Abstract

This article presents data on health care spending for the United States, covering expenditures for various types of medical services and products and their sources of funding from 1960 to 1995. In 1995, $988.5 billion was spent to purchase health care in the United States, up 5.5 percent from 1994. Growth in spending between 1993 and 1995 was the slowest in more than three decades, primarily because of slow growth in private health insurance and out-of-pocket spending. As a result, the share of health spending funded by private sources fell, reflecting the influence of increased enrollment in managed care plans.

Introduction

In today's health care system, providers and third-party payers face intense pressures. Increases in health care spending during the late 1980s and early 1990s in relation to overall economywide growth focused the attention of purchasers on the problems of rising costs. As the Federal Government attempted to control cost increases associated with Medicare and Medicaid, employers sponsoring health insurance for their workers evaluated alternatives to conventional private health insurance (PHI) plans more intensely. Both the private and public sectors reacted with increased enrollment in managed care plans. Under heightened pressure from managed care plans to reduce cost growth, health care providers were transformed from “revenue generators” who individually orchestrated activity within the health care system to “cost centers” within a larger, managed care system (Duke, 1996). Faced with competition for patients, an increased proportion of providers are responding to incentives to minimize costs. Managed care plans negotiated rate discounts with providers in return for provider access to large groups of patients; these plans also altered patterns of care through an emphasis on preventive services and elimination of unnecessary care, and demanded cost-conscious decisionmaking by providers in the delivery of health care. Faced with lower expected revenue growth, providers were forced to find ways to reduce expense growth to remain financially viable and competitive.

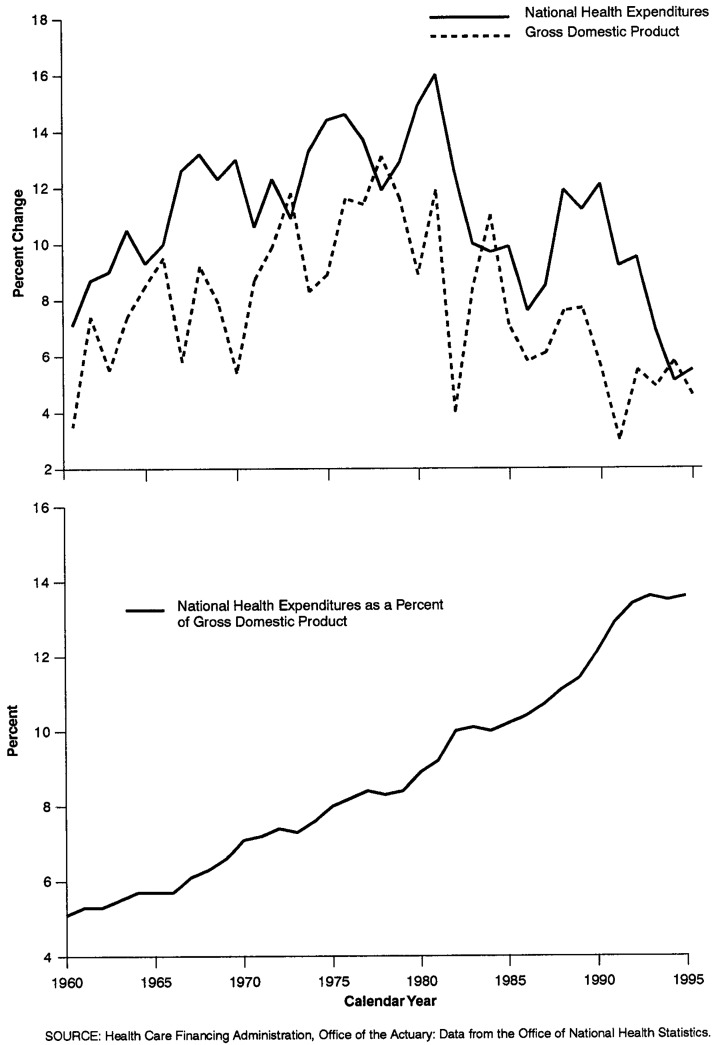

Health system changes are reflected in the matrix of spending trends recorded in national health expenditures (NHE). Most prominently, growth in health spending in 1994 and 1995 reached its lowest points in more than three decades of measuring health care spending (Figure 1). Nominal expenditures grew 5.1 percent in 1994 and 5.5 percent in 1995; real (inflation-adjusted)1 growth measured 2.7 percent in 1994 and 2.8 percent in 1995. Decelerating growth reflects changes occurring within the provider and PHI components of the health care industry during the 1990s.

Figure 1. Percent Growth in National Health Expenditures and Gross Domestic Product, and National Health Expenditures as a Percent of Gross Domestic Product: Calendar Years 1960-95.

During the 1993-95 period, health care spending as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) exhibited virtually no change: It stabilized between 13.5 and 13.6 percent (Figure 1). There were three additional periods since 1960 when the NHE share of GDP remained stable for 3-year periods: 1964-66, 1977-79, and 1982-84. Each of these periods was characterized by strong GDP growth. For the first time in more than three decades, however, stability in NHE as a percent of GDP in the 1993-95 period was precipitated by a slowdown in the rate of growth of health care spending, rather than an upswing in overall economic growth.

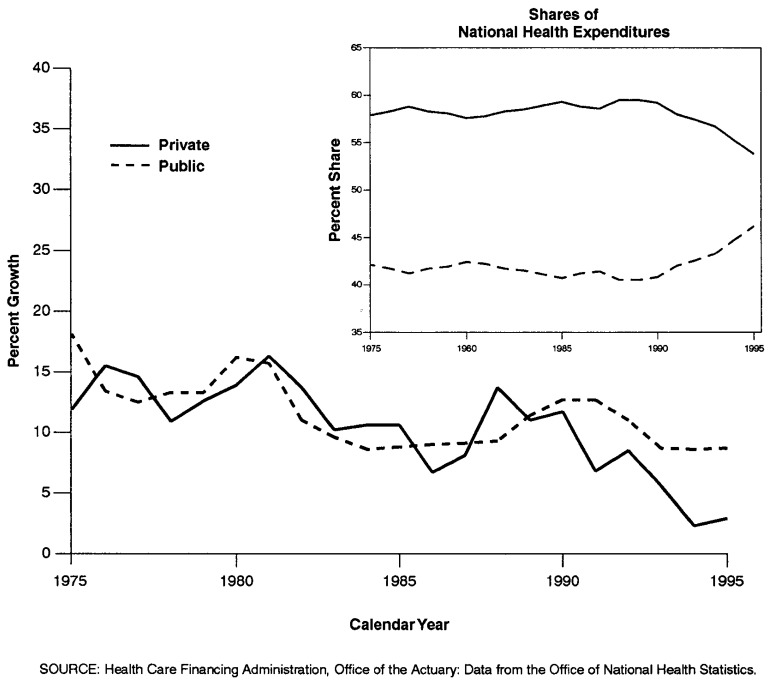

The effects of health system changes are evident in the contrast between private and public sector financing. From 1960 to 1990, growth in spending by both the private and public sectors was similar, with only two notable exceptions: the period 1966-67, when Medicare and Medicaid were introduced, and the period 1974-75, which recorded the effects of the 1973 expansion of Medicare to cover the disabled population. Each of these major expansions in public program coverages produced offsetting, step-wise shifts in public and private financing responsibilities, with the share shouldered by the public sector increasing. The unique feature of the shift toward a larger public share beginning in 1990 is that it was not driven by public sector initiatives to add new populations or expand services, although the number of people covered by the Medicaid program did increase. In fact, public sector expenditure growth has continued at approximately the same average annual rate since 1990 (9.9 percent) as between 1980 and 1990 (10.5 percent). At the same time, average annual growth in private spending decelerated markedly between 1990 and 1995, to 5.2 percent, from the 11.2-percent average annual growth experienced during the 1980-90 period (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percent Growth and Percent Share of Public and Private National Health Expenditures: Calendar Years 1975-95.

The disparity in growth among different types of personal health care (PHC) services narrowed in 1995. For all services except other personal health care, spending growth ranged from a low of 4.5 percent (for hospital services) to a high of 8.9 percent (for dental services). The one exception, other personal health care services, which accounts for 2.8 percent of PHC, is dominated by Medicaid home- and community-based waivers and miscellaneous services that are provided by non-health care establishments.2 Spending for this sector grew 14.9 percent in 1995, faster than all other PHC sectors, but slower than it did in 1994 (Table 1).

Table 1. Personal Health Care Expenditure Aggregate Amounts, Percent Distribution, and Average Annual Percent Change, by Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1960-95.

| Type of Expenditure | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| Personal Health Care | $23.6 | $63.8 | $217.0 | $376.4 | $614.7 | $676.6 | $740.5 | $786.9 | $827.9 | $878.8 |

| Hospital Care | 9.3 | 28.0 | 102.7 | 168.3 | 256.4 | 282.3 | 305.4 | 323.3 | 335.0 | 350.1 |

| Physician Services | 5.3 | 13.6 | 45.2 | 83.6 | 146.3 | 159.2 | 175.7 | 182.7 | 190.6 | 201.6 |

| Dental Services | 2.0 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 21.7 | 31.6 | 33.3 | 37.0 | 39.2 | 42.1 | 45.8 |

| Other Professional Services | 0.6 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 16.6 | 34.7 | 38.3 | 42.1 | 46.3 | 49.1 | 52.6 |

| Home Health Care | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 13.1 | 16.1 | 19.6 | 23.0 | 26.3 | 28.6 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 4.2 | 8.8 | 21.6 | 37.1 | 59.9 | 65.6 | 71.2 | 75.0 | 77.7 | 83.4 |

| Prescription Drugs | 2.7 | 5.5 | 12.0 | 21.2 | 37.7 | 42.1 | 46.6 | 49.4 | 51.3 | 55.5 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 0.6 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 6.7 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.8 |

| Nursing Home Care | 0.8 | 4.2 | 17.6 | 30.7 | 50.9 | 57.2 | 62.3 | 67.0 | 72.4 | 77.9 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 0.7 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 17.9 | 21.7 | 25.0 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||||||

| Personal Health Care | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hospital Care | 39.3 | 43.9 | 47.3 | 44.7 | 41.7 | 41.7 | 41.2 | 41.1 | 40.5 | 39.8 |

| Physician Services | 22.4 | 21.3 | 20.8 | 22.2 | 23.8 | 23.5 | 23.7 | 23.2 | 23.0 | 22.9 |

| Dental Services | 8.3 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| Other Professional Services | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.0 |

| Home Health Care | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 18.0 | 13.8 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.5 |

| Prescription Drugs | 11.3 | 8.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.3 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Nursing Home Care | 3.6 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 8.9 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 2.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Average Annual Percent Change from Previous Year Shown | ||||||||||

| Personal Health Care | — | 10.5 | 13.0 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 6.1 |

| Hospital Care | — | 11.7 | 13.9 | 10.4 | 8.8 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Physician Services | — | 9.9 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 5.8 |

| Dental Services | — | 9.1 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 5.6 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 8.9 |

| Other Professional Services | — | 8.8 | 16.3 | 21.2 | 15.8 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 6.1 | 7.0 |

| Home Health Care | — | 14.5 | 26.9 | 18.9 | 18.4 | 22.4 | 22.3 | 17.1 | 14.4 | 8.6 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | — | 7.6 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 |

| Prescription Drugs | — | 7.5 | 8.2 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 10.6 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 8.1 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | — | 9.6 | 8.8 | 12.4 | 9.2 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 7.2 |

| Nursing Home Care | — | 17.4 | 15.4 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 9.0 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 7.5 |

| Other Personal Health Care | — | 6.5 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 12.9 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 16.4 | 21.6 | 14.9 |

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

The changing distribution of health care spending mirrors the impact of managed care and, to a lesser extent, changes in Medicare payment policies. The share of PHC expenditures spent on hospital and physician services has declined over the past 5 years, while spending on home health services, nursing home care, and other personal health care services has increased. These increases have paralleled increases in Medicare spending for home health and skilled nursing facility services.

In the rest of this article, we describe the changes occurring in several key sectors of the health care industry, focusing on their impact on health care spending trends. Data cited in the remaining discussion but not shown in an accompanying table or figure can be found in Figure 9 and Tables 8-17 at the end of this article.

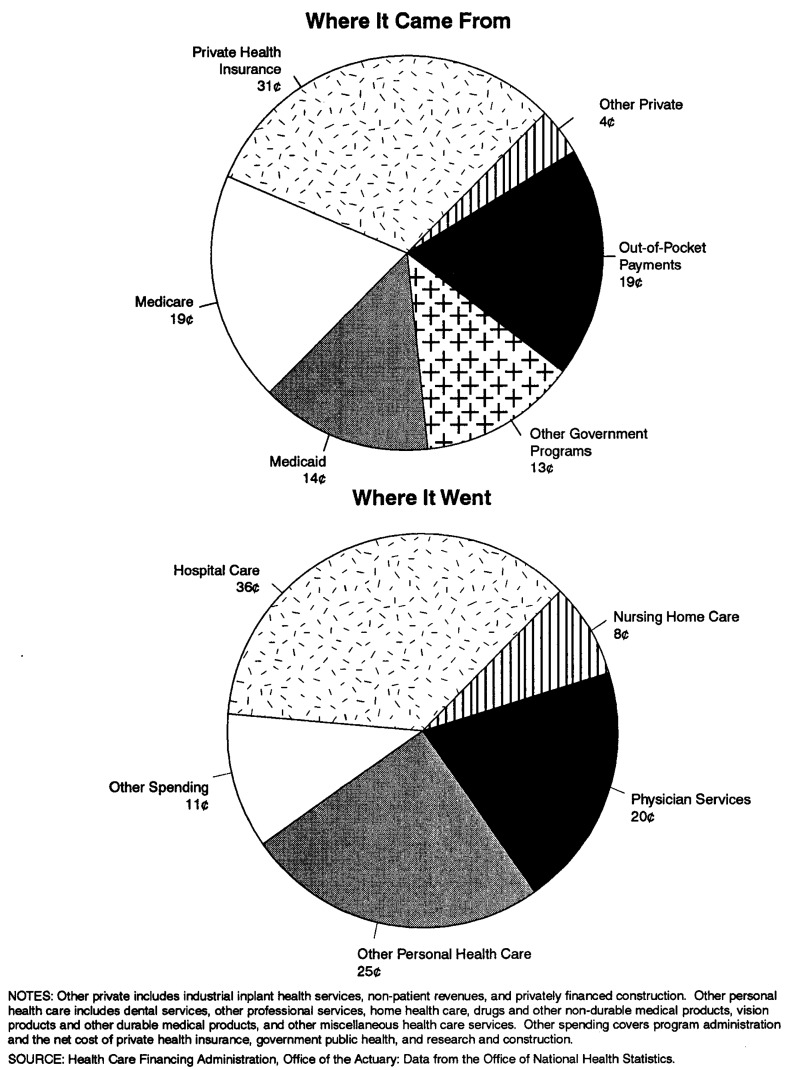

Figure 9. The Nation's Health Dollar: Calendar Year 1995.

Table 8. National Health Expenditures Aggregate and per Capita Amounts, Percent Distribution, and Average Annual Percent Growth, by Source of Funds: Selected Years 1960-95.

| Item | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | $26.9 | $73.2 | $247.2 | $428.2 | $697.5 | $761.7 | $834.2 | $892.1 | $937.1 | $988.5 |

| Private | 20.2 | 45.5 | 142.5 | 253.9 | 413.1 | 441.4 | 478.8 | 505.5 | 517.2 | 532.1 |

| Public | 6.6 | 27.7 | 104.8 | 174.3 | 284.3 | 320.3 | 355.4 | 386.5 | 419.9 | 456.4 |

| Federal | 2.9 | 17.8 | 72.0 | 123.3 | 195.8 | 224.4 | 253.9 | 277.6 | 301.9 | 328.4 |

| State and Local | 3.7 | 9.9 | 32.8 | 51.0 | 88.5 | 95.9 | 101.6 | 108.9 | 118.0 | 128.0 |

| Number in Millions | ||||||||||

| U.S. Population1 | 190.1 | 214.8 | 235.1 | 247.1 | 260.0 | 262.6 | 265.2 | 267.9 | 270.4 | 273.0 |

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| Gross Domestic Product | $527 | $1,036 | $2,784 | $4,181 | $5,744 | $5,917 | $6,244 | $6,553 | $6,936 | $7,254 |

| Per Capita Amount | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | $141 | $341 | $1,052 | $1,733 | $2,683 | $2,901 | $3,145 | $3,330 | $3,465 | $3,621 |

| Private | 106 | 212 | 606 | 1,027 | 1,589 | 1,681 | 1,805 | 1,887 | 1,913 | 1,949 |

| Public | 35 | 129 | 446 | 705 | 1,094 | 1,220 | 1,340 | 1,443 | 1,553 | 1,672 |

| Federal | 15 | 83 | 306 | 499 | 753 | 855 | 957 | 1,036 | 1,116 | 1,203 |

| State and Local | 20 | 46 | 140 | 206 | 341 | 365 | 383 | 407 | 436 | 469 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 75.2 | 62.2 | 57.6 | 59.3 | 59.2 | 58.0 | 57.4 | 56.7 | 55.2 | 53.8 |

| Public | 24.8 | 37.8 | 42.4 | 40.7 | 40.8 | 42.0 | 42.6 | 43.3 | 44.8 | 46.2 |

| Federal | 10.9 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 28.8 | 28.1 | 29.5 | 30.4 | 31.1 | 32.2 | 33.2 |

| State and Local | 13.9 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 12.9 |

| Percent of Gross Domestic Product | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | 5.1 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 13.6 |

| Average Annual Percent Growth from Previous Year Shown | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | — | 10.6 | 12.9 | 11.6 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 6.9 | 5.1 | 5.5 |

| Private | — | 8.5 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 6.8 | 8.5 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| Public | — | 15.3 | 14.2 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Federal | — | 19.8 | 15.0 | 11.4 | 9.7 | 14.6 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.8 |

| State and Local | — | 10.2 | 12.7 | 9.2 | 11.6 | 8.3 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 8.4 |

| U.S. Population | — | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Gross Domestic Product | — | 7.0 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 4.6 |

July 1 Social Security area population estimates for each year, 1960-95.

NOTE: Numbers and percents may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Table 17. Expenditures for Health Services and Supplies Under Public Programs, by Type of Expenditure and Program: Calendar Year 1995.

| Program Area | All Expenditures | Personal Health Care | Administration | Public Health Activities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Total | Hospital Care | Physician Services | Dental Services | Other Professional Services | Home Health Care | Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | Nursing Home Care | Other | ||||

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||||||

| Public and Private Spending | $957.8 | $878.8 | $350.1 | $201.6 | $45.8 | $52.6 | $28.6 | $83.4 | $13.8 | $77.9 | $25.0 | $47.7 | $31.4 |

| All Public Programs | 436.7 | 392.1 | 214.3 | 64.0 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 5.1 | 45.3 | 21.7 | 13.2 | 31.4 |

| Federal Funds | 314.4 | 303.6 | 175.3 | 50.9 | 1.0 | 9.6 | 13.8 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 29.3 | 12.8 | 7.1 | 3.8 |

| State and Local Funds | 122.2 | 88.5 | 39.0 | 13.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 16.0 | 8.9 | 6.1 | 27.6 |

| Medicare | 187.0 | 184.0 | 112.6 | 40.0 | — | 7.8 | 11.6 | — | 4.6 | 7.3 | — | 3.0 | — |

| Medicaid1 | 141.0 | 133.1 | 52.0 | 14.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 9.8 | — | 36.2 | 13.8 | 7.9 | — |

| Federal | 86.8 | 83.1 | 37.2 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 5.6 | — | 20.3 | 7.8 | 3.6 | — |

| State and Local | 54.2 | 50.0 | 14.8 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 4.2 | — | 15.9 | 6.0 | 4.2 | — |

| Other State and Local Public Assistance Programs | 5.4 | 5.4 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | — | — |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | 15.6 | 15.5 | 12.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | — | — | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | — |

| Department of Defense2 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 10.5 | 1.6 | 0.0 | — | — | 0.2 | — | — | 0.9 | 0.2 | — |

| Workers' Compensation | 19.8 | 18.1 | 8.8 | 6.7 | — | 2.1 | — | 0.4 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.7 | — |

| Federal | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | — | 0.1 | — | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | — | 0.0 | — |

| State and Local | 19.2 | 17.5 | 8.5 | 6.6 | — | 2.0 | — | 0.4 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.7 | — |

| State and Local Hospitals3 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 12.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other Public Programs for Personal Health Care4 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.0 | — | 0.0 | 0.1 | — | 6.1 | 0.3 | — |

| Federal | 7.2 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.9 | — | 0.0 | 0.1 | — | 3.6 | 0.1 | — |

| State and Local | 3.4 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | — | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | 2.5 | 0.2 | — |

| Government Public Health Activities | 31.4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 31.4 |

| Federal | 3.8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3.8 |

| State and Local | 27.6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 27.6 |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 328.0 | 317.1 | 164.6 | 54.3 | 1.6 | 9.2 | 15.7 | 9.8 | 4.6 | 43.5 | 13.8 | 10.9 | — |

Excludes funds paid into the Medicare trust funds by States under buy-in agreements to cover premiums for Medicaid recipients.

Includes care for retirees and military dependents.

Expenditures not offset by revenues.

Includes program spending for maternal and child health; vocational rehabilitation medical payments; temporary disability insurance medical payments; Public Health Service and other Federal hospitals; Indian health services; alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health; and school health.

NOTES: The figure 0.0 denotes amounts less than $50 million. Numbers may not add to total because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Hospital Care

Hospital care expenditures, the single largest component of personal health spending at 39.8 percent, amounted to $350.1 billion in 1995. Registering growth of less than 5 percent in the last 2 years, spending for hospital services was among the slowest growing of any PHC services.

The American Hospital Association's (1995) panel survey of community hospitals reports that overall admissions per 1,000 population increased in 1995 by 0.4 percent, the first such increase in more than a decade. Growth in admissions per 1,000 population in 1995 comes from admissions for the population age 65 and over; meanwhile, admissions per 1,000 for the population under age 65 continued to decline but at a slower rate. Despite the slight increase in admissions per 1,000 population, inpatient days in community hospitals continued to fall by almost 3 percent overall, indicating declining overall length of stay. When the number of beds is not reduced to match the decline in days, occupancy rates fall and excess capacity grows. In 1995 overall occupancy rates in community hospitals fell to less than 60 percent (Heffler et al., 1996), the lowest rate in history. Such rates put renewed pressure on hospitals to develop new sources of revenues, to negotiate with managed care plans for access to patients, and to integrate both horizontally with other local and national hospital organizations and vertically with physicians and other health care providers and insurers (Duke, 1996).

An increasing number of hospitals are expanding their lines of business to provide more than just inpatient and outpatient hospital care. In addition to fitness facilities and home health care agencies, they are using excess bed capacity to add rehabilitation and skilled nursing or subacute care facilities to broaden their revenue base (Lewin-VHI, Inc., 1995). Creating subacute care facility units from underused inpatient units enables hospitals to compete for the followup institutional care that discharged patients often need for full recovery. Incentives exist for hospitals to discharge patients as soon as possible: Medicare's inpatient hospital payment is diagnosis-based and prospectively determined, regardless of length of hospital stay. Managed care plans, which often pay for hospitalization on a daily rate, also encourage fewer inpatient days. But community nursing homes, traditionally providing custodial services and limited medical care, are frequently not staffed and equipped to handle patients discharged from hospitals “quicker and sicker.” Hospitals with a subacute care unit can discharge patients from their hospital stays quickly and admit them to the skilled-nursing or subacute care unit for their followup care, maximizing their revenue from the overall stay. Under Medicare, a hospital is compensated for the inpatient stay on a prospectively determined diagnosis-related group (DRG) basis and the nursing or subacute facility stay on a reasonable-cost basis (Anders, 1996).

With the rise of enrollment in managed care plans and falling occupancy rates, hospitals have been forced to consider the benefits of mergers and alliances with local and national hospital organizations. Squeezed by high operating expenses, competition from market-area providers, and the prices managed care organizations were willing to pay providers for services, hospitals have sought alliances with similar community facilities or with national chains. Some alliances have been based on geographic location and others on religious affiliation. Most have been aimed at integrating services, reducing competition, and increasing cooperation in order to compete effectively for managed care business (Duke, 1996). Increasingly, largely consolidated for-profit hospital organizations are buying non-profit facilities facing difficulties in the highly competitive hospital marketplace. For-profit chains strengthen the market position of acquired facilities by cutting costs. Communities worry, however, that takeovers of their local facilities will threaten the existence of hospital-provided charity and preventive services and cost jobs in their community (Langley and Sharpe, 1996; Rundle, 1996).

Expenditures for inpatient services in community hospitals accounted for 62 percent of all hospital revenues in 1995 (Table 2). Growth in inpatient expenditures has slowed since 1990, paralleling decreases in inpatient days and length of stay. Some of this deceleration can be attributed to the rise of managed care. According to the HMO and PPO Industry Profile, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), the most restrictive type of managed care plan, cover about 20 percent of the resident population. “HMO members experience fewer total hospital days per thousand, fewer admissions per thousand, and shorter average lengths of stay than the population at large … HMO members were hospitalized about two-thirds as often as the population as a whole in 1993 [and] … spent about half as many days in the hospital. Growth in other types of managed care organizations (especially PPOs) and the increasing use of utilization review by indemnity health insurance plans” may also have contributed to this trend (Dial et al., 1996).

Table 2. Hospital Revenues, Percent Distribution, and Annual Percent Growth: Calendar Years 1990-95.

| Type of Hospital | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues in Millions | ||||||

| Total | $256,447 | $282,272 | $305,357 | $323,272 | $334,966 | $350,120 |

| Non-Federal | 238,570 | 262,533 | 284,665 | 301,217 | 312,323 | 326,877 |

| Community | 221,604 | 245,476 | 267,881 | 284,891 | 296,333 | 311,283 |

| Inpatient | 169,221 | 183,516 | 196,452 | 206,410 | 210,426 | 216,593 |

| Outpatient | 52,383 | 61,960 | 71,429 | 78,481 | 85,907 | 94,691 |

| Non-Community | 16,966 | 17,057 | 16,784 | 16,326 | 15,990 | 15,594 |

| Federal | 17,877 | 19,739 | 20,692 | 22,055 | 22,643 | 23,242 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Non-Federal | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| Community | 86 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 89 |

| Inpatient | 66 | 65 | 64 | 64 | 63 | 62 |

| Outpatient | 20 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 27 |

| Non-Community | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Federal | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Annual Percent Growth | ||||||

| Total | 10.7 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Non-Federal | 10.9 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 4.7 |

| Community | 11.3 | 10.8 | 9.1 | 6.3 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| Inpatient | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 5.1 | 1.9 | 2.9 |

| Outpatient | 18.9 | 18.3 | 15.3 | 9.9 | 9.5 | 10.2 |

| Non-Community | 5.6 | 0.5 | -1.6 | -2.7 | -2.1 | -2.5 |

| Federal | 8.9 | 10.4 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

NOTE: Non-community non-Federal hospitals include long-term care hospitals (where the average length of stay is 30 days or longer), psychiatric hospitals, alcohol and chemical dependency hospitals, units of institutions such as prison hospitals or college infirmaries, chronic disease hospitals, and some institutions for the mentally retarded.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Nearly all hospital care was financed by third parties in 1995, with only 3.3 percent paid by consumers in out-of-pocket expenditures. PHI accounted for a 32.3-percent share. Total public funding accounted for a 61.2-percent share; Medicare and Medicaid, the primary subset of public payers, financed 47.0 percent of hospital care. The remaining 3.2 percent of hospital revenues came from philanthropic and non-patient sources, such as hospital gift shops, parking facilities, and cafeterias.

Physician Services

Expenditures for physician services reached $201.6 billion in 1995, an increase of 5.8 percent from the previous year. Spending for services in this sector accounted for 22.9 percent of PHC. For the last 3 years, growth in spending for physician services has been lower than the growth in overall PHC expenditures. This slow growth is linked to the expansion of managed care.

The health care system in the United States has historically been controlled by providers, with physicians typically deciding type and place of treatment. In recent years, the growth of managed care has caused the locus of control to shift from provider to insurer (Zwanziger and Melnick, 1996), with the insurer having more input into treatment plans. This fundamental change in the health care delivery system has been precipitating changes in the organization of physician practices, demand for types of physician specialties, utilization of physician services, and income of physicians. In 1993 and 1994, these changes contributed to the slowdown of growth in expenditures for physician services. By 1995 physician expenditures showed a slight upturn in growth rate, although growth was still lower than the growth in PHC spending. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that increased utilization and referral to specialists may be part of the reason for the slight acceleration in growth (Wooton, 1996; Rice et al., 1996).

The share of physician expenditures funded by PHI rose between 1990 and 1995, consistent with managed care's emphasis on services provided by primary care physicians. Meanwhile, the share funded by Medicare remained unchanged as a result of the implementation of the Medicare Fee Schedule (MFS) to pay physicians for services and volume performance standards (VPS) to limit the effect of induced utilization increases.3 Payment mechanisms used by both managed care and Medicare put pressure on physicians to curb expenditure growth. There is no evidence to suggest that physicians shifted costs to private insurers with the advent of the MFS because physicians were restrained by market forces from raising prices.4 Managed care and MFS caused spending growth to drop to 5.8 percent in 1995 from 11.5 percent in 1990.

Changes in the way physicians deliver services are evident in U.S. Bureau of the Census (1996) data on revenue sources of physician offices.5 From 1992 to 1994, the percentage of revenues earned from the delivery of inpatient hospital services fell, while those earned through the delivery of services in doctors' offices and hospital outpatient settings rose (Table 3). Part of the decline in percentage of revenues from hospital services may be associated with falling number of inpatient days.

Table 3. Sources of Receipts in Physician Offices:1 Calendar Years 1992-94.

| Source of Receipts | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Amount in Billions | Percent Distribution | |||||

| Total | $141.4 | $144.5 | $150.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Patient Care and Other Professional Services | 137.7 | 140.9 | 147.2 | 97.4 | 97.5 | 97.9 |

| Patient Care Services | 130.5 | 133.6 | 139.9 | 92.3 | 92.4 | 93.0 |

| Laboratory Services | 7.2 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| X-Ray Services | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 9.3 |

| Hospital Inpatient Services | 31.8 | 30.4 | 31.1 | 22.5 | 21.0 | 20.7 |

| Hospital Outpatient Services | 16.7 | 17.9 | 19.1 | 11.8 | 12.4 | 12.7 |

| Services Delivered in Physician Offices | 59.6 | 62.6 | 67.0 | 42.2 | 43.3 | 44.6 |

| Other Services Delivered at Other Sites | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Other Medical Professional Services | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.8 |

| Merchandise Sales | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Prescription Drugs | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Other | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| All Other Sources | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

Information for taxable employer firms only.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census: Data from the Services Annual Survey, 1994.

Growth in managed care enrollment had a direct impact on physician organizations. The number of physicians signing contracts with managed care organizations is on the rise: In 1990, 61 percent of physicians had a managed care contract; by 1995 that proportion had grown to 83 percent. Although physician participation in managed care had grown substantially, the percent of revenues received through managed care contracts grew more slowly: from 28 percent in 1990 to 33 percent in 1995 (Emmons and Simon, 1996).

As the number of managed care contracts has increased, the structure of physician practices has changed. Group practices have become more prevalent. Physicians have joined together in larger group practices to offer the breadth of services necessary to attract managed care contracts and to consolidate expenses. Groups can also absorb some of the risk associated with managed care contracts. Within physician practices, the proportion of physicians who are employed has increased, while the proportion of physicians in solo practices or self-employed in group practices has declined (Kletke, Emmons, and Gillis, 1996). Employed physicians tend to work fewer hours, see fewer patients, and earn lower income than physicians who own a practice (American Medical Association, 1996). As the number of employed physicians increases, earnings of physicians on average could fall.

In 1994 physicians' income decreased for the first time in recent history. This may be a result of the growth in managed-care contracts. The decline was more pronounced for the high earners, while the income of low earners continued to rise (Simon and Born, 1996). The decline also affected primary care physicians and procedure-oriented physicians differently. Primary care physicians' income increased faster than average, while the income of procedure-oriented physicians declined or increased at a slower-than-average rate (Moser, 1996).

As the impact of managed care on the health industry has increased, there has been more emphasis on primary and preventive care and less on the services of specialists. Since 1990 the demand for specialists has dropped, as measured by physician recruitment advertising, while the demand for generalists has been rising (Seifer, Troupin, and Rubenfeld, 1996). This change in type of physician will also affect the future of medical schools and the type of training available to incoming students. As an indication of this trend, the percent of recently graduated residents unable to find full-time jobs in their specialties amounted to more than 6 percent in two hospital-based specialities (anesthesiology and pathology) and one surgical specialty (plastic surgery). Similar rates for various primary care specialists were 2.1 percent or less (Miller, Jonas, and Whitcomb, 1996).

Utilization of physician services remained stable over the 1993-94 period at approximately 6 contacts per person per year, after rising steadily from 5.3 contacts per year in 1989 (National Center for Health Statistics, 1996). The contribution to the increase in number of physician contacts per person differed by age group. For the population age 65 years or over, the number of physician contacts per person grew consistently between 1989 and 1994 but experienced a particularly large increase between 1990 and 1991. For the population age 15-64, utilization increased between 1989 and 1992 but has remained fairly constant since (Table 4), possibly a response to increased enrollment in managed care.

Table 4. Physician Contacts1 per Person, by Age: Calendar Years 1987-94.

| Age Group | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Number | ||||||||

| Total2 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Under 15 Years | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

| 15-44 Years | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| 45-64 Years | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.3 |

| 65 Years or Over | 8.9 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 11.3 |

A consultation with a physician (or another person working under a physician's supervision) in person or by telephone, for examination, diagnosis, treatment, or advice. Place of contact includes office, hospital outpatient clinic, emergency room, telephone, home, clinic, health maintenance organization, and other places located outside a hospital.

Age-adjusted.

SOURCE: (National Center for Health Statistics, 1995).

Prescription Drugs

Americans purchased $55.5 billion worth of prescription drugs in 1995 (Table 5). Prescription drug spending growth was slower than that of PHC in 1993 and 1994 (6.1 and 3.8 percent, respectively) but jumped to 2 percentage points faster than PHC in 1995 (8.1 percent). Surveys show that about two-thirds of the accelerated 1995 growth comes from an increase in the number of prescriptions sold. Depending on the survey used, this increase ranged from 5.7 (IMS America, 1996) to 7.8 percent (Schondelmeyer and Seoane-Vazquez, 1996).

Table 5. Expenditures for Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables,1 by Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1990-95.

| Source of Funds | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||

| Drugs and Non-Durable Medical Products | $59.9 | $65.6 | $71.2 | $75.0 | $77.7 | $83.4 |

| Prescription Drugs | 37.7 | 42.1 | 46.6 | 49.4 | 51.3 | 55.5 |

| Out-of-Pocket Payments | 18.2 | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 21.9 |

| Third-Party Payments | 19.5 | 22.9 | 26.2 | 28.2 | 29.9 | 33.6 |

| Private Health Insurance | 13.0 | 15.2 | 18.0 | 19.1 | 19.8 | 22.1 |

| Medicaid | 5.1 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 9.8 |

| General Assistance | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Other Government | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Non-Prescription Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables2 | 22.2 | 23.4 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 26.4 | 27.9 |

| Out-of-Pocket Payments | 22.2 | 23.4 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 26.4 | 27.9 |

| Percent Distribution by Source of Funds Within Each Category | ||||||

| Prescription Drugs | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Out-of-Pocket Payments | 48 | 46 | 44 | 43 | 42 | 40 |

| Third-Party Payments | 52 | 54 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 60 |

| Private Health Insurance | 35 | 36 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 40 |

| Medicaid | 14 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| General Assistance | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Other Government | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-Prescription Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Out-of-Pocket Payments | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

This class of expenditure measures spending for prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines, and sundries purchased in retail outlets. The value of drugs and other products provided by hospitals, nursing homes, or health professionals is included in estimates of spending for these providers' services.

Assumes no third-party payments for non-prescription drugs and other medical non-durables.

NOTE: Numbers and percentages may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

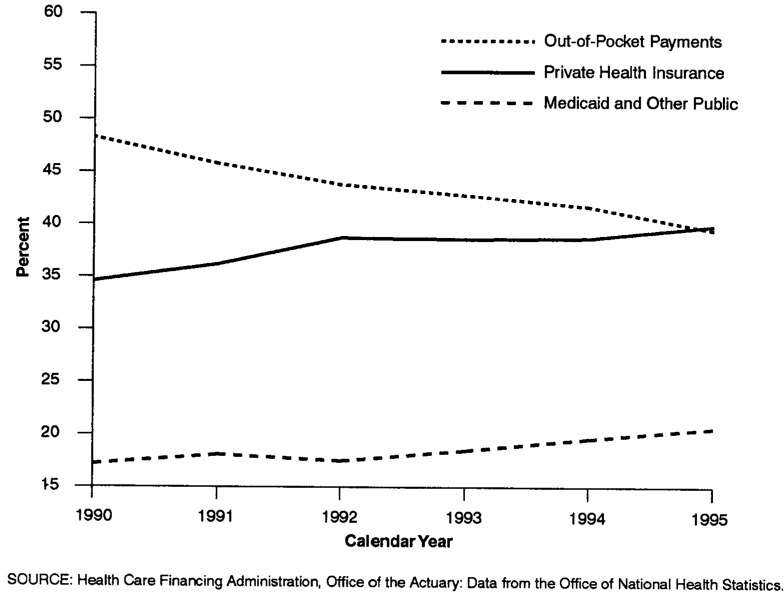

The key to the utilization changes lies in changes in the sources paying for prescription drugs: Third parties are absorbing an increasing share of prescription drug expenditures. Between 1990 and 1995, the share of prescription drug spending paid out of pocket fell 9 percentage points, offset by larger shares paid by third-party payers: PHI share increased 5 percentage points and the Medicaid share increased 4 percentage points (Figure 3). Even smaller payers, such as the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, through the latter's Civilian Health and Medical Program for the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS), experienced impressive growth in drug expenditures.

Figure 3. Prescription Drug Spending, by Type of Payer: Calendar Years 1990-95.

There are several contributing reasons for high prescription drug spending growth in 1995. First, the existence of third-party coverage increases the likelihood that individuals will fill prescriptions, and the switch to managed care increases the likelihood even more. More than 9 out of 10 employees enrolled in an employer-sponsored health plan in medium and large firms had coverage for outpatient prescription drugs throughout the 1980s and 1990s (Baker and Kramer, 1995). Although most medical plans have covered outpatient drugs for many years, the shift of plan subscribers between traditional fee-for-service plans and managed care plans has had an effect on out-of-pocket payment requirements. In traditional fee-for-service plans, outpatient prescription drugs are typically covered under general plan coverages that require a yearly deductible. Under a deductible arrangement, the plan subscriber is responsible for all medical charges, including prescription drug charges, until those charges exceed the deductible.6 By contrast, HMO plans require only a nominal dollar copayment per prescription, typically $3 or $5 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994). The relatively low out-of-pocket costs of prescription drugs in HMOs and other managed care plans may help to explain the recent growth in the demand for and utilization of prescription drug benefits.

Although pharmaceutical manufacturers initially feared that managed care plans would restrict drugs sales, they now believe that managed care has been partly responsible for recent increases in prescription drug sales. To reduce the use of more expensive services, prescription drugs are frequently ordered as an inexpensive way to control chronic illnesses uncovered through preventive screening. Low copayments required by managed care plans also encourage patients to fill more prescriptions than they did when facing higher copayments or deductibles or the entire cost of the prescription.

Second, the sites where drugs are dispensed are changing, with more prescriptions being filled in retail outlets.7 Fewer prescriptions are dispensed in the hospital setting (partly because of fewer inpatient days) and potentially more in the retail market. Hospital purchases of prescription drugs remained flat over the past 3 years, at $10 billion (IMS America, 1996). This differs significantly from the retail pharmacy experience, where the number of prescriptions dispensed through drug stores, mass merchandisers, food stores, and mail-order firms grew 5.7 percent from 1994 to 1995, the second-largest growth recorded in recent history. The growth of managed care has boosted sales of drugs through mail-order firms. Mail order is frequently used to purchase drugs used to treat chronic conditions, estimated to cover 60 percent of prescription drug sales in 1995 (Day, 1996). Prompted by employers interested in cutting prescription drug costs, managed care plans emphasize use of mail order. Cost savings from mail-order firms come through bulk purchasing and processing of prescriptions. However, there is concern that mail-order firms, often subsidiaries of drug manufacturers, may favor the drugs of parent drug manufacturers on their formulary list (Genuardi, Stiller, and Trapnell, 1996).

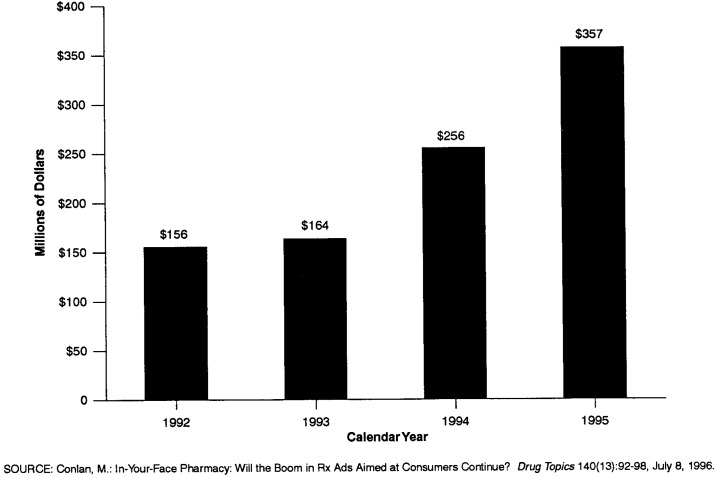

Third, increased spending on prescription drug advertisements may be influencing consumers to request specific brand-name drugs from physicians (Tanouye, 1996). Spending on direct-to-consumer prescription advertisements has more than doubled since 1992 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Spending by Prescription Drug Manufacturers for Direct-to-Consumer Advertisements: Calendar Years 1992-95.

Fourth, one obvious factor in expenditure growth is price per prescription. Prices increased 1.9 percent in 1995 as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and 2.7 percent as measured by the Producer Price Index (PPI).8 In addition, manufacturers began to constrain the growth of rebates in 1995. NHE subtracts rebates paid by manufacturers to third-party payers, such as private insurance and Medicaid, thus decreasing the price paid by third parties. Therefore, when rebate growth slowed in 1995, price growth reflected in NHE estimates accelerated. Industry observers state that manufacturers have moved to “performance-based” rebates, where specific volume or sales quotas must be met in order for a rebate to be paid. Manufacturer rebates to Medicaid also fell as a proportion of total Medicaid drug expenditures. Because Medicaid rebates are based on best prices available to private purchasers, falling rebates in the private market affect rebates paid to Medicaid.

Long-Term Care

Long-term care (LTC) includes spending for care received through freestanding9 nursing homes and home health agencies. This sector accounted for almost one-eighth of PHC expenditures in 1995, or $106.5 billion, with public programs, mainly Medicaid and Medicare, financing 57.4 percent (Table 6). The share of LTC spending paid by Medicare more than doubled from 1990 to 1995. Growth in Medicare expenditures for home health and nursing home care10 accelerated sharply in 1988, when Medicare relaxed its conditions for coverage and payment for these benefits. Also affecting the accelerated growth for nursing home care are lingering effects of the short-lived Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988.

Table 6. Long-Term Care Expenditures for Nursing Home and Home Health Care,1 by Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1990-95.

| Source of Funds | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||

| Total | $64.0 | $73.2 | $81.9 | $90.0 | $98.7 | $106.5 |

| Percent Distribution | ||||||

| Private Funds | 51.7 | 49.0 | 46.9 | 44.9 | 44.0 | 42.6 |

| Out-of-Pocket Payments | 40.4 | 37.8 | 35.9 | 34.1 | 33.3 | 32.5 |

| Private Health Insurance | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| Other Private Funds | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

| Public Funds | 48.3 | 51.0 | 53.1 | 55.1 | 56.0 | 57.4 |

| Federal Funds | 30.9 | 32.6 | 35.3 | 38.0 | 39.1 | 40.5 |

| Medicare | 7.3 | 8.5 | 11.1 | 13.7 | 15.9 | 17.8 |

| Medicaid | 22.0 | 22.6 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 21.6 | 21.1 |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| State and Local Funds | 17.4 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 17.1 | 16.9 | 16.9 |

| Medicaid | 17.3 | 18.3 | 17.6 | 16.9 | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| General Assistance | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Total Medicaid | 39.3 | 40.8 | 40.3 | 39.6 | 38.3 | 37.9 |

| Medicaid and Medicare | 46.6 | 49.3 | 51.4 | 53.3 | 54.2 | 55.6 |

Includes only those expenditures for services provided by freestanding nursing homes and home health agencies. Additional services are provided by hospital-based nursing homes and home health agencies.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Public policy experts are concerned about the large public funding commitment to LTC that is expected to grow even larger over the next several decades. In 1995 there were an estimated 34.2 million people age 65 and over, by the year 2020 this number is expected to increase to 52.8 million (Social Security Administration, 1996). Of all people age 65 and over, 11.3 percent are age 85 or over, the age group at risk of needing nursing home care, and 44.3 percent are age 75 or over, the age group most likely to need services from home health agencies. Growth in the size of the elderly population emphasizes the increasing health care costs for LTC services that this population will generate, much of which comes from public sources.

Private sources, predominately out-of-pocket payments by patients or their families, account for the remaining 42.6 percent of funds spent on LTC. The share of LTC spending from out-of-pocket sources has been falling, mostly offset by the rising share of Medicare spending. Another segment of private funding is PHI. Private health insurers have been aggressively marketing LTC insurance policies. An estimated 3.8 million LTC insurance policies had been sold by December of 1994 (Health Insurance Association of America, to be published). However, despite evidence of increased private insurance coverage, the PHI share of total spending for LTC has changed little over the past 5 years. Consumer advocacy groups are concerned that consumers may not understand the conditions for payment of benefits established by some private health insurers. These conditions may be severely limiting consumers' chances of receiving benefits under their LTC policies. Conditions for payment are based on combinations of impairments related to the need for assistance with activities of daily living (Alecxih and Lutzky, 1996). Policyholders lose coverage when they are unable to afford continued payment of the high premiums required to keep policies in force; the Health Insurance Association of America (1996) estimates a 6-percent average annual lapse rate after the first year for all LTC policies. Also, most policyholders with active policies are healthy with no immediate need for covered services. These factors may be limiting the growth in PHI payments for benefits relative to new contract growth.

Additional expenditures for LTC are included with hospital care in NHE. In 1995, Medicare and Medicaid financed an additional $5.7 billion for hospital-based nursing home care and $6.0 billion for hospital-based home health agency services. Medicaid expenditures for a variety of home- and community-based waivers are considered to be LTC expenditures by some people. Expenditures for these services are included with other personal health care in NHE. In fiscal year 1995, Medicaid funded $2.4 billion for services covered by home- and community-based waivers.

Nursing Home Care

In 1995, spending for nursing home care climbed to $77.9 billion and accounted for 8.9 percent of total spending for PHC. Growth in nursing home care expenditures decelerated from 8.1 percent in 1994 to 7.5 percent in 1995. The nursing home expenditure estimate for 1995 implies a $127 average charge per day for care in freestanding nursing facilities. At that rate, a 1-year stay would cost more than $46,000 in 1995.

The public share of funding for nursing home care increased for the fifth consecutive year. Although Medicaid is the major public payer, funding 46.5 percent of nursing home care in 1995, increases in the public share of nursing home funding resulted from Medicare spending growth. The Medicare share, 9.4 percent in 1995, increased from 3.3 percent in 1990, with expenditures averaging growths of 35 percent annually throughout the period.

Evidence suggests that average national nursing home occupancy rates are declining, thereby creating excess beds11 (DuNah et al., 1995). Competition from alternative forms of health care delivery, such as home health agencies and assisted-living facilities, contributes to declining occupancy and decelerating revenue growth. In response to the slowdown in revenue growth, some nursing homes are converting their unused beds into subacute care units (Lewin-VHI, Inc., 1995). The advantages to nursing facilities of creating a subacute care unit are twofold. First, subacute care units are designed to better accommodate the more intensive nursing care needs of patients discharged from hospitals “quicker and sicker.” Both Medicare, with its PPS, and managed care plans, receiving capitated payments for enrollees' health care needs, exert pressure on hospitals to constrain lengths of stay. Nursing homes that capitalize on this growing market of patients by establishing subacute care units bolster declining occupancy rates. Second, patients requiring these services are more likely to be Medicare or private-pay patients. Given that both Medicare and PHI pay at higher rates than Medicaid, these subacute units could help to produce higher revenue streams.

Because subacute care units require more skilled, better trained, and therefore more costly personnel and more expensive high-technology equipment, expenditures for nursing home care are likely to rise as more facilities convert beds to these type of units.

Home Health Care

Expenditures for freestanding private and public home health agencies amounted to $28.6 billion in 1995. Expenditures for the services and products provided by these agencies were 3.3 percent of PHC expenditures in 1995, a small but increasing share.

Public sources, predominately Medicare and Medicaid, financed 55.3 percent of home health care spending in 1995. Out-of-pocket payments by patients or their families funded one-half of all private spending. PHI and non-patient revenue equally funded the residual portion of private spending.

Growth in spending for home health care decelerated steadily from a high of 28.2 percent in 1990 to 8.6 percent in 1995. In 1988 Medicare relaxed its home health care coverage and eligibility criteria. The number of home health agencies providing these Medicare services grew quickly to meet increased demand by Medicare beneficiaries. Growth in Medicare home health expenditures peaked at 51.5 percent in 1990 and steadily decelerated to 17.9 percent in 1995. The more recent deceleration in growth recorded in the NHE is partially attributable to NHE measuring only payments to freestanding home health agencies as home health care; payments to hospital-based home health agencies are included under hospital care and have been growing faster than those for freestanding agencies. In recent years Medicare has sought to identify and ultimately to prosecute home health providers participating in fraud or abuse activities. This may be having some effect on the industry overall because of Medicare's status as the largest public payer.

Home health agencies seeking to maintain or boost revenue levels are also developing subacute care units (Lewin-VHI, Inc., 1995). As with nursing homes, these units or groups of more highly trained staff are designed to better serve patients discharged from hospitals but still in need of substantial home care for full recovery from their illnesses.

Managed Care

In recent years enrollment in employer-sponsored PHI has shifted dramatically away from conventional fee-for-service insurance into managed care plans. Such plans typically charge lower average premiums than traditional indemnity plans (Foster Higgins, 1994; KPMG Peat Marwick, 1995) by controlling provider costs and utilization of services. In 1986 almost 90 percent of health plan participants in medium and large firms12 enrolled in traditional fee-for-service plans; however, by 1993 the number of participants had dropped to 50 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994). Enrollment in HMOs, typically the most restrictive of the managed care plans, grew from 13 percent to about 23 percent of all employer-plan participants between 1986 and 1993.

The fastest growing type of managed care plan was the preferred provider organization (PPO). These plans grew from 1 percent of health plan participants in 1986 to 26 percent in 1993 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994). PPOs attempt to lower costs by establishing networks of providers that are paid according to negotiated fee schedules. Many traditional fee-for-service plans now also generate a list of preferred providers for participants. The advantage to the participant for using the preferred provider is lower out-of-pocket costs.

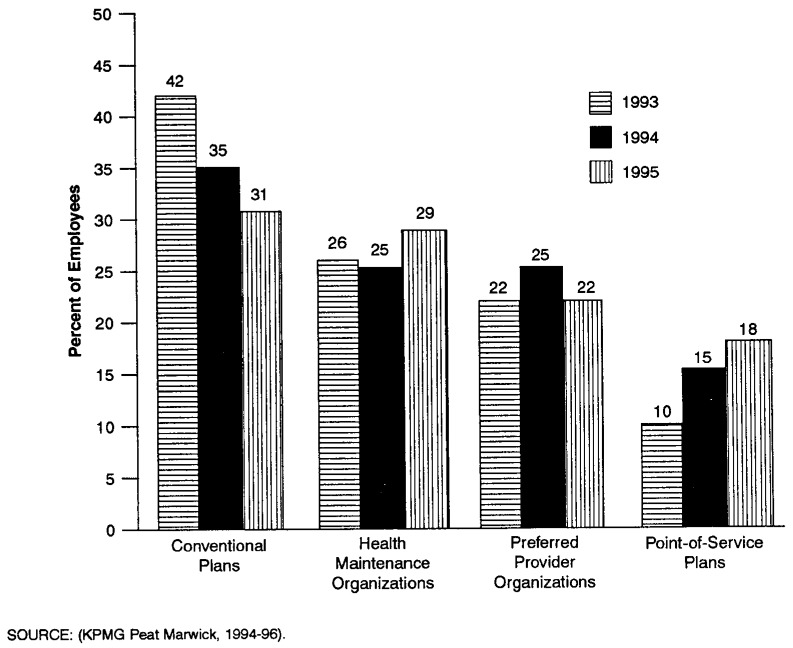

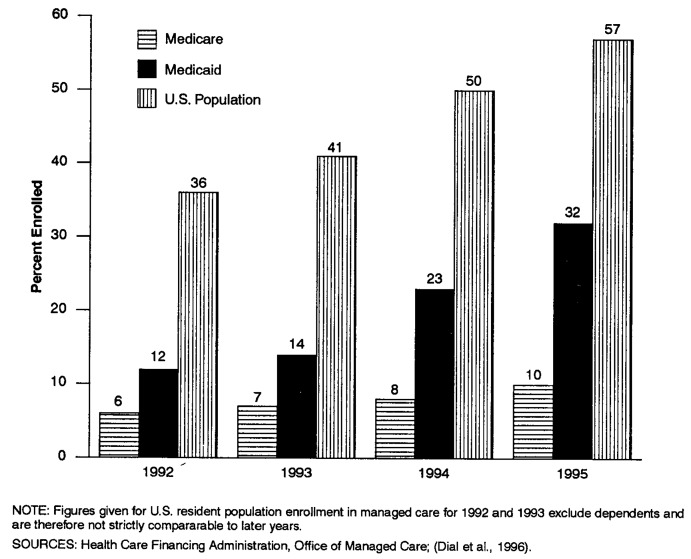

Survey data from KPMG Peat Marwick (1994, 1995) (Figure 5) indicate that employees continue to migrate away from conventional fee-for-service plans and into managed care plans.13 In 1995, HMO enrollment in employer-sponsored plans nearly equaled the enrollment in conventional plans; it is predicted to edge ahead in 1996 (KPMG Peat Marwick, to be published). Almost one-half of the U.S. resident population was covered by an HMO or PPO plan in 1994 (Dial et al., 1996) (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Percent of Employees Enrolled in Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, by Type of Plan: Calendar Years 1993-95.

Figure 6. Percent of Medicare Enrollees, Medicaid Recipients, and U.S. Population Enrolled in Managed Health Care Plans: 1992-95.

Covered Services

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, the breadth of services covered by employer-sponsored PHI greatly expanded. For example, an increasing number of insurance plans began offering home health and hospice care coverage as less expensive alternatives to hospital stays. Much of this expansion was driven by cost-containment strategies aimed at substituting lower cost services for more expensive care and by the desire to attract healthier participants.

The rise in the availability of covered services was accelerated by the migration of employers and employees toward managed care health plans including HMO, PPO, and point-of-service (POS) plans. Managed care health plans, particularly HMOs, were much more likely to provide their members with coverage for many basic preventive services, such as routine physical examinations, well-baby care, well-child care, and immunizations and inoculations. For example, data from KPMG Peat Marwick (1995) indicate that in 1995 HMO enrollees were almost twice as likely to be covered for adult physicals as enrollees in conventional plans.

Although conventional plans have been slow to catch up, many have greatly expanded their coverage during the first half of the 1990s into areas such as adult physicals and well-baby and well-child care. However, despite such increases, these conventional plans still lag most managed care plans, particularly HMOs, in the overall level of preventive services coverage.

Expansions in covered services continued in 1996. More recent survey data from KPMG Peat Marwick indicate that the biggest increases for preventive services were in POS plans. POS plan offerings for both adult physicals and well-child care coverage increased, and HMO plans were increasingly likely to cover chiropractic care. Although just over one-half the HMO plans are now offering such coverage, they still remain far behind non-HMO plans, which almost universally cover chiropractic services.

Medicare

Medicare's Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance programs funded $187 billion of spending for health services and supplies in 1995, an 11.6-percent increase over 1994 spending. Ninety-eight percent of these expenditures were for PHC services for the 37.5 million aged and disabled Medicare beneficiaries enrolled on July 1, 1995.

Medicare is the largest public payer for PHC expenditures and for each of the service components covered by the program except nursing home care. Over time, with few exceptions, Medicare has financed increasingly larger shares of spending for each service component. In 1995 Medicare funded 20.9 percent of spending for PHC, a full percentage point more than it funded in 1994. One-third of all spending for hospital care and one-fifth of expenditures for physician services are funded by Medicare. Faster growth in the Medicare population, compared with the general population, and the aging of frail elderly Medicare enrollees are contributing factors to these increasing funding shares.

Medicare expenditures for hospital care totaled $112.6 billion in 1995, 10.5 percent higher than in 1994. Expenditures for hospital care services cover inpatient, outpatient, and hospital-based home health agency and skilled nursing facility services. Relatively high growth in Medicare hospital expenditures that has continued in recent years may be, in part, the result of expansions of hospital-based, subacute units that allow Medicare patients to be discharged quickly from hospitalization and admitted into the same facility's subacute care unit. This permits hospitals to limit expenses incurred for Medicare hospitalizations, which are compensated at a fixed amount regardless of length of stay, and continue treating the patient under Medicare's cost-based reimbursement policies for skilled nursing home care (Anders, 1996).

Medicare and PHI Comparison

The 1996 Medicare Trustee's Report predicts that growth in Medicare spending will deplete the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund by early in 2001 and recommends that Congress act quickly to reduce the growth in program costs. Such action would extend the date of trust fund exhaustion and provide the time necessary to solve the long-term financial imbalance between costs and income (Board of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, 1996).

The debate over how to fix the imbalance between Medicare income and expenditures inevitably involves raising taxes or lowering expenditure growth. The latter is particularly relevant in 1994-95, when spending growth in Medicare exceeded that of PHI. Between 1993 and 1995, aggregate spending under the Medicare program (benefits plus administrative costs) increased at an 11.3-percent average annual rate, while spending for PHI (benefits plus the net cost of insurance) grew only 2.5 percent annually. Part of the difference is attributable to differential growth in enrollment (Levit et al., 1996). Since the inception of the program, Medicare enrollment has grown at twice the rate of PHI enrollment. In 1995 this trend continued: Medicare enrollment grew 1.6 percent, compared with PHI enrollment growth of 0.9 percent.

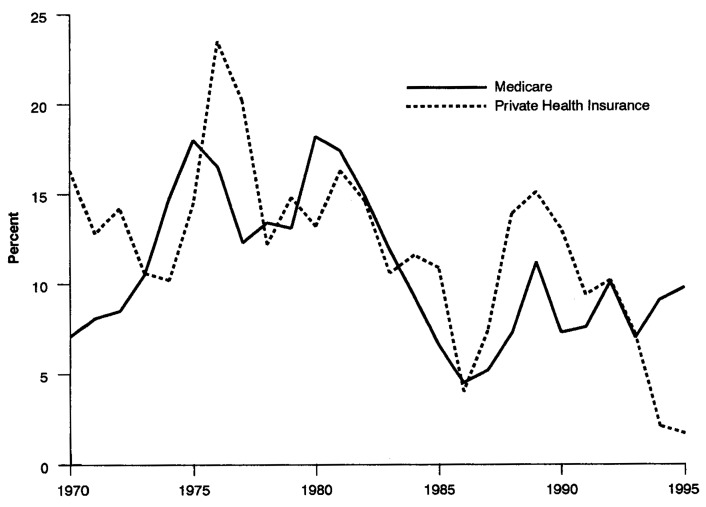

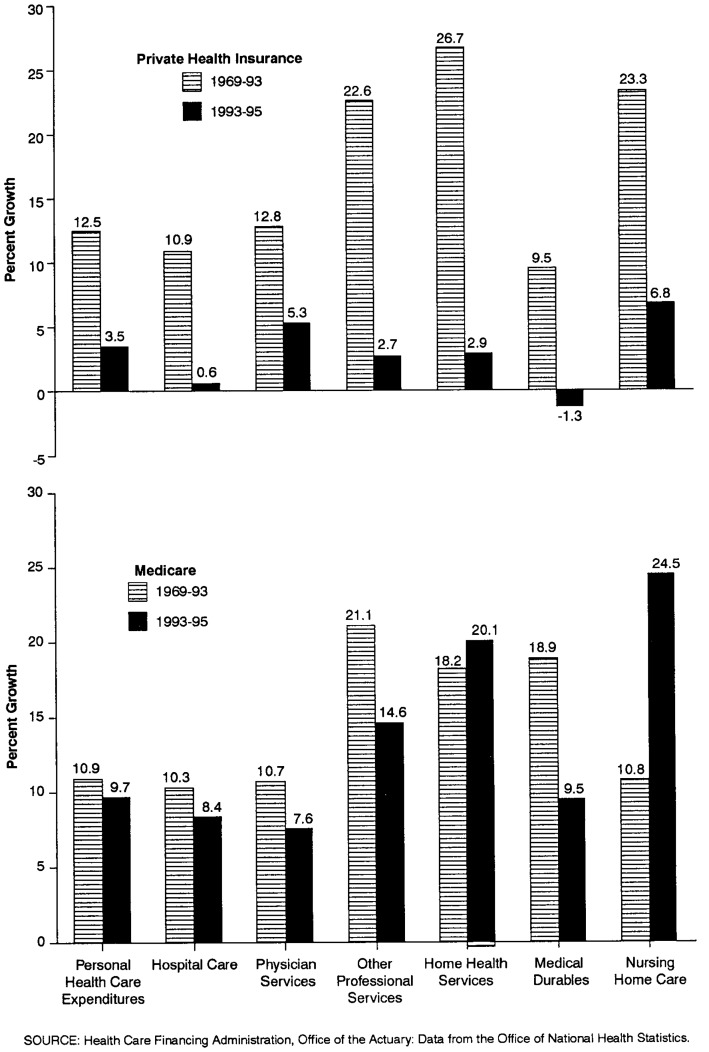

To remove this source of difference, we calculated spending on a per enrollee basis for 1969-95. From 1969 to 1993, per enrollee spending by Medicare and PHI grew at similar rates (Figure 7). During the 1969-93 period, average annual growth in Medicare per enrollee spending was slightly slower than growth in PHI spending overall and for each type of service except durable medical products14 (Figure 8). In 1994 and 1995, trends in growth rates for these two payers suddenly diverged: Average annual growth in Medicare per enrollee spending for all PHC changed very little from past rates, while average annual growth in per enrollee PHI spending decelerated dramatically. Medicare spending for benefits per enrollee grew more than 2.5 times as fast as PHI spending per enrollee.

Figure 7. Growth in per Enrollee Expenditures1 by Medicare and Private Health Insurance: Calendar Years 1970-95.

1Expenditures include benefits and administration for Medicare and benefits and net cost of insurance for private health insurance.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Figure 8. Average Annual Growth in Private Health Insurance and Medicare per Enrollee Benefits: Calendar Years 1969-93 and 1993-95.

Medicare spending growth moderated slightly for each type of service except home health and nursing home care during the 1993-95 period. Expenditure growth in home health and nursing home services was affected by changes in the law and in Medicare regulations, the residual effects of which were still being felt in 1995.15 Medicare's continued strong growth in hospital services parallels the growth in admissions for the population over 65 years of age. It also reflects the NHE definition of hospital services16 that includes not only inpatient services, but outpatient services (including those provided through hospital-based home health agencies) and services in skilled nursing home units that are compensated on a reasonable-cost basis. Strong growth in Medicare physician expenditures is somewhat misleading in that it includes bonuses paid to physicians through the MFS in 1994 and 1995 for their restraint in volume (and intensity) increases in 1992 and 1993.17 Similarly, Medicare will incorporate penalties in its MFS in 1996 and 1997 for volume increases in 1994 and 1995 that exceeded the VPS.

One reason for the difference in Medicare and PHI expenditure growth in 1994 and 1995 is the growth in number of persons enrolled in employer-sponsored managed care plans and managed care's increased influence over providers. Managed care plans negotiate price discounts with providers in return for provider access to large groups of patients; they emphasize preventive services and elimination of unnecessary care; and they demand cost-conscious decisionmaking by providers in the delivery of health care. Each of these aspects serves to limit growth in PHI funding of services. Most Medicare enrollees are not enrolled in HMOs. Providers serving these beneficiaries are paid on a prospectively set basis (for inpatient hospital care) or on a reasonable-cost basis (for most other institutional services). For HMOs enrolling Medicare beneficiaries, Medicare pays 95 percent of the local fee-for-service average reimbursement. Thus, managed care price discounts and other factors present in the larger health care marketplace do not necessarily translate into lower Medicare costs. Because payment is set in law, Medicare has been unable to respond as quickly as PHI to changing market conditions. Experts are still investigating why managed care's costs are low. Is its success caused by elimination of unnecessary utilization, negotiated price discounts, favorable enrollee selection, or some combination of these (Newhouse, 1996)? Has managed care had an impact on quality of health care services? Some policymakers are anxious to move quickly to adopt managed care strategies in hopes of reducing Medicare costs. Other policymakers, citing the issues raised above, prefer to move more cautiously.

Medicaid

Combined Federal and State Medicaid spending for PHC accounted for 15.1 percent of total PHC in 1995, or $133.1 billion. Medicaid largely funds institutional services. In 1995, hospital care and nursing home care accounted for two-thirds (36.9 and 25.7 percent, respectively) of combined Federal and State Medicaid spending. The program is the largest third-party payer of nursing home care, financing 46.5 percent in 1995.

In fiscal year 1995, there were 36.3 million persons who received some type of Medicaid benefit. The groups of children and adults in families with dependent children represented 68.3 percent of all Medicaid recipients in 1995, yet consumed only 26.2 percent of program benefits. Nearly one-half of all Medicaid recipients were children (17.2 million), who consumed only 15.0 percent of all Medicaid benefits. These children also accounted for more than two-thirds of all family-based criteria recipients but consumed only a little more than one-half of the benefits to families. Conversely, the aged, blind, and disabled represented just over one-quarter of all recipients but consumed nearly three-quarters of program benefits (Table 7).

Table 7. Medicaid Recipients and Expenditures by Eligibility Category: Fiscal Year 1995.

| Category | Recipients (Thousands) |

Expenditures (Billions) |

Percent Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Recipients | Expenditures | |||

| All Eligibility Categories1 | 36,282 | $120.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Aged, Blind, and Disabled | 9,977 | 85.9 | 27.5 | 71.5 |

| Families | 24,767 | 31.5 | 68.3 | 26.2 |

| Children | 17,164 | 18.0 | 47.3 | 15.0 |

| Adults2 | 7,604 | 13.5 | 21.0 | 11.2 |

Includes children and aged and non-aged adults categorized as “other” or unknown not shown separately.

Adults in families with dependent children.

NOTE: Data reported on Health Care Financing Administration Form 2082.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, 1995.

Medicaid is funded jointly by Federal and by State and local governments. For a State to receive Federal matching funds, it must adhere to minimum requirements for eligibility and services set by the Federal Government. Within this broad framework, State governments are afforded considerable flexibility in designing the total scope of the program within the constraints of the State budgetary process. One way States use this flexibility is through Medicaid waivers. There are two types of Medicaid waivers: program waivers (including home- and community-based service waivers and freedom-of-choice waivers) and research and demonstration waivers. Home- and community-based waivers18 allow States to place Medicaid-eligible persons into alternative, non-institutional settings for certain types of medical and personal care. Freedom-of-choice waivers19 allow States to place Medicaid beneficiaries into mandatory managed care plans (where beneficiaries have a choice of a minimum of two providers). Research and demonstration waivers (section 1115 of the Social Security Act) allow Federal Medicaid requirements to be waived in order to conduct experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects.

The recent slowdown in Medicaid expenditure growth from 1993 to 1994 (from 12.6 percent to 8.5 percent), which continued in 1995 (8.4 percent), was partially driven by a slowdown in the growth of overall program recipients (7.3 percent in 1993 to 4.8 percent in 1994 and 3.5 percent in 1995). In addition, the change in the proportion of the Medicaid population enrolled in managed care rather than fee for service may also have contributed to the overall expenditure slowdown. State Medicaid programs view managed care as a way to constrain cost growth. In shifting recipients to managed care plans, States also shift the risk for health care costs to the plans. As an increasing number of States employed this cost-containment option, managed care enrollment grew quite rapidly. The Medicaid managed care population represented only 9.5 percent of all Medicaid recipients in fiscal year 1991 but by fiscal year 1995 tripled in share to 32.1 percent. HMOs currently represent 62 percent of all Medicaid managed care programs; prepaid health plans, 25 percent; primary care case management programs, 12 percent; and health insuring organizations, 1 percent (Health Care Financing Administration, 1995).

The slowdown in Medicaid expenditure growth between 1993 and 1994 was also marked by a sharp deceleration in Federal Medicaid spending. (The State share of Medicaid expenditures, however, grew at a steady rate.) There was a marked increase from 1993 to 1994 in the percentage of States with higher-than-average Federal matching rates who also showed lower-than-average expenditure growth. In other words, the poorest States showed the slowest growth in Medicaid spending during this period, which slowed the growth in overall Federal matching contributions. This composition change caused the Federal percentage contribution to Medicaid spending to fall.

Conclusion

This article describes the latest shifts that have occurred within the health care system. Growth in private sector spending fell to low rates between 1993 and 1995, contributing heavily to the slow overall spending growth in those years. NHE as a share of the Nation's output of goods and services was stable for 3 years, breaking the trend of rapid annual increases registered in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Questions about whether these trends will continue and how the Federal sector (primarily Medicare) will react to current changes in the health care marketplace continue to be asked, but the answers are not clear. How will physicians react to slow or negative income growth? How will managed care plans respond to rapid increases in prescription drug use? How will issues of quality and bias selection be addressed by managed care plans? What will happen to managed care premium increases once the transition of privately insured persons to these plans has stabilized? We can watch the answers to these questions unfold in future NHE analyses.

Table 9. National Health Expenditures Aggregate Amounts and Average Annual Percent Change, by Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1960-95.

| Type of Expenditure | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in Billions | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | $26.9 | $73.2 | $247.2 | $428.2 | $697.5 | $761.7 | $834.2 | $892.1 | $937.1 | $988.5 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 25.2 | 67.9 | 235.6 | 411.8 | 672.9 | 736.8 | 806.7 | 863.1 | 906.7 | 957.8 |

| Personal Health Care | 23.6 | 63.8 | 217.0 | 376.4 | 614.7 | 676.6 | 740.5 | 786.9 | 827.9 | 878.8 |

| Hospital Care | 9.3 | 28.0 | 102.7 | 168.3 | 256.4 | 282.3 | 305.4 | 323.3 | 335.0 | 350.1 |

| Physician Services | 5.3 | 13.6 | 45.2 | 83.6 | 146.3 | 159.2 | 175.7 | 182.7 | 190.6 | 201.6 |

| Dental Services | 2.0 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 21.7 | 31.6 | 33.3 | 37.0 | 39.2 | 42.1 | 45.8 |

| Other Professional Services | 0.6 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 16.6 | 34.7 | 38.3 | 42.1 | 46.3 | 49.1 | 52.6 |

| Home Health Care | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 13.1 | 16.1 | 19.6 | 23.0 | 26.3 | 28.6 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 4.2 | 8.8 | 21.6 | 37.1 | 59.9 | 65.6 | 71.2 | 75.0 | 77.7 | 83.4 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 0.6 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 6.7 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.8 |

| Nursing Home Care | 0.8 | 4.2 | 17.6 | 30.7 | 50.9 | 57.2 | 62.3 | 67.0 | 72.4 | 77.9 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 0.7 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 17.9 | 21.7 | 25.0 |

| Program Administration and Net Cost of Private Health Insurance | 1.2 | 2.7 | 11.8 | 23.8 | 38.6 | 38.8 | 42.7 | 50.9 | 50.6 | 47.7 |

| Government Public Health Activities | 0.4 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 11.6 | 19.6 | 21.4 | 23.4 | 25.3 | 28.2 | 31.4 |

| Research and Construction | 1.7 | 5.3 | 11.6 | 16.4 | 24.5 | 24.9 | 27.5 | 29.0 | 30.4 | 30.7 |

| Research1 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 7.8 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 14.2 | 14.5 | 15.8 | 16.6 |

| Construction | 1.0 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 8.5 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 13.4 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 14.0 |

| Average Annual Percent Change from Previous Year Shown | ||||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | — | 10.6 | 12.9 | 11.6 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 6.9 | 5.1 | 5.5 |

| Health Services and Supplies | — | 10.4 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 7.0 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| Personal Health Care | — | 10.5 | 13.0 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 6.1 |

| Hospital Care | — | 11.7 | 13.9 | 10.4 | 8.8 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Physician Services | — | 9.9 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 5.8 |

| Dental Services | — | 9.1 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 5.6 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 8.9 |

| Other Professional Services | — | 8.8 | 16.3 | 21.2 | 15.8 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 6.1 | 7.0 |

| Home Health Care | — | 14.5 | 26.9 | 18.9 | 18.4 | 22.4 | 22.3 | 17.1 | 14.4 | 8.6 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | — | 7.6 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | — | 9.6 | 8.8 | 12.4 | 9.2 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 7.2 |

| Nursing Home Care | — | 17.4 | 15.4 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 9.0 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 7.5 |

| Other Personal Health Care | — | 6.5 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 12.9 | 20.7 | 13.3 | 16.4 | 21.6 | 14.9 |

| Program Administration and Net Cost of Private Health Insurance | — | 8.9 | 15.8 | 15.0 | 10.2 | 0.4 | 10.2 | 19.1 | -0.5 | -5.8 |

| Government Public Health Activities | — | 13.9 | 17.5 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 11.3 |

| Research and Construction | — | 12.2 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 10.5 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 0.8 |

| Research1 | — | 10.9 | 10.8 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 5.8 | 9.8 | 2.2 | 9.3 | 5.0 |

| Construction | — | 12.9 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.6 | -2.4 | 11.2 | 8.7 | 0.5 | -3.8 |

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from research expenditures but are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Office of National Health Statistics.

Table 10. National Health Expenditures, by Source of Funds and Type of Expenditure: Selected Calendar Years 1990-95.

| Year and Type of Expenditure | Total | Private | Government | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| All Private Funds | Consumer | Other | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Total | Out of Pocket | Private Health Insurance | Total | Federal | State and Local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in Billions | |||||||||

| 1990 | |||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | $697.5 | $413.1 | $380.8 | $148.4 | $232.4 | $32.3 | $284.3 | $195.8 | $88.5 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 672.9 | 402.9 | 380.8 | 148.4 | 232.4 | 22.1 | 270.0 | 185.4 | 84.6 |

| Personal Health Care | 614.7 | 371.7 | 350.2 | 148.4 | 201.8 | 21.5 | 243.0 | 178.1 | 64.9 |

| Hospital Care | 256.4 | 115.0 | 104.3 | 10.3 | 94.0 | 10.7 | 141.5 | 106.6 | 34.9 |

| Physician Services | 146.3 | 101.4 | 98.7 | 35.4 | 63.3 | 2.7 | 45.0 | 35.9 | 9.1 |

| Dental Services | 31.6 | 30.7 | 30.6 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Other Professional Services | 34.7 | 28.2 | 25.6 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| Home Health Care | 13.1 | 8.0 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 1.0 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 59.9 | 53.5 | 53.5 | 40.4 | 13.0 | — | 6.5 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 10.5 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 0.9 | — | 2.8 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Nursing Home Care | 50.9 | 25.0 | 24.1 | 22.2 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 25.9 | 15.7 | 10.2 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 11.2 | 2.2 | — | — | — | 2.2 | 9.0 | 5.4 | 3.6 |

| Program Administration and Net Cost of Private Health Insurance | 38.6 | 31.2 | 30.6 | — | 30.6 | 0.6 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 2.5 |

| Government Public Health Activities | 19.6 | — | — | — | — | — | 19.6 | 2.4 | 17.2 |

| Research and Construction | 24.5 | 10.2 | — | — | — | 10.2 | 14.3 | 10.4 | 3.9 |

| Research | 12.2 | 1.0 | — | — | — | 1.0 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 1.7 |

| Construction | 12.3 | 9.3 | — | — | — | 9.3 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 2.2 |

| 1991 | |||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | 761.7 | 441.4 | 407.3 | 155.0 | 252.3 | 34.1 | 320.3 | 224.4 | 95.9 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 736.8 | 431.3 | 407.3 | 155.0 | 252.3 | 24.0 | 305.5 | 213.8 | 91.7 |

| Personal Health Care | 676.6 | 400.0 | 376.6 | 155.0 | 221.6 | 23.4 | 276.6 | 205.8 | 70.8 |

| Hospital Care | 282.3 | 123.1 | 111.6 | 11.2 | 100.4 | 11.5 | 159.2 | 123.8 | 35.3 |

| Physician Services | 159.2 | 110.0 | 107.3 | 35.7 | 71.6 | 2.8 | 49.1 | 38.5 | 10.6 |

| Dental Services | 33.3 | 32.3 | 32.1 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Other Professional Services | 38.3 | 30.6 | 27.6 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 2.9 | 7.7 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

| Home Health Care | 16.1 | 9.3 | 6.8 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 1.2 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 65.6 | 57.9 | 57.9 | 42.7 | 15.2 | — | 7.6 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 11.2 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 0.9 | — | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| Nursing Home Care | 57.2 | 26.5 | 25.4 | 23.4 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 30.7 | 18.4 | 12.3 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 13.6 | 2.4 | — | — | — | 2.4 | 11.1 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| Program Administration and Net Cost of Private Health Insurance | 38.8 | 31.3 | 30.7 | — | 30.7 | 0.6 | 7.5 | 5.3 | 2.2 |

| Government Public Health Activities | 21.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 21.4 | 2.7 | 18.7 |

| Research and Construction | 24.9 | 10.1 | — | — | — | 10.1 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 4.1 |

| Research | 12.9 | 1.1 | — | — | — | 1.1 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 1.9 |

| Construction | 12.0 | 9.0 | — | — | — | 9.0 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| 1992 | |||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | $834.2 | $478.8 | $442.8 | $165.8 | $277.0 | $36.0 | $355.4 | $253.9 | $101.6 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 806.7 | 467.8 | 442.8 | 165.8 | 277.0 | 25.0 | 338.9 | 242.1 | 96.8 |

| Personal Health Care | 740.5 | 433.4 | 409.0 | 165.8 | 243.2 | 24.4 | 307.1 | 233.5 | 73.6 |

| Hospital Care | 305.4 | 129.2 | 117.4 | 11.7 | 105.7 | 11.8 | 176.1 | 141.5 | 34.7 |

| Physician Services | 175.7 | 123.1 | 120.3 | 38.2 | 82.1 | 2.8 | 52.6 | 40.8 | 11.8 |

| Dental Services | 37.0 | 35.7 | 35.5 | 18.2 | 17.3 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Other Professional Services | 42.1 | 33.2 | 30.2 | 16.0 | 14.2 | 3.0 | 8.9 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| Home Health Care | 19.6 | 10.8 | 7.9 | 5.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 1.4 |

| Drugs and Other Medical Non-Durables | 71.2 | 63.0 | 63.0 | 45.0 | 18.0 | — | 8.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| Vision Products and Other Medical Durables | 11.9 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 0.9 | — | 3.7 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

| Nursing Home Care | 62.3 | 27.6 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 34.7 | 21.5 | 13.2 |

| Other Personal Health Care | 15.4 | 2.6 | — | — | — | 2.6 | 12.7 | 7.8 | 5.0 |

| Program Administration and Net Cost of Private Health Insurance | 42.7 | 34.4 | 33.8 | — | 33.8 | 0.6 | 8.4 | 5.5 | 2.8 |

| Government Public Health Activities | 23.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 23.4 | 3.0 | 20.4 |

| Research and Construction | 27.5 | 11.0 | — | — | — | 11.0 | 16.5 | 11.8 | 4.7 |

| Research | 14.2 | 1.2 | — | — | — | 1.2 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 2.0 |

| Construction | 13.4 | 9.8 | — | — | — | 9.8 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 2.8 |

| 1993 | |||||||||

| National Health Expenditures | 892.1 | 505.5 | 467.0 | 171.6 | 295.4 | 38.5 | 386.5 | 277.6 | 108.9 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 863.1 | 493.7 | 467.0 | 171.6 | 295.4 | 26.6 | 369.4 | 265.5 | 103.9 |

| Personal Health Care | 786.9 | 453.0 | 426.9 | 171.6 | 255.4 | 26.1 | 333.9 | 255.9 | 78.0 |