Abstract

During the 1990s, growth in health care costs slowed considerably, helping to lessen the spending strain on business, government, and households. Although cost growth has slowed, the Federal Government continues to pay an ever-increasing share of the total health care bill. This article reviews important health care spending trends, and for the first time, provides separate estimates of the employer and employee share of the premium costs for employer-sponsored private health insurance. This article also highlights some of the emerging trends in the employer-sponsored insurance market, including managed care, cost-sharing, and employment shifts.

Introduction

In 1994, national health expenditures (NHE) consumed 13.7 percent of the gross domestic product (Levit et al., 1996), reaching $949.4 billion. The 6.4-percent growth from the previous year was the slowest growth in more than 3 decades.

The analysis presented in this article builds on the national health accounts (NHA), which present spending by health care bill payers such as Medicaid, Medicare, and private health insurance. The NHA estimates are rearranged and disaggregated to permit an examination of sponsors of health care who provide funding to bill payers. These major sponsors of health care are business, households, and governments, with a small amount of revenue coming from non-patient revenue sources, such as philanthropy. Sponsors' spending is measured as expenditures for health services and supplies (HSS) that represent the cost of health care excluding research and construction. Some payments for HSS by sponsors pass through health care bill payers such as insurance and government, while other payments flow directly into the health care system. In this article, one additional layer (a breakdown of business and household) is revealed beyond those presented in NHA. Ultimately, however, the individual bears the primary responsibility of paying for health care through health insurance premiums, out-of-pocket costs, philanthropic contributions to health organizations, income taxes, earnings reduced by employers' health insurance costs, and higher costs of products.

In 1994, $919.2 billion was spent on HSS (Table 1). The private sector, which includes business, households, and non-patient revenues, accounted for 63 percent ($577.3 billion) of HSS. The public sector accounted for the remaining 37 percent ($342.0 billion). Expenditures by the public sector include only general revenue1 expenditures by Federal, State, and local governments. These expenditures include funding of health care programs and government employer contributions to health insurance plans and to the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund for their employees.

Table 1. Health Services and Supplies, by Sponsor: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1965-94.

| Type of Sponsor | 1965 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| Total | $37.7 | $67.9 | $122.3 | $235.6 | $411.8 | $672.9 | $736.3 | $806.0 | $863.1 | $919.2 |

| Private | 29.8 | 48.9 | 83.7 | 158.4 | 282.2 | 450.8 | 481.9 | 520.1 | 544.2 | 577.3 |

| Private Business | 5.9 | 13.6 | 27.5 | 61.7 | 108.6 | 185.8 | 198.2 | 215.9 | 226.8 | 241.3 |

| Household (Individual) | 23.2 | 33.8 | 53.8 | 89.5 | 160.5 | 245.3 | 262.2 | 281.9 | 292.9 | 310.1 |

| Non-Patient Revenue | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 13.1 | 19.8 | 21.5 | 22.3 | 24.4 | 25.9 |

| Public | 7.9 | 19.0 | 38.6 | 77.3 | 129.6 | 222.1 | 254.4 | 285.9 | 318.9 | 342.0 |

| Federal Government | 3.4 | 10.4 | 21.2 | 42.4 | 68.4 | 115.1 | 136.2 | 159.7 | 181.1 | 190.6 |

| State and Local Government | 4.5 | 8.6 | 17.4 | 34.8 | 61.2 | 107.0 | 118.2 | 126.2 | 137.8 | 151.3 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Private | 79 | 72 | 68 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 63 |

| Private Business | 16 | 20 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 |

| Household (Individual) | 62 | 50 | 44 | 38 | 39 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 34 | 34 |

| Non-Patient Revenue | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Public | 21 | 28 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 35 | 35 | 37 | 37 |

| Federal Government | 9 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 21 |

| State and Local Government | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics, 1965-94.

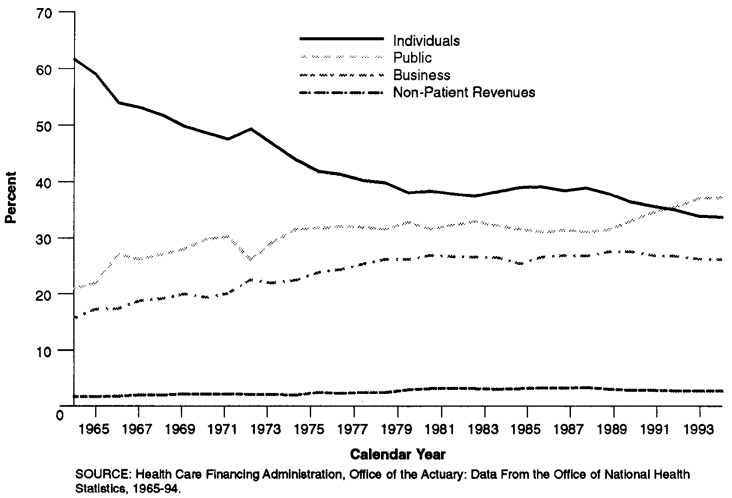

From 1965 to 1990, the household share of HSS fell from 62 percent to 36 percent. From 1965 to 1990, both the business and public sector shares grew, from 16 percent to 28 percent and 21 percent to 33 percent, respectively. Between 1990 and 1994, household and business shares each fell 2 percentage points. At the same time, the share paid by the public sector rose 4 percentage points, the most rapid increase since 1975. In 1992, the public share of expenditures for HSS exceeded the household share for the first time.

Business Sector

Health spending by private business grew to $241.3 billion in 1994. This is an increase of 6.6 percent from the prior year. Business health spending accounted for 26 percent of HSS (Table 1). This share grew from 1965 to 1989 but decreased slightly from 1990 to 1994 (Figure 1). The majority of private business spending was for the employer share of private health insurance premiums and contributions to the Medicare HI Trust Fund. Payments for programs such as workers' compensation, temporary disability insurance, and industrial inplant services also are included.

Figure 1. Percent of Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies, by Sponsor: United States 1965-94.

In 1994, premiums for employer-sponsored private health insurance cost business $179.5 billion, 5.6 percent more than the previous year (Table 2). The 5.6-percent growth rate for premiums was the slowest since 1965 and continued a trend of declining growth that began in 1992. Since 1991, enrollment in private health insurance has declined, and growth in health care costs has decelerated (Levit et al., 1996).

Table 2. Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies, by Sponsor: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1965-94.

| Type of Sponsor | 1965 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| Total | $37.7 | $67.9 | $122.3 | $235.6 | $411.8 | $672.9 | $736.3 | $806.0 | $863.1 | $919.2 |

| Private | 29.8 | 48.9 | 83.7 | 158.4 | 282.2 | 450.8 | 481.9 | 520.1 | 544.2 | 577.3 |

| Private Business | 5.9 | 13.6 | 27.5 | 61.7 | 108.6 | 185.8 | 198.2 | 215.9 | 226.8 | 241.3 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 4.9 | 9.7 | 19.7 | 45.3 | 79.1 | 138.4 | 146.6 | 160.4 | 170.0 | 179.5 |

| Employer Contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund | 0.0 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 10.5 | 20.3 | 29.5 | 32.5 | 34.4 | 35.6 | 40.3 |

| Workers' Compensation and Temporary Disability Insurance | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 15.7 | 16.7 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 18.3 |

| Industrial Inplant Health Services | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| Household | 23.2 | 33.8 | 53.8 | 89.5 | 160.5 | 245.3 | 262.2 | 281.9 | 292.9 | 310.1 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums and Individual Policy Premiums | 4.7 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 14.6 | 30.7 | 51.3 | 57.4 | 63.6 | 68.2 | 70.6 |

| Employee and Self-Employment | ||||||||||

| Contributions and Voluntary Premiums Paid to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund1 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 5.7 | 12.0 | 24.1 | 35.5 | 39.4 | 41.9 | 43.4 | 50.5 |

| Premiums Paid by Individuals to Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 11.9 | 14.2 |

| Out-of-Pocket Health Spending | 18.5 | 24.9 | 38.1 | 60.3 | 100.6 | 148.4 | 155.1 | 164.4 | 169.4 | 174.9 |

| Non-Patient Revenues | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 13.1 | 19.8 | 21.5 | 22.3 | 24.4 | 25.9 |

| Public | 7.9 | 19.0 | 38.6 | 77.3 | 129.6 | 222.1 | 254.4 | 285.9 | 318.9 | 342.0 |

| Federal Government | 3.4 | 10.4 | 21.2 | 42.4 | 68.4 | 115.1 | 136.2 | 159.7 | 181.1 | 190.6 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 11.9 |

| Employer Contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Adjusted Medicare | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 10.5 | 18.4 | 29.8 | 32.5 | 41.4 | 51.3 | 53.5 |

| Medicare2 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 16.2 | 37.2 | 71.7 | 110.9 | 121.4 | 136.7 | 149.4 | 166.1 |

| Less Medicare Hospital Trust Fund Contributions and Premiums | 0.0 | 4.8 | 11.5 | 24.0 | 48.2 | 71.0 | 78.5 | 83.3 | 86.3 | 98.4 |

| Less Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Premiums | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 11.9 | 14.2 |

| Health Program Expenditures (Excluding Medicare) | 3.3 | 8.2 | 16.9 | 29.4 | 44.2 | 74.0 | 91.7 | 105.4 | 116.1 | 122.9 |

| Medicaid3 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 14.7 | 23.1 | 43.4 | 57.8 | 69.5 | 78.0 | 83.4 |

| Other Programs4 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 14.7 | 21.1 | 30.6 | 34.0 | 36.0 | 38.1 | 39.6 |

| State and Local Government | 4.5 | 8.6 | 17.4 | 34.8 | 61.2 | 107.0 | 118.2 | 126.2 | 137.8 | 151.3 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 7.6 | 18.2 | 33.5 | 38.1 | 41.9 | 46.7 | 51.3 |

| Employer Contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| Health Expenditures by Program | 4.2 | 7.6 | 14.6 | 25.9 | 40.8 | 69.5 | 75.7 | 79.5 | 86.2 | 94.8 |

| Medicaid3 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 6.1 | 11.7 | 18.6 | 33.2 | 37.9 | 39.4 | 43.7 | 49.1 |

| Hospital Subsidies | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 11.8 | 11.8 |

| Other Programs | 4.2 | 5.1 | 8.4 | 14.2 | 22.2 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 40.1 | 42.4 | 45.7 |

Includes one-half of self-employment contribution to Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and taxation of Social Security benefits.

Excludes Medicaid buy-in premiums for Medicare.

Includes Medicaid buy-in premiums for Medicare.

Includes maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Indian Health Service, Office of Economic Opportunity (1965-74), Federal workers' compensation, and other miscellaneous general hospital and medical programs, public health activities, Department of Defense, and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Includes other public and general assistance, maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, public health activities, and hospital subsidies.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics, 1965-94.

Influence of Managed Care

As more employees switched to managed care plans, growth in employer-sponsored premiums started to decelerate. Managed care plans typically charge lower average premiums than traditional indemnity plans (Foster Higgins, 1994; KPMG Peat Marwick, 1991-95) by controlling provider costs and utilization of services. At the same time, employers were able to pass a higher share of total premiums to their employees.

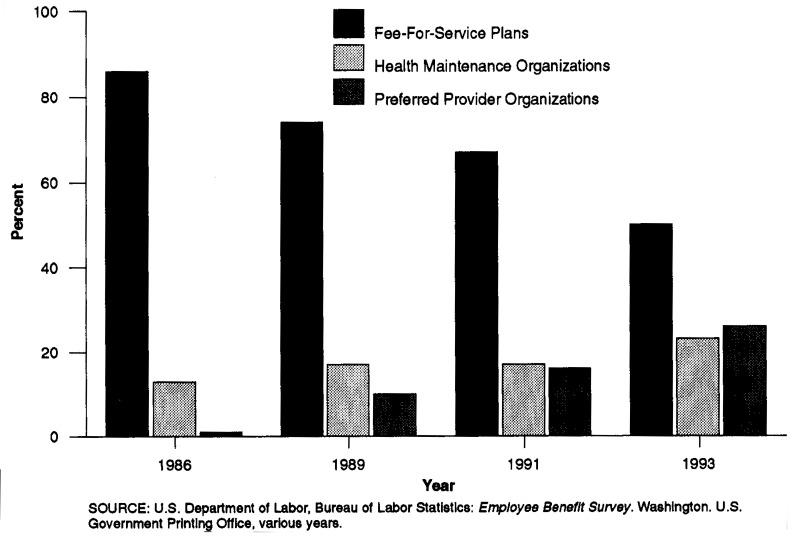

In 1986, almost 90 percent of health plan participants in medium and large firms2 enrolled in traditional fee-for-service plans; however, by 1993, the number of participants had dropped to 50 percent (Figure 2). Enrollment in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), typically the most restrictive of the managed care plans, grew from 13 percent to about 23 percent of all plan participants between 1986 and 1993.

Figure 2. Percent Distribution of Enrollment by Type of Health Care Plan in Medium and Large Private Establishments: Selected Calendar Years, 1986-93.

The fastest growing type of managed care plan was the preferred provider organization (PPO). These plans grew from 1 percent of health plan participants in 1986 to 26 percent in 1993 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994a). PPOs attempt to lower costs by selecting providers that meet their criteria, which could range from location to specialty to practice patterns. Then PPOs negotiate a fee schedule with these providers. Many traditional fee-for-service plans now generate a list of pr ferred providers for participants. The advantage to the participant for using the preferred provider is lower out-of-pocket costs.

Contributions to Medicare

The Medicare HI Trust Fund is primarily financed through Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes. The trust fund is used to pay for inpatient hospital care and other related services for 32 million aged and 4 million disabled persons covered by Medicare. Employer contributions to the Medicare HI Trust Fund reached $40.3 billion in 1994. Employees and employers each contribute at a rate of 1.45 percent of the taxable earnings. Self-employed persons contribute at a rate of 2.90 percent.

The significant increase in contributions for 1994 (13.3 percent) was a result of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1993, which removed the cap on the maximum taxable amount of annual earnings. Before OBRA 1993, contributions by employees, employers, and self-employed persons were based on wages and salaries up to $135,000 (the maximum taxable amount of earnings in 1993). The change in OBRA 1993 allows for all earnings in covered employment to be subject to the HI contribution rate (Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 1995).

Other Business Spending

Workers' compensation and temporary disability insurance contributed a total of $18.3 billion in 1994 to business health care costs. Recently, there have been major changes to workers' compensation laws aimed at controlling costs. In 1993, changes included the introduction of managed care plans in 12 States and the passage of legislation allowing or requiring deductibles to be written into workers' compensation insurance policies in 7 States (Berreth, 1994). Industrial inplant services, facilities, or supplies provided by employers for the health care needs of their employees were $3.0 billion in 1994.

Business Share and Burden

In 1965, business paid for 16 percent of total HSS. By 1990, the share had grown to 28 percent. However, since 1990, the business share has decreased slightly, from 28 percent to 26 percent, reversing the 25-year trend. The share has declined as business tries to control their health care costs.

Covered Services.

Over the past decade, the breadth of services covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance has expanded. Much of this expansion was driven by strategies for cost containment. During the mid-1980s, the proportion of employees with coverage for substance abuse, home health care, and hospice care increased (Table 3). Many employers added coverage for substance abuse to their medical plans to reduce long-term medical costs and improve worker productivity (Kronson, 1991). However, the rise in substance-abuse coverage was also partly the result of State-legislated mandates that required insurers to provide alcohol and drug-treatment benefits. At the same time, an increasing number of insurance plans offered home health care and hospice care coverage as less expensive alternatives to hospital stays. The proportion of employees with coverage for home health care benefits almost doubled, from 44 percent in 1984 to 86 percent in 1993 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994a)

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the continued focus on cost containment led employers to accelerate the shift toward managed care health plans, including HMOs, PPOs, and POS plans. With that shift came an expansion in preventive services. Examples of common preventive services include routine physical examinations, well-baby care, well-child care, and immunizations and inoculations.

Data from KPMG Peat Marwick (1991-95) indicate that even conventional fee-for-service plans, which have traditionally covered few preventive services, have greatly expanded their coverage during the 1990s. For example, from 1992 to 1994, the proportions of employees covered for adult physicals, well-baby care, and well-child care in surveyed conventional fee-for-service plans all increased by more than one-third. However, despite such increases, these conventional plans still lag most managed care plans (particularly HMOs) in the overall level of preventive-services coverage.

Burden is a gauge of a sector's ability to pay for health care, using a comparison of health spending against capacity to pay these costs. In the business sector, burden measures such as business health spending as a percent of labor compensation and profits have either declined or stabilized in recent years (Table 4). Business health spending as a portion of total compensation grew from 1.8 percent in 1965 to 7.5 percent in 1992 and maintained that share through 1994. Another measure, business health spending as a percent of corporate profits,3 declined from 1993 to 1994. Business attempted to control its rising health care costs by switching to managed care plans and shifting costs to employees. These strategies, along with other marketplace changes (such as decelerating growth in benefit costs) seem to have stopped (or at least temporarily reversed) the rising impact of health care costs on business.

Table 4. Private Business Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies as a Percent of Business Expense or Profit: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1965-94.

| Year | Business Health Spending as a Share of | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Labor Compensation1,2 | Corporate Profits2,3 | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Total Compensation | Wages and Salaries | Fringe Benefits | Before Tax | After Tax | |

|

| |||||

| Percent | |||||

| 1965 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 20.4 | 7.5 | 12.4 |

| 1970 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 26.4 | 17.3 | 30.9 |

| 1975 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 27.3 | 19.6 | 30.8 |

| 1980 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 29.9 | 25.6 | 39.5 |

| 1985 | 5.7 | 6.8 | 36.9 | 48.8 | 85.4 |

| 1990 | 7.0 | 8.3 | 43.1 | 50.8 | 81.8 |

| 1991 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 43.5 | 54.3 | 84.7 |

| 1992 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 44.0 | 54.5 | 84.3 |

| 1993 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 43.2 | 49.1 | 78.4 |

| 1994 | 7.5 | 9.1 | 43.1 | 46.0 | 74.9 |

For employees in private Industry.

Based on January 1996 data from the U.S. Department of Commerce national income and product accounts.

A similar concept of “profits” for sole proprietorship and partnerships is not available.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics, 1965-94.

Real Compensation

Since 1993, growth rates of real total compensation and employer health expenditures have moderated. Real total compensation per private and government employee grew at a 0.8-percent average annual rate from 1965 to 1992 (Table 5). The health care component of real total compensation grew at an average annual rate of 6.3 percent for the same period. From 1992 to 1994, however, growth in real total compensation slowed to 0.4 percent, while the employer health component grew only 1.6 percent. Despite slower growth in employer health costs, real health care expenditures per employee continued the historic trend of consuming more of real compensation through 1994. However, data from the March 1996 Employment Cost Index show that there may be a reversal of this trend, as wages and salaries grew faster than health benefits (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1996b).

Table 5. Economywide Real Compensation per Employee1 and Average Annual Growth: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1965-94.

| Year | Real Compensation | Full-Time and Part-Time Employees (in Thousands) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total Compensation | Wages and Salaries | Fringe Benefits | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | Employer Health Expenditures2 | Pension Payments3 | Other4 | ||||

| 1965 | $18,098 | $16,419 | $1,679 | $327 | $968 | $383 | 69,877 |

| 1970 | 19,824 | 17,675 | 2,150 | 478 | 1,290 | 381 | 80,003 |

| 1975 | 20,555 | 17,644 | 2,911 | 689 | 1,755 | 467 | 85,347 |

| 1980 | 19,975 | 16,734 | 3,241 | 890 | 1,844 | 507 | 99,233 |

| 1985 | 20,776 | 17,344 | 3,432 | 1,180 | 1,806 | 446 | 107,133 |

| 1990 | 21,648 | 17,901 | 3,747 | 1,526 | 1,785 | 436 | 119,413 |

| 1991 | 21,782 | 17,918 | 3,864 | 1,604 | 1,822 | 437 | 117,503 |

| 1992 | 22,219 | 18,217 | 4,003 | 1,693 | 1,872 | 438 | 117,998 |

| 1993 | 22,211 | 18,150 | 4,062 | 1,717 | 1,900 | 444 | 120,011 |

| 1994 | 22,302 | 18,183 | 4,119 | 1,746 | 1,940 | 434 | 122,981 |

| Average Annual Growth Rates | |||||||

| 1965-70 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 5.1 | 7.9 | 5.9 | -0.1 | 2.7 |

| 1970-75 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 1.3 |

| 1975-80 | -0.6 | -1.1 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 3.1 |

| 1980-85 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 5.8 | -0.4 | -2.5 | 1.5 |

| 1985-90 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 5.3 | -0.2 | -0.5 | 2.2 |

| 1990-91 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 2.0 | 0.4 | -1.6 |

| 1991-92 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 1992-93 | 0.0 | -0.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| 1993-94 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | -2.4 | 2.5 |

| 1965-92 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| 1992-94 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | -0.5 | 2.1 |

| Cumulative Growth Rates | |||||||

| 1965-70 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 28.0 | 46.0 | 33.2 | -0.5 | 14.5 |

| 1970-90 | 9.2 | 1.3 | 74.3 | 219.1 | 38.4 | 14.2 | 49.3 |

| 1990-94 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 9.9 | 14.4 | 8.6 | -0.5 | 3.0 |

| 1965-94 | 23.2 | 10.7 | 145.3 | 433.1 | 100.4 | 13.1 | 76.0 |

Includes compensation for private industry and Federal and State and local governments per full-time and part-time employee, deflated using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers.

Includes employer contribution to health insurance premiums and to Medicare Trust Funds, and workers' compensation and temporary disability insurance.

Includes private and public pension plans, old age, survivors, and disability insurance (Social Security), railroad, and pension benefit guaranty.

Includes employer contribution to unemployment insurance, life insurance, corporate director's fees, and several minor categories of employee compensation.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary, Office of National Health Statistics; U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of Economic Analysis; and U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1965-94.

Household Sector

Households spent $310.1 billion on health care in 1994—an increase of 5.3 percent from the previous year. Household expenditures include the employee share of employer-sponsored and individually purchased private health insurance ($70.6 billion). Additionally, households paid premiums, contributed to the Medicare trust funds ($64.7 billion), paid out-of-pocket costs for health care services not covered by insurance, and paid deductibles and copayments ($174.9 billion).

The share of HSS paid by households has been declining, from 62 percent in 1965 to 34 percent in 1994. Since 1988, this decline in share for households has been more rapid than for the previous 10 years (Figure 1). This decline is related to a deceleration in the growth rates for household-paid private health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs for services (Table 6). Growth in private health insurance premiums decelerated from 19.7 percent in 1988 to 3.5 percent in 1994. Growth in out-of-pocket payments by households, like private health insurance premiums, decelerated during the 1988-94 period, from 11.3 percent in 1988 to 3.2 percent in 1994. Growth in private health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket payments decelerated at the same time that managed care plan enrollment was growing (Figure 2). These plans typically have lower premiums and lower out-of-pocket costs than traditional indemnity plans.

Table 6. Growth in Components of Household Health Care Spending: United States, Calendar Years 1988-94.

| Component | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | Average Annual Growth 1988-94 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Percent | ||||||||

| Household Health Care Spending | 13.1 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 6.8 |

| Insurance Premiums | 19.7 | 14.4 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 10.9 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 9.9 |

| Medicare Contributions and Premiums | 12.4 | 12.1 | 1.8 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 2.6 | 116.9 | 8.4 |

| Out-of-Pocket | 11.3 | 5.4 | 9.0 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 5.2 |

The significant increase in contributions from the previous year is a result of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1993, which removed the cap on the maximum taxable amount of annual earnings.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics, 1988-94.

Growth in household spending for Medicare premiums and contributions generally decelerated from 1988 through 1993. In 1994, however, the removal of the maximum taxable earnings cap and an increase in the taxation of Social Security benefits caused household payments to Medicare to increase.

Household Burden

The household burden, as measured by comparing household health care spending to adjusted personal income, remained stable from 1992 to 1994. During this period, out-of-pocket spending for premiums and health care services and supplies was 5.7 percent of adjusted personal income (Table 7). Previously, from 1984 to 1991, household health spending had grown steadily faster than income, consuming 4.6 percent of adjusted personal income in 1984 and rising to 5.6 percent in 1991.

Table 7. Expenditures for Health as a Percent of Household (Individual) Income: United States, Calendar Years 1984-94.

| Year | Household Health Spending as a Share of | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Adjusted Personal Income2 | Income After Taxes1 | |||

|

| ||||

| All Ages | Reference Person 65 Years of Age or Over3 | Reference Person Under 65 Years of Age3 | ||

| 1984 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 11.3 | 4.0 |

| 1985 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 11.0 | 3.9 |

| 1986 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 11.8 | 4.6 |

| 1987 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 10.7 | 3.6 |

| 1988 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 12.5 | 3.8 |

| 1989 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 11.5 | 3.9 |

| 1990 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 12.5 | 4.0 |

| 1991 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 12.2 | 4.0 |

| 1992 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 12.6 | 4.1 |

| 1993 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 13.6 | 4.3 |

| 1994 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 11.9 | 4.1 |

Calculated from the Consumer Expenditure Integrated Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In this survey, the Institutionalized population, including nursing home residents, was excluded, therefore spending for nursing home care in the Consumer Expenditure Survey covers only a small portion of total days of care.

Personal income adjusted to include personal Medicare contributions and to exclude certain transfer payments (Medicaid, workers' compensation, and temporary disability insurance).

Consumer expenditure data are tabulated by age of reference person. Therefore, households may include members who are in a different age category than the reference person. For example, a person who is under age 65 years of age and lives in a household with a reference person 65 years of age or over is included with those over 65 in the household.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics; U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1984-94.

The elderly continue to bear a larger health care burden than the non-elderly (who have experienced very little change in burden in the 1990s). Households with reference persons4 65 years of age or over spent more of their after-tax income on health care costs (11.9 percent) in 1994 than households headed by non-aged persons. The elderly use more health services than the non-elderly population and incur more out-of-pocket costs, especially for some care not covered by Medicare (primarily prescription drugs).

Public Sector

Health care expenditures by Federal, State, and local governments reached $342.0 billion in 1994, exceeding spending by either the business or household sectors (Table 1). From 1965 to 1994, the share of HSS paid by governments grew from 21 percent to 37 percent, surpassing the individual share in 1992. Government bears the largest share of health care costs for several reasons. First, the public sector is frequently the insurer of the most vulnerable portions of the population: the aged, the disabled, and the poor. The democratic process also makes it more difficult for the government to respond quickly to marketplace changes. As the government share of health care costs has increased, health care has become one of the most hotly debated topics in the political arena.

Government expenditures are those for health care spending in Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs facilities; grants for needy population groups, such as the elderly, the poor, mothers and children, American Indians, school children, and the disabled; public health activities; and State and local government hospital subsidies. Only the general revenue contributions and interest income in support of programs such as Medicare are included, while dedicated tax revenues paid into the trust funds for specific programs are excluded. Also included are expenditures that governments pay on behalf of their employees for health care.

Federal Government Share and Burden

The Federal Government spent $193.6 billion of general revenues for health care in 1994, an increase of 6.3 percent from the previous year. Federal Government health care expenditures grew from 9 percent of HSS in 1965 to 21 percent in 1994. The two largest federally funded health care programs, Medicare (adjusted to exclude premiums and tax revenues) and Medicaid, accounted for the majority (71.8 percent) of spending by the Federal Government.

Federal expenditures for health care consume almost one-quarter of all Federal revenues. From 1965 to 1992, the Federal sector burden grew from 3.5 of revenues to 23.3 percent. Since 1992, the percent of revenues paid by the Federal Government for health care has remained between 23.1 percent and 24.2 percent (Table 8). The recently observed stability in the burden measures results from acceleration in Federal revenue growth and deceleration in Medicaid general revenue spending.

Table 8. Expenditures for Health as a Percent of Federal, State, and Local Government Revenues: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1965-94.

| Year | Federal Government Health Spending as a Share of Federal Revenues2 | State and Local Government Health Spending as a Share of State and Local Revenues1 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Percent | ||

| 1965 | 3.5 | 8.0 |

| 1970 | 7.3 | 9.0 |

| 1975 | 11.0 | 11.3 |

| 1980 | 11.6 | 14.3 |

| 1985 | 14.3 | 15.9 |

| 1990 | 17.3 | 19.8 |

| 1991 | 20.5 | 20.8 |

| 1992 | 23.3 | 20.8 |

| 1993 | 24.2 | 21.6 |

| 1994 | 23.1 | 22.4 |

Excludes contributions to social Insurance because these came directly from businesses and individuals. These funds are for dedicated purposes and are not part of the general revenue pool of funds from which health spending can be financed. Based on January 1996 data from the U.S. Department of Commerce national income and product accounts.

Excludes contribution to social Insurance, as explained in footnote 1, and Federal grants in aid, such as Federal Medicaid grants to States. Based on January 1996 data from the U.S. Department of Commerce national income and product accounts.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics, 1965-94; U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, January 1996

State and Local Government Share and Burden

State and local governments spent $151.3 billion on health care in 1994, accounting for 16 percent of HSS. The burden felt by State and local governments has increased since 1965: Health care spending rose from 8.0 percent of revenues to 22.4 percent of revenues in 1994. Despite efforts to control costs, State revenues have not kept pace with rising health care costs.

State and local government responsibility for contributing to health insurance premiums for their employees is adding to the strain on State and local government resources. In 1994, employer contributions to private health insurance premiums accounted for one-third of State and local health expenditures. From 1985 to 1992, expenditures for employer-sponsored health insurance premiums grew from 30 percent of State and local expenditures to 34 percent, while Medicaid spending in relation to State and local health expenditures remained relatively constant. The increase in the share of expenditures for employer-sponsored insurance came even though State and local governments steered more of their workforce into managed care plans and increased employee premiums (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1995a).

Medicaid

Medicaid, funded by both the Federal and State and local governments, experienced large spending growths during 1990 and 1991, followed by a deceleration in growth from 1992 to 1994. The increases were the result of changes in the Federal requirements for increased coverage of women and children and other categories of enrollees; increases in the number of people eligible as a result of the economic slowdown in 1990 and 1991; and increases in payments for disproportionate-share hospitals. In 1991, legislation was passed to curb the increases in Medicaid costs resulting from tax-and-donation schemes and payments for disproportionate-share hospitals. These changes became effective in 1994.

Other changes have been taking place in the Medicaid program during the 1990s. The Medicaid program was established as a fee-for-service system, allowing recipients freedom of choice. In the 1990s, through various waiver programs,5 States have been able to develop and implement managed care programs. Following the trend of private business, many States have been enrolling Medicaid recipients in managed care programs to control costs, foster a patient-provider relationship for recipients, and provide continuity of care. From 1991 to 1994, the percent of Medicaid recipients enrolled in managed care plans grew from 9.5 percent to 23.2 percent (Health Care Financing Administration, 1995).

Non-Patient Revenues

Non-patient revenues funded 3 percent of all health care spending in 1994, a share maintained since 1979. Non-patient revenues consist of philanthropic expenditures for health care services and other revenue sources of institutions, such as hospitals, home health agencies, and nur ing homes, that are not directly associated with the delivery of services. The sources include revenues from gift shops, cafeterias, and parking lots. In 1994, $25.9 billion of health expenditures were funded from this source.

Private Health Insurance Premiums

Of the $919.2 billion spent for HSS in the United States in 1994, more than one-third ($313.3 billion) was spent on private health insurance premiums (Table 9). Total private health insurance premium spending was up 5.7 percent from 1993. However, since 1989, the annual growth rate for premiums has fallen by almost two-thirds. This downward trend reflects changes in health insurance plan costs as well as private health insurance enrollment. Although the growth in managed care dampened the increase in the average premium cost of health insurance plans, overall enrollment in private health insurance actually declined (Levit et al., 1996).

Table 9. Expenditures of Private Health Insurance, by Sponsor: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1987-94.

| Sponsor | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||

| Total Private Health Insurance Premiums | $152.1 | $175.1 | $203.8 | $232.4 | $251.9 | $276.6 | $296.5 | $313.3 |

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums | 139.1 | 159.4 | 186.6 | 214.5 | 232.0 | 253.4 | 272.3 | 290.3 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 118.6 | 135.0 | 157.9 | 181.1 | 194.5 | 213.0 | 228.2 | 242.7 |

| Federal | 4.9 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 11.9 |

| Non-Federal | 113.7 | 128.6 | 149.8 | 171.9 | 184.7 | 202.3 | 216.7 | 230.8 |

| Private1 | 92.8 | 104.1 | 121.4 | 138.4 | 146.6 | 160.4 | 170.0 | 179.5 |

| State and Local | 21.0 | 24.5 | 28.4 | 33.5 | 38.1 | 41.9 | 46.7 | 51.3 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 20.5 | 24.4 | 28.7 | 33.3 | 37.5 | 40.4 | 44.1 | 47.7 |

| Federal | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| Non-Federal2 | 18.1 | 21.5 | 25.3 | 30.1 | 34.2 | 36.9 | 40.3 | 43.8 |

| Individual Policy Premiums | 13.0 | 15.7 | 17.1 | 18.0 | 19.9 | 23.2 | 24.2 | 22.9 |

| Percent Change | ||||||||

| Total Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 15.1 | 16.4 | 14.1 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 14.6 | 17.1 | 14.9 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 6.6 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 13.8 | 16.9 | 14.7 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 7.2 | 6.3 |

| Federal | — | 31.8 | 26.1 | 13.8 | 6.3 | 9.0 | 7.8 | 3.2 |

| Non-Federal | — | 13.1 | 16.5 | 14.8 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 7.1 | 6.5 |

| Private1 | — | 12.2 | 16.6 | 14.0 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 6.0 | 5.6 |

| State and Local | — | 16.8 | 16.0 | 18.1 | 13.6 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 9.8 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | — | 19.2 | 17.8 | 16.0 | 12.5 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 8.2 |

| Federal | — | 20.2 | 17.4 | -3.1 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 2.7 |

| Non-Federal2 | — | 19.1 | 17.8 | 18.6 | 13.7 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 8.7 |

| Individual Policy Premiums | — | 20.6 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 10.7 | 16.5 | 4.3 | -5.1 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||||

| Total Private Health Insurance Premiums | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Employer Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums | 91.5 | 91.1 | 91.6 | 92.3 | 92.1 | 91.6 | 91.8 | 92.7 |

| Employer Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 78.0 | 77.1 | 77.5 | 77.9 | 77.2 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.5 |

| Federal | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 |

| Non-Federal | 74.8 | 73.5 | 73.5 | 74.0 | 73.3 | 73.1 | 73.1 | 73.7 |

| Private1 | 61.0 | 59.5 | 59.6 | 59.5 | 58.2 | 58.0 | 57.4 | 57.3 |

| State and Local | 13.8 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.4 |

| Employee Contribution to Private Health Insurance Premiums | 13.5 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.9 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 15.2 |

| Federal | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Non-Federal2 | 11.9 | 12.3 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 14.0 |

| Individual Policy Premiums | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 7.3 |

| Percent of Premiums Paid by Employer | ||||||||

| Employer-Sponsored Private Health Insurance | 85.3 | 84.7 | 84.6 | 84.5 | 83.8 | 84.0 | 83.8 | 83.6 |

| Federal | 67.0 | 69.0 | 70.5 | 73.8 | 74.7 | 75.1 | 75.2 | 75.3 |

| Non-Federal2 | 86.3 | 85.7 | 85.5 | 85.1 | 84.4 | 84.6 | 84.3 | 84.1 |

Includes employer and employee share of private health insurance premiums for agricultural services.

Employee data are not available separately for private industry and State and local governments.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1987-94.

Private health insurance spending is categorized into three principle payer groups: employers, employees, and individuals. Employers and employees (and retirees) contribute to premium costs associated with employer-sponsored health insurance. Individuals purchase insurance directly or through association groups. One popular form of individually purchased insurance is “medigap” policies, which supplement coverage obtained through the Medicare program.

Employer and Employee Premiums

Of the $313.3 billion spent on premiums in 1994, $290.3 billion was spent by employers and their employees for workplace-based private health insurance premiums. Since 1989, the overall rate of growth in employer-sponsored private health insurance premiums slowed markedly, reaching a low of 6.6 percent in 1994. After years of double-digit increases, the recent slowdown in the rate of premium growth is a very positive trend for business, governments, and workers paying for health insurance, although it is yet unclear how long this trend can be sustained.

Possible factors influencing the recent slowdown in aggregate premium growth include changes in the insurance marketplace, as well as structural and political forces within the overall economy. In recent years, many employers and their employees shifted to managed care plans that offered lower average premiums than traditional indemnity health plans. The switch by employers to lower cost plans helped to slow aggregate premium growth. However, current (1995) health cost indicators (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1991-95) suggest that average premiums for some types of managed care plans (PPO and point-of-service [POS] plans) may be growing faster and may actually exceed the cost of conventional indemnity plans, eliminating the premium cost advantage.6

In addition to market changes, the private industry job mix in the United States is changing. In recent years, employment growth has been concentrated in the service-producing industries, such as retail trade, rather than in goods-producing industries, such as manufacturing (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1996a). Service-producing industries, on average, have lower proportions of workers eligible for employer-sponsored health insurance coverage (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1991-95). As a result, the increasing proportion of employment in service-producing industries lowers the overall growth rate for premium spending per worker.

Other factors, such as the threat of health care reform in 1993, may have had an impact on overall medical inflation and insurance premium costs, but such political influences are harder to quantify. Nevertheless, it appears that employers and the insurance industry are aggressively seeking out and implementing far-reaching cost-containment strategies.

Non-Federal Employer Share

In 1994, non-Federal employers contributed 83.6 percent ($230.8 billion) of the premium cost for their employees' health insurance plans, with the employees paying the remainder. For 6 out of the last 7 years covered by this article, the rate of growth in employer-paid premiums was slower than the growth of premiums paid by their employees. From 1987 to 1994, the share of total health insurance premiums paid by private industry and State and local government employers has gradually eroded, falling a little more than 2 percentage points. Although the decline appears relatively small, at the 1994 level of total premium spending, a 2-percentage-point increase in the employer share would reduce the employee contributions by 14 percent, or $5.5 billion.

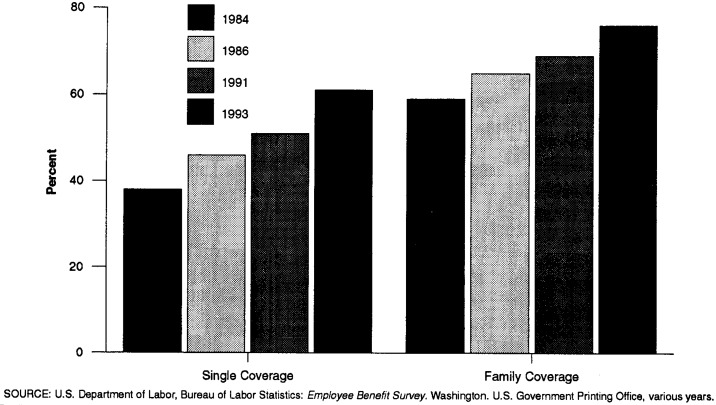

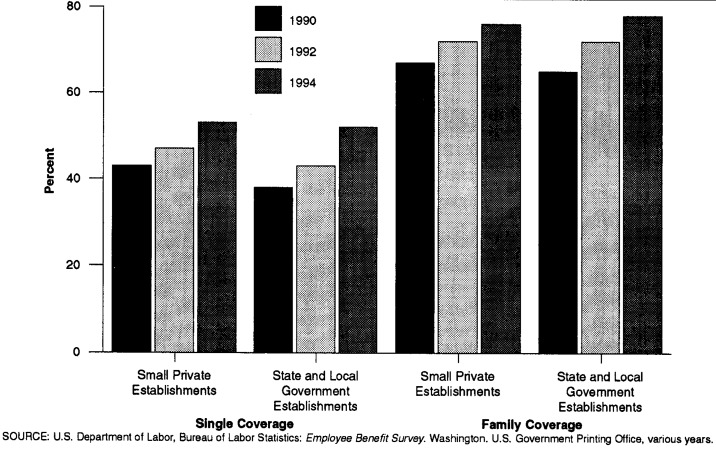

The decline in the employer share of total premiums was partially the result of employer policies to shift more of the financial burden of rising health insurance costs to employees. In today's cost-containment climate, it is increasingly rare for anyone to receive 100-percent employer-financed health insurance. Over the last decade, data collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employee Benefits Survey (EBS) (1995a, 1995b, 1994a, 1994b, 1994c) show a steady increase in the requirement that employees contribute toward their health insurance premium costs (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Percent of Enrollment in Employer-Sponsored Plans Requiring Employee Contribution in Medium and Large Establishments: Selected Calendar Years 1984-93.

Figure 4. Percent of Enrollment in Employer-Sponsored Plans Requiring Employee Contribution in Small Private and Large Establishments: Selected Calendar Years 1984-93.

In addition to requiring more employees to contribute, employers raised the portion of the premium paid by those contributing employees for health insurance. EBS data show that average monthly employee premiums rose sharply in the latter half of the 1980s and then slowed in the early 1990s.7 However, the rate of increase for employee premiums varied widely by economic sector and establishment size. The fastest rates of increase in average premiums were in small establishments with fewer than 100 employees (Table 10). For example, from 1990 to 1994, the average single-coverage premium in small establishments rose 63 percent (from $25.13 to $40.97). By contrast, the average single-coverage premium in State and local government establishments rose just a little more than 18 percent during the same period (from $25.53 to $30.20). Average employee premiums in private establishments with more than 100 workers increased a comparatively moderate 25 percent from 1989 to 1993 (from $25.31 to $31.55). Similar percentage increases occurred for average monthly premiums for family coverage in each type of establishment.

Table 10. Average Employee Premiums: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1989-94.

| Type of Establishment and Plan | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Amount in Dollars | ||||||

| State and Local Government Establishments | ||||||

| Single Plans | — | $25.53 | — | $28.97 | — | $30.20 |

| Family Plans | — | 117.59 | — | 139.23 | — | 149.70 |

| Medium and Large Establishments | ||||||

| Single Plans | $25.31 | — | $26.60 | — | $31.55 | — |

| Family Plans | 72.10 | — | 96.97 | — | 107.42 | — |

| Small Private Establishments | ||||||

| Single Plans | — | 25.13 | — | 36.51 | — | 40.97 |

| Family Plans | — | 109.34 | — | 150.54 | — | 159.63 |

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics: Employee Benefit Survey. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989-95.

In addition to raising employee contribution rates and average premiums, employers have turned to managed care plans to help control their costs. Although such plans offer lower overall premium costs than conventional indemnity plans, the shift has also had an impact on the average employer and employee shares of total health insurance premiums. Survey data show that the percent of total premiums paid by employers is usually lower for HMO, PPO, and POS plans than for conventional indemnity plans, especially for family policies (KPMG Peat Marwick, 1991-95).

In 1994, KPMG reported that employers paid approximately 80 percent of the total premium costs for individual coverage in HMO plans, 82 percent in POS plans, 83 percent in PPO plans, and 88 percent in conventional fee-for-service plans. The differences in employer contribution rates for family coverage were larger, employers contributed a little more than two-thirds of the total premium cost for HMO and PPO plans but more than three-quarters of the cost for conventional fee-for-service plans. The employer contribution rate for family POS plans (73 percent) was the highest for all managed care plans but still 4 percentage points below the indemnity contribution rate (77 percent). Such differences suggest that the effect of rising enrollment in managed care plans would be to reduce the average employer share for all health insurance premiums.

Although these aggregate trends in employee contributions and the migration to managed care were important influences on the employer/employee share, so were certain other factors, including the structural changes in the employment mix within the economy. As noted earlier, private sector job growth over the last decade was concentrated in service-producing industries that have, on average, a lower percentage of workers with health insurance. However, survey data also indicate that when employers in the service-producing industries do offer health benefits, they pay a lower share of their workers' health insurance premiums (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1993). For example, in 1992, the average employer share in goods-producing establishments was 89 percent, while employers in service-producing industries contributed 84 percent (Table 11). Overall, it appears that the continuing shift in the industrial composition of the U.S. economy was an additional influencing factor in the erosion of the average employer share of health insurance premiums over time.

Table 11. Percent of Total Expenditures Paid by Employers and Employees in Private Industry: United States, 1992.

| Industry | Employer | Employee |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Percent | ||

| Goods-Producing Industries | 89 | 11 |

| Construction | 89 | 11 |

| Manufacturing | 89 | 11 |

| Service-Producing Industries | 84 | 16 |

| Wholesale Trade | 86 | 14 |

| Retail Trade | 77 | 23 |

| Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate | 81 | 19 |

| Services | 84 | 16 |

SOURCE: (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1993).

Federal Government Employer Share

In 1994, the Federal Government provided 2.4 million active employees and 1.7 million retirees with employer-sponsored private health insurance (Iadicicco, 1996). Of the $242.7 billion spent by employers in 1994 for private health insurance premiums, the Federal Government contributed $11.9 billion or 3.8 percent of the total costs. Federal employees contributed $3.9 billion of the $47.7 billion paid by all employees for their employer-sponsored health insurance premiums (Table 8).

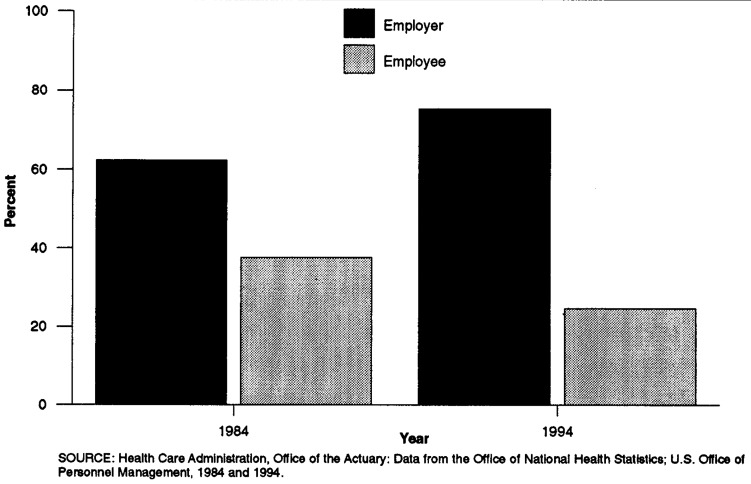

Over the last 10 years, the Federal Government employer share of private health insurance premiums increased substantially, from 62.3 percent in 1984 to 75.3 percent in 1994 (Figure 5), while the non-Federal employers percent contribution decreased slightly from 86.3 percent in 1987 to 84.1 percent in 1994. Although non-Federal employers continue to pay a higher proportion of the total premium cost for their employees than do their Federal counterparts, the gap in contribution rates has narrowed considerably. The explanation for this trend lies within the law that defines the methodology for computing the Federal employer's contribution and in the plan selection preferences of Federal workers.

Figure 5. Employer and Employee Share of Federal Government Sponsored Private Health Insurance Premiums: 1984 and 1994.

Individually Purchased

Individually purchased private health insurance premiums accounted for $22.9 billion of total premiums. These expenditures include premiums for private health insurance policies owned by individuals and Medicare supplemental private health insurance. From 1993 to 1994, the amount paid for individually purchased premiums decreased from $24.2 billion to $22.9 billion. During this time, the Consumer Expenditure Survey showed an increase of approximately 3 percent in premiums paid per policy, while there was a decrease of approximately 7 percent in the number of policies held per household (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1984-94).

Methodology

In this article HSS is disaggregated by the sponsors of health care services—business, households, and governments— rather than by the traditional NHA payer categories, such as private health insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid (Levit et al., 1996). Spending for health care services measured by HSS, a subset of the NHA, covers the cost of all personal health care goods and services, government public health activities, administrative costs of public programs, and the net cost of private health insurance (Lazenby et al., 1992).

Most of the estimates (such as workers' compensation and non-patient revenues) presented in this article come directly from the NHA and are reassigned to separate sponsor categories. Other estimates also come from the NHA, although they must be disaggregated before reassignment. Two NHA estimates are affected by this disaggregation and reassignment: Medicare and private health insurance. Data sources used in Medicare disaggregation include Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund (Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 1995), Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund (Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund, 1995), and unpublished detailed data on Medicare HI tax liability from the Social Security Administration.

Private health insurance estimates are split into Federal and non-Federal (private and State and local government) employer-paid premiums, and household-paid premiums, using data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), HCFA, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, and the BLS. A full description of methods used to produce these estimates has been published in previous articles (Levit and Cowan, 1991; Levit, Freeland, and Waldo, 1989).

This year, for the first time, estimates of employee share of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums and individually purchased health insurance premiums were published. Data on Federal employee premium contributions were obtained from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Data used to produce estimates of non-Federal employee premium costs were obtained from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Bureau of the Census. These sources included the BLS news release entitled Survey of Expenditures for Health Care Plans by Employers and Employees, 1992, and the Consumer Expenditure Survey (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1984-94).

In the analysis of all-employer real compensation costs per worker, we used counts of full- and part-time employees. However, these two groups do not have the same participation rate for health benefits. According to the EBS in 1994, only 7 percent of part-time employees in small establishments participated in employer-sponsored medical care benefit plans, compared with 66 percent of the full-time employees (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994b). Part-time employees in medium and large firms had a 24-percent participation rate in 1993, while full-time employees participated about 82 percent of the time (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994a). Ideally, we would like to look at the part-time and full-time workers' compensation separately, because their access to health care benefits differ, but such data are not available. Therefore, any alteration in the mix of full-time and part-time workers will affect this analysis.

Conclusion

In this article, we review health care expenditures in the United States from the vantage point of the major health care sponsors—business, governments, and households. Overall, health care costs are continuing to rise as a percentage of the country's output (gross domestic product), but the growth in HHS costs has decelerated to a rate not seen in more than 30 years.

Slower cost growth has helped to reduce the spending pressure on business, governments, and households paying for health care services. In the workplace, the migration toward managed care, cost-shifting from employers to employees, and changes in the employment mix have dampened premium growth for employers. At the same time, households have experienced lower rates of growth in both premiums and out-of-pocket health care costs. Slower cost growth, combined with increased profits and income seem to be stabilizing the burden health care imposes on business and households.

By contrast, governments face a different health care spending environment. First, State governments are experiencing increasing health care burdens; that is, revenues are not keeping pace with rising health care costs. State governments have responded to rising Medicaid spending by utilizing waiver programs to enroll more and more Medicaid recipients into managed care health plans. As employers, State governments have also steered more of their own workers into managed care plans while increasing employee premiums. Nevertheless, the burden on State governments continues to rise.

Federal Employer Contributions.

Title 5 of the United States Code, Chapter 89 defines the methodology for computing Federal employers' contributions. This law requires the Office of Personnel Management to determine a maximum government contribution for both self-only and self-and-family enrollments at the beginning of each contract year. OPM calculates the maximum government contribution by using the highest level of benefits offered by six plans. Included in these plans are a service benefit plan, an indemnity plan, the two employee organization plans with the largest number of enrollments, and the two comprehensive medical plans with the largest number of enrollments. The plans used by OPM in 1994 included: High Option Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Aetna,8 Group Employee Health Association, High Option Mailhandlers, Kaiser-North, and Kaiser-South. The maximum government contribution is calculated by taking 60 percent of the straight average of the premiums of the aforementioned plans. In 1994, the Federal Government contributed a biweekly maximum of $66.20 for enrollees choosing the self-only option and a biweekly maximum of $141.42 for self-and-family (Iadicicco, 1996). The biweekly government contribution rate is limited by law to 75 percent of the biweekly premium for any health insurance plan.9

The 1994 Blue Cross and Blue Shield Benefit Plans for both high and standard options are described in Table 12. The breadth of coverage is relatively the same, and both options offer a PPO. Although out-of-pocket expenses are somewhat greater with the standard option, the government pays a greater percentage of the standard option biweekly premium than it does for the high option. In 1994, the total employer and employee monthly premium for the Blue Cross and Blue Shield self-only for high option was $303.81, compared with $181.65 for self-only, standard option. The government paid only 47 percent for the high-option premium, in contrast to 75 percent for self-only, standard option. In 1994, 93 percent of the 1.7 million employees and annuitants selecting a Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan chose the standard option.

The Federal Government also faces an uncertain environment. Although one measure of the Federal Government's health care burden has stabilized since 1992, the Federal share of health care spending continues to rise, and long-term Medicare financing issues have taken center stage.

There are several key questions that remain unanswered regarding future health spending for business, households, and governments. First, as health care plan enrollees complete the transition to managed care, will cost increases remain moderate or will they begin to accelerate? Second, as the industry mix in the United States continues to shift toward the service sector, what will be the long-term impact on the availability of employer-sponsored insurance and the numbers of uninsured persons? And finally, how will the country manage the long-term financing of its public health care programs, including Medicare and Medicaid? The answers to these questions will be pivotal to each payer sector and their future health care liabilities.

Table 3. Percent of Full-Time Workers in Medium and Large Firms Who Participate in Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, by Category of Benefits Covered: United States, Selected Calendar Years 1984-93.

| Selected Covered Benefits | 1984 | 1989 | 1993 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Abuse | 61 | 97 | 98 |

| Drug Abuse | 52 | 96 | 98 |

| Home Health Care | 46 | 75 | 86 |

| Hospice Care | 11 | 42 | 65 |

| Routine Physicals | 8 | 28 | 42 |

| Well-Baby Care | NA | 34 | 48 |

| Immunizations and Inoculation | NA | 28 | 37 |

NOTE: NA Is not applicable.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics: Employee Benefit Survey. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1984-94.

Table 12. Employee Premium Amounts and Medical-Surgical and Mental Health Benefits for the 1994 Blue Cross and Blue Shield Service Benefit Plan.

| Premium or Benefit Type | Plan and Provider Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| High Option | Standard Option | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Non-PPO | PPO | Non-PPO | PPO | |

| Employee Premium | ||||

| Monthly | Dollars | |||

| Self Only | $160.38 | $160.38 | $45.41 | $45.41 |

| Self and Family | 343.24 | 343.24 | 101.25 | 101.25 |

| Biweekly | ||||

| Self Only | 74.02 | 74.02 | 20.96 | 20.96 |

| Self and Family | 158.42 | 158.42 | 46.73 | 46.73 |

| Benefit Type | ||||

| Medical-Surgical Benefit | ||||

| Employee Share | ||||

| Deductibles | ||||

| Calendar Year | 150 | 150 | 200 | 200 |

| Inpatient Hospital | 100 | 0 | 250 | 0 |

| Catastrophic Limit | ||||

| Per Person | 2,200 | 1,500 | 3,250 | 2,500 |

| Per Family | 2,200 | 1,500 | 3,250 | 2,500 |

| Plan Pays | ||||

| Inpatient Hospital | Percent | |||

| Room and Board | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Other | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Inpatient Doctor | ||||

| Surgeon | 80 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| Other | 80 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| Outpatient Hospital | ||||

| Surgeon | 80 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| Other | 80 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| Outpatient Doctor | ||||

| Tests | 80 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| Accidental Injuries | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mental Health Benefit | ||||

| Employee Share | Dollars | |||

| Catastrophic Limit per Person | $4,000 | $4,000 | $8,000 | $8,000 |

| Plan Pays | ||||

| Lifetime Maximum per Person | 75,000 | 75,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

NOTE: PPO is preferred provider organization.

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Retirement and Insurance Service: 1994 Federal Employees Health Benefits Guide, 1994.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared under the general direction of Katharine R. Levit, Deputy Director, Office of National Health Statistics. The authors are grateful to the following colleagues in the Office of the Actuary for their advice and comments: Richard S. Foster, Daniel R. Waldo, and Katharine R. Levit.

Footnotes

The authors are with the Office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of HCFA.

Also includes a a small amount of interest income earned on the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and the Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund.

Small firms and State and local governments showed similar trends.

Business health spending includes all types of business—corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships. However, we do not have a measure of profits for organizations other than corporations.

According to the Consumer Expenditure Survey glossary: The reference person is “the first member mentioned by the respondent when asked to ‘Start with the name of the person or one of the persons who owns or rents the home.’ It is with respect to this person that the relationship of the other consumer unit members is determined” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1995c).

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981 amended the original provisions of the Medicaid program to allow States to restrict freedom of choice for beneficiaries (section 1915(b)). In addition, under the research and demonstration waivers authority (section 1115), States can mandatorily enroll Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care programs. These waivers must be submitted to and approved by HCFA

KMPG Peat Marwick surveys company health plans with the largest enrollment from a random sample of employers with 200 or more workers. Because smaller employers are excluded, these data are not fully representative of the employer-sponsored private health insurance marketplace. Nevertheless, the data provide valuable comparative statistics on health plan costs, design characteristics, and changes over time.

BLS publishes an average monthly employee premium contribution for both individual and family coverage but not the amount contributed by the employer to the premium. Although the number of employees participating in employer sponsored insurance is collected, the number participating in either single or family coverage is not. Therefore, an estimate of aggregate employee premium contributions cannot be tabulated from the EBS. Because the EBS cannot provide aggregate employee premium contribution, it does not directly contribute to the aggregate premium data discussed in this article.

Effective January 1, 1990, Aetna no longer offered an indemnity plan to government workers. For 1990 to the present, the Aetna rate was calculated using the Aetna 1989 premiums adjusted each year by the average percentage increase of the other five plans.

Some plans, such as those covering postal workers, are not limited to the 75-percent government contribution rate.

Reprint Requests: Anna M. Long, Office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration, 7500 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, N-3-02-02, Maryland 21244-1850.

References

- Berreth CA. Workers' Compensations Laws: Significant Changes in 1993. Monthly Labor Review. 1994 Jan; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. 1995 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Washington DC.: Apr 3, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. 1995 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. Washington DC.: Apr 3, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foster Higgins. National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, 1994. New York: Foster Higgins Survey and Research Services; 1994. Report. [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Financing Administration. Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment Report. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995. Office of Managed Care. [Google Scholar]

- Iadicicco, R.: Personal communication. Office of Insurance Programs, Retirement and Insurance Service, Office of Personnel Management. Washington, DC. 1996.

- KPMG Peat Marwick. Health Benefits in 1995. (Also yearly editions for 1991-94) Newark, NJ.: 1991-95. [Google Scholar]

- Kronson ME. Substance Abuse Coverage Provided by Employer Medical Plans. Monthly Labor Review. 1991 Apr; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazenby HC, Levit KR, Waldo DR, et al. National Health Accounts: Lessons From the U.S. Experience. Health Care Financing Review. 1992 Summer;13(4):89–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Lazenby HC, Sivarajan L, et al. National Health Expenditures, 1994. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Spring;17(3):205–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Cowan CA. Business, Households, and Governments: Health Care Costs, 1990. Health Care Financing Review. 1991 Winter;13(2):83–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit KR, Freeland MS, Waldo DR. Health Spending and Ability to Pay: Business, Individuals, and Government. Health Care Financing Review. 1989 Spring;10(3):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Bureau of Census. 1987 Census of Governments: Public Employment: Government Costs for Employee Benefits. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; Mar, 1991. U.S. Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Survey of Current Business. No. 1/2. Vol. 76. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1996. Improved NIPA Estimates for 1959-95. U.S. Department of Commerce. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The BLS Handbook of Methods. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sep, 1992. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. BLS Reports on Employee Benefits in State and Local Governments, 1994. U.S. Department of Labor; Sep 14, 1995a. News Release USDL: 95-368. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. BLS Reports on Employee Benefits in Small Private Industry Establishments, 1994. U.S. Department of Labor; Sep 14, 1995b. News Release USDL: 95-367. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employee Benefits in Medium and Large Establishments, 1993. (Also yearly editions for 1984, 1986, 1989, and 1991) Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 1994a. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employee Benefits in Small Private Establishments, 1992. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; May, 1994b. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employee Benefits in Small Private Establishments, 1990. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sep, 1991. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employee Benefits in State and Local Governments, 1992. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jul, 1994c. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employee Benefits in State and Local Governments, 1990. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; Feb, 1992. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment and Earnings, 1996. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jan, 1996a. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment and Earnings, 1986. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jan, 1986. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment Cost Index— March 1996. U.S. Department of Labor; Washington, DC.: Apr 30, 1996b. News Release USDL 96-160. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Survey of Expenditures for Health Care Plans by Employers and Employees, 1992. U.S. Department of Labor; Washington, DC.: Dec 20, 1993. News Release USDL: 93-560. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unpublished data. U.S. Department of Labor; Washington, DC.: 1984-94. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditure Survey 1992-93. Washington, DC.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995c. U.S. Department of Labor. [Google Scholar]