Abstract

The potent immunoregulatory properties of Interleukin-10 (IL-10) can counteract protective immune responses and thereby promote persistent infections as evidenced by prior studies of cryptococcal lung infection in IL-10 deficient mice. To further investigate how IL-10 impairs fungal clearance the current study utilized an established murine model of C57BL/6 mice infected with C. neoformans strain 52D. Our results demonstrate that fungal persistence is associated with an early and sustained expression of IL-10 by lung leukocytes. To examine whether IL-10-mediated immune modulation occurs during the early or late phase of infection, assessments of fungal burden and immunophenotyping were performed on mice treated with anti-IL-10 receptor blocking antibody at 3, 6, and 9 days post-infection (dpi) (early phase) or at 15, 18, and 21 dpi (late phase). We found that both early and late IL-10 blockade significantly improved fungal clearance within the lung when assessed 35 dpi compared to isotype control treatment. Immunophenotyping identified that IL-10 blockade enhanced several critical effector mechanisms including: a) increased accumulation of CD4+ T cells and B cells, but not CD8+ T cells, b) specific increases in the total numbers of Th1 and Th17 cells, and c) increased accumulation and activation of CD11b+ dendritic cells and exudate macrophages. Importantly, IL-10 blockade effectively abrogated dissemination of C. neoformans to the brain. Collectively, this study identifies early and late cellular and molecular mechanisms through which IL-10 impairs fungal clearance and highlights the therapeutic potential of IL-10 blockade in the treatment of fungal lung infections.

Keywords: Interleukin-10, dendritic cells, macrophages, lung, rodent, Cryptococcus

Introduction

C. neoformans is an encapsulated fungus acquired by the inhalational route. Depending on the virulence of the organism and the host’s immune status, lung infection results in one of three primary outcomes: clearance, persistence, or progressive infection (1). Failed clearance may result in lethal dissemination to the central nervous system (CNS)(1). Infections with C. neoformans are the leading cause of fatal mycosis in HIV-positive individuals (1 million new cases and 680,000 deaths per year (2)), and the second most common fungal infection in patients with organ transplants (1). In addition to the exceedingly high mortality rate (up to 70%) observed in infected HIV+ patients treated with anti-fungal therapy (2), up to 15% of these patients relapse indicating that the infection can persist despite therapy and the development of partial immunity (3). Thus, novel approaches that can augment traditional anti-fungal therapies are needed. Cytokine networks, critically important in the pathogenesis of this disease (4, 5), represent potential new targets for immune-based therapies.

Interleukin-10, a potent regulatory cytokine, exerts pleotropic effects on numerous subsets of immune cells (6, 7). The effects of IL-10 are mediated through the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R), a heterodimer consisting of an α and β subunit (7, 8). These effects may be prominent during the innate (afferent) and (or) adaptive (efferent) phase of immune responses. Amongst cells of the innate immune system, macrophages in particular are susceptible to the anti-inflammatory effects caused by IL-10 (9). Within adaptive immunity, IL-10 regulates many T and B cell responses, although many of the effects are indirect, being mediated via a direct effect of IL-10 on antigen presenting cells including dendritic cells (6, 7).

Limited evidence implicates IL-10 in the pathogenesis of progressive or persistent cryptococcal infection in humans. In both HIV and transplant patients infected with C. neoformans, high IL-10 levels in the peripheral blood correlated with fungemia and disseminated disease (10, 11). In vitro studies have demonstrated that human monocytes and DC exposed to cryptococcal antigen express high amounts of IL-10 and less MHC Class II molecules (12–14). The addition of exogenous IL-10 to co-cultures of cryptococcal-laden human monocytes and T cells decreased T cell proliferation and IL-2 production (15).

Murine studies have extended these clinical observations and yielded additional important insights into the role of IL-10 in the pathogenesis of cryptococcal lung infection. Most notably, Hernandez et al. demonstrated that IL-10 deficient mice (C57BL/6 genetic background) were more resistant than wild-type mice to lung infection with a moderately virulent and encapsulated strain of C. neoformans (strain 52D; American Type Culture Collection 24067) (16). Although this study showed that IL-10 altered the overall balance between T1 and T2 adaptive immune responses (away from T1), numerous important questions remained unanswered including: Were the effects of IL-10 mediated early or late during infection? Did IL-10 alter Th17 cell development (as we have recently shown an important protective role for IL-17 in this model (17))? Was there an effect of IL-10 on myeloid cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages? Lastly, given the aforementioned limited efficacy of current anti-cryptococcal therapy in humans, could targeting of the IL-10 signaling axis be achieved in wild type mice in a manner that could one day be translated into clinical trials?

In the current study, we show that persistent cryptococcal infection of C57BL/6 mice is associated with sustained expression of IL-10. By blocking IL-10 signaling (using antibodies directed against the IL-10 receptor) during either the early or late phase of cryptococcal lung infection we demonstrate that both approaches enhance fungal clearance, likely through mechanisms involving increases in Th1 and Th17 cells and enhanced accumulation and activation of lung dendritic cells and macrophages. Moreover, IL-10 blockade limited CNS dissemination. These novel findings identify the IL-10 signaling pathway as a potential therapeutic target in patients with fungal lung infections.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Wild-type (C57BL/6J) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory Inc. (Wilmington, MA) and housed under pathogen-specific-free conditions in the Animal Care Facility at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Health System. All studies were conducted according to a protocol approved by the VA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were 8–12 weeks of age at the time of infection. Within this age range, we observed no age-related differences in the responses of these mice to C. neoformans infection.

C. neoformans

C. neoformans strain 52D was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (24067; Manassas, VA); this strain displayed smooth colony morphology when grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar. For intratracheal (i.t.) inoculation, C. neoformans was grown to a late logarithmic phase (48–72 h) at 37°C in Sabouraud dextrose broth (1% neopeptone and 2% dextrose: DIFCO, Detroit, MI) on a shaker. Cultured yeasts were then washed in non-pyrogenic saline, counted in the presence of Trypan Blue using a hemocytometer, and diluted to 3.3 × 105 CFU/ml in sterile non-pyrogenic saline immediately prior to i.t. inoculation.

Surgical intratracheal inoculation

Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (6.8 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA). Through a small midline neck incision, the strap muscles were divided and retracted laterally to expose the trachea. Intratracheal inoculation was performed under direct vision using a 30 gauge needle attached to a 1 ml syringe mounted on a repetitive pipette (stepper, Tridak, Brookfield, CT). An inoculum of 104 CFU (30 µL) was injected into the trachea. Skin was closed using cyanoacrylate adhesive.

Intravenous inoculation

An inoculum of 105 CFU suspended in 100 µL PBS was injected into the lateral tail vein using a 30 gauge needle attached to a 1 ml syringe.

Tissue Collection

Lungs were perfused in situ via the right heart using 5 ml PBS containing 0.5 mM EDTA until pulmonary vessels were grossly clear. Lungs were then excised, minced, enzymatically digested, and a single cell suspension of lung leukocytes obtained as previously described (18). After erythrocyte lysis, cells were washed, filtered over 70 µm mesh, and resuspended in complete medium. Dead cells were removed by centrifugation over a percoll gradient. Total numbers of viable lung leukocytes were assessed in the presence of Trypan Blue using a hemocytometer. All cell preparations were washed twice in sterile PBS before use for culture or antibody staining. Brain and (in select experiments) spleen tissues were homogenized in 2 ml of sterile water and used for CFU assays. In select experiments, blood obtained from the inferior vena cava was placed in heparinized tubes and subsequently used in CFU assays.

Measurement of cytokine production

Lung leukocytes obtained from uninfected mice (Day 0) and mice infected for 7, 14, and 28 days were cultured at 5×106 cells/ml in 24 well plates in 2 ml of complete RPMI1640 media at 37° and 5% CO2 for 24 hours without additional stimulation. At the end of culture, supernatants were harvested and IL-10 concentration was assessed in triplicates by Luminex assay (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX) per the manufacturer’s instructions. In selected experiments, supernatants from lung leukocyte cultures obtained in a similar manner were quantified for IFNγ and IL-4 by ELISA using DuoSet kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer’s specifications. All plates were read on a Versamax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Histology

Lungs were fixed by inflation with 1 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin, excised en bloc, and immersed in neutral buffered formalin. After paraffin embedding, 5-mm sections were cut and stained using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Sections were analyzed with light microscopy and microphotographs taken using Digital Microphotography system DFX1200 with ACT-1 software (Nikon Co, Tokyo, Japan).

IL-10 Receptor Blocking Antibody

Ultralow endotoxin, azide-free purified blocking antibody against the murine IL-10 receptor (IL-10 R; CD210) (α-IL-10R) – clone 1B1.3a – or Rat IgG1,κ isotype control antibody – clone RTK2071 (Biolegend, San Diego, California) was administered i.p. three times at a dose of 0.5 mg of antibody in 200µl of sterile PBS (cumulative dose of 1.5 mg per mouse) to mice during the early or late phase of pulmonary C. neoformans infection. Early treatment consisted of i.p. injections on at 3, 6, and 9 days post infection (dpi); late treatment consisted of i.p. injections at 15, 18, and 21 dpi.

CFU assay

To quantify fungal CFUs, aliquots (10 µl) of lung digests, brain and spleen homogenates, and blood samples were plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates in duplicates and in serial 10-fold dilutions and incubated at room temperature. Colonies were counted 2–3 days later and the number of CFU per organ was calculated. All recovered C. neoformans colonies retained their smooth morphology.

Monoclonal Abs

The following mAbs purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA) were used: N418 (anti-murine CD11c, hamster IgG1); 2.4G2 (“Fc block”) (anti-murine CD16/CD32, rat IgG2b); 30-F11 (anti-murine CD45, rat IgG2b); 16-10A1 (anti-murine CD80, hamster IgG2); GL1 (anti-murine CD86, rat IgG2a); AF6-120.1 (“MHC Class II”) (anti-murine I-Ab, mouse IgG2a); 145-2C11 (anti-murine CD3ɛ, hamster IgG1, k); 6D5 (anti-murine CD19, rat IgG2a), and BM8 (anti-murine F4/80, rat IgG2a). The mAb, AL-21 (anti-murine Ly-6C, Rat IgM); and M1/70 (anti-murine CD11b, rat IgG2b) were purchased from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal Abs were primarily conjugated with FITC, PE, PerCP-Cy5.5, allophycocyanin (APC), APC-Cy7, or Pacific blue. Isotype-matched control mAbs (BioLegend) were tested simultaneously in all experiments.

Cell staining and flow cytometric analysis

Cell staining, including blockade of Fc receptors, and sample analysis by flow cytometry were performed as described previously (18). A minimum of 100,000 events were acquired per sample on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD PharMingen) using Cell-Quest software (BD Pharmingen). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA). Lung leukocyte subsets were identified using established gating strategies (17–20): Briefly, initial gates eliminated debris and identified CD45+ leukocytes. Within this CD45+ population, we identified CD4+ T cells (CD45+ FSClow SSClow CD4+ CD8−); CD8+ T cells (CD45+ FSClow SSClow CD4− CD8+); and B cells (CD45+ FSClow SSClow CD19+). To identify lung myeloid cells, lymphocytes were first eliminated (by gating out CD3+ and CD19+ cells). Thereafter additional gating identified the following myeloid subsets: Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (FSClow/moderate Ly-6Ghigh); Eosinophils (FSCmoderate SSCmoderate/high Ly-6Gmoderate); Ly-6Chigh monocytes (CD45+ FSClow Ly-6G− CD11c− F4/80+ CD11b+ Ly-6Chigh); CD11b+ DC (CD45+ FSCmoderate Ly-6G− non-autofluorescent CD11c+ CD11b+); exudate macrophages (FSCmoderate/high Ly-6G− autofluorescent CD11c+ CD11b+); and alveolar macrophages (FSCmoderate/high Ly-6G− autofluorescent CD11c+ CD11b−). Myeloid cell activation was assessed by measuring cell surface expression of MHCII (I-Ab), CD80, and CD86 relative to an isotype-matched control antibody.

For intracellular cytokine staining, 2×106 lung leukocytes/ml were stimulated in vitro for six hours with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1µg/ml) in the presence of monensin (1µl/ml) (17). After stimulation, cells were washed and stained for CD4 to identify CD4+ T cells. Subsequently, cells were washed and stained for intracellular IFN-γ and IL-17A using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen).

To ensure consistency in data analysis, gate positions were held constant for all samples. To calculate the total number of cells in each population of interest in each sample, the corresponding percentage was multiplied by the total number of CD45+ cells in that sample. The latter value was calculated for each sample as the product of the percentage of CD45+ cells and the original hemocytometer count of total cells identified within that sample.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Continuous ratio scale data were evaluated by unpaired Student t test (for comparison between two samples) or by ANOVA (for multiple comparisons) with post hoc analysis by two-tailed Dunnett test, which compares treatment groups to a specific control group (21). Statistical calculations were performed on a Dell 270 computer using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA). Statistical difference was accepted at p < 0.05.

Results

Persistent lung infection with C. neoformans strain 52D in C57BL/6 mice is associated with sustained expression of IL-10

The effectiveness of host defenses in murine models of cryptococcal lung infection is related to the strain of mice studied and the virulence of the infecting organism. Our results demonstrated that infection of C57BL/6 mice with a moderately virulent encapsulated strain of C. neoformans, strain 52D (American Type Culture Collection 24067), resulted in a rapid and sustained increase in lung CFU by 7 days post-infection (dpi) which remained elevated at least to 35 dpi (Figure 1A) consistent with prior studies using this model system (16, 22, 23). Histologic evaluation of lung sections demonstrated that at 7 and 14 dpi, many C. neoformans were located extracellularly within alveolar spaces (data not shown and Figure 1B middle panel, respectively). In contrast, at later time-points (35 dpi; Figure 1B; lower panel) the majority of viable C. neoformans were contained within granulomatous leukocyte infiltrates, many in intracellular forms within macrophages. Thus, these results demonstrate that intratracheal inoculation of C57BL/6 mice with C. neoformans strain 52D results in persistent infection characterized by the localization of viable Cryptococci within lung macrophages.

Figure 1.

Persistent infection of C57BL6/J mice with C. neoformans strain 52D is associated with early and sustained IL-10 expression. (A, B) C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. At days 0 (uninfected) and the indicated days post infection (dpi) lungs were harvested for analysis. (A) Lung CFU analysis. (B) Representative lung sections from uninfected and infected mice (at 14 and 35 dpi; H&E stain, 400X magnification). At day 14 dpi, note the presence of numerous extracellular yeast within alveolar spaces (see inset, black closed arrows). At 35 dpi, note that most yeast are located intracellularly (see inset, black open arrows) within large macrophages amidst scattered foci of small mononuclear cells displaying lymphocyte morphology. (C) IL-10 production by lung leukocytes harvested at the designated time points post infection (as described in Materials and Methods). (A,C) Data represent mean ± SEM of 5–21 mice assayed individually per time point in two separate experiments; *, p<0.05 ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis vs. Day 0 (uninfected).

Prior studies by our research group and others have demonstrated that mice genetically deficient in IL-10 (C57BL/6 genetic background) are more resistant to cryptococcal lung infection (16, 24–26). These studies provided important evidence that IL-10 critically modulates host defenses against this organism; however, the kinetics of IL-10 production in the lungs of wild type C57BL/6 mice infected with strain 52D was not investigated. To address this point, we measured IL-10 production by lung leukocytes obtained from C57BL/6 mice at 0 (uninfected), 7, 14, and 28 dpi. IL-10 production by pulmonary leukocytes was significantly increased as early as 7 dpi and remained elevated relative to uninfected mice throughout 14 and 28 dpi (Figure 1C). Thus, early and sustained production of IL-10 was strongly associated with persistent cryptococcal lung infection.

Blocking either early or late IL-10 signaling improves fungal clearance in mice with cryptococcal lung infection

Our results demonstrated that IL-10 expression was elevated throughout lung infection. This finding suggested that IL-10 might be modulating both the early (primarily afferent and innate) phase of the infection (approximately 0–14 dpi) and the late (primarily efferent and adaptive) phase when infection becomes established (approximately 14–24 dpi) (17, 22, 23, 27–29). To assess the temporal impact of IL-10 production on disease pathogenesis in this model, we sought to transiently block IL-10 signaling in each of these two phases. Due to its demonstrated efficacy in other model systems (30–32), we chose to block IL-10 signaling by treating mice (by i.p. injection) with anti-IL-10 receptor antibody (αIL-10R Ab). Treatment was administered to infected mice at 3, 6, and 9 dpi (early treatment) or at 15, 18, and 21 dpi (late treatment) (Figure 2A). Additional cohorts of mice treated with isotype control Ab during either the early or late phase of infection served as controls. All cohorts of mice were euthanized at 35 dpi as this advanced time-point seemed the most appropriate for determining whether IL-10 signaling blockade would yield lasting effects on fungal clearance and the immunophenotype of the host response. Comparative analyses were performed between mice receiving αIL-10R Ab versus isotype control during the same phase of infection.

Figure 2.

Early or late IL-10R blockade improves lung fungal clearance. (A) Experimental strategy to block IL-10 signaling. Cohorts of mice infected by the intratracheal route received isotype control Ab (open arrowheads) or anti-IL-10 receptor Ab (black arrowheads) (0.5 mg/200 µl PBS i.p.) during either the early (3, 6 and 9 dpi) or late (15, 18 and 21 dpi) phase of cryptococcal lung infection. At 35 dpi, lungs were harvested from all four cohorts for analysis. (B) Lung fungal burden, quantified by CFU assay, in mice treated with either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 9–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually in two separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test comparing treatments at the same time points.

Early treatment with αIL-10R Ab significantly reduced pulmonary fungal CFU at 35 dpi (Figure 2B, left bars). This finding demonstrated that early IL-10 blockade yielded lasting effects on fungal clearance. Late treatment with αIL-10R Ab significantly reduced pulmonary fungal CFU as well (Figure 2B, right bars), demonstrating that late treatment with αIL-10R Ab could enhance fungal clearance even once lung infection was already established. Note that differences in the elapsed time between IL-10 blockade and the timepoint selected for CFU analysis limits direct comparison between the early and late treatment groups.

We next sought to evaluate whether IL-10 blockade had a more immediate impact on fungal clearance. To this end, mice receiving either early or late treatment with anti-IL-10R antibody (or isotype control antibody) were assessed for lung fungal burden by CFU assay 72 hours following their last dose of antibody treatment (at 12 dpi for early treatment, 24 dpi for late treatment; Figure S1A). Early treatment resulted in a non-significant decline in pulmonary fungal CFU (Figure S1B; left bars), whereas late treatment resulted in a statistically significant, albeit small, reduction in fungal clearance (Figure S1B; right bars). Collectively, these results demonstrated that transient IL-10 blockade during either the early or late phase of infection improved clearance of cryptococcal lung infection. Reductions in lung fungal burden were most consistently observed when assessed at 35 dpi, more than 10 days post treatment with αIL-10R Ab.

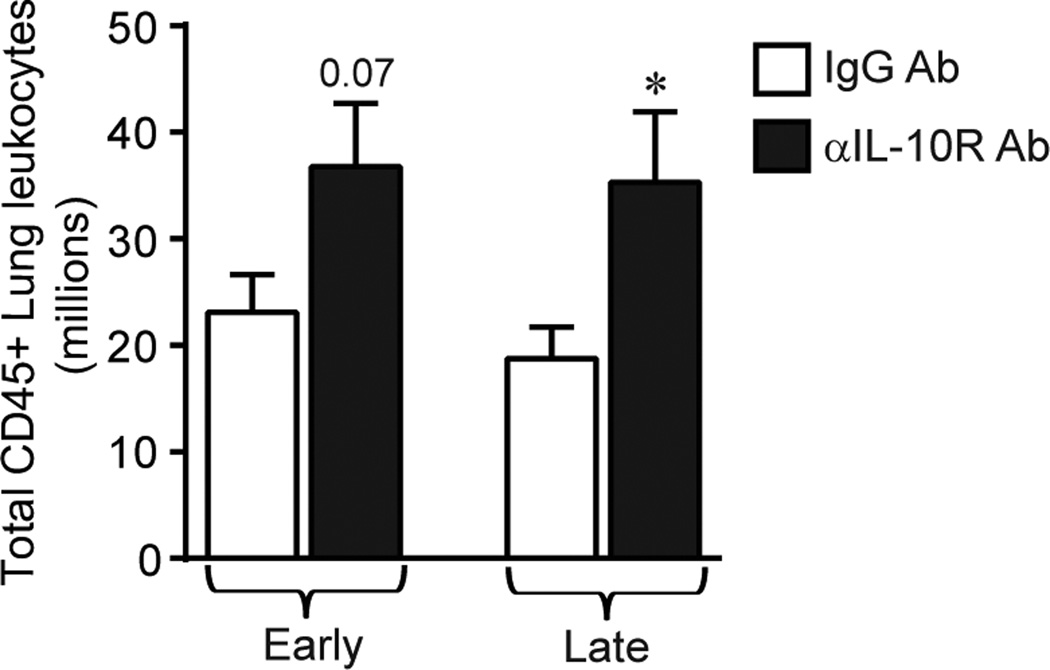

Transient IL-10 blockade increases lung leukocyte accumulation in mice with cryptococcal lung infection

To investigate the mechanism(s) whereby IL-10 blockade enhanced fungal clearance we determined whether treatment with αIL-10R Ab altered the accumulation of lung leukocytes. Using specific antibody-mediated cell staining and flow cytometric analysis we enumerated the total number of lung leukocytes (identified by expression of CD45) in each cohort of antibody-treated infected mice at 35 dpi. Early treatment with αIL-10R Ab resulted in a non-significant trend towards increased lung leukocyte accumulation (Figure 3, left bars). Late treatment with αIL-10R Ab significantly increased lung leukocyte accumulation (Figure 3, right bars).

Figure 3.

Effect of IL-10 blockade on total lung leukocytes during cryptococcal lung infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. Total lung leukocytes (identified at 35 dpi by CD45+ staining using flow cytometric analysis) in mice receiving either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 9–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually in two separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test for comparisons between mice receiving either isotype control Ab or anti IL-10R Ab at the same time point.

In our study, no mice receiving either anti-IL-10R or isotype control Ab died or appeared subjectively ill by 35 dpi consistent with other studies utilizing this model of persistent infection with a moderately virulent strain of C. neoformans ((16, 33). However, in light of this observed increase in lung inflammation in mice subjected to IL-10 blockade, we monitored mice for weight loss as an objective measurement of morbidity. Mice were weighed every two to three days up to 72 hours following the last dose of antibody administration (refer to Figure S1A). No significant differences in weight were observed in mice receiving early treatment with anti-IL-10R antibody (mean weight of 19.4 ± 0.7 grams for isotype-control treated mice versus 19.6 ± 0.6 grams for anti-IL-10R treated mice at 12 dpi), whereas a reduction in weight was observed in mice receiving late treatment with anti-IL-10R antibody (mean weight of 21.4 ± 0.8 grams for isotype-control treated mice versus 17.0 ± 1.1 grams for anti-IL-10R treated mice at 24 dpi). Whether this weight loss persists in mice receiving late IL-10 blockade warrants follow-up in future studies.

Transient IL-10 blockade increases the numbers of Th1 and Th17 cells in mice with cryptococcal lung infection

Clearance of cryptococcal lung infection requires adaptive immunity (34, 35). Thus, we next investigated whether early or late αIL-10R Ab treatment altered the accumulation of lymphocytes in infected lungs. Data obtained using specific cell staining demonstrated that early and late IL-10 blockade increased the total numbers of CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A), but did not affect the accumulation of CD8+ T cells (Figure 4B). Late (but not early) IL-10 blockade increased the total numbers of B cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Early or late IL-10 blockade increases lung Th1 and Th17 cells during cryptococcal lung infection. (A–D) C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. Total numbers of (A) CD4+ T cells; (B) CD8+ T cells; and (C) B cells (identified at 35 dpi by flow cytometric analysis using the gating strategy described in Materials and Methods) in the lungs of mice receiving either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. (D) The percentages (left panels) and total number (right panels) of CD4+ T cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ (top panels) or IL-17A (bottom panels) was evaluated in mice treated with either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 9–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually per time point in two separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test for comparisons between mice treated with isotype control Ab treated versus anti IL-10R Ab at the same time point.

Prior studies have shown that Th1 cells accumulate in C57BL/6 mice persistently infected with C. neoformans strain 52D and that IFNγ expression and signaling is critical to preventing progressive lung infection (22, 27, 28). More recently, we have shown the importance of Th17 cells for cryptococcal clearance in this model (33). Therefore, we next determined whether either early or late IL-10 blockade altered the frequency and total number of Th1 cells (identified as CD4+ T cells positive for intracellular IFNγ staining) or Th17 cells (identified as CD4+ T cells positive for intracellular IL-17A staining). Early and late IL-10 blockade did not increase the frequency of Th1 cells but did increase their total numbers (Figure 4D; upper panels). Early and late IL-10 blockade increased both the frequency and total numbers of Th17 cells (Figure 4D; lower panels). Thus, transient early and late IL-10 blockade improved the accumulation of protective Th1 and Th17 cell populations in the lungs of infected mice.

To determine whether the total number of IFNγ+CD4+ T cells in infected lungs correlated with the level of IFNγ secretion by lung leukocytes, we measured the concentration of IFNγ in the supernatants of lung leukocyte cultures obtained at 35 dpi using ELISA. We found a non-significant trend towards increased IFNγ secretion in mice receiving early anti-IL-10R Ab treatment (Figure S2A, left bars) and a significant increase in IFNγ release in mice receiving late IL-10 blockade (Figure S2A, right bars). IL-17 protein secretion by lung leukocytes was not assessed in the current study, however, using the same animal model, we have recently shown a direct correlation between the incidence and the total number of IL-17+CD4+ T cells and the level of IL-17 transcript expression and protein release (33). To determine whether transient IL-10 blockade affected Th2 responses, we also measured the concentration of IL-4 in the supernatants described above. No significant differences in the levels of IL-4 secretion were detected (Figure S2B).

Transient IL-10 blockade increases the activation of lung dendritic cells and macrophages in mice with cryptococcal lung infection

The improvement in fungal clearance and enhancement in Th1/Th17 responses we observed with IL-10 signaling blockade suggested a beneficial effect on myeloid effector cells. To investigate this, we used established gating strategies (17–20) for analysis of flow cytometric data to assess the effect of αIL-10R Ab treatment on the accumulation of specific lung myeloid cell subsets at 35 dpi (Figure 5). Within granulocyte populations, early αIL-10R Ab treatment did not alter the number of neutrophils or eosinophils (Figure 5A and B, left bars). Late αIL-10R Ab treatment resulted in a non-significant trend towards increased accumulation of neutrophils (Figure 5A, right bars) perhaps reflecting the increase in Th17 cells. No difference in lung eosinophils was observed (Figure 5B, right bars). Prior studies have demonstrated an important role for recruited peripheral blood-derived Ly-6Chigh monocytes in mice that clear cryptococcal lung infection, as these cells can further differentiate into CD11b+ dendritic cells (DC) and exudate macrophages (ExM) (19, 20). In the current study, early αIL-10R Ab treatment did not alter the number of Ly-6Chigh monocytes or CD11b+ DC but did increase the numbers of ExM (Figure 5C, D, and E, left bars). Late αIL-10R Ab treatment did not alter numbers of Ly-6Chigh monocytes but increased both CD11b+ DC and ExM (Figures 5C, D, and E, right bars). Neither treatment impacted the numbers of resident alveolar macrophages (AM; Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Early or late blockade increases lung exudate macrophages during cryptococcal lung infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. Specific myeloid cell subsets including (A) Polymorphonuclear neutrophils; (B) eosinophils; (C) Ly-6Chigh monocytes; (D) CD11b+ DC; (E) exudate macrophages; and (F) alveolar macrophages (identified at 35 dpi by flow cytometric analysis using the gating strategy described in Materials and Methods) in the lungs of mice receiving either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 9–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually per time point in two separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test for comparisons between mice receiving either isotype control Ab or anti IL-10R Ab at the same time point.

We next sought to determine whether early or late treatment with αIL-10R Ab increased expression of activation markers including MHC Class II, CD80, and CD86 by lung DC and macrophages populations, as our prior studies demonstrated a strong association between the expression of these markers and improved clearance of C. neoformans from the lung (19, 20, 36, 37) (Figure 6). Early treatment was associated with a trend towards increased expression of CD80 on CD11b+ DC (Figure 6A, B). By contrast, late IL-10 blockade was associated with significantly increased expression of I-Ab (MHC Class II) by ExM, of CD80 by CD11b+ DC and ExM, and of CD86 by AM (Figure 6A, B). Collectively these findings demonstrated that transient blockade of IL-10 signaling increases the accumulation and activation profile of lung DC and macrophages.

Figure 6.

Late IL-10 blockade increases lung DC and macrophage activation during cryptococcal lung infection. (A, B) C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. (A) Representative histograms displaying isotype control staining (shaded gray histogram), or specific cell surface staining for I-Ab, CD80, and CD86 on CD11b+ DC, exudate macrophages, and alveolar macrophages identified at 35 dpi in the lungs of mice receiving isotype control Ab (dashed line), or anti-IL-10R Ab (solid line) at the early time points (left panels) or late time points (right panels). (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of the indicated markers on each specified subset obtained from mice receiving either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 9–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually per time point in two separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test for comparisons between mice treated with isotype control Ab treated versus anti IL-10R Ab at the same time point.

Late IL-10 blockade reduces CNS dissemination in mice with cryptococcal lung infection

Our data demonstrated that transient IL-10 blockade enhanced protective immune responses within the lungs. Yet the lethality of cryptococcal infections in mice and humans is determined primarily by whether or not the organism disseminates to the CNS. Our final objective was to explore whether early or late IL-10 blockade altered dissemination of C. neoformans from the lung to the brains of infected mice. To this end, cohorts of treated mice were assessed for fungal burden in the brain (by CFU assay) either 72 hours following the last dose of antibody administration (refer to the treatment strategy depicted in Figure S2A) or at 35 dpi (refer to the treatment strategy depicted in Figure 2A). At 72 hours post early treatment (12 dpi), 4 of 5 mice treated with isotype control Ab had fungal growth in brain tissue, whereas no mice (0 of 5) receiving early treatment with αIL-10R Ab had evidence of fungal growth in the brain (Figure 7A, left bars). At 72 hours post late treatment (24 dpi), fungal growth in the brain was noted in 4 of 5 mice treated with isotype control Ab and 2 of 5 mice treated with αIL-10R Ab (Figure 7A, right bars).

Figure 7.

IL-10 blockade reduces fungal burden within the central nervous system. (A and B) C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intratracheal route with C. neoformans strain 52D. Brain fungal burden was quantified by CFU assays in mice receiving either isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R blocking Ab (black bars) during the early phase (left bars) or late phase (right bars) of infection. Brain fungal burden was quantified at (A) 72 hours following the last dose of Ab (12 dpi for mice receiving early treatment; 24 dpi for mice receiving late treatment) or (B) at 35 dpi. Numeric data above the bars indicate the number of mice with any detectable fungal growth in brain tissue. Data represent mean ± SEM of 4–10 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually per time point in 1–2 separate experiments; * p < 0.05 by unpaired Student t test for comparisons between mice treated with isotype control Ab treated versus anti IL-10R Ab at the same time points. (C) C57BL/6 mice were infected by the intravenous route with C. neoformans strain 52D 24 hours after receiving a single dose of antibody treatment. Fungal burden in the brain, lung and spleen was quantified using CFU assays 48 hours after infection in mice receiving isotype control Ab (white bars) or anti-IL-10R Ab (black bars). Data represent mean ± SEM of 6 mice per experimental cohort assayed individually.

At 35 dpi, 3 of 4 mice receiving early treatment with isotype control Ab and 4 of 5 mice treated with αIL-10R Ab had fungal growth in brain tissue (Figure 7B, left bars). In contrast, late IL-10 blockade significantly decreased the burden of C. neoformans within the CNS, as 9 of 10 mice receiving isotype control Ab had evidence of fungal growth in brain tissue whereas only 1 of 10 mice treated with aIL-10R Ab showed any fungal growth in the brain (Figure 7B, right bars). Collectively, these results show that both early and late IL-10 blockade favorably reduced fungal growth in the brain in mice with primary cryptococcal lung infection.

Whereas the favorable reductions in brain fungal burden in mice treated with αIL-10R Ab could reflect diminished dissemination from the lung due to the reduced pulmonary fungal burden observed in these mice, we considered the possibility that IL-10 blockade might affect the blood brain barrier or the immediate innate immune defenses within the CNS. To address this, cohorts of C57BL/6 mice were infected with C. neoformans by the intravenous route 24 hours after receiving one dose of either isotype control Ab or αIL-10R Ab. CFU in the brain, lung, spleen, and blood were assessed 48 hours post infection. Results demonstrated no difference in fungal growth between treatment groups in the brain, lung and spleen (Figure 7C). No fungal growth was observed in the blood in either group (data not shown). These findings suggest that IL-10 blockade did not immediately alter the blood brain barrier or innate CNS immune defenses.

Discussion

This study emphasizes that the microenvironment within persistently-infected tissues is not static but rather results from an ongoing and dynamic balance between effector and regulatory mechanisms. Using a murine model of cryptococcal lung infection, we show that sustained elevations in IL-10 production plays a critical role in maintaining persistent infection not only during the early, developing phase but even when the infection has been established. Specifically, using treatment of mice with αIL-10R Ab, we show that temporary blockade of IL-10 signaling during either the early or late phase of infection improved fungal clearance in the lung. Both early and late treatments enhanced generation of protective Th1 and Th17 responses and increased accumulation and activation of lung DC and exudate macrophages. Notably, treatment with αIL-10R Ab markedly reduced fungal dissemination to the CNS. Collectively, this study significantly advances our understanding of how, and when, IL-10 modulates immune microenvironments to promote cryptococcal persistence. Importantly, our findings suggest that IL-10 blockade may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for treating acute or established fungal lung infections.

Treatment of lung infections caused by invasive fungi (Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Coccidioides immitis) requires lengthy, sometimes lifelong, courses of antibiotics which have limited efficacy, are toxic, and expensive (1, 38). Persistent fungal infections result in parenchymal lung damage (39–43) and may progress once patients become further immunocompromised due to worsening of HIV/AIDS or immunosuppressive therapies (44). These realities motivate studies seeking to better understand the pathogenesis of persistent fungal lung infections with the hope that new treatments might be developed. In this study, we investigated the central role of IL-10 in fungal lung disease. Several features of our experimental design enhance the significance of our findings. First, infection was studied in the lung, the primary site through which humans acquire the organism (1). Second, the murine model used is well-characterized (4, 16, 23, 28, 29, 45–48) which enabled studies evaluating the effects of IL-10 blockade on effector mechanisms known to be associated with fungal clearance. Third, we transiently blocked IL-10 during either the early or late phase of infection which provided novel insights into the temporal significance of IL-10 production. This aspect was not investigated in prior studies using mice genetically-deficient in IL-10 (16, 24–26). Moreover, this study indicates for the first time that transient IL-10 blockade using monoclonal antibodies has translational potential for treating persistent Cryptococcal lung infections in humans. Fourth, we studied fungal dissemination to the CNS, an important surrogate of potentially lethal infection in both mice and humans (1).

Our data show that IL-10 production is increased in lung leukocytes as early as 7 dpi, at the time when afferent innate host responses are developing. Thus, it was tempting to speculate that IL-10 mediated suppression of early innate immune responses might account for the initial rapid intrapulmonary growth of C. neoformans consistently observed up to 14 dpi in C57BL/6 mice infected with strain 52D (5, 28, 49). However, a prior study by Hernandez et al showed no impairment in early fungal clearance in transgenic IL-10 deficient mice; only at later time points were improvement in fungal clearance observed (16). Taken together, these two findings motivated our strategy to block IL-10 during the early phase of infection.

Our results show that early blockade of IL-10 signaling variably reduced fungal clearance when assessed 72 hours post-treatment; this initial improvement became much more consistent when assessed approximately three weeks after the cessation of IL-10 blockade, suggesting that early treatment during the afferent and innate phase of infection favorably impacted the efferent and adaptive phase of infection. We investigated this hypothesis by focusing on immune effector mechanisms previously shown to be critical for fungal clearance in this model. Although dominated by Th2 responses (45), prior studies have shown that both IFNγ and IL-17A are essential for preventing progressive fungal lung infection and dissemination to the CNS (17, 22, 27). Our results showing that early αIL-10 Ab treatment increased the numbers of Th1 and Th17 cells not only underscore the importance of these cells to fungal clearance but, for the first time, show that IL-10 is actively impairing the induction of these cellular subsets even during the very early phases of infection. Early αIL-10R Ab treatment also increased the accumulation of exudate macrophages; these non-resident macrophages derived from recruited Ly-6Chigh monocytes are more fungicidal than resident alveolar macrophages (20). Their fungicidal activity would be further enhanced under conditions of IL-10 blockade by the increased numbers of Th1 cells producing IFNγ in the lung microenvironment.

We observed that IL-10 production is sustained during the development of the efferent and adaptive response in this model (measured at 14 dpi) and even later on into the persistent phase of infection (measured at 28 dpi). By delaying αIL-10R Ab treatment until the latter stage of infection, we were able for the first time to test whether this persistent presence of IL-10 within the infected microenvironment was continuing to actively suppress effector immune responses. Indeed this was the case as evidenced by our finding that late αIL-10R Ab treatment improved fungal clearance in the lung with the most pronounced effect observed at 35 dpi. Similar to what we observed with early αIL-10R Ab treatment, late treatment increased the numbers of Th1 cells as Th17 cells in the lung and also promoted increased accumulation of activated exudate macrophages expressing higher amounts of MHC Class II and CD80. In contrast to early treatment, late IL-10 blockade also increased numbers of CD11b+ DC and B cells. These DC expressed higher amounts of CD80 (than those in the lungs of isotype control-treated mice) and thus may promote effector Th1 responses against C. neoformans (18, 19, 36). B cells might also improve cryptococcal clearance (50) perhaps through Ab-mediated improvements in the phagocytic activity of lung macrophages as recently described (51, 52).

Our results show that both early and late treatment with αIL-10 Ab decreased the fungal burden of Cryptococcus within the CNS. These findings may have important clinical implications as CNS dissemination and menigoencephalitis are the leading cause of mortality in human cryptococcal disease (1). Interestingly, mice in the early treatment group showed no evidence of fungal growth in the brain when assessed 72 hours after the last dose of αIL-10R Ab (at 12 dpi). Yet when assessed at 35 dpi, CNS growth was detected, suggesting that delayed growth within the brain may be possible in the absence of ongoing IL-10 blockade during the established phase of infection. In contrast, late treatment with αIL-10Ab during this established phase almost completely abrogated CNS growth when assessed at 35 dpi. Future studies will need to address whether these mice might relapse and to determine whether extending treatment, perhaps at weekly intervals with or without concurrent anti-fungal antibiotics, would further augment or sustain the reductions in pulmonary and CNS fungal burden achieved using IL-10 blockade.

In our experiment of acute systemic cryptococcal infection by the intravenous route, we observed no differences in brain fungal growth in mice receiving αIL-10R Ab versus mice receiving isotype control when assessed 48 hours post-infection. This finding suggests that IL-10 blockade does not immediately alter the blood-brain barrier. We also observed no difference in fungal growth in the lung, spleen, or blood suggesting that the very initial innate immune events in these organs were not profoundly altered by IL-10 blockade. Collectively, our data suggest that the reduction in lung fungal burden observed in mice treated with αIL-10R Ab may promote containment of the organism within the lung and thereby reduce CNS dissemination. In support of this hypothesis, we observed increased numbers of activated exudate macrophages in the lungs of mice treated with αIL-10R Ab consistent with our prior studies demonstrating that increases in the number and activation of lung exudate macrophages correlates with improved fungal clearance and reductions in fungal dissemination (17, 20, 37). Alternatively, our studies have not completely ruled out that IL-10 blockade may promote more effective adaptive immunity within the CNS against C. neoformans. Comprehensive studies investigating this intriguing possibility and potential cellular sources of IL-10 in the lung would be of interest, but exceed the scope of the current study.

Collectively, our findings support an evolving paradigm based on a dynamic balance between effector and regulatory networks as the critical determinant of whether host-pathogen interactions in the lung result in clearance or persistence. Our data shows that sustained IL-10 production plays a central role in determining this balance during both the developing and established phases of infection. Numerous Cryptococcal virulence strategies are associated with increased expression of IL-10 including expression of its polysaccharide capsule, laccase, and its interference with macrophage scavenger receptor A (14, 26, 53–56), showing that C. neoformans can exploit the IL-10 signaling pathway to oppose protective effector mechanisms. Importantly, the current study illustrates our ability to block this regulatory pathway, thereby restoring and potentially enhancing protective immune effector mechanisms which improve fungal clearance. Furthermore, this strategy improved fungal clearance in mice with established lung infection highlighting the translational potential of using this approach to treat patients with persistent lung infections caused by invasive fungi or mycobacterium.

Supplementary Material

The abbreviations used are

- DC

dendritic cells

- dpi

days post infection

- ExM

exudate macrophages

- i.t.

intratracheal

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- AF

autofluorescent

- CNS

central nervous system

- IL

interleukin

- Ab

antibody

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Supported by a Career Development Award-2 (J.J.O), Merit Review Awards (J.J.O. and M.A.O.) from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs and an NIH T32 Training Grant (T32 HL007749; B.J.M., trainee).

Portions of this work have been presented previously at the International Conference of the American Thoracic Society, Philadelphia, PA, May 20, 2013

References

- 1.Li SS, Mody CH. Cryptococcus. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:186–196. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-063AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozzette SA, Larsen RA, Chiu J, Leal MA, Jacobsen J, Rothman P, Robinson P, Gilbert G, McCutchan JA, Tilles J, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of maintenance therapy with fluconazole after treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. California Collaborative Treatment Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:580–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102283240902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora S, Olszewski MA, Tsang TM, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Effect of cytokine interplay on macrophage polarization during chronic pulmonary infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1915–1926. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01270-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olszewski MA, Zhang Y, Huffnagle GB. Mechanisms of cryptococcal virulence and persistence. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1269–1288. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyktor JC, Turner J. Interleukin-10 and immunity against prokaryotic and eukaryotic intracellular pathogens. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2964–2973. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00047-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saraiva M, O'Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabat R, Grutz G, Warszawska K, Kirsch S, Witte E, Wolk K, Geginat J. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lortholary O, Improvisi L, Rayhane N, Gray F, Fitting C, Cavaillon JM, Dromer F. Cytokine profiles of AIDS patients are similar to those of mice with disseminated Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6314–6320. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6314-6320.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh N, Husain S, Limaye AP, Pursell K, Klintmalm GB, Pruett TL, Somani J, Stosor V, del Busto R, Wagener MM, Steele C. Systemic and cerebrospinal fluid T-helper cytokine responses in organ transplant recipients with Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Transplant immunology. 2006;16:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monari C, Baldelli F, Pietrella D, Retini C, Tascini C, Francisci D, Bistoni F, Vecchiarelli A. Monocyte dysfunction in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) versus Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect. 1997;35:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)93042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vecchiarelli A, Pietrella D, Lupo P, Bistoni F, McFadden DC, Casadevall A. The polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans interferes with human dendritic cell maturation and activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:370–378. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Monari C, Tascini C, Bistoni F, Kozel TR. Purified capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans induces interleukin-10 secretion by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2846–2849. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2846-2849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monari C, Retini C, Palazzetti B, Bistoni F, Vecchiarelli A. Regulatory role of exogenous IL-10 in the development of immune response versus Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:242–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4021303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez Y, Arora S, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct roles for IL-4 and IL-10 in regulating T2 immunity during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:1027–1036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murdock BJ, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA, Osterholzer JJ. IL-17A enhances host defense against cryptococcal lung infection through effects mediated by leukocyte recruitment, activation, and IFN-gamma production. Infect Immun. 2013 doi: 10.1128/IAI.01477-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osterholzer JJ, Curtis JL, Polak T, Ames T, Chen GH, McDonald R, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. CCR2 mediates conventional dendritic cell recruitment and the formation of bronchovascular mononuclear cell infiltrates in the lungs of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2008;181:610–620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osterholzer JJ, Chen GH, Olszewski MA, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Accumulation of CD11b+ lung dendritic cells in response to fungal infection results from the CCR2-mediated recruitment and differentiation of Ly-6Chigh monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183:8044–8053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterholzer JJ, Chen GH, Olszewski MA, Zhang YM, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Chemokine receptor 2-mediated accumulation of fungicidal exudate macrophages in mice that clear cryptococcal lung infection. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zar L. Biostatistical analysis. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora S, Hernandez Y, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Role of IFN-gamma in regulating T2 immunity and the development of alternatively activated macrophages during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:6346–6356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen GH, Osterholzer JJ, Choe MY, McDonald RA, Olszewski MA, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Dual roles of CD40 on microbial containment and the development of immunopathology in response to persistent fungal infection in the lung. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2459–2471. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beenhouwer DO, Shapiro S, Feldmesser M, Casadevall A, Scharff MD. Both Th1 and Th2 cytokines affect the ability of monoclonal antibodies to protect mice against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6445–6455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6445-6455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blackstock R, Buchanan KL, Adesina AM, Murphy JW. Differential regulation of immune responses by highly and weakly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3601–3609. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3601-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerrero A, Fries BC. Phenotypic switching in Cryptococcus neoformans contributes to virulence by changing the immunological host response. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4322–4331. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00529-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen GH, McDonald RA, Wells JC, Huffnagle GB, Lukacs NW, Toews GB. The gamma interferon receptor is required for the protective pulmonary inflammatory response to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1788–1796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1788-1796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen GH, McNamara DA, Hernandez Y, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Inheritance of immune polarization patterns is linked to resistance versus susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2379–2391. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szymczak WA, Sellers RS, Pirofski LA. IL-23 dampens the allergic response to Cryptococcus neoformans through IL-17-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1547–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks DG, Ha SJ, Elsaesser H, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Oldstone MB. IL-10 and PD-L1 operate through distinct pathways to suppress T-cell activity during persistent viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20428–20433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J, Cardani A, Sharma AK, Laubach VE, Jack RS, Muller W, Braciale TJ. Autocrine regulation of pulmonary inflammation by effector T-cell derived IL-10 during infection with respiratory syncytial virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002173. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, Madan R, Karp CL, Braciale TJ. Effector T cells control lung inflammation during acute influenza virus infection by producing IL-10. Nat Med. 2009;15:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nm.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murdock BJ, Falkowski NR, Shreiner AB, Sadighi Akha AA, McDonald RA, White ES, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Interleukin-17 drives pulmonary eosinophilia following repeated exposure to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1424–1436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05529-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. T cell-mediated immunity in the lung: a Cryptococcus neoformans pulmonary infection model using SCID and athymic nude mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1423–1433. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1423-1433.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173:793–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterholzer JJ, Surana R, Milam JE, Montano GT, Chen GH, Sonstein J, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Cryptococcal urease promotes the accumulation of immature dendritic cells and a non-protective T2 immune response within the lung. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:932–943. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu Y, Zeltzer S, Zhang Y, Wang F, Chen GH, Dayrit J, Murdock BJ, Bhan U, Toews GB, Osterholzer JJ, Standiford TJ, Olszewski MA. Early induction of CCL7 downstream of TLR9 signaling promotes the development of robust immunity to cryptococcal infection. J Immunol. 2012;188:3940–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu LY, Ng ES, Koh LP. Common and emerging fungal pulmonary infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:557–577. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brizendine KD, Baddley JW, Pappas PG. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:727–734. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felton TW, Baxter C, Moore CB, Roberts SA, Hope WW, Denning DW. Efficacy and safety of posaconazole for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1383–1391. doi: 10.1086/657306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy CC, Limper AH. Redefining the clinical spectrum of chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis: a retrospective case series of 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:252–258. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318144b1d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, Kumar UN, Mathai G, Varkey B, Kaufman L, Bradsher RW, Stoebig JF, Davis JP. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602273140901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens DA, Rendon A, Gaona-Flores V, Catanzaro A, Anstead GM, Pedicone L, Graybill JR. Posaconazole therapy for chronic refractory coccidioidomycosis. Chest. 2007;132:952–958. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Limper AH. The changing spectrum of fungal infections in pulmonary and critical care practice: clinical approach to diagnosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:163–168. doi: 10.1513/pats.200906-049AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arora S, Huffnagle GB. Immune regulation during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis: lessons taught by two fungi. Immunol Res. 2005;33:53–68. doi: 10.1385/IR:33:1:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldmesser M, Kress Y, Casadevall A. Effect of antibody to capsular polysaccharide on eosinophilic pneumonia in murine infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1639–1646. doi: 10.1086/515314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huffnagle GB, Boyd MB, Street NE, Lipscomb MF. IL-5 is required for eosinophil recruitment, crystal deposition, and mononuclear cell recruitment during a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection in genetically susceptible mice (C57BL/6) J Immunol. 1998;160:2393–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Humphreys IR, Edwards L, Walzl G, Rae AJ, Dougan G, Hill S, Hussell T. OX40 ligation on activated T cells enhances the control of Cryptococcus neoformans and reduces pulmonary eosinophilia. J Immunol. 2003;170:6125–6132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF. Cells and cytokines in pulmonary cryptococcosis. Res Immunol. 1998;149:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80762-1. discussion 512–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguirre KM, Johnson LL. A role for B cells in resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:525–530. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.525-530.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohatgi S, Pirofski LA. Molecular characterization of the early B cell response to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:5820–5830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szymczak WA, Davis MJ, Lundy SK, Dufaud C, Olszewski M, Pirofski LA. X-linked immunodeficient mice exhibit enhanced susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. MBio. 2013:4. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00265-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerrero A, Jain N, Wang X, Fries BC. Cryptococcus neoformans variants generated by phenotypic switching differ in virulence through effects on macrophage activation. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1049–1057. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01049-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mariano Andrade R, Monteiro Almeida G, Alexandre DosReis G, Alves Melo Bento C. Glucuronoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans exacerbates in vitro yeast cell growth by interleukin 10-dependent inhibition of CD4+ T lymphocyte responses. Cell Immunol. 2003;222:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu Y, Davis MJ, Dayrit JK, Hadd Z, Meister DL, Osterholzer JJ, Williamson PR, Olszewski MA. Immune modulation mediated by cryptococcal laccase promotes pulmonary growth and brain dissemination of virulent Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu Y, Dayrit JK, Davis MJ, Carolan JF, Osterholzer JJ, Curtis JL, Olszewski MA. Scavenger receptor A modulates the immune response to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2013;191:238–248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.