Abstract

Noncognitive symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias include psychosis, mood disturbances, personality changes, agitation, aggression, pacing, wandering, altered sexual behavior, changed sleep patterns, and appetite disturbances. These noncognitive symptoms of dementia are common, disabling to both the patient and the caregiver, and costly. Primary care physicians will often play a major role in diagnosing and treating dementia and related disorders in the community. Accurate recognition and treatment of noncognitive symptoms is vital. A brief, user-friendly assessment tool would aid in the clinical management of noncognitive symptoms of dementia. Accordingly, we reviewed the available measures for their relevance in a primary care setting. Among these instruments, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire seems most appropriate for use in primary care and worthy of further investigation.

Noncognitive symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias include psychosis (delusions, hallucinations), mood disturbances (depression, euphoria, irritability, anxiety), personality changes (disinhibition, apathy), agitation, aggression, pacing, wandering, altered sexual behavior, changed sleep patterns, and appetite disturbances.1 These noncognitive symptoms occur at some time during the course of illness in over 50% of individuals with dementia.2

The noncognitive symptoms of dementia are not only distressing and, at times, dangerous for the patient with dementia, but also confer a high degree of burden to those charged with caregiving.3,4 Furthermore, psychiatric symptoms of dementia have been found to increase rates of institutionalization5 and overall financial costs.6 Successful intervention with behavioral and pharmacologic therapies may help to delay nursing home placement and improve the quality of life for the individual with dementia and their caregivers. It may also be possible to prevent or improve caregiver depressive syndromes through more effective treatment of the noncognitive symptoms of dementia.

Primary care providers, rather than mental health specialists, are the ones most likely to evaluate the growing number of patients with memory disorders complicated by behavioral and psychiatric symptoms. A recent survey of primary care physicians indicated a high degree of interest in learning more about the management of dementia.7 Careful assessment of the noncognitive symptoms of dementia is imperative in order to first develop an appropriate differential diagnosis and then employ successful treatment strategies. Although primary care physicians may be familiar with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)8 as a screening tool of general cognitive impairment, the MMSE does not assess noncognitive symptoms. Many primary care providers lack the appropriate clinical tools and experience to accurately assess the behavioral and psychiatric complications of dementia.

A user friendly and well-validated measure would be a helpful first step for primary care providers to accurately identify the symptoms in a timely manner so that effective treatments can be employed. Repeat administration of the measure after a designated period of time would then help to monitor treatment response. In order to assist with accurate identification of the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia, a variety of scales and measures have been developed and validated. These measures are often used in clinical trials of pharmacologic agents for the treatment of noncognitive symptoms of dementia.

In determining the most appropriate measures to be used in assessing noncognitive symptoms of dementia in the primary care setting, it is helpful to consider the methodological challenges involved in measuring treatment-associated changes in behavior and psychiatric symptoms.1 The origin of the instrument used is quite relevant. For example, some scales used for assessing psychiatric symptoms and behaviors in primary psychiatric syndromes are not necessarily relevant or accurate for such symptoms in dementia. The purpose of this article is to review the literature on dementia-specific measures to identify which ones may be best suited or adapted for use in the primary care setting.

METHOD

The authors conducted a Medline search from January 1966 to January 2002 using the keywords dementia, agitation, measures, elderly, psychosis, and English language. The list of all pertinent articles was reviewed for relevance to description or use of a scale to measure psychiatric symptoms in dementia. Articles were included for final review if they met at least 1 of the following 3 inclusion criteria: validation of a particular psychometric scale, clinical trial in which a scale was used to determine efficacy of a particular intervention for noncognitive symptoms of dementia, and review article summarizing key features and properties of psychometric scales to measure noncognitive symptoms of dementia.

The authors then systematically reviewed the included articles and compared the key properties of the measures. The key properties were determined based on suggestions from Cummings and Masterman1 and included informant and method, brevity (number of items and average time to complete), behaviors assessed, and target population. The instruments were examined for evidence of reliability and validity. Finally, we conducted a citation search in the Web of Science's (WOS) Science and Social Sciences index to identify how many times a key article representing the validation of a measure was cited in other articles in journals indexed in the WOS.

RESULTS

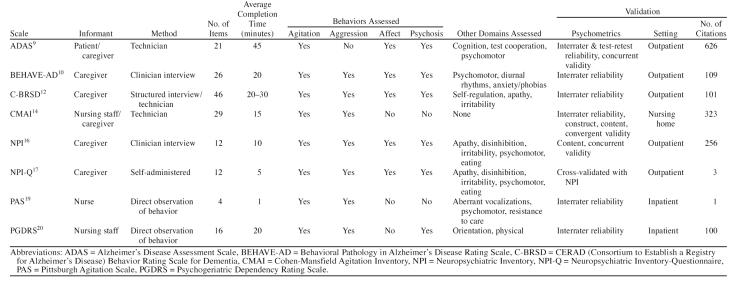

The literature search revealed 193 articles relevant to the use of psychometric scales for measuring behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Of these, 21 articles, representing 8 scales, met at least one inclusion criterion and were systematically reviewed in order to obtain detailed information about the previously mentioned parameters. Table 1 summarizes the parameters for the following 8 scales, each with at least one validity study. Brief descriptions of each scale are included here.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 8 Scales for Assessing Noncognitive Symptoms of Dementia

The Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) was designed from a list of the most common clinical symptoms seen in a series of 31 patients with Alzheimer's disease.9 This instrument has both cognitive and noncognitive sections. The cognitive section has 11 parts that test components of memory, praxis, and language. The noncognitive section includes 10 parts and assesses depression, agitation, psychosis, and vegetative symptoms but omits anxiety, aggression, and apathy. All forms of hallucinations are combined into one category. The noncognitive section rates behaviors on a 0–5 scale of severity and an “×” if not assessed. The cognitive section is commonly used to assess change in cognitive function in pharmaceutical trials. A technician, using a patient and caregiver as informant, administers this scale, which takes approximately 45 minutes to complete. This measure was designed specifically to assess changes in cognitive function and behavioral symptoms in pharmacologic clinical trials.

The Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) is one of the earliest behavior rating scales to be used in Alzheimer's dementia.10,11 The items were taken from a chart review of 57 outpatients with Alzheimer's disease. It was designed to prospectively follow behavioral symptoms and to measure behavioral symptoms in pharmacologic trials of patients with Alzheimer's disease. The BEHAVE-AD includes the assessment of symptoms and a global rating of caregiver distress. A total of 25 symptoms in 7 clusters are rated: paranoid and delusional ideation, hallucinations, aggressiveness, activity disturbances, diurnal rhythm disturbances, affective disturbances and anxieties, and phobias. Caregivers rate behavioral symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks on a 0–3 scale. The maximum score is 75. The caregiver also determines a global assessment of caregiver distress on a scale of 0–3. The BEHAVE-AD has been found to be sensitive to changes in behavior and suitable for measuring effects of medications.

The CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease) Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (C-BRSD) was developed out of the large CERAD initiative.12 This instrument is composed of 46 questions rated on a 5-point severity scale. The items were taken from existing scales and designed to be administered to an informant who knows the patient well. The ratings measure behavioral symptoms over the past month. The original sample consisted of 303 patients attending 16 Alzheimer's centers within the United States.13

The Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) was designed primarily for nursing home use.14,15 A 7-point rating scale is used to assess the frequency of 29 individual behaviors. The behaviors are broken down into 2 primary dimensions: aggression and agitation. Aggressive behaviors are categorized as verbal, physical, or sexual. Agitated behaviors are categorized as physical or verbal. The measure requires approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete. Caregivers, usually nurses or certified nursing assistants in the nursing home setting, rate the behaviors but need training first. The maximum score is 207. The CMAI can be administered with a short or long form and is an observational scale.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was developed by Cummings et al.16 in order to thoroughly assess 12 neuropsychiatric symptom domains common in dementia. The NPI was originally designed to help distinguish between different causes of dementia. This is a brief semistructured interview administered by a clinician to a caregiver rating the severity and frequency of the behavior. Severity of behavior is scored (1–3) and frequency of behavior is scored (1–4). A maximum score of 12 (frequency × severity) is possible for each domain. Caregivers rate their own level of distress 0–5 for each domain. The NPI has “demonstrated stage specific trends in neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD patients.”17(p234) Test-retest and interrater reliability have been demonstrated as well as concurrent validity with items from the BEHAVE-AD and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.18

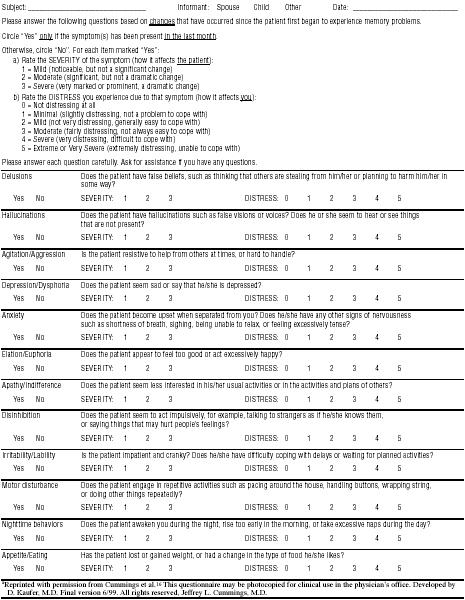

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire (NPI-Q) was designed to expand the applicability of the NPI to routine clinical settings.17 Another version was designed specifically for nursing home use. The NPI-Q was cross-validated with the NPI in 60 Alzheimer's patients.17 The NPI-Q is a brief, informant-based, 2-page, self- administered assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and associated caregiver distress (see Appendix 1). Written instructions are provided to the caregiver who then uses anchor points to rate symptom severity and caregiver distress. There is a screening question from the NPI that covers each of the 12 core symptom manifestations. If the screening question is answered “yes,” symptoms present are checked, and the severity is rated on a scale of 1–3. Frequency of symptoms is not assessed. The rationale for severity ratings only is that caregiver distress is more highly correlated with severity than frequency. In addition, severity and frequency scores are highly correlated on the NPI. Total scores range from 0–36 (sum of individual symptom scores). Caregiver distress is rated 0–5 for each symptom domain (total score is 0–60).

The Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (PAS) assesses agitation in patients with dementia.19 Four behavior groups are measured on an intensity scale of 0–4: aberrant vocalizations, motor agitation, aggressiveness, and resisting care. The score reflects the most severe behavior within each behavior grouping. Therefore, an improvement in PAS score may reflect an improvement in a particularly severe behavior, but other symptom domains of agitation may still exist. Interrater reliability exceeded 0.80. Validity was assessed by comparing the PAS score with the number of clinical interventions required. The scale takes less than 1 minute to administer and is rated by direct observation over a period of 1 to 8 hours by clinical staff. This scale was designed for use in the inpatient or nursing home setting.13

The Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale (PGDRS) includes items developed around the concept of dependency: “nursing time demanded by patient.”20 The instrument was designed to use the knowledge base of the nurses to examine orientation, behavior, and physical problems (e.g., mobility, hearing, vision, speech) in geriatric psychiatry inpatients. Each of 16 behaviors is rated as occurring never, occasionally (2 of 5 days or less), or frequently (3 of 5 days or more). Reliability and validity information was originally collected on over 600 patients. The scale was found to have good face validity and reliability. The PGDRS takes about 20 minutes to complete, and there is also a shorter version of the scale.13

DISCUSSION

The results of the literature review have revealed a number of reliable and validated scales used to assess the frequency, severity, and caregiver impact of psychiatric symptoms in dementia. However, most of these measures have been used in research or tertiary, specialist settings and not in the primary care practice setting. The following discussion helps to clarify the benefits and shortcomings of the various measures when considering their use in primary care, where brevity and ease of use are of paramount importance given the competing demands of today's primary care medical world.

Based on the key properties, with added weight given to brevity, frequency of use in clinical studies, practical application in routine practice settings, and allowing for caregiver input to help evaluate symptom severity and effect on caregivers, the NPI-Q appears to be the most useful measure of psychiatric symptoms of dementia in the primary care setting. This measure may be most applicable to the primary care setting based on the issues of brevity, self-administration, degree of validation, and assessment of multiple behavioral and psychological symptom domains.

Compared with the NPI-Q, the other measures reviewed have certain characteristics that limit their utility in primary care. Although a thorough measure of pertinent symptoms, the BEHAVE-AD takes approximately 20 minutes to administer, which would limit its applicability to a busy primary care setting. The limitation of the CMAI is its focus exclusively on agitation and the exclusion of mood or psychosis ratings. In addition, its length and the requirement for caregiver training further limit its applicability to the general medical setting. The length of time required to administer the C-BRSD and the requirement for a trained examiner limit its utility in the general medical setting. The length of the ADAS and the incomplete assessment of behavioral and psychological symptoms limit its applicability in the general medical setting. The PAS, although well validated and useful in monitoring response to treatment, is primarily an assessment of behavioral disturbance in inpatients but not outpatients in primary care. Finally, the PGDRS appears to be useful for the nursing home and inpatient settings and not the outpatient general medical setting.

Another important issue is that the source of information may result in different conclusions about the existence or frequency of a particular noncognitive symptom. For example, the NPI and BEHAVE-AD are caregiver-based instruments that “may be biased by caregiver mood, the lack of sophistication of the caregiver as an observer, or the previous relationship of the caregiver and patient.”1(p25) However, despite this potential bias, when assessing the severity and frequency of noncognitive symptoms, the input of the primary caregiver, who will be most affected by the individual's psychiatric and behavioral symptoms, needs to be adequately incorporated. Lack of awareness, in addition to poor memory, is a hallmark of Alzheimer's dementia. This precludes exclusive report by the patient. Often there will not be another objective observer besides the primary caregiver who knows the patient in as much depth as is required to get a reliable report of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms. These measures assess the impact of noncognitive symptoms on the caregiver's own distress, which may predict the likelihood of premature institutional placement.

Finally, Cummings and Masterman1 point out that measuring change in behavior as a consequence of drug treatment can be very difficult. Numerous issues must be considered, including the ability to distinguish treatment response from spontaneous remission of symptoms, the amount of change in an instrument's score that is clinically meaningful, and the specific criterion symptoms on which treatment effects will be assessed.1

In summary, the NPI-Q appears to be a valid and reliable assessment tool applicable to a primary care practice setting. This is based on the review of the literature to date and does not take into consideration implementing such a measure in primary care. There will most likely be a number of barriers that will impede successful implementation of such a measure in primary care. These barriers may be due to system issues or particular characteristics or biases of the physician, patient, or family. The NPI-Q warrants further study in primary care, first assessing the instrument's utility and then assessing whether it directly or indirectly affects practice patterns (e.g., detecting problem noncognitive symptoms and adequately treating these symptoms when identified).

In order to enhance the care of patients with dementia in the primary care setting, ultimately a chronic disease system of care is required. Such systems have already been developed for other chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure21 and depression.22 A system of care includes a method for identifying patients with dementia, assessing behavioral and psychiatric symptoms, implementing treatment, and using a care manager who facilitates communication of treatment response among the patient, caregiver, primary care physician, and, when necessary, a consulting specialist. The key for communication in these systems of care is a practical, reliable, and valid assessment tool. This is the imperative for further evaluation of tools such as the NPI-Q.

Appendix 1.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnairea

Footnotes

The authors report no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Cummings JL, Masterman DL. Assessment of treatment-associated changes in behavior and cholinergic therapy of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998 59suppl 13. 23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos C, Steinberg M, and Tschanz JT. et al. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 157:708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deimling GT, Bass DM.. Symptoms of mental impairment among elderly adults and their effects on caregivers. J Gerontol. 1986;41:778–784. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabins PV, Mace NL, Lucas MJ.. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA. 1982;248:333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele C, Rovner B, and Chase GA. et al. Psychiatric symptoms and nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1990 147:1049–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Assessment of disruptive behavior/agitation in the elderly: function, methods and difficulties. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995 8suppl 1. 52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BE, Barry PP, and Renick N. et al. Physician confidence and interest in learning more about common geriatric topics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 49:963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR.. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL.. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Franssen E.. Stage specific incidence of potentially remediable behavioral symptoms in aging and AD: a study of 120 patients using the BEHAVE-AD. Bull of Clinical Neuroscience. 1989;54:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Borenstein J, and Salob SP. et al. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987 48suppl 5. 9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Mack JL, and Patterson MB. et al. The behavioral rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995 152:1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Lawlor B, and Craig S. Assessment Scales in Old Age Psychiatry. London, England: Martin Dunitz Ltd. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield. Agitated behaviors in the elderly. 2: preliminary results in the cognitively deteriorated. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:722–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS.. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol. 1989;44:M77–M84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.m77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, and Gray K. et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994 44:2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufer D, Cummings JL, and Ketchel P. et al. Validation of NPI-Q: a brief clinical form of the NPI. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000 12:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mega MS, Cummings JL, and Fiorello T. et al. The spectrum of behavior changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996 46:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J, Burgio L, and Kollar M. et al. The Pittsburgh Agitation Scale: a user-friendly instrument for rating agitation in dementia patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994 2:60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson IM, Graham-White J.. Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale (PGDRS): a method of assessment for use by nurses. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:558–565. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Carlson B, and Kopp Z. et al. Effect of standardized nurse case-management telephone interventions on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002 162:707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, and Williams JW Jr. et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001 39:785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]