Abstract

This study aimed to establish consensus about the meaning of recovery among individuals with experience of psychosis. A Delphi approach was utilized to allow a large sample of service users to be anonymously consulted about their views on recovery. Service users were invited to take part in a 3-stage consultation process. A total of 381 participants gave their views on recovery in the main stage of this study, with 100 of these taking part in the final review stage. The final list of statements about recovery included 94 items, which were rated as essential or important by >80% of respondents. These statements covered items which define recovery, factors which help recovery, factors which hinder recovery, and factors which show that someone is recovering. As far as we are aware, it is the first study to identify areas of consensus in relation to definitions of recovery from a service user perspective, which are typically reported to be an idiosyncratic process. Implications and recommendations for clinical practice and future research are discussed.

Key words: recovery, schizophrenia, consumer, service user, Delphi method, psychosis

Introduction

Mental health services typically define recovery from psychosis in terms of absence of symptoms, decreases in duration of hospital admissions, and reduced rate of rehospitalization.1 Clinical research trials often attempt to quantify recovery by demonstrating significant improvements in symptoms and other so called “deficits” to the degree that they could be considered within the “normal” range.2 In stark contrast, service users conceptualize recovery differently,3 believing that recovery is a unique process rather an end point with key recovery themes including hope, rebuilding self, and rebuilding life.4 Many qualitative studies of service user accounts demonstrate these themes of recovery and indicate that there is potential for all individuals to recover to some extent.5

This optimism about the potential for recovery has been adopted in various health policies,6–10 which have a focus upon collaborative working between clinicians and service users, rebuilding lives with or without ongoing symptoms and recognizing the importance of hope and empowerment. Despite this recognition of what may be required for recovery-orientated mental health services, it is not always clear how health professionals can provide effective recovery-orientated services that can be evaluated for performance in supporting people to recover.11

Various measures of service user-defined recovery have been developed with items covering a variety of themes including hope, empowerment, awareness/understanding, help-seeking, social support, and goals/purpose.12 Only 2 measures have been developed to measure service user-defined recovery from psychosis: the Psychosis Recovery Inventory13 and the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery.14 Such user-defined recovery measures have yet to be adopted as routine outcome measures in mental health services, although in the United States, New York State has mandated recovery-orientated treatment planning and measurement for state-funded psychiatric programs. Despite this, there is continued debate about whether recovery can be measured as an outcome when it is defined as an idiosyncratic process. It has been suggested that if measurement of recovery is a collaborative process involving service users and clinicians, it could be a feasible and valid method for evaluation of effective recovery-orientated services.15

Although there has been a reasonable level of agreement that mental health services should aim to be recovery orientated, the problem of reaching consensus about what is meant by recovery and producing a definition that is acceptable to service users, while being practical and achievable for clinicians and services, has yet to be resolved. Service user accounts16–19 and qualitative studies exploring recovery4,20,21 identify common themes with most, if not all, concluding that recovery is a unique and individual process. This makes it extremely difficult for clinicians and services to provide recovery-orientated services. The extent to which service users agree about what constitutes recovery and what helps their recovery has yet to be explored.

Various techniques can be employed to reach consensus about a given debated topic.22 One such technique is the Delphi method, which is a systematic process of engaging a panel of “experts” in the chosen field in 2 or more rounds of questionnaires, with the aim of identifying items which the expert panel agree are important to the chosen topic. The Delphi method has been utilized to identify essential elements in schizophrenia care,23 indicators of relapse,24 essential elements of early intervention services,25 first aid guidelines for psychosis,26 and components of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis.27

Expert panels usually consist of clinicians and academics, although some studies have utilized small groups of service users.26,28 On the topic of recovery from psychosis, it could be argued that service users are the experts. Indeed, many of the documents which endorse a recovery approach accept that recovery should be defined by service users. Many current National Health Service (NHS) initiatives in the United Kingdom aim to view the patient as the expert,29 and mental health services are increasingly taking this approach of valuing service users as “experts by experience.”30

This study utilizes the Delphi methodology to consult a large group of service users with the aim of determining levels of consensus for service user conceptualizations of recovery. As such, it will provide unique information to establish shared agreement regarding the definition of a process which is often viewed as an idiosyncratic journey.

Methods

Participants

Participants were included in the study if they have (or have had) experience of psychosis, were over the age of 16, and able to understand English. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling through mental health services (including Community Mental Health Teams and Early Intervention Services), non-NHS/voluntary groups and networks, and advertising of the study by leaflets, posters, email networks, websites, social media, and local media (including press releases). This study was supported by the Mental Health Research Network who provided clinical studies officers to advertise and recruit participants using the methods described above. Recruitment took place across 7 NHS mental health trusts in the North West of England.

Procedure and Analysis

This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East Midlands. The Delphi process consisted of 3 stages based around those identified by Langlands et al.26

Stage 1.

Elements identified as pertinent to conceptualization of recovery in psychosis were identified through a literature search of journals, policy documents, recovery measures, and websites. This was reviewed by the authors and collated into an initial list of statements (N = 141). Due to the complexities of including a large panel of service users as the experts to be consulted, the authors decided to use a smaller panel of service users (a local service user reference group with 10 members, all of whom have personal experience of psychosis and using mental health services) during stage one to further refine this initial statement list. Five members of this group suggested changes which resulted in the addition of a further 3 items, rewording of several items to increase acceptability to service users (eg, including the word “experiences” alongside “symptoms” and removing the word “illness” where possible) and deletion of 7 items which were felt by the service users to be duplications. For ease of administration, the statement list was divided into 4 sections depending on the nature of the statement: defining recovery, factors that help recovery, factors that hinder recovery, and factors that show someone is recovering. The service user group approved the 4 subsections within the statement list.

Stage 2.

The finalized list of 137 statements from stage 1 was collated and formatted into an web-based and paper questionnaire. A demographics sheet was added to collect data on age, gender, mental health trust, diagnosis, and length of diagnosis. Participants were also asked if they would like to provide a postal or email address so they could be invited to take part in the final stage of the study, although this was optional to allow complete anonymity if preferred.

Participants rated the importance of each item on the statement list, on a 5-point Likert scale (1: essential, 2: important, 3: do not know/depends, 4: unimportant, and 5: should not be included). A total of 426 participants completed the stage 2 questionnaire, although 45 were not included in the final sample (26 were deemed to be ineligible due to reporting no experience of psychosis, 14 people did not complete the questionnaire, 1 person added a note to say they had already completed the study before, and 4 people posted the questionnaire after the deadline). Results from the remaining 381 eligible participants were entered into an anonymized database and analyzed by obtaining group percentages.

In accordance with the methods used by Langlands et al26, the following criteria were used to determine items for inclusion, exclusion, and rerating.

Items rated by 80% or more participants as essential or important to defining or conceptualizing recovery are included as standard.

Items rated as essential or important to defining or conceptualizing recovery by 70%–79% of respondents in stage 2 will be rerated in stage 3.

Any statements that did not meet the above 2 conditions were excluded.

This resulted in the inclusion of 71 items, the exclusion of 30 items and 36 items to be rerated in stage 3.

Stage 3.

In stage 3, participants were asked to rerate only those items that 70%–79% of respondents had rated as essential or important during stage 2 (n = 36 items). About 206 participants provided contact details to be invited to take part in stage 3. The majority of participants opted to be sent a postal paper version rather than complete the questionnaire online. A total of 154 postal questionnaires were distributed in stage 3, and 52 participants were sent the online questionnaire link. Participants were also given a leaflet summarizing the findings from the previous stages. A total of 100 participants completed the final stage, resulting in a further 23 statements being included and 13 statements being excluded. As in stage 2, items were included if they were rated by 80% or more participants as essential or important to defining or conceptualizing recovery. Items which did not reach this level of consensus were excluded in line with recommendations by Langlands et al26. The Delphi methodology utilizes this process of multiple rounds and feedback of results to facilitate the establishment of expert consensus.

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the demographic information. The majority of participants were male in stage 2 (59.6%) and female in stage 3 (56%). The most common age range was 40–49 years in both stages, and similarly, schizophrenia was the most commonly reported diagnosis. Around half of participants in both stages had an established diagnosis (diagnosis given more than 10 years ago).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Stage 2 (N = 381) | Stage 3 (N = 100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 223 (59.6%) | 43 (43%) |

| Female | 151 (39.6%) | 56 (56%) |

| Not stated | 7 (1.8%) | 1 (1%) |

| Age | ||

| 17–20 | 7 (1.8%) | 1 (1%) |

| 21–29 | 53 (13.9%) | 9 (9%) |

| 30–39 | 94 (24.7%) | 16 (16%) |

| 40–49 | 108 (28.3%) | 29 (29%) |

| 50–59 | 72 (18.9%) | 27 (27%) |

| 60 or older | 40 (10.5%) | 17 (17%) |

| Not stated | 7 (1.8%) | 1 (1%) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 152 (39.9%) | 32 (32%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 66 (17.3%) | 28 (28%) |

| Prefer not say | 62 (16.3%) | 11 (11%) |

| Other | 26 (6.8%) | 8 (8%) |

| Psychosis | 24 (6.3%) | 8 (8%) |

| Depression | 20 (5.2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 16 (4.2%) | 5 (5%) |

| No diagnosis | 15 (3.9%) | 7 (7%) |

| Length of diagnosis | ||

| Within the last year | 36 (9.4%) | 5 (5%) |

| 1–4 y ago | 64 (16.8%) | 15 (15%) |

| 5–10 y ago | 78 (20.5%) | 25 (25%) |

| More than 10 y ago | 177 (46.5%) | 50 (50%) |

| Not stated/no diagnosis | 26 (6.8%) | 5 (5%) |

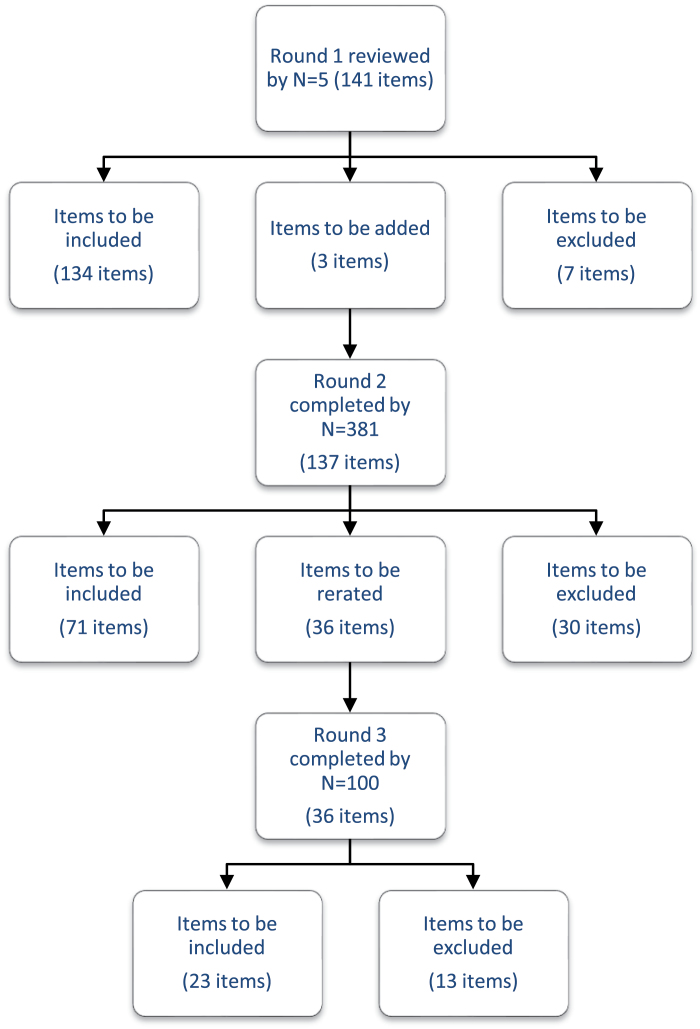

A total of 94 items were retained in the final statement list after being rated as important or essential by >80% of participants. No items reached consensus for not being included (rated as should not be included by >80% of participants). Figure 1 illustrates the number of items which were included, rerated, and excluded at each round of the study.

Fig. 1.

Number of items included, rerated, and excluded at each round of the study.

The final 94 items are shown in the respective 4 categories: defining recovery (n = 19 items), factors that help recovery (n = 43 items), factors that hinder recovery (n = 11 items), and factors that show someone is recovering (n = 21 items). Tables 2–4 show the final statements in their respective category, with percentage of participants who rated the item as essential or important. Items with extremely high consensus obtained in stage 2 (>90%) are highlighted in gray. The percentage in brackets represents the responses of participants who reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis. Only one of the differences in percentage agreements between the sample as a whole and this subgroup was significant (for item “Believing that something good will happen eventually”, x 2(2, n = 100) = 4.822; P = .028), indicating that this item was less important to those in this subgroup than the sample as whole. Supplementary tables show the items that were excluded.

Table 2.

Essential Items for Defining Recovery

| Item | Stage Included | Percentage Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Recovery is the achievement of a personally acceptable quality of life | 2 | 91 (89) |

| Recovery is feeling better about yourself | 2 | 91 (90) |

| Recovery is a return to a state of wellness | 2 | 89 (87) |

| Recovery is the process of regaining active control over one’s life | 2 | 88 (86) |

| Recovery is being happy with who you are as a person | 2 | 87 (86) |

| Recovery is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life, even with the limitations caused by symptoms/experiences of psychosis | 2 | 87 (85) |

| Recovery is about building a meaningful and satisfying life, as defined by the person themselves, whether or not there are ongoing or recurring symptoms or problems | 2 | 86 (84) |

| Recovery is knowing that you can help yourself become better | 2 | 86 (82) |

| Recovery is the unique journey of an individual living with mental health problems to build a life for themselves beyond illness | 2 | 85 (82) |

| Recovery is learning how to live well in the context of continued mental health problems | 2 | 84 (82) |

| Recovery is understanding how to control the symptoms of psychosis | 2 | 83 (83) |

| Recovery is when there is meaning and purpose to life | 2 | 83 (82) |

| Recovery is a process of changing one’s orientation and behavior from a negative focus on a troubling event, condition, or circumstance to the positive restoration, rebuilding, reclaiming, or taking control of one’s life | 2 | 83 (82) |

| Recovery is believing that you can meet your current personal goals | 2 | 82 (81) |

| Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental health problems | 3 | 89 (89) |

| Recovery is a process or period of recovering | 3 | 88 (89) |

| Recovery is a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and roles | 3 | 88 (84) |

| Recovery is accepting that mental health problems/symptoms/experiences are a part of the whole person | 3 | 86 (84) |

| Recovery is regaining optimum quality of life and having satisfaction with life in disconnected circumstances | 3 | 81 (86) |

Table 3.

Factors That Help and Hinder Recovery

| Items That Help Recovery | Stage Included | Percentage Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Having a good, safe place to live | 2 | 96 (95) |

| Having the support of others | 2 | 94 (93) |

| Having a good understanding of your mental health problems | 2 | 94 (89) |

| Living in the kind of place you like | 2 | 91 (92) |

| Knowing what helps you get better | 2 | 91 (89) |

| Knowing how to take care of yourself | 2 | 91 (90) |

| Recognizing the positive things you have done | 2 | 90 (87) |

| Knowing that there are mental health services that do help | 2 | 90 (89) |

| Working on things that are personally important | 2 | 89 (89) |

| Being strongly motivated to get better | 2 | 89 (88) |

| Being able to identify the early warning signs of becoming unwell | 2 | 89 (88) |

| Having a positive outlook on life | 2 | 88 (87) |

| Having a plan for how to stay or become well | 2 | 88 (87) |

| Having goals/purpose in life | 2 | 87 (86) |

| Accomplishing worthwhile and satisfying things in life | 2 | 87 (86) |

| Being able to develop positive relationships with other people | 2 | 87 (83) |

| Knowing that there are things that you can do that help you deal with unwanted symptoms/experiences | 2 | 86 (82) |

| Being able to handle stress | 2 | 85 (85) |

| Feeling part of society rather than isolated | 2 | 85 (83) |

| Being hopeful about the future | 2 | 85 (83) |

| Learning from mistakes | 2 | 85 (85) |

| Accepting that you may have set backs | 2 | 85 (82) |

| Being able to come to terms with things that have happened in the past and move on with life | 2 | 84 (83) |

| Receiving treatment for distressing/unusual thoughts and feelings | 2 | 84 (81) |

| Taking medication as prescribed | 2 | 84 (83) |

| Having healthy habits | 2 | 83 (84) |

| Having a desire to succeed | 2 | 82 (82) |

| Health professionals and service users working collaboratively as equals | 2 | 82 (84) |

| Knowing that even when you do not care about yourself, other people do | 2 | 82 (81) |

| Spending time with people to feel connected and better about yourself | 2 | 82 (80) |

| Being able to fully understand mental health problems/experiences | 2 | 80 (79) |

| Having courage | 2 | 80 (80) |

| Allowing personalization or choice within health services | 2 | 80 (77) |

| Knowing that even when you do not believe in yourself, other people do | 2 | 80 (78) |

| Knowing that you can handle what happens next in your life | 3 | 90 (89) |

| Knowing that all people with experience of psychosis can strive for recovery | 3 | 88 (86) |

| Being able to make sense of distressing experiences | 3 | 85 (82) |

| Making a valuable contribution to life | 3 | 84 (86) |

| Knowing that recovery from mental health problems is possible no matter what you think may cause them | 3 | 83 (82) |

| When services understand/consider the culture and beliefs of the individual | 3 | 83 (82) |

| Continuing to have new interests | 3 | 81 (75) |

| Knowing that you are the person most responsible for your own improvement | 3 | 80 (84) |

| Being able to assert yourself | 3 | 80 (82) |

| Items That Hinder Recovery | Stage Included | Percentage Agreement |

| When health services do not provide help and support to recover | 2 | 84 (83) |

| When a person feels lost or hopeless for much of the time | 2 | 82 (79) |

| When a person feels isolated or alone even when with family of friends | 2 | 81 (77) |

| When a person feels discriminated against or excluded from the community because of mental health problems | 3 | 91 (93) |

| Health professionals who do not accept that their views are not the only way of looking at things | 3 | 89 (93) |

| The impact of a loved one’s mental health problems on their family | 3 | 88 (82) |

| When a person can not find the kind of place you want to live in | 3 | 87 (84) |

| When a person deliberately stopping taking medication although the doctor recommends taking it regularly | 3 | 83 (80) |

| Medication that can affect concentration and memory | 3 | 83 (87) |

| When no one will employ the person due to past mental health problems | 3 | 81 (84) |

| When other people are always making decisions about the person’s life | 3 | 80 (80) |

Table 4.

Factors That Show Recovery

| Item | Stage Included | Percentage Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| When the person is able to find time to do the things they enjoy | 2 | 93 (93) |

| When the person is able to ask for help when they need it | 2 | 92 (90) |

| When the person can trust themselves to make good decisions and positive changes in life | 2 | 92 (88) |

| When the person knows when to ask for help | 2 | 91 (89) |

| When the person is able to take control of aspects of their life | 2 | 90 (87) |

| When the person feels reasonably confident that they can manage their mental health problems | 2 | 90 (87) |

| When the person is able to actively engage with life | 2 | 90 (88) |

| When the person feels like they are coping well with mental or emotional problems on a day to day basis | 2 | 89 (88) |

| When symptoms/experiences of psychosis interfere less and less with daily life | 2 | 88 (87) |

| When the person is able to define and work toward achieving a personal goal | 2 | 88 (87) |

| When fear does not stop the person from living the life they want to | 2 | 85 (80) |

| When the person knows a great deal about coping strategies | 2 | 85 (84) |

| When symptoms/experiences of psychosis do not get in the way of doing things they want or need to do | 2 | 84 (83) |

| When the person finds places and situations where they can make friends | 2 | 83 (82) |

| When the person feels in touch with their own emotions again | 2 | 83 (79) |

| When the person knows a great deal about their own symptoms/experiences | 2 | 82 (80) |

| When the person knows a great deal about their treatment options | 2 | 82 (79) |

| When the person is able to access independent support | 2 | 81 (75) |

| When coping with mental health problems is no longer the main focus of a person’s life | 2 | 81 (76) |

| When the people who are important to someone are actively supporting their mental health treatment | 2 | 81 (83) |

| When symptoms/experiences of psychosis are a problem for shorter periods of time each time they occur | 3 | 85 (84) |

Table 5 includes a summary of the key themes arising from the consultation. Reviewing the themes from this consultation as a whole has highlighted key areas which are important to service users. The 2 most frequently occurring themes were knowledge and support. The knowledge theme included an understanding of mental health problems as well as coping and help seeking skills such as “knowing what helps you get better.” The support theme included items on social support and relationships, as well as support from mental health services. Another important recovery theme was choice and control, including having control of life and symptoms, as well as control and choice surrounding treatment options. A sense of meaning and purpose also appeared to be an important theme with items about having goals, meaning, and purpose in life often being rated as important. Similarly, participants felt that quality of life, even in the context of continued symptoms and mental health problems, was important. Having hope for the future and feeling positive about yourself and your future was an important theme, as well as self-esteem. Finally, having a good, safe place to live was important.

Table 5.

Summary of Themes

| Knowledge | Support | Control and Choice | Meaning and Purpose | Quality of Life | Hope and Positivity | Self-Esteem | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good understanding of mental health problems | Support of others | Regaining active control over one’s life | Building a meaningful and satisfying life | Personally acceptable quality of life | Living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life | Feeling better about yourself | A good, safe place to live |

| Knowing what helps you get better | Mental health services that provide help and support | Personalization or choice within health services | Having goals/purpose in life | Regaining optimum quality of life and having satisfaction with life | Knowing that recovery is possible | Being happy with who you are as a person | Living in the kind of place you like |

| Knowing how to take care of yourself | Receiving treatment for distressing/unusual thoughts and feelings | Understanding how to control the symptoms of psychosis | Development of new meaning and purpose | Finding time to do the things you enjoy | Having a positive outlook on life | Feeling confident | Living in a place you want to live in |

Discussion

This is the first study to reach a consensus about understanding recovery from psychosis. It is also one of a small number of studies which consults services users as experts on their own experiences.26,28 A high level of consensus was reached for a range of items, which were deemed important in defining recovery, understanding what helps and hinders recovery and what would show that someone is recovering. The findings of this study have identified areas of communality among service user definitions, which is a significant addition to the current literature because service user views have traditionally emphasized the idiosyncratic nature of recovery, and provides a pragmatic basis for service planning and provision. In line with other studies involving service user-defined recovery, this study found that the concepts of rebuilding life, self, and hope are essential in defining recovery.4 In contrast with previous studies exploring service user-defined recovery, the Delphi methodology allowed collation of views from a large sample of individuals with psychosis. Although it was agreed that recovery is a unique process which is different for each individual, the Delphi method allows us to identify areas of recovery which appear to be the same for the majority of people.

Regarding definitions of recovery, the highest level of consensus was reached for “recovery is the achievement of a personally acceptable quality of life” and “recovery is feeling better about yourself.” This indicates the importance of routine measures of quality of life and self-esteem when evaluating recovery-orientated services, as well as a focus on working with service users to improve quality of life and esteem rather than a focus solely on symptoms and relapse prevention. Service users endorsed a number of factors which may facilitate their recovery, with the highest levels of agreement reached for environmental factors (such as a safe place to live), social support, and items focusing on personal understanding of mental health problems and recovery. The role of services was also deemed to be important, although it was an awareness that there are services which can help with mental health problems which was rated the highest, rather than the impact of the services or treatments on offer per se. Personal factors such as having goals and purpose, hope for the future, and motivation to succeed were also felt to be important, in agreement with previous research.4,20,21 There was less agreement about what factors may hinder recovery. Participants agreed that lack of services providing help and support would hinder recovery as well as feeling lost, hopeless, or isolated. Participants also highlighted stigma as a potential barrier to recovery, including discrimination such as not being able to gain employment. Interestingly, although a high proportion of people felt that not taking medication as prescribed could hinder recovery, the same proportion of people also felt that side effects of medication, such as concentration problems and memory loss, could also hinder recovery. As highlighted in previous research,31 choice of treatment options, as well as the cost-benefit ratio of specific interventions are important factors for services to consider.

The final section of the study considered which items would demonstrate that someone is recovering. Service users felt that engaging in and enjoying activities was essential, as well as feeling able to make “good” decisions in life. Items around effective help-seeking behaviors (such as knowing when and how to ask for help) and having personal skills to manage or cope with day to life were also important to recovery. Reduced impact of symptoms on daily life was seen as evidence of the recovery process, although this was ninth in the ranked list of factors that show someone is recovering; as such, it may be important for services to rethink their approach to viewing reduction in symptoms as a primary outcome for mental health. Participants did not feel that factors such as reduced hospitalization or relapses were essential for demonstrating recovery.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, recruitment only took place across the North West of England, which may mean that results are not representative of other geographical areas or cultures. Service users in different areas may have access to different types of services and have varying levels of knowledge regarding recovery (indeed, a number of postal questionnaires for this study were returned with notes about the individual’s local service and mentioning that they had never heard about the potential for recovery). Future research could investigate the relationship between general awareness of recovery and personal expectations of recovery. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of diagnoses in the sample. The study was primarily aimed at individuals with experience of psychosis and as a result of initial feedback on the design of the study from a group of service users, a decision was made not to exclude participants based on diagnosis. Instead of using diagnosis as an exclusion criteria, the study asked a screening question about whether the individual defined themselves as having experience of psychosis. As can be seen in the participant characteristics given in table 1, this resulted in individuals who had received a wide variety of diagnoses taking part in the study. Although each question reiterated that the study was asking about relevance to recovery from psychosis, it may be that participants prioritized their own experiences when thinking about the concept of recovery. However, comparisons between consensus ratings observed for the entire sample and those for participants reporting a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis, were generally very similar and only one of the differences was statistically significant; this significant difference was found for “believing something good will eventually happen,” although neither group felt that this item should be included overall. Future studies could explore differences in recovery conceptualizations and goals throughout the recovery process. The majority of participants in this study, particularly in the final stage, had established diagnoses (more than 5 years), so further investigation of the impact of length of time since diagnosis or first experience of psychosis would not have been appropriate. However, it would be useful to understand recovery for those with recent onset of symptoms and experiences compared with those with more established diagnoses and experiences. This would ensure that services are effectively geared toward their client groups. For example, early intervention services may require a different approach to mental health teams for people with more long-term difficulties.

Finally, it is possible, given the nature of psychosis that cognitive impairments could have impaired the ability of participants, to understand the statements presented in the questionnaire and the implications of their responses. While it is possible this could threaten the validity of the study, previous research has suggested that even individuals experiencing acute psychosis retain decision-making capacity.32

Although research has indicated that it is essential for recovery to be defined by service users themselves, it is also important to consider the views of clinicians working in mental health services. Without a shared understanding between clinicians and services users, mental health services will struggle to engage and meet the needs of people with psychosis. Therefore, it would be interesting to ask clinicians to rate similar statements about recovery and examine agreement between the 2 groups.

There are many implications from the results of this study. Service users agreed that an awareness and understanding of recovery was essential. Collaborative approaches to training by clinicians and service users may provide a good vehicle to promote the recovery approach to a mixed audience of clinicians, service users, and carers who want to understand more about recovery from psychosis. This study identifies service user priorities regarding recovery. It is apparent that less focus on reduction of symptoms, relapse, and hospital admissions, in combination with a greater emphasis on improving quality of life and self-esteem, inspiring hope and facilitation of achievement of personal goals, is required for truly recovery-orientated services. Finally, further consideration of the measurement of recovery should be undertaken. This study is the first of its kind to approach a large group of individuals with personal experience of psychosis and ask them what they believe demonstrates that someone is recovering. This may be a useful technique to develop user informed audit tools for evaluating the effectiveness of recovery-orientated services. Identification of treatment and support priorities for recovery followed by routine measurement and audit of these priorities may indicate the effectiveness of services and enable a comparison of services to ensure that there is equality of access to high-quality recovery-orientated services. There is potentially scope to utilize the items rated as essential or important within an audit tool for the benchmarking of clinical services.

Similarly, the items rated as essential or important to “show that someone is recovering” may provide a useful tool for measuring individual recovery. Although there are several measures already developed for this purpose, none have undergone such an extensive process of consulting service users about relevance and importance. Such items could be used as a stand-alone tool for an individualized assessment of the recovery process or developed into a Patient Reported Outcome Measure.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0606-1086).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. We would like to thank the Service User Consultants individual members of the Service User Reference Group, Yvonne Awenat, Rory Byrne, Ellen Hodson, Sam Omar, Liz Pitt, Jason Price, Tim Rawcliffe, and Yvonne Thomas, for their work on this study. The authors also thank Michelle Furphy for coordinating support from clinical studies officers and Ann Parkes and Eileen Law for assisting with preparation of postal questionnaires. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care (Updated Edition). National Clinical Guideline Number 82. London: National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schrank B, Slade M. Recovery in psychiatry. Psychiatr Bull. 2007;31:321–325 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellack AS. Scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: concordance, contrasts, and implications. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:432–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pitt L, Kilbride M, Nothard S, Welford M, Morrison AP. Researching recovery from psychosis:a user-led project. Psychiatr Bull . 2007;31:55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davidson L. Living Outside Mental Illness: Qualitative Studies of Recovery in Schizophrenia. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for Mental Health in England. Guiding Statement on Recovery. London, England: National Institute for Mental Health; 2005. http://www.psychminded.co.uk/news/news2005/feb05/nimherecovstatement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Psychiatric Association. Position Statement on the Use of the Concept of Recovery. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Department of Health. New Horizons: A Shared Vision for Mental Health. London: Department of Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mental Health Network NHS Confederation. Supporting Recovery in Mental Health. London: NHS Confederation; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Future Vision Coalition. Opportunities for a New Mental Health Strategy. London: Future Vision Coalition; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Essock S, Sederer L. Understanding and measuring recovery. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:279–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Law H, Morrison A, Byrne R, Hodson E. Recovery from psychosis: a user informed review of self-report instruments for measuring recovery. J Ment Health. 2012;21:192–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen EY, Tam DK, Wong JW, Law CW, Chiu CP. Self-administered instrument to measure the patient’s experience of recovery after first-episode psychosis: development and validation of the Psychosis Recovery Inventory. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neil ST, Kilbride M, Pitt L, et al. The questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR): a measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis. 2009;1:145–155 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Resnick SG, Fontana A, Lehman AF, Rosenheck RA. An empirical conceptualization of the recovery orientation. Schizophr Res. 2005;75:119–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deegan PE. Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosoc Rehabil J . 1988;11:11–19 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leete E. How I perceive and manage my illness. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15:197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mead S, Copeland ME. What recovery means to us: consumers’ perspectives. Community Ment Health J. 2000;36:315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ridgeway P. Restoring psychiatric disability: learning from first person recovery narratives. Psychiatr Rehabil J . 2001;24:335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith MK. Recovery from a severe psychiatric disability:findings of a qualitative study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;24:149–158 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spaniol L, Wewiorski NJ, Gagne C, Anthony WA. The process of recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2002;14:327–336 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fiander M, Burns T. Essential components of schizophrenia care: a Delphi approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:400–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burns T, Fiander M, Audini B. A Delphi approach to characterising “relapse” as used in UK clinical practice. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:220–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marshall M, Lockwood A, Lewis S, Fiander M. Essential elements of an early intervention service for psychosis: the opinions of expert clinicians. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Langlands RL, Jorm AF, Kelly CM, Kitchener BA. First aid recommendations for psychosis: using the Delphi method to gain consensus between mental health consumers, carers, and clinicians. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:435–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morrison AP, Barratt S. What are the components of CBT for psychosis? A Delphi study. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:136–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Byrne R, Morrison A. Service users’ priorities and preferences for treatment of psychosis:a user-led Delphi study. Psych Serv. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Department of Health. The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st Century. London, England: Department of Health; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 30. British Psychological Society. Recent Advances in Understanding Mental Illness and Psychotic Experiences. Leicester, England: The British Psychological Society; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Byrne R, Davies L, Morrison AP. Priorities and preferences for the outcomes of treatment of psychosis:a service user perspective. Psychosis; 2010;2:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamann J, Leucht S, Kissling W. Shared decision making in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.