Abstract

The need to rapidly improve health care value is unquestioned, but the means to accomplish this task is unknown. Improving performance at the level of the health care organization frequently involves multiple interventions, which must be coordinated and sequenced to fit the specific context. Those responsible for achieving large-scale improvements are challenged by the lack of a framework to describe and organize improvement strategies. Drawing from the fields of health services, industrial engineering, and organizational behavior, a simple framework was developed and has been used to guide and evaluate improvement initiatives at an academic health center. The authors anticipate that this framework will be helpful for health system leaders responsible for improving health care quality.

Keywords: Quality improvement, academic medical center, quality management framework

Introduction

The need to rapidly improve value in American health care has been unquestioned, but the means to accomplish this task have yet to be confirmed. Achieving improvements at the organizational level has required the design and implementation of complex, multifaceted, and coordinated interventions. It has been a frustratingly slow process. Achieving excellent performance across all clinical services at a single institution has eluded even the most elite performers.1,2 Furthermore, dissemination of evidence-based interventions has been the subject of debate and consternation,3 and developing an understanding of this area has been identified as an emerging national research priority.4 To assist quality improvement leaders with these tasks, a standard framework or model to guide system wide improvement would be a valuable tool to organize interventions, evaluate factors contributing to success or failure, and share knowledge in a structured format.

Conceptual models or frameworks are used to clarify, describe, and organize ideas.5,6 Although several models of health system change exist, these models lacked practical utility and failed to provide a framework for mapping strategies for both what needs to change and how change will occur. Simple models of change, although easy to remember,7,8 have lacked the necessary specificity to guide complex multidimensional interventions. In contrast, models with greater specificity have often been complicated and sacrificed utility in pursuit of greater detail and information.9–11 Additionally, although other health systems have described their specific constructs for system-level improvement, these examples are limited to the acute care setting12,13 or to well-organized14 or integrated15–17 delivery systems.

This article describes the development and use of a practical framework to guide system-level improvement. This framework is theoretically grounded in research from industrial and systems engineering, organizational behavior, and health system redesign18–22 and is potentially applicable across less-organized delivery systems. The UW Health system has embarked on several large-scale, enterprise-wide improvement initiatives. UW Health recognized the need to develop a new evidence-based model for guiding change that achieved a middle ground between ease of use and including enough detail to inform project plans. At UW Health, this framework has been useful in organizing improvement efforts, guiding large-scale system redesign, understanding causes of improvement failures, and standardizing the organization of improvement interventions to facilitate communication and project evaluation. This framework is presented as a potential tool for use by those responsible for the design and implementation of large-scale improvement efforts.

Description of the Health System

UW Health is the academic health center for UW–Madison and serves as a statewide and national leader in patient care, biomedical research and education, and service to communities. This public academic health system comprises 3 organizations: a school of medicine and public health, a tertiary hospital and its associated clinics, and a physician group practice.

The Need for an Improvement Framework

The complexity of this tripartite organizational structure had a direct impact on the ability to design and implement improvements at the enterprise level. In 2007, the UW Health system had 3 separate quality improvement departments resourced by each of the 3 organizations. Each department used a variety of improvement tools and methodologies. The lack of a standard approach to understanding and implementing improvements contributed to the slow progression toward UW Health improvement goals. This was particularly problematic when attempting to redesign care processes in UW Health primary care clinics, which were owned and operated by the 3 separate organizations of UW Health.

UW Health primary care was delivered through 30 clinics in Dane County, which includes the city of Madison, and an additional 10 clinics in surrounding counties. These clinics were owned and operated by each of the 3 UW Health organizations. This resulted in each primary care specialty (family medicine, general internal medicine, and general pediatric and adolescent medicine) having clinics operating under different management systems with different governances, operational structures, and clinic processes and technology. For example, family medicine physicians (all members of the Department of Family Medicine in the School of Medicine and Public Health) might work at a clinic that was owned and operated by the Department of Family Medicine or a clinic owned and operated by the physician group practice. Operational differences and the lack of a common strategy for large-scale improvement was a major barrier as primary care redesign efforts were initiated. This has been an increasingly common problem nationwide in this era of health system integration and mergers between physician practice groups.

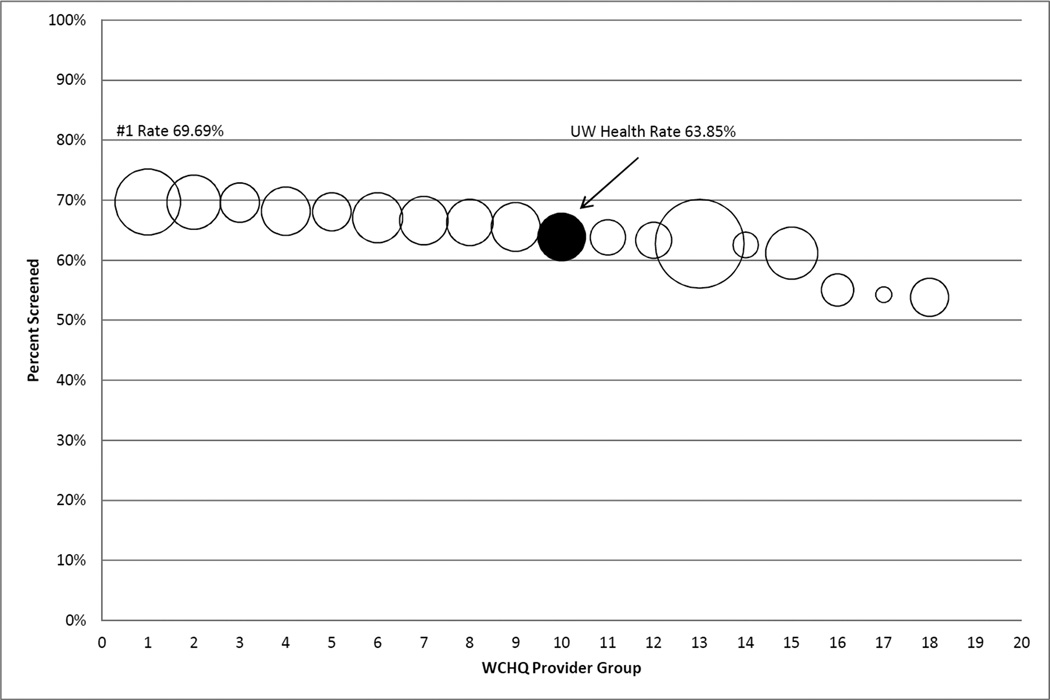

In 2007, UW Health performance data for primary care services (preventive screening, routine chronic care process, and intermediary outcome measures) indicated poor performance compared with other provider groups in Wisconsin, as reported to the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ; a consortium of Wisconsin provider groups voluntarily publicly reporting health quality performance on a wide range of measures).23 Variation in performance was identified between UW Health primary care clinics and between providers at a single clinic (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Variation in colorectal cancer screening performance in 2007 between UW Health primary care clinics and physicians practicing at those clinics.

Black bubbles indicate average clinic performance for colorectal cancer screening (denominator is the population of patients who are included in the WCHQ denominator definition for this test and are included on the panel for a primary care physician practicing at that clinic). White bubbles indicate individual physician performance related to colorectal cancer screening for those patients on the physician’s panel and included in the WCHQ denominator definition. The size of the white bubble corresponds to the number of patients on the physician’s panel who are eligible for colorectal cancer screening. Providers with fewer than 30 patients in the denominator were excluded from these analyses.

Abbreviations: WCHQ, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality

Clinic-level variation existed both between primary care specialties (eg, general internal medicine and family medicine) and between clinics with different ownership and management structures. UW Health recognized that variation attributed to clinic operations or primary care specialties would require a different set of improvement interventions as compared with those used to reduce the variation between physicians at a single clinic.

Description of the Improvement Framework

The need to understand the contributing factors to variable performance and organize multilevel interventions pressed UW Health to develop a standardized framework for improvement. As described in the Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm report,19 4 levels of the health system must be addressed to achieve change: the environment, organization, microsystem, and patients and their caregivers. UW Health data confirmed significant variation at each level of the health system, which supported this assertion. Once the levels of the health system were defined, a literature review was conducted to identify the critical domains of change required at each level, answering the question of “what” needed to be done at each level to effect large-scale, sustained change. Findings from organizational behavior and industrial and systems engineering (in particular, human factors engineering) provided insights into the major categories for change at each level.5,18,20–22

Building from the structure-process-outcome model described by Donabedian, the framework provided more specificity related to what structures and processes were critical to success.18,20 Shortell et al24 described 4 dimensions of change that support sustained, organization-level improvements: strategic, cultural, technical, and structural. He emphasized that all dimensions must be aligned to achieve large-scale change. The strategic dimension addresses the importance of aligning improvement work with critical strategic foci. The norms, values, and beliefs of participants will determine the culture in which the improvement work occurs. Technology has assumed a greater influence in health care redesign as electronic health care records (EHRs) become the norm, and activities of daily living become increasingly intertwined with new devices. The structural dimension refers to the infrastructure in place that enables the system to “learn” to adopt new practices, spread best practices, and continuously measure performance and improve processes.

Missing from these 4 dimensions was the importance of the people doing the work and the relationships between workers and the environment. Human factors science provides important insights into how the interactions between the components of the work system (people, tasks, tools and technologies, organizational conditions, and physical environment) affect care processes and the outcomes of the system.20,25–27 In particular, human factors science aims to optimize well-being along with system performance28 to decrease potential negative consequences of change such as stress and burnout.29 Therefore, the recognition that people, work flow, and care processes are important dimensions of change also was included in the model.

By combining the levels of the health system and the critical structures and processes for sustained improvement, a framework was developed that is easy to remember and practical to use (Table 1). The work improving UW Health performance in colorectal cancer screening serves as a case study demonstrating how this framework was used by the organization for large-scale quality improvement.

Table 1.

UW Health Improvement Framework

| Health System Level |

Change Domain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals and Strategies (incentives, priorities, opportunities for change) |

Culture (values, beliefs, norms) |

Structure of Learning (infrastructure to support continuous learning and improvement) |

People, Workflow and Care Processes (role optimization, processes of care, standard workflows) |

Technology (information services, electronic health records) |

|

| Patients and Caregivers | |||||

| Microsystems (small units where care is delivered) | |||||

| Organizations (supporting microsystems) | |||||

| Environment (policy, payment, regulation) | |||||

Case Study: UW Health Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative

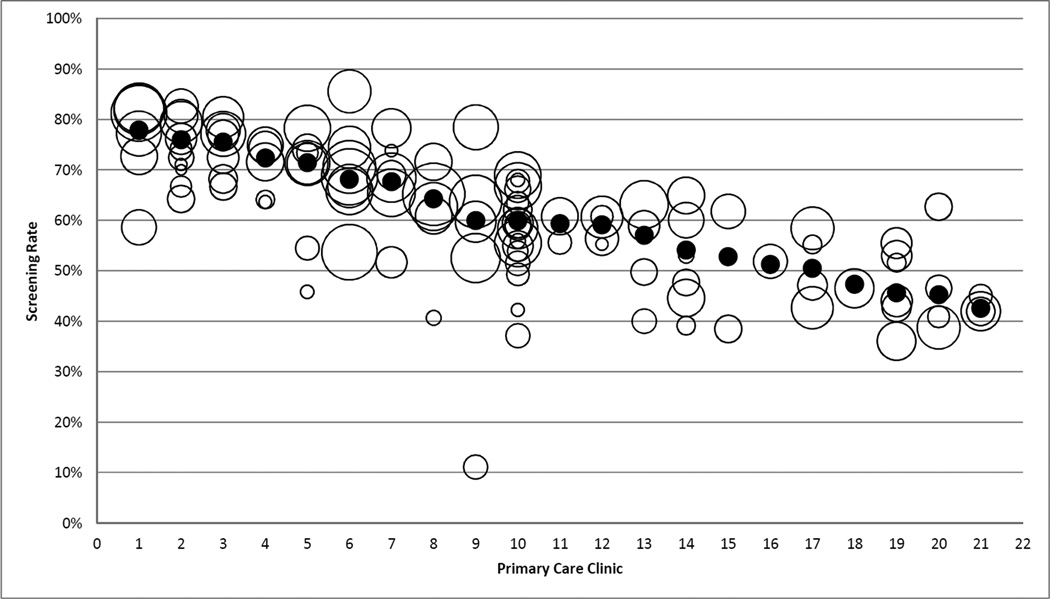

In 2007, UW Health colorectal cancer screening performance was ranked 11 out of 20 provider groups reporting to the WCHQ23 (Figure 2). Provider groups reporting to the WCHQ use a common set of measure specifications. Patients were attributed to a provider group using the WCHQ denominator methodology, which used primary care visits to determine whether a patient was currently managed by a provider group. Patients eligible for colorectal cancer screening included those aged 50 to 75 years. Screening can be completed by multiple methods, including (a) fecal occult blood test in the prior 12 months; (b) flexible sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema, or computed tomographic (CT) colonography in the past 5 years; or (c) optical colonoscopy in the prior 10 years.

Figure 2. 2007 colorectal cancer screening rates among WCHQ provider groups: Black bubble indicates UW Health performance.

White bubbles are the other provider groups reporting to WCHQ. Size of the bubbles corresponds to the size of the denominator (number of patients eligible for screening at each organization). These data were measured from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2007.

Abbreviations: WCHQ, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality.

In response to these variations the UW Health quality improvement department embarked on a multiyear initiative to improve performance in colorectal cancer screening. A multidisciplinary team was involved in this work, consisting of physicians (gastroenterologists, radiologists, and primary care), clinical and information technology (IT) staff, operational leaders, and representatives from local insurance companies. The UW Health Improvement Framework provided a guide to understanding performance at the various levels of the health system and served as a means to organize the portfolio of interventions.

Robust project management was a critical success factor for this complex system redesign. A master’s-prepared industrial engineer supported this work, providing project management and expertise on process improvement. A steering committee, which met every 3 to 4 months, established the vision and guiding principles and determined high-level strategies, and a planning team met monthly to design interventions, support process improvements implemented in clinics, and continuously review performance in order to iteratively adjust interventions based on data analysis. The planning team coordinated interventions across all 3 UW Health organizational entities, departments (such as gastroenterology, radiology, primary care, operations, laboratory services, IT, and patient education), and external partners (such as insurers and other local health systems where procedures were performed). The UW Health Framework provided a usable schematic for communicating project activities with stakeholders.

Improvement work took place over several years and interventions had to be sequenced appropriately. Understanding interdependencies between the levels of the health system uncovered critical constraints in the system that informed the project time line. At the project initiation, the demand for colonoscopies far exceeded existing supply. Given this constraint, initial work focused on redesign of the entire process from colonoscopy order to results reporting, across 3 separate sites where procedures were performed. In addition to optical colonoscopies, early efforts were directed to improvements in CT colonography and stool testing processes. Improving system capacity required changes in work flows, the EHR, education of staff and physicians, procedure templates, and policies. Even changes in purchasing and billing were required when changing to a new immunoassay stool test. Only after system capacity for testing was increased were efforts refocused on increasing the demand for screening. Attention to the system as a whole and the interdependencies between the levels of the system informed the project time line. Table 2 shows the completed framework for this initiative. Interventions are further described below according to the 4 health system levels.

Table 2.

UW Health Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative

| Heath System Level | Change Domain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals and Strategies (incentives, priorities, opportunities for change) |

Culture (values, beliefs, norms) |

Structure of Learning (infrastructure to support continuous learning and improvement) |

People, Workflow and Care Processes (role optimization, processes of care, standard workflows) |

Technology (information services, electronic health records) |

|

| Patients and Caregivers | Engage patients through focus groups to understand patient goals and health promotion behaviors | Revised patient education materials | New web site for patients | Reminders in the EHR patient portal | |

| Microsystems (small units where care is delivered) | Pay-for-performance, transparent MD- and clinic-level reports | Education for all members of the care team | Toolkit, lunch-and-learn sessions, web-based learning and training | Workflows using clinical decision support tools, facilitated ordering, clinic outreach | EHR reminders, easy ordering |

| Organizations (supporting microsystems) | UW Health strategic priority, UW Health Pay-for-Performance | Survey of physicians used to understand barriers | Presentation at department meetings, quality council, Board meetings | Redesigned scheduling processes, standardized colonoscopy reporting | EHR reminders, change to immunoassay fecal occult blood test |

| Environment (policy, payment, regulation) | Pay-for-performance with local insurers | Community colorectal screening awareness month | Insurers use UW Health patient education materials | Change in formulary to cover low volume bowel prep | |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record

Patient education materials on colorectal cancer screening were updated based on input from patient and family advisory councils and a patient focus group. UW Health created standardized printed materials and developed a new page on the UW Health website for patients and families to provide information on the importance of colorectal cancer screening and the various screening modalities. Finally, patient reminders for screening were delivered through the EHR patient portal.

Interventions at the Microsystem and Clinic Level

Interventions at this level were supported by the organizational interventions described in the next section. Clinic care teams and individual physicians were financially incentivized to improve colorectal cancer screening rates. Increased transparency in performance reporting created additional incentives. Opportunities to learn more about colorectal cancer screening (described in the following section) were made available to all care team members. New functionality in the EHR that alerted users that colorectal cancer screening was due, combined with new work flows (including outreach phone calls to overdue patients), additionally facilitated clinic-based improvement efforts. All these interventions anecdotally led to heightened clinic awareness about quality measurement, the patient experience of care, and the need to improve.

Interventions at the Organizational Level

In response to the need to focus on change at the organizational level, a multidisciplinary planning group of UW Health leaders met regularly. This UW Health team included physicians, clinical staff, and operational leaders, and reported to the larger steering committee, which included additional health system representatives and local insurers. Colorectal cancer screening was designated as an organizational improvement priority that resulted in the publication of performance rates and goals on the enterprise-wide improvement scorecard. Physician- and clinic-level performance rates were made available to all physicians and managers at UW Health through reports readily available in the EHR. Multiple learning activities were provided, including grand rounds presentations, clinic “lunch-and-learn” events, and web-based education modules. The declaration by UW Health leaders that improving colorectal cancer screening was an organizational priority led to a multitude of changes, from equipment overhauls to EHR redesign. Ordering and scheduling processes for colonoscopies were redesigned and superior immunoassay testing for occult blood was made available for providers who continued to use stool testing for screening. Clinical decision support tools were embedded in the EHR to identify patients who needed screening and to facilitate ordering.

Interventions at the Environmental Level

Working with local payers, UW Health leaders designed interventions at the environmental level to improve performance. Local insurers participated in a pay-for-performance program collaboratively designed by UW Health physicians and insurance representatives. This program paid bonuses to clinics and physicians for improvements in colorectal cancer screening rates. Additionally, in response to patient and physician input, one insurance company changed its formulary to cover a low-volume bowel preparation. UW Health also promoted community events to increase awareness about colorectal cancer screening.

Initiative Outcomes

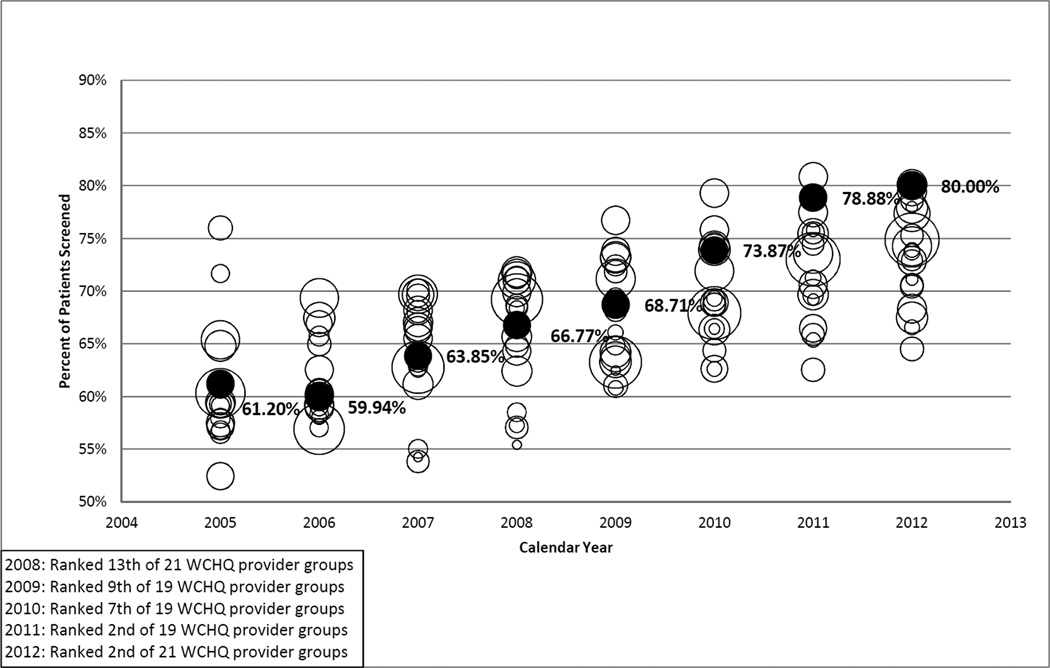

The deliberate design of multilevel and multidimensional interventions led to improvements in absolute performance and in relative performance in the state, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Variation between UW Health and other provider groups reporting to the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality in colorectal cancer screening.

Bubble size corresponds to the size of the denominator (the number of patients at each organization who are eligible for this screening). Black bubbles indicate UW Health performance. White bubbles indicate other providing groups reporting to the WCHQ. UW Health eligible patient population by year: 2008, n = 3,647; 2009, n = 39,454; 2010, n = 38,848; 2011, n = 40,129; 2012, n = 41,857.

Abbreviations: UW, University of Wisconsin; WCHQ, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality

UW Health recognizes that gains in performance by underperforming groups are always greater than gains by better performers. However, improvements have been sustained even after the formal improvement effort ended, supporting the UW experience that a systematic understanding and redesign of interrelated components supports sustainable improvements.

This project was one of the first attempts to standardize and improve processes across the complex primary care delivery system at UW Health. It required complicated negotiations between the 3 separate entities related to differences in policies, procedures, regulatory constraints, and technology platforms. The UW Health Improvement Framework has continued to help organize interventions and has facilitated communication among multiple stakeholders in the system.

Common to all academic medical centers is the inherent competition for physician time as faculty responded to the tripartite mission of clinical care, research, and education. This project focused on improving clinical care, but also supported the organization’s academic and research missions; as several faculty members have shared these findings through presentations and publications.30–32 Additionally, further research to understand and address causes of performance variation is under way. Finally, a regional collaborative engaged one of the UW Health gastroenterologist improvement leaders for guidance on an ambitious statewide effort to increase colorectal cancer screening.

Discussion

This article presents a simple, evidence-based framework for large-scale change that has been used to successfully guide system-based improvements in a complex health care organization. The need for such a model has been evidenced by the slow emergence of transformative improvements and the frustratingly protracted pace of dissemination. Even in a single health system, such as UW Health, successful improvements can frequently remain in silos, and the lack of a common framework for organizing multifaceted improvements can create a “swirl” of activity without producing systemic results. Other health systems may benefit from this framework to approach system-level change and efficiently transfer innovations into practice.5

This framework extends the usefulness of other models by explicitly identifying the categories of contextual, structural, and process-related changes that need to be in place at each level of the health system. This framework is a “static” description of the domains of change and the levels of the health system; and unlike other models, it does not describe the sequence to accomplish change.8–10 In the UW Health experience, the sequencing of interventions often was dictated by constraints in the existing system and may vary depending on the level of the health system involved in the change. As an example from the case presented, our initial constraint in expanding colonoscopy services was the number of appointments available for these scheduled procedures. The capacity of the system had to be improved before interventions could be implemented that would lead to increased colonoscopy orders.

System wide change requires coordination of multiple interventions, many of which are interdependent. This framework created a visual and organized representation of those interventions and helped identify how change at one level facilitated or impeded required change at other levels. This multilevel and multidimensional framework fits with the recent recommendation by the Institute of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering to adopt a systems approach to health.33

Developed in response to the challenges with large-scale improvement in a single health system, this framework has been valuable at UW Health but has not been tested at other institutions. Given the persistent complexity of clinic ownership and management in UW’s “single” health system (40 primary care clinics owned and managed by 3 separate legal entities), it is hypothesized that this framework will be useful for organizing interventions at a single site or in complex organizational structures.

This case study describes how the framework was adopted for large-scale changes related to a preventive service in the ambulatory care delivery system, but this framework is also relevant for other initiatives including chronic disease, inpatient, and transitional care improvement efforts. Over the past 4 years, this framework has organized and guided improvements related to diabetes care at UW Health (with measurable improvements in WCHQ performance) and is currently used by the team designing models of care for additional chronic diseases. This framework was recently used for planning and implementing a complex case management program.

In addition to being used proactively to guide initiatives, the framework is a useful tool to understand potential failures of implementation through systematic review of the work completed in each cell in the table in order to identify where important lapses may exist. Large-scale change may not require an intervention at every level of the system and in every domain of change, but the framework provides an easy tool to identify where there has been a lack of focused improvement work, resulting in the discovery of a potential barrier to change. Finally, this framework facilitates communication through providing a visual map describing the multiple interventions that organizations undertake as part of redesigning a system. The authors hypothesize and anticipate that this framework will be applicable in many settings because the theories and models that inform the framework were developed by researchers to address dissemination challenges in the general health care environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Primary care Academics Transforming Healthcare (PATH) Writing Collaborative for their support and Zaher Karp for his editorial assistance.

Funding Sources

This project was supported by the Health Innovation Program, the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, Wisconsin Partnership Program, and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR) through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. In addition, Nancy Pandhi is supported by a National Institute on Aging Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award, grant number lK08AG029527, and Jennifer Weiss is supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research, MRSG-13-144-01-CPHPS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Rosenthal MB, Fernandopulle R, Song HR, Landon B. Paying for quality: providers’ incentives for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:127–141. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha AK, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Care in U.S. hospitals: the Hospital Quality Alliance program. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:265–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969–1975. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasgow RE, Chambers D. Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clin Transl Sci. 2012;5:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shojania K, Ranji S, Shaw L, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Care Coordination. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies; vol 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolan TW. Execution of Strategic Improvement Initiatives to Produce System-Level Results. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 1995 Mar-Apr;:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knapp H, Anaya HD. Implementation science in the real world: a streamlined model. J Healthc Qual. 2012;34:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2012.00220.x. quiz 34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perla RJ, Bradbury E, Gunther-Murphy C. Large-scale improvement initiatives in healthcare: a scan of the literature. J Healthc Qual. 2013;35:30–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang MC, Hyun JK, Harrison M, Shortell SM, Fraser I. Redesigning health systems for quality: lessons from emerging practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendrich A, Tersigni AR, Jeffcoat S, Barnett CJ, Brideau LP, Pryor D. The Ascension Health journey to zero: lessons learned and leadership. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:739–749. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pryor D, Hendrich A, Henkel RJ, Beckmann JK, Tersigni AR. The quality “journey” at Ascension Health: how we’ve prevented at least 1,500 avoidable deaths a year—and aim to do even better. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:604–611. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James BC, Savitz LA. How Intermountain trimmed health care costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1185–1191. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy DM, Caselli RJ, Berry LL. A roadmap for improving healthcare service quality. J Healthc Manag. 2011;56:385–400. discussion 400–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swensen SJ, Dilling JA, Harper CM, Jr, Noseworthy JH. The Mayo Clinic value creation system. Am J Med Qual. 2012;27:58–65. doi: 10.1177/1062860611410966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swensen SJ, Dilling JA, Milliner DS, et al. Quality: the Mayo Clinic approach. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:428–440. doi: 10.1177/1062860609339521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD. Organization theory and health services management. In: Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD, editors. Health Care Management: Organization Design and Behavior. 4th ed. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar; 1994. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; p. xx.p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(suppl 1):i50–i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donabedian A. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring; vol 1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisconsin Collaborative for Healhcare Quality. [Accessed October 29, 2013]; http://www.wchq.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76:593–624. 510. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carayon P. Human factors in patient safety as an innovation. Appl Ergon. 2010;41:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, et al. Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Appl Ergon. 2014;45:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurses AP, Ozok AA, Pronovost PJ. Time to accelerate integration of human factors and ergonomics in patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:347–351. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dul J, Bruder R, Buckle P, et al. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics. 2012;55:377–395. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2012.661087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carayon P, Karsh B-T, Gurses AP, et al. Macroergonomics in health care quality and patient safety. Rev Hum Factors Ergon. 2013;8:4–54. doi: 10.1177/1557234X13492976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss J, Kraft S, Flood G, et al. Variation in colorectal cancer screening within a unified health system. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5) suppl 1:S151. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss JM, Pfau P, Kraft S, Pickhardt PJ, Smith MA. Barrier analysis to colorectal cancer screening for primary care providers. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):S-774. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss JS, Smith MA, Pickhardt P, et al. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening variation among primary-care providers and clinics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1159–1167. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan GS, Bo-Linn G, Carayon P, et al. Bringing a systems approach to health. [Accessed March 12, 2014]; http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2013/Discussion-Papers/VSRT-SAHIC-Overview.pdf. [Google Scholar]