Abstract

Degradation rates of most proteins in eukaryotic cells are determined by their rates of ubiquitination. However, possible regulation of the proteasome's capacity to degrade ubiquitinated proteins has received little attention, although proteasome inhibitors are widely used in research and cancer treatment. We show here that mammalian 26S proteasomes have five associated ubiquitin ligases and that multiple proteasome subunits are ubiquitinated in cells, especially the ubiquitin receptor subunit, Rpn13. When proteolysis is even partially inhibited in cells or purified 26S proteasomes with various inhibitors, Rpn13 becomes extensively and selectively poly-ubiquitinated by the proteasome-associated ubiquitin ligase, Ube3c/Hul5. This modification also occurs in cells during heat-shock or arsenite treatment, when poly-ubiquitinated proteins accumulate. Rpn13 ubiquitination strongly decreases the proteasome's ability to bind and degrade ubiquitin-conjugated proteins, but not its activity against peptide substrates. This autoinhibitory mechanism presumably evolved to prevent binding of ubiquitin conjugates to defective or stalled proteasomes, but this modification may also be useful as a biomarker indicating the presence of proteotoxic stress and reduced proteasomal capacity in cells or patients.

Keywords: 26S proteasomes, proteasome inhibitors, proteasome regulation, Ube3c/Hul5, ubiquitination

Introduction

In mammalian cells, most proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome. This 2.4 MDa, 60-subunit complex selectively degrades proteins that are marked for destruction by covalent attachment of a ubiquitin (Ub) chain (Finley, 2009). The 26S proteasome is composed of the core 20S particle, within which proteins are digested, capped by one or two 19S complexes (PA700) that bind, unfold, and translocate ubiquitinated substrates into the 20S proteolytic chamber (Finley, 2009; Matyskiela & Martin, 2013). Ubiquitinated proteins initially bind to two 19S subunits, Rpn13 or S5a/Rpn10, which function as ‘receptors’ for Ub chains (Finley, 2009). The mammalian genome contains hundreds of enzymes that catalyze ubiquitination of specific proteins. In this process, one of the cell's two Ub-activating enzymes (or ‘E1s’) utilizes ATP to form a highly reactive thioester bond with a Ub molecule's C-terminus. The activated Ub is then transferred onto one of the 40 Ub-conjugating enzymes (or ‘E2s’). E2s can interact with one of the approximately 600 Ub ligases (or ‘E3s’), which confer specificity to the ubiquitination process by binding selectively to a set of protein substrates (Metzger & Weissman, 2010). The E3s conjugate Ub molecules to lysine residue(s) on the substrate and then catalyze the transfer of additional Ubs to one of the lysine residues on the preceding Ub to form Ub chains. In the poly-Ub chains most commonly associated with proteasomal degradation, Ub molecules are linked through lysine 48, although other linkages can also support proteasome function (Kulathu & Komander, 2012).

After a ubiquitinated protein binds to Rpn10 and/or Rpn13, it may be deubiquitinated and released or may become more tightly bound to the proteasome through its polypeptide chain, thus committed to degradation (Peth et al, 2010). During this ATP-dependent degradative process, the polypeptide is threaded through the ATPase ring and the gated entry channel in the 20S core particle, where it is digested to oligopeptides (Smith et al, 2006; Finley, 2009). Meanwhile, the Ub chain is disassembled and released from the substrate by the three proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), the subunit Rpn11, Ubp6/Usp14, and Uch37. Removal of the Ub chain is important to enable the substrate to traverse the narrow entry channel into the 20S particle, and for the Ub molecules to be reutilized in subsequent rounds of ubiquitination and proteolysis (Finley, 2009).

It is generally assumed that rates of degradation of cell proteins are determined solely by their respective rates of ubiquitination and that the 26S proteasome is an unregulated destructive machine that efficiently hydrolyzes all Ub conjugates. However, there is increasing evidence that the degradative capacity of the 26S proteasome is also regulated. The interaction of the ubiquitinated substrate with the 26S-associated DUBs, Usp14 and Uch37, stimulates 20S gate opening and ATP hydrolysis by 19S ATPases (Peth et al, 2009, 2013). Deubiquitination by Usp14 may also promote substrate dissociation from the 26S, and genetic inactivation or pharmacologic inhibition of Usp14 enhances the degradation of several mutated or damaged proteins (Lee et al, 2010). Also, many other proteasome-associated proteins (Verma et al, 2000; Leggett et al, 2002; Guerrero et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2007; Wang & Huang, 2008; Besche et al, 2009; Bousquet-Dubouch et al, 2009a,2009b; Scanlon et al, 2009; Book et al, 2010; Kaake et al, 2010) have been identified in yeast or mammals. It is likely that many of these have regulatory roles, for example the Ub ligase, Ube3c/Hul5, can extend the Ub chains on substrates bound to the proteasome and thus functions as an ‘E4’ to counteract chain disassembly by Usp14 and enhance the processivity of conjugate degradation (Crosas et al, 2006; Chu et al, 2013).

In addition, there have been several reports of posttranslational modifications of proteasome subunits including phosphorylation, N-acetylation, ubiquitination, myristoylation, proteolytic cleavage, O-GlcNAc modification, and ribosylation (Ullrich et al, 1999; Zhang et al, 2003, 2007; Wang et al, 2007, 2010, 2013; Djakovic et al, 2009; Bingol et al, 2010; Isasa et al, 2010; Um et al, 2010; Guo et al, 2011; Keembiyehetty et al, 2011; Overath et al, 2012; Lin et al, 2013), some of which were reported to modulate proteasome localization or peptidase activity. For example, phosphorylation of the ATPase subunit Rpt6 in neurons by CamKIIα leads to proteasome accumulation in dendritic spines (Djakovic et al, 2009; Bingol et al, 2010). A phosphatase (UBLCP1) was shown to associate with the 26S proteasome in the nucleus and to decrease its activity (Guo et al, 2011), and in yeast, mono-ubiquitination of Rpn10 by Rsp5 has been observed to reduce the ability of proteasomes to interact with ubiquitinated substrates (Isasa et al, 2010). Interestingly, caspase-3-mediated cleavage of 19S subunits has been reported to enhance proteasome activity during muscle wasting (Wang et al, 2010), but to inhibit its function during apoptosis (Sun et al, 2004). And ADP-ribosylation of proteasome-associated factor PI31 has been reported to promote proteasome assembly (Cho-Park & Steller, 2013). These examples indicate that proteasome function may be regulated by various modifications that depend on cell type and specific physiological conditions. In short, our understanding of how proteasome function might be regulated by posttranslational modifications is in its infancy, and clear evidence of the physiological importance of most of these modifications that have already been detected is presently lacking.

The present studies describe a novel modification of the mammalian 26S proteasome, which is most pronounced in cells upon treatment with proteasome inhibitors or upon proteotoxic conditions that cause the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins. Aside from their biochemical and cell biological interest, these findings bear relevance to the treatment of human disease because the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib/Velcade (BTZ) and also carfilzomib are now used worldwide in the treatment of multiple myeloma and other hematological cancers (Goldberg, 2012). During the course of our studies to clarify the functions of the proteins associated with mammalian 26S proteasomes, we made the incidental observation that multiple subunits in mammalian proteasomes can be ubiquitinated in vivo and that one Ub receptor, Rpn13, is extensively poly-ubiquitinated. The present studies were therefore undertaken to define the conditions promoting this modification of Rpn13, to identify the responsible Ub ligase and to determine the biochemical consequences on proteasome function through studies on cells and by in vitro reconstitution of this process using purified proteasomes.

Results

Five ubiquitin ligases are associated with the mammalian proteasome

Initially, we set out to identify the proteins that interact with the 26S proteasome during substrate degradation and that might potentially regulate its function. We therefore used quantitative proteomics to measure what proteins associate with these particles upon treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib (BTZ). Blocking proteolysis with inhibitors should capture cofactors as well as subunits that become bound during the course of proteolysis. For these studies, we engineered a stable cell line overexpressing FLAG-tagged proteasome subunit Dss1/Sem1, in a similar manner as described previously (Krogan et al, 2004). We then used quantitative proteomics to determine the changes in proteasome-associated proteins during proteasome inhibition with BTZ. (All the details describing our approach are included in the supplementary material, including detailed methods, figures illustrating experimental design (Supplementary Fig S1), mass spectrometric data (Supplementary Table S1), evaluation by Western blot (Supplementary Fig S2), confirmation of proteasomal integrity (Supplementary Fig S3), as well as a supplementary discussion focused on the mass spectrometric analysis).

As expected, proteasome inhibition caused a marked increase in the levels of Ub conjugates on the proteasome (Supplementary Fig S2). Concomitantly, a number of proteins were found to increase on the 26S particles with BTZ treatment, including five Ub ligases, namely Ube3a/E6AP, Ube3c/Hul5, Rnf181, Huwe1, and Ubr4 (Supplementary Table S1). We then tested whether these five E3s and the other 26S-associated proteins were bound directly to the proteasomes or whether they associate with the 26S indirectly via a poly-Ub chain (e.g. if they remained bound to a ubiquitinated substrate or because they were themselves ubiquitinated). The immobilized 26S particles were treated with the catalytic domain of the potent deubiquitinating enzyme, Usp2 (Renatus et al, 2006), which hydrolyzed efficiently the Ub chains on affinity-purified proteasomes bound to anti-FLAG resin (Supplementary Fig S2), and did not affect the structural integrity of the particles (Supplementary Fig S3). Usp2-mediated removal of Ub conjugates promoted the dissociation from proteasomes of p97, hRad23A and hRad23B, therefore, these proteins must have been bound to the proteasomes via a Ub chain (Supplementary Fig S2C). By contrast, the levels of the E3s Ube3a/E6AP, Ube3c/Hul5, Rnf181, Huwe1, and Ubr4 on the 26S were not affected by the Usp2 treatment (Supplementary Fig S2C).

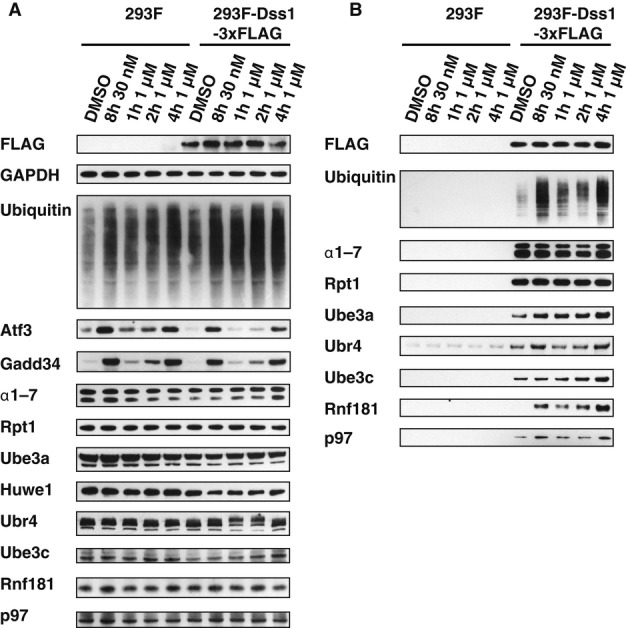

To determine whether the accumulation of these ligases on the proteasome after BTZ treatment simply reflected increased amounts of these ligases in the cells due to inhibition of their degradation, we treated cells with 30 nM BTZ for 8 h or with 1 μM BTZ for 1, 2 and 4 h. All these conditions led to a buildup of Ub conjugates in the cell and on the proteasome, as well as an accumulation of Gadd34, a rapidly degraded substrate of the UPS (Brush & Shenolikar, 2008), and ATF3, a transcription factor that is induced upon proteasome inhibition (Zimmermann et al, 2000; Tanaka et al, 2011). These treatments however did not alter proteasome content nor the amount of these five Ub ligases detected in crude extracts (Fig1A). Nevertheless, greater amounts of all five E3s were observed on the 26S particles isolated from these cells, and their accumulation increased with longer times and higher concentrations of BTZ. Rnf181 and Ube3a/E6AP accumulated on the proteasome within 1 h of BTZ addition (Fig1B), but Ubr4 and especially Ube3c/Hul5 required a longer exposure. Thus, upon inhibition of protein breakdown, several Ub ligases are recruited to the proteasome, but not as a consequence of a change in overall abundance or through an association with Ub chains (Supplementary Fig S2). This redistribution is most dramatic for Rnf181, which is barely detectable on the proteasome under normal conditions (Fig1B and Supplementary Fig S2).

Figure 1. Five ubiquitin ligases accumulate on the 26S proteasome upon inhibition with BTZ.

- HEK293F parental cells and cells stably overexpressing Dss1-FLAG were treated with different concentrations of BTZ for various times. Levels of proteasomes and ligases in the crude extracts were analyzed by Western blot.

- Proteasomes were isolated from cells generated in (A) using anti-FLAG affinity resin. Equal amounts of proteasomes were analyzed by Western blot. Huwe1 was not detectable under these conditions, most likely due to the small amounts of cells used in this experiment compared to those used in our initial purifications (e.g. Supplementary Fig S2C).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Many subunits of the 26S proteasome are ubiquitinated

There are two general roles that Ub ligases could have on the proteasome: they could modify the substrates (e.g. they could function as E4s that elongate Ub chains on proteasome-bound substrates to promote their degradation) or they may modify the proteasome to regulate its function. Curiously, little is known about the potential ubiquitination of proteasome subunits or of 26S-associated proteins. Kim et al (2011) in a cell-wide screen of ubiquitination sites found that many proteasome subunits are ubiquitinated. This conclusion was based upon a whole-cell-lysate analysis of the spectrum of diglycine (GG) ‘signature peptides’, which are generated upon trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins. This study however could not distinguish whether these subunits were ubiquitinated while present in mature assembled proteasomes or as newly synthesized free polypeptides, many of which are rapidly degraded. In order to determine whether subunits of mature proteasome particles are ubiquitinated, we used the GG-antibody approach to identify ubiquitination sites in 26S proteasomes isolated from both normal and BTZ-treated cells. We found that 14 proteasome subunits and 3 proteasome-associated proteins were ubiquitinated, most of them at several different lysine residues (Supplementary Table S2).

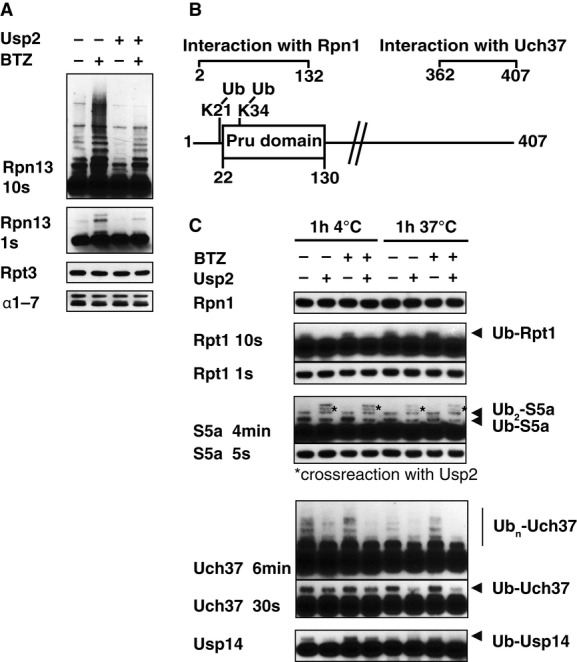

Rpn13 is markedly and reversibly poly-ubiquitinated upon proteasome inhibition

In proteasomes isolated from BTZ-treated cells, ubiquitination of α4, Rpt1, Rpt4, Rpn2, Rpn13, and Usp14 was increased (Supplementary Table S2). Western blot analysis confirmed extensive poly-ubiquitination of Rpn13 that could be removed by digestion with Usp2 at 4°C in vitro (Fig2A). Mass spectrometry indicated that the BTZ-sensitive ubiquitination sites in Rpn13 were lysines K21 and K34, which are located at the N-terminal end of the Ub-binding Pru domain in Rpn13 (Fig2B). Under these conditions, Rpt1 and Usp14 were mono-ubiquitinated, based on a single additional band detectable by Western blotting, which could be removed by Usp2 digestion at 37°C. Unlike Rpn13, their ubiquitination was only slightly enhanced by BTZ treatment (Fig2C). In addition, we were able to detect some poly-ubiquitination of Uch37 and mono/di-ubiquitination of S5a/Rpn10, neither of which were affected by BTZ treatment (Fig2C). Thus, although many subunits can be ubiquitinated in vivo, only modification of Rpn13 and, to a lesser extent, Rpt1 was clearly stimulated by proteasome inhibition.

Figure 2. Ubiquitination of proteasome subunits in cells.

- 26S proteasomes were isolated from Dss1-FLAG-expressing HEK293F cells that were treated with or without 1 μM BTZ for 4 h, and ubiquitination of different subunits analyzed by Western blot (WB). To confirm that these subunits were modified by ubiquitination, these particles were incubated with the deubiquitinating enzyme Usp2 (1 μM) for 1 h at 4°C.

- Schematic view of Rpn13. K34 is located in, and K21 adjacent to the Pru domain responsible for binding of Ub conjugates.

- Proteasomes isolated from normal and BTZ-treated cells were treated with 1 μM Usp2 for 1 h at either 4°C or 37°C. Samples were analyzed by Western blot.

Source data are available online for this figure.

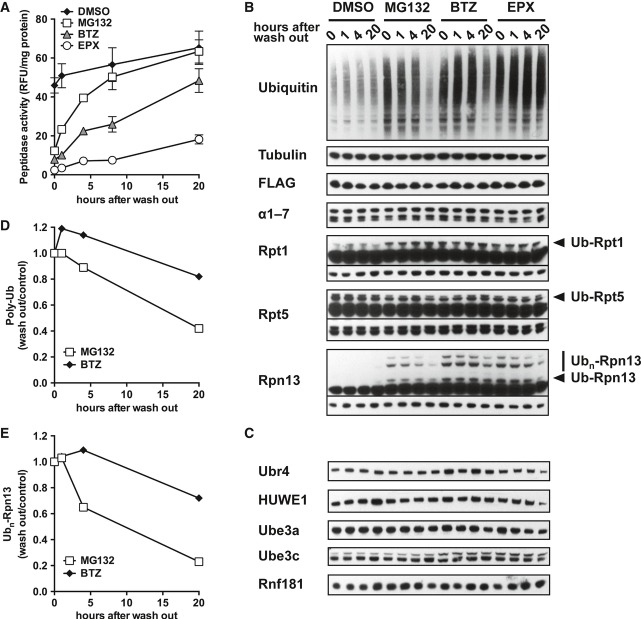

To learn whether the ubiquitination of Rpn13 and Rpt1 also occurs with other types of proteasome inhibitors and whether this ubiquitination is reversible, we treated HEK293F cells with a variety of inhibitors, including BTZ (a reversible peptide boronate inhibitor with a very low off-rate), MG132 (a peptide aldehyde, which is readily reversible), and epoxomicin (a suicide substrate that covalently modifies 20S active threonine) (Kisselev & Goldberg, 2001; Goldberg, 2012) (see Fig3 for HEK293F-Dss1-FLAG cells and Supplementary Fig S4 for the same experiment in the control HEK293F cell line). All three inhibitors were used at concentrations that completely block the chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity and also inhibit either the caspase-like or trypsin-like site and thereby markedly reduce proteolysis (Kisselev & Goldberg, 2001; Kisselev et al, 2006).

Figure 3. Ubiquitination of Rpn13 induced by proteasome inhibition is slowly reversible in vivo.

A HEK293F cells overexpressing Dss1-FLAG were treated with DMSO or proteasome inhibitors (10 μM MG132, 1 μM BTZ, 400 nM epoxomycin) for 4 h. The inhibitor was then washed out, and the cells were grown for additional 1, 4, and 20 h. Crude cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for proteasomal peptidase activity (suc-LLVY-amc).

B–E Cells as in (A) were analyzed by Western blot for accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates, modification of proteasome subunits, and content of proteasome-associated ubiquitin ligases (B, C). The amount of poly-ubiquitin conjugates and ubiquitinated Rpn13 was quantified by densitometry analysis (D, E). For MG132-treated cells, Rpn13 ubiquitination was reduced to less than 25% control level (0 h after washout) 20 h after washout, when proteasome activity and poly-ubiquitin conjugate level were restored to almost normal level. For BTZ-treated cells, 20-h incubation after washout was much less efficient in restoring proteasome activity and poly-ubiquitin conjugate level.

Source data are available online for this figure.

In extracts prepared with DUB inhibitors to prevent deubiquitination, all three inhibitors caused ubiquitination specifically of Rpn13 and Rpt1 (Fig3B and Supplementary Fig S4B). Uch37, Rpt5, and S5a were also modified, but their ubiquitination was not altered by proteasome inhibition. After 4-hour exposure to these inhibitors, the cells were washed twice, and after the addition of fresh medium, the recovery of peptidase activity of 26S proteasomes was monitored (Fig3A). Proteasome activity was almost completely restored to control levels after washout of MG132 for 20 h (Fig3A), and cellular ubiquitin conjugate levels decreased by 60% (Fig3D). In these cells where proteasome function was restored, Rpn13 ubiquitination had declined close to levels in untreated control cells (Fig3E). In the same period, after washout of BTZ, there was much less recovery of proteasome function and a smaller decrease in Ub conjugate levels, and after washout of epoxomicin, there was almost no restoration of activity or decrease in Ub conjugates (Fig3B and E). In these cells, levels of ubiquitinated Rpn13 decreased little if at all (Fig3F). Thus, Rpn13 ubiquitination is a reversible process in vivo and is efficiently removed following the restoration of proteasome function and Ub conjugate level. By contrast, the much less prominent ubiquitination of Rpt1 was not reversed following inhibitor removal.

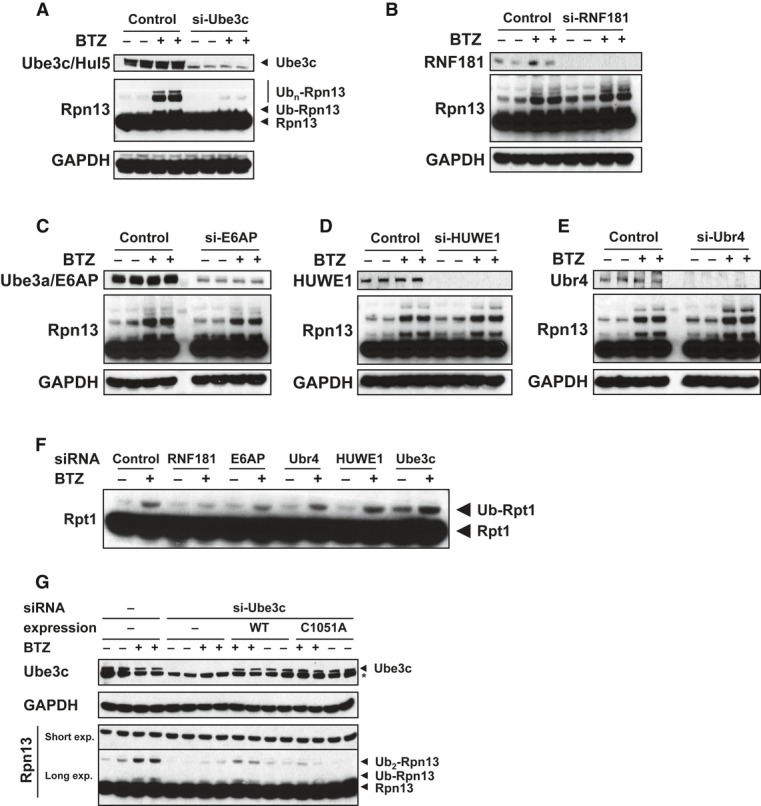

Ube3c/Hul5 ubiquitinates Rpn13, and Rnf181 ubiquitinates Rpt1 in vivo

These findings raised two questions: (i) whether any of the five proteasome-associated ligases may ubiquitinate proteasome subunits, and (ii) whether these modifications may significantly alter proteasome function. In order to determine whether the ligases on the proteasome ubiquitinate 26S subunits, we used siRNA in HEK293 cells to analyze Rpn13 and Rpt1 modification in the absence of each of the E3s found on the 26S. Using this approach, clear results were obtained demonstrating that Ube3c/Hul5 is critical for ubiquitination of Rpn13 in vivo, including its mono-, di-, and poly-ubiquitination (Fig4A). In addition, we found that Rnf181 is the ligase required for monoubiquination of Rpt1 (Fig4F). By contrast, decreasing cell content of Ube3a/E6AP, Huwe1 and Ubr4 did not influence the ubiquitination of either of these subunits (Fig4B–F). None of these 26S-associated ligases seemed to influence the lesser ubiquitination of Rpt5, Uch37/Uch-L5, Rpn10/S5a, or Usp14 (Supplementary Fig S5). To provide further evidence that Ube3c catalyzes Rpn13 ubiquitination, we re-expressed Ube3c [codon-wobbled and resistant to knockdown by Ube3c siRNA (Chu et al, 2013)] in cells expressing Ube3c siRNA. Bortezomib-dependent Rpn13 ubiquitination was restored by re-expression of wild-type Ube3c, but not a catalytically inactive Ube3c mutant (C1051A) (Fig4G). These findings suggest strongly that the 26S-associated Ube3c ubiquitinates Rpn13, especially when proteasome function is inhibited.

Figure 4. BTZ treatment causes poly-ubiquitination of Rpn13 by Ube3c and mono-ubiquitination of Rpt1 by RNF181.

A–E HEK293F cells were transfected with siRNA against proteasome-associated ubiquitin ligases Ube3c/Hul5 (A), Ube3a/E6AP (B), Rnf181 (C), Huwe1 (D), and Ubr4 (E). After BTZ treatment (1 μM, 4 h), cells were lysed, and ubiquitination of Rpn13 (A–E) was measured by WB. Knockdown of Ube3c blocked Rpn13 ubiquitination.

F From the same knockdown experiments as in (A–E), mono-ubiquitination of Rpt1 was also measured by WB. Knockdown of RNF181 blocked Rpt1 mono-ubiquitination.

G When WT Ube3c, but not the catalytically inactive C1051A mutant Ube3c, was re-expressed in Ube3c knockdown cells, basal and BTZ-induced Rpn13 ubiquitination were both restored.

Source data are available online for this figure.

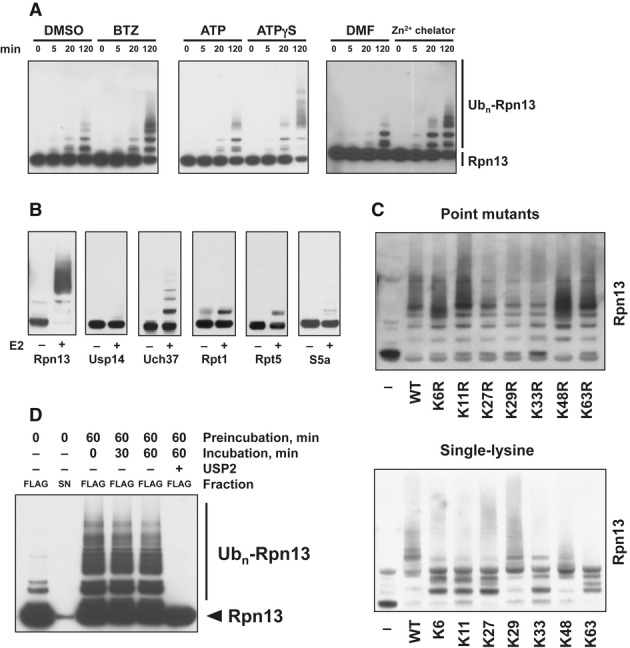

Rpn13 in purified proteasomes can be ubiquitinated by a 26S-associated ligase

Although these findings support a model that after proteasome inhibition, Ube3c acts on Rpn13 and that Rnf181 modifies Rpt1, they do not rule out the possibility that Ube3c/Hul5 and Rnf181 might influence proteasome ubiquitination indirectly (e.g. by 26S association with additional cytosolic factors). To test whether Rpn13 ubiquitination is catalyzed by a 26S-associated E3, proteasomes were affinity-purified with anti-FLAG antibody from control (untreated) cells (as in Supplementary Fig S1C and Fig1B). Since Rnf181 only associated with proteasomes upon proteasome inhibition, these particles lacked significant Rnf181 and contained four Ub ligases. Ubch5a has been used in several publications characterizing Ube3c/Hul5 (You & Pickart, 2001; Wang & Pickart, 2005; Wang et al, 2006). Following incubation with Ub, E1, ATP, and Ubch5a as the E2 for 1–3 h, extensive Rpn13 poly-ubiquitination was evident with only minor modification of Rpt1, Rpt5, S5a, Usp14 or Uch37 (Fig5B). In order to test whether other E2s would work in this reaction, we assayed Rpn13 ubiquitination using the E2scan™ Kit (Ubiquigent), which includes a panel of 29 mammalian E2s. However, the only E2s supporting Rpn13 modification were Ubch5a, b, and c (N. V. Kukushkin, unpublished data).

Figure 5. Reconstitution of Rpn13 ubiquitination using affinity-purified 26S and activation of this process by proteasome inhibition.

- Rpn13 ubiquitination was stimulated by inhibiting 20S function with BTZ, 19S ATPases with ATPγS, or Rpn11 with a Zn2+-chelating agent. Isolated proteasomes were incubated at 37°C for the times indicated in the presence of ATP, Ub, E1, and Ubch5a as the E2. Rpn13 ubiquitination was then analyzed by WB. Left panel, ubiquitination carried out with or without BTZ. Central panel, ATP was substituted with ATPγS where indicated. Right panel, ubiquitination carried out with or without a zinc-chelating agent.

- Only Rpn13 is extensively modified by poly-ubiquitination. Isolated 26S proteasomes were incubated in the presence of ATP, Ub, and E1 with or without the E2 for 2 h at 37°C and analyzed by Western blot. BTZ and Ub aldehyde were included in all reactions.

- Use of single-lysine Ub mutants or Ub mutants lacking specific lysines indicates that Rpn13 was poly-ubiquitinated by predominantly K29 and K48-linked Ub chains. Proteasomes were ubiquitinated as in (A) and (B) with or without wild-type or mutant Ub as indicated, and Rpn13 ubiquitination was analyzed by Western blot. Top panel, Ub point mutants. Bottom panel, single-lysine Ub mutants.

- No deubiquitination of immobilized 26S proteasomes (FLAG) is observed after removing the ubiquitination mixture (S/N) and replacing it with buffer, followed by incubation at 37°C. Usp2 treatment readily deubiquitinates Rpn13 under these conditions.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Ubiquitination of Rpn13 is stimulated by inhibition of either 20S or 19S function

With these affinity-purified particles, we studied further the factors regulating Rpn13 ubiquitination. Unexpectedly, addition of BTZ to the isolated particles markedly enhanced Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig5A, left panel), as was observed in cultured cells. The finding that inhibition of 20S peptidase activities can directly stimulate modification of Rpn13 implies that not only the ubiquitination itself, but also its enhancement by proteasome inhibitors occurs by a mechanism contained within proteasomal particles, as opposed to being mediated by some additional cellular factor. We therefore further explored the connection between proteasome inhibition and induction of Rpn13 ubiquitination on isolated 26S proteasomes. Strikingly, a similar strong enhancement of Rpn13 ubiquitination was observed when the function of the 19S particle was blocked by incubation of the isolated 26S particle with ATPγS (Fig5A, central panel), a non-hydrolyzable analog of ATP that prevents function of the 19S ATPases that drive Ub conjugate degradation (Peth et al, 2009, 2010, 2013). Conjugate degradation also requires the removal of the ubiquitin chain by Rpn11 (Matyskiela et al, 2013). Inhibition of its activity using the Zn2+ chelator, 8MQ (Sekido, 1975), which slows proteolysis of ubiquitin conjugates (N. V. Kukushkin, unpublished observations), also caused a large increase in Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig5A, right panel). Thus, blockage of protein degradation in vitro either through inhibition of the 20S catalytic sites, ATP-dependent processing of Ub conjugates by the 19S complex, or their deubiquitination by Rpn11 prior to translocation into the 20S core stimulates Rpn13 poly-ubiquitination (while the ubiquitination of other subunits is unaffected or enhanced only slightly).

To analyze the type of poly-Ub chain on Rpn13, we used mutant Ub variants lacking each of the seven lysines or containing single lysines (Fig5C). While the point mutation of K27, K29, and K33 reduced ubiquitination of Rpn13 (upper panel), only K29 and K48 were able to support formation of longer chains efficiently on their own (lower panel). Thus, the isolated 26S under these conditions with Ubch5a as the E2 formed long poly-Ub chains on Rpn13 containing mainly K29 and K48 linkages. Other single-lysine mutants supported limited poly-ubiquitination, but these reactions became largely stalled after addition of 1 to 2 Ub moieties (Fig5C, lower panel). This result is consistent with the earlier finding that purified Ube3c/Hul5 preferentially forms K29 and K48 linkages (Wang et al, 2006).

As shown above, upon removal of MG132 from the medium, proteasome function in the cells was slowly restored. Within 20 h, the ubiquitination of Rpn13 (but not ubiquitinated Rpt1) was greatly diminished (Fig3 and Supplementary Fig S4). Therefore, we tested whether ubiquitinated Rpn13 was susceptible to deubiquitination when the isolated 26S particles were incubated in vitro. Following autoubiquitination of immobilized proteasomes for 1 h, the reaction mixture was removed and after extensive washing was replaced with buffer lacking E1, E2, or Ub. No deubiquitination of Rpn13 was observed under these conditions (Fig5D). Thus, none of the three proteasome-associated DUBs, Usp14, Uch37, or Rpn11 could disassemble the Ub chains on Rpn13, even though exogenous Usp2 readily deubiquitinated Rpn13 (Fig5D). Therefore, it seems most likely that in cells following removal of proteasome inhibitors, Rpn13 is deubiquitinated (Fig3 and Supplementary Fig S4) by a currently unknown cytosolic DUB, or perhaps the ubiquitinated Rpn13 may be selectively extracted from proteasomal particles (e.g. by p97) and degraded or deubiquitinated.

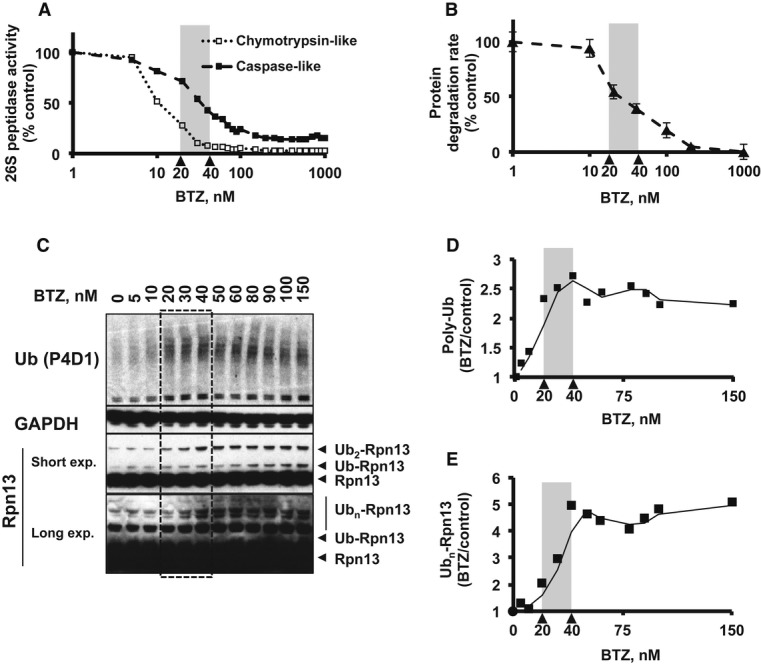

Rpn13 ubiquitination increases with even a partial loss of proteasomal capacity

The observation that Rpn13 ubiquitination is stimulated by BTZ treatment even in vitro indicates that it is an auto-regulatory response to impaired proteasome functioning. To determine how much of an impairment of proteasome function and of intracellular proteolysis is necessary to trigger this response in HEK293F cells, we determined the concentrations of BTZ that are required to cause Rpn13 ubiquitination in cells and their effects on intracellular proteolytic rates.

Upon treatment with 20 nM BTZ for 4 h, we observed over a 50% inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity in cell extracts (Fig6A), which was accompanied by a 2- to 3-fold increase in the total amount of poly-ubiquitinated proteins, detected by Western blot (Fig6C and D). The degradation rates of long-lived cell proteins by the proteasome were reduced by 45% as measured by the conversion of radiolabeled cell proteins to amino acids (Fig6B) [In order to determine proteasomal protein breakdown rate, we subtracted the autophagic/lysosomal degradation rate (Zhao et al, 2007) from total degradation rate; see Materials and Methods]. At lower concentrations, no effect of BTZ on cellular protein degradation was detected. Interestingly, 20 nM was also the lowest concentration of BTZ that caused a clear 2-fold stimulation of Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig6C and E). At 40 nM BTZ, no chymotrypsin-like activity was detected in the extracts, and the proteasome's caspase-like activity was also reduced by over 50%. This increase in BTZ concentration from 20 to 40 nM further reduced cellular protein degradation and caused the amount of poly-Ub conjugates to reach its peak level. This treatment caused a maximal 5-fold induction of Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig6C and E). Increasing the concentration of BTZ beyond 40 nM did not further elevate the levels of Ub conjugates or ubiquitinated Rpn13, even though it caused a greater inhibition of proteasomal protein degradation (Fig6B).

Figure 6. Rpn13 ubiquitination is a sensitive cellular response to impairment of protein degradation.

A HEK293F cells were treated with different concentrations of BTZ for 4 h. The concentration of BTZ that causes a 50% inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like 26S peptidase activity is 20 nM, while the concentration that causes a 50% inhibition of the caspase-like activity is 40 nM.

B Degradation of cellular proteins (prelabeled with 3H-phenylalanine) by the proteasome (see Materials and Methods) is markedly inhibited by BTZ when used at above 20 nM and at 40 nM 60% inhibition is observed.

C–E The effects of different concentrations of BTZ on levels of poly-ubiquitin conjugates and ubiquitinated Rpn13 were assayed by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry. BTZ causes maximal accumulation of poly-ubiquitin conjugates between 20 and 40 nM (D), and 20 nM is also the concentration at which Rpn13 ubiquitination begins to elevate (2-fold of control) (E). At 40 nM, BTZ causes near-maximal level of Rpn13 ubiquitination (5-fold of control). Quantification of ubiquitin conjugate level and Rpn13 ubiquitination was done by densitometric analysis of Western blotting (see Materials and Methods).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Thus, the induction of Rpn13 ubiquitination detectable by Western blot is a highly sensitive indicator of the degree of the impairment of proteasome function. At low BTZ concentrations, the level of Rpn13 ubiquitination reflects the inhibition of overall cellular protein degradation and reaches its peak together with the accumulation of poly-ubiquitin conjugates. The accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated conjugates in the cells, as a consequence of loss of proteasome function, correlates most closely with Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig6D and E). This tight correlation between the extent of Ub conjugate buildup and modification of Rpn13 strongly suggests that these are linked effects of the inhibitors.

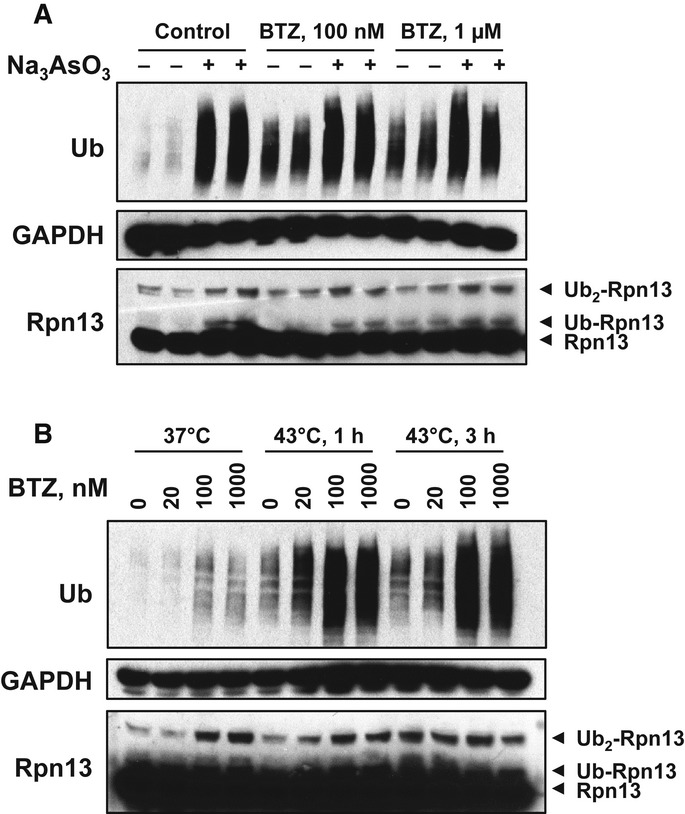

Rpn13 ubiquitination occurs during proteotoxic stress

Rpn13 ubiquitination could not have evolved as a response to proteasome inhibition by drugs. To determine whether this modification occurs in cells without exposure to proteasome inhibitors but does occur under other conditions where ubiquitinated proteins accumulate, we exposed cells to two proteotoxic stress conditions: treatment with arsenite (0.5 μM for 3 h; Kirkpatrick et al, 2003) and heat shock (43°C for 1 h or 3 h; Lindquist, 1986) (Fig7). Both treatments, which cause marked induction of heat-shock proteins, caused Rpn13 ubiquitination, along with an accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins. No decrease in 26S proteasome peptidase activity was evident after either treatment. Arsenite treatment, which caused a greater accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins than BTZ treatment (100 nM or 1 μM), also caused greater Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig7A). On the contrary, 1-h heat shock, which caused a weaker accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins than BTZ treatment, also caused weaker Rpn13 ubiquitination (Fig7B). Upon exposing cells to these proteotoxic conditions together with BTZ, we did not detect any further accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins or Rpn13 ubiquitination compared to when arsenite or BTZ alone was present. These observations indicate that Rpn13 ubiquitination probably occurs often in vivo under conditions that generate large amounts of misfolded, perhaps aggregated, proteins, and cause accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates.

Figure 7. Heat-shock and arsenite treatment cause Rpn13 ubiquitination and accumulation of Ub conjugates.

- HEK293F cells were treated with 0.5 μM Na3AsO3 together with indicated concentrations of BTZ for 3 h. Na3AsO3 dramatically caused the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins and induced Rpn13 ubiquitination as well.

- HEK293F cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BTZ for 3 h at 37°C or under 43°C (heat shock) for 1 or 3 h. Heat shock and arsenite also caused the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins as well as Rpn13 ubiquitination.

Source data are available online for this figure.

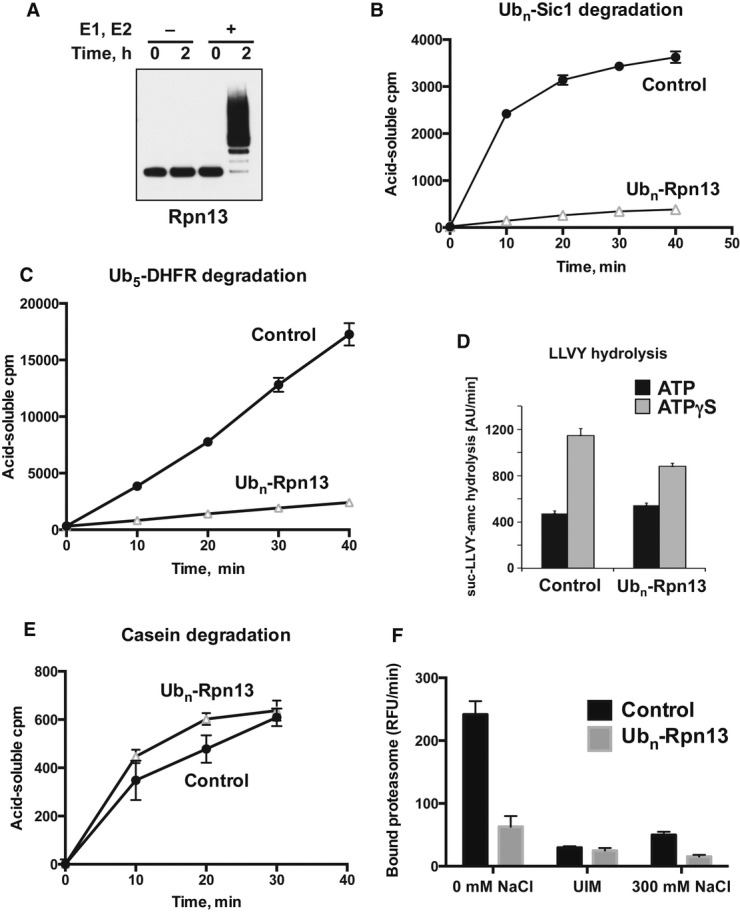

Rpn13 modification inhibits degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, but not peptide substrates

Why would the proteasome ubiquitinate Rpn13 upon accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates or when its proteolytic activity is compromised? One possible explanation is that modification of Rpn13 inhibits its ability to interact with ubiquitin conjugates, thus preventing new substrates from a futile association with a particle that is stalled and incapable of proteolysis. Indeed, the two lysines that are preferably modified upon proteasome inhibition are in, or very close to, the ubiquitin-binding domain in Rpn13 (Fig2B and Supplementary Table S2). Using the affinity-purified 26S proteasome and ubiquitination cofactors (E1, Ubch5a, Ub, ATP, Mg2+), we obtained nearly quantitative ubiquitination of Rpn13 during a 2-h preincubation (Fig8A) with only minor ubiquitination of other subunits observed in the same preparations (similar to what is shown in Fig5B). In order to examine the functional effects of this modification, we preincubated proteasomes under these conditions in the presence or absence of the E2, Ubch5 (Fig8A), and measured the ability of the proteasomes to degrade model ubiquitinated substrates. After Rpn13 modification, there was an 80–90% reduction in the rates of degradation of two widely studied substrates, UbnSic1 (Fig8B) and Ub5DHFR (Fig8C). By contrast, the peptidase activity of these 26S proteasomes (i.e. their ability to hydrolyze the standard fluorogenic substrate, suc-LLVY-amc) was not affected by ubiquitination (Fig8D). Peptidase assays were performed in the presence of ATP or ATPγS. In the presence of ATPγS, which stimulates 20S gate opening and peptide entry (Smith et al, 2005, 2007), we consistently observed a slightly reduced ability for peptide hydrolysis by proteasomes with ubiquitinated Rpn13 (Fig8D), which suggests some alteration in the ATPases or in gate opening (Smith et al, 2007). In addition, no significant change was observed in the rate of casein degradation (Fig8E), an unstructured protein that does not require ubiquitination for ATP-dependent proteolysis (Smith et al, 2006; Peth et al, 2009). Together, these data indicate that ubiquitination of the proteasome causes a dramatic decrease in its capacity for Ub-dependent proteolysis without significantly affecting its activity toward hydrolyzing peptides and non-ubiquitinated proteins.

Figure 8. Rpn13 ubiquitination markedly inhibits the ability of 26S proteasomes to bind and degrade ubiquitinated proteins, but not peptides or non-ubiquitinated proteins.

- Isolated proteasomes were preincubated for 0–2 h at 37°C in the presence of ATP and Ub, with or without E1 and Ubch5a (E2) as indicated and analyzed by Western blot. (Ub aldehyde was included in all reactions to block deubiquitination, but its presence had no significant effect.)

- Proteasomes preincubated for 2 h as in (A) were diluted 20-fold, and the degradation of 32P-labeled Ubn-Sic1 was assayed by measuring the production of TCA-soluble radioactive peptides.

- After preincubation, degradation of 32P-labeled Ub5-DHFR was assayed as in (B).

- To evaluate the effects of Rpn13 modification on hydrolysis of short peptides, proteasomes were preincubated for 2 h as in (A) and diluted 20-fold, and the rate of suc-LLVY-amc hydrolysis was measured in the presence of ATP or ATPγS, which stimulates gate opening and peptide substrate entry (Smith et al, 2007).

- To follow the degradation of a non-ubiquitinated substrate, 26S proteasomes were preincubated as in (A), and the breakdown of 32P-labeled casein to TCA-soluble peptides was assayed as in (B).

- To measure the binding of ubiquitinated proteins, proteasomes were preincubated for 2 h as in (A) and bound to immobilized Ub5-DHFR at 4°C. The resin was washed in a low-salt buffer (0 mM NaCl), high-salt buffer (300 mM NaCl) or in the presence of UIM, and bound proteasome activity was assayed by measuring suc-LLVY-amc hydrolysis (Peth et al, 2010).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Rpn13 ubiquitination inhibits the binding of 26S particles to ubiquitin conjugates

The residues that are ubiquitinated on Rpn13, K21 and K34 (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig2B), are located near or within the Ub-binding domain of Rpn13 (Husnjak et al, 2008). We therefore tested whether Rpn13 ubiquitination decreases conjugate binding to the 26S. Biotinylated Ub5-DHFR was immobilized on a monomeric avidin resin and incubated with control and ubiquitinated proteasomes at 4°C, and proteasomes bound to the resin were quantified as described previously (Peth et al, 2010). Following preincubation of proteasomes with the complete set of ubiquitination components, there was a 70–80% reduction in binding to immobilized Ub5-DHFR compared to control proteasomes that were preincubated in the absence of the E2 (Fig8F). Under these assay conditions at 4°C, the initial high-affinity binding of the Ub chain to the 26S can still occur, but the subsequent transition to Ub-independent binding, disassembly of Ub chains, or substrate degradation are not possible (Peth et al, 2010). Accordingly, the interaction of control particles with Ub5-DHFR was completely disrupted by the addition of the Ub-binding domain, UIM, or a high-salt wash (Fig8F). This sensitivity to UIM or salt is characteristic of specific binding of ubiquitin conjugates to the proteasomes' Ub receptor (Peth et al, 2010). Together, these findings indicate that the ubiquitination of Rpn13 by Ube3c/Hul5 is activated when proteasome function becomes impaired and prevents the further association of these inhibited or dysfunctional particles with other ubiquitinated substrates.

Discussion

These studies have uncovered a surprising, new postsynthetic modification of the 26S proteasome that leads to an inactivation of the particles. Initially, we assumed that the accumulation of Ub ligases on the proteasomes after the inhibition of proteolysis accounted for the increased ubiquitination of proteasome subunits Rpn13 and Rpt1. However, inhibitor treatment of purified proteasomes clearly enhanced Rpn13 poly-ubiquitination in vitro, as occurs in vivo. Therefore, increased binding of cytosolic E3s cannot be the critical stimulus for this modification. Instead, the associated ligases can somehow respond to any type of reduction in proteasome function by activating Rpn13 ubiquitination similarly whether 19S or 20S function is inhibited.

The studies with siRNA clearly showed that Rpn13 is poly-ubiquitinated by Ube3c/Hul5 and that Rnf181 is the ligase for Rpt1, which is the first substrate described for this E3. By contrast, loss of the other three ligases did not affect ubiquitination of these or other subunits, as shown by Western blotting (Fig4). Interestingly, down-regulation of Ube3c/Hul5 not only blocked the formation of a long Ub chain of Rpn13, but also reduced mono- and di-ubiquitination on Rpn13. Thus, the role of Ube3c in this process differs from that of its yeast homolog, Hul5, in the ubiquitination of Rpn10, where a distinct E3 Rsp5 first links one or two Ubs to Rpn10 before the chain is extended by Hul5 (Crosas et al, 2006; Isasa et al, 2010). Unlike the modification of mammalian Rpn13, no modification was observed in yeast Rpn13 upon treatment with proteasome inhibitors (G. Collins, unpublished observations). This is supported by the fact that the lysines that are ubiquitinated in mammalian Rpn13 are conserved in mammals, but not in yeast (Husnjak et al, 2008). On the other hand, in mammalian 26S, there was insignificant ubiquitination of S5a. Thus, the ubiquitination of Rpn13 in mammals and that of Rpn10 in yeast appear to be quite different responses.

It is currently unclear why Ube3c, Rnf181, Ubr4, Huwe1, and Ube3a/E6AP, unlike the great majority of ubiquitin ligases, are found on the proteasome and why they accumulate there with proteasome inhibition. Ubr4 is believed to be the main N-end rule ligase in mammalian cells (Tasaki et al, 2005), and Huwe1 has been reported to ubiquitinate p53 and play a role in DNA repair and apoptosis (Chen et al, 2005; Khoronenkova & Dianov, 2011; Kurokawa et al, 2013). Ube3a/E6AP is a well-characterized HECT ligase that targets p53 for degradation in cells infected with HPV virus and thus contributes to the development of cervical cancer (Talis et al, 1998; Beaudenon & Huibregtse, 2008), but it also has important roles in synaptic plasticity, and its deficiency is associated with mental retardation and Angelman's syndrome (Greer et al, 2010). However, it is totally unclear whether the association of these ligases with the 26S proteasome is related to these or other important functions. The increased association of Ube3c to proteasomes after BTZ treatment is unlikely to drive the enhanced Rpn13 ubiquitination because BTZ also stimulates Rpn13 ubiquitination in the cell-free ubiquitination reaction, where no free Ube3c is available to be attracted to the proteasome.

Valuable insights into the mechanism and consequences of Rpn13 ubiquitination were obtained by reconstituting this process in vitro by incubating 26S purified from untreated cells with the E2, Ubch5a, Ub, E1, and ATP. As seen in vivo, addition of BTZ to this reconstituted system stimulated selective poly-ubiquitination of Rpn13. Importantly, this modification is not only activated by inhibition of 20S catalytic sites with BTZ but also upon inhibition of 19S function with the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS, which competitively inhibits ATP hydrolysis by the 19S AAA ATPases. ATPγS thus reduces Ub conjugate processing even though it actually enhances peptide hydrolysis by the 20S core particle by enhancing opening of the gated substrate entry channel into the 20S (Smith et al, 2005). We also observed a similar induction upon inhibition of Rpn11, a DUB required for proteolysis of ubiquitinated substrates. Because defects in the function of both the 19S or 20S complex stimulate Rpn13 modification, it is possible that inhibition of Ub conjugate processing or the buildup of conjugates on the 19S complex triggers this response. It is interesting in this context that exposing cells to heat shock or arsenite leads to a buildup of ubiquitinated proteins in the cell and also to enhanced ubiquitination of Rpn13 in vivo. The level of Rpn13 ubiquitination under proteotoxic stress conditions correlates tightly with the amount of poly-ubiquitin conjugate accumulation under these conditions. Also, with increasing concentrations of BTZ, the extent of the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins correlated very tightly with the degree of Rpn13 modification, suggesting a causal linkage between these events. Perhaps the accumulation of conjugates themselves on the 19S is the immediate signal activating autoubiquitination of Rpn13, for example aggregated ubiquitinated substrates may interfere with efficient proteasome function, and triggers Rpn13 ubiquitination. By whatever the mechanism that proteotoxic conditions cause Rpn13 ubiquitination, this modification of the receptor for conjugates should accumulate in the cell under these conditions (Fig9).

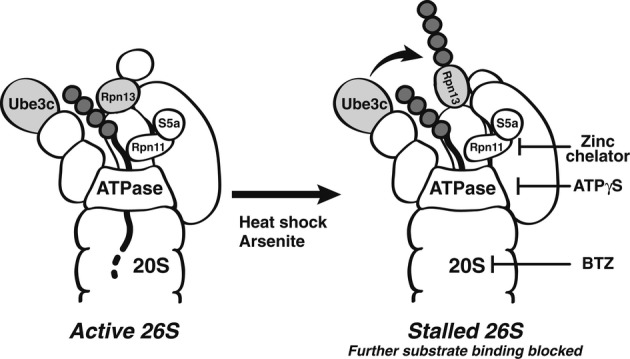

Figure 9. Proposed mechanism for Rpn13 based on the present findings.

Normally, Ub chains on the substrate bind initially to Rpn13 and S5a/Rpn10, and once the polypeptide becomes committed to degradation, it is translocated through the ATPase ring into the 20S (Finley, 2009; Peth et al, 2013). The Ub ligase, Ube3c, presumably functions to extend Ub chains to facilitate substrate degradation and ensure its processivity (Crosas et al, 2006). However, when proteasomes are stalled due to difficult-to-degrade substrates, or during proteotoxic stresses (heat-shock or arsenite exposure), or in vitro when 20S function is inhibited with bortezomib, 19S function slowed with ATPγS, or substrate deubiquitination by Rpn11 is blocked with a Zn2+ chelator, Ube3c ubiquitinates Rpn13 and prevents further substrate binding in vivo.

Once formed, poly-Ub chains on Rpn13 were not removed by any of the proteasome-associated DUB (Fig5D), even though in cells, ubiquitinated Rpn13 slowly disappeared after removal of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig3 and Supplementary Fig S4). Most likely, this deubiquitination in vivo is carried out by other DUBs in the cytosol, and we found that cell extracts contain enzymes capable of Rpn13 deubiquitination (see below). It is also possible that the gradual ‘reversal’ occurs through the replacement of the ubiquitinated Rpn13 by newly synthesized Rpn13 or even through complete replacement of these modified proteasomes with newly synthesized particles, but this latter possibility seems less likely due to the lack of turnover of ubiquitinated Rpn13 in cells following washout of the irreversible 20S inhibitor, epoxomicin.

Most importantly, with the purified 26S particles, we could generate proteasomes in which almost all Rpn13 was modified by poly-ubiquitination, while the other subunits, including S5a/Rpn10, were modified to a much lesser extent (Fig5B). Thus, only ubiquitination of Rpn13 can account for dramatic changes in the activity of the proteasome population. By contrast, quantitative ubiquitination of Rpn13 was not observed in cell lysates, probably due to the strong deubiquitinating activity present in the cell extracts. For example, incubating ubiquitinated 26S particles (prepared as in Fig5B and D) with 293F cell lysates caused complete removal of poly-ubiquitin chains from Rpn13 (unpublished observations), which could not be prevented by addition of N-ethylmaleimide or ubiquitin aldehyde or Zn2+-chelating agents to inhibit most DUBs. Consequently, the level of poly-ubiquitinated Rpn13 observed in cell lysates probably underestimates the extent of poly-ubiquitination of proteasomes actually occurring in vivo. Thus, it remains unclear whether the limited ubiquitination seen in vivo is due to a combination of extensive modification of most cellular proteasomes and partial deubiquitination, or whether, in cells, a specific subset of the 26S proteasomes is selectively modified when proteolysis is inhibited.

The ubiquitination of Rpn13 markedly reduced proteasomal function by a novel mechanism. As predicted, the particle's ability to degrade model ubiquitinated substrates was inhibited by 80–90% with no change in their ability to hydrolyze peptides or non-ubiquitinated unfolded proteins (Fig8). These observations suggest strongly that this mode of proteasome regulation may be occurring in vivo under various pathological conditions that cause the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated conjugates, for example during heat-shock or arsenite treatment, and must be functioning in the many basic or clinical studies with proteasome inhibitors. However, this prevention of ubiquitin-dependent degradation would be missed using standard proteasome assays, which utilize fluorescent peptide substrates and thus only assay 20S gate opening and peptidase activity. This dramatic decrease in the breakdown of ubiquitinated substrates clearly resulted from a defect in their binding to the proteasome (Fig8). Such a large decrease in conjugate binding was surprising since the other conjugate receptor, S5a/Rpn10, was not covalently altered under these conditions. Previously, we found that Rpn10 and Rpn13 contributed equally and independently to the binding of Ub conjugates to the 26S (Peth et al, 2010). These data thus suggest that ubiquitination of Rpn13 probably also inhibits S5a/Rpn10 by an unknown mechanism. Based on recent insights into 19S structure (Beck et al, 2012; Lander et al, 2012), it is possible that the Ub chain formed on Rpn13 might also bind to S5a/Rpn10 and thus prevent the functioning of both receptor subunits simultaneously. We have also attempted to clarify the physiological consequences of Rpn13 modification by mutagenizing the lysine residues on Rpn13 that are modified by ubiquitination by Ube3c, but their loss led to the ubiquitination of other lysines or prevented Rpn13 incorporation into the particles (N. V. Kukushkin, unpublished data).

These responses to proteasome inhibition, both the rapid, extensive, ubiquitination of Rpn13 and the slower association of more E3s with the 26S particles, clearly did not evolve as responses to pharmacological inhibitors. Instead, this modification of Rpn13 probably serves normally as a mechanism to prevent proteasomes from binding additional ubiquitinated substrates when they are stalled or unable to efficiently digest a substrate (as may occur with a ubiquitinated protein aggregate or a damaged proteasome) (Fig9). Indeed, while the exact mechanism by which inhibiting 20S or 19S function triggers Rpn13 ubiquitination is still unclear, ubiquitination of Rpn13 occurs when the substrate load is increased via heat-shock or arsenite treatment (Fig7). In yeast, Hul5 plays a major role in promoting the overall degradation of misfolded proteins by functioning as an E4 (Fang et al, 2011), which extends Ub chains on ubiquitinated substrates. On the proteasome, the extension of Ub chains on substrates seems to compete with their deubiquitination by the 26S-associated DUB, Usp14/Ubp6 (Crosas et al, 2006). Finley and colleagues have proposed a ‘timer model’, where Hul5's E4 activity increases and Ubp6/Usp14 decreases the time available for substrates to be degraded or released from 26S particles (Crosas et al, 2006). It seems likely that ubiquitination of Rpn13 is linked somehow to the role of Ube3c/Hul5 as an E4 that promotes proteasomal degradation of Ub conjugates. Perhaps in normal proteasomes, Ube3c/Hul5 elongates Ub chains on substrates to promote their proteolysis (Fang et al, 2011) but in inhibited or damaged particles, or those engaged with a difficult-to-degrade substrate, Ube3c/Hul5 may instead poly-ubiquitinate Rpn13 and prevent further substrate binding to these particles. Thus, by ubiquitinating Rpn13, Ube3c/Hul5 may prevent the proteasome from a non-productive, perhaps a toxic, engagement with multiple substrates at a time. This modification may thus prevent substrate ‘traffic jams’ at the proteasome, irreversible aggregation of Ub conjugates, or even damage to the particle, which could be potentially harmful to the cell.

Although the cellular consequences of this novel modification under different physiological conditions remain a subject for future research, ubiquitination of Rpn13 appears likely to be of pathophysiological and therapeutic importance. Thousands of patients with multiple myeloma and certain other hematological malignancies are now being treated with proteasome inhibitors (Goldberg, 2012), and based on the present findings, their proteasomes must be undergoing some degree of Rpn13 autoubiquitination. As a consequence of the resulting prevention of Ub conjugate binding, measurements of peptide hydrolysis (as is typically done in drug development) would underestimate the actual degree of inhibition of the Ub-proteasome pathway in these cells. Thus, measurement of Rpn13 poly-ubiquitination might serve as a new biomarker to assess therapeutic efficacy in patients treated with BTZ for multiple myeloma, but also may be valuable to evaluate the extent of proteasome function in neurodegenerative diseases (Takalo et al, 2013; Tanaka & Matsuda, 2013). There is growing evidence that decreased proteasome function is a key factor in pathogenesis in various neurodegenerative diseases, where misfolded, apparently undegradable ubiquitinated proteins accumulate in intraneuronal inclusions, often in association with proteasomes (Takalo et al, 2013; Tanaka & Matsuda, 2013). The ubiquitination of Rpn13 in presence of difficult-to-degrade substrates could indeed create a negative feed-forward loop that contributes to the proteotoxicity of aggregation-prone proteins.

Materials and Methods

Dss1-3×FLAG cells and quantitative proteomics

For purification of human 26S proteasome, a HEK293F cell line stably expressing Dss1-3×FLAG was derived by standard methods. For SILAC experiments (Ong et al, 2002), cells were grown for at least 9 passages in heavy or light SILAC medium and analyzed by LC/MS/MS. Raw MS data were processed using a combination of MaxQuant (version 1.0.13.13) (Cox & Mann, 2008) and Mascot (version 2.2.03, Matrix Science, London, UK). MaxQuant was used for postacquisition precursor m/z calibration, MS/MS spectrum peak picking, SILAC peptide ratio calculation, as well as protein grouping and quantification. Database searching was done using Mascot. The global false discovery rate for both peptides and proteins was set to 0.01. Peptides with di-glycine modified to lysines were enriched following protocols and analysis described by Kim et al (2011).

Western blotting

Cells lysate for SDS-PAGE was prepared in modified RIPA buffer. [20 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2.5 mM Na2H2P2O7, Roche Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet, 100 μl per well (24-well)]. The following antibodies were used: Ubr4 (Abcam ab86738, 1:500), Ube3c/Hul5 (GeneTex Inc. GTX119102, 1:1,000), RNF181 (GeneTex Inc. GTX117747, 1:1,000), Ube3a/E6AP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-25509, 1:1,000), Huwe1 (Abcam ab78397, 1:1,000), Usp14 (Epitomics S3270, 1:1,000), Uch37 (Epitomics 3904-1, 1:10,000), Rpt1 (Enzo Lifesciences BML-PW8825, 1:10,000), Rpt5 (Enzo Lifesciences BML-PW8770, 1:10,000), Rpn1 (Abcam ab21749, 1:10,000), S5a (Enzo Lifesciences BML-PW9250-0100, 1:1,000), GAPDH (Sigma, G8795, 1:10,000), Ub (Enzo Lifesciences BML-PW8810, 1:5,000), Rpn13 (Enzo Lifesciences, BML-PW9910, 1:3,000), 20S (α1,2,3,5,6,7) (Enzo Lifesciences, BML-PW8195, 1:10,000), P4D1 (ubiquitin) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1,000), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, F1804, 1:2,000), tubulin (Rockland, 600-401-880, 1:3,000), Gadd34 (Proteintech, 10449-1-AP, 1:1,500), and ATF3 (Santa Cruz, sc-188, 1:1,000). Quantification of Western blotting band intensity was done by densitometry measurement of individual bands using Quantity One Analysis Software (Bio-Rad).

Proteasome purifications

Cells were lysed by sonication in purification buffer [25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma), 1× Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail, EDTA-free (Roche)]. Proteasomes were purified from the 100,000 g (1 h) supernatant using anti-FLAG resin (Sigma) according to manufacturer's instructions and dialyzed against the storage buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.6-HCl, 25 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 2.1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA pH 8).

siRNA transfection

To knock down proteasome-associated E3s and DUBs in HEK293 cells, siRNA was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology [Ube3a/E6AP (sc-43742) and Huwe1 (sc-61758)] or Thermo Scientific [Ubr4 (L-014021-01-0005), Ube3c/Hul5 (L-007183-00-0005 or J-007183-07-0005), Rnf181 (L-006985-00-0005), Usp14 (L-006065-00-0005), and Uch37 (L-006060-00-0005)]. Transfection mixture containing 20 pmol siRNA and 1 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, 11668-019) was prepared in 100 μl Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, 51985-034) and allowed to mix under room temperature for 20 min before addition to cells (cultured with 500 μl Pen/Strep-free DMEM in a 24-well plate until 30–40% confluency). Transfected cells were treated with BTZ (1 μM, 4 h) 48 h after transfection.

Re-expression of Ube3c

To re-express Ube3c in Ube3c knockdown cells, plasmids expressing codon-wobbled Ube3c (WT or C1051A) were kindly provided by Prof. Thomas Wandless (Stanford University; Chu et al, 2013). These codon-wobbled Ube3c constructs are resistant to knockdown by the specific clone of Ube3c siRNA (Thermo Scientific, J-007183-07-0005). To co-express Ube3c siRNA and Ube3c plasmids in HEK293F cells, transfection mixture was prepared in the same way as siRNA transfection except 1 μg plasmid was added to the mixture.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

Purified 26S proteasomes (5 nM for Western blotting, 10 nM for biochemical assays) were incubated in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and ATP-regenerating system (0.02 U/μl creatine kinase and 2 mM creatine phosphate) with or without 6× His-ubiquitin (120 μM), E1 (50 nM), and Ubch5a (R&D Biosciences) (250 nM) and with or without additional inhibitors as indicated. Reactions were carried out at 37°C for the time periods indicated in the text. For Western blotting, reactions were stopped by adding SDS loading buffer and incubating at 95°C for 5 min.

Measurements of proteasome activity

To determine the peptidase activities of the proteasome, small peptide substrates suc-GGL-amc (measuring chymotrypsin-like activity), suc-LLVY-amc (measuring chymotrypsin-like activity), or Z-LLE-amc (measuring caspase-like activity) were purchased from Bachem. Substrates (50 μM) and proteasomes (0.5 nM) were mixed in the presence of 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 0.01 mg/ml BSA (Sigma) as reported before (Peth et al, 2009). Ub5-DHFR was radiolabeled using PKA (Sigma) and [γ-32P] ATP. Sic1 was radiolabeled before ubiquitination with 32P using CK2 (NEB). β-casein was radiolabeled in the same manner as Sic1. Degradation of radiolabeled substrates by 26S proteasomes (0.5 nM) was measured by following the conversion of the substrate to acid-soluble 32P-labeled peptides after trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation (Lam et al, 2005). Ub5-DHFR was a kind gift from Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Sic1 was expressed, purified, and ubiquitinated as previously described (Saeki et al, 2005).

Measurements of protein degradation

To measure the degradation rate of cellular proteins, HEK293 cells were first labeled for 24 h with tritium-labeled phenylalanine (Phe L-[3,4,5 3H], American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. ART0614, stock 1 mCi/ml in 0.01 M HCl, final 5 μCi/ml) and then chased for 1 h with complete media containing 2 mM cold phenylalanine (Sigma, P5482-25G) to allow turnover of short-lived proteins. Cells were then allowed to be incubated in media containing both 2 mM cold Phe and various concentrations of BTZ. Protein degradation would cause 3H-Phe to be released into the media which could not be precipitated by TCA. Media were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 h during the incubation. 200 μl supernatant after TCA precipitation was mixed with 3 ml Ultima Gold Scintillation Fluid (PerkinElmer, 6013327) and TCA-soluble radioactivity was measured with a PerkinElmer Tri-Carb 2910TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer equipped with QuantaSmart™ software. To calculate percent protein degradation, cells were lysed after the last time point with 0.1 M NaOH, and 100 μl lysate was mixed with 3 ml scintillation fluid in order to measure total radioactivity incorporated. Protein degradation rate was determined by plotting percent protein degradation over time. Four independent samples were used to determine the protein degradation rate upon treatment with various concentrations of BTZ. 27% of the total protein degradation was not inhibited by even high concentrations (200 nM or 1 μM) of BTZ and represents the amount of protein degradation by the autophagy-lysosomal system (Zhao et al, 2007). This portion was subtracted from the total degradation rate in order to determine the cellular protein degradation via the UPS. The degradation rate without BTZ treatment was set to 100%.

Ubiquitin conjugate binding assay

Measurements of the proteasome's ability to bind ubiquitin conjugates was carried out similarly to previously published methods (Peth et al, 2010). Proteasomes were preincubated for 2 h at 37°C with or without Ubch5a and in the presence of all other ubiquitination components, as described above, followed by incubating with immobilized Ub5-DHFR at 4°C for 30 min. No degradation or deubiquitination of Ub5-DHFR was observed in these conditions. After the binding period, resin was first washed at 4°C in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 125 mM potassium acetate, 0.05% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT, then with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM DTT (Tris washing buffer). Samples were then incubated for 2 × 15 min at 4°C either in Tris washing buffer or in the same buffer containing 300 mM NaCl or 2 mg/ml 10×His-UIM. Resin was then washed again in Tris washing buffer and resuspended in the same buffer containing 50 μM suc-LLVY-amc, and resin-bound proteasome activity was measured as above.

For details on proteomic analysis and proteasome purification, see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Discussion.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for research support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS 5R01 GM51923) and Fidelity Biosciences. During these studies, HCB was supported in part by a grant from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., ZS is a Novartis fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation and was a Fellow of the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society, and NVK is a fellow of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.

Author contributions

HCB identified the proteasome-associated ligases and ubiquitination sites on the proteasome subunits, HCB, NVK and AP reconstituted Rpn13 ubiquitination in vitro, NVK characterized this process and its consequences, and ZS conducted the cellular experiments. EMH analyzed the reversibility of Rpn13 modification in vitro, WK performed the GG-peptide analysis, JAG established the Dss1-FLAG cell line and proteasome purification, HL conducted the mass spectrometry on proteasome purifications, SG directs the Mass Spectrometry facility, LD aided in study design, and ALG supervised, conceived, and designed experiments. The manuscript was written by HCB and ALG and edited by NVK, ZS, and AP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information for this article is available online: http://emboj.embopress.org

References

- Beaudenon S, Huibregtse JM. HPV E6, E6AP and cervical cancer. BMC Biochem. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck F, Unverdorben P, Bohn S, Schweitzer A, Pfeifer G, Sakata E, Nickell S, Plitzko JM, Villa E, Baumeister W, Forster F. Near-atomic resolution structural model of the yeast 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14870–14875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213333109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besche HC, Haas W, Gygi SP, Goldberg AL. Isolation of mammalian 26S proteasomes and p97/VCP complexes using the ubiquitin-like domain from HHR23B reveals novel proteasome-associated proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2538–2549. doi: 10.1021/bi802198q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol B, Wang CF, Arnott D, Cheng D, Peng J, Sheng M. Autophosphorylated CaMKIIalpha acts as a scaffold to recruit proteasomes to dendritic spines. Cell. 2010;140:567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book AJ, Gladman NP, Lee SS, Scalf M, Smith LM, Vierstra RD. Affinity purification of the Arabidopsis 26 S proteasome reveals a diverse array of plant proteolytic complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:25554–25569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.136622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Dubouch M-P, Baudelet E, Guérin F, Matondo M, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Burlet-Schiltz O, Monsarrat B. Affinity purification strategy to capture human endogenous proteasome complexes diversity and to identify proteasome-interacting proteins. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP. 2009a;8:1150–1164. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800193-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Dubouch M-P, Nguen S, Bouyssié D, Burlet-Schiltz O, French SW, Monsarrat B, Bardag-Gorce F. Chronic ethanol feeding affects proteasome-interacting proteins. Proteomics. 2009b;9:3609–3622. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brush MH, Shenolikar S. Control of cellular GADD34 levels by the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6989–7000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00724-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Kon N, Li M, Zhang W, Qin J, Gu W. ARF-BP1/Mule is a critical mediator of the ARF tumor suppressor. Cell. 2005;121:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Park PF, Steller H. Proteasome Regulation by ADP-Ribosylation. Cell. 2013;153:614–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BW, Kovary KM, Guillaume J, Chen LC, Teruel MN, Wandless TJ. The E3 ubiquitin ligase UBE3C enhances proteasome processivity by ubiquitinating partially proteolyzed substrates. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:34575–34587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.499350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosas B, Hanna J, Kirkpatrick DS, Zhang DP, Tone Y, Hathaway NA, Buecker C, Leggett DS, Schmidt M, King RW, Gygi SP, Finley D. Ubiquitin chains are remodeled at the proteasome by opposing ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinating activities. Cell. 2006;127:1401–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djakovic SN, Schwarz LA, Barylko B, DeMartino GN, Patrick GN. Regulation of the proteasome by neuronal activity and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:26655–26665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang NN, Ng AH, Measday V, Mayor T. Hul5 HECT ubiquitin ligase plays a major role in the ubiquitylation and turnover of cytosolic misfolded proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1344–1352. doi: 10.1038/ncb2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AL. Development of proteasome inhibitors as research tools and cancer drugs. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;199:583–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer PL, Hanayama R, Bloodgood BL, Mardinly AR, Lipton DM, Flavell SW, Kim TK, Griffith EC, Waldon Z, Maehr R, Ploegh HL, Chowdhury S, Worley PF, Steen J, Greenberg ME. The Angelman Syndrome protein Ube3A regulates synapse development by ubiquitinating arc. Cell. 2010;140:704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero C, Tagwerker C, Kaiser P, Huang L. An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2006;5:366–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Engel JL, Xiao J, Tagliabracci VS, Wang X, Huang L, Dixon JE. 2011. UBLCP1 is a 26S proteasome phosphatase that regulates nuclear proteasome activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Husnjak K, Elsasser S, Zhang N, Chen X, Randles L, Shi Y, Hofmann K, Walters KJ, Finley D, Dikic I. Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. Nature. 2008;453:481–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isasa M, Katz EJ, Kim W, Yugo Vn, González S, Kirkpatrick DS, Thomson TM, Finley D, Gygi SP, Crosas B. Monoubiquitination of RPN10 regulates substrate recruitment to the proteasome. Mol Cell. 2010;38:733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaake RM, Milenkovic T, Przulj N, Kaiser P, Huang L. Characterization of cell cycle specific protein interaction networks of the yeast 26s proteasome complex by the QTAX strategy. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2016–2029. doi: 10.1021/pr1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keembiyehetty CN, Krzeslak A, Love DC, Hanover JA. A lipid-droplet-targeted O-GlcNAcase isoform is a key regulator of the proteasome. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2851–2860. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoronenkova SV, Dianov GL. The emerging role of Mule and ARF in the regulation of base excision repair. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2831–2835. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, Sowa ME, Rad R, Rush J, Comb MJ, Harper JW, Gygi SP. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell. 2011;44:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick DS, Dale KV, Catania JM, Gandolfi AJ. Low-level arsenite causes accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in rabbit renal cortical slices and HEK293 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;186:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(02)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev AF, Goldberg AL. Proteasome inhibitors: from research tools to drug candidates. Chem Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev AF, Callard A, Goldberg AL. Importance of the different proteolytic sites of the proteasome and the efficacy of inhibitors varies with the protein substrate. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:8582–8590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Lam MH, Fillingham J, Keogh MC, Gebbia M, Li J, Datta N, Cagney G, Buratowski S, Emili A, Greenblatt JF. Proteasome involvement in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell. 2004;16:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathu Y, Komander D. Atypical ubiquitylation – the unexplored world of polyubiquitin beyond Lys48 and Lys63 linkages. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:508–523. doi: 10.1038/nrm3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M, Kim J, Geradts J, Matsuura K, Liu L, Ran X, Xia W, Ribar TJ, Henao R, Dewhirst MW, Kim WJ, Lucas JE, Wang S, Spector NL, Kornbluth S. A Network of Substrates of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligases MDM2 and HUWE1 Control Apoptosis Independently of p53. Science signaling. 2013;6:ra32. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YA, Huang JW, Showole O. The synthesis and proteasomal degradation of a model substrate Ub5DHFR. Methods Enzymol. 2005;398:379–390. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander GC, Estrin E, Matyskiela ME, Bashore C, Nogales E, Martin A. Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature. 2012;482:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Lee MJ, Park S, Oh DC, Elsasser S, Chen PC, Gartner C, Dimova N, Hanna J, Gygi SP, Wilson SM, King RW, Finley D. Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature. 2010;467:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature09299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett DS, Hanna J, Borodovsky A, Crosas B, Schmidt M, Baker RT, Walz T, Ploegh H, Finley D. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol Cell. 2002;10:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JT, Chang WC, Chen HM, Lai HL, Chen CY, Tao MH, Chern Y. Regulation of feedback between protein kinase A and the proteasome system worsens Huntington's disease. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:1073–1084. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01434-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyskiela ME, Martin A. Design principles of a universal protein degradation machine. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyskiela ME, Lander GC, Martin A. Conformational switching of the 26S proteasome enables substrate degradation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:781–788. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger MB, Weissman AM. Working on a chain: E3s ganging up for ubiquitylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1124–1126. doi: 10.1038/ncb1210-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overath T, Kuckelkorn U, Henklein P, Strehl B, Bonar D, Kloss A, Siele D, Kloetzel P-M, Janek K. Mapping of O-GlcNAc-sites of 20S proteasome subunits and Hsp90 by a novel biotin-cystamine tag. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP. 2012;11:467–477. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.015966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peth A, Besche HC, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitinated proteins activate the proteasome by binding to Usp14/Ubp6, which causes 20S gate opening. Mol Cell. 2009;36:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peth A, Uchiki T, Goldberg AL. ATP-dependent steps in the binding of ubiquitin conjugates to the 26S proteasome that commit to degradation. Mol Cell. 2010;40:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peth A, Kukushkin N, Bosse M, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitinated proteins activate the proteasomal ATPases by binding to Usp14 or Uch37. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:7781–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renatus M, Parrado SG, D'Arcy A, Eidhoff U, Gerhartz B, Hassiepen U, Pierrat B, Riedl R, Vinzenz D, Worpenberg S, Kroemer M. Structural basis of ubiquitin recognition by the deubiquitinating protease USP2. Structure. 2006;14:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y, Isono E, Toh EA. Preparation of ubiquitinated substrates by the PY motif-insertion method for monitoring 26S proteasome activity. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:215–227. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon TC, Gottlieb B, Durcan TM, Fon EA, Beitel LK, Trifiro MA. Isolation of human proteasomes and putative proteasome-interacting proteins using a novel affinity chromatography method. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:176–189. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekido EFN. Comparison of Properties and Structure of Zinc Chelates of 8-Hydroxyquinoline, 8-Mercaptoquinoline, and 8-Selenoquinoline. Bull Inst Chem Res, Kyoto Univ. 1975;53:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Kafri G, Cheng Y, Ng D, Walz T, Goldberg AL. ATP binding to PAN or the 26S ATPases causes association with the 20S proteasome, gate opening, and translocation of unfolded proteins. Mol Cell. 2005;20:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Benaroudj N, Goldberg A. Proteasomes and their associated ATPases: a destructive combination. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Chang SC, Park S, Finley D, Cheng Y, Goldberg AL. Docking of the proteasomal ATPases' carboxyl termini in the 20S proteasome's alpha ring opens the gate for substrate entry. Mol Cell. 2007;27:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]