Introduction

In this article, we review five health care cost-containment efforts from 1971 to the present and summarize key research findings on the effects of each on cost, quality, and access. These efforts include the Nixon Economic Stabilization Program (ESP), Carter-era hospital cost-containment efforts, Medicare hospital and physician payment, and State hospital ratesetting programs. The purpose of these efforts was to constrain the growth of health care spending by regulating or controlling prices or payments to providers of health care. Based on the experience of all five programs, we conclude with an analysis about the effectiveness of these kinds of initiatives.

This synthesis responds to the interest on the part of policymakers to better understand how current cost-control efforts can benefit from those of the past at both the Federal and State levels. In research spanning two decades, considerable knowledge has accumulated, though many outstanding questions remain. In general, this research shows that price controls can be effective but also that their effectiveness is constrained by provider responses to the incentives the controls create. Not surprisingly, research suggests that the most effective approaches also tend to have the broadest scopes: all-payer versus individual-payer systems, aggregate payment controls versus per service controls, and total payment limits (which address the base) versus only rate-of-increase limits. This greater effectiveness occurs because the more aggregate or all-encompassing approaches limit the ability of providers to offset cost pressures by raising prices to other payers or by increasing volume of care. Whether or not such controls merit serious consideration today and how they compare or may be combined with other strategies for cost containment are questions that exceed the scope of this article. The sources for this article, annotated and organized within each of the five cost-containment efforts, are listed in the Appendix.

Economic Stabilization Program

Summary of Program

Impetus and Context

ESP was a broad-based system of wage and price controls designed to deal with inflation that was perceived to stem from increases in wages and other input costs (“cost-push inflation”). There was special concern for the health care sector (particularly hospitals), in which prices and expenditures were rising considerably faster than those in the economy overall. Although partly fueled by wage increases, health care cost inflation also reflected changes in technology and demand, particularly with the growth of private health insurance and the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid. However, hospital cost inflation had already started to decline as ESP was introduced, thus complicating the evaluation of the ESP effects (Ginsburg, 1977; Altman and Eichenholz, 1977).

Basic Features and Timing

ESP was introduced in several phases.

Phase I (August 15-November 13, 1971)

This phase involved a 90-day freeze on all wages and prices. Although unannounced, the freeze was authorized by standby legislation enacted in the preceding year. The freeze was intended to gain time to develop more substantial policies (Weber, 1973). The hospital freeze applied only to charges, leaving hospitals free to increase rates on the large share of cost-based payments. The freeze was expected to be short, and the future base period for ongoing controls was uncertain. Ginsburg (1977) argues that hospitals were unlikely to take advantage of the loophole to raise cost-based rates.

Phase II/Termination (November 14, 1971-April 30, 1974)

Wage and price controls were introduced during this time. Wage increases were limited to 5.5 percent; price control targets, intended to cut inflation in half, were set for each economic sector. Price increases were allowed only if they could be cost justified, adjusted for productivity gains, and subject to profit-margin limits. Price controls were added largely for equity to assure workers that windfall profits did not result from wage controls, which were perceived as the more important control (Ginsburg, 1977). Although general economic controls strongly influenced the design of health sector controls, the experience of ESP clearly shows a need for controls that are tailored from the start to the health sector. For instance, incongruities between the health and general manufacturing and/or service sectors, particularly in the institutional sector, created a need to continually refine controls and to introduce an exceptions process—both of which may have influenced the effectiveness of the controls. Within the health sector, controls varied for institutional and non-institutional providers, and the distinction between Phase II and Phase III controls was less relevant than for other sectors.

Institutional health care providers were limited to a 6-percent increase in aggregate revenue from price increases, subject to cost justification. Within this 6 percent were limits of 5.5 percent for wages, 2.5 percent for non-labor costs, and 1.7 percent for new technology and services (Davis et al., 1990). In the case of hospitals, although services were the intended unit of control, it was not clear until September 1973, when hospital-specific regulations were issued, how this applied to cost-based payers. These regulations also introduced an exceptions process (through State advisory boards), which included exceptions for hospitals with negative cash flow, and a volume index. The index adjusted a hospital's level of allowable costs and revenues for changes in the numbers of days of care or admissions; the index generally assumed that all or most costs were variable rather than fixed (Altman and Eichenholz, 1977; Abernethy and Pearson, 1979). Although limited, the volume index generated controls more stringent than those in the rest of the economy, and despite confusion, created some incentives to reduce intensity of care (Ginsburg, 1977).

Non-institutional health care providers were allowed aggregate weighted average price increases of 2.5 percent if they were justified by cost increases (Altman and Eichenholz, 1977). Voluntary compliance was assumed, with enforcement limited to cases in which patients complained of increases that exceeded the limits (Hadley, Holahan, and Scanlon, 1979).

Phase IV

In the health sector, Phase IV would have shifted controls from per service and per diem limits toward more aggregate controls on admissions or stays. This action was never implemented for the health sector, however, because the ESP controls (authorized by Executive order) expired and required legislation was not enacted. Proposed Phase IV legislation for the health sector was vigorously opposed by the hospital industry.

Characteristics of Controls

A number of characteristics defined the ESP controls and had the potential to influence their effectiveness. It is useful to keep these characteristics in mind when comparing the ESP experience with that of other cost-containment efforts in this article. The characteristics of the ESP controls include (1) constraints on rate of increase rather than base expenditures, (2) unit of control based on service or day rather than more aggregate measures, (3) short duration, (4) wage emphasis, with limited attention to price enforcement, particularly in the non-institutional sector, and (5) limitations and delays in adapting controls to fit unique aspects of the health sector, particularly for institutions. In addition, Ginsburg (1978) notes that making exceptions for hospitals with a negative cash flow causes distortions in the market.

Effects on the Hospital Sector

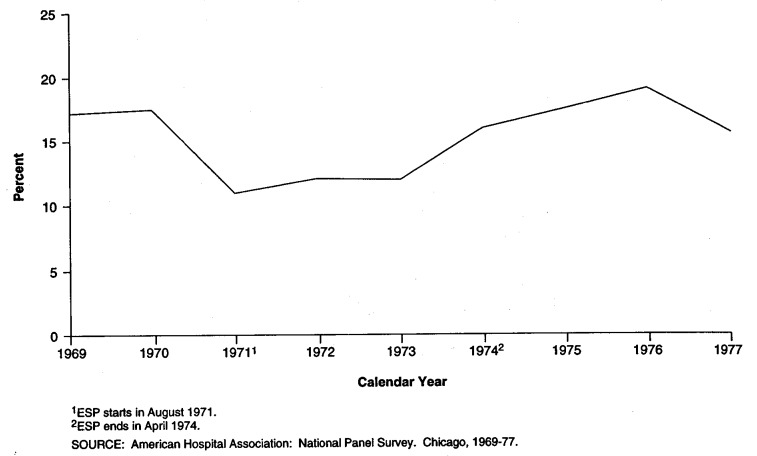

The research on the effects of ESP on the hospital sector appears to show that the program moderated hospital cost inflation, having greater effects on per unit than on aggregate spending. Restraints on revenue do not appear to have contributed to reductions in expenses other than for wages; hence, profits declined. Once controls were lifted, inflation appears to have returned to its precontrol levels—at least from the descriptive evidence. It is not clear whether this totally eroded all gains from controls. There is little research on effects on access and quality, perhaps because few effects were expected. The research is summarized in the rest of this section. Figure 1 shows the trend in growth of hospital expenses from 1969 through 1977; it shows a decline after ESP was introduced and acceleration once it ended.

Figure 1. Trends in Annual increases in Total Hospital Expenses Before, During, and After the Economic Stabilization Program (ESP): 1969-77.

Effects on Prices and Expenditures

Steinwald and Sloan (1981) conclude that ESP moderated hospital cost inflation, though they are cautious about extending the ESP research to similar longstanding programs. They base their conclusion on:

Descriptive studies of ESP showing a reduction of several percentage points in hospital cost increases (Altman and Eichenholz, 1977; Steinwald and Sloan, 1981). Altman and Eichenholz show larger effects on room and board (50 percent) than on cost per adjusted day or adjusted admission (25 percent).

Multivariate analyses showing mixed results. Ginsburg (1978) shows a small but not significant negative effect on prices and no effect on expenditures. Steinwald and Sloan (1981) show a small but significant (less than 1 percent) effect on measures of expense per admission and per day. Sloan (1981) shows larger effects—in the range of 2-3 percent.

American Hospital Association (AHA) research (Raske, 1973) suggests that reductions resulting from ESP were greater for the hospital sector than for the overall economy based on trends in the hospital service charge component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the overall CPI.

Effects on Costs

Ginsburg (1978) finds that ESP was very effective in reducing hospital employee wages, but not costs in general. AHA research concurs that a minority of institutions (less than 30 percent) reported difficulty in complying with wage controls, but 95 percent reported difficulty in complying with non-wage limits (Raske, 1973).

Effects on Hospital Profits

ESP reduced hospital profits (Sloan, 1971). The 6-percent reduction in profit margin was almost significant at the 10-percent level (Ginsburg, 1978). Raske (1973) shows a decline in operating margins during Phase II. The declines of 21-42 percent in this descriptive study differ from Ginsburg's results that show very small changes in magnitude.

Experience After Controls Were Lifted

In a descriptive study, the Council on Wage and Price Stability (1976) shows that the CPI (hospital service charges) rose from 4.6 percent when controls were in effect to 14.6 percent immediately after controls were lifted, and to 13 percent in 1975 (pre-control data are not available, but data on semi private room charges show that they dropped during ESP). In econometric research not restricted to the health sector, Blinder and Newton (1981) show ESP lowering non-food, non-energy prices by 3-4 percent, followed by a period of rapid inflation after controls were lifted. As they note, this left the price level 0-2 percent below what it would have been in the absence of controls.

Effects on Access and Quality

There are no formal studies on the effects of ESP on access or on outcome or process of care. Ginsburg (1978) shows a decline in the ratio of labor to non-labor inputs, no change in inputs per day, and a decline in inputs per admission. This implies a reduction in length of stay, though results are sensitive to the form of model specification. Lave (1977) states that ESP forced hospitals to defer the introduction of many new services, but it is not clear that this is an empirically derived statement.

Effects on the Physician Sector

Research on ESP's effect on the physician sector is more limited than that on the hospital sector, perhaps because controls were less complex or demanding on physicians. Research appears to show that ESP constrained growth in physician fees, but because physicians provided more services and more complex services, total spending and growth in physician income may not have been reduced. In general, research shows that although physicians are able to offset fee controls by increasing volume or intensity of services, the extent to which they are offset continues to be debated.

ESP Research

Researchers at The Urban Institute performed a major study of ESP effects on physician controls in an investigation of the effects of ESP on Medicare physician payments in California. Holahan et al. (1979) show that controls limited unit prices, but service mix became more complex and volume increased. As a result, Medicare physician income increased more under controls than in the next year. These results were confirmed by additional econometric analysis (Hadley, Holahan, and Scanlon, 1979). Once controls were lifted, unit prices increased and volume dropped. The researchers raise the possibility that results could reflect in part the substitution of Medicare patients for private patients during price controls because cost sharing was more limited under Medicare, and hence, demand was easier to induce. They also note that long-term effects could differ from short-term effects because more costs are variable in the long run.

Descriptive Studies

The Council on Wage and Price Stability (1976) shows that the physician services component of the CPI-Medical Index increased 4 percent under controls, 12.8 percent immediately after, and 11.8 percent in 1975; inflation in the precontrol period was 6.9 percent. Theodore and Warner (1977) find that physician fees were more responsive than other economic sectors to ESP and that they rose rapidly after controls were lifted.

Related Research on the Fee Freeze

In response to rapid inflation in Medicare physician spending, Congress froze Medicare fees in 1984. Originally scheduled to last 15 months (beginning July 1, 1984), the freeze was extended until May 1986 for participating physicians and through the end of 1986 for non-participants. In research complicated by the absence of a control group and by the simultaneous introduction of the prospective payment system (PPS) and other changes, Mitchell, Wedig, and Cromwell (1989) found rapid increases in spending despite the freeze. In particular, expenditure increases far exceeded volume increases, with the procedure code mix shifting to more complex and highly paid services. This change probably reflected both “upcoding” and real case mix changes resulting from the enactment of PPS. The major spending increases were for surgery and diagnostic tests.

Other Studies

Based on a review of studies, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO)(1991) concludes that there is a pronounced volume offset that substantially reduces anticipated savings from fee freezes or controls on physicians. Hadley, Holahan, and Scanlon (1979) cite evidence from Canada suggesting that there are limits to creating demand. Starr (1982) emphasizes the ESP research in that study in drawing the same conclusion. This issue, also analyzed in the context of recent Medicare physician payment reform, is fully discussed later in this article.

Findings Relevant to Implementation

Dunlop's Observations

Dunlop and Fedor (1977) note that it is easier to start controls than to end them. Postcontrol bulges in prices and wages may undo or counteract control-period reductions. Using a single standard (e.g., for wages) to establish controls across sectors of the economy may exaggerate distortions in the relationships among occupations, industries, and localities.

Weber's Observations

Weber (1973) suggests that the public's tolerance for a short-term freeze (Phase I) was greater than expected but that the freeze led to early distortions in Phase II. He suggests that Phase II should have been more discriminating, and its enforcement more flexible. Appropriately tailoring controls from the start would have diminished the need for exceptions. He concludes that wages are easier to control than prices, which are more varied and complex, continually changing, and less visible. Also, incentives to hold down wages differ from those to hold down prices. He also concludes that (1) little or no warning about the freeze increased its effectiveness, (2) adequate planning is needed for implementation (this did not occur in 1971), (3) implementation is possible with a reasonably small staff, and (4) ignoring procedural guidelines and due process can lead to problems. However, we note that the desire to avoid warning could inherently conflict with the need for planning.

Lave's Observations

Lave (1977) agrees that wages are easier to control than prices, a disparity that can lead to equity problems that destroy the system. Because Phase I regulations were easier to enforce in large institutions, he concludes that regulations would be more effective for hospitals than physicians.

Carter-Era Hospital Cost Containment

Summary of Program

Impetus and Context

Carter-era hospital cost containment involved a series of efforts to enact legislation restraining the growth of hospital costs on an all-payer basis nationwide. These efforts were spurred by rapid increases in hospital spending that were perceived as a threat to presidential objectives designed to balance the Federal budget and to enact a national health plan (Davis et al., 1990). From 1975 through 1977, expenses for community hospitals increased at an annual rate that was 8.7 percent higher than the overall rate of inflation. In public opinion polls, rising health care costs were among the top three domestic concerns of Americans (Abernethy and Pearson, 1979). Proposals for control drew upon the growth of research on hospital economics and the experience of ESP. However, support for regulation was also starting to erode in the 1970s, which contributed to the unsuccessful legislative outcome of the cost-containment proposals (Abemethy and Pearson, 1979).

Basic Features and Timing

Legislation to enact hospital cost containment was introduced twice in Congress; efforts to enact this legislation led the hospital industry and others to mount a “voluntary effort” (VE) to control costs without the need for legislation.

Hospital Cost Containment Act of 1977

House Resolution (H.R.) 6575, introduced April 25, 1977, by Representatives Rogers and Rostenkowski, was presented as an interim measure while a longer term prospective payment system was being developed (Davis et al., 1990). Faced with vigorous opposition from the hospital industry (discussed later), the 95th Congress actively considered the bill. The Senate passed a substantially amended version of a related bill introduced by Senator Talmage emphasizing standby mandatory control, but the session expired without the enactment of legislation. H.R. 6575 would have established a growth ceiling on hospital operating revenues from inpatients in short-stay hospitals based on overall inflation (defined by the gross national product deflator) and a formula-derived intensity factor. This limit would be volume adjusted on the basis of factors assuming a mixture of fixed and variable costs; wage pass-throughs were alllowed for non-supervisory personnel; and a review process was established for hospitals experiencing major volume or intensity changes. In 1978, the formula would have meant an 8.73-percent growth (5.52-percent gross national product deflator and 3.21-percent intensity factor), increased to 10.6 percent with adjustments (Dunn and Lefkowitz, 1978). The limit, which would have applied to all payers, would be enforced through separate limits on each cost-based payer (Medicare, Medicaid, Blue Cross) and on charge payers. States with mandatory all-payer ratesetting programs were exempted, as were hospitals under 2 years old and those that received more than 75 percent of their revenue from health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The bill also included a national limit on new capital expenditures, which would initially be allocated among the States on the basis of population. Bed and occupancy standards were also established (Dunn and Lefkowitz, 1978).

Industry Reaction and VE

In vigorously opposing H.R. 6575, the hospital industry argued that legislation was unnecessary because they could vol-untarily contain costs. VE was announced in December 1977 by AHA, the Federation of American Hospitals, and the American Medical Association (AMA). The National Steering Committee for VE also later included the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, the Health Industries Manufacturing Association, the Health Insurance Association of America, the National Association of Counties, a consumer consultant, and representatives of business and labor (Appelbaum, 1979).

The steering committee for VE established a 15-point program, with the goal of generating a 2-percentage-point reduction in aggregate operating expenses for all U.S. hospitals for calendar years 1978 and 1979. Based on the historical rate of increase in 1977 at 15.6 percent, this meant that 13.6 percent would be the target increase in 1978 and 11.6 percent the target in 1979 (Schaeffer, 1979). The VE campaign was administered by State-level committees similar in composition to the National Steering Committee. Activities varied among States from information clearinghouse functions and technical assistance to budget review and hospital screening; some States established numerical targets (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1979; Appelbaum, 1979; Abernethy and Pearson, 1979; Schaeffer, 1979). Although goals of the effort also covered bed and capital targets, the emphasis was on reducing the overall rate of increase in expenditures.

Hospital Cost Containment Act of 1979

The Carter administration reintroduced legislation in the 96th Congress. H.R. 2626, introduced March 6, 1979, responded to some concerns raised by the hospital industry and Congress in response to the 1977 bill (Davis et al., 1990). The bill had a “sunset clause” of 5 years, with a commission established to develop a permanent PPS. Despite the modifications, the hospital industry continued to oppose the bill, citing both its complexity and the success of VE in slowing cost growth (Davis et al., 1990). The legislation was defeated in the House in November 1979, thus terminating efforts to obtain all-payer hospital cost controls.

H.R. 2626 proposed that controls on hospital revenues be triggered if hospitals did not meet guidelines for total expenditure increases. The bill established guidelines on the basis of inflation (as measured by the hospital market basket index—not, as previously, by the gross national product deflator), population growth (set at 0.8 percent), and intensity of care, with a 1-percent allowance for growth. CBO (1979) calculated that the formula would allow hospitals a 12.9-percent increase in 1979, lower than the 13.8-percent rate in the absence of controls. A hierarchical series of performance tests based on national, State, and individual hospital guidelines would determine which hospitals were to be subject to controls. States with mandatory ratesetting programs would be exempt as long as hospital expenses in the State were not more than 1 percent above the State guidelines. In its revenue controls, the bill excluded long-stay hospitals, continued the exemption for hospitals largely serving HMO patients, expanded the exemption for new hospitals from under 2 to under 3 years old, and exempted non-metropolitan hospitals with fewer than 4,000 admissions per year (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1979).

Although the guidelines were based on total revenue, the controls applied only to inpatient revenue. For hospitals defined as being subject to controls, revenue caps for inpatient admissions would be calculated for each payer on a calendar-year basis using the hospital market basket and the individual hospital's wage increase for non-supervisory personnel. The cap would then be adjusted to encourage efficiency based on peer group comparisons to counter incentives to increase admissions (using a mechanism to be established through regulations) and to avoid introducing incentives to increase costs in the year before controls. Hospitals could carry over unused portions of revenue below the cap to future years. An exceptions process was included but not specified (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1979).

Effects on Cost, Access, and Quality

Although analysts estimated that considerable savings would accrue from both the 1977 and 1979 versions of all-payer hospital cost-containment legislation (Dunn and Lefkowitz, 1978; Davis et al., 1990; U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1979), the legislation was never enacted. Hence, these estimates cannot be empirically validated. Research can only show the combined effect of the threat of cost-containment legislation and VE.

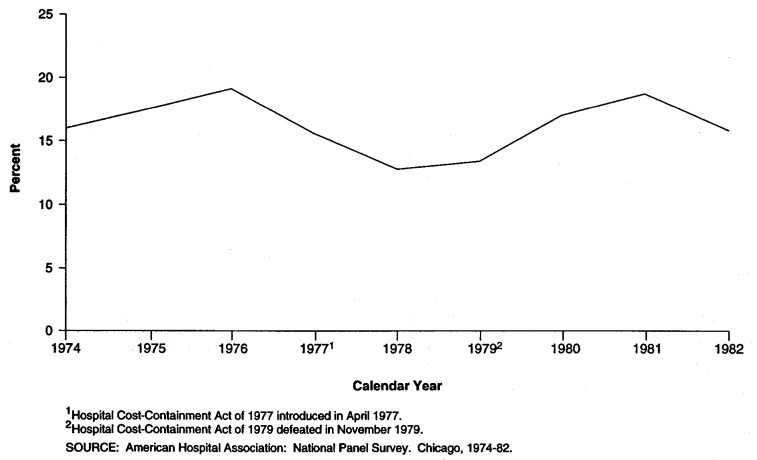

This research appears to show that VE was somewhat successful while the threat of cost containment loomed. However, once legislation was defeated, costs rose and VE collapsed. There is not enough research to assess whether this pattern of cost control was in itself sufficient to slow the growth of spending in the long run. There are no empirical studies on the effects of cost containment on access or quality, perhaps because few effects were expected. Figure 2 shows the trend in growth of hospital expenses from 1974 through 1982; it shows a decline while hospital cost-containment legislation was being considered and acceleration once it was defeated.

Figure 2. Trends in Annual Increases in Total Hospital Expenses Before, During, and After the Voluntary Effort, in Response to Carter Hospital Cost-Containment Legislation: 1974-82.

Research on VE

While cautioning policymakers about the limits of its study, CBO (1979) found that in 1978, hospital expenditures increased 12.8 percent, or 1.1 percent less than what the probable rate would have been in the absence of VE. This generated a savings of $0.6 billion. CBO also estimated that in 1979, the rate of increase was 14.5 percent under VE, compared with 15.6 percent without VE. This generated a savings of $1.3 billion. The VE goal was 13.6 percent in 1978 and 11.6 percent in 1979. CBO analysis indicates that the industry would have met its VE goal in 1978 but was unlikely to do so in 1979. CBO attributed the failure to meet the 1979 goal to a combination of VE's limited power and an upswing in general inflation from the time the VE goals were set. CBO also noted that its econometric model, although superior to other approaches, is limited in the ability to isolate effects of VE from effects caused by the threat of controls. CBO research is also limited by the short time period in which VE was in effect; estimates of effects were not significant at conventional levels. CBO also noted that VE did not alter incentives to increase costs, and it predicted that voluntary efforts would probably slack off if legislation were not enacted.

In an econometric study of the effectiveness of alternative cost-containment measures from 1963 through 1978, Sloan (1981) examines the effects of VE in 1978. He finds that VE had a statistically significant negative effect on cost per admission and cost per day of 3-5 percent, and a positive effect on profits (total hospital revenues minus expenses). To evaluate these results jointly is a complex task, however, because costs are measured on a per unit basis and profits are measured in the aggregate. Hence, it is not clear from this research whether the hospitals (1) constrained costs but not revenue during VE, (2) constrained unit costs but increased volume, or (3) achieved some mixture of the two. Steinwald and Sloan (1981) conclude that there was a certain amount of cynicism about self-regulation. They argue that cost savings were not passed on to consumers and that incentives are likely to depend on the threat of more stringent government controls.

Descriptive Evidence on Hospital Expenditures

The real rate of increase in hospital expenditures (expenditures deflated by the CPI) fell from 9.5 percent in 1976 to 1.7 percent in 1979 at the height of debate on the cost-containment legislation. The rate rose to 2.6 percent in 1980 (Davis et al., 1990). (The underlying CPI, used to deflate hospital spending, was rising over this period.)

Medicare Hospital Prospective Payment System

Summary of Program

Impetus and Context

Established in 1983, Medicare PPS continued the movement away from retrospective, cost-based reimbursement for hospitals with the objective of controlling the rapid rise in hospital expenditures. PPS was enacted in a climate of concern over growth in Medicare spending and its impact on the Medicare trust fund (Iglehart, 1983; Altman and Young, 1993). Earlier efforts to limit total operating costs (established by the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 [TEFRA]) supported the development of technology essential to PPS. New Jersey's all-payer ratesetting experience with payment by diagnosis-related group (DRG) was a useful precedent in demonstrating that PPS was feasible.

PPS was enacted unusually rapidly and with bipartisan support; yet, it was also anticipated by Congress's directive during the previous year in TEFRA that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) develop a Medicare PPS. The Reagan administration, although opposed to regulation, viewed PPS as the response of a prudent purchaser concerned with creating incentives for efficiency and reducing the deficit. Congressional support for PPS was enhanced because the hospital lobby was divided, with some major groups viewing the PPS incentive structure as more appealing than the current limits. The hospital industry had also lost some bargaining credibility because of its inability to control costs through VE (Moon, 1993; Iglehart, 1982 and 1983).

Basic Features and Timing

Medicare PPS provides an annually updated prospective case-based payment for each type of hospital discharge, as defined through DRGs. PPS covers inpatient care in acute care hospitals. Certain specialized hospitals or distinct part units, and outpatient services are excluded. Although the basic PPS structure was established in 1983 and the transition to PPS was completed in fiscal year 1988 (FY88), it has been refined over time. Also, Congress has made changes to address issues of perceived equity, particularly for teaching, disproportionate-share, and rural hospitals. These changes have generally been budget-neutral and have led to the redistribution of payments among the different types of hospitals, thus influencing who won and who lost under PPS.

PPS payments are calculated from a base standardized amount or national average cost, with DRG weights used to reflect the relative costliness of each DRG grouping. Hospitals are paid a fixed amount nationwide per DRG, subject to an area wage adjustment and hospital-specific adjustments for indirect medical education costs and disproportionate-share status. Separate rates apply to hospitals located in large urban, other urban, and rural areas, but the distinction between rural and other urban areas will be phased out by 1995. Additional payments are made for outlier cases defined by days or, increasingly, by cost. Historically, capital, direct medical education, and malpractice costs were paid on a passthrough basis. Starting in FY92, capital costs were also paid prospectively, subject to a 10-year phasein. Direct medical education expenditures have been paid on a formula basis since FY91 (U.S. Congress, 1992; Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1992a,b).

Characteristics of PPS

Three features are important in understanding the effects of PPS. The first feature is that PPS employs case-based rates that generate financial risk for institutions for operating losses, along with the ability to retain any savings from enhanced efficiency and reduced intensity. The second feature is that PPS involves a movement to national rates that creates greater financial stringency for higher cost hospitals after PPS adjustments. The third feature is that the PPS design inherently creates incentives to encourage an increase in admissions; however, these incentives apply only to hospitals rather than the physicians who determine such hospitalizations. In the early years, which are those most extensively researched, effects may also have been influenced by hospitals' reactions to first-year PPS payments, which were higher than anticipated. These payments created windfall increases in margins as expenses per case dropped largely because length of stay declined (Coulam and Gaumer, 1992). (Overpayments resulted from limitations in the data and assumptions used to set rates and from a growth in reported case mix.) Because PPS is specific to Medicare, it creates the potential to shift costs to other payers, which would reduce the impact on total hospital expenditures (Altman and Young, 1993).

Effects on Costs

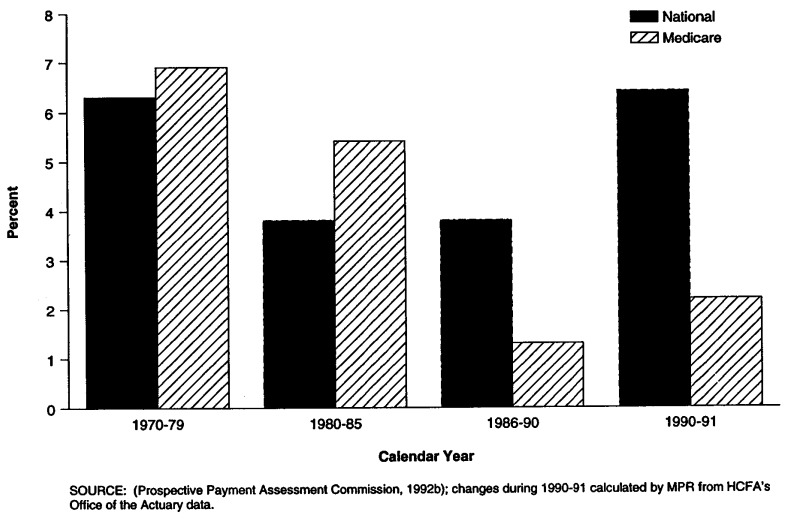

Coulam and Gaumer (1992) have reviewed the literature on the effects of PPS on costs. Overall, these results appear to show that PPS restrained the growth of Medicare spending without seriously affecting access or quality of care. Because PPS has been less effective, particularly more recently, in restraining growth in hospital expenses, Medicare PPS margins declined. There is some disagreement about the extent to which PPS has raised costs to other payers through cost shifting, which would weaken its effects on total health spending. Overall hospital profit margins peaked in the mid-1980s and have not declined from pre-PPS era levels. Figure 3 shows the trend in real growth in national and Medicare hospital expenditures per capita during the 1970-91 period. The figure shows that, although Medicare hospital expenditures were growing faster than the Nation's as a whole through the mid-1980s, this trend reversed as PPS was implemented. From that period, the increase in Medicare expenditures slowed considerably, to a rate less than that of the Nation as a whole.

Figure 3. Annual Percent Change in Real National and Medicare Hospital per Capita Expenditures: 1970-91.

Because of the volume of research, we rely heavily on the Coulam and Gaumer article, limiting our citations of other studies. We assume readers will refer to the Appendix to identify particular sources for areas of research.

Medicare Expenditures

Research generally shows that Medicare Part A expenditures grew more slowly after PPS was introduced. Only part of this slowed growth is related to an unexpected and unexplained initial decline in admissions, which later stabilized. Russell and Manning (1989) project that PPS reduced the historical growth in Medicare Part A expenditures by 20 percent between 1983 and 1990, one-third of which is attributable to declining admissions. Part B spending grew in response to PPS (though mostly for other reasons), but these increases only offset a small share of Part A savings.

Assessing the PPS effects on use and expenditures for other services is complicated because of other ongoing trends, such as the growth of outpatient services and the response to changes in guidelines for skilled nursing facilities and home health services. PPS has generally been associated with an increased use of postacute services, but the effect of PPS on skilled nursing facility use is less certain than its effect on home health. There has also been some increase in admissions to PPS exempt units. Outpatient services increased under PPS, but improvements in outpatient procedure technology, along with PPS, were largely responsible for these changes (Coulam and Gaumer, 1992).

Medicare Hospital Expenses

PPS initially led to a large reduction in the rate of increase in Medicare hospital expenses per admission as well as in the aggregate (Feder, Hadley, and Zuckerman, 1987; Hadley, Zuckerman, and Feder, 1989). Cost savings per admission largely, though not exclusively, reflected reductions in length of stay. From 1982 to 1986, cost inflation rates were 16.1 percent lower for hospitals with larger percentages of Medicare patients under PPS than for those with small percentages of Medicare patients (Robinson and Luft, 1988). It is possible that cost inflation has returned to historical levels. However, studies of growth in cost per admission are potentially confounded by the growth in case mix over the period; from the beginning of PPS through FY88, case mix accounted for a 20-percent increase in payments (Steinwald and Dummit, 1989). The increase in the case-mix index represents a combination of real changes and changes in coding practices (Carter, Newhouse, and Relies, 1990).

Medicare PPS Margins

As a result of PPS effects on revenue and expenses, Medicare PPS margins, which increased initially when PPS was introduced, have declined, and on average, are now negative, reaching −8.3 percent in the ninth year of PPS. Interpreting margins is complicated both by the need to apportion costs among payers and by the inability of the statistic to distinguish efficient from inefficient expenses. Therefore, whether expenses are too high or payments too low is debatable.

PPS produced winners and losers among hospitals. In the early years of PPS, large urban hospitals (especially those with teaching programs) had generally high PPS margins, while small rural hospitals had relatively low margins. More recently, a series of policy changes have been enacted by Congress to address perceived inequities in payment for rural hospitals (Altman and Young, 1993). Underlying the recent decline in aggregate hospital PPS margins is a widening of the gap between individual winners and losers—losers' margins have declined while winners' margins have remained steady (Prospective Payment Assessment Commission, 1991). Research suggests that potential losers were more responsive to PPS incentives, with most cost savings generated by high-cost hospitals that reduced their “slack” over time (Hadley, Zuckerman, and Feder, 1989). Coulam and Gaumer (1991) cite these results and other studies that provide evidence that PPS could be more effective if it equalized pressure rather than rates among hospitals, which implies a need for hospital-specific rates. It may be difficult to implement this feature at the Federal level, but it corresponds to some State all-payer ratesetting systems. Some argue that PPS savings reflect more the effects of administered pricing based on budget constraints than hospitals' responses to incentives for efficiency that are theoretically included in the system.

Total Hospital Expenditures and Operating Margins

Although research suggests that there are some savings overall in hospital spending as a result of PPS, it is inconclusive as to the extent to which these savings are offset by increased expenditures for other payers. In their literature review, Coulam and Gaumer (1991) conclude that the most rigorous studies show that price differences among payers are not necessarily evidence of cost shifting, but could be evidence of profit-maximizing price discrimination through the monopoly power of some hospitals. However, the Prospective Payment Assessment Commission (ProPAC)(1992) finds that total margins, after an initial decline, have been increasing under more recent PPS experience. Altman and Young (1993) conclude that this pattern reflects a cost shift, which diminishes the long-term effectiveness of Medicare PPS in constraining hospital costs.

Effects on Access and Quality

Research suggests that PPS created no serious problems of access. There is little evidence that hospitalizations are arbitrarily denied. Some hospitals have closed while PPS has been in place, but PPS has not been found to be a major factor affecting closures (Lillie-Blanton et al., 1992). Beneficiary out-of-pocket expenses under PPS have represented a constant share of total Medicare spending before and after PPS (Russell, 1989).

Most studies find no changes in quality or rates of readmission associated with PPS (DesHarnais et al., 1987 and DesHamais, Chesney, and Fleming, 1988; Kahn et al., 1990). There is neither a documented rise in mortality rates after PPS nor a significant change in readmissions or transfers. One major study finds Medicare patients to be more unstable at discharge since the implementation of PPS (Kosecoff et al., 1990), but researchers differ in their views on whether this pattern reflects a quality problem. Post-acute care use increased after PPS was implemented. PPS does not appear to have caused a large and systematic reduction in the rate at which new technology is adopted. Fewer studies exist for the more recent period in which more stringent financial constraints have been generated by PPS.

Implementation of Controls

Despite the complexity of PPS, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was able to implement the system within the desired timeframe. However, because assumptions used to set initial rates were developed on the basis of limited data and knowledge, payments in the first year of PPS were higher than anticipated. This situation can be interpreted as either an inevitable cost of startup or change or as a shortcoming that influenced the effectiveness of PPS at least in the short to mid-term. The fact that Congress modified PPS in order to deal with issues of perceived equity and payment among different types of hospitals may shed light on the political implementation of administered pricing. PPS provided a technology that other payers have adopted; the fully developed Medicare DRG system was modified in order to extend it to the non-elderly population. ProPAC (1992) recently assessed the potential effects of extending PPS to other payers and concluded that it probably would lower total insurance costs and contribute to some redistribution of revenue across types of hospitals, payers, and patients.

Medicare Physician Payment Reforms

Summary of Program

Impetus and Context

The most recent physician payment reforms under Medicare are the Medicare physician fee schedule (MFS) based on a resource-based relative value schedule (RBRVS) and balance-billing limits, and volume performance standards (VPS). Payment reforms were developed in response to rapid growth in Medicare Part B spending in the mid-1980s. Policymakers and others were also becoming more concerned that payment levels for services were becoming increasingly unrelated to the costs or medical value of the services (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 1986; Iglehart, 1990). With PPS implementation under way and perceived to be effective, Congress was encouraged to turn its attention to physician payment.

To facilitate reforms, Congress created the Physician Payment Review Commission (PPRC) to facilitate technical review of options and to develop consensus. Both technical work at Harvard University by Professor William Hsiao and colleagues and the existing Medicare experience with a fee freeze and reduced payments for overvalued procedures made the idea of a fee schedule more acceptable. However, most of its support stemmed from the perception that current payments were not balanced across types of services and geographical areas. Passage of MFS was also expedited by strong support from physician groups representing family and primary care physicians and ultimately with support from the AMA. The AMA opposed the VPS and lobbied against them. However, surgeons agreed to VPS as long as there was a separate update for their services (Iglehart, 1989 and 1990). Congress' decision to use separate updates could prove important because of the distributive effects across specialties.

Basic Features and Timing

Physician payment reform was enacted by Congress through the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 (OBRA 1989) on November 21, 1989 (Ginsburg, LeRoy, and Hammonds, 1990). The core of this reform was to create an MFS with balance-billing limits and Medicare VPS. The purpose of the reform was to enhance incentives for efficiency by setting fees that were more closely aligned with real resource costs, correcting, in particular, the perceived tilt toward surgical and technical procedures relative to visits and consultations in the existing payment system. The point of VPS was to address issues of volume and intensity by basing future fee increases on how expenditures compare with a target.

After a 5-year transition period ending in 1996, MFS rates will be based on an RBRVS that values each service against another according to a work component that reflects the time and intensity of the service provided, a practice-expense component, and a malpractice component. Using RBRVS, fees are established by multiplying by a conversion factor and computing a geographic adjustment factor (Ginsburg, LeRoy, and Hammonds, 1990). Under MFS, there is less geographical variation in fees, particularly between urban and rural areas, than was previously the case. To provide financial protection for beneficiaries, the maximum allowable actual charge limits are eliminated; in 1992, physicians were limited to 120 percent of the fee, with a 115-percent limit from 1993 on (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1992). This change considerably increases the incentives for physicians to accept assignment (or to become a participating physician) and may change a physician's decision about whether to accept Medicare patients.

VPS sets a performance target for physician expenditures that are used 2 years later to update fees (through the conversion factor) in MFS to levels consistent with this target. OBRA 1989 requires separate conversion factors for surgical and non-surgical services starting in 1993 (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993). VPS is determined by Congress, and DHHS has little discretion in this determination. Therefore, the specifics are complex, and they include a formula-driven default option if Congress does not act (Ginsburg, LeRoy, and Hammonds, 1990). To further encourage physicians to practice efficiently, OBRA 1989 also increased support for effectiveness research and practice guidelines.

The initial MFS was designed to be budget-neutral and included a “behavioral offset,” which anticipated a change in volume in response to changing payment rates. The level of this offset was extensively debated, and its accuracy is still a controversial subject. Based on preliminary work for the first half of 1992, PPRC (1993) recently concluded that the behavioral offset was set too high once physician responses to both price increases and decreases were considered. Hence, PPRC inferred that the initial average payment rate was about 2 percentage points too low to achieve budget neutrality.

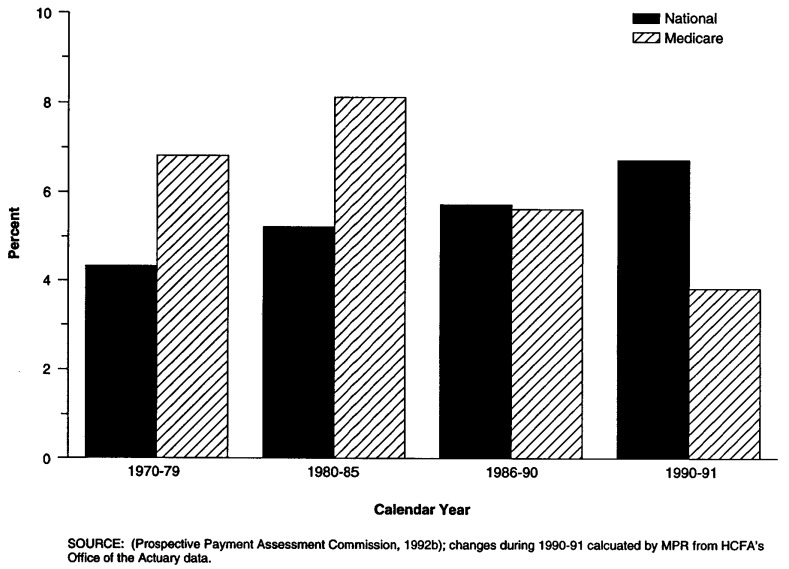

Effects on Cost, Access, and Quality

Research on the effects of the Medicare physician payment reforms is necessarily limited by the fact that implementation is still in progress, and experience is limited. Some preliminary studies based on simulations and limited current experience exist, but it is still too early to determine whether these reforms will act as intended: to constrain spending for physician services and redirect incentives among services without compromising access to or quality of care. Figure 4 shows the trend in real growth in national and Medicare physician expenditures per capita during 1970-91. It shows that Medicare expenditures rose more quickly than the Nation's as a whole through the first half of the 1980s and at about the same rate as the Nation's during the second half. The most recent data covering the period just before Medicare physician payment reforms took effect but after congressional attention focused on issues of physician expenditures show Medicare physician expenditures rising more slowly than the Nation's as a whole.

Figure 4. Annual Percent Change in Real National and Medicare Physician per Capita Expenditures: 1970-91.

Specialty and Geographic Payment Redistribution

Initially, it is expected that under these reforms, payments will be redistributed from procedure-oriented specialists to primary care physicians (Hsiao et al., 1992; Levy et al., 1992). In a very recent analysis, however, Hsiao et al. (1993) find that several structural features of the system mean that physicians will continue to be paid more generously for invasive procedures because of the way practice expenses are handled. Physician payment reform is likely to greatly influence the geographical distribution of payment. Physician payments in rural areas are expected to increase relative to urban areas, substantially narrowing the gap between the two (Levy et al., 1992; Physician Payment Review Commission, 1992). PPRC (1990) estimates that payments to physicians in rural areas would grow 12-13 percent, while payments to physicians in major urban areas would decrease 4-5 percent.

Effects on Volume and Intensity of Care

Whether and how physicians respond to MFS and VPS by modifying volume and intensity of care is a major policy question. For 1990 and 1991, only the surgical VPS standard in 1991 was met; the overall standard (across all specialties) was not met in either year (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993). Preliminary data show that the actual expenditures will fall below standard in 1992. In 1990 and 1991, volume of services increased 2 percent above the historical trend, with part-year 1992 results below the historical rate. However, the pre-1992 experience also reflects responses to pre-MFS payment rate reductions (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993). Because MFS adjusts future updates based on expenditures, growth of volume should not in the-ory influence the ability to meet budget targets on a lagged basis. The debate continues about how best to structure VPS to provide incentives for physicians to work together and reduce spending (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993).

Physician fees are lower in Canada than in the United States. However, this difference is partly offset by increased service use in Canada, which is likely to be a response to lower fees and may be caused by universal coverage for the services (Fuchs and Hahn, 1990). Evidence of a volume offset is reinforced in studies by Christensen (1992), Mitchell, Wedig, and Cromwell (1989), and others. Based on evidence from other countries' experiences with fee schedules and expenditure targets, Glaser (1993) and Barer, Evans, and Labelle (1988) maintain that volume responses can be contained if physician groups are included in the negotiation process.

Effects on Access and Quality

Implementation of MFS does not thus far appear to have affected access or physicians' willingness to see Medicare patients (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993). Baseline access for Medicare beneficiaries appears to be relatively good according to the first round of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (Prospective Payment Review Commission, 1993), although poverty and minority status were associated with less satisfactory access. In a few areas, beneficiary complaints increased with implementation of MFS, but they have since ceased. In a PPRC-sponsored survey of physicians, 94 percent of physicians who accepted new patients were also accepting new Medicare patients. Data from the first 6 months of 1992 show that the total amount of balance billing declined by 34 percent, and that the trend toward higher rates of participation and assignment continued with participating physicians accounting for 76 percent of aggregate physician Medicare payments; 87 percent of payments were for assigned claims. Enforcing charge limits, however, continues to be a problem (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993).

Implementation

Considerable work was involved in developing the Medicare physician payment reforms, and more work will likely be required as refinements are introduced and implementation continues on schedule. Hsiao et al. (1993) argue that the monetary conversion factor used in MFS yields an unreasonably low amount of money for most specialties. Ginsburg and Hogan (to be published) agree that the Medicare conversion factor probably is not appropriate for an all-payer system but disagree with Hsaio's analysis and point out that MFS reduces, not exaggerates, income differences across specialties. Zuckerman and Holahan (1992) show that wide differences in volume and intensity across services, specialties, and geographic areas mean that the use of the current two VPS standards could be inequitable and suggest that more targets should be used. A recent PPRC-sponsored survey of physicians indicates that they have a poor understanding of the payment reforms after more than 6 months' experience with MFS (Physician Payment Review Commission, 1993). There is evidence that some private insurers and State Medicaid programs are adopting the Medicare RBRVS. CBO (1991) estimates that savings would accrue from extending Medicare physician and hospital payment systems to a single-payer or an all-payer system.

State Hospital Ratesetting Programs

Summary of Program

Impetus and Context

State programs to regulate hospital rates began in earnest in the 1970s (Sloan, 1983; Dowling, 1974; Davis et al., 1990). The first substantial Federal support for such programs was provided through section 222(b) of the 1972 amendments to the original Medicare legislation. Section 222(b) supported incentive payment demonstrations that included voluntary and mandatory ratesetting programs (Davis et al., 1990). The rationale for establishing hospital ratesetting programs varied from State to State, but restraining the growth in hospital spending was a key goal for all or most States. Other goals included improved equity across diverse payers and compensation for expenses viewed as socially desirable, such as uncompensated care. State programs were enacted in an era of intense regulatory activity within States, involving capital controls (especially certificate-of-need programs) as well as hospital ratesetting. Carter-era hospital cost-containment efforts in the late 1970s resembled in some ways the State ratesetting approach and included provisions to exempt State all-payer ratesetting from the proposed national controls.

The majority of States (27) had some form of hospital ratesetting program in 1980, but the programs varied considerably (Davis et al., 1990). Most were voluntary, with hospitals choosing whether to participate or comply. Only eight States had programs that involved mandatory review and compliance with rates or budgets set by a State ratesetting authority: Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Washington, and Wisconsin. Programs in all of these States except Illinois and Wisconsin began in 1976 or before and subjected the majority of non-Medicare hospital revenue to review (Biles, Schramm, and Atkinson, 1980). Four States—Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York—covered for some period of time during the 1980s all payers of hospital care. This discussion of ratesetting focuses on results for the mandatory ratesetting States, especially those covering all or most payers. Research shows that mandatory programs control costs much more effectively than do voluntary programs (Coelen and Sullivan, 1981; Sloan, 1983).

Basic Features and Timing

State ratesetting programs involve a number of features that vary both from program to program and within the same program over time (Davis et al., 1990; Coelen and Sullivan, 1981). Two key features are the unit of payment and the way in which the payment rate is set:

Regulation of the Unit of Payment

Programs either limit the total revenue of a hospital or establish per service, per diem, or per case payment rates. Programs that attempt to control total revenue usually set an annual revenue target for each hospital. (Various review and incentive provisions are triggered if a hospital does not sufficiently adjust charges to meet the target.) Over time, programs have moved away from controls based on per service or per diem payments toward more aggregate payment controls, which limit incentives to increase volume in response to payment controls.

Determination of the Base Rate and Future Increases

Ratesetting requires a base rate to be calculated and some standard to be established for allowing increases in this base rate over time. Most State programs establish base rates by reviewing hospital costs against standards for reasonableness; these reviews often involve screening and comparisons against “similar” hospitals in the State or area. Programs vary in how they define hospital financial requirements and how they may treat such expenses as bad debt and charity care. State programs also vary in their reviews: Some are more stringent than others, and their methods differ, as does the level at which the review is conducted (department or aggregate hospital level). Reviews at the department level can better identify some high costs to exclude, but such reviews entail higher administrative costs and potentially less managerial flexibility than reviews at the hospital level. Base rates are periodically updated for inflation; an exogenous standard, such as the hospital market basket, is typically used to avoid creating an incentive to increase present costs to justify future rate increases. However, some adjustments are allowed either routinely, or upon appeal or exception, based on institution-specific factors.

State ratesetting programs differ in the proportion of hospital revenue controlled through the system based on the number of payers covered by the program. Covering a larger share of revenue should in theory increase the potential for cost saving because it limits the ability to shift costs to other payers. Programs also vary in the methods used for each payer and in how the system handles allowable rate differentials across payers if they are allowed to differ.

Because of changes in State ratesetting programs over time, we emphasize the more recent research in the late 1970s and early to mid-1980s. However, much of this research was completed before States fully implemented changes that moved them toward more aggregate forms of control or before they responded to the PPS environment.

Four All-Payer Programs

Four States' ratesetting programs have for some time during the 1980s covered all payers: Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York. Maryland was the first to have an all-payer program. Enacted in 1971, it is now the only remaining all-payer program. Maryland began regulating hospital rates in 1974, and the system has covered all payers since 1977 when Medicare and Medicaid were added. Unlike PPS and many other State programs (Anderson, 1992), Maryland rates are hospital-specific, and the initial implementation of the system involved a detailed budget review. Rates include an allowance for reasonable bad debt and charity care. Starting in 1976, the program began to shift (on a voluntary basis) from a budget-review system covering units of service to a guaranteed inpatient revenue program, which regulates revenue per case adjusted for case mix. This approach establishes a revenue constraint but allows flexibility in billing and differs from New Jersey's DRG-based case payments. By 1985, 34 of the State's 56 regulated hospitals had opted into the system (Rosko, 1989).

Financial distress among Maryland hospitals played a major role in establishing the Maryland system, which has been developed with support and collaboration from the hospital industry since its inception (Worthington, Tyson, and Chin, 1980; Ginsburg and Thorpe, 1992). Several observers have emphasized the unusual composition of the Maryland Hospital Association, which is made up of hospital trustees rather than hospital administrators, as an important reason for support from the industry (Worthington, Tyson, and Chin, 1980). Cohen and Colmers (1982) also argue that two factors unrelated to Maryland's system have limited its ability to control total hospital spending: the (independent) expansion of hospital beds in the State and changing migration patterns from Washington, DC, both of which factors increased per capita hospital spending.

Although the program in Massachusetts was enacted in 1968, the State did not regulate rates until 1975 (Biles, Schramm, and Atkinson, 1980). The impetus for the program was based on concerns about large increases in private hospital insurance premiums and employer contributions to health benefits (Davis et al., 1990). All payers were included as of 1982. In 1985, the program dropped Medicare primarily because hospital revenues were more restricted than under the PPS alternative. This occurred because of Medicare waiver requirements that rates set under the waiver not exceed Medicare payments in the absence of a waiver (Davis et al., 1990). After 1985, the program continued for other payers. Compared with the other three States that obtained Medicare waivers, the evolution of the Massachusetts program is less documented in the literature on ratesetting. However, in the early 1980s, the State applied different payment approaches to different payers. Medicaid used a formula payment to set a per diem rate, Blue Cross reimbursed based on prospectively determined maximum allowable cost, and charge-based payers paid approved charges that covered financial needs (Esposito et al., 1982).

Like Maryland, New Jersey enacted its system in 1971 and began setting rates in 1975 for Medicaid and Blue Cross. Legislation bringing in all payers was enacted in 1978 (Iglehart, 1982), and Medicare was dropped in 1989. Initially, the program set rates on a prospective per diem basis through the Standard Hospital Accounting and Rate Evaluation (SHARE) system.

In 1980, New Jersey began to phase hospitals into a DRG-based all-payer system (Hsiao et al., 1986). This arrangement drew upon several years of HCFA-sponsored research with DRGs and built in payment for bad debts. Key reasons for implementing DRGs involved a growing concern about (1) hospital bad debts, which threatened the viability of inner city hospitals, and (2) the growing differentials between Blue Cross and unregulated charge-based payers (Hsiao et al., 1986; Davis et al., 1990). In the early 1980s, the program was deliberately generous to providers as the new system was established (Iglehart, 1992).

In 1992, the U.S. District Court ruled that the New Jersey system, by placing a surcharge on inpatient bills to fund uncompensated care, regulated self-insurance and hence violated the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) preemption. In response to this ruling, the State enacted legislation that both refinanced uncompensated care and dismantled its DRG system after a 1-year transition period. In a recent issue of Medicine and Health (December 7, 1992), one expert noted, “There was nothing in the judge's order that said you have to get rid of DRGs… the push to deregulate came not so much from the legislators, as from the hospitals, the medical societies, and the HMOs.”

New York enacted its ratesetting program in 1969 and began setting rates in 1971 (Biles, Schramm, and Atkinson, 1980). Medicare was included in 1983, but as in Massachusetts, Medicare was dropped in New York in 1985 in order to reap additional PPS payments estimated at $200 million. The program continued for other payers (United Hospital Fund, 1993; Anderson, 1991) but has been changed in several major ways since first implemented.

Prior to 1983, rates were prospectively set only for Medicaid and Blue Cross, though charges for others were limited to some extent (Romeo, Wagner, and Lee, 1984; Thorpe, 1987). In 1983, a prospectively determined, cost-based, all-payer per diem rate cap was established for peer groups of hospitals. Rates were trended forward, and per diem adjustments were made for capacity and case-mix changes. The revenue cap excluded charge-based payers, who were restricted to per diem rates of a fixed differential over Blue Cross per diem rates (Thorpe and Phelps, 1990). In 1988, the State adopted a case-based prospective payment system under which all commercial insurers pay the same amount for inpatient care, and Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans, HMOs, and Medicaid pay lower rates. Over the years, the system has also included a bad-debt and charity pool, a fiscally distressed fund, a transition fund, and discretionary allowance (Thorpe, 1987).

The initial impetus for this program was concern over Medicaid costs in the face of a severe budget crisis (Davis et al., 1990). New York is also unique in that it placed extensive controls on hospital capacity at the same time that the ratesetting system was introduced (Cromwell and Kanak, 1982). Like New Jersey, New York in 1992 faced a court challenge based on ERISA to its method for financing uncompensated care through its ratesetting system (United Hospital Fund, 1993). The ultimate effect of the challenge on the system is unknown.

Effects on Cost

Research generally agrees that since 1975, mandatory ratesetting programs as a whole have generated savings and a downward trend in hospital inflation that has been sustained over time. Savings are partially offset by volume responses that are consistent with incentives in the different systems. However, research also appears to show that mandatory ratesetting programs are effective when savings are measured on a per capita basis, as well as per diem and per admission, even though per capita savings are lowest.

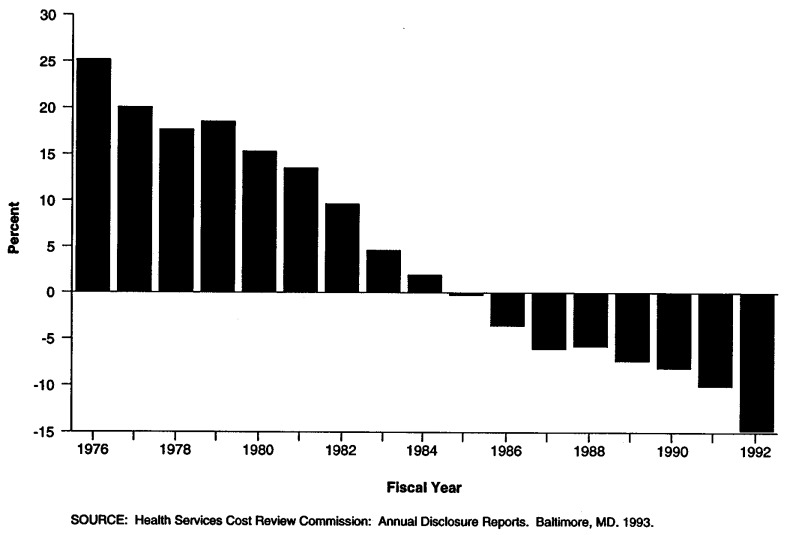

Research results are mixed as to whether partial-payer systems, especially those that exclude Medicare, can perform as well as all-payer systems. This issue has been complicated since 1983 by the fact that PPS serves to set Medicare rates, albeit with rates and methodologies that differ from those in State systems. There is little agreement either on which ratesetting States have been most successful in controlling costs or on which approaches underlie the most effective programs. Although policymakers and others are concerned about how ratesetting may influence innovation and the growth of managed care, there is little research on this topic. Figure 5 shows the trend in cost per hospital admission from 1976 through 1992 in Maryland, the first and only remaining all-payer State. It shows that cost per admission among Maryland hospitals steadily declined relative to the U.S. average, moving from 25 percent above the national average to 14 percent below it.

Figure 5. Maryland Cost per Admission as a Percent of U.S. Cost per Admission: 1976-92.

Effects on Expenditures

Sloan concludes (1983) that all regression analyses that included post-1975 data show that mandatory ratesetting programs reduce growth in hospital cost inflation by about 3-4 percentage points a year relative to other State programs. Subsequent literature reviews by Eby and Cohodes (1985) and Anderson (1992) show similar findings, indicating that conclusions are similar across time periods, methodologies, and measures of impact. Most of the States with mandatory programs have had such programs in place (although they have been evolving) since the mid-1970s. At least through 1986, there is evidence of continued reduction in the rate of hospital cost growth relative to growth in costs in other States (Robinson and Luft, 1988; Schramm, Renn, and Biles, 1986; Hadley and Swartz, 1989).

The studies that used per capita measures of hospital or health care expenses generally have found that ratesetting generates significant net savings. However, the impact of ratesetting in these studies is generally weaker than that in the bulk of studies, which use per unit measures. We found one multivariate study that used total health care expenditures: The U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO)(1992) estimated that in 1982, total health care expenditures per capita were $80 lower in States with ratesetting programs than elsewhere ($175 lower in Maryland and New Jersey). Although the paucity of research prevents us from drawing conclusions in this area, the GAO study provides preliminary evidence that where hospital costs have been controlled, the costs do not fully shift to non-hospital providers. A few other studies suggest that physician expenditures are lower in States with ratesetting (Anderson, 1992; Morrisey, Sloan, and Mitchell, 1983). Studies finding savings in per capita hospital costs include Morrisey, Sloan, and Mitchell (1983), Coelen and Sullivan (1981), and Schramm, Renn, and Biles (1986). Researchers in the first study found an average 2-3 percent reduction in real per capita hospital expenditures during 1968-81.

There is some evidence that per diem systems increase utilization of services, offsetting some savings. The national hospital ratesetting study found that significant increases in length of stay were associated with all three programs that set rates on a per diem basis (New Jersey, New York, and Western Pennsylvania) (Worthington and Piro, 1982). No effects on admissions per capita or per bed were found in that study, although a subsequent multivariate study of the Maryland program found some evidence, albeit weak, of an increased rate of admissions, and tabular analysis has been presented both to support and refute the hypothesis that ratesetting increases utilization (Salkever and Steinwachs, 1988; Schramm, Renn, and Biles, 1986; Finkler, 1987).

Relative Effectiveness of Different Programs

There is no agreement as to which State ratesetting programs have been most successful in controlling costs, and little as to why these programs differ in effectiveness. Studies of individual States have differed in methods, timing, and data, and—not surprisingly—have found different magnitudes of savings for the same States. A recent multivariate study of individual States finds Massachusetts and Maryland to be most effective in controlling costs, reducing inflation by 16.3 percent and 15.4 percent, respectively, during 1982-86 (Robinson and Luft, 1988). Another recent study, which grouped Massachusetts and New York together, finds that the programs in the two States resulted in greater and more sustained savings than did programs in Maryland and New Jersey in 1980-84 (Hadley and Swartz, 1989). GAO (1992) finds that, of the ratesetting States, New Jersey had the lowest total health care expenditures not explained by other factors in 1982. Eby and Cohodes (1985), reviewing two other studies that assessed the impact of ratesetting in individual States, find that the two studies presented 57 opportunities to find effects of ratesetting (using different models and measures of cost), 41 of which showed statistically significant effects. The percentage of effects that were significant varied by State but were highest in New York and New Jersey (where 89 percent were significant).

Features Contributing to Effective Programs

Researchers have not found that there are administrative features common to the most successful mandatory ratesetting States that distinguish them from other States, except that during the prePPS period, all-payer systems may be most effective in reducing cost growth. In a study that used 1982-83 data, Zuckerman (1987) finds that partial-payer as well as all-payer mandatory systems reduce expenditures compared with unregulated States, but all-payer systems appeared to have some short-term advantages in restraining hospital spending. Hadley and Swartz (1989) report results consistent with Zuckerman's findings. In their econometric study (covering 1980-84), they find that all-payer States have costs 11-15 percent lower than those in unregulated States, with States that cover all payers except Medicare having costs 11 percent lower. In contrast, Medicaid-only regulation was ineffective.

Other relevant findings are: (1) Ratesetting seems to work by reducing costs in hospitals above the controlled level but does not have the same effect on low-cost hospitals that are given the opportunity to profit by further reducing costs (Thorpe and Phelps, 1990; Salkever, Steinwachs, and Rupp, 1986); and (2) ratesetting seems to lower costs most among hospitals with many neighbors (Robinson and Luft, 1988). The earlier, comprehensive national hospital ratesetting study sponsored by HCFA did not find features common to the most effective programs, and other researchers have pointed to the dearth of findings in this area (Coelen and Sullivan, 1981; Eby and Cohodes, 1985).

Innovation and Growth of Managed Care

The issue of the relative effectiveness of regulatory and competitive approaches to cost containment has generated a considerable body of research arguing for and against the respective merits of State ratesetting (see, for example, Mitchell [1982] and the responses it generated). Robinson and Luft (1988) conclude from their research that both ratesetting and California's market-oriented cost-control policy can generate savings, with some State ratesetting programs outperforming those in California. In contrast, Hadley and Swartz (1989) report results showing that, although HMO growth produces some savings, such savings are much smaller than those generated by ratesetting programs and are potentially trivial in magnitude. No savings were found from competition (as measured by prevalence of for-profit hospital beds and the physician-to-population ratio).

A key issue is whether ratesetting is compatible with innovation in delivery and especially with the growth of managed care (Ginsburg and Thorpe, 1992). Ratesetting States include those with above-average penetrations of managed care, although there is no research on this topic (Anderson, 1991). There is some perception that New Jersey's ratesetting program created difficulties for HMOs (Iglehart, 1982).

Practically, implementation issues include whether to allow an exemption for HMOs or other managed care organizations. If an exemption is not provided, the issue is whether and under what circumstances a payer differential should be allowed, and what amount this differential should be. Another way of considering this issue involves making a decision about the extent to which managed care organizations can negotiate discounts and whether hospitals are allowed to offset discounts through higher rates for other payers. A final policy issue is that ratesetting programs generally fund services considered to be socially desirable (such as graduate medical education and uncompensated care). To the extent that managed care organizations are exempt from ratesetting regulations designed to fund these services, some hospitals may find it difficult to both protect their market shares of area patients and adequately finance the services they provide.

Based on a review of current experience in ratesetting States, Ginsburg and Thorpe (1992) note that such States provide examples of both significant restrictions on competitive plans and lack of restriction. For example, in Massachusetts, HMOs are free to contract with hospitals in any manner, and enrollment in such plans increased dramatically in the 1980s (to 26.5 percent of residents enrolled in a prepaid plan by 1990). In New York, however, HMOs must undergo rate hearings to obtain permission to pay hospitals rates that differ from those set for other payers.

Access, Quality, and Other Measures

Research generally, but not consistently, shows that all-payer ratesetting increases access because it provides payment for uncompensated care and improves the position of hospitals serving the poor. No consistent relationship between ratesetting and quality has been found. Studies generally appear to show that ratesetting has not had an adverse effect on hospital operating margins and that it may improve margins for some hospitals that were under fiscal stress at the start of the program.

Effects on Access

The evidence is limited, but mixed, on how ratesetting affects access. Studies of programs in New York and New Jersey find that they have increased access to care for the uninsured (Thorpe, 1988; Hsiao et al., 1986); both admissions and hospital days for uninsured patients increased relative to the insured population in New York (Thorpe, 1988). Hsiao et al. (1986) conclude that access to care in New Jersey has been improved by strengthening the financial positions of the providers that serve the poor. However, a national study (although its sample may have been biased) concludes that hospitals in waiver States (no hospitals in New Jersey were included) were less likely than all other States to increase their share of self-pay patients (Sloan, Morrisey, and Valvona, 1988).

Effects on Quality and Technology Diffusion

Studies on the relationship between ratesetting and patient mortality rates, limited by methodological problems, have not found that this relationship is consistent (Anderson, 1991). Gaumer et al. (1989) find some relationship between ratesetting and mortality rates, but no association between the stringency of the program and the mortality rates. However, Gaumer, Poggio, and Sennett (1987) find no significant relationships, and most recently, Smith, McFall, and Pine (1993) conclude that “a cautious interpretation is that rate regulation has done no harm,” and there are some indications that it may be beneficial.

There are few studies on hospital responses to ratesetting that might shed light on whether such responses are likely to jeopardize quality (Eby and Cohodes, 1985). A study of New Jersey (Broyles, 1990) finds that the system resulted in a lower volume of radiology procedures per day (which Broyles believed might reduce quality), but in a higher volume of ancillary care per day and per case and shorter lengths of stay (which Broyles believed might indicate improved quality). The author concludes that quality may suffer less than imagined under such systems.

Although the few studies focusing on technology diffusion are limited, they suggest that overall, mandatory ratesetting may affect technology diffusion. Using a random sample of hospitals nationwide, Cromwell and Kanak (1982) found that complex services were diffusing at about three-fourths the nationwide rate in States with mandated ratesetting. The authors note, however, that it is impossible for them to separate the effects of certificate of need in New York, for example, from its ratesetting program in terms of the effects on diffusion. Romeo, Wagner, and Lee (1984) also found that there was an effect on technology diffusion in New York and concluded that New York's system had a more powerful, inhibiting effect on the extent to which the five technologies studies were adopted than on the decision to adopt the technology. However, no effect on technology diffusion was detected for Maryland's system.

Effects on Providers