Abstract

Background

Golgins are coiled-coil proteins associated with the Golgi apparatus, that are believed to be involved in the tethering of vesicles and the stacking of cisternae, as well as other functions such as cytoskeletal association. Many are peripheral membrane proteins recruited by GTPases. Several have been described in animal cells, and some in yeast, but the relationships between golgins from different species can be hard to define because although they share structural features, their sequences are not well conserved.

Results

We show here that the yeast protein Sgm1, previously shown to be recruited to the Golgi by the GTPase Ypt6, binds to Ypt6:GTP via a conserved 100-residue coiled-coil motif that can be identified in a wide range of eukaryotes. The mammalian equivalent of Sgm1 is TMF/ARA160, a protein previously identified in various screens as a putative transcription or chromatin remodelling factor. We show that it is a Golgi protein, and that it binds to the three known isoforms of the Ypt6 homologue Rab6. Depletion of the protein by RNA interference in rat NRK cells results in a modest dispersal of Golgi membranes around the cell, suggesting a role for TMF in the movement or adherence of Golgi stacks.

Conclusion

We have identified TMF as an evolutionarily conserved golgin that binds Rab6 and contributes to Golgi organisation in animal cells.

Background

Golgins are coiled-coil proteins that are associated with the Golgi apparatus and contribute to its organisation and function (for full review and references see [1]). Some, such as CASP and golgin-84, have a C-terminal transmembrane anchor, whereas others are peripheral proteins. There is evidence that some of them are tethers that help vesicles to dock with Golgi membranes, a good example being the yeast Uso1 protein and its mammalian homologue p115, which are implicated in ER-Golgi traffic [2,3]. Yeast Imh1 also plays a role in vesicle traffic to the Golgi [4]. Others have been suggested to link Golgi cisternae, stabilising their stacked morphology, or to act as scaffolds that hold Golgi-associated proteins with regulatory functions [1]. The golgins Bicaudal-D1 and -D2 are thought to link vesicles to the cytoskeleton [5]. Other functions have also been suggested – for example, some golgins might serve to protect membranes from inappropriate fusion events.

Several peripheral golgins have been shown to be anchored to Golgi membranes by association with Rab GTP-binding proteins, the binding site on the golgin often being part of the coiled-coil region. Thus for example Uso1/p115 binds to Ypt1/Rab1 [2,3], golgin-45 binds Rab2 [6], and Bicaudal-D binds Rab6 [5]. Other golgins such as Imh1, golgin-97 and golgin-240 share a small GRIP domain at their extreme C terminus, which binds to the GTPase Arl1 and serves to anchor them on Golgi membranes [1,7].

Coiled-coils often have a structural or spacer function, and as such are not necessarily well-conserved in evolution. Furthermore, their common amphipathic nature means that homology searches can be confusing, all long stretches of coiled-coil showing a superficial similarity. Thus, while some yeast and mammalian golgins share clear structural and functional homology, others are less obviously related.

Our previous studies on the yeast Rab6-like GTPase Ypt6 led to the identification of a protein, Sgm1, that can bind the GTP form of Ypt6 and has the characteristic extensive coiled-coil motifs of a golgin [8]. Moreover, Sgm1 is recruited to Golgi membranes in vivo by Ypt6 [8]. To identify a mammalian homologue, we have localised the Ypt6 binding site and looked for proteins with homology to this region of the protein. This approach identified TMF1/ARA160, which we show to be both localised to the Golgi and capable of binding to all three known isoforms of Rab6. Reduction of the levels of TMF protein by RNAi treatment of NRK cells resulted in an apparent loosening of the overall Golgi structure, with Golgi stacks being spread over a larger area than normal, consistent with a role for the protein in movement, anchoring or tethering of Golgi membranes. TMF1/ARA160 was previously identified by various interaction screens as a DNA-binding protein [9], a hormone receptor co-activator [10] and a component of a chromatin remodelling complex [11]. However, our results provide clear evidence that it behaves as a typical golgin.

Results

Mapping the Ypt6-binding domain of Sgm1

Sgm1 is predicted to have four distinct domains: a long coiled-coil region from about residue 130 to 488, a shorter C terminal coiled-coil from 597 to 707, and non-coiled domains from 1–130 and 488–597 (Figure 1A). We expressed, from the SGM1 promoter in yeast, fusion proteins containing a C-terminal Protein A tag and either full-length Sgm1, or residues 1–488, 488–707 or 597–707. The latter two fragments were expressed less well, but from a multicopy vector they yielded comparable amounts of protein to the full length and 1–488 fragment, which were expressed from a centromere plasmid (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Mapping the Ypt6 binding site on Sgm1 A. Coiled-coil probabilities of the Sgm1 protein sequence, calculated by the method of Lupas using the coils program. The regions analysed for binding are shown diagrammatically below. B. Immunoblot with anti-Protein A of the indicated portions of Sgm1 bound to and eluted from GST-Ypt6 in the GTP and GDP state. Input samples are yeast extract corresponding to about 1% of the total input. The intact protein A fusions are indicated by the arrowheads. Asterisks mark C terminal proteolytic fragments, still fused to protein A, that are common to both the full-length and 488–707 constructs; note that the smallest visible fragment corresponds closely to the 597–707 construct. Proteins apparently larger than the input in the 488–707 lanes presumably represent dimers and other aggregates.

Cell extracts were then incubated with beads containing GST-Ypt6, loaded either with GDP or GTPγS, as previously described [8]. Bound proteins were eluted and detected by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 1B, the full-length Sgm1-protein A bound preferentially to the GTP form of Ypt6, though there was also considerable proteolysis to yield smaller C-terminal fragments that also seemed to bind Ypt6-GTP. The 1–488 fragment did not bind at all to Ypt6. The 488–707 fragment again bound but was extensively degraded, whereas the 597–707 fragment, comprising just the C-terminal coiled coil, bound strongly and selectively to Ypt6-GTP. Indeed, this fusion protein corresponded in size to the smallest prominent Ypt6-binding fragment derived by proteolysis from the full-length and 488–707 constructs. We conclude that the C terminal coiled-coil domain contains the Ypt6 binding site of Sgm1.

TMF is related to Sgm1 and binds Rab6

Using the last 110 residues of Sgm1 we performed iterative BLAST searches and identified clear homologues in other fungi, plants, Drosophila and also in mouse and human. As shown in Figure 2A, the uncharacterised protein sequences from Neurospora, Arabopsis, and Drosophila all share with yeast Sgm1 a similar overall structure consisting of a large coiled-coil region, flanked by short non-coil domains, with a separate short coiled-coil region at the C terminus. The human protein with the strongest similarity to this region is called TMF, for TATA element modulatory factor (Figure 2). Like Sgm1, TMF is a large protein (1093 residues) predicted to consist mainly of coiled-coil. Perhaps significantly, TMF and the other proteins were selected only when the C terminal Ypt6-binding region was included in the homology search. Other parts of Sgm1 seemed no more similar to TMF than they were to other coiled-coil proteins such as myosin. Similarly, there seemed little conservation between species of the non-coil parts of the protein. Figure 2B shows an alignment of the sequences of the C terminal coiled-coil regions of the various homologues.

Figure 2.

Sgm1 homologues are present in a wide range of eukaryotes A. Coiled-coil predictions for various Sgm1-like proteins. Note that each has a distinct 100-residue coiled-coil domain at the C terminus, which in Sgm1 corresponds to the Ypt6-binding domain. The regions of TMF used for binding and antibody production are indicated by lines. The accession numbers for the uncharacterised proteins shown are: Neurospora, CAB97305; Arabidopsis, C96829; Drosophila AAF46211. B. Sequence alignment of the C-terminal coiled coil domains of the proteins depicted in A.

To be able to test whether TMF can bind other proteins, we sought to express it in bacteria. It proved difficult to obtain the full-length protein in E. coli, but we were able to prepare a His-tagged fragment consisting of the C-terminal 310 residues, which includes the region with similarity to Sgm1.

The mammalian homologue of Ypt6 is Rab6, which exists in three forms: Rab6A, Rab6A' (a variant differing from Rab6A only at three residues), and a more divergent Rab6B [12,13]. We produced each of these as GST fusion proteins and performed binding studies with the TMF C terminal fragment. As controls we used GST-Rab1, and also a GST fusion of the yeast protein Ypt52. As shown in Figure 3, TMF bound to all three isoforms of Rab6. There was a preference for the GTP form, though this was modest and quite variable, a phenomenon that is not uncommon amongst Rab effectors. Specificity was demonstrated by the complete lack of binding to Rab1 or Ypt52. These results indicate that TMF is indeed a homologue of Sgm1, and shares its ability to bind a Golgi Rab protein.

Figure 3.

Binding of TMF to Rab6 isoforms A. Immunoblot showing the binding of the His-tagged C-terminal 310 residues of TMF to various GTPases, performed as in Figure 1. B. Coomassie stained gels showing the GTPases used in A, after elution from glutathione-Sepharose.

TMF is a Golgi protein

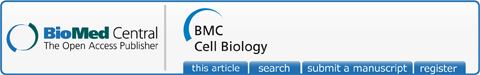

To localise TMF in animal cells, we raised antibodies to its N terminus (residues 1–280). Immunoblotting of cytosolic and Golgi fractions revealed one large protein associated with the Golgi fraction (Figure 4A), consistent with the reported apparent molecular weight of around 150 kDa for TMF [9]. Immunofluorescence with affinity-purified antibodies showed staining typical of the Golgi apparatus in COS cells, with a characteristic ring pattern often seen with golgins (Figure 4B, untransfected). That TMF is associated with Golgi markers was confirmed using NRK cells (see below, Figure 4C). There was also some faint staining of the nucleus in COS cells, but this may represent a weak cross-reaction since it was detected with only one of two different rabbit antisera. We investigated localisation further by expressing an epitope-tagged version of TMF in COS cells (Figure 4B). This again showed Golgi staining, which could be detected identically with anti-TMF and anti-HA antibodies, attesting to the specificity of the anti-TMF antibodies. However, the anti-HA staining did not include the nucleus, and it was striking that even in cells in which the protein was overexpressed, saturating its Golgi binding sites and causing accumulation in the cytoplasm, it tended to be excluded from the nucleus (fourth panel of Figure 4B). Expression of a tagged version of the C-terminal Rab6-binding fragment also resulted in Golgi localisation (Figure 4B), though with this smaller protein some penetration of the nucleus could be observed.

Figure 4.

Location and function of TMF A. Immunoblot of Golgi and cytosol fractions with anti-TMF antibodies. The Golgi lane contained approximately 5 μg total protein, the cytosol lane approximately 100 μg protein. Marker positions (kDa) are indicated. B. Immunofluorescent images of COS cells showing endogenous TMF in an untransfected cell (untransf.), HA-tagged full-length protein expressed from a transfected plasmid (HA-TMF) and detected with both anti-HA and anti-TMF, as well as a cell expressing rather higher levels of HA-TMF (only the anti-HA image is shown; anti-TMF staining of this cell gave an identical pattern). The last panel shows the HA-tagged 310 C-terminal residues of HA (HA-C term) expressed similarly and detected with anti-HA. Bar is 10 μm. C. Rat NRK cells transfected with RNAi and stained for TMF and either TGN38 or GOS28 as indicated. Note that TMF-depleted cells (green in the merged images) have more dispersed Golgi than the other cells. The insets in some panels show an enlarged region of the Golgi, boxed in the merged image. Bars are 10 μm.

Reduced levels of TMF affect Golgi localisation

To test for a possible function of TMF in the Golgi, we used RNAi to deplete it. Because depletion was inefficient in COS cells, we used rat NRK cells for these experiments. Some 10–15% of cells transfected with RNAi oligonucleotides showed significantly lowered levels of TMF, as judged by immunofluorescence. We examined the distribution in these cells of TGN38, a trans-Golgi network protein that recycles via endosomes [14,15], and thus might be expected to require vesicular traffic to the Golgi to maintain its steady-state distribution. In untransfected cells there was close coincidence of TGN38 and TMF staining, though often the TMF staining appeared to surround or be adjacent to the TGN38 (see enlarged insets in Figure 4C). Strikingly, in those cells with relatively low levels of TMF the Golgi frequently appeared more disperse than usual (Figure 4C). Both TGN38 and, where visible, residual TMF were spread in a broad area around the nucleus. Similar results were obtained when cells were stained for GOS28, a SNARE protein found throughout the Golgi stack [16] (Figure 4C). Thus, this phenomenon affects not just the localisation of TGN38, but the compact organisation of the entire ribbon of Golgi stacks.

As the examples in Figure 4C show, NRK cells have variable Golgi morphology. Some have a single patch of tightly-clustered Golgi membranes whereas others, presumably at a different stage of the cell cycle, have a more drawn-out pattern around the nucleus. Defining a compact Golgi structure by a simple criterion, namely that Golgi membranes extend around no more than half the nuclear periphery, we found that 58% of cells with normal levels of TMF had compact Golgi. In contrast, a compact Golgi was observed in only 8% of cells with reduced TMF, estimated from the relative ratio of TMF to TGN38 or GOS28 – that is, cells that appear green in Figure 4C. Furthermore, cells with reduced TMF often had Golgi membranes dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, rather than immediately around the nucleus, as the examples in Figure 4C illustrate. Such a broad spread was almost never seen in normal cells, and conversely the pattern of a single tight patch of Golgi, common in normal cells, was present in less than 5% of the TMF-depleted cells. Thus, we conclude that TMF contributes to the large-scale organisation of Golgi stacks.

Discussion

In this paper we have shown that TMF has similarities to SGM1 in sequence, structure, ability to bind Rab6, and Golgi location. Its properties place it clearly in the category of golgins, and we can conclude that one function of Rab6 is to recruit this golgin. Furthermore, TMF contributes to the overall organisation of the Golgi stacks in NRK cells, suggesting either that it helps them to adhere to each other, or that it facilitates the cytoskeleton-dependent movement of the stacks to their normal pericentriolar location. Interestingly, the only other Rab6-binding golgin known is bicaudal-D, which binds dynactin and has been suggested to mediate the movement of Golgi membranes along microtubules [5]. Possibly, TMF also contributes to this process. In contrast, Sgm1 appears dispensable for Golgi function in budding yeast [8], where Golgi membranes are neither stacked nor restricted to a tight cluster. Golgi stacks are also typically dispersed in Drosophila and plants. However, the presence in a wide range of eukaryotes of proteins with a similar overall structure, and a similar Rab6-binding domain, to that of TMF and Sgm1 suggests that these proteins do play a useful role. It may be that their precise functions differ in different species.

How do the properties of TMF relate to previous studies that implicated it in nuclear roles? TMF has been independently isolated four times. A fragment of it was first found to bind a HIV1 TATA box DNA oligonucleotide in a screen of bacteriophage-expressed proteins, but no in vivo function in HIV transcription was demonstrated [9]. TMF was subsequently found in a yeast 2-hybrid screen as a substrate for the FER nuclear tyrosine kinase, but again no in vivo function or localisation was demonstrated [17]. Interestingly, however, expression of TMF was found to be particularly high in meiotic germ cells; in Drosophila, several mutations in components involved in Golgi transport have been found to have phenotypes restricted largely to such cells, probably because plasma membrane growth is especially rapid during spermatogenesis [18]. Subsequently, TMF was re-isolated in a phage expression screen using a peptide from the androgen receptor as a ligand, and re-named ARA160 [10]. Functional assays showed that strong overexpression of the protein could enhance the activation of a reporter construct by nuclear hormone receptors. This occurred only in certain cell types, even though TMF is present in a wide range of tissues. Finally, a second yeast 2-hybrid screen identified TMF as a binding partner for hSNF2, a component of a chromatin remodelling complex [11]. No functional role was demonstrated for this interaction, and the authors found that most of the protein was associated with the Golgi complex, as we have observed.

These disparate studies fall short of proving a nuclear role for TMF, but they do leave open the possibility that such a role exists, perhaps only in certain cell types and/or for a minor fraction or isoform of the protein that is specifically transported into nuclei. For example, several golgins have been shown to be cleaved during the early stages of apoptosis, resulting in Golgi fragmentation [19-21], and in one case a cleavage product has been found to associate with the nucleus [20]. We did observe some penetration of the nucleus by the C terminal Rab6 binding domain when this was expressed alone. However, in COS cells and NRK cells we found little evidence that full-length TMF could accumulate in nuclei. Given its homology to Sgm1 and other properties, we consider it likely that the primary location and function of TMF lies in the Golgi.

Conclusions

We have shown that the mammalian protein TMF, previously thought to have a nuclear role, binds to the Golgi GTPase Rab6 and contributes to Golgi organisation. It shares an overall coiled-coil structure, as well as a separate Rab6-binding coiled-coil domain, with the yeast protein Sgm1 and with similar proteins in other eukaryotes. The properties of TMF indicate that it should be considered one of the class of Golgi-associated proteins termed golgins.

Methods

Expression of Sgm1, TMF and Rab GTPases in E coli and in vitro binding experiments

His-tagged TMF fragments, and GST fusions to Rab6, Rab1 and Ypt52 were expressed in E. coli, and protein A-tagged Sgm1 fragments in yeast, as described previously [8]. The cDNA for Rab6B was obtained from the MRC HGMP resource centre, Hinxton, UK. Rab6A and Rab1 were gifts from Sean Munro, and Ypt52 a gift from Ewald Hettema. The Rab6A' sequence was created by site-directed mutageneisis of the Rab6A cDNA. The GST fusions were bound to glutathione Sepharose, incubated with GDP or GTPγS and then with E. coli extract (for His-tagged TMF) or yeast extract (for protein A-tagged Sgm1), followed by elution and analysis by immunoblotting as described previously [8]. For rabbit antibody production, the first 280 residues of TMF were expressed as a GST fusion using the pGEX6P2 vector (Amersham). Antibodies were affinity purified on the same fusion protein.

Cell culture and DNA transfections

COS and NRK cells were grown at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, ampicillin and streptomycin in 75-cm Falcon flasks in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator. Transient expression of (HA)2TMF was from the CMV promoter in pCMV2HATMF [17], kindly provided by Uri Nir. The (HA)2TMF C-terminal domain was expressed similarly. For this, cells were plated onto 6-well cell culture clusters, and transfected with 1 μg/well of plasmid DNA, using FUGENE6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were fixed 40 h after transfection as described below.

Immunolocalisation of TMF and Golgi markers

40 h after transfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, washed twice with PBS and then permeabilised for 10 min in PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100, followed by a 30-min blocking with 20% foetal calf serum in PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (blocking solution). The cells were then incubated for 1 hr at room temperature in a wet chamber in blocking solution containing affinity-purified rabbit anti TMF and/or anti-HA mouse mAb 12CA5, or mouse mAbs specific for TGN38 (a gift from P. Luzio) or GOS28 (Transduction Labs) as required. The binding of the antibodies was detected with Alexa 543-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody and FITC fluorescein-conjugated anti-mouse. After each antibody incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS/Tween, incubated with blocking solution for 5 min and again washed twice with PBS/Tween. Immunofluorescence was then analysed with a BioRad Radiance or MRC600 confocal microscope.

Preparation of Golgi membranes

Rat liver were homogenised, equilibrated in 0.5 M phosphate-buffered sucrose and layered on top of a phosphate-buffered 0.86 M sucrose cushion. The homogenate was overlaid with phosphate-buffered 0.25 M sucrose and centrifuged at 105,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The Golgi membranes were collected from the 0.5 M/0.86 M sucrose interface, diluted to 0.25 M sucrose and pelleted by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Cytosol proteins were recovered from the 0.5 M sucrose layer.

RNAi Transfections

Oligonucleotides used for knock-down of TMF were as follows: sense 5'-CAGGUCCUUGAUGGCAAAGdTdT-3' and its antisense: 5'-CUUUGCCAUCAAGGACCUGdTdT-3'. The sense and antisense RNA oligonucleotides (0.1 mM) in 100 mM potassium acetate, 30 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) and 2 mM magnesium acetate, were heated to 90°C for 1 min, then cooled and annealed at 37°C for 1 hr. NRK cells were grown to 50% confluence and were transfected with the annealed RNAi using the reagent Oligofectamine (GIBCOBRL) following the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were fixed 40 h after transfection as described above. Repeated transfection of RNAi did not increase the frequency of cells with depleted TMF.

Authors' contributions

YF-S performed animal cell expression studies, including the RNAi experiments. SS performed the binding assays and deletion analysis. HP contributed to the database searches and microscopy and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Sean Munro, Uri Nir and Ewald Hettema for plasmids, and Alison Gillingham, Katja Schmidt, Helen Stimpson and Steffi Reichelt for reagents and advice. Y.F-S. was the recipient of a FEBS postdoctoral fellowship.

Contributor Information

Yael Fridmann-Sirkis, Email: yaelfs@wicc.weizmann.ac.il.

Symeon Siniossoglou, Email: ss560@cam.ac.uk.

Hugh RB Pelham, Email: hp@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk.

References

- Barr FA, Short B. Golgins in the structure and dynamics of the Golgi apparatus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:405–413. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan BB, Moyer BD, Balch WE. Rab1 recruitment of p115 into a cis-SNARE complex: programming budding COPII vesicles for fusion. Science. 2000;289:444–448. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Ballew N, Barlowe C. Initial docking of ER-derived vesicles requires Uso1p and Ypt1p but is independent of SNARE proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:2156–2165. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, Will E, Gallwitz D. Structural and functional analysis of a novel coiled-coil protein involved in Ypt6 GTPase-regulated protein transport in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:63–75. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short B, Preisinger C, Schaletzky J, Kopajtich R, Barr FA. The Rab6 GTPase regulates recruitment of the dynactin complex to Golgi membranes. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1792–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short B, Preisinger C, Korner R, Kopajtich R, Byron O, Barr FA. A GRASP55-rab2 effector complex linking Golgi structure to membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:877–883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panic B, Perisic O, Veprintsev DB, Williams RL, Munro S. Structural basis for Arl1-dependent targeting of homodimeric GRIP domains to the Golgi apparatus. Mol Cell. 2003;12:863–874. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniossoglou S, Pelham HR. An effector of Ypt6p binds the SNARE Tlg1p and mediates selective fusion of vesicles with late Golgi membranes. EMBO J. 2001;20:5991–5998. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Ou S-HI, Wu F, Lusis AJ, Sparkes RS, Gaynor RB. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of a human immunodeficiency virus 1 "TATA" element modulatory factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9372–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao P-W, Chang C. Isolation and characterization of ARA160 as the first androgen receptor N-terminal-associated coactivator in human prostate cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22373–22379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Kato H. A putative nuclear receptor coactivator (TMF/ARA160) associates with hbrm/hSNF2 alpha and BRG-1/hSNF2 beta and localizes in the Golgi apparatus. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:127–132. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02803-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opdam FJM, Echard A, Croes HJE, van den Hurk JAJM, van de Vorstenbosch RA, Ginsel LA, Goud B, Fransen JAM. The small GTPase Rab6B, a novel Rab6 subfamily member, is cell-type specifically expressed and localised to the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2725–2735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.15.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echard A, Opdam FJM, de Leeuw HJPC, Jollivet F, Savelkoul P, Hendriks W, Voorberg J, Goud B, Fransen JAM. Alternative splicing of the human Rab6A gene generates two close but functionally different isoforms. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3819–3833. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RE, Munro S. Retrieval of TGN proteins from the cell surface requires endosomal acidification. Embo J. 1994;13:2305–2312. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaves B, Banting G. Vacuolar ATPase inactivation blocks recycling to the trans-Golgi network from the plasma membrane. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volchuk A, Ravazzola M, Perrelet A, Eng WS, Di Liberto M, Varlamov O, Fukasawa M, Engel T, Sollner TH, Rothman JE, Orci L. Countercurrent distribution of two distinct SNARE complexes mediating transport within the Golgi stack. Mol Cell Biol. 2004. pp. 1506–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwartz Y, Ben-Dor I, Navon A, Motro B, Nir U. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the TATA element modulatory factor by the FER nuclear tyrosine kinases. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:339–345. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas RM, Giansanti MG, Gatti M, Fuller MT. The Drosophila Cog5 homologue is required for cytokinesis, cell elongation, and assembly of specialized Golgi architecture during spermatogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:190–200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Machamer CE, Roy S, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA, Casciola-Rosen LA, Rosen A. Caspase-2 is localized at the Golgi complex and cleaves golgin-160 during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:603–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu R, Novikov L, Mukherjee S, Shields D. A caspase cleavage fragment of p115 induces fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus and apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:637–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JD, Lucocq J, Pryde J, Barr FA, Woodman PG, Allan VJ, Lowe M. Caspase-mediated cleavage of the stacking protein GRASP65 is required for Golgi fragmentation during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:495–509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]