Abstract

The universal triggering event of eukaryotic chromosome segregation is cleavage of centromeric cohesin by separase. Prior to anaphase, most separase is kept inactive by association with securin. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) constitutes another binding partner of human separase, but the functional relevance of this interaction has remained enigmatic. We demonstrate that PP2A stabilizes separase-associated securin by dephosphorylation, while phosphorylation of free securin enhances its polyubiquitylation by the ubiquitin ligase APC/C and proteasomal degradation. Changing PP2A substrate phosphorylation sites to alanines slows degradation of free securin, delays separase activation, lengthens early anaphase, and results in anaphase bridges and DNA damage. In contrast, separase-associated securin is destabilized by introduction of phosphorylation-mimetic aspartates or extinction of separase-associated PP2A activity. G2- or prometaphase-arrested cells suffer from unscheduled activation of separase when endogenous securin is replaced by aspartate-mutant securin. Thus, PP2A-dependent stabilization of separase-associated securin prevents precocious activation of separase during checkpoint-mediated arrests with basal APC/C activity and increases the abruptness and fidelity of sister chromatid separation in anaphase.

Keywords: APC/C, PP2A, securin, separase, ubiquitylation

Introduction

In eukaryotes, other than in prokaryotes, the duplication and segregation of the genetic material are separated in time, taking place during S- and M-phase, respectively. This decoupling is made possible because the two sister chromatids of each chromosome are paired and thus treated as one unit beginning from the time of their generation in S-phase until their segregation in mitosis. Sister chromatid cohesion is mediated by the multi-protein complex cohesin. Its long coiled-coil subunits Smc1 and Smc3 together with the kleisin Scc1 (Rad21) form a tripartite ring, 50 nm in diameter, that provides a topological linkage by entrapping both DNA double strands (Haering et al, 2008). In early metazoan mitosis, cohesin rings at chromosome arms are removed by prophase pathway signaling which triggers the phosphorylation-dependent opening of the Smc3-Scc1 gate (Buheitel & Stemmann, 2013; Eichinger et al, 2013). However, sister chromatid cohesion is maintained because protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is recruited by shugoshin 1 (Sgo1) to centromeric cohesin and keeps it in a dephosphorylated state (Watanabe, 2005). At metaphase-to-anaphase transition, the Scc1 subunit of remaining cohesin is cleaved by separase and sister chromatids spring apart (Uhlmann et al, 2000). Separase is a large Cys-endopeptidase with a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain. It is encoded by an essential gene and represents the universal trigger of eukaryotic anaphase (Kumada et al, 2006; Wirth et al, 2006). Hyper- or hypo-activity of separase results in premature separation of sister chromatids or chromosome non-disjunction, respectively (Huang et al, 2005; Holland & Taylor, 2006; Boos et al, 2008). Separase also cleaves centrosomal cohesin and pericentrin-B (kendrin), which promotes centriole disengagement and licensing of subsequent centrosome duplication (Schockel et al, 2011; Lee & Rhee, 2012; Matsuo et al, 2012). The well-tuned regulation of separase activity is therefore crucial to ensure a stable inheritance of genomic information and to prevent aneuploidies that might otherwise result in cell death or malignant transformation.

Prior to anaphase onset, vertebrate separase is inhibited by mutually exclusive association with Cdk1-cyclin B1 or securin (Gorr et al, 2005; Stemmann et al, 2006). Cdk1-cyclin B1 is the master regulatory kinase of mitosis and phosphorylates a multitude of proteins. Its activation and inactivation, respectively, is necessary and sufficient for entry into and exit from mitosis. For unknown reasons, the relevance of Cdk1-cyclin B1 versus securin for the inhibition of separase varies in different cells and developmental states. For example, murine post-migratory primordial germ cells and early embryos chiefly rely on Cdk1-cyclin B1 to control separase, whereas in mouse female meiosis II and cultured human cancer cells, most of the protease is held in check by association with securin (Gorr et al, 2005; Huang et al, 2008, 2009; Nabti et al, 2008). Separase is activated at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition when both securin and cyclin B1 are degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The corresponding ubiquitin ligase is a multi-subunit RING E3, the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C), in conjunction with Cdc20, its mitosis specific co-activator (Peters, 2006). Cdc20 (but also Cdh1, a related co-activator of interphase APC/C) recognizes a motif of the minimal consensus sequence R-x-x-L, the so-called destruction box (or D-box), located close to the N-terminus of securin and cyclin B1. Securin (but not cyclin B1) contains an additional N-terminal motif called KEN-box, which is named after its core amino acid sequence and also binds to Cdc20 (and Cdh1). APC/CCdc20 activity is controlled by the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which, in metazoans, is of prime importance for timing of mitosis and chromosome segregation fidelity (Lara-Gonzalez et al, 2012). As long as chromosomes have not yet properly attached to spindle microtubules, this essential surveillance mechanism generates a diffusible ‘wait-anaphase’ signal at kinetochores, which inhibits APC/CCdc20.

Despite our knowledge of the basic SAC-APC/C-separase axis, other aspects of separase regulation remain poorly understood. For example, it has recently been noted that, relative to total securin, the separase-bound fraction is proteolysed more slowly (Shindo et al, 2012). However, both the putative function and the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon are unknown. Largely unresolved is also the question of why higher eukaryotic separase cleaves itself upon liberation from its inhibitors (Waizenegger et al, 2000; Herzig et al, 2002). In vitro this auto-cleavage does not influence the proteolytic activity or the re-inhibition of separase by securin or Cdk1-cyclin B1 (Stemmann et al, 2001; Waizenegger et al, 2002; Zou et al, 2002). Finally, PP2A was identified as another binding partner of human separase (Holland et al, 2007). The separase-PP2A complex seems to exist throughout most of the cell cycle and dissociates only transiently upon auto-cleavage of separase in anaphase until re-synthesis of full-length protease in the next G1 phase. Despite these initial characterizations, the in vivo relevance of the separase-PP2A complex formation remains again largely enigmatic. PP2A is a heterotrimeric serine/threonine phosphatase consisting of a scaffolding A subunit, a catalytic C subunit, and a variable regulatory B subunit that mediates subcellular targeting and substrate specificity (Janssens et al, 2005). Of the four subfamilies of B subunits that exist (B, B′, B″, and B‴), it is B′ (also called PR56) in all its isoforms which is found in association with separase (Holland et al, 2007).

Here, we show that PP2A restricts separase activity. It does so by dephosphorylation of separase-bound securin, thereby stabilizing it relative to the free, phosphorylated pool of securin. This function of PP2A not only prevents precocious activation of separase in cells that are arrested in G2- or prometaphase. It also ensures that virtually all excess securin is degraded before the separase-associated pool is targeted. In this way, PP2A prevents repeated activation and re-inhibition of separase and increases the overall abruptness and fidelity of anaphase.

Results

Separase-bound securin is a substrate for separase-associated PP2A

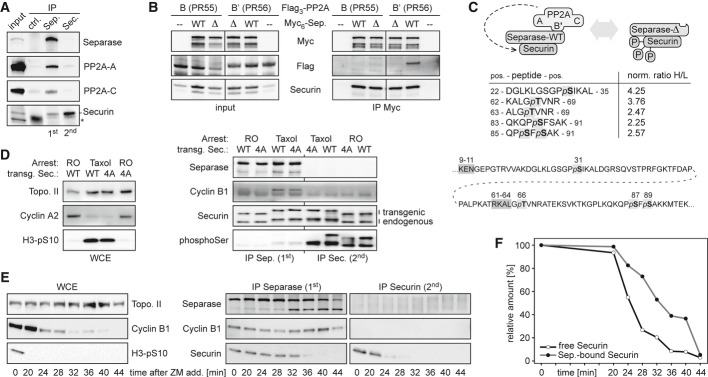

The B′ (PR56) regulatory subunit containing isoform of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) was previously identified as an interaction partner of human separase (Holland et al, 2007). It was also reported that the B (PR55) isoform of PP2A can directly interact with human securin (Gil-Bernabe et al, 2006). Therefore, it remained to be clarified whether PP2A interacts directly with separase, securin, or both, and which isoform of the phosphatase would do so. First, a separase antibody was used for immunoprecipitation (IP) of all separase-securin complexes from a lysate of mitotically arrested HeLa cells. Then, a securin antibody was used in a second step to isolate free securin from the separase-depleted supernatant. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated material revealed that the constitutive PP2A subunits A and C specifically co-purified with separase-securin complexes, but not with free securin (Fig1A). Similar IP-Western experiments from cells expressing Myc-separase and Flag-tagged versions of either PP2A-B or PP2A-B′ furthermore demonstrated that it is only the B′ (PR56) containing isoform of PP2A which interacts with separase (Fig1B).

Figure 1. The indirect association of separase-bound securin with PP2A-B′56 correlates with its hypophosphorylation and increased stability over free securin.

- PP2A associates with separase-securin complex, but not with free securin. Separase antibody was used to immunoprecipitate separase-securin from lysates (input) of mitotic HeLa cells overexpressing separase, securin, PP2A-A, and PP2A-C. Unspecific IgG served as control (ctrl.). Subsequently, free securin was isolated from the separase-depleted lysate using anti-securin. IPs were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated. *light chain of unspecific IgG.

- The B′- and not the B-isoform of PP2A interacts with separase-securin. Lysates (input) of mitotic HEK293T cells overexpressing Myc-tagged variants of wild-type (WT) separase or a PP2A-binding deficient deletion mutant (Δ) and Flag-tagged versions of either PP2A-B55 (α isoform) or PP2A-B′56 (δ isoform) were subjected to anti-Myc IP and immunoblotting.

- Rationale and summary of the SILAC-MS experiment to quantitatively compare the phosphorylation of securin bound to separase-WT or separase-Δ. The table shows the five phospho-peptides with the largest difference in phosphorylation state. The ratios of heavy (H; separase-Δ) and light (L; separase-WT) phospho-peptides were normalized (norm.) to those of unrelated, unphosphorylated peptide pairs. Shown below is the positioning of the mapped phosphorylation sites (bold letters, light gray shading) relative to the APC/C recognition sites (dark gray shading) within securin (amino acid positions given on top).

- Separase-less securin is hyper-phosphorylated. Transgenic HeLa cells were induced to express C-terminally Flag-tagged securin-WT or securin-4A and synchronized in prometa- or late G2-phase by taxol or RO3306 (RO). Whole cell extracts (WCE) and sequential IPs of separase and securin were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated (H3-pS10 = Ser-10 phosphorylated histone H3).

- Accelerated degradation of free over separase-bound securin. Pre-synchronized HeLa cells were released from a taxol arrest by addition of ZM447439 (ZM) and CHX at t = 0 min and harvested in aliquots at the indicated time points. Whole cell extracts and sequential IPs of separase and securin were analyzed by immunoblotting as indicated.

- Securin immunoblot signals were quantified relative to the band at t = 0 min. Shown are mean values of three independent experiments.

Within the complex of separase, securin, and PP2A, the phosphatase is catalytically active (Holland et al, 2007). This begs the question whether securin might be a direct target of separase-bound PP2A. To address this issue, we capitalized on a separase variant with a small internal deletion (Δ) that largely abrogates PP2A binding without affecting proteolytic activity in vitro nor association with securin or Cdk1-cyclin B1 (Holland et al, 2007). We used SILAC (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture) followed by mass spectrometry to quantitatively assess the phosphorylation status of securin associated with either wild-type (WT) or PP2A-binding deficient (Δ) separase affinity-purified from prometaphase-arrested HEK293T cells (Ong & Mann, 2007). This analysis revealed that Ser-31, Thr-66, Ser-87, and Ser-89 of human securin were 2.3- to 4.3-fold hyperphosphorylated when binding of PP2A to separase was compromised (Fig1C). (Somewhat unexpected, these changes did not coincide with upregulation of separase phosphorylations critical for binding of Cdk1-cyclin B1.) The observed differences in securin phosphorylation likely represent underestimations because the small deletion within separase-Δ greatly compromises, but does not fully abrogate its ability to recruit PP2A (Holland et al, 2007). Thus, securin is a substrate of separase-associated PP2A. Together with the inability of PP2A to bind securin directly (Fig1A), these findings further suggested that—relative to separase-bound securin—free securin should be in a hyperphosphorylated state.

To test this prediction and whether we had mapped major phosphorylation sites, we used site-specific recombination to generate stable HeLa lines that inducibly expressed either WT securin or a variant that had the Ser/Thr residues at positions 31, 66, 87, and 89 replaced by alanines (securin-4A). Both alleles were expressed to the same and near physiological level upon doxycycline (Dox) addition (Supplementary Fig S1A). C-terminal Flag-tags reduced the motility of the transgene-encoded securins in SDS–PAGE, thereby allowing the faster migrating endogenous securin to serve as an internal reference. Cultures of the two lines were pre-synchronized in G2 by the Cdk1 inhibitor RO3306 (RO) or in prometaphase by taxol and used for the consecutive IPs of first separase-bound and then free securin. Comparative Western analysis using an antibody specific for phosphorylated serine revealed (i) that free securin indeed exhibits a pronounced hyperphosphorylation relative to separase-associated securin in both G2- and prometaphase and (ii) that serine phosphorylation in securin-4A is greatly diminished in G2 and virtually undetectable in prometaphase (Fig1D). These results are consistent with the SILAC-MS analysis and confirm Ser-31, Ser-87, and/or Ser-89 as major phosphorylation sites of securin that are effectively dephosphorylated by separase-associated PP2A.

Free securin is degraded more rapidly than separase-bound securin

It has recently been reported that HeLa cells that are released from a prometaphase arrest exhibit delayed degradation kinetics of separase-associated relative to total securin (Shindo et al, 2012). Given that in prometaphase-arrested HeLa cells, free securin is 4- to 5-fold more abundant than separase-associated securin (Fig1A), the accelerated disappearance of total securin might largely be attributed to preferential proteolysis of free over separase-bound securin. To test this prediction, taxol-arrested HeLa cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to prevent re-synthesis of securin and with the aurora B kinase inhibitor ZM447439 (ZM) to synchronously drive them through an anaphase- into a G1-like state (Shindo et al, 2012). Confirming the success of the release, cyclin B1 and Ser10-phosphorylation of histone H3 both disappeared, and separase cleaved itself (Fig1E). As before, aliquots taken at different time points were used to purify separase-securin complexes and free securin by two consecutive rounds of IP. Quantitative immunoblotting confirmed the predicted faster degradation kinetics of free over separase-associated securin (Fig1E and F). As a result, about 75% of separase-bound securin still persists when 75% of free securin has already been cleared from the cell. An earlier disappearance of free relative to separase-bound securin is also observed in the absence of CHX albeit with slowed overall kinetics (unpublished observation).

Interestingly, free securin is less stable than separase-associated securin even in checkpoint-arrested cells. Upon CHX addition to nocodazole-treated HeLa cells, free securin started to decline after 2 h and was undetectable after 8 h (Supplementary Fig S2A). In contrast, separase-bound securin remained largely stable over 8 h in these SAC-arrested prometaphase cells and began to slowly disappear only after 10 h, probably as a consequence of apoptosis as judged by the increase in number of cells with sub-G1 DNA content. We also assessed the stability of the two securin pools during a DNA-damage checkpoint-mediated arrest in G2 phase. To this end, HeLa cells were arrested in early S-phase with thymidine, released for 6 h, and then treated with doxorubicin (DRB), which causes DNA double-strand breaks due to poisoning of topoisomerase II. The success of these synchronization procedures was confirmed by flow cytometry and immunoblotting (Supplementary Fig S3). Subsequent CHX shutoff experiments revealed that free securin was short-lived also during a G2 arrest, with a half-life of about 1 h, while separase-bound securin was stable for at least 5 h (Supplementary Fig S2B). Thus, irrespective of the very different degradation kinetics at different cell cycle phases, free securin is always less stable than separase-associated securin.

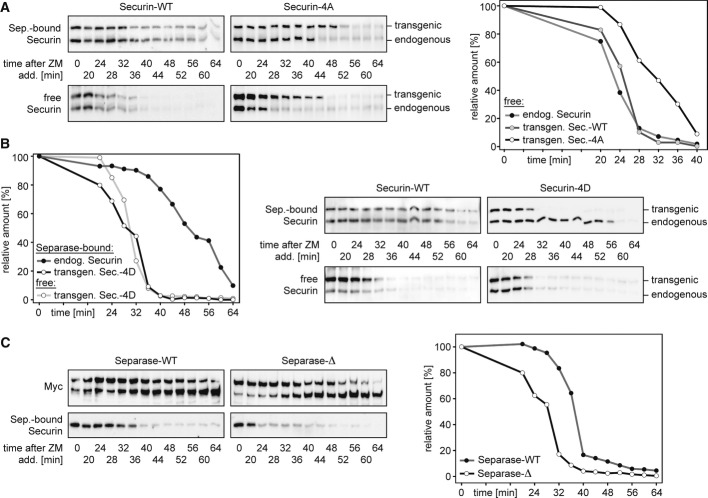

PP2A stabilizes separase-bound securin by dephosphorylation

Is the difference in stability between free and separase-bound securin due to a different phosphorylation status of both pools? If phosphorylation turns securin into a better substrate for the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), then preventing its phosphorylation by mutation should stabilize free securin. Vice versa, mimicking constitutive phosphorylation with a negatively charged amino acid might destabilize separase-bound securin, which is normally held in a dephosphorylated state by action of associated PP2A. To test these predictions, we generated also a HeLa line that inducibly expressed a (C-terminally Flag-tagged) securin variant with aspartates at positions 31, 66, 87, and 89 (securin-4D) but was otherwise isogenic with the aforementioned securin-WT and securin-4A lines (Supplementary Fig S1B). When prometaphase cells were released with ZM into CHX-containing medium, strikingly, the free pool of securin-4A exhibited greatly retarded degradation kinetics (Fig2A). Importantly, the behavior of securin-4D was the exact opposite. This phosphorylation-mimicking variant disappeared with WT kinetics in its free form but was greatly destabilized relative to endogenous securin in its separase-associated form (Fig2B). Of note, separase-associated securin-4A was detectable even longer than free securin-4A or separase-associated endogenous securin (Fig2A and Supplementary Fig S7B). This could be due to additional phosphorylation sites, which escaped our mapping analysis, but the fact that securin-4D is degraded with nearly the same kinetics in its separase-associated and free forms (Fig2B) argues against this possibility. Instead, we attribute this phenomenon to the association of lingering free securin-4A with separase that has already been stripped of endogenous securin (see Discussion). None of the above effects was caused by the tagging per se because transgene-encoded tagged securin-WT was degraded with kinetics identical to the endogenous protein (Fig2A and B).

Figure 2. Securin is destabilized by phosphorylation and stabilized by PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation on separase.

- Preventing its phosphorylation stabilizes free securin. Transgenic HeLa cells induced to express C-terminally Flag-tagged securin-WT or securin-4A were treated as described in Fig1E and subjected to sequential IPs that separated separase-bound securin (top panels) from free securin (bottom panels). The graph represents the mean degradation kinetics of endogenous and transgenic free securin. Western signals of three independent experiments were quantified by densitometry and blotted as percent of the value at ZM addition (t = 0).

- Mimicking its phosphorylation destabilizes separase-associated securin. Transgenic HeLa cells induced to express C-terminally Flag-tagged securin-WT or securin-4D were treated and analyzed as described in (A).

- Preventing PP2A binding to separase accelerates the degradation of associated securin. Mitotic HeLa cells induced to overexpress Myc-tagged separase-WT or separase-Δ were incubated with trace amounts of okadaic acid shortly before ZM addition to inactivate residual PP2A on separase-Δ but leave gross PP2A activity unaffected. Transgenic separases were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc, and associated endogenous securin was quantified as described in (A).

A securin variant which lacks its first 100 amino acids retains normal ability to bind and inhibit separase but can no longer be degraded. Given that the N-terminal half of securin contains not only the KEN- and D-box but also the identified PP2A substrate sites (Fig1C), it is conceivable that phosphorylation of the corresponding residues could impact securin's clearance via the UPS. At this point, it could not be excluded, however, that the changed degradation properties of securin-4A and securin-4D were caused not by blocked or mimicked phosphorylation but rather by the mutations per se. To rule out this possibility, we capitalized on separase-Δ with impaired PP2A binding ability. Securin in association with this separase variant should be phosphorylated and exhibit a reduced half-life if phosphorylation does indeed turn the anaphase inhibitor into a better UPS substrate. Transgenic HeLa cells were induced to express Myc-tagged separase-WT or separase-Δ, synchronized in prometaphase with taxol, and then released by ZM into medium containing CHX and trace amounts of okadaic acid (OAA) to inhibit residual PP2A still associated with separase-Δ. Time-resolved anti-Myc IPs followed by quantitative immunoblotting revealed that endogenous securin in complex with transgenic separase-WT and separase-Δ had mean half-lives of 38 and 29 min, respectively (Fig2C). This result is fully consistent with the behavior of the phosphorylation site mutant securins and validates the 4A and 4D variants as probes to study the effects of no or constitutive securin phosphorylation, respectively. In summary, the above experiments demonstrate that securin is destabilized by phosphorylation and stabilized by separase-based PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation.

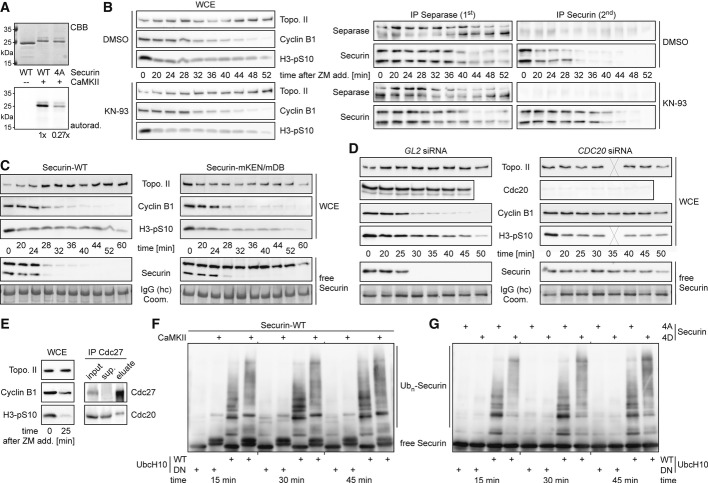

Phosphorylation of securin enhances its APC/C-dependent polyubiquitylation

What are the kinases that destabilize securin by phosphorylation? According to a scansite prediction (Obenauer et al, 2003), one candidate is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) which might target Ser-87 of human securin because this site ranks among the top 0.071% of putative CaMKII motifs across all vertebrate proteins (percentile 0.071). Indeed, recombinant CaMKII readily phosphorylated bacterially expressed, affinity-purified human securin-WT (Fig3A). The CaMKII-dependent labeling of securin-4A was 3.7-fold less efficient consistent with Ser-87 representing a chief phosphorylation site for this kinase. Next we asked whether chemical inhibition of CaMKII with KN-93 would impact the degradation kinetics of securin in vivo. To this end, securin-WT-expressing, taxol-arrested HeLa cells were treated with either KN-93 or its carrier solvent DMSO (control) for 4 h and then released into anaphase with ZM. Time-resolved immunoblotting demonstrated that the CaMKII inhibitor extended the half-life of free securin by about 15 min while leaving the overall exit from mitosis unaffected (Fig3B). KN-93 treatment had also no overt effect on the proteolysis of separase-bound securin, probably because this pool is constantly being dephosphorylated by PP2A.

Figure 3. Rapid degradation of free securin depends on CaMKII and APC/C.

- CaMKII phosphorylates securin at PP2A substrate site(s). Recombinant securin-WT or securin-4A was incubated with active (+) or heat-inactivated (−) CaMKII in presence of γ-33P-ATP and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, auto-radiography, and Coomassie staining (CBB).

- Inhibition of CaMKII decelerates the degradation of free securin in vivo. Transgenic HeLa cells were induced to express Flag-tagged securin-WT, arrested with taxol and then treated with the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 or DMSO 4 h prior to addition of ZM and CHX (t = 0 min). Aliquots harvested at the indicated time points were analyzed as described in Fig1E.

- Free securin is stabilized by mutation of its KEN- and D-box. Transgenic HeLa cell lines were induced to express Flag-tagged securin-WT or securin-mKEN/mDB, released from a taxol arrest by ZM (and CHX) at t = 0 min, harvested in aliquots at the indicated times and analyzed as in (B). Coomassie-stained IgG-heavy chain (hc) served as a loading control for the securin IP.

- Free securin is stabilized by Cdc20 depletion. HeLa cells transfected with siRNA against CDC20 or GL2 were otherwise treated and analyzed as described in (B). Note that the Cdc20 panels are directly comparable as the corresponding samples were run on one gel and blotted onto the same membrane. Crosses indicate lost samples.

- Affinity purification of APC/CCdc20. APC/CCdc20 was immunoprecipitated from taxol-ZM-treated HeLa cells with an antibody directed against the C-terminus of Cdc27 and competitively eluted with the antigenic peptide. Sup. = supernatant.

- Phosphorylation of securin with CaMKII enhances its APC/CCdc20-dependent polyubiquitylation. Bacterially expressed, purified human securin was pre-phosphorylated with CaMKII where indicated and then incubated for the indicated times in an ubiquitylation assay containing wild-type (WT) or dominant-negative (DN) UbcH10 and APC/CCdc20 [from (E)]. Reactions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and anti-securin Western. Ubn = ubiquitin chains.

- Increased processivity of multi-ubiquitylation of securin-4D versus securin-4A. An APC/CCdc20-dependent ubiquitylation assay was performed and analyzed as described in (F).

Securin is a well-established substrate of APC/C. Its KEN- and D-box are recognized by Cdc20 and Cdh1, APC/C's co-activators in mitosis and interphase, respectively. However, the pronounced phosphorylation dependence of securin degradation is reminiscent of proteolysis mediated by SCF-complexes, another class of multi-subunit ubiquitin ligases. In fact, the same study that reported the existence of a direct interaction between PP2A and securin also claimed that phosphorylated securin was degraded in an SCF-dependent manner (Gil-Bernabe et al, 2006). To clarify this issue, we asked whether mutational inactivation of the KEN- and D-box or depletion of Cdc20 by RNAi would affect the rapid degradation of free, phosphorylated securin in late mitosis. When securin with mutated KEN- and D-boxes (mKEN/mDB) was inducibly expressed in corresponding transgenic HeLa cells, this variant appeared to be fully stable during a ZM-mediated SAC override, that is, at a time when endogenous securin and transgenic securin-WT were rapidly degraded (Fig3C). Upon its addition to HeLa cells or Xenopus egg extracts, the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (OAA) induces a pseudo-anaphase state with active APC/CCdc20. While WT securin was rapidly degraded under these conditions, the mKEN/mDB variant was again not proteolysed but merely hyperphosphorylated leading to reduced and less uniform electrophoretic mobility that could be reversed by λ-PPase treatment (Fig S4). Furthermore, upon ZM addition to Cdc20-depleted, taxol-treated cells, separase-free securin did not decline over at least 45 min (Fig3D). In contrast, mock-depleted control cells fully degraded this securin population within 30 min. Securin-mKEN/mDB-expressing or Cdc20-less, taxol-arrested cultures were also supplemented with CHX alone, that is, without simultaneous addition of ZM. These experiments revealed that even the slow degradation of free securin during a prolonged prometaphase arrest required an intact KEN- and D-box as well as the presence of Cdc20 (Supplementary Fig S5A). Finally, we tested the requirements of securin proteolysis in DNA-damage checkpoint-arrested G2 cells. Consistent with APC/CCdh1 being the predominant form of active APC/C at this stage (Bassermann et al, 2008), securin degradation was hardly affected by depletion of Cdc20 (unpublished observation). However, securin was again strongly stabilized in DRB-treated cells by mutational inactivation of its KEN- and D-box (Supplementary Fig S5B). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that, irrespective of kinetic differences, the degradation of securin in G2-, prometa-, and anaphase is largely, if not entirely, dependent on APC/C.

To clarify whether the APC/C-catalyzed ubiquitylation reaction itself or a different step of the degradation pathway is positively influenced by securin phosphorylation, we immuno-affinity-purified the APC/C subunit Cdc27 (Apc3) from HeLa cells that were released from a taxol arrest by treatment with ZM for 25 min (Fig3E). Combining the resulting APC/CCdc20 preparation with ATP, ubiquitin, E1 (Ube1), and UbcH10 (Ube2C) led to ubiquitylation of bacterially expressed, purified securin (Fig3F). This reaction was specific as it was blocked by replacement of WT UbcH10 with a dominant-negative (DN) variant of this E2. Importantly, ubiquitin chain formation was enhanced if securin was pre-treated with CaMKII and ATP (Fig3F). Similarly, phosphorylation-mimicking securin-4D was subject to much more pronounced multi-ubiquitylation than phosphorylation site mutant securin-4A under otherwise identical conditions (Fig3G). Together, these reconstitution assays demonstrate that N-terminal phosphorylations indeed render human securin a better APC/C substrate, a notion that is fully consistent with the observed in vivo-degradation kinetics.

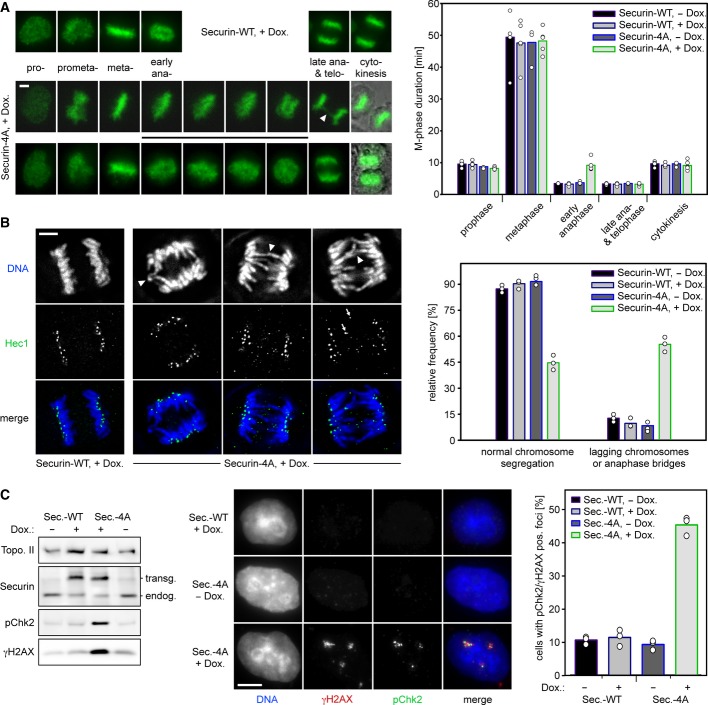

Phosphorylation site mutant securin compromises timing and fidelity of anaphase

Why are separase-bound and free, excessive securin degraded with such different kinetics? And does interference with this phosphorylation-dependent difference have any physiological consequences? To address these questions, we first asked whether expression of securin-4A resulted in any effect on the timing and fidelity of mitosis. Transgenic cells were transiently transfected to label their chromosomes with histone 2B-eGFP and then filmed by video fluorescence microscopy in the presence or absence of Dox (Fig4A). Subsequent quantification showed that induced expression of securin-4A (but not of securin-WT) caused an averaged lengthening of early anaphase from 3.4 to 9.2 min, while all other phases of mitosis were normal in timing. This specific effect was accompanied by the frequent occurrence of anaphase bridges. Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) of fixed cells confirmed that individual chromosome arms and/or Hec1-stained kinetochores lagged behind in more than 50% of securin-4A-expressing anaphase cells, while these defects were rarely observed (<13%) in the corresponding controls (Fig4B). Chromosome segregation defects are associated with an increase in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) which is due to lagging chromosomes being frequently damaged through cytokinesis and/or the formation of micronuclei (Janssen et al, 2011; Crasta et al, 2012). To clarify whether DSBs would also occur as an indirect consequence of blocked securin phosphorylation, transgenic securin-WT or securin-4A were expressed for 3 days or left uninduced before the corresponding cells were analyzed by immunoblotting and IF for DSB-specific phosphorylations of histone variant H2AX on Ser-139 (γH2AX) and checkpoint kinase 2 on Thr-68 (pChk2). Indeed, long-term expression of securin-4A caused a strong up-regulation of these DSB-markers (Fig4C). More specifically, γH2AX- and pChk2-positive nuclear foci were detected in 45% of securin-4A-expressing cells but only in about 10% of uninduced cells or those that expressed transgenic securin-WT. Thus, preventing securin phosphorylation at four key sites results in impaired chromosome segregation followed by DNA damage.

Figure 4. Phosphorylation site mutant securin compromises proper anaphase and elicits DNA damage.

- Expression of securin-4A (but not of securin-WT) prolongs the process of sister chromatid separation. Transgenic HeLa cells transiently transfected to express histone H2B-eGFP were released from a double-thymidine arrest and induced (+Dox) to express securin-WT or securin-4A or left uninduced. Live cell imaging was started 10 h later and conducted at 180-s intervals over a period of 12 h. Early anaphase was defined as the time between the first broadening of the metaphase plate until the first discernable separation of chromosomes into two masses. Arrowhead labels an anaphase bridge. Lower two panels on right represent merges of green fluorescence and DIC images. The graph shows mean values (bars) of four independent experiments (dots) quantifying at least 100 cells per line and state of induction. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Expression of securin-4A (but not of securin-WT) results in anaphase bridges. Cells were released from thymidine for 13 h, fixed, and stained for Hec1 and DNA. Impaired chromosome segregation was identified by lagging DNA (arrowheads) and/or lagging Hec1 signals (arrows) in anaphase cells. The graph shows mean values (bars) out of three independent experiments (dots). Between 250 and 600 cells were analyzed per line and state of induction. Scale bar, 5 μm.

- Long-term expression of securin-4A (but not of securin-WT) results in DNA-damage. Asynchronous HeLa cells induced to express securin-WT or securin-4A for 3 days were analyzed by immunoblotting and IF as indicated. Foci positive for γH2AX and phospho-Thr68 Chk2 (pChk2) were counted. Represented are mean values (bars) out of three independent experiments (dots) quantifying at least 200 cells per line and state of induction. Scale bar, 5 μm.

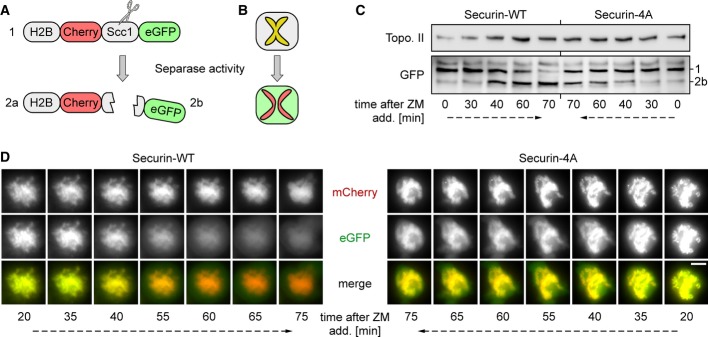

The above phenotypes could be explained by slowed or delayed activation of separase in presence of securin-4A. To test this directly, we adapted a recently published separase activity sensor (Shindo et al, 2012), which consists of a separase-cleavable Scc1 fragment fused N-terminally to histone 2B-mCherry and C-terminally to eGFP (Fig5A). The chromosomes of sensor-expressing cells fluoresce red and green (yellow in merge) early in mitosis but lose their green fluorescence when separase becomes active (Fig5B). We used transient transfection to express this sensor in our stable transgenic securin lines, arrested the cells in prometaphase with taxol, and then released them with ZM. Interestingly, the cleavage of the reporter was clearly delayed and less complete in securin-4A relative to securin-WT expressing cells as judged by time-resolved immunoblotting and live cell microscopy (Fig5C and D). Thus, physiological amounts of a securin variant which can no longer be phosphorylated dampen the otherwise switch-like activation of separase, thereby interfering with the abruptness and accuracy of sister chromatid separation in anaphase.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation site mutant securin impairs timely activation of separase.

A, B Structure (A) and cell-based read-out (B) of the separase activity sensor as adopted from (Shindo et al, 2012). The appearance of the eGFP containing cleavage fragment (2b) in an immunoblot (see (C)) is indicative of separase activity.

C, D Delayed separase activation in presence of phosphorylation site mutant securin. HeLa cells transiently expressing histone H2B-mCherry-Scc1107-268-eGFP were thymidine arrested, released into transgene inducing medium, and re-arrested by taxol. Upon addition of ZM, separase activity was followed by time-resolved immunoblotting analysis of whole cell extracts (C) and live cell fluorescence microscopy (D). Scale bar, 5 μm.

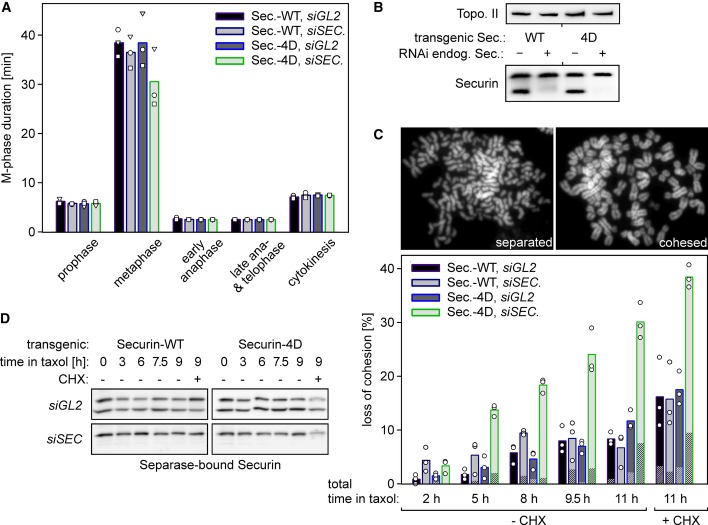

Mimicking constitutive securin phosphorylation results in premature activation of separase

Does selective destabilization of separase-associated securin by phosphorylation mimicking also have any cellular consequences? We performed video microscopy as before, which demonstrated that ectopic securin-4D expression by itself did not affect mitotic timing (Fig6A). Endogenous securin might suppress potential phenotypes by replacing precociously proteolysed securin-4D. Therefore, we combined knockdown of endogenous securin with induction of the (siRNA resistant) transgene (Fig6B). Consistent with separase-bound securin now being degraded as quickly as free securin (Fig2B), the replacement of endogenous securin by securin-4D resulted in a modest shortening of metaphase relative to the WT control (Fig6A). However, despite the slightly earlier advent of anaphase, cells segregated their chromosomes surprisingly normal (data not shown).

Figure 6. Mimicking constitutive phosphorylation of securin results in premature sister chromatid separation.

A Video fluorescence microscopy of histone 2B-eGFP-expressing cells reveals a slightly advanced onset of anaphase upon replacement of endogenous securin by securin-4D. Stable HeLa lines were transfected with siRNA against endogenous SECURIN or GL2 12 h prior to a thymidine block. Following release, cells were transfected to express histone H2B-eGFP and re-arrested with thymidine. Live cell imaging was started 10 h after release from the second block and induction of securin-WT or securin-4D expression. Images were taken in 180-s intervals over a period of 12 h. Shown are mean values (bars) of three independent experiments (dots, triangles, squares) quantifying at least 100 cells per line and siRNA.

B Efficient replacement of endogenous securin by (siRNA resistant) transgenic variants as judged by immunoblotting analysis. Cells from (A) were analyzed by immunoblotting 10 h after the second release.

C, D Replacing endogenous securin by securin-4D causes sister chromatid separation in prometaphase-arrested cells (C) without a detectable drop in separase-associated securin levels (D). Cells transfected with siRNA against SECURIN or GL2 were released from a thymidine block and induced to express securin-WT or securin-4D expression. 10 h after release and 2 h after addition of taxol, mitotic cells were harvested by shake-off, put in fresh medium with taxol, caspase 1/3 inhibitor and, where indicated, CHX and analyzed by chromosome spreads (C) and immunoprecipitation of separase-bound securin (D) at the indicated times. Shown are mean values (bars) of three independent experiments (dots) quantifying at least 100 cells per line and siRNA. Loss of cohesion was categorized as ‘full’ (striation) or ‘partial’, respectively, depending on full separation of all or only some (but at least 3) chromosomes within a given spread.

Each time a separase-associated securin molecule is degraded, the corresponding separase molecule will briefly become active before being re-inhibited by excessive, free securin. Given that the securin-4D variant has a higher turn-over rate on separase than WT securin, unscheduled cohesin cleavage is expected to be enhanced in cells expressing the former as compared to the latter. To test whether this might cause problems over time, we assessed how well sister chromatid cohesion was maintained in a prometaphase arrest. Replacement of endogenous securin by securin-4D indeed caused partial or complete loss of cohesion in 14% of the cells after 3 h in taxol and in 30% after 9 h (Fig6C). At these time points, control cells, in which endogenous securin was either replaced by transgenic securin-WT or left undepleted, displayed on average merely 4 and 8% premature sister chromatid separation, respectively. While precocious loss of cohesion was further enhanced by simultaneous CHX treatment, importantly, it did not essentially require inhibition of translation and even occurred without visible decline of securin-4D (Fig6C and D). Thus, the PP2A-dependent stabilization of the separase-securin complex is crucial to prevent transient activation of the cohesin-cleaving protease in SAC-arrested cells.

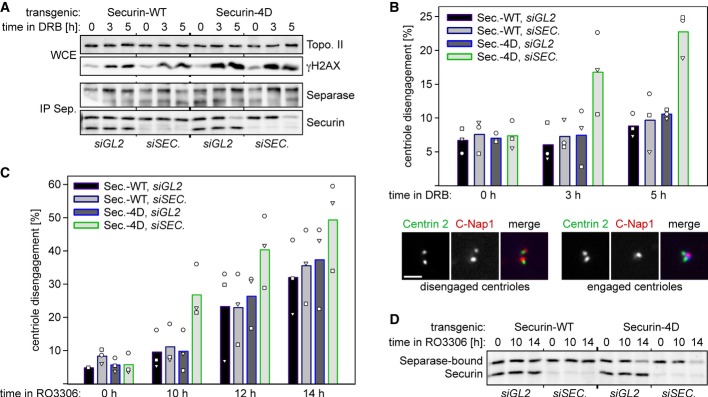

Finally, we asked whether replacing endogenous securin by securin-4D might also cause problems in cells that are arrested in G2 phase. Because separase is excluded from the nucleus (Sun et al, 2006), cleavage of chromosomal cohesin cannot serve as an indicator of separase activity in these interphasic cells. However, separase not only triggers sister chromatid separation in anaphase but also centriole disengagement in late mitosis/early G1 (Tsou & Stearns, 2006; Schockel et al, 2011). Indeed, cells arrested by DRB or RO undergo unscheduled centriole disengagement in an APC/C- and separase-dependent manner (Prosser et al, 2012). Synchronization by consecutive treatments with thymidine and DRB or RO were combined with transfection of siRNA against endogenous securin (or GL2 as a control) and induction of transgenic securin-WT or securin-4D (Fig7A and D, Supplementary Fig S1B). After different times in DRB or RO, cells were harvested and centriole engagement status was quantified by immunofluorescence microscopy of isolated centrosomes stained for the markers centrin-2 (distal) and C-Nap1 (proximal). These analyses not only confirmed the recent findings by the Fry and Morrison laboratories (Prosser et al, 2012) but also revealed that substitution of WT securin by the 4D variant aggravates the premature centriole disengagement phenotype. Specifically, cells which expressed securin-4D but lacked the endogenous anaphase inhibitor suffered from 22% centriole disengagement after 5 h in DRB, while the corresponding WT control displayed only 10% disengagement (Fig7B). Similarly, after 10 h in RO, cells that lacked endogenous securin exhibited 27% versus 11% centriole disengagement, respectively, if they expressed transgenic securin-4D instead of securin-WT (Fig7C). Despite the omission of CHX in these experiments, securin-4D (but not securin-WT) visibly dropped in abundance once cells were incubated for 5 h in DRB or 14 h in RO (Fig7A and D). However, the pronounced centriole disengagement in securin-4D-expressing cells lacking endogenous securin became apparent earlier, that is, prior to a detectable drop of securin-4D levels, which is consistent with the observation made on prometaphase-arrested cells (Fig6D). We conclude that elevating the turnover of separase-associated securin by mimicking its constitutive phosphorylation is associated with premature activation of separase and cellular defects during checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrests.

Figure 7. Mimicking constitutive phosphorylation of securin results in premature activation of separase in G2-arrested cells.

- Separase-bound securin-4D suffers from decreased stability in doxorubicin-treated cells. Transgenic HeLa cells transfected with siRNA against endogenous SECURIN or GL2 and synchronized with thymidine were released and induced to express securin-WT or securin-4D. 8 h thereafter, doxorubicin (DRB) was added to induce DNA damage and G2 arrest (in the absence of CHX). At indicated times, whole cell extracts (WCE) and corresponding separase IPs were immunoblotted as indicated.

- Replacing endogenous securin by securin-4D causes premature centriole disengagement during a DNA-damage checkpoint-mediated G2 arrest. WCE from (A) additionally served as starting material for centrosome purification followed by co-staining of centrin-2 and C-Nap1 and IF. Depending on a centrin-2 to C-Nap1 signal ratio of 2:1 or 2:2, centrioles were classified as engaged or disengaged, respectively. In three independent experiments (dots, triangles, squares), the engagement status of at least 100 centrosomes per cell line and condition was analyzed and blotted as mean value (bars). Scale bar, 0.5 μm.

- Replacing endogenous securin by securin-4D aggravates premature centriole disengagement in RO3306-treated cells. Transgenic HeLa cells were essentially treated as described in (A) except that instead of DRB RO3306 was added 4 h after removal of thymidine. Centriole engagement status was assessed as described in (B). Bars represent mean values of three independent experiments quantifying at least 100 centrosomes per cell line, siRNA and time point.

- Degradation of separase-bound securin-4D, but not securin-WT, in G2 arrested cells. Whole cell extracts (WCE) from (C) were subjected to separase IPs and immunoblotting.

Discussion

Here, we report that separase-associated securin is longer-lived than free securin, a finding that is consistent with a recent study by Hirota and co-workers (Shindo et al, 2012). We expand these findings and provide evidence that differences in phosphorylation status form the basis for this difference in stability. Phosphorylation, which may in part be inflicted by CaMKII, turns free securin into a better UPS substrate. In contrast, the B′56 isoform of PP2A keeps separase-associated securin in a dephosphorylated state, thereby selectively stabilizing this protease-bound pool of the anaphase inhibitor.

Separase-bound securin exhibits a greater half-life than free securin even in G2-arrested cells, in which Cdk1-cyclin B1 activity is low. Furthermore, the four phosphorylation sites mapped herein are not followed by a proline on the +1 position and hence do not match the consensus sequence of Cdk1 substrates. Both notions suggest that securin is phosphorylated on degradation-promoting positions not by Cdk1 but rather by other kinases. CaMKII might represent one such kinase. In vitro it efficiently phosphorylates securin-WT (but not securin-4A) and enhances the APC/CCdc20-dependent multi-ubiquitylation of this anaphase inhibitor. In vivo CaMKII might accelerate the destruction of free securin. Given that Ser-87, but not the other three identified phosphorylation sites match the consensus sequence of CaMKII substrates, it appears likely that additional kinases (and possibly a different set in G2 than in mitosis) contribute to the modulation of securin's overall stability. Based on a scansite analysis (Obenauer et al, 2003), it might be worth testing whether protein kinase C delta can target Thr-66 of securin (percentile 0.521). Securin is poorly conserved in sequence and exhibits, for example, merely 38% identity (10% gaps) between Homo sapiens and Xenopus laevis. The divergence within the structurally disordered N-terminal half is even higher and includes most phosphorylation sites. This raises the question whether the preferential destruction of phosphorylated securin is conserved. Beginning to address this issue, we studied the degradation kinetics of human securin-4A and securin-4D in Xenopus egg extract and found the phosphorylation-mimetic variant to be less stable—similar to the situation in human cells (Supplementary Fig S6). Thus, the ubiquitin-proteasome system of the frog interprets the additional negative charges within the N-terminal half of human securin just like its human counterpart. This observation argues that the more rapid degradation of phosphorylated versus dephosphorylated securin might indeed be conserved among vertebrates.

Preferred degradation of phosphorylated substrates is usually a hallmark of SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. In fact, it has even been reported that UV irradiation results in SCFβTrCP-dependent degradation of securin which requires the binding of the F-box protein βTrCP to an unconventional recognition motif (DDAYPE) centered around position 110 of human securin (Limon-Mortes et al, 2008). However, for the proteolysis of phosphorylated securin under the conditions tested herein, the APC/C remains the crucial E3. This is strongly suggested by the following lines of evidence: (i) When OAA is used to force Xenopus egg extracts or HeLa cells into a pseudo-anaphase state, WT securin is readily degraded. APC/C's recognition sites within securin, the KEN- and D-box, can be inactivated by point mutations that do not affect any phosphorylation sites, the OAA-induced hyperphosphorylation of securin, or the integrity of the aforementioned DDAYPE motif. Yet, this exchange of 5 amino acids renders securin completely stable in the presence of OAA. (ii) The same securin-mKEN/mDB is also fully resistant to degradation during a ZM-induced release of pre-synchronized metaphase cells into anaphase, a taxol-induced prometaphase arrest, or a DNA-damage-induced G2 arrest. (iii) siRNA-mediated depletion of Cdc20, the essential co-activator of mitotic APC/C, greatly stabilized securin in prometa- and anaphase cells. (iv) APC/CCdc20-dependent polyubiquitylation of securin is strongly boosted by both CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation and introduction of phosphorylation-mimetic acidic residues. Thus, while we did not address and therefore cannot exclude a minor contribution of SCFβTrCP to securin degradation, our analyses clearly underline that the preferred proteolysis of phosphorylated securin is largely, if not entirely, dependent on APC/C. Our findings are consistent with those of Clarke and co-workers who reported that the efficient APC/C-dependent clearance of Mcl-1 from mitotically arrested cells likewise requires prior phosphorylation of this anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member (Harley et al, 2010).

How can the effects in the in vitro ubiquitylation assay be explained at the mechanistic level? Phosphorylation of securin might increase its affinity toward the APC/C, thereby increasing the processivity of ubiquitin chain formation and, thus, the kinetics of degradation (Rape et al, 2006). Cdc20 and Cdh1 share a WD40 domain that folds into a structurally conserved seven-bladed β-propeller and specifically binds the KEN and D-Box. A recent crystal structure of S. cerevisiae Cdh1 in complex with a pseudo-substrate revealed that a conserved basic residue within the WD40 domain faces position +6 (P6) of the D-box (with the Arg of RxxL representing P1), which nicely explains why in APC/C substrates an acidic amino acid is most commonly found at this position (He et al, 2013). Interestingly, P6 of human securin's D-box corresponds to Thr-66. Phosphorylation at this position might therefore stabilize the interaction by giving rise to a salt bridge with the juxtaposed basic residue of APC/C's co-activator. Alternatively or in addition, the enhanced processivity of chain formation might be due to phosphorylation of securin accelerating the frequently rate-limiting initiation of ubiquitylation (Williamson et al, 2011). Interestingly, Ser-87 and Ser-89 lie within the so-called initiation motif of securin that is targeted by UbcH10 (Williamson et al, 2011). Given that initiation efficiency can control the timing of substrate degradation, it is tempting to speculate that phosphorylation of these residues improves the strength of securin's initiation motif. Future experiments will have to clarify whether phosphorylation increases the securin-APC/C affinity or the rate of ubiquitylation initiation or both, and they will have to dissect the relative contributions of the individual phosphorylations at the four different positions within securin's N-terminal half.

As illustrated by the effects of securin-4A expression, abolishing the preferential degradation of free securin dampens the otherwise fitful anaphase and results in aggravated lagging of chromosomes followed by DNA damage. How can these phenotypes be rationalized? If APC/C activity is limiting, then the extended lingering of free securin will competitively delay the degradation of separase-bound securin (Supplementary Fig S7A). Alternatively or in addition to this, surplus securin will re-inhibit any separase which has just been freed, thereby increasing the effective size of the separase-associated pool (Supplementary Fig S7A, gray arrow). Consistent with this second mode of action, the share of securin-4A in the separase-bound securin pool transiently increases after APC/C activation and prior to its complete extinction (Supplementary Fig S7B). Both competitive inhibition of APC/C and re-inhibition of separase are largely prevented by the actual removal of free securin prior to degradation of the separase-bound fraction, thus resulting in a more synchronized, switch-like activation of separase that likely improves the overall fidelity of sister chromatid separation. Another circumstance might add to the abruptness of anaphase onset: Once released from its inhibitor(s), separase immediately undergoes auto-cleavage which abrogates PP2A binding (Supplementary Fig S8A) (Holland et al, 2007). Therefore, any persisting free securin that sequesters previously activated separase is expected to stay phosphorylated and, thus, subject to accelerated degradation (Supplementary Fig S8B). It is therefore tempting to speculate that one function of auto-cleavage might be to minimize re-inhibition of separase at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition by traces of free securin that have so far evaded destruction. Interestingly, the sharpness of the metaphase-to-anaphase transition in S. cerevisiae is also modulated by a phosphorylation-dependent change of securin degradation kinetics. Curiously however, proteolysis of the budding yeast securin is slowed by its (in this case Cdk1-dependent) phosphorylation and sped up by dephosphorylation which occurs only upon activation of Cdc14 phosphatase in early anaphase (Holt et al, 2008). Thus, although the involved kinases, phosphatases, and mechanisms differ, the fine-tuning of late mitotic events by the impact of securin phosphorylation on its APC/C-dependent degradation kinetics is conserved from yeast to man.

At first sight, the expression of securin in excess of separase and the dephosphorylation-dependent stabilization of separase-associated securin seem inconsistent with a sharp metaphase-to-anaphase transition. As outlined above, these characteristics would indeed spoil the anaphase switch if it was not for the preferential degradation of free securin. So why does the cell afford these measures to begin with? Our in vivo analyses suggest that preventing unscheduled basal activation of separase during checkpoint-mediated arrests is the answer to this question. This can be illustrated by the exchange of endogenous securin with securin-4D, which exhibits an increased turnover even at times of low APC/C activity. This property of the phosphorylation-mimicking variant suffices to cause premature centriole disengagement and precocious sister separation, respectively, in G2- and prometaphase-arrested cells.

Why PP2A teams up with separase has long remained enigmatic. Our observations now strongly suggest that this interaction constitutes an additional layer of separase regulation that operates through securin and helps to fine-tune the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. Its main purpose, however, is to prevent the unscheduled unleashing of separase's essential but dangerous proteolytic activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

For inducible expression of securin-His6-Flag-His6-Flag (WT: wild-type; mKEN/mDB: K9R/E10D/N11Q and R61A/L64A; 4A: S31A/T66A/S87A/S89A; 4D: S31D/T66D/S87D/S89D) or Myc6-separase (WT: wild-type; ΔPP2A: Δ1490-93 for Fig1B and Δ1408-1478 for SILAC-MS experiment and Fig2C), corresponding transgenes were stably integrated into a HeLa FlpIn TRex cell line. Clones were selected with 400 μg/ml hygromycin B (PAA). All cells were cultured in DMEM (PAA) supplemented with 10% FCS (PAA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Growth medium for the transgenic lines was additionally supplemented with 4 μg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen) and 62.5 μg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation

1 × 107 cells were lysed in 1 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.7, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). To preserve securin phosphorylation status, lysis buffer was additionally supplemented with 1 μM okadaic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μM microcystin LR (Alexis Biochemicals). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 30 min. For separase and securin IPs, 10 μl protein G Sepharose was coupled to 2–5 μg of specific antibody for 90 min at room temperature. Coupled beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and incubated with cleared whole cell extracts (WCE) for 4 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, and bound proteins were eluted by boiling in reducing SDS-sample buffer. Note that in several experiments, separase-depleted lysates were subjected to another round of IP with immobilized anti-securin. For anti-Myc and anti-Flag IPs, the corresponding agarose matrices were equilibrated in lysis buffer, incubated with cleared WCE for 4 h at 4°C, and washed three times with lysis buffer before bound proteins were eluted by boiling in non-reducing SDS-sample buffer. For APC/C purification, pre-synchronized HeLa cells were arrested in taxol, harvested by shake-off, and released for 25 min by addition of ZM. Cell lysis and anti-Cdc27 immunoprecipitation were performed as described (Herzog & Peters, 2005) with the following exceptions: The high salt wash of immobilized APC/C was omitted, and the elution was performed in presence of 2 mg/ml antigenic Cdc27 peptide.

In vitro ubiquitylation assay

In vitro ubiquitylation reactions were performed largely as described (Herzog & Peters, 2005). Immuno-affinity-purified APC/CCdc20 (21 μl corresponding to half of the cell harvest from one 15-cm petri dish) was combined with 80 μg/ml E1 (Boston-Biochem), 50 μg/ml recombinant UbcH10-WT or UbcH10-DN (C114S), 1.25 mg/ml ubiquitin (Sigma-Aldrich), energy mix (1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 7.5 mM creatine phosphate, 30 U/ml creatine phosphokinase type I; Sigma-Aldrich), and 4.5 μg recombinant securin-WT, securin-4A, or securin-4D in a total reaction volume of 42 μl and incubated at 37°C. After 15–45 min, 7-μl reaction aliquots were subjected to SDS–PAGE and anti-securin Western. CaMKII pre-phosphorylation of securin-WT was performed in presence of 400 μM ATP in a total reaction volume of 5 μl.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Thomas U. Mayer for the HeLa FlpIn TRex cell line and anti-Cdc27; Silke Hauf, Stefan Heidmann, and Klaus Ersfeld for critical reading of the manuscript; Bernd Mayer, Michael Orth, and Martin Wühr for stimulating discussions; and all members of the Stemmann laboratory for help and input. This work was supported by grants (STE 997/3-2 within the priority program SPP1384 and STE 997/4-1) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to O.S.

Author contributions

FB initiated the project, generated all stable transgenic cell lines, performed the SILAC and the experiments shown in Fig1A and B, Supplementary Fig S4, and contributed to writing of the manuscript; SH co-designed and performed all experiments (including corresponding quantifications) except for the ones shown in Fig1A and B, Supplementary Fig S4, and contributed to writing of the manuscript; CP and MM performed the MS analysis; OS conceived and designed the research, made the figures, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information for this article is available online: http://emboj.embopress.org

References

- Bassermann F, Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Busino L, Peschiaroli A, Pagano M. The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell. 2008;134:256–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos D, Kuffer C, Lenobel R, Korner R, Stemmann O. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of cyclin B1 to a Cdc6-like domain of human separase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:816–823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buheitel J, Stemmann O. Prophase pathway-dependent removal of cohesin from human chromosomes requires opening of the Smc3-Scc1 gate. EMBO J. 2013;32:666–676. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasta K, Ganem NJ, Dagher R, Lantermann AB, Ivanova EV, Pan Y, Nezi L, Protopopov A, Chowdhury D, Pellman D. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 2012;482:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger CS, Kurze A, Oliveira RA, Nasmyth K. Disengaging the Smc3/kleisin interface releases cohesin from Drosophila chromosomes during interphase and mitosis. EMBO J. 2013;32:656–665. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Bernabe AM, Romero F, Limon-Mortes MC, Tortolero M. Protein phosphatase 2A stabilizes human securin, whose phosphorylated forms are degraded via the SCF ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4017–4027. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01904-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorr IH, Boos D, Stemmann O. Mutual inhibition of separase and Cdk1 by two-step complex formation. Mol Cell. 2005;19:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haering CH, Farcas AM, Arumugam P, Metson J, Nasmyth K. The cohesin ring concatenates sister DNA molecules. Nature. 2008;454:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nature07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley ME, Allan LA, Sanderson HS, Clarke PR. Phosphorylation of Mcl-1 by CDK1-cyclin B1 initiates its Cdc20-dependent destruction during mitotic arrest. EMBO J. 2010;29:2407–2420. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Chao WC, Zhang Z, Yang J, Cronin N, Barford D. Insights into degron recognition by APC/C coactivators from the structure of an Acm1-Cdh1 complex. Mol Cell. 2013;50:649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig A, Lehner CF, Heidmann S. Proteolytic cleavage of the THR subunit during anaphase limits Drosophila separase function. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2443–2454. doi: 10.1101/gad.242202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog F, Peters JM. Large-scale purification of the vertebrate anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome. Methods Enzymol. 2005;398:175–195. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Taylor SS. Cyclin-B1-mediated inhibition of excess separase is required for timely chromosome disjunction. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3325–3336. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Bottger F, Stemmann O, Taylor SS. Protein phosphatase 2A and separase form a complex regulated by separase autocleavage. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24623–24632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt LJ, Krutchinsky AN, Morgan DO. Positive feedback sharpens the anaphase switch. Nature. 2008;454:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature07050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Hatcher R, York JP, Zhang P. Securin and separase phosphorylation act redundantly to maintain sister chromatid cohesion in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4725–4732. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Andreu-Vieyra CV, York JP, Hatcher R, Lu T, Matzuk MM, Zhang P. Inhibitory phosphorylation of separase is essential for genome stability and viability of murine embryonic germ cells. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Andreu-Vieyra CV, Wang M, Cooney AJ, Matzuk MM, Zhang P. Preimplantation mouse embryos depend on inhibitory phosphorylation of separase to prevent chromosome missegregation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1498–1505. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01778-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen A, van der Burg M, Szuhai K, Kops GJ, Medema RH. Chromosome segregation errors as a cause of DNA damage and structural chromosome aberrations. Science. 2011;333:1895–1898. doi: 10.1126/science.1210214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens V, Goris J, Van Hoof C. PP2A: the expected tumor suppressor. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada K, Yao R, Kawaguchi T, Karasawa M, Hoshikawa Y, Ichikawa K, Sugitani Y, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Sugawara M, Yanagida M, Noda T. The selective continued linkage of centromeres from mitosis to interphase in the absence of mammalian separase. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:835–846. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Gonzalez P, Westhorpe FG, Taylor SS. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R966–R980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Rhee K. Separase-dependent cleavage of pericentrin B is necessary and sufficient for centriole disengagement during mitosis. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2476–2485. doi: 10.4161/cc.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon-Mortes MC, Mora-Santos M, Espina A, Pintor-Toro JA, Lopez-Roman A, Tortolero M, Romero F. UV-induced degradation of securin is mediated by SKP1-CUL1-beta TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1825–1831. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Ohsumi K, Iwabuchi M, Kawamata T, Ono Y, Takahashi M. Kendrin is a novel substrate for separase involved in the licensing of centriole duplication. Curr Biol. 2012;22:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabti I, Reis A, Levasseur M, Stemmann O, Jones KT. Securin and not CDK1/cyclin B1 regulates sister chromatid disjunction during meiosis II in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2008;321:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture for quantitative proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;359:37–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-255-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome: a machine designed to destroy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:644–656. doi: 10.1038/nrm1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser SL, Samant MD, Baxter JE, Morrison CG, Fry AM. Oscillation of APC/C activity during cell cycle arrest promotes centrosome amplification. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5353–5368. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape M, Reddy SK, Kirschner MW. The processivity of multiubiquitination by the APC determines the order of substrate degradation. Cell. 2006;124:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schockel L, Mockel M, Mayer B, Boos D, Stemmann O. Cleavage of cohesin rings coordinates the separation of centrioles and chromatids. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:966–972. doi: 10.1038/ncb2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo N, Kumada K, Hirota T. Separase sensor reveals dual roles for separase coordinating cohesin cleavage and cdk1 inhibition. Dev Cell. 2012;23:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmann O, Zou H, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Kirschner MW. Dual inhibition of sister chromatid separation at metaphase. Cell. 2001;107:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmann O, Gorr IH, Boos D. Anaphase topsy-turvy: Cdk1 a securin, separase a CKI. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:11–13. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.1.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yu H, Zou H. Nuclear exclusion of separase prevents cohesin cleavage in interphase cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2537–2542. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou MF, Stearns T. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. 2006;442:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nature04985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger IC, Hauf S, Meinke A, Peters JM. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 2000;103:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger I, Gimenez-Abian JF, Wernic D, Peters JM. Regulation of human separase by securin binding and autocleavage. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1368–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y. Shugoshin: guardian spirit at the centromere. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A, Banerjee S, Zhu X, Philipp I, Iavarone AT, Rape M. Regulation of ubiquitin chain initiation to control the timing of substrate degradation. Mol Cell. 2011;42:744–757. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth KG, Wutz G, Kudo NR, Desdouets C, Zetterberg A, Taghybeeglu S, Seznec J, Ducos GM, Ricci R, Firnberg N, Peters JM, Nasmyth K. Separase: a universal trigger for sister chromatid disjunction but not chromosome cycle progression. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:847–860. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Stemmann O, Anderson JS, Mann M, Kirschner MW. Anaphase specific auto-cleavage of separase. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:246–250. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.