Abstract

The recent emergence of a novel avian A/H7N9 influenza virus in poultry and humans in China, as well as laboratory studies on adaptation and transmission of avian A/H5N1 influenza viruses, has shed new light on influenza virus adaptation to mammals. One of the biological traits required for animal influenza viruses to cross the species barrier that received considerable attention in animal model studies, in vitro assays, and structural analyses is receptor binding specificity. Sialylated glycans present on the apical surface of host cells can function as receptors for the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) protein. Avian and human influenza viruses typically have a different sialic acid (SA)‐binding preference and only few amino acid changes in the HA protein can cause a switch from avian to human receptor specificity. Recent experiments using glycan arrays, virus histochemistry, animal models, and structural analyses of HA have added a wealth of knowledge on receptor binding specificity. Here, we review recent data on the interaction between influenza virus HA and SA receptors of the host, and the impact on virus host range, pathogenesis, and transmission. Remaining challenges and future research priorities are also discussed.

Keywords: A/H5N1 influenza virus, A/H7N9 influenza virus, airborne transmission, pathogenesis, receptor binding specificity

Subject Categories: Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction

Influenza virus zoonoses and pandemics

Influenza A viruses can infect a wide range of hosts, including humans, birds, pigs, horses, and marine mammals (Webster et al, 1992). Influenza A viruses are classified based on the antigenic properties of the major surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). To date, 18 HA and 11 NA subtypes have been described. All subtypes have been found in wild aquatic birds except for the recently discovered H17N10 and H18N11 viruses, which have only been detected in bats (Webster et al, 1992; Fouchier et al, 2005; Tong et al, 2012, 2013). Throughout recent history, avian‐origin influenza viruses have crossed the species barrier and infected humans. Some of these zoonotic events resulted in the emergence of influenza viruses that acquired the ability to transmit between humans and initiate a pandemic. Four pandemics were recorded in the last century: the 1918 H1N1 Spanish pandemic, the 1957 H2N2 Asian pandemic, the 1968 H3N2 Hong Kong pandemic, and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (pH1N1) that was first detected in Mexico (reviewed in Sorrell et al, 2011). Various other influenza A viruses of pig and avian origin (e.g., of subtypes H5, H6, H7, H9, and H10) have occasionally infected humans—sometimes associated with severe disease and deaths—but these have not become established in humans.

The H5N1 avian influenza virus that was first detected in Hong Kong in 1997 has frequently been reported to infect humans and cause serious disease. As of October 8, 2013, WHO has been informed of 641 human cases of infection with H5N1 viruses, of which 380 died (www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/en/). The majority of these cases occurred upon direct or indirect contact with infected poultry. Due to the high incidence of zoonotic events, the enzootic circulation of the virus in poultry, and the severity of disease in humans, the H5N1 virus is considered to pose a serious pandemic threat. Fortunately, sustained human‐to‐human transmission has not been reported yet (Kandun et al, 2006; Wang et al, 2008).

A more recent example of a major zoonotic influenza A virus outbreak started in China in early 2013. This outbreak, caused by an avian H7N9 virus, resulted in 137 laboratory‐confirmed human cases of infection and 45 deaths (www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/en/). Although one case of possible human‐to‐human transmission was described, thus far, this outbreak also has not lead to sustained transmission between humans (Gao et al, 2013b; Qi et al, 2013). Some mild cases of infection were reported, but the Chinese H7N9 influenza viruses frequently caused severe illness, characterized by severe pulmonary disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Gao et al, 2013a,b). Although influenza viruses of the H7 subtype have sporadically crossed the species barrier in the past, with outbreaks reported, for example, in the United Kingdom, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004), Canada (Tweed et al, 2004), the Netherlands (Fouchier et al, 2004), and Italy (Puzelli et al, 2005; www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/en/), the 2013 H7N9 virus appeared to jump the species barrier more easily and was generally associated with more serious disease in humans. Interestingly, the internal genes of the H7N9 virus belong to the same genetic lineage as the internal genes of the H5N1 virus; both are derived from H9N2 viruses (Guan et al, 1999; Lam et al, 2013). The H7N9 virus is thought to have emerged upon four reassortment events between H9N2 viruses and avian‐origin viruses of subtype H7 and N9 (Lam et al, 2013). The H9N2 virus itself has been shown to have zoonotic potential as well, resulting in relatively mild human infections upon contact with poultry. H9N2 viruses remain enzootic in domestic birds in many countries of the Eastern Hemisphere (Peiris et al, 1999).

For all influenza pandemics of the last century, the animal‐origin viruses acquired the ability to transmit efficiently via aerosols or respiratory droplets (hereafter referred to as “airborne transmission”) between humans (Sorrell et al, 2011). To evaluate airborne transmission in laboratory settings, ferret and guinea pig transmission models were developed, in which cages with uninfected recipient animals are placed adjacent to cages with infected donor animals. The experimental setup was designed to prevent direct contact or fomite transmission, but to allow airflow from the donor to the recipient ferret (Lowen et al, 2006; Maines et al, 2006). Using the ferret transmission model, pandemic and epidemic viruses isolated from humans are generally transmitted efficiently via the airborne route, whereas avian viruses are generally not airborne transmissible (Sorrell et al, 2011; Belser et al, 2013b).

Why some animal influenza viruses frequently infect humans, whereas others do not, and how viruses adapt to become airborne transmissible between mammals have been key questions in influenza virus research over the last decade. Studies on H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 viruses from the 1918, 1957, and 1968 pandemics, respectively, revealed that interaction of HA with virus receptors on host cells was a critical determinant of host adaptation and airborne transmission between ferrets (Tumpey et al, 2007; Pappas et al, 2010; Roberts et al, 2011). Sorrell and colleagues showed that a wild‐type avian H9N2 virus was not airborne transmissible in ferrets, but reassortment with a human H3N2 virus and subsequent adaptation in ferrets yielded an airborne transmissible H9N2 virus, primarily due to changes in the H9N2 HA and NA surface glycoproteins (Sorrell et al, 2009). Several laboratories have studied the transmissibility of avian H5N1 viruses and their potential to become airborne, and four studies recently described airborne transmission of laboratory‐generated H5N1 influenza viruses. Three of these studies—two using ferrets and one using guinea pigs—used H5 reassortant viruses between human pH1N1 or H3N2 viruses and H5N1 virus (Chen et al, 2012; Imai et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2013d). Herfst et al (2012)were the first to show mammalian adaptation of a fully avian H5N1 virus to yield an airborne transmissible virus in ferrets. Although avian H7 influenza viruses are generally not transmitted via the airborne route between ferrets (Belser et al, 2008), H7N9 strains from the Chinese 2013 outbreak were shown to be transmitted via the airborne route without further adaptation, albeit less efficiently as compared to human seasonal and pandemic viruses (Belser et al, 2013a; Richard et al, 2013; Watanabe et al, 2013; Xu et al, 2013; Zhang et al, 2013a; Zhu et al, 2013). No transmission was observed from pigs to ferrets (Zhu et al, 2013).

It has thus become increasingly clear that animal influenza viruses beyond the H1, H2, and H3 subtypes—specifically H5, H7, and H9—can acquire the ability of airborne transmission between mammals. To date, the exact genetic requirements for animal influenza virus to cross the species barrier and establish efficient human‐to‐human transmission remain largely unknown, but receptor binding specificity is clearly one of the key factors.

HA as determinant of receptor binding specificity

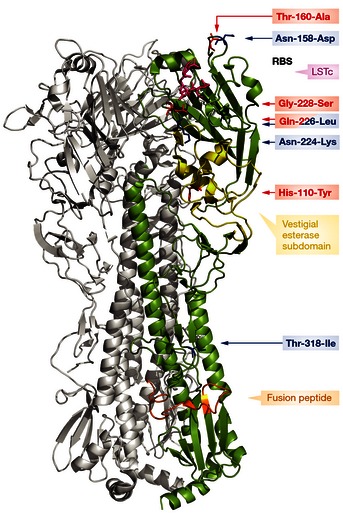

As a first step to entry and infection, influenza viruses attach with the HA protein to sialylated glycan receptors on host cells. The influenza virus HA protein is a type I integral membrane glycoprotein, with a N‐terminal signal sequence. Post‐translational modifications include glycosylation of the HA and acylation of the cytoplasmic tail region. Cleavage of the HA (HA0) by cellular proteases generates the HA1 and HA2 subunits, which form a disulfide bond‐linked complex. The HA protein forms trimers, with each monomer containing a receptor binding site (RBS) capable of engaging a sialylated glycan receptor, a vestigial esterase subdomain, and a fusion subdomain (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Cartoon representation of the hemagglutinin structure of an H5N1 influenza A virus (protein database code 4KDO, representing a mutant version of A/Vietnam/1203/04).

The human receptor analog, LSTc (pink) is docked into the receptor binding site; the vestigial esterase subdomain and fusion peptide are depicted in yellow and orange, respectively. The amino acid substitutions described by Herfst et al are shown in red, and the mutations of Imai et al are shown in blue. Substitution Gln‐226‐Leu was described by both groups (Herfst et al, 2012; Imai et al, 2012).

Hirst (1941) was the first to demonstrate the ability of influenza viruses to agglutinate and elute from red blood cells. Treatment of these cells with Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (VCNA) revealed that the ability to agglutinate and elute was dependent on sialic acid (SA; Gottschalk, 1957). Early comparisons of influenza viruses isolated from different species revealed differences in their abilities to agglutinate red blood cells from various species. Using red blood cells and cells expressing only a certain type of SA, it was discovered that human and animal influenza viruses displayed differences in the receptor specificity of HA (Rogers & Paulson, 1983). Avian influenza viruses were found to have a preference for SA that are linked to the galactose in an α2,3 linkage (α2,3‐SA; Rogers & Paulson, 1983; Nobusawa et al, 1991). In contrast, human influenza viruses (H1, H2, and H3) attached to SA that are linked to galactose in an α2,6 linkage (α2,6‐SA; Gambaryan et al, 1997; Matrosovich et al, 2000). Pig influenza viruses either attached to both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA, or exclusively to α2,6‐SA (Rogers & Paulson, 1983). These gross differences in receptor binding properties were found to be important determinants of virus host range and cell and tissue tropism. A wide range of assays has been developed to assess HA binding specificity and affinity to glycans containing α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA (Paulson et al, 1979; Sauter et al, 1989; Takemoto et al, 1996; Stevens et al, 2006a; Chutinimitkul et al, 2010b; Lin et al, 2012; Matrosovich & Gambaryan, 2012). Binding assays such as glycan arrays, which allow the investigation of hundreds of different sialylated glycan structures, have demonstrated that influenza virus receptor specificity also involves structural modifications of the SA and overall glycan (Gambaryan et al, 2005; Stevens et al, 2006b).

Influenza virus receptors

Types of glycan structures

Mammalian cells are covered by a glycocalyx, which consists of glycolipids, glycoproteins, glycophospholipid anchors and proteoglycans (Varki & Varki, 2007; Varki & Sharon, 2009). Glycans represent one of the fundamental building blocks of life and have essential roles in numerous physiological and pathological processes (reviewed in Hart, 2013). Glycans that are exposed on the exterior surface of cells play an important role in the attachment of toxins and pathogens like influenza A viruses.

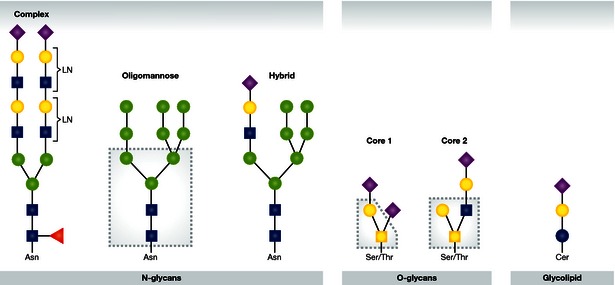

Several types of glycans exist, including N‐glycans, O‐glycans, and glycolipids (reviewed in Brockhausen et al, 2009; Schnaar et al, 2009; Stanley et al, 2009). The N‐glycans can be further divided into different types such as “complex,” “hybrid,” and “oligomannose.” There is a wide variety of O‐glycans, with eight different core structures. Cores 1 and 2 are common structures that are present on glycoproteins (Fig 2). This particular classification of glycan structures is not necessarily relevant for binding of influenza viruses. For O‐glycans and N‐glycans, there is extensive structural diversification at the termini of glycan chains, which is potentially more important than differences in the core structures.

Figure 2. N‐glycans, O‐glycans, and glycolipids.

Examples of three types of N‐glycans are shown; complex with multiple N‐acetyllactosamine repeats (LN), oligomannose, and hybrid (with the common core boxed). A glycolipid and two types of O‐glycans are also shown; core 1 (in box) and core 2 (in box) O‐glycans. Monosaccharides are depicted using the following symbolic representations: fucose (red triangle), galactose (yellow circle), N‐acetyl glucosamine (blue square), N‐acetyl galactosamine (yellow square), glucosamine (blue circle), mannose (green circle), sialic acid (purple diamond).

Receptor‐mediated entry of influenza viruses is reduced in the absence of sialylated N‐glycans (Chu & Whittaker, 2004; de Vries et al, 2012). However, specific roles of sialylated N‐glycans, O‐glycans, and glycolipids for binding and entry of influenza viruses are not fully understood. Mouse cells that are deficient in the production of glycolipids can be infected efficiently with human H3N2 virus, indicating that sialylated glycolipids are not essential for infection (Ichikawa et al, 1994; Ablan et al, 2001). Hamster cells that are deficient in the production of sialylated N‐glycans cannot be efficiently infected with influenza viruses in the presence of serum (Robertson et al, 1978; Chu & Whittaker, 2004). However, when the production of sialylated N‐glycans was restored, H1N1 virus was able to bind and infect these cells (Chu & Whittaker, 2004). Furthermore, it was shown that internalization of influenza via macropinocytic endocytosis is dependent on N‐glycans, but that for clathrin‐mediated endocytosis, N‐glycans are not required (de Vries et al, 2012). It should be noted that most studies are based on in vitro work with human viruses; whether the same principles hold true in vivo and for avian viruses is not known.

Types of sialic acid

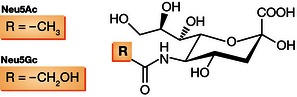

SAs share a nine‐carbon backbone and are among the most diverse sugars found on glycan chains of mammalian cell surfaces. Common SAs found in mammals are N‐acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and N‐glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc; Fig 3; reviewed in Varki & Varki, 2007). Neu5Gc has been detected in pigs, monkeys, and a number of bird species, but humans and some avian species like chickens or other poultry, do not contain Neu5Gc or only minor quantities (Chou et al, 1998; Muchmore et al, 1998; Schauer et al, 2009; Walther et al, 2013).

Figure 3. Structures of Neu5Aca and Neu5Gc.

Lectins Maackia amurensis agglutinin (MAA) and Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) recognize α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA, respectively, and are often used to study the distribution and expression of influenza virus receptors in tissues and cells. There are two different isotypes of MAA: MAA‐1 (also known as MAL or MAM) and MAA‐2 (also known as MAH). MAA‐1 binds primarily to SAα2,3Galβ1‐4GlcNAc that is found in N‐glycans and O‐glycans. MAA‐2 preferentially binds to SAα2,3Galβ1‐3GalNAc, which is found in O‐glycans. Unfortunately, both MAA‐1 and MAA‐2 also bind strongly to sulfated glycan structures without SA. The exact specificities of MAA‐1 and MAA‐2 are reviewed comprehensively by Geisler and Jarvis (2011). To determine which glycan structures present α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA, MAA and SNA can be used in combination with the lectins Concanavalin and Jacalin to detect N‐glycan and O‐glycan structures, respectively. Unfortunately, lectin staining provides little information on the differences in overall glycan structures, including the number of “antennas”, fucosylation, and the presence of N‐acetyllactosamine repeats, all of which can influence influenza virus receptor binding. This encouraged scientists to elucidate the glycome of the respiratory tissue of several influenza virus host species.

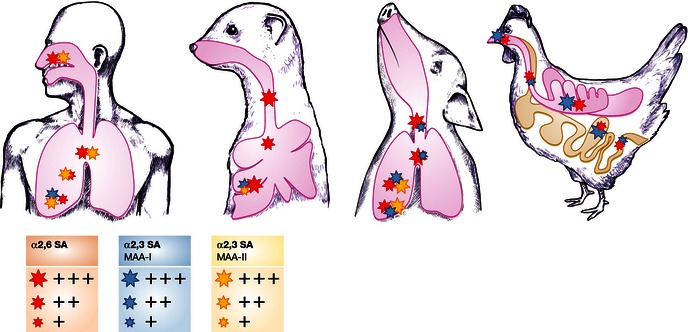

SA receptor distribution in humans, pigs, birds, and ferrets

In humans, α2,6‐SAs are expressed more abundantly in the upper respiratory tract compared to the lower respiratory tract (Fig 4). In the nasopharynx of humans, α2,6‐SA and α2,3‐SA are detected on ciliated cells as well as mucus‐producing cells. In the bronchus, α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA are heterogeneously distributed in the epithelium with no clear distinction between ciliated and non‐ciliated cells. Bronchial epithelium contained a higher percentage of α2,3‐SA compared to α2,6‐SA (Nicholls et al, 2007a). Staining for α2,3‐SA (MAA‐II) was most abundant in cells lining the alveoli, most likely type II cells (Shinya et al, 2006; Nicholls et al, 2007a). The respiratory tract of young children expresses more α2,3‐SA and a lower level of α2,6‐SA compared to adults (Nicholls et al, 2007a).

Figure 4.

Overall distribution of α2,6‐sialic acid (SA; red stars) and α2,3‐SA based on Maackia amurensis agglutinin (MAA)‐I (blue stars) and MAA‐II staining (yellow stars) in the epithelium of the respiratory tract (nasal cavity, trachea, bronchus, bronchiole, and alveoli) of humans (Nicholls et al, 2007a), ferrets (Xu et al, 2010a), pigs (Nelli et al, 2010), and chicken, and the small and large intestine of chickens (Costa et al, 2012). The size of the star shape corresponds with the relative receptor abundance. Receptor distribution may vary between studies, possibly due to the lectins used, experimental methods, or real variation in receptor distribution between animals. Lectin staining was not performed for the human trachea, nasal cavity of pigs and nasal cavity and bronchioles of ferrets in the cited studies. No MAA‐I staining was performed for the chicken tissues. Figure based on Herfst et al, 2012.

To identify the structures of sialylated glycans present in the human respiratory tract, glycomic analysis of human bronchus, lung, and nasopharynx was performed (Walther et al, 2013). Heterogeneous mixtures of bi‐, tri‐, and tetra‐antennary N‐glycans with varying numbers of N‐acetyllactosamine repeats were detected, as well as significant levels of core fucosylated structures and high mannose structures. Compared to the glycan composition of the bronchus and lung, the nasopharynx displayed a smaller spectrum of glycans, with fewer N‐acetyllactosamine repeats. Both α2,6‐SA and α2,3‐SA receptors were detected, but with a higher percentage of α2,3‐SA receptors in the bronchus compared to the lungs. Sialylated core‐1 and core‐2 O‐glycans were present.

The glycan composition of the human respiratory tract was also compared with the glycans present on available glycan arrays (Table 1). The O‐glycan composition of the human respiratory tract was represented well on glycan arrays, but the complex N‐glycan structures were underrepresented. On the other hand, a large number of glycans that are present on the array were not detected in the human respiratory tract and can therefore be largely ignored when studying human influenza virus receptor specificity.

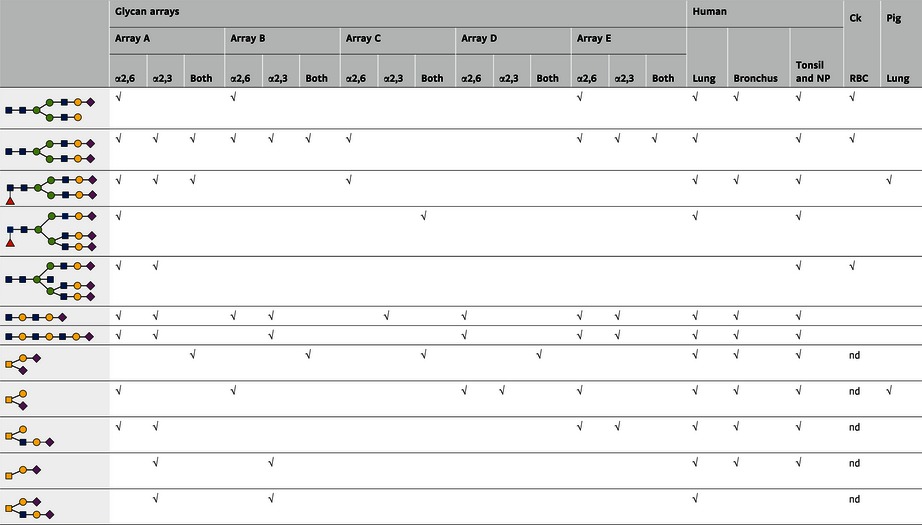

Table 1.

Glycan structures of the human respiratory tract that are represented on glycan arrays (adapted from Walther et al, 2013)

Glycan structures isolated from tissues of the human respiratory tract (nasopharynx, bronchus, and lungs) were compared with glycans printed on the glycan arrays of the consortium of functional glycomics (version 5) (A), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (B), (C) Childs et al (2009), Wong et al (D; Zhang et al, 2008) and (E) de Vries et al (2014). The √ symbol in each column indicates that the glycan is present on the respective array or tissue. Glycan structures detected in the pig lung (Chan et al, 2013b), and chicken (Ck) red blood cells (Aich et al, 2011), that were both present in the human respiratory tract and represented by one or multiple arrays were included.

Pigs are often regarded as a potential “mixing vessel” of human and avian influenza viruses, because pigs express both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA in the respiratory tract (Scholtissek, 1990; Ito et al, 1998; Nelli et al, 2010; Van Poucke et al, 2010; Fig 4). Given the recent data on SA presence in the human respiratory tract (see above), this role as a mixing vessel may not be unique to pigs. The α2,6‐SA receptors were dominant in the ciliated epithelia along the upper respiratory lining of the trachea and bronchus. There was a gradual increase in α2,3‐SA receptors toward the lower respiratory lining. The mucosa of the respiratory tract predominantly contained α2,3‐SA, with α2,6‐SA mainly confined to mucous/serous glands. The α2,3‐SA receptors were more highly expressed in the epithelial lining of the lower respiratory tract (bronchioles and alveoli; Nelli et al, 2010).

Primary pig respiratory epithelial cells, trachea, and lung tissue were described to contain high mannose structures and complex glycans with core fucosylated bi‐, tri‐, and tetra‐antennary structures. In the pig respiratory epithelial cells, structures bearing N‐acetyllactosamine repeats were expressed, but there was a relative lack of these structures in pig trachea and lung tissue (Table 1). Both Neu5Gc and Neu5Ac were present, with a higher abundance of the latter (Bateman et al, 2010; Sriwilaijaroen et al, 2011; Chan et al, 2013b). Pig lung contains both core 1 and core 2 O‐glycan structures. For N‐glycans, there was a higher abundance of α2,6‐SA in the lungs and trachea compared to α2,3‐SA (Chan et al, 2013b). The pig respiratory tract presents a smaller diversity of sialylated N‐glycan structures compared to the glycome of the human respiratory tract (Sriwilaijaroen et al, 2011; Walther et al, 2013).

Avian species have α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA in both the respiratory and intestinal tract, although there are differences in the abundance of these receptors between different species (Franca et al, 2013). Chickens and common quails express α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA on a large range of different epithelial cells in the respiratory tract and intestine (Nelli et al, 2010; Trebbien et al, 2011; Costa et al, 2012; Fig 4). There is conflicting data for the presence of α2,6‐SA in the intestine of mallards: Some groups found expression of α2,6‐SA, whereas others did not (Kuchipudi et al, 2009; Costa et al, 2012; Franca et al, 2013).

Chicken red blood cells are frequently used for influenza virus agglutination assays. Analysis of its glycome revealed that chicken red blood cells present a plethora of N‐glycans, both di‐, tri‐, and tetra‐antennary glycan structures with a mixture of α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SAs, but compared to the glycome of the human respiratory tract, an absence of repeating N‐acetyllactosamine units was observed (Table 1).

Ferrets are widely used as an animal model for influenza virus infections because they have a similar distribution of α2,6‐SA and α2,3‐SAs throughout the respiratory tract as humans (Leigh et al, 1995; Kirkeby et al, 2009). In the ferret trachea and bronchus, α2,6‐SA was abundantly expressed by ciliated cells and submucosal glands (Fig 4). The presence of α2,3‐SA was detected in the lamina propria and submucosal areas, but not on ciliated cells. Alveoli expressed both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA although staining for the latter was more abundant (Jayaraman et al, 2012).

Structural determinants of receptor specificity

In 1981, the first crystal structure of influenza A virus HA was described by Wilson et al (1981). These and other structural studies showed that HA is expressed as a trimer, with a site for SA binding in the membrane‐distal tip of each of the monomers. Each site comprises a pocket of conserved amino acids that is edged by the 190‐helix, the 130‐loop, and the 220‐loop (Fig 5A). A set of conserved residues, 98‐Tyr, 153‐Trp, 183‐His, and 195‐Tyr (numbering throughout the manuscript is based on H3 HA), forms the base of the RBS (Skehel & Wiley, 2000; Ha et al, 2001). Although sequence differences in the 190‐helix, the 130‐loop, and the 220‐loop exist between viruses of different subtypes and from different hosts (Fig 5B), the conformation of each of these elements is similar. Structural studies have demonstrated that the RBS of human and pig influenza viruses that bind α2,6‐SA is “wider” than the RBS of avian influenza viruses (Ha et al, 2001; Stevens et al, 2004).

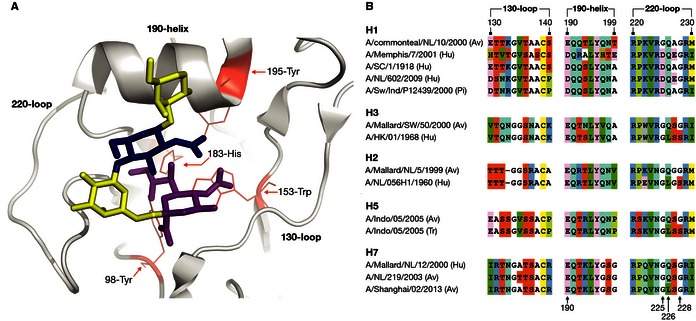

Figure 5.

Cartoon representation of a human influenza hemagglutinin (database code 2YP4) receptor binding site with the 130‐loop, 190‐helix, and 220‐loop and the conserved residues, 98‐Tyr, 153‐Trp, 183‐His, and 195‐Tyr in complex with the human receptor analog LSTc in cis conformation (A). Amino acid alignment of the 130‐loop, 190‐helix, and 220‐loop of human (Hu), avian (Av), pig (Pi) influenza viruses, and an airborne transmissible H5N1 virus (Tr) (B). The sequences are derived from the following virus strains: A/Teal/NL/10/2000 (CY060178), A/Memphis/7/2001 (CY020149), A/SC/1/1918 (F116575), A/Mallard/SW/50/2000 (CY060308), A/HK/01/1968 (CY112249), A/Mallard/NL/5/1999 (CY064950), A/NL/056H1/1960 (CY077786), A/Indo/5/2005 (CY116646), airborne transmissible A/Indo/05/2005 (CY116686), A/Mallard/12/2000 (GU053030), A/NL/219/2003 (AY338459) and A/Shanghai/02/2013 (KF021597).

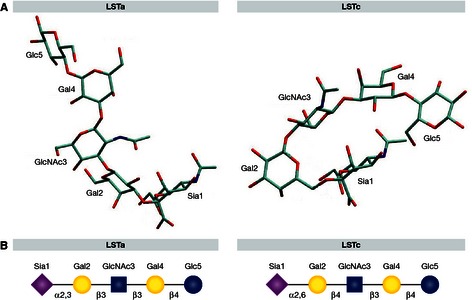

To study interactions of HA with receptors, HAs are crystallized and soaked in human or avian receptor analogs. Commonly, linear sialylated pentasaccharides LSTc (α2,6‐SA) and LSTa (α2,3‐SA) are used as human and avian receptor analogs, respectively (Fig 6). Among the major difficulties of structural studies are the flexible nature of both the HA protein and the glycan structure, which is largely undetectable in crystallography, and the lack of knowledge of the SA receptors that are relevant for infection in vivo (see above). LSTa in complex with the HA of avian H1, H2, H3, and H5 viruses is usually bound in a trans conformation of the α2,3 linkage. In contrast, LSTc is bound in a cis conformation of the α2,6 linkage by HA of H1, H2, and H3 human influenza viruses (Gamblin & Skehel, 2010; Fig 6A).

Figure 6. Human and avian receptor analogs in free conformation (Figure adapted from Xu et al, 2009).

Avian receptor analog LSTa is shown in trans conformation and the human receptor analog LSTc in cis conformation (A). Symbolic representation of the LSTa and LSTc structures (B), with the monosaccharides sialic acid (purple diamond), galactose (yellow circle), N‐acetylglucosamine (blue square) and glucose (blue circle).

HA of pandemic influenza viruses

The H2N2 and H3N2 pandemics were caused by viruses containing HAs of avian origin (Scholtissek et al, 1978; Kawaoka et al, 1989). Two mutations, Gln‐226‐Leu and Gly‐228‐Ser in the RBS, were sufficient for avian H2 and H3 viruses to switch from α2,3‐SA to α2,6‐SA specificity (Connor et al, 1994; Matrosovich et al, 2000; Fig 5B). The Leu at position 226 caused a shift of the 220‐loop, resulting in a widening of the RBS, favorable binding to the human receptor, and abolished binding to the avian receptor (Liu et al, 2009; Xu et al, 2010b). This shift and the widening of the RBS were maximal if both 226‐Leu and 228‐Ser were present. In contrast to human H2 and H3, the HAs of human H1N1 viruses retained 226‐Gln and 228‐Gly, but bound α2,6‐SA nevertheless (Rogers & D'Souza, 1989). The α2,6‐SA preference of human H1N1 virus was found to be determined primarily by 190‐Asp and 225‐Asp (Matrosovich et al, 2000; Glaser et al, 2005). Structural differences in the 220‐loop resulted in a lower location of 226‐Gln, enabling H1 HAs to bind the human receptor analog despite the presence of 226‐Gln (Gamblin et al, 2004). Upon binding to the human receptor, interactions between the receptor and 222‐Lys and 225‐Asp in the 220‐loop are formed, and a hydrogen bond with 190‐Asp (Gamblin et al, 2004; Zhang et al, 2013c).

HA of airborne H5N1 influenza viruses

Imai et al (2012) reported airborne transmission of a pH1N1 reassortant virus that contained the H5 HA of A/Vietnam/1203/04 (VN1203) with amino acid substitutions Asn‐224‐Lys and Gln‐226‐Leu, known to result in a switch in receptor specificity, Asn‐158‐Asp that resulted in the removal of a glycosylation site, and Thr‐318‐Ile in the stalk region which stabilized the trimer structure (Fig 1). The effect of these substitutions on receptor binding and HA structure was investigated in the context of autologous VN1203 and the closely related A/Vietnam/1194/04 (VN1194) HA (Lu et al, 2013; Xiong et al, 2013a). Xiong et al reported a small increase in binding to α2,6‐SA for VN1194 with the mutations described by Imai et al (VN1194mut), similar to what was described in the original work (Imai et al, 2012). Both VN1194mut and VN1203mut displayed a substantially decreased affinity for α2,3‐SA. Overall, the affinity for human and avian receptors of the mutant H5 HA was 5‐ to 10‐fold lower than for human H3 HA (Xiong et al, 2013a). VN1194mut HA acquired the ability to bind α2,6‐SA in the same cis conformation like human H1, H2, and H3 HAs. In particular, the Gln‐226‐Leu substitution facilitated binding to α2,6‐SA, while restricting binding to α2,3‐SA. For both the VN1203mut and VN1194mut HA, the RBS between the 130‐ and 220‐loops had increased in size by approximately 1–1.5 Å. It was further suggested that the glycosylation at residue 158 might sterically block HA binding to cell surface SAs (Lu et al, 2013; Xiong et al, 2013a).

Herfst et al (2012) described fully avian airborne transmissible H5N1 viruses based on A/Indonesia/5/05 (INDO5), of which the HA consistently contained substitution His‐110‐Tyr with a so far unknown effect, Thr‐160‐Ala that removes the same glycosylation site as Asn‐158‐Asp, and Gln‐226‐Leu and Gly‐228‐Ser that were shown to affect receptor specificity (Fig 1). The effect of these substitutions on receptor binding and HA structure was also investigated (INDO5mut). INDO5mut had a approximately ninefold reduced affinity for α2,3‐SA and a > threefold increased affinity for α2,6‐SA compared to wild‐type HA as measured by surface plasmon resonance. Overall, the affinity for avian and human receptors of the INDOmut HA was still relatively low. INDO5 bound LSTc in trans conformation, which is different from human HAs. INDO5mut bound this human receptor analog in cis conformation, in an orientation similar as for pandemic viruses of other virus subtypes. The 226‐Leu created a favorable environment for the non‐polar portion of the human receptor analog and makes a tighter interaction between the RBS and receptor analog. Substitutions Gln‐226‐Leu and Gly‐228‐Ser resulted in a RBS that was approximately 1 Å wider between the 130‐ and 220‐loops compared to that of wild‐type HA, as reported for human HAs (Zhang et al, 2013b).

Collectively, these studies on receptor binding and structure of HA of airborne transmissible H5 viruses thus showed a binding preference for human over avian receptors (although with overall low affinity), widening of the RBS as a consequence of Gln‐226‐Leu, and binding to the human receptor analog LSTc in a similar conformation as shown for human pandemic HAs.

Both airborne H5 HAs and a third one described in Zhang et al lost the same glycosylation site near the RBS that was associated with increased binding affinity, potentially as a result of reduced steric hindrance of interactions between HA and the receptor (Herfst et al, 2012; Imai et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2013d). H5 and H7 influenza viruses from domestic birds generally have more glycosylation sites on the globular head than wild‐bird influenza viruses, which has been associated with reduced binding affinity (Matrosovich et al, 1999). The glycosylation state of HA was previously shown to affect both receptor binding efficiency and immunogenicity (Skehel et al, 1984; Schulze, 1997). During the evolution of influenza viruses, glycosylation sites are removed or introduced, resulting in evasion of host immune responses. In addition, changes in glycosylation may cause functional differences, for example, by affecting the stability of the RBS. Removal of N‐glycans by means of glycosidase F treatment was shown to enhance hemadsorbing activity of HA (Ohuchi et al, 1997). The importance of proper glycosylation is further evident from studies on recombinant soluble HA trimers. Different expression systems can result in differences in the glycosylation of the HA, and the presence of, for example, sialylated N‐glycans on HA can narrow its receptor binding range, which can be increased upon the removal of SA by the addition of exogenous NA (de Vries et al, 2010). Thus, differences in glycosylation of the HA can have major implications for receptor specificity and affinity.

HA of H7N9 influenza viruses

During the outbreak in China in 2013, several residues that are associated with changes in the receptor specificity were observed in HA of the circulating H7N9 viruses. A/Shanghai/1/13 contained 138‐Ser, which was shown previously to enhance binding to α2,6‐SA of pig H5N1 viruses (Nidom et al, 2010). A/Anhui/1/13 and A/Shanghai/2/13 possessed 226‐Leu, which enhances binding to α2,6‐SA in H7 avian influenza viruses, and 186‐Val, which was also reported to influence receptor binding of H7 (Gambaryan et al, 2012; Srinivasan et al, 2013; Yang et al, 2013). However, none of the H7N9 viruses contained 228‐Ser. The H7 genetic lineage from which the H7N9 HA was derived naturally lacks a glycosylation site at the tip of HA, the one that was lost in the airborne H5 viruses.

Multiple research groups have tested the receptor specificity of H7N9 viruses, most of which reported dual receptor specificity (Ramos et al, 2013; van Riel et al, 2013; Shi et al, 2013; Watanabe et al, 2013; Xiong et al, 2013b; Zhou et al, 2013). Overall, A/Anhui/1/2013 was found to bind better to α2,6‐SA than A/Shanghai/1/2013. In glycan arrays, A/Anhui/1/2013 bound to bi‐antennary structures as well as structures containing long N‐acetyllactosamine repeats (Belser et al, 2013a; Watanabe et al, 2013). H7N9 influenza viruses in general had higher affinity for α2,6‐SA compared to other H7 influenza viruses. However, in most studies, the H7N9 viruses maintained preference for avian over human receptors, which is in contrast to the pandemic and airborne transmissible H5 viruses.

The H7N9 HA structure of A/Anhui/1/2013 in complex with human and avian receptors was solved and compared with those of avian H7 HAs. Both LSTc and LSTa were bound to HA in a cis conformation (Shi et al, 2013; Xiong et al, 2013b). LSTc was shown to exit the RBS of H7N9 HA in a different direction from that seen with all pandemic virus HAs and the airborne transmissible H5 HA. The H7 HAs have a subtype‐specific insertion in the 150‐loop, causing this loop to protrude closer to the RBS. The function of this 150‐loop is not yet known (Russell et al, 2006). The Gln‐226‐Leu substitution in H7N9 HA provided a non‐polar‐binding site accommodating the human receptor, and substitution Gly‐186‐Val increased the hydrophobicity of the binding site to further favor interactions with this receptor. The space between the 220‐loop and the 130‐loop was widened in H7N9 HA, but only marginally so, compared to pandemic virus HA and airborne H5 HA (Xiong et al, 2013b).

Virus attachment, replication, pathogenesis, and transmission

Much of the available data on tropism of influenza viruses in the human respiratory tract has been derived from few autopsy studies of fatal cases. Although highly informative to identify the cell types that are infected in vivo and to understand pathogenesis, these data are generally restricted to late phases of the infection. In attempts to compensate for the lack of data in humans, the effect of receptor specificity on tropism, pathogenesis, and transmission has also been studied in a number of animal models like ferrets, pigs, guinea pigs, and mice, and in primary cell lines of human and ferret airway epithelium, and explants of ferret, pig, or human origin (reviewed in Chan et al, 2013a). However, it should be noted that—despite the recent increase in detailed knowledge on fine specificities of HA interacting with different glycans in vitro (see above)—insight on the relevance of interactions between HA and various glycans in vivo is still largely limited to the coarse discrimination between α2,6‐SA and α2,3‐SA alone.

Virus attachment

Virus histochemistry provides a method to investigate and compare attachment patterns of influenza viruses to cells of various tissues from different hosts, without a requirement of detailed prior knowledge on the specific receptors. For virus histochemistry, host tissue sections are incubated with inactivated, FITC‐labeled influenza viruses, much like immunohistochemistry employs FITC‐labeled antibodies. The FITC signals can be enhanced, resulting in a bright red precipitates where the viruses (or antibodies in immunohistochemistry) attach. Attachment patterns of human and avian influenza viruses in the (human) respiratory tract have been shown to be a good indicator for virus cell and tissue tropism. Attachment patterns of a number of avian influenza viruses and human or mutant influenza viruses that are transmissible between humans or ferrets are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Attachment of influenza viruses throughout the human respiratory tract as determined by virus histochemistry

| Nasal turbinates | Trachea | Bronchus | Bronchiole | Alveoli | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | SA | Score | Cell type | Score | Cell type | Score | Cell type | Score | Cell type | Score | Cell type |

| H3N2‐Hu | α2,6 | ++ | C | ++ | C/G | ++ | C/G | ++ | C | + | I |

| H1N1‐Hu | α2,6 | ++ | C/G | ++ | C/G | ++ | C/G | + | C | + | I |

| pH1N1‐Hu | α2,6 | + | C | ++ | C/G | ++ | C/G | ++ | C | + | I |

| H7N7‐Av | α2,3 | +/− | nd | +/− | nd | +/− | nd | + | N | + | II |

| H7N9‐Av | α2,6/α2,3 | ++ | C | + | C | ++ | C/G | ++ | C/N | ++ | I/II |

| H5N1‐Av | α2,3 | − | − | − | + | N | + | II | |||

| H5N1‐Mu | α2,6 | ++ | C/G | + | C/G | ++ | C/G | ++ | C | ++ | I |

Attachment of human (Hu), avian (Av), and avian influenza with mutations (Mu) that change the receptor specificity (SA; van Riel et al, 2007, 2010, 2013; Chutinimitkul et al, 2010b). The mean abundance of cells to which virus attached was scored as follows: −, no attachment; +/−, attachment to rare or few cells; +, attachment to a moderate number of cells; ++, attachment to many cells. The predominant cell type to which the virus attached is indicated as follows: C, ciliated cells; N, non‐ciliated cells; G, goblet cells; Ι, type Ι pneumocytes; ΙΙ, type ΙΙ pneumocytes; nd, not determined.

Broadly speaking, avian influenza viruses with a preference for α2,3‐SA were shown to attach to cells of the lower respiratory tract, to type II pneumocytes and non‐ciliated cells. In contrast, viruses that can transmit between mammals and have a preference for α2,6‐SA were shown to attach to cells of the upper respiratory tract, primarily to ciliated cells. These patterns of virus attachment were in agreement with the receptor distribution in human respiratory tissue as determined upon staining with various lectins (see above).

The dual receptor specificity of the 2013 H7N9 viruses was also reflected by their attachment patterns; H7N9 viruses were shown to attach to both cells in the upper and the lower respiratory tract of humans, and to both type I and II pneumocytes (van Riel et al, 2013; Table 2). Some discrepancies, however, were noted in attachment studies using recombinant HA proteins. Dortmans et al (2013) primarily observed attachment in the submucosal glands of the human upper respiratory tract, and Tharakaraman et al (2013a) only observed limited attachment to the apical epithelial cells of the human trachea. Although influenza viruses that bind α2,3‐SA or α2,6‐SA thus display distinct attachment patterns to cells of the human respiratory tract, small—but potentially important—differences in attachment patterns of viruses with similar receptor specificity have also been observed. For example, H5N1 influenza viruses with the mutations Asn‐182‐Lys or Gln‐226‐Leu and Gly‐228‐Ser both displayed a preference for α2,6‐SA, yet their attachment patterns were not identical; while both viruses attached to nasal turbinate tissue, only H5N1 with Asn‐182‐Lys attached to the trachea of ferrets (Chutinimitkul et al, 2010b). The 1918 H1N1 and 1957 H2N2 pandemic influenza viruses were also both shown to bind α2,6‐SA, yet displayed differences in attachment patterns; whereas H2N2 virus attached to the glycocalyx, goblet cells, and submucosal glands, H1N1 virus showed predominant staining of goblet cells in the human trachea (Jayaraman et al, 2012). The correlation between virus attachment to cells throughout the respiratory tract and receptor preference beyond α2,6‐linkage or α2,3‐linkage alone is not fully understood and warrants further investigation.

Virus replication in primary epithelial cell cultures

Although influenza virus attachment studies have shown great value, not all cells to which influenza viruses can bind are subsequently also infected (Rimmelzwaan et al, 2007), and potentially not all infected cells produce and release infectious virus particles. Moreover, mucus present in the respiratory tract may hamper influenza virus binding and infection. Mucus from the human respiratory tract predominately contains α2,3‐SA receptors (Couceiro et al, 1993; Lamblin & Roussel, 1993), although some α2,6‐SA receptors were also detected (Breg et al, 1987). Incubation of different influenza viruses with a range of receptor specificities revealed that particularly viruses with α2,3 specificity were inhibited by human mucus (Couceiro et al, 1993).

Human and ferret differentiated airway epithelial cells are frequently used to study the effect of mammalian adaptation mutations on infection and replication of influenza viruses. Differentiated airway epithelial cells form a pseudo‐stratified epithelium that closely resembles respiratory epithelium, including the presence of cilia and secretion of mucus. In human differentiated airway epithelial cells, avian influenza viruses infected ciliated cells and to a lesser extent non‐ciliated cells, whereas human influenza viruses infected non‐ciliated cells and to a lesser extent ciliated cells. This is in contrast with virus attachment studies using human tissues without culturing, which revealed binding of human influenza viruses primarily to ciliated cells. Apparently, ciliated cells primarily expressed α2,3‐SA and non‐ciliated cells expressed α2,6‐SA upon culturing (Matrosovich et al, 2004; Thompson et al, 2006; Wan & Perez, 2007), although the presence of α2,6‐SA on ciliated cells has been reported in some studies (Ibricevic et al, 2006; Schrauwen et al, 2013).

In contrast to human differentiated airway epithelial cells, ciliated differentiated airway epithelial cells from ferrets were shown to express α2,6‐SA, while non‐ciliated cells expressed α2,3‐SA. Both human and avian influenza viruses replicated efficiently in differentiated airway epithelial cells from ferrets, but avian viruses had a lower initial infection rate. Using electron microscopy, it was shown that human influenza viruses were predominantly released from the ciliated cells, and release of avian viruses was only sporadically detected and only from non‐ciliated cells, in agreement with the distribution of α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA (Zeng et al, 2013).

Although differentiated airway epithelial cell cultures are quite valuable for various studies, it should thus be noted that cultures of human and ferret origin may behave differently and that receptor expression upon culture may not be representative for the in vivo human respiratory tract tissues.

Virus replication in animal models

Unlike seasonal human influenza viruses, H5N1 viruses generally do not attach to the upper respiratory tract of ferrets or humans (van Riel et al, 2006, 2010; Chutinimitkul et al, 2010b). However, in contrast to the results from attachment studies, H5N1 virus was reported to replicate both in human upper respiratory tract tissue ex vivo (Nicholls et al, 2007b) and in the ferret upper respiratory tract in vivo (Maines et al, 2005, 2006). It is possible that the high virus titers found in the ferret upper respiratory tract are explained in part by virus replication in the olfactory epithelium, which is related to the nervous system and lines a large part of the nasal cavity (Schrauwen et al, 2012). It has also been reported that H5N1 influenza viruses with mutations that change receptor specificity from α2,3‐SA to α2,6‐SA did not replicate more efficiently in the upper respiratory tract of ferrets than their wild‐type counterparts (Wang et al, 2010; Maines et al, 2011; Herfst et al, 2012). This may be explained by a requirement for additional adaptive mutations in HA to accommodate the mutations responsible for α2,6‐SA binding, but more research is needed to identify such “fitness‐enhancing” mutations.

The dual receptor specificity of the H7N9 virus (noted above) was reflected in the attachment patterns to the upper and lower respiratory tract of humans (van Riel et al, 2013). In agreement with receptor specificity and patterns of virus attachment, the H7N9 virus was shown to replicate in both trachea and lung explants (with higher titers in the lung explants) and in human lung cell cultures (Belser et al, 2013a; Knepper et al, 2013; Zhou et al, 2013). In ferrets, the H7N9 virus replicated both in the upper and lower respiratory tract (Kreijtz et al, 2013; Zhang et al, 2013a; Zhu et al, 2013).

Receptor specificity and pathogenesis

The site of influenza virus replication is potentially one of the most critical determinants of pathogenesis. H5N1 viruses were shown to replicate efficiently in the lower respiratory tract in type II pneumocytes (Gu et al, 2007), probably related to the specificity for α2,3‐SA, and contributing to pathogenicity. For pH1N1 virus, amino acid substitution Asp‐225‐Gly that resulted in increased binding to α2,3‐SA was also linked to enhanced disease (Chutinimitkul et al, 2010a; Kilander et al, 2010; Watanabe et al, 2011). Potentially, the dual receptor specificity of the H7N9 virus could be responsible for the severe disease and high mortality observed in humans. Indeed, in various mammalian model systems, the H7N9 virus was shown to be more pathogenic than typical human influenza viruses, which was probably related to efficient virus replication throughout the respiratory tract (Belser et al, 2013a; Kreijtz et al, 2013; Watanabe et al, 2013). However, it should be noted that not all avian influenza viruses (with specificity for α2,3‐SA) are pathogenic in humans; human volunteers that were infected with various avian influenza viruses only displayed mild symptoms (Beare & Webster, 1991), thus emphasizing that other viral (e.g., NS1, polymerase, NA) and host factors (e.g., adaptive and innate immune responses) also critically determine pathogenesis.

Virus transmission

It has been suggested that (i) inefficient virus attachment to (upper) respiratory tissues, (ii) virus replication at only low levels in these tissues, and (iii) poor virus release and aerosolization of virus particles may provide an explanation why influenza viruses with α2,3‐SA preference are not transmitted via the airborne route between mammals (Sorrell et al, 2011). In addition, it was proposed that for a virus that requires α2,3‐SA receptors, a higher dose is needed to infect a new mammalian host, which makes it less likely to transmit (Roberts et al, 2011). Tumpey et al reported that 1918 H1N1 influenza viruses with α2,3‐SA receptor specificity were not transmitted via the airborne route between ferrets, while viruses with dual receptor specificity were transmitted, albeit less efficiently as compared to viruses with α2,6‐SA receptor specificity. Based on these results, it was postulated that a loss of binding to α2,3‐SA is important for airborne transmission (Tumpey et al, 2007). While a loss of binding to α2,3‐SA can result in more efficient airborne transmission, it should be noted that early H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic viruses (that spread efficiently between humans) still had dual receptor specificity (Matrosovich et al, 2000). Both the airborne transmissible H5N1 viruses and the 2013 H7N9 virus displayed dual receptor specificity and were transmitted between ferrets, but for these viruses transmission was less efficient compared to pandemic and seasonal human influenza viruses (Chen et al, 2012; Herfst et al, 2012; Imai et al, 2012; Belser et al, 2013a; Richard et al, 2013; Watanabe et al, 2013; Xu et al, 2013; Zhang et al, 2013a,d; Zhu et al, 2013). The current common belief is that for airborne transmission between humans or ferrets, influenza viruses require human over avian receptor binding preference; viruses with exclusive α2,3‐SA binding are generally not transmitted, viruses with dual receptor specificity are often transmitted inefficiently, while influenza viruses with full‐blown airborne transmission between ferrets or humans generally had a strong α2,6‐SA binding preference. It is important to identify whether a fine specificity in receptor binding beyond α2,3‐SA/α2,6‐SA is required for airborne influenza virus transmission between mammals.

Determinants of airborne transmission beyond receptor specificity

It is clear from airborne transmission studies on pandemic influenza and avian H5N1, H9N2, and H7N9 influenza viruses that a change of receptor specificity is a necessity, but by itself is not enough to result in airborne transmission between mammals. But what are other adaptations of the HA or other viral proteins required for airborne transmission between mammals?

HA stability

Upon virus attachment to SA receptors on the cell surface and internalization into endosomes, a low‐pH‐triggered conformational change in HA mediates fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes to release the virus genome in the cytoplasm. The switch of influenza virus HA from a metastable non‐fusogenic to a stable fusogenic conformation can also be triggered at neutral pH when the HA is exposed to increasing temperature. This conformational change in HA is biochemically indistinguishable from the change triggered by low pH (Haywood & Boyer, 1986; Carr et al, 1997).

Generally, the threshold pH of fusion for HAs of human influenza viruses is lower than that of avian influenza isolates (Galloway et al, 2013). Possibly, the optimal fusion pH of a virus depends on the original host. For avian influenza viruses that replicate in the intestinal tract of birds and are transmitted via surface waters, fusion at a high pH might be more optimal. In contrast, efficient transmission through the air to and from the relatively acidic human nasal cavity as site of replication could require a difference in pH threshold (England et al, 1999; Washington et al, 2000).

Lowering the optimal fusion pH for viruses with an avian H5 HA resulted in enhanced replication in the ferret upper respiratory tract and for some viruses in more efficient contact transmission (Shelton et al, 2013; Zaraket et al, 2013). The HA of the airborne transmissible H5N1 virus described by Imai et al (2012) contained the substitution Thr‐318‐Ile, which is located proximal to the fusion peptide. The wild‐type H5N1 virus (VN1203) had a pH 5.7 fusion threshold and introduction of mutations that change receptor specificity increased the fusion threshold to pH 5.9. However, subsequent introduction of Thr‐318‐Ile reduced the threshold of fusion to pH 5.5. In agreement with this increased pH stability, Thr‐318‐Ile also increased the thermostability of this HA (Imai et al, 2012). Structural studies revealed that the Thr‐318‐Ile mutation stabilized the fusion peptide within the HA monomer (Xiong et al, 2013a). Notably, substitution His‐110‐Tyr in a recombinant protein based on the airborne transmissible virus described by Herfst et al also appeared to increase the stability of the HA at high temperatures (de Vries et al, 2014). His‐110‐Tyr is located at the trimer interface and forms a hydrogen bond with 413‐Asn of the adjacent monomer, thereby stabilizing the trimeric HA protein (Zhang et al, 2013b). Whether this substitution has the same effect on pH stability is still unknown.

The 2013 H7N9 viruses that showed limited airborne transmission between ferrets were shown to have a relatively unstable HA, with conformational changes induced already at relatively low temperatures and a threshold pH for membrane fusion at pH 5.6–5.8 (Richard et al, 2013). Given the observed differences in threshold pH of fusion and thermostability between HAs of human and avian influenza viruses, and the acquired stability mutations in HA of airborne H5N1 viruses, HA stability as an adaptation marker of human influenza viruses clearly warrants further study. It is important to note that the observed changes in pH stability and thermostability may merely be surrogate markers for other stability phenotypes, for example stability in aerosols, in mucus, or upon exposure to air.

HA‐NA balance

As a consequence of the switch in HA receptor binding preference when avian influenza viruses adapt to mammals, subsequent adaptation of NA may be required to maintain an optimal balance between attachment to SA and cleavage of SA. Low NA activity can result in inefficient SA cleavage and subsequent aggregation of virus particles, which can result in low infectious virus titers despite high genome copy numbers (Palese et al, 1974; Liu et al, 1995; de Wit et al, 2010). In contrast, low binding affinity of HA to receptors in combination with high NA activity would likely disturb efficient binding to the host cells. Avian influenza virus NAs specifically cleave α2,3‐SA, whereas human influenza virus NAs cleave both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA. It is thus likely that the NA of avian viruses needs to co‐adapt to the receptor specificity of the HA, for efficient virus attachment and entry, virus release, and potentially transmission (Baum & Paulson, 1991; Kobasa et al, 1999). In this light, it is important to note that several airborne transmissible H5 viruses contained NA derived from human influenza viruses (Chen et al, 2012; Imai et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2013d), but that the fully avian H5N1 viruses described by Herfst et al did not require any changes in the NA gene for airborne transmission (Herfst et al, 2012).

Polymerase proteins

In addition to the HA and NA proteins, the influenza virus polymerase proteins were shown to require adaptation for efficient replication to occur upon transmission from animals to humans (reviewed in Manz et al, 2013). Herfst et al introduced the well‐known adaptive mutation Gly‐627‐Lys in the PB2 gene of an H5N1 virus that subsequently accumulated numerous additional substitutions upon ferret passage in polymerase proteins and nucleoprotein to yield airborne transmissible virus. The Lys at position 627 of PB2 was previously described to contribute to successful replication in mammalian cells at lower temperature (Almond, 1977; Subbarao et al, 1993; Hatta et al, 2001; Massin et al, 2001; Yamada et al, 2010), and airborne transmission between mammals (Steel et al, 2009; Van Hoeven et al, 2009). Efficient replication at lower temperature is thought to be important for adaptation to humans, since the temperature in the human upper respiratory tract is approximately 33°C, which is much lower compared to the temperature in the avian intestinal tract (~41°C), the site of replication of avian viruses.

Amino acid substitutions at positions 590/591 and at position 701 of PB2 were also shown to result in more efficient replication in mammalian cells (Steel et al, 2009; Yamada et al, 2010). Of the H7N9 virus genome sequences available from public databases, 65% contained 627‐Lys, 9% contained 701‐Asn, and 8% contained 591‐Lys, in contrast to avian H7N9 viruses that retained 627‐Glu, 701‐Asp, and 591‐Gln (Chen et al, 2013; Gao et al, 2013b). So far, adaptive changes in PB1, PA, and NP that may contribute to virus adaptation in mammals and airborne transmission have not been investigated in detail, but are urgently warranted.

Challenges and future outlook

Recent work on virus attachment, replication, pathogenesis, and transmission and follow‐up work on structural determinants of HA receptor specificity and stability have shed important new light on influenza virus adaptation to mammalian hosts. Imai et al and Herfst et al described different amino acid substitutions in H5N1 virus HA that represented remarkably similar phenotypic traits leading to airborne virus transmission. Some of these substitutions were also noted in 2013 H7N9 viruses with limited airborne transmissibility, in an airborne H9N2 virus, and in the pandemic viruses of the last century. Some of the substitutions of the laboratory‐derived airborne H5N1 viruses and combinations of such substitutions were already detected in naturally circulating H5N1 viruses (Russell et al, 2012). However, it should be noted that these mutations do not necessarily result in the same phenotype in all H5N1 strains or in strains of other influenza virus subtypes. Moreover, it is possible that there are evolutionary constraints to the accumulation of genetic changes required to yield an airborne transmission phenotype, making the emergence of such viruses possibly an unlikely event (Russell et al, 2012). Further identification of the genetic and phenotypic changes required for host adaptation and transmission of influenza viruses remains an important research topic to facilitate risk assessment for the emergence of zoonotic and pandemic influenza.

In currently circulating strains of clade 2.2.1 H5N1 containing a deletion in the 130‐loop and lacking a glycosylation site at position 160, the substitutions 224‐Asn and 226‐Leu resulted in a switch of receptor specificity (Tharakaraman et al, 2013b). We know that there are many more ways by which H5N1 viruses can adapt to attach to α2,6‐SA. Some natural human H5N1 virus isolates bind to both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA due to substitutions in and around the RBS (Yamada et al, 2006; Crusat et al, 2013). In addition, mutational analyses of H5 HA based on analogies with other influenza virus subtypes identified several substitutions that caused a switch in receptor specificity and virus attachment to upper respiratory tract tissues of humans. Although none of these human virus isolates and mutant viruses were capable of airborne transmission between mammals (Maines et al, 2006; Stevens et al, 2006b, 2008; Chutinimitkul et al, 2010b; Paulson & de Vries, 2013), it is clear that there are multiple ways by which circulating H5N1 strains can change receptor specificity and adapt to replication in mammals.

Yang et al (2013) have shown that introduction of substitution 228‐Ser in H7N9 HA that already had 226‐Leu resulted in overall increased binding to α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA, but not in a switch in receptor preference. Based on structural studies, it was anticipated that Gly‐228‐Ser would optimize interactions with both α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA. Gly‐228‐Ser resulted in increased binding of the H7N9 HA to the apical surface of tracheal and alveolar tissues of humans (Tharakaraman et al, 2013a). At present, it is unclear whether other amino acid substitutions would further fine‐tune the receptor binding preference of the H7N9 viruses and could potentially increase the airborne transmissibility under laboratory or natural conditions.

Although our knowledge of receptor specificity and its implications for transmission and pathogenesis has improved since the initial characterization of the influenza virus RBS, there are still many unknowns. The lack of knowledge of which cells are the primary target of airborne transmissible viruses and the type and distribution of receptors they express hampers the interpretation of receptor binding data and structural studies. Major current interest is focused on receptor binding assays such as glycan arrays, solid‐phase binding assays, and agglutination assays using modified erythrocytes. But without knowledge on which receptors are relevant for influenza virus attachment, replication, and transmission in vivo, it is impossible to assess which binding assays best represent influenza virus attachment in the respiratory tract. As a consequence, studies should focus more on identification of the relevant functional glycans in humans and animal models. The possibility that a plethora of receptors in the human respiratory tract can be utilized for the attachment of influenza viruses and are relevant for replication and transmission should be considered. Based on studies of the glycome of human and animal hosts, it is clear that a large number of glycan structures are not represented on glycan arrays (Walther et al, 2013). A potential way forward would be the use of shotgun glycan arrays that employ receptors of relevant tissues and cells of the human respiratory tract rather than random synthetic glycans (Yu et al, 2012). At present, such studies are limited since they generally employ all glycans expressed in the respiratory tract rather than just those receptors expressed on relevant cell types at the apical surface of the respiratory tract that are accessible upon influenza virus infection. Future work should clearly focus on improvement of the methods available in glycobiology. Similarly, X‐ray crystal structures of human and avian receptor analogs in complex with HAs of human and influenza viruses have revealed crucial structural determinants for binding to α2,3‐SA and α2,6‐SA receptor analogs. But potentially these structural studies could also be complemented with influenza HAs in complex with a variety of sialylated glycan structures, to increase understanding of the structural determinants of HA receptor binding.

There is a clear need for phenotypic assays to predict which animal influenza viruses can infect humans and transmit between humans. One major unknown is to what extent the transmissibility of influenza viruses in ferret and guinea pig transmission models can be extrapolated to humans. Although thus far there has been good correspondence between the transmissibility of avian and human influenza viruses between humans and the ferret transmission model, it is not certain that all viruses that transmit between ferrets will also transmit between humans. It is also not clear how the ferret and guinea pig models compare with respect to airborne transmission of animal influenza viruses. Better understanding about the behavior of airborne transmissible viruses in vitro may allow replacement of some animal models with in vitro methods and contribute to reduction, replacement, and refinement in animal experiments (Russell & Burch, 1959; Belser et al, 2013b). In addition, such phenotypical assays may complement ongoing surveillance studies to identify biological traits of circulating influenza viruses that could trigger immediate action or attention. So far, when data obtained with attachment studies, infection studies using primary epithelial cell lines explants, and animal studies were compared, the correspondence was not always obvious, and therefore, more work in this field is also needed. While it may never be feasible to perfectly predict the adaptation of animal influenza viruses to humans, increased knowledge from animal studies, in vitro assays, and structural analyses collectively will almost certainly improve such predictions.

Author contributions

MG and RAMF wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by EU FP7 programs ANTIGONE and EMPERIE, NIAID/NIH contract HHSN266200700010C, and an Intra European Marie Curie Fellowship (PIEF‐GA‐2009‐237505). We thank C.H. Hokke, B. Mänz, D.F. Burke, E.J.A. Schrauwen, D. van Riel, E. de Vries, C.A. de Haan, and S. Herfst for critically reading the manuscript and their helpful comments.

EMBO J (2014) 33, 823–841

References

- Ablan S, Rawat SS, Blumenthal R, Puri A (2001) Entry of influenza virus into a glycosphingolipid‐deficient mouse skin fibroblast cell line. Arch Virol 146: 2227–2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aich U, Beckley N, Shriver Z, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Hobbie S, Sasisekharan R (2011) Glycomics‐based analysis of chicken red blood cells provides insight into the selectivity of the viral agglutination assay. FEBS J 278: 1699–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond JW (1977) A single gene determines the host range of influenza virus. Nature 270: 617–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AC, Karamanska R, Busch MG, Dell A, Olsen CW, Haslam SM (2010) Glycan analysis and influenza A virus infection of primary swine respiratory epithelial cells: the importance of NeuAc{alpha}2‐6 glycans. J Biol Chem 285: 34016–34026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum LG, Paulson JC (1991) The N2 neuraminidase of human influenza virus has acquired a substrate specificity complementary to the hemagglutinin receptor specificity. Virology 180: 10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare AS, Webster RG (1991) Replication of avian influenza viruses in humans. Arch Virol 119: 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Blixt O, Chen LM, Pappas C, Maines TR, Van Hoeven N, Donis R, Busch J, McBride R, Paulson JC, Katz JM, Tumpey TM (2008) Contemporary North American influenza H7 viruses possess human receptor specificity: Implications for virus transmissibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7558–7563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, Katz JM, Tumpey TM (2013a) Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature 501: 556–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Maines TR, Katz JM, Tumpey TM (2013b) Considerations regarding appropriate sample size for conducting ferret transmission experiments. Future Microbiol 8: 961–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breg J, Van Halbeek H, Vliegenthart JF, Lamblin G, Houvenaghel MC, Roussel P (1987) Structure of sialyl‐oligosaccharides isolated from bronchial mucus glycoproteins of patients (blood group O) suffering from cystic fibrosis. Eur J Biochem 168: 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhausen I, Schachter H, Stanley P (2009) O‐GalNAc glycans In Essentials of Glycobiology, Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME. (eds), 2nd edn, Chapter 9. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CM, Chaudhry C, Kim PS (1997) Influenza hemagglutinin is spring‐loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14306–14313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) Update: influenza activity–United States, 2003–04 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53: 284–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RW, Chan MC, Nicholls JM, Malik Peiris JS (2013a) Use of ex vivo and in vitro cultures of the human respiratory tract to study the tropism and host responses of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) and other influenza viruses. Virus Res 178: 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RW, Karamanska R, Van Poucke S, Van Reeth K, Chan IW, Chan MC, Dell A, Peiris JS, Haslam SM, Guan Y, Nicholls JM (2013b) Infection of swine ex vivo tissues with avian viruses including H7N9 and correlation with glycomic analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 7: 1269–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Blixt O, Stevens J, Lipatov AS, Davis CT, Collins BE, Cox NJ, Paulson JC, Donis RO (2012) In vitro evolution of H5N1 avian influenza virus toward human‐type receptor specificity. Virology 422: 105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liang W, Yang S, Wu N, Gao H, Sheng J, Yao H, Wo J, Fang Q, Cui D, Li Y, Yao X, Zhang Y, Wu H, Zheng S, Diao H, Xia S, Chan KH, Tsoi HW, Teng JL et al (2013) Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. Lancet 381: 1916–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs RA, Palma AS, Wharton S, Matrosovich T, Liu Y, Chai W, Campanero‐Rhodes MA, Zhang Y, Eickmann M, Kiso M, Hay A, Matrosovich M, Feizi T (2009) Receptor‐binding specificity of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus determined by carbohydrate microarray. Nat Biotechnol 27: 797–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou HH, Takematsu H, Diaz S, Iber J, Nickerson E, Wright KL, Muchmore EA, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Varki A (1998) A mutation in human CMP‐sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo‐Pan divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 11751–11756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu VC, Whittaker GR (2004) Influenza virus entry and infection require host cell N‐linked glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 18153–18158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutinimitkul S, Herfst S, Steel J, Lowen AC, Ye J, van Riel D, Schrauwen EJ, Bestebroer TM, Koel B, Burke DF, Sutherland‐Cash KH, Whittleston CS, Russell CA, Wales DJ, Smith DJ, Jonges M, Meijer A, Koopmans M, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T et al (2010a) Virulence‐associated substitution D222G in the hemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus affects receptor binding. J Virol 84: 11802–11813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutinimitkul S, van Riel D, Munster VJ, van den Brand JM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, de Wit E (2010b) In vitro assessment of attachment pattern and replication efficiency of H5N1 influenza A viruses with altered receptor specificity. J Virol 84: 6825–6833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor RJ, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG, Paulson JC (1994) Receptor specificity in human, avian, and equine H2 and H3 influenza virus isolates. Virology 205: 17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T, Chaves AJ, Valle R, Darji A, van Riel D, Kuiken T, Majo N, Ramis A (2012) Distribution patterns of influenza virus receptors and viral attachment patterns in the respiratory and intestinal tracts of seven avian species. Vet Res 43: 28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couceiro JN, Paulson JC, Baum LG (1993) Influenza virus strains selectively recognize sialyloligosaccharides on human respiratory epithelium; the role of the host cell in selection of hemagglutinin receptor specificity. Virus Res 29: 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusat M, Liu J, Palma AS, Childs RA, Liu Y, Wharton SA, Lin YP, Coombs PJ, Martin SR, Matrosovich M, Chen Z, Stevens DJ, Hien VM, Thanh TT, le Nhu NT, Nguyet LA, Ha do Q, van Doorn HR, Hien TT, Conradt HS et al (2013) Changes in the hemagglutinin of H5N1 viruses during human infection–influence on receptor binding. Virology 447: 326–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dortmans JC, Dekkers J, Wickramasinghe IN, Verheije MH, Rottier PJ, van Kuppeveld FJ, de Vries E, de Haan CA (2013) Adaptation of novel H7N9 influenza A virus to human receptors. Sci Rep 3: 3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England RJ, Homer JJ, Knight LC, Ell SR (1999) Nasal pH measurement: a reliable and repeatable parameter. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 24: 67–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D, Rimmelzwaan GF, Olsen B, Osterhaus AD (2005) Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black‐headed gulls. J Virol 79: 2814–2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Schutten M, Van Doornum GJ, Koch G, Bosman A, Koopmans M, Osterhaus AD (2004) Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1356–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca M, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW (2013) Expression and distribution of sialic acid influenza virus receptors in wild birds. Avian Pathol 42: 60–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway SE, Reed ML, Russell CJ, Steinhauer DA (2013) Influenza HA subtypes demonstrate divergent phenotypes for cleavage activation and pH of fusion: implications for host range and adaptation. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambaryan A, Yamnikova S, Lvov D, Tuzikov A, Chinarev A, Pazynina G, Webster R, Matrosovich M, Bovin N (2005) Receptor specificity of influenza viruses from birds and mammals: new data on involvement of the inner fragments of the carbohydrate chain. Virology 334: 276–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambaryan AS, Matrosovich TY, Philipp J, Munster VJ, Fouchier RA, Cattoli G, Capua I, Krauss SL, Webster RG, Banks J, Bovin NV, Klenk HD, Matrosovich MN (2012) Receptor‐binding profiles of H7 subtype influenza viruses in different host species. J Virol 86: 4370–4379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambaryan AS, Tuzikov AB, Piskarev VE, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, Robertson JS, Bovin NV, Matrosovich MN (1997) Specification of receptor‐binding phenotypes of influenza virus isolates from different hosts using synthetic sialylglycopolymers: non‐egg‐adapted human H1 and H3 influenza A and influenza B viruses share a common high binding affinity for 6′‐sialyl(N‐acetyllactosamine). Virology 232: 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamblin SJ, Haire LF, Russell RJ, Stevens DJ, Xiao B, Ha Y, Vasisht N, Steinhauer DA, Daniels RS, Elliot A, Wiley DC, Skehel JJ (2004) The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science 303: 1838–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ (2010) Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 285: 28403–28409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HN, Lu HZ, Cao B, Du B, Shang H, Gan JH, Lu SH, Yang YD, Fang Q, Shen YZ, Xi XM, Gu Q, Zhou XM, Qu HP, Yan Z, Li FM, Zhao W, Gao ZC, Wang GF, Ruan LX et al (2013a) Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med 368: 2277–2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, Chen J, Jie Z, Qiu H, Xu K, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu W, Gao Z, Xiang N, Shen Y, He Z, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Yang Y et al (2013b) Human infection with a novel avian‐origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 368: 1888–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler C, Jarvis DL (2011) Effective glycoanalysis with Maackia amurensis lectins requires a clear understanding of their binding specificities. Glycobiology 21: 988–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser L, Stevens J, Zamarin D, Wilson IA, Garcia‐Sastre A, Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Palese P (2005) A single amino acid substitution in 1918 influenza virus hemagglutinin changes receptor binding specificity. J Virol 79: 11533–11536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk A (1957) Neuraminidase: the specific enzyme of influenza virus and Vibrio cholerae. Biochim Biophys Acta 23: 645–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Xie Z, Gao Z, Liu J, Korteweg C, Ye J, Lau LT, Lu J, Zhang B, McNutt MA, Lu M, Anderson VM, Gong E, Yu AC, Lipkin WI (2007) H5N1 infection of the respiratory tract and beyond: a molecular pathology study. Lancet 370: 1137–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Webster RG (1999) Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza viruses: were they the donors of the “internal” genes of H5N1 viruses in Hong Kong? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 9363–9367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC (2001) X‐ray structures of H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus hemagglutinins bound to avian and human receptor analogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11181–11186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW (2013) Thematic minireview series on glycobiology and extracellular matrices: glycan functions pervade biology at all levels. J Biol Chem 288: 6903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y (2001) Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science 293: 1840–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood AM, Boyer BP (1986) Time and temperature dependence of influenza virus membrane fusion at neutral pH. J Gen Virol 67(Pt 12): 2813–2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA (2012) Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science 336: 1534–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GK (1941) The agglutination of red cells by allantoic fluid of chick embryos infected with influenza virus. Science 94: 22–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibricevic A, Pekosz A, Walter MJ, Newby C, Battaile JT, Brown EG, Holtzman MJ, Brody SL (2006) Influenza virus receptor specificity and cell tropism in mouse and human airway epithelial cells. J Virol 80: 7469–7480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Nakajo N, Sakiyama H, Hirabayashi Y (1994) A mouse B16 melanoma mutant deficient in glycolipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 2703–2707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]