The Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) is a powerful tool for analyzing enrollees' access to medical care (Adler, 1994). Based on a stratified random sample, we can derive information about the health care use, expenditure, and financing of Medicare's 36 million enrollees. We can also learn about those enrollees' health status, living arrangements, and access to and satisfaction with care.

In the charts that follow, we have presented some findings on how long it takes enrollees to get an appointment with a provider, how they get to the provider's office, and how long their wait is when they get there.

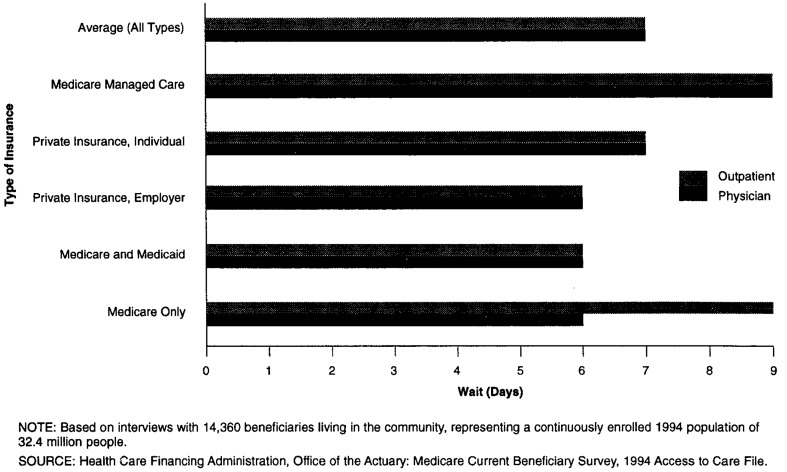

Wait (in Days) Before Provider Appointment for Medicare Enrollees, by Type of Insurance.

Getting an Appointment

On average, beneficiaries can get an appointment with a doctor or with the outpatient department in about a week. There are minor differences in the wait times for people with different types of insurance.

Generally, it takes a beneficiary in a Medicare managed care plan longer to schedule an appointment with a physician or with the outpatient department. However, waits at the physician's office or at the outpatient department are slightly shorter for managed care enrollees.

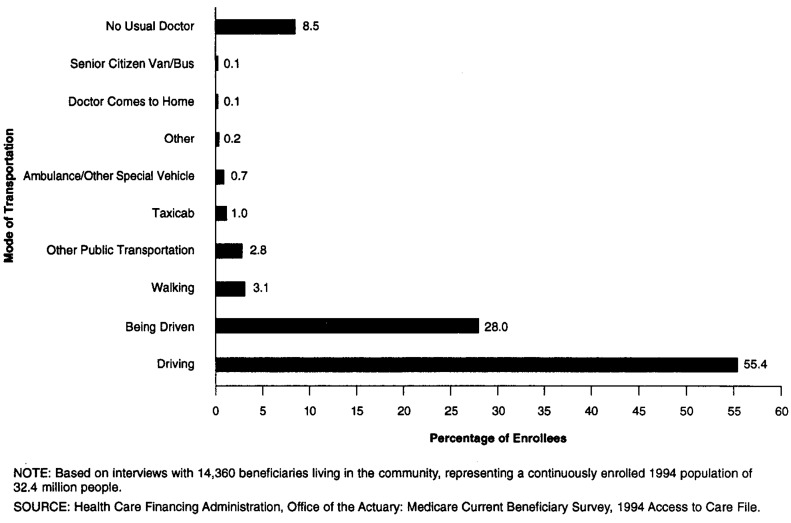

Percentage of Enrollees Using Particular Modes of Transportation to Get to Provider Site.

Getting to the Doctor

Among beneficiaries with a usual source of care, most drive or are driven to their doctor (83.4 percent). About one million beneficiaries walk to their usual source of care. More than one million beneficiaries use some sort of public transportation to get to the doctor, and they may have to pay for that transportation.

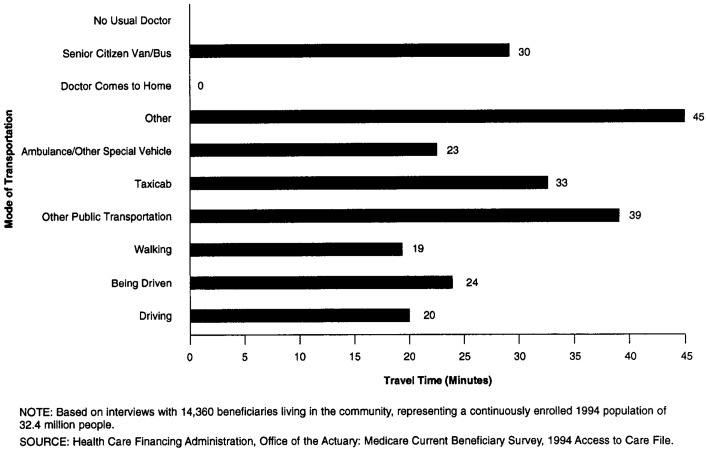

Travel Times to Provider Site, by Mode of Transportation.

Getting to the Doctor

Travel times average less than an hour for all modes of transportation, but about 2 percent of all beneficiaries travel more than an hour (one way) to their usual source of care.

Only 6 percent of beneficiaries who have no usual source of care give “the doctor is too far away, or not convenient” as a reason.

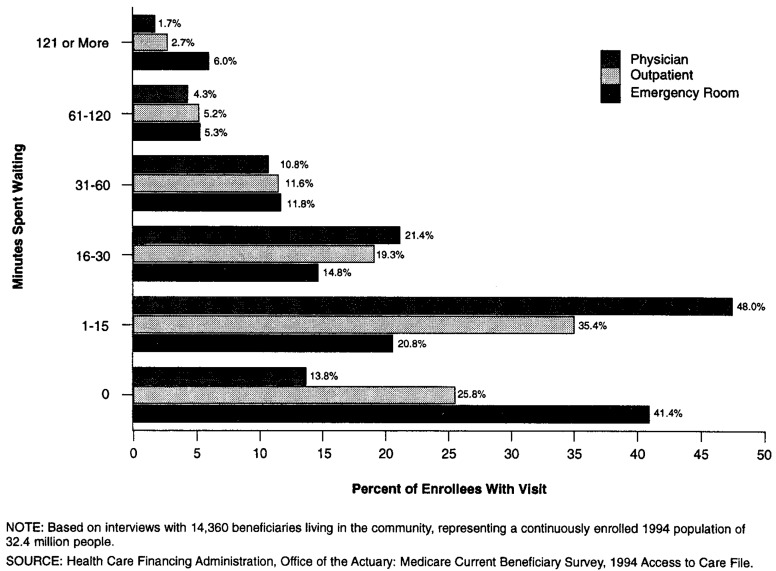

Minutes Spent Waiting for Provider, by Site of Provider.

Waiting for the Doctor

Except for emergency room visits by beneficiaries with no usual source of care, wait times for all types of visits average about 30 minutes. About 60 percent of beneficiaries report wait times of 15 minutes or less during outpatient and doctor visits. Beneficiaries report “Did not have to wait” for 41 percent of all emergency room visits, 26 percent of outpatient visits, and 14 percent of all doctor visits.

On average, beneficiaries spend about 40 percent of a doctor visit, and 20 percent of an outpatient visit, waiting to be seen. Survey responses show no significant differences between people who have a usual source of care and those who do not.

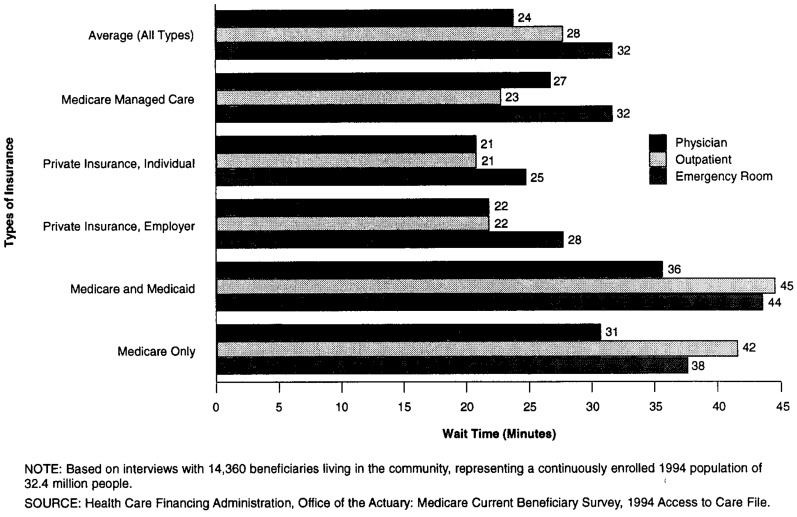

Wait Times at the Provider's Site, by Type of Insurance.

Insurance and Wait Times

In all types of visits, beneficiaries who have supplemental private insurance (either purchased directly—such as a “Medigap” policy, or obtained through a current or previous employer) have shorter-than-average waits than beneficiaries who have only Medicare.

Beneficiaries who are entitled to both Medicare and Medicaid experience longer waits, in all settings, than any other group of insured beneficiaries.

Beneficiaries in Medicare managed care plans wait for shorter periods of time than do Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who have no supplemental insurance.

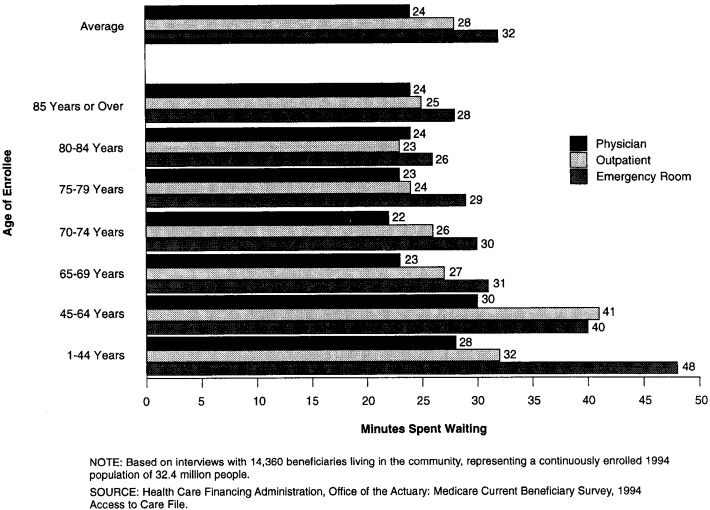

Minutes Spent Waiting for Provider, by Age of Enrollee and Site of Provider.

Wait Times and Age

In all settings, aged beneficiaries (those 65 years of age or over) are seen more quickly and are able to make appointments more quickly than disabled beneficiaries (those under 65 years of age). Disabled beneficiaries report especially long waits in the emergency room, 25 to 50 percent longer than the average wait for all Medicare beneficiaries.

Other factors, such as the beneficiary's gender, urban-rural status, or general health appear to be unrelated to wait times, but beneficiaries in poor or fair health report that they are able to make appointments more quickly.

Footnotes

The authors are with the office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of HCFA.

Reprint Requests: Mary Hogan, Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary, 7500 Security Boulevard, N-3-04-05, Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850.

Reference

- Adler G. A Profile of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Health Care Financing Review. 1994 Summer;15(4):153–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]