Summary

Planar-cell polarity (PCP) describes the polarisation of cell structures and behaviors within the plane of a tissue. PCP is essential for the generation of tissue architecture during embryogenesis and for post-natal growth and tissue repair, yet how it is oriented to coordinate cell polarity remains poorly understood [1]. In Drosophila, PCP is mediated via the Frizzled-Flamingo (Fz-PCP) and Dachsous-Fat (Fat-PCP) pathways [1-3]. Fz-PCP is conserved in vertebrates but an understanding in vertebrates of whether and how Fat-PCP polarizes cells, and its relationship to Fz-PCP signaling, is lacking. Mutations in human FAT4 and DCHS1 cause Van Maldergem syndrome, characterized by severe neuronal abnormalities indicative of altered neuronal migration [4]. Here, we investigate the role and mechanisms of Fat-PCP during neuronal migration using the murine facial branchiomotor neurons (FBM) as a model. We find that Fat4 and Dchs1, key components of Fat-PCP signaling, are expressed in complementary gradients and are required for the collective tangential migration of FBM and for their PCP. Fat4 and Dchs1 are required intrinsically within the FBM and extrinsically within the neuroepithelium. Remarkably, Fat-PCP and Fz-PCP regulate FBM migration along orthogonal axes. Disruption of the Dchs1 gradients by mosaic inactivation of Dchs1 alters FBM polarity and migration. This study implies that PCP in vertebrates can be regulated via gradients of Fat4 and Dchs1 expression, which establish intracellular polarity across FBM cells during their migration. Our results also identify Fat-PCP as a novel neuronal guidance system, and reveal that Fat-PCP and Fz-PCP can act along orthogonal axes.

Results and Discussion

In Drosophila, the Fz-PCP pathway and the Fat-PCP pathway, which includes the protocadherins, Fat and Dachsous (Ds), together with the Golgi kinase, Four-jointed (Fj) [1-3], can work in sequence, in parallel, or independently to define a vector of polarity within tissues. Genetic inactivation in mice of Fat4 and Dchs1, the vertebrate homologues of Fat and Ds, respectively, affect the development of many organs including the kidney, lungs, skeleton, neural tube and ear [5-7]. With the exception of Fat4 regulation of orientated cell divisions in the kidney tubules [6], it is unclear how these phenotypes arise and whether they are linked to PCP. Indeed Dchs1 and Fat4 also appear to influence Hippo signaling in mammals [4, 8], as they do in Drosophila [9], though whether this branch of Fat signaling is truly conserved remains uncertain [10, 11]. Furthermore, in contrast to Drosophila, where it is known that gradients of Ds and Fj across tissues establish polarity, the mechanisms by which Fat4 and Dchs1 impart tissue polarity in vertebrates is unknown.

The Fz-PCP pathway plays fundamental roles in neural development including tangential migration of FBM and olfactory neurons [12-14]. FBM neurons are cranial motoneurons that innervate jaw and facial muscles. In the mouse, FBM neurons arise within rhombomere 4 (r4) of the hindbrain at E10.5. Between E11.5-E13.5, FBM neurons undergo caudal and lateral migrations tangentially i.e. within the plane of the neuroepithelium (Fig. 1A,E,J). At E11.5 migration is exclusively caudal and the FBM neurons stay at the midline, but by E12.5, they also start to turn laterally completing both the caudal and lateral migrations within r6 (Fig. 1A,E; [13]). The FBM neurons finally migrate radially i.e. out of the plane of the neuroepithelium to form a condensed nucleus within the pial layer of r6 by E14.5 (Fig. 1N, S1A,D). The Fz-PCP pathway is essential for caudal tangential migration in mice and zebrafish but how medio-lateral tangential migration is regulated is unknown [15-18].

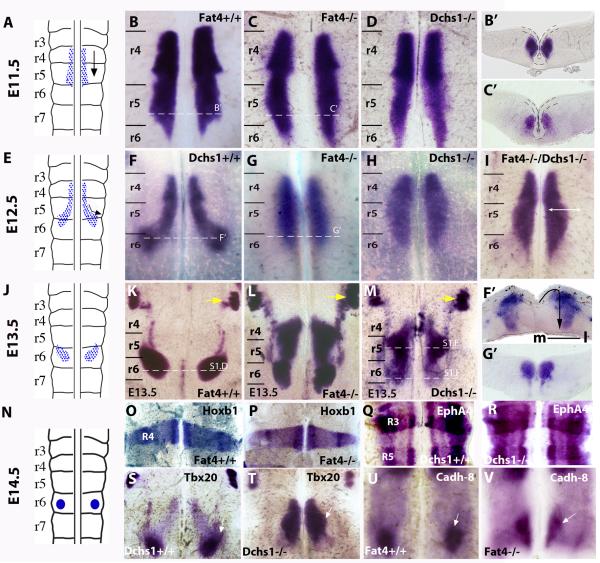

Figure 1. Fat4 and Dchs1 regulate lateral tangential FBM neuronal migration.

Sketch of FBM neuronal migration (A,E,J,N) and flat-mounts of a hindbrain whole-mounted for Islet1 (B-D, F-I, K-M), Hoxb1 (O,P), EphA4 (Q,R ), Tbx20 (S,T) and Cadherin 8 (U,V) expression in E10.5 (O-R), E11.5 (B-D), E12.5 (F-I, S-V), or E13.5 (K-M) wildtype (B,F,K,O,Q,S,U), Fat4−/− (C,G,L,P,V), Dchs1−/− (D,H,M,R,T) or Fat4−/− Dchs1−/− (I), embryos. The trigeminal nucleus is indicated by a yellow arrow in (K-M). The dashed lines indicate levels of sections shown in B’,C’,F’,G’ and in Fig. S1D-F; the ventricular layer is uppermost, the midline is outlined in B’,C’. The arrow in F’ indicates the direction of FBM neuronal migration: initially there is a tangential lateral migration followed by a radial migration from the ventricular layer to the pial surface. (B-D) and (F-H) are viewed from the ventricular surface; and (K-M) from the pial surface. r3-r7, rhombomeres 3-7. The FBM neurons are arrowed in S-V; Cadh-8 is expressed at the leading edge of the FBM neurons in wildtype (U) and Fat4−/− (V) embryos. m, medial; l, lateral

As tangential migrations contribute extensively to the architecture of the brain, and as a potential system for understanding Ds-Fat regulation of PCP in vertebrates, we analysed FBM neuronal migration in Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mouse mutants. Whole-mount in situ hybridisation for Islet1, a motoneuron marker, revealed that initiation of migration occurs normally, but by E12.5 the FBM neurons fail to migrate laterally (Fig. 1B-D, F-H, F’,G’). This is in stark contrast to Fz-PCP Vangl2 mutants where FBM neurons can not initiate caudal migration but can undergo ectopic lateral migration within r4 [18]. At E13.5, FBM neurons in Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutants are still found at the midline and migration is also delayed along the rostro-caudal axis; FBM neurons are still located within r4 and r5 (Fig. 1KMS1E). Within r6, the FBM neurons have undergone radial migration but have not reached the pial surface, by contrast to wildtype FBM neurons (Fig. S1D,F). This may reflect the ectopic route of radial migration and may also reflect additional requirements of Fat4/Dchs1 during radial migration. By E14.5 a facial nucleus spanning r5 and r6 has formed abnormally close to the midline in Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutants (Fig. S1A-C). The severity of the FBM neuronal migration defect in Fat4−/− Dchs1−/− double mutants is the same as Fat4−/− or Dchs1−/− single mutants (Fig. 1I), implying that Fat4 and Dchs1 act as a dedicated signaling pair rather than interacting with other Dchs or Fat genes [5]. Migration of the trigeminal and glossopharyngeal neurons, which do not require Fz-PCP, is unaffected in Dchs1 and Fat4 mutants (Fig. 1K-M yellow arrows; S1G-L, black arrows). These data establish Fat4 and Dchs1 as novel regulators of tangential neuronal cell migration.

In Drosophila, Fat regulates both PCP and also transcription, via the Hippo pathway [9]. FBM neuronal migration is regulated by extrinsic signals within the rhombomeres and intrinsic signals within the FBM neurons themselves. To help exclude transcriptional changes that would influence migration, the expression of Hoxb1, the r4 determination factor, and EphA4, a marker of r3 and r5 identity, together with Tbx20, Nkx6.1, Ret, neogenin and cadherin8, all factors that are expressed during the different phases of FBM neuronal tangential migration through r4 to r6, were analysed [19-22]. Axonal patterning and guidance were also analysed in Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutants. These were found to be unchanged, indicating that transcriptional regulation of hindbrain patterning and FBM neuronal identity is intact (Fig. 1O-V, S1M-O, and data not shown).

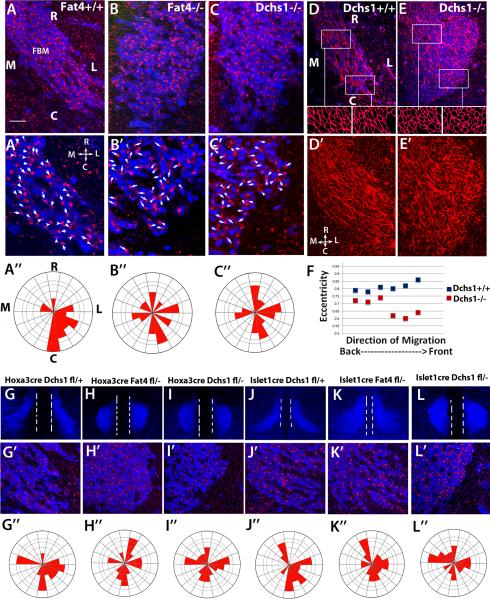

To determine whether Fat4 and Dchs1 regulate PCP, we next analysed the localization of the Golgi apparatus, a marker of neuronal cell polarity [23-26]. In migrating neuronal cells, the Golgi apparatus is found at the leading edge. In wild-type embryos at E12.5, as the FBM neurons enter r6 and are turning laterally, the localization of the Golgi relative to the nucleus becomes strongly polarised in a lateral-caudal direction (Fig. 2A-A”, Rayleigh test, p<10−12). In Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutants, this polarisation does not occur – instead the Golgi are far more randomly localized (Fig. 2B-B”,C-C”, Rayleigh test, Dchs1−/−, p=0.046, Fat4−/−, p=0.05). We also stained hindbrains with phalloidin, to reveal the F-actin cytoskeleton and cell shape. In wildtype embryos, FBM cells are elongated and long actin cables are observed along the direction of neuronal migration, whereas in Dchs1−/− mutants, the FBM neurons are more rounded, particularly at the front of the neuronal stream within r6, and the actin filaments are shorter and less organised (Fig. 2D-F). Thus, FBM neurons become polarised in both shape and orientation along their direction of migration, and this polarity requires Dchs1 and Fat4.

Figure 2. FBM neurons fail to polarise in Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutants.

(A-C) Immunolocalisation showing the polarity of the Golgi (red) in migrating FBM neurons (blue, Islet1 staining) at E12.5 in wildtype (A), Fat4−/− (B) and Dchs1−/− (C) embryos. A’-C’ are higher power images of the leading (caudal) edge. The arrows and arrowheads indicate the long axis of the nucleus and point towards the position of the Golgi apparatus. The angles of the arrows relative to the midline were scored for each neuron and quantified in the Rose Plots below each image (A”-C”). In wildtype embryos the FBM neurons become polarised caudal-laterally at E12.5. This polarisation does not occur in Fat4−/− or Dchs1−/− mutants. (D, E) Phalloidin staining (red) of the FBM neurons (blue, Islet1 staining) in wildtype (D) and Dchs1−/− (E) E12.5 embryos. Outlines of the cell shapes at the leading edge and FBM neurons in the centre of the neuronal stream are shown in the insets below. The cell shape of the FBM neurons is quantified in (F) where 0 is a circle and 1 is an ellipse. D’, E’ show the phalloidin staining alone. Wildtype FBM neurons display actin cables aligned in the direction of migration while Dchs1−/− FBM neurons show a less organised F-actin cytoskeleton. (G-L) Tissue-specific requirements of Fat4 and Dchs1 within the neuroepithelium and the FBM neurons. Low power images of FBM neuronal migration (Islet1 staining, blue) at E12.5 (G-L) together with higher power images of the leading caudal edge of the FBM neuronal stream showing Islet1 (blue) and Golgi (red) immunostaining (G’-L’) and Rose plots of Golgi orientation (G”-L”), in Hoxa3CreDchsf/+ (G), Hoxa3CreFat4f/− (H), Hoxa3CreDchsf/− (I), Islet1CreDchs1f/+ (J), Islet1CreFat4f/− (K) and Islet1CreDchs1f/− (L) E12.5 embryos. The midline is indicated by the two white dashed lines in (G-L). R, rostral; C, Caudal; M, medial; L, Lateral.

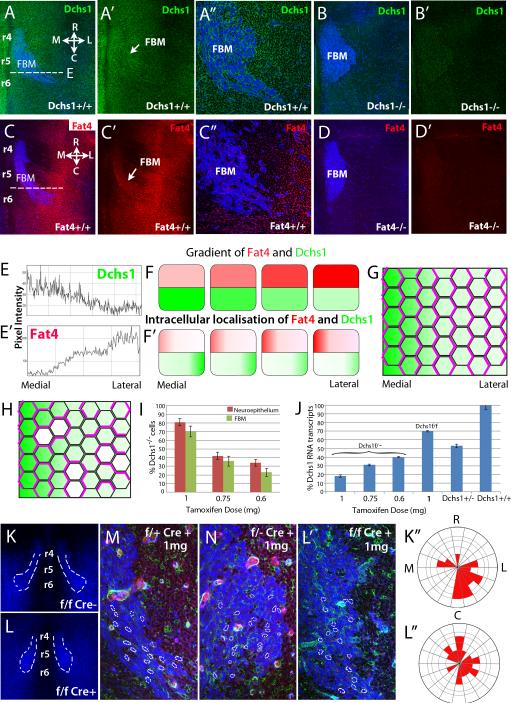

In Drosophila, cells are polarised by the graded expression of Ds and Fj through differential binding of Ds-Fat heterodimers, which is sensitive to the relative amounts of Ds, Fat, and Fj (Fig. 3G)[2, 3]. The graded expression of Ds establishes this polarity and this polarisation is enhanced by the Fj gradient. To understand how Fat4 and Dchs1 direct polarity, and whether mechanisms of Fat-PCP are conserved between Drosophila and vertebrates, we analysed the expression of Fat4 and Dchs1 in E12.5 hindbrains by immunolocalisation and in situ hybridization (Fig. 3A-A”,C-C” and data not shown). Background levels of antibody binding were determined by immunostaining Fat4−/− and Dchs1−/− mutant hindbrains (Fig.2B,B’,D,D’). In wildtype embryos, Fat4 and Dchs1 proteins were detected within the neuroepithelium and the FBM neurons (Fig. 3A-A”,C-C”). Quantification of expression levels within the neuroepithelium showed that Dchs1 and Fat4 are expressed in opposing gradients across the medio-lateral axis i.e. along the direction of lateral FBM neuronal migration. Expression of Dchs1 is highest medially whereas Fat4 expression is highest laterally (Fig. 3E,E’). There are also variations from rostral to caudal: Dchs1 expression is slightly higher rostrally whilst Fat4 expression is slightly higher caudally (Fig. 3A,C-A’,C’). Fjx1 is expressed in a complementary gradient to Dchs1 within the neuroepithelium (Fig. S1P-P”). Fjx1−/− mutants do not have any detectable FBM neuronal migration or Golgi polarity defects (Fig. S1T,U-T’,U’), but we note that in Drosophila fj mutants have weaker phenotypes than ds or fat mutants. Our observations provide the first indication that gradients or differential expression of Fat4 and Dchs1 across a tissue may direct polarised cell behaviours in vertebrates, as their homologues in Drosophila do (Fig. 3F,G) [10]. Although Fat is generally not expressed in a gradient in Drosophila (aside from in the wing [27]), modeling implies that gradients of either Dchs1 or Fat4 could promote their polarisation [28]. Opposing gradients of Dchs1 and Fat4 would be predicted to reinforce this polarisation (Fig. 3F,F’).

Figure 3. Gradients of Fat4 and Dchs1 expression may regulate FBM neuronal migration.

(A-D) E12.5 mouse hindbrains, stained for Islet1 to mark FBM neurons (blue) and (A,B) Dchs1 (green) or (C,D) Fat4 (red). (B,D) Antibody stains on mutant embryos, as a control for background staining. (E and E’) show intensity scan across the dashed line in (A, C) respectively to quantify expression gradients. (A” and C”), high power views of the FBM neurons. (F) Illustrates the Dchs1 and Fat4 expression gradients. (F’), the predicted intracellular localization of Dchs1 and Fat4 across the medio-lateral axis of cells. (G) Illustrates a field of cells polarised (indicated by polarised localization of pink lines) in response to a Dchs1 gradient (green). (H) Illustrates the expected consequences of small patches of Dchs1−/− cells (white). Cells locally repolarize around the mutant cells, and this repolarisation can propagate into neighbouring cells. Consequently, even though overall Dchs1 expression is only modestly affected, PCP is severely disturbed. (I-L) Cre-induced mosaic reduction in Dchs1 expression. (I) shows the percentage of GFP positive cells i.e. levels of mosaicism at different tamoxifen doses in the neuroepithelium and FBM neurons. (J) qPCR of Dchs1 expression in the hindbrain relative to heterozygous and wildtype mice in mosaics in Dchs1f/− and Dchs1f/f backgrounds. (K-L) Effect of Cre mosaicism on FBM neuronal migration visualised by Islet1 immunostaining (blue); the degree of mosaicism indicated by the GFP cells (green) in a tomato background (red in M,N), the nuclear shape and orientation of FBM neurons is outlined in (M,N,L’). (M-L), FBM neuronal migration in 1mg tamoxifen-induced heterozygous (Dchs1f/+Cre+ve (control,M), Dchs1f/−Cre+ve (N)) or wildtype (K,L; K is the control Cre-ve embryo and L is the Cre+ve embryo) backgrounds. For clarity, FBM neurons are outlined in (K,L). L’ is a high power view of the leading edge of the FBM neuronal stream shown in (L). (K”,L”) Golgi polarity in the FBM neurons in (K,L) is quantified in the Rose plots. R, rostral; C, Caudal; M, medial; L, Lateral. r, rhombomere

FBM neurons migrate towards the region of highest Fat4 expression and away from the regions of highest Dchs1 expression. We considered three potential models for how Fat4 and Dchs1 might function. First, Fat4-Dchs1 signalling may regulate the expression of a factor essential for migration. Second, differential cell adhesion between Fat4- and Dchs1-expressing cells may promote the formation of stable lamellipodia towards the area of highest Fat4 expression (or reduce protrusion stability in areas of high Dchs1 expression) or third, the differential expression of Fat4 and Dchs1 across the hindbrain may establish both intracellular polarity and polarity across the neuronal stream ensuring each cell knows the “front from the back”.

In Drosophila, the graded binding activity of Ds and Fat across a tissue establishes cell polarity through a mechanism that depends upon local cell-cell interactions; indeed, polarisation of cells by juxtaposition of cells with substantial differences in Ds expression levels can propagate through a tissue (Fig. 3G) [29-31]. Our expectation is that the gradients of Dchs1 and Fat4 lead to their polarisation within cells, as in Drosophila (Fig. 3F,F’). The medio-lateral gradient of Dchs1 will promote the accumulation of Fat4 on the medial side of the cells whereas the lateral-medial gradient of Fat4 will promote the accumulation of Dchs1 on the lateral side (Fig. 3F’). Therefore, each cell is expected to be characterised by differential localization of both Fat4 and Dchs1 across its medio-lateral axis. While we could not directly visualize polarisation of Fat4 or Dchs1 by antibody staining, direct detection of Ds or Fat polarisation is also not readily detected by simple antibody staining in most Drosophila tissues [30, 31]. However, a hallmark of this type of mechanism is that it can be easily disrupted by small patches of mutant cells, because they block cell-to-cell propagation of PCP (Fig. 3H). Conversely, alternative mechanisms, such as differential cell-adhesion or transcriptional or other mechanisms that depend simply upon Dchs1 or Fat4 levels could be expected to tolerate small patches of mutant cells.

To distinguish between these mechanisms, we generated random genetic mosaics with small patches of Dchs1−/− cells by using a conditional Dchs1mT/mG allele in which tamoxifen treatment activates Cre recombinase and GFP expression in a tomato background. Mosaics were generated in either Dchs1f/f (i.e. Dchs1−/− cells in a Dchs1+/- background) or Dchs1f/f (i.e. Dchs1−/− cells in a Dchs1+/+ background). The degree of tamoxifen-induced recombination was determined by quantifying the percent of GFP-expressing cells, which depends upon Cre expression in this background (Fig.3I). This showed that tamoxifen treatment affects the FBM neurons and the surrounding neuroepithelial cells almost equally (Fig. 3I). We also confirmed reduction in Dchs1 expression by qPCR (Fig. 3J). We found that both migration and polarity (neuronal shape and directionality, Golgi polarity) of the FBM neurons were significantly disrupted in mosaics, with the severity of the disruption depending upon the tamoxifen dose, correlating with the proportion of Dchs1−/− cells (Fig. 3I,J,M,N; S2A-D, Rayleigh test for Golgi polarisation, wildtype p<10−12: Dchs1 mosaics, p>0.5; Mardia-Watson-Wheeler analysis for the difference between controls and mosaics, p<10−12). Consistent with our hypothesis that Fat4-Dchs1 act through PCP, even mosaics consisting of as few as 30% Dchs1−/− mutant cells in a wildtype background exhibited disruptions of polarity and migration of the FBM neurons (Fig. 3K,L, L’, K”,L”). As FBM neuronal migration is normal in Dchs1 heterozygous embryos our observations strongly imply that continuous expression of Dchs1 across the hindbrain is required for PCP. We also examined mosaics generated in Dchs1f/+

(i.e. Dchs1−/+ cells in a Dchs1+/+ background). These did not visibly disrupt FBM neuronal migration or polarity (Fig. 3M), which we interpret as indicating that local, two-fold differences in Dchs1 levels are not sufficient to disrupt PCP. Extreme differences in Ds expression levels disrupt PCP in Drosophila [3,4], but a local 50% difference in Fat levels does not abolish normal polarity in Drosophila wing cells [31].

In zebrafish, Fz-PCP pathway components are required for polarity and migration cell-autonomously within the FBM neurons and non-cell autonomously within the neuroepithelial cells [14, 32]. Fat4 and Dchs1 are expressed both within the FBM neurons and the neuroepithelium; to determine where they act we conditionally inactivated them either in the FBM neurons using Islet1Cre (Fig.S3H-L) [33], or in the neuroepithelium using Hoxa3Cre (Fig. S3A-D) [34]. Hoxa3Cre is expressed within r5 and r6, where FBM neurons undergo lateral migration, but does not affect r4, where they originate (Fig. S3A). Inactivation of either Dchs1 or Fat4 in the neuroepithelium or Dchs1 in the FBM neurons totally blocked lateral migration and disrupted FBM neuronal polarity (Figs. 2G-J,L-2G”-J”,L”, S3E-G,O; Rayleigh test for Golgi polarity, control, p <10−12, Hoxa3CreDchs1f/−, p= 0.9; Islet1CreDchs1f/−, p=0.15; Hoxa3CreFat4f/−, p=0.05). Inactivation of Fat4 within the FBM neurons had a less severe effect on migration but did affect their polarity and co-ordinated cell behaviour (Fig. 2K-K”, S3M,N, Rayleigh test for Golgi polarity, control, p <10−12, Islet1Cre Fat4f/−, p=4x10−4). Thus, Dchs1 and Fat4 are each required both within the FBM neurons and the cells through which they migrate for normal polarity and migration. These observations are consistent with a mechanism in which the polarity of individual cells within the FBM neuronal stream influences their migration, and this polarity is established both by interpretation of the long range gradients of Dchs1 and Fat4 across the hindbrain neuroepithelium, and also by local cell-cell interactions that communicate the polarisation of individual cells to their neighbours. The distinct requirements for Dchs1 versus Fat4 in the FBM neurons raise the possibility that FBM neuronal polarity is primarily dependent upon the polarization of Dchs1, which is absolutely dependent upon interaction with Fat4 in the neuroepithelium, but only partially dependent upon interaction with Fat4 within the FBM neurons themselves. Dchs1 within the neuroepithelium could then be required to establish polarization of Fat4. However, it's also possible that differences in the effectiveness of excision, or the stability of Dchs1 versus Fat4 proteins, could account for the distinct effects of Islet1Cre–mediated excision.

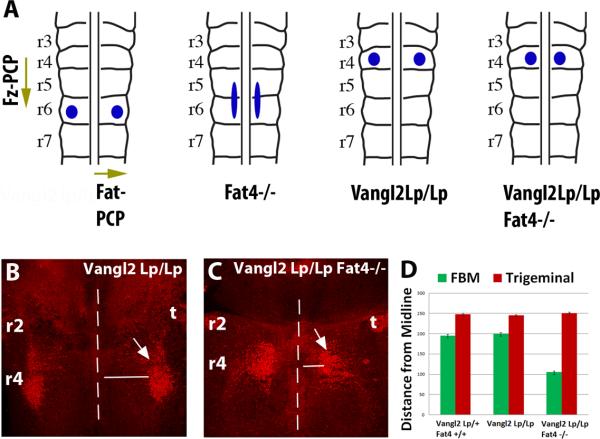

In Fat4−/− or Dchs1−/− mutants, the FBM neurons cannot turn laterally within r5 and r6. By contrast, in the absence of Vangl2, a key Fz-PCP component, FBM neurons do not initiate caudal migration, but undergo ectopic lateral migration within r4 [15, 17, 18] (Fig. 4A,B). As Dchs1 and Fat4 are also expressed in opposing medio-lateral gradients within r4 (Fig. 3A,C,A’,C’), we hypothesized that Fat-PCP guides this ectopic lateral migration in the Fz-PCP mutant, with Fz-PCP and Fat-PCP operating independently across orthogonal rostralcaudal and medio-lateral axes. To test this, we analysed FBM neuronal migration in Vangl2Lp/Lp Fat4−/− double mutants. Indeed, the ability of the FBM neurons, but not the control trigeminal neuron, to migrate laterally in Vangl2Lp/Lp mice is reduced in the absence of Fat4 (Fig. 4A-D). Thus Fat-PCP can act as a global cue across r4-r6 to regulate FBM neuronal medio-lateral polarity and migration.

Figure 4. Fat-PCP and Fz-PCP act along orthogonal axes to guide FBM neuronal migration.

(A) Schematics showing Fz-PCP and Fat-PCP regulation of FBM neuronal tangential migration along orthogonal axes. The blue circles/ellipse indicate the final position of the FBM at E14.5 in wildtype, Fat4−/− (and Dchs1−/−), Vangl2LpLp and Vangl2LpLp Fat4−/− mouse mutants. (B-D) FBM neuronal migration visualised by Islet1 immunostaining (red, arrowed) in Vangl2LpLp and Fat4−/−/Vangl2 LpLp E13.5 embryos. The FBM neurons have been viewed from the pial surface. The midline is indicated by a dashed line. The extent of lateral migration of the FBM, and the control trigeminal neuron which is unaffected, is quantified in (D). r, rhombomere; t, trigeminal

Collective cell migrations are essential for the embryonic development of many tissues and also occur post-natally during wound healing or the invasion of cancer cells. The mechanisms that control collective cell migrations ensuring polarity and co-ordination of cell movement are unclear although the Fz-PCP pathway has been clearly implicated [35]. Here we show that Fat4 and Dchs1 are essential for the collective migration of FBM neurons. Our data establish the FBM neurons as a paradigm for Fat-PCP regulation of polarised cell behaviours in vertebrates and establish Fat4 and Dchs1 as a new class of guidance molecules. Our studies have also identified a novel form of tissue polarity in which Fat-PCP and Fz-PCP regulate polarity along orthogonal axes. Finally, we note that mutations in human DCHS1 and FAT4 cause Van Maldergem syndrome [4], a multi-syndromic genetic disease whose symptoms include intellectual disability indicative of neuronal migration defects [36]. To date loss of Fat4-Dchs1 signaling has been shown to regulate cortical cell proliferation but a clear of demonstration of Fat4-Dchs1 regulation of neuronal migration has not been shown[4]. Since Dchs1 and Fat4 are widely expressed in other brain regions [5, 37], we hypothesize that Fat-PCP regulates the migration of other neuronal cell types and that de-regulation of Fat-PCP might also be linked to other neuronal pathologies characterized by altered cell migration such as epilepsy and autism spectrum disorders.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Fat4 and Dchs1 regulate neuronal cell polarity and tangential migration

FBM are polarised along gradients of Fat4 and Dchs1 expression

Mosaic inactivation of Dchs1 disrupts FBM PCP and migration

The Fat-PCP and Fz-PCP pathways can direct PCP along orthogonal axes

Acknowledgments

The research is funded by the BBSRC (BB/G021074/1 and BB/K001671/1, PFW), King's College London Scholarship (SZ) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (KI). We thank Magdalena Götz, Tanoue Ishiuchi, Kieran Jones, Clemens Kieckers, Ivo Lieberam, Liqun Luo, Anne Moon, Michelle Studer, Alfredo Varela-Echavarria, and departmental colleagues, for helpful discussions, gifts of plasmids and reagents, Giovanna Lalli, Jeremy Green, Eileen Gentleman and Michele Studer for comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Goodrich LV, Strutt D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development. 2011;138:1877–1892. doi: 10.1242/dev.054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matis M, Axelrod JD. Regulation of PCP by the Fat signaling pathway. Genes & Development. 2013;27:2207–2220. doi: 10.1101/gad.228098.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas C, Strutt D. The roles of the cadherins Fat and Dachsous in planar polarity specification in Drosophila. Developmental dynamics. 2011;241:27–39. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappello S, Gray MJ, Badouel C, Lange S, Einsiedler M, Srour M, Chitayat D, Hamdan FF, Jenkins ZA, Morgan T, et al. Mutations in genes encoding the cadherin receptor-ligand pair DCHS1 and FAT4 disrupt cerebral cortical development. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1300–1308. doi: 10.1038/ng.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao Y, Mulvaney J, Zakaria S, Yu T, Morgan KM, Allen S, Basson MA, Francis-West P, Irvine KD. Characterization of a Dchs1 mutant mouse reveals requirements for Dchs1-Fat4 signaling during mammalian development. Development. 2011;138:947–957. doi: 10.1242/dev.057166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–1015. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saburi S, Hester I, Goodrich L, McNeill H. Functional interactions between Fat family cadherins in tissue morphogenesis and planar polarity. Development. 2012;139:1806–1820. doi: 10.1242/dev.077461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das A, Tanigawa S, Karner CM, Xin M, Lum L, Chen C, Olson EN, Perantoni AO, Carroll TJ. Stromal-epithelial crosstalk regulates kidney progenitor cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ncb2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staley BK, Irvine KD. Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Developmental Dynamics. 2012;241:3–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan G, Feng Y, Ambegaonkar AA, Sun G, Huff M, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Signal transduction by the Fat cytoplasmic domain. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140:831–842. doi: 10.1242/dev.088534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bossuyt W, Chen C-L, Chen Q, Sudol M, McNeill H, Pan D, Kopp A, Halder G. An evolutionary shift in the regulation of the Hippo pathway between mice and flies. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tissir F, Goffinet AM. Shaping the nervous system: role of the core planar cell polarity genes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:525–535. doi: 10.1038/nrn3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wanner SJ, Saeger I, Guthrie S, Prince VE. Facial motor neuron migration advances. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada H, Okamoto H. Roles of noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway genes in neuronal migration and neurulation in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:3–8. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasco DM, Sittaramane V, Bryant W, Fritzsch B, Sawant A, Paudyal A, Stewart M, Andre P, Cadete Vilhais-Neto G, Yang Y, et al. The mouse Wnt/PCP protein Vangl2 is necessary for migration of facial branchiomotor neurons, and functions independently of Dishevelled. Dev Biol. 2012;369:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu Y, Glasco DM, Zhou L, Sawant A, Ravni A, Fritzsch B, Damrau C, Murdoch JN, Evans S, Pfaff SL, et al. Atypical cadherins Celsr1-3 differentially regulate migration of facial branchiomotor neurons in mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9392–9401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0124-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tissir F, Goffinet AM. Planar cell polarity signaling in neural development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vivancos V, Chen P, Spassky N, Qian D, Dabdoub A, Kelley M, Studer M, Guthrie S. Wnt activity guides facial branchiomotor neuron migration, and involves the PCP pathway and JNK and ROCK kinases. Neural Dev. 2009;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song MR, Shirasaki R, Cai CL, Ruiz EC, Evans SM, Lee SK, Pfaff SL. T-Box transcription factor Tbx20 regulates a genetic program for cranial motor neuron cell body migration. Development. 2006;133:4945–4955. doi: 10.1242/dev.02694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandrasekhar A. Turning heads: development of vertebrate branchiomotor neurons. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:143–161. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garel S, Garcia-Dominguez M, Charnay P. Control of the migratory pathway of facial branchiomotor neurones. Development. 2000;127:5297–5307. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wanner SJ, Prince VE. Axon tracts guide zebrafish facial branchiomotor neuron migration through the hindbrain. Development. 2013;140:906–915. doi: 10.1242/dev.087148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagida M, Miyoshi R, Toyokuni R, Zhu Y, Murakami F. Dynamics of the leading process, nucleus, and Golgi apparatus of migrating cortical interneurons in living mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16737–16742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209166109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jossin Y, Cooper JA. Reelin, Rap1 and N-cadherin orient the migration of multipolar neurons in the developing neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:697–703. doi: 10.1038/nn.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Causeret F, Terao M, Jacobs T, Nishimura YV, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Hoshino M, Nikolic M. The p21-activated kinase is required for neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:861–875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellion A, Baudoin JP, Alvarez C, Bornens M, Metin C. Nucleokinesis in tangentially migrating neurons comprises two alternating phases: forward migration of the Golgi/centrosome associated with centrosome splitting and myosin contraction at the rear. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5691–5699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1030-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao Y, Kucuk B, Irvine KD. Drosophila lowfat, a novel modulator of Fat signaling. Development. 2009;136:3223–3233. doi: 10.1242/dev.036152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mani M, Goyal S, Irvine KD, Shraiman BI. Collective polarization model for gradient sensing via Dachsous-Fat intercellular signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307459110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosveld F, Bonnet I, Guirao B, Tlili S, Wang Z, Petitalot A, Marchand R, Bardet PL, Marcq P, Graner F, et al. Mechanical Control of Morphogenesis by Fat/Dachsous/Four-Jointed Planar Cell Polarity Pathway. Science. 2012;336:724–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1221071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambegaonkar AA, Pan G, Mani M, Feng Y, Irvine KD. Propagation of Dachsous-Fat Planar Cell Polarity. Current Biology. 2012;22:1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brittle A, Thomas C, Strutt D. Planar Polarity Specification through Asymmetric Subcellular Localization of Fat and Dachsous. Current biology. 2012;22:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh GS, Grant PK, Morgan JA, Moens CB. Planar polarity pathway and Nance-Horan syndrome-like 1b have essential cell-autonomous functions in neuronal migration. Development. 2011;138:3033–3042. doi: 10.1242/dev.063842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L, Cai CL, Lin L, Qyang Y, Chung C, Monteiro RM, Mummery CL, Fishman GI, Cogen A, Evans S. Isl1Cre reveals a common Bmp pathway in heart and limb development. Development. 2006;133:1575–1585. doi: 10.1242/dev.02322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macatee TL, Hammond BP, Arenkiel BR, Francis L, Frank DU, Moon AM. Ablation of specific expression domains reveals discrete functions of ectoderm- and endoderm-derived FGF8 during cardiovascular and pharyngeal development. Development. 2003;130:6361–6374. doi: 10.1242/dev.00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munoz-Soriano V, Belacortu Y, Paricio N. Planar cell polarity signaling in collective cell movements during morphogenesis and disease. Curr Genomics. 2012;13:609–622. doi: 10.2174/138920212803759721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mansour S, Swinkels M, Terhal PA, Wilson LC, Rich P, Van Maldergem L, Zwijnenburg PJG, Hall CM, Robertson SP, Newbury-Ecob R. Van Maldergem syndrome: further characterisation and evidence for neuronal migration abnormalities and autosomal recessive inheritance. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2012;20:1024–1031. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rock R, Schrauth S, Gessler M. Expression of mouse dchs1, fjx1, and fat-j suggests conservation of the planar cell polarity pathway identified in Drosophila. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:747–755. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.