOTE: Unweighted n = 2,873.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Bureau of Data Management and Strategy: Data extracted from HCFA Forms-485 and 486 and Medicare utilization data from the Home Health Agency 40-percent Bill Skeleton files for a sample of clients beginning an episode of home health care in 1986.

Variables

Although there were a few exceptions, the information provided on HCFA Forms-485 and 486 is without missing data in nearly all fields. As Figure 1 indicates, the variable “living arrangement” requested information on “unusual home or social environment.” It was not possible to categorize household composition on 46 percent of the cases, either because their episode was short and they did not have a HCFA Form-486 or because nothing “unusual” was entered. The variable “admission source” had missing data in 1 percent of the records. For three variables (morbidity restrictions, medications, and factual limitations), the category “none” was inferred from the absence of a response; because 3.6 percent, 5.2 percent and 1.3 percent, respectively, of these variables was judged consistent with expected prevalence rates, any problem resulting from missing data is assumed to be negligible, with the exception of living arrangement.

HCFA Form-485 provided sex and age (categorized as under 65 years of age, 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years of age or over in this analysis information). For the 54 percent with information on usual living arrangement, the categories were “alone,” “with spouse,” or “other.” Admission source had four categories: “from a hospital (medical),” “from a hospital (surgical),” “from a nursing home,” or “unknown.” Mobility restrictions were categorized based on responses to the HCFA Form-485 item indicating activities permitted; the four categories developed for this analysis were “complete bed-rest,” “wheelchair-bound,” “required cane or crutch or walker,” or “has none of the previous three restrictions.” Information from HCFA Form-485 on number of medications was categorized in this analysis as “none,” to “1 to 3 current medications,” “4 to 6 current medications,” or “7 or more.” Nutritional status was obtained from the HCFA Form-485 notation of physician's orders for special diets, and each individual was categorized as needing a “low sodium diet,” “another special diet,” or “no special diet.” Functional limitations in each of the following 11 areas were available from HCFA Form-485: endurance, ambulation, respiration, vision, hearing, mental, bowel or bladder, speech, paralysis, contracture, or amputation. The principal International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration, 1980) diagnosis was reported on HCFA Form-485, and the 16 most common diagnoses are included in this analysis. The most common diagnosis was malignant neoplasms (11.5 percent of the clients), and the 16th most common diagnosis was chronic skin ulcers (2.5 percent of the clients).

The dependent variables were “allowed visits” and “allowed charges,” both in total and by type of service for the whole episode of care. This information was available from the HHA 40-percent Bill Skeleton file. Type of services included skilled nursing, home health aides, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, medical social work, and other. Rates of service use were calculated both for the total sample and for the subset who received the specific type of service.

Results and Discussions

Respondent characteristics are presented in Table 4 as cross-tabulations with allowed visits. Approximately two of every three HHA clients were female (62.6 percent), and 5.7 percent were under 65 years of age, whereas 21.9 percent were 85 years of age or over. Living arrangement was unknown for nearly one-half of the clients (45.3 percent); but of the remainder, approximately one of every three lived alone (34 percent), nearly one of every two lived with a spouse (42 percent), and 24 percent lived in other arrangements. Concerning the source of admission to the Medicare HHA, about one of every five came directly from the community (19.6 percent); three of every four came from a hospital, with approximately one-third having been surgical patients (32.0 percent) and slightly more having been medical patients (44.0 percent); whereas 3.4 percent had been discharged from a nursing home. Concerning their mobility restrictions, very few had none (3.6 percent), and the vast majority (79.1 percent) relied on a cane or crutch or walker. Approximately 1 of every 10 (11.7 percent) relied on a wheelchair, and 1 in every 20 (5.6 percent) required total bed-rest. The vast majority of clients were receiving some prescription medications (only 5.2 percent were not). Two of every three were receiving four medications or more. Concerning nutritional status, nearly one-half (46.4 percent) had no indication of a special diet, approximately one in every four (28.1 percent) required a low sodium diet, and another one in every four (25.5 percent) had another type of special diet required.

Table 4. Weighted Distribution of Type of Allowed Visits During an Episode, by Medicare Home Health Care Client Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Totals | Percent | Skilled Nursing | Home Health Aide | Physical Therapy | Occupational Therapy | Speech Therapy | Medical Social Work | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean Visits | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Total Clients | 22.71 | 100.0 | 12.62 | 5.79 | 3.25 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.02 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 21.53 | 37.4 | 11.81 | 5.48 | 2.88 | 0.67 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.01 |

| Female | 23.42 | 62.6 | 13.10 | 5.98 | 3.46 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.03 |

| Age | |||||||||

| Under 65 years | 16.49 | 5.7 | 10.33 | 2.44 | 2.63 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| 65-74 years | 23.85 | 33.6 | 13.35 | 5.60 | 3.50 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.03 |

| 75-84 years | 21.96 | 38.8 | 12.02 | 5.80 | 3.12 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| 85 years or over | 23.93 | 21.9 | 13.14 | 6.95 | 3.25 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Living Arrangement | |||||||||

| Alone | 20.50 | 18.6 | 12.68 | 4.82 | 2.38 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.04 |

| Spouse Only | 24.15 | 23.1 | 12.23 | 6.81 | 3.45 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.01 |

| Other | 22.89 | 13.0 | 12.40 | 5.75 | 3.62 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.01 |

| Unknown | 22.83 | 45.3 | 12.85 | 5.68 | 3.39 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.02 |

| Admission Source | |||||||||

| Community | 23.48 | 19.6 | 13.61 | 5.84 | 2.85 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| Hospital, Surgical | 21.36 | 32.0 | 11.82 | 4.67 | 4.06 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.02 |

| Hospital, Medical | 22.66 | 44.0 | 12.74 | 6.37 | 2.41 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Nursing Home | 34.29 | 3.4 | 13.96 | 9.60 | 8.74 | 1.18 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.10 |

| Unknown | 14.61 | 1.0 | 8.77 | 2.26 | 3.35 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| Mobility Restrictions | |||||||||

| None | 31.30 | 3.6 | 23.83 | 3.54 | 3.41 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| Cane, Crutch, Walker | 24.48 | 79.1 | 11.54 | 6.82 | 5.02 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.01 |

| Wheelchair | 37.72 | 11.7 | 16.34 | 12.63 | 5.99 | 1.48 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| Bedfast | 21.82 | 5.6 | 12.33 | 8.40 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| Medications | |||||||||

| None | 13.15 | 5.2 | 5.86 | 1.84 | 4.75 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| 1-3 | 20.68 | 30.1 | 11.57 | 4.42 | 3.72 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| 4-6 | 23.69 | 40.1 | 13.39 | 6.41 | 2.85 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| 7 or more | 25.61 | 24.6 | 14.05 | 7.29 | 2.99 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.01 |

| Nutritional Status | |||||||||

| No Special Diet | 20.54 | 46.4 | 10.86 | 5.26 | 3.59 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| Low Sodium | 24.31 | 28.1 | 13.79 | 6.85 | 2.75 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Special Diet | 24.92 | 25.5 | 14.52 | 5.59 | 3.16 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Functional Limitations1 | |||||||||

| Endurance | 22.08 | 85.0 | 12.22 | 5.70 | 3.09 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

| Ambulation | 23.46 | 80.6 | 12.41 | 6.24 | 3.76 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.01 |

| Vision | 25.26 | 27.4 | 14.63 | 6.90 | 2.72 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| Respiration | 21.31 | 26.7 | 13.23 | 5.58 | 1.66 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| Hearing | 20.74 | 19.8 | 12.38 | 4.93 | 2.54 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| Mental | 22.43 | 18.3 | 12.49 | 5.92 | 2.51 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.06 |

| Bowel or Bladder | 29.68 | 16.5 | 14.04 | 10.18 | 3.61 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| Speech | 29.41 | 7.5 | 13.08 | 6.67 | 4.75 | 1.78 | 2.74 | 0.38 | 0.01 |

| Paralysis | 39.28 | 5.9 | 13.92 | 12.22 | 8.01 | 2.72 | 1.61 | 0.78 | 0.01 |

| Contracture | 26.18 | 3.3 | 11.60 | 8.45 | 4.77 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.00 |

| Amputation | 27.67 | 2.8 | 14.54 | 5.95 | 6.54 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| Number of Limitations | |||||||||

| None | 34.11 | 1.3 | 24.68 | 7.65 | 1.36 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 15.03 | 9.9 | 9.20 | 2.36 | 3.09 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 22.80 | 31.3 | 12.90 | 5.38 | 3.55 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.05 |

| 3 | 21.36 | 28.7 | 12.10 | 5.39 | 2.89 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 25.22 | 16.3 | 13.30 | 7.70 | 3.37 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 28.01 | 7.7 | 13.67 | 8.35 | 3.92 | 1.12 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| 6 or more | 25.84 | 4.9 | 13.56 | 6.79 | 2.70 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| Principal Diagnosis2 | |||||||||

| Malignant Neoplasms | 24.26 | 11.5 | 15.86 | 6.93 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.00 |

| Heart Disease-Other | 24.09 | 8.3 | 13.93 | 8.00 | 1.56 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 32.97 | 7.8 | 11.74 | 7.86 | 7.61 | 2.96 | 2.41 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| Digestive System Disease | 16.17 | 6.2 | 12.64 | 2.58 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| Arthropathies | 16.09 | 5.3 | 3.64 | 3.32 | 8.57 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 17.32 | 5.2 | 10.99 | 5.18 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 25.74 | 5.0 | 18.56 | 4.24 | 1.78 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

| Chronic Obstructive Coronary Disease | 17.74 | 4.2 | 10.61 | 5.24 | 1.19 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| Circulatory System Disease | 24.86 | 4.1 | 18.71 | 3.77 | 2.21 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Bone Fractures | 20.54 | 3.8 | 5.17 | 4.82 | 9.43 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.09 |

| Hip Fractures | 30.24 | 3.7 | 8.56 | 7.63 | 12.83 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.05 |

| CNS Disease | 21.96 | 3.3 | 9.16 | 6.20 | 4.04 | 1.52 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 19.60 | 2.7 | 11.18 | 7.26 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Genitourinary System Disease | 20.78 | 2.7 | 12.22 | 6.69 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Injuries or Poisoning | 19.70 | 2.6 | 13.21 | 4.05 | 2.10 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Chronic Skin Ulcer | 18.57 | 2.4 | 13.18 | 3.36 | 1.91 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

Each client could have each limitation either present or not.

Eighty-eight records had a missing or invalid primary diagnosis; percents are based on those with a primary diagnosis.

NOTE: Unweighted n = 2,873. CNS is central nervous system.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Bureau of Data Management and Strategy: Data extracted from HCFA Forms-485 and 486 and Medicare utilization data from the Home Health Agency 40-percent Bill Skeleton files for a sample of clients beginning an episode of home health care in 1986.

Eleven categories of functional limitations were identified for each of the HHA clients. The vast majority of the clients were reported to have endurance limitations (85.0 percent) and ambulation limitations (80.6 percent). The next most common limitations were reported for approximately one in every four clients (vision limitations for 27.4 percent and respiration limitations for 26.7 percent). Slightly less than one of every five clients were reported to have hearing limitations (19.8 percent), mental limitations (18.3 percent), and bowel or bladder limitations (16.5 percent). The remaining four limitations were reported for less than 10 percent of the clients: 7.5 percent had speech limitation, 5.9 percent had paralysis limitations, 3.3 percent had contracture limitations, and 2.8 percent had amputation limitations. Simply summing across the number of limitations that any individual HHA client was reported to have, it is interesting to observe that the clients in general had multiple limitations. Only 1 in every 10 (9.9 percent) had only one limitation reported, and only 1.3 percent had no limitations (these probably reflect incomplete HCFA Form-485 completion). Nearly one of every three (31.3 percent) had two limitations, and approximately one-third (28.7 percent) had three limitations. The last 30 percent had four limitations or more, including 4.9 percent who had six limitations or more.

The principal ICD-9-CM diagnosis for each client was also recorded. The most prevalent diagnosis was malignant neoplasms (11.5 percent of clients). Five to 10 percent had heart disease-other (8.3 percent), cerebrovascular diseases (7.8 percent), digestive system disease (6.2 percent), arthropathies (5.3 percent), ischemic heart disease (5.2 percent), or diabetes mellitus (5.0 percent). The 16th most common disease was chronic skin ulcer (2.4 percent).

Table 2 presents the distribution of allowed visits and charges for a total episode during 1986 for these Medicare HHA clients. The vast majority of HHA clients received skilled nursing visits (90.1 percent), whereas approximately one of every three received care form a home health aide (35.2 percent) or a physical therapist (32.8 percent). The remaining types of skilled care were provided to much smaller percents of clients, ranging from 14 percent receiving medical social work services to 2 percent receiving speech therapy.

Table 2. Weighted Distribution of Allowed Visits and Charges, by Type of Visit During An Episode Among Medicare Home Health Care Clients.

| Type of Visit | Percent Receiving | Total Mean Visits for All | Total Mean Visits for Users | Total Mean Charges | Total Mean Charges for Users |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 100.0 | 22.71 | — | $1,237.82 | — |

| Skilled Nursing | 90.1 | 12.62 | 14.00 | 738.58 | $819.83 |

| Home Health Aide | 35.2 | 5.79 | 16.48 | 245.09 | 697.21 |

| Physical Therapy | 32.8 | 3.25 | 9.89 | 187.85 | 572.22 |

| Occupational Therapy | 6.0 | 0.52 | 8.59 | 29.99 | 498.52 |

| Speech Therapy | 2.1 | 0.24 | 11.45 | 13.44 | 649.67 |

| Medical Social Work | 13.9 | 0.28 | 2.04 | 21.83 | 156.70 |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.02 | 4.84 | 1.04 | 238.76 |

NOTE: Unweighted n = 2,873.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Bureau of Data Management and Strategy: Data extracted from HCFA Forms-485 and 486 and Medicare utilization data from the Home Health Agency 40-percent Bill Skeleton files for a sample of clients beginning an episode of home health care in 1986.

The second column of Table 2 presents the mean number of visits during the whole episode by type of visit for the total sample of clients. The mean number of visits for all clients was 22.71, with more than one-half provided by skilled nurses (12.62) and one-fourth provided by home health aides (5.79). Three of the services (occupational therapy, speech therapy, and medical social work) provided less than one visit on average to these clients.

The next column presents the mean number of visits for the subgroup that used the specific type of visit. Among users, home health aides provided the highest number of visits per regimen at 16.48 on average, followed by skilled nurses at 14.00 and speech therapists at 11.45 per regimen. Both physical therapists and occupational therapists provided about 8 to 10 visits, on average, to the subset who received them. Medical social work was used both by a small percent (13.9 percent) and in small amounts (2.04 visits per regimen).

The next column presents the mean allowed charges for all these clients, with an average total episode charge of $1,237.82 per client in 1986. The mean charges by type of service for all clients in large measure reflect the mean number of visits because the charges per visit were approximately equal (averaging $57 to $59 per visit) in four of the major types (skilled nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy). The two outliers were home health aide visits, which averaged less at $42 per visit, and medical social worker visits, which averaged more at $77 per visit.

Notwithstanding that medical social workers had the highest charge per visit, on average, the last column of Table 2 indicates that the mean charges for a regimen of medical social work therapy was by far the least expensive service at $156.70 compared with the next lowest average charge for the users of a specified therapy ($498.52 for those receiving occupational therapy). Skilled nursing services had the highest mean charges at $819.83 for the users.

Table 3 presents the distribution among these Medicare HHA clients of allowed visits and allowed charges during a whole episode by the type of visit. Inspecting the total visit column, the range varies considerably according to the type of visit the client received. The mean number of total visits among all clients was nearly 23 visits. However, those receiving speech therapy received almost 54 visits on average, with 11 to 12 visits on average from the speech therapist contributing to their increased amount. Regimens of nearly 14 and 11 visits for skilled nursing and physical therapy also contributed to their 54-visit average. An occupational therapy regimen of approximately 8 to 9 visits was also the norm of those receiving either speech therapy or occupational therapy, contributing to the total mean visits of 54 for the former and 47 visits on the average for the latter group. For the 90 percent receiving skilled nursing services, their total mean visits was nearly 24, with more than one-half their visits (14.00) provided by skilled nurses and over one-fourth (6.17) provided by home health aides.

Table 3. Weighted Distribution of Allowed Visits and Charges, by Type of Visit During an Episode Among Medicare Home Health Care Clients.

| Type of Visit | Total Visits | Unweighted n | Skilled Nursing | Home Health Aide | Physical Therapy | Occupational Therapy | Speech Therapy | Medical Social Work | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Visits | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Total Clients | 22.71 | 2,873 | 12.62 | 5.79 | 3.25 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.02 |

| Skilled Nursing | 23.69 | 2,607 | 14.00 | 6.17 | 2.46 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| Home Health Aide | 39.46 | 1,054 | 16.54 | 16.48 | 4.68 | 0.85 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.03 |

| Physical Therapy | 32.97 | 901 | 11.41 | 9.33 | 9.89 | 1.40 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| Occupational Therapy | 47.41 | 165 | 12.61 | 11.53 | 11.41 | 8.59 | 2.27 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Speech Therapy | 53.94 | 57 | 13.95 | 9.44 | 10.75 | 7.69 | 11.45 | 0.65 | 0.00 |

| Medical Social Work | 39.94 | 346 | 18.28 | 13.40 | 4.50 | 1.22 | 0.50 | 2.04 | 0.00 |

| Other | 50.63 | 10 | 14.12 | 17.12 | 14.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.84 |

| Mean Charges | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Total Clients | $1,237.82 | 2,873 | $738.58 | $245.09 | $187.85 | $29.99 | $13.44 | $21.83 | $1.04 |

| Skilled Nursing | 1,286.56 | 2,607 | 819.83 | 260.87 | 140.21 | 26.53 | 14.29 | 23.77 | 1.07 |

| Home Health Aide | 2,037.28 | 1,054 | 962.88 | 697.21 | 266.06 | 48.24 | 19.14 | 42.74 | 1.02 |

| Physical Therapy | 1,780.19 | 901 | 675.26 | 389.72 | 572.22 | 80.33 | 29.62 | 32.48 | 0.61 |

| Occupational Therapy | 2,665.42 | 165 | 773.99 | 538.86 | 646.41 | 498.52 | 23.10 | 84.58 | 0.00 |

| Speech Therapy | 2,883.54 | 57 | 802.04 | 365.08 | 604.31 | 419.83 | 649.67 | 42.61 | 0.00 |

| Medical Social Work | 2,259.49 | 346 | 124.68 | 610.38 | 266.08 | 72.97 | 28.69 | 56.70 | 0.00 |

| Other | 2,031.03 | 10 | 662.05 | 487.10 | 643.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 238.76 |

NOTE: Unweighted n = 2,873.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Bureau of Data Management and Strategy: Data extracted from HCFA Forms-485 and 486 and Medicare utilization data from the Home Health Agency 40-percent Bill Skeleton files for a sample of clients beginning an episode of home health care in 1986.

The same patterns emerge when inspecting Table 3 from the perspective of allowed charges, suggesting that variation in charges were minimal, as implied by the homogeneity of charges per visit for skilled nursing and physical, occupational, and speech therapy as mentioned previously. Those receiving skilled nursing services had mean allowed charges per episode of $1,286.56, whereas those receiving occupational therapy and medical social work services had approximately twice the mean charges ($2,665.42 and $2,259.49, respectively), and those receiving speech therapy had even higher mean allowed charges per episode at $2,883.54.

Table 4 presents the distribution of allowed visits during an episode according to the characteristics of the client. The patterns of allowed visits and charges as a function of the characteristics of the HHA client are very similar because of the homogeneity of charges among four of the professional therapies. Therefore, the charge data are omitted from this table. Furthermore, the large sample size lends itself to observing frequent statistical significance between client characteristic and number of specific services, as indicated by a chi-square analysis. Consequently, statistical significance is not indicated in this descriptive report, and the authors' judgments concerning practical significance are.

Inspecting Table 4 for differences in total visits or types of visits associated with characteristics of the client suggests some interesting patterns. The sex of the client was associated with both the number of allowed visits and the charges for an episode, with females receiving slightly more skilled nursing visits in particular and more visits in general. An exception was observed with speech therapy, for which male clients received approximately two to three times more visits than female clients. However, the prevalence of speech therapy is low even for males (0.39 versus 0.14 mean visits for males and females, respectively).

The age of the client also had a moderate association with the number of allowed visits and charges. Those under 65 years of age received fewer visits in general and fewer skilled nursing and home health aide visits in particular. There were few differences in type or amount of services among the age subgroups of those 65 years of age or over.

Living arrangement had a modest association with services received. Those living alone received fewer total services (20.50) than either those living with spouse or in other specified households (24.15 and 22.89, respectively). Those living alone received fewer home health aide, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy visits than the other household compositions, whereas those living with spouse received slightly more speech therapy services.

The admission source was associated with allowed visits and charges selectively. There were few differences in total services or type of individual services among those admitted from the community, from hospitals as medical patients, or from hospitals as surgical patients. Those whose admission source was unknown (1.0 percent of the clients) had substantially lower total services (14.61 total mean visits versus 22.71 for the total sample). Those admitted from nursing homes (again, a small subgroup at only 3.4 percent) had 50 percent more total services, on average, than the other clients (34.29 versus 22.71 total mean visits), including substantial increases in home health aide and physical therapy visits compared with the other clients.

The relationship between the client's mobility restrictions on volume and cost of allowed services was extremely variable. Those with wheelchair restrictions received substantially more services (37.72 mean total allowed visits compared with 22.71 for the total group; total allowed charges of $2,070 compared with $1,238 for the total group). As would be expected, those confined to bedrest had substantially less physical therapy visits and charges than the other clients. Occupational therapy visits were also substantially associated with mobility restrictions; those with no mobility restrictions or those confined to bed received very few occupational therapy visits, whereas those requiring the ambulatory aids of canes, crutches, or walkers or those in wheelchairs received substantially more. Those with no mobility restriction received substantially more skilled nursing services as well, contributing to a higher than average total mean visits (31.30 versus 22.71).

The association between medications and the number of visits and charges was uniform and positive. Those receiving no medications received 13.15 visits, on average, and had $789 in total approved charges. Those receiving 1 to 3 medications had an average of 20.68 visits and $1,133 total charges. Those taking 4 to 6 medications had 23.69 total mean allowed visits and $1,302 in total charges. Those receiving 7 medications or more had 25.61 total mean visits and $1,356 in total charges.

The nutritional status of the client also was associated with the allowed visits and charges in a uniform fashion. Total visits ranged from nearly 21, to 24, to nearly 25 for those with no special diet, low sodium diets, and other special diets, respectively. Total costs reflected the same trend, at $1,137, $1,307, and $1,346 for the three groups, respectively.

The functional limitations of the clients also were associated with the allowed visits and charges for these HHA clients. Home health aide services were elevated for those with bowel or bladder limitations or paralysis limitations. Physical therapy services were elevated for those with paralysis limitations or amputation limitations and reduced for those with respiration limitations. Occupational therapy visits and charges were elevated for those with paralysis limitations or speech limitations, whereas speech therapy was elevated principally for those with speech limitations and secondarily for those with paralysis limitations.

Overall, there seem to be three clusters of total allowed costs among the types of reported functional limitations. Six of the functional limitations were associated with total charges between $1,158 and $1,317 for the total episode (endurance, ambulation, vision, respiration, hearing, and mental limitations). It is also interesting to observe that these are the six most prevalent limitations reported as well. Four of the remaining limitations have total allowed episode charges that cluster between $1,404 and $1,603 (bowel or bladder limitations, speech limitations, amputation limitations, and contracture limitations). The last group, those with paralysis limitations, had the most costly average episode at $2,154, with elevated costs for home health aides, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

The number of these limitations reported per client had a slight linear association with increases in total services, with the exception that the small percent (1.3 percent) who had no limitations recorded had total services at approximately 1½ times the mean level for the whole group (34.11 visits versus 22.71 respectively). This finding supports the contention that those cases with missing information on functional limitations were more likely to be incomplete records than clients without limitations. Excluding those without recorded limitations, the greatest increment in approved visits and charges was between those with one limitation versus those with two limitations, with total allowed visits ranging from 15.03 to 22.80 and total allowed charges ranging from $816 to $1,236 as a function of the second limitation.

The association of principal diagnosis with total allowed services and allowed costs is interesting. Those with a diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease had the highest total charge per episode at $1,791. Those with hip fractures had the next most costly episode at $1,605. Those with either diabetes mellitus, circulatory system disease, or malignant neoplasms as the primary diagnosis formed a cluster with the fourth most costly episode of care ranging from $1,353 to $1,404. Those with a diagnosis of heart disease-other followed at $1,267 per episode, followed by those with central nervous system disease at $1,176 per episode. A cluster of five diagnoses followed, with total episode charges between $1,023 and $1,096 (bone fractures, hypertension, genitourinary system disease, injuries or poisoning, or chronic skin ulcers). The least expensive clustering had episode charges from $892 to $955 and includes those with diagnoses of ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, digestive system disease, or arthropathies.

For those with a principal diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease, the amounts of physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy were considerably elevated comparable with those with other diagnoses. Those with hip fractures, arthropathies, or bone fractures also had elevated physical therapy charges compared with other diagnoses.

Conclusions

The purpose of this analysis was to quantify systematically the characteristics of Medicare home health care clients, the parameters of a total episode of care, and the bivariate associations that might exist between client characteristics and components of care. The data available for this purpose have some weaknesses that limit some of the generalizability and utility of the findings.

First, the data came from HHAs solicited to participate in a demonstration project. The available data were designed to facilitate service delivery and payment, not for the exploratory research effort to which they were put. Furthermore, only a third of the eligible universe (37 percent, 87 out of 235 HHAs) provided data for this analysis. Hence, the generalizability may be limited because the data came only from HHAs willing to participate in a demonstration project.

Second, HCFA Forms-485 and 486 have some technical deficiencies as research instruments. For example, the approach of “checking all that apply” for functional limitations requires that the analysts draw an inference from a non-response. Hence, both an intended non-response and an erroneous omission cannot be distinguished. The impact of this technical deficiency is presumably minimal, however, because of the low level of erroneous omissions (i.e., missing data) in other items. The other example of a technical deficiency was in the wording of “unusual home or social environment” previously mentioned, which precluded the straightforward elicitation of “living arrangement” and produced missing data in 46 percent of the records. Consequently, the associations reported with living arrangement must be interpreted with considerable caution.

Notwithstanding those technical difficulties, HCFA Forms-485 and 486 are particularly helpful to this kind of policy research because these forms have continuing use in the Medicare home health care program. This continuing use of HCFA Forms-485 and 486 facilitate subsequent policy analyses at different times, at different sites, or with different contexts, but with the same data elements.

In summary, the descriptive profile of the model client was: female, 75-84 years of age, living with a spouse, admitted from a hospital, used ambulation aids, took 5 prescription medications, had no special diet, had 2 functional limitations (commonly endurance and ambulation limitations), and had cancer and/or heart disease. The total episode was approximately 23 visits, including 13 skilled nursing visits, 6 from home health aides, and 3 from physical therapists. The mean allowed charges for the total episode were $1,238 (1986 dollars).

The age and sex of the client had a slight association with allowed visits and charges, with those under 65 years of age and those who were male receiving fewer allowed services per episode than those 65 years of age or over or females. Those living alone had lower levels of allowed services. Those living with a spouse received more speech therapy, possibly suggesting an increased awareness of communication needs for these clients. Those admitted from a nursing home had greatly increased level of services, particularly home health aide and physical therapy services. Those with wheelchair restrictions also had elevated levels of total service use. Medication use exhibited a systematic linear association with total services and allowed charges for these Medicare clients. Nutritional status inferred from dietary requirements also was associated with HHA total service use, with those on no special diet likely to receive fewer services per episode. Both the specific type and the total number of limitations of the clients were associated with the total services provided per episode. With the exception of the few cases with no limitations listed, the association between total number of limitations and total services per episode was linear. Although those with paralysis limitations had by far the most costly care per episode, those with bowel or bladder limitations, speech limitations, amputation limitations, or contracture limitations had less but nevertheless substantially elevated total charge per episode compared with those with endurance, ambulation, vision, respiration, hearing, or mental limitations. Lastly, some of the principal diagnosis correlated with total service use, as follows. Those with cerebrovascular disease as the primary diagnosis had the highest total charge per episode, followed by those with hip fractures and those with either diabetes mellitus, circulatory system disease, or malignant neoplasm. Those with heart disease-other had the next most costly episodes, followed by those with diseases of the central nervous system. The second least costly episodes were found among those with primary diagnoses of either bone fracture, hypertension, genitourinary system disease, injuries or poisoning, or chronic skin disease. The lowest total charges per episode were found among those with diagnoses of ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, digestive system disease, or arthropathies.

The implications of these descriptive findings suggest additional analyses. The variability of charges and the definable service arrays among identifiable subgroup of HHA clients generate cautious optimism that a multivariate case-mix model may be developed that can render subgroups of these clients homogenous with respect to charges (Branch and Goldberg, 1993). The next step following case modeling or identifying homogenous subgroups with respect to charges or some other utilization-based measure is to consider prospective payment models or capitation models based on characteristics of the client as he or she enters the Medicare home health care program.

Based on the findings from these analyses in general and an inspection of the total authorized visits per episode reported in Table 4 in particular, a prospective payment model to Medicare HHAs might incorporate the following steps:

First, determine the mean total episode approved charges for an index year.

-

Second, offer a prospective payment to certified Medicare HHAs based on an inflation-adjusted mean charge, modified by the following client characteristics present at intake:

a 33-percent increment for those admitted from a nursing home.

a 33-percent decrement for those under age 65.

a 50-percent increment for those confined to a wheelchair.

a 33-percent increment for those with a principal diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease.

a 25-percent increase for those with a principal diagnosis of hip fracture.

a 25-percent decrease for those with a principal diagnosis of digestive system disease.

a 25-percent decrease for those with a principal diagnosis of arthropathies.

Third, allow the HHA to exclude post facto from the modified prospective payment a predetermined percentage of outliers (perhaps up to 3 percent) for adjudicated fee-for-service payments.

A capitation model could similarly incorporate modifiers to the basic compensation rate based on these demonstrated variations in the total episode of care, but additional analysis would be necessary to apply the modifier to the total eligible population and not just to the subset of HHA users as suggested in the prospective payment model.

Acknowledgments

The helpful programming assistance of Frederick A. DeFriesse of Abt Associates is gratefully acknowledged.

This study was supported in part by Contract Number 500-84-0021 from the Health Care Financing Administration. At the time this work was done the authors were with Abt Associates. Valerie Cheh is now with Mathematica Policy Research and Judith Williams is a consultant on health care policy, Miami, Florida The views expressed herein are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the Health Care Financing Administration is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Laurence G. Branch, Ph.D., Director of Long-Term Care Research, Abt Associates, 55 Wheeler Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138.

References

- Branch LG, Goldberg HB, Cheh VA. Concordance Between Planned and Approved Visits During Initial Home Care. Health Care Financing Review. 1991 Fall;13(1):83–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch LG, Goldberg HB. A Preliminary Case-mix Classification System for Medicare Home Health Clients. Medical Care. 1993;31(4):309–321. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letsch SW, Lazenby HC, Levit KR, Cowan CA. National Health Expenditures, 1991. Health Care Financing Review. 1992 Winter;14(2):1–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noether M. Changes in Patient Severity and Hospital Utilization Measured with MEDISGRPS. Abt Associates; Cambridge, MA.: 1988. Contract Number 500-85-0015. Prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Payment Assessment Commission. Medicare and the American Health Care System: Report to Congress. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jun, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sep, 1980. DHHS Pub. No. 80-1260. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare: Assuring the Quality of Home Health Services. Washington, DC.: Oct, 1989. Report to the U.S. Senate Pub. No. GAO/HRD-90-7. [Google Scholar]