Abstract

Partnerships between HIV researchers and service providers are essential for reducing the gap between research and practice. Community-Based Participatory Research principles guided this cross-sectional study, combining 40 in-depth interviews with surveys of 141 providers in 24 social service agencies in New York City. We generated the Provider-Researcher Partnership Model to account for provider- and agency-level factors’ influence on intentions to form partnerships with researchers. Providers preferred “balanced partnerships” in which researchers and providers allocated research tasks and procedures to reflect diverse knowledge/skill sets. An organizational culture that values research can help enhance providers’ intentions to partner. Providers’ intentions and priorities found in this study may encourage researchers to engage in and policy makers to fund collaborative research.

Keywords: CBPR, practitioner–researcher partnership, HIV research

A burgeoning literature, grounded in the paradigm of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), has emphasized involvement of front-line social and health services providers (“providers,” e.g., social workers, nurses, medical doctors, counselors, health educators) in all aspects of health research (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). Providers from a variety of professional disciplines share a common purpose of delivering services directly to individuals to ameliorate health and social conditions. Services may be medical, psychosocial, and/or psychological depending on the needs of the individual patient/client. Inclusion of providers in research may help close the ideological gap between public health interventions developed exclusively by researchers and community-focused interventions, which integrate provider input, priorities, and wisdom (Layde et al., 2012). Provider–researcher partnerships are exceptionally important because they can also help reduce the 15 to 20 year gap between the development of innovative evidence-based practices (EBPs) and their subsequent implementation in community agencies (Bellamy, Bledsoe, Mullen, Fang, & Manuel, 2008; Owczarzak & Dickson-Gomez, 2011). Closing this gap will improve the quality of health services by ensuring that people will receive a high standard of care and have access to interventions shown to be effective, instead of untested practices without empirical support (Cashman et al., 2008; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Kazdin, 2008; Leasure, Stirlen, & Thompson, 2008; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Spector, 2012; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

Provider–researcher partnership can help reduce costs associated with participant recruitment (Flicker, 2006; McAllister, Green, Terry, Herman, & Mulvey, 2003; Parker et al., 2007), enhance providers’ adoption and delivery of EBPs (Chagnon, Pouliot, Malo, Gervais, & Pigeon, 2010; Owczarzak & Dickson-Gomez, 2011; Pinto, Yu, Spector, Gorroochurn, & McCarty, 2010), and improve dissemination of research findings (Galea et al., 2001; Parker et al., 2005). Therefore, partnership between researchers and providers is a central aspect of health research worldwide funded by international, federal, and private institutions (Kellogg Foundation, 2010; National Institute of Health, 2010; USAID, 2012; World Bank, 2009). Even though provider–researcher partnership has been widely encouraged, providers’ perspectives on partnership have received modest attention in the literature. Theoretically and empirically based explanatory models for provider–researcher partnership are not available. We thus conducted the present research with providers of HIV-related services to develop an explanatory model of provider–researcher partnership reflecting providers’ professional realities. Such a model will inform providers’ and researchers’ decision making around partnership and to help guide policy makers’ decisions around collaborative research funding. Grounded in provider-level qualitative and quantitative data, our Provider–Researcher Partnership Model comprises key elements of collaboration that can be tested in different contexts. The model focuses on HIV prevention research. However, since HIV-related services often include many other types of services (e.g., substance abuse treatment, primary care, housing), this model holds relevance for partnerships in other areas of research. Our model sets the stage for future research examining the impact of partnership on service and patient outcomes.

Provider–Researcher Partnerships

Provider involvement in research has been described in Community-Based, Participatory, Action, and Empowerment paradigms (Gillies, 1998; Harper & Carver, 1999; McKay & Paikoff, 2007; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Roe, Guiness, & Rafferty, 1997; Sullivan & Kelly, 2001; Vander Stoep, Williams, Jones, Green, & Trupin, 1999). CBPR, a widely acknowledged paradigm, calls for partnership among diverse groups of people who identify as residents, service consumers and providers, clergy, researchers, and so on (Israel et al., 1998). Here, we focus on partnerships between researchers and providers because providers involved in research have a crucial role in adoption and implementation of EBPs (Pinto et al., 2010).

A descriptive literature exists defining how providers and researchers come together to conduct research, and what providers expect and hope to gain from research partnerships (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005; McKay & Paikoff, 2007). This literature characterizes partnership as a synergistic endeavor (Lasker, Weiss, & Miller, 2001) where providers assist in specification of aims and study design, developing recruitment materials and data collection strategies (Edgren et al., 2005); implementing and testing interventions (Paschal, Manske-Oler, Kroupa, & Snethen, 2008); collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data (Cashman et al., 2008; Krieger, 2001); and disseminating findings (Galea et al., 2001; Rashid et al., 2009; Spector, 2012). There is a paucity of studies examining what facilitates and/or hampers partnership, particularly provider- and agency-level factors (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011). Recent studies (Khodyakov et al., 2011) neglect crucial factors that may influence partners’ decision making, as discussed below.

Provider-Level Factors Influencing Intentions to Partner

Widely accepted behavioral theories (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) suggest that a person’s intention to change a behavior is a key predictor of that person’s likelihood of engaging in a new behavior or maintaining a preexisting one (e.g., safer sex, seeing a physician, smoke cessation). Behavioral theory also applies to providers’ professional behaviors, such as intention to partner with researchers or to use EBPs (Michie et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2007). Therefore, it is helpful to study providers’ intentions to partner with researchers as a way to gain insight into actual partnerships.

Key factors that influence providers’ intentions and behaviors include knowledge about and opinions toward research and EBPs, and expectations of and attitudes toward researchers themselves. Providers’ knowledge/skills around research-related tasks/procedures, and about EBPs, may influence their willingness to engage in research partnerships. Providers who understand how to identify/implement EBPs may have had greater exposure to research. Their familiarity with research methods is thus associated with engagement in research partnerships (Collins, Harshbarger, Sawyer, & Hamdallah, 2006; Denis, Lehoux, Hivon, & Champagne, 2003). Similarly, positive attitudes facilitate partnering and negative ones hamper it by diminishing providers’ motivations (Aarons, 2005; Brown, Wickline, Ecoff, & Glaser, 2009; Spoth & Greenberg, 2005). Whereas some providers view research as relevant to practice, others view research as biased, unethical, and not applicable to practice (Knudsen, Ducharme, & Roman, 2007; Nelson & Steele, 2007). Providers holding negative attitudes toward research often rely on intuition or untested interventions instead of EBPs (Nelson & Steele, 2007; Valdiserri, 2002). Providers who are aware of past ethical breaches in research are less inclined to become involved in research (Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St. George, 2002). Furthermore, providers’ perceptions of researchers’ social manners and availability are associated with their opinions and expectations about partnerships (Ochacka, Janzen, & Nelson, 2002; Stoecker, 1999; Wallerstein, 1999). Providers perceiving researchers as poor communicators and as disinclined to address power dynamics are reluctant to partner with researchers (Baumbusch et al., 2008; Flicker, 2006; Galea et al., 2001). Contrastingly, providers are motivated to partner with researchers whom they perceive as experts, as having positive social manners, and as willing to assist providers and agencies build capacity for research (Carise, Cornely, & Ozge, 2002; Castleden, Garvin, & First Nation, 2008).

Agency-Level Factors Influencing Providers’ Intentions to Partner

Although many providers may wish to engage in research, agency characteristics may prevent involvement. Agencies with insufficient budgets, physical space, equipment, and lacking technological resources hamper providers’ intentions to partner. Agencies that lack human resources render providers less willing or less able to partner, especially in agencies where staff time is dedicated exclusively to reimbursable activities (e.g., counseling sessions; Flicker, 2006; Galea et al., 2001; Israel et al., 2006; Krieger, Takaro, Song, & Weaver, 2005). Overall, small-sized agencies lack space to host research activities, technology capacity (e.g., internet access), private spaces for research interviews, and funding to implement EBPs (Lantz, Viruell-Fuentes, Israel, Softley, & Guzman, 2001; Wells et al., 2006).

Advancing the Science of Provider–Researcher Partnership

The literature mentioned above reveals key factors that influence partnership. However, due to several reasons, a critical gap exists—no explanatory model is available emphasizing the role of provider- and agency-level factors in providers’ intentions to partner (Schulz, Krieger, & Galea, 2002; Thompson et al., 2009). Provider–researcher partnership is a strategy used globally that still lacks a strong theoretical base (Ansari, Philips, & Hammick, 2001; Cashman et al., 2008; Claiborne & Lawson, 2005; Reback, Cohen, Freese, & Shoptaw, 2002). Single-item survey questions have been used to measure providers’ intentions to partner. However, dichotomous (i.e., “are you interested in research partnership”) or continuous (i.e., “to what extent would you like to partner”) variables cannot capture the complexity of providers’ decision making. Given the wide appeal and positive outcomes of provider–researcher partnership, its practice most likely will prevail in future public health research (Suarez-Balcazar, Harper, & Lewis, 2005; Wright, Roche, Von Unger, Block, & Gardner, 2010) and thus needs to be empirically explained.

Our contribution to this literature is the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model. First, guided by CBPR, we developed a partnership with providers so that this study’s methods and relevance could be supported by providers’ perspectives, a critical concern. Our model is grounded in theoretical concepts from sociology, psychology, and public health. We used a mixed methods approach, a national research priority with potential to enhance methodological rigor and health research findings (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Forty in-depth interviews with 20 providers revealed the context and content of decision making about partnering, providers’ characterization of “partnership,” and factors that influenced their intentions to partner. Based on the qualitative data, survey questions were developed and administered to 141 providers. The main outcome of interest, that is, intention to partner, was measured using vignettes that explored willingness to partner in two contrasting types of partnerships. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine associations between the outcome and provider- and agency-level factors. By emphasizing providers’ perspectives, the resulting explanatory model has potential to guide improvements in partnership implementation and impact on public health.

Integrated Theoretical Framework

We ground our model of “research partnership” in Balance and Coordination Theory (Litwak, Meyer, & Hollister, 1977; Litwak, Shiroi, Zimmerman, & Bernstein, 1970). This theory suggests that collaboration between researchers in large organizations (e.g., universities) and providers in smaller settings (e.g., community agencies) can complement each other’s needs and interests. Whereas universities have research infrastructure and funding, community agencies can recruit research participants, test interventions, and disseminate EBPs. Balance and coordination of diverse knowledge sets are achieved by combining providers’ and researchers’ complementary expertise to write research proposals, specify aims, collect data, recruit participants, analyze data, write and present results, and so on. Though providers and researchers may have overlapping knowledge/skills, researchers are typically more knowledgeable about scientific methods whereas providers can prioritize research with implications for their practice, recruit participants, and implement interventions. Partnership is thus shaped by the distribution of research tasks/procedures and resources, including specialized knowledge and expertise allocated between providers and researchers.

Theory of Balance and Coordination is complemented by psychological and organizational theories, which suggest that providers’ willingness to collaborate, that is, to balance and coordinate research tasks and procedures alongside researchers, is influenced by both provider-and agency-level factors. Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior Theories (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) define key cognitive constructs that can influence providers’ intentions to partner and coordinate research tasks and procedures, such as knowledge/skills, opinions and attitudes, and expectations about researchers; and also providers’ intentions to use EBPs (Michie et al., 2005). A meta-analysis of research using these theories suggest that explanatory models, such as the one we are presenting here, can explain on average between 40% and 50% of the variance in intention and between 19% and 38% of the variance in behavior (Sutton, 1998). Behavioral theories suggest that providers’ demographics and professional environments influence partnership by impacting on providers’ knowledge/skills, opinions, and expectations (Perkins et al., 2007).

Community agencies in different locations vary by size (e.g., number of employees), by capacity (e.g., types of services), and by culture (e.g., research focused). Therefore, along with providers’ personal characteristics, agency size and capacity may influence providers’ ability to coordinate and balance research tasks and procedures and ultimately their intentions to partner. Agency cultures that encourage the use of research findings (e.g., EBPs) may also encourage providers’ to partner in research. However, it is unfeasible for agencies of any size/capacity to create opportunities for all providers to engage in research. Organizational theory suggests that this situation can be remedied by developing an agency culture (Hatch & Cunliffe, 2006) that encourages providers’ direct involvement whenever possible and supports those providers to influence the intentions and practices of peers who may be reluctant to partner.

The aforementioned theories collectively formed the basis for the present study. Theory of Balance and Coordination informed our hypothesis that partnerships flourish and persist over time when academic researchers and providers engage in mutually beneficial exchanges of knowledge and resources. Behavioral theories (reasoned action and planned behavior theories) informed our development of the interview protocol and selection of provider-level variables that were subsequently entered into the structural equation model by identifying the constructs that have been shown to motivate providers’ practices. Organizational theory likewise guided our interview protocol and selection of agency-level variables by identifying the constructs that have been shown to be associated with changes in agency practices.

Method

Overview of the Study

Provider–researcher partnership helps generate findings that are more applicable to practice than researcher-driven approaches (Cashman et al., 2008; Green, 2010; Israel et al., 1998; Pinto, McKay, & Escobar, 2008). Thus, starting in 2006–2007, we used CBPR principles to develop a diverse partnership network, the Implementation Community Collaborative Board (ICCB), including researchers, service consumers, and providers. ICCB members work and/or receive services in many of the agencies that participated in this study. The ICCB uses group dynamics to achieve its mission to integrate practice wisdom in health research. To ensure optimal integration and power sharing, we have used dialectic processes to exchange our diverse knowledge sets, mutual support to overcome social and professional differences, and problem solving to achieve consensus on distribution of research tasks (Authors, 2011). This study follows recommendations made by ICCB providers to prioritize the development of empirical models to explain their involvement in research.

CBPR encourages researchers to fill in conceptual and empirical gaps in underdeveloped research areas and to produce findings with direct practical implications (Israel et al., 1998). A team of two researchers and six ICCB providers conducted brainstorming sessions to define a research aim that would help us explain provider involvement in research. We thus conducted the present, mixed methods study. The first phase included in-depth interviews with 20 providers in 10 agencies in New York City. Data from these interviews guided the development of a provider survey. To preserve the meaning of the qualitative interviews, we developed survey questions based on the themes identified in providers’ narratives which reflected both concrete elements of the narratives and the actual words used by participants. In a second phase, we administered this survey to a new sample of 141 providers in 24 agencies also in New York City. Data collected with this survey were used to develop the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model. Participating agencies comprised a diffusion system—agencies in the same geographic area offering similar services and innovations (e.g., EBPs) to many of the same consumers (Rogers, 1995). Interviewing providers offered a narrative of factors that influenced providers’ intentions to partner. Factors that were relevant in the narratives are described below.

Design

Approval for this study was received from the appropriate Institutional Review Board. We used a sequential mixed methods approach (Creswell, 2009). First, we collected qualitative data followed by survey data collection. This sequential knowledge building is ideal for filling gaps in underdeveloped research areas and for generating findings that facilitate organizational change (e.g., involve providers in research; Morse, 2003; Newman, Ridenour, Newman, & DeMarco, 2003). We thus conducted 40 in-depth interviews, two with each of 20 providers. Data from interviews helped us understand the organizational environment (e.g., culture, context) of agencies where providers were situated. The data were used to operationalize “provider–researcher partnership” and to develop the basic structure of the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model. These data helped identify factors that influence providers’ intentions to partner. We then collected survey data from 141 providers. Though data collection was sequential, we used a concurrent approach to data analysis and interpretation of mixed data (Creswell, 2009). Qualitative data were crucial for revealing dimensions (i.e., exploratory stance) that influenced providers’ intentions to partner. These dimensions guided survey questions subsequently used in an SEM to explain (i.e., confirmatory stance) providers’ intentions to partner. Interpretation of the SEM was bolstered by the qualitative data. This methodological triangulation thus enhanced the internal validity of results (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003); involvement of providers ensured mutual creation of knowledge (Creswell, 2009) and specificity in data interpretation (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000).

The qualitative phase of the present study has been published elsewhere (Authors, 2009). A summary of qualitative methods is presented below as background for the quantitative phase. For didactic purposes, we describe the qualitative and quantitative phases sequentially; however, we show in the sections below how data analyses and interpretation occurred concurrently.

Qualitative Phase

For this phase, 20 providers were recruited from 10 agencies to give in-depth interviews about their involvement in HIV research. These 10 agencies were selected randomly from a list of agencies funded by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYCDHMH). To be included in this phase of the study, providers were required to have provided HIV-related services and to have partnered with researchers to conduct research. Prior to the interview, providers were asked to check which research-related tasks and procedures (e.g., data collection) they had been involved from a comprehensive list of tasks/procedures. The interviews started with the question, “Could you please describe your [most/least] successful collaboration in an HIV prevention research project?” Follow-up questions included the following: (a) In your opinion, what constitutes an ideal research partner in terms of individual researchers and institutions? (b) Please describe the key elements of [most/least] successful collaborations? (c) What steps are needed to build successful partnerships? (d) Please describe with examples what you perceive as barriers and facilitators to collaboration.

Providers gave two semistructured interviews. The first focused on their involvement in a partnership they perceived to have balanced and coordinated distribution of research tasks/procedures. The second focused on projects providers identified as lacking balance and coordination. Grounded in our integrated framework, the interview focused on providers’ personal characteristics and perspectives on distribution of research tasks/procedures—specifying aims and methods, choosing measures, analyzing and interpreting data, and disseminating findings. Participants described different types of partnerships.

Two coders with extensive front-line work experience independently coded the data until saturation occurred and no new themes emerged (Charmaz, 2000), using well-established procedures for thematic analysis (Neuendorf, 2002). We used a modified form of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), where our theoretical orientations, analytic training and skills, and experience with the data informed and guided data analysis (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Coders reached 100% agreement on basic units of analysis organized as a codebook. Coders marked all transcripts adhering to this codebook. They selected interview passages that best represented providers’ characterization of partnership and the conditions that influenced their intentions to partner. Each interview was read line-by-line, examining text about what factors facilitate and hamper collaboration. The coding was guided by behavioral and organizational theories to select those factors that reflected provider-level and agency-level constructs, respectively. Coders found these variables in all transcripts, and they independently identified them.

Data ascertained from questions asking participants to describe contrasting partnerships indicated that “partnership” was perceived as a process where coordination of research tasks/procedures could be unbalanced or balanced. We used prompts asking providers to provide details about these two basic types of partnerships. In unbalanced partnerships, providers perceived researchers as unavailable and unaware of providers’ needs. Unbalanced partnerships were described as fraught with disagreements on the focus of research, ownership over findings and data, and on who would likely benefit from the partnership. In balanced partnerships, providers described projects where tasks and procedures were perceived as more equitably coordinated between researchers and providers. Participants corroborated factors found in the literature and which appeared to influence their decisions to partner. Table 1 presents condensed versions of narratives that coders agreed represented the full range of in-depth interviews and the overall sensibility expressed in them. Behavioral theories above suggest that demographics and agency-level variables influence partnership through providers’ knowledge/skills, opinions, and expectations (Perkins et al., 2007). Therefore, Table 1 shows salient passages reflecting these constructs of the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model.

Table 1.

Providers’ Knowledge/Skills About, Opinions, and Expectations Around Research Partnerships.

| Unbalanced partnership | Balanced partnership | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and skills | “You know, are we there to do the service, or to gather data? I know that when we get education it’s magnificent. But often it’s not there. … We know to ask for capacity building and technical assistance to adapt evidence-based practices to our consumers. We have had issues about cultural competence.… There also was some fighting about how much data you collect when people are in crisis … too many unanswered questions …” | “I think that we learned about specific research things, specific research tasks or skills. Our staff learned that research could make their work more impactful … the researcher was forthright in his assistance both in terms of helping our agency build capacity to conduct research, as well as our capacity to implement evidence-based practice. One of the outcomes of the partnership was a suggestion about what we needed to do to fill EBP gaps.” |

| Opinions | “My biggest gripe about [partnership] is when the researcher is asking for too much. For example, when we first got involved with the current project, they wanted us to fill out eighteen pages of questions. That is an example of research gone wild.… We were dealing with people with HIV/AIDS … there’s sensitivity that has to be employed … to bring a researcher in who doesn’t have that knowledge could be detrimental to the clients.” | “The study reflected proper methodology while incorporating our needs and interests. In the end, the researcher gave us a really good foundation to do some extra work internally. Something that was very helpful was a prior relationship. The researcher had knowledge about the challenges that we faced, like funding … the staff felt they shared ownership and the distance between researchers and us diminished.” |

| Expectations | “Often researchers approach us with the idea of collaboration, but they can’t offer us a benefit … what is the benefit to the agencies and to the services and to the clients? If there’s not a benefit, there’s not a relationship … and I will say that it really has been frustrating that there has been research that we’ve participated in, and, with few exceptions, people don’t even have the courtesy of giving us their final report.” | “The entire project didn’t cost us any money! Trust was already established … the involvement of staff, clients, and volunteers was easier. There was a lot of communication between the researcher and the agency. The health educators were invited to the University and it was a big deal … they discussed the project, revised consent forms and offered feedback on the protocols. At the end, there was a presentation of the findings for the agency.” |

Quantitative Phase

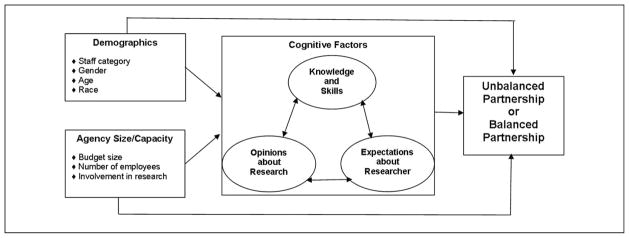

This phase was based on knowledge gleaned from in-depth interviews. Guided by our integrated theoretical framework, the extant literature, and interview data, we developed the structure of the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model, appearing here for the first time. Figure 1 summarizes key pathways to providers’ willingness to engage in two distinct research partnerships. It depicts associations between the outcome, intention to partner, and providers’ key demographics, and provider- and agency-level factors. “Unbalanced Partnership” denotes less distribution of tasks and procedures, and “Balanced Partnership” denotes more coordinated and balanced distribution. Both types of partnerships are treated as distinct outcomes in our model. We collected survey data to empirically validate the structure of partnership between researchers and front-line service providers, below.

Figure 1.

Provider–Researcher Partnership Model: Path diagram and conceptual associations.

Recruitment and Data Collection

For this phase, a total of 24 agencies were randomly selected among those funded by NYCDHMH. Executive directors (EDs) completed a 15- to 20-minute self-administered computer-assisted survey about their agencies. EDs received written details on study’s protocols, eligibility criteria, and compensation. They announced the study in meetings and posted recruitment flyers. We recruited 141 providers (4–12 per agency). Participants’ identities were not revealed to EDs. Each agency received $100 for providing space for interviews. Providers who volunteered for the study were interviewed by trained partnering providers. They received an Information Sheet outlining study requirements, risks, and content. Interviews lasted 45 to 75 minutes. Providers received $20 compensation. Password-protected mobile computers were used to administer and to download surveys into a password-protected database (DATSTAT Illume, 1997) used to design the survey and manage the data. All data were kept in password-secured computers to which only relevant personnel had access.

Measures

Drawing on qualitative findings and survey development procedures (Rea & Parker, 1997), we elaborated a multidimensional survey. Questions were developed in partnership with providers who gave feedback about language, clarity, and accuracy of questions. The agency survey, administered only to the Executive Director or other high-level administrator at each agency, comprised 35 questions about funding, services provided, and histories of involvement in research. The provider survey, administered to the full sample of 141 providers, comprised 157 questions capturing areas of interest, including factors hypothesized to influence providers’ preferences and intentions to partner. The provider survey also asked about attitudes, perceptions, and opinions about research, as well as specific experiences participating in research. Grounded in the concepts of balance and coordination and in-depth interview data, we created two vignettes, which were included within the provider survey, depicting contrasting coordination of research tasks and procedures. The provider survey was pilot tested with six providers whose input was used to refine questions and modify the order in which they were asked.

Outcomes

Vignettes are “short stories about hypothetical characters in specified circumstances, to whose situation the interviewee is invited to respond” (Finch, 1987; p. 105). We used vignettes to help participants focus on a specific aspect of their jobs thereby revealing key theoretical and empirical constructs found to influence providers’ intentions to partner, such as provider knowledge, opinions, and expectations (Hughes, 1998). Furthermore, the vignettes, based on providers’ perspectives, simulated situational differences that helped us examine diverse partnerships.

Respondents used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not inclined; 5 = very inclined) to assess how inclined they were to engage in the research characterized by each vignette. Though vignettes are labeled “Unbalanced Partnership” or “Balanced Partnership,” study participants were blind to these labels.

Unbalanced partnership denoted a distribution of responsibilities determined by the researcher limiting providers’ involvement to few tasks/procedures.

In this HIV prevention research project, the researcher has defined the main objectives, methods and procedures of the study, and will analyze, interpret, and disseminate the data collected via scientific journals and conferences. Agency providers would simply implement procedures—recruitment, interviewing, etc.

Balanced partnership denoted providers’ full involvement in the coordination and allocation of research tasks/procedures.

In this HIV research project, the researcher and agency providers together will define the main objective, methods, and procedures. They will together implement the study and analyze and interpret the data collected. They will—to the degree possible—jointly disseminate results via scientific journals and conferences. They will also jointly disseminate results via community-based publications and conferences.

Agency size and research capacity

We used four distinct measures of agency size/capacity. Agency budget was measured as small (less than half a million dollars) medium (half a million to a million dollars), and large (more than a million dollars). Number of employees was measured by a categorical variable: small (0–25 staff members), medium (26–100 members), and large (more than 100 members). Categories were based on natural breakpoints in the data. Agency involvement in research was measured in two ways: (a) number of years involved in research and (b) number of research projects involved over time.

Provider-level factors

Participants gauged their degree of agreement with survey statements using a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Items used to create composites, below, matched factors that were gleaned from in-depth interviews.

Providers’knowledge and skills were measured by two single items tapping providers’ training and involvement in research: one item represents the sum (range 0–18) of research tasks/procedures (e.g., recruiting participants, developing surveys) in which providers were trained. The other represents the sum (range 0–22) of tasks/procedures they had performed. Providers are routinely asked to implement EBPs. We thus included a four-item composite about EBP-related knowledge/skills. Statements (e.g., “I know how to match a DEBI to clients’ demographics and needs) were used to tap knowledge/skills about gold standard HIV prevention interventions—Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBIs; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). This composite was developed based on principal components factor analysis with geomin rotation and assessment of Cronbach’s alpha (.75). This composite in combination with the two single items above represent a cohesive domain measuring providers’ knowledge and skills, operationalized as measures of the latent factor knowledge/skills.

Opinions about research were measured by two composites, four items each. Both composites were developed based on principal components factor analysis with geomin rotation and alpha assessment. Opinions about ethics in scientific research (e.g., “Any information I give researchers can be used against clients”) had a .69 Cronbach alpha. Opinions about research benefits (e.g., “Disease prevention research benefits community”) had a .61 alpha. These alphas are considered “reasonably good” (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) given that this is the first study of its kind using newly developed measures. These composites represent cohesive domains measuring opinions about research operationalized as measures of the latent factor opinions about research.

Expectations about potential researcher/partner were measured by a three-item composite (e.g., “Partnership is most successful when the researcher is an expert”). This composite was developed based on principal components factor analysis with geomin rotation, Cronbach’s α = .60, also “reasonably good” for the same reasons specified above.

Demographics

Providers’ages were measured in years. Race and ethnicity included four categories: White, African American, Latinos/Latinas, and “others.”Gender was categorized as male or female. Education included high school, associates, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees. Education was coded as ordered categorical (1 = high school; 4 = master’s degree or higher). Job categories included supervising, counseling, educating, and program coordinating staffs.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarizing control variables were calculated. Mean scores for both vignette outcomes were compared across demographic subgroups using ANOVA F tests. Multiple pairwise comparisons were conducted using a Tukey adjustment to control for Type I error at 5%. Paired t tests were conducted within each demographic subgroup to test mean differences across the two vignettes (i.e., to test whether providers were more inclined to partner in the unbalanced as compared to the balanced vignette).

An SEM was fit following the form of Figure 1. In addition to being able to incorporate latent variables, another advantage of SEM over traditional regression techniques is the ability to model multiple outcomes simultaneously. The two vignette outcomes were modeled simultaneously and treated as ordered categorical. All predictors were treated as continuous although dummy variables were created where necessary (e.g., race). The structural residuals associated with the outcomes were allowed to correlate, as were all predictors. The mediating latent variables, knowledge/skills, opinions, and expectations were allowed to correlate with one another, but no specific directional paths were assumed among them.

There was a minimal amount of missing data that were handled using multiple imputations directly implementable in the software used, Mplus 6.1. Specifically, 10 multiply imputed data sets were generated and the effect estimates and fit statistics were averaged across all 10 sets of results while standard errors were appropriately adjusted to account for variability in the sample and in the imputation. Weighted least squares (WLSMV in Mplus) was used for estimation, as it correctly accounts for the ordered categorical measurement of the outcome variables. Percentage of variability explained in the two outcomes as well as variance explained in the latent mediators was used to assess predictive performance of the model. SEM fit statistics including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and comparative fit index were used to assess overall goodness of fit. Modification indices were examined to identify possible relationships that could be added to improve fit. This was done based on the first imputed dataset, because modification indices are not available averaged across all multiple imputations. Paths with modification indices larger than 10 and which were interpretable were added to the final model and their effects reported below.

Results

Community-Based Organization Characteristics

Approximately one half of the 24 community-based organizations (CBOs) in the sample represented agencies that mainly provided medical HIV-related services (e.g., HIV testing, medical care) and the other half provided mainly social services (e.g., counseling, HIV-prevention workshops). Seventeen agencies had budgets above $1 million; four between $500,000 and $1 million; and three below $1 million. One third employed more than 100 staff, one third between 26 and 100, and a third 25 or fewer. The number of staff per CBO ranged from fewer than 25 (in seven CBOs) to more than 100 (in eight CBOs). The number of volunteers per CBO ranged from fewer than 10 (in 11 CBOs) to 75 in one CBO. The number of research projects with which CBOs had been involved ranged from 1 to 10 (M = 4; SD = 3). Researchers with whom CBOs collaborated were academic faculty, medical doctors, or doctors of philosophy mainly in public health, social work, and psychology.

Provider Sample

The sample comprised 141 providers: 43 (31%) were supervisors of case managers, health educators, and counseling staff and who had practice experience as well. Forty (28%) represented counseling staff (e.g., social workers), 37 (26%) the educating staff (e.g., peer educators), and 21 (15%) the program coordinating staff (e.g., prevention program coordinators). Sixty-three percent of providers were women. The sample was diverse with 50 African American providers, 36 White, 33 Hispanic/Latino(a), and 22 “others”—2 American Indian/Alaskan Native; 7 Asian, South Asian, and Asian-Pacific Islanders; 7 Bi/Multi-racial; 1 Middle Eastern; and 5 “unknown.” The mean (M) age was 39 years (standard deviation [SD] = 13). Providers were employed 1 to 19 years (M = 2.5; SD = 3.4) by the same agency. Forty-nine providers had master’s degrees, 41 bachelor’s degrees, 20 associate’s degrees, and 31 high school diplomas. Ninety percent were previously involved in at least one research project. Tasks/procedures performed varied from recruitment to data collection to dissemination.

Average Providers’ Intentions to Partner by Demographics

Table 2 depicts average providers’ intentions to partner by their demographics. Intention was high for both vignettes—scores ranging from 1 (strong disinclined) to 5 (strong inclination). Regarding unbalanced partnership, the mean score for the sample was 3.45 (SD = 1.15). The mean score for the balanced partnerships was 3.93 (SD = 0.91). We detected a significant difference between these means (p < .001).

Table 2.

Demographics by Providers’ Intentions to Partner (N = 141).

| Unbalanced partnership, M (SD) | Balanced partnership, M (SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 141) | 3.45 (1.15) | 3.93 (0.91) | <.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Males (n = 52) | 3.385 (1.157) | 4.385 (0.718)c | <.001 |

| Females (n = 89) | 3.494 (1.149) | 3.989 (0.994)c | .004 |

| Age | |||

| Under 40 (n = 73) | 3.34 (1.11) | 4.14 (0.87) | <.001 |

| 40 or older (n = 68) | 3.57 (1.19) | 4.13 (0.99) | .005 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school (n = 31) | 4.032 (0.795)a,b | 4.032 (0.875) | .999 |

| High school (n = 20) | 3.800 (0.951) | 4.050 (0.826) | .349 |

| Associates/bachelor’s (n = 41) | 3.195 (1.229)a | 4.146 (1.014) | .009 |

| Master’s/doctorate (n = 49) | 3.163 (1.196)b | 4.225 (0.919) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (n = 36) | 3.333 (1.014) | 3.889 (1.063) | .039 |

| African American (n = 50) | 3.380 (1.227) | 4.300 (0.886) | <.001 |

| Latino(a) (n = 33) | 3.606 (1.197) | 4.121 (0.893) | .091 |

| Other (n = 22) | 3.591 (1.141) | 4.182 (0.733) | .020 |

| Job category | |||

| Supervising (n = 43) | 3.233 (1.109)a | 4.209 (0.965) | <.001 |

| Counseling (n = 40) | 3.359 (1.135) | 3.872 (0.923) | .051 |

| Educating (n = 37) | 3.489 (1.304) | 4.270 (0.962) | .004 |

| Program coordinating (n = 21) | 4.000 (0.837)a | 4.191 (0.680) | .446 |

Note.

Partnership scores ranged from 1 to 5: 1 = strong disinclination to partner and 5 = strong inclination.

Unbalanced Partnership = unbalanced distribution of tasks/procedures (Reverse coding was used).

Balanced Partnership = more coordinated and balanced distribution of research tasks/procedures.

Two-sample independent t test is statistically significant at p <.05.

Pairwise differences using a Tukey correction are statistically significant at p <.05.

p Value column is for paired t test of difference within person between responses to unbalanced and balanced partnerships for each demographic subgroup.

We found significant differences across vignettes, suggesting a preference for balanced partnership. Males and females have higher mean scores for balanced partnership. Providers with Associate/Bachelor and Master/Doctorate have higher scores for balanced partnership. Providers of all races/ethnicities also had higher scores. Of four job categories, supervising, counseling, and educating staffs had significantly higher scores than program coordinating staff.

Within partnership type, we found differences in terms of provider gender and education. Males had significant higher scores for balanced partnership (p < .05). Moreover, providers with less than high school education had higher scores for unbalanced partnership, compared with those with associate degrees or higher (p <. 05).

Structural Equation Analysis

Tables 3 and 4 show standardized estimated direct effects from the SEM. All estimated effects were mutually adjusted for all other effects and represent the independent effect of that variable on the respective outcome if all others were held constant.

Table 3.

SEM Estimated Path Coefficients to Providers’ Intentions to Partner (N = 141).

| Unbalanced partnership

|

Balanced partnership

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | β | p Value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Male versus female | −0.09 | 0.71 | 0.52* | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.79 |

| Education (1–4) | −0.23* | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.96 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American versus White | −0.15 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| Latino(a) versus White | 0.00 | 0.99 | −0.22 | 0.57 |

| “Other” versus White | −0.06 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.91 |

| Staff categories | ||||

| Supervising versus counseling | 0.13 | 0.67 | −0.01 | 0.98 |

| Educating versus counseling | 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.45 |

| Coordinating versus counseling | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.49 |

| Agency size and capacity | ||||

| Budget large versus small | 0.15 | 0.65 | −0.08 | 0.82 |

| Employees medium versus small | −0.26 | 0.51 | 1.03* | 0.02 |

| Employees large versus small | −0.28 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.21 |

| Research experience (years) | −0.06 | 0.75 | −0.47* | 0.00 |

| Number of research projects | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.70 |

| Provider factors | ||||

| Research opinions | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.30* | 0.04 |

| Expectation researcher | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.69 |

| Knowledge/skills | −0.20* | 0.05 | 0.22* | 0.02 |

| R2 | .19 | .48 | ||

Note. SEM = structural equation modeling.

p <.05.

Table 4.

SEM Estimated Path Coefficients to Provider-Level Factor (N = 141).

| Provider-level factors

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research opinions

|

Expectation about researcher

|

Knowledge and skills

|

||||

| β | p Value | β | p Value | β | p Value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male versus female | −0.40 | .10 | −0.19 | .37 | 0.17 | .37 |

| Age | 0.09 | .47 | 0.00 | .98 | −0.02 | .84 |

| Education (1–4) | 0.30* | .03 | 0.07 | .50 | 0.31* | .00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| African American versus White | −0.15 | .57 | −0.07 | .76 | −.21 | .43 |

| Latino(a) versus White | 0.40 | .22 | 0.23 | .41 | 0.14 | .62 |

| “Other” versus White | 0.15 | .61 | 0.44 | .19 | 0.06 | .87 |

| Staff categories | ||||||

| Supervising versus counseling | −0.10 | .71 | −0.12 | .63 | 0.19 | .49 |

| Educating versus counseling | 0.30 | .34 | 0.04 | .86 | 0.02 | .94 |

| Coordinating versus counseling | 0.31 | .36 | −0.18 | .56 | 0.02 | .95 |

| Agency size and capacity | ||||||

| Budget (large versus small) | 0.13 | .65 | −0.26 | .36 | 0.20 | .50 |

| Employees (medium versus small) | 0.47 | .18 | 0.59 | .10 | 0.72* | .05 |

| Employees (large versus small) | 0.75* | .05 | 0.81* | .01 | 0.53 | .09 |

| Research experience (years) | −0.25 | .14 | −0.11 | .49 | −0.33 | .06 |

| Number of research projects | 0.15 | .42 | −0.08 | .53 | 0.01 | .93 |

| R2 | .30 | .12 | .27 | |||

Note. SEM = structural equation modeling.

p <.05.

Modification indices suggested the inclusion of measurement error correlation between EBP-related knowledge/skills and opinions about research benefits (correlation = .44, p = .02). In addition, based on modification indices, a direct effect was included from race to the EBP-related knowledge/skills measure. Its effect (β= 0.36, p < .01) indicated African Americans were more likely to have higher EBP-related knowledge/skills than Whites. The goodness of fit indices for the final SEM included the following: chi-square = 88.5 with df = 53, comparative fit index = .88 and root mean square error of approximation = .07, indicating adequate model fit.

Predictors of Unbalanced Partnership

Table 3 shows a negative effect from education to unbalanced partnership (β= −0.23, p = .02). Among provider-level factors, providers’ knowledge/skills about EBPs (β= −0.20, p = .05) had a negative effect indicating as the knowledge/skills about EBP of the provider increased and all other predictors being equal, they were less likely to want to participate in an unbalanced partnership. These variables explained 19% of the variance in unbalanced partnership.

Predictors of Balanced Partnership

Table 3 shows that providers’ gender had a significant effect on balanced partnership (β= 0.52, p =.05), where males were more willing to partner. Among agency size/capacity variables, number of agency employees (medium vs. small; β= 1.03, p = .02) and agency research history (years involved in research; β= −0.47, p <.01) had, respectively, significant positive and negative effects on balanced partnership. Among provider-level factors, opinions about research (β= 0.30, p = .04) and knowledge/skills about EBP (β= 0.22, p = .02) both had positive effects on balanced partnership. These variables explained 48% of the variance in balanced partnership.

Predictors of Provider-Level Factors

Opinions about research

Table 4 shows that education had a positive effect on opinions about research (β= 0.30, p = .03). Number of employees (large vs. small) had a positive effect (β= 0.75, p = .05). Together these variables explained 30% of the variance in opinions about research.

Expectations about researchers

Table 4 shows that the only significant predictor of expectations about researchers was number of agency employees such that providers in larger agencies had more positive expectations (β= 0.81, p = .01) than providers in small agencies with fewer employees. In total, 12% of the variance in providers’ expectations about researchers was explained by this predictor.

Knowledge/skills

Table 4 shows that education (β= 0.31, p < .01) and number of agency employees (medium vs. small; β= 0.72, p = .05) had positive effects on knowledge/skills. Together these predictors explained 27% of the variance in knowledge/skills.

Estimated correlations between provider-level factors

Although no direct effect relationships among provider factors were hypothesized in the model, they were allowed to freely correlate controlling for demographic and agency factors. Providers’ expectations about researchers was correlated with opinions about research (correlation = .46, p =.02) and knowledge/skills (correlation = .24, p = .02). Providers’ opinions about research was positively correlated with knowledge/skills, but it did not reach statistical significance (correlation = .25, p <.06).

Discussion

This study was conducted to develop a theoretically and empirically based explanatory model of provider–researcher partnership. Partnership between front-line workers and researchers are crucial to bridge research to practice worldwide; nonetheless, providers’ perspectives on the structure of such partnerships are scarce in the literature. The Provider–Researcher Partnership Model is not an all-inclusive explanation of provider–researcher partnership. However, the model, grounded in data and theory, builds on previous knowledge and is useful to providers, researchers, and policy makers making decisions on implementation and funding of partnerships. Our model shows key pathways to providers’ intentions to partner based on two distinct vignettes. We acknowledge that these vignettes do not encompass all variables that may characterize partnership. Nonetheless, this model establishes important factors of provider–researcher partnership and respective key associations.

The model focuses on HIV prevention research, an area of interest that has relied on collaborative methods since the beginning of the epidemic. Therefore, our sample may have been savvier than non-HIV service providers about research partnership and may have had more exposure to researchers soliciting their opinions or advice. This study’s participants are unique in that they provide services related to a condition still attached to widespread stigma (e.g., sexual and drug behavior) and may thus experience high stress and burnout. These providers also face tensions around participating in practice versus research, as well as pressure to providing time-consuming evidence-based services. Nonetheless, HIV services providers offer myriad other services (e.g., substance abuse treatment, suicide, and incarceration prevention); therefore, our model can be used to gauge intentions to partner in different areas of research.

By establishing the Provider–Researcher Partnership Model, the present research makes unique contributions. First, we used data from a diverse sample of agencies and providers. Such diversity makes our model relevant to other contexts. The model also emphasizes the perspectives of individuals poised to use research in practice. Second, our partnering with providers improved the rigor of the methods we used and the relevance of our resulting model. Third, existing models for evaluating partnership overlook agency- and provider-level factors influencing intentions to partner (Khodyakov et al., 2011). These factors, key elements of our model’s structure, explained a large percentage of the variance in providers’ intentions to partner. Fourth, this study revealed modifiable factors and thus suggested areas of training that might help inspire providers to engage in research partnership, which, in turn, may improve evidence-based practice and patient outcomes (Bellamy et al., 2008; Franklin & Hopson, 2007).

Providers’ in-depth interviews generated two clearly different definitions of partnerships. We acknowledge that there may be partnerships whose distribution of research tasks/procedures may fall between unbalanced and balanced. However, this more nuanced characterization was not predominant in the interviews, possibly because providers were asked to describe contrasting partnerships. The qualitative data informed the model by providing the basis for the development of the vignettes describing two distinct partnerships as balanced versus unbalanced, as well as informing the development of the cross-sectional survey. Providers’ interviews offered insight into research tasks and procedures, which they performed, as well as their attitudes, expectations, and opinions about research collaboration. These insights richly informed the items on the cross-sectional surveys.

The SEM confirmed that providers were willing to partner in either partnership type, despite their gender, race/ethnicity, education, or staff category. However, the effect from identifying as African American to EBP knowledge skills suggests that although there might not be an overall effect of identifying as African American on the knowledge/skill overall latent factor, there was a unique effect relationship between identifying as African American and EBP knowledge, with African Americans having higher knowledge than Whites. Qualitative data suggested that providers are drawn to collaborative research and quantitative data that providers were more drawn to balanced distribution of research tasks/procedures. These findings confirm the extant literature (Ansari et al., 2001; Cargo et al., 2008), and thus suggests that policy makers ought to encourage researchers to engage providers by using providers’ preferred strategies.

Less formally, educated providers appear more willing to engage in unbalanced partnership. It may be because they lack confidence and/or feel intimidated to undertake research-related work and more eager to concede to researchers with more education/authority. Researchers are advised to pay attention to these providers and to resolve power-related issues that hamper any partnership (Gomez & Goldstein, 1996; Wallerstein, 1999). Moreover, program coordinators, who have more administrative job responsibilities, appear to be similarly drawn to either partnership type. This finding suggests that providers with more direct contact with consumers may prefer partnerships that allow them to perform research tasks, particularly those resembling practice, such as interviewing and facilitating interventions. By following the pathways explored in our model, researchers may have a better chance of developing partnerships where more egalitarian distributions of research tasks may inspire long-lasting partnerships with providers who have direct contact with clients/patients.

We used SEM to estimate path coefficients to providers’ intentions to partner. Regarding unbalanced partnership, we found no effect from providers’ job category. However, providers with less education were more drawn to partnerships where researchers, with more education and credentials, were characterized as responsible for all research tasks whereas providers were described as having an advisory role. Less knowledgeable/skilled providers were willing to engage in unbalanced partnership. The reason may be due to a lack of confidence in providers’ ability to perform research tasks/procedures. Qualitative data helped us better understand that providers with less education may more promptly acquiesce to researchers’ stipulations; nonetheless, these providers also want to be trained and encouraged to develop research knowledge/skills (Authors, 2009). This is an important finding for, as reported in the literature, research-involved providers are significantly more willing to use research in their practice (Chagnon et al., 2010; Owczarzak & Dickson-Gomez, 2011; Pinto et al., 2010).

Regarding balanced partnership, except for gender, we found no other demographic association. The literature shows that females are generally more interested in collaborative research (Etzkowitz, Kemelgor, & Uzzi, 2000; Hayes, 2001; Keashly, 1994; Pfirman, Collins, Lowes, & Michaels, 2005). Nonetheless, in our sample, males appear more eager to engage in balanced partnership. More research will be needed to identify specific factors that make males more inclined to engage in this type of partnership. One possible explanation is that female providers may experience imbalance of power where male providers may have more authority in their respective agencies. Males may thus feel more confident to demand more equality in the researcher–provider relationship.

We found significant effects from agency size/capacity on balanced partnership. Providers from larger agencies appear more willing to endorse balanced partnership. Larger agencies have more human, physical, and technological resources, all of which improve providers’ capacities to conduct research (Glisson, 2007; Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002). Having such capacity translates into providers having more training (Joe, Broome, Simpson, & Rowan-Szal, 2007) and ability to take on research tasks and procedures. This finding is bolstered by the significant effect found among provider-level factors. Both knowledge/skills and opinions had an effect on intention to partner. This suggests that more knowledgeable providers prefer more balance because they feel confident to participate fully. Moreover, in partnerships where providers have clearly defined roles, it is difficult for researchers to use providers’ agencies and then deny providers the results of research; an unwarranted occurrence widely reported in the literature (Israel et al., 2006; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008) and corroborated by our qualitative data.

Initially, somewhat surprisingly, providers in agencies with less research experience appear more willing to engage in balanced partnership. In-depth interviews suggested that before providers engaged in research, they did not know what to expect, but felt enthusiastic about partnering. As they became more experienced, they realized that research-related tasks further compounded feeling overburdened by other responsibilities (Galea et al., 2001; Krieger, 2001). Even though they still wished to partner, feeling overburdened made them less enthusiastic about engaging in research tasks/procedures.

We found significant effects from demographics and agency characteristics on provider-level factors. Providers with more education possess more knowledge/skills about research and stronger opinions about how research should be conducted. Providers in large agencies have clear expectations toward researchers and more knowledge/skills about research and EBPs. The larger the agency, the more capacity it will have to train providers (Gandelman, DeSantis, & Rietmeijer, 2006), who, in turn, will become more skilled/knowledgeable.

Limitations and Strengths

The Provider–Researcher Partnership Model comprises key factors that may influence providers’ intentions to partner in different research scenarios. Our model explained only partially the variance in unbalanced (19%) and balanced (48%) partnerships. Future research will be needed to examine other critical factors that may further explain intentions to partner. Studies using data from researchers are needed to corroborate and expand our findings. Also missing in the model are factors reflecting providers’ preferences for research topics, outcomes, and populations. Such preferences may have been revealed by probing providers to describe, in their in-depth interviews, other experiences involving more complex partnerships. Knowing that these preferences change over time, longitudinal studies will be ideal for expanding this model.

The Provider–Researcher Partnership Model may inadvertently suggest that all providers should be involved in research. This is not a realistic expectation because no agency has the capacity to involve its entire front-line staff in research at any given time. However, institutional theory points to the need to expose providers to a research culture that encourages involvement and inspire providers to practice from an evidence-based stance (Kelly, Sogolow, & Neumann, 2000). Since most providers are drawn to balanced partnerships, a culture of research that values this preference may be developed by helping providers, through training, enhance cognitive capacities (i.e., knowledge, skills, perceptions, and opinions) found to influence their intentions to partner. We also suggest that policy makers encourage a culture of research by providing researchers incentives for involving providers and by requiring, in turn, that researchers make available all findings to agencies, providers, and consumers.

We sought to use innovative methods and set the stage for future research. In-depth interviews were critical because providers’ narratives grounded survey development and corroborated quantitative findings. Providers gave narratives of two distinct partnership types used to develop vignettes that helped participants focus on specific aspects of research and reveal their perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes (Hughes, 1998). Qualitative data also revealed key factors that guided the SEM structure. SEM allowed us to test the mediating effects of critical agency- and provider-level factors overlooked in the literature. However, we acknowledge that our measures were new and had not been used in previous research. Future research will be needed for further validation of this study’s scales. Furthermore, we used some composites whose Cronbach alphas may seem low for predictive analysis. However, these alphas have been described as “reasonably good” (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) for first-time studies using newly developed measures. The composite EBP knowledge/skills had a better alpha and tapped an area of expertise that is considered gold standard HIV prevention interventions. The inclusion of this measure in our model is a new step in the direction of revealing the importance of EBP-related expertise toward providers’ intentions to partner.

Conclusion

Provider–researcher partnership is widely used in health research, but it is not yet fully understood. Given our promising findings and resulting Provider–Researcher Partnership Model, future studies may also benefit from CBPR and mixed methods approaches for studying research partnership. Qualitative data will help preserve the richness and depth of complex factors that influence providers’ decision making regarding their partnerships with researchers. Honoring providers’ voices is consistent with CBPR, which calls for researchers to prioritize provider-identified relevant issues. Qualitative data are ideal for capturing the meaning of providers’ priorities and interests and will be necessary in future studies to enhance the relevance of measures used to capture the complexity of providers’ partnering behavior. CBPR and mixed methods approaches will ensure that constructs being measured will reflect providers’ opinions and priorities so that findings can be applied in diverse contexts. SEM is recommended because it allows for the incorporation of latent variables and for the modeling of multiple outcomes simultaneously.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Pinto was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Mentored Research Development Award (K01MH081787).

Dr. Spector was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH19139, Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Principal Investigator: Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D.).

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH.

References

- Aarons GA. Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: Consideration of organizational context and individual differences. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:255–271. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A national agenda for research in collaborative care: Papers from the collaborative care research network research development conference. Rockville, MD: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari WE, Philips CJ, Hammick M. Collaboration partnerships: Developing the evidence base. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2001;9:215–227. doi: 10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbusch JL, Kirkham SR, Khan KB, McDonald H, Semeniuk P, Tan E, Anderson JM. Pursuing common agendas: A collaborative model for knowledge translation between research and practice in clinical settings. Research in Nursing and Health. 2008;31:130–140. doi: 10.1002/nur.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy J, Bledsoe SE, Mullen EJ, Fang L, Manuel J. Agency-university partnership for evidence-based practice in social work. Journal of Social Work Education. 2008;44(3):55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CE, Wickline MA, Ecoff L, Glaser D. Nursing practice, knowledge, attitudes and perceived barriers to evidence based practice at an academic medical center. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:371–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Delormier T, Levesque L, Horn-Miller K, McComber A, Macaulay AC. Can the democratic ideal of participatory research be achieved? An inside look at an academic-indigenous community partnership. Health Education Research. 2008;23:904–914. doi: 10.1093/her/cym077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carise D, Cornely W, Ozge G. A successful researcher-practitioner collaboration in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montaño J, Eng E. The power and the promise: Working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H, Garvin T, First Nation H-a-a. Modifying photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1393–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of HIV prevention interventions with evidence of effectiveness. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prevention_research_compendium.pdf.

- Chagnon F, Pouliot L, Malo C, Gervais MJ, Pigeon ME. Comparison of determinants of research knowledge utilization by practitioners and administrators in the field of child and family social services. Implementation Science. 2010;5:41. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne N, Lawson HA. An intervention framework for collaboration. Families in Society. 2005;86(1):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, Hamdallah M. The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: Development, implementation and lessons learned. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(Suppl A):5–20. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DATSTAT Illume. DATSTAT (data management software) Seattle, WA: Author; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Denis J, Lehoux P, Hivon M, Champagne F. Creating a new articulation between research and practice through policy? The views and experiences of researchers and practitioners. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;8(Suppl 2):44–50. doi: 10.1258/135581903322405162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook on qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edgren KK, Parker EA, Israel BA, Lewis TC, Salinas MA, Robinson TG, Hill YR. Community involvement in the conduct of a health education intervention and research project: Community action against asthma. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6:263–269. doi: 10.1177/1524839903260696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz H, Kemelgor C, Uzzi B. Athena unbound: The advancement of women in science and technology. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Finch J. The vignette technique in survey research. Sociology. 1987;21:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the Positive Youth Project. Health Education & Behavior. 2006;35:70–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin C, Hopson LM. Promoting and sustaining evidence-based practice: Facilitating the use of evidence based practice in community organizations. Journal of Social Work Education. 2007;43:377–404. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Factor S, Bonner S, Foley M, Freudenberg N, Latka M, Vlahov D. Collaboration among community members, local health services providers, and researchers in an urban research center in Harlem, New York. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:530–538. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandelman AA, DeSantis LM, Rietmeijer CA. Assessing community needs and agency capacity—An integral part of implementing effective evidence based interventions. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(Suppl A):32–43. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies P. Effectiveness of alliances and partnerships for health promotion. Health Promotion International. 1998;13:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C. Assessing and changing organizational culture and climate for effective services. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:736–747. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez CA, Goldstein E. The HIV prevention evaluation initiative: A model for collaborative and empowerment evaluation. In: Fetterman DM, Kaftarian SJ, Wandersman A, editors. Empowerment evaluation: Knowledge and tools for self-assessment and accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. Guidelines and categories for classifying participatory research projects in health. 2010 Retrieved from http://lgreen.net/guidelines.html.

- Harper GW, Carver LJ. “Out-of-the-Mainstream” youth as partners in collaborative research: Exploring the benefits and challenges. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26:250–265. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MJ, Cunliffe A. Organization theory: Modern, postmodern and symbolic perspectives. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes ER. New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education. Vol. 89. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. A new look at women’s learning; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R. Considering the vignette technique and its application to a study of drug injecting and HIV risk and safer behaviour. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1998;20:381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Krieger JW, Vlahov D, Ciske SJ, Foley M, Fortin P. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City, and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, Rowan-Szal GA. Counselor perceptions of organizational factors and innovations training experiences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A. Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist. 2008;63:146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keashly L. Gender and conflict: What can psychology research tell us? In: Taylor A, Miller JB, editors. Gender and conflict. Fairfax, VA: Hampton Press; 1994. pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg Foundation. Civic engagement. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.wkkf.org/what-we-support/civic-engagement.aspx.

- Kelly JA, Sogolow ED, Neumann MS. Future directions and emerging issues in technology transfer between HIV prevention researchers and community-based service providers. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(Suppl A):126–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, Ohito E, Jones A, Lizaola E. An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1:185–199. doi: 10.1177/2156869311431613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Research participation and turnover intention: An exploratory analysis of substance abuse counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger JW, Takaro TK, Song L, Weaver M. The Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project: A randomized, controlled trial of a community health worker intervention to decrease exposure to indoor asthma triggers. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:652–659. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: An ecosocial perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel BA, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:179–205. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layde PM, Christiansen AL, Peterson DJ, Guse CE, Maurana CA, Brandenburg T. A model to translate evidence-based interventions into community practice. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:617–624. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]