Abstract

Two selective inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease nearly double the cure rates for this infection when combined with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin. These drugs, boceprevir and telaprevir, received regulatory approval in 2011 and are the first direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) that selectively target HCV. During 2012, at least 30 additional DAAs were in various stages of clinical development. HCV protease inhibitors, polymerase inhibitors, andNS5A inhibitors (among others) can achieve high cure rates when combined with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin and demonstrate promise when used in combination with one another. Current research is attempting to improve the pharmacokinetics and tolerability of these agents, define the best regimens, and determine treatment strategies that produce the best outcomes. Several DAAs will reach the market simultaneously, and resources will be needed to guide the use of these drugs. We review the clinical pharmacology, trial results, and remaining challenges of DAAs for the treatment of HCV.

Keywords: telaprevir, boceprevir, pharmacology, efficacy, drug interactions

INTRODUCTION

Three percent of the world’s population—approximately 170 million people—are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) (1). The majority will develop chronic infection, which may progress to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (2); these long-term complications generally occur more than 20 years after infection (3). Although rates of new infection have declined in developed countries, infections from prior decades will continue to place a substantial burden on our healthcare system. There are approximately 350,000 HCV-related deaths annually (2), and HCV is the leading indication for liver transplantation (4).

HCV exhibits remarkable within- and between-subject genetic heterogeneity, which is a major obstacle to the development of a universal treatment and a universal preventative vaccine. There are at least six HCV genotypes (5). Within the United States, 75% of isolates are HCV genotype 1a or 1b (6), and the remainder are generally genotype 2 or 3 (6). HCV genotype predicts response to current HCV treatment: Those with HCV genotype 1 or 4 disease are less likely to be cured with interferon- and ribavirin-based treatment than those with genotype 2 or 3 disease (6).

The HCV genome consists of a positive-sense single-stranded RNA approximately 9600 nucleotides long, which encodes three structural proteins (core, E1, and E2), the ion channel protein p7, and six nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A,NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (7). Each of these proteins has a role in HCV entry, infection, replication, or maturation and is therefore a potential antiviral target. Because HCV replicates entirely within the cytoplasm, it does not establish latency and is curable. However, patients can become reinfected, so prevention counseling is an important aspect of antiviral HCV treatment (8).

For more than 10 years, HCV treatment consisted of dual therapy with peginterferon alfa (P), given as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, and ribavirin (R), a guanosine nucleoside analog given orally twice daily (BID). Those with genotype 1 infection received 48 weeks of treatment, and those with genotype 2 or 3 disease received 24 weeks. Fewer than half of those with genotype 1 were cured with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin (PR), and many patients were ineligible or unable to tolerate this treatment. Additional treatment options are desperately needed.

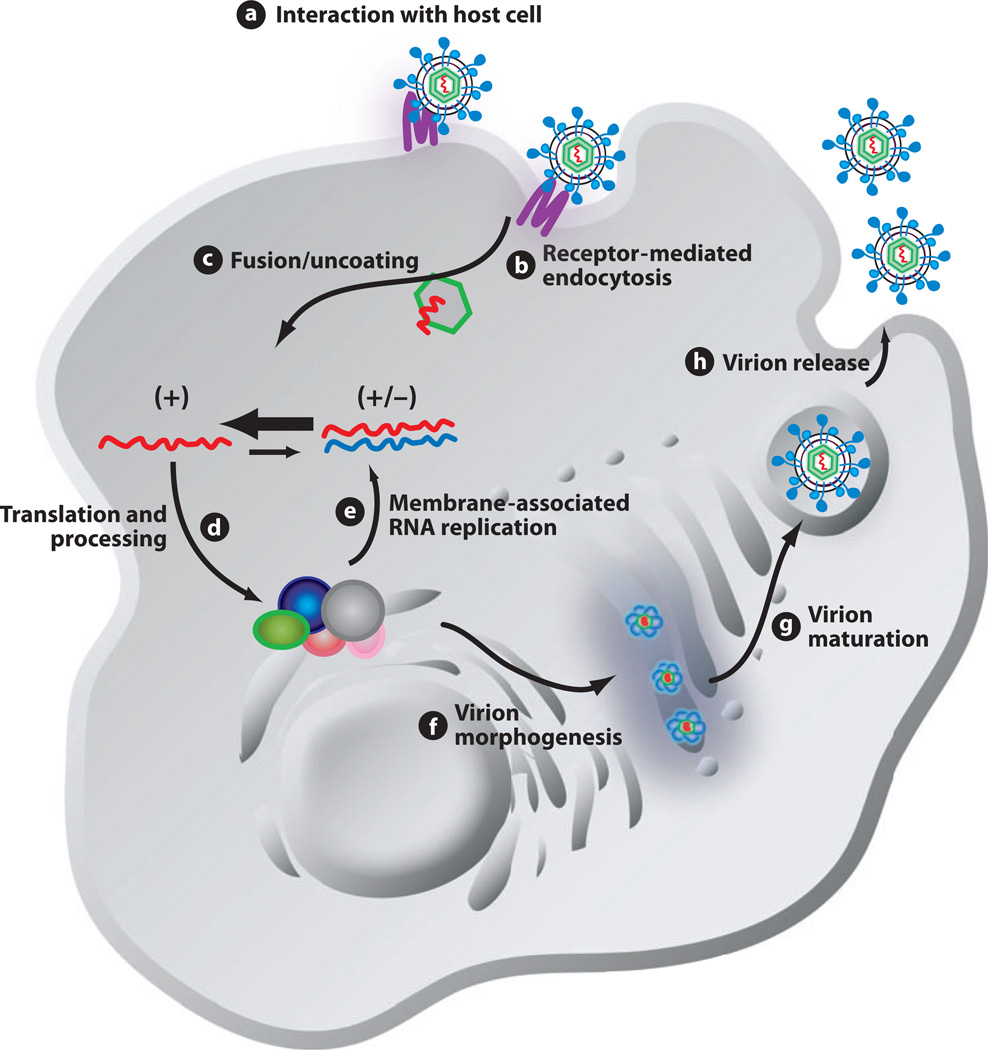

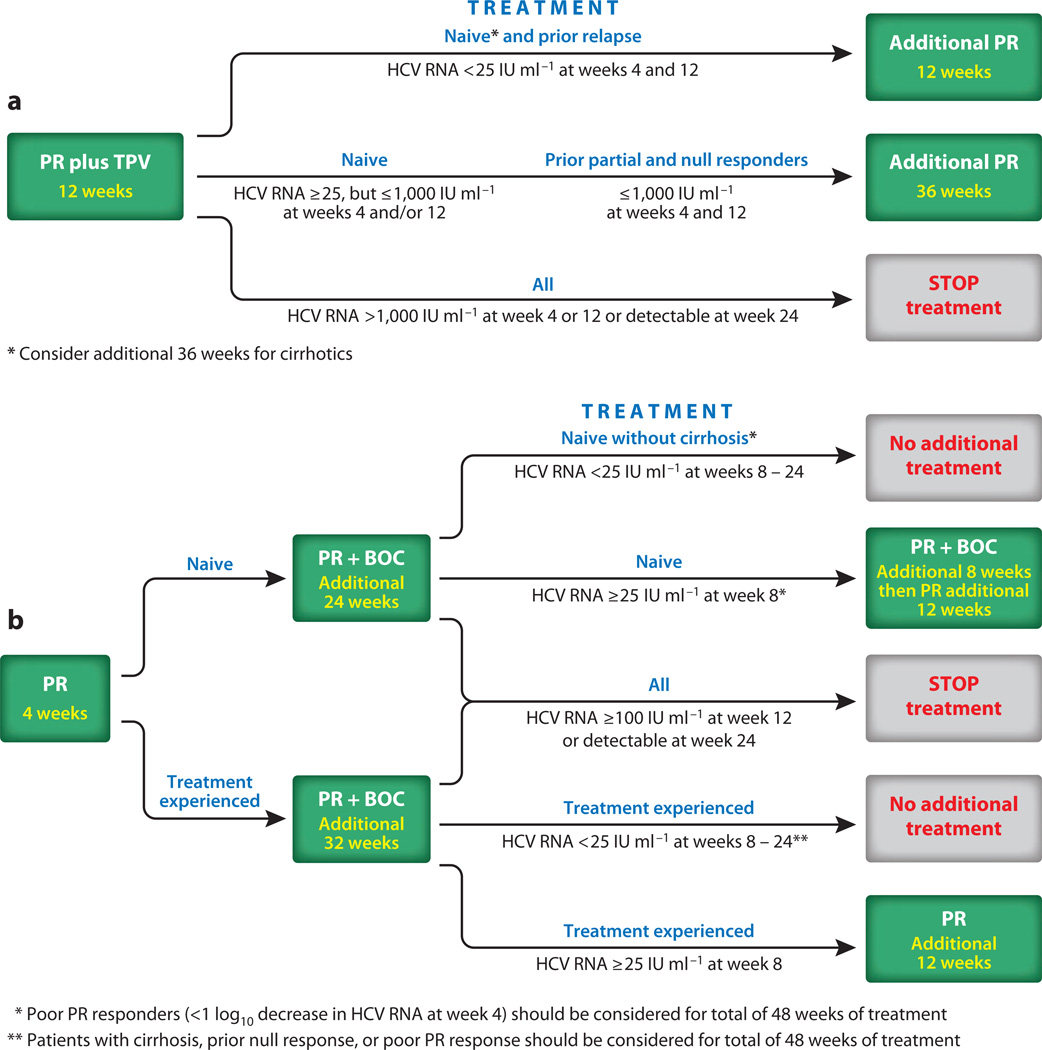

The field of HCV drug discovery and development lay dormant for many years owing to the inability to achieve viral replication in laboratory cell cultures and the absence of a small-animal model for infection (9). Now that these obstacles have been overcome and an understanding of the HCV life cycle has been attained (Figure 1), many direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) are in various stages of clinical development (Table 1). The first DAAs—the HCV protease inhibitors (PIs) telaprevir and boceprevir—received regulatory approval in 2011. For persons with genotype 1 HCV, either telaprevir or boceprevir is added to PR treatment. R doses are based on a person’s weight, and treatment durations are determined by the degree of liver damage upon biopsy, response to prior HCV treatment, and virologic response in the first few weeks on the regimen (Figure 2). This customization has resulted in rather complex treatment algorithms and treatment nomenclature. Novel dosing strategies and trial designs with the investigational DAAs have further increased complexity (10). Table 2 defines many of the terms necessary for understanding HCV treatment and interpreting trial results.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the HCV life cycle. The life cycle of HCV is similar to that of other members of the Flaviviridae family. Extracellular HCV virions interact with receptor molecules at the cell surface (a) and undergo receptor-mediated endocytosis (b) into a low-pH vesicle. Following HCV glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion, the viral RNA is released into the cytoplasm (c). The genomic RNA is translated to generate a single large polyprotein that is processed into the 10 mature HCV proteins in association with a virus-derived ER-like membrane structure termed the membranous web (d). The mature HCV proteins replicate the RNA genome via a minus-strand replicative intermediate to produce progeny RNA. A portion of this newly synthesized RNA is packaged into nucleocapsids and associated with the HCV glycoproteins, leading to budding into the ER (f). Virions follow the cellular secretory pathway (g), and, during this transit, maturation of particles occurs (g). Mature virions are released from the cell, completing the life cycle (h). +, positive-sense genomic RNA; +/−, minus-strand replicative intermediate associated with positive-strand genomic RNA. Reproduced from Reference 11 with permission from the American Society for Microbiology.

Table 1.

Investigational direct-acting antiviral agents in clinical development by class, 2012

| Agent | Company | Development phase |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleos(t)ide polymerase inhibitors | ||

| GS-7977 (PSI-7977) | Gilead | Phase 3 |

| RG7128 (mericitabine) | Roche/Genentech | Phase 2 |

| IDX184 | Idenix | Phase 2 |

| INX189 | Inhibitex/Bristol-Myers Squibb | Phase 2 |

| ALS-2158 | Alios/Vertex | Phase 1 |

| ALS-2200 | Alios/Vertex | Phase 1 |

| Non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitors | ||

| RG7790 (setrobuvir) | Roche/Genentech | Phase 2 |

| BI 207127 | Boehringer Ingelheim | Phase 2 |

| Filibuvir | Pfizer | Phase 2 |

| GS-9190 (tegobuvir) | Gilead | Phase 2 |

| VX-222 | Vertex | Phase 2 |

| ABT-333 | Abbott | Phase 2 |

| BMS-791325 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Phase 2 |

| GS-9669 | Gilead | Phase 1 |

| Protease inhibitors | ||

| BI 201335 | Boehringer Ingelheim | Phase 3 |

| TMC435 | Tibotec | Phase 3 |

| ABT-450 | Abbott | Phase 2 |

| ACH-1625 | Achillion | Phase 2 |

| BMS-650032 (asunaprevir) | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Phase 2 |

| GS-9451 | Gilead | Phase 2 |

| GS-9256 | Gilead | Phase 2 |

| MK-5172 | Merck | Phase 2 |

| RG7227 (danoprevir) | Roche/Genentech | Phase 2 |

| ACH-2684 | Achillion | Phase 1 |

| NS5A inhibitors | ||

| BMS-790052 (daclatasvir) | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Phase 3 |

| ABT-267 | Abbott | Phase 2 |

| GS-5885 | Gilead | Phase 2 |

| GSK2336805 | GlaxoSmithKline | Phase 2 |

| ACH-2928 | Achillion | Phase 1 |

| IDX719 | Idenix | Phase 1 |

| PPI-461 | Presidio | Phase 1 |

| PPI-668 | Presidio | Phase 1 |

Figure 2.

(a) Treatment algorithm for peginterferon and ribavirin (PR) and telaprevir (TPV). All patients receive 12 weeks of TPV with PR, after which time the TPV is discontinued and the duration of continued PR treatment is dictated by virologic response at week 4, prior treatment history, and perhaps presence of cirrhosis upon liver biopsy. (b) Treatment algorithm for PR and boceprevir (BOC). All patients receive a 4-week lead-in period with just PR before BOC is added. BOC is used with PR for 24 and 32 weeks in those who are treatment naive and treatment experienced, respectively. The need for continued PR treatment is then determined by virologic response during the 4-week PR lead-in, virologic response at week 8, prior treatment history, and presence or absence of cirrhosis upon liver biopsy. Other abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; IU, international units.

Table 2.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV): a treatment glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| HCV RNA undetectable | HCV RNA level below the limit of detection of a particular assay |

| Rapid virologic response (RVR) | Undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of direct-acting antiviral agent (DAA) therapy; may allow for shortening of treatment duration |

| Extended RVR (eRVR) | Continued undetectable HCV RNA at week 4 of DAA therapy and beyond |

| End of treatment response (ETR) | HCV RNA negativity at the completion of treatment |

| Early virologic response (EVR) | >2 log10 decline in HCV RNA at week 12 of therapy compared with baseline HCV RNA or HCV RNA negative at treatment week 12 |

| Response-guided therapy (RGT) | Total duration of HCV treatment determined by early HCV RNA response on current regimen |

| Sustained virologic response (SVR) | Undetectable HCV RNA after the cessation of treatment |

| SVR4 | Undetectable HCV RNA 4 weeks after the cessation of treatment |

| SVR12 | Undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after the cessation of treatment |

| SVR24 | Undetectable HCV RNA 24 weeks after the cessation of treatment |

| Null response | <1 log10 maximum HCV RNA reduction any time during treatment |

| Partial response | >1 log10 maximum HCV RNA reduction, but never undetectable |

| Nonresponse | Never achieving undetectable HCV RNA during or at the end of treatment |

| Relapse | Return of a patient’s virus after EVR or ETR |

| Breakthrough | Situation in which the on-treatment presence of detectable HCV RNA on two consecutive serum tests conducted after a previous on-treatment serum test shows an undetectable level of HCV RNA with a real-time quantitative PCR or similarly sensitive test; the HCV RNA level must be at least 100 IU ml−1 on the second positive serum test |

| Viral rebound | Situation in which a patient who has not achieved an undetectable HCV RNA level during the current treatment regimen has an on-treatment 1-log10 increase in HCV RNA level from nadir and an absolute level of at least 1,000 IU ml−1 |

| Lead-in (LI) | Use of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin alone prior to addition of a DAA |

| Genetic barrier to the development of resistance | Number of amino acid substitutions required to confer full resistance to a drug |

| Low genetic barrier | Lack of drug efficacy caused by only one or two amino acid substitutions |

| High genetic barrier | Lack of drug efficacy caused by three or more amino acid substitutions |

The goal of HCV treatment is cure, also known as a sustained virologic response (SVR) (see sidebar, Sustained Virologic Response). In Phase 3 trials, 63–75% of treatment-naive subjects receiving PR plus either boceprevir or telaprevir achieved SVR (12–14). This result represents an approximate doubling of the rates of SVR achieved with PR alone. However, SVR rates in treatment-experienced patients are lower compared with those in treatment-naive patients (15, 16). Although DAA use offers an SVR advantage over the use of PR alone, current DAAs have shortcomings, including frequent dosing (every 7–9 h), a large pill burden (6 or 12 pills per day), poor tolerability, high costs, a food requirement, significant drug interaction potential, and proven efficacy only in HCV genotype 1 patients. Thus, the goals of emerging therapies for HCV include improved pharmacology (lower pill burden, longer half-lives, fewer drug interactions), improved side effect profiles, reduced costs, high genetic barrier to the development of resistance, improved rates of SVR, pangenotypic activity, shorter treatment durations, and, if possible, combination regimens that do not include PR.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION, BARRIER TO RESISTANCE, AND GENOTYPE COVERAGE

Mechanisms of Action

This review covers the NS3/4A protease,NS5Bpolymerase, andNS5Ainhibitors; it does not cover investigational DAAs in other classes (e.g., NS4B, entry, and p7 inhibitors) and host-targeting agents (e.g., cyclophilin inhibitors). The NS3 protease cleaves NS4A-NS4B, NS4B-NS5A, and NS5A-NS5B, which ultimately become the replication complex responsible for formation of viral RNA. Thus, inhibition of NS3/4A is an attractive drug target. The NS3/4A PIs are divided into two groups: (a) linear peptide mimetics with a ketoamide group that covalently, but reversibly, reacts with a serine in the catalytic triad, and (b) noncovalent peptide mimetic inhibitors that have a macrocyclic structure (18).

The NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is also an ideal drug target. This enzyme is essential for HCV replication as it catalyzes the synthesis of the complementary minus-strand RNA and subsequent genomic plus-strand RNA. There are two types of NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors: nucleos(t)ide inhibitors (NIs) and non-nucleoside inhibitors (NNIs). The NIs are active site inhibitors, whereas the NNIs are allosteric inhibitors. The NIs are prodrugs that require intracellular phosphorylation by host enzymes. Nucleoside analogs require three phosphorylation steps utilizing host enzymes, whereas nucleotide analogs already have one phosphate group, so they require one fewer. The triphosphorylated NIs are analogs of endogenous purine or pyrimidine nucleotides, so they compete directly with these endogenous bases for incorporation into replicating virus. When the drug triphosphate instead of the endogenous base is incorporated, replication is halted. Among the NIs in Phase 2 or 3 clinical development, mericitabine (RG7128) is a nucleoside metabolized to both a cytidine and uridine triphosphate (19). GS-7977 is a nucleotide metabolized to the same uridine triphosphate analog as that of RG7128 (20). IDX184 (21) and INX189 (22) are guanosine nucleotide analogs.

The NS5B polymerase has a characteristic right-handed fingers-palm-thumb structure. The NNIs bind noncompetitively to one or more sites outside the polymerase active site, known as palm I, palm II, thumb I, and thumb II. This binding results in a conformational protein change before the elongation complex is formed (23). BI 207127 and MK-3281 bind to the thumb 1 site; filibuvir, GS-9669, VX-759, and VX-222 bind to the thumb II site; and ANA-598 and ABT-333 bind to the palm I site (24).

NS5A encodes a protein that appears essential to the replication machinery of HCV and critical in the assembly of new infectious viral particles (25). However, the specific functions of this protein have not been established. Despite this uncertainty, many promising inhibitors of this protein are in clinical development.

Drug Resistance

On average, almost a trillion HCV particles are produced in each infected individual each day (26). The HCV polymerase enzyme lacks a proofreading function and has relatively poor fidelity (27); therefore, there is a continuous generation of a large variety of spontaneous viral mutations. Untreated persons have HCV genomes that harbor potential resistance mutations. Current data indicate that there are preexisting mutations to NNIs, PIs, and NS5A inhibitors in 22.5%, 7.7%, and 16.2% of patients, respectively (28). The implications of these viral variants for treatment of HCV are under investigation, but they likely contribute to the early selection and emergence of drug resistance during the initial weeks of HCV treatment. The NNIs, PIs, and NS5A inhibitors generally have a low genetic barrier to the development of resistance; that is, only one or two amino acid substitutions result in lack of drug efficacy (23). In contrast, the NIs have a high genetic barrier to resistance; three or more amino acid substitutions are required for full resistance. For the NNIs, PIs, and NS5A inhibitors, there is swift emergence of resistance during monotherapy (29, 30). Resistance also rapidly emerges when dual DAAs, both with low genetic barriers to the development of resistance, are used in combination. As with HIV treatment, HCV treatment will require a combination of agents to optimize viral suppression and protect against the development of resistance.

Genotype Coverage

The amino acid sequence of the NS3 protease domain differs significantly among HCV genotypes, so their antiviral efficacy differs by genotype (23). Telaprevir and boceprevir are active primarily against genotype 1, but the “next generation” of PIs offers broader genotype coverage. For instance, MK-5172 is active against all genotypes, and TMC435 is active against all except genotype 3 (18). The gene sequences encoding the NS5B polymerase are relatively conserved across the different HCV genotypes; this conservation confers pangenotypic antiviral sensitivity. However, because the NS5B allosteric sites are not highly conserved across genotypes, most NNIs have limited activity against genotypes other than genotype 1. The NS5A inhibitors appear to have broad genotypic coverage.

ACTIVITY IN CLINICAL TRIALS

Boceprevir and telaprevir received regulatory approval in the United States in 2011. Four new DAAs are in Phase 3 trials and will likely reach the market within the next 1–2 years. These agents include the PIs BI 201335 and TMC435, the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir (BMS-790052), and the NI GS-7977 (formerly known as PSI-7977). Following are summaries of the clinical trial results with boceprevir, telaprevir, and these four agents when combined with PR.

Protease Inhibitors

Boceprevir and telaprevir are indicated in combination with PR for treatment-naive and treatment-experienced persons with HCV. Figure 2 illustrates the treatment algorithms for boceprevir and telaprevir in the United States.

Boceprevir

Boceprevir is used in combination with PR following a 4-week lead-in period of PR alone. In previously untreated nonblack persons with genotype 1 HCV (n = 938), 68% receiving the 4-week PR lead-in plus an additional 44 weeks of boceprevir and PR achieved SVR, versus 40% who received only PR for 48 weeks (12). A response-guided therapy (RGT) arm was also evaluated. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 8 through 24 qualified for a shortened total treatment duration of 24 weeks of boceprevir plus PR following the 4-week PR lead-in. Sixty-seven percent of subjects in the RGT group achieved SVR. Black patients have lower SVR rates after PR-based therapy compared with nonblacks (see Host Genomics, below). Thus, efficacy of boceprevir plus PR was evaluated in a cohort of black patients (n = 159) (12). SVR was achieved in 53% of black patients receiving the 4-week PR lead-in plus 44 weeks of boceprevir and PR, 42% in the RGT arm, and 23% in the PR control group. These data indicate that the addition of a DAA to PR significantly improves SVR rates over administration of PR alone in blacks. In patients who partially responded or relapsed to prior PR therapy, 66% achieved SVR with a 4-week PR lead-in plus an additional 44 weeks of boceprevir and PR, versus 21% who received 48 weeks of PR (16). RGT was also evaluated in this population. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 8 and 12 received boceprevir plus PR for 32 weeks following the 4-week lead-in. Those with detectable HCV RNA at week 8 but undetectable HCV RNA at week 12 received an additional 12 weeks of PR. Fifty-nine percent of treatment-experienced patients in this RGT group achieved SVR. In a separate study of prior null responders, 40% achieved SVR with boceprevir plus PR (31). Anemia and dysgeusia in these trials were more frequent in patients receiving boceprevir plus PR than in patients receiving PR alone.

Telaprevir

In previously untreated HCV genotype 1 patients (n = 1088), telaprevir was given with PR for 8 or 12 weeks with continued PR dosing determined using RGT (14). Patients with undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 4 and 12 continued PR for an additional 12 weeks (24 weeks total treatment), whereas those with detectable HCV RNA at either time point received an additional 36 weeks of PR (48 weeks total treatment). SVR was achieved in 69% and 75% of patients receiving 8 and 12 weeks of telaprevir, respectively, versus 44% of patients who received PR alone for 48 weeks. Telaprevir has also been studied in prior null and partial responders and relapsers to prior PR therapy (n = 663) (15). Patients were randomized to (a) 12 weeks of telaprevir with PR plus an additional 36 weeks of PR, (b) a 4-week PR lead-in followed by 12 weeks of telaprevir with PR plus an additional 32 weeks of PR, or (c) PR alone for 48 weeks. SVR rates were significantly higher in groups a and b than in group c, with no statistically significant difference in SVR rates between the two telaprevir dosing strategies. SVR rates in relapsers, partial responders, and null responders were approximately 85%, 57%, and 31%, respectively.

BI 201335

In a Phase 2 trial of 429 HCV genotype 1 noncirrhotic naive subjects, patients received BI 201335 once daily (QD) plus PR for either 24 or 48 weeks (based on RGT) (32). Subjects who received BI 201335 240 mg QD had an 83% SVR rate. In 290 subjects with partial response or nonresponse to prior PR treatment, 41% achieved SVR (33). However, unlike in naive subjects, SVR rates were lower and relapse rates were higher among the treatment-experienced subjects in this trial who received RGT. Adverse events that occurred at a frequency 10% greater in those on BI 201335 compared with those on PR alone included nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, jaundice (due to indirect hyperbilirubinemia), rash, and pruritis.

TMC435

In a Phase 2 trial of 386 HCV genotype 1 noncirrhotic naive subjects, patients were randomized to receive TMC435 75 mg or 150 mg QD for 12 or 24 weeks in combination with PR, with continued PR dosing determined by RGT (34). Subjects who received TMC435 75 mg for 12 weeks, 150 mg for 12 weeks, and 150 mg for 24 weeks had SVR rates of 82%, 81%, and 86%, respectively. These SVR rates were significantly higher than the rates of the PR-only group, although the PR-only group had an abnormally high rate of SVR (65%) compared with other controlled studies. In the group receiving 75 mg for 24 weeks, the SVR rate (75%) was not significantly higher than the rate in the PR-only group, owing to a higher percentage of relapse relative to the other TMC435 dosing cohorts. In 467 subjects with prior relapse or partial or null response to PR therapy, TMC435 was administered at 100 mg or 150 mg QD for 12, 24, or 48 weeks with PR (35). All patients received a total of 48 weeks of PR. Response rates were similar between the 150-mg dose groups who received 12, 24, or 48 weeks of TMC435, so data were combined for analysis. Eighty-five percent, 75%, and 51% of prior relapsers, partial responders, and null responders receiving TMC435 150 mg daily achieved SVR relative to 50%, 11%, and 23% of those on PR alone. There were more influenza-like symptoms, pruritis, and asymptomatic hyperbilirubinemia among those receiving TMC435.

NS5A Inhibitor: Daclatasvir (BMS-790052)

In a Phase 2, double-blind study, 48 HCV naive genotype 1 patients were randomized 1:1:1:1 (n = 12 per arm) to receive one of three doses of daclatasvir (3 mg, 10 mg, or 60 mg) or placebo QD in combination with PR for 48 weeks (36). All daclatasvir arms achieved superior SVR12 rates relative to placebo: 83% for 60 mg, 92% for 10 mg, and 42% for 3 mg, versus 25% for those on PR alone. A larger Phase 2b study of two daclatasvir doses (20 mg and 60 mg) with PR in HCV naive genotype 1 (n = 365) and genotype 4 (n = 30) subjects produced the following interim results at week 12 of treatment: Among genotype 1 subjects, 78% and 75% had undetectable HCV RNA (<25 IU ml−1) in the 20-mg and 60-mg daclatasvir doses, respectively, versus 43% in the PR-only group (37); among genotype 4 subjects, 58% (7/12) and 100% (12/12) had undetectable HCV RNA in the 20-mg and 60-mg doses, respectively, versus 50% (3/6) in the PR-only group. Adverse events reported at a higher frequency in those receiving daclatasvir relative to placebo were nausea and dry skin, and the use of filgrastim for neutropenia was higher in the two daclatasvir groups.

RNA Polymerase Inhibitor: GS-7977

In the PROTON trial, 121 HCV noncirrhotic genotype 1 patients were randomized to GS-7977 200 mg (n = 48) or 400 mg (n = 47) QD or placebo (n = 26) for 12 weeks with PR, after which the duration of continued PR was determined by RGT (38). SVR data are not yet available for the placebo group, but 88% and 91% of subjects receiving GS-7977 200 mg and 400 mg, respectively, achieved SVR12. In this same trial, genotype 2/3 patients receiving GS-7977 with PR achieved a 96% SVR rate (39). The ELECTRON trial evaluated an interferon-sparing regimen of GS-7977 plus R alone for 8 weeks in 10 noncirrhotic treatment-naive HCV genotype 2/3 patients. Impressively, all 10 achieved SVR12 (see sidebar, Sustained Virologic Response). Twelve weeks of the combination showed an 80% SVR4 in 25 treatment-experienced genotype 2/3 patients. GS-7977 plus R has also been evaluated in HCV genotype 1 patients. Twenty-five HCV genotype 1 patients receiving the combination for 12 weeks had an 88% SVR4 rate, but this same two-drug combination was ineffective for 10 HCV genotype 1 prior null responders (40). SVR4 data are available for 9 of the 10 prior null responders. Eight of the 9 patients experienced viral relapse after cessation of treatment. One patient, a Caucasian woman with minimal fibrosis and favorable IL28B CC genotype (see Host Genomics, below), achieved SVR4. GS-7977 was well tolerated in these trials, with no clear safety signal and no discontinuations related to the drug.

DIRECT-ACTING ANTIVIRAL AGENT COMBINATIONS

The greatest excitement in the field of HCV is the potential to use combinations of DAAs to shorten treatment durations and maximize the likelihood of SVR. Ideally, these combinations would not include PR because of associated contraindications and toxicities. Several Phase 2 studies have evaluated combinations of DAAs with and without the use of PR, with encouraging results (Table 3). The following summary is limited to combination studies conducted with compounds still in clinical development.

Table 3.

Combination DAA studies

| Reference(s), study name |

n | Drugs, doses, durations | Population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (46) | 21 | Daclatasvir (BMS-790052, NS5A) 60 mg QD + asunaprevir (BMS-650032, PI) 600 mg BID +/− PR × 24 weeks | GT1 prior null responders to PR, no cirrhotics | 100% (n = 10) SVR12 with QUAD, 36% (n = 11) SVR12 with 2 DAAs alone |

| (47) | 10 | Daclatasvir (BMS-790052, NS5A) 60 mg QD + asunaprevir (BMS-650032, PI) 200 mg BID × 24 weeks | GT1b prior null responders to PR | 90% SVR24 |

| (51) | 88 | Daclatasvir (BMS-790052, NS5A) 60 mg QD + GS-7977 (NI) +/− R × 24 weeks | GT1,2,3 noncirrhotic naive | 100% and 91% SVR4 in GT1 and GT2,3, respectively |

| (52) | 140 | GS-5885 (NS5A) 30 mg or 90 mg QD + GS-9451 (PI) 200 mg QD + tegobuvir (NNI) 30 mg BID + R × 12 or 24 weeks | GT1 noncirrhotic naive | Ongoing: 100% and 97% SVR4 in those who have reached this time point after 24 and 12 weeks of treatment, respectively |

| Co-PILOT (50) | 50 | ABT-450/ritonavir (PI) 150 mg QD (naives only) or 250 mg QD + ABT-333 (NNI) 400 mg BID + R × 12 weeks | GT1 noncirrhotic naive and experienced | 94% and 47% SVR12 in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced, respectively |

| INFORM-1 (41) | 88 | Danoprevir (RG7227, PI) + mericitabine (RG7128, NI) × 14 days | GT1 noncirrhotic naive and experienced | Median change in HCV RNA at day 14: −3.7 to −5.2 log10 IU ml−1 |

| INFORM-SVR (42) | 169 | Mericitabine (RG7128, NI) + danoprevir/ritonavir +/– R × 12 or 24 weeks | GT1 noncirrhotic naive | 12-week and non-R-containing arms terminated early; SVR in those on triple therapy × 24 weeks = 41% |

| SOUND-C1 (48) | 32 | BI 201335 (PI) 120 mg QD + BI 207127 (NNI) 400 mg or 600 mg TID + R × 28 days | GT1 noncirrhotic naive | 73% on 400 mg and 100% on 600 mg BI 207127 TID achieved RVR |

| SOUND-C2 (49) | 362 | BI 201335 (PI) 120 mg QD + BI 207127 (NNI) 600 mg BID or TID +/− R × 16–40 weeks | GT1 noncirrhotic naive, compensated cirrhotics allowed | The highest overall SVR rate was 68% with BI 207127 BID + R × 28 weeks; virologic failure and breakthrough more common without R |

| ZENITH (43–45) | 152 | VX-222 (NNI) 100 mg or 400 mg BID + telaprevir 1,125 mg BID +/– R +/– PR × 12 weeks | GT1 noncirrhotic naive | 17% and 31% breakthrough in 2 DAA arms, so trial was prematurely stopped; 83% and 90% SVR12 with 100 mg VX-222 and 400 mg VX-222 QUAD, respectively; 2 DAA + R cohorts ongoing |

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; DAA, direct-acting antiviral agent; GT, genotype; NI, nucleos(t)ide inhibitor; NNI, non-nucleoside inhibitor; P, peginterferon alfa; PI, protease inhibitor; PR, peginterferon alfa and ribavirin; QD, once daily; QUAD, quadruple therapy of VX-222 + TPV + P + R; R, ribavirin; RVR, rapid virologic response; SVR, sustained virologic response; SVR4/12/24, undetectable HCV RNA 4/12/24 weeks after the cessation of treatment; TID, three times daily; TPV, telaprevir.

The first proof-of-concept interferon-sparing DAA combination study (INFORM-1) used mericitabine (RG7128), an NI, and danoprevir (RG7227), an NS3 PI, in genotype 1 noncirrhotic treatment-naive and treatment-experienced subjects (41). The overall study design was complex; 88 subjects received placebo or the two DAAs at different doses for two weeks, then mericitabine and danoprevir were discontinued and patients were treated with PR for 46 weeks. At the highest combination doses tested (mericitabine 1,000 mg BID and danoprevir 900 mg BID), the median change in HCV RNA concentration from baseline to day 14 was −5.1 log10 IU ml−1 in treatment-naive subjects and −4.9 log10 IU ml−1 in prior null responders (n = 16) compared with an increase of 0.1 log10 IU ml−1 in the placebo group. SVR rates with this combination with and without R were also evaluated in treatment-naive subjects (42). One hundred sixty-nine HCV genotype 1 subjects received mericitabine 1,000 mg BID plus danoprevir 100 mg boosted with ritonavir 100 mg BID with and without weight-based R for 12 or 24 weeks based on RGT. The dual-DAA and 12-week mericitabine-plus-danoprevir/ritonavir-plus-R arms were terminated early due to high relapse rates. Forty-one percent of subjects receiving 24 weeks of mericitabine plus danoprevir/ritonavir plus R achieved SVR.

In the ZENITH trial, 152 HCV genotype 1 naive noncirrhotic subjects were randomized to receive 12 weeks of the NNI VX-222 (100 mg or 400 mg BID) plus telaprevir 1,125 mg BID alone (Cohorts A and B), with R (Cohorts E and F), or with PR (“QUAD,” Cohorts C and D). In Cohorts C and D, subjects received RGT: Treatment was discontinued in those with undetectable HCV RNA at weeks 2 and 8, whereas those with detectable HCV RNA at weeks 2 or 8 received an additional 12 weeks of PR (for a total of 24 weeks of treatment). Cohorts A and B were stopped prematurely due to a high rate of virologic breakthrough (17% to 31%) (43). Eighty-three percent of those receiving QUAD therapy with VX-222 100 mg (Cohort C) BID and 90% of those receiving QUAD therapy with VX-222 400 mg (Cohort D) BID achieved SVR12 (44). The majority of patients required 24 weeks of treatment, but of the 38% and 46% of those in Cohorts C and D, respectively, who were eligible to stop after 12 weeks, 82% and 93% achieved SVR12. Limited data are available for Cohorts E and F at this time, but at 12 weeks of treatment with VX-222 400 mg BID plus telaprevir 1,125 mg BID and weight-based R, 83% (38/46 subjects) had undetectable HCV RNA (45). Nine of 11 subjects eligible to stop treatment at week 12 achieved SVR4.

In a separate trial, HCV genotype 1 noncirrhotic prior nonresponders were randomly assigned to receive 24 weeks of treatment with daclatasvir 60 mg QD and the NS3 PI asunaprevir (BMS-650032) 600 mg BID alone (group A, n = 11) or in combination with PR (group B, QUAD, n = 10) (46). All 10 subjects in group B achieved SVR12. Four of 11 patients in group A achieved SVR12. Six patients had viral breakthrough (all with HCV genotype 1a) while receiving therapy, and resistance mutations to both antiviral agents were found in all such cases. One patient had a viral response at the end of treatment but had a relapse. A Japanese study of 10 prior null responders with HCV genotype 1b found 90% SVR24 using just these two DAAs (47), so it now appears that just these two DAAs may be sufficient to cure HCV in genotype 1b. However, for genotype 1a, although it is encouraging that a few of these difficult-to-treat prior nonresponders were able to achieve SVR with just 24 weeks of treatment with two DAAs alone, 36% still falls short of optimal SVR rates. Addition of a third agent (R or another DAA) could increase SVR rates and fulfill the promise of interferon-free treatment.

In the SOUND-C1 study, 32 HCV genotype 1 naive noncirrhotic patients were randomized to the NNI BI 207127 400 mg or 600 mg three times daily (TID) plus the PI BI 201335 120 mg QD plus weight-based R for 28 days (48). At day 29, 73% of those on BI 207127 400 mg and 100% of those on BI 207127 600 mg achieved rapid virologic response. On the basis of these findings, the SOUND-C2 trial enrolled 362 treatment-naive genotype 1 patients to receive BI 201335 120 mg QD (hereafter 1335) plus BI 207127 (hereafter 7127) 600 mg BID or TID in five different treatment arms: (a) 1335 plus 7127 TID and R for 16 weeks, (b) 1335 plus 7127 TID and R for 28 weeks, (c) 1335 plus 7127 TID and R for 40 weeks, (d) 1335 plus 7127 BID and R for 28 weeks, and (e) 1335 plus 7127 TID for 28 weeks (no R). The highest overall SVR rate was 68% in group d, and rates of virologic failure and breakthrough were more common with dual-DAA treatment (49).

The ritonavir-boosted NS3 PI ABT-450 plus the NNI ABT-333 400 mg BID plus R has been studied in 33 treatment-naive and 17 treatment-experienced (prior null responders or partial responders to PR) HCV genotype 1 noncirrhotic subjects (50). All subjects received 12 weeks of treatment. Two QD doses of ABT-450 were tested in the treatment-naive subjects (150 mg and 250 mg), but treatment-experienced subjects received 250 mg daily. Ninety-four percent and 47% of treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, respectively, achieved SVR12.

Daclatasvir plus GS-7977 with and without R for 24 weeks has been evaluated in 88 treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients with HCV genotypes 1, 2, and 3 (51). One hundred percent of the genotype 1 patients and 91% of the genotype 2/3 patients achieved SVR4 regardless of R use.

The quadruple interferon-free combination of GS-5885 (NS5A inhibitor), GS-9451 (PI), tegobuvir (NNI), and R is being evaluated in 140 treatment-naive, noncirrhotic HCV genotype 1 patients (52). Two GS-5885 doses, 30 mg or 90 mg QD, are being tested, and patients on the 90-mg daily dose are randomized to either 12 or 24 weeks of treatment (subjects on 30 mg receive 24 weeks). Seventeen patients on GS-5885 30 mg daily and 21 patients on 90mg daily have completed 24 weeks of treatment, and all of these subjects achieved SVR4. Thirty-two subjects who were randomized to GS-5885 90-mg daily dose completed 12 weeks of treatment, and 97% achieved SVR4.

Several themes emerge from these trials. First, several dual-DAA regimens appear insufficient to produce SVR in most patients. However, GS-7977 plus R proved highly effective in a small number of genotype 2/3 patients; daclatasvir and GS-7977 with and without R achieved high rates of SVR4 in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced subjects; and daclatasvir and asunaprevir proved highly effective in a small number of genotype 1b nonresponders and somewhat effective (36%) in a small number of mostly genotype 1a nonresponders. QUAD therapy with two DAAs plus PR achieved SVR rates approaching 100%. Data are limited on the combination of two DAAs plus R without P. These regimens appear to provide SVR rates that are intermediate between dual and QUAD therapy, but more potent DAA combinations provide higher SVR rates. These results appear to support pharmacodynamic models (53) suggesting that four active drugs are needed to cure most genotype 1 infections, although combinations of two to three highly active DAAs with a high barrier to the development of resistance may also succeed in some circumstances.

DIRECT-ACTING ANTIVIRAL AGENT DOSING, TOLERABILITY, AND INTERACTION POTENTIAL

Dosing Regimen

Whether added to PR or administered as part of an interferon-sparing, all-oral DAA-combination regimen, the vast majority of DAAs under clinical investigation offer the advantage of less frequent daily dosing than required by boceprevir or telaprevir. Boceprevir and telaprevir require dosing every 8 h with food, which may compromise adherence. The four DAAs in Phase 3 clinical development—TMC435, BI 201335, GS-7977, and daclatasvir—are dosed QD. Table 4 highlights dosing for approved and investigational (Phase 2+) DAAs. At least two DAAs in Phase 2 trials, ABT-450 and danoprevir, are being administered with the pharmacokinetic enhancer or “boosting” agent ritonavir, which inhibits their metabolism by cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) and decreases their dosing requirements and dosing frequency. This boosting strategy has been exploited for many years with HIV PIs, although there are questions about possible resistance to HIV PIs in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients who are not taking antiretroviral medications.

Table 4.

Pharmacologic properties of approved and investigational (Phase 2+) HCV DAAs

| Agent | Number of doses per day |

Toxicity profile | Pharmacologic profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protease inhibitor | |||

| Boceprevir | 3 | Anemia, dysgeusia, gastrointestinal symptoms | CYP3A substrate and inhibitor, P-gp substrate |

| Telaprevir | 3 | Rash, anemia, gastrointestinal symptoms and anorectal discomfort | CYP3A and P-gp substrate and inhibitor |

| BI 201335 | 1 | Asymptomatic unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, rash, gastrointestinal symptoms | CYP3A substrate, moderate inhibitor of hepatic and intestinal CYP3A |

| TMC435 | 1 | Asymptomatic unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia | CYP3A substrate, mild inhibitor of CYP1A2 and intestinal CYP3A (57) |

| ABT-450 | 1, ritonavir-boosted | Hyperbilirubinemia (50) | CYP3A substrate (76) |

| ACH-1625 | 1 | Not yet established | CYP3A substrate (77) |

| BMS-650032 (asunaprevir) | 2 | Transaminase elevations (78) | Moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6, weak inducer of CYP4A4, and weak inhibitor of P-gp (79) |

| GS-9451 | 1 | Not yet established | No data |

| GS-9256 | 2 | Not yet established | No data |

| MK-5172 | 1 | Not yet established | No data |

| RG7227 (danoprevir) | 2, ritonavir-boosted | Nausea, diarrhea, neutropenia, ALT increases (reduced with use of a lower danoprevir dose with ritonavir) | A study with midazolam (CYP3A probe) and warfarin (CYP2C9 probe) showed that danoprevir did not change the effect of ritonavir on these probes (midazolam increased, warfarin decreased) (80) |

| Nucleos(t)ide RNA polymerase inhibitor | |||

| GS-7977 | 1 | No hallmark toxicity identified to date (81) | Uridine analog, renally excreted (66) |

| RG7128 (mericitabine) | 2 | Headache, dry mouth, nausea, upper respiratory tract infection | Cytidine and uridine analog (19), renally excreted (82) |

| IDX184 | 1 | Not yet established | Guanosine analog (21) |

| INX189 | 1 | Not yet established | Guanosine analog (22) |

| Non-nucleoside RNA polymerase inhibitor | |||

| RG7790 (setrobuvir) | 2 | Rash | No data |

| BI 207127 | 2 | Not yet established | No data |

| Filibuvir | 2 | Not yet established | CYP3A substrate, weak inducer and inhibitor (83) |

| GS-9190 (tegobuvir) | 2 | Pancytopenia (84) | Minimal metabolism by CYP1A2, no evidence of CYP induction or inhibition (85) |

| VX-222 | 2 | Not yet established | No data |

| ABT-333 | 2 | Not yet established | In vitro, CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and CYP2D6 contribute approximately 60%, 30%, and 10% to ABT-333 metabolism, respectively (86) |

| BMS-791325 | 2 | Headache, nausea, hyperbilirubinemia (87) | No data |

| NS5A inhibitor | |||

| BMS-790052 (daclatasvir) | 1 | Nausea, dry skin, neutropenia (36, 37) | Substrate and inhibitor of P-gp and substrate of CYP3A4 (63) |

| ABT-267 | 1 | Not yet established (88) | No data |

| GS-5885 | 1 | Not yet established | No data |

| GSK2336805 | 1 | Not yet established | No data |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CYP, cytochrome P450; DAA, direct-acting antiviral agent; HCV, hepatitis C virus; P-gp, P-glycoprotein.

Tolerability

Another advantage of the next generation of DAAs may be improved tolerability. Telaprevir and boceprevir cause gastrointestinal symptoms and significant anemia, which often require therapy. Boceprevir also causes a bitter or metallic taste, whereas telaprevir causes a rash and anorectal discomfort. Management of the side effects associated with these therapies (in addition to those associated with PR) requires provider vigilance and consumes resources. With the exception of BI 201335, which also causes rash and gastrointestinal side effects, the other DAAs in Phase 3 appear to cause fewer adverse effects than those seen with telaprevir and boceprevir. They are not devoid of adverse effects, however. For example, both BI 201335 and TMC435 cause mild and reversible total bilirubin elevations because these agents alter bilirubin transport (54) and/or metabolism (55). The tolerability profiles of approved and investigational (Phase 2+) DAAs are summarized in Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic Drug Interactions

Drug interactions are a critical consideration in the treatment of chronic HCV. Interactions that increase concentrations of DAAs can increase the likelihood of side effects. In contrast, interactions that decrease concentrations of DAAs can lead to the development of viral resistance and decrease the likelihood for SVR. HCV agents can also affect the concentrations of concomitant medications. As with side effects, identification and management of potential drug interactions also require provider vigilance and consume resources. Telaprevir and boceprevir are substrates and inhibitors of CYP3A and the drug transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp). Many drugs can affect the pharmacokinetics of telaprevir and boceprevir, and, conversely, many drugs are affected by telaprevir and boceprevir (56).

An up-to-date online resource for drug interactions with approved agents is http://www.hep-druginteractions.org. Publicly available information on the pharmacology and interaction potential of investigational DAAs is widely varied. Table 4 summarizes the pharmacologic profiles of the approved and investigational (Phase 2+) DAAs. A lack of information on the routes of metabolism and drug interaction potential for some agents does not equate to a lack of interactions.

Of the investigational PIs, TMC435 is a CYP3A substrate that is susceptible to reductions in concentrations from potent CYP3A inducers such as efavirenz and rifampin and increases in concentrations from potent CYP3A inhibitors such as ritonavir. TMC435 also appears to be a mild inhibitor of CYP1A2, as evidenced by an increase in caffeine concentrations, and is a mild inhibitor of intestinal CYP3A, as evidenced by increased midazolam concentrations with administration of oral (but not intravenous) midazolam (57). TMC435 does not significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of the antiretroviral drugs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, rilpivirine, or raltegravir (58). These agents plus lamivudine, emtricitabine, abacavir, maraviroc, and enfuvirtide were allowed in the HIV/HCV coinfection trial with this DAA. Methadone pharmacokinetics were unaffected by TMC435 (59). Escitalopram pharmacokinetics were also unaffected by TMC435, but the TMC435 area under the curve (AUC) was decreased by approximately 25% (60). The effects of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of TMC435 have also been determined: In eight volunteers with Child Pugh B cirrhosis, TMC435 pharmacokinetics were higher than those observed in 8 volunteers without hepatic impairment [AUC and maximum concentration (Cmax) increased 2.62- and 1.76-fold, respectively], but similar to those observed in persons with Child Pugh A cirrhosis (61).

Daclatasvir is a substrate and inhibitor of P-gp and a substrate of CYP3A4. Healthy-volunteer drug interaction studies have been conducted with daclatasvir and the antiretroviral agents tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, efavirenz, and atazanavir/ritonavir (62). Investigators reduced the daclatasvir dose to 20mg when administering it with atazanavir/ritonavir, but the daclatasvir AUC was 30% lower with this reduced dose versus a 60-mg daily dose. With efavirenz, investigators increased the daclatasvir dose to 120 mg, but the daclatasvir AUC was 37% higher with this increased dose versus a 60-mg daily dose. Recommendations of daclatasvir dosing with these agents reflect projections that should provide AUCs similar to those seen with 60 mg daily when combined with efavirenz (90 mg QD) and atazanavir/ritonavir (30 mg QD). Daclatasvir does not alter the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and norgestimate (63), and dose adjustments of daclatasvir do not appear necessary in the setting of hepatic impairment (64). Six subjects, each of whom had Child Pugh A, B, or C cirrhosis, and 12 volunteers without hepatic impairment received a single 30-mg daclatasvir dose. Relative to those without hepatic impairment, total daclatasvir plasma AUC and Cmax were lower in those with hepatic impairment, but unbound drug exposures were similar.

An advantage of existing NIs is that they are not substrates, inhibitors, or inducers of CYP enzymes. They may still be susceptible to drug interactions, but their interaction potential is greatly reduced because they are mainly renally excreted. Membrane transporter interactions may still be a consideration, and interactions that may affect intracellular nucleoside phosphorylation should also be considered. For instance, if two NIs are to be used in combination, studies should first be undertaken to determine if phosphorylation of both agents combined is similar to phosphorylation of each agent administered alone. This should also apply when NIs are combined with ribavirin. Although the antiviral mechanism of action of ribavirin is not completely understood, ribavirin is a nucleoside analog that undergoes phosphorylation by host enzymes, and it may be susceptible to intracellular phosphorylation interactions with other NIs. Understanding the intracellular pharmacology of the NI is also critical to determine appropriate dosing. Dosing these agents on the basis of their plasma (i.e., prodrug) pharmacokinetics could result in overdosing.

GS-7977 is a uridine analog. A healthy-volunteer drug interaction study performed with methadone indicated no clinically relevant effects on methadone or plasma concentrations of GS-7977 (65). A study to evaluate the potential for interactions with the antiretroviral agents efavirenz, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, atazanavir/ritonavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in a small number of HIV/HCV-coinfected persons is under way (NCT01565889). GS-7977’s potential for intracellular interactions with ribavirin or other NIs has not been determined. Dose adjustments of GS-7977 are necessary for renal impairment (66).

REMAINING QUESTIONS

Regulatory approval of the first DAAs, telaprevir and boceprevir, was a major milestone in the treatment of chronic HCV. These agents have increased cure rates, but there is still considerable room for improvement. With more than 30 DAAs in various stages of clinical development, the promise of curing most—if not all—persons with chronic HCV over the coming decades seems possible. Research to meet this challenge is occurring at a swift pace, and, as a result, there are many remaining questions about HCV treatment in the DAA era.

Host Genomics

A genetic polymorphism near the IL28B gene, which encodes for interferon-λ3, is associated with favorable response to interferon-based HCV treatment (67). The favorable IL28B CC genotype is more common in European than in African populations. This genetic polymorphism accounts for approximately half of the lower response rates to PR therapy observed in African-Americans relative to persons of European ancestry (67). Although IL28B genotype was the most important pretreatment predictor of SVR in those receiving PR, response to triple therapy with PR and a PI is only partially predicted by IL28B genotype (34, 68–70). IL28B genetics is unlikely to predict SVR in the face of more potent combination regimens. Thus, a remaining question for the field is how, when, and if IL28B testing should be used in practice.

Selection of Regimens

If several DAAs reach the market simultaneously, there will be questions about how best to combine these agents, how many agents are needed in a particular regimen, and how long treatment should be. The DAA-combination studies performed to date suggest that several drugs are needed for most but not all patients. Ribavirin has been used for decades in the treatment of HCV without a complete understanding of how it exerts its pharmacologic effects. Despite this lack of knowledge, R is still of benefit in HCV treatment even in the face of DAAs. In clinical trials, treatment arms that include R with DAAs consistently have higher rates of SVR. However, R has a major dose-limiting toxicity: hemolytic anemia. There is an increased frequency of hemolytic anemia in persons on PR plus telaprevir or boceprevir relative to those on PR alone. Thus, several important questions about the role of R in the DAA era include: (a) how does R exert its toxic and antiviral effects, (b) can we use a lower R dose in the setting of DAAs, and (c) is there a combination of DAAs that performs as well as a ribavirin-based DAA regimen?

The Cost of Cure

Boceprevir and telaprevir currently cost US$1,100 and US$4,100, respectively, per week of treatment (71). When boceprevir and telaprevir are combined with PR and customized to degree of liver damage, response to prior HCV treatment, and virologic response in the first few weeks on the regimen, drug costs can total US$53,000–$95,000 for curative therapy. These costs may prove prohibitive for some patients or groups and create a financial challenge for researchers requiring a telaprevir- or boceprevir-based standard-of-care arm. However, studies have suggested the cost-effectiveness of this treatment (71, 72).

DAA Therapy Failures

Patients may fail to complete DAA therapy because of unwanted adverse effects, or they may fail to respond to treatment due to nonadherence or nonresponse. The impact of prior DAA treatment failure on the success of future DAA regimens is unknown. Unlike HIV, which has long-lived “reservoirs” that harbor viral mutants and may limit the efficacy of future agents, HCV replicates exclusively in the cytoplasm, does not integrate with human chromosomes, and therefore does not appear to persist in a latent form. Available data indicate that resistance mutations do not persist and that the virus may return to its baseline state within months or years of the discontinuation of HCV treatment (73, 74). Only clinical trials (e.g., retreating prior DAA failures) will determine the impact of treatment-emergent resistance mutations on the success of future therapies.

Special Patient Populations

DAAs are initially studied in noncirrhotic, mostly healthy, primarily treatment-naive persons with HCV. This creates uncertainties in how best to utilize DAAs in persons with prior treatment experience, those with advanced liver disease (including in the pretransplant setting), those who have received a liver transplant, those coinfected with HIV, pregnant women, and children. Studies are urgently needed in the patient populations in greatest need to ensure safe and appropriate use of these new and potentially life-saving agents.

SUSTAINED VIROLOGIC RESPONSE.

Sustained virologic response (SVR) has historically been defined as undetectable hepatitis C virus RNA 24 weeks after the cessation of peginterferon and ribavirin treatment (SVR24), but some trials with direct-acting antiviral agents have employed earlier assessments of SVR including 4 and 12 weeks after the cessation of treatment (SVR4 and SVR12, respectively). The US Food and Drug Administration now considers SVR12 to be the primary endpoint (17).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.J.K. acknowledges financial support from the National Institutes of Health (K23 DK82321).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

J.J.K. has received research support from Vertex and Merck Sharp & Dohme. C.F. has received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and consults for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Vertex, and ViiV Healthcare.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl. 1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Org. (WHO) Hepatitis C fact sheet. Media Centre. 2012 Jul; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/index.html.

- 3.Freeman AJ, Dore GJ, Law MG, Thorpe M, Von Overbeck J, et al. Estimating progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;34:809–816. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinnadurai R, Velazquez V, Grakoui A. Hepatic transplant and HCV: a new playground for an old virus. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:298–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, et al. Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J. Gen. Virol. 1993;74(Part 11):2391–2399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zein NN, Rakela J, Krawitt EL, Reddy KR, Tominaga T, Persing DH. Hepatitis C virus genotypes in the United States: epidemiology, pathogenicity, and response to interferon therapy. Collaborative Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125:634–639. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang H, Grise H. Cellular and molecular biology of HCV infection and hepatitis. Clin. Sci. 2009;117:49–65. doi: 10.1042/CS20080631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambers FA, Prins M, Thomas X, Molenkamp R, Kwa D, et al. Alarming incidence of hepatitis C virus re-infection after treatment of sexually acquired acute hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected MSM. AIDS. 2011;25:F21–F27. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834bac44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice CM. New insights into HCV replication: potential antiviral targets. Top. Antivir. Med. 2011;19:117–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433–1444. doi: 10.1002/hep.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tellinghuisen TL, Evans MJ, von Hahn T, You S, Rice CM. Studying hepatitis C virus: making the best of a bad virus. J. Virol. 2007;81:8853–8867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00753-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, Nelson DR, Sulkowski MS, et al. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:1014–1024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2405–2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arya V. FDA perspectives on hepatitis C drug development: trial design and clinical pharmacology considerations; Presented at Annu. Meet. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharmacol.; Sept. 23–25; San Diego, CA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciesek S, von Hahn T, Manns MP. Second-wave protease inhibitors: choosing an heir. Clin. Liver Dis. 2011;15:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma H, Jiang WR, Robledo N, Leveque V, Ali S, et al. Characterization of the metabolic activation of hepatitis C virus nucleoside inhibitorβ-d-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine (PSI-6130) and identification of a novel active 5′-triphosphate species. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29812–29820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofia MJ, Bao D, Chang W, Du J, Nagarathnam D, et al. Discovery of a β-d-2′-deoxy-2′-α-fluoro-2′-β-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:7202–7218. doi: 10.1021/jm100863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou XJ, Pietropaolo K, Chen J, Khan S, Sullivan-Bolyai J, Mayers D. Safety and pharmacokinetics of IDX184, a liver-targeted nucleotide polymerase inhibitor of hepatitis C virus, in healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:76–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01101-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolykhalov A, Bleiman B, Gorovits E, Madela K, Muhammed J, et al. Analysis of enzymes involved in activation of the C6-modified-2′-C-methyl guanosine 5′-monophosphate based prodrugs; Presented at HepDART; Dec. 4–8; Koloa, Hawaii. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asselah T, Marcellin P. Direct acting antivirals for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: one pill a day for tomorrow. Liver Int. 2012;32(Suppl. 1):88–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legrand-Abravanel F, Nicot F, Izopet J. New NS5B polymerase inhibitors for hepatitis C. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;19:963–975. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.500285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gish RG, Meanwell NA. The NS5A replication complex inhibitors: difference makers? Clin. Liver Dis. 2011;15:627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown NA. Progress towards improving antiviral therapy for hepatitis C with hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitors. Part I: Nucleoside analogues. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;18:709–725. doi: 10.1517/13543780902854194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margeridon S, Le Pogam S, Liu TF, Hanczaruk B, Simen BB, et al. No detection of variants bearing NS5BS282T mericitabine (MCB) resistance mutation in DAA treatment-naive HCV genotype 1-infected patients using ultra-deep pyrosequencing (UDPS); Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 6–9; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarrazin C, Kieffer TL, Bartels D, Hanzelka B, Muh U, et al. Dynamic hepatitis C virus genotypic and phenotypic changes in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1767–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fridell RA, Wang C, Sun JH, O’Boyle DR, 2nd, Nower P, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of variants resistant to hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor BMS-790052 in humans: in vitro and in vivo correlations. Hepatology. 2011;54:1924–1935. doi: 10.1002/hep.24594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bronowicki JP, Davis M, Flamm SL. Sustained virologic response (SVR) in prior peginterferon/ribavirin (PR) treatment failures after retreatment with boceprevir (BOC) + PR: PROVIDE study interim results; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sulkowski MS, Ceasu E, Asselah T, Caruntu FA, Lalezari J, et al. SILEN-C1: sustained virologic response (SVR) and safety of BI201335 combined with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin (P/R) in treatment-naive patients with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sulkowski M, Bourliere M, Bronowicki JP, Streinu-Cercel A, Preotescu L, et al. SILEN-C2: sustained virologic response (SVR) and safety of BI201335 combined with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin (P/R) in chronic HCV genotype-1 patients with non-response to P/R; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried MW, Buti M, Dore GJ, Flisiak R, Ferenci P, et al. TMC435 in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1 patients: final analysis of the PILLAR phase IIb study; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeuzem S, Berg T, Gane E, Ferenci P, Foster GR, et al. ASPIRE: TMC435 plus PegIFN/RBV significantly improved SVR24 rates over PegIFN/RBV alone in patients with genotype 1 HCV who failed previous PegIFN/RBV therapy; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pol S, Ghalib R, Rustgi V, Martorell C, Everson GT, et al. First report of SVR12 for a NS5A replication complex inhibitor, BMS-790052 in combination with PegIFNα-2a and RBV: phase IIA trial in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1 subjects; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hezode C, Hirschfield G, Ghesquiere W, Siever W, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. BMS-790052, a NS5A replication complex inhibitor, combined with peginterferon-alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1 or 4 patients: phase 2b AI444010 study interim week 12 results; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawitz E, Lalezari J, Hassanein T, Kowdley KV, Poordad F, et al. BMS-790052, a NS5A replication complex inhibitor, combined with peginterferon-alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1 or 4 patients: phase 2b AI444010 study interim week 12 results; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gane E, Stedman C, Hyland RH, Sorensen RD, Symonds WT, et al. PSI-7977: ELECTRON interferon is not required for sustained virologic response in treatment-naive patients with HCV GT2 or GT3; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Assoc. Study Liver Dis; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gane E, Stedman C, Hyland RH, Sorensen R, Symonds W, et al. Once daily GS-7977 plus ribavirin in HCV genotypes 1–3: the ELECTRON trial; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, Angus PW, Ritchie B, et al. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gane E, Pockros P, Zeuzem S, Marcellin P, Shikhman A, et al. Interferon-free treatment with a combination of mericitabine and danoprevir/R with or without ribavirin in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1-infected patients; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Bisceglie AM, Nelson DR, Gane E. VX-222 with TVR alone or in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C: ZENITH study interim results; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson DR, Gane E, Jacobson IM, Di Bisceglie AM, Alves K, et al. VX-222/telaprevir in combination with peginterferon-alfa-2a and ribavirin in treatment-naive genotype 1 HCV patients treated for 12 weeks: ZENITH study, SVR12 interim analysis; Presented at 62nd Annu. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vertex. Vertex announces 12-week on-treatment data and SVR4 from phase 2 study of interferon-free (all-oral) treatment regimen of INCIVEK®, VX-222 and ribavirin in people with genotype 1 hepatitis C. Vertex Pharm. 2012 Feb. http://investors.vrtx.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=650944. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lok AS, Gardiner DF, Lawitz E, Martorell C, Everson GT, et al. Preliminary study of two antiviral agents for hepatitis C genotype 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:216–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, et al. Dual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, BMS-790052, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, BMS-650032, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null responders. Hepatology. 2011;55:742–748. doi: 10.1002/hep.24724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeuzem S, Asselah T, Angus P, Zarski JP, Larrey D, et al. Efficacy of the protease inhibitor BI 201335, polymerase inhibitor BI 207127, and ribavirin in patients with chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2047–2055. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeuzem S, Soriano V, Asselah T, Bronowicki JP, Lohse A, et al. SVR4 and SVR12 with an interferon-free regimen of BI 201335 and BI 207127, +/− ribavirin, in treatment-naive patients with chronic genotype-1 HCV infection: interim results of SOUND-C2; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poordad F, Lawitz E, Kowdley KV, Everson GT, Freilich B, et al. A 12-week interferon-free regimen of ABT-450/r + ABT-333 + ribavirin achieved SVR12 in more than 90% of treatment-naive HCV genotype-1-infected subjects and 47% of previous non-responders; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sulkowski M, Gardiner DF, Lawitz E, Hinestrosa F, Nelson DR, et al. Potent viral suppression with the all-oral combination of daclatasvir (NS5A inhibitor) and GS-7977 (NS5B Inhibitor), +/− ribavirin, in treatment-naive patients with chronic HCV GT1, 2, or 3; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sulkowski M, Rodriguez-Torres M, Lawitz E, Shiffman ML, Pol S, et al. High sustained virologic response rate in treatment-naive HCV genotype 1a and 1b patients treated for 12 weeks with an interferon-free all-oral quad regimen: interim results; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rong L, Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS. Rapid emergence of protease inhibitor resistance in hepatitis C virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:30ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huisman MT, Snoeys J, Monbaliu J, Martens M, Sekar V, Raoof A. In vitro studies investigating the mechanism of interaction between TMC435 and hepatic transporters; Presented at 61st Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Oct. 30–Nov. 3; Boston, MA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sane R, Podila L, Mathur A, Mease K, Taub M, et al. Mechanisms of isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia induced by the HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor BI 201335; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 20; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiser JJ, Burton JR, Anderson PL, Everson GT. Review and management of drug interactions with boceprevir and telaprevir. Hepatology. 2012;55:1620–1628. doi: 10.1002/hep.25653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sekar V, Verloes R, Meyvisch P, Spittaels K, Akuma SH, De Smedt G. TMC435 and drug interactions: evaluation of metabolic interactions for TMC435 via cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in healthy volunteers; Presented at 45th Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 14–18; Vienna, Austria. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ouwerkerk-Mahadevan S, Sekar V, Peeters M, Beumont-Mauviel M. The pharmacokinetic interactions of HCV protease inhibitor TMC435 with rilpivirine, tenofovir, efavirenz or raltegravir in healthy volunteers; Presented at 19th Conf. Retrovir. Oppor. Infect.; March 5–8; Seattle, WA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beumont-Mauviel M, De Smedt G, Peeters M, Akuma SH, Sekar V. The pharmacokinetic interaction between the investigational NS3-4A HCV protease inhibitor TMC435 and methadone; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beumont-Mauviel M, Simion A, De Smedt G, Spittaels K, Peeters M, Sekar V. The pharmacokinetic interaction between the investigational HCV NS3/4 A protease inhibitor TMC435 and escitalopram; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sekar V, Simion A, Peeters M, Spittaels K, Lawitz E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of TMC435 in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bifano M, Hwang C, Oosterhuis B, Hartstra J, Tiessen RG, et al. Assessment of HIV antiretroviral drug interactions with the HCV NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir demonstrates a PK profile which supports coadministration with tenofovir, efavirez, and atazanavir/r; Presented at 19th Conf. Retrovir. Oppor. Infect.; March 5–8; Seattle, WA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bifano M, Sevinsky H, Persson A, Hwang C, Kandoussi H, et al. Daclatasvir has no clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol and norgestimate in healthy female subjects; Presented at Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 5–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bifano M, Sevinsky H, Persson A, Chung E, Wind-Rotolo M, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of daclatasvir in subjects with hepatic impairment compared with healthy subjects; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denning J, Cornpropst M, Clemons D, Fang L, Sale M, et al. Lack of effect of the nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor PSI-7977 on methadone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cornpropst M, Denning J, Clemons D, Marbury T, Alcorn H, et al. The effect of renal impairment and end stage renal disease on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of GS-7977; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poordad F, Bronowicki JP, Gordon SC, Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, et al. IL-28B polymorphism predicts virologic response in patients with hepatitis C genotype 1 treated with boceprevir combination therapy; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sulkowski M, Asselah T, Ferenci P, Stern JO, Kukolj G, et al. Treatment with the second generation HCV protease inhibitor BI 201335 results in high and consistent SVR rates—results from SILEN-C1 in treatment-naive patients across different baseline factors; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobson IM, Catlett I, Marcellin P. Telaprevir substantially improved SVR rates across all IL-28B genotypes in the ADVANCE trial; Presented at 46th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; March 30–April 3; Berlin, Ger.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu S, Cipriano LE, Holodniy M, Owens DK, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. New protease inhibitors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:279–290. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cammà C, Petta S, Enea M, Bruno R, Bronte F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of boceprevir or telaprevir for untreated patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2012;56:850–860. doi: 10.1002/hep.25734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherman KE, Sulkowski M, Zoulim F, Alberti A, Wei LJ, et al. Follow-up of SVR durability and viral resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with telaprevir-based regimens: interim analysis of the EXTEND study; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeuzem S, Sulkowski M, Zoulim F, Sherman KE, Alberti A, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with telaprevir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin: interim analysis of the EXTEND study; Presented at 61st Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Oct. 29–Nov. 2; Boston, MA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobson IM, Poordad F, Brown RS, Jr, Kwo PY, Reddy KR, Schiff E. Standardization of terminology of virological response in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: panel recommendations. J. Viral. Hepat. 2012;19:236–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernstein B, Menon R, Klein CE, Lawal AA, Nada A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of the HCV protease inhibitor ABT-450 with ritonavir following multiple ascending doses in healthy adult volunteers; Presented at HepDART; Dec. 6–10; Kohala Coast, Hawaii. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stauber K, Rivera J, Desphande M. Non-clinical studies to assess the potential for drug-drug interactions of ACH-1625a clinically effective HCV protease inhibitor; Presented at 61st Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Oct. 29–Nov. 2; Boston, MA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bronowicki JP, Pol S, Thuluvath P, Larrey D, Martorell CT, et al. Asunaprevir (ASV; BMS-650032), an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infection; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eley T, Gardiner DF, Persson A, He B, You X, et al. Evaluation of drug interaction potential of the HCV protease inhibitor asunaprevir (ASV; BMS-650032) at 200 mg twice daily (BID) in metabolic cocktail and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) probe studies in health volunteers; Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang L, Zhang Y, Weigl P, Shulman N, Smith PF, Tran J. Danoprevir does not change the effect of ritonavir on the pharmacokinetics of cytochrome P450 3 A substrate midazolam or the CYP2C9 substrate warfarin; Presented at 112th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.; March 2–5; Dallas, TX. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Lalezari J, Crespo I, Davis M, et al. GS-7977 400 mg QD safety and tolerability in the over 500 patients treated for at least 12 weeks; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moreira S, Haznedar H, Marbury TC, Robson RA, Smith W, et al. The effect of mild to moderate renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics (PK) of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) polymerase inhibitor mericitabine (MCB, RG7128); Presented at 62nd Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 4–8; San Francisco, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Purohit VS, Fairman D, Fang J, Dickins M, Rosario M, Hammond J. Evaluation of CYP3A mediated drug interactions for filibuvir in healthy volunteers: filibuvir as an object and precipitant; Presented at Am. Soc. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.; March 17–20; Atlanta, GA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Bain V. Quadruple therapy with tegobuvir and GS-9256 plus PegIFN/RBV shows potent viral suppression with shortened therapy in genotype 1 HCV, but safety concerns preclude future development of the combination; Presented at 47th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 18–22; Barcelona, Spain. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bavisotto L, Wang C, Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Zeuzem S, et al. Antiviral, pharmacokinetic and safety data for GS-9190, a non-nucleoside HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor, in a phase-1 trial in HCV genotype 1 infected patients; Presented at 58th Annu. Meet. Am. Assoc. Study Liver Dis.; Nov. 2–6; Boston, MA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maring C, Wagner R, Hutchison D, Flentge C, Kati W, et al. Preclinical potency, pharmacokinetic and ADME characterization of ABT-333, a novel non-nucleoside HCV polymerase inhibitor; Presented at 44th Annu. Meet. Eur. Assoc. Study Liver; April 22–26; Copenhagen, Den.. 2009. [Google Scholar]