Abstract

This article assesses the extent to which managed competition could be successful in rural areas. Using 1990 Medicare hospital patient origin data, over 8 million rural residents were found to live in areas potentially without provider choice. Almost all of these areas were served by providers who compete for other segments of their market. Restricting use of out-of-State providers would severely limit opportunities for choice. These findings suggest that most residents of rural States would receive cost benefits from a managed competition system if purchasing alliances are carefully defined, but consideration should be given to boundary issues when forming alliances.

Introduction

Many of the health care reform bills that were considered during 1993 and 1994 relied on managed competition as a mechanism to insure quality while holding down costs. Although the term “managed competition” has come to generically embody many aspects of health care reform, it specifically implies the creation of a constrained competitive market among insurers/providers who contract with some sort of “collective agent” (Enthoven and Kronick, 1989). The collective agent would represent a purchasing cooperative comprised of a group of individuals, most likely defined geographically, and large enough to have significant bargaining power with providers. An underlying assumption of this theory is that consumers are provided with a choice of plans and providers, and that by exercising this choice, coupled with the market power of the purchasing cooperatives, plans and providers will be forced to compete with each other on both price and quality.

There is debate among researchers and policymakers over the applicability of managed competition to many rural areas. Some have voiced concerns that in rural areas access to health care resources may be too limited to afford any meaningful competition. In examining this issue, Kronick et al. (1993) determined that 29 percent of the population lived in areas, mostly non-metropolitan, which were too sparsely populated to support three competitive plans. The authors concluded that these people would not be able to share in the benefits of a health reform plan based on managed competition. However, one must consider the role that carefully defined purchasing cooperatives might play in assuring a cost and quality benefit from managed competition to rural residents, even if these consumers have no provider choice.

An alternative view of the impact of managed competition on rural areas focuses on the potential for this model to foster the creation of new health networks and to increase primary-care providers in rural areas (Christianson and Moscovice, 1993). Although the managed competition model could benefit rural areas in these ways, significant regulatory intervention on the part of either the collective purchasing agents or State or Federal governments would be necessary to ensure access to affordable care in areas which are too sparsely populated to support provider or plan competition (Fuchs, 1994).

This article assesses the applicability of managed competition to rural areas, considering not only the concepts of provider competition and consumer choice, but also the possible impact of collective purchasing. For example, estimates of the population which would not benefit from managed competition which are suggested by Kronick et al. (1993) rest on several key assumptions; the most prominent is that the lack of consumer choice of providers alone automatically results in no benefit from managed competition for that population. Although consumers in some sparsely populated areas may not have a choice of either provider or plans, lack of choice does not necessarily rule out potential benefit from competition if collective purchasing occurs; if price discrimination between consumers served by the same provider is not allowed; or if consumers with no market power are in purchasing cooperatives with those who do have market power, there may still be cost and quality benefits from a managed-competition system. On the other hand, the existence of collective purchasing agents, which will most likely be defined at the State level, could also negatively affect both consumer choice and provider competition if access to providers is restricted by certain boundaries.

To assess the potential for the managed-competition model to succeed in rural areas, critical questions need to be addressed. First, to what extent do rural residents currently have a choice of providers? Second, for those individuals with limited provider options, do their local providers compete for other segments of their market, segments with whom individuals with limited provider options could join in a purchasing cooperative? And finally, if State-level health care reform includes some type of collective purchasing, what would be the impact on consumer choice and access if restrictions or financial penalties are placed on crossing State boundaries to receive health care?

Due both to their complex nature and to data availability limitations, these questions are difficult to address. This study uses 1990 Medicare inpatient discharge data in a first step toward understanding the possible impact of managed competition on rural areas, with special consideration of the importance of carefully defined purchasing cooperatives. The focus is on inpatient hospital services because other utilization data for the Nation are not available.

As it is neither possible nor desirable for all rural hospitals to provide highly technical specialty care (such as transplants), the analysis attempts to exclude data which represent extraordinary use. Inpatient hospital services for rural Medicare recipients are analyzed across two dimensions: (1) the degree of provider choice available, as evidenced by consumer utilization patterns that are the result of patient choice and the realities of local physician referral and admitting patterns, and (2) for areas that use only one provider, the extent to which that provider is competitive for other segments of their patient population. Additionally, the reduction in consumer choice which could occur if collective purchasing agents restrict travel across State borders will be examined.

Data Source and Sample Construction

Data for this study came from the 1990 HCFA Hospital Market Service Area (HMSA) file, PPSVII and PPSVIII Capital Data Sets (Medicare Cost Reports), the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals Data Base, and 1990 U.S. Census files. The HMSA file provided total number of discharges from each unique patient origin ZIP Code/hospital combination. Hospital type was determined from the PPSVII and PPSVIII files, and hospital ZIP Codes were obtained from the AHA file. Latitude and longitude of ZIP Code centroids, obtained from Atlas Pro software, were used to compute the approximate distance traveled to receive care. Populations were assigned to each ZIP Code area using data from the 1990 Census.

ZIP Code areas were categorized as non-metropolitan based on the 1990 county designation from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget metropolitan/non-metropolitan designation system; the term “rural” is used to refer to non-metropolitan, although that is not strictly consistent with accepted definitions of rural. Although a designation based on the ZIP Code alone would have been preferable, the necessary data were not available. The result of this categorization may be an understatement of the rural population, as rural ZIP Code areas which are contained within a county which is designated as metropolitan are excluded from the analysis.1

The study sample is comprised of all unique patient origin ZIP Code/short-term general hospital combinations for 19,833 non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas in the 48 contiguous United States. Non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas which had no Medicare discharges were not represented in the study sample. Three States—Connecticut, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—have no non-metropolitan counties, and so do not have ZIP Code areas included in the study sample. Observations for individuals residing in either Alaska or Hawaii were eliminated from the analysis for several reasons. The geographic isolation of these States made any analysis of interstate care seeking irrelevant. Additionally, due to Hawaii's unique health care system and Alaska's sparse population, it was felt that both States would be extreme outliers.

A multi-stage criterion, using both distance and percent of total ZIP Code area discharges, was used to eliminate hospital stays for extraordinary care, such as transplants, which most often is unavailable in many smaller hospitals; this care is also often received at some distance from where rural people live. To do this, all observations where distance between patient and hospital ZIP Code centroid was greater than 250 miles were first eliminated. Next, observations on hospital discharges within patient ZIP Code areas were rank-ordered according to the percent of total ZIP Code area discharges they represented. Beginning with the largest percentage, all observations necessary to account for 75 percent of the ZIP Code area's discharges were included in the sample. In this manner, actual patient preferences for care were reflected, even if the distance traveled to receive care was far. (For example, if 30 percent of the discharges were to a hospital 80 miles away, those cases would be included in the sample as they obviously represent current patterns of care.) The choice of 75 percent as a cutoff was reached after focused consideration of the number and location of ZIP Code/hospital pairs which would or would not be included in the sample under alternative cutoffs. Still, the choice is somewhat arbitrary; there is no precedent in the literature for establishing cutoff points for market assignment from the consumer's point of view, although in studies which focus on hospital-based market share, cutoffs are generally at 60 or 75 percent (Goody, 1993).

Finally, criteria needed to be applied to the observations which accounted for the remaining 25 percent of the ZIP Code area's discharges, in an attempt to delete extraordinary care discharges but still include in the sample observations which represented reasonable alternatives for routine hospital care. Although individual discharge data might allow for the classification of discharges into categories by severity, the acquisition and preparation of those data would require substantial effort beyond the means of this project and its funding. It was assumed that if observations were for care received at a distant hospital, or they only accounted for a small percentage of a given ZIP Code area's total discharges, then they were for extraordinary care. Therefore, double criteria of meeting both distance and percentage of discharge standards were applied. If an observation was for discharges at a hospital less than 50 miles away, and if more than 10 percent of the discharges from the ZIP Code were represented, then the observation was kept in the sample. The distance cutoff of 50 miles is generous, and allows for geographic differences in perceptions of what constitutes a “reasonable” distance to travel for care.2

Results

There were 2,259 non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas where all Medicare admissions that met the criteria for inclusion in the study sample were to a single hospital. (For the remainder of this article, these areas will be referred to as ZIP Code areas which use one provider, or ZCOPs.) These represented 11.4 percent of all non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas which had Medicare acute-care general hospital discharges in 1990. Approximately 8,077,988 individuals lived in these areas.3 For 77,847 of these individuals (under 1 percent), residing in 96 ZCOPs, the only source of inpatient care was an out-of-state institution. ZCOPs were found in all States with non-metropolitan counties in the contiguous United States. North Carolina had the highest total population residing in ZCOPs, while in Maryland, ZCOPs accounted for the largest percentage of all non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas in the State. A detailed listing by State is presented in Table 2. Explicit comparisons across States are difficult, as States vary in the proportion of ZIP Codes that are rural, population density in rural areas, and the land area encompassed by a ZIP Code.

Table 2. ZIP Code Areas in Which Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only One Hospital (ZCOPs), by State1.

| State | Total ZIPs in State2 | Number of ZCOPs | ZCOP (Percent) | Total Population of ZCOPs | Average Total Population/ZCOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 19,833 | 2,259 | 11.4 | 8,077,988 | 3,576 |

| Alabama | 357 | 15 | 4.2 | 78,628 | 5,242 |

| Arizona | 203 | 20 | 9.9 | 82,832 | 4,142 |

| Arkansas | 539 | 47 | 8.7 | 147,738 | 3,143 |

| California | 359 | 30 | 8.4 | 76,141 | 2,538 |

| Colorado | 314 | 63 | 20.1 | 89,232 | 1,416 |

| Delaware | 40 | 7 | 17.5 | 77,166 | 11,024 |

| Florida | 232 | 22 | 9.5 | 157,347 | 7,152 |

| Georgia | 496 | 41 | 8.3 | 316,080 | 7,709 |

| Idaho | 276 | 29 | 10.5 | 138,445 | 4,774 |

| Illinois | 810 | 59 | 7.3 | 276,958 | 4,694 |

| Indiana | 498 | 66 | 13.3 | 309,221 | 4,685 |

| Iowa | 813 | 44 | 5.4 | 150,274 | 3,415 |

| Kansas | 597 | 51 | 8.5 | 180,385 | 3,537 |

| Kentucky | 892 | 132 | 14.8 | 299,644 | 2,270 |

| Louisiana | 354 | 14 | 4.0 | 40,109 | 2,865 |

| Maine | 322 | 46 | 14.3 | 78,501 | 1,707 |

| Maryland | 132 | 59 | 44.7 | 164,169 | 2,783 |

| Massachusetts | 96 | 21 | 21.9 | 71,528 | 3,406 |

| Michigan | 558 | 46 | 8.2 | 201,582 | 4,382 |

| Minnesota | 653 | 56 | 8.6 | 149,028 | 2,661 |

| Mississippi | 424 | 35 | 8.3 | 193,319 | 5,523 |

| Missouri | 778 | 43 | 5.5 | 73,928 | 1,719 |

| Montana | 345 | 70 | 20.3 | 199,732 | 2,853 |

| Nebraska | 507 | 52 | 10.3 | 207,995 | 4,000 |

| Nevada | 75 | 16 | 21.3 | 2,941 | 184 |

| New Hampshire | 142 | 29 | 20.4 | 116,964 | 4,033 |

| New Mexico | 324 | 70 | 21.6 | 234,445 | 3,349 |

| New York | 677 | 119 | 17.6 | 464,995 | 3,908 |

| North Carolina | 607 | 90 | 14.8 | 529,336 | 5,882 |

| North Dakota | 350 | 42 | 12.0 | 49,199 | 1,171 |

| Ohio | 587 | 46 | 7.8 | 177,846 | 3,866 |

| Oklahoma | 494 | 40 | 8.1 | 219,036 | 5,476 |

| Oregon | 261 | 57 | 21.8 | 265,705 | 4,661 |

| Pennsylvania | 715 | 96 | 13.4 | 337,094 | 3,511 |

| South Carolina | 260 | 30 | 11.5 | 249,867 | 8,329 |

| South Dakota | 368 | 63 | 17.1 | 114,428 | 1,816 |

| Tennessee | 392 | 12 | 3.1 | 35,425 | 2,952 |

| Texas | 1,061 | 67 | 6.3 | 129,418 | 1,932 |

| Utah | 210 | 37 | 17.6 | 115,222 | 3,114 |

| Vermont | 250 | 66 | 26.4 | 133,475 | 2,022 |

| Virginia | 674 | 102 | 15.1 | 373,983 | 3,667 |

| Washington | 291 | 42 | 14.4 | 278,646 | 6,634 |

| West Virginia | 798 | 75 | 9.4 | 102,244 | 1,363 |

| Wisconsin | 546 | 51 | 9.3 | 226,376 | 4,439 |

| Wyoming | 156 | 41 | 26.3 | 161,361 | 3,936 |

Sample has been trimmed in an attempt to exclude admissions that were for extraordinary care.

Total does not include non-metropolitan ZIP Codes that had no Medicare discharges in 1990.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration: Hospital Market Source Area File, 1990; HCFA Medicare Cost Reports PPSVII, PPSVIII; American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1990.

The mean distance between ZCOP and hospital ZIP Code centroids was 17.7 miles (standard deviation 23.3), and for 81 percent of the ZCOPs the distance to care was 25 or fewer miles. Patients residing in ZCOPs traveled farther, on average, when care was received at a hospital which was located in a metropolitan county as opposed to a non-metropolitan one (see Table 3). Among ZCOPs, 1,997 (88.4 percent) were served by non-metropolitan hospitals. Of these ZCOPs, 86.5 percent were within 25 miles of the provider, with a mean distance to care of 13.94 miles (standard deviation 16.53). The mean distance to care for individuals from ZCOPs who sought care from hospitals located in metropolitan areas was substantially greater at 45.93 miles (standard deviation 41.13) and only 38.9 percent of these ZCOPs were within 25 miles of their provider. Individuals residing in ZCOPs where care was received from an out-of-State hospital were much more likely to receive care from a metropolitan hospital; 31.25 percent of these ZIP Code areas were served by urban hospitals, as opposed to only 10.73 percent of the ZCOPs where care was received from an in-State provider.

Table 3. Distance to Hospital From ZIP Code Areas in Which Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only One Hospital (ZCOPs).

| Distance to Next Nearest Hospital | ZCOPs Served by Rural All ZCOPs | ZCOPs Served by Urban Hospitals | Hospitals |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| n (Percent) | n (Percent) | n (Percent) | |

| 0-5 Miles | 557 (24.7) | 554 (27.7) | 3 (1.1) |

| 6-15 Miles | 844 (37.4) | 797 (39.9) | 47 (17.9) |

| 16-25 Miles | 429 (19.0) | 377 (18.9) | 52 (19.8) |

| Over 25 Miles | 429 (19.0) | 269 (13.5) | 160 (61.1) |

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration: Hospital Market Source Area File, 1990; HCFA Medicare Cost Reports PPSVII, PPSVIII; American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1990.

Consumer Choice

There are several possible reasons why all admissions from a particular ZIP Code area were to only one hospital: (1) lack of access—the next closest hospital may be quite far away, or there may be geographic or social barriers, (2) consumer preferences—there may be another hospital nearby, but for some reason people chose not to use it, (3) physician referral patterns, and (4) restrictions placed by insurers—the majority of individuals within a given ZIP Code may belong to a single health maintenance organization (HMO) or preferred provider organization (PPO) and are not allowed choice of hospital provider. Unfortunately, data limitations preclude assessment of the impact of the last possible explanation, but given that the analysis is of Medicare enrollees, insurer restrictions should play only a minimal role at most.

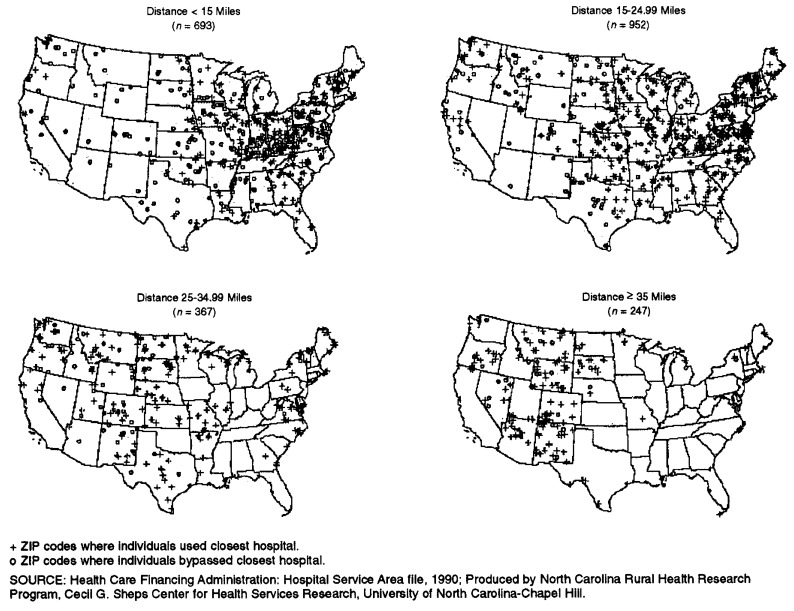

Using straight-line distance measures, rough estimates of the impact of geographic access and either consumer preferences or physician referral patterns on the decision not to seek care from alternative providers can be made. The maps in Figure 1 display the locations of the ZCOP centroids, categorized by the straight-line distance to the closest alternative provider. For 11 percent of the ZCOPs (population 783,551), the next closest hospital was 35 or more miles away, suggesting that, for the individuals residing in these areas, there was no other reasonable choice of provider. The closest alternative provider was between 25 and 35 miles away from 16 percent of the ZCOPs (population 1,247,726), and 73 percent of the ZCOPs had a second hospital within 25 miles. It is important to note that the distances discussed here represent straight-line distances from ZIP Code centroids; the actual distance an individual must travel may be substantially different, as straight-line distances cannot account for road layout and geography.

Figure 1. ZIP Codes In Which Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only One Hospital: Distance To Closest Alternative Hospital, Contiguous United States.

Analysis of the extent to which residents of ZCOPs bypassed closer hospitals sheds light on the possible impact of consumer preferences and/or physician referral patterns. Residents in 626 (27.7 percent) of the ZCOPs did not go to the closest hospital. For these 626 ZCOPs, the mean straight-line distance to the bypassed hospital is 16.1 miles (standard deviation 10.5), while the distance to the hospital which was actually used is 38.0 miles (standard deviation 33.7).4 In contrast, for the 1,633 ZCOPs where discharges are from the closest hospital, residents traveled only 9.9 miles (standard deviation 9.9) on average to receive care, and the mean distance to the next closest alternative is 23.3 miles (standard deviation 12.1). As shown in Figure 1, bypassing behavior was most frequent when the distance to the closest alternative provider was small. These results are expected; as the distance to the closest provider increases, it becomes less likely that an individual would bypass that provider in favor of one even more distant. Due to data limitations, it cannot be determined whether the observed bypassing behavior is a result of consumer preferences, physician referral patterns, or both.

Provider Competition

The residents of the 2,259 ZIP Code areas where Medicare beneficiaries use only 1 hospital were served by 255 hospitals. Of these hospitals, 89 percent were located in non-metropolitan counties. The hospitals serving ZCOPs also served ZIP Code areas where residents received care from more than one hospital. If one were to consider distance to next hospital as a proxy for competition, the analysis seems to indicate that the percentage of a hospital's total admissions accounted for by residents of ZCOPs may be inversely related to the degree of competition that is faced by the hospital. In most of the hospitals which served ZCOPs, residents of these areas accounted for a very small percentage of total admissions, indicating that the hospital competed with at least one other institution for the majority of its patient base. Residents of ZCOPs accounted for less than 5 percent of admissions from 224 of the 255 hospitals. For 19 hospitals, ZCOP residents account for between 5-50 percent of admissions. However, for 12 hospitals serving 45 ZCOPs (population 169,092), over 75 percent of the total admissions were accounted for by patients from the ZCOPs, suggesting a non-competitive market.

Closer inspection of these 12 hospitals reveals that they are all in either Massachusetts or New Hampshire, and many of them are located in geographically inaccessible areas, such as on islands or surrounded by mountains. The total number of beds in these institutions ranges from 31 to 258, with a mean of 96. All of the hospitals have some form of intensive-care unit beds (although often only 2-5), but only one has a cardiac care unit. The occupancy rate in 1987 ranges from 26 to 81 percent, with a mean of 54 percent. Three of the hospitals were designated distressed isolated hospitals by Health Care Investment Analysts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Lewin/ICF, 1991). These hospitals appear to be an anomaly and are not generally representative of any type of hospital.

Impact of Boundary Restrictions

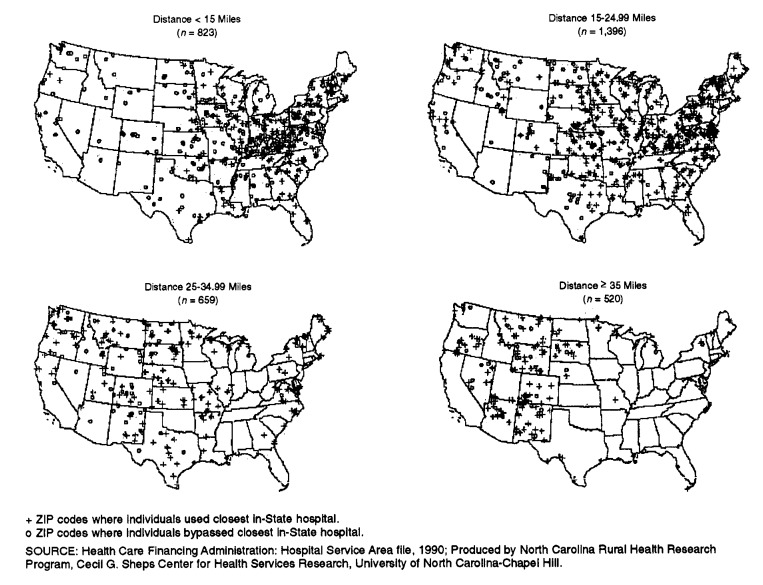

In response to national reform proposals, the issue of State boundaries delimiting managed competition areas has been raised (Comptroller General of the United States, 1994). The relevance of this issue has increased as reform becomes more likely at the State level. To assess the potential impact of restrictions on seeking care in another State, all hospital/patient ZIP Code area pairs where patients crossed State borders to receive hospital care were deleted from the sample. With this restriction in place, the percentage of all non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas that received services from only one hospital rose from 11 to 17.10. In 1990, 10,782,476 persons resided in these restricted ZIP Code areas which used one provider (RZCOPs), a 34-percent increase from the population in ZIP Code areas which used one provider (ZCOPs) without restrictions. Also, when the analysis was restricted to in-State providers, the average distance to the closest alternative provider is greater than in the unrestricted model. The locations of the ZCOP centroids, categorized by the straight-line distance to the closest alternative provider, are shown in Figure 2. For 15 percent of the RZCOPs (as compared with 11 percent of ZCOPs), the next closest in-state hospital was 35 or more miles away. Similarly, the residents of 20 percent of RZCOPs were 25-35 straight-line miles from an alternative provider, as opposed to only 16 percent of the ZCOPs.

Figure 2. ZIP Codes In Which Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only One Hospital If State Border Crossing Is Restricted: Distance To Closest Alternative Hospital, Contiguous United States.

The distribution of RZCOPs across States is shown in Table 4. The impact of restrictions on inter-state care varies substantially across States: Although these restrictions would have almost no impact on the rural residents of Maine and Massachusetts, the rural population which would use one provider would increase by 1,669 percent in Nevada (although the absolute number of affected individuals is fairly small).

Table 4. Restricted Non-Metropolitan ZIP Code Areas in Which Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only One Hospital (RZCOP), by State1.

| State | Total Non-Metropolitan ZIPs in State2 | Number of RZCOPs | RZCOP (Percent) | Population of RZCOPs | Percentage Change With Restriction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 19,833 | 3,398 | 17.0 | 10,782,476 | — |

| Alabama | 357 | 31 | 8.7 | 126,396 | 61 |

| Arizona | 203 | 25 | 12.3 | 108,444 | 31 |

| Arkansas | 539 | 90 | 16.7 | 300,478 | 103 |

| California | 359 | 58 | 16.2 | 174,451 | 129 |

| Colorado | 314 | 76 | 24.2 | 99,518 | 12 |

| Delaware | 40 | 14 | 35.0 | 117,720 | 53 |

| Florida | 232 | 27 | 11.6 | 186,013 | 18 |

| Georgia | 496 | 50 | 10.1 | 381,379 | 21 |

| Idaho | 276 | 68 | 24.6 | 233,614 | 69 |

| Illinois | 810 | 135 | 16.7 | 440,757 | 59 |

| Indiana | 498 | 75 | 15.1 | 332,873 | 08 |

| Iowa | 813 | 80 | 9.8 | 233,139 | 55 |

| Kansas | 597 | 76 | 12.7 | 251,720 | 40 |

| Kentucky | 892 | 170 | 19.1 | 368,728 | 23 |

| Louisiana | 354 | 17 | 4.8 | 61,749 | 54 |

| Maine | 322 | 47 | 14.6 | 78,501 | 0 |

| Maryland | 132 | 78 | 59.1 | 205,198 | 25 |

| Massachusetts | 96 | 22 | 22.9 | 71,542 | 0 |

| Michigan | 558 | 51 | 9.1 | 211,587 | 5 |

| Minnesota | 653 | 130 | 19.9 | 287,510 | 93 |

| Mississippi | 424 | 47 | 11.1 | 230,895 | 19 |

| Missouri | 778 | 74 | 9.5 | 114,384 | 55 |

| Montana | 345 | 81 | 23.5 | 210,490 | 5 |

| Nebraska | 507 | 79 | 15.6 | 232,985 | 12 |

| Nevada | 75 | 29 | 38.7 | 52,015 | 1,669 |

| New Hampshire | 142 | 39 | 27.5 | 131,137 | 12 |

| New Mexico | 324 | 91 | 28.1 | 320,058 | 37 |

| New York | 677 | 152 | 22.5 | 539,552 | 16 |

| North Carolina | 607 | 126 | 20.8 | 590,930 | 12 |

| North Dakota | 350 | 46 | 13.1 | 55,137 | 12 |

| Ohio | 587 | 70 | 11.9 | 311,529 | 75 |

| Oklahoma | 494 | 110 | 22.3 | 372,823 | 70 |

| Oregon | 261 | 74 | 28.4 | 320,170 | 20 |

| Pennsylvania | 715 | 130 | 18.2 | 403,286 | 20 |

| South Carolina | 260 | 41 | 15.8 | 274,740 | 10 |

| South Dakota | 368 | 83 | 22.6 | 138,503 | 21 |

| Tennessee | 392 | 23 | 5.9 | 60,239 | 70 |

| Texas | 1,061 | 67 | 6.3 | 129,672 | 0 |

| Utah | 210 | 45 | 21.4 | 129,292 | 12 |

| Vermont | 250 | 130 | 52.0 | 239,154 | 79 |

| Virginia | 674 | 155 | 23.0 | 504,839 | 35 |

| Washington | 291 | 57 | 19.6 | 325,750 | 17 |

| West Virginia | 798 | 167 | 20.9 | 289,236 | 183 |

| Wisconsin | 546 | 79 | 14.5 | 290,698 | 28 |

| Wyoming | 156 | 83 | 53.2 | 243,645 | 51 |

The sample has been trimmed in an attempt to eliminate admissions for extraordinary care.

Total does not include non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas that had no Medicare discharges In 1990.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration: Hospital Market Source Area file, 1990; HCFA Medicare Cost Reports PPSVII, PPSVIII; American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1990.

In addition, as shown in Table 5, there were 258 ZIP Code areas (population 310,317) where the Medicare beneficiaries used only out-of-state hospitals (hereafter referred to as NIPZAs). If restrictions were placed on crossing State borders to receive hospital services, the residents of these areas would have to develop totally new care-seeking patterns. For 164 of these ZIP Code areas, the closest in-state provider is within 25 miles, implying that factors other than geographic access may account for current border-crossing patterns.

Table 5. ZIP Code Areas Where Medicare Beneficiaries Use Only Hospitals Out of State (NIPZA), by State.

| State | Total ZIPs in State1 | Number of NPZAs | NIPZA (Percent) | Population of NPZAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 19,833 | 258 | 1.3 | 310,317 |

| Alabama | 357 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arizona | 203 | 13 | 6 | 21,883 |

| Arkansas | 539 | 5 | 1 | 4,153 |

| California | 359 | 11 | 3 | 9,377 |

| Colorado | 314 | 1 | 0 | 183 |

| Delaware | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Florida | 232 | 1 | 0 | 199 |

| Georgia | 496 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Idaho | 276 | 3 | 1 | 2,456 |

| Illinois | 810 | 10 | 1 | 28,935 |

| Indiana | 498 | 4 | 1 | 396 |

| Iowa | 813 | 6 | 1 | 4,706 |

| Kansas | 597 | 7 | 1 | 15,675 |

| Kentucky | 892 | 2 | 0 | 1,372 |

| Louisiana | 354 | 1 | 0 | 542 |

| Maine | 322 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maryland | 132 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Michigan | 558 | 9 | 2 | 29,018 |

| Minnesota | 653 | 16 | 2 | 30,570 |

| Mississippi | 424 | 1 | 0 | 598 |

| Missouri | 778 | 16 | 2 | 18,637 |

| Montana | 345 | 4 | 1 | 882 |

| Nebraska | 507 | 9 | 2 | 9,382 |

| Nevada | 75 | 5 | 7 | 3,709 |

| New Hampshire | 142 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Mexico | 324 | 6 | 2 | 275 |

| New York | 677 | 5 | 1 | 3,084 |

| North Carolina | 507 | 4 | 1 | 5,332 |

| North Dakota | 350 | 3 | 1 | 538 |

| Ohio | 587 | 8 | 1 | 3,783 |

| Oklahoma | 494 | 11 | 2 | 23,162 |

| Oregon | 261 | 6 | 2 | 18,867 |

| Pennsylvania | 715 | 5 | 1 | 4,844 |

| South Carolina | 260 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Dakota | 368 | 14 | 4 | 8,470 |

| Tennessee | 392 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Texas | 1,061 | 2 | 0 | 851 |

| Utah | 210 | 2 | 1 | 3,707 |

| Vermont | 250 | 28 | 11 | 25,610 |

| Virginia | 674 | 8 | 1 | 13,679 |

| Washington | 291 | 3 | 1 | 493 |

| West Virginia | 798 | 17 | 2 | 8,902 |

| Wisconsin | 546 | 6 | 1 | 4,612 |

| Wyoming | 156 | 6 | 4 | 1,435 |

Total does not include non-metropolitan ZIP code areas that had no Medicare discharges.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration: Hospital Market Source Area file, 1990; HCFA Medicare Cost Reports PPSVII, PPSVIII; American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1990.

ZIP Code Areas With No Adequate Access

Throughout this analysis, persons living in ZIP Code areas where residents sought care from more than one hospital were not considered as lacking provider choice. This classification is problematic when the distance traveled to all providers is beyond what would be considered accessible. In these cases, although the ZIP Code areas technically exhibited behavior consistent with having provider choice, the distance traveled would suggest otherwise, as any consumer has a choice of providers if they are willing to travel far enough. There were 650 non-metropolitan ZIP Code areas, predominantly in the Western half of the country, where the minimum distance traveled to receive inpatient care was greater than 35 miles. Of these ZIP Code areas, 83 were ZCOPs, where all residents received care from a single hospital. In 179 ZIP Code areas, residents chose between two hospitals, and in 388 ZIP Code areas, three or more hospitals were utilized.

Discussion

The findings can be interpreted as either revealing Medicare beneficiaries' preferences for care or showing that there are apparent, significant restrictions on choice for a substantial portion of the population. The latter is more likely the case. Clearly, the distance to the closest alternative hospital provides insight into the possible lack of choice, but the development of a standard for defining accessibility has not progressed beyond “informed estimates.” Bosanac, Parkinson, and Hall (1976) suggest that 30 minutes travel time to a general hospital defines “accessibility,” a standard supported by the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (1981). Fifteen miles is a common standard used by authors defining hospital markets, with the implicit assumption that this standard also applies to accessibility. Application of any universal standard to national data is problematic, as both perceptions of reasonable travel times and geographic conditions which affect the translation of distance into travel times vary across regions. Another complicating factor is that the definition of accessible is dependent in part upon the types of services which are being sought.

Given that the distance measures in this analysis are all straight-line, and most likely understate the true distance traveled, it seems reasonable to conclude that the 2,031,277 rural ZCOP residents (approximately 7 percent of the rural population) who have been identified as being, on average, 25 miles from an alternative provider do not have a meaningful choice of hospitals. For the 6,046,711 individuals residing in ZCOPs where the straight-line distance, on average, to an alternative provider is less than 25 miles, it is less clear as to whether or not there is an accessible alternative provider. However, even under the most generous assumption—that all 8 million individuals who reside in ZCOPs have no reasonable access to other providers (whether due to geographic, social, or economic obstacles)—the study results only partially support voiced concerns regarding the viability of managed competition in many rural areas. Although 8 million individuals represents a significant portion (approximately 28 percent) of the rural population, it is substantially below the 29 percent of the national total, or 72,125,610 persons, whom Kronick et al. (1993) found would not benefit from competition. Furthermore, although these individuals may not directly participate in a competitive market by exercising a choice of provider, they could still benefit from managed competition. Residents of ZCOPs who receive care from hospitals that compete for other segments of their market (all but 169,092 ZCOP residents) could still receive a cost and quality benefit from managed competition. For this benefit to occur, and because providers are unlikely to lower prices for people from areas where they face little competition, health care reforms must not only include a provision for collective purchasing but must also make sure that ZCOPs are included in purchasing cooperatives that cover areas where residents must use a single provider but maintain some form of bargaining power.

If collective purchasing is included in health care reform, close attention must be paid to areas where patients are currently crossing State or other legislatively-imposed boundaries to receive care. If individuals are allowed to continue to cross boundaries, there are legitimate concerns that hospitals may price discriminate against those patients who reside in areas covered by an agent that differs from that of the hospital's primary market area. Of even greater concern is the possible impact on access to care which could occur if boundary crossing is restricted. The study results, which show that a relatively small, but significant, number of people could be affected by restrictions on boundary crossing, represent the lower bound in terms of the size of the affected population. If States themselves are subdivided, the number of individuals who cross boundaries to receive care will increase (Holahan and Zuckerman, 1993; Yip and Luft, 1993). This shows the difficulty in using any arbitrary political border as a line of service demarcation.

Limitations

The analysis has a number of limitations that merit discussion. First, the distances between ZIP Code centroids, which serve as a proxy for travel time, only provide an approximation of the real distance that must be traveled to receive services, and hence of travel time itself. The precision in the distance estimates is sensitive to differences in ZIP Code land areas, the effect of local geography on travel time, and road configurations. Geographic barriers such as rivers or mountains are not accounted for in the data. Also, the patient's ZIP Code on Medicare files is a mailing address, and so may be different from the ZIP Code of residence. Second, the inability to assign non-metropolitan status at the ZIP Code rather than county level probably results in an underestimation of the number of ZCOPs, RZCOPs, and NIPZAs. Third, when considering the availability of an alternative source of care, the analysis was not able to include information on the characteristics or scope of services of the alternative provider. This may result in an understatement of the number of rural residents who have no reasonable alternative source of care. However, by analyzing actual consumer utilization patterns rather than by simply considering available hospitals, the characteristics of alternative providers are already taken into account, from the perspective of the consumer.

Finally, although the degree to which Medicare data can be generalized to the general population is uncertain, these data have been used by many researchers to draw assumptions about general utilization and have been shown to be generally reliable indicators of trends (Radany and Luft, 1993). Several studies have shown that, within the Medicare population, willingness to travel to receive hospital services decreases with age, but it is not known if this finding can be generalized to the non-Medicare population. One comparison of travel patterns for hospital care of individuals under 65 years of age to those 65 years of age or over suggests there is no significant difference between these age groups, a finding supported by a study comparing Medicare and non-Medicare patient flows in California (Radany and Luft, 1993) and Medicare patients in parts of Minnesota, South Dakota and North Dakota (Adams and Wright, 1991; Adams et al., 1991).

Summary

The potential effects of managed competition on rural areas are:

As many as 8 million rural residents may not receive the benefit of hospital choice.

Individuals who reside in rural areas with limited provider choice could still receive a cost and quality benefit from managed competition if they are included in purchasing cooperatives with areas for whom hospitals compete.

Individuals who reside in rural areas with limited provider choice could have increasing health care costs if they are not included in purchasing cooperatives with areas for whom hospitals compete.

If border-crossing to receive care is restricted, a substantial number of rural residents could be adversely affected.

Policy Implications

This analysis provides critical information for those policymakers who are responsible for health care reform, by showing that there is a way to identify those rural populations currently using one hospital, many of whom will only be able to benefit from managed competition through careful geographic construction of purchasing cooperatives. If reform does not include mechanisms to prevent price discrimination, an integrated service network approach might be the more appropriate mechanism for meeting the needs of these rural populations. Also, the data indicate that there are very serious problems with boundary setting in any system that includes non-metropolitan places. The analysis does show that areas where problems are likely to exist can be identified, and this makes possible the option of providing some systematic alternatives to replace the role of competition in cost control and quality assurance.

This research represents a beginning in the effort to identify those areas that would require special consideration when designing health reform plans that rely on competition and purchasing cooperatives. The next important step is to turn attention towards the provision of primary care, as conclusions regarding hospital service provision may not be applicable to the smaller market areas of primary care.

Table 1. Sensitivity Analyses on Sample Inclusion Criteria: Number of ZIP Code Areas Identified in Each Category.

| Criteria1 | ZCOPs2 (n = 2,259) |

RZCOPs3 (n = 3,398) |

NIPZAs4 (n = 256) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 Miles, 5 Percent | 2,341 | 3,404 | 233 |

| 25 Miles, 10 Percent | 2,572 | 3,721 | 266 |

| 25 Miles, 15 Percent | 2,695 | 3,851 | 279 |

| 35 Miles, 5 Percent | 2,080 | 3,126 | 214 |

| 35 Miles, 10 Percent | 2,466 | 3,617 | 263 |

| 35 Miles, 15 Percent | 2,651 | 3,813 | 279 |

| 50 Miles, 5 Percent | 1,809 | 2,813 | 202 |

| 50 Miles, 10 Percent5 | 2,259 | 3,398 | 258 |

| 50 Miles, 15 Percent | 2,614 | 3,772 | 277 |

| Automatically Include | |||

| 60 Percent of Discharges | 4,168 | 5,324 | 315 |

| 75 Percent of Discharges5 | 2,259 | 3,398 | 258 |

| 85 Percent of Discharges | 1,330 | 2,240 | 203 |

Keep in sample if closer than stated miles and accounts for at least stated percent of discharges.

Limited-choice ZIP Code areas.

Limited-choice ZIP Code areas it border crossing Is restricted.

ZIP Code areas with no In-State provider.

Criterion used In analysis.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration: Hospital Market Source Area File, 1990; HCFA Medicare Cost Reports PPSVII, PPSVIII: American Hospital Association: Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1990.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Don Albert and Karen Johnson-Webb for their cartographic assistance, and to Don Taylor, Jane Kolimaga, Bob Konrad, Glenn Wilson, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under Grant Number CRS000002. Rebecca T. Slifkin, Hilda A. Howard, and Thomas C. Ricketts III are with the Rural Health Research Program, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Ricketts is also with the Department of Health Policy and Administration of the same university. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policy positions of the University of North Carolina, DHHS, or Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA).

The degree to which this categorization is problematic depends in part on the size of the county. Of particular concern are large counties in the Western United States which are designated metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) but will be mostly rural.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the robustness of the study results to changes in the sample inclusion criteria. Details are presented in Table 1. After observations accounting for the first 75 percent of discharges were included in the sample, changing the criteria for inclusion or exclusion of subsequent observations had only minimal effect on the number of ZIP Code areas which are relevant to the analyses. However, changing the threshold total percentage of discharges that were automatically included in the sample resulted in dramatic differences in the number of relevant ZIP Code areas. This finding implies that there are many ZIP Code/hospital pairs which each account for only a small percentage of the total ZIP Code discharges and which also include ZIP Code to hospital distances greater than 50 miles.

This figure may be an underestimation of the total population residing in ZCOPs. Some ZIP Code areas had zero population reported in the census, with individuals who used this ZIP Code counted in the population of surrounding ZIP Codes areas. To the extent that surrounding ZIP Code areas are also ZCOPs, the reported total ZCOP population is accurate. If none of the surrounding ZIP Code areas are ZCOPs, the total population in ZCOPs would increase by approximately 374,000 (population estimates from Demographics, U.S.A.).

A sample of these ZIP Code areas were individually examined to determine if there were geographic obstacles which prevented residents from utilizing the hospital which was “closest” according to straight-line distance calculations. This was not found to be the case. What was found was that many of these areas had easy access to a major highway that linked them to a larger urban area.

Reprint Requests: Rebecca T. Slifkin, Ph.D., Rural Health Research Program, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 725 Airport Road, CB# 7590, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7590.

References

- Adams K, Wright G. Hospital Choice of Medicare Beneficiaries in a Rural Market: Why Not the Closest? The Journal of Rural Health. 1991;7:134–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1991.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams K, Houchens R, Wright G, Robbins J. Predicting Hospital Choice for Rural Medicare Beneficiaries: The Role of Severity of Illness. Health Services Research. 1991;26:583–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosanac E, Parkinson R, Hall D. Geographic Access to Hospital Care: A 30-Minute Travel Time Standard. Medical Care. 1976;14:616–624. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson J, Moscovice I. Health Care Reform and Rural Health Networks. Health Affairs. 1993 Fall;12:59–80. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.3.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comptroller General of the United States. Health Care Alliances: Issues Relating to Geographic Boundaries. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Accounting Office; 1994. Report No. GAO/HEHS-94-139. [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven A, Kronick R. A Consumer-Choice Health Plan for the 1990s. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320:29–37. 94–101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B. Health Care Reform: Managed Competition in Rural Areas. Congressional Research Service; Apr, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goody B. Defining Rural Hospital Markets. Health Services Research. 1993;28:183–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee. Summary Report of the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee. Washington DC: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan J, Zuckerman S. Border Crossing for Physician Services: Implications for Controlling Expenditures. Health Care Financing Review. 1993;15:101–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronick R, Goodman D, Wennberg J, Wagner E. The Marketplace in Health Care Reform: The Demographic Limitations of Managed Competition. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;328:148–152. doi: 10.1056/nejm199301143280225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radany M, Luft H. Estimating Hospital Admission Patterns Using Medicare Data. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;37:1431–1439. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services and Lewin/ICF. Access to Care in Areas Served by Isolated Rural Hospitals. Washington, D.C.: 1991. Report No. ASPE/HP 89-001, PB91-183574. [Google Scholar]

- Yip W, Luft H. Border Crossing for Hospital Care and Its Implications for the Use of Statewide Data. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;36:1455–1465. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90387-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]