Abstract

The premise that competition will improve health care assumes that consumers will choose plans that best fit their needs and resources. However, many consumers are frustrated with currently available plan comparison information. We describe results from 22 focus groups in which Medicare beneficiaries, Medicaid enrollees, and privately insured consumers assessed the usefulness of indicators based on consumer survey data and Health Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS)-type measures of quality of care. Considerable education would be required before consumers could interpret report card data to inform plan choices. Policy implications for design and provision of plan information for Medicare beneficiaries and Medicaid enrollees are discussed.

Introduction

For consumers who have had a choice of health plans, comparative plan information has traditionally included only a description of benefits and costs. Over the past few years, many public and private organizations have developed health plan performance measures or “report cards” for use by their constituencies. Although formats vary, report cards typically combine comparative information on plan features and costs with selected quality indicators (QIs). These indicators are based on member satisfaction surveys and/or administrative measures of plan performance, which in turn are derived from data collection efforts such as HEDIS or the Group Health Association of America (GHAA) member survey questionnaire.

Initially, most of these report card efforts were based on what experts or purchasers deemed important. Increasingly, however, studies are examining what is important to consumers and what types of presentations are easiest to use. The overall goal of the report card designers is to influence consumers' actual plan choice—that is, sponsors anticipate that consumers will use this information to make more satisfactory choices among the plans available to them, leading to improved quality and cost containment (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1995; Schnaier et al., 1995). To date, however, there is little empirical evidence of the impact of report card use.

Recent studies concur in their findings that consumers are interested in receiving comparative information on plan characteristics, including data on quality of care (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1995; National Committee on Quality Assurance, 1995). However, consumers may conceptualize quality of care in terms very different from those used by providers and researchers. They are likely, for example, to define quality of care in terms of the provider-patient interaction rather than the clinical processes and outcomes of care (Mechanic, 1989). Consumers may also fail to understand key aspects of the indicators provided (Hibbard and Jewett, 1996).

Our research, part of a study designed to develop prototype materials containing plan choice information, identified what different consumer groups considered important in choice of health plan. It also explored several factors that may limit consumers' acceptance of, understanding of, and willingness to use QIs and other measures (Gibbs, 1995). Based on this research, we present recommendations for development of comparative health plan materials.

Methods

Focus Group Methodology

Data for this study were collected by means of focus groups, which are used increasingly in social science research as a qualitative method of gathering information on peoples' opinions with greater detail and nuance than are available from survey data, and with some economies of both time and resources. A focus group is a discussion led by a trained moderator about a particular topic with approximately 8 to 12 persons (Greenbaum, 1988). The group interaction within focus groups is designed to simulate discussions that might naturally occur around a given topic, with the give-and-take among group members eliciting ideas and reactions that might not have been revealed within an individual interview. Systematic analysis can reveal key “themes” which reflect a synthesis of the opinions expressed across groups and types of individuals for the topic of interest. Focus groups are particularly effective in generating hypotheses to be tested through other research methods (such as case studies or surveys).

Despite all of the advantages of focus groups, those reviewing the results should keep in mind certain potential limitations. First, as with other data collection methods, selection bias is a threat to validity if there is any systematic bias created by either participant recruitment strategies or the type of individual who agrees to participate (if, for example, consumers unhappy with their insurance plans are more likely to attend in hopes of venting their frustrations). Even if focus group participants are recruited randomly, the extent of participation bias is difficult to assess and limits researchers' ability to extrapolate or generalize results to broader populations. The group format means that participation bias may also be a threat if discussions are dominated by persons with certain viewpoints. Moreover, the highly interactive setting increases the possibility of bias if individuals feel inclined to offer what are perceived to be socially desirable responses, or if there is a generalized inhibition about discussing certain topics. Although using skilled and culturally sensitive moderators and conducting multiple focus groups helps mitigate these problems, we reiterate that these caveats should be kept in mind during analysis and interpretation of focus group data.

Because focus groups are so strongly influenced by the dynamics of the group, the “group,” rather than the individuals within the group, is the most appropriate unit of analysis. The small study population that results (in this study, n=22) means that focus group studies are rarely appropriate for identifying differences among subpopulations.

Study Population and Sites

Three insurance populations (Medicare, Medicaid, and privately insured individuals under 55 years of age) were included in the study for a total of 22 focus groups at 8 different locations, as shown in Table 1. Several decisions were made regarding the composition of these groups in order to increase homogeneity within groups and to enhance salience of the topic to participants. Group homogeneity on factors related to the topic decreases the potential for participant bias by increasing the comfort level and willingness of participants to contribute to the discussion. Increasing topic salience makes it more likely that participants will have a stake in the issue being discussed and will offer their ideas and opinions to the process.

Table 1. Focus Group Populations and Sites.

| Insurance Populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Population | Medicare Beneficiaries | Medicaid Enrollees | Privately Insured Participants |

| Total Groups | 10 | 6 | 6 |

| Large/Small City | Minneapolis, MN Albany, OR |

Los Angeles, CA Portland, OR |

Raleigh, NC |

| Small Town | Yucca Valley, CA Virginia, MN |

— | Virginia, MN |

| Chronic Disease | Jacksonville, FL Minneapolis, MN |

Los Angeles, CA Portland, OR |

Raleigh, NC Portland, OR |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | Los Angeles, CA Jacksonville, FL |

Los Angeles, CA (2 Groups) | Los Angeles, CA Jacksonville, FL |

| Pre-Medicare Eligibility (63-64 Years of Age) | Jacksonville, FL Portland, OR |

— | — |

SOURCE: (Gibbs, 1995).

First, we defined a comparable income level across groups (not including Medicaid enrollees). We know from recent groups sponsored by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), as well as from literature in the field, that the health plan choices of lower-income purchasers are largely determined by financial considerations (National Committee on Quality Assurance, 1995). Presumably, those with very high incomes are only slightly constrained by financial considerations. To ensure that participants would be able to consider and discuss financial and nonfinancial considerations, all Medicare beneficiary and privately insured groups were limited to persons within one quartile of the median income for their city or (for rural sites) county.

Second, we limited participation to persons who had had the opportunity to make a choice among plans, either by new enrollment or re-enrollment, within the past 2 years. For privately insured consumers, this meant that participants must have had more than one health plan to choose from through employment or individual purchase. For Medicare beneficiaries, we included only persons who had purchased a Medicare supplement, enrolled in a Medicare HMO, or given serious consideration to changing plans within the past 2 years. For Medicaid enrollees, our groups were held in States where enrollees are formally offered the chance to change their health plan annually, and are able to initiate procedures to change plans at any time.

Third, we increased the likelihood of insurance coverage being a highly salient issue within our privately insured groups by screening to ensure that participants had at least one child living at home and/or had a family member with a chronic physical condition, increasing the likelihood of encounters with the health care system and knowledge of health insurance issues. We defined a chronic condition as one that was expected to last at least 3 months and required at least five visits to a health care provider within a year.

Fourth, we assembled all Medicare beneficiary and privately insured focus groups in sites with moderate managed care penetration, so that participants would be sufficiently familiar with their characteristics to discuss their own considerations involved in assessing managed care plans and deciding between managed care and fee-for-service (FFS) plans. Medicaid enrollee groups were convened in a State where enrollees had a choice between managed care and FFS participation (California) and one where enrollees chose only among managed care plans (Oregon). Both States had mature programs where start-up problems had already been addressed.

Finally, our group configuration, site selection, and recruiting/screening strategies were planned in such a way as to include residents of major metropolitan areas, smaller cities, and small towns in different geographic regions as well as racial and ethnic minorities. In addition, we attempted to represent the needs and preferences of new elderly Medicare beneficiaries by including two groups of persons 63 or 64 years of age at the time the groups met. Except in two instances, each type of population group was interviewed in at least two different geographic sites in an attempt to minimize potential regional bias.

Moderator Guides and Process

Topic guides were developed and tailored to the circumstances of each insurance group. To allow maximum comparability, the guides were made similar across groups. The topic guide served as a framework rather than a script, giving the moderator latitude to use probe questions as needed and to follow lines of inquiry suggested within the discussion.

For all groups, the general areas of discussion were as follows:

Dimensions of health plans—features that are important in choosing a plan;

Decision processes—ways that participants made their most recent choice among health plans;

Comparative information for choice— examination of sample presentations of consumer satisfaction ratings and quality-of-care measures, and discussions of whether these would be useful for selecting a plan;

Assessing likely costs—ways that participants determine which plan offers the best value to themselves and their family (Medicare beneficiary and privately insured groups only);

Credible information sources; and

Problems encountered in using health plans—difficulties participants have encountered and what kinds of information they need to resolve them.

The sample presentations included two measures of quality (satisfaction with technical quality of care and with provider communication), two access measures (satisfaction with access to after-hours care and with waiting time required to make appointments and receive care), one measure of satisfaction with physician choice, and one measure of satisfaction with customer service. HEDIS-type indicators included rates of preventive care utilization (for childhood immunizations, mammography, cervical cancer screening, and cholesterol screening), management of chronic disease (retinal eye exams for diabetics), and tertiary care outcome (liver transplant survival rates).

Moderators with substantive expertise in health care issues, as well as extensive experience in focus group methods, led each of the groups. To assist the moderator, a second team member—also with both substantive and methodological expertise—served in the role of notetaker and logistic support person for each group. With participants' permission, all groups were audiotaped. Each group lasted approximately 1½ to 2 hours.

Analysis

Following transcription of all audiotaped groups, project staff coded text segments by content area, speaker characteristics, and group parameters. We then used a text-oriented database software package (AskSam) to sort coded segments for review, allowing researchers to examine all statements on a given topic (i.e., physician choice) and to compare statements according to participant characteristics (i.e., presence or absence of chronic condition in household). Emerging themes were identified and subjected to further coding and review. Codes were reviewed to check reliability across raters. Quotes in this article from focus group participants have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Findings

Choice Process and Information Needs

In varying degrees, most consumers described the process of choosing a health plan as difficult and frustrating. Specific concerns, as well as the circumstances in which decisions were made, varied considerably both among and within the three insurance groups.

For Medicare beneficiaries, the seriousness of the decision process may be heightened by the awareness of their own or their contemporaries' increasing physical limitations and susceptibility to illness. Some described a decreasing confidence in their own cognitive abilities. Others spoke of feeling poorly equipped to negotiate health plan decisions that had previously been handled by a spouse or employer. Perhaps because the awareness of vulnerability regarding health is well established in this age group, or because our screening criteria for participants with chronic conditions were broad enough to include beneficiaries who might not consider their own health to be poor, we did not discern any identifiable patterns of response within these beneficiary groups. Among pre-Medicare beneficiaries, both concern and understanding regarding impending coverage decisions were fairly low among those who had not yet reached age 64 or had a spouse reach that age.

Beyond the basic health plan features of benefits, premium costs, and amount of paperwork, Medicare beneficiaries were able to identify a number of other plan characteristics of interest. Access to specific providers was mentioned most frequently. Although beneficiaries described provider choice in terms of the ability to see a doctor who knew their health history, their comments made clear that the relationship also represented both an interpersonal bond and established trust in the quality of care provided (“My doctor, he has it in my chart that I get blood tests every so often, and hell call me the next day and let me know the results.”). Although most concerns in this area were related to whether it would be possible to continue seeing the same primary care physician, others mentioned access to specific hospitals or specialists as well.

The context of choice for Medicaid enrollees depends to some extent on the structure of the medical assistance program in their State or local jurisdiction. In the two States in which we held focus groups with Medicaid enrollees (California and Oregon), individuals are formally offered a choice among participating managed care plans at least once a year; California also allows a choice of FFS coverage. Although there is greater standardization among providers in terms of coverage for basic health care services, and more comprehensive coverage of most services than under Medicare or private insurance plans, enrollees in our groups still described considerable concern surrounding their choice of a health care plan. The desire to make the best choice on behalf of one's children, the fact that many enrollees are dependent on public transportation for both routine and urgent care, and the perceived difficulty of changing plans once enrolled all added to the level of concern described by participants.

In fact, convenience of location was the single factor most frequently mentioned (cited slightly more often than provider choice) by enrollees as a consideration in their choice of plans. While enrollees had strong feelings about other aspects of care, their choices often were constrained by transportation needs. Like Medicare beneficiaries, Medicaid enrollees also cited the ability to see the doctor of one's choice as an important factor in the decision. This consideration was particularly strong among participants with chronic diseases. Perhaps because much of their health care utilization involves care for children, these enrollees also described waiting time for both routine and urgent care as an important consideration.

Compared with Medicare beneficiaries and Medicaid enrollees, privately insured consumers typically have fewer health plan choices. The 1993 Employer Health Insurance Survey estimated that nearly one-half of all insured employees have no choice of health plans (Institute of Medicine, 1996). In addition, the decision may be more complex because one or two plans (depending on the number of employed adults) must meet the needs of all family members. Participants with chronic diseases were particularly aware both of their requirements for coverage and of their dependence on choices made by employers. (“It would be beneficial in a lot of ways to choose another plan to meet the rest of the family's needs, but we always have to make sure that my daughter gets what she needs. And so I really feel trapped a lot of times.”).

Although price was generally even more salient for privately insured consumers than for Medicare beneficiaries, choice of physician remained a key concern, even for those without chronic diseases to consider. Privately insured consumers with chronic diseases in their family displayed a far more acute attention to the details of benefits and coverage than was heard either from other privately insured consumers or from Medicaid enrollees and Medicare beneficiaries with chronic diseases. Participants with chronic diseases defined provider choice primarily in terms of access to specialist care. Their choices of primary care providers and of plans were guided by the need to retain access to preferred specialists.

Response to Consumer Ratings

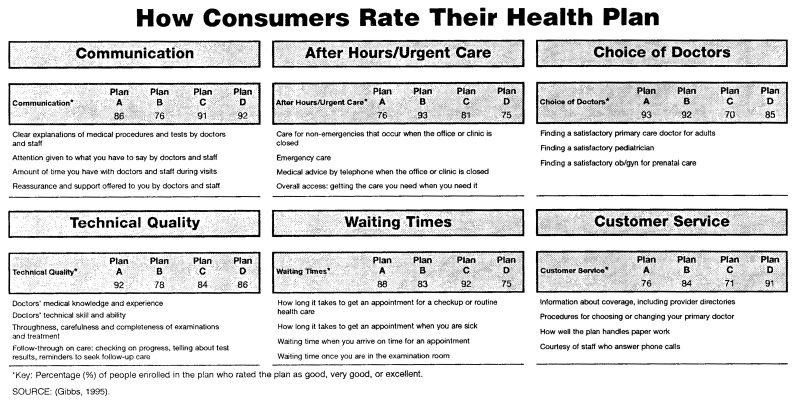

Two samples of consumer ratings were provided to each group, beginning with a simple presentation that showed scores for six major categories (Figure 1). Although reactions to this type of information were generally positive, participants raised several concerns.

Figure 1. Sample Consumer Ratings: Major Category Scores.

Across all groups, and particularly in the Medicaid enrollee group, we found that some participants needed explanations of the basic methodology of a consumer survey—for example, that those who completed the survey would rate only the plan to which they belong, and that a standardized instrument would be used. Other participants wanted detailed information about survey administration, such as how many people completed the survey, who the respondents were, whether the survey was conducted by a neutral party, and even how the questions were worded. Generally, participants felt that consumer feedback would provide useful insights into how plans actually operate. Some participants questioned whether consumers, including themselves, are qualified to assess the quality of medical care they receive. A few participants doubted that other consumers' experience could inform their own decision, feeling that their circumstances and preferences would vary substantially from those of a typical consumer. These concerns generally lessened as participants examined the rating categories and discovered that they could focus on the ratings that were most relevant to their priorities. Reading through individual items generated additional discussion of plan choice issues, suggesting that consumer ratings might be useful in helping consumers to identify which characteristics are important to them.

In several of the Medicaid enrollee groups, participants spontaneously said that they would prefer a chance to hear the opinions of an individual plan member rather than examining aggregated consumer data. In response to probes from the moderator, they agreed that any one person's reactions might present a biased view, and proposed instead that several people be assembled to relate their experiences, either as a panel or video presentation. While agreeing that such spokespersons might not be sincere, they felt more confident of their ability to assess the truthfulness of individuals than to evaluate numerical ratings.

Survey ratings of particular interest corresponded to those mentioned earlier. Medicare beneficiaries tended to focus on physician-related factors such as physician choice, communication, and technical quality. Medicaid enrollees were most interested in communication, technical quality, and the availability of after-hours care. Privately insured consumers looked first at technical quality, waiting time, and customer service. Parents of children with chronic diseases were particularly interested in after-hours care, while adults with chronic conditions gave priority to technical quality, for which they were willing to accept lower scores in other areas. Those who had chosen a plan to maintain a relationship with a specific physician were less interested in ratings of physician choice, but acknowledged that the information might be useful to a new resident.

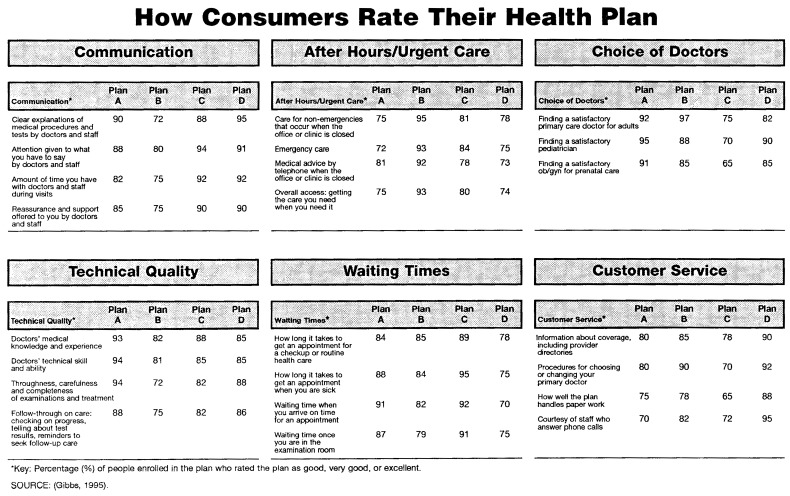

Participants also examined a more detailed presentation of consumer ratings data that provided separate ratings for each component rather than category scores (Figure 2). Among those who said that they would use consumer ratings, participants overwhelmingly preferred the more detailed version, saying, first, that it made it easier to compare plans on items of interest and, second, that what appeared to be a more complex presentation was actually easier to understand. Only one participant expressed concern that friends and relatives might find the detailed presentation too complicated. Subsequent tests of prototype materials suggested, however, that relatively few consumers would actually tolerate the complexity of such a highly detailed presentation.

Figure 2. Sample Consumer Ratings: Seperate Component Scores.

Response to Quality-of-Care Measures

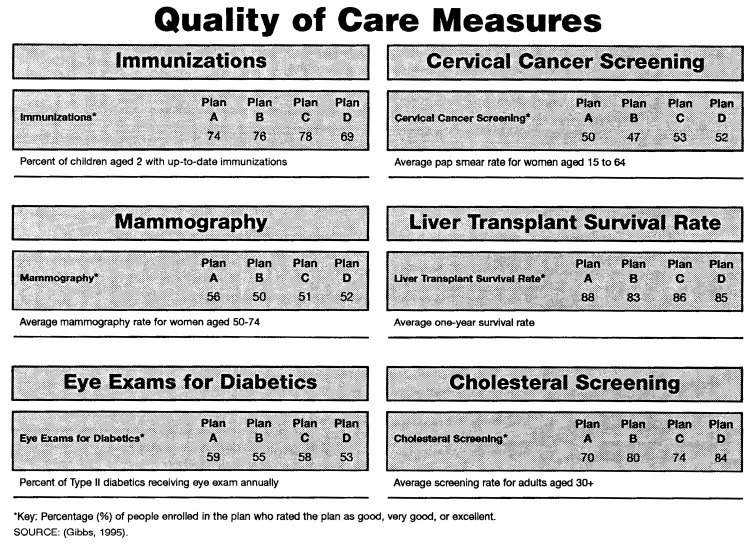

We next asked participants to look at a sample presentation of quality-of-care measures (Figure 3). Reactions to this piece were sharply divided. Across all insurance groups, the majority of participants considered compliance with recommended preventive care measures to be the consumer's responsibility and therefore not reflective of the quality of the plan. Comments such as “this doesn't reflect on the plan; it reflects on the members” and “if you're a good parent, you're going to remember,” were typical. Medicare beneficiaries, in particular, seemed to assume that periodic screenings would be offered by their physician, or that they would receive them if requested. They did not see service monitoring as a plan function. Some comments suggested that patients were unaware that their medical records were likely to be in machine-readable form, and therefore did not imagine that ongoing monitoring and reminders would be feasible (“I can't expect this doctor, that has 3,000 patients, to remember that this is the time of the year for me to have my special physicals.”).

Figure 3. Sample Consumer Ratings: Quality-of-Care Measure Scores.

Although most participants were skeptical of these measures, some saw them as indicators of variations in access to care across plans, or of concern on the part of health plans for their patients' well-being. Others were receptive to this interpretation when it emerged in discussion. In contrast, participants with chronic diseases tended to be highly interested in quality-of-care measures, particularly those related to specialty care such as the number of surgical procedures performed, or survival rates (“Waiting times and customer service are probably going to be really important to people who don't use the services very often. That's what they're going to look at, whereas I probably won't consider those.”)

For ratings of both quality of care and consumer satisfaction, some participants expressed concerns over interpretation of the numerical ratings. Although we attempted to model our sample ratings on existing data, participants questioned both the generally high satisfaction scores (“If it was one answer down around 60%, 50%, 40%, I would rule that out. But if they're all up around 80 or 90%, I probably wouldn't pay a whole lot of attention to it.”) and small variations among plans (“I'd feel better if one was way down there and one way up there. I could choose better”).

Response to Cost Profiles

To explore the potential usefulness of expanding cost information beyond standard comparisons of premiums and copayments, we asked participants whether presentation of average costs per year for “typical” patients, or for patients with various chronic conditions, would help them compare the likely cost of different plans. Participants quickly pointed out that a typical consumer was not likely to exist; however, some were interested in the idea of comparing how costs would be handled under different plans. Many felt that even if cost profiles could not represent their likely experience, they might be useful in illustrating different cost structures and trade-offs between premiums and out-of-pocket costs. Such examples, while not necessarily representing the consumer's likely experience, were seen as useful illustrations of a plan's financial structure.

Participants with chronic diseases were least likely to be interested in this sort of example. They were more likely to have examined their plan's structure and their own future costs in detail, and did not expect that any example could represent their own circumstances. Some had developed fairly elaborate worksheets with which to itemize anticipated utilization of various services and to compare resulting costs under the plans available to them.

Information Sources

Across all groups, participants overwhelmingly preferred impartial information sources, although there were some variations in participants' concepts of who would be the most trustworthy and informed source. Input from trusted friends and relatives was seen as valued and highly credible, and often preferred over published information. Opinions were mixed on whether government agencies were credible, particularly among minority participants. State government and government-sponsored programs, such as senior counseling services, were named spontaneously as examples of trustworthy sources, but the Federal government itself was viewed with caution.

Most, but not all, felt that insurance plan representatives were not likely to be trustworthy as information sources (“[I]f you have somebody from the plan, they're just lining their own wallets.”) and expressed skepticism of information compiled by insurers (“I think a lot of times they pad these kinds of things to make themselves look good.”). This distrust extended to the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), whose materials were suspect because of the organization's involvement in marketing supplemental insurance. The exceptions were those who valued the personal interaction with a plan representative. The magazine Consumer Reports, published by Consumers Union, was frequently cited as a credible and helpful source.

Several Medicaid enrollees extended their distrust of plan representatives to include anyone who had not had the experience of using publicly funded services. As noted before, enrollees expressed an interest in hearing from other enrollees whose perspective was likely to be similar to their own. (“These people that have put these plans together have never had to deal with the services. They can tell you what they intended for it to be, but it doesn't work no way like that.”)

Problems in Using Health Plans

Numerous examples of difficulties encountered in using health plans emerged as illustrative anecdotes throughout the groups. Problems cited most often included denial of payment for emergency room care and long waits for service (Medicaid enrollees), and limited access to specialist care (Medicare beneficiaries and chronically ill participants). Although many participants had been able confront the health plan and resolve the difficulty, they also described feelings of powerlessness, particularly if they expected the problem to continue or recur (“I have to fight for every single thing. I ended up having to pay on my own, just so I could get what I needed. You shouldn't have to do that.”). Participants tended to view these difficulties as isolated problematic interactions with a provider or plan, rather than as infractions of consumer rights with established procedures for resolution. Indeed, few had any concept of their rights as plan members or of the existence of established procedures for resolving concerns.

Discussion

Across all insurance groups, participants expressed a desire for comparative information with which they could evaluate the plans available to them. Whereas their responses to the sample QIs and consumer ratings presented and other measures discussed within the groups were generally favorable, subsequent discussion revealed several general and conceptual barriers that would limit the likelihood that participants would use such indicators and ratings when choosing a health plan.

General Barriers to Comparative Plan Information

The first barrier that communicators must surmount in presenting comparative health plan information to consumers is proving that the source of the information is impartial and credible. Consumers perceive information from health plans as persuasive rather than informative in intent, with an assumed bias associated with the marketing agenda. Their distrust is intensified if plans are believed to have been involved in the data collection process. If consumers perceive that the information is biased, they are unlikely to accept this information.

Besides the key issue of information source, the question of process is also important. Without employing the terminology of health services research, otherwise unsophisticated focus group participants raised concerns regarding sampling method, response rates, and risk adjustment. Before they consider comparative information, consumers want assurance that the data collection process is fair and uniform. If there is no standardization, they are likely to believe that plans may report only positive results or information that makes them look the best.

A third issue for consumers is the interpretation of ratings. Even if questions of statistical significance are not addressed directly, consumers will make their own assessments of how much variation in ratings represents meaningful differences among plans. Participants appropriately questioned how useful ratings would be if scores were as close as those in the examples shown in the focus groups. However, even if ratings are clustered within a fairly narrow range, they may serve to reassure consumers that their choice of a plan at least falls within an acceptable range. This reassurance purpose was indicated by consumers in a recent study conducted by the U.S. General Accounting Office (1995).

Participants were most enthusiastic about indicators that allowed them to identify plans that were clearly outstanding or inferior. While statistical significance of differences among plans is important for policy reasons, it may be a difficult concept for many consumers to understand. That is, with large enough samples, small differences may be statistically significant but may not be of practical significance to a consumer. In its presentation of statewide results of consumer satisfaction with health plans, Minnesota has attempted to explain and distinguish both statistical and practical significance of all the results (Minnesota Health Data Institute, 1996).

Participants' comments also suggested an additional interpretation issue not directly addressed in the focus groups: benchmarking. There is not yet an adequate base of comparable consumer satisfaction data to provide a context for assessing plans, nor agreement on nationally accepted clinical standards for quality-of-care measures. In the absence of independent benchmarks, plans can only be compared with each other. If all plans in an area are low on a given indicator, e.g., mammography screening, consumers may misinterpret ratings as being in the acceptable range because they do not have a proper comparison. In its report card, Kaiser Permanente, Northern California Region (1993) has provided national comparison standards to help consumers interpret results. However, there are no benchmark data available for many common screenings.

Barriers to Quality-of-Care Indicators

It is well accepted that plan comparison materials should define, in non-technical language, the medical events and outcomes represented by QIs (Schnaier et al., 1995). However, focus group discussions revealed more subtle comprehension difficulties encountered when consumers do not infer the expected causal connection between indicators and health outcomes. For example, variations among plans in rates of primary care utilization or low birth weight were interpreted as reflecting differences in member population rather than differences among the plans themselves. Although population variations may in fact influence the indicators, they are of course intended to primarily reflect differences in the care process. In addition, some indicators intended to be positive were interpreted as negative. For instance, Medicare beneficiaries wondered whether a plan with a lower rate of hospitalizations for pneumonia was under-treating patients who should have been hospitalized. They perceived low rates as signals that they might encounter barriers to needed inpatient care. Without explicit examples of the ways in which an indicator represents good practice, consumers may be unable to draw conclusions, or may draw conclusions quite different from those intended, from such QIs.

Another barrier is a lack of understanding as to how a health plan might influence member behavior. Measures of preventive care utilization were widely dismissed by participants, on the grounds that obtaining these services is the responsibility of the patient. Medicaid enrollees were adamant in their belief that individuals should be held responsible for complying with recommended screenings, and parents for keeping their children's immunizations up to date. Medicare beneficiaries typically expressed bewilderment that anyone would fail to take advantage of covered preventive services.

Only a few participants interpreted these indicators by suggesting ways in which plans might facilitate utilization of preventive care; these were often participants who had experienced such efforts from a current or previous plan. When presented with examples, such as postcards reminding parents of recommended immunizations, or reminding patients to schedule periodic screenings, there was some acknowledgment that these could be helpful. The desirability of such efforts did not, however, extend to a willingness to base health plan choice on these indicators.

Although the degree to which health plans modify physician behavior depends to some extent on the plan model, few participants recognized the potential for plans to influence indicators which they saw as reflecting the quality of physician care. At the most basic level, some comments showed that participants could not imagine a technology by which plans could monitor utilization in order to encourage preventive care.

More generally, responsibility for the process of care was almost exclusively attributed to the individual physician. Anecdotes describing attentive and effective care were repeatedly offered as evidence in support of a participant's determination to maintain a relationship with that physician. Such experience is unlikely to be outweighed by QIs presented by other plans. The ways in which a health plan might facilitate satisfactory care, such as allowing adequate time for appointments, communicating expectations for quality care, and recruiting and rewarding physicians who provide such care, are opaque to patients. However, negative experiences were frequently seen as reflective of the plan, particularly if more than one physician was involved. Similarly, difficulties in accessing care were likely to be blamed on the plan, while ready access was often attributed to the physician's willingness to extend him or herself on behalf of the patient.

Finally, participants typically selected and discarded QIs based upon their specific needs, rather than inferring the more generalized pattern of care such indicators are meant to represent. Participants dismissed immunization rates if their children were older than 6 years, or cancer-related indicators if “cancer doesn't run in my family,” rather than seeing these as indicative of performance in preventive care for children and adults. Similarly, participants who requested indicators other than those shown most often wanted measures specific to their own current and anticipated needs.

Barriers to Consumer Satisfaction Measures

Many consumers found consumer satisfaction measures more intuitively meaningful than the quality-of-care indicators, but also had a number of questions about them. Varying levels of familiarity with survey methodology were apparent, with some participants requiring explanation of the basic concepts of an independent survey and others raising fairly sophisticated concerns regarding survey design and administration. These included issues which are similarly of concern to experts, such as sampling, risk adjustment, and response rates. In laymen's terms, these sampling concerns were expressed in questions such as: “Did they ask people like me?” Several participants with chronic diseases wanted to see ratings based on the responses of others with similar conditions. Many understood that plans could have very different mixes of patients and that adjustments for health status composition would be needed for appropriate comparisons. Also, they were concerned that persons responding may not have used health care extensively or had different or less serious health problems or conditions. Other studies have indicated that surveying only current plan members may overstate satisfaction because those most dissatisfied may have disenrolled (Gold and Wooldridge, 1995).

Although consumers find these consumer satisfaction measures understandable, some consider them to be too subjective. Other studies have found consumers want more objective measures, e.g., average waiting times rather than a perception of length of waiting times (National Committee on Quality Assurance, 1995). They also tend to question other consumers' recall of events and to focus on the possibility of individual variations in tastes or preferences.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate a clear desire of consumers across all insurance groups for access to comparative information that will help them optimize their choice among the health plans available to them. As noted earlier, the methodological limitations of focus group research require caution in either generalizing their results to larger populations or extrapolating from the group's somewhat artificial setting to actual implementation. We suspect, for example, that relatively few consumers would actually be willing to use the highly detailed presentations that focus group participants said they preferred. However, data from these groups can be, and have been, used to guide the development of plan comparison materials for further testing.

With respect to content, there were clear patterns within groups as to areas of interest. Current Medicare beneficiaries wanted more information on the choice between Medicare HMOs and supplemental insurance, and guidance in choosing among managed care plans. They wanted to know whether they would continue to have access to their current provider and to specialist care, and how much protection against financial risk the plan would offer. Those approaching Medicare eligibility needed basic information about the Medicare program and about options for supplementing their Medicare coverage. Medicaid enrollees needed detailed information with which to choose among managed care plans offered by their State or local program. They wanted to know whether they would be treated with respect and be able to access medical care when they needed it. Privately insured consumers were concerned with finding a plan that met their needs and resources and offered quality care. Across all groups, participants wanted to know whether they could continue using providers with whom they had established relationships.

However, our findings demonstrate that quality-of-care indicators and consumer satisfaction measures must be carefully chosen and presented if they are to communicate meaningful information about the process and outcomes of care at different plans to consumers. Lacking comparative information that is meaningful and relevant to their specific needs, consumers will continue to make decisions based on cost, convenience, and continued access to their current physicians. Indeed, the fierce attachment to current physicians expressed by many focus group participants suggests that this relationship serves as an intuitive proxy for quality of care. Having had a favorable care experience, the consumer feels assured of receiving good care in the future if, and only if, access to this physician can be continued. Other plans, if offering attractive combinations of costs and benefits but lacking this assurance of quality care, are unlikely to be considered.

The concerns expressed within the focus groups demonstrate that careful presentation is essential if indicator data are to be understood and used. Basic explanations of what these measures represent and how they are compiled will be necessary. The relationship between QIs and the processes and outcomes of care needs to be made explicit. Although use of nontechnical terminology is a good starting point, most audiences will also require explanations of why an indicator represents a desirable or undesirable event, and examples of how to interpret relative scores. The interest expressed by Medicaid enrollees in hearing the experience of individuals rather than relying on data suggests that first-person quotes could be effectively used to frame indicator presentations for consumers who are less quantitatively oriented. In addition, report cards should assist users in interpreting the relationship between indicators and plan policy and practices. Without examples to clarify the plan's role in shaping care delivery, consumers are likely to attribute events exclusively to physicians and/or patients. Hibbard and Jewett (1995) suggest that consumers need education about this relationship between their health plan and their care within the context of the shift to managed health care from FFS and the attendant change in health care delivery philosophies.

The indicators presented should always be customized to the health priorities of the insurance group. For example, seniors saw indicators such as cholesterol screening and mammography rates as being particularly relevant to their care, while families with young children would be more interested in prenatal care indicators, immunization rates, and asthma inpatient admission rates. To take this issue of saliency into account for different populations, Medicaid HEDIS measures were developed and disseminated in February 1996 for States to use, if they choose. HEDIS 3.0, the current version, includes indicators relevant to Medicare and Medicaid populations in addition to privately insured groups. More development is needed in terms of the outcome measures that are most important to consumers. Hibbard and Jewett (1996) have shown that when it actually comes to choosing a health plan, consumers tend to use outcome measures for undesirable and low-control events (e.g., post-surgical complications) instead of other types of indicators. The U.S. General Accounting Office (1995) indicated similar consumer preferences for outcomes measures.

Descriptions of methodology should provide evidence of impartiality and validity. Some, although not all, consumers will also want to know details of the administration of the consumer survey, such as sample size and selection methods, response rate, who administered the instrument, and who analyzed or audited the results. This information would reassure consumers about the impartiality and accuracy of the comparative data.

Since consumers' interest in documentation varies even within insurance groups, this information would ideally be presented in a “layered” fashion, structured to allow users to choose their desired level of simplicity or detail. Basic definitions would be presented in the body of the report card, with more detailed explanations readily available for those who are interested. For example, the first level could provide basic comparisons of benefit provisions and an overall consumer satisfaction score, although our findings suggest that overall scores may not be acceptable to consumers who see their preferences as sharply distinct from those of consumers in general. A second level could include consumer satisfaction scores for several summary areas, and selected quality-of-care measures together with additional plan information. A final level would include detailed consumer ratings and plan information. A glossary of terms would be a helpful addition as well.

For privately insured consumers, the preferred source for plan comparison information would ideally be a consumer-oriented organization that can provide detailed information on the plans likely to be available within a given market, such as the Pacific Business Group on Health or Cleveland Health Quality Choice (Schnaier et al., 1995). Starting in 1997, HCFA will require all Medicare managed care plans to report relevant quality-of-care indicators and data will be subject to HCFA audit. All plans also will be required to participate in an independently administered survey concerning member satisfaction with the plan and experience with care. State Medicaid programs are similarly contemplating their own role for beneficiaries in Medicaid managed care plans, and in 1995 Minnesota completed its first statewide consumer satisfaction survey of health plans, including Medicaid and Medicare. In work that will potentially benefit all insurance populations, AHCPR is sponsoring the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS), which will develop a family of surveys that can be uniformly administered across a variety of populations and health care delivery systems in order to provide information on consumers' assessments of their health plans.

Presentations of cost information were not tested in this study. Our findings indicate that some current Medicare beneficiaries, and many who are approaching Medicare eligibility, are understandably confused by the financial structure of their coverage. Given the complexity of Medicare reimbursement in combination with various FFS and managed care plan provisions, presentations of simple cost examples may be useful as illustrations of what kinds of costs would be experienced by the beneficiary in each type of plan. Because beneficiaries are justifiably skeptical of whether any “typical” consumer could represent their experiences, these scenarios should be clearly framed as sample scenarios rather than as attempted representations of their own likely costs. Additional development of alternative cost profiles and evaluation of their value to consumers is needed.

Privately insured consumers have an acute interest in the financial implications of different health plan choices. As mentioned previously, several participants, most often those with chronic diseases in their families, described methods they had developed to project their family's likely costs under different plans. A simple worksheet could be developed to guide others through this same process. Some consumers would be interested in using a more sophisticated, computer-based model. Such cost worksheets or profiles would require additional testing.

Another useful addition to informational materials, although outside the scope of this study, would be a description of consumer rights and resources for addressing disputes over issues such as denial of coverage for services or access to specialist care. Although focus group participants demonstrated an acute sense of having been wronged in some interactions with the plan, they lacked the information needed to assess either their rights as consumers or the health plan's justifiable limits on services and providers. Increasing consumers' awareness of what they should expect from plans and how they should proceed if their rights are not respected would empower consumers to deal more effectively with their current plan and, over time, influence the health care environment as they seek out more responsive plans.

The barriers to indicator use revealed by participants' reactions to these sample materials, which were comparable to indicators in current use, underscore the necessity of formative evaluation and pretesting of comparative health plan materials with their intended audiences. As improved materials are developed, designers will need to evaluate whether and how consumers actually use these new types of information to choose their health plans. Consistent with the findings of this research, consumer reports being developed within the CAHPS project have emphasized reporting on multiple dimensions of consumer experience rather than an overall satisfaction measure, and layering of information. The CAHPS evaluation will include both process and outcome evaluations of how the comparative information being developed within the study is used by consumers and benefit managers and whether plan choice is improved through use of the materials. Given that development and dissemination of these “report cards” require substantial resources, it is essential to determine whether they will have the intended effect and are sufficiently useful to warrant their cost.

Footnotes

The research reported in this article was supported by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) under Contract Number 500-94-0048. Deborah A. Gibbs and Barri Burrus are with the Research Triangle Institute (RTI). Judith A. Sangl is with the Office of Research and Demonstrations, HCFA. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of RTI or HCFA.

Reprint Requests: Deborah Gibbs, M.S.P.H, Research Triangle Institute, Health and Social Policy Division, P.O. Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709.

References

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Consumer Survey Information in a Reforming Health Care System. Rockville, MD.: Aug, 1995. AHCPR Pub. No. 95-0083. Summary of a conference sponsored by AHCPR and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 28-29, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DA. Information Needs for Consumer Choice: Final Focus Group Report. Baltimore, MD.: Oct, 1995. Prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration under Contract No. 500-94-0048. [Google Scholar]

- Gold MA, Wooldridge J. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Conference Survey Information in a Reforming Health Care System. Rockville, MD.: Aug, 1995. Plan-Based Surveys of Satisfaction With Access and Quality of Care: Review and Critique; pp. 75–110. AHCPR Pub. No. 95-0083. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum T. The Practical Handbook and Guide to Focus Group Research. Lexington, MA.: Lexington Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. Using Report Cards to Inform and Empower: Consumer Understanding of Quality-of-Care Information. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; San Diego, CA.. October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. What Type of Quality Information Do Consumers Want in a Health Care Report Card? Medical Research and Review. 1996 Mar;53(1):28–47. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the Medicare Market: Adding Choice and Protections. Washington, DC.: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente, Northern California Region: Quality Report Card. Unpublished. 1993.

- Mechanic D. Commentary: Consumer Choice Among Health Insurance Options. Health Affairs. 1989 Spring;:139–148. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.8.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Health Data Institute. 1995 Consumer Survey: Summary Report of Health Plan Category Comparisons. Minneapolis, MN.: Jan, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- National Committee on Quality Assurance. NCQA Consumer Information Project: Focus Group Report. Washington, DC.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaier JA, Garfinkel SA, Gibbs DA, et al. Information Needs for Consumer Choice: Case Study Report. Baltimore, MD.: Dec, 1995. Prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration under Contract No. 500-94-0048. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. Health Care: Employers and Individual Consumers Want Additional Information on Quality. Washington, DC.: 1995. Pub. No. GAO/HEHS-95-201. [Google Scholar]