Abstract

The growth in home health care in the United States since 1970, and the exponential increase in the provision of Medicare-covered home health services over the past 5 years, underscores the critical need to assess the effectiveness of home health care in our society. This article presents conceptual and applied topics and approaches involved in assessing effectiveness through measuring the outcomes of home health care. Definitions are provided for a number of terms that relate to quality of care, outcome measures, risk adjustment, and quality assurance (QA) in home health care. The goal is to provide an overview of a potential systemwide approach to outcome-based QA that has its basis in a partnership between the home health industry and payers or regulators.

Purpose

Certain terms, such as outcomes, case mix, indicators, and measures, have multiple meanings in the literature, and therefore are defined precisely in this article to frame the discussion on quality measurement and QA in home health care. Many of the concepts and issues discussed apply to health care in general, although they are anchored largely in their applicability to long-term care and especially home health care.

Primary emphasis is on patient outcomes and measuring outcomes for QA Nonetheless, general issues related to quality of care, as well as the utility of other types of quality measures, are presented. For the most part, we concentrate on selected results from the conceptual, clinical, and empirical analyses that have constituted a research program designed to produce a system of outcome measures for use in assessing the effectiveness of home care.

The various studies that have comprised this program have afforded an opportunity to evaluate the appropriateness of most major secondary data sources and agency-obtained data for measuring outcomes, assess the feasibility of different approaches to primary data collection, obtain input from multidisciplinary clinical panels on the content and methodology of proposed methods for measuring the quality of home health care, and empirically test several different measurement approaches (Kramer et al., 1989a; Shaughnessy, Kramer, and Bauman, 1989; Kramer et al., 1989b; Crisler, Kramer, and Shaughnessy, 1990; Shaughnessy et al., 1991a; Shaughnessy et al., 1993).

Centrality of Outcomes

Our primary reason for providing health care is to benefit patients. In the context of analyzing issues about reimbursement, utilization, regulation, supply, integration, insurance coverage, health professions' education, cost, and even political topics, it is possible for us to overlook the basic fact that the raison d'être of health care is to influence patient outcomes. At a time when health policy and health services issues are receiving considerable attention and form the basis for extensive policy debate, the effectiveness of the many components of our health care system, taken individually and holistically, is not being measured and analyzed adequately in view of what is at stake. Does hospital care accomplish what it should on behalf of patients? Do we have adequate evidence of the outcomes of systematic approaches to managed care based on data collected on individual patients or health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollees? Is home care more effective than institutional care? In terms of what happens to patients, is primary care as effective and as logical as its proponents argue? Have the regulatory programs put in place in nursing homes over the past 2 decades enhanced the well-being of nursing home residents?

We have made inroads into answering some of these questions, but are far from definitive evidence. One reason is that we often analyze utilization patterns, provision of services, distribution or supply of providers, organizational arrangements, and cost and reimbursement issues (to name a few) on the assumption that the care provided accomplishes what we expect. This assumption has not been challenged with sufficient objectivity and intensity, although there are several studies and analyses that have addressed and are continuing to address such issues (Grover et al., 1990; Hannan et al., 1989; Hughes et al., 1988; Shaughnessy, Schlenker and Kramer, 1990; Carlisle et al., 1992; Wennberg, 1990; Tarlov et al., 1989; Braun, Rose, and Finch, 1991; Park et al., 1990; Dubois and Brook, 1988; Shaughnessy et al., 1994; Helberg, 1993; Kemper et al., 1988; Kemper, 1992; Hedrick and Inui, 1986; Hughes, 1985; Zimmer, Groth-Juncker, and McCusker, 1985). In all, when examining the value or effectiveness of care, outcomes should be considered as more than one small piece of the entire setting; they should occupy center stage because they are the fundamental reason why we provide health care.

There are several reasons outcomes have not been comprehensively analyzed in addition to the rather obvious ones of limited resources and funding for such purposes. It is difficult to precisely specify outcome measures to properly adjust for the natural progression of disease or disability in analyzing outcomes, and to reliably and comprehensively collect the requisite data to properly analyze outcomes. Yet, analysis of what we are accomplishing on behalf of patients is likely to provide highly useful information to assist us in refining and possibly even substantially altering our approach to health care in the United States. Home health care is no exception. We know little about the effectiveness of home health care, although we are aware of the strong preference patients have for home care over most other alternatives, especially institutional care. Our challenge is to specify and measure outcomes in the home care field so that we might learn more about effectiveness, facilitate decision-making on what types of patients or clients benefit most from home care, and provide a foundation for continually improving the effectiveness or outcomes of home care.

Background

In the long-term care field, a distinction is often drawn between quality of care and quality of life (Donabedian, 1980). In a general sense, the term “quality of life” refers to the extent to which an individual is able to and does pursue a range of functional, intellectual, emotional, and volitional behaviors that constitute and enhance the total life experience. Quality of life is perforce uniquely circumscribed for each individual by those features of one's health status and environment that are (relatively) immutable at a given point in time, such as age, birth circumstances, heredity, acquired disabilities, selected socioeconomic factors, and family composition and history. The term “quality of care” is typically used in a more specific way, connoting the adequacy or effectiveness of health care, and, at times, access to or appropriateness of health care. Without doubt, health care can and does influence quality of life. For selected types of long-term care, quality of life can be an indicator of the effectiveness of care, e.g., nursing home care and home care for the chronically ill (Patrick, 1990; Institute of Medicine, 1986).

In a temporal sense, quality of care can be conceptualized as focusing on the adequacy or effectiveness of a set of services provided within a given period of time or episode of health care. We have yet to reach a point in comprehensively evaluating health care where we truly view quality of life as a function of multiple, integrated episodes of health care (and other factors and services) over extended periods of time. We must continue to strive for such comprehensive evaluations (which may become more likely if care integration is enhanced under managed care systems and such systems collect adequate information to monitor health status outcomes). In the meantime, to take steps toward attaining this goal, it is appropriate to define, study, and assess quality of care for individual types of providers, continually expanding the purview of such efforts to include the effectiveness of care over increasing intervals of time.

In this context, this article is concerned with measuring the effectiveness of home health care. Different types of effectiveness measures, defined largely in terms of patient outcomes, are discussed. Home care is unique in several ways that make it complex to attribute outcomes to the care provided. Patient compliance or adherence to treatment regimen is critical, yet is difficult to monitor. The provider is essentially a guest of the patient. Attributes of the home environment, such as stairways, availability of transportation, language barriers, availability of communications technology, and presence of a willing and able caregiver are often essential in determining independence, improvement, or maintenance of function. To remain at home instead of in an institutional setting, most patients1 require at least some degree of independence in terms of the cognitive, behavioral, and functional components of activities of daily living (ADLs). Although some home care patients can be severely and permanently impaired in these areas and still remain at home, they are the exception rather than the rule, because serious and enduring impairments in such areas usually result in institutional care.

Nonetheless, most of us would prefer home care not only for ourselves but also for our families and friends when confronted with a viable choice between home care and institutional long-term care. This reason alone—the desirability of home care over institutional long-term care—very likely accounts for a major portion of the growth in the home care field over the past 2 decades (Kemper, 1992; Rivlin and Weiner, 1988; McAuley and Blieszner, 1985). Is home care effective, however? How do we measure effectiveness? Can we establish ways to assess and improve effectiveness over the course of time? How are continuous quality improvement (CQI) or total quality management (TQM) methods best implemented and sustained in the home care field? Third-party payers are understandably asking whether home care is more cost-effective than other types of health care, seeking to ascertain the circumstances under which home care is effective, and attempting to discern the types of agencies and even the individual agencies that are most effective. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-203) mandated that the Medicare survey and certification process shift from an emphasis on structural requirements to an evaluation of the care provided to patients and its effectiveness.

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has initiated efforts to develop outcome indicators to assess effectiveness of health care organizations (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 1988a). JCAHO requires “the identification of defined, measurable indicators of the quality and appropriateness of each important aspect of care, that specify activities, events, occurrences and/or outcomes” (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 1988b). Another accrediting body, the Community Health Accreditation Program (CHAP) of the National League for Nursing, has as a primary objective to “develop and maintain state-of-the-art consumer-oriented national standards of excellence focusing on outcomes for the full range of services and products provided by home care and community health organizations” (Community Health Accreditation Program, 1989).

A number of recent developments further demonstrate the considerable current interest in home health outcomes and the effects of care provided. Outcome scales developed for the Home Care Association of Washington include general symptom distress, functional status, caregiver strain, discharge status, taking medications as prescribed, patient satisfaction, knowledge of major health problems, and physiologic indicators (Lalonde, 1986). The Visiting Nurse Association of Omaha developed and empirically tested a QA system with a problem rating scale to measure clients' knowledge, behavior, and status outcomes for specific problems (Martin, Leak, and Aden, 1992). The Alberta Home Care Program used a client outcome tool to measure: pain management; symptom control; physiologic health status; ADL abilities; instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) abilities; sense of well-being; goal attainment; maintenance at home; knowledge of diagnosis, treatment, management, and safety; performance of prescribed treatments and management regimens; satisfaction with services; and family strain (Sorgen, 1986). Kane et al. (1991) assembled panelists to rank the importance of different types of quality indicators. Rinke (1988) developed a framework for home care agencies to use in defining and measuring home care outcomes. A system developed by Wilson (1993) focuses on measures of patient functional status (defined as encompassing health, knowledge, skill, psychosocial function, and ADLs) to generate data on patient outcomes, individually and in the aggregate. A home health care classification system for nursing diagnoses and interventions for home health care patients was developed at Georgetown University to measure, analyze, and predict resource requirements (Saba and Zuckerman, 1992). Recently concluded research was conducted by CHAP to assess outcomes and to incorporate appropriate measures into the CHAP accreditation process. The study used three levels of outcomes: individual, intra-agency, and interagency outcomes (Peters, 1992).

Definitional and Methodological Considerations

Quality Criteria, Natural Progression, and Outcomes of Care

The challenge of measuring quality of care is as multifaceted as measuring individual health status using the dimensions of physiologic, functional, mental, social, and emotional health. A practical (single-valued) overall or global index of health status is simply not possible, or at least has not been developed to date. Necessity thus dictates that we consider the attributes of health status as multidimensional rather than unidimensional in assessing the effectiveness of health care. Quality care can be defined using any combination of three well-known criteria attributable to Donabedian (1980):

(1) Quality of care defined in terms of outcomes

Quality care should result in benefits to a patient that would not accrue in the absence of care.

(2) Quality of care defined in terms of process

Quality care should be consistent with or superior to the dictates of accepted standards that specify how care should be provided.

(3) Quality of care defined in terms of structure

Quality care should be consistent with or superior to the dictates of accepted standards that specify either resources that should be used or the characteristics of the environment in which care should be provided.

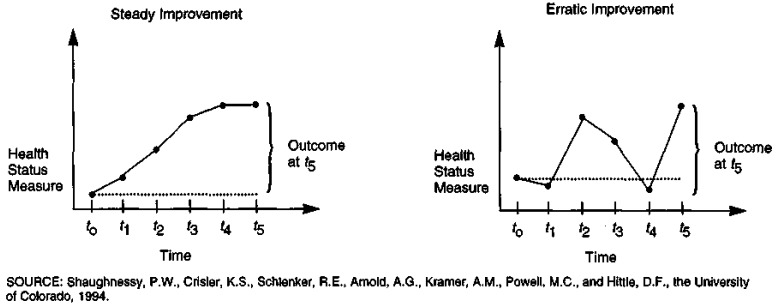

Although outcomes are defined more precisely in the next section, consider for the moment that the type of outcome under consideration is a change in patient health status over time (e.g., healing of a surgical wound or improvement in ability to dress the lower body after a stroke). Conceptually, it is necessary to distinguish between an outcome and an outcome of care. As shown on the left side of Figure 1, an outcome, as defined here, refers to the change in health status between a baseline time point (t0) and a final time point (tf). However, some or all of the change in health status (e.g., wound healing or improvement in ability to dress lower body) may have occurred independently of care provided. Some natural progression of condition would have occurred by the followup time point (e.g., for wound healing or recovery of function). The diagrams on the left and right sides of Figure 1 depict the difference between the patient outcome and the outcome of care. The outcome of care can be considered as that portion of the outcome that is attributable to care independently of natural progression of the condition.

Figure 1. Outcomes as a Function of Antecedent Care and Natural Progression of Condition (Disease or Disability).

The challenge in measuring outcomes to assess effectiveness of health care is to somehow consider both the natural progression of condition (even when condition might deteriorate) and the care provided. In this context, we must also acknowledge and compensate for the possibility that good care should minimize the likelihood of complications that might have occurred in the absence of care. (Complications are circumstances that can influence outcomes or be considered outcomes unto themselves, e.g., wound infection or a second stroke.) Sometimes care is intended to do no more than make the patient more comfortable or enhance the natural progression of patient condition (e.g., terminal care or wound healing). Figure 1 is not intended to depict all possible situations, because (a) natural progression can be neutral or even negative; (b) care can be provided only to accelerate, not necessarily permanently elevate, health status to a level above that of natural progression; and (c) change in health status need not be linear or monotonic (i.e., change can occur in a nonlinear fashion and even worsen and improve over a given interval). The main point of Figure 1 is simply to demonstrate that outcomes are a function of both antecedent care and natural progression of condition.

Because the objective in outcome assessment is attributing outcomes to antecedent care, and because it is typically not possible to precisely separate the effects of natural progression from antecedent care, statistical comparisons are often useful in evaluating outcomes. Such comparisons usually entail measuring outcomes for a patient group under one set of circumstances (e.g., under the care of a given provider) and comparing such outcomes with those of another patient group, assuming that the natural progression for both groups is the same, or adjusting for potential differences in natural progression by measuring factors that predict natural progression and compensating for these factors in the analysis. Such factors are typically termed risk-factors or case-mix variables (discussed later). Comparing outcomes between the two groups theoretically compensates for potential differences in natural progression if the risk factor-adjustment process is thorough. As will be discussed, this is rarely possible to do perfectly. However, on the assumption that risk (factor) adjustment is adequate for practical purposes, the differences in risk-adjusted outcomes between the two groups can be attributed to antecedent care and are therefore regarded as differences in outcomes of care.

Time Interval Over Which Outcomes Are Measured

Duration between the baseline time point and the followup time point(s) is important to consider when assessing outcomes. Figure 2 (in which change in health status is depicted as non-linear for the sake of generality) demonstrates that change in health status at an interim time point (ti) can be attributed to both antecedent care (effect “a”) and natural progression (effect “b”). However, a substantial portion of the change in health status at the final time point (tf), effect “d,” would have occurred without providing the antecedent care. Thus, most of the change in health status over the interval between t0 and tf would have occurred independently of care provided (in this example), whereas the natural progression at ti was considerably enhanced by care provided between t0 and ti. In this case, the provision of care accelerated improvement in health status, but produced a relatively small lasting effect on health status (effect “c”) relative to that which would have occurred through natural progression. No matter what final time point is selected to measure outcomes, the dilemma of the “truly final effect” persists from a theoretical viewpoint. For example, in a recent study to examine home care provided under fee-for-service and capitated payment environments (HMOs), the final followup point was 12 weeks or discharge, whichever occurred first. A risk-adjusted difference between the two payment environments was found for several outcomes, suggesting superior outcomes for fee-for-service patients. However, it is possible that by 6 months after admission to home care, the HMO patients may have attained outcomes similar to the fee-for-service patients because of either natural progression or other types of care provided. Patients were not followed this long; hence, data were not collected to test this hypothesis because the goal was to assess the shorter run effectiveness of home health care independently of the confounding effects of other types of health care (Shaughnessy, Schlenker, and Hittle, 1994). Consequently, the time interval must be carefully selected in view of the purpose at hand, considering the possibility that as the duration of time from the initial baseline point increases, the likelihood of additional types of care increases, complicating the attribution of outcomes to a particular type of antecedent care.

Figure 2. Potential Differential Effects of Outcomes of Care Relative to Timing of Followup Observations.

The diagram in Figure 2 also demonstrates that the primary or even exclusive effect of certain types of care can be in the form of acceleration of natural progression. However, this should not be considered a trivial type of effect, because in some instances it is highly desirable. For example, an accelerated return to a former level of functioning can substantially reduce home caregiver strain, allow an individual to return to work (or other former activities) earlier, or avoid complications that might be more probable if the recovery period is longer (e.g., risk of hospitalization is greater if a normally ambulatory individual is sufficiently impaired in mobility so that the likelihood of falling is increased).

Patterns of Change Over Time

The diagram on the left in Figure 3 demonstrates a steady improvement in health status over several time points. This pattern contrasts substantially with that on the right in Figure 3 where, although patient status improves between t0 and t5, two declines in health status (relative to t0) occur at interim times.

Figure 3. Outcomes in the Context of the Pattern of Change in Health Status.

To test for different conclusions that might be reached by examining outcomes measured using only a baseline and a single followup point relative to outcomes defined using information from several interim time points, we defined the following four types of outcome measures:

(4) Improvement in health status

If the patient's health status (e.g., measured using an ordinal scale for ambulation) improves between admission and the final followup point, this outcome measure takes on the value 1; otherwise it is 0. Patients who cannot improve (are not disabled relative to the health status measure under consideration, or do not have the condition or problem) are excluded from the computation of this measure.2 Patients who died during the followup interval are also excluded.3

(5) Improvement pattern in health status

If the patient's health status improves between admission and the final followup point for the health status measure under consideration, and does not worsen relative to health status at admission for any interim data collection points, this outcome measure takes on the value 1; otherwise it is 0. Exclusions are the same as those above.

(6) Stabilization in health status

If the patient's health status does not worsen between admission and the final followup point, this outcome measure takes on the value 1; otherwise it is 0. Patients who cannot worsen (are at the most severe level of the health status scale under consideration) are excluded from the computation of this measure. Patients who died during the followup interval are also excluded.

(7) Stabilization pattern in health status

If the patient's health status does not worsen between admission and the final followup point for the health status measure under consideration, and does not worsen relative to health status at admission at interim data collection points, this outcome measure takes on the value 1; otherwise it is 0. Exclusions are the same as above.

The improvement and stabilization measures in (4) and (6) use only the first and final time points (and sometimes are called “difference” measures here), whereas the improvement pattern and stabilization pattern measures in (5) and (7) use interim time points as well.

To assess the value of the information on patient status at interim time points, we used data from a national sample of home health agencies and patients to compare means on the improvement and stabilization difference measures with those of the improvement and stabilization pattern measures for Medicare patients admitted to home health care from a hospital versus those admitted from the community (Table 1). Because the outcome measures are dichotomous, all means can be interpreted as percents. As expected, because the pattern measures are more stringent in that a patient cannot worsen at interim time points to receive a value of “1,” the means for the two pattern measures are respectively lower than the means for the improvement and stabilization difference measures. The means for the community patients tend to be somewhat lower, conveying the greater likelihood of chronic functional impairments among patients admitted to home care from the community relative to hospital patients, who are more likely to have acute problems where functional stabilization and improvement are more probable.

Table 1. Functional Outcomes at Three Months After Start of Care for 2,622 Medicare Home Health Patients Admitted From Hospital (1,905 Patients) or From Community (717 Patients)1.

| Functional Outcomes | Admitted From Hospital2 (n = 1,905) |

Admitted From Community2 (n = 717) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Improvement3 | Stabilization3 | Improvement3 | Stabilization3 | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Difference4 | Pattern4 | Difference | Pattern | Difference | Pattern | Difference | Pattern | |

| Ambulation | .356 | .350 | .905 | .875 | .262 | .252 | .848 | .796 |

| Transferring | .505 | .502 | .913 | .889 | .343 | .343 | .885 | .842 |

| Toileting | .487 | .470 | .923 | .904 | .379 | .369 | .893 | .868 |

| Bathing | .539 | .517 | .883 | .838 | .365 | .354 | .786 | .745 |

| Dressing Lower Body | .523 | .509 | .889 | .859 | .306 | .293 | .866 | .819 |

| Grooming | .532 | .515 | .914 | .882 | .404 | .386 | .886 | .854 |

| Main Meal Preparation | .423 | .407 | .820 | .773 | .325 | .313 | .759 | .695 |

| Housekeeping | .350 | .343 | .814 | .757 | .273 | .264 | .704 | .652 |

The 2,622 patients were randomly sampled from Medicare admissions to 44 certified agencies in 27 States during 1991 and 1992. Patients were followed longitudinally with data collection occurring monthly until 3 months after start of care or until discharge, whichever occurred first. Data were collected prospectively using an optical scan form containing data items that had been piloted and reliability tested in earlier field trials.

To be admitted from hospital, it was necessary for the patient to be discharged from an acute inpatient stay within 14 days prior to home health admission.

All hospital versus community mean differences between improvement (difference and pattern) outcome measures and between stabilization (difference and pattern) outcome measures, respectively, are statistically significant (p < .10) using Fisher's exact test or its chi-square approximation when expected cell frequencies are ≥ 5. For example, the mean difference between the improvement pattern outcome measure in ambulation for hospital patients and the improvement pattern outcome measure in ambulation for community patients is significant at p < .10.

The difference and pattern measures are defined in the text for improvement (definitions [4] and [5] and stabilization definitions [6] and [7]).

SOURCE: Random samples of Medicare patients, 1991-92.

However, the respective findings for the four types of measures tend to lead to consistent inferences in comparing home health patients admitted from hospitals with those admitted from the community. That is, the excess of the improvement difference mean for hospitalized patients over those for community patients tends to be about the same as the corresponding excess for the improvement pattern means, and analogously for the stabilization measures. Although this consistency between difference measures and pattern measures is not always found, it has appeared quite frequently in our research using interim time points separated by 30-day intervals. Because of this, and because of the substantially increased burden of data collection at interim time points, we would recommend data collection every 60 days for (Medicare) home health patients, because it appears the more relevant conclusions regarding outcomes can be obtained using a 60-day interval. Thus, in terms of outcome-based quality improvement (OBQI), our recommendation is to collect data every 60 days until discharge, and to collect data at discharge, whenever it occurs.

Three Types of Outcomes

Several definitions are appropriate at this stage to introduce end-result, intermediate-result, and utilization outcome measures as a taxonomy for outcome measurement that is useful for OBQI in home health care. The following first six definitions (8)-(13) provide a backdrop for defining the three types of outcome measures in (14)-(16), as well as for discussing other issues and approaches in this article.

(8) Quality of care

As used here, the term “quality of care” refers to a broad construct, which, in full generality, is a pervasive attribute of health care, reflecting the overall effectiveness with which health care is provided relative to its primary attributes or its objective(s) to cure, rehabilitate, assess, maintain, sustain, or palliate (patients), or to ameliorate, prevent, or retard patient problems. It is presumed that each type of (home) care has certain objectives. Quality of care refers to the extent to which these objectives are attained. When one speaks of quality of care, an implicit assumption is made that standards exist according to which the “goodness” or “badness” of care can be judged. Such standards can take the form of either expert-opinion-derived norms, or implicit or explicit statistical norms reflecting the state of care provided at a given time. By definition, “quality of care” connotes a positive attribute of care, i.e., the higher the quality, the more beneficial it is for the patient.

(9) Quality indicator

The term “quality indicator” also refers to a construct, i.e., an attribute of care that is conceptual or more theoretical in nature (not yet translated into a concrete attribute that is rigorously and precisely defined). A quality indicator refers to an attribute of care that can be used to gauge quality of care in a specific area. For example, the degree of improvement in patient functioning—not necessarily specifying how one should actually measure patient functioning—is a quality indicator or construct that can reflect the quality of care with respect to patient functioning. Thus, the term “quality of care” is a broad overarching construct, whereas the term “quality indicator” refers to a more specific construct that involves a particular dimension of quality of care. As used here, the term “quality indicator” is distinct from the term “quality measure.”

(10) Quality measure

A quality measure results from a rule that assigns numeric values to a specific quality indicator. The essential distinction between quality indicators and quality measures (in this discussion) is that quality measures take on numeric values, while quality indicators refer only to unquantified attributes of care related to quality. For example, improvement in ambulation is a quality indicator. Improvement in ambulation as quantitatively reflected by the numeric change in a five-point ordinal mobility scale between admission and 60 days after admission is a quality measure. (One reason we often distinguish between quality indicators and quality measures in our research is that, operationally, certain types of clinicians and clinical panels are effective in developing and reviewing quality indicators, whereas other types of panels are effective in developing and reviewing quality measures.) Therefore, a quality measure takes on “values” (i.e., numbers), but is clinically and conceptually rooted in a quality indicator that is an unquantified attribute of care reflecting one of many components of the overarching construct of quality of care. Depending on how they are defined, quality measures and quality indicators can reflect either good care or poor care.

(11) Process quality measure

A process quality measure is one that quantifies one or more dimensions of the manner in which care is actually provided or administered. For example, a process quality measure can quantify services according to a dichotomy of whether a given service is provided (0 = not provided, 1 = provided), the provider of service (different values for different types of individual service providers by discipline or professional type), the frequency of service (a numeric value indicating the number of times the service is provided per week, per month, etc.), the mix of services provided (a numeric value or set of values indicating whether prespecified health care services are provided in conjunction with one another), a composite score indicating the adequacy with which several dimensions of a service (e.g., assessment) were provided, etc. To be valid, process measures of quality must be appropriately linked to care needs of the patients under consideration and must produce intended outcomes.

(12) Structural quality measure

A structural quality measure is one that reflects the availability of needed care or resources, the adequacy of inputs to the service process such as staff or equipment, or the care environment associated with service provision. For example, structural quality measures can include dichotomies reflecting the availability of certain devices (e.g., walker, cane, or other types of durable medical equipment) needed for functioning or rehabilitation, a quantification of the overall staff mix available through a home health agency in view of its case mix, etc.

(13) Outcome measure

An outcome measure is a quantification of a (potential) effect of care on the patient For example, a dichotomous measure indicating whether a wound has healed between admission and 2 months after admission, a dichotomy indicating whether a patient was hospitalized due to complications of care, a quantification of whether a patient or home caregiver is satisfied with care received, a quantification of whether a home health patient or the home caregiver has become more knowledgeable about certain aspects of self-care, or a dichotomy measuring whether a surgical wound became infected, are outcome (quality) measures. For purposes of this discussion, we have subdivided outcome measures into the three-category taxonomy defined below.

(14) End-result outcome measure

An end-result outcome measure reflects a quantified change in patient condition that is (potentially) due to the provision of care. End-result outcomes refer to changes and non-changes in functional abilities, physiologic conditions, symptom distress, cognitive abilities, or emotional conditions that are intrinsic to the patient For example, a quantification of change in transferring ability between admission and discharge, a quantification of change between admission and 60 days after admission in terms of dependence on intravenous medication (i.e., where the physiologic condition in this case is reflected by this dependency), and a quantification of change in symptom distress (e.g., pain present or absent) are end-result outcome measures.

(15) Intermediate-result outcome measure

An intermediate-result outcome measure reflects a quantified non-physiologic or non-functional outcome of care that is intrinsic to the patient, the patient's family or caregiver, or their behavior; however, the intermediate-result outcome is not the primary reason for, or the intended end result of, the care provided. For example, quantifications of the extent to which patients or caregivers are compliant with a medication regimen, a quantification of satisfaction with personal care services, or a dichotomy reflecting change in the extent of family or caregiver strain are intermediate-result outcome measures. Intermediate-result outcome measures are important in home care, where patient knowledge of self-care, compliance with treatment regimen, caregiver strain, and satisfaction can be pivotal in attaining certain end-result outcomes.

(16) Utilization outcome measure

Also referred to as a surrogate end-result outcome measure, a utilization outcome measure is a quantification of health services use (or non-use) that is potentially attributable to the (home) health care under consideration. Illustrations of utilization outcome measures include dichotomous indicators of admission to inpatient hospital care due to specific complications and dichotomies reflecting unscheduled physician visits for specific reasons.

As noted, the previous terms are not used consistently in the literature and it is therefore useful to define them for purposes of this discussion. The first six terms previously defined (quality of care, quality indicator, quality measure, process quality measure, structural quality measure, and outcome [quality] measure) were introduced earlier at least in heuristic terms, and are not discussed further per se.

The final three terms above that reference end-result, intermediate-result, and utilization outcome measures are important to note because they constitute a useful three-category outcome measure taxonomy for home health care. In brief, end-result outcomes refer to actual changes in patient status over time; intermediate-result outcomes refer to changes in patient/family caregiver knowledge, compliance, satisfaction, and (caregiver) strain or stress; and utilization outcomes refer to the use (or non-use) of health services (e.g., hospitalization) that are potentially attributable to the (home) health care under consideration. Utilization outcomes have been used more frequently than end-result or intermediate-result outcomes, because data are more readily available on such outcomes from secondary sources. However, as noted in the definition, utilization outcome measures are actually surrogate end-result outcome measures, because an assumption must be made that hospitalization, for example, is appropriate or inappropriate in view of patient condition. This renders it challenging to adjust utilization outcomes for risk factors that comprehensively take into consideration the natural progression of patient condition, because the multiplicity of reasons for the occurrence of emergent care, nursing home admission, or hospital admission, can be extensive.

Measurement Precision and Types

The ambulation scale provided in Table 2 provides an illustration of a health status scale that can be used to compute an outcome measure. By collecting data with such a scale at an initial time point (start of care) and a followup point, it is possible to assess whether an individual improved or worsened in ambulation ability. All levels of the ambulation scale are specifically defined. Its values are not defined simply in terms of “independent,” “partially dependent,” or “dependent,” because such terms used alone to define a scale introduce considerable subjectivity. Outcome measure precision and reliability depend predominantly on the precision and reliability of data item(s) used to compute the outcome measure. This scale is an ordinal scale whose levels have been reliability tested in home health care settings.

Table 2. End-Result Outcome Measure Examples.

| Scale—Assume the Following Ordinal Scale for Ambulation: |

| Ambulation: Refers to the patient's ability to safely ambulate in a variety of settings. |

| 0 - Is able to independently (i.e., without human assistance) walk on even and uneven surfaces without the use of a device (e.g., walker, cane) and climb stairs with or without railings. |

| 1 - Is able to walk alone only when using a device (e.g., cane, walker) or requires human supervision/assistance to negotiate stairs/steps or uneven surfaces. |

| 2 - Is able to walk only with the supervision/assistance of another person at all times. |

| 3 - Chairfast, unable to ambulate even with assistance but is able to wheel self independently. |

| 4 - Chairfast, unable to ambulate even with assistance and is unable to wheel self. |

| 5 - Bedfast, unable to ambulate or be up in a chair. |

| Outcome Measure 1 (Dichotomy) |

| Improvement in Ambulation at 1 Month or Discharge: Defined only if the patient can improve (i.e., the patient has a value of 1 or greater at start of care [SOC] on the above scale). |

| 1 → Patient scale value is less at followup (1 month or discharge, whichever occurred first) than scale value at SOC. |

| 0 → Patient scale value not less at followup than at SOC. |

| Outcome Measure 2 (Dichotomy) |

| Discharged to Independent Living and Improved by 2 Months: Defined only if the patient can improve (i.e., the patient has a value of 1 or greater at SOC on the above scale). |

| 1 → Patient was discharged to independent living within 2 months after SOC and patient scale value is less at discharge than at SOC. |

| 0 → Patient was not discharged to independent living, or was discharged to independent living but with scale value not less at discharge than at SOC. |

| Outcome Measure 3 (Integer-Valued) |

| Degree of Change in Ambulation at 3 Months or Discharge: Defined for all patients. The numeric change in the above 6-point ordinal ambulation scale between admission and 3 months or discharge (whichever occurs first). |

SOURCE: Shaughnessy, P.W., Crisler, K.S., Schlenker, R.E., Arnold, A.G., Kramer, A.M., Powell, M.C., and Hittle, D.F., the University of Colorado, 1994.

Three outcome measures, two dichotomies, and an integer-valued measure are illustrated in Table 2. Although we recommend the use of a 60-day time period, examples are provided in the table for 30 and 90 days, as well, to illustrate the varying time periods for which measures can be specified. (The data collection time periods in this article are interchangeably referred to as 1, 2, and 3 months or 30, 60, and 90 days.)

The first measure corresponds to improvement in ambulation at 30 days or discharge. It is defined in accord with definition (4) given earlier. A variant of measuring improvement is illustrated by the second measure, which combines both improvement and discharge to independent living by 60 days or discharge. This measure takes on the value 1 only if the patient has improved and has been discharged to independent living by the time point under consideration. The third measure illustrated in Table 2 is an integer-valued or polychotomous measure whose values correspond to the numeric change or difference between values on the ambulation scale at start of care and 90 days or discharge. It has the advantages that it is multivalued, its magnitude approximates the degree of change, and its sign connotes whether a positive or negative change occurred. However, because it represents a difference using an ordinal (not an interval) scale, the magnitude of its values can be misleading. The difference between a 5 and a 3 on the ambulation scale is not necessarily the same in terms of patient condition as the difference between a 3 and 1. Hence, a value of 2 for this measure obtained by a patient changing from a 5 to 3 does not necessarily reflect the same extent of improvement as a value of 2 obtained by a patient changing from a 3 to a 1. The dichotomies have the redeeming and intuitively understandable feature of yielding percentages when mean values are taken. Therefore, the average for patients who improved in ambulation actually reflects the percentage of patients improved in ambulation. Dichotomies that yield percentages as mean values are appealing in QA applications.4 A number of researchers and providers have developed scales and measures that can be used for health status assessment and therefore outcome analysis when data are collected for such scales over time (Lohr, 1988). Doubtlessly, the precision and reliability of such scales will continue to be improved. In this regard, approaches to outcome measurement and outcome-based quality improvement should be sufficiently flexible to incorporate improved approaches to measuring health status and to adjust for the natural progression of disease and disability in assessing outcomes of care.

Risk Factors and Case Mix

Additional terms that are used somewhat differently in various settings are introduced and defined in this section for the sake of integrating several concepts. No pretense is made that the definitions provided here are appropriate for all health care applications, nor are they necessarily superior to other definitions of the same constructs; rather they serve the purposes of this discussion and are intended to clarify certain topics relevant to OBQI in home care.

(17) Covariate

As used here, the term “covariate” refers to a variable that should be taken into consideration when analyzing a given variable as a dependent variable (such as a quality, cost, or utilization measure). For example, a variable representing presence or absence of a qualified caregiver at home might be an important covariate to consider when examining measures of the quality of home health care. A covariate can refer to any type of variable that characterizes the patient's circumstances, including a characteristic of the patient environment or community, a characteristic of the provider, a patient status variable, demographic or socioeconomic characteristics of the patient, or even payer characteristics.

(18) Patient (health) status variable

A patient status variable denotes or reflects a quantification of patient health status. Thus, a dichotomous indicator of presence or absence of incontinence, a scale that can be used to quantify a patient's ability to feed himself or herself, an interval scale for systolic blood pressure, etc., are all patient status variables. At times variables that denote patient attributes other than health status, such as age, gender, education level, payer, etc., are referred to as patient status variables. We prefer to distinguish between these variables and patient health status variables by terming the former variables general patient characteristics.

(19) Case mix

Overall, patient status variables and general patient characteristic variables reflect the health service or health care needs of a patient. When aggregated across a group of patients, these variables can be termed case-mix variables and therefore refer to the case mix of the group.

(20) Risk factor

For our purposes, a risk factor for a particular (health-related) outcome is a patient status variable or a characteristic of the patient's environment or circumstances that can influence or mitigate the outcome. Generally speaking, risk factors can be regarded as covariates when one is analyzing any type of quality measure (i.e., not simply outcome measures).

Theoretically, then, the case mix of a group of patients refers to or translates directly into the group's service needs, independently of whether the services are actually provided. Patient status variables, including the presence, absence, or severity of problems (such as cardiac conditions, diabetes, orthopedic impairments, or pulmonary conditions), determine a patient's health care needs. These might be translated into service-specific case-mix measures such as the number or percentage of patients in need of cardiac medications, insulin, range of motion therapy, or lung auscultation, respectively. Noteworthy, however, is the fact that these measures are conceptually different from the number of patients on cardiac medications or insulin, receiving range of motion therapy, or receiving lung auscultation, because factors in the first set measure patient needs while those in the second set measure services received. The degree of concurrence between needs and services received is an indicator of the extent to which health care needs are satisfied, and therefore yields process measures of quality. Analogously, change in patient status or health care needs over time is an indicator of patient status outcomes over that time period. Hence, the same variables that are used to measure case mix at a single point in time can be used to measure outcomes at two (or more) different points.

Two Basic Ways to Risk Adjust Outcomes

The natural progression of patient condition is a function of patient circumstances and health status. Consequently, in analyzing outcomes to discern the effects of antecedent care separately from natural progression, it is necessary to adjust (as well as possible) for those circumstances and health status attributes that determine the natural progression of the condition under consideration. Therefore, assessing outcomes typically entails adjusting for risk factors or case-mix variables. The ways to do this are twofold. First, patients (receiving care from two different agencies, say) can be grouped or stratified into categories of patients with similar conditions (e.g., patients with open wounds or lesions) so that within-strata comparisons can be made for patients with similar risk factors. Second, statistical methods such as standardization (for distributional differences in risk factors for the populations being compared) or multivariate modeling (such as logistic regression or survival analysis with covariates) can be employed, where the covariates consist of the risk factors for which one wishes to adjust.

These two methods, stratification and statistical adjustment, can be used in combination by first stratifying the patient population into meaningful groups defined in terms of the most pivotal risk factors, and then using statistical adjustment within these groups to adjust for additional risk factors if necessary. Rarely, if ever, is it possible to totally compensate for all possible risk factors, because the number and types of risk factors that can influence patient outcomes are often sufficiently extensive so as to preclude data collection from a practical point of view (e.g., the multiple dimensions of patient health and familial history, motivational and environmental circumstances that can influence outcomes, etc.). As a result, the goal is typically to minimize variation in the outcome measure(s) due to risk factors and to use the dictates of sound clinical judgment and statistical common sense in interpreting risk-adjusted findings to draw inferences about the effects of care on the outcome(s).

A Grouping Scheme for Stratification

An illustration of a grouping or stratification scheme to adjust for risk factors in analyzing outcomes of home health care is the quality indicator group (QUIG) classification scheme. In the initial stages of our work to develop a system of outcome measures for home health care, an effort was made to specify patient conditions that result in different types of health care needs, and require potentially different outcome measures to assess the effectiveness of care.

In order to distinguish between QUIG-specific quality measures and measures that are useful for multiple QUIGs, the terms focused and global measures are used:

(21) Focused quality measure

A focused measure pertains to a specific patient group (type) or stratum (e.g., patients with diabetes mellitus, patients with peripheral vascular disease, or terminally ill patients). Thus, focused measures always correspond to specific patient groups or strata.

(22) Global quality measure

A global quality measure pertains to all patients. Hospitalization, properly quantified, is a global quality measure for all home health patients under the care of a given agency. Typically, a wider array (but not necessarily a larger number) of risk factors or case-mix variables for global measures signifies poor (or exemplary) care.

Focused measures have the advantage of requiring less risk adjustment (theoretically) because certain risk factors are naturally taken into consideration by restricting the measures to specific conditions. They have the disadvantage, however, of pertaining to fewer patients and therefore lowering sample sizes, which in turn requires larger discrepancies between (statistical) standards and observed means in order to conclude that quality might be problematic or exemplary for certain patient groups. Relative to focused measures, global measures tend to overcome this problem because they are defined for larger numbers of patients. However, because global measures typically require more thorough risk adjustment, they can be more burdensome and possibly less precise.

In developing the QUIG classification approach, our intent was to group patient conditions so that: (a) outcome measures would be as homogeneous as possible for purposes of assessing within-QUIG quality, while outcome measures would be more heterogeneous across QUIGs and (b) patient conditions would be grouped according to the most clinically significant risk factors that might influence measures used to assess outcomes for all patients combined. Consequently, an effort was made to define groups using conditions that would be worthwhile for purposes of applying different (within-group or focused) quality measures and, at the same time, to specify conditions that also would be worthwhile as risk factors in adjusting (across-group or global) quality measures. Because of these operational goals, we made a continual effort to constrain the number of QUIGs, so that the taxonomy would be useful but not unwieldy for applications.

The QUIGs that emerged from the study are presented schematically in Table 3. These QUIGs are the result of several successive iterations involving development by staff, clinical panel review, monitoring other developmental efforts, pilot data collection to classify patients, and empirical revisions. QUIGs are important in the context of the overall approach taken in the research because they represent a way to adjust quality measures for case mix using clinically meaningful risk factors that have been empirically validated. The QUIGs can be used to stratify patients into (non-exclusive or overlapping) groups for purposes of examining within-condition or focused quality measures, or they can be used as case-mix variables or risk factors to be employed in adjusting global outcomes for all patients or larger groups of patients. Further specifics on conceptual and developmental approaches to the QUIG taxonomy are documented elsewhere (Shaughnessy et al., 1993; Shaughnessy et al., 1991a; Kramer et al., 1990).

Table 3. Quality Indicator Groups (QUIGs).

| QUIG Number | Description of QUIGs and Examples |

|---|---|

| Acute Conditions | |

| 1 | Acute Orthopedic Conditions (e.g., fracture, amputation, joint replacement, degenerative joint disease) |

| 2 | Acute Neurologic Conditions (e.g., cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis, head injury) |

| 3 | Open Wounds or Lesions (e.g., pressure ulcers, surgical wounds, stasis ulcers) |

| 4 | Terminal Conditions (e.g., palliative care for malignant neoplasms, advanced cardiopulmonary disease, end-stage acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]) |

| 5 | Acute Cardiac/Peripheral Vascular Conditions (e.g., congestive heart failure, angina, coronary artery disease, hypertension, myocardial infarction) |

| 6 | Acute Pulmonary Conditions (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, pulmonary edema) |

| 7 | Diabetes Mellitus* |

| 8 | Acute Gastrointestinal Disorders (e.g., gastric ulcer, diverticulitis, constipation with changing treatment approaches, ostomies, liver disease) |

| 9 | Contagious/Communicable Conditions (e.g., hepatitis, tuberculosis, AIDS, Salmonella) |

| 10 | Acute Urinary Incontinence/Catheter* |

| 11 | Acute Mental/Emotional Conditions (e.g., anxiety disorder, depression, bipolar disorder) |

| 12 | Oxygen Therapy* |

| 13 | Intravenous/Infusion Therapy* |

| 14 | Enteral/Parenteral Nutrition Therapy (e.g., total parenteral nutrition, gastrostomy/jejunostomy feeding) |

| 15 | Ventilator Therapy* |

| 16 | Other Acute Conditions* |

| Chronic Conditions | |

| 17 | Dependence in Living Skills (e.g., meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry) |

| 18 | Dependence in Personal Care (e.g., bathing, dressing, grooming) |

| 19 | Impaired Ambulation/Mobility (e.g., ambulation, transferring, toileting) |

| 20 | Eating Disability* |

| 21 | Urinary Incontinence/Catheter Use* |

| 22 | Dependence in Medication Administration* |

| 23 | Chronic Pain* |

| 24 | Cognitive/Mental/Behavioral Problems (e.g., Alzheimer's, confusion, agitation, chronic brain syndrome) |

| 25 | Chronic QUIG Membership With Caregiver* |

NOTE: For asterisked (*) items, an example is not given because the QUIG name is sufficient to define the condition(s) included.

SOURCE: Shaughnessy, P.W., Crisler, K.S., Schlenker, R.E., Arnold, A.G., Kramer, A.M., Powell, M.C., and Hittle, D.F., the University of Colorado, 1994.

As shown in Table 3, the QUIGs are divided into two broad types of conditions or care needs: acute and chronic. The nomenclature associated with these categories gave rise to a semantic dilemma. Some individuals initially viewed the terms “acute” and “chronic” as synonymous with Medicare and non-Medicare, respectively, at least from a reimbursement perspective. In fact, these terms are not used in this manner. A Medicare patient (or non-Medicare patient) usually belongs to several QUIGs, because QUIGs are condition-specific and therefore not mutually exclusive. We have found that the typical adult home health patient belongs to three or four QUIGs, often belonging to acute and chronic QUIGs at the same time.

Our earliest QUIG taxonomy entailed specifying broad areas of patient needs, not conditions. From this taxonomy, we translated broad care needs into more specific conditions, yielding our first formal QUIG classification. The use of acute and chronic conditions persisted in our QUIG taxonomies thereafter. As it presently exists, the QUIG taxonomy is useful for adult patients who receive traditional home health care. In future research, we will attempt to specify patient conditions or QUIGs that correspond to preventive services, possibly to subdivide some of the acute QUIGs more precisely for high-tech or specialized care outcome assessment, to consider other patient types more directly such as pediatric populations, to refine the chronic QUIGs through further analysis and applications, and, in general, to continue to refine the QUIGs on the basis of empirical results from OBQI applications.

To illustrate the types of outcome measures used, consider the QUIG corresponding to acute cardiac/peripheral vascular conditions. This condition is often found in Medicare home health patients. Three of the outcome measures specified as important for this group are: (1) improvement in management of oral medications; (2) improvement in dyspnea; and (3) emergent care for cardiac problems. If, for patients in this particular QUIG, an agency performs significantly above or below average (or significantly above or below some statistical norm) for one or more of these outcomes, additional steps to reinforce or remedy the processes of care would be appropriate. If no problems were found, then it would not be necessary to remedy or change the manner in which care is provided for patients in this QUIG. Table 4 contains examples of several global and focused measures. The first category of outcome measures pertains to multiple QUIGs (i.e., all patients) and therefore consists of global measures. The next three categories consist of QUIG-specific measures and therefore illustrate focused outcome measures. Within each of the four categories, end-result and utilization outcome measures as well as intermediate-result outcome measures are illustrated. Within the category of end-result outcomes, both functional and other health status outcomes are illustrated for the focused measure sets corresponding to acute orthopedic conditions, acute cardiac/peripheral vascular conditions, and chronic cognitive/mental/behavioral problems. Precise definitions of the values taken on by each measure in Table 4 are not given, although it should be clear from context how the various measures would be defined in view of the ambulation scale and measures given in Table 2. The measures in Table 4 are but illustrative because our current research may result in alterations to the nature and substance of such measures in order to apply them in “steady-state” OBQI.

Table 4. Illustrative Quality Indicator Group (QUIG) Global and Focused Outcome Measures.

| Outcome Measures for All QUIGs (Global Measures) | Outcome Measures for QUIG 1: Acute Orthopedic Conditions (Focused Measures) |

| End-Result Outcomes and Utilization Outcomes: | End-Result Outcomes and Utilization Outcomes: |

| Functional Outcome Measures | Functional Outcome Measures |

| Improvement in Ambulation | Improvement in Ambulation |

| Stabilization in Ambulation | Stabilization in Transferring |

| Improvement in Management of Oral Medications | Health Status Outcome Measures |

| Improvement in Patient/Caregiver Ability to Manage Equipment | Improvement in Pain |

| Stabilization in Pressure Sores | |

| Utilization Outcome Measures | Utilization Outcome Measures |

| Acute Hospitalization | Emergent/Urgent Care (i.e., hospitalization, emergency room/clinic/office visit) Resulting From Fall |

| Intermediate-Result Outcomes: | Acute-Care Hospitalization |

| Family/Caregiver Strain Outcome Measures | |

| Improvement in Perceived Ability to Manage Demands | Intermediate-Result Outcomes: |

| Stabilization in Perceived Ability to Manage Demands | Family/Caregiver Strain Outcome Measures |

| Improvement in Perceived Ability to Manage Demands | |

| Outcome Measures for QUIG 5: Acute Cardiac/Peripheral Vascular Conditions (Focused Measures) | Stabilization in Perceived Ability to Manage Demands |

| Knowledge/Skill/Compliance Outcome Measures | |

| End-Result Outcomes and Utilization Outcomes: | Improvement in Ambulation/Walking Exercise Program |

| Functional Outcome Measures | |

| Improvement in Management of Oral Medications | Outcome Measures for QUIG 24: Chronic Cognitive/Mental/Behavioral Problems (Focused Measures) |

| Health Status Outcome Measures | |

| Improvement in Dyspnea | End-Result Outcomes and Utilization Outcomes: |

| Stabilization in Weight | Functional Outcome Measures |

| Improvement in Activity Level | Stabilization in Communication Ability |

| Utilization Outcome Measures | Stabilization in Socialization Activities |

| Non-Emergent MD/Outpatient Care for Cardiac Problems/Medication Side Effects | Stabilization in Use of Telephone |

| Health Status Outcome Measures | |

| Emergent Care in Hospital, Emergency Room, or Medical Doctor Office for Cardiac Problem | Stabilization in Depression |

| Stabilization in Frequency of Confusion | |

| Stabilization in Frequency of Behavioral Problems | |

| Intermediate-Result Outcomes: | Unmet Need Outcome Measures |

| Knowledge/Skill/Compliance Outcome Measures | Improvement in Unmet Need for Supervision |

| Improvement in Knowledge of Contraindications to Cardiac Glycoside Medication | Intermediate-Result Outcomes: |

| Stabilization in Compliance With Cardiac Glycoside Medications | Knowledge/Skill/Compliance Outcome Measures |

| Improvement in Knowledge of Safety | |

| Stabilization in Compliance With Diuretics | Improvement in Knowledge of Medications |

| Improvement in Knowledge of Signs/Symptoms to Report | Compliance With Medications |

SOURCE: Shaughnessy, P.W., Crisler, K.S., Schlenker, R.E.; Arnold, A.G., Kramer, A.M., Powell, M.C., and Hittle, D.F., the University of Colorado, 1994.

Statistical Adjustment for Risk and Time-Period Comparisons

The various methods of statistical adjustment, including standardization and multivariate modeling, are well-known (Thomas, Holloway, and Guire, 1993). Consequently, illustrations of these procedures are not provided here. As has been the case for risk-adjusted hospital mortality and for diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), it is natural that home health care applications of OBQI using risk adjustment will evolve over the course of time (Branch and Goldberg, 1993; Smith et al., 1992; Lohr, 1988).

Another type of comparison involves assessing outcomes for patients admitted to a particular (home) health care provider during one time period and comparing the findings with outcomes for patients admitted to the same provider during another time period. For example, to implement continuous quality monitoring using 12-month time intervals, a home health agency might collect health status information on its patients, compute outcomes on the basis of change in health status measures (or compute utilization outcome measures), and compare outcomes with the preceding time period, possibly within QUIGs. Because agency case mix is reasonably stable over time (with some exceptions), especially within QUIGs, this would generally preclude the need to adjust for risk factors beyond a clinically acceptable stratification approach (such as QUIGs) in terms of patient condition. This across-time period approach to stratifying patients within QUIGs is a useful application of stratifying according to one dimension of patient care (i.e., time) combined with another dimension of patient care (i.e., patient condition) and, by so doing, minimizing or eliminating the need for statistical risk-factor adjustment in operational CQI programs at the agency level.

Outcome-Based Quality Improvement

The following four terms are defined in order to facilitate the discussion of OBQI, as presented in this article:

(23) Quality assessment

The term “quality assessment” refers to the process of assessing and evaluating the quality of care, independently of whether the ultimate outcome of the assessment is to improve or change the quality of care. In its broadest sense, quality assessment can be conducted informally or formally, where informal approaches entail subjective impressions, certain types of cases or record review, or patient/provider opinions or reactions. More formal approaches to quality assessment can entail systematic or structured approaches to record review, patient observation, care provision, data collection, and analysis of quality measures.

(24) Quality assurance and quality improvement

The terms “quality assurance” and “quality improvement,” as used here, refer to the process of maintaining or improving the quality of care, at times in accord with preset standards or goals. A QA or quality improvement program entails a sequence of activities targeted at maintaining and improving quality of care, often in specific areas of patient care. At the basis of any QA/quality improvement program or system is a means to assess quality. Quality measures are frequently used in quality assessment and QA, often in conjunction with case review by clinicians or other experts.

(25) First-stage (quality improvement) screen

As used here, the term “first-stage screen” refers to an approach to assessing whether potential quality of care problems exist in specific areas. The first-stage screen can be envisioned as having its basis in a set of (predominantly or exclusively outcome) measures that are used to ascertain the potential existence of quality-of-care problems. The screen does not necessarily indicate the reasons for the quality-of-care problems or prove definitively that such problems exist.

(26) Second-stage (quality improvement) screen

This term refers to a process of assessing the quality of home health care after conducting the first-stage screen just described. The second-stage screen might include a set of measures and related activities to more definitively indicate whether certain quality problems exist and, if so, point to their potential causes. The second-stage screen is more likely to be regarded as an operational quality improvement tool after potential quality problems (or exemplary care) have been identified using the first-stage screen. (The first-stage screen can be considered an operational QA tool, however, in that it can be used to either identify potential problems or infer that quality of care is adequate if potential problems are not found.) At the agency level, the second-stage screen could entail a variety of activities in addition to, or in lieu of, formally analyzing process quality measures, because individual case review, informal or systematic discussions with providers of care, etc., might be appropriate as agency-determined approaches to the second-stage screen.

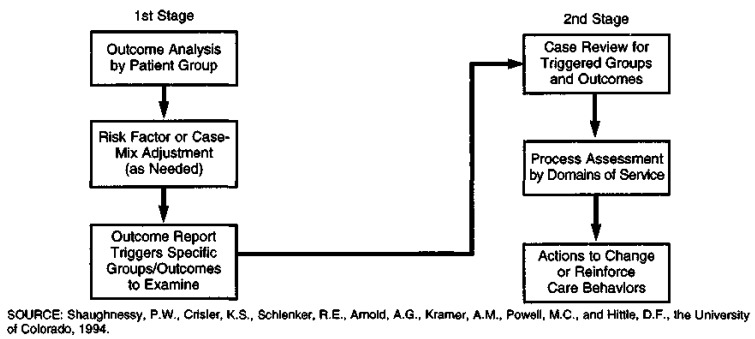

Figure 4 provides an overview of the two-stage approach to QA introduced in definitions (25) and (26) above. In essence, the first-stage screen is an outcome screen that entails analyzing outcomes by group (e.g., by QUIGs), and possibly further risk adjusting within QUIGs, or by using QUIGs as covariates instead of grouping and stratifying variables. If an agency's outcomes are outside of a statistically determined acceptable range, then a second-stage screen or (predominantly) process quality screen would be triggered. This screen could entail record review for those patient conditions triggered by unacceptable (or exemplary) outcomes. A less formal (and perhaps less effective) variant on the second-stage screen might entail structured or unstructured discussions with providers of care regarding reasons for the unacceptable or exemplary outcomes. In either event, the record review and/or discussions with providers of care would consist of an analysis of services provided to patients with outcomes triggered as a result of the first-stage screen. Depending on how it is structured, the second-stage screen can permit an assessment of the reasons for inferior (or superior) outcomes or an analysis of care provided to individual patients whose outcomes warrant further analysis of services provided.

Figure 4. The Quality Assessment Target: A Two-Stage Quality Improvement Screen.

Outcome measures, as well as groups or patient conditions that might be used in a first-stage screen, have been introduced in Tables 3 and 4. Service criteria that might be examined in a second-stage screen, on the assumption that QUIGs were used for group-specific outcome analyses in the first-stage screen, have undergone initial development as part of our home health research program. The QUIG-specific services are called objective review criteria (ORCs). They were initially specified by our clinical staff and then subjected to external clinical review. Data on such service criteria or ORCs can be abstracted from clinical records as part of a second-stage screen to ascertain whether the agency's service profile for the triggered outcomes reflects certain problems or exemplary types of care. Further discussion on ORCs is available elsewhere (Shaughnessy et al., forthcoming). An illustration of a (partial) set of ORCs for dependence in ambulation is given in Table 5. This table represents a form which can be used to abstract service data from clinical records.

Table 5. Objective Review Criteria for Abstracting From Clinical Records to Assess Care When Ambulation Outcome Results Are Atypical.

| Characteristic of Patient or Environment | Assessment Services | Assessment Documented | Characteristic Present | Care Planning/Intervention Services | In Plan of Care | Intervention Documented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No/NA | Yes/No/NA | |||

| Impaired gross motor function interfering with ambulation |

Record if the following assessments were done and if they indicate the presence of impaired gross motor function interfering with ambulation:

|

|

||||

| Pain interfering with activity |

Record if the following assessment was done and if it indicates the presence of pain interfering with activity:

|

|

||||

| Inadequate environment for ambulation |

Record if the following assessments were done and if they indicate the presence of an inadequate environment for ambulation:

|

|

NOTES: This table is excerpted from a form used to abstract data from clinical records. Shaded area denotes “not applicable” responses. Assessment, care planning, and information criteria correspond to a sample of the several characteristics used for dependence in ambulation. Other characteristics include altered cognitive function, activity intolerance, need for human assistance with ambulation, and need for mechanical assistance with ambulation. These ORCs relate specifically to patients with: acute orthopedic conditions (e.g., fracture, amputation, joint replacement, DJD); acute neurologic conditions (e.g., CVA, multiple sclerosis, head injury, etc.); chronic impaired ambulation/mobility (e.g., ambulation, transferring, toileting); or chronic pain.

Outcome Reporting

To implement a second-stage screen, an agency must review results from the first-stage (outcome) screen. Figure 5 provides an illustration of an outcome report for orthopedic patients that might typify an outcome profile for an individual agency. (Data and significance levels are hypothetical.) All outcome measures used in Figure 5 correspond to a baseline time point defined as start of care and a followup time point corresponding to discharge or 60 days after start of care, whichever occurred first. As they appear in Figure 5, the outcome findings are adjusted for risk factors. The outcomes include some of those specified in Table 4 for orthopedic conditions in addition to others included to demonstrate the utility of collecting a basic set of information on all patients, thereby allowing analyses of additional outcomes. The three bars for each outcome respectively depict the percentage of orthopedic patients who attained that outcome during the current (most recent) reporting period for the agency, during the (immediately) prior period for the agency, and in a national random sample of orthopedic patients from home health agencies across the country. The first numeric column (to the left of the bar chart) contains the number of cases (patients) that contributed to the outcome for each of the three groups used in the comparison. For example, 86 orthopedic patients contributed to the computation of the measure corresponding to improvement in ambulation during the current reporting period, compared with 76 during the preceding reporting period, and 1,382 patients in the national random sample (recall that the improvement and stabilization measures have exclusions as described in definitions [4] and [6]).

Figure 5. Orthopedic Patients' Outcome Profile.

The second numeric column contains statistical significance levels corresponding to the two comparisons of interest for each outcome: current period versus prior period, and current period versus national norm. Thus, the significance level associated with comparing the improvement-in-ambulation mean for the current period with the mean for the prior period (43.4 percent versus 32.6 percent) is p = .08. The analogous significance level associated with comparing the current period with the national norm is p = .06.

Using p < .10 as statistically significant, the results in Figure 5 would indicate that, for orthopedic patients, the agency has improved in the current reporting period relative to the preceding reporting period for the outcomes of improvement in ambulation and stabilization in dressing the lower body. Agency performance worsened, however, in terms of improvement in dressing the lower body and improvement in management of oral medications. Relative to the national sample, agency performance was superior in terms of improvement in ambulation, improvement in dressing the lower body, and acute-care hospitalization within 60 days of admission to home care, whereas agency performance was inferior in terms of stabilization in transferring. With respect to improvement in dressing the lower body, although the agency's outcome decreased significantly since the prior reporting period, its performance is still superior to the national norm.

Some or all of these significant differences might warrant further investigation. It would not be our recommendation, initially, for an individual agency or for Medicare to investigate all possible differences that are statistically significant As a starting point, it would be appropriate to ascertain reasons for the most extreme (statistically significant) differences that are meaningful both in terms of the magnitude of the differences and their clinical relevance. For example, because agency performance was inferior to the national random sample only for the outcome of stabilization in transferring, and far superior for acute hospitalizations, these two outcomes might be the focus of a second-stage screen. The QUIGs or conditions that are used for stratification should be viewed as a grouping scheme to assist in outcome assessment. It is possible to use other grouping schemes, to combine QUIGs, to subdivide them to examine outcomes for particular types of patients, and to weight selected QUIGs or even outcomes more than others. Such variations in the OBQI methods introduced here would be implemented at the discretion of individual users of the system. The type of outcome report illustrated in Figure 5 is currently being employed in a three-agency OBQI pilot project in Colorado that we have undertaken with Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funding.

Outcome-Based Quality Improvement: Starting and Evolving