Abstract

Skeletal muscle tissue engineering (SMTE) aims to repair or regenerate defective skeletal muscle tissue lost by traumatic injury, tumor ablation, or muscular disease. However, two decades after the introduction of SMTE, the engineering of functional skeletal muscle in the laboratory still remains a great challenge, and numerous techniques for growing functional muscle tissues are constantly being developed. This article reviews the recent findings regarding the methodology and various technical aspects of SMTE, including cell alignment and differentiation. We describe the structure and organization of muscle and discuss the methods for myoblast alignment cultured in vitro. To better understand muscle formation and to enhance the engineering of skeletal muscle, we also address the molecular basics of myogenesis and discuss different methods to induce myoblast differentiation into myotubes. We then provide an overview of different coculture systems involving skeletal muscle cells, and highlight major applications of engineered skeletal muscle tissues. Finally, potential challenges and future research directions for SMTE are outlined.

Introduction

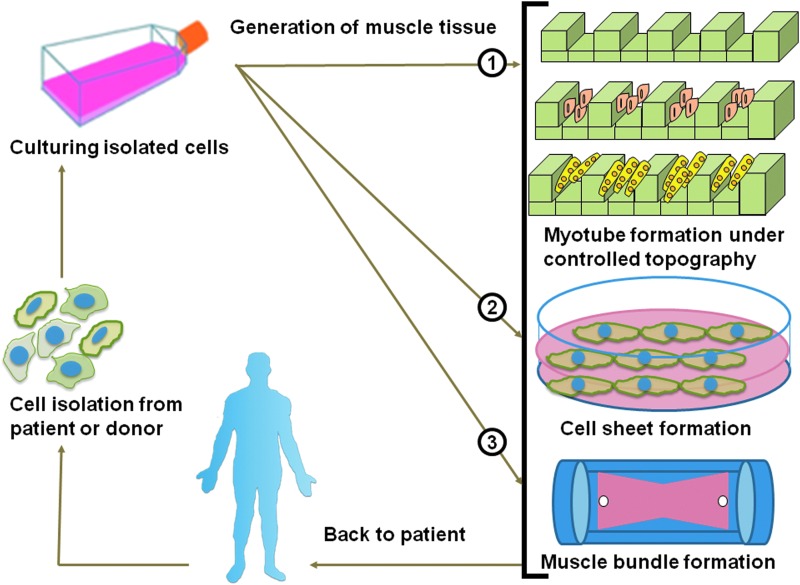

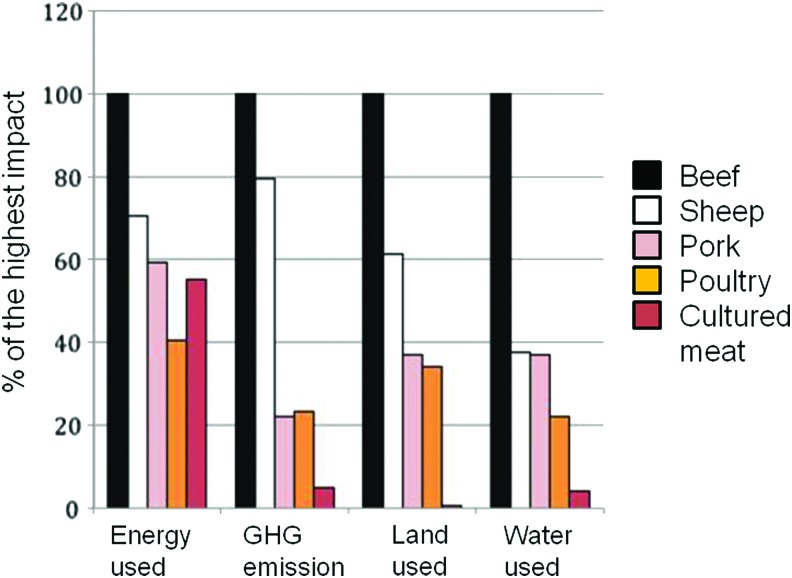

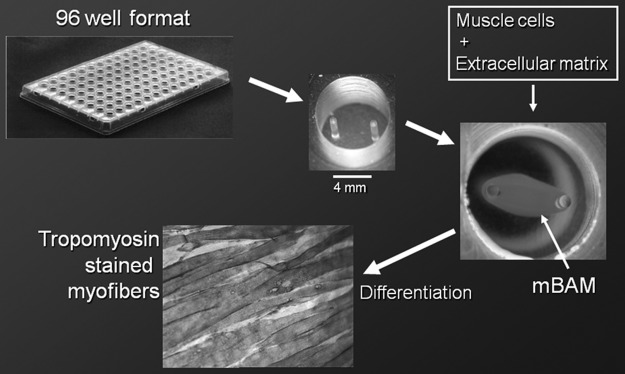

Approximately 45% of the mass of the human adult body is muscle tissue. Muscles play an important role in locomotion, prehension, mastication, ocular movement, and other dynamic events, including body metabolism regulation. Myopathy, traumatic injury, aggressive malignant tumor extraction, and muscle denervation are the most common clinical reasons for therapeutic or cosmetic reconstructive muscle surgery. Therefore, the engineering of muscles as clinical substitutes for various medical applications is beneficial. In this context, skeletal muscle tissue engineering (SMTE) focuses on the development of engineered tissues capable of repairing or replacing normal function in defective muscles. The concept of SMTE (Fig. 1) involves the culture of muscle cells that are harvested either from the patient or a donor, with or without the use of tissue scaffolds to generate functional muscle that can be implanted in the patient's body.1 Further, SMTE also has great potential for drug screening,2,3 construction of hybrid mechanical muscle actuators,4,5 robotic devices,6–8 and as a potential food source containing engineered meat.9

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the concept of skeletal muscle tissue engineering showing three different types of culture techniques for generating muscle tissue. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Muscle tissue can be classified as smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle, which have been extensively reviewed previously.10–13 However, as the properties of engineered muscles are still far from their natural counterparts, we aim to review and address the methodology for building skeletal muscle with recent insights and to overcome the barriers between different fields of research to provide a better understanding of the nature of muscle and practical ways to engineer muscle tissue. Specifically, we review and update recent findings on the methodology and various technical aspects of SMTE, including cell alignment and differentiation. We start by addressing the structure and organization of muscle tissue and then describe useful methods to align myoblasts cultured in vitro, since cell alignment is a prerequisite for the formation of myotubes. We also address the molecular basics of myogenesis and describe different methods to induce myoblast differentiation into myotubes. We then give an overview of different coculture systems involving skeletal muscle cells, and highlight major applications of engineered skeletal muscle tissues. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of potential challenges and future research directions for SMTE.

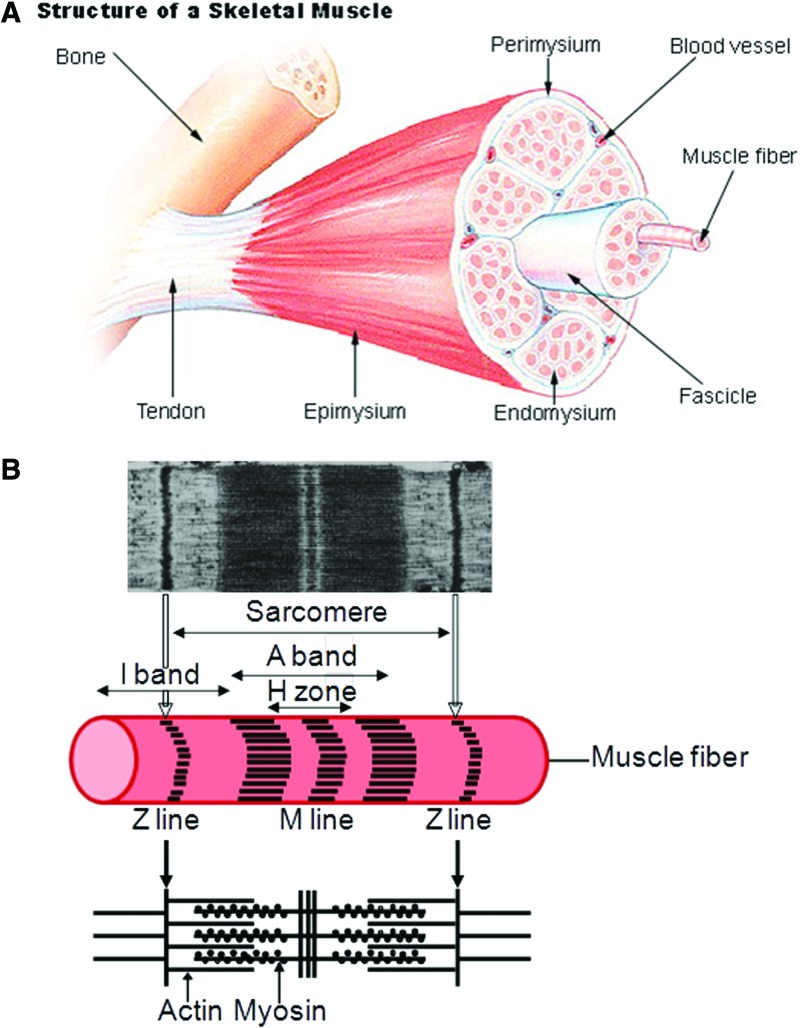

Muscle Tissue Organization

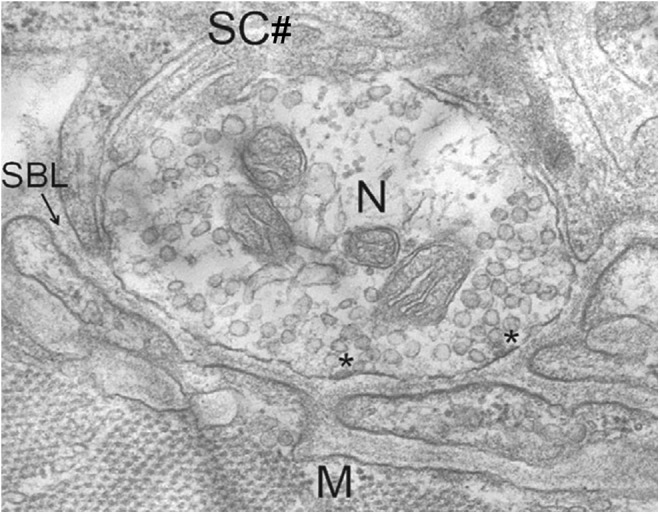

The human body has over 600 skeletal muscles that are linked to bones and are involved in anatomical position, locomotion, preemption, mastication, and other dynamic events. These muscles are comprised of multiple bundles of muscle fibers that are formed by the fusion of undifferentiated myoblasts into long cylindrical, multinucleated structures called myotubes (Fig. 2).14 Major components of the myotubes include the plasma membrane or sarcolemma, the cytoplasm or sarcoplasm, and the peripheral flattened multinuclei. The sarcoplasm is notably filled by myofibrils, which are composed of the cytoplasmic proteins myosin (thick filament) and actin (thin filament) in repeated units called sarcomeres that are aligned along the cell axis. Under a microscope, each sarcomere appears delimited by two dark lines (Z lines) of dense proteins. Between these two Z lines are two light bands (I bands) containing actin filaments, separated by a dark band (A band) containing myosin filaments that overlap each other. The A band has also a lighter central zone (H zone) that does not overlap with the I bands when the muscle is in relaxed state; the H zone is separated in two parts by a middle dark line (M line). As sarcomeres of different myofibrils are also aligned with each other in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells (but not in smooth muscle cells), the myofibers appear striated. When the muscle contracts, the actin filaments are pulled along the myosin filament toward the M line, and the overlapping area between the myosin and actin filaments increases, whereas the H zone decreases and the muscle becomes shorter.

FIG. 2.

Anatomy of a skeletal muscle and a sarcomere. (A) From SEER training on structure of skeletal muscle, U.S. National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute (12 July 2012). http://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/muscular/structure.html (B) Micrograph of a sarcomere adapted with permission from Sosa et al.14 Copyright © 1994, Elsevier, and schematic. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Other important components of this contractile machinery found in the sarcoplasm are the sarcoplasmic reticulum, where calcium ions are stored and used for the muscle activation; the T tubules, which are used as the pathway for the action potential; and proteins, such as troponin and tropomyosin, which are linked to the actin filaments to prevent their interaction with myosin filaments when the muscle is in a relaxed state. Skeletal muscles differ in their phenotypes, and muscle fibers in humans are classified into three categories (I, IIa, and IIx [or IIb]) according to their myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms.15 Type I fibers are red because of the presence of myoglobin. They have a high mitochondrial content and rely on oxidative metabolism to generate ATP. These fibers express slow-twitch MyHCs and are suited for endurance. Type II fibers are white because of the absence of myoglobin and rely on glycolytic metabolism to generate ATP. They express fast-twitch MyHCs and are suited for fast bursts of power. This difference in twitch speed between muscle fibers results not only from differences in MyHC protein isoforms, which induce a difference in sliding velocity between the actin and the myosin filaments in the sarcomeres, but also from Ca2+ sequestering components, such as sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases that are expressed as different isoforms in type I and type II fibers.16 Thus, the in vitro development of muscle tissue with high functionality and good contractibility requires mimicking of this muscular structure, particularly to generate aligned muscle fibers; therefore, we describe in the “Engineering of Skeletal Muscle Tissues In Vitro” section some useful methods to align myoblasts cultured in vitro, as this cell alignment is necessary to the formation of myotubes.

Engineering of Skeletal Muscle Tissues In Vitro

Although the first contractile skeletal muscle tissue from a chicken embryo leg was cultured in vitro by Lewis about hundred years ago,17 the challenge of building large-scale muscle tissue with functional properties has persisted. Since the late 1970s, many approaches and techniques have emerged to study the development of muscle tissues. Notably, Vandenburgh and Kaufman developed an in vitro model for stretch-induced hypertrophy of a skeletal muscle tissue construct embedded in a collagen gel.18 Later, in the early 1990s, the first three-dimensional (3D) muscle construct was grown in vitro by Strohman et al.,19 who grew a monolayer of myoblasts on a membrane that detached after differentiation and formed 3D contractile muscle tissue, which was later termed “myooids” by Dennis and colleagues.20 More recently, Lam et al. showed that aligned myotubes formed by the prealignment of myoblasts on a micropatterned polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer can be transferred from the PDMS substrate into a fibrin gel, thus allowing for the formation of a 3D free-standing construct with higher muscle fiber content and force production.21 The size of the construct did not exceed 1 mm in diameter because of the limited diffusion capacity in the tissue. Thus, the use of synthetic polymers and advanced patterning techniques has allowed SMTE to progress. Currently, micro- and nanofabrication techniques enhance the possibility to create tissues.22 When engineering a skeletal muscle tissue, one of the key points is to prealign the cells to obtain increased muscle fiber formation, as shown previously by Lam and colleagues.21 To this end, many techniques (for reviews on micro/nanofabrication see Ramalingam and Khademhosseini,23 Khademhosseini and Peppas,24 Zorlutuna et al.,25 and Ostrovidov et al.26), such as soft lithography,27 hot embossing,28 electrospinning,29 photolithography and solvent casting,30 passive or active stretching,31 and the use of electrical fields,32,33 have been applied to create an environment that induces cell alignment. In the following subsections, we review useful methods to align myoblasts in vitro.

Cell alignment by topography

It has long been known that cell behavior is influenced by surface features.34 Thus, numerous studies have focused on the effects of different topographical features, such as size and geometry, on the cellular response.35–38 Among these topographical features, parallel grooves are among the most-studied patterns to elongate muscle cells in one direction. The first studies aimed to determine how the cells sense their environment and what causes the cells to undergo alignment. Thus, grooved patterns with different widths and depths were tested. For example, Evans et al. generated micropatterned grooves with depths ranging from 40 nm to 6 μm and widths ranging from 5 to 100 μm on silicon substrates by etching with conventional photolithographic methods and studied myoblast direction and alignment along the grooves.39 They showed that shallow grooves with a depth of 40–140 nm did not significantly affect myoblast alignment, whereas significant cell alignment was achieved with deep grooves that had a width of 5–12 μm and a depth of 2–6 μm. Additionally, Clark et al. showed that nanosized grooves with a width of 130 nm and a depth of 210 nm also induced myoblast alignment.40 In addition, because they observed that myotubes with identical diameters formed in grooves with different widths, Clark et al. hypothesized that lateral fusion of myoblasts was not a possible mechanism in myotube formation. Therefore, they cultured myoblasts on ultrafine grating (grooves with a width of 130 nm and a depth of 210 nm and ridges with a width of 130 nm) that strongly aligned the myoblasts, and showed that myoblasts fused in end-to-end configurations.41

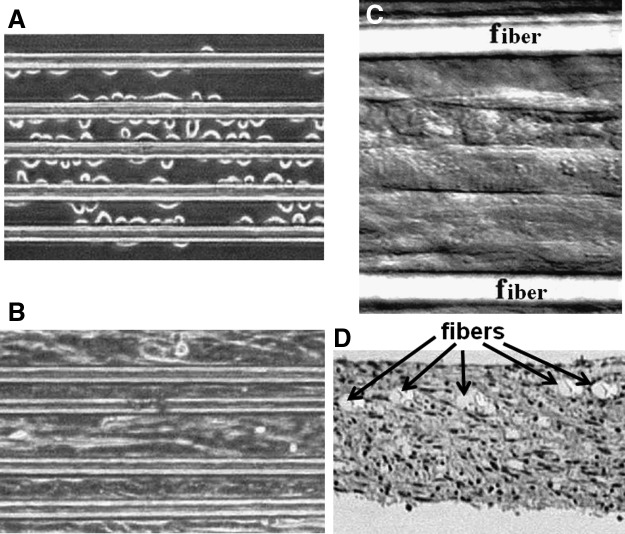

To easily fabricate groove/ridge micro- and nanopatterns without requiring a clean room, alternative methods to photolithography have also been used. Thus, since they contain nano/microgrooves, commercially CD-R and DVD-R in polycarbonate have been used for directing cell alignment or for patterning polymers.42,43 Abrasive paper has also been proposed to easily produce parallel grooves on a surface at low cost to direct the alignment of myoblasts.44 Similarly, Jiang et al. fabricated sinusoidal-wavy-grooved (size ranging between 0.1 and 10 μm) micropatterns on a PDMS surface by stretching a PDMS slab and then subjecting it to extended oxidation under low pressure before relaxing it. For this continuous topography without sharp edges, they showed that sharp-edge features were not necessary to induce contact guidance.45 Another study by Lam et al. focused on the effects of wave periodicity on C2C12 cells and showed that a wavelength of 6 μm was optimal to induce myoblast and myotube alignment.46 These topography–cell interaction studies opposed the theory proposed by Curtis and Clark, who suggested that cell guidance on groove-ridge patterns is mostly governed by groove depth.37,47 Although numerous studies have suggested that cells sense and grow on predefined topography, the mechanism by which the cells sense the topography is not well understood. However, filopodia are involved in this detection because they extend in front of the cells and probe the topographic features.48 This topographical surface guidance is the foundation of several approaches used for designing scaffolds in 2D and 3D. For instance, Neumann et al. used arrays of parallel polymer fibers with thicknesses of 10 to 50 μm and spacings of 30 to 95 μm to generate a scaffold for engineering a C2C12 myoblast sheet. They showed that by using this method, it was possible to generate a continuous contractile aligned muscle sheet with fiber spacing of up to 55 μm49 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

C2C12 cells cultured on an array of large fibers. (A) Thirty minutes after seeding. (B) Gaps between fibers were closed after 5 weeks of culture and a cell sheet was formed. (C) After 10 weeks in culture, myotubes were striated (DIC image). (D) Cross-section of the muscular tissue fixed and stained by hematoxylin and eosin. The fiber plane is in the upper section (scale bars for [A–D] 50 μm). Reprinted with permission from Neumann et al.49 Copyright © 2003, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

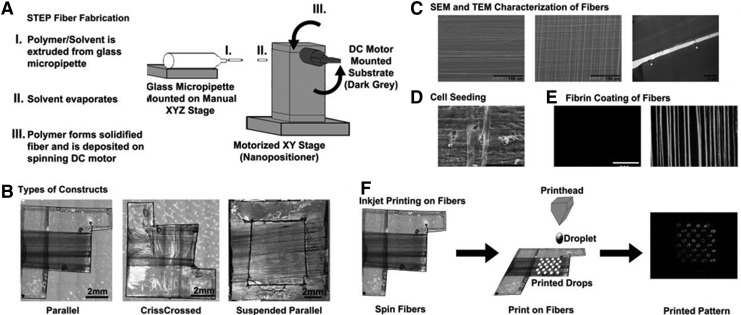

In another example, to build a muscle-tendon-bone tissue in one step, Ker et al. used a spinneret-based tunable engineered parameter technique to fabricate polystyrene fiber (655-nm diameter) arrays that they coated with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as fibronectin, and bioprinted with patterns of two different growth factors. By combining topographical and chemical cues to mimic the in vivo environment, they showed that although the fibers induced C2C12 cell alignment by topography, the localized presence of growth factors induced myoblast differentiation in tenocytes and osteoblasts, and the absence of growth factors enabled differentiation in myotubes50 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Fiber-fabrication procedure by Polystyrene Spinneret-based Tunable Engineered Parameter (STEP). (A) Schematic showing the building of fibers by STEP. (B) STEP fiber types that can be fabricated by one set of fibers running in a parallel manner (left), two sets of fibers running perpendicular to each other (middle), and one set of fibers running in a parallel manner with a hollowed-out support base (right). (C) SEM and TEM pictures used to quantify the STEP fiber diameter and length. (D) SEM image showing the cell attachment to the polystyrene STEP fibers. (E) Images in fluorescence of polystyrene STEP fibers coated with Alexa649-conjugated fibrin (right) and uncoated (left). (F) Polystyrene STEP fibers can be printed on by inkjet printing. (Scale bars: B, 2 mm; C, 100 μm and right photo 2 μm; D, 100 μm; E, 200 μm). Reprinted with permission from Ker et al.50 Copyright © 2011, Elsevier.

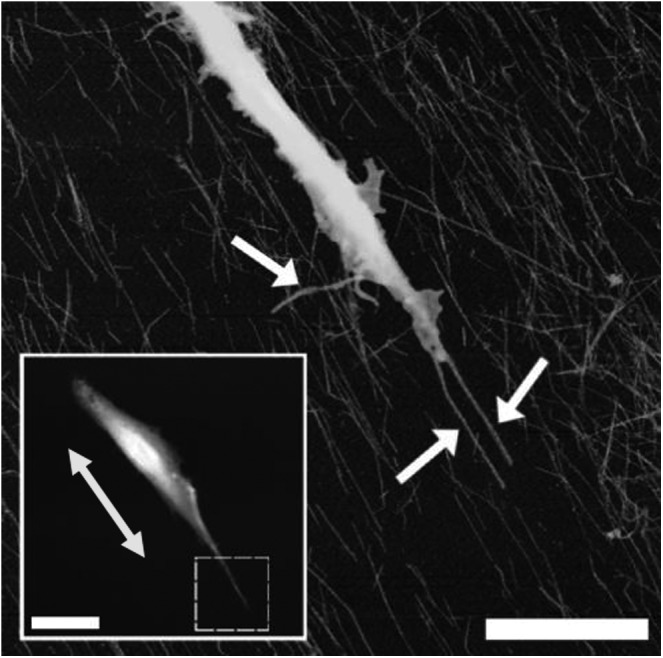

Nanotopography also greatly influences cell contact guidance.51 In groove/ridge patterns, the contact guidance cues are efficient in aligning cells for groove sizes up to 100 μm. With the development of methods to fabricate materials from micro- to nanoscale, new advancements of SMTE became available and materials with nanofeatures are of great interest. Indeed, cells in vivo evolve in an ECM environment, which comprises a material with nanoscale features that is composed of different proteins. For example, collagen fibrils found in the ECM usually have a length of ∼10 μm and a width of 260–410 nm.52,53 The fabrication of materials with nano-cues and nano-signals that are able to interact with cells and mimic the natural environment of the ECM can have tremendous applications in tissue engineering. Several studies have used columns, protrusions, pits, nodes, or nano-islands as substrates and have shown that small features, such as 11-nm columns, 35-nm pits, nanoposts (pointed columns), or 20-nm islands, promote cell adhesion, whereas increases in the size of these features decreases cell adhesion.54 Moreover, it has been shown that the symmetry of these features as well as the surface roughness also affects the adhesion of cells.55–58 Surface topography affects not only cell orientation and elongation but also the cell differentiation. For example, adult rat hippocampal progenitor cells cultured on a patterned polystyrene dish with 16-μm-wide grooves overexpressed neuronal marker (class III β-tubulin) when compared with smooth substrates.59 Electrospinning has also been used to fabricate aligned nanofiber scaffolds to induce the alignment of myoblasts.29,60–62 The 3D structure of the electrospun fibers resembles the physical structure of native collagen fibrils or ECM.63 However, although electrospun scaffolds are 3D structures, in many studies, the dense packing of fibers inhibits cell infiltration into the fiber network, and cells proliferate mostly on the top side of the electrospun fiber to generate a tissue similar to that formed using other 2D topographic substrates.64 Recently, direct electrospinning of a 3D aligned nanofibrous tube has been realized, promoting cell alignment and myotube formation.65 In another attempt to scale down the topography features, Dugan and coworkers employed oriented cellulose nanowhiskers with a diameter of 10–15 nm on a glass surface. They showed (Fig. 5) that myoblasts effectively sense the topography of such a surface and that myotubes resulting from myoblast fusion were nearly oriented in line with the direction of the cellulose nanowhiskers.66 This study clearly shows that cells are sensitive to topographical features, which affect cell orientation, shape, and differentiation.

FIG. 5.

Oriented cellulose nanowhiskers of 10–15-nm diameter were produced by spin-coating. The response of myoblasts to the surfaces was assessed by atomic force microscopy 12 h after seeding. The inset picture shows a large-scale image of the whole cell (inset scale bar=20 μm), whereas the yellow arrow indicates the direction of the nanowiskers. The main image shows a closeup scan of the area bounded by the dashed box in the inset picture (scale bar=5 μm), whereas the white arrows indicate filopodia. Reprinted with permission from Dugan et al.66 Copyright © 2010, American Chemical Society.

To mimic in vivo muscle tissue, engineering of a 3D structure from aligned myotubes is needed. Zhao et al. have shown that a multilayered construct of aligned myotubes can be obtained by seeding additional myoblasts on a first layer of aligned myotubes formed in a groove (2-μm width and depth)/ridge micropattern.38 In addition, Hume et al. recently showed that if C2C12 cells aligned well in small grooves (≤100 μm) and did not align in large grooves in 2D culture, then their behavior changed in 3D culture.67 Thus, C2C12 cells were able to align in larger grooves (width of 200 μm and depth of 200 μm) when layered into the grooves. This study highlights the importance of 3D cultures in tissue engineering applications.

In an attempt to generate 3D tissue cultures in an environment that allows cells to assume a shape and exhibit matrix adhesion similar to that of native tissues, hydrogels have been extensively studied.68 Hydrogels can be generated from synthetic (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol) [PEG]) or natural polymers (e.g., collagen, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid). To generate skeletal muscle tissue, myoblasts must proliferate, migrate, align, and fuse to form a functional construct. ECM-derived hydrogel-like collagen or fibrin gel contains fibrils. These tiny protein nanofibers play the role of natural 3D topographical cues to guide the cells.69,70 Thus, Lanfer et al. used a microfluidic device to create highly aligned type I collagen matrices and showed that myotube assembly and alignment were influenced by the topographical feature of collagen fibrils.71 Hydrogel molding was also considered for guiding myoblasts in a method developed by Bian and coworkers. In their work, a PDMS mold was used to cast cell-laden hydrogels resulting in myotube alignment depending on the geometry and size72 (Fig. 6).

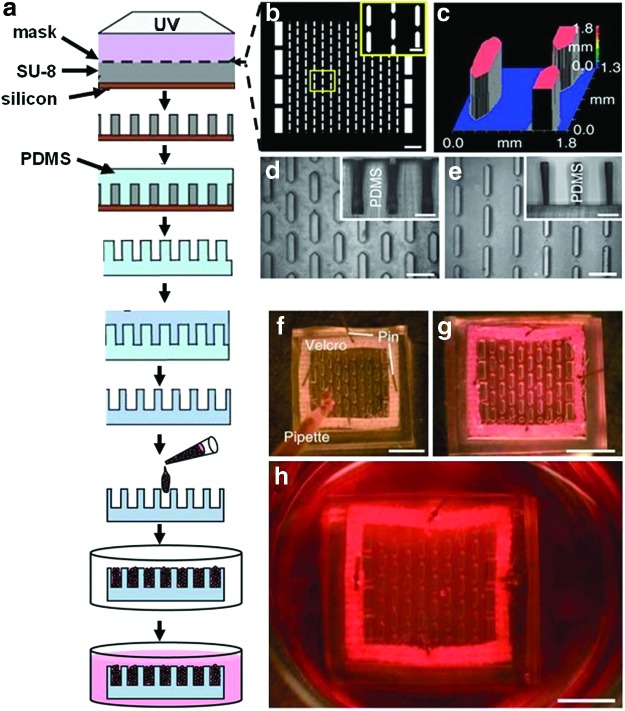

FIG. 6.

(a) A Silicon wafer coated with SU-8 was patterned by UV through (b) a photomask (scale bars=2 mm; inset=500 μm). (c) Optical profile of the master mold. (d) Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-negative replica (scale bars=1 mm; inset vertical cross-section 500 μm). (e) PDMS-positive replica (scale bars=1 mm; inset vertical cross-section 500 μm). (f) Cells in hydrogel prepolymer solution were poured in the PDMS mold and incubated at 37°C to allow (g) hydrogel polymerization. (h) The culture medium was then added and the cells were cultured for 2 weeks. The hydrogel was fixed on a Velcro frame (scale bars in f–h 5 mm). Reprinted with permission from Bian et al.72 Copyright © 2009, Nature Publishing Group. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

A composite 3D scaffold made of parallel glass fibers within a collagen gel has been used to direct the growth and differentiation of primary human masseter muscle derived cells.73,74 The effect of the cell density on the maturation and contractile ability of an engineered muscle in a collagen gel was also studied by the same group.75 In another study, gelatin, which is a hydrolyzed derivative of collagen, has been methacrylated to become photocrosslinkable. This acrylated gelatin showed promising aspects for supporting cell proliferation, and cell-laden photopatterned methacrylated gelatin was successfully used to direct, elongate, and align myoblasts in a 3D hydrogel environment76,77 (Fig. 7). These techniques rely on the limitation of cell migration by molding them in groove-like structures, which induced their alignment in a 3D environment improving their functionalities.

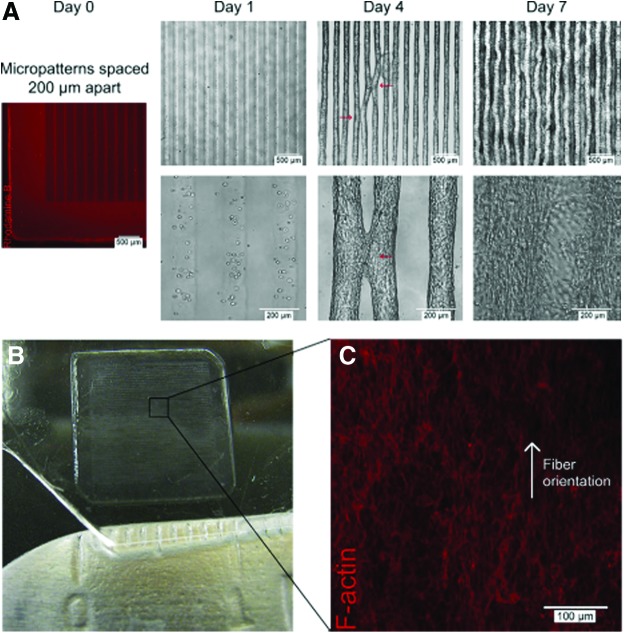

FIG. 7.

3T3 fibroblasts encapsulated in 5% GelMA hydrogels patterned into rectangular microconstructs [50 μm (w)×800 μm (l)×150 μm (h) with 200-μm interlines]. (A) Hydrogel stained with Rhodamine B showing initial microconstruct at day 0 and phase-contrast images of cell-laden microconstructs at days 1, 4, and 7 of culture. The red arrows indicate points of contact between neighboring lines at day 4 of culture, with tissue convergence at day 7 of culture. (B) Three-dimensional (3D) tissue construct (1×1 cm2) at day 7 of culture. (C) F-Actin staining showing the middle of the 3D tissue construct with aligned actin fibers. Reprinted with permission from Aubin et al.77 Copyright © 2010, Elsevier. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Cell alignment by surface patterning

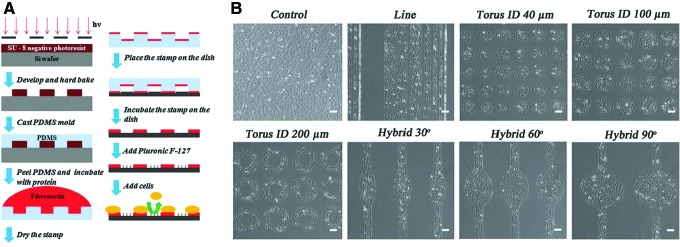

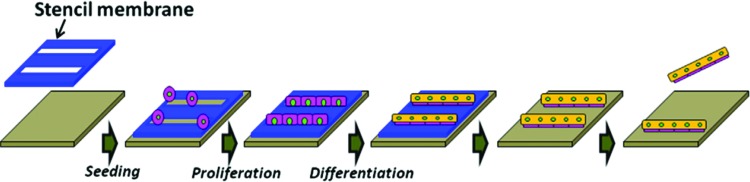

Surface patterning is a general term used to describe the modification of a biomaterial's surface by patterning techniques. Soft lithography, which was introduced by the Whitesides group in the late 1990s to facilitate microfluidic device fabrication and fast prototyping, has also been used to pattern surfaces.78 This technique is based on the use of an elastomeric master that is easy to mold or emboss and can be used directly as substrate for biological applications or as mold. Among the elastomers used, PDMS is the most popular elastomer for biological applications, and the construction of a PDMS master is related to another mold prepared by conventional photolithography approaches.79–81 Soft lithography is widely used for the patterning of cells and proteins through using patterning techniques such as microcontact printing, microfluidic patterning, and stencil micropatterning.23,82,83 To guide cells on a surface, patterning of ECM proteins, such as collagen, fibronectin, or laminin, is widely used, as is the printing of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) with cell-repellant molecules, such as PEG derivatives, poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide) (PEO-PPO) block copolymer, or copolymer surfactant with primary hydroxyl groups, thereby limiting the area where cells can settle. A combination of printed cell repellant and cell-adhesive molecules could also be used84–86 (Fig. 8). Another technique is showed by Shimizu et al., who used a stencil membrane to micropattern myoblasts and form a pattern of single myotubes87 (Fig. 9). Direct patterning of myoblasts by inkjet printing techniques has been also done to improve the cell alignment and tissue formation.88

FIG. 8.

Micropatterned substrate building process and cell culture. (A) Schematic showing the preparation of the micropatterned substrate. (B) Phase-contrast images of the different micropatterns with cells: lines of different widths (300 μm, 150 μm, 80 μm, 40 μm, 20 μm, and 10 μm), tori of different inner diameters (40 μm, 100 μm, and 200 μm), and hybrid patterns of different arc degrees (30°, 60°, and 90°), (scale bar=100 μm). Reprinted with permission from Bajaj et al.84 Copyright © 2011, Royal Society of Chemistry. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

FIG. 9.

Schematic showing the micropatterning of myotubes by the use of a thin PDMS stencil membrane. A BSA-coated membrane was attached on the surface of a Petri dish and C2C12 were seeded on the membrane. After culturing in differentiation medium, the membrane was peeled off under a microscope to free the micropatterned myotubes, which can be removed. Reprinted with permission from Shimizu et al.87 Copyright © 2010, Elsevier. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Cell patterning has been mostly used to study cell behavior, such as cell migration, proliferation, cell–cell interactions, and drug screening, in a 2D environment. However, this approach is also appealing for the creation of 3D tissue-like constructs via cell-sheet-based tissue engineering. Indeed, various methods exist for the harvesting of prepatterned cell sheets. For example, Nagamine et al. used a fibrin gel to embed aligned myotubes into a 3D hydrogel system.89 Similarly, Huang et al. transferred aligned myotubes from a parallel micropattern of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) to a type I collagen gel overlaid on the micropattern. After 3 days of culture, the collagen sheet was rolled around a biodegradable polymeric mandrel to fabricate a tubular muscle-like construct with aligned myotubes.90 Polymeric nanomembranes, with exceptional flexibility were also micropatterned by microcontact printing with lines of fibronectin plus multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) to enhance the cell alignment and myotube formation and then rolled up to fabricate a tubular structure.91 In an interesting study, prevascularized 3D muscle tissue was constructed by stacking multiple layers of endothelial cells sandwiched by myoblast sheets.92 Petri dishes covalently grafted with the temperature-responsive polymer poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) were used to harvest the different cell sheets, and the handling of the cell sheets was secured by a plunger coated with a hydrogel matrix. By patterning hydrophilic polymer on thermoresponsive surface and by using a plunger coated with gelatin to harvest the different cell sheets of human skeletal myoblasts, Takahashi et al. showed that an anisotropic cell sheet placed on the top of four random cell sheets stacked together induced the myoblasts and the ECM alignment in the whole construct.93 Recently, Guillaume-Gentil et al. described a method to fabricate and harvest micropatterned heterotypic cell sheets by local electrochemical dissolution of a polyelectrolyte coating94 (Fig. 10). Such methods introduce the possible creation of cocultured harvestable cell sheets and the growth of more complex tissue constructs via cell-sheet-based tissue engineering.

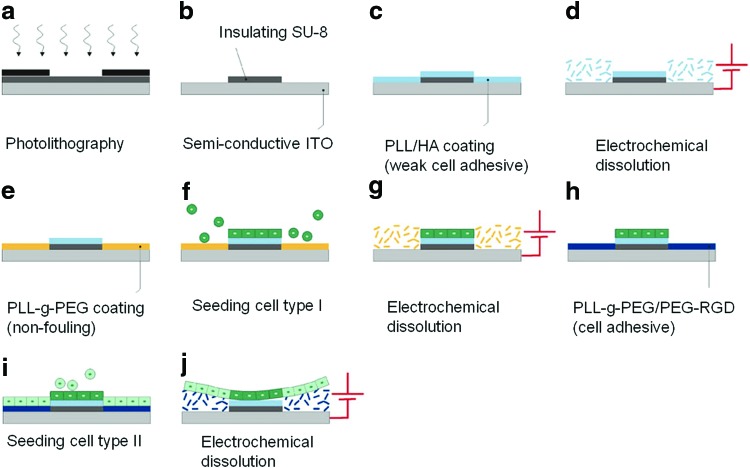

FIG. 10.

Micropatterning of heterotypic cell sheets. (a) Patterning of an SU-8 layer spin coated on an indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode by UV through a photomask. (b) After development, SU-8 micropatterns are formed on the ITO electrode. (c) The substrate is then coated with a weak cell-adhesive polyelectrolyte and (d) subjected to electrochemical polarization, which induced the dissolution of the polyelectrolyte only from the ITO regions. (e) The ITO regions are backfilled with a cell-repellent polymer PLL-g-PEG and (f) a first cell type is seeded whereas the nonadherent cells are washed away. (g) The PLL-g-PEG monolayer is then removed by a second electrochemical step. (h) The ITO regions are backfilled with PLL-g-PEG/PEG-RGD, which is a cell-adhesive monolayer. (i) The second cell type is seeded and the nonadherent cells are washed away. (j) After 1 day of culture, the PLL-g-PEG/PEG-RGD monolayer is dissolved by a final electrochemical step, which allows the whole cell sheet to detach. Indeed, due to their weak interaction with the substrate, the cells on weak cell-adhesive regions also detach easily. PEG, poly(ethylene glycol). Reprinted with permission from Guillaume-Gentil et al.94 Copyright © 2010, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Cell alignment by mechanical stimulation

Lack of stimulation and mechanical force causes muscle degeneration, as occurs in disabled individuals or during skeletal muscle atrophy in the microgravity of spaceflight. Although the role of mechanical stimulation has been widely studied in gene regulation, endogenous protein regulation, accumulation, and metabolic products,95,96 it has been less studied as a tool in SMTE. However, it has been reported that under continuous uniaxial strain, avian myoblasts and L6 rat skeletal muscle cells cultured on an elastic substratum differentiated into myotubes oriented parallel to the direction of strain, whereas under stretching/relaxation cycles, the myotubes were aligned perpendicular to the stretch direction.31,97,98 Other studies of myoblasts encapsulated in a collagen hydrogel and treated by continuous uniaxial strain also showed the formation of myotubes parallel to the direction of the strain.5,99,100 One hypothesis to explain the difference in the angle of cell and myotube orientation between cells cultured under continuous strain or under stretching/relaxing cycles is the appearance of micro-ripples or micro-cracks in the matrix or in the elastomer surface perpendicular to the stretch direction, as observed for PDMS surfaces treated with stretching/relaxing cycles.101 The passive tension observed during the coalescence of a collagen gel has also been used to align myoblasts between two posts to form aligned myotubes.3

Cell alignment by magnetic or electrical fields

Electrical fields are often used in single-cell manipulation and cell sorting techniques but less in the engineering of a whole tissue. Indeed, a cell placed in an alternating electrical field polarizes into a dipole and is subjected to a dieletrophoretic force F102 given by the formula:

|

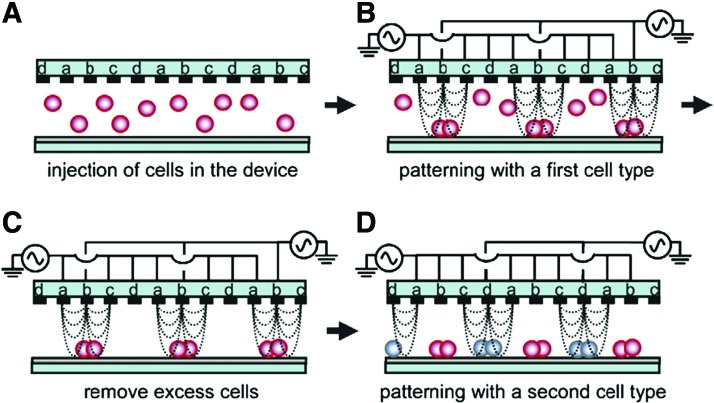

Where r is the radius of the cell, ɛm is the medium permittivity, ɛc is the cell permittivity, ∇E is the magnitude of the electrical field, and |(ɛc−ɛm)/(ɛc+2ɛm)| is the real part of the Clausius-Mossotti factor.103 If |(ɛc−ɛm)/(ɛc+2ɛm)|>0, then a positive dielectrophoresis (DEP) force F exists that induces the cell to move toward regions with a high electrical field. If |(ɛc−ɛm)/(ɛc+2ɛm)|<0, a negative DEP force F exists that repels the cell toward regions of low electrical field. As the magnitude of the DEP force F is inversely proportional to the electrode gap, the electrodes are usually designed to be close to each other to allow the induction of an electrical field of several hundred V/cm that is suitable for cell manipulation.104 Thus, DEP has been used to pattern several cell types for coculture and tissue engineering applications105–107 (Fig. 11).

FIG. 11.

Patterning of two different cell populations by dielectrophoresis (DEP). (A) An interdigitated array of four-electrode subunit was used to pattern cells. (B) By applying an AC voltage, the n-DEP force was induced and cells were directed toward weaker region of electric field strength. (C) Cells in excess were removed. (D) A second cell type was loaded into the device and guided to other areas by changing the AC voltage mode. Reprinted with permission from Suzuki et al.107 Copyright © 2008, Elsevier. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Ramon-Azcon and colleagues used DEP to pattern C2C12 myoblasts in a hydrogel matrix, which resulted in a highly aligned muscle tissue construct.32,33 MWNTs have also been included into hydrogel and aligned by DEP improving the hydrogel electrical conductivity and favoring the cell alignment and the myotube formation.108 Some notable characteristics of the DEP method include accuracy, high cell manipulation speed, and the ability to scale-up.109 It has also been shown that a static magnetic field alone can induce the alignment of L6 myoblasts.110 However, the mechanism underlying this phenomenon is not well understood. Yamamoto et al. reported that C2C12 cells were elongated along the axis of a magnetic field after endocytosis of magnetic nanoparticles.111 By using this method of magnetic-force-based tissue engineering,112 which promotes tissue organization under a magnetic field, Akiyama et al. fabricated 3D tissue architecture,113 whereas Yamamoto et al. fabricated 200-μm-thick skeletal muscle tissue.111,114 To fabricate a 1.9-mm-thick skeletal muscle tissue, Yamamoto et al. combined the application of a magnetic field to C2C12 cells loaded with magnetic nanoparticles to induce tissue organization with the use of cell culture in a perfused hollow fiber reactor that allowed the maintenance of high cell density by supplying oxygen and nutrients.115

Induction of Cell Differentiation from Myoblasts to Myotubes

Cell differentiation

Myogenesis is the differentiation process that drives the formation of multinucleated myotubes. However, cell proliferation and phenotypic differentiation are mutually exclusive events. Therefore, myoblasts have to exit the cell cycle to enter into myogenesis. During this process, mononucleated myoblasts, which have a spindle or a polygonal shape, migrate toward each other and aggregate. Following this cell adhesion, the myoblasts align in an end-to-end configuration41 by the parallel apposition of their membranes.116 Membrane fusion then occurs, and the cells fuse together to generate a multinucleated structure.117 Initially, myoblasts fuse with each other to form small nascent myotubes, which subsequently fuse with additional myoblasts to form large and mature myotubes.118,119 All of these successive events are regulated by numerous factors, such as transcription factors, and involve several protein regulatory mechanisms, which are discussed in the following subsections.

Transcription factors

Nuclear factor of activated T cell (NFAT) is regulated by calcium and is involved in the transcription of numerous cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα).120 Upon calcium activation, calcineurin dephosphorylates the NFAT protein, which translocates to the nucleus, binds to DNA, and actives gene transcription. Three isoforms of this protein (NFATc1, c2, and c3) are present in myoblasts, and their translocation to the nucleus occurs at different stages of myogenesis. Thus, NFATc3 is activated only in myoblasts, and NFATc1 and NFATc2 are activated in myotubes.121 NFATc2 is notably involved in nascent myotube formation and growth.122 Myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) include MyoD, myogenin, Myf-5, and MRF4 (also called Herculin or Myf-6),123 which are expressed exclusively in skeletal muscle. Each of these factors activates myogenesis and forcing their expression in a variety of nonmuscle cell types converts these cells into muscle cells.124 These factors are characterized by a 70-amino-acid sequence containing a basic helix-loop-helix structure (bHLH) that is a DNA-binding domain.125 Mutagenesis studies have shown that the HLH motif is required for dimerization, whereas the adjacent basic motif is involved in DNA binding and targets a CANNTG sequence known as the E-box.126 MyoD is a 318-amino-acid phosphorylated nuclear protein. MyoD and Myf-5 can functionally substitute for one another to activate the muscle differentiation program127 and play a crucial role in the determination and maintenance of myogenic identity. Both of them are able to activate their own transcription and to cross-activate the other MRFs. MyoD mRNA and Myf-5 mRNA are expressed before and after myoblast differentiation. When activated, MyoD induces cells to permanently exit the cell cycle by increasing the expression of p21, which is an inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks).128,129 If MyoD and Myf5 have been shown to specify the myogenic lineage in a redundant manner and therefore are involved in the generation of myoblasts, then Myogenin plays a major role in the differentiation of myoblasts into multinucleated myotubes and its expression marks the entry of myoblasts into the differentiation pathway.130 However, the trigger that switches cells from proliferation to differentiation remains unknown. Andres and Walsh have shown that myogenin is expressed early before cell cycle exit and that the next step into myogenesis involves an increase in the number of cells expressing myogenin and the cell-cycle inhibitor p21.131 Indeed, Cdks are enzymes that are involved in cell-cycle progression and their inhibition by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, such as p21 and p57, which act in a redundant way, induces G1/S transition arrest and cell cycle exit concomitantly with increased activity of retinoblastoma protein (Rb), which together with myogenin activates the differentiation.132 It has been shown that the differentiation of myotubes can be reversed in cells with low expression of myogenin, thereby inducing myotube dislocation into mononucleated cells capable of DNA replication.133 MRF4 is also able to induce myogenic differentiation.134 However, MRF4 is usually expressed during the later phase of myogenesis during myotube maturation.135 Gap junctions are present on myoblasts prior to myotube formation and disappear after cell fusion. Studies have shown that blocking gap junctions with a compound such as octanol not only impairs myoblast fusion136 but also inhibits the activation of myogenin and MRF4.137 The myocyte-specific enhancer factor-2 (MEF-2) is a nuclear factor that activates muscle-specific transcription and belongs to the MCM1, Agamous, Deficiens and Serum response factor (MADS) box family of transcription factors.138 The MADS-box is a motif of 57 amino acids that is localized at the N-terminus of MEF-2 members and is a DNA-binding domain. It is located adjacent to a sequence of 29 amino acids referred to as the MEF2 domain that reinforces DNA binding and dimerization.139 In vertebrates, MEF-2 members include MEF-2 A, MEF-2 B, MEF-2 C, and MEF-2 D, all of which bind to an A+T-rich DNA sequence [CTA(A/T)4TAG].140 The MEF-2 family cooperates with the MRF family in the activation of muscle gene expression via a direct interaction between the respective DNA-binding domains, which results in a protein–protein association that synergistically increases the transcription and myogenic activity of MRF members.141–144

Other proteins that regulate myogenesis

Because myogenesis is regulated by a complex signaling pathway with multiple entry points and steps, many extra- and intra-cellular molecules and proteins positively or negatively affect this pathway. For example, growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), are potent inhibitors of myoblast differentiation.145,146 FGF impairs the binding of myogenic helix-loop-helix proteins to DNA by inducing the phosphorylation of their basic region by protein kinase C (PKC).147 TGF-β inhibits the activity of myogenin and MyoD without affecting their ability to bind DNA.148 It has been shown that TGF-β can induce the translocation of MEF-2 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, thereby preventing it from participating in an active transcriptional complex.149 Table 1 depicts some of the molecules involved in the regulation of myogenesis,122 and we suggest that readers refer to other articles for detailed examples of various signaling pathways involved in myogenesis.150–153

Table 1.

Molecules Acting on Mammalian Myogenesis

| Molecule name | Effect on | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane proteins | ||

| Integrins (VLA-4, β1), integrin receptor VCAM-1 | Myoblast fusion | 384 |

| Nephrin | Myotube accretion | 385 |

| K+ ion channel, T-type Ca2+ channel | Intracellular Ca2+ | 386,387 |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor | Myoblast differentiation | 388 |

| Protein GRP94 | Myoblast fusion | 389 |

| ADAM 12, Calveolin-3 | Myoblast fusion | 384,390 |

| Notch receptor | Satellite cell regulation | 327,391 |

| Mannose receptor | Myotube accretion | 119 |

| Intracellular proteins | ||

| Calpain, Calmodulin | Myoblast fusion | 392 |

| Calcineurin | Myoblast recruitment | 393 |

| AMPKinases | Protein catabolism | 187,394 |

| NFATC(1,2,3) | Gene activation | 394 |

| Yap | Hippo signaling | 395 |

| MAP Kinases | MEF2, stress signaling, activator mTORC1 | 150,185 |

| TSC1-TSC2 | mTORC1 inhibitor | 167 |

| mTOR | Regulation protein anabolism | 166 |

| FoxO/Smad | Protein catabolism | 176 |

| Extracellular factors | ||

| PGE 1, PGF2α, arachidonic acid | Myoblast fusion | 159,396 |

| IL-4, IL-6, LIF | Myoblast fusion, satellite cells | 397 |

| Ca2+ | Signaling pathway | 387 |

| Cathepsin B | Autophagy | 398 |

| IGF-1, Insulin, Androgen, GH | Protein anabolism | 399 |

| Myostatin, glucocorticoids | Protein catabolism | 227,400 |

| NO | Regulation satellite cell, myoblast fusion | 401 |

Reprinted and adapted with permission from Horsley and Pavlath.122 Copyright © 2004, S. Karger AG Basel.

Molecular induction of myoblast differentiation

Serum deprivation and other biochemical inductions

Myoblast differentiation can be molecularly induced by the absence of inhibitory molecules or by the presence of stimulatory molecules, and the surface chemistry of the substrate on which cells are cultured also plays a key role. Thus, serum deprivation is often used to induce myoblast differentiation into myotubes. Indeed, for myoblasts, the decision to proliferate or to differentiate is determined by the presence or the absence of serum. Among the different factors that downregulate the MRF members, Id (for inhibitor of DNA binding) is an HLH-protein that has the HLH motif but lacks the adjacent basic motif involved in DNA binding.154 Id is expressed at a high level in proliferating cells and is downregulated by serum starvation.155 By forming nonfunctional heterodimers with MRF members, Id impairs their ability to bind DNA.156 The expression of several genes, including c-Fos and c-Jun, is also rapidly induced by serum and represses the transcriptional activation induced by myogenin and MyoD.147 Another effect of serum deprivation is cell-cycle arrest via Cdk inactivation.132 In contrast, because myogenesis is regulated by a complex signaling pathway as described just now, the addition of certain molecules or proteins into the culture medium may induce or favor myoblast differentiation. For example, by using the nitric oxide (NO)–generator DETA-NO, Pisconti et al. showed in vitro in C2C12 cells and in vivo in mice that NO via cGMP induced the generation of follistatin (FST), which induces myoblast fusion.157 Similarly, it has been shown that myoblasts express netrin-3 and its cell-surface receptor neogenin. Treatment of C2C12 cells with recombinant netrin induces myotube promotion and NFAT activation, which results in the formation of larger myotubes when compared with controls.158 Arachidonic acid supplementation also enhances myotube growth.159 Cytokines and growth factors may also activate the JAK-STAT pathway regulating positively (or negatively) the myogenic differentiation.160 Material surface chemistry and ECM may also favor myoblast differentiation. Indeed, in vivo, muscle fibers are wrapped by basal lamina, which is an ECM that contains mainly laminin, collagen IV, collagen I, and proteoglycans. As ECM is a key component of the cellular environment, some research groups have used directly the ECM extracted from muscles to improve cell culture and differentiation in 2D systems,161,162 whereas others have used a 3D hydrogel environment mixed with different ECM components.163 ECM acts on cell-cycle progression and cell differentiation through the binding of transmembrane integrin receptors and the activation of signaling cascades. Chemical patterning of the material surface by SAMs is also a versatile technique for surface modification23,164 that can be used to induce cell differentiation. Indeed, SAMs and notably alkanethiols, which are molecules composed of a head group with a sulfhydryl (-SH) and a long alkyl tail that can be functionalized, form spontaneously ordered monolayers through the adsorption of their head group to the surface of the substrate. By using fibronectin-coated SAM surfaces to present defined functional chemicals to C2C12 cells, Lan et al. showed higher myoblast differentiation on surfaces with functional groups following the order OH>CH3>NH2=COOH, which was correlated with higher α5β1 integrin binding.165

Cellular regulation of protein anabolism

In cells, the protein homeostasis is balanced by protein synthesis and degradation to sustain anabolic processes and energy production. This important regulation is mainly controlled by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway.166 mTOR is a 289-kDa serine/threonine kinase that forms two different complexes 1 (mTORC1) and 2 (mTORC2), respectively, sensitive and insensitive to rapamycin.167 The mTORC1 complex is formed by mTOR, the regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), the mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8 (mLST8, also known as G protein β-subunit-like protein [GβL]), and the proline-rich Akt substrate-40 kDa (PRAS40), whereas mTORC2 complex is formed by mTOR, the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), and mLST8.168,169 When activated, mTORC1 promotes the cell growth by enhancing the protein synthesis through the phosphorylation and activation of the ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K), forms 1 (S6K1) and 2 (S6K2), activating downstream the RNA translation.170 Moreover, phosphorylated mTORC1 induces also the phosphorylation and inhibition of the translational repressor named eukaryotic initiation factor binding protein 1 (4EBP1) by inducing its dissociation from the eukaryotic translation initiation factors 4E (eIF4E) that assembles with eIF4G and eIF4A to form the trimeric complex eIF4F initiating the RNA translation.171 Upstream, mTORC1 is regulated by the tuberous sclerosis complex also named hamartin-tuberin complex (TSC1-TSC2), which inhibits mTORC1 by stimulating the GTPase activity of the protein Ras homologue enriched in brain (Rheb) via the GTPase activating protein (GAP) domain of TSC2, increasing the conversion of Rheb-GTP into Rheb-GDP.167 The TSC1-TSC2 complex is a hub of signal transduction modulating mTORC1 activity in function of the signals received from a large number of different signaling pathways. This allows mTORC1 to sense among different signals the level in amino acid, in energy (ATP), in oxygen, and in growth signaling for regulating the cellular growth.

Upstream to TSC1-TSC2, one of the important signalization pathways transduced the signal by Akt also named protein kinase B (PKB). Akt is a serine/threonine kinase that has three isoforms, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3,172 and is a central node of signalization, notably by growth factors.173 Akt acts positively on the protein synthesis regulation by directly phosphorylating TSC2 inhibiting the GAP activity of TSC1-TSC2 complex toward Rheb, which allows the accumulation of Rheb-GTP and the activation of mTORC1.174 Moreover, Akt can also inhibit the protein degradation by phosphorylating members of the forkhead box O (FoxO) family of transcription factors impairing them to translocate into the nucleus. The FoxO proteins control the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome systems, which are two main proteolytic pathways in cell.175,176 Therefore in muscle, the activation of FoxO1 and FoxO3 induces their translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus to promote the transcription of genes, such as the muscle atrophy F-box also named atrogin1 (MAFbx),177 the muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1),178 and the regulated in development and DNA damage response-1 (REDD1),179 inducing muscular atrophy. Upstream, Akt is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), which upon activation recruits its substrate phosphatidylinositol-4-5- biphosphate (PIP2) to generate the second messenger phosphatidylinositol-3-4-5- triphosphate (PIP3), which in association with the 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) activate Akt.180

However, other signaling pathways, such as the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, or the 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, can act positively or negatively on the TSC1-TSC2 complex.181 The ERK pathway activates mTORC1 by phosphorylating and inhibiting TSC2 via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase.182 ERK also upregulates the protein anabolism by phosphorylating and inhibiting FoXO3a protein, which is then degraded via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway.183 The P38/MAPK is involved in proinflammatory cytokines and other stress signals.184 The p38/MAPK pathway activates mTORC1 by inhibiting the TSC1-TSC2 complex via the phosphorylation of TSC2.185 The AMPK pathway acts as a cellular energy sensor.186 In low-energy (intracellular ATP) status, 5′ adenosine monophosphate (AMP) level increases and activates AMPK. To increase the energy production via catabolic processes, AMPK directly phosphorylates TSC2 and Raptor impairing mTORC1 to phosphorylate its substrate and to activate the protein synthesis pathway.187,188 The level of oxygen can also be sensed through the AMPK pathway since in hypoxia condition the ATP level will be reduced. Another mechanism involves the activation of TSC2 due to its dissociation from the inhibitor proteins 14-3-3 after the binding of REDD1, which is upregulated under hypoxia condition.189 Other signaling mechanisms have also been observed. Thus, the TNFα phosphorylates TSC1 via the inhibitory κB kinase β (IKKβ) enhancing the dissociation and inactivation of the TSC1-TSC2 complex, which activates the mTORC1 pathway and the protein synthesis.190 The glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) inhibits mTORC1 by phosphorylating and activating TSC2 via AMPK. However, Wnt signaling inhibits the phosphorylation and activation of TSC2 by the GSK3 that upregulates mTORC1.181 Thus, important cell signaling networks are complex, containing several points of regulation, signal divergence, and crosstalk with other signaling cascades.

Muscle anabolism induced by growth factors

Muscle growth is regulated by hormones, such as growth hormone (GH), insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) and 2 (IGF-II), testosterone, and 5-α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT).191,192 It is well known that testosterone injection favors protein synthesis, whereas androgen deficiency induced muscle atrophy, reduction of IGF-1 level, reduction of muscle androgen receptor (AR) expression, and increase of fat store.193 Classically, androgens like testosterone mediated their effects via the AR.194 AR is a 110-kDa ligand-inducible transduction factor localized in the cytoplasm complexed by heat shock proteins (e.g., HSP 90 and HSP 70) and other chaperones.195 Upon ligand binding, AR is released from its chaperones, translocates to the nucleus, binds to the androgen-responsive elements, and actives directly, or indirectly via the recruitment of coactivators or corepressors, the gene transcription.196 This mechanism of signalization defined the genomic pathway. However, testosterone may also act faster trough nongenomic pathways involving surface membrane receptors.197,198 Thus, in the AR-negative rat L6 cell line, testosterone signaling involves a G-protein-coupled receptor with increase of intracellular calcium (Ca2+) acting as second messenger, and inducement of the cell proliferation via the PKC and ERK, while the cell differentiation was induced through the protein kinase A (PKA).199 Testosterone signal can also activate the MAPK pathway via the tyrosine kinase Src interacting with AR or the epidermal growth factor receptor.200–202 AR has also been shown to interact directly with the p85α subunit of PI3K to activate the PI3K/Akt pathway.203 Since AR can activate numerous signaling pathways, the development of AR ligands dissociating the anabolic effects from the androgenic effects of androgens, named selective androgen receptor modulators, is an important direction of research for therapeutic applications.194 Recent studies have shown that the anabolic effect of testosterone on muscle is transduced via the Akt/TSC2/mTORC1 pathway previously described.204,205

Insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II are produced by the liver under the stimulation of GH and have also an anabolic effect on muscle.206 After binding its receptor (IR) insulin activates the insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1) by tyrosine phosphorylation, which acts as docking site for proteins with Src homology 2 (SH2) domains, such as the P85 subunit of PI3K. This leads to the generation of the second messenger PIP3 and the activation of Akt/TSC2/mTORC1 pathway resulting in anabolic effect on muscle.167,175 However, a feedback mechanism exists to regulate the insulin signaling since the activation of S6K1 by mTORC1 induces the serine/threonine phosphorylation of IRS-1 reducing its stability.207,208 It has also been shown that insulin activated the phosphorylation of PRAS40 by Akt impairing its inhibitor effects on mTORC1.209

IGF-I and IGF-II are also important regulators of muscle mass.210 As insulin, they can in addition be produced by muscles and act in an autocrine/paracrine fashion. Similarly, they signal through the PI3K/Akt/TSC2/mTORC1 pathway but via their respective receptors IGF-IR and IGF-IIR.197,211,212 A negative autoregulatory loop of myogenesis has also been observed, since IGF-I can also activate the phospholipase C gamma through the PI3K pathway promoting the release of calcium from the intracellular stores, which induces the transcription of myostatin via calcineurin/NFAT pathway.213,214 During myogenesis, it has been shown that IGF-II auto-upregulates its gene expression via PI3K/Akt and P38 MAPK pathways, while downregulates IGF-I gene expression through mTOR.215 Interestingly in a point of view of biomaterial engineering, the focal adhesion kinase is required for the anabolic signal of IGF-I mediated through TSC2/mTOR/S6K1 pathway.216,217 Under exercise (mechanical or electrical stimulation), human muscles express spliced variants of the IFG-I gene that produce three isoforms of IGF-I.218 One isoform is IGF-IEa similar in action to the IGF-I produced by the liver, the second is IGF-IEb, whereas the third one is IGF-IEc, also named mechanogrowth factor (MGF), containing an E domain of 49 bases that modulates the signalization.219–221 IGF-IEa has been involved in the promotion of myoblast differentiation222 whereas MGF has been shown to recruit and to stimulate the proliferation of satellite cells (SCs) in correlation with the activation of the ERK pathway.223,224 The IGF-I signaling pathway crosstalks with the androgen signaling pathway since androgens increase the IGF-I level in serum and the IGF-I mRNA expression in muscle.193,225

Muscle catabolism induced by myostatin

In cells, the protein catabolism is secured via both the ubiquitin proteasome system and the autophagy/lysosome pathway with the activation of FoXO, NF-κB, and Smads transcription factors, whereas the protein anabolism is secured by the PI3/Akt/mTORC1 pathway.226,227 Myostatin or growth differentiation factor 8 (GDF-8) belongs to the TGF-β family, which are known inhibitors of myogenic differentiation and muscle growth.228 Myostatin is secreted by muscle and acts as an autocrine/paracrine fashion inhibiting myoblast differentiation, and maintaining SCs quiescents.229 After cleavage of the promyostatin complex, the mature myostatin binds to the transmembrane receptor activin receptor type IIB (ActRIIB), which recruits the type 1 transmembrane activin receptor-like kinase 4 or 5 (ALK4 or ALK5).230 This induces the phosphorylation of Smad proteins (Smad name comes from mothers against decapentaplegic) 2 and 3, and the recruitment of Smad 4 to form a complex Smad 2,3,4, which translocates from the cytosol to the nucleus and actives the gene transcription of atrophy-related genes or “atrogenes,” such as Murf-1 an Atrogin-1.227 As there is a balance between protein catabolism and protein anabolism, if the protein catabolism is enhanced then the protein anabolism is decreased and vice versa. Thus, myostatin inhibits the Akt/mTORC1/S6K and the p38/MAPK pathways, whereas it enhances the FoXO protein activity and the IκBα/NF-κB pathway.213,231 Inhibition of myostatin signaling allows the rescue of muscle loss. FST is a secreted glycoprotein that antagonizes members of the TGF-β family like myostatin232 and rescues impaired myoblast differentiation by myostatin.233 The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α is induced in muscle by exercise and favors mitochondrial genesis, resistance to muscle atrophy, and endurance.226 A spliced variant, PGC-1α4, also induced by exercise represses myostatin expression and favors hypertrophy by inducing IGF-I.234 It has also been shown that a combination of micro-distrophin gene replacement and FST restored muscle function in dystrophic mice.235 Indeed, myostatin upregulation has been observed in many diseases involving muscle loss, such as muscular dystrophy, sarcopenia, and cancer cachexia. Therefore, targeting myostatin with myostatin inhibitors for pharmacological applications is interesting.236,237

Electric and magnetic induction of myoblast differentiation

Mechanical and electrical stimulation are linked to muscle tissue formation. In the laboratory, an electrical stimulator can be used to easily mimic neuronal muscle stimulation with controlled parameters.238 In one example, Flaibani et al. applied 3-ms pulses with an amplitude of 70 mV/cm for 30 s to muscle precursor cells cultured on a micropatterned poly(L-lactic acid) membrane.239 They observed an increase in myotube density with a 30% increase in the release of nitrite (NO2−), which is a signaling molecule that is involved in myoblast fusion and myotube growth.157 Kawahara et al. applied 2-ms pulses of 50 V for 5 min/day to L6 rat myoblast cultures and observed accelerated myotube differentiation with the formation of thick myotubes followed by contracting striated muscle cells.240 The electrical stimulation was achieved by plunging electrodes into the culture medium. The drawback of this method is that most of the current lines cross under the culture medium rather than under the cells. In addition, electrolysis and the release of toxic products in the medium may result from this type of setup and should be avoided. Thus, to focus the current toward the myotubes, Kaji et al. cultured C2C12 cells on a conductive porous membrane and adopted a vertical setup for the electrodes.241 To protect the cells, Nagamine et al. transferred cultured myotubes to a fibrin gel, which they placed on microelectrode arrays for electrical stimulation (amplitude 2 V, duration 3 ms, frequency 10 Hz, train 1 s, and interval 10 s). The fibrin gel had been previously coated with a conductive polymer to improve interfacial electrical capacity.89 Other groups have also opted to use electrically conductive polymers to provide a matrix environment with safer electrical stimulation for the cells. In such cases, the cells can be encapsulated in the conductive polymer, seeded on the conductive polymer, or encapsulated in a polymer placed on electrodes. Thus, Sirivisoot and Harisson studied the formation of myotubes on electrically inductive composite scaffolds generated from electrospun polyurethane (PU) and carbon nanotubes.242 They showed that increased myotube formation was correlated with increased electrical conductivity because of the presence of carbon nanotubes. Also, Sekine et al. printed poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) electrodes on an agarose hydrogel and electrically stimulated contractile myotubes embedded in a fibrin gel deposited on the PEDOT/agarose sheet,243 whereas Ido et al. embedded PEDOT electrodes in a hydrogel.244 In another strategy, Mawad et al. combined the advantages of hydrogels (e.g., mechanical properties, hydrated environment, and biocompatibility) and conducting polymers to build a conducting polymer hydrogel on which C2C12 cells proliferated.245 Ku et al. electrospun a blend of polycaprolactone with polyaniline to combine the topographical constraint of aligned fibers with electrical conductivity and observed a synergistic effect on myotube formation.246

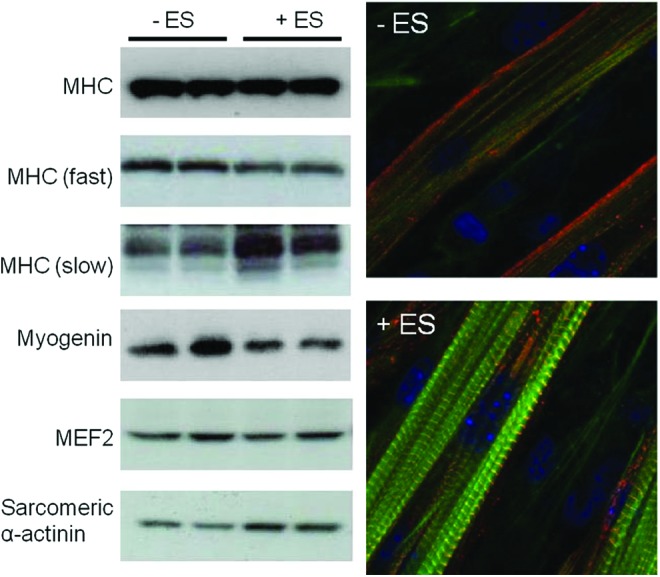

Electrical stimulation not only increases the myotube density by increasing the speed of formation but also changes the nature of the muscle fibers and acts at the molecular level of muscle fiber formation. For example, after 8 days of conventional differentiation, C2C12 myotubes lacked spontaneous contractibility because of negligible sarcomere architecture. Fujita et al. used electrical pulses to study the effects of Ca2+ oscillation on the assembly of functionally active sarcomeres.247 They observed an increase in striated myotubes that peaked at 2 h and then decreased during stimulation with a 24-ms electrical pulse of 40 V/mm at 1 Hz. When they applied a lower-frequency signal (0.1 Hz), the striation was delayed and peaked at 12 h of stimulation. When they applied a high-frequency signal (10 Hz) for 2 h, they did not induce sarcomere assembly and did not observe contractile activity. This electrically induced contractile activity appeared to be mediated through the protease activity of calpain and also involved ECM-integrin engagement. Another study248 (Fig. 12) by the same group showed that electrical stimulation induced a switch from fast MyHC chain (type II) to slow MyHC chain (type I); consequently, the muscle fiber phenotype changed under stimulation.249

FIG. 12.

Effects of electrical stimulation on muscular protein and sarcomere development. C2C12 myotubes were stimulated 24 h with electrical pulses (40 V, 1 Hz, 2 ms duration). The cell lysates were analyzed by western blot (left) and cells were fixed (right) and stained with DAPI for nucleus (blue), anti-sarcomeric α-actinin antibody for sarcomeric α-actinin (red), and phalloidin for MHC (green). Reprinted with permission from Nedachi et al.248 Copyright © 2008, The American Physiological Society. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Some studies have also focused on the effects of combinations of stimulation types applied to cells. For example, Liao et al. combined mechanical and electrical stimulation by culturing C2C12 cells on PU mats with different diameters and fiber orientations under stretching and 10-ms electrical pulses of 20 V.250 They showed a net improvement of myotube striation and contractile protein (myosin, MyHC, and α-actinin) secretion under electromechanical stimulation but did not observe a significant benefit of bistimulation over monostimulation (mechanical or electrical only). Magnetic induction has also been used to induce myoblast differentiation. For example, Yuge and Kataoka introduced magnetic microparticles (0.05–0.1 μm Ø) into the cytoplasm of rat myoblast L6 cells by electroporation and then cultured the cells in magnetic fields of 0.01, 0.03, or 0.05 T.251 They observed that cells aligned and elongated along the N-S direction of the magnetic lines and that the formation of myotubes accelerated with the intensity of the magnetic field. Complete differentiation was obtained with striated myotube formation, and the myotube size also increased. Another study showed that a magnetic field of 80 mT orthogonal to the cell plane promoted myogenic differentiation and myotube hypertrophy without requiring other treatments, such as the introduction of magnetic particles into cells.110 Interestingly, when cells were treated with 5 μg/mL of TNFα, which is an inhibitor of myoblast differentiation,252 the exposure of cells to the magnetic field restored the myogenic differentiation. Clearly, electrical stimulation with or without other types of stimulation has important effects on myoblast differentiation and allows faster myotube formation, higher myotube density, increased myotube size, and a higher degree of myotube maturation.

Mechanical induction of myoblast differentiation

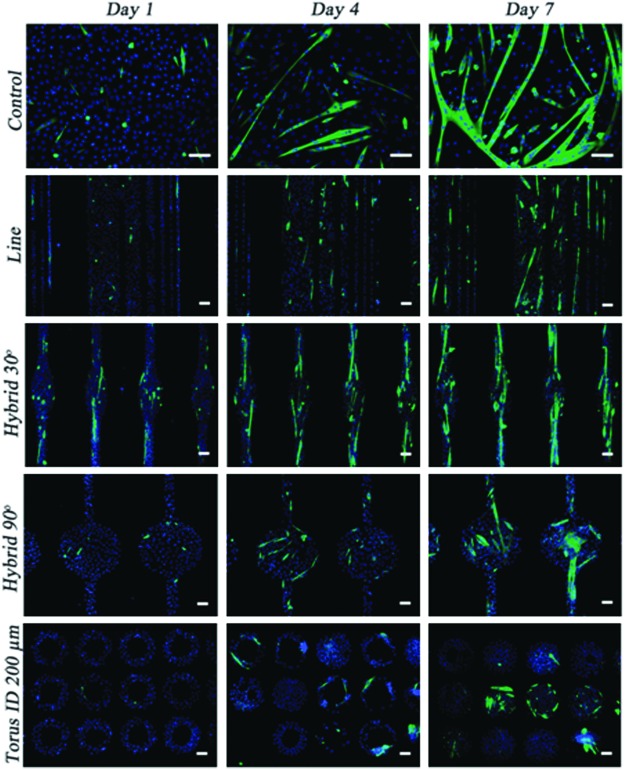

It is known that in body-building, muscular work through resistance training results in muscles with increased diameter. Therefore, it is interesting to analyze the effects of mechanical stimulation on myogenesis. Cells can be mechanically stimulated by topography, the stiffness of the material, and stretching. We previously described (“Cell alignment by topography” section) the degree to which topography can influence cellular alignment. Because myoblasts fuse mainly in an end-to-end configuration, cellular alignment seems to be required to obtain myotubes. Curiously, when Charest et al. analyzed the differentiation of C2C12 cells cultured on topographic patterns consisting of embossed ridges and grooves or arrays of holes with sizes ranging from 5 to 75 μm on polycarbonate coated with SAM and fibronectin, they concluded that the topography strongly influenced myoblast alignment but had no effect on the differentiation of the myoblasts.253 Their analysis, however, was mainly based on the measurement of sarcomeric myosin expression, and no images of myotubes were presented. In contrast, Bajaj et al. showed that the geometrical cues of a substrate significantly affect myoblast differentiation.84 They cultured C2C12 cells on dishes with different geometrical fibronectin coatings for 1 week and observed that myotubes with a hybrid line-torus shape had a two- and threefold increase in their fusion index when compared with myotubes on line and torus patterns, respectively (Fig. 13).

FIG. 13.

Topographical effects on C2C12 differentiation and myotube formation at different days in differentiation culture medium. Cells were cultured on unpatterned (control) and patterned substrates with different shapes (scale bar=100 μm) and stained with DAPI for nucleus (blue) and anti-MHC (green). Reprinted with permission from Bajaj et al.84 Copyright © 2011, Royal Society of Chemistry. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Similarly, when Aviss et al. prepared a scaffold of aligned poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) fibers by electrospinning and cultured C2C12 cells for 14 days, they initially observed cell alignment with the fiber axis after 30 min of culture, followed by cell differentiation into long multinucleated myotubes aligned along the fibers.29 Our group also showed that topographical features can favor myoblast differentiation into myotubes.254

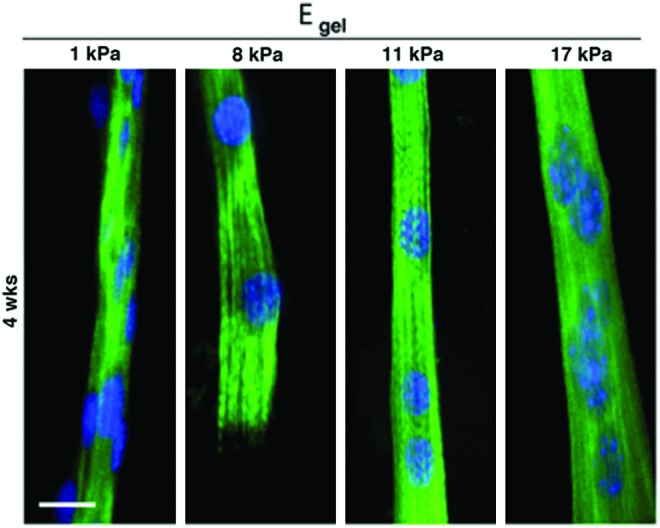

The stiffness of the material is also an important parameter in biomaterial and tissue engineering. Indeed, many studies have shown that on a material with different degrees of stiffness, cells migrate toward locations with the preferred stiffness.255 Engler et al. studied the effect of material stiffness on myoblast differentiation by culturing C2C12 cells on collagen-micropatterned polyacrylamide (PA) gels with different degrees of stiffness for 2 and 4 weeks.256 Although all cultures formed myotubes, myotubes only fully differentiated and reached myosin striation on gels of intermediate stiffness (8–11 kPa) (Fig. 14). The plot of material stiffness versus myotube striation fitted a Gaussian curve with an optimal modulus of 12 kPa that maximized myosin striation, whereas myotubes on gels with low (<5 kPa) or high stiffness (>17 kPa) had only poor or no striation. This optimal modulus value closely matched the elasticity of C2C12 myotubes, which is 12–15 kPa,257 and the native skeletal muscle tissue stiffness value, which is 12±4 kPa,258 as measured by atomic force microscopy on extensor digitorum longus muscles harvested from C57 mice.

FIG. 14.

Stiffness effects on myotube striation at 4 weeks in differentiation culture medium. C2C12 were cultured on collagen-patterned substrates with different stiffness (scale bar=20 μm) and stained with DAPI for nucleus (blue) and anti-MHC (green). Myosin striation occurred only when cells were cultured on intermediated stiffness substrate. Reprinted with permission from Engler et al.256 Copyright © 2004, Rockefeller University Press. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Other studies also showed that the degree of myoblast differentiation depends on material stiffness. For example, Ren et al. generated biopolymeric films of poly(L-lysine)/hyaluronan with a controlled stiffness ranging from 3 kPa (native film) to 100 kPa (low-cross-linked films) and 400 kPa (high-cross-linked films).118 After culturing C2C12 cells on these films for 1 week in differentiation medium, they observed that myotubes were short and thick on soft films, whereas they were elongated and thin on stiff films and on a polystyrene dish, which was used as a control. Myotube striation increased with the stiffness of the film, from 14% (with a ∼350-kPa film) to 43% (with a ∼400-kPa film) and 69% (with the polystyrene plastic dish; 1 MPa). By using surfaces with different concentrations of silk and tropoelastin, Hu et al. studied the impact of surface roughness and stiffness on the differentiation of myogenic and osteogenic lineages.259 They showed that C2C12 cells preferred low surface roughness with high stiffness. Regarding myoblast differentiation under stretching, the recent literature is controversial. Globally, the consensus is that stretching stimulation increases myoblast proliferation but decreases myoblast differentiation.260–264 In SCs, it also seems that stretching induces NO production and hepatocyte growth factor secretion, both of which are involved in SC activation.265–267 However, the literature diverges concerning MRF expression by myoblasts under stretching. Kook et al. found that mechanical stretching stimulated C2C12 cell proliferation but inhibited differentiation into myotubes through the continuous phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase, which decreases the level of MyoD expression.263 Akimoto et al. cultured C2C12 cells on a silicon membrane (BioFlex) that was stretched with a 20% elongation for 24 h at a frequency of 10 cycles/min (2-s on time, 4-s off time) and observed a decrease in the expression of MyoD and myocyte nuclear factor-α when compared with the nonstretched culture.268 Similarly, Kuang et al. observed a reduction of myogenin expression in C2C12 cells cultured under stretching stimulation.261 In contrast, another study by Abe et al. used a similar system (Flexercell) to culture C2C12 cells stretched to 15% elongation with cycles of 1-s on stretch and 1-s off stretch and observed an increase of MyoD and other myogenic factors after stretching for 12 and 24 h.269 Similarly, Gomes et al. reported increased MyoD expression 24 h after a passive stretching session on in vivo rat muscles.270 Another study using adipose-derived stem cells demonstrated an upregulation of MyoD when the cells were stimulated by stretching.271 Similarly, by using myoblasts loaded in an anchored mixture of collagen-Matrigel and submitted to frequent strain, Powell et al. demonstrated a 12% and 40% increase in myotube diameter and density, respectively.272 Although several studies have established the role of mechanotransduction in myogenesis activation, notably through the p38 MAPK pathway,273,274 the effects of stretching on myoblast differentiation are not yet well understood. A standardized stretching process may be beneficial to better compare results from different research groups.

Coculture with Skeletal Muscle Cells

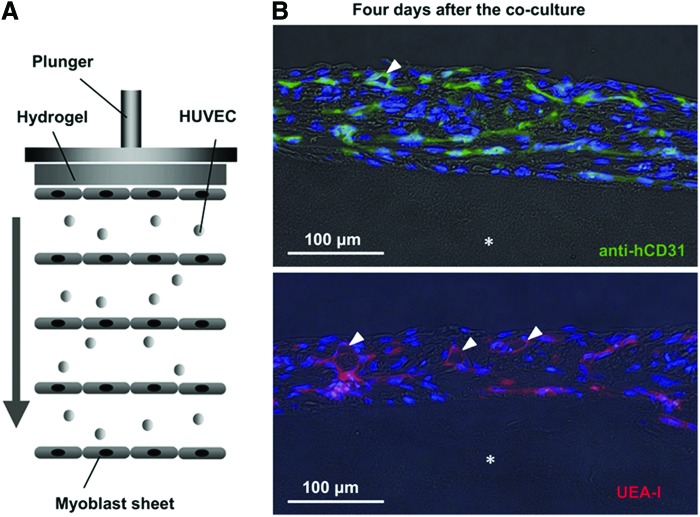

Skeletal muscle with in vivo functionality requires the cooperation of major types of tissues, including muscle tissue, nervous tissue, vascular tissue, and connective tissue. Thus, a skeletal muscle is infused by capillaries and connected to nerve branches, whereas several connective tissues cover the whole muscle (epimysium), the different muscle bundles (perimysium), and the muscle fibers (endomysium). The muscle is also linked to the bone by a tendon, which is a highly ordered connective tissue275,276 (see Fig. 2). These connective tissues are formed from collagen fibers with diameters of 600 to 1800 nm. They are connected to each other when interfacing and have several functions, including giving the muscle its final shape, resisting passive stretch, protecting different tissues from damage, distributing the force generated by muscle fibers, and serving as an ECM for muscle fibers. In skeletal muscle tissue, collagen and other ECM proteins are mainly secreted by interstitial fibroblasts.277,278 Therefore, interactions between muscle and fibroblasts are very important.279 It has been shown that C2C12 myoblasts cocultured on a fibroblast layer formed mature and highly contractile myotubes, with a higher differentiation rate than myoblasts cultured on a collagen-coated substrate.280 Mathew et al. also showed that fibroblastic connective tissues regulate the development and maturation of muscle fibers.281 Ricotti et al. observed higher myoblast differentiation when murine myoblasts cultured on dermal human fibroblasts seeded on micropatterned PA gel were stimulated through piezoelectrical effects by ultrasound, after cell internalization of boron nitride nanotubes supplemented in the culture medium.282 In another study, engineered vascularized muscle tissue with fibroblast participation was achieved in vitro on a highly porous biodegradable copolymer (PLGA-PLLA) sponge scaffold in a triple-culture condition, and it was shown that fibroblasts strongly promoted the formation and stabilization of endothelial vessels in the construct because of increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor.283 When these muscle tissue constructs were implanted in mice, tissue prevascularization was shown to improve the vascularization, blood perfusion, and survival of the implanted muscle tissue. These results are encouraging because the construction of thick tissues has been limited by the lack of vascularization. Other studies have also attempted to build vascularized muscle tissue. For example, Sasagawa et al. described a method based on cell sheet tissue engineering to fabricate vascularized tissue.92 By using thermoresponsive polymer-coated dishes, they generated several layers of endothelial and muscle cells, which they harvested and then stacked together to form a sandwich-like construct of alternated HUVECs and myoblast sheets (Fig. 15). When the constructs were cultured in vitro, capillary-like structures formed in the five layers of the construct. When the constructs were implanted subcutaneously in nude mice, anastomosis with the host vascularization system and survival of the construct were observed.

FIG. 15.

Prevascularization of five-layer myoblast sheet constructs in vitro. (A) Schematic showing the construct made of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) sandwiched between myoblast cell layers. (B) HUVECs in the construct were stained with anti-human CD31 antibody (green, upper photo) or UEA-I (red, lower photo) whereas nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). HUVECs networked through the cell layers and formed capillary-like structures (white arrowheads) at day 4 of coculture. Asterisk shows the position of the fibrin gel used as substrate. Reprinted with permission from Sasagawa et al.92 Copyright © 2010, Elsevier. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Another study by Koffler et al. also used a triple-culture system of myoblasts, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts on a cellular bioscaffold composed of ECM proteins derived from pigs.284 These cell-loaded scaffolds were cultured in vitro for different durations (i.e., 1 day, 1, 2, and 3 weeks) before being transplanted into the abdominal wall of nude mice and were retrieved and analyzed 2 weeks after transplantation. One day of in vitro culture was sufficient to allow transplantation. Tissue (myofibers and vascular network) formation, organization, and integration with the host were poor at 2 weeks post-transplantation, whereas scaffolds cultured in vitro with preorganized tissues at 3 weeks demonstrated high tissue organization with dense-aligned muscle fibers and blood vessels, as well as anastomosis and full integration with the host environment. However, the construction of thick and highly vascularized tissues is still a challenge. It has been shown that muscle cells and endothelial cells affect each other through angiotensin II (ANG II). Indeed, in in vitro angiogenesis assays with HUVECs treated by ANG II, increases of 71% and 124% in tube length and branch point number were observed, respectively. Moreover, when HUVECs were cultured in conditioned media from differentiated muscle cells, the tube length and branch point number increased by 84% and 203%, respectively, when compared with controls.285 Other experiments showed that in growth medium, SCs and C2C12 cells expressed vein endothelial growth factor and its receptors to promote angiogenesis.286 Therefore, it can be concluded from these experiments that bi- and triculture systems are essential for future studies in this field.