Abstract

For the past 45 years Germany has had two health care systems: one in the former Federal Republic of Germany and one in the former German Democratic Republic. The system in the Federal Republic was undergoing some important reforms when German reunification took place in October 1990. Now the system in eastern Germany is undergoing a major transformation to bring it more into line with that in western Germany.

Introduction

For the past 45 years Germany has had two health care systems: one in western Germany, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) before the unification of Germany, and the other in eastern Germany, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), before the unification of Germany. In the case of western Germany, there were no profound structural changes to its health care system since the foundations of the system were laid by Bismarck in 1883. However, there was much growth in, and adaptation to, the system during its long history, including some significant reforms in the late 1970s and in the 1980s.

In contrast, after World War II eastern Germany was given publicly financed and provided services quite unlike those in western Germany (Light, 1985). Following the reunification of Germany in October 1990, health service financing and delivery arrangements in eastern Germany are once more being radically reformed to bring them back toward the arrangements that have prevailed throughout in western Germany.

This article contains:

A description of the health care system in western Germany together with some brief references to that in the former GDR.

An account of recent reforms to the system in the two parts of Germany.

Some evidence about the performance of the systems in the two parts of Germany.

An attempt to identify some remaining problems and their potential solutions.

The German systems of health care

Western Germany

Citizens in western Germany enjoy access to a generous range and volume of health services, provided by a mixture of independent and public providers. Access is unhampered by significant direct charges. About 88 percent of the population is covered by social health insurance, funded mainly by payroll taxes. Most of the rest of the population—mainly higher income earners—have private health insurance. The bulk of expenditure decisions are settled between the statutory sickness funds and the providers. Here, arrangements are both highly decentralized and highly formalized. There are about 1,100 autonomous sickness funds. Regional associations of these funds bargain with regional associations of doctors to determine aggregate payments to ambulatory care physicians. In the case of hospitals, representatives of sickness funds negotiate with individual hospitals on rates of payment for hospitals. These negotiations take place under guidelines for rates of increase of health expenditure set by a national committee (Concerted Action). Germany has a federal system of government, and the regulation of health services is diffused between the Federal, State, and local levels.

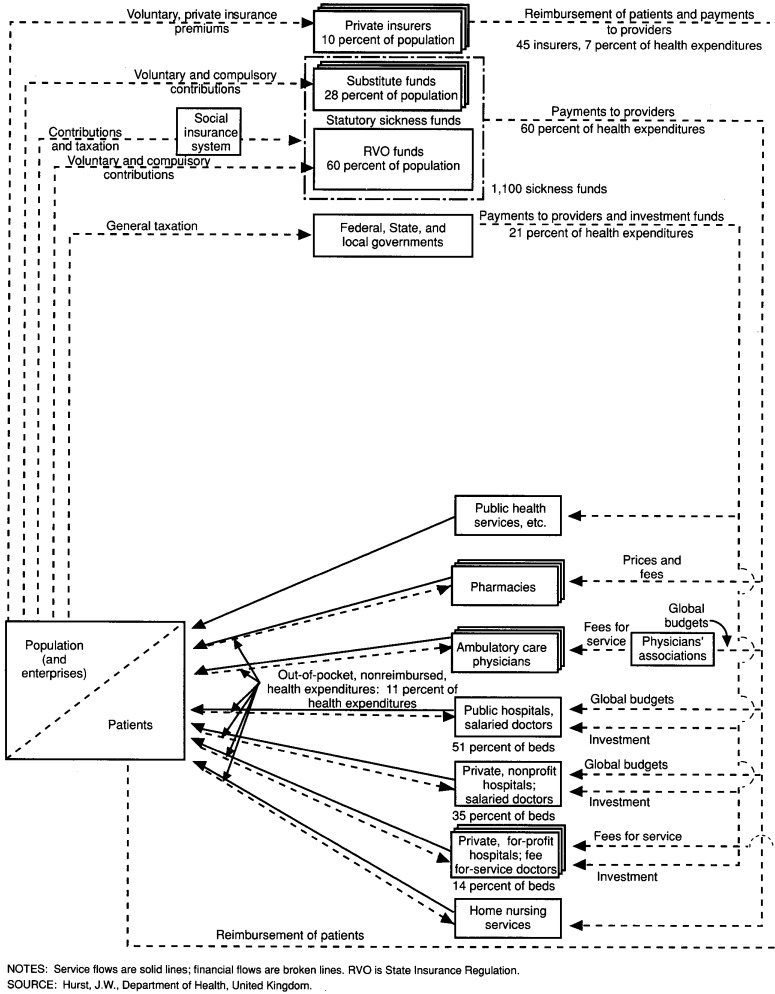

Some of the main features of this system can be summarized in the form of diagrams. Figure 1 shows some of the main relationships in a highly simplified form. At the bottom left in the diagram is the population, some of whom become patients during any 1 year. At the bottom right in the diagram are the providers who supply health services to patients. At the top of the diagram are the third-party payers who collect contributions, premiums, or taxes from the population and pay providers or reimburse patients for services delivered to patients. Service flows are shown as solid lines and financial flows are shown as broken lines.

Figure 1. System of health care in western Germany: Mid-1980s.

Practically the whole of the population is covered by health insurance. The statutory sickness funds, which cover about 88 percent of the population, pay providers directly for the services supplied to their members. The sickness funds can be separated into State Insurance Regulation (RVO) funds, covering about 60 percent of the population, and substitute funds covering about 28 percent of the population. The insured generally have no choice between the RVO funds (they are compulsory members of a particular fund), so the RVO funds are shown as single. The private insurers, which cover about 10 percent of the population, provide indemnity payments both in the form of cash reimbursements and in the form of payments to providers. The substitute funds and the private insurers are shown as multiple because there is a certain amount of competition within (and, indeed, between) these segments of the market. The Federal, State and local governments are included among the funders because of their role in financing public health services and hospital investment.

In terms of sources of funds, about 60 percent of health expenditure is derived from compulsory and voluntary contributions to statutory health insurance, about 21 percent is derived from general taxation, about 7 percent is derived from private insurance, and about 11 percent is represented by unreimbursed, out-of-pocket expenditure.

The providers include public health services, pharmacists, physicians in independent practice, public hospitals, private nonprofit hospitals, private for-profit hospitals, and home nursing services. The pharmacists, ambulatory care doctors, and private for-profit hospitals are shown as multiple as there is usually some competition within these services. Certain other providers such as dentists have been omitted. Sickness funds pay providers by a mixture of global budgets and fee-for-service payments. The bulk of hospital investment in both public and private hospitals is financed by State governments.

Eastern Germany

Figure 2 depicts, in contrast, some key features of the health care system of the former GDR in 1989. Prior to reunification, eastern Germany had centralized, integrated, publicly financed and provided health services. The great bulk of pharmaceutical, ambulatory medical care, and hospital services were organized under the State and were provided free of charge to patients. There was emphasis on ambulatory health centers (or polyclinics) and on occupational health services. Services were funded by a mixture of payroll taxes and general taxes. Although patients could choose their doctor, the doctors themselves were salaried and were very much under the thumb of the State. There was only a very small private sector.

Figure 2. Key relationships in the health care system of the former German Democratic Republic: Late 1980s.

Patient and provider relationships in western Germany

Most patients can turn to health services in western Germany knowing that they are amply covered for comprehensive, high quality care, including preventive services, family planning, maternity care, prescription drugs, ambulatory medical care, dental care, transport, hospital inpatient care, home nursing services, rehabilitation services including cures at spas, and income support during sickness absence. Public health services and psychiatric services, however, are said to be weak. Nursing homes and homes for the elderly are provided outside the statutory health insurance system by local authorities and voluntary bodies. They are financed mainly by private expenditure, often supported by social assistance.

Patients enjoy free choice of either a general practitioner or specialist in independent practice. Access to a hospital is controlled by ambulatory care doctors, and sickness fund patients normally have to go to the nearest hospital that has suitable facilities. However, private patients and determined sickness fund patients can be referred outside the area. There is a sharp division between ambulatory care and hospital care in western Germany. For the most part, hospitals do not offer outpatient care, and for the most part, ambulatory care doctors do not have access to hospital practice. This system is said to lead to lengthy referral chains, duplication of equipment, and repetition of diagnostic tests by different doctors. Ambulatory care practices are very well-equipped and have ample access to the most advanced diagnostic services. There is a predominance of independent doctors in single practice, although partnerships, usually of two doctors in the same specialty, are growing in number.

Patients in western Germany pay only minor direct charges for health services under the statutory insurance system. For example, in 1988 there were prescription charges of 2 Deutsch marks (DM) per person, hospital charges of 5 DM per day for the first 14 days in a hospital, and charges of 5 DM for nonemergency patient transport. However, these charges were subject to ceilings on total payments and to exemptions, mainly for children and for people with low incomes. Of course, full payments are required for over-the-counter medicines and for private medical care, including private rooms in public hospitals. The fees that doctors receive for private patients are higher than those they receive for sickness fund patients, and it is said that there is some corresponding discrimination in the style of service received by the two types of patients (Ade and Henke, 1990). According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the public share of ambulatory care billing was 92 percent in 1987, and the public share of inpatient care billing was 98 percent.

Population and third party relationships in western Germany

About 88 percent of western Germans are covered by the statutory health insurance scheme which was founded by Bismarck. About two-fifths of these individuals are the dependents of subscribers. About 10 percent of the population is fully covered by private insurance—these are mainly civil servants, the self-employed, and high-income earners. Most of the remaining 2 percent of the population, including the armed forces, the police, and some individuals on social welfare, receive free health services. Less than one-half percent of the population has no health insurance; the people concerned are exclusively well-to-do.

Membership of sickness funds is split about 85/15 between compulsory and voluntary members. Membership is compulsory for workers with income below a certain threshold (which was set at 54,900 DM in 1989), for State pensioners, for persons in certain occupations, and for certain other persons with modest economic status. Employees with income above the statutory threshold can join the statutory scheme voluntarily as an alternative to private insurance. A majority of those who can insure voluntarily choose a sickness fund in preference to a private insurer because the premiums are usually lower for married couples and families and for older and high-risk workers who have not previously had private insurance. There is, consequently, risk selection towards sickness funds.

The statutory scheme is administered by about 1,100 autonomous sickness funds, which are usually controlled by representatives of employers and employees. There are two main types of funds: State Insurance Regulation funds (RVO-kassen); and substitute funds (Ersatzkassen). The former cater to both blue- and white-collar workers. Some are organized on a local basis, some on an occupational basis, and some on an enterprise basis. The latter, which already existed as mutual aid societies when the State scheme was set up, cater mainly to white-collar workers and, because of a certain amount of risk selection, are in a strong position to compete for voluntary members. About one-half of all members—mainly white-collar workers—can choose their sickness fund. The biggest group of funds are the RVO-kassen organized on a local basis (Ortskrankenkassen). These funds cater mainly to blue-collar workers and are also obliged to act as a safety net for disadvantaged individuals who do not belong to any group of employees (Eichhorn, 1984).

The sickness funds are required by law to offer a certain list of benefits which has become more generous over time. They are also able to offer additional, optional benefits. The bulk of contributions are made in the form of income-related employers' and employees' contributions (shared 50/50) payable on earnings up to a ceiling. Contributions for State pensioners, the unemployed, and the disabled are made from social security funds, but in the case of the pensioners, these contributions cover only about one-half of the cost of benefits. The extra costs are born by employers and employees and there are cross subsidies at a Federal level between funds to allow for differences in the proportion of retired members. Funds are free to determine their own contribution rates within a guideline laid down by law (recently 12 percent). However, the guideline may be surpassed if a majority of the representatives of the employers and the insured vote for a higher rate. Premiums averaged 12.9 percent of gross income in 1988, but because of different risk structures, ranged widely from 8 to 16 percent of income between different funds, with the funds organized on a local basis having the highest average rates. There is considerable competition between the funds for voluntary members. The funds compete more by offering higher optional benefits rather than by lowering premiums.

Private insurance is supplied by about 45 mainly nonprofit insurers. As was indicated previously, about 10 percent of western Germans are fully insured privately. The benefits have to be at least as generous as the minimum list covered by the statutory scheme. A smaller percentage of Germans take out additional private insurance to supplement the statutory scheme. Deductibles and coinsurance are of increasing importance. The private insurers have agreed collectively to be regulated by a Federal Insurance Office in setting premiums. Premiums on entry depend on: age, sex, risk, numbers of dependents, and cost sharing. They are low for a 20-year-old and high for a 50-year-old. Subsequently, premiums do not vary for age or risk but they can vary for the last two factors mentioned previously and for rising medical care costs. This system embodies a form of saving and discourages individuals from changing insurer. There is some tax relief on health insurance premiums but this is subject to a ceiling which means, in effect, that marginal additions to premiums are usually financed out of taxed income. Private insurers, unlike sickness funds, provide benefits in the form of reimbursement where physicians' bills are concerned but they usually pay hospital per diems directly to the hospital.

Third party and provider relationships in western Germany

The relationship between the sickness funds and physicians in independent practice is highly formalized in western Germany. Physicians are, by law, organized into regional and State associations which assume the duty of making ambulatory medical care available to sickness fund patients and which have considerable power over individual physicians. These are quite separate from doctors' trade unions. All qualified doctors have the right to be admitted to sickness insurance service and once they are admitted they must join the physicians' association. The physicians' associations bargain with the sickness funds' associations at a sub-State level on the rate of payment for serving sickness fund patients. They do so in light of a recommended ceiling on the rate of growth of expenditure on ambulatory physicians' services set by the Concerted Action Committee. The ceiling is set with a view to keeping the contribution rates of insured members constant. When a local agreement is struck, the sickness funds agree, in effect, to pay a prospective lump sum to the physicians' association. The physicians' association itself distributes this sum to individual doctors on the basis of each doctor's workload and according to a fee schedule. Also, the physicians' association itself monitors the quality and volume of services of each physician and, if necessary, applies collective discipline. This system resembles bilateral monopoly at the level of negotiation on the lump sum, although neither the association of sickness funds nor the association of doctors has control over volume. Volume is decided mainly between patients and individual doctors in a situation where neither has any financial incentive to economize. At the level of the individual doctor there is competition for volume and income. If one doctor generates, say, 10 percent more services, his or her income can rise by 10 percent. However, if all doctors work 10 percent harder, fees per item of service must fall by 10 percent to keep aggregate expenditure within the agreed total. As a result, each doctor's income will remain unchanged. Similarly, if the number of doctors rises by 10 percent and the volume of services per doctor remains unchanged, each doctor's income will fall by 10 percent (Brenner, 1989). Recently, the lump sum has been divided into blocks to prevent, say, diagnostic services from taking money from direct patient care (Ade and Henke, 1990).

The fee schedule used by the physicians' association is made up of about 2,500 items of service, a relative-points value scale (negotiated nationally and revised infrequently), and a monetary value per point. For example, a telephone conversation with a patient has 80 points, a home visit has 360 points, and X-rays have from 360 to 900 points. The monetary values tend to vary locally and are traditionally higher for the substitute funds than for the RVO funds. They will also move inversely with the number of points billed according to the process previously described. There is a separate statutory fee schedule for private patients which uses the same relative-points value scale. Here, the fees are about twice the level of those paid by the State funds. Extra billing of private patients (only) is permitted, so long as the relative-value scale is used, but it is rare.

Until very recently, there has been relatively little control over expenditure on pharmaceuticals. The wholesale prices of drugs has been set unilaterally by the pharmaceutical manufacturers, and prescribing has been decided by doctors in the absence of incentives to be economical. There has been only modest cost sharing by patients. Consequently, there has been only weak price competition. However, there has been a negative list, government-inspired publication of prices for comparable drugs, encouragement of generic prescribing, and control of pharmacists' margins.

An interesting variant of these arrangements was the Bavarian Contract struck between the sickness funds and the physicians' association in Bavaria in 1979. This allowed for physicians' remuneration in aggregate to rise faster than the negotiated rate, provided that savings could be demonstrated in other areas of expenditure under the influence of physicians, such as drug prescribing and hospital referrals. (Some evidence on the effects of this contract is presented later.)

There are three main types of hospitals in western Germany: public hospitals, which may be owned by Federal, State, or local governments and which account for 51 percent of beds; private voluntary hospitals, often owned by religious organizations, which account for 35 percent of beds; and private proprietary hospitals, often owned by doctors, which account for 14 percent of beds. The first two types of hospitals usually have salaried doctors and are paid a per diem by the sickness funds which is inclusive of doctors' remuneration. However, the physicians in charge of clinical departments in public hospitals can take private patients. Proprietary hospitals work with doctors who are paid by fee for service and they are paid per diems by the sickness funds which are exclusive of doctors' remuneration. Private patients are charged according to the statutory fee schedule for private patients mentioned previously, and usually the doctor must pay some of the fees to the hospital. As has been indicated, hospital doctors seldom see patients on an outpatient basis, and ambulatory care doctors seldom have admitting rights.

Payments to hospitals are made on a dual basis with operating costs coming mainly from the sickness funds and private insurers, and investment expenditure, even in private hospitals, coming mainly from State governments. Sickness funds are obliged by law to meet hospitals' historical operating costs, but at the same time hospitals are obliged to be economical. Since 1986, payments for operating costs have been governed mainly by prospective global budgets negotiated locally by representatives of the sickness funds and individual hospitals. Once again, these negotiations resemble bilateral monopoly. The negotiations are based on a detailed review of operating costs, including physicians' salaries and depreciation, and an expected occupancy rate. They may also be influenced by comparisons with other, efficient hospitals. They are directed at setting an average daily rate to be used by sickness funds for paying hospitals for each patient day consumed by their members. Charges for private patients are higher, but are based on this. Under the global budget, if the actual bed days exceed the expected bed days during the year, hospitals receive only 25 percent of the daily rate for the extra bed days. If the actual bed days fall short of the expected bed days the hospital still receives 75 percent of the daily rate for the missing bed days. These figures are based on an assumed level for fixed and variable costs during the year. Hospitals can carry over surpluses into subsequent years and must carry losses. If the two parties to the negotiations cannot agree on a prospective budget, the matter is referred to arbitration by a neutral, nongovernment, price office (Altenstetter, 1987).

There are, however, payments for some high-cost procedures, such as organ transplants, on a cost-per-case basis outside the budget. It is intended to extend these to more than 100 procedures with a view to: improving the internal transparency of costs; aiding external comparisons; and helping to ensure that payments reflect case mix.

Since 1986, all investments in hospitals accredited under the plans of the State governments have become the exclusive responsibility of the States. Private hospitals, including proprietary hospitals, may be included in the plans. Finance is in the form of grants and is written off as soon as the investment is made. In addition, there is still some private investment in proprietary hospitals and this attracts the usual debt charges.

Cost containment for privately financed health services depends mainly on cost sharing by the patients, on bonuses for low claims, and by the fact that providers' fees are generally linked to the rates negotiated between the sickness funds and the providers under statutory arrangements. There is little direct negotiation between private insurers and providers and little utilization review.

Quality assurance is becoming an important activity in western Germany. A confidential inquiry into perinatal deaths and complications was initiated in Bavaria in 1980 with favorable effects and has since been extended throughout western Germany. A similar confidential inquiry into deaths and complications has been established for certain tracer conditions in surgery. Recently, quality assurance was made a statutory requirement for hospitals and the subject of negotiation between sickness funds and the physicians' associations. The law specifies that it should be done but not how it should be done. At present, there are no plans to publish information on comparative death and complication rates by hospital. The view seems to be that true comparisons would be technically difficult, and that publication would create disincentives for physicians to cooperate in exploring accidents and mistakes.

Public health services are provided mainly by local government. They include control of infectious diseases, health education, mother and baby care, and school health services. They are financed by all levels of government. They are seen as something of a poor relation in the western German health care system (Eichorn, 1984).

Government regulation in western Germany

The involvement of government in the western German health system has at least three distinct characteristics:

A strong legal framework set centrally.

Within this, considerable devolution of power and responsibility to sickness funds, physicians' associations, and other bodies.

Diffusion of the remaining government responsibilities between Federal, State, and local governments.

Self-government (or Selbstverwaltung) is an important principal in the West German health care system. The government devolves specified powers and duties to certain regulated but self-governing bodies, including sickness funds and physicians' associations, which represent private interest groups yet have compulsory membership. These bodies possess considerable autonomy within the framework of regulations set centrally (Stone, 1980).

The principle of devolution of power applies, also, to certain institutions designed to regulate, guide, and inform the bargaining process arising from countervailing power or bilateral monopoly. The independent arbitration process available to the parties negotiating hospital budgets seems to fall into this category. So does the Concerted Action set up by the 1977 Cost Containment Act. Concerted Action is a national conference consisting of about 70 representatives of the various interested parties in the health care system which meets twice a year to agree on maximum rates of increase of health expenditure on ambulatory and dental care, on pharmaceuticals, and on other medical supplies. The objective is to maintain stability in the rate of health insurance contributions (Henke, 1986). It seems to work mainly through moral persuasion and the incentive the participants have to avoid further cost-containment laws (Schulenburg, 1990a). Since 1986, Concerted Action has been supported by a standing council of expert advisers which has produced a series of influential reports on shortcomings of the German health care system (such as excessive hospital beds) and making suggestions for reforms (such as giving general practitioners a gatekeeper role in the system and introducing capitation payments for ambulatory care doctors) (Alber, 1989).

Turning to the diffusion of those power retained by government in the western German health care system, each level of government has distinct responsibilities:

The Federal Government is responsible for drafting laws (most of which have related to cost containment recently), for general policy, and for jurisdiction over the health insurance system.

The State governments are responsible for approving Federal legislation (through their representation in the Upper House); for the local supervision of sickness funds and physicians' associations; for managing State hospitals, including teaching hospitals; for hospital planning (each State has a plan for controlling capacity in both public and private hospitals); for all investment in hospitals accredited by the State plan; and for regulating standards of medical education and thereby, indirectly, the enrollment of medical students.

Local governments are responsible for public health services, for managing local hospitals, for investment in local hospitals, and for the management and financing of public nursing homes (which are not covered by the statutory insurance scheme).

These arrangements are not without their tensions. There is sometimes disagreement between Federal and State governments over general policy and there is often confrontation over hospital expenditure because the Federal Government tends to identify with the sickness funds, whereas the State governments have a large stake in the provision of hospital services.

Problems leading to reforms

The system described previously tends to suffer from a number of problems. One difficulty is that in keeping with other systems of health care which rely heavily on third-party payment, there is a generalized lack of cost consciousness. Patients have little financial incentive to limit their demands, and providers have little financial incentive to limit their supply of care. Such competition as exists tends to be expressed as a struggle to increase volume and quality rather than as a struggle to reduce costs. In these circumstances, the mechanism for determining expenditure is transferred to the negotiations between the insurers and the providers. We have seen that these negotiations tend to take the form of bilateral monopolies in West Germany. However, a second difficulty is that the bargaining power of the buyers is not always evenly matched with that of the sellers in such markets. There have been times, such as during the “cost explosion” of the early 1970s, when the providers have had the upper hand. There have been other times, such as during the subsequent phase of cost containment, when the balance between the two parties has been more even. Most of the health care reforms which were introduced from the late 1970s onwards were devoted either to increasing cost consciousness among consumers and providers or to strengthening the bargaining power of the sickness funds in their negotiations with providers. In the 1980s the most buoyant programs in cash terms were pharmaceuticals and hospital expenditures (Schneider, 1990).

A further problem is that the allocation of given resources within the system is not believed to be very efficient. The combination of a rigid specification of benefits centrally and the incentives contained in the fee schedule produce a bias in favor of acute diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and away from personal services, prevention, and long-term care. Also, it is said that there are excessive hospital beds and excessive average length of stay in hospital.

Recent reforms in western Germany

Cost Containment Acts: 1977, 1982, and 1983

The era of cost containment in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) began with the Health Care Cost Containment Act of 1977 (Stone, 1979). The most important measures, here, were:

Introduction of the principle of income-oriented expenditure policy.

Introduction of the Concerted Action conference (described previously).

Reintroduction of what amounted to lump sum prospective budgets for payments by sickness funds to physicians' associations.

Strengthening of utilization review of physicians.

Introduction of, or increases in, cost sharing for dentures, prescriptions drugs, and patient transport.

Introduction of a negative list for drugs.

Introduction of a risk-sharing scheme for pensioners across all sickness funds.

A Supplementary Cost Containment Act was brought in in 1982 which introduced, among other things, further increases in charges for prescription drugs and the publication of the price lists for comparable drags referred to previously. In 1983, a Supplementary Budget Act was passed which introduced: a new charge of 5 DM per day, up to 14 days, for hospital stays; a new charge of 10 DM per day for rehabilitation cures, and new prescription charges of 2 DM per drug.

Hospital Reform Acts, 1982-86

Hospital expenditure had been largely excluded from the 1977 Act. This began to be remedied in 1982 when the government introduced the Hospital Cost Containment Act (Eichhorn, 1984). The provisions of this Act included:

Making hospital daily rate the subject of bargaining between representatives of the sickness funds and the hospitals.

The involvement of both the associations of sickness funds and the associations of hospitals in the drawing up of State hospital plans.

Extending the responsibilities of Concerted Action to the hospitals.

Hospital reform was continued with the Hospital Financing Act of 1985 and the Federal Hospital Payment Regulation of 1986 (Altenstetter, 1987). These provided for:

Hospital investment to be returned to the State governments rather than being shared between the State and Federal governments.

Prospective global budgets to be introduced for operating costs for each hospital, to be negotiated between representatives of the sickness funds and the hospitals, based on inclusive costs and anticipated occupancy rates.

Overall, average per diem rates to be set in light of these costs and comparisons with comparable efficient hospitals.

Actual payments to be based on 75 percent of the agreed daily rate for shortfalls in actual days compared with expected days and on 25 percent of the agreed daily rate for surpluses in actual days compared with expected days.

Hospitals to be able to carry over surpluses into subsequent years.

Recourse to neutral arbitration rather than State government arbitration in the event of disagreement.

The possibility of special cost-per-case payments for some high-cost procedures.

Hospitals to begin keeping statistics on the diagnosis, specialty, age, and length of stay of their patients with a view to developing cost-per-case pricing at a future date.

Need Planning Law, 1986

The 1986 Need Planning Law enabled physicians' associations and sickness funds to close to newcomers areas with more than a 50-percent excess of doctors in certain specialties. In addition, measures were introduced to enable associations and funds to invite doctors to retire early.

Health Care Reform Act, 1989

Finally, following a jump in average contribution rates from about 11.5 percent to nearly 13 percent in the mid-1980s, which was a result both of rising unemployment and of further increases in expenditures, the government introduced a further bulky package of reforms in the Health Care Reform Act of 1989. This has been described as the most important statute on the statutory health insurance system since the Law of 1911 (Schneider, 1990). It was aimed both at cost containment and at financing some selected improvements to benefits. A summary of its content follows.

Requirements that were introduced for providers to be more economical were as follows:

The Labour and Social Affairs Ministry introduced fixed payments for drugs with substitutes (not still on patent) based on the lowest price that would ensure an adequate supply. Fixed prices were to be brought in in stages: first for drugs with the same active ingredient (about 33 percent of the market); then for drugs with therapeutically equivalent ingredients; and finally for drugs with comparable pharmacological profiles. It was anticipated that eventually about 55 percent of the market would be directly affected by the new regulations (Jensen, 1990). Once such fixed payments were established for a particular drug, the prescription charge would be abolished. The doctor would remain free to prescribe a product with a price above the fixed payment level, but the patient would have to pay the difference. Until the fixed prices were brought in, the prescription charge would be raised from 2 DM to 3 DM. These measures were designed to provoke price competition among the pharmaceutical manufacturers. Similar fixed payments based on the lowest viable price for effective products were brought in for other aids and appliances.

Tighter procedures were introduced for monitoring the prescribing of sickness fund physicians.

New obligations were introduced for pharmacists to dispense generic equivalents, if prescribed by the doctor.

Sickness funds were given the freedom to cancel contracts with surplus and uneconomical hospitals.

Hospitals were obliged to publish price lists, and doctors were obliged to consider the cost effectiveness of their referrals.

There would be improved coordination of inpatient and outpatient care to cut down on unnecessary hospitalization. This was to be agreed contractually between the sickness funds, hospitals, and sickness fund doctors, with recourse to arbitration if necessary.

Similarly, equipment committees would be set up to reduce duplication of equipment in hospitals and doctors' practices.

New financial incentives would be brought in by State governments to help cut surplus hospital beds.

Sickness funds were given the freedom to experiment with innovative ways of providing and paying for services including experimental cost sharing, no claims bonuses, and new ways of paying providers. The experiments could last up to 5 years and must be evaluated scientifically.

Revised cost-sharing measures were as follows:

The charge for a hospital day would be increased from 5 DM to 10 DM beginning in 1991.

Much higher cost sharing was introduced for patient transport.

The conditions exempting some patients from charges were revised and new income-related ceilings placed on total charges for any one individual.

Changes to benefits were as follows:

Some minor benefits were removed.

A number of new preventive benefits were introduced, mainly in the form of entitlements to health checks for various age groups.

Financial support was given to the carers of the long-term sick. The sickness fund would pay for: up to 4 weeks holiday for family carers beginning in 1989; and a long-term care allowance of either 400 DM per month for the family carer or 750 DM per month for professional nursing services, designed to purchase up to 25 hours of care, beginning in 1991.

Improved regulation of quality, activity, numbers of doctors, and conditions of practice were as follows:

Quality assurance programs were to be introduced for both ambulatory care and hospital doctors following negotiations between sickness funds and the physicians' associations. The method of quality assurance was to be left to the interested parties but it was envisaged, for example, that utilization review involving random samples of 2 percent of ambulatory care doctors each quarter would be instituted.

The medical examiner service would be transformed into an independent medical advisory service for the sickness funds.

The State governments were urged to act further to reduce, by indirect means, the intake to medical schools.

There would be tightening of the conditions for doctors to be admitted to practice with the sickness funds.

Changes to contributions were as follows:

An income limit was introduced for compulsory health contributions by blue-collar workers, giving them the same conditions as salaried workers.

Pensioners' contributions were to be raised to the same average level as workers' contributions (6.4 percent) beginning in 1989.

Contributions for children insured in the public system by privately insured parents would be doubled.

More fundamental reforms were envisaged at a later date involving a modernization of the organizational structures of the sickness funds. The aim would be to reduce differentials in contribution rates, to remove distortions to competition, and to abolish inequalities in the treatment of manual workers and salaried employees.

Recent reforms in eastern Germany

In the negotiations leading to the reunification of Germany in October 1990, it was decided to put the health system in eastern Germany on the same financial and organizational basis as that in western Germany as quickly as possible. The main changes that will be brought in are as follows:

On January 1, 1991, a complete network of Ortskrankenkassen (local sickness funds) will come into operation in eastern Germany. Other sickness funds will be free to set up in eastern Germany if they wish.

The great majority of the population in eastern Germany will be insured compulsorily because of their income levels.

The contribution rate to all sickness funds will be set at 12.8 percent (the average rate in western Germany), at least for a year.

The aim is for expenditure to balance income. This will be facilitated by setting average fees and charges in eastern Germany at 45 percent of the level prevailing in western Germany (reflecting the estimated difference in the current standards of living in the two parts of Germany). In the case of pharmaceuticals, although prices will be homogeneous in western and eastern Germany, in the eastern part there will be a larger discount for the mandatory sickness funds than in the western part. In addition, the pharmaceutical industry has undertaken to share with the State, to a limited extent, any deficits incurred by the funds because of high prices and consumption.

On the delivery side, polyclinics and group practices remain popular with many eastern doctors, especially with older doctors and women who wish to continue working part time. They also remain popular with a majority of eastern patients. Consequently, polyclinics will remain, at least temporarily, but will be reviewed after 5 years.

The doctors will be able to choose between continuing salaried service and fee-for-service payment as in western Germany. This is presenting difficulties because fees in the West are inclusive of practice expenses, whereas salaries in the East exclude the overheads of polyclinics.

A need has been identified for up to 20 billion DM of investment in buildings and equipment in eastern Germany to bring standards up to those in western Germany. It is not yet clear how this will be financed.

Performance of German health systems

Western Germany

To summarize some key points in the previous description, most western Germans are covered either by statutory or private health insurance which offers access to a high level of health care and ensures that for the most part they have little incentive to economize. Consumers have free choice among ambulatory care physicians but most do not have free choice of insurer. Providers have considerable autonomy and financial incentives to expand care but when it comes to payment they face the associations of autonomous sickness funds, which are charged with stabilizing the contribution rates of their members. The formalized and regulated bargaining which ensues resembles bilateral monopoly, although the sickness funds cannot control volume. On many occasions in the past, the bargaining has favored the providers. However, for over a decade the Federal Government has sought to tip the balance toward the sickness funds by legislating for the promulgation of agreed national guidelines on rates of growth of expenditure, for fixed prospective budgets for physicians' associations and hospitals, and for independent arbitration on hospital rates. On the whole, there has been little price competition, as opposed to quality competition, but recently steps have been taken toward encouraging price competition in the supply of pharmaceuticals and hospital services.

The Federal Government was successful in stabilizing the share of health expenditures in the gross domestic product (GDP) following the cost explosion of the early 1970s. The share had leaped from 5.5 percent of GDP in 1970 to 7.8 percent of GDP in 1975 but in 1980 it was 7.9 percent and in 1985 and 1987 it was 8.2 percent, according to Schieber and Poullier (1989). Measured in dollars, converted at purchasing power parity exchange rates, health expenditure per capita was $1,093 in 1987, close to that for France and the Netherlands but approaching 50 percent more than that in the United Kingdom. Health expenditures per capita was almost exactly at the level that would be predicted by a regression line associating per capita health expenditure with per capita GDP for all OECD countries (Schieber and Poullier, 1989).

There is, however, a puzzle with these OECD figures. Various authors (such as: Reinhardt, 1981; Altenstetter, 1986; and Henke, 1988 and 1990) report shares of health expenditure in GDP (or GNP) in western Germany from 9 to 10 percent from 1975 to 1984 (excluding transfer payments). Also, it seems that expenditures on Germany's 150,000 nursing home beds (Eichhorn, 1984) has been excluded from both sets of figures (unlike, say, for the Netherlands). There are suggestions, here, that per capita health expenditures in Germany may lie above the regression line linking per capita health expenditures with per capita GDP.

As might be expected, expenditures on privately insured services have risen more rapidly than expenditures on publicly insured services during the era of cost containment. The private share of expenditures went up from 18 percent in 1977 to 22 percent in 1989 (Schneider, 1990).

In the past couple of years, the Federal Government has been successful in meeting the financial objectives set for the Health Care Reform Act of 1989. The rate of growth of expenditures by sickness funds fell from 5.8 percent per annum in 1988 to 3 percent per annum in 1989. About 300 sickness funds have been able to lower their contribution rates, and it is now hoped that average contribution rates will fall to 12.6 percent in 1992 (from about 12.9 percent in 1988) instead of rising to 13.5 percent in the absence of the reforms. Among other things, 4 uneconomical hospitals have been closed, and 20 more closures have been planned as a result of the reforms. The introduction of fixed payments for drugs has been particularly successful. In the first year, prices of drugs included in the scheme fell by 21 percent whereas the prices of drugs outside the scheme rose by 2 percent (Schneider, 1990). Most of the producers affected by the scheme soon lowered their prices to the ceiling. There was relatively little sign of willingness by consumers to pay for brand name products.

Turning to volume and price, western Germany has high levels of resources devoted to health care, high health care prices, and high levels of health service activity, according to OECD statistics (Schieber, 1987). There are no reports of hospital waiting lists. According to the latest, OECD figures (Health OECD: Facts and Trends, forthcoming), physicians per 1,000 population were 2.9 in 1988, compared with 1.9 in 1975. Projections suggest that physician numbers will rise by a further 50 percent by the year 2000 (Brenner, 1989). The rising number of physicians was associated with falling relative incomes. The ratio of the average net pre-tax income per physician to the national average wage was about 4.5 in 1985, having fallen from about 5.5 in 1975 (Sandier, 1989). The latest figures from the OECD (Health OECD: Facts and Trends, forthcoming) suggest that acute care hospital beds were 7.6 per 1,000 population in 1988, compared with an average of 5.1 in seven OECD countries. Ambulatory medical care consultations per capita were 11.5 in 1986, compared with an average of 6.3 in these seven OECD countries. Prescribed medicines per person were about 12.5 in 1986, compared with an average of 9.5 in these seven OECD countries. Average drug prices are estimated to be the highest in the European Community (SNIP, 1988). The acute hospital admission rate was 18.3 per 100 in 1987, compared with an average of 15.1 in these seven OECD countries. Finally, average length of stay in a hospital was 12.7 in 1988, compared with an average of 9.4 in these seven OECD countries (excluding Spain).

The effects of the 1979 Bavarian Contract, which was aimed at rewarding ambulatory care physicians for cutting expenditures on prescribing and hospital referrals, were disappointing. It seems that overall there was relatively little substitution of physician services for prescribing and hospital referrals and no savings in costs. One ready explanation is that the financial incentives in the scheme were designed to work only at an aggregate level, leaving open the possibility of “free rider” behavior by the individual physician. Also, in the case of hospital expenditures, the existence of retrospective, per diem, cost reimbursement at the time the Contract was signed, meant that any reduction in admissions could be countered in the hospitals by the raising of length of stay or the concentration of fixed costs (Jurgen and Potthoff, 1987).

It is difficult to say what impact the Federal Republic's high and growing level of health expenditures had on the health status of the population because many other factors, not least its high and growing standard of living, will have influenced health. However, it is worth reporting that in 1987, western Germany was a middling OECD country in terms of male and female life expectancy at birth. It was a better than middling country in terms of perinatal mortality in 1987, having moved sharply up the international league table from a below-middling position in the 1960s. There was a marked improvement in perinatal mortality in the 1970s, from 2.6 per 100 births in 1970 to 1.2 per 100 births in 1980. This was followed by a further sharp improvement from 1980 to 1988, which exceeded that for the other countries in the study for which we have data. Germany now has one of the lowest perinatal mortality rates in the OECD countries. It is believed among epidemiologists in Germany that the improvements in the 1980s were due, at least in part, to the introduction of the quality assurance program in hospital obstetrics departments referred to previously. On a longer time perspective, infant mortality had been 5.6 in 1950 and had fallen to 0.85 in 1986 (World Health Organization, 1987).

In terms of consumer satisfaction, a recent international survey of satisfaction with health systems in 10 nations (Blendon et al., 1990) suggested that consumers were relatively satisfied with arrangements in western Germany. Germany ranked third (equal with France) in the percentage of respondents who thought that only “minor changes” were needed to their health care system.

Eastern Germany

Statistics on health expenditures in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) are not easy to come by and may not be reliable. However, expenditures on medical care were reported at 5.5 percent of national income in 1980, compared with western Germany's 8.5 percent of GDP in the same year (Ministry of Health, GDR, 1981). The ratio of GNP per capita in eastern Germany compared with western Germany has been variously estimated at figures ranging from 0.45 to 0.56 and 0.81 (Lohmann, 1986). All that can be said from these figures, perhaps, is that the GDR had a standard of living well below that in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) before reunification and spent less, as a proportion, on health services and must, therefore, have had much lower health expenditures per capita.

However, in terms of real resources devoted to health services and in terms of health service activities, the two countries seem to have been fairly similar. The GDR was reported as having 2.3 physicians per thousand in 1985 (World Health Organization, 1987), compared with 2.6 in the FRG. In 1977, the GDR was reported as having 10.6 hospital beds per thousand, compared with 11.8 in the FRG, and both countries had similar levels of dentists and pharmacists per thousand (Lohmann, 1986). Hospital length of stay was reported as similar in the two countries (Rosenberg and Ruban, 1986). Given that hospital beds per thousand were similar, this suggests that admission rates were not very different. Finally, consultation rates with doctors seem to have been similar in the two countries at 9.0 per person in the GDR in 1976 (Rosenberg and Ruban, 1986) and 10.9 per person in the FRG in 1975 (Health OECD: Facts and Trends, forthcoming). If the GDR enjoyed a similar volume of health services to the FRG but had much lower health expenditures per capita, then the prices of health services must have been much lower in the GDR.

Turning to health status, in 1987, the reported expectation of life at birth in eastern Germany, 69.9 years for males and 76.0 for females, was not far behind that of western Germany at 72.2 for males and 78.9 for females. The infant mortality rate, which had been 7.2 per 100 in 1950, had fallen to 0.92 in 1986 (World Health Organization, 1988). Although the infant mortality rate was above that of western Germany in 1986 (0.85), the fall since 1950 had been larger. If the official figures can be believed, the former GDR had respectable health statistics for a country with its standard of living.

Comparison of western and eastern Germany

The two Germanies can be viewed as an unusual social experiment. A single country with a homogenous language and culture and a common history was divided into two very separate parts which were forced to diverge in their political, economic, and social institutions for 45 years before being reunited. This provides us with a rare opportunity to compare the performance of a liberal democracy with a communist state during this period, holding constant the initial conditions and many of the potentially confounding factors (Light, 1985). The full history of this “experiment” has yet to be written. Meanwhile, the overwhelming verdict in eastern and western Germany is that socialism did not work. Not only was there more personal freedom for most of the people for most of the time in western Germany than in eastern Germany, but also standards of living rose much more quickly in the FRG before reunification than they did in the former GDR.

However, it is not clear from the figures just quoted that the health care system of the former GDR did not work. Improvements to health status in eastern Germany seem to have kept up, more or less, with those in western Germany, despite the fact that the standard of living grew much more slowly in the East. Given that the crude volume of some of the major health services was similar in the two countries, there is a weak suggestion here that the eastern German system was at least as effective as that in the West. It is clear that eastern Germany lacked much of the equipment and many of the drugs available in the West. However, it seems that doctors in eastern Germany received training at least as long as that in western Germany. Moreover, Light (1985) has argued that whereas the eastern German system suppressed some aspects of physicians' autonomy and relied on centralized management, it also: introduced integration of hospital and ambulatory care; linked health with housing, workplace, and schools; and placed emphasis on prevention (starting with compulsory comprehensive vaccination of children). In contrast, whereas the western German health care systems emphasized the autonomy of physicians, sickness funds, and patients, and introduced a wealth of curative, high technology medicine, it preserved doctor-induced demarcation between hospitals and ambulatory care and neglected some preventive medicine. Although there are too many factors at work here to be sure of causation, it is not obvious that all the strengths lay in western Germany.

Discussion

Remaining problems

Western Germany

The durability of the system of health care in western Germany is a testament to its many strengths. It has achieved high and equitable standards of health care while preserving patient choice and provider autonomy. It has had striking success recently in reducing perinatal mortality. It has achieved satisfactory cost containment by stabilizing its health expenditures share of GDP. It has performed well in an international survey of satisfaction with systems of health care.

These objectives have been achieved in a predominantly publicly financed health care system without significant cost sharing and without central intervention of the command and control type. True, there has been a strong and effective central policy on the rate of growth of health expenditures and planning of hospital facilities by State governments. Apart from this, the system relies mainly on self-regulation by establishing a balance of negotiating power between antonomous sickness funds and providers and by allowing consumer choice to determine much of the flow of funds in ambulatory care. More recently, there have been some careful moves in the direction of increasing competition among hospitals. Generally, mixed systems of reimbursement prevail which provide both baseline expenditure and rewards for productivity, within global budgets.

Certain problems remain, however. Although the government has had much success in containing costs during the past decade and one-half, certain adverse pressures remain. To some extent this is a result of factors outside the control of government, such as the aging of the population. Western Germany is facing a marked deterioration in the dependency ratio during the next four decades, which will present financial problems for the pay-as-you-go social security and health care systems (Schulenburg, 1990b). To some extent it is attributable to factors that might be amenable to further reform, such as the continuing incentives for providers to escalate the volume and quality of care and the low level of competition among insurers and some providers.

It is not difficult to find expressions of concern in the German literature about the efficiency and cost effectiveness of health care in western Germany. It is said that there is a relative overproduction of high technology, curative, somatic medical care and a relative underproduction of preventive care, psychiatric care, and long-term care. This seems to be the product of a combination of rigidly specified benefits under the public scheme and the nature and structure of the fee-for-service incentives for doctors and other providers. The average length of stay in a hospital is regarded as excessive. Such excessive stay is likely to stem from the continuing role accorded to per diem payments, from the sharp separation between ambulatory and hospital care, and from the dual hospital financing system, which means that the State governments, which are responsible for planning and investment in capacity, are not responsible for running costs.

There are mixed feelings about the rate of growth in the number of doctors. Projections suggest that the numbers will rise by 50 percent by the year 2000. Whereas a further increase in numbers is likely to help any competitive strategy and further reduce the relative incomes of physicians, it is also likely to generate induced demand for services under fee-for-service remuneration (Schulenburg, 1990b).

Equity remains a problem. Solidarity is patchy and incomplete. Generally, white-collar workers have more choice than blue-collar workers, especially if they are above the income ceiling for compulsory insurance. Meanwhile, compulsorily insured individuals, with the same risk characteristics and the same income, may find themselves paying very different contributions simply because they are obliged to belong to sickness funds whose memberships have different risk profiles.

It is argued that sickness funds are over-regulated and have inadequate incentives to act as efficient buyers on behalf of their members. There is little, if any, competitive pressure on sickness funds, and there is some disillusionment with the quality of control exerted by the boards of representatives of the employers and employees.

Eastern Germany

The system of health care in eastern Germany, now being partly dismantled, could also lay some claims to past successes. According to the available figures, it helped to achieve good improvements in indicators such as infant mortality with relatively low expenditure and relatively poor facilities. It would not be surprising if well-trained and adequately salaried doctors were capable of delivering a high proportion of the available range of effective medical care with relatively few drugs and vaccines and with relatively simple facilities and equipment. Also, there were probably benefits from multispecialty group practice and good integration between ambulatory and hospital care. However, physical standards were low, high technology was lacking, doctors had little autonomy, and such patient choice as existed was not translated into financial incentives for providers. The whole system is discredited by its association with the former GDR. Germany has decided decisively to abandon this experiment with an autocratic, integrated health care model in favor of a return to the liberal, contract model devised by Bismarck.

Potential solutions

Following the reunification of Germany, the most urgent priority is the reform of health care in the eastern part of the country to bring it into line with that in the western part. As has been indicated, it has been decided to reintroduce sickness funds in the East, to set contribution levels at the same average level in the West, and to begin with fees and prices at about one-half the level of those in the West. It is not yet clear what will be the ultimate fate of polyclinics and salaried medical practice in eastern Germany. It is possible that a more pluralistic system of health care than that which prevailed in western Germany may eventually emerge from the reunification of the two parts of the country.

Meanwhile, debate continues about further reforms to the system developed in western Germany. New arrangements for financing long-term care are under discussion involving either: the introduction of a mandatory, funded scheme for private insurance offering a cash benefit that would pay for nursing home care or domiciliary care; or the introduction of a new long-term care benefit to be administered (separately) by the sickness funds with compulsory contributions on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Reorganization of the sickness funds is on the policy agenda with a view to reducing differentials in contribution rates, removing distortions to competition, and abolishing inequities in the treatment of manual workers and salaried employees. There are signs that these objectives will be achieved from the outset in eastern Germany.

Proposals for introducing a gatekeeper role for general practitioners and capitation payments in place of fee-for-service payments for ambulatory care doctors have been put forward by the group of experts which advises Concerted Action.

Finally, some independent experts have floated ideas about more radical structural reforms, involving fully competitive insurance and provider markets (Gitter et al., 1989; Jacobs, 1989). The systems they propose are aimed at combining “solidarity” in health insurance with competition both for health insurance and for health care itself. The systems bear some resemblance to the Dekker reforms in the Netherlands (Ministry of Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs, 1988) and to the ideas put forward for managed competition in France (Launois et al., 1985). However, these proposals have not yet been spelled out as clearly as those in the Netherlands and, as in France, there is no sign at present that they will be taken up by the government.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Dr. Peter Rosenberg, Professor Klaus-Dirk Henke, Dr. Jens Alber, and Professor J.-M.G. Schulenburg for help and advice. They are not responsible for any remaining errors.

Footnotes

This article was prepared as part of a project at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on the reform of health care systems. It was supported by grants from Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. It will also appear in The Reform of Health Care Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries (forthcoming, 1991), which will be available from OECD Publications and Information Center, 2001 L Street, NW., Suite 700, Washington, D.C. 20036-4095, Telefax (202) 785-0350. The copyright of this article is retained by OECD, and foreign rights are reserved. Any opinions expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent those of OECD or any of its member countries.

Reprint requests: Jeremy W. Hurst, Department of Health, Friars House, 157-168 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8EU, United Kingdom.

References

- Ade C, Henke KD. Medical Manpower Policies in the Federal Republic of Germany. University of Hannover; Nov. 1990. Typescript. [Google Scholar]

- Alber J. Structural Reforms in the West German Health Care System. Paper prepared for a Conference on Structural Reforms of National Health Care Systems; Dec. 8-9, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alber J. Characteristics of the west German health care system in comparative perspective. In: Kolinsky E, editor. The Federal Republic—Forty Years On. Berg, Oxford, New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Altenstetter C. Reimbursement policy of hospitals in the Federal Republic of Germany. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 1986;1:189–211. doi: 10.1002/hpm.4740010304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenstetter C. An end to a consensus on health care in the Federal Republic of Germany? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1987 Fall;12(3) doi: 10.1215/03616878-12-3-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beske F. Expenditures and attempts of cost containment in the statutory health insurance system of the Federal Republic of Germany. In: McLachlan G, Maynard A, editors. The Public Private Mix for Health. The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Beske F. Federal Republic of Germany. In: Saltman RB, editor. The International Handbook of Health-Care Systems. Greenwood Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Leitman R, Morrison I, Donelan K. Satisfaction with health systems in ten nations. Health Affairs. 1990 Summer;9(2) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner G. Cost Controlling Measures in Out-Patient Medical Care in the Federal Republic of Germany. Paper presented to the First European Conference on Health Economics; Barcelona. Sept. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Breyer F. Distributional Effects of Coinsurance Options in Social Health Insurance Systems. Paper presented to the First European Conference on Health Economics; Barcelona. Sept. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn S. Health services in the Federal Republic of Germany. In: Raffel MW, editor. Comparative Health Systems. Pennsylvania State University; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven AC. Theory and Practice of Managed Competition in Health Care Finance. North Holland, Amsterdam: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gitter W, Hauser H, Henke KD, et al. Scientific Study Group “Health Insurance.”. Universität Bayreuth; Jun, 1989. Structural Reform of the Statutory Health Insurance System. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser WA. Lessons from Germany: Some reflections occasioned by Schulenburg's “Report”. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1983 Summer;8(2) doi: 10.1215/03616878-8-2-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser WA. Paying the Hospital. Jossey-Bass Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Godt PJ. Confrontation, consent, and corporatism: State strategies and the medical profession in France, Great Britain, and West Germany. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1987 Fall;12(3) doi: 10.1215/03616878-12-3-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel W. Reform of health services in the Federal Republic of Germany. International Social Security Review. 1989 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- Henke KD. A concerted approach to health care financing in the Federal Republic of Germany. Health Policy. 1986;6:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(86)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke KD. The Health Care System of the Federal Republic of Germany. Universität Hannover, Hanover; Apr. 1988. Discussion Paper No. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Henke KD. Health Care Financing Review. 1989 Annual Supplement. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1989. International comparisons of health care systems; pp. 93–96. HCFA Pub. No. 03291. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Henke KD. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research, Supplement 1: Comparative Health Systems. JAI Press Inc.; 1990. The Federal Republic of Germany. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K. Elements of Competition in the Statutory Health Insurance: The Case of the Federal Republic of Germany. Paper presented to the First European Conference on Health Economics; Barcelona. Sept. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A. Price Ceilings for Pharmaceuticals—Recent Experiences with a New Instrument in Health Politics. Bundesverband der Betriebskrankenkassen; 1990. Typescript. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgen J, Potthoff P. Cost containment in a statutory health insurance scheme by substitution of outpatient for inpatient care? The case of the Bavarian Contract. Health Policy. 1987;8:153–169. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(87)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkmuller E. The medical-industrial complex. In: Light DW, Schuller A, editors. Political Values and Health Care: The German Experience. The MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Launois R, Majnoni d'Intignano B, Stephan J, Rodwin V. Les Réseaux de Soins Coordonnés (RSC): Propositions pour une Réforme Profonde du Systeme de Santé. Revue Francaise des Affaires Sociales. 1985 Jan-Mar;39(1):37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Leidl R. The hospital financing system of the Federal Republic of Germany. Effective Health Care. 1983;1(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light DW. Values and structure in the German health care systems. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly/Health and Society. 1985;63(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann U. Sociological portrait of the two Germanies. In: Light DW, Schuller A, editors. Political Values and Health Care: The Germany Experience. The MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (GDR) Health Care in the German Democratic Republic. Berlin: May, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Welfare, Health Cultural Affairs (Netherlands) Changing Health Care in the Netherlands. Rijswijk: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer G, Unterhuber H. Failures of the hospital financing system of the Federal Republic of Germany and reform proposals. Effective Health Care. 1985;2(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus R, Schrader WF. Planning and management of public health in the Federal Republic of Germany. Health Policy. 1985;5:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(85)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Financing and Delivering Health Care. Paris: 1987. Social Policy Studies No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt UE. Health Care Financing Review. 2. Vol. 3. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1981. Health insurance and health policy in the Federal Republic of Germany; pp. 1–14. HCFA Pub. No. 03139. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg P, Ruban ME. Social security and health care systems. In: Light DW, Schuller A, editors. Political Values and Health Care: the German Experience. The MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sahmer S. Public and Private Health Insurance. Paper presented to the Conference on Health Care in Europe after 1992; Rotterdam. Oct. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sandier S. Health Care Financing Review. 1989 Annual Supplement. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1989. Health services utilization and physician income trends; pp. 33–48. HCFA Pub. No. 03291. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicke RK. Trends in the diffusion of selected medical technology in the Federal Republic of Germany. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1988;4:395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber GJ, Poullier JP. International health care expenditure trends. Health Affairs. 1989 Fall;8(3):169–177. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.8.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. German Health Expenditure Constraint Strategies. Paper prepared for the Ninth Meeting of the Working Party on Social Policy; Paris. Nov. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg JMG. Report from Germany: Current conditions and controversies in the health care system. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1983 Summer;8(2) doi: 10.1215/03616878-8-2-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg JMG. Health Care in the '90s: A Report from Germany. University of Hannover; 1990a. Typescript. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg JMG. The German Health Care System from an Economic Perspective. University of Hannover; Jul, 1990b. Typescript. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Harrison S. Physician autonomy in the Federal Republic of Germany, Great Britain and the United States. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 1986;2 doi: 10.1002/hpm.4740010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNIP. Les prix des specialities pharmaceutiques remboursables dans la communauté européenne. Syndicat National de l'Industrie Pharmaceutique; Paris: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stone DA. Health care cost containment in West Germany. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1979 Summer;4(2) doi: 10.1215/03616878-4-2-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DA. The Limits of Professional Power. University of Chicago Press; 1980. National Health Care in the Federal Republic of Germany. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics Annual. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel P. Bonus systems in health insurance. A microeconomic analysis. Health Policy. 1987;7:273–288. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(87)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]