Abstract

This article shows the supplemental insurance distribution and Medicare spending per capita by insurance status for elderly persons in 1991. The data are from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and Medicare bill records. Persons with Medicare only are a fairly small share of the elderly (11.4 percent). About three-fourths of the Medicare elderly have some form of private insurance. The share with Medicaid is 11.9 percent, which has increased recently as qualified Medicare beneficiaries (QMBs) started to receive partial Medicaid benefits. In general, Medicare per capita spending levels increase as supplemental insurance comes closer to first dollar coverage. When the data were recalculated to control for differences in reported health status between the insurance groups, essentially the same spending differences were observed.

Introduction

This article presents information on supplemental health insurance coverage and Medicare per capita spending levels for Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age or over in 1991. The data are from the MCBS, a continuous panel survey of beneficiaries.1 The data in this article were prepared from a public use data file that links survey data and Medicare administrative bill records. Although Medicare covers both elderly and disabled persons, this article focuses on the elderly.

There is considerable interest in proposals to change Medicare in ways that can slow the growth in program spending. Possible changes to Medicare under consideration include proposals to increase beneficiary cost sharing, restructure Medicare benefits, change the program's financing arrangements, modify the structure of private insurance, or institute cost control programs directed at providers. In conjunction with Medicare, supplemental insurance affects the point-of-service price of care to the beneficiary and thereby influences the beneficiary's access to health services.2 Supplemental insurance also influences the amount of money spent by the Medicare program, since it eliminates or lowers financial barriers to care. Because Medicare is not a closed insurance system, the distribution of supplementary insurance and measurements of the influence of additional insurance on Medicare expenditures are important in evaluating proposals to change Medicare.

We begin with an overview of Medicare. This is followed by a description of the types of supplemental insurance. Then we discuss the 1991 distribution of persons by insurance category from the MCBS. The following section examines past survey data to see the current distribution of supplemental insurance in historical context. We then examine the elderly population's insurance holdings by a number of demographic and health characteristics. The focus then shifts to Medicare spending per person. We examine differences in Medicare spending per person data by insurance category. The spending data is then examined holding health status constant across insurance categories. The article closes with policy implications.

Background

The Design of Medicare

The Medicare program was created in 1965 to provide the elderly with improved access to acute health care services.3 It includes inpatient hospital care, outpatient hospital care, physician care in and out of hospitals, and medical equipment and supplies. Medicare also covers some skilled nursing care, home health services, and hospice care, with a focus on short-term active treatment, not long-term care. Medicare has cost-sharing features including premiums, deductibles, coinsurance payments, and limits on benefits. (For further information see Health Care Financing Administration [1991].) In addition, Medicare does not have an aggregate cap or limit on out-of-pocket expenses for serious and/or long-term illnesses.

Medicare's cost-sharing features were designed to limit program spending. Deductibles and copayments reduce program costs directly, by requiring the beneficiary to pay a share of medical care costs, and indirectly, by establishing out-of-pocket prices that deter use of unnecessary or limited-value services.

Private and Public Supplemental Insurance Development

On average, Medicare covers about 45 percent of the personal health expenditures of the elderly (Waldo, Sonnefeld, McKusick et al., 1989). Over the years, a system of private and public health insurance has developed to cover Medicare cost sharing and non-covered services (Carroll and Arnett, 1979; Cafferata, 1984; Garfinkel and Corder, 1985; Monheit and Schur, 1989). While there are a wide variety of private insurance plans for sale, there are two primary types of private health insurance coverage: employer-sponsored retirement insurance and individually purchased medigap insurance policies (Morrisey, Jensen, and Henderlite, 1990; Rice and McCall, 1985). In addition, Medicare beneficiaries with incomes and assets below certain levels can be entitled to Medicaid benefits (McMillan et al., 1983).

Concern with Medicare Spending Increases

Medicare and the public and private supplemental insurance have greatly improved access to health care services. This access has been maintained during a period when medical care prices and health spending in general have grown much faster than the rest of the economy. Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund expenditures nearly tripled from $25.5 billion in 1980 to $72.6 billion in 1991 (Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 1992). Spending from the Medicare supplementary medical insurance (SMI) program more than quadrupled from $11.2 billion in 1980 to $48.8 billion in 1991 (Board of Trustees of the Supplementary Medical Insurance Fund, 1992). The large increases in spending growth for Medicare and Medicaid are threatening efforts to control the long-term Federal budget deficit (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1992).

Failure of Medicare Catastrophic Insurance Program

Changes to Medicare can be very controversial. The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988 (MCCA), the last attempt to restructure Medicare benefits, was repealed the year after its passage. That program established caps on beneficiary out-of-pocket expenditures and phased in coverage of outpatient prescription drugs under Medicare. The program was financed by additional premiums and higher taxes on the upper income elderly. The political backlash from the elderly caused the program's repeal in 1989.

In retrospect, policymakers may not have clearly understood the supplemental insurance holdings of the elderly. The new Medicare benefits under the MCCA were much less generous than the employer subsidized health insurance retirement benefits held by a significant share of the elderly (Morrisey, Jensen, and Henderlite, 1990). A survey of the elderly conducted after the repeal of the MCCA found that satisfaction with private insurance was highest among persons who already had supplemental coverage from a former employer (Rice, Desmond, and Gabel, 1990). In effect, many of the higher income elderly were being asked to pay higher premiums and taxes, but would not be receiving any new insurance benefits.

Types of Medicare Supplemental Insurance

Employer-Sponsored Retirement Health Benefits

Employer-sponsored retirement health benefits did not become a common part of the retirement benefits package until after Medicare was created. In the 1970s and early 1980s employers rapidly expanded these benefits (Clark and Kreps, 1989). Because Medicare is the first payer for persons age 65 or over who have retired, the employer's liability for retirees is more limited than for current employees.

Most health retirement plans continue benefits at the same level as those offered to current employees (Chollet, 1989). This can be very advantageous to the retiree because the employer pays part or all of the premiums. These plans also often cover services that are not covered under Medicare, such as prescription drugs. In many plans members face cost sharing. They are responsible for the lower of either Medicare or the private plan deductibles and coinsurance. However, whether they actually pay these out-of-pocket costs depends on how the plan coordinates its benefits with Medicare (Morrisey, Jensen, and Henderlite, 1990).

Individually Purchased Medigap Insurance

This type of insurance focuses on the gaps in Medicare coverage. Individual medigap policies can vary widely in their coverage. All policies are required to cover Medicare coinsurance costs except coinsurance for skilled nursing facility (SNF) stays. These plans are not required to cover deductibles.

However, the typical medigap plan usually covers all coinsurance costs under Medicare including SNF coinsurance and the hospital insurance deductible. Some medigap plans also cover the SMI deductible, thereby wrapping around Medicare to eliminate virtually ail cost sharing. Most medigap plans do not cover “balance billing” amounts by physicians and other SMI providers. These are amounts higher than Medicare-approved charges on claims where physicians or other providers have not agreed to accept the Medicare approved amounts as full payment. In addition, unlike many employer-sponsored health plans, the typical medigap plan does not cover outpatient prescription drugs or other services not covered by Medicare (Rice and McCall, 1985). The average premiums for a medigap plan were estimated to be $664 in 1991 (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1991).

Medicare and Medicaid Dual Eligibles

These are persons who qualify for cash payments from public assistance programs such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), or who qualify as medically needy under guidelines in their State, or who qualify for limited Medicaid benefits based on low income and low assets. This latter group is known as QMBs. Medicare is the primary payer for persons with Medicaid or QMB benefits. The State Medicaid program typically “buys-in”, that is, pays the Medicare premiums for these persons and pays all Medicare cost-sharing amounts. For QMBs, this was the extent of required coverage in 1991.4 (States can choose to extend additional health benefits to QMBs.) In contrast to QMBs, fully qualified dual enrollees are entitled to any additional Medicaid services offered in their State, such as prescription drugs and long-term care.

Historically, persons with dual entitlement have not been representative of the rest of the Medicare population. There are disproportionately high shares of the very old, minority races, females, and persons in poor health (McMillan, Pine, Gornick, et al., 1983; McMillan and Gornick, 1984).

Medicare Only

These are persons whose only health insurance is Medicare. One important question about this group is whether facing full Medicare cost sharing deters the use of needed services. A related question is whether these persons have only Medicare coverage as a matter of choice (they choose to self insure), or because they do not qualify for Medicaid but do not have the means to purchase private insurance.

This group also serves an important analytic purpose. Medicare was created to provide the elderly access to acute care services. However, it was created with deductibles and coinsurance to deter unnecessary use of services and require beneficiary cost sharing. In that sense, the Medicare-only group serves as a base-line measure of use and costs as intended under the original legislation. This is not to say, as the data below will indicate, that the Medicare-only group is representative of the entire Medicare population. Only that if the objective is to measure the effect of supplementary insurance on Medicare spending, persons with no supplementary insurance are the natural comparison group.

Elderly Populations Supplemental Insurance Status

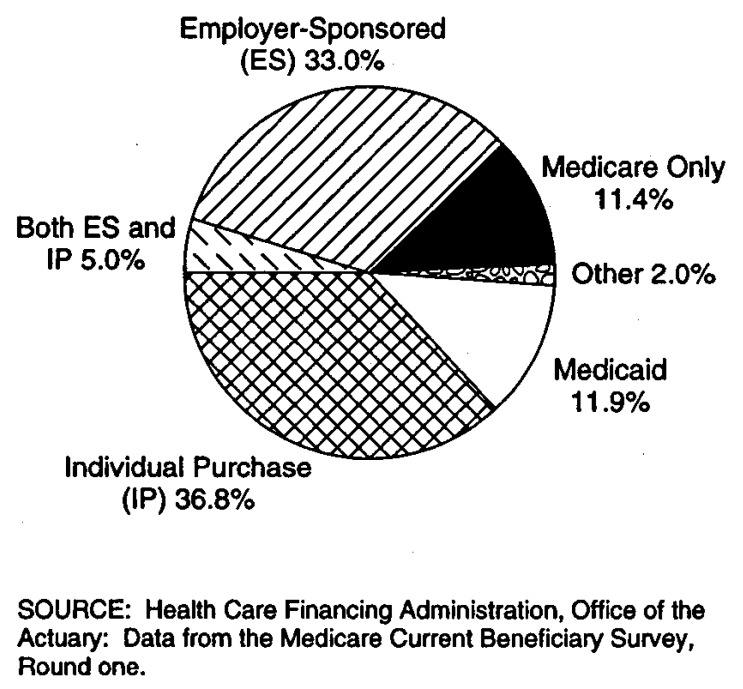

Figure 1 shows the share distribution of the elderly Medicare population by their supplemental insurance status as reported in round one of the MCBS.

Figure 1. Supplementary Health Insurance for Medicare Elderly: 1991.

Medicare only persons are 11.4 percent of the elderly, or about 1 out of every 9 beneficiaries.

About 75 percent of elderly Medicare beneficiaries have some form of private insurance to supplement Medicare. One-third (33.0 percent) of the elderly supplement Medicare with only employer-sponsored private insurance. Nearly 37 percent of the elderly have only individually purchased private policies to supplement Medicare. Another 5.0 percent of the elderly have both employer-sponsored and individually purchased private insurance.

Persons with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid were 11.9 percent of the elderly in 1991.

About 2 percent of persons had some other form of supplemental insurance, including public insurance that was not Medicaid, or private insurance which could not be identified as employer-sponsored or medigap insurance.

Previous Survey Distributions

Table 1 shows distributions of persons 65 years of age or over by supplemental insurance status as reported from major surveys during the last 15 years. This includes the National Medical Care Expenditure Survey (NMCES), the Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey (MCUES), the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), and the National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES).

Table 1. Survey Distributions of Persons 65 Years of Age or Over, by Insurance Status: 1977-91.

| Year and Survey | Total | With Private Insurance | Employer-Sponsored | Individual Purchase | Without Private Insurance | Medicare Only | Medicare and Medicaid | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 NMCES | 100.0 | 65.2 | 23.7 | 41.5 | 34.8 | 20.4 | 10.6 | 3.8 |

| 1980 MCUES | 100.0 | 64.9 | NA | NA | 35.1 | 21.2 | 10.2 | 3.7 |

| 1984 SIPP | 100.0 | 70.0 | 29.8 | 40.2 | 30.0 | 19.9 | 7.9 | 2.2 |

| 1987 NMES | 100.0 | 75.4 | 34.8 | 40.6 | 24.6 | 11.2 | 7.6 | NA |

| 1991 MCBS | 100.0 | 74.8 | 38.0 | 36.8 | 25.2 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

NOTES: NA is not available. NMCES is National Medical Care Expenditure Survey. MCUES is Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey. SIPP is Survey of Income and Program Participation. NMES is National Medical Expenditure Survey. MCBS is Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Previous surveys did not publish a separate share of persons with both types of private insurance. The 1991 MCBS 5.0 percent share of persons with both types of private insurance have been added into the employer-sponsored share to make comparisons easier.

SOURCES: 1977 NMCES data from (Cafferata, 1984); 1980 NMCUES data from (Garfinkel and Corder, 1985) 1984 SIPP data from (Del Bene and Vaughan, 1992) 1987 NMES private insurance data from (Monheit and Schur 1989); Medicare only and Medicare and Medicaid shares derived from (Lefkowitz and Monheit, 1991).

The share of elderly persons with private supplemental insurance increased from 65 percent in 1977 to 75 percent in 1987. The 1991 MCBS share is virtually identical with the share measured in 1987 from the NMES, suggesting that the upward trend in private health insurance from 1977 to 1987 may have leveled off.

Employer-sponsored retirement benefits increased from 24 percent in 1977 to 35 percent in 1987. In 1991, the share increased to 38 percent of the elderly. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Rule 106, which was first announced in 1989 and takes effect for most firms in 1993, requires corporations to currently account for the cost of future employee and retiree medical benefits (Stern, 1991). This requirement will increase balance sheet liabilities for corporations who have large retiree populations and/or generous health benefit plans. Corporations are seriously reconsidering their commitments to retiree health benefit plans. However, predictions that the rule would decrease the employer-sponsored share are not reflected in the aggregate 1991 data. (We will examine changes for the 65-69 age group in the following section. The youngest elderly would be most affected by any recent changes in employer policies toward retiree health benefits, since court decisions have put limits on employers ability to change retirement benefits for current retirees [Chollet, 1989]).

The share of persons with individually purchased plans stayed steady at or slightly above 40 percent from 1977 to 1991 (adding in the 5.0 percent with both types of private insurance in 1991).

There was a consistent share of about 20 percent of elderly persons who have only Medicare insurance coverage between 1977 and 1984; however, this share dropped to 11 percent in 1987. The MCBS 1991 figure of 11.4 percent is virtually identical with the 1987 NMES. This suggests that the Medicare only share is fairly small, and that this share has been stable in recent years.

The dual eligible share was reported to be about 8 percent in the surveys conducted in 1984 and 1987. The share increased to 11.9 percent in 1991. One probable reason for the increase in the share of Medicaid eligibles is the QMB program created by Congress in 1989.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Supplemental Insurance Coverage

The distribution of supplemental insurance varies across different characteristics of the elderly population. Tables 2 through 6 show the insurance distribution by age, sex, race, health status, and usual source of health care.

Table 2. Supplemental Medical Insurance of Medicare Elderly, by Age: 1991.

| Age Group | Percent of Enrollees | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer-Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicaid | Medicare and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons in Thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 29,176 | 3,324 | 10,725 | 9,621 | 1,467 | 3,459 | 581 |

| 65-69 Years | 29.4 | 8,570 | 954 | 2,817 | 3,553 | 498 | 676 | 72 |

| 70-74 Years | 27.2 | 7,931 | 817 | 3,034 | 2,842 | 442 | 702 | 95 |

| 75-79 Years | 20.0 | 5,840 | 633 | 2,319 | 1,826 | 264 | 666 | 131 |

| 80-84 Years | 13.4 | 3,897 | 460 | 1,579 | 946 | 167 | 626 | 119 |

| 85 Years or Over | 10.1 | 2,938 | 460 | 975 | 454 | 96 | 790 | 164 |

| Insurance Percent Share | ||||||||

| Total | — | 100.0 | 11.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

| 65-69 Years | — | 100.0 | 11.1 | 32.9 | 41.5 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 0.8 |

| 70-74 Years | — | 100.0 | 10.3 | 38.3 | 35.8 | 5.6 | 8.9 | 1.2 |

| 75-79 Years | — | 100.0 | 10.8 | 39.7 | 31.3 | 4.5 | 11.4 | 2.2 |

| 80-84 Years | — | 100.0 | 11.8 | 40.5 | 24.3 | 4.3 | 16.1 | 3.1 |

| 85 Years or Over | — | 100.0 | 15.7 | 33.2 | 15.5 | 3.3 | 26.9 | 5.6 |

NOTES: Includes Medicare persons age 65 or over who were alive during all of 1991. All numbers have relative standard errors of less than 30 percent.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, round one.

Table 6. Supplemental Medical Insurance of Medicare Elderly, by Usual Source of Health Care: 1991.

| Usual Source of Care | Source Share | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer- Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicaid | Medicare and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons in Thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 29,176 | 3,324 | 10,725 | 9,621 | 1,467 | 3,459 | 581 |

| No Usual Source | 8.5 | 2,482 | 633 | 800 | 705 | 91 | 233 | 122 |

| Doctor's Office | 75.3 | 21,977 | 1,880 | 8,844 | 7,861 | 1,273 | 1,870 | 249 |

| Clinic | 6.7 | 1,947 | 149 | 800 | 738 | 75 | 167 | 117 |

| Hospital | 3.3 | 953 | 258 | 211 | 237 | 123 | 198 | 126 |

| Other | 6.2 | 1,818 | 404 | 70 | 79 | 14 | 992 | 269 |

| Insurance Percent Share | ||||||||

| Total | — | 100.0 | 11.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

| No Usual Source | — | 100.0 | 25.5 | 32.2 | 28.4 | 3.7 | 9.4 | 10.8 |

| Doctor's Office | — | 100.0 | 8.6 | 40.2 | 35.8 | 5.8 | 8.5 | 1.1 |

| Clinic | — | 100.0 | 7.7 | 41.1 | 37.9 | 3.9 | 8.6 | 11.3 |

| Hospital | — | 100.0 | 27.1 | 22.1 | 24.9 | 12.4 | 20.8 | 12.7 |

| Other | — | 100.0 | 22.2 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 10.2 | 54.6 | 14.8 |

Relative standard error of 30 percent or more.

NOTES: Doctor's office category includes doctor's offices and doctor's clinics. Clinic category includes health maintenance organizations, family health centers, rural health clinics, company clinics, other clinics, and urgent centers. Hospital category includes hospital emergency rooms and hospital outpatient departments. Other category includes at home, veteran affairs facilities, nursing homes, mental health facilities, and unspecified. Includes Medicare persons age 65 or over who were alive during all of 1991.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, round one.

Age

Elderly persons are not distributed equally across age categories (Table 2). The highest proportion of persons are ages 65-69 (29.4 percent), and this proportion declines with increasing age. Persons 85 years of age or over are 10.1 percent of the elderly.

The Medicare only shares cluster around the national average (11.4 percent) in age groups from 65-84. An above average share of persons 85 years or over (15.7 percent) have Medicare as their only health insurance.

The share of persons with individually purchased private insurance increases from age 65-69 (32.9 percent) to age 80-84 (40.5 percent), then drops somewhat at age 85 or over (33.2 percent). This pattern is reversed for employer-sponsored private insurance. The employer-sponsored share is highest at age 65-69 (41.5 percent), then drops steadily until it reaches a low of 15.5 percent for persons age 85 or over. This reflects the fact that a larger proportion of younger retirees have post retirement benefits than older retirees.

In general, the elderly respond to less employer-sponsored insurance by purchasing more individual private supplemental policies until age 85. Older retirees who purchase individual insurance do not have premium subsidies from former employers or (usually) coverage of prescription drugs or other services not covered by Medicare. In general terms, as age increases there is a smaller share of the elderly with private insurance, these persons hold a less rich blend of insurance as individual plans replace employer-sponsored plans, and there is an increase in the elderly's financial responsibility for insurance premiums.

As previously mentioned, there is a question whether employers will respond to FASB Rule 106 by reducing health insurance benefits for their retirees. Any recent corporate decisions to eliminate retirement health insurance would most likely show up in the data for the 65-69 age group, who became eligible for Medicare in the period 1986-90. In Table 2, 47.3 percent of persons age 65-69 had employer-sponsored insurance (including those with both private types). This was 5 percentage points higher than the share for persons age 70-74 (42.4 percent) who enrolled in Medicare in 1981-85. This data show no lessening of employer support for retiree health insurance, either in the aggregate for the whole population, or at the margin with persons age 65-69.

The share of persons with both Medicare and Medicaid benefits increases with age. About 8 percent of persons age 65-69 are entitled to Medicaid and this share increases to 16.1 percent of persons age 80-84. At age 85 or over, there is a sharp increase to 26.9 percent of persons with Medicaid. The large share of persons in the age 85 or over group with Medicaid probably reflects proportionately more persons of this age group in nursing homes. Nursing home benefits are often covered by Medicaid, either because the beneficiary was poor upon entering the facility or because the costs of the stay have depleted their financial assets and they qualify as medically needy. (Future MCBS reports will examine nursing home patterns of use and financing by the elderly.)

Sex

There are considerably more females (60 percent) than males (40 percent) in the Medicare population over age 65 (Table 3). This is because females live several years longer than males on average.

Table 3. Supplemental Medical Insurance of Medicare Elderly, by Sex: 1991.

| Sex | Sex Share | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer-Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicaid | Medicare and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons in Thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 29,176 | 3,324 | 10,725 | 9,621 | 1,467 | 3,459 | 581 |

| Male | 40.0 | 11,666 | 1,610 | 3,934 | 4,408 | 636 | 866 | 211 |

| Female | 60.0 | 17,511 | 1,714 | 6,790 | 5,212 | 831 | 2,594 | 370 |

| Insurance Percent Share | ||||||||

| Total | — | 100.0 | 11.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

| Male | — | 100.0 | 13.8 | 33.7 | 37.8 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 1.8 |

| Female | — | 100.0 | 9.8 | 38.8 | 29.8 | 4.7 | 14.8 | 2.1 |

NOTES: Includes Medicare persons age 65 or over who were alive during all of 1991. All numbers have relative standard errors of less than 30 percent.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, round one.

A larger share of males (13.8 percent) than females (9.8 percent) have Medicare as their only health insurance. This may be because a higher proportion of females have Medicaid coverage.

Males have a higher share of employer-sponsored supplemental insurance (37.8 percent) than females (29.8 percent). Proportionately more females (38.8 percent) than males (33.7 percent) have individually purchased supplemental policies. The larger share of elderly males with employer-sponsored insurance probably reflects their greater participation in paid employment with retirement benefits. The larger share of females with individually purchased policies could reflect, at least in part, the need for many widows to purchase insurance to replace employer-sponsored coverage when the husband dies.

The share of females (14.8 percent) entitled to Medicaid benefits is double the share of males (7.4 percent). Since females live longer on average, more very elderly females may find themselves in financially reduced circumstances and/or with health needs that require long-term nursing care. In addition, more females than males did not work long enough in covered employment under Social Security to obtain pensions.

Race

The elderly Medicare population consists of 88.9 percent of the white race, 7.9 percent of the black or African-American race, and 3.2 percent of all other races (Table 4).

Table 4. Supplemental Medical Insurance of Medicare Elderly, by Race: 1991.

| Race | Percent of Enrollees | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer- Sponsored | Private—Both | Medicaid | Medicare and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons in Thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 29,176 | 3,324 | 10,725 | 9,621 | 1,467 | 3,459 | 581 |

| White | 88.9 | 25,949 | 2,514 | 10,119 | 8,987 | 1,407 | 2,397 | 525 |

| Black or African American | 7.9 | 2,294 | 657 | 420 | 463 | 138 | 683 | 133 |

| All Other | 3.2 | 933 | 153 | 186 | 171 | 122 | 379 | 123 |

| Insurance Percent Share | ||||||||

| Total | — | 100.0 | 11.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

| White | 100.0 | 9.7 | 39.0 | 34.6 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 2.0 | |

| Black or African American | — | 100.0 | 28.6 | 18.3 | 20.2 | 11.7 | 29.8 | 11.4 |

| All Other | 100.0 | 16.4 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 12.4 | 40.6 | 12.5 | |

Relative standard error of 30 percent or more.

NOTES: Includes Medicare persons age 65 or over who were alive during all of 1991.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, round one.

The proportion of black persons with Medicare only is three times higher (28.6 percent) than the proportion of white persons (9.7 percent). Persons of all other races also had a high proportion (16.4 percent) relative to white persons. If having only Medicare creates a financial barrier to receiving care, other races are more likely to face this barrier than the white race.

In both the individual and employer-sponsored insurance groups, white persons had shares that were about double that of black persons and all other races. Adding the separate private insurance shares together, 79.1 percent of white persons had some form of private supplemental insurance, nearly double the privately insured shares for black persons (40.1 percent) and persons of all other races (40.6 percent). Races other than white elderly probably did not work as extensively as white persons in employment that carried retirement health benefits. The lower shares of individually purchased private insurance for all other races may reflect lower incomes for elderly minority persons.

Compared with white persons (9.2 percent), the proportion of black persons entitled to Medicaid (29.8 percent) is more than three times higher, and the share of all other races is more than four times as high (40.6).

Health Status

All survey respondents were asked how they would rate their health on a five-point scale from excellent to poor. The distribution of the Medicare elderly by self-reported health status is as follows: 40.9 percent reported very good or excellent health; 30.0 percent reported good health; 20.5 percent reported fair health; and 8.4 percent reported poor health (Table 5).

Table 5. Supplemental Medical Insurance of Medicare Elderly, by Health Status: 1991.

| Health Status | Percent of Enrollees | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer-Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicaid | Medicare and Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons in Thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 29,176 | 3,324 | 10,725 | 9,621 | 1,467 | 3,459 | 581 |

| Excellent | 17.0 | 4,963 | 526 | 2,025 | 1,840 | 292 | 236 | 44 |

| Very Good | 23.9 | 6,967 | 615 | 2,770 | 2,655 | 417 | 391 | 119 |

| Good | 30.0 | 8,745 | 891 | 3,274 | 3,015 | 468 | 946 | 154 |

| Fair | 20.5 | 5,972 | 811 | 1,903 | 1,590 | 237 | 1,229 | 201 |

| Poor | 8.4 | 2,464 | 465 | 737 | 498 | 53 | 649 | 62 |

| Insurance Percent Share | ||||||||

| Total | — | 100.0 | 11.4 | 36.8 | 33.0 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 2.0 |

| Excellent | — | 100.0 | 10.6 | 40.8 | 37.1 | 5.9 | 4.8 | 0.9 |

| Very Good | — | 100.0 | 8.8 | 39.8 | 38.1 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 1.7 |

| Good | — | 100.0 | 10.2 | 37.4 | 34.5 | 5.4 | 10.8 | 1.8 |

| Fair | — | 100.0 | 13.6 | 31.9 | 26.6 | 4.0 | 20.6 | 3.4 |

| Poor | — | 100.0 | 18.9 | 29.9 | 20.2 | 2.2 | 26.3 | 2.5 |

NOTES: Cells will not add to total because health status was not reported for 0.2 percent of persons. Includes Medicare persons age 65 or over who were alive during all of 1991. All numbers have relative standard errors of less than 30 percent.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, round one.

The Medicare only insurance group has larger than average shares of persons who do not report good health. For example, 38.4 percent of Medicare only persons are in fair or poor health compared to 28.9 percent of all enrollees. Persons with only Medicare represent 13.6 percent of persons in fair health and 18.9 percent of persons in poor health. Other things equal, persons in fair or poor health need supplemental health insurance more than healthier people. Under current arrangements the less healthy seem to have less insurance.

In both the individual and employer insurance groups, the share with insurance becomes smaller as health status worsens. Adding the private insurance categories together, an 83.8 percent share of persons with excellent or very good health have some form of private insurance. By comparison, only 52.3 percent of persons who report poor health have some type of private supplemental insurance. Self-reported health status can be considered an indicator of the need for health care services. As private insurance is presently distributed among the elderly, it provides more support to healthier persons than to those who are presumably more in need of health care.

The share of persons entitled to Medicaid is clearly related to self-reported health status: it increases as health status declines. Among persons in excellent health, only 4.8 percent have Medicaid coverage. More than one-fourth (26.3 percent) of persons in poor health have Medicaid. Many people qualify for Medicaid benefits as medically needy after their health care expenses have depleted their financial assets to legally determined levels (often referred to as “spend down”). This is consistent with the finding that as health status declines, greater shares of persons have Medicaid coverage.

Usual Source of Care

Beneficiaries were asked if they had a usual source of care they used when they needed health care treatment. More than three-fourths of persons (75.3 percent) said their usual source of care was a physician's office (Table 6). About 1 in 12 persons (8.5 percent) said they had no usual source of care. Other usual sources include 6.7 percent who use clinics, 3.3 percent who use hospital emergency rooms or hospital outpatient departments, and 6.2 percent who use other locations.

Persons with no usual source of care (25.5 percent), or who use the hospital (27.1 percent) are about three times more likely to be Medicare only than persons who use a physician's office (8.6 percent) or a clinic (7.7 percent) for their routine health care. This suggests that persons with only Medicare coverage have weaker links to a personal physician than those with more complete insurance coverage.

The distributions by usual source are similar for individual and employer insurance groups. The largest proportions of privately insured persons have a physician's office or clinic as their usual source of care. Private insurance tends to strengthen a beneficiary's link to a personal physician.

About 1 in 5 (20.8 percent) persons who use a hospital as their usual source is eligible for Medicaid. More than one-half (56.2 percent) of persons who use “other” locations are eligible for Medicaid. This extremely high share for “other” location is due to Medicaid persons who are in institutions, most of whom have nursing homes as their usual source of care.

Services and Spending Per Capita Use

There is a continuing question about the impact of supplemental insurance on Medicare spending (Link, Long, and Settle, 1980; Christensen, Long, and Rodgers, 1987; Taylor, Short, and Horgan, 1988; Scheffler, 1988; U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1991). Supplemental insurance coverage can influence the use of Medicare services in two ways. It can affect the decision whether to use Medicare services at all. For persons who decide to use services, it can influence the level of their use and spending. In this article, we compare spending per person for Medicare only persons to persons in other private or public supplemental insurance categories. The differences in average spending per person are baseline measures of the effect of supplemental insurance on Medicare spending. Table 7 shows the shares of persons using services and average Medicare spending per person in 1991 by supplemental insurance category.

Table 7. Percent Using Medicare Reimbursed Services and Medicare Spending per Person, by Supplemental Medical Insurance Age 65 or Over: 1991.

| Item | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer- Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicare and Medicaid | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Persons | |||||||

| All Medicare Persons Age 65 or Over | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Using no Reimbursed Services | 16.6 | 33.3 | 13.3 | 17.5 | 13.9 | 9.3 | 9.4 |

| Using Reimbursed Services | 83.4 | 66.7 | 86.7 | 82.5 | 86.1 | 90.7 | 90.6 |

| Hospitalized in Year | 17.5 | 13.2 | 17.6 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 26.0 | 33.1 |

| Using Other Reimbursed Services | 65.9 | 53.4 | 69.1 | 67.3 | 70.4 | 64.7 | 57.6 |

| Medicare Spending per Person | |||||||

| All Persons | $2,782 | $1,992 | $2,837 | $2,260 | $3,099 | $4,379 | $4,532 |

| Persons Hospitalized in Year | 12,456 | 12,136 | 12,705 | 11,214 | 15,956 | 13,239 | 12,266 |

| Persons Using Other Reimbursed Services | 909 | 721 | 865 | 832 | 840 | 1,450 | 826 |

NOTES: Medicare program spending for covered services for persons in sample during all of 1991. Excludes persons who died in 1991; excludes health maintenance organization and managed care enrollees; excludes services not covered by Medicare; excludes payments by beneficiaries and supplementary insurers. All numbers have relative standard errors of less than 30 percent.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey and Medicare Billing Records.

Complete definitions and qualifications of the Medicare per capita spending data appear in the Data Sources and Methods section. To summarize here, these are Medicare program payment amounts for Medicare covered services for persons alive during all of 1991. These are not total health care spending amounts for all services from all payers.

Use of Services

One-third (33.3 percent) of persons with Medicare only used no reimbursed Medicare services (Table 7). This non-user share was much higher than any other insurance category. The next largest share of non-users was in the employer-sponsored group where 17.5 percent of persons, about one-half of the Medicare only share, used no covered services. Only 9.3 percent of persons with both Medicare and Medicaid used no Medicare-covered services.

On average, 83 percent of all Medicare elderly used one or more reimbursed services in 1991. By insurance category, the lowest share was for Medicare only where 2 out of 3 persons used reimbursed services. At the other extreme, 9 out of 10 persons in the Medicare and Medicaid dual eligible category used Medicare reimbursed services.

Overall per capita spending levels are heavily influenced by inpatient hospital use, the most expensive Medicare service. The lowest share of persons using inpatient hospital care occurred in the Medicare only category (13.2 percent). The share of persons with Medicare and Medicaid who were hospitalized was about double (26.0 percent) that level. Depending on the category, about 15 to 18 percent of persons with private supplemental insurance were hospitalized in 1991.

Persons who use reimbursed Medicare services such as physician care, but who were not hospitalized, are in the largest category of elderly persons. Again, the smallest share of service users is in the Medicare only category (53.4 percent). This share is substantially below the private insurance groups where 67 to 70 percent used reimbursed services other than inpatient care. The share of Medicare and Medicaid persons is slightly lower at 64.7 percent. However, this relatively low share using non-hospital services only is due in part to the high share using hospital services, not lower levels of overall use by those with Medicaid.

Spending per Capita

Average Medicare program spending per person for all elderly was $2,782 in 1991 (Table 7). (A discussion of what is included and excluded from this figure appears in the Data Sources and Methods section at the end of this article). The lowest per capita spending, $1,992, occurred for persons with no supplemental insurance. Spending for this Medicare only group was 28 percent below the national average.

Average per capita spending for persons with employer-sponsored insurance was $2,260, 19 percent below the national average. This is the only other insurance category in which many (but not all) persons are responsible for deductibles and copayments under either their private insurance or Medicare.5 As previously noted, this group is younger on average than other insurance groups. We applied the employer-sponsored age specific spending rates to the total population age distribution to test whether younger age or insurance characteristics were influencing the below average spending. The age adjusted per capita spending for the employer-sponsored group was still 15 percent below the national average, implying that younger age explains 4 percent of the 19 percent difference.

The individual purchase private insurance category was very close to the national average in per capita Medicare spending ($2,837). Persons holding both individually purchased and employer-sponsored plans had per capita spending about 11 percent above the national average ($3,099).

Persons with both Medicare and Medicaid showed average Medicare spending figures nearly 60 percent above average ($4,379). The relatively high figure for this group undoubtedly reflects not only good insurance coverage, but the higher health care needs of an older, sicker, and poorer population. The small other category consists of persons with Medicare and government-sponsored programs other than Medicaid, or private insurance which could not be classified by type. This group had per capita spending levels very close to the Medicare and Medicaid group.

Spending per person for those hospitalized is fairly consistent across insurance categories, except for persons with both types of private insurance ($15,596). The remaining insurance categories fall into the $11,200 to $13,200 per capita range.

Among those using services but not hospitalized, the Medicare only group has the lowest average per capita reimbursement ($721). Medicare and Medicaid dual eligibles per capita spending is double that amount ($1,450). Spending per person in the private insurance categories is in the $830 to $860 range, well above the Medicare only category, but far below the dual eligibles.

Discussion

These data strongly suggest that as responsibility for Medicare out-of-pocket payments declines, average Medicare spending per person increases. This increased spending comes from two effects, increases in the overall share using reimbursed services and higher spending levels among users. Among the most expensive patients, those who are hospitalized, there is more variation in the share using services than in per capita spending levels. For non-hospitalized users of Medicare reimbursed services, type of insurance affects both the share using services and the level of spending per user.

There are two criticisms that can be directed at the findings in Table 7. One is the possibility of self selection in insurance status categories. Briefly stated, the argument is that persons who know they will be using health care obtain supplemental insurance to finance their care. For this reason, the difference in spending per person between persons with Medicare only and the other insurance categories may overstate the effect of insurance. On the other hand, after age 65 there are few persons who can be sure they will not need health care in the next year. In addition, an uninsured person who develops a serious health condition risks being denied insurance because of a pre-existing condition. For these reasons, the self-selection problem is probably smaller for elderly persons than for those who are younger. On balance, however, it would be wise to consider the differences in spending between the Medicare only and the insured categories as outside estimates, or upper limits.

A related but more manageable problem is that there may be systematic differences in the characteristics of persons in insurance categories, apart from differences in their insurance, that affects their use of services and Medicare spending. For example, the relatively high spending levels for persons with Medicare and Medicaid reflect not only better insurance, but also the presence of more persons that are older and in poorer health. Similarly, the relatively low average spending level for Medicare only persons could be due to a larger proportion of very healthy persons. The usual approach to this problem is to create a multivariate model which measures differences in spending per person while statistically controlling for identifiable differences in the populations. In future analyses of MCBS data, we will model spending data in that way. In order to partially address this difficulty, we have cross-tabulated per capita spending by supplemental insurance category and self-reported health status. This allows comparisons of insurance category spending differences holding health status constant.

Health Spending by Health Status

Self-assessed health status has consistently been shown to be highly significant in explaining differences in use of health services and health spending (Christensen, Long, and Rodgers, 1987; Taylor, Short, and Horgan, 1988; Dunlop, Wells, and Wilensky, 1989). Self-assessed health status has also been shown to have an independent effect, apart from identified health conditions, disability, and the life style risk factors, in predicting an individual's mortality (Idler and Kasl, 1991).

Medicare health spending per person rises sharply as reported health status declines (Table 8). Average Medicare spending per person for persons in excellent health is below one-half (0.42) of the national average. Persons in good health are slightly below the national average (0.92). Persons in poor health, by contrast, have Medicare spending levels about 2.5 times the national average. The pattern of increased spending per person as health status declines is consistent within each insurance category. These figures suggest that classifying by health status separates the elderly into clearly distinct health spending categories.

Table 8. Medicare Spending per Person for Age 65 or Over, by Insurance Category by Health Status: 1991.

| Health Status | Percent of Enrollees | Total | Medicare Only | Private Individual Purchase | Private Employer- Sponsored | Private— Both | Medicare and Medicaid | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending per Person | ||||||||

| All Persons | 100.0 | $2,782 | $1,992 | $2,837 | $2,260 | $3,099 | $4,379 | $4,532 |

| Excellent | 16.6 | 1,181 | 705 | 1,102 | 1,217 | 12,008 | 1,694 | 1524 |

| Very Good | 23.7 | 1,702 | 905 | 1,780 | 1,490 | 2,172 | 2,809 | 13,659 |

| Good | 30.2 | 2,558 | 1,713 | 2,607 | 2,347 | 2,739 | 3,597 | 3,660 |

| Fair | 20.7 | 3,817 | 2,462 | 3,869 | 3,236 | 4,864 | 4,741 | 6,528 |

| Poor | 8.6 | 7,143 | 4,684 | 9,569 | 6,477 | 1$11,513 | 6,714 | 4,388 |

| Ratio of Spending to All Persons Average | ||||||||

| All Persons | — | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.11 | 1.57 | 1.63 |

| Excellent | — | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 10.72 | 0.61 | 11.01 |

| Very Good | — | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 1.01 | 11.32 |

| Good | — | 0.92 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 1.29 | 1.32 |

| Fair | — | 1.37 | 0.88 | 1.39 | 1.16 | 1.75 | 1.70 | 2.35 |

| Poor | — | 2.57 | 1.68 | 3.44 | 2.33 | 14.14 | 2.41 | 1.58 |

Relative standard error of 30 percent or more.

NOTES: Medicare program spending for covered services for persons in sample during all of 1991. Excludes persons who died in 1991; excludes health maintenance organization (HMO) and managed care enrollees; excludes services not covered by Medicare; excludes payments by beneficiaries and supplementary insurers. Health status distribution differs from Table 5 because HMO members are excluded.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey and Medicare Billing Records.

Looking across the health status rows in Table 8, the lowest spending per person is always in the Medicare only category. The second lowest per capita spending figures are for employer-sponsored insurance (except in the excellent health category). The next higher spending per person figures are for persons with individually purchased insurance. Per capita spending figures are even higher for persons with both individually purchased and employer-sponsored private supplemental insurance. The highest per capita spending figures are usually for persons with both Medicare and Medicaid. These figures reinforce the basic patterns found in Table 7. They further support the conclusion that Medicare supplemental insurance that covers Medicare deductibles and copayments increases Medicare spending on health care.

Policy Implications

One reliable, if politically difficult, way to reduce the aggregate demand for health services by the Medicare population would be to increase the point-of-service cost sharing for Medicare covered services (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1991; Taylor, Short, and Horgan, 1988; Christensen, Long, and Rodgers, 1987). The data in this article support the position that direct point-of-service cost sharing reduces Medicare spending. However, the data also suggest that such a strategy would not apply to all beneficiaries. Some additional thought further suggests that expenditure reductions might be well below the magnitudes suggested in this article.

The effectiveness of a strategy of increased cost sharing depends on the share of the Medicare population that would have to pay any increased Medicare cost sharing. Using the current distribution of the Medicare population by their supplemental insurance holdings, we can estimate the likely share of the Medicare elderly who would be directly affected by an increase in cost sharing.

The 11.4 percent of the population who have only Medicare would clearly be affected by any increase in Medicare cost sharing. The 41.8 percent of persons with individually purchased insurance are largely protected from increases in cost sharing.6 Similarly, the 11.9 percent of persons with Medicaid coverage are essentially protected from paying Medicare cost sharing.

Most of the 33 percent of persons with only employer-sponsored insurance are theoretically responsible for the lower of either Medicare or their private plan deductibles and copayments. Whether the beneficiary actually pays either deductible or copayments depends on the method employers use to coordinate their benefits with Medicare (Short and Monheit, 1988). There is some evidence that many employers are not using deductibles and benefit coordination methods to increase beneficiary cost sharing (Morrisey, Jensen, and Henderlite, 1990). Further, an increase in Medicare deductibles and copayments would only apply to those persons whose employer-sponsored insurance had deductibles and co-payments that were greater than Medicare's (hypothetical) new levels.

Under the most sweeping assumption (that all beneficiaries with employer-sponsored insurance would pay new cost sharing), an increase in Medicare cost sharing would apply to about 45 percent of elderly beneficiaries. Under more realistic assumptions about private plan deductibles and methods of payment coordination, an increase in Medicare cost sharing would probably apply to about one-third of elderly beneficiaries.

There is another reason why an increase in the Medicare deductible and co-payments might not yield expected savings. Tables 7 and 8 show that the insurance groups that would be most directly affected by an increase in Medicare cost sharing, those with Medicare only and employer-sponsored insurance, already have per capita spending levels that are 20 to 30 percent below average. At the margin, since these groups already face more cost sharing than the average beneficiary, an increase in cost sharing might not have much of an additional affect in lowering their Medicare spending. It seems logical that the maximum savings from any increase in Medicare cost sharing would occur only if new Medicare cost sharing was applied to those insured groups who do not now pay deductibles and copayments.

The data in this article make clear that the Medicare program is not a closed system. The institutional network of private and public insurance that has built up around Medicare has improved access to care, but it has also operated to increase Medicare spending. Any effort to limit the growth in Medicare spending by increasing point-of-service cost sharing will not reach the majority of beneficiaries, and probably would not produce desired levels of reduction in Medicare spending, unless it also addresses supplemental insurance arrangements.

Data Sources and Methods

The supplemental health insurance data were collected in the MCBS, a continuous panel survey of about 14,500 beneficiaries, of whom over 12,000 are age 65 or over. The data in this article were prepared from a public use file that is being made available for general use. MCBS round one survey data, which was collected from September through December 1991, have been linked to Medicare administrative bill records for calendar year 1991. This links information that can only be collected in the survey (e.g. supplemental health insurance coverage) to Medicare billing records which show service use and program spending for each person in the survey. For round one, 87 percent of the initial sample were completed interviews. An initial analysis of the refusals and non-respondents does not show any obvious differences between those who participated and those who did not. Future reports and public use files for later survey rounds will include services not covered by Medicare such as prescription drugs, and will show all sources of payment for health services.

The Medicare per capita spending figures are based on persons who were always enrolled in 1991, that is, alive from January 1, 1991 to December 31, 1991. Historically, health care spending is high in the last years of a person's life. Since persons who died during 1991 are excluded from Table 2, per capita spending figures are probably lower on average than they would have been with deaths included. We have also excluded persons who are enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and other managed care arrangements from Tables 7 and 8. This was done because most of Medicare's program payments to HMOs are per capita payments that are not reflected in Medicare administrative bills. We chose to exclude HMO members entirely rather than include them with seriously understated program spending figures derived from partial Medicare bills. Finally, the spending figures only reflect Medicare program payments for Medicare-covered services. The spending figures do not reflect the out-of-pocket expenses by beneficiaries or spending by private supplemental insurers or Medicaid. Further, the spending figures do not include spending for services not covered by Medicare such as prescription drugs or long-term facility care.

To summarize, for various reasons the figures are not designed to estimate total spending per person on all health services. However, they are good approximations of Medicare spending per person for the majority of Medicare elderly persons who received their health services in the fee-for-service sector during 1991.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Robert Christy for his expert statistical programming assistance. We are also indebted to Brad Edwards, David Gibson, Katharine Levit, Carolyn Rimes, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

The authors are with the Office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration and the opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the Health Care Financing Administration's views or policy positions.

The MCBS is being directed by the Office of National Health Statistics within the Office of the Actuary in the Health Care Financing Administration. The data is being collected under contract by Westat Corporation.

By point-of-service price we refer to Medicare deductibles or copayments which the beneficiary, and not a supplementary insurer, is responsible for paying. Beneficiaries who purchase private health insurance do not avoid Medicare cost sharing. They opt for predictable advance premium payments rather than risk unpredictable out-of-pocket payments when they need care. However, once the beneficiary has insurance to cover all Medicare cost sharing, the decision to seek care usually means no additional out-of-pocket liability. In this sense they face no point-of-service cost sharing.

Disabled persons were brought into the Medicare program in 1972. This article focuses solely on Medicare persons age 65 or over.

ln addition to QMB's with incomes at or below the poverty line, a new category of persons between 100 percent and 110-percent of the poverty line will be eligible for payment of Medicare premiums only beginning in 1993. This qualifying band above the poverty line is scheduled to expand to 120 percent in 1995.

The employer-sponsored insurance category contains a small percentage of persons over 65 who are still employed and have health insurance through their employer. Their employer, not Medicare, is the primary payer for their health care use. We examined the hypothesis that below average Medicare per capita spending occurs because private insurance payments are being substituted for Medicare payments for persons still working. We recalculated all insurance category Medicare per capita spending figures excluding working aged persons. We found only a very slight effect from excluding working aged from the employer-sponsored insurance category. It increased per capita spending only 1.7 percent.

Persons whose medigap plan did not cover the SMI deductible would be affected by an increase in that cost sharing, unless they chose to upgrade their insurance in the face of new cost sharing.

NOTE: The MCBS round one public use tape and documentation is available for purchase from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161. The item number for the data tape plus documentation is PB93-50062. Documentation alone is item number PB93-100287. General questions about the survey should be addressed to Frank J. Eppig, Project Director, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Office of National Health Statistics, Office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration, Room L-1, EQ05, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

Reprint request: George Chulis, Ph.D., Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary, EQ05, L1, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

References

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. The 1992 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1992. House of Representatives Document 102-280. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Supplementary Medical Insurance Fund. The 1992 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1992. House of Representatives Document 102-281. [Google Scholar]

- Cafferata GL. Private Health Insurance Coverage of the Medicare Population. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sep, 1984. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 84-3362. National Health Care Expenditures Study Data Preview 18. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MS, Arnett RH., III Private Health Insurance Plans in 1978 and 1979: A Review of Coverage, Enrollment, and Financial Experience. Health Care Financing Review. 1981 Fall;3(1):55–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chollet DJ. Retiree Health Benefits: What is the Promise? Employee Benefits Research Corporation; Washington, DC.: 1989. Retiree Health Insurance Benefits: Trends and Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S, Long SH, Rodgers J. Acute Health Care Costs for the Aged Medicare Population: Overview and Options. Milbank Quarterly. 1987;65(3):397–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, Kreps JM. Employer-Provided Health Care Plans for Retirees. Research on Aging. 1989;11(2):206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bene L, Vaughan DR. Income, Assets, and Health Insurance: Economic Resources for Meeting Acute Health Care Needs of the Aged. Social Security Bulletin. 1992 Spring;55(1):3–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop BD, Wells JA, Wilensky GR. The Influence of Source of Insurance Coverage on the Health Care Utilization Patterns of the Elderly. Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration. 1989;11(3):285–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel SA, Corder LS. National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug, 1985. Supplemental Health Insurance Coverage Among Aged Medicare Beneficiaries. (B). Descriptive Report No. 5. DHHS Pub. No. 85-20205. National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. The Medicare Handbook, 1991. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1991. HCFA Pub. No. 10050. Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl S. Health Perceptions and Survival: Do Global Evaluations of Health Status Really Predict Mortality? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1991;46(2):S55–65. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.2.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz DC, Monheit AC. Health Insurance, Use of Health Services, and Health Care Expenditures. National Medicare Expenditure Survey Research Findings 12. Public Health Service; Dec, 1991. AHCPR Pub. No. 92-0017. [Google Scholar]

- Link CR, Long SH, Settle RF. Cost Sharing, Supplementary Insurance, and Health Services Utilization Among the Elderly. Health Care Financing Review. 1980 Fall;2(2):25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SH, Settle RF, Link CR. Who Bears the Burden of Medicare Cost Sharing? Inquiry. 1982 Fall;19(3):222–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan A, Pine PL, Gornick M, Prihoda R. A Study of the “Crossover Population”: Aged Persons Entitled to Both Medicare and Medicaid. Health Care Financing Review. 1983 Summer;4(4):19–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan A, Gornick M. The Dually Entitled Elderly Medicare and Medicaid Population Living in the Community. Health Care Financing Review. 1984 Winter;6(2):73–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monheit A, Schur C. Health Insurance Coverage of Retired Persons. National Medical Expenditure Research Findings Number 2. National Center for Health Services Research and Technology Assessment; 1989. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 89-3444. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey MA, Jensen GA, Henderlite SE. Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance for Retired Americans. Health Affairs. 1990 Spring;9(1):57–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T, Desmond K, Gabel J. Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act: A Post Mortem. Health Affairs. 1990 Fall;9(3):75–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.3.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T, McCall N. The Extent of Ownership and the Characteristics of Medicare Supplemental Policies. Inquiry. 1985 Summer;22(2):188–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler RM. An Analysis of Medigap Enrollment: Assessment of Current Status and Policy Initiatives. In: Pauly MV, Kissick WL, editors. Lessons From the First Twenty Years of Medicare. Philadelphia, PA.: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Short PF, Monheit AC. Employers and Medicare as Partners in Financing Health Care for the Elderly. In: Pauly MV, Kissick WL, editors. Lessons From the First Twenty Years of Medicare. Philadelphia, PA.: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stern L. Time to Feed the FASB. Business and Health. 1991 Jul;9(7):35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AK, Short PF, Horgan CM. Medigap Insurance: Friend or Foe in Reducing Deficits? In: Frech HE III, editor. Health Care in America. San Francisco, CA.: Pacific Institute for Public Policy; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congressional Budget Office. Restructuring Health Insurance for Medicare Enrollees. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congressional Budget Office. Economic Implications of Rising Health Care Costs. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Oct, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo DR, Sonnefeld ST, McKusick DR, Arnett RH., III Health Expenditures by Age Group, 1977 and 1987. Health Care Financing Review. 1989 Summer;10(4):111–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]