Abstract

Medicare beneficiaries face myriad rules, conditions, and exceptions under the Medicare program. As a result, State Information, Counseling, and Assistance (ICA) programs were established or enhanced with Federal funding as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990. ICA programs utilize a volunteer-based and locally-sponsored support system to deliver free and unbiased counseling on the Medicare program and related health insurance issues. This article discusses the effectiveness of the ICA model. Because the ICA programs serve as a vital link between HCFA and its beneficiaries, information about the programs' success may be useful to HCFA and other policymakers during this era of consumer information.

Introduction

Consumers face myriad rules, conditions, and exceptions under the Medicare program. As a result, beneficiaries need information on the gamut of health insurance issues ranging from enrolling in Medicare to obtaining health care services to understanding the claims filing process. Not only must they learn about Medicare's benefits and payment structure, but they are also confronted with decisions regarding the purchase of supplemental insurance, an increasingly important component of a complete health insurance package. Beneficiaries now face additional coverage options such as Medicare SELECT and point-of-service plans. These decisions can have major financial implications, and for some, it is the first time they are making them without the aid of their employer to address questions.

Earlier research has indicated that while beneficiaries typically understand the basic features of their health coverage, they do not have high levels of knowledge, particularly regarding the complex nature of health insurance programs like Medicare (Marquis, 1983; McCall, Rice, and Sangl, 1986; Garnick et al., 1993; Gibbs, 1995). Recent focus group research revealed that some Medicare beneficiaries even lack a very basic understanding about who is eligible for and the purpose of the Medicare program (Frederick/Schneiders, Inc., 1995). Medicare's future promises a competitive consumer choice structure with different kinds of managed care options and ongoing modifications to address Medicare's fiscal problems. Thus, beneficiaries need to be informed about their options so that they can make good coverage decisions (Etheredge, 1996).

HCFA and a handful of other Federal, State, and local agencies, and private sector organizations currently employ various communication strategies to provide information to Medicare beneficiaries. Examples include program guides and brochures, pamphlets, videos, seminars/presentations, telephone hotlines, and on-line computer services accessible through the Internet. Recently, HCFA began planning “HCFA Online,” a major new policy initiative for responding to beneficiary information needs and building a stronger customer service infrastructure with all of its partners. The ultimate goal of HCFA's new communications strategy is improved access to health care and health program information, and increased beneficiary and provider awareness and satisfaction (Vladeck, 1996a). Although educational resources are becoming increasingly available, many beneficiaries still lack an adequate understanding of the Medicare program and need more assistance. People about to become eligible for Medicare (those 60-64 years of age) also need more information (Gibbs, 1995).

Background

Recognizing Medicare beneficiaries' needs in this area, Congress authorized special grant funding to the States for ICA programs as part of OBRA 1990 (Public Law 101-508). The ICA programs were designed to strengthen the capability of States to provide Medicare beneficiaries with “information, counseling, and assistance for securing adequate and appropriate health insurance coverage” (OBRA 1990, Section 4360). ICA programs seek to make the complex regulations and procedures of public programs like Medicare and Medicaid more understandable and accessible to beneficiaries and their families.

Although the States were granted wide latitude in developing and providing such services, they had to meet several requirements. Their primary responsibilities include providing counseling on how to obtain Medicare benefits and file claims, information on other types of health insurance such as supplemental insurance, managed care options, Medicaid and long-term care, and assistance with policy comparison. ICAs must also develop outreach programs, hire and train adequate staff, and institute a referral process involving relevant State agencies (OBRA 1990, Section 4360).

Beginning in 1992, HCFA awarded 52 ICA grants to 49 States, two territories and the District of Columbia.1 Two types of Federal grant awards were made: (1) basic and (2) “coordinated” or managed care. Some programs also received State government funding in various amounts. Basic awards totaling $9 million were given to the States to plan, develop, and implement programs designed to provide ICA services to Medicare beneficiaries. If a State was already operating a counseling program that was “substantially similar” to the program described above, the funds were to be used to develop and implement specific changes, expansions or enhancements.2 Of the 31 States engaged in some type of a health insurance counseling before receiving ICA grant funds, 15 had programs deemed by HCFA to be substantially similar to the required ICA program design. The fact that over one-half the States had attempted to deliver counseling and assistance services to Medicare beneficiaries before the ICA grant program began attests to the perceived need for such services.

ICA basic awards included a fixed and a variable component. The fixed amount was $75,000 for each State and the variable portion was derived using a population-based formula. Another $1 million in grant monies was reserved to fund programs in States with Medicare-approved “coordinated care” plans. These funds were distributed separately so that programs would place special emphasis on activities to promote the availability and understanding of Medicare managed care. Twenty-one States received this separate funding. Congress directly authorized $10 million for the programs for fiscal year (FY) 1992 though FY 1995. In FY 1996, the programs received $4.5 million dollars from HCFA's program management account, with the balance of their usual funding appropriated from the FY 1997 budget.

Congress mandated that an evaluation of the ICA programs be conducted as part of the enabling legislation. This article presents findings based on that evaluation and discusses recent program activities.3 The primary objectives of the study were:

To provide an in-depth review of the development and implementation of ICA programs; and

To collect and analyze data reflecting program characteristics, methods, and utilization.

In the section that follows, we present our data and methods for conducting the evaluation. Next, we discuss the evaluation's findings and conclusions drawn. Because the ICA programs serve as a vital link between HCFA and its beneficiaries, information about the programs' success and their knowledge of Medicare beneficiaries' information needs may be useful to HCFA and to other policymakers. Data contained in this article may also be of interest to the ICA programs which can learn from and about one another.

Data and Methods

The evaluation included both comprehensive on-site case studies in six States and telephone interviews with the universe of programs. The period of performance reviewed was April 1, 1993, through March 31, 1994. The principal criteria used in selecting case study States were age of the program, funding level, geographic diversity, the special issues or subpopulations targeted, and the State agency that administered the program. The six States selected were Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, New Mexico, New York, and Washington State.

The case study process included both on-site interviewing and the review of documents, reports, and aggregate data prepared by program officials. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with personnel in State departments on aging (DOA), departments of insurance (DOI), departments of health, and Medicaid offices. When possible, on-site visits also included attendance at seminars, training sessions or local counseling sites. Active sponsoring agencies-local organizations that provide administrative, facility or personnel support to the ICA programs-were interviewed as part of our case study investigation.

The case study component focused on program development and implementation. During the telephone inventory, we sought qualitative and quantitative performance measures for the reporting period.4 Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted using available quantitative data. These data, along with information on program funding and client savings accrued as a result of counseling interventions, were used to derive simple measures of cost-effectiveness (e.g., cost per unit of service, savings per unit of service, and an overall program benefit-cost ratio). Data from the proposed 1992 ICA budget allocations were also examined.5

Data Limitations

During the data collection process we learned that ICA programs define key data elements differently–not only across States, but also within the same State. The primary reasons for the lack of uniformity are the latitude provided in the enabling legislation and the absence of measurement specifications from HCFA. All States maintain statistics on program utilization; however, the inconsistency of data collection makes it difficult to compare programs. For example, “program contacts” were defined as either of the following:

The number of individuals served by the program for the first time.

The number of sessions conducted (with either new or repeat clients).

Some programs count program contacts as the unique number of individuals served, while others count the number of sessions conducted, and a few count both. The count of unique individuals is a measure of “market penetration” that reflects the effectiveness of the program in reaching its target population. The count of sessions is a measure of program activity or volume that is important for managing resources, but has less value as an indicator of efficiency (i.e., repeat sessions with the same persons might indicate continuing demand by satisfied customers or the need for further assistance on the part of beneficiaries who had unanswered questions after their initial counseling session). These and other data limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Nevertheless, our data provide the only available estimates of ICA program need and use.

The lack of standard data was recently addressed by the ICA Steering Committee, which initiated a task force to develop national reporting standards (Hart, 1996). As of October 1996, the programs were collecting standard performance data.

Program Development and Implementation

Nearly all States have made substantial progress towards developing fully functioning programs and making ICA services available to most Medicare beneficiaries. Although the implementation process was slower for some programs, all programs appeared to conform with the legislative intent. For the most part, programs were designed to use existing State structures and to respond to their own beneficiaries' perceived needs. The majority of programs selected a common approach which utilizes a volunteer-based and a locally-sponsored support system to deliver services.

Most States gave their program a descriptive name and acronym because it was thought to aid in program outreach. Examples of program names are California's “Health Insurance Counseling and Advocacy Program” (HICAP), Florida's “Serving Health Insurance Needs of Elders” (SHINE), and Indiana's “Senior Health Insurance Information Program” (SHIP).

Program Funding

The range of Federal program funding was significant due to the population-based formula used for distribution. In 1992, while the average basic award in the first grant year was approximately $173,000, awards ranged from less than $100,000 (Alaska, the District of Columbia, Delaware, Hawaii, New Hampshire, the Virgin Islands, and Wyoming) to over $500,000 dollars (California, Florida, and New York). Among the 21 States receiving the supplemental coordinated care award, the average award was approximately $48,000. The mean Federal spending for the basic and coordinated care awards combined amounted to $0.65 per elderly Medicare beneficiary.

Eleven of the 15 “substantially similar” programs and 3 other programs also received funding from their State government in support of their ICA program. The average State contribution was approximately $125,000. However, the California and Wisconsin programs received $2 million and $3.4 million, respectively, in State funds. In-kind contributions, such as departmental staff time, overhead, administrative support, and facilities, were more common forms of non-Federal support.

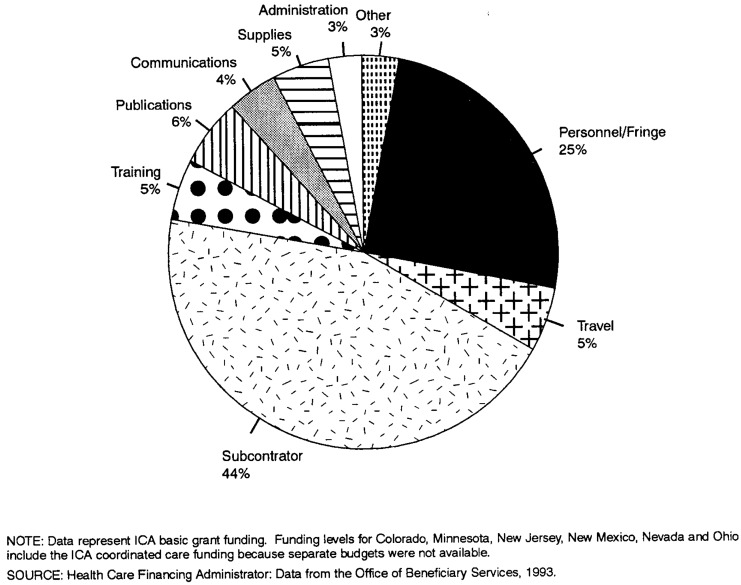

Figure 1 displays the 1992 proposed distribution of basic grant awards by purpose. The largest amount of monies (45 percent) was to be transferred to subcontractors for a variety of services such as training videos, public service announcements, legal assistance, and paying local sponsoring agencies. The second largest expenditure category was personnel and fringe benefits (25 percent). The remaining funds were directed toward publications, training, supplies, travel, communications, and administrative activities.

Figure 1. Proposed Allocation of Information, Counseling, and Assistance (ICA) Basic Grant Funding: October 1992.

Program Organization and Management

The decision regarding which State agency would apply for the ICA grant and manage the program was left to the individual State. Two-thirds of programs are based in the State DOA, 16 are located in the DOI, and 1 is jointly run by both. Although there is not a strong rationale for placing the program in one agency or the other, each agency has strengths and weaknesses in running a Medicare counseling program. For example, DOIs have more direct experience with insurance regulation, while DOAs are probably more knowledgeable about dual eligibility.

Individual agency limitations can be addressed through interagency coordination and support. DOIs and DOAs in some States effectively share information and resource materials. For example, one DOA-based program employs a former DOI staff person as a full-time liaison in the State's DOI to provide technical assistance and training in insurance-specific matters. In our opinion, the majority of the programs could benefit from greater interaction. Some progress in this area has occurred. Beginning in FY 1994, new partnerships between ICA programs and other State agencies, Medicare carriers, fiscal intermediaries, peer review organizations, and the HCFA Regional Offices were formed (Hart, 1996).

Some ICA programs have a centralized organizational structure and others are heavily decentralized. In centralized programs, the State office maintains full leadership and direction of the program and there is a consistent Statewide approach to service delivery, training focus and methods, and volunteer guidelines. Decentralized programs rely on regional coordinators and local sites to direct the program, develop service delivery approaches, training methods, and volunteer guidelines. Not surprisingly, we found that decentralized programs varied more in terms of services, training, and volunteer management from region to region.

Program Staffing

ICA programs were designed to be run as volunteer-based service delivery programs managed by paid professional staff. Most States developed their program in this way, although several chose to use currently employed State/local staff as counselors instead. There were an average of 3 full-time equivalent (FTE) paid staff persons per ICA program, but 19 programs had only 1 FTE or less. Paid staff work directly on the program, whether their salary is supported by grant or State funds. On average, 60 percent of State ICA staff salaries were paid with Federal funds. The remaining 40 percent were supported by State funds, reflecting one of the largest program contributions made by the States. The heavy reliance on Federal monies to support ICA staff suggests that program structure would be severely damaged without Federal support.

In 1994, close to 10,500 individuals across the country volunteered in ICA programs, an average of 222 volunteers per State. Most volunteers are retired professionals, often with some background in insurance, benefits, or business. We found that pre-existing programs had 50 percent more volunteers on average than new programs. Pre-existing programs had a pool of volunteers established before receiving Federal funding and they did not have to spend as much startup time establishing programs, sponsors, and sites.

Sponsoring Organizations

Programs typically rely on local service organizations as a means of providing sponsorship and structuring services. Sponsor support varied from incidental supplies to provision of staff or office space. Organizations that serve as sponsors include Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), Retired Senior Volunteer Programs (RSVPs), 6 legal service organizations (LSOs), senior centers, hospitals, or other facilities that serve seniors. As of early 1994, ICA programs obtained nearly 1,000 sponsors to assist with service delivery. By recruiting other organizations to serve as sponsors, the ICA programs have successfully used existing resources without having to invest heavily in setting up a new regional and local delivery structure.

Program Activities

Volunteer training, counseling, and outreach are the main activities of the ICA programs. Each is discussed here.

Volunteer Training

Over 8,600 volunteers were trained during the 1 year for which data were collected. The average basic training lasts about 20 hours, but ranges from 8 to 40 hours (Table 1). Methods used during the sessions include lecture, classroom exercises, small group discussions, role-playing and feedback. The sessions are conducted by staff trainers, hired subcontractors, or consultants. Basic training is augmented by mandatory update training sessions in 43 States. It is unlikely that training sessions alone enable volunteers to master the varied and complex issues related to Medicare and other insurance products. In some ways, training sessions merely serve as an introduction to the issues and problems faced by beneficiaries.

Table 1. Distribution of Information, Counseling, and Assistance ICA Programs by Length of Volunteer Training Program.

| Training Length (In Hours) |

Number | State | |

|---|---|---|---|

| of States | (Percent) | ||

| 8 | 2 | (4) | TN, VA |

| 9-16 | 12 | (23) | AK, AL, ID, KY, MN, ND, NE, OH, Rl, UT, VT, WV |

| 17-24 | 29 | (56) | AK, AZ, CT, DE, FL, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MD, Ml, MO, MT, NC, NH, NJ, NM, NV, OK, OR, PA, PR, SC, SD, TX, WA |

| 25-32 | 2 | (4) | CO, DC |

| 32 or More | 2 | (4) | CA, MA |

| Not Available | 5 | (10) | ME, MS, NY, Wl, WV |

SOURCE: Case study analysis of ICA programs by Health Economics Research, Inc. and Research Triangle Institute, 1994.

Counseling Services

The primary vehicles for delivering services to Medicare beneficiaries and their representatives are face-to-face counseling, telephone hotlines, seminars/presentations, and written literature. In an individual counseling session, beneficiaries usually come to a central meeting place, such as a senior center, library, or AAA office to meet with an ICA counselor. If requested, some counselors also travel to an individual's home. Some sessions focus on information and education, such as explaining how Medicare Parts A and B work, the differences between medigap plans, or the pros and cons of long-term care insurance. Other sessions focus on assistance with specific problems, such as completing enrollment and claims forms or filing appeals of rejected claims. During the course of the discussion, other needs not initially identified may be revealed. For example, while assisting a client with policy comparison, a counselor may find that the client is possibly eligible for public assistance. Counseling sessions vary from a few minutes to over an hour. Some problems may require several meetings, particularly when the client has outstanding bills from an extensive illness.

Some counseling sites, especially those in rural areas, indicate that their already-established counseling capacities outrun present service demands. However, other locations were in need of additional counselors to address unmet service demands. In order to assure long-term viability, programs experiencing unmet need should focus future activities on program expansion, while programs experiencing underutilization will need to shift their attention towards increased outreach.

Telephone hotlines are a very important information dissemination tool for this program. Although telephone counseling sacrifices personal interaction, it has the advantage of improving access to counseling for the home-bound and disabled, those living in rural areas, and those without transportation. Forty-five States maintain hotlines; however, only one-half of these are operated specifically by the ICA program. The others are general, agency-wide hotlines operated by the grantee or other related agency that provide referrals to local ICA counselors but do not necessarily provide telephone counseling.

Outreach

All ICA programs conduct outreach. The most common methods include group presentations, public service announcements, radio and television advertisements, brochures, newsletters, and booths at health or senior fairs. Virtually all programs use a combination of these methods.

Program Utilization and Outcomes

This section provides estimates of the number of Medicare beneficiaries that use the ICA programs and cost savings generated, and describes the most common issues addressed by counselors.

Program Utilization

Nearly 200,000 people, not quite 1 percent of elderly Medicare beneficiaries, were served between April 1, 1993, and March 31, 1994, by the 33 ICA programs that measure program utilization by the number of individuals served.7 Nearly one-half of the States served fewer than 2,000 individuals. State-specific performance varied substantially, from a low of 1 person per 1,000–in Alabama, Hawaii and South Carolina–to a high of 168 per 1,000 persons-in Montana.8

Thirteen of the 33 programs collecting data on unduplicated service recipients were able to distinguish the number of telephone versus face-to-face contacts. About two-thirds of the contacts were made via telephone, while only one-third were made in person. Some of the phone contacts may have been a simple request for program literature or a referral phone number, while in-person contacts were more likely to include actual counseling. Over 400,000 people participated in an ICA seminar or attended a presentation during the year.

Certain program characteristics, such as program age and funding level, appeared to impact utilization rates.9 Population-adjusted data show that pre-existing programs served 2.4 times as many beneficiaries as new programs. Similarly, programs that received State contributions saw three times as many clients, on average, compared with programs without State contributions. The average number of individuals served by aging-based programs was 70 percent higher than that served by insurance-based programs. These data suggest that more experienced, well-funded programs may be more successful in reaching larger numbers of beneficiaries.

The limitation of statistics on program utilization is that they do not tell us about the quality of the contact with the client. What kind of assistance was provided by the counselor? Was it current, accurate, unbiased, and consistent? Did the client act upon it? What happened as a result of the counseling? Future evaluations of these programs should use beneficiary surveys to assess the actual effect that the information had on the client's knowledge level, decisions made, and confidence in the individual's ability to make good choices.

Types of Health Insurance Issues Addressed

Counseling sessions commonly address the need for general information on Medicare, supplemental insurance, managed care, and appeals. Despite the standardization of medigap policies which facilitates direct policy comparison and more educated purchasing decisions, beneficiaries are still confronted with issues that can be complex (e.g., premium rating practices, pre-existing condition clauses, and the one-time six-month open enrollment period). Other recurring issues include advantages and disadvantages of managed care, the high cost of prescription drugs, and beneficiaries' lack of awareness regarding eligibility and enrollment in public benefits programs. Moreover, the range of managed-care options available to beneficiaries will likely increase.

Over 20,000 individuals were referred for different types of assistance during the reporting period. While Medicaid agencies were the primary referral agency, LSOs, DOIs, and social services and ombudsman's offices were also recipients of ICA referrals. Thirteen ICA programs track referrals. A total of 130 potential fraud and abuse referrals were made to DOIs during the first 3 months of 1994 (the majority identified by the California HICAP program).

Money “Saved” by Clients

The amount of money “saved” as a result of a counseling intervention was an enigma because programs were uncertain how to define and measure program savings. OBRA 1990 instructed States to provide an estimate of the money saved as one way of measuring their accomplishments, but specific measurement criteria were not indicated. It was anticipated that some clients would incur a savings.10 Occasions when a beneficiary might save money as a result of ICA counseling include: (1) getting a claim paid that otherwise would become an out-of-pocket expense; (2) reducing the monthly premium for a supplemental policy when a less expensive alternative was obtained; or (3) avoiding out-of-pocket expenses because Medicaid, Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) program or Specified Low-Income Beneficiary (SLMB)11 program eligibility was established.

The actual amount of money saved depends on the individual situation (e.g., how much was the claim that was filed or how much did the policy cost that was dropped?)12 An advantage to measuring financial benefits is that “dollars saved” demonstrates the economic impact of the program. However, major drawbacks exist. First, each method makes the assumption that a client would not have achieved these savings without program assistance. Second, cost-savings attributable to counseling may not be realized until long after the encounter. It depends, in large part, upon the expediency with which the matter is addressed by the client. Finally, the majority of counseling interventions do not result in a dollar savings. This is quite reasonable given that the purpose of the programs is to provide information, counseling, and assistance and not to expressly generate savings.

Working without guidelines, 33 programs collected financial savings information. A total of $14.7 million was reported as having been saved by beneficiaries during the study year. Most savings were attributed to filing or appealing a health insurance claim.

Cost Ratios

Simple cost ratios were explored as another way of measuring the economic impact of the program. An overall “cost per unit of service” ratio was calculated to measure the average cost of serving each ICA client.13 Of the 35 new programs, 21 monitored the number of individuals served. These programs reported serving 81,561 clients and had combined Federal funding of $3.7 million–meaning that an average of approximately $46 was spent for every person served by the newly created ICA programs. The cost per client served varied from just a few dollars to several hundred dollars. Over time, we anticipate that the cost per person served will decline as programs mature.

Second, an overall benefit-cost ratio–“program savings to spending”–was calculated using data from the 26 new programs that monitor financial savings to beneficiaries. Together these States received $4.1 million in Federal funding and reported $6.2 million in savings–indicating that, on average, financial program benefits exceeded program costs by 50 percent. Averaging the total savings across all beneficiaries served results in a savings of $69 per person counseled; however, the savings varied significantly across beneficiaries.

Conclusions

Federal ICA support reinvigorated and enhanced pre-existing State counseling programs. Initial monies enabled the programs to stabilize, expand, and improve the quality of existing activities. The existence of a State counseling program prior to the Federal grants initiative–whether or not it was deemed substantially similar–was clearly an important factor in the development and growth of the ICA programs. The experience gained via an existing program was instrumental in expediting the start of program activities, including the establishment and strengthening of networks of sponsoring agencies, volunteers, and clients. These programs also benefited from knowledge gained regarding day-to-day program management. For newer programs, the Federal support permitted States to build a program infrastructure and commence counseling activities. Continued funding is required to maintain and build activity levels in all States.

Without Federal funding, it is unlikely that ICA programs would be as strongly supported by the States. Congressional backing for ICA services highlighted the importance of Medicare beneficiaries' information needs and helped to elicit stronger support and in-kind contributions from State, local and non-government organizations. The level of in-kind contributions, the enthusiastic commitment of volunteer counselors–most of whom are Medicare beneficiaries–and the support of public and private sponsoring agencies are very telling. Clearly, the ICA program is perceived as being an important, valuable community service. The voluntary supplementation of Federal and State dollars itself signals that ICA counseling generates substantial benefits, both tangible and intangible.

The programs have demonstrated significant potential, but much of this potential remains to be realized as the programs mature and stabilize over time. Many of the challenges faced by the program stem from their relatively low level of funding, paired with an enormous agenda. Nonetheless, we believe that the ICA “model” is effective, primarily because of its ability to provide in-person customized assistance, which has been found to be desired by Medicare beneficiaries and is rarely available elsewhere (Hanes et al., 1996; Gibbs, 1995). Although some individuals are able to independently utilize written materials, others are less capable of understanding the complexity of the Medicare program on their own and require individualized counseling. As HCFA develops its “On-line” initiative, continuing attention should be given to this form of communication. Having a multitude of media presentations is ideal. Written materials are crucial because they are relatively inexpensive, easy to use, and can be taken home and reviewed at one's leisure. Videos and seminars can be used as companions to the printed materials for complementing and reinforcing the message (McCormack et al., 1996).

Assuming future funding is obtained, the emphasis of the ICA programs over the coming years should be program enhancement–solidifying their operational bases and relationships with old and new partners and staying abreast of ongoing changes in the Medicare program. We offer several specific suggestions for making the programs even more successful.

Interaction and Coordination Among Key Agencies in the State

The strongest need for coordination lies among State DOAs, DOIs, and Medicaid Agencies. The organizations should be aware of each others' activities in order to support an active referral network. Although this feature is instrumental to program effectiveness, it was one of their weaker areas.

Well-Defined and Documented Roles and Responsibilities

Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) that clearly convey the expectations and responsibilities of program participants, particularly those that receive financial support, are imperative. MOUs could also be used between State agencies so that key officials clearly understand their respective roles in the program-whether it be primary, subsidiary or joint. Clearly written and posted job descriptions can inform potential counselors and program staff of their roles. Several programs have developed such materials, but they are not being used to the fullest extent.

Extensive Counselor Training and Retraining

Appropriate counselor training is essential to program success. Training conferences should be conducted by professionals who are cognizant of recent legislative and regulatory changes in public and private benefit programs. Use of an updated and user-friendly training manual with a detailed table of contents is highly recommended, because counselors frequently turn to the manual for guidance during counseling sessions. It is questionable whether initial training sessions of less than 20 hours adequately prepare a counselor for his or her varied responsibilities. Programs should anticipate that counselors will not be able to grasp the plethora of information given to them in a single training course. Thus, longer initial trainings and structured refresher trainings-pertaining to issues deemed necessary by staff as well as those requested specifically by the counselors–may be needed to develop and maintain skills.

Commitment to Volunteer Recognition

Because volunteers are the foundation of the programs, it is essential that their efforts be recognized and their concerns addressed. This can deter high volunteer turnover, feelings of dissatisfaction, and lack of appreciation. Several case study States have developed creative ways to demonstrate their appreciation of program volunteers, such as certificates or award luncheons.

Good Record Keeping

Without program statistics, it is difficult to monitor and evaluate programs, both internally and externally. Program efforts and needs may go unnoticed. Staff should communicate the importance of program reporting to counselors, recognizing that reporting of any kind is often viewed as burdensome.

Needs Assessment

A needs assessment–which includes review of program design, emphasis, procedures and spending–should be conducted at regular intervals. Feedback can be sought from State-level staff, regional and local coordinators, sponsoring agencies, area sites, counselors and clients. The assessment should be based upon realistic goals and high quality standards for program growth. Internal monitoring can easily be overlooked, particularly if program responsibilities are delegated or if the program is understaffed.

Increased Outreach

Despite their efforts, the ICA programs only reach a small proportion of the Medicare population. Additional outreach will allow the programs to reach more beneficiaries. One avenue to explore is cable access television–perhaps in partnership with HCFA–since seniors seem to favor this media. As awareness increases and the field of consumer information grows, demand for services may outrun program capacity. Programs will also need to develop ways to address increased demand.

Modify and Expand Program Materials

ICA programs will eventually need to adapt their materials to include information on health plan quality of care ratings (e.g., consumer satisfaction data and technical measures of health plan performance), since the comparative information they currently distribute only reflects benefits and premiums. Programs could also benefit from the development of prototypes materials (e.g., handbooks, videos) that are common to all programs but could easily be made State-specific with minor revisions. Some materials are currently under development through HCFA-sponsored contracts and grants. Adapting them to serve non-English speaking populations will be necessary in some areas of the country.

The ICA programs play a valuable role in the two-way communication process between HCFA and its beneficiaries by providing them with information to facilitate good health care decision making. “Better informed beneficiaries make better payment plan, provider, and treatment choices” (Vladeck, 1996b). Armed with this information, beneficiaries are “our staunchest allies in the fight against fraud, waste, and abuse in the Medicare market,” (Vladeck, 1996b). ICA programs also help identify the key issues that confuse Medicare beneficiaries, allowing HCFA to tailor its activities to those areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Thomas Rice, Ph.D., of the University of California at Los Angeles School of Public Health, and Bonnie Burns, senior health insurance specialist, of Scotts Valley, California, for their consulting expertise provided throughout the course of this research.

This research was supported by Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) under Contract Number 500-92-0013. Lauren A. McCormack and A. James Lee are with Health Economics Research, Inc. Jenny A. Schnaier and Steven A. Garfinkel are with Research Triangle Institute. All views and opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of Health Economics Research, Inc., Research Triangle Institute, or HCFA.

Footnotes

Mississippi did not apply in the first grant year.

“Substantially similar” States were defined by HCFA as those with existing counseling programs whose current scope of activities was comparable to the ICA program as defined within the grant. Substantially similar States were required to maintain existing activities at a pre-ICA level and expand or provide alternative activities with the Federal monies. One State, Maryland, was granted a waiver of the requirements and was permitted to expand its pre-existing program to geographic areas not previously served. Henceforth, we refer to the 15 substantially similar State programs as “pre-existing” programs.

See McCormack et al. (1994) for the full report.

If program utilization data were not available for the entire 12-month reporting period, data were annualized for standard comparisons. Annualizing data may under-or over-report actual performance depending on whether the missing data were from the beginning or the end of the 12-month reporting period, as program activity generally increased over time.

Budget data were proposed in October 1992; therefore actual spending may have differed. However, the information provides an estimate of the funding allocation.

RSVP is a volunteer program funded as a part of ACTION, the Federal Domestic Volunteer Agency.

Between April 1, 1993, and March 31, 1994, a total of 213,709 ICA sessions (some with duplicate individuals) were conducted in the 28 States monitoring program activity in this way.

An exception to this statement is the Wyoming ICA program, which reported no client contact as of April 1, 1994. The delay in implementation was attributed to staff turnover and poor weather that had prevented training conferences from taking place.

Without controlling statistically for other factors, we cannot assume that either age of the program or higher levels of funding are the direct cause of higher program utilization. Another important consideration is that highly populated States received more Federal funding because a population-based formula was used to allocate grants dollars. Thus, State population affects both program funding and utilization. Because small sample sizes were used in these comparisons, they should be interpreted with caution.

In pure economic terms, this is not an actual savings; rather, it is a transfer of money from one entity to another.

The QMB program covers Medicare premiums and cost-sharing for beneficiaries whose income is below the Federal poverty level (FPL). The SLMB program covers Medicare cost-sharing for beneficiaries whose income is between 100 and 120 percent of the FPL.

Some States established their own definitions for counselors to follow, while others left the decision up to individual volunteers, asking them to indicate the reason behind the savings reported. Examples of definitions used were the cost of the annual premium when a duplicative policy was dropped or the difference in annual premiums when a policy was changed. Some programs advised using the monthly premium multiplied by the number of months remaining in the plan year. When the savings involved the processing of a claim or an appeal, the amount of the claim was generally considered to be the savings.

In order to calculate the incremental effect of the Federal grants program, we excluded States that had a pre-existing program, and we included only the Federal dollar investment (1992 basic and coordinated care grants). This approach was chosen because it factors out the impact of pre-existing activities, and it concentrates on the marginal effects of the legislation which created 35 new State programs. Inclusion of the older programs, many of which had existed for several years, would confound evaluation of this new initiative.

Reprint Requests: Lauren A. McCormack, Health Economics Research, Inc., 300 Fifth Avenue. Sixth Floor, Waltham, Massachusetts 02154. E-mail: Imac@her-cher.org.

References

- Etheredge L. Medicare in a Consumer-Choice Environment: Competitor or Residual Program? Washington, DC.: Health Insurance Reform Project, George Washington University; Jan, 1996. Unpublished. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick/Schneiders Inc. Analysis of Focus Groups Concerning Managed Care and Medicare. Washington, DC.: Mar, 1995. Unpublished. Prepared for Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Garnick D, Henricks A, Thorpe K, et al. How Well Do Americans Understand Their Health Care Coverage? Health Affairs. 1993 Fall;12(3):204–212. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs D. Information Needs for Consumer Choice: Final Focus Group Report. Research Triangle Park, NC.: Research Triangle Institute; Oct, 1995. Prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration under Contract Number 500-94-0048. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Hanes P, Merwyn G, Anderson B, et al. Oregon Consumer Storecard Project: Final Report. Rockville, MD.: Sep, 1996. Executive Summary submitted to the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, the University of Washington, and the Oregon Consumer Scorecard Consortium Steering Committee under Contract Number 282-93-0036. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Hart V. Report on the Health Insurance Information, Counseling, and Assistance Grants Program. Washington, DC.: Health Care Financing Administration; May, 1996. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis MS. Consumers' Knowledge About Their Health Insurance Coverage. Health Care Financing Review. 1983 Fall;5(1):65–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall N, Rice T, Sangl J. Consumer Knowledge of Medicare and Supplemental Health Insurance Benefits. Health Services Research. 1986 Feb;20(6):633–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack L, Garfinkel S, Schnaier J, et al. Consumer Information Development and Use. Health Care Financing Review. 1996 Fall;18(1):15–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack LA, Schnaier JA, Lee AJ, et al. Information, Counseling and Assistance Programs: Final Report. Baltimore, MD.: 1994. Prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration under Contract Number 500-92-0013. [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck BC. Mar 1, 1996a. Presentation at the Administration on Aging Conference on “Emerging Trends in Managed Care: Opportunities for the Aging Network.”. [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck BC. Presentation of the Fiscal Year 1997 Budget Request for HCFA Before the Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education House Committee on Appropriations. Washington; Apr 30, 1996b. [Google Scholar]