Abstract

We examined total mercury and selenium levels in muscle of striped bass (Morone saxatilis) collected from 2005 to 2008 from coastal New Jersey. Of primary interest was whether there were differences in mercury and selenium levels as a function of size and location, and whether the legal size limits increased the exposure of bass consumers to mercury. We obtained samples mainly from recreational anglers, but also by seine and trawl. For the entire sample (n = 178 individual fish), the mean (± standard error) for total mercury was 0.39 ± 0.02 μg/g (= 0.39 ppm, wet weight basis) with a maximum of 1.3 μg/g (= 1.3 ppm wet weight). Mean selenium level was 0.30 ± 0.01 μg/g (w/w) with a maximum of 0.9 μg/g). Angler-caught fish (n = 122) were constrained by legal size limits to exceed 61 cm (24 in.) and averaged 72.6 ± 1.3 cm long; total mercury averaged 0.48 ± 0.021 μg/g and selenium averaged 0.29 ± 0.01 μg/g. For comparable sizes, angler-caught fish had significantly higher mercury levels (0.3 vs 0.21 μg/g) than trawled fish. In both the total and angler-only samples, mercury was strongly correlated with length (Kendall tau = 0.37; p < 0.0001) and weight (0.38; p < 0.0001), but was not correlated with condition or with selenium. In the whole sample and all subsamples, total length yielded the highest r2 (up to 0.42) of any variable for both mercury and selenium concentrations. Trawled fish from Long Branch in August and Sandy Hook in October were the same size (68.9 vs 70.1 cm) and had the same mercury concentrations (0.22 vs 0.21 ppm), but different selenium levels (0.11 vs 0.28 ppm). The seined fish (all from Delaware Bay) had the same mercury concentration as the trawled fish from the Atlantic coast despite being smaller. Angler-caught fish from the North (Sandy Hook) were larger but had significantly lower mercury than fish from the South (mainly Cape May). Selenium levels were high in small fish, low in medium-sized fish, and increased again in larger fish, but overall selenium was correlated with length (tau = 0.14; p = 0.006) and weight (tau = 0.27; p < 0.0001). Length-squared contributed significantly to selenium models, reflecting the non-linear relationship. Inter-year differences were explained partly by differences in sizes. The selenium:mercury molar ratio was below 1:1 in 20% of the fish and 25% of the angler-caught fish. Frequent consumption of large striped bass can result in exposure above the EPA’s reference dose, a problem particularly for fetal development.

Keywords: Mercury, Selenium, Fish consumption, Food chain effects, Risk

1. Introduction

Fish are an important component of aquatic food chains and human diets, and depending upon the species, age, and size, they occupy different trophic levels in aquatic food webs (Able and Fahay, 2010). Fish are an important source of protein and polyunsaturated fatty acids for many people throughout the world, and fishing also provides valuable recreational, cultural and esthetic benefits (Toth and Brown, 1997; Burger, 2000, 2002). However, levels of contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and methylmercury (MeHg) can pose health risks, particularly for pregnant women and young children (IOM, 1991, 2006), and can counteract the health benefits of fish oils (Guallar et al., 2002).

Fish are also the primary source of methylmercury exposure for humans and for other top-level predators such as piscivorous birds (Rice et al., 2000). Understanding how mercury levels vary with size of the fish and locality, provides information for both ecological and human health risk assessment. Changes in fish populations and demography brought about by contaminants, competition, or overfishing (predation) can have effects on both their prey populations and their predators (Hartman and Brandt, 1995). Considerable attention has been devoted to mercury levels in a wide range of freshwater fish, but there is less information on saltwater fish and marine ecosystems (Legrand et al., 2005).

Selenium, an essential trace element, provides some protective benefit against mercury toxicity (Ralston and Raymond, 2010). There is a current controversy over how much selenium (based on selenium:mercury molar ratio) is needed to protect against mercury toxicity, and whether in fish (or in humans) there is sufficient mutual bioavailability to allow the two elements to interact freely. Although the traditional view of methylmercury toxicity involves binding to sulfydryl groups and altering enzymes, microtubule synthesis, and neurologic function, recent suggestions emphasize the interaction with selenium (Ralston, 2009). Ralston and Raymond (2010) argue that the high affinity between selenium and mercury interferes with selenoenzyme activity and synthesis, and is a major mechanism of mercury toxicity.

This paper is part of a larger study of mercury levels in 19 species of New Jersey coastal fish (Burger and Gochfeld, 2011; Burger et al., 2011). In this paper we examine the levels of total mercury and selenium in striped bass (Morone saxatilis) collected from 2005 through 2008 at sites in coastal New Jersey. Mercury was analyzed because of its potential ecosystem and human health effects, and because recreational fishers were anxious to learn about a potential risk from mercury. Selenium was analyzed because of its reported protective effects against mercury toxicity (Ganther et al., 1972; Kim et al., 1977; Ringdal and Julshamn, 1985; Satoh et al., 1985). We examined whether New Jersey’s legal size limits for striped bass fishing, imposed an exposure burden on people who consume legal-sized fish. We also test whether a concomitant increase in selenium and its protective effect would occur in these larger fish. There is an abundant literature relating mercury levels to fish size in many species, including striped bass (Mason et al., 2006). We were interested in the consistency of this relationship across a large size range of striped bass, both above and below “legal” size limits. Size limits for striped bass vary by State. Recently New Jersey has used either 61 or 71 cm = 24 in. or 28 in.), whereas New York has 35 cm (14 in.) limit for the Hudson River. We also examined the relationship between fish size and selenium level. This paper also examines potential exposure to consumers who eat striped bass from New Jersey waters in relation to the Environmental Protection Agency’s reference dose (0.1 μg/kg/day) and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Minimal Risk Level (0.3 μg/kg/day).

2. Methods

2.1. Study species: striped bass

We studied striped bass because it is a very popular recreational fish in New Jersey and is large enough to bioaccumulate methylmercury and pose a potential health risk to people who consume large bass frequently (Alexander et al., 1973; Levinton and Pochron, 2008; VIMS, 2008). Striped bass is a long-lived (> 30 years) predatory species that occurs along the North American Atlantic Coast from the St. Lawrence River to the St. Johns River in Florida (Raney, 1952; Able and Grothues, 2007) and the Gulf of Mexico. It has been transplanted to the Pacific Coast, and it occurs in many freshwater lakes. It is also farmed, mainly as a hybrid (with white bass, Morone chrysops). It is important within estuarine and marine ecosystems because it can effect prey populations and competitors (Raney, 1952; Hartman and Brandt, 1995). Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and Hudson-Raritan Estuary harbor the majority of breeding fish, and migratory movements are tracked (Grothues, 2008). Striped bass are both obligatory estuarine dependent (for spawning) and a transient species (Able, 2003; Able et al., 2007). After decades of decline and scarcity, extensive management (mainly fishing-bans 1982–1995), allowed populations of striped bass to increase markedly over the last 20 years (ASMFC, 2007), ironically raising concerns about the negative impact of this large predator competing with other fish predators, and impacting prey species (Secor, 2000; Nemerson and Able, 2003; Baum et al., 2000). In some east coast bays and estuaries, striped bass is one of the most abundant species (Able et al., 2007), providing a prey base of young fish, and supporting a recreational fishery of older fish.

2.2. Field sampling

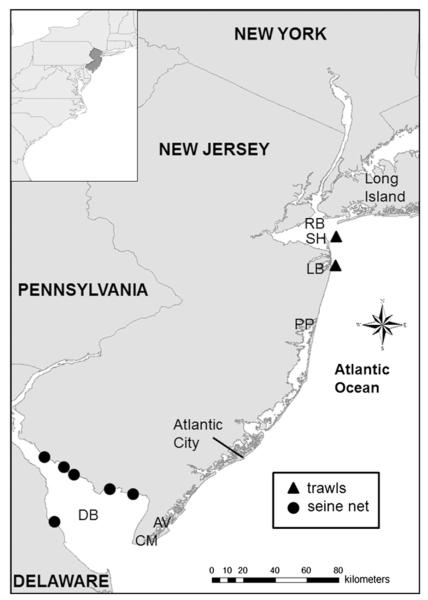

From 2005 to 2008, in cooperation with the Jersey Coast Anglers Association (JCAA), and several affiliated member clubs, and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), we obtained samples of striped bass from various places on the New Jersey Coast (Fig. 1). Fish were obtained from recreational anglers at official tournaments and from trawl and beach seine sampling activities of the NJDEP and the Public Service Electric and Gas (PSE&G) corporation’s mitigation surveys. The trawl and seine samples provided fish smaller than the legal recreational size limit. Most striped bass are caught May through November. In 2005 the legal size limit for striped bass was one fish between 61–71 cm (24–28 in.) and one 86 cm (34 in.) or greater. From 2006 to at least 2011, the limit was two fish of 71 cm (28 in.) or greater.

Fig. 1.

Locations where fish were collected in New Jersey. SH = Sandy Hook, LB = Long Branch, PP = Point Pleasant, AV = Avalon, CM = Cape May, DB = Delaware Bay. Tip of Sandy Hook is at 40°28.8’N; 74°0.3’W. Tip of Cape May is at 38°5.55N; 74°5.77’W.

There are several annual striped bass fishing tournaments in New Jersey mainly in the late spring and fall. Fish from tournaments were either taken home for consumption by the families of the fishermen, or were donated to orphanages or food banks. Tournaments were scheduled at different times in the northern and southern parts of the state to take advantage of the seasonal availability of bass of legal size, therefore a balanced design for all factors was not possible. The North (Sandy Hook & Point Pleasant) samples were all taken in spring tournaments, while the South samples (Avalon, Cape May, Delaware Bay) were from fall tournaments. Fig. 1 shows the sampling locations.

Total length was measured from the tip of the snout to tail tip with the caudal fin compressed top to bottom to maximize length as per the fishing regulations. Fork length was measured to the base of the caudal fin. In this paper we use total length because this relates directly to fishing size limits and advisories and is what anglers’ measure. Fish were weighed on spring scales to the nearest gram. We explored a curvilinear relationship by creating the variable length-squared. We explored several indices of condition, including a simple measure of weight/length, but relied on Fulton’s K (K = weight/length3). However, condition did not enter any of the models and was no more informative than weight and length.

In the field a small (ca. 20 g) sample of muscle was taken from near the base of the caudal fin about midway between the dorsal and ventral surfaces. Each sample was placed in a plastic bag with sample number, location, date, fish weight, and total and standard length of the fish. Fish samples were kept in coolers and brought to the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute (EOHSI) of Rutgers University for analysis.

2.3. Chemical analysis

Analyses were conducted in the EOHSI Elemental Analysis Laboratory. All laboratory equipment and containers were washed in 10% HNO3 solution and deionized (18 megaohm) water rinsed prior to each use (Burger et al., 2001a). At EOHSI, a 2 g (wet weight) sample of skin-free muscle was digested in ultrex ultrapure nitric acid in a microwave (MD 2000 CEM), using a digestion protocol of three stages of ten min each under 3.5, 7, and 10.6 kg/cm2 (50, 100 and 150 lb/square inch) at 80 × power. Digested samples were subsequently diluted to 25 mL deionized water.

Total mercury was analyzed by the cold vapor technique using the Perkin Elmer FIMS-100 mercury analyzer, with an instrument detection level of 0.2 ng/g, and a matrix level of quantification of 0.002 μg/g. Selenium was analyzed by graphite furnace atomic absorption, with Zeeman correction.

All concentrations are expressed in parts per million of total mercury or total selenium (ppm = μg/g) on a wet weight basis. A DORM-2 Certified dogfish tissue was used as the calibration verification standard. Recoveries between 90% and 110% were accepted to validate the calibration. All specimens were run in batches that included blanks, a standard calibration curve, two spiked specimens, and one duplicate. The accepted recoveries for spikes ranged from 85% to 115%. 10% of samples were digested twice and analyzed as blind replicates (with agreement within 15%). For further quality control on mercury, our laboratory has sent samples to the Le Laboratoire de Santé Publique de Québec as a reference laboratory. The correlation between the two laboratories was over 0.90 (p < 0.0001).

2.4. Statistical analysis

For the total sample (n = 178) and the “legal-size” angle-caught subsample (n = 122) arithmetic means and standard errors are given in Table 1 for mercury, selenium, size variables and selenium:mercury molar ratio. Multiple regression procedures (Table 2) were used on the entire data set, to determine if year, season, length, weight, condition, or location contributed to explaining the variations in amount of mercury and selenium in samples (PROC GLM, SAS, 1995). We grouped locations into a north region and a south region, and the location variable (six sites) was analyzed independently of region. Variables that vary co-linearly are significant only if they contribute independently to explaining the variance. Actual p-values up to 0.50 are given in the tables. The a priori level for significance was designated as p < 0.05. We compared differences among locations and years with the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one way non-parametric analysis of variance (SAS Institute PROC NPAR1WAY with Wilcoxon option). Kendall correlations were used to examine relationships among metals and size variables.

Table 1.

Comparison of fish size and contaminant levels for total sample (n = 178) and “legal size” recreational angler-caught (n = 122) striped bass (Morone saxatilis). Total mercury and selenium are in micrograms per gram (ppm) wet weight. Length is total length in cm (not fork length). All values are arithmetic means ± standard error on raw data. Condition Index K is weight divided by length-cubed. Differences evaluated by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one way analysis of variance yielding a χ2 statistic and p-value.

| All fish, n = 178 |

Angler only, n = 122 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total mercury (μg/g) | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | < 0.0001 |

| Selenium (μg/g) | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | < 0.0001 |

| Total length (cm) | 83.3 ± 1.55 | 92.1 ± 1.13 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight (g) | 7640 ± 366 | 9540 ± 345 | < 0.0001 |

| Condition Index K (W/L3) | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | NS |

| Selenium:mercury molar ratio | 1.89 ± 0.015 | 1.54 ± 0.13 | < 0.01 |

Table 2.

Multiple regression model for total mercury (μg/g wet weight) and selenium (μg/g wet weight) as a function of size, locations, and year for striped bass (Morone saxatilis). Comparing entire sample of Striped Bass (n = 178) with the 122 angler-caught fish using type I models from PROC GLM (SAS Institute).

| Mercury, F (p) | Selenium, F (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | All bass, n = 178 | Angler, n = 122 | All bass, n = 178 | Angler, n = 122 |

| R 2 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.34 |

| Model F (p=) | 9.97 (<00.0001) | 5.13 (<00.0001) | 6.41 (<00.0001) | 3.74 (<0.0001) |

| Variables | ||||

| Region (north/south) | 40.3 (<0.0001) | 19.9 ( < 0.0001) | 3.76 ( = 0.055) | 1.37 NS |

| Length | 68.8 ( < 0.0001) | 15.0 (= 0.002) | 5.78 (< 0.012) | 19.1 (< 0.0001) |

| Length squared | 5.30 (=0.023) | 4.04 (=0.048) | 33.8 (< 0.0001) | 12.2 (< 0.0001) |

| Weight | 1.56 NS | 0.05 NS | 0.99 NS | 0.34 NS |

| Condition (K) | 0.5 NS | 0.87 NS | 1.39 NS | 0.04 NS |

| Length × region | 1.44 NS | 0.02 NS | 4.67 ( = 0.032) | 0.02 NS |

| Year | 2.48 ( = 0.064) | 1.23 NS | 2.93 ( = 0.036) | 1.27 NS |

| Region × year | 5.08 (= 0.008) | 8.23 (= 0.005) | 9.53 ( = 0.0025) | 2.32 NS |

| Location | 3.36 (= 0.012) | 1.25 NS | 6.83 ( = 0.0001) | 2.07 NS |

2.5. Molar ratios

We converted concentration from μg/g to mmol/g, by dividing the concentration of total mercury by its molecular weight of 200.59 and the concentration of selenium by its molecular weight of 78.96. We report the molar ratio of selenium to mercury. Some papers report its reciprocal, a mercury: selenium ratio instead.

3. Results

Overall, the striped bass collected in this study (n = 178) averaged 7640 g (arithmetic mean ± standard error = 410 g), and had a mean total length of 83.3 ± 1.55 cm (Table 1). Mean total mercury on wet weight basis was 0.39 ± 0.02 μg/g (0.39 parts per million), with a median = 0.30). The maximum total mercury concentration was 1.3 μg/g (1.3 ppm), and three fish exceeded 1.0 μg/g. Length and weight were highly correlated (tau = 0.88, p < 0.0001), while mercury and selenium were very weakly correlated (tau = 0.09, p = 0.07). Mercury was correlated with length and weight (tau = 0.37, p < 0.0001), but not with condition. Selenium was correlated more strongly with weight (tau = 0.27, p < 0.0001) than with length (tau = 0.13, p = 0.008), and was not correlated with condition. Overall there was little relationship between mercury and selenium levels (tau = 0.09; p = 0.07). They were not correlated in any subsample, except marginally in angler-caught fish in the south (tau = 0.18; p = 0.03).

3.1. Multivariate analysis

For the entire sample, the full multiple regression model explained 54% of the variation in mercury and 43% of the variation in selenium. For the angler-caught fish only (n = 122) the models explained 42% and 34% respectively. Mercury was strongly correlated with length and length generally contributed the highest r2 and F-value for mercury, with a significant non-linear contribution by length-squared (Table 2). The trawling conducted by the State apparently sampled the environment differently from the anglers (Table 3. Region (north vs south) also contributed strongly for both the total sample and the angler-caught fish. Year, year × region, and location also contributed significantly (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Comparison of angler-caught vs trawl-caught fish in the size overlap range (61–92 cm) for striped bass (Morone saxatilis). All values are arithmetic means ± standard error on raw data. Differences evaluated by Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one way analysis of variance yielding a χ2 statistic.

| Total mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angler (n = 58) | 0.39 ± 0.033 | 0.26 ± 0.015 | 79.1 ± 1.1 | 5523 ± 325 |

| Max = 1.3 | Max = 0.49 | Max = 91 | Max = 10,433 | |

| Trawl (n = 40) | 0.21 ± 0.015 | 0.23 ± 0.015 | 73.4 ± 1.2 | 3714 ± 232 |

| Max = 0.45 | Max = 0.37 | Max = 92 | Max = 8247 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p =) | 15.3 ( < 0.0001) | 1.43 (0.23) | 11.2 (0.0008) | 15.8 (< 0.0001) |

Table 4.

Comparison of fish size and contaminant levels by year in comparable subsets of striped bass (Morone saxatili). Total mercury and selenium are in micrograms per gram (ppm) wet weight. Length is total length in cm. All values are arithmetic means ± standard error on raw data. Differences evaluated by Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one way analysis of variance yielding a χ2 statistic.

| Total mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | Condition (K) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) All angler-caught fish comparing 2005 with 2006 | |||||

| All angler, n = 122 | 0.48 ± 0.025 | 0.29 ± 0.010 | 92.2 ± 1.4 | 9540 ± 462 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.3 | max= 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max = 24,500 | Max = 0.015 | |

| 2005, n = 60 | 0.55 ± 0.035 | 0.29 ± 0.013 | 93.3 ± 2.4 | 9650 ± 637 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.3 | Max = 0.56 | Max = 124 | Max=23,800 | Max = 0.013 | |

| 2006, n = 54 | 0.39 ± 0.036 | 0.29 ± 0.019 | 92.4 ± 1.5 | 10,200 ± 744 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.1 | Max = 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max = 24,400 | Max = 0.015 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p =) 2005 vs 2006 10.9 (0.001) | 0.04 ( > 0.5) | 1.2 (0.28) | 0.05 (> 0.5) | 3.5 (0.06) | |

| (b) Sandy Hook angler-caught fish comparing 2005 vs 2006 | |||||

| Sandy Hook, n = 24 (2005) | 0.53 ± 0.041 | 0.33+0.018 | 102.1+2.4 | 11,738+712 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.02 | Max = 0.49 | Max = 114 | Max = 17,282 | Max = 0.013 | |

| Sandy Hook, n = 27 (2006) | 0.28+0.037 | 0.36+0.012 | 94.7+1.7 | 9698+582 | 0.011 |

| Max = 0.67 | Max = 0.51 | Max = 113 | Max = 16,465 | Max = 0.014 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p =) | 14.7 (0.0001) | 2.7 (0.10) | 7.2 (0.007) | 4.3 (0.04) | 1.1 (0.03) |

| (c) Trawled fish from Sandy Hook comparing 2007 and 2008 | |||||

| 2007, n = 17 | 0.21+0.019 | 0.28+0.013 | 70.9+2.4 | 3605+349 | 0.010 |

| Max = 0.45 | Max = 0.27 | Max = 92 | Max = 7229 | Max = 0.012 | |

| 2008, n = 12 | 0.19+0.23 | 0.26+0.024 | 75.7+1.6 | 3879+195 | 0.009 |

| Max = 0.29 | Max = 0.33 | Max = 84 | Max = 5103 | Max = 0.010 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p =) | 0.23 (> 0.60) | 0.05 (> 0.80) | 3.3 ( =0.069) | 1.9 (0.16) | |

| (d) Cape May angler-caught fish comparing of 2005 vs 2006 | |||||

| Cape May, n = 12 (2005) | 0.68+0.078 | 0.35+0.034 | 105.4 ± 3.2 | 12,507+1157 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.1 | Max = 0.57 | Max = 124 | Max = 23,079 | Max = 0.012 | |

| Cape May, n = 27 (2006) | 0.50+0.055 | 0.23+0.028 | 90.1+2.3 | 13,834+4257 | 0.013 |

| Max = 1.0 | Max = 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max 24,494 | Max = 0.015 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p =) | 2.9 (0.09) | 7.5 (0.006) | 10.6 (0.001) | 0.05 (> 0.5) | 6.5 (0.01) |

Table 5.

Analysis of angler-caught striped bass (Morone saxatilis) by location. All values are arithmetic means + standard error on raw data. Differences evaluated by Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric one way analysis of variance yielding a χ2 statistic.

| (a) Year 2005 angler-caught fish, analyzed by location and year (north to south) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | Condition (K) | |

| All 2005 | 0.55+0.035 | 0.29+0.13 | 93.3+2.4 | 9650+637 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.3 | Max = 0.57 | Max = 124 | Max = 23,079 | Max = 0.013 | |

| Sandy Hook, n = 24 | 0.53+0.041 | 0.33+0.018 | 102.1+2.4 | 11,800+712 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.02 | Max = 0.49 | Max = 114 | Max = 17,300 | Max = 0.013 | |

| Avalon, n = 17 | 0.24+0.079 | 0.22+0.019 | 68.8+1.6 | 3480+197 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.3 | Max = 0.37 | Max = 87 | Max = 5630 | Max = 0.013 | |

| Cape May, n = 12 | 0.68+0.078 | 0.35+0.034 | 105.4+3.2 | 12,500+1160 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.1 | Max = 0.57 | Max = 124 | Max = 23,100 | Max = 0.012 | |

| Delaware Bay, n = 7 | 0.80+0.025 | 0.27+0.029 | 102.1+3.2 | 12,600+1180 | 0.012 |

| Max = 0.91 | Max = 0.36 | Max = 119 | Max = 18,800 | Max = 0.013 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 =(p = ) 4 locations | 16.6 (0.0008) | 14.7 (0.002) | 34.5 ( < 0.0001) | 35.6 ( < 0.0001) | 6.8 (0.08) |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 =(p = ) without Avalon | 11.2 (0.004) | 2.8 (0.25) | 0.83 ( > 0.5) | 0.01 ( > 0.5) | 5.3 (0.07) |

| (b) Year 2006 angler = caught fish analyzed by location | |||||

|

| |||||

| Mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | Condition (K) | |

|

| |||||

| All 2006, n = 54 | 0.39+0.036 | 0.29+0.019 | 92.4+1.5 | 10,232+744 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.0 | Max = 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max = 24,494 | Max = 0.015 | |

| Sandy Hook, n = 27 | 0.28+0.037 | 0.36+0.012 | 94.7+1.7 | 9698+582 | 0.011 |

| Max = 0.67 | Max = 0.51 | Max = 113 | Max = 16,465 | Max = 0.014 | |

| Cape May, n = 27 | 0.50+0.055 | 0.23+0.028 | 90.1+2.3 | 13,834+4257 | 0.013 |

| Max = 1.0 | Max = 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max 24,494 | Max = 0.015 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 =(p = ) | 6.7 (0.001) | 14.6 (0.0001) | 3.8 (0.051) | 0.35 (0.55) | 5.5 (0.018) |

| (c) Trawled fish comparing Sandy Hook with Long Branch for 2007 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Total mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | ||

|

| |||||

| Long Branch, n = 9 | 0.22+0.036 | 0.11+0.022 | 68.9+2.9 | 3320+682 | 0.09 |

| Max = 0.37 | Max = 0.23 | Max = 90 | Max = 8647 | Max = 0.012 | |

| Sandy Hook, n = 17 | 0.21+0.019 | 0.28+0.013 | 70.1+2.4 | 3605+349 | 0.010 |

| Max = 0.45 | Max = 0.37 | Max = 92 | Max = 7229 | Max = 0.012 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p = ) | 0.65 ( > 0.40) | 15.7 ( < 0.0001) | 0.53 ( > 0.40) | 1.1 (0.29) | |

| (d) Comparing all North vs all South angler-caught fish | |||||

|

| |||||

| Total mercury (μg/g) | Selenium (μg/g) | Length (cm) | Weight (g) | ||

|

| |||||

| North, n = 59 | 0.41+0.031 | 0.34+0.012 | 95.9+1.5 | 10,023+460 | 0.011 |

| Max = 1.02 | Max = 0.51 | Max = 114 | Max = 114 | Max = 0.014 | |

| South, n = 63 | 0.54+0.038 | 0.26+0.016 | 88.6+2.2 | 8817+917 | 0.011 |

| Max1.3 | Max = 0.65 | Max = 124 | Max = 24,494 | Max = 0.015 | |

| Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = (p = ) | 5.33 (0.02) | 18.6 ( < 0.0001) | 7.3 (0.007) | 3.4 (0.06) | 0.15 ( > 0.5) |

For selenium (Table 2), length and length squared were both highly significant. Location made a stronger contribution than region (p < 0.0001 for the full model), while neither was significant for the angler-only subgroup. Neither weight nor condition entered any selenium models independently.

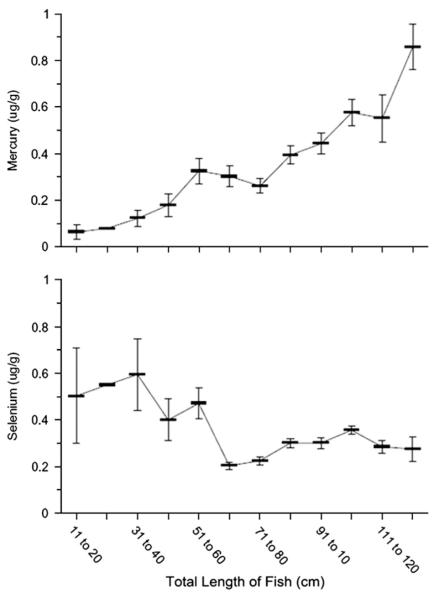

3.2. Mercury, selenium and size

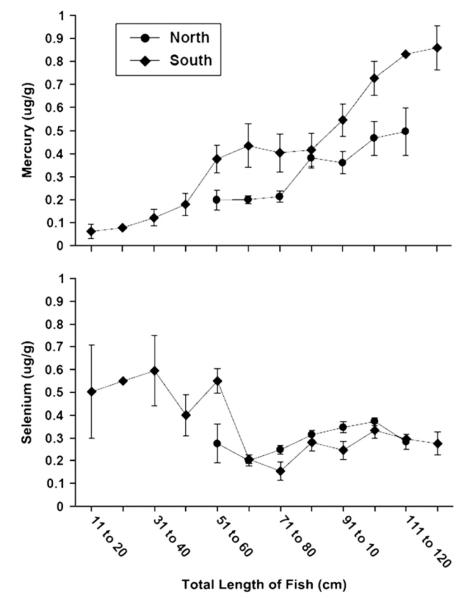

There was an overall correlation between length and mercury (Kendall tau = 0.37, p < 0.0001). Not surprisingly mercury concentrations increased almost monotonically but non-linearly with fish length (Fig. 2), with no evidence of a plateau at the largest fish in our sample (124 cm, 13,500 g). Length alone yielded an r-square of 0.24 for mercury in the full sample, but the r-square for the angler-only fish was only 0.10, reflecting greater heterogeneity in that subset. For a given size range, mercury levels were significantly higher in the north (spring) than in the south (fall) (Fig. 3). Samples from southern New Jersey, including the small seined fish, show a steeper rise in mercury against length, than fish from northern New Jersey (Fig. 3). Correlation was also lower in the north (tau = 0.20; p = 0.024) than in the south (tau = 0.39; p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Mean mercury (μg/g, wet weight) and selenium levels as a function of total fish length (cm).

Fig. 3.

Mean mercury and selenium levels (μg/g, wet weight) for fish collected in the north and the south of New Jersey as a function of total length of the fish (cm).

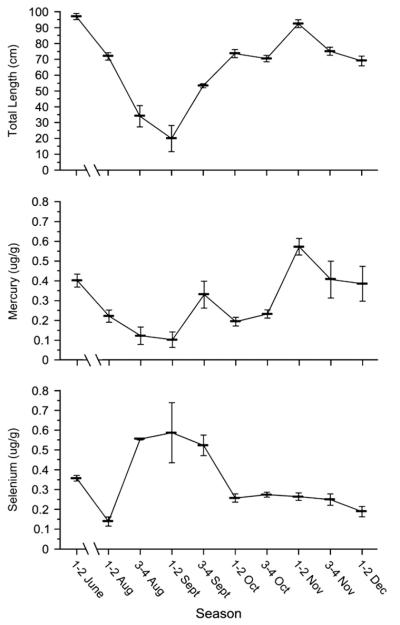

There was seasonal variability in mercury which was positively related to the size of fish obtained in spring, summer, and autumn, while selenium was inversely related (Fig. 4). Comparing the angler-vs trawl-caught fish in the range of size overlap (61–92 cm), revealed a higher level of mercury in the former, than in the latter (Table 3). By comparison for fish above 61 cm, there was a similar increase in selenium with fish size in north and south (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Mean mercury (μg/g, wet weight) and selenium levels, and mean total length (cm) as a function of date of collection. The numbers before the month are weeks. Thus 1–2 October = 1st and 2nd week of October.

Selenium varied less strongly with length and weight. Whereas length and weight explained 27% of the variance in mercury, combined in the linear model they explained only 10% of the variance in selenium, with weight having the larger contribution. The relationship of selenium with length was strongly non-linear, and length-squared entered the model for all fish and for angler-caught fish (p < 0.0001).

3.3. Mercury and selenium by year

There are four subsets of data that allow comparison between years. The fish caught by anglers in 2005 (n = 60) had higher mercury than those (n = 54) caught in 2006 (Table 4a). The tournament locations were not uniform in the two years due to conflicts in tournament schedules, but the size of the fish was not different in the two years. The Sandy Hook subset (Table 4b) showed the same difference for mercury for 2005 vs 2006. However, the trawled fish from the Sandy Hook area showed no difference in mercury or selenium between 2007 and 2008 (Table 4c). The Cape May fish showed slightly higher mercury in 2005 and significantly higher selenium compared with 2006 (Table 4d).

3.4. Mercury and selenium by location

In 2005 there were four locations with sample sizes adequate for comparison, and mercury ranged from 0.24 to 0.80 μg/g, with highly significant variability (even after excluding the very low fish from Avalon (Table 5a). Selenium varied significantly from 0.22 to 0.35 μg/g, but after removing Avalon, the difference was no longer significant. For the 2006 angler-caught fish, mercury was significantly higher at Cape May and selenium was significantly lower there (Table 5b). The Sandy Hook fish were actually slightly longer but not heavier, and had a significantly lower condition K Index (p = 0.01). The Sandy Hook fish were obtained in June and the Cape May fish in November. The 2007 trawl sample obtained fish from Long Branch and Sandy Hook revealing no difference in mercury, while the Long Branch fish had higher selenium (Table 5c). Overall angler-caught fish from the north (n = 59) had lower mercury (0.41 μg/g) than those from the south (0.54 μg/g) (p = 0.02), and higher selenium (0.34 μg/g vs 0.26 μg/g; p < 0.0001, Table 5d).

3.5. Molar ratios

The selenium:mercury molar ratio averaged 1.89 in the entire sample and 1.54 in the angler-caught fish. Table 6 shows the decline in the ratio with increasing fish size. Overall 35 of 178 fish (19.7%) had Se:Hg ratios below 1:1. However, 31 of the 122 angler-caught fish (25%) had Se:Hg ratios below 1.1

Table 6.

Mercury concentration, molar ratios and number of exceedences in New Jersey Striped Bass for the four size categories related to legal size limits of under 61 cm (24 in.), 61–71 cm (24–28 in., and 71–86 cm (28–34 in.), and > 86 cm (over 34 in.). The intergroup difference in mercury is significant (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 34; p < 0.0001). Although there is an overall increase of selenium with size, the variation is nonlinear, and concentration is relatively high in smaller fish (χ2 = 43; p < 0.0001).

| Up to 61 cm ( < 24 in.) | 61.1–71 cm (24–28 in.) | 72.1–86 cm (28–34 in.) | > 86 cm ( > 34 in.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | 18 | 33 | 46 | 81 |

| Total mercury (mean+SE) | 0.202 ± 0.034 | 0.301 ± 0.045 | 0.324 ± 0.030 | 0.512 ± 0.031 |

| Selenium (mean+SE) | 0.456 ± 0.048 | 0.203 ± 0.016 | 0.256 ± 0.016 | 0.322 ± 0.013 |

| Correlation Hg with Se Tau (p = ) | 0.14 (0.44) | 0.07 ( > 0.5) | 0.25 (0.016) | − 0.06 (0.43) |

| 0.60 (0.001) | 0.05 ( > 0.5) | 0.25 (0.016) | 0.27 (0.0004) | |

| > 0.3 ppm total Hg | 3 | 8 | 18 | 61 |

| > 0.5 ppm total Hg | 1 | 5 | 6 | 40 |

| >1.0 ppm total Hg | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Assuming 90% of total Hg is MeHg | ||||

| > 0.3 ppm MeHg | 3 | 7 | 16 | 60 |

| > 0.5 ppm MeHg | 1 | 4 | 5 | 35 |

| > 1.0 ppm MeHg | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Se:Hg molar ratio | 5.67 | 1.69 | 1.98 | 1.77 |

| < 1.0 | 0 | 10 (30%) | 5 (11%) | 20 (25%) |

| 1–5 | 8 (44%) | 21 (64%) | 37 (80%) | 51 (63%) |

| > 5 | 10 (56%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (9%) | 10 (12%) |

4. Discussion

In striped bass, as in most fish, mercury levels increase with size. There is also variation by catch location, habitat (freshwater/estuarine/saltwater), and trophic level (Gilmore and Riedel, 2000). In this study, mercury levels were generally correlated with fish size in most samples, although the complex migration patterns and different sample methods and locations, created a heterogeneous data base.

We did not have water samples from or exact coordinates of the locations where the fish were captured, and it is unlikely that this would be a meaningful comparison in the open ocean with a highly migratory species. However, Emery and Spaeth (2011) did find such an association for hybrid striped bass in the Ohio River. Analyses of mercury and selenium in sea water are very variable, partly reflecting real differences and partly the difficulty (particularly in the past) of analyzing at the nanogram per liter level. Mercury values are generally in the 120–150 ng/L, but range up to 364 ng/L (Fitzgerald and Lyons, 1973), with values in the microgram range in industrially polluted inshore waters. Selenium concentrations are in the 30–200 ng/L range (Riso et al., 2004).

4.1. Movements of striped bass

Striped bass are completely dependent upon estuarine habitats at some times of the year and stages of their cycle (Able and Grothues, 2007), allowing exposure to land-based anthropogenic mercury. The main breeding areas for striped bass are the Hudson-Raritan, Delaware Bay, and Chesapeake Bay estuaries. The populations of striped bass from Chesapeake Bay to the Bay of Fundy are considered anadromous and highly migratory (Rulifson and Dadswell, 1995; Bjorgo et al., 2000). Striped bass in New Jersey waters (e.g. Newark Bay, Raritan Bay, Delaware Bay) move within bays and estuaries (Tupper and Able, 2000), and are most abundant in bays in the early spring and late fall (Able et al., 2007). Size does not vary randomly with season. Large fish move up the bays and estuaries to breed in the spring, then spend summer in the ocean, some reaching New England, and return further offshore in the autumn to winter along the coast and in the bays (Reiger, 2006; Able and Fahay, 2010; Able and Grothues, 2007).

Some tagged striped bass have remained sedentary for many months, staying within an area of only meters (Ng et al., 2007). Others apparently never leave their estuaries. Males and females differ in migratory pattern, more males remain in the estuary in summer while most females migrate north along the coast. Some bass tagged in Delaware Bay have been captured elsewhere along the Jersey coast, off Long Island, New Hampshire, and in the Saco River in Maine (Clark, 1968; Able and Grothues, 2007).

In Delaware Bay resident fish made up only 2.8% of the tagged bass (N = 105), while seasonal inlet visitors = 36%, seasonal estuary visitors = 50%, and seasonal river visitors = 11%. Some individual fish exhibited different patterns in different years. Only 58% of the tagged striped bass that left the estuary system returned either the same season or in subsequent years (Able and Grothues, 2007). These movement data are relevant because they demonstrate that striped bass move both within bays and estuaries and along the Atlantic Coast, making it more difficult to identify the site(s) of exposure to mercury for fish sampled at the Atlantic coastal locations, and contributing to heterogeneous sampling.

A significant sampling difference is reflected in Table 3, where angler-caught had higher mercury levels than trawl caught fish, selecting fish only in the range of size overlap (61–92 cm). Angler fish were slightly larger than trawl caught fish, but that explains only part of the difference, the remainder reflecting different sampling means. Also, recreational fishing for striped bass is not allowed in federal waters beyond the three mile (4.8 km) limit, so that only part of the migrating striped bass populations is available for sampling by anglers.

The information on migration patterns makes it unlikely that a sample will include fish that spawn in a more northern estuary. Thus it is likely that the fish from Sandy Hook (Raritan Bay) reflect partly the Hudson-Raritan stock (Secor et al., 2001), and unlikely that Hudson-Raritan fish are included in the south Jersey/Delaware Bay samples.

4.2. Mercury levels in striped bass variability with length

Numerous studies of many fish species show a general correlation between size and concentration of persistent pollutants. Mercury levels in fish are partly a result of trophic level. Species that are larger and higher on the food web (e.g. predators) have higher mercury levels through bioamplification (Cizdziel et al., 2003). This relationship, however, depends upon the size of the fish. Within a species, the younger, smaller fish are lower on the food chain, and thus are expected to have lower mercury levels. This is clearly seen in the present data set. Fish below 61 cm averaged 0.21 μg/g compared with 0.41 for fish ≥61 cm (t = 3.1, p = 0.002).

Both mercury and selenium increased with size of the fish and inter-year differences in mercury were partly attributable to differences in fish size (see Tables 4b and 4d). A striking exception was the similar mercury concentrations in the seined fish from Delaware Bay (mean length 39 cm mercury = 0.21 μg/g) compared with coastal trawled fish (length 70 cm; mercury 0.21 μg/g). These samples were obtained in late spring when fish that had traveled up the Delaware River to spawn would have been moving out to sea. The coastal sample may have been heterogeneous including migrants from farther south.

4.3. Mercury levels in striped bass by location

Abdelouahab et al. (2008) reported a difference in mercury levels in fish as a function of ecosystem. Our a priori expectation was that bass from northern New Jersey waters, mainly around Sandy Hook would reflect urban contamination from the Hudson-Newark estuary as well as from Raritan Bay, and would therefore have higher mercury levels reflecting this historically more industrialized region which formerly contained several mercury-releasing industries. At least two major mercury ‘hot spots’ exist in the region, one in western Raritan Bay (Greig and McGrath, 1977) and another in Berry’s Creek which enters the Passaic River and Newark Bay (Cardona-Marek et al., 2007). However, mercury levels were actually lower in Sandy Hook fish than in southern coastal New Jersey fish in both 2005 and 2006 (Table 4). Moreover, Delaware Bay fish had higher mercury than Cape May fish (Table 4a). This suggests the importance of improving understanding of the migration patterns and origins of fish taken at various locations.

Seasonality of migration may vary from year to year, and the seasonal variation in mercury probably reflects movements of fish of various sources and sizes, rather than an actual change of concentration in a population. Within the autumn sample, the Avalon fish taken in the first week of Oct (68 cm; 3402 g), first week of Nov (68 cm; 3502 g), and first week of Dec (69 cm; 3477 g), were remarkably consistent in size, while the Cape May fish all taken in early Nov averaged 95 cm and 12,840 g. Within the Avalon sample there was no difference by month in mercury or selenium. Despite the size difference, the Cape May fish had only marginally higher mercury (0.54 vs 0.42 ppm; p = 0.07) and there was no difference in selenium (0.26 vs 0.22; p = 0.45).

A much tighter comparison was between the seven Delaware Bay and 38 Cape May fish which averaged very similar in length (102 cm vs 95 cm) and weight (12,580 vs 12,890 g). Mercury was significantly higher in the bay (0.80 vs 0.54 ppm; p = 0.015). Length alone explained 35% of the variance and place alone explained 11% of the variance in this subsample.

The overall north vs south comparison showed higher mercury in the south despite smaller average fish size (Table 5d). This difference was unexpected. This is presumed to reflect contamination from Delaware Bay estuary, but this source remains to be verified. Likewise the season × locality variation in fish size indicates the importance of migration influencing the sampling of striped bass.

4.4. Selenium in fish

There are fewer studies of selenium in fish, especially examining differences by size, season or catch location. Moreover selenium is viewed as a toxic contaminant in some studies and a beneficial nutrient in others. Pakkala et al. (1972) reported that selenium levels were usually below 1 μg/g, and Bourre and Paquotte (2008) reported levels ranging from 0.2 to 0.7 μg/g for several species of fish (but not bass). Striped bass in this study averaged 0.30 μg/g. Bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) from New Jersey averaged 0.37 μg/g (Burger et al., 2004). Three species of flatfish from New Jersey had similar mean selenium levels: Scophthalmus aquosus (0.36 μg/g), Paralichthys dentatus (0.35 μg/g), and Pseudopleuronectes americanus (0.25 μg/g) (Burger et al., 2009). The similarity of these values across species is consistent with homeostatic regulation of this essential element, a constituent of more than 25 selenoproteins. In the present study, selenium increased with length (tau = 0.13, p = 0.008) and weight (tau = 0.27, p < 0.0001), but did not vary with condition (tau = 0.06, p = 0.28). In our comparison of 19 coastal New Jersey fish species, striped bass was one of only three species to show an association between selenium and size (Burger and Gochfeld, 2011).

4.5. Yearly, seasonal and geographical variations

This study reports some inter-year variation in mercury levels, partly reflecting size variation and partly independent yearly effects (see Table 4). Inter-annual variation in mercury levels was evident for striped bass in San Francisco Bay from 1994 to 2000, which was attributed to migratory behavior and wide home ranges (Greenfield et al., 2005). Although they found inter-annual variation, there was no evidence of a trend from 1970 to 2000. However, in some areas of Florida, mercury levels in muscle tissue of bass doubled from 1986 to the about 2000, and averaged 0.85 ppm (Brim et al., 2001).

Geographical variations in mercury concentration have been reported for striped bass. The New Jersey DEP reported on 18 fish from seven locations sampled in 2004 showing total mercury levels ranging from 0.2 to 0.3 μg/g (NJDEP, 2004). In the Chesapeake Bay to the south of New Jersey, mercury levels in striped bass averaged about 0.2 μg/g, with higher levels in larger fish (Mason et al., 2006). These values are generally in the low part of our observed distribution. To the north in the Hudson River estuary, mercury in striped bass ranged up to 1.25 μg/g, with an average of < 0.40 μg/g in 1993 (NY/NJHEP, 2007), 0.28 μg/g in 1999–2003 (CARP, 2005), and 0.34 μg/g in the early 2000s (NYSDEC, 2004). Thus, both to the north and to the south of New Jersey, levels averaged from 0.2 to 0.4 μg/g, and ranged up to 1.25 μg/g, which is similar to the values in this study. Freshwater striped bass can have even higher total mercury levels, with averages of 0.80 and 0.56 μg/g in two Virginia lakes where 95% and 67% of the fish (n = 20 and n = 12) exceeded 0.5 μg/g (ppm) (Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, 2006).

Striped bass collected from the California in Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta averaged 0.49 μg/g of mercury from 1999 to 2000 (Davis et al., 2008). In San Francisco Bay in the late 1990s levels ranged from 0.15 to 0.44 μg/g (Fairey et al., 1997), and later values from Lake Mead averaged 0.3 μg/g (Cizdziel et al., 2003). In Nevada reservoirs, mercury levels averaged as high as 0.95 μg/g (Cooper, 1983), while in Nova Scotia, mercury levels in striped bass muscle averaged 0.77 μg/g, with smaller fish averaging 0.51 μg/g (Ray et al., 1984). These data demonstrate variation in mercury levels in striped bass, but also suggest that (1) it is difficult to compare levels from different places without knowing the dates of collection and size of fish; (2) levels in bass within a state can vary, and, (3) site specific data (as well as year specific data) are required to examine long-term trends in a given region.

4.6. Relationship of mercury and selenium levels with size of other species

In most fish, mercury levels increase with the size and age of the fish (Lange et al., 1994; Bidone et al., 1997; Burger et al., 2001a; Pinho et al., 2002; Green and Knutzen, 2003; Hammerschmidt and Fitzgerald, 2006), including largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides, Davis et al., 2008) and striped bass (Mason et al., 2006). However, this is not always the case (Stafford and Haines, 2001), especially at low mercury levels (Park and Curtis, 1997). It is also not the case for fish that are starving; muscle mass is lost faster than mercury is eliminated (Cizdziel et al., 2002). Larger fish can also have significantly higher mercury levels because elimination rate is negatively correlated with size (Trudel and Rasmussen, 1997).

Increasing mercury levels with size of the fish can be a result of two factors: (1) as fish grow larger they can eat larger prey that have themselves accumulated higher levels of mercury, and (2) larger fish are generally older and have had longer to accumulate mercury. Prey use by striped bass varies by size, with smaller bass eating primarily detritus and crustaceans, with a few small fish; intermediate-sized fish eating crustaceans and fish, and larger bass eating mainly fish (Neuman et al., 2004).

The situation with selenium is unclear because fewer studies have reported selenium levels, and even fewer have examined the relationship between selenium levels and fish size. Pakkala et al. (1972) did not find any correlation between size and selenium levels in striped bass from New York State. Burger et al. (2004) did not find a correlation between fish size and selenium levels for bluefish from the same New Jersey region, but found significant negative correlations for selenium and length for yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and windowpane flounder (Scophthalmus aquosus).

4.7. Mercury, selenium and condition

Length and weight can be combined in a variety of indices to give an estimate of the “condition” of a fish, whether undernourished or fat. We focused primarily on the Fulton K (weight/length cubed), which ranged only from 0.09 to 0.021. As expected condition was strongly correlated with weight (Kendall tau = 0.24, p < 0.0001) and was weakly positively correlated with length (tau = 0.11, p = 0.049). Thus the enhanced condition of the seined sample (smaller than the others), was not due to an overall effect of length.

4.8. Selenium: Mercury molar ratios

Ralston and Raymond (2010) point out that when there is an excess of selenium in fish tissue, the risk from the methylmercury present is reduced, and Ralston (2009) suggested that a simple molar excess (selenium > mercury) is sufficient to confer protection. This principle has become operational in some studies (e.g. Peterson et al., 2009). The present study found 35 fish (19.7%) with Se:Hg molar ratio below 1:1 and 149 (84%) with Se:Hg molar ratio below 5:1. The molar ratio decreased with size of fish, reflecting that mercury has a stronger correlation with size than does selenium. For the angler-caught sample 31 fish (25%) had an Se:Hg below 1:1. Although there is general consensus that an Se:Hg ratio less than 1:1 is potentially hazardous, a truly protective ratio has yet to be identified, and may be elusive and variable.

4.9. Risk to food webs

Risk to the food chain from mercury involves a number of direct and indirect effects. Direct effects include: (1) mercury concentrations in individual striped bass themselves, (2) the population of striped bass, and (3) the organisms that eat them, including humans. Indirect effects, however, include the ability of predators to affect the populations of their prey and competitors (Hartman and Brandt, 1995). Fisheries biologists and ecologists generally focus on the effects of changes in population number of a species caused by a range of environmental factors, but such population changes can affect populations of their prey, competitors, and predators (Mathews and Fisher, 2008).

A combination of overfishing and contamination contributed to the decline of striped bass in the first half of the 20th century, and broad bans imposed by states (1982–1995) allowed the populations to recover in the late 20th century (Nemerson and Able, 2003). Unlike some semelparous species, such as most salmon (one spawning period per lifetime), striped bass return multiple times to spawn (iteroparous), increasing the likelihood of exposure to contaminants in rivers and bays. Laboratory studies have shown sublethal responses of striped bass to mercury (Dawson, 1982), and high levels of mercury can have lethal effects on eggs and fry (Eisler, 1987).

The maximum mercury level in this study was 1.3 μg/g, and angler-caught fish in southern New Jersey averaged 0.54 μg/g. These are well below the muscle levels of 5–20 μg/g (ppm) associated with gross toxicity in fish (Wiener and Spry, 1996; Wiener et al., 2003). However, subclinical effects may occur at levels below 5 μg/g.

At the other extreme of concern, the critical effects levels for consumption by piscivorous mammals is 0.1 μg/g, and for birds in general it is 0.02 μg/g (Eisler, 1985; Yeardley et al., 1998), although marine birds are generally less sensitive (Furness, 1996). This suggests that striped bass pose a cumulative risk to both mammals and birds that consume them. Presumably, however, piscivorous birds would normally catch small striped bass, which had much lower levels (striped bass less than 20 cm total length had mean levels below 0.1 μg/g).

4.10. Risk to Humans

Various health-based guidelines and standards exist for methylmercury levels in fish. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration action level is 1.0 ppm methylmercury (1.0 μg/g), while many other countries use a level of 0.5 ppm (0.5 μg/g). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2001) has set the freshwater criterion at 0.3 μg/g in fish tissue, based upon its Reference Dose (RfD = 0.1 μg/kg-body weight per day) and assuming an average daily fish intake of 17.5 g. The smallest fish to exceed 0.3 ppm methylmercury was 53 cm. Fish smaller than 61 cm (24 in.) averaged 0.21 ppm methylmercury. The extent to which the selenium levels in the striped bass moderate the toxicity of mercury requires additional study. Table 6 indicates the number of exceedances in each size category.

High fishing rates occur in a wide range of cultures, among recreational, subsistence and Native Americans anglers (Harris and Harper, 1998, 2000; Burger, 1998; Burger et al., 2007a, 2007b; Harper and Harris, 2008), in both urban and rural communities (Burger et al., 1999, 2001b; Bienenfeld et al., 2003), and elsewhere in the world (Burger et al., 2003; Yokoo et al., 2003; Abdelouahab et al., 2008). Fish are an excellent, low-fat source of protein and omega-3 fatty acids, that contributes to low blood cholesterol (Anderson and Wiener, 1995), and reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, and pre-term delivery (Daviglus et al., 2002; Patterson, 2002).

However, levels of mercury and PCBs in some fish are high enough to potentially affect people, especially those who eat fish frequently (IOM, 1991, 2006; WHO, 1988; Grandjean et al., 1997; NRC, 2000; Consumer Reports, 2001; Gochfeld, 2003; Hightower and Moore, 2003; Hites et al., 2004). Risk is particularly high for fetal development (Anderson and Bigler, 2006, Pirrone and Mahaffey, 2006) and in small children (Amin-zaki et al., 1978; Crump et al., 1998; Steuerwald et al., 2000) leading to neurobehavioral impairment (NRC, 2000). However, adults too can experience neurobehavioral impairment at relatively low exposure levels (Yokoo et al., 2003). Methylmercury can counteract the positive cardioprotective effects of fish consumption (Guallar et al., 2002; Rissanen et al., 2000; Salonen et al., 1995) and damage the developing nervous system in fetuses and young children. The major source of methylmercury for humans and other vertebrates, is fish consumption (Rice et al., 2000). Further, anglers who eat the most fish have the highest mercury levels (Landrigan et al., 2006). Individuals and communities that rely on fish intake for daily nutrient sustenance may be at risk from chronic, high exposure to methylmercury (Grandjean et al., 1997) as well as other persistent organic pollutants, and high-end fish consumers are at greater risk (Hightower and Moore, 2003).

Most states have responded to the potential public health risk from consumption of fish high in mercury (or other contaminants) by issuing fish consumption advisories for freshwater fish. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2001, 2005) has issued a series of consumption advisories based on methylmercury advising that pregnant women and women of childbearing age who may become pregnant should limit their fish consumption, should avoid eating four types of marine fish (shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish), and should also limit their consumption of all other fish to just “12 ounces” (340 g) per week (FDA, 2001, 2005). However, consuming 340 g/week of fish at 0.20 μg/g (the lowest subgroup average we found), would exceed the EPA RfD. The striped bass fishermen we interviewed reported catching fish multiple times during the season and freezing them for year-round consumption.

There are striped bass consumption advisories in a number of states, including Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey (Gilmore and Riedel, 2000; Davis et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2003; Gobeille et al, 2006; Rhode Island Department of Health, 2009). Striped bass are a popular sport fish, as well as being used for consumption from commercial and recreational sources (MacKenzie, 1992; Hoff et al., 1988). In the New York/New Jersey harbor estuary, 73% of anglers report eating striped bass, the second most popular species (Gobeille et al., 2006). Striped bass have recently undergone a dramatic population recovery (Nemerson and Able, 2003) after more than a decade of fishing moratorium (Reiger, 2006), which makes them readily available for both commercial and recreational fishing (ASMFC, 2007).

The current legal size restrictions in New Jersey favor excess methylmercury exposure for people (without comparable increased selenium intake), and we recommend that at least some smaller size categories be declared legal and that an advisory relating mercury levels to size, be developed for this species in New Jersey marine waters.

Commercially caught striped bass as well as farm raised hybrid bass are sold in fish stores and supermarkets (Burger et al., 2005), increasing the risk that a broader range of people might be exposed to relatively high levels of mercury. Ginsberg and Toal (2000) have suggested that there may be fetal risk from even a single meal of a fish high in mercury. The Food and Drug Administration’s reassurance: “If you eat a lot of fish one week, you can cut back for the next week or two,” (FDA, 2004) ignores the potential impact of a peak exposure during a critical developmental period. As is always the case, people consuming fish frequently need to balance the benefits against the potential adverse effects (Gochfeld and Burger, 2005), seeking an appropriate mix of quantity and nutrients to sustain health.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Tom Fote and members of the JCAA, who collected samples from their fish, or allowed us to do so, and to all the other anglers in the various clubs who provided samples for this project. This research was supported in part by grants from the Jersey Coast Angler’s Association (JCAA), Jersey Coast Shark Anglers (JCSA), the U.S. Department of Energy (through the Consortium for Risk Evaluation with Stakeholder Participation, AI # DE-FG 26-00NT 40938 and DE-FC01-06EW07053), the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP, Office of Science, and Endangered and Nongame Species Program) and NIEHS (P30ES005022). This research was conducted under a Rutgers University Protocol, and fish samples were obtained from recreational anglers, the NJDEP and utility mitigation activities. The conclusions and interpretations reported herein are the sole responsibility of the authors, and should not be interpreted as representing the views of the funding agencies.

References

- Abdelouahab N, Vanier C, Baldwin M, Garceau S, Lucotte M, Mergler D. Ecosystem matters. Fish consumption, mercury intake and exposure among fluvial lake fish-eaters. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;407:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Able KW. A re-examination of fish estuarine dependence: evidence for connectivity between estuarine and ocean habitats. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2003;64:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Able KW, Fahay MP. Ecology of Estuarine Fishes. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Able KW, Grothues TM. Diversity of estuarine movements of striped bass (Morone saxatilis): a synoptic examination of an estuarine system in southern New Jersey. Fish. Bull. 2007;105:235–426. [Google Scholar]

- Able KW, Balletto JH, Hagan SM, Jivoff PR, Strait K. Linkages between salt marshes and other nekton habitats in Delaware Bay, USA. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2007;15:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JE, Foehrenbach, Fisher S, Sullivan D. Mercury in striped bass and bluefish. N. Y. Fish Game J. 1973;20:147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Amin-zaki L, Najeed MS, Clarkson TW, Greenwood MR. Methylmercury poisoning in Iraqi children: clinical observations over two years. Br. Med. J. 1978;1:163–616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6113.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HA, Bigler JD. Development of programs to monitor methyl-mercury exposure and issue fish consumption advisories. In: Pirrone N, Mahaffey KR, editors. Dynamics of Mercury Pollution on Regional and Global Scales: Atmospheric Processes and Human Exposures Around the World. Springer; New York: 2006. pp. 491–509. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PD, Wiener JB. Eating fish. In: Graham JD, Wiener JB, editors. Risk versus risk: tradeoffs in protecting health and the environment. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- ASMFC . Species Profile: Atlantic Striped Bass: New Stock Assessment Indicates a Healthy Stock and Continued Management Success. Atlantic Coast Marine Fisheries Commission; [accessed 3 December 2009]. 2007. ⟨ http://www.asmfc.org/speciesDocuments/stripedBass/profiles/speciesprofile.pdfS ⟩ . [Google Scholar]

- Baum TA, Allen RL, Corbett HE. New Jersey Striped Bass Fisheries: 1999. Annual Report, Federal Aid to Sport Fish Restoration. N.J. Department of Environmental Protection; Trenton, NJ: 2000. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Bidone ED, Castilhos ZC, Santos TJS, Souza TMC, Lacerda LD. Fish contamination and human exposure to mercury in Tartarugalzinho River, Northern Amazon, Brazil. A screening approach. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1997;97:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bienenfeld LS, Golden AL, Garland EJ. Consumption of fish from polluted waters by WIC participants in East Harlem. J. Urban Health. 2003;80:349–358. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorgo KA, Isley JJ, Thomason CS. Seasonal movement and habitat use by striped bass in the Combahee River, South Carolina. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2000;129:1281–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Bourre JE, Paquotte PM. Contribution of marine and fresh water products (finfish and shellfish, seafood, wild and farmed) to the French dietary intakes of vitamins D and B12, selenium, iodine and docosahexaenoic acid: impact on public health. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008;59:491–501. doi: 10.1080/09637480701553741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim MS, Alam SK, Jenkins LG. Organochlorine pesticides and heavy metals in muscle and ovaries of Gulf Coast Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) from the Apalachicola River, Florida, USA. J. Environ. Sci. Health. 2001;B36:15–27. doi: 10.1081/pfc-100000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. American Indians, hunting and fishing rates, risk and the Idaho. Natl. Eng. Environ. Lab. 1998;80:317–329. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. Consumption advisories and compliance: the fishing public and the deamplification of risk. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 2000;43:471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. Consumption patterns and why people fish. Environ. Res. 2002;90:125–135. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gochfeld M. Mercury and selenium levels in 19 species of saltwater fish from New Jersey as a function of species, size, and season. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;409:1418–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Jeitner C, Donio M, Shukla S, Gochfeld M. Factors affecting mercury and selenium levels in New Jersey flatfish: low risk to human consumers. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2009;72:853–860. doi: 10.1080/15287390902953485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Jeitner C, Gochfeld M. Locational differences in mercury and selenium levels in 19 species of saltwater fish from New Jersey. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2011;74:863–874. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.570231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Pflugh KK, Lurig L, von Hagen LA, von Hagen SA. Fishing in urban New Jersey: ethnicity affects information sources, perception, and compliance. Risk Anal. 1999;19:217–229. doi: 10.1023/a:1006921610468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gaines KF, Gochfeld M. Ethnic differences in risk from mercury among Savannah River fishermen. Risk Anal. 2001a;21:533–544. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.213130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gaines KF, Boring CS, Stephens WL, Jr., Snodgrass J, Gochfeld M. Mercury and selenium in fish from the Savannah River: species, trophic level, and locational differences. Environ. Res. 2001b;87:108–118. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Fleischer J, Gochfeld M. Fish, shellfish, and meat meals of the public in Singapore. Environ. Res. 2003;93:254–261. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(03)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Stern AH, Dixon C, Jeitner C, Shukla S, Burke S, Gochfeld M. Fish availability in supermarkets and fish markets in New Jersey. Sci. Total Environ. 2004;333:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Stern AH, Gochfeld M. Mercury in commercial fish: optimizing individual choices to reduce risk. Environ. Health Persp. 2005;113:266–271. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gochfeld M, Jeitner C, Burke S, Stamm T, Snigaroff R, Snigaroff E, Patrick D, Weston J. Mercury levels and potential risk from subsistence foods from the Aleutians. Sci. Total Environ. 2007a;384:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gochfeld M, Jeitner C, Burke S, Stamm T. Metal levels in Flathead Sole (Hippoglossoides elassodon) and Great Sculpin (Myoxocephalus polyacanthocephalus) from Adak Island, Alaska: potential risk to predators and fishermen. Environ. Res. 2007b;103:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Marek T, Schaefer J, Ellickson K, Barkay T, Reinfelder J. Mercury speciation, reactivity, and bioavailability in a highly contaminated Estuary, Berry’s Creek, New Jersey Meadowlands. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007;41:8268–8274. doi: 10.1021/es070945h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. Seasonal movements of striped bass contingents of Long Island Sound and the New York Bight. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1968;97:320–343. [Google Scholar]

- Contamination Assessment and Reduction Project (CARP) Data Collected by the New York State Department of Environmenal Conservation. Hudson River Foundation; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Reports . American’s Fish: Fair or Foul? Consumers Union; New York: [accessed December 3, 2009]. 2001. Available: ⟨ http://www.mindfully.org/Food/American-Fish.htm⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JJ. Total mercury in fishes and selected biota in Lahontan Reservoir, Nevada. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1983;31:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01608759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump KS, Kjellstrom T, Shipp AM, Silvers A, Stewart A. Influence of prenatal mercury exposure upon scholastic and psychological test performance: benchmark analysis of a New Zealand cohort. Risk Anal. 1998;18:701–713. doi: 10.1023/b:rian.0000005917.52151.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizdziel JV, Hinners TA, Pollard JE, Heithmar EM, Cross CL. Mercury concentrations in fish from Lake Mead, USA, related to fish size, condition, trophic level, location, and consumption risk. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002;43:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s00244-002-1191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizdziel J, Hinners T, Cross C, Pollard J. Distribution of mercury in the tissues of five species of freshwater fish from Lake Mead, USA. J. Environ. Monit. 2003;5:802–807. doi: 10.1039/b307641p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviglus M, Sheeshka J, Murkin E. Health benefits from eating fish. Commun. Toxicol. 2002;8:345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, May MD, Greenfield BK, Fairey R, Roberts C, Ichikawa G, Stoelting MS, Becker JS, Tjeerdema RS. Contaminant concentrations in sport fish from San Francisco Bay, 1997. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002;44:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, Greenfield BK, Ichikawa G, Stephenson M. Mercury in sport fish from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta region, California, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;391:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MA. Effects of long-term mercury exposure on hematology of Striped Bass, Morone saxatilis. Fish. Bull. 1982;80:389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler R. Selenium Hazards to Fish, Wildlife and Invertebrates: A Synoptic Review. Washington, DC: 1985. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Report 85(1.5). Contaminant Hazard Review No. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler R. Mercury Hazards to Fish, Wildlife, and Invertebrates: A Synoptic Review. Washington, DC: 1987. US Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 85(1.10). Contaminant Hazard Review No. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Emery EB, Spaeth JP. Mercury concentrations in water and hybrid striped bass (Morone saxatilis × M. chrysops) muscle tissue samples collected from the Ohio River, USA. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011;60:486–495. doi: 10.1007/s00244-010-9558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental protection Agency (EPA) [accessed 15 November 2009];Water Quality Criterion for the Protection of Human Health: Methylmercury. 2001 EPA-823-R-01-001. ⟨ http://www.epa.gov/waterscience/criteria/methylmercury/pdf/mercury-criterion.pdf⟩.

- Fairey R, Taberski K, Lamerdin S, Johnson E, Clark RP, Downing JW, Newman J, Petreas M. Organochlorines and other environmental contaminants in muscle tissues of sportfish collected from San Francisco Bay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1997;34:1058–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald WF, Lyons WB. Organic mercury compounds in coastal waters. Nature. 1973;242:452–453. doi: 10.1038/242452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [accessed 15 November 2009];FDA Consumer Advisory. 2001 Available: ⟨ http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm110591.htm⟩.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [accessed 15 Novembery 2009];What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish—March 2004: 2004 EPA and FDA Advice For: Women Who Might Become Pregnant Women Who are Pregnant Nursing Mothers Young Children. 2004 ⟨ http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm110591.htm ⟩ .

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish. Food and Drug Administration; Washington, DC: [accessed 15 November 2009]. 2005. ⟨ http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/Seafood/FoodbornePathogensContaminants/Methylmercury/ucm115644.htm ⟩ . [Google Scholar]

- Furness RW. Cadmium in birds. In: Beyer WN, Heinz WN, Redmon-Norwood AW, editors. Environmental Contaminants in Wildlife: Interpreting Tissue Concentrations. Lewis Publishers; Boca Raton, FL: 1996. pp. 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ganther HE, Goudie C, Sunde ML, Kopecky MJ, Wagner R, Sang-Hwang OH, Hoekstra WG. Selenium relation to decreased toxicity of methylmercury added to diets containing tuna. Science. 1972;72:1122–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4026.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore CC, Riedel GS. A survey of size-specific mercury concentrations in fame fish from Maryland fresh and estuarine waters. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2000;39:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s002440010079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg GL, Toal BF. Development of a single-meal fish consumption advisory for methylmercury. Risk Anal. 2000;20:41–47. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobeille AK, Morland KV, Bopp RF, Godbold JH, Landrigan PJ. Body burdens of mercury in lower Hudson River area anglers. Environ. Res. 2006;101:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochfeld M. Cases of mercury exposure, bioavailability, and absorption. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2003;56:174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0147-6513(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochfeld M, Burger J. Good fish/bad fish: a composite benefit-risk by dose curve. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F, Araki S, Yokoyama K, Murata K, Sorenson N, Jorgensen PJ. Cognitive deficit in 7-year old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1997;19:418–428. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green NW, Knutzen J. Organohalogens and metals in marine fish and mussels and some relationships to biological variables at reference localities in Norway. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003;46:362–377. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield BK, Davis JA, Fairey R, Roberts C, Crane D, Ichikawa G. Seasonal, interannual, and long-term variation in sport fish contamination, San Francisco Bay. Sci. Total Environ. 2005;336:25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig RA, McGrath RA. Trace metals in sediments of Raritan Bay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1977;8:188–192. [Google Scholar]

- Grothues T. Striper tracker program. Jersey Shoreline. 2008;25:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guallar E, Sanz-Gallardo MI, van’t Veer P, Bode P, Aro A, Gomez-Aracena J. Heavy metals and Myocardial Infarction Study Group: mercury, fish oils, and the risk of myocardial infarction. New Eng. J. Med. 2002;347:1747–1754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt CR, Fitzgerald WF. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of methylmercury in Long Island Sound. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006;51:416–424. doi: 10.1007/s00244-005-0265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper BL, Harris SG. A possible approach for setting a mercury risk-based action level based on tribal fish ingestion rates. Environ. Res. 2008;107:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SG, Harper BL. Native American exposure scenarios and a tribal risk model. Risk Anal. 1998;17:785–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1997.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SG, Harper BL. Using eco-cultural dependency webs in risk assessment and characterization of risks to tribal health and cultures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2000;2:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman KJ, Brandt SB. Predatory demand and impact of striped bass, bluefish, and weakfish in the Chesapeake Bay: applications ob bioenergetic models. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1995;52:1667–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Hightower JM, Moore D. Mercury levels in high-end consumers of fish. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111:604–608. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hites RA, Foran JA, Carpenter DO, Hamilton MC, Knuth BA, Schwager SJ. Global assessment of organic contaminants in farmed salmon. Science. 2004;303:226–229. doi: 10.1126/science.1091447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff TB, McLaren JB, Cooper JC. Science, Law and Hudson River Power Plants. American Fisheries Society; Bethesda, Maryland: 1988. Stock Characteristics of Hudson River Striped Bass; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Seafood Safety. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and Risks. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JG, Birks E, Heisinger JF. Protective action of selenium against mercury in northern creek chubs. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1977;17:132–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01685539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan PJ, Golden AL, Simpson HJ. Toxic substances and their impacts on human health in the Hudson River watershed. In: Waldman JR, editor. The Hudson River Estuary. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lange TR, Royals HE, Connor LL. Mercury accumulation in Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) in a Florida Lake. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1994;27:466–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00214837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand M, Arp P, Ritchie C, Chan HM. Mercury exposure in two coastal communities of the Bay of Funday, Canada. Environ. Res. 2005;98:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinton JS, Pochron ST. Temporal and geographic trends in mercury concentrations in muscle tissue in five species of Hudson River, USA, fish. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008;27:1691–1697. doi: 10.1897/07-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RP, Heyes D, Sveinsdottir A. Methylmercury concentrations in fish from tidal waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006;51:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s00244-004-0230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie CL., Jr. The Fisheries of Raritan Bay. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews T, Fisher NS. Evaluating the trophic transfer of cadmium, polonium, and methylmercury in an estuarine food chain. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008;27:1093–1101. doi: 10.1897/07-318.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC) Toxicological Effects of Methylmercury. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nemerson DM, Able KW. Spatial and temporal patterns in the distribution and feeding habits of Morone saxatilis in marsh creeks of Delaware Bay, USA. Fish Manage. Ecol. 2003;10:337348. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman MJ, Ruess G, Able KW. Species composition and food habits of dominant fish predators in salt marshes of an urbanized estuary, the Hack-ensack Meadowlands, New Jersey. Urban Habitats. 2004;2:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Monitoring Program for Chemical Contaminants in Fish from the State of New Jersey. NJDEP; Trenton, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- New York/New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program . An Analysis of Environmental Indicators for the NY/NJ Harbor Estuary. NYNJ Harbor Estuary Program; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation . Hudson Basin Biota Database on Contaminants. Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation; Albany, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ng CL, Able KW, Grothues TM. Habitat use, site fidelity, and movement of adult striped bass in a southern New Jersey estuary based on mobile acoustic telemetry. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2007;136:1344–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Park JG, Curtis LR. Mercury distribution in sediments and bioaccumulation by fish in two Oregon reservoirs: point-source and nonpoint source impacted systems. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1997;33:423–429. doi: 10.1007/s002449900272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J. Introduction—comparative dietary risk: balance the risks and benefits of fish consumption. Commun. Toxicol. 2002;8:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Pakkala IS, Gutenmann WH, Lisk DJ, Durdick GE, Harris EJ. A survey of the selenium content of fish from 49 New York state waters. Pest Monit. J. 1972;6:107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SA, Ralston NV, Peck DV, Van Sickle J, Robertson JD, Spate VL, Morris JS. How might selenium moderate the toxic effects of mercury in stream fish of the western U.S.? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;15:3919–3925. doi: 10.1021/es803203g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho AP, Guimaraes JRD, Marins AS, Costa PAS, Olavo G, Valentin J. Environ. Res. 2002;89:250–258. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone N, Mahaffey KR. Dynamics of Mercury Pollution on Regional and Global Scales: Atmospheric Processes and Human Exposures Around the World. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. Where we stand on mercury pollution and its health effects on regional and global scales; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Raney EC. The life history of the Striped Bass, Roccus saxatilis (Walbaum) Bull. Bingham Ocean Collect. (Yale University) 1952;14:5–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston NV. Selenium health benefit values as seafood safety criteria. Ecohealth. 2009;5:442–455. doi: 10.1007/s10393-008-0202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston NV, Raymond LJ. Dietary selenium’s protective effects against methylmercury toxicity. Toxicology. 2010;28:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Jessop BM, Coffin J, Swetnam DA. Mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls in striped bass (Morone saxatilis) from two Nova Scotia Rivers. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1984;21:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reiger G. The Striped Bass Chronicles. Lyons Press; Guilford CT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhode Island Department of Health [accessed 15 November 2009];Mercury in Fish. 2009 ⟨ www.health.state.ri.us/environment/risk/fish.php ⟩ .

- Rice G, Swartout J, Mahaffey K, Schoeny R. Derivation of U.S. EPS’s oral Reference Dose (RfD) for methylmercury. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2000;23:41–54. doi: 10.1081/dct-100100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringdal O, Julshamn K. Effect of selenite on the uptake of methylmercury in Cod (Gadus morhua) Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1985;35:335–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01636519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]