Abstract

This study aimed to explore the mental health needs of women residing in domestic violence shelters; more specifically, we aimed to identify commonalities and differences among their mental health needs. For this purpose, qualitative and quantitative data was collected from 35 women from a Midwestern domestic violence shelter. Hierarchical clustering was applied to quantitative data, and the analysis indicated a three-cluster solution. Data from the qualitative analysis also supported the differentiation of women into three distinct groups, which were interpreted as: (A) ready to change, (B) focused on negative symptoms, and (C) focused on feelings of guilt and self-blame.

Keywords: Mental health, intimate partner violence, cluster analysis, women

Violence against women is a prevalent problem around the world (Garcia-Moreno, Heise, Jassen, Ellsberg, & Watts, 2005). It has a profound and negative impact on women’s ability to live happy and productive lives (Kilpatrick, 2004). Violent acts against women include rape, incest, physical violence, and emotional abuse (Barnett, Miller-Perrin & Perrin, 2011). While both men and women are victimized, prevalence rates of violence against women are higher (Johnson, 2008). Furthermore, as compared to men, women are more likely to be terrorized, injured, or killed by violence, regardless of their ethnicity, race, or socio-economic status (Johnson, 2008; Kellerman & Mercy, 1992).

Also referred to as domestic violence or spousal abuse, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) results in exorbitant physical, emotional, and economic costs, and death is not an uncommon result (WHO World Report on Violence and Health, 2002). According to a literature review by Campbell (2002), injurious physical and mental health sequelae of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) include injury or death, chronic pain, gastrointestinal and gynecological problems, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many women also suffer rape and violence during pregnancy, causing harm to both mothers and children.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has numerous mental health consequences for women (Golding, 1999; Kilpatrick & Acierno, 2003; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; National Center for Injury Prevention in Control, 2003; Schnurr & Green, 2004). These consequences include depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and low self-esteem (Afifi, MacMillan, Cox, Asmundson, Stein, & Sareen, 2009; Bonomi, Anderson, Rivara, Carrell, & Thompson, 2009; Kilpatrick 2004; Logan, Cole, Shannon, & Walker, 2006; Straus & Smith, 1990). In order to diminish the effects of IPV, it is important to understand these consequences and develop treatment modalities that better serve women experiencing IPV. There is abundant literature on the mental health consequences of IPV. Most of these studies investigate the prevalence of mental health problems among women with a history of intimate partner violence or focus on a single mental health problem (Arboleda-Florez & Wade, 2001; Dienemann, Boyle, Resnick, Wiederhorn, & Campbell, 2000; Kernic, Holt, Stoner, Wolf & Rivara, 2003).

In contrast, we aim to identify the symptoms that are seen together among different groups of women. More specifically, the aim of this study is to investigate the self-identified mental health needs of women in domestic violence shelters, and explore the commonalities and differences among these needs. For this purpose, we have collected quantitative and qualitative data on the self-reported mental health needs of women residing in a domestic violence shelter through checklists and interviews. Subsequently, we applied cluster analysis to the quantitative data to identify groups of women that are similar to each other in terms of their mental health needs. Finally, we used content analysis on the data obtained from the interviews to delineate the common mental health needs identified in each cluster.

Background

Depression

One of the predominant adverse effects of violence against women is an increased likelihood of clinical depression (Anderson, Saudners, Yoshihama, Bybee, & Sulivan, 2003; Arboleda-Florez & Wage, 2001; Dienemann, Boyle, Resnick, Wiederhorn & Campbell, 2000). Depression negatively impacts sleep and causes alarming changes in appetite, energy level, and the ability to function. Depression can eventually lead to suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Straus and Smith (1990) found female victims of severe male battering were four times more likely than non-victimized women to be depressed and/or attempt suicide.

Several studies have demonstrated the role of violence on clinical depression. Kernic, Holt, Stoner, Wolf, and Rivara (2003) conducted a longitudinal study on depression in battered women and found severity of depression decreased once abuse ceased. Coolidge and Anderson (2002) compared the personality profiles of three groups of women and classified them as follows: Group A: multiple abusive relationships; Group B: one abusive relationship; and Group C: no abusive relationship. Using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th revision (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000), the mental health profiles of these three groups of women were scored. Results showed women in Group A had significantly higher prevalence rates and more severe levels of psychopathology, with the most prevalent Axis I disorders being PTSD (36%) and Depression (17%), and the most prevalent Axis II disorder being Dependent Personality Disorder (21%). Women in Group B had higher rates and levels of psychopathology when compared to the control group (Group C). These findings also demonstrated battered women are not necessarily a homogenous group, and they may have a variety of mental health issues depending on the type of violence they experience.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD is another commonly reported mental health issue for women who experience IPV. A study by Mertin and Mohr (2001) suggested 40 to 60% of female victims suffer from PTSD. The development of PTSD involves exposure to traumatic stressors (violence), followed by fear for one’s safety and a sense of helplessness to control the situation. Some of the common symptoms of PTSD include: re-experiencing the event via flashbacks and nightmares, avoidance of reminders of the event, emotional numbing and increased physical arousal (e.g., heightened startle response, difficulties sleeping; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The development of PTSD is particularly likely for victims of sexual assault (Kilpatrick, 2004). Some victims of violence have a number of PTSD symptoms, but do not meet full diagnostic criteria for a formal diagnosis of PTSD. This suggests there is an increased variability of trauma and anxiety in women who have been victimized by violence compared to those who have not (Stein, Walker, & Forde, 1997). Also, the extent to which female victims develop PTSD or other anxiety disorders depends on the extent and severity of the exposure to abuse (Follette, Polunsy, Bechtle, & Naugle, 1996).

Substance Abuse

Female survivors of IPV are more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol. They receive prescriptions for more drugs and become dependent on drugs more often than non-victimized women. Fowler (2007) examined a sample of 102 women in a domestic violence shelter and found over two-thirds of women scored in the moderate to high category for risk of substance abuse. In addition, nearly 60% of the women were alcohol dependent, and 55% were drug dependent. In a study conducted with 71 domestic violence shelters for women in North Carolina, 47% percent of the shelters reported 26 to 50% of the women in their shelter had substance abuse problems, and 24% reported more than 50% of their clients had substance abuse problems (Martin et al., 2008). Other studies have replicated findings showing elevated levels of alcohol use among victims of IPV (Danielson, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998; Watson et al., 1997). In addition, more frequent victimizations are linked to a greater likelihood of substance use in women (Logan et al., 2006). Golding (1999) conducted a meta-analytic review of intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders. This study did not find any links relating temporality of substance abuse to intimate partner violence. However, in later years, more research identified substance use as a crucial risk factor both for victimization and perpetration of IPV (Caetano et al., 2000, Caetano et al., 2001, Chase et al., 2003, Coker, Smith, McKeown, & King, 2000, Cunradi et al., 2002, and White and Chen, 2002). Findings predominantly indicated two-thirds of women in substance abuse treatment programs reported IPV victimization in the pretreatment year (Drapkin et al., 2005, Lipsky, 2010 and Najavits et al., 2004).

Self-Esteem

Victims of violence are likely to feel guilt, shame, and self-blame for being abused (Lindgren & Renck, 2008; Weaver & Clum, 1995). Unfortunately, this can contribute to a vicious cycle as victims who have negative self-images are less likely to take steps to avoid or exit abusive relationships (Clements & Sawhney, 2000; Umberson, Anderson, Glick, & Shapiro, 1998). Further, self-esteem damage can occur if acquaintances or professionals blame the victim for not preventing her abuse (Eddleson, 1998). These types of negative societal reactions are possibly related to several of the mental health issues such as depression or anxiety that are common among victims of IPV.

As the aforementioned passages demonstrate, IPV has a wide variety of mental health consequences for women that can range from mild to severe. The aim of this paper is to explore self-identified mental health needs of women who are victims of severe IPV, identify common patterns of mental health needs for these women; and to identify groups of women that are similar to each other in terms of their mental health needs.

Method

Sample

Participants in this study were 35 women residing in a domestic violence shelter in a Midwestern town. Some of these women came from smaller towns nearby that did not have domestic violence shelters. Women reported being physically and/or emotionally abused by their husbands (34%), boyfriends (18%), ex-boyfriends (3%), or ex-husbands (3%), and the remaining 42% did not report their relationship with the abuser. Participants were mainly referred to the shelter through police services, local hospitals, other overcrowded shelters, or self-referral through hotlines.

The average age of the participants was 34.63 years (SD = 11.02), ranging from 18 to 54. The participants were from a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds including European American (n = 14, 40 %), African-American (n = 7, 20%), Hispanic (n = 2, 6%), Asian-American (n = 1, 3%), or other ethnicities (n = 2, 6%); one quarter (n = 9) did not report their race/ethnicity. Of the 35 women, 26% (n = 9) had less than a high school education, 37% (n = 13) had a high school degree, 14% (n = 5) had some college education, 3% (n =1) had a college degree, 3% (n =1) had a Ph.D., and 17% (n = 6) did not report their education. Fifty-one percent (n =18) of the women reported having children; among those women, the average number of children was 2.41.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through mailbox announcements at the domestic violence shelter. Interested participants contacted the investigator to arrange a time for participating in the study. Before data collection, women were briefed about the study and were asked to sign consent forms. After participants signed the consent forms, they completed questionnaires that covered demographic information, a mental health checklist, and their previous experiences with mental health providers. The checklist was designed for this study and included a range of issues such as assertiveness, stress, depression, anxiety, and parenting. Participants were asked to check any of the items that were causing them any difficulty. The items were not rated or ranked by the participants. Participants were also asked if there was anything else they would like to add to the checklist. Completing the questionnaires took approximately 10 minutes. The aim of the checklist was to include a wide range of possible issues that might be experienced by the participants. The checklist was based on a local mental health clinic’s experience on the common issues reported by their clinical population. This checklist was revised and adapted based on discussion with the research team and some items were deleted to better reflect the needs of the shelter population.

After the questionnaires were completed, clinical interviews were conducted by a Licensed Couple and Family Therapist to develop a deeper understanding of self-identified mental health needs. The therapist has previous experience working at non-profit institutions such as juvenile justice systems, community mental health services, and domestic violence shelters. She received training in cultural competency. Also, an AAMFT approved supervisor supervised the clinician. Throughout the interview, the therapist attempted to assist women in feeling comfortable in order to facilitate the collection of pertinent information.

The interviews were set up as unstructured clinical interviews to allow the participant more control over the subject matter and direction of the interview. Indeed, in past research, unstructured clinical interviews were found to be well-suited for gathering information (Robson, 2002). The duration of the interviews ranged from half an hour to two hours. The interviews started with a general question and narrowed down depending on the response from the participants. Open-ended questions were asked to garner more details from the participant. Some examples of these questions included: “?What brings you here?”?, and “?When did this happen?”?, followed by questions about the self and the relationship: “?Do you have children?”?, and “?How long have you been together?”?. Subsequently, the participant was asked questions regarding symptomology: “?What are the difficulties you are experiencing?”? The interviewer followed up on each difficulty by asking questions such as: “?How long have you had this difficulty?”?, “?Is there any event that is precipitating this difficulty?,”? “?How are you coping with this?”?, and “?Do you have a support system?”?

Notes taken by the interviewers were used in qualitative analysis. The interviewer took the notes. The interviewer received training on DAP reporting formatting designed for clinicians. Specifically, DAP format stands for taking notes on Data, Assessment, and Planning. It includes both subjective and objective information about the interviewee and the therapist’s observations. “?Data”? refers to content and process notes from the interview. “?Assessment”? refers to the therapist’s clinical impressions, hunches, hypotheses, and rationale for the therapist’s professional judgment. “?Planning”? refers to the original treatment plan and any response/revisions needed based on the most recent interactions with the client. Such method of clinical note taking is a commonly accepted format for documentation.

Data Analysis

Using the mental health checklist filled out by all participants, statistical cluster analysis was conducted to group individuals based on the similarities between their self-identified mental health needs. Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to identify the number of clusters that were present in the sample. Once the number of clusters was determined, results were used to distribute the individuals into clusters. After all the clusters were identified, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to understand the distribution of several demographic and descriptive variables across clusters. The significance of the reporting frequencies of each difficulty was also assessed. For this purpose, binomial distribution was used to compute p-values based on a null model that assumes uniform distribution of all difficulties across all women. All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 17. Finally, in order to understand the validity of the clusters, content analysis was conducted based on the notes from clinical interviews.

Results

According to preliminary exploratory analysis, 42% (n =15) of women reported suicidal ideation, and 31% (n =11) reported attempting suicide at some point in their life, ranging from 2 weeks to 17 years ago. For actively suicidal women, suicide assessment was conducted and necessary precautions were taken. Moreover, 34% of women (n =12) reported regularly taking various medications for their mental and physical health.

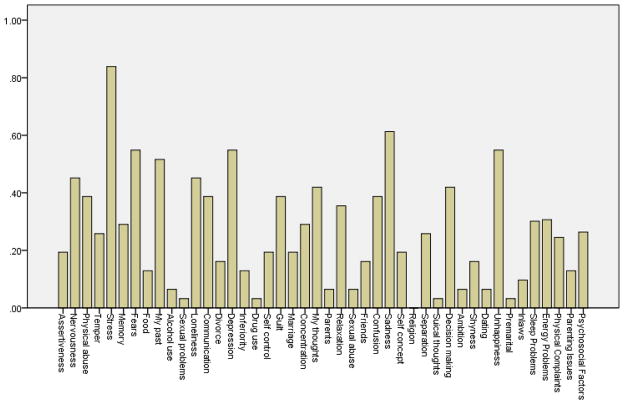

Frequencies of self-identified mental health needs are shown in Figure 1. According to this table, stress was the biggest concern among women who had been abused. The next line of commonly observed issues consisted of sadness, depression, and unhappiness. Drug use was the least commonly reported issue. The self-identified mental health needs in Figure 1 were directly derived from the participants’ responses to the checklist.

Figure 1.

Column graph based on means of the self-identified mental health needs of abused women

Hierarchical cluster analysis based on Ward method was used to assign individuals into groups. The variables considered in cluster analysis were the self-identified mental health needs, which were represented as dichotomous variables. Each variable represented a mental health need in the checklist, and the variables that represent the needs reported by a participant were assigned a value of “?1”?, while those that were not reported were assigned to “?0”?.

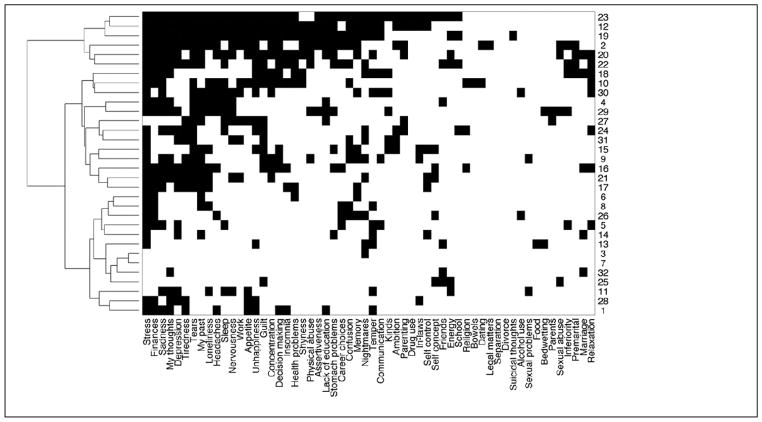

The results of cluster analysis are shown in Figure 2. Analysis of the dendrogram and agglomeration schedule suggested an inconsistent increase in the dissimilarity measure after the combination of variables, suggesting the clustering process should be stopped one stage prior to this, at which point a three cluster solution was found to be optimal. To test the validity of the clusters, the sample was randomly divided into two groups and the cluster analysis was repeated. Results of clustering for each of these two groups were similar to that for the entire set of participants.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of the mental health issues of women residing in a domestic violence shelter. Vertical axis shows participants, horizontal axis shows issues, a dark cell indicates that the respective participant mentioned the respective issue. Participants that are clustered together are shown next to each other as indicated by the dendrogram on the left.

In order to further test the adequacy of the three-cluster solution, discriminant function analysis was conducted to estimate membership based on the checklist. Results indicated all participants were correctly assigned to their respective group, suggesting these three groups were distinguishable from each other. Finally, a number of ANOVAs were performed on age, education, and income. Results indicated no significant differences between the three groups in terms of these three demographic variables.

The first group identified by cluster analysis was composed of 13 women. As compared to the other two groups, this group of women reported fewer mental health issues. Among these women, stress (n =8, p<.01) and physical abuse (n =6, p<.05) were the most frequently and significantly reported issues. The second group was composed of 15 women who reported having problems mainly related to depression (n =14, p<.01), sadness (n =12, p<.01), unhappiness (n =11, p<.01), decision making (n =10, p<.01), fears (n =9, p<.01), loneliness (n =8, p<.01), sleep (n =8, p<.05), headaches (n =7, p<.05), and stress (n =14, p<.01). The last group consisted of four women. In addition to common mental health issues reported by other women such as stress and fears, this group of women reported a wider array of problems. These problems included sleep problems (n =4, p<.01), nervousness (n =4, p<.01), temper (n =4, p<.01), guilt (n =3, p<.01), concentration (n =3, p<.01), and shyness (n =3, p<.01). In order to elaborate the interpretation of these three groups, qualitative analysis was used to account for the data from clinical interviews.

Qualitative Analysis

Data from clinical interviews were analyzed using content analysis to explore the differences between three groups that were identified via cluster analysis. Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that is used to identify the existence of certain concepts, themes, phrases, and characters within text. Texts can be described as any written document, conversation (formal or informal), or incidence of communicative language (Berelson, 1952). In content analysis, researchers aim to quantify and analyze the existence of meanings and relationships of such concepts in an objective manner and then make inferences about the messages within the texts (Weber, 1990). In this study, notes from unstructured clinical interviews were analyzed using content analysis to understand the psychological and emotional state of women who were physically abused by their current and previous intimate partners. Results of the qualitative analysis also confirmed the differences between the three groups identified via cluster analysis.

Ready to change

The first group was composed of 13 women. The common characteristics of these women included their aspiration toward life. These women heavily emphasized their needs and wants from life in the clinical interviews. For example, they reported they “?want a relationship that is between equals,”? “?want not be abused,”? “?want not be controlled,”? “? want to create a better life for myself and my kids,”? “?want to divorce,”? “?want to separate,”? “?want a life that does not have violence,”? “?do not want my daughter to see me beaten up,”? “?do not want my children to think it is ok to beat up,”? “?want to break the cycle,”? “?want to protect myself,”? “?want safety,”? “?want to go to school,”? “?want to visit my family,”? “?want to deal with my past,”? “?want a good relationship for myself,”? “?want to be happy,”? “?want my dignity back,”? “?want my confidence back,”? “?want my life back,”? “?do not want this happen again,”? and “?want my daughter to feel safe.”? This group of women were also highly motivated and determined to make changes in their lives. As compared to other groups, they also reported a stronger support system such as their family, friends, co-workers and physicians.

Focused on negative symptoms

The second group was composed of four women. These women talked more about their depressive symptoms such as difficulty in sleeping, feeling “?shut down”?, not taking care of themselves, feeling confused about the situations, feeling angry against themselves for not ending the relationship sooner, feeling unsteady, not having anybody to talk to, difficulty in communicating, and being overwhelmed with stress (n =4). One of the main themes that emerged for this group of women was the feeling of being overwhelmed. One woman reported being overwhelmed by physical abuse, feeling sad and unhappy that the relationship did not work, and feeling unsteady. She felt like every decision she makes backfires and she was afraid to make decisions now. Another woman reported that she feels overwhelmed by the need to take care of her young child. One woman reported that she is having a hard time to read and was overwhelmed and embarrassed by having to ask for help. Another woman reported being overwhelmed by the living arrangements at the shelter. Two women in this group reported not having anyone to talk to and feeling lonely.

Focused on feelings of guilt and self blame

The third group was composed of 15 women. These women reported more severe mental health needs co-morbid with other mental health issues. Substance abuse was most prevalent among these women. Furthermore, they were more likely to report having previous mental health diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, kleptomania, depression, anxiety problems, suicidal ideation, PTSD, disassociation, borderline personality disorder, self-esteem problems, sleeping difficulties, nightmares, and grief. This group of women reported being in an abusive relationship for a longer period of time. They were more likely to describe their experience of abuse and their abuser. They also reported feeling excessively guilty for “?calling the police,”? and described their actions as “?feels like betraying him,”? and “?leaving my husband.”?

Discussion

Data on mental health symptoms were collected from 35 female residents of a domestic violence shelter with the primary purpose of the study being to develop a picture of the mental health needs of female victims of IPV. Not surprisingly, the women reported a range of mental health issues including symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and other symptoms of serious mental health diagnoses. Previous research has clearly established relationships between violent victimization and a wide variety of negative mental health outcomes (Afifi et al., 2009; Bonomi et al., 2009; Kilpatrick 2004; Logan et al., 2006; Straus & Smith, 1990). Specifically, symptoms associated with depression and trauma were the most frequently reported.

According to the DSM-IV-TR, symptoms of PTSD defined strictly diagnostic criteria are clustered into one of three categories: increased arousal, hypervigilance, and emotional withdrawal/numbing. A number of symptoms reported by women in this study may be representative of the descriptions of diagnostic symptoms including stress, fears, nervousness, nightmares, and memory problems. However, definitions of trauma related symptoms are often expanded to include other symptoms reported in this study including guilt, somatic complaints, substance abuse, and self-esteem issues (Carlson & Dalenberg, 2000). The findings are unsurprising given that women with a history of violent victimization are three to five times more likely to develop PTSD (Golding, 1999) and PTSD is relatively common among female survivors of IPV (Mertin & Mohr, 2001).

Depressive symptoms also emerged as a prevalent concern among the women in this study. Almost half the sample (42%) reported suicidal ideation. The women reported many other symptoms often associated with depression including sadness, unhappiness, sleep problems, confusion, temper, and concentration difficulties. The high reported rates of suicidal ideation are consistent with previous research (Straus & Smith, 1990), and there is a clearly established link between violence victimization and depression in the research literature (Arboleda-Florez & Wade, 2001; Golding, 1999; Straus & Smith, 1990).

Perhaps the most interesting finding from the study was that women could be classified into one of three groups: women who are ready to change (mild mental health consequences), women focused on negative symptoms (moderate mental health consequences), and women focused on feelings of guilt and self-blame (severe mental health consequences). While the moderate and severe consequences groups were characterized by symptom intensity and the mild consequences group was characterized more by motivation for change, all three groups differed with respect to the aspects of the abuse on which they focused. The first group was focused on change and moving forward. The second group was focused on the negative symptoms they were experiencing. The third group was focused more on feelings of guilt and self-blame.

Trans-theoretical Model of Change

The characteristics defining each of the three groups of women have parallels to the first three of five stages of change in Prochaska’s Trans-theoretical Model of Change (Norcross, Krebs, & Prochaska, 2011). The precontemplation stage is characterized by the lack of awareness of a problem and little or no intent to change. While it may be unfair to characterize women from the severe symptoms group as lacking awareness of a problem, especially since they have taken steps to enter a shelter, it can be argued, based on the qualitative data, that many women are incorrectly defining the problem. This group was characterized by feelings of guilt and self-blame instead of correctly allocating responsibility for violence to the aggressor. Women in this group may be in precontemplation stage in that they may be underestimating the severity of the situation by comparing themselves to others with more serious problems or they may think nothing can be done because of demoralization by past failures ((Murphy & Maiuro, 2009; Sleutel, 1998).

According to Prochaska’s Model of Change, the contemplation stage of change is characterized by awareness of a problem(s). According to the findings of this study, women in the moderate symptom group were aware of and focused on the negative symptoms they were experiencing. Brown (1997) further noted that women in contemplation stage were trying to make the decision for taking action to end the violence. During the contemplation stage, women figure out how to build social and emotional support systems and explore financial options as a preparation for change.

According to Haggerty and Goodman (2002), woman will act for change when they perceive they will be benefit from change (i.e., the cons of the current situation are more costly than the pros for staying in the relationship). For this reason, the contemplation stage lasts longer for most women as these pros and cons are considered again and again, leading to confusion. Among the reasons that make it difficult to decide are the love for the partner or the feeling that children need a father. These can outweigh the concerns about personal safety for many women. Because of the lack of resources or referrals and the presence of such doubt, taking action becomes even more difficult for women (Griffings et al, 2002, Prochaska, 2002).

Reports from women in the “?ready for change”? group more closely resembled descriptions of the preparation or action stages of change. Characteristics of the preparation stage include a clear intention to make changes and potentially some small attempts at change. According to Brown (1997), the preparation stage is characterized by the determination to change. However, there is less research on behavioral indicators of preparation for change. Often, small steps toward change are followed by more serious action. It is possible for women in pre-contemplation stage to go back to contemplation stage; however, women that are better prepared, are less likely to do so (Anderson, 2003). According to Lafata (2002), action-oriented help can be useful for the women in the preparation stage including group work, advocacy, and self-talk (Lafata, 2002).

Whether or not the three groups of women identified in this study closely match the stages of change, as defined in the transtheorretical model, is perhaps less important than the clear implication that shelter-based interventions may be less effective if a “?one size fits all”? approach is used. In a meta-analysis of 39 studies, Norcross, Krebs, and Prochaska (2011) found that stage of change was a significant predictor of outcome in psychotherapy. Levesque, Driskell, and Prochaska (2008) reported support for a stage of change matched treatment approach for domestic violence offenders.

Violence against women is associated with various psychological functioning and emotional well-being difficulties. Many women need protection from their abuser and initiate contacts with confidential domestic violence shelters. Although shelters provide food, clothing, and protection for many, these women are also in need of avenues for healthy recovery from the negative consequences of violence. In other words, a woman who was subjected to domestic abuse is not destined to a life of misery or emotional problems. Women actually do recover and live fulfilling lives. This was also supported by the findings of this study in that three groups of women were identified, and women in each group appeared to be at different stages of recovery. In particular, the first group of women reported having an active charge of their life, and would like to have their life back. This group of women who are in shelter because of IPV still showed resilience and important signs of recovery from the consequences of violence.

Clinical Implications

Findings from this study can inform the clinical practice. For example, the findings suggest clinicians can inquire about the abusive experience and its effects to assess the stages of change. They can explore recent events, the most severe assaults, and the strategies that have been used to stop the abuse and deal with its consequences. The description of the abuse and its consequences by the victim may vary a lot between different women. The clusters identified in this study, the patterns associated with these clusters, and their alignment with the stages of change suggest there may be common patterns in these differences. Women who are in the precontemplation stage may deny IPV and blame themselves for the events. Those in the contemplative stage, on the other hand, may acknowledge the abuse but believe it is an atypical event. Finally, women in the preparation stage may talk about reevaluating their violent relationships (Haggerty & Goodman, 2002).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of the current study. One limitation of this study is the use of self-report. Collection of data from shelter staff and family members may help identify different mental health needs for these women. It is possible some of the mental health issues are under-identified by some of the participants, such as suicidal ideation and substance abuse, because of shelter policies regarding these issues. Another limitation of this study is the small sample size. Additionally, the findings cannot be generalized beyond shelter populations. Future research could focus on a larger number of women from diverse locations with a wider range of experiences for a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

The data for the study was collected by a single interviewer. This poses a limitation in our ability to check this clinician’s coding against that of other clinicians. In other words, triangulation was not applied to the qualitative data reported in this study. Another limitation of the study is that the checklist used for the study was not validated and standardized with previous research. Since the content of the notes were used as a source for the qualitative analysis and the notes were collected using DAP via only one interviewer, the content of both the checklist and the DAP note depend on the interviewer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these results should not be interpreted as minimizing the impact of IPV on women. On the contrary, our findings emphasize women are not lifelong victims, and they can be helped in various ways and can be empowered to help themselves. One way of facilitating recovery is to offer counseling for these women. In fact, past research indicated therapeutic interventions demonstrate promise in helping victims of domestic violence, particularly in terms of reducing the intensity of PTSD symptoms (Resick & Schnicke, 1992). Many shelters have counselors on staff to offer group counseling focusing on self-esteem, parenting, and decision-making, as well as individual therapy. The findings of this study revealed there are different groups of women who have different mental health needs. For quicker and healthy recovery, it could be helpful to gear treatment more toward the needs of these women, rather than providing a general standardized treatment for all.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jackly Cavern (TTU) for her help on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gunnur Karakurt, Case Western Reserve University, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

Douglas Smith, Texas Tech University, Department of Community, Family, and Addiction Services.

Jason Whiting, Texas Tech University, Department of Community, Family, and Addiction Services.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan H, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG, Stein MB, Sareen J. Mental health correlates of intimate partner violence in marital relationships in a Nationally representative sample of males and females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:1398–1417. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. Evolving out of violence: An application of the transtheoretical model of behavioral change. Research and Theory of Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2003;17:225–240. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.17.3.225.53182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DK, Saunders DG, Yoshihama M, Bybeem DI, Sullivan CM. Long-term trends in depression among women separated from abusive partners. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:807–838. doi: 10.1177/1077801203009007004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda-Florez J, Wade TJ. Childhood and adult victimization as risk factors for major depression. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2001;24:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(01)00072-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2527(01)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett OW, Miller-Perrin CL, Perrin RD. Family violence across the lifespan: An introduction. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson B. Content Analysis in Communication Research. New York: Free Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, RJ, Rivara FP, Carrell D, Thompson RS. Medical and psychological diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi C, Schafer J, Clark C. Intimate partner violence and drinking among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Nelson S, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among white, black and Hispanic couples in the United States. American Journal of Addiction. 2001;10:60–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB, Dalenberg CJ. A conceptual framework for the impact of traumatic experiences. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2000;1:4–28. doi: 10.1177/1524838000001001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CM, Sawhney DK. Coping with domestic violence: Control attributions, dysphoria, and hopelessness. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:219–238. doi: 10.1023/A:1007702626960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MR. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge FL, Anderson LW. Personality profiles of women in multiple abusive relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems, drug use, and male intimate partner violence severity among U.S. couples. Alcoholism and Clinical Experimental Research. 2002;26:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KK, Moffitt TE, Casppi A, Silva PA. Comorbidity between abuse of an adult and DSM III-R mental disorder: Evidence from epidemiological study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:131–133. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann J, Boyle E, Resnick W, Wiederhorn N, Campbell JC. Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21:499–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapkin ML, McCrady BS, Swingle JM, Epstein EE. Exploring bidirectional violence in a clinical sample of female alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism. 2005;66:213–219. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Rezvi-Sheriff MH, Hawton K. Deliberate self-harm in Sri Lanka: an overlooked tragedy in the developing world. British Medical Journal. 1998;317 (7151):133–135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM, Polusny MA, Bechtle AE, Naugle AE. Cumulative trauma: The impact of child and sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:25–35. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D. The extent of substance use problems among women partner abuse survivors residing in a domestic violence shelter. Family and Community Health. 2007;30:S106–S108. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Heise L, Jassen HA, Ellsberg M, Watts C. Domestic Violence and severe psychological disorder: Prevalence and intervention. The Lancet. 2005;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann AL, Mercy JA. Men, women, and murder: Gender-specific differences in rates of fatal violence and victimization. Journal of Trauma. 1992;33:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernic MA, Holt VL, Stoner JA, Wolf ME, Rivara FP. Resolution of depression among victims of intimate partner violence: Is cessation of violence enough? Violence and Victims. 2003;18:115–129. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG. What is violence against women? Defining and measuring the problem. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004:1209–1234. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D, Acierno R. Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:119–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1022891005388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. The World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. Read More: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.256. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Driskell M, Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO. Acceptability of a stage-matched expert system intervention for domestic violence offenders. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:432–445. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren MS, Renck B. It is still so deep-seated, the fear: Psychological stress reactions as consequences of intimate partner violence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2008;15(3):219–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Caetano R, Field CA, Larkin GL. Is there a relationship between victim and partner alcohol use during an intimate partner violence event? Journal of Studies on Alcoholism. 2005;66:407–412. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan T, Cole J, Shannon L, Walker R. Partner Violence and Stalking of Women: Context, Consequences, & Coping. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Moracco KE, Chang JC, Council CL, Dulli LS. Substance abuse issues among women in domestic violence programs. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:985–997. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertin PG, Mohr PB. A follow up study of post traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in Australian victims of domestic violence. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:645–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Sullivan TP, Schmitz M, Weiss RD, Lee CSN. Treatment utilization by women with PTSD and substance dependence. American Journal on Addiction. 2004;13:215–224. doi: 10.1080/10550490490459889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, Krebs PM, Prochaska JO. Stages of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(2):143–154. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive Processing Therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:748–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Green BL. Understanding relationships among trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and health outcomes. In: Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 247–275. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38:619–628. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Smith C. Family patterns of primary prevention of family violence. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Anderson K, Glick J, Shapiro A. Domestic violence, personal control, and gender. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:442–452. doi: 10.2307/353860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CG, Bamett M, Nikunen L, Schultz C, Randolph-Elgin T, Mendez CM. Lifetime prevalences of nine common psychiatric/personality disorders in female domestic abuse survivors. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:645–647. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199710000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver TL, Clum GA. Psychological distress associated with interpersonal violence: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:115–140. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(95)00004-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis, Second Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Chen PH. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002 http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/