Abstract

Background: Social functioning is an important treatment outcome for psychosis, and yet, we know little about its relationship to trauma despite high rates of trauma in people with psychosis. Childhood trauma is likely to disrupt the acquisition of interpersonal relatedness skills including the desire for affiliation and thus lead to impaired social functioning in adulthood. Aims: We hypothesized that childhood trauma would be a predictor of poor social functioning for adults with psychosis and that further trauma in adulthood would moderate this relationship. Method: A first-episode psychosis sample aged 15–65 years (N = 233) completed measures of social functioning (Lehman’s Quality of Life Interview and Strauss Carpenter Functioning Scale) and trauma (Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey), as well as clinical assessments. Results: Childhood trauma (any type) was associated with poorer premorbid functioning and was experienced by 61% of our sample. There were no associations with clinical symptoms. Interpersonal trauma in childhood was a significant predictor of social functioning satisfaction in adulthood, but this was not the case for interpersonal trauma in adulthood. However, 45% of adults who reported childhood interpersonal trauma also experienced adulthood interpersonal trauma. Conclusion: Our results emphasize the importance of early relationship experience such as interpersonal trauma, on the social functioning of adults with psychosis. We recommend extending our research by examining the impact of interpersonal childhood trauma on occupational functioning in psychosis.

Key words: childhood trauma, social satisfaction, relationships, early psychosis

Introduction

Social functioning and subjective quality of life are recognized as important treatment outcomes in schizophrenia and psychosis.1 They have been defined as either global constructs or as differing degrees of the person’s capacity to adjust to personal, family, social, and professional needs. The importance of social functioning to quality of life is evidenced in the second Australian National Survey of Psychosis, whereby adults with psychosis rated achieving better social relations as a top challenge.2 Reduced social functioning in psychosis is associated with negative symptoms such as anhedonia and avolition.3,4 One study showed that patients in nonremission for schizophrenia showed greater preference for being alone when in the company of others, compared with the remission group despite both groups spending equal time with social contacts.5 In adolescents with subclinical psychotic experiences, poorer interpersonal functioning was associated with positive symptoms such as bizarre experiences and persecutory ideation.6

Social functioning in psychosis has also been shown to be associated with premorbid childhood and adolescent functioning. It is well known that poor emotional and social development in childhood is influenced by family relationships in the home.7 Trauma or maltreatment occurring in childhood coincides with the period for a child’s development of relational understanding such as attachment to others and the reflective awareness of self and others.8 Furthermore, a history of trauma seems to be significantly more common in patients with psychosis, compared with the general population. A meta-analysis showed childhood trauma was associated with a 2.8 times increased risk for psychosis in adulthood.9 Childhood trauma often involves attachment disruption and interpersonal violence in the context of primary relationships. It can therefore disrupt the acquisition of interpersonal relatedness skills, including the desire for affiliation, and lead to difficulty with social functioning in adulthood. For adults with psychosis, avoidant attachment style has been associated with positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and paranoia.10 Furthermore, a review has shown that insecure attachment is associated with poorer interpersonal relationships in psychosis.11 Multiple traumas in childhood are associated with a range of problems beyond the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, including problems with self-functioning, affect regulation and the capacity to form positive relationships.12 Parental abuse has been shown to be predictive of decreased social support in adulthood13 and an increased likelihood of negative interactions in close relationships.14

Little is known about the contribution of trauma to impaired social functioning in psychotic patients. In order to examine this link, we sought to measure several domains of social functioning that focused on relationships with others and participation in activities. We analyzed data from a sample of first-episode psychosis (FEP) adults in order to avoid the potential confound of long-term symptoms and medication on social functioning. We hypothesized that childhood trauma would be a predictor of poor social functioning for adults with psychosis and that further trauma in adulthood would moderate this relationship.

Methods

The sample was recruited as part of the on-going TIPS 2 study (Early Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis) that commenced in 200215 and included persons experiencing a FEP. All participants completed baseline clinical assessment for TIPS 2 (see Joa et al15 for details of method and assessment tools). The project was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Health Region West, Norway (015.03).

Participants

The FEP sample was drawn from a population-based cohort of FEP individuals, recruited in 1 hospital catchment area. Altogether, 482 consecutive individuals were identified, and 70 of them were excluded (21 were not registered in the catchment area, 12 had poor language skills, 11 were younger than 15 years of age, and 6 had a low IQ). There were 20 individuals lost to study contact. Of the 412 remaining individuals, 165 refused participation. The rate of consent to participate was therefore 60% (247 individuals). This report comprises data from the time of inclusion. The inclusion criteria were living in the hospital catchment area (Rogaland County); age 15–65 years; meeting the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia spectrum disorder or psychosis; being actively psychotic, as measured by a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)16 score of 4 or more on delusions, hallucinations, grandiose thinking, suspiciousness, or unusual thought content; not previously receiving adequate treatment for psychosis (defined as antipsychotic medication of 3.5 haloperidol equivalents for 12 weeks or until remission of the psychotic symptoms); no neurological or endocrine disorders associated with the psychosis; no contraindications to antipsychotic medication; understands/speaks one of the Scandinavian languages; and IQ over 70 (estimate based on Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale).

Clinical Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)17 was used for diagnostic purposes and symptom levels determined by mean scores and factor scores on the PANSS.18,19 Global functioning was measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF),20 and the scores were split into symptom (GAFs) and function (GAFf) subscales.21 The misuse of alcohol and other drugs was measured by the Clinicians Rating Scale.22 Onset of psychosis was equated with the first appearance of positive psychotic symptoms, corresponding to a PANSS score of 4 or more on at least one of the following PANSS items; P1 (delusions), P3 (hallucinations), P5 (grandiosity), P6 (suspiciousness), and A9 (unusual thought content), for at least 7 days. Premorbid functioning was measured with the Premorbid Adjustment Scale.23 To measure initial level for this report, we used the childhood scores for each dimension, while change was calculated as the difference between the late adolescent and the childhood scores.24,25

Social Functioning Measures

The brief version of Lehman’s Quality of Life Interview (L-QoLI)26 was used to measure objective (eg, family contact) and subjective (eg, satisfaction with social relations) social functioning. We used 5 QoLI subscales that included the subjective measures of satisfaction with family, social relations, and daily activities, and the objective measures of family and social contact. Subjective measures were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted).27 The psychometric properties for the QoLI have been extensively assessed. Internal consistency ranges from 0.79 to 0.88 (median 0.85) for the life satisfaction scales; and from 0.44 to 0.82 (median 0.68) for the objective quality of life scales. Test-retest reliabilities (one week) range from 0.41 to 0.95 (median 0.72) for life satisfaction; and 0.29 to 0.98 (median 0.65) for objective scales.26 The Strauss Carpenter Level of Functioning Scale (SCS)28 was administered to measure social contacts and meaningful activities in the past year. Individual items on the SCS were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with higher values indicative of better functioning.

Trauma Assessment

The Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey (BBTS)29 is a 12-item, self-report measure of traumatic events experienced in both childhood (<18 y), and adulthood (>18 y). Each participant was asked to respond to whether they experienced (ie, yes or no) 4 categories of traumatic events: noninterpersonal traumas (eg, been in a major automobile, boat, motorcycle, plane, train, or industrial accident that resulted in similar consequences); interpersonal traumas by someone not close to them (eg, you were deliberately attacked that severely by someone with whom you were not close); interpersonal traumas perpetrated by someone close to them (eg, you were deliberately attacked severely by someone with whom you were very close); and other trauma (eg, you experienced the death of one of your own children). The BBTS has been demonstrated to have both good construct validity30 and test-retest reliability.29

Data Analysis

Univariate pairwise comparisons of continuous variables were done using nonparametric statistics (Mann-Whitney U) due to nonnormality of several of the variables. Nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney U) were employed as some of the variables were skewed and not correctable through transformations. While this was a problem for certain variables, we chose nonparametric tests for all univariate tests to ensure a uniform analysis strategy. Categorical variables in 2 × 2 crosstabs were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Sequential linear regression analysis was used to test the hypothesis that childhood trauma predicts social functioning independent of adult trauma. Mean satisfaction with social and family relationships was calculated and entered as dependent variable. In the first block of the analysis, age and sex were entered, followed in the next block by the 5 PANSS factor sum-scores (positive, negative, disorganized, excitative, depressive) entered using stepwise elimination (probability for variable to enter ≤ .050, probability for variable to remove ≥ .100), followed by a block with adulthood interpersonal trauma, and in the final block, childhood interpersonal trauma was entered. We tested for normality of the dependent variable in the regression using histogram with visual inspection and, formally, using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KST). The KST was nonsignificant, indicating that the variable did not deviate from the normal distribution, and the histogram confirmed this.

To test whether childhood trauma (any type) is associated with higher risk of adulthood trauma (any type), we used Fisher’s exact test. We then tested for moderation/interaction effects between adulthood interpersonal trauma and childhood interpersonal trauma using analyses of covariance. Thus, to investigate whether adulthood trauma moderates the effect of childhood trauma on satisfaction with family and social relationships, an ANCOVA was performed with the trauma variables as fixed factors and, ageand sex, the selected PANSS factor score(s) (from the regression analysis). All analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows, version 20.31

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We recruited a sample of 247 individuals in the study period (January 2002 to February 2011). There were 14 individuals for whom baseline trauma data were not available, but these individuals were not significantly different on demographic or clinical characteristics compared with the 233 individuals included in the analysis. Sample characteristics are displayed in table 1. Our FEP sample had a mean age of 26.5 years, and 43.7% reported having experienced some form of childhood trauma.

Table 1.

Demographic, Baseline Clinical Characteristics, Premorbid and Social Functioning Across Childhood Trauma/No Childhood Trauma

| Childhood Trauma, n = 102 | No childhood trauma, n = 131 | Total, n = 233 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographicsa (alpha = .01) | ||||

| Age, years | 26.7 (10.4) | 26.0 (9.7) | 26.5 (10.1) | .620 |

| Female % (N) | 44.1 (45) | 41.2 (54) | 43.8 (102) | .690 |

| Education years | 11.5 (2.9) | 12.1 (2.3) | 11.8 (2.6) | .149 |

| Nordic nationality (%, N) | 94.1 (96) | 93.1 (122) | 93.6 (218) | .796 |

| Marital status (%, N) | .400b | |||

| Single | 75.5 (77) | 77.7 (101) | 76.7 (178) | NA |

| Div/sep/widow | 3.9 (4) | 6.9 (9) | 5.6 (13) | NA |

| Married/defacto | 20.6 (21) | 15.4 (20) | 17.7 (41) | NA |

| Clinical statusa (alpha = .005) | ||||

| Age of onset (y) | 24.2 (9.6) | 25.6 (10.6) | 25.0 (10.2) | .278 |

| PANSS factors | ||||

| Negative | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.0) | .219 |

| Disorganized | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.1) | .615 |

| Depressive | 3.3 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | .222 |

| Positive | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.9) | .782 |

| Excitative | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.7) | .872 |

| Symptoms (GAF) | 31.8 (6.8) | 31.0 (7.8) | 31.3 (7.3) | .400 |

| Functioning (GAF) | 39.3 (9.4) | 40.1 (9.9) | 39.7 (9.7) | .534 |

| Alcohol abuse % (N) | 11.8 (12) | 13.0 (17) | 12.4 (29) | .843 |

| Drug abuse % (N) | 27.7 (28) | 26.0 (34) | 26.7 (62) | .767 |

| Premorbid adjustmenta (alpha = .006) | ||||

| Social | ||||

| Child | 1.05 (1.30) | 0.84 (1.24) | 1.33 (1.34) | .006 |

| Early adolescence | 1.27 (1.20) | 1.10 (1.17) | 1.48 (1.21) | .024 |

| Late adolescence | 1.46 (1.30) | 2.36 (1.39) | 1.71 (1.34) | .020 |

| Change (EA-C) | 0.42 (1.36) | 0.45 (1.25) | 0.37 (1.48) | .825 |

| School | ||||

| Child | 1.83 (1.29) | 1.73 (1.28) | 1.97 (1.31) | .001 |

| Early adolescence | 2.45 (1.36) | 2.23 (1.37) | 2.74 (1.29) | .007 |

| Late adolescence | 2.51 (1.43) | 2.36 (1.39) | 2.70 (1.45) | .003 |

| Change (EA-C) | 0.72 (1.47) | 0.69 (1.46) | 0.74 (1.49) | .365 |

| Social functioninga (alpha = .008) | ||||

| Satisfaction | ||||

| Family relations | 4.4 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.4) | .016 |

| Social relations | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.2) | .355 |

| Contacts | ||||

| Family | 4.0 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.8) | .866 |

| Social | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.0) | .161 |

| Strauss carpenter | ||||

| Meaningful activities | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.6) | .846 |

| Relationships | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.3) | .816 |

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; NA, not applicable.

EA-C is early adulthood minus childhood premorbid adjustment.

aBonferroni adjusted alpha levels for each section of the table.

bOmnibus 2×3 chi square.

As can be seen from table 1, those who experienced childhood trauma had poorer premorbid social and academic functioning compared with those who had not experienced childhood trauma. Poorer social functioning was evident from childhood through to late adolescence as measured by the Premorbid Adjustment Scale.

School adjustment in early adolescence was poorer for those with childhood trauma (P = .007). However, the change in social or academic functioning from childhood through to early adolescence was not significantly different between the 2 groups. In adulthood, those with childhood trauma were significantly less satisfied with their family relationships (P < .016). There were no significant differences on nonsocial functioning measures, such as the GAF, between those who had experienced childhood trauma and those who had not.

The rates at which the different types of trauma were endorsed for both childhood and adulthood are shown in table 2. Interpersonal trauma by someone close or not close to the individual was the type of trauma most likely to be reported as being experienced in childhood (36% of sample) or adulthood (36.8% of sample). By contrast, noninterpersonal trauma was reported in childhood by 15.8% and in adulthood by 12.1% of the sample.

Table 2.

Frequency of Interpersonal and Noninterpersonal Trauma in Childhood and Adulthood

| Trauma Type | Childhood | Adulthood |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | ||

| Not close | 20.2 (47) | 21.5 (50) |

| Close | 18.0 (42) | 17.6 (41) |

| Noninterpersonal | 16.7 (39) | 12.9 (30) |

| Other | 9.0 (21) | 13.7 (32) |

Note: All numbers—% (N).

Childhood Trauma Association With Adulthood Trauma

The relationship between experiencing childhood and adulthood interpersonal trauma of any type is shown in table 3. Fisher’s exact test was significant (2-sided P = .016), hence childhood trauma and adulthood trauma were related in our sample. The results show that individuals who had not experienced childhood trauma were significantly less likely to experience trauma in adulthood (49% of sample).

Table 3.

Relationship Between Childhood and Adulthood Interpersonal Trauma

| Adulthood Trauma | No Adulthood Trauma | |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood trauma | 33 (14) | 41 (18) |

| No childhood trauma | 44 (20) | 115 (49) |

Note: All numbers—N (%); total N = 233. Fisher’s exact (2-sided): P = .016.

Childhood Trauma Predicting Social Functioning Independent of Adult Trauma

In table 4, the sequential multiple regression analysis using mean satisfaction with social and family relationships as the dependent variable is shown.

In block 2, the stepwise procedure selected the PANSS depression score as the only PANSS factor score for inclusion in the model, and when added to block 1 (age, sex, total PANSS), it resulted in a significantly increased R 2 (see table 4). Adulthood interpersonal trauma did not significantly contribute to the model, but in block 4, childhood interpersonal trauma resulted in a significantly increased R 2, with age, PANSS depression, and childhood interpersonal trauma remaining as significant independent predictors of satisfaction with social and family relationships.

Table 4.

Sequential Regression With Relationship Satisfaction (Family and Social Mean) Score as the Dependent Variable

| Step | Variable | R 2 | R 2 Change | F Change | Beta | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | .05 | .05 | 5.13 | .007 | ||

| Age | .197 | .007 | ||||

| Sex | −.079 | .266 | ||||

| 2. | .09 | .04 | 8.86 | .003 | ||

| Age | .186 | .008 | ||||

| Sex | −.040 | .573 | ||||

| PANSS depression score | −.209 | .003 | ||||

| 3. | .10 | .01 | 1.21 | .273 | ||

| Age | .170 | .018 | ||||

| Sex | −.039 | .577 | ||||

| PANSS depression score | −.213 | .003 | ||||

| Adulthood IP trauma | .077 | .273 | ||||

| 4. | .13 | .03 | 6.54 | .011 | ||

| Age | .165 | .020 | ||||

| Sex | −.036 | .610 | ||||

| PANSS depression score | −.205 | .003 | ||||

| Adulthood IP trauma | .107 | .128 | ||||

| Childhood IP trauma | −.176 | .011 |

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

IP is interpersonal trauma either close or nonclose. Beta is standardized alpha level set to .05.

Adulthood Trauma Moderating the Effect of Childhood Trauma on Social Function Satisfaction

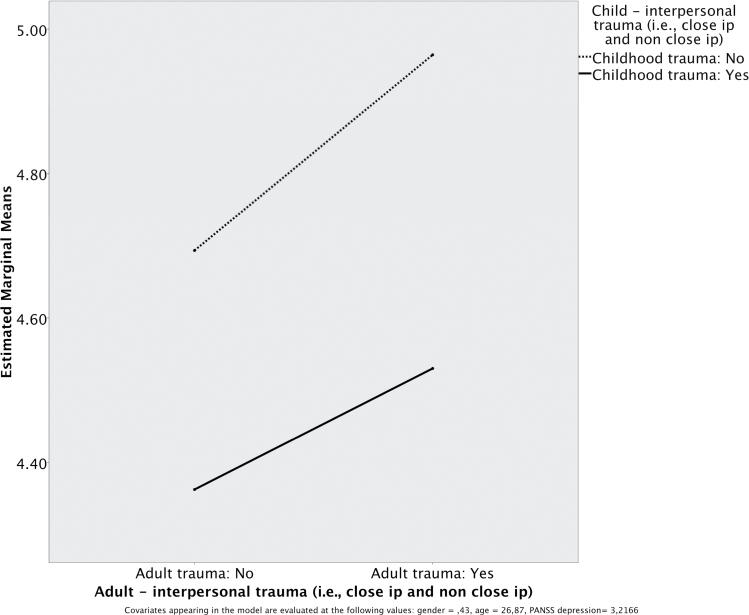

The ANCOVA did not show a significant interaction between adulthood and childhood interpersonal trauma as related to satisfaction with social and family relationships (see figure 1), F(1,190) = 0.105, P = .746. Interpersonal childhood trauma (with or without adult interpersonal trauma) was associated with lower levels of satisfaction with family and social relationships than was interpersonal adult trauma alone (without interpersonal childhood trauma).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between satisfaction with family and social relationships and interpersonal trauma (adult and child).

Discussion

As predicted, childhood trauma was associated with disruptions to social functioning, and this was evident from childhood on into adulthood. For our sample of adults with FEP, those who had experienced any type of childhood trauma had poorer social functioning in the premorbid phases of childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence compared with those without childhood trauma. By early adolescence, there was also evidence of poorer academic functioning for adults who had experienced childhood trauma. In adulthood, those who had experienced childhood trauma were significantly less satisfied with family relationships. However, the frequency of social or meaningful activities in adulthood did not differ as a function of having experienced childhood trauma.

The cross-sectional design of our study restricts interpretation of causality or the temporal sequence of childhood trauma and premorbid social functioning. Strauss et al28 refer to a low social drive being evident in some individuals in childhood and that this may be an early indicator of neurodevelopmental abnormalities that are later expressed as enduring negative symptoms of schizophrenia. This low social drive in childhood was also associated with an accelerated decline in social functioning between early and late adolescence. For our sample, childhood trauma was associated with significantly poorer social functioning in childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence, thus raising the question of whether childhood trauma was a contributor to the findings of Strauss et al.32 In addition, the disruption of attachment through trauma in childhood is likely to contribute to this poorer social functioning throughout development in childhood and adolescence because maladaptive patterns of relating are maintained. There is also evidence for early trauma to lead to increased interpersonal sensitivity and attachment difficulties that together would impact on social functioning.33

More than half of our clinical sample of adults with FEP reported having experienced trauma in either childhood (61%) or adulthood (63%). These rates for childhood trauma lie within the range reported by other studies. For example, in one study, 86% of adults with schizophrenia reported some form of childhood abuse primarily in relation to parenting.34 Other studies have shown rates of childhood sexual abuse ranging from 27% to 42%.35,36 Differences in measurement of trauma impede direct comparisons between studies. We have assessed for common types of trauma such as physical or sexual abuse, thus allowing for comparison. We have then categorized according to interpersonal- or noninterpersonal-based trauma in order to better discriminate the impact of trauma on social functioning.

Both childhood and adulthood traumas had been experienced by 14% of our adults with FEP, and the most common type of trauma was interpersonal. Thus, nearly half of all adults (45%) who experienced childhood interpersonal trauma also experienced interpersonal trauma in adulthood. The negative impact of interpersonal trauma in childhood on the development of interpersonal skills could result in a poor choice of partners in adulthood and thus place one at risk for interpersonal violence.

Our proposal that interpersonal rather than noninterpersonal trauma would have the greatest impact on social functioning was supported. Noninterpersonal trauma was less frequent than interpersonal trauma, and it was not a significant predictor of social functioning satisfaction in adulthood. Although the rates of interpersonal trauma remained the same across childhood and adulthood, it was childhood and not adulthood interpersonal trauma that was a significant predictor of social functioning satisfaction for our adults. While not explored in our study, there are two possible interpretations for this finding. First, interpersonal trauma in childhood may disrupt the attainment of social relationship skills and thus impair the ability to initiate and maintain satisfying relationships in adulthood. Attachment theory shows that early disruption of attachment, namely in childhood, leads to the development and maintenance of interpersonal difficulties over the life span.11 Longitudinal attachment studies suggest that social functioning difficulties such as social isolation, communication abnormalities, and disturbed peer relationships predispose individuals to the development of psychosis.37 Second, interpersonal childhood trauma is most likely to arise in the family context and thus family relationships in adulthood will be compromised. This is particularly relevant to adults with FEP who are likely to have contact with family for the purposes of mental health and social care. Thus, there may be a high frequency of social contact, but this contact may not be pleasurable.

Interestingly, we did not find differences in clinical features such as symptoms, drug abuse, or age of onset of psychosis between adults who had and adults who had not experienced childhood trauma. However, we found that depression was a significant predictor of social functioning satisfaction. The literature reports mixed findings for gender and social functioning. For example, a study of community-dwelling men and women with schizophrenia found poorer social functioning for men compared with women and that symptom scores accounted for most of the variance in social functioning in both genders.38 By contrast, no significant effect of sex was observed on any index of social functioning for another sample of adults with schizophrenia.39 Similarly, we did not find a gender difference in social functioning for our sample.

Limitations

The rates of trauma reported by adults with FEP in our sample are comparable to other samples including adults with more established psychotic illness. Studies have shown there is a greater likelihood of under reporting rather than overreporting of childhood trauma.40 In addition, our focus on FEP has reduced the potential impact of psychosis itself on recall compared with other studies with samples of adults with more chronic psychosis. While there are certain limitations on our findings due to the cross-sectional design, it was not our intention to explore risk for psychosis as a factor of trauma. However, a longitudinal design would have allowed for examination of the temporal sequence of childhood trauma and premorbid social functioning. Likewise, the assessment of the frequency of trauma experiences and distress in response to trauma could have informed this relationship. It should also be noted that 40% of eligible individuals declined to participate, so their history of trauma is unknown. The TIPS2 study has been extended to include substance-induced psychosis since 2008. Our refusal rate was high in this group reflecting the difficulty of recruiting this group into research and into the health care system.

Conclusions

A study of remission in schizophrenia defined good social functioning as having a positive occupational status, independent living, and active social interactions.4,41 Our study demonstrated the possible impact of interpersonal childhood trauma on the social functioning of adults in a first episode of psychosis. This is a major concern for service delivery, given the importance of social relationships to quality of life for adults with psychosis2 and to engagement in services as a result of attachment styles.42 Witnessing violence and experiencing sexual abuse in childhood have been associated with increased likelihood of being dismissed from employment, thus suggesting interpersonal difficulties may be involved.43 Further research may therefore benefit from exploring how our findings relate to occupational functioning in FEP.

Funding

Health Vest Trust (200202797-65 to I.J.); Regional Centre for Clinical Research in Psychosis (911313).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge members of the TIPS detection team: Robert Jørgensen, Kristin Hatløy, Aase Undersrud Bergensen, Jonny Pettersen, and Kari Hedin. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Figueira ML, Brissos S. Measuring psychosocial outcomes in schizophrenia patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stain HJ, Galletly CA, Clark S., et al. Understanding the social costs of psychosis: the experience of adults affected by psychosis identified within the second Australian National Survey of Psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:879–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Álvarez-Jiménez M, Gleeson JF, Henry LP., et al. Road to full recovery: longitudinal relationship between symptomatic remission and psychosocial recovery in first-episode psychosis over 7.5 years. Psychol Med. 2012;42:595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B., et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:374–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oorschot M, Lataster T, Thewissen V., et al. Symptomatic remission in psychosis and real-life functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collip D, Wigman JT, Lin A., et al. Dynamic association between interpersonal functioning and positive symptom dimensions of psychosis over time: a longitudinal study of healthy adolescents. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:179–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engels RCME, Finkenauer C, Meeus W, Dekovic M. Parental attachment and adolescents’ emotional adjustment: the associations with social skills and relational competence. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48:428–439 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes J. The Search for the Secure Base: Attachment Theory and Psychotherapy. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor Francis Inc; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M., et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:661–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berry K, Barrowclough C, Wearden A. Attachment theory: a framework for understanding symptoms and interpersonal relationships in psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1275–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berry K, Barrowclough C, Wearden A. A review of the role of adult attachment style in psychosis: unexplored issues and questions for further research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:458–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiat Ann. 2005;35:401–408 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vranceanu AM, Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptoms: the role of social support and stress. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beards S, Gayer-Anderson C, Borges S, Dewey ME, Fisher HL, Morgan C. Life events and psychosis: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:740–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B., et al. The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: information campaigns. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:466–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. First MSR, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Patient Edition SCID I/P, Version 2.0 ed. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Langeveld J, Andreassen OA, Auestad B., et al. Is there an optimal factor structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in patients with first-episode psychosis? Scand J Psychol. 2013;54:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:246–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 3rd ed, revised. Washington, DC: APA; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U., et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, Beaudett MS. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8:470–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haahr U, Friis S, Larsen TK., et al. First-episode psychosis: diagnostic stability over one and two years. Psychopathology. 2008;41:322–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larsen TK, Friis S, Haahr U., et al. Premorbid adjustment in first-episode non-affective psychosis: distinct patterns of pre-onset course. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:108–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lehman AF. Measures of quality of life among persons with severe and persistent mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:78–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehman AF, Kernan E, Postrado L. Evaluating the Quality of Life for Persons With Severe Mental Illnesses. Baltimore, MD: Center for Mental Health Services Research; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT., Jr The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. II. Relationships between predictor and outcome variables: a report from the WHO international pilot study of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;31:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldberg LR, Freyd JJ. Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. J Trauma Dissociation. 2006;7:39–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. Memory and dissociative tendencies: the roles of attentional context and word meaning in a directed forgetting task. J Trauma Dissociation. 2001;2:67–82 [Google Scholar]

- 31. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strauss GP, Allen DN, Miski P, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Carpenter WT., Jr Differential patterns of premorbid social and academic deterioration in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;135:134–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Masillo A, Day F, Laing J., et al. Interpersonal sensitivity in the at-risk mental state for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1835–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCabe KL, Maloney EA, Stain HJ, Loughland CM, Carr VJ. Relationship between childhood adversity and clinical and cognitive features in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:600–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fisher H, Morgan C, Dazzan P., et al. Gender differences in the association between childhood abuse and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morgan C, Fisher H. Environment and schizophrenia: environmental factors in schizophrenia: childhood trauma–a critical review. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’. Schizophr Res. 2004;71:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vila-Rodriguez F, Ochoa S, Autonell J, Usall J, Haro JM. Complex interaction between symptoms, social factors, and gender in social functioning in a community-dwelling sample of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2011;82:261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galderisi S, Bucci P, Üçok A, Peuskens J. No gender differences in social outcome in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:406–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fisher HL, Craig TK, Fearon P., et al. Reliability and comparability of psychosis patients’ retrospective reports of childhood abuse. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:546–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haro JM, Novick D, Bertsch J, Karagianis J, Dossenbach M, Jones PB. Cross-national clinical and functional remission rates: Worldwide Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (W-SOHO) study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. MaBeth A, Gumley A, Schwannauer M, Fisher R. Attachment states of mind, mentalization, and their correlates in a first-episode psychosis sample. Psychol Psychother. 2011;84:42–57; discussion 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sansone RA, Leung JS, Wiederman MW. Five forms of childhood trauma: relationships with employment in adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:676–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]