Abstract

Biological network inference is a major challenge in systems biology. Traditional correlation-based network analysis results in too many spurious edges since correlation cannot distinguish between direct and indirect associations. To address this issue, Gaussian graphical models (GGM) were proposed and have been widely used. Though they can significantly reduce the number of spurious edges, GGM are insufficient to uncover a network structure faithfully due to the fact that they only consider the full order partial correlation. Moreover, when the number of samples is smaller than the number of variables, further technique based on sparse regularization needs to be incorporated into GGM to solve the singular covariance inversion problem. In this paper, we propose an efficient and mathematically solid algorithm that infers biological networks by computing low order partial correlation (LOPC) up to the second order. The bias introduced by the low order constraint is minimal compared to the more reliable approximation of the network structure achieved. In addition, the algorithm is suitable for a dataset with small sample size but large number of variables. Simulation results show that LOPC yields far less spurious edges and works well under various conditions commonly seen in practice. The application to a real metabolomics dataset further validates the performance of LOPC and suggests its potential power in detecting novel biomarkers for complex disease.

Keywords: Systems biology, undirected network inference, correlation, Gaussian graphical models, low order partial correlation, biomarker discovery

1. Introduction

Systems biology is a rapidly developing field that gives insights that genes and proteins do not work in isolation in complex diseases such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease and diabetes. To better understand the mechanisms of these diseases, different omic studies (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) need to be assembled to take advantage of the complementary information and to investigate how they complement each other. One major challenge in this field is the problem of inferring biological networks, such as gene co-expression network, protein-protein interaction network or metabolic network using high-throughput omic data.

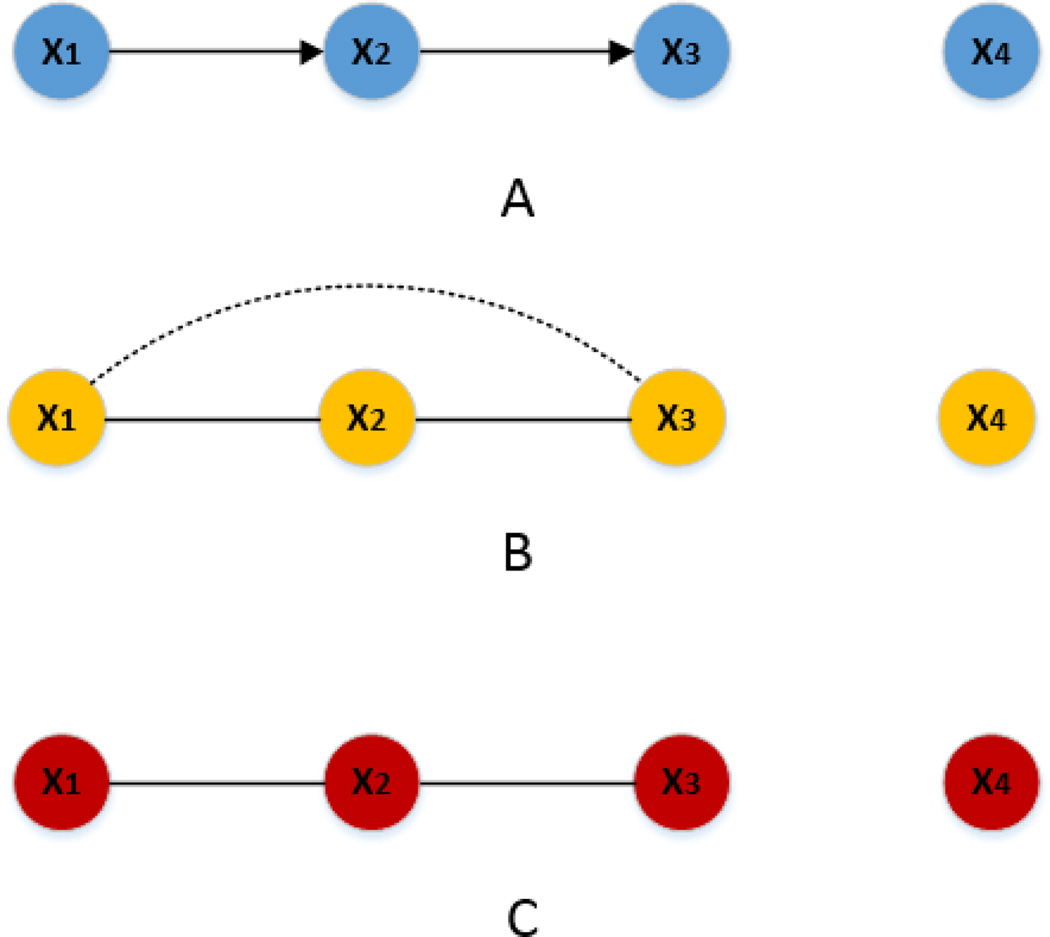

Generally speaking, network inference methods can be divided into two groups depending on whether the resulting networks are directed graphs or undirected graphs. Bayesian network (BN) [1] is the most popular method for directed network inference. BN is a probabilistic graphical model where nodes represent genes, proteins or metabolites and edges denote conditional dependence relationships. It models the biological networks as directed acyclic graphs. However, cyclic network structures, such as feedback loops, are ubiquitous in biological systems and are, in many cases, associated with specific biological properties [2]. Considering this, the assumption of acyclic structure behind BN is limiting. In comparison, undirected network inference methods model the biological networks as undirected graphs thereby circumventing the problems of inferring cyclic network structures. One conventional method for undirected network inference is based on correlation [3–5], but correlation confounds direct and indirect associations. While direct association represents the pure association between two variables, indirect association indicates the induced association due to other variables. For example, Figure 1B illustrates that given three variables (x1, x2 and x3), a strong correlation between x1 and x2 as well as x2 and x3 (direct association) may lead to a relatively weak but still significantly large correlation between x1 and x3 (indirect association). As a result, when the number of nodes is large, the resulting correlation-based network will yield too many spurious edges due to indirect associations.

Figure 1.

Correlation confouds direct and indirect associations while partial correlation does not. (A) The true network from the model. (B) The network inferred based on correlation. The dot line represents the spurious edge due to the indirect association. (C) The network inferred based on GGM.

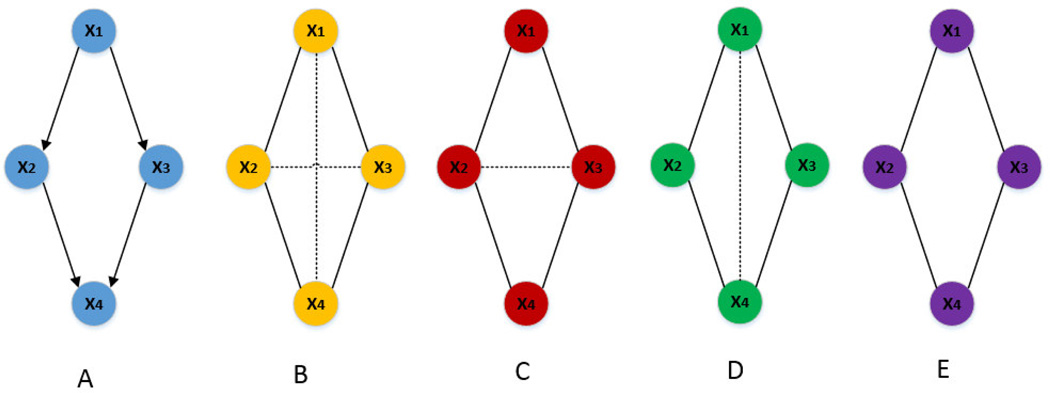

Partial correlation measures the correlation between two variables after their linear dependence on other variables is removed. It can distinguish between direct and indirect associations. The formal definition of the partial correlation between x1 and x2 given a set of other variables X+ = {x3, x4, …, xn} is the correlation between the residuals resulting from the linear regression of x1 with X+ and that of x2 with X+, respectively. One widely used method for undirected network inference with partial correlation is Gaussian graphical models (GGM) [6]. For an undirected graph with p nodes, GGM calculate the partial correlation coefficients between each pair of nodes conditional on all other p-2 nodes. However, in order to obtain the exact undirected network for p variables, one needs to calculate from zero-th order (simply correlation) up to (p-2)-th order (full order) partial correlation [7]. By only considering the full order partial correlation, it is insufficient for GGM to uncover the network structure faithfully as seen in Figure 2C. This is because two nodes may be conditionally independent when only conditional on a subset of other nodes while conditionally dependent when conditional on all remaining ones [8]. Furthermore, when the number of samples is far smaller than the number of variables, a common case in omic studies, GGM face the difficulty of inverting a singular covariance matrix. Techniques based on sparse regularization such as graphical lasso offer a solution to address this problem within the framework of GGM [9]. In comparison, methods based on low order partial correlation (LOPC) have been proposed [8, 10–12]. Low order partial correlation between two variables is obtained only conditional on a subset rather than all other variables. If only zero-th order and first order partial correlations are considered, the resulting undirected graph is called 0–1 graph [13]. 0–1 graph has the advantage that it can be efficiently estimated from small sample-size data, but it fails to infer complex network structure (e.g., cyclic structures) as seen in Figure 2D. The reason is that in Figure 2A, x1 can reach x4 through either x2 or x3, so only conditioning on one of them (0–1 graph only calculates up to the first order partial correlation) is not enough to remove the indirect association between x1 and x4. In [8], de la Fuente et al. proposed to calculate up to the second order partial correlation to take into account more complex network structure while trying to keep the computational complexity still manageable. However, calculating the second order partial correlation for regular microarray experiments involving several thousands of variables is computationally intractable. This limits the application of method proposed by de la Fuente et al. to infer large biological networks. In addition, their method sets correlation threshold empirically without statistical support.

Figure 2.

Cyclic structure networks inferred based on correlation, GGM, 0–1 graph and LOPC. (A) The true network from the model. (B) Network inferred based on correlation: the dot lines represent the spurious edges. (C) Network inferred based on GGM: by only conditioning on the (p-2)-th order (i.e., second order in this model), it is insufficient to uncover the relationships between variables faithfully. (D) Network inferred based on 0–1 graph (up to first order): by only conditioning on up to first order, the indirect association between x1 and x4 cannot be removed since there are two paths from x1 to x4 either through x2 or x3. (E) Network inferred based on LOPC (up to second order): the connections in A are faithfully uncovered.

In this paper, we propose an efficient and mathematically sound algorithm to infer biological networks by calculating partial correlation from zero-th order up to the second order. For a given dataset with p variables, we first compute the zero-th order and first order partial correlation for each pair of variables. Then, we calculate the second order partial correlation only in cases in which both the zero-th order and first order partial correlations are significantly different from zero. With this step, the efficiency of LOPC is largely increased since it excludes most of the possible pairs before calculating the second order partial correlation. Furthermore, we use Fisher’s z transformation to create test statistics to set a reasonable threshold. To take into account multiple testing, we control the False Discovery Rate (FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Simulation results show that LOPC works well under various conditions commonly seen in real applications and the spurious edges (i.e., false positives) for the inferred network are significantly reduced. We then apply LOPC on a real metabolomics dataset, the result validates the performance of LOPC and shows its potential in discovering novel biomarkers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we discuss different undirected network inference methods based on correlation, GGM and LOPC. Also, we introduce test statistics for correlation and partial correlation methods (GGM and LOPC). Then, we propose an efficient algorithm, LPOC. The input, output, tools and databases involved are summarized. Section 3 presents two simulation datasets and a real metabolomics dataset to evaluate the performance of LOPC. The above undirected network inference methods are compared and the results are discussed. Finally, Section 4 summarizes our work and presents possible extensions.

2. Methods

2.1 Undirected network construction methods

Consider p random variables x1, x2, …, xp, denoted by X={x1, x2, …, xp}, that represent either metabolite levels or expressions of proteins or genes. Suppose the covariance matrix of X is Σ with the correlation coefficient between xi and xj defined as:

| (1) |

In a correlation-based network, xi and xj are considered to be connected if and only if (iff) ρij≠0 (i.e., its estimate rij is significantly different from zero).

One common criticism for the above correlation-based network is that it yields too many spurious edges since correlation confounds direct and indirect associations. Let’s consider an example where X={x1, x2, x2, x4} and the relationships between x1, x2, x3 and x4 are modeled as x1=s+ε1, x2=λ· x1+ε2, x3=μ· x2+ ε3, x4=ε4 assuming s ~N(0,σs2), denoting the signal; ε1, ε2, ε3, ε4 ~N(0, σn2), denoting the independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) noise; signal and noise are independent; λ, μ are non-zero constants. Figure 1A represents the above relationships and the arrow directions are assigned manually to represent causality. In this model, the relationships between x1 and x2, x2 and x3 are direct associations while x1 and x3 are indirectly related. Figure 1B shows that the undirected network inferred based on correlation confounds direct and indirect associations, thus leading to a spurious edge or false positive (i.e., the edge between x1 and x3).

In contrast, GGM remove the linear effect of all remaining p-2 variables when calculating the partial correlation coefficient between two variables conditional on all other variables. Suppose X follows a multivariate Gaussian distribution, R and Q are two subsets of X where R={xi, xj} and Q=X\R. The conditional covariance matrix of R given Q can be computed as follows as long as ΣQQ is nonsingular:

| (2) |

where the covariance matrix of X is .

Similarly, the precision matrix of X (the inverse of Σ) can be represented as:

| (3) |

In Eq. 3, ΩRR = (ΣRR − ΣRQΣQQ−1ΣQR)−1 [14].

Suppose , then from Eq. 2, the conditional covariance matrix ΣR|Q can be obtained as:

| (4) |

Under a Gaussian distribution assumption, partial correlation and conditional correlation are equivalent. A proof involving three variables is shown in the Appendix. For a more general proof, one can refer to [15, 16].

Once the precision matrix is known, the partial correlation coefficient between xi and xj conditional on all other variables can be computed as:

| (5) |

In a GGM-based network, xi and xj are considered to be connected iff ρij·Q≠0 (i.e., its estimate rij․Q is significantly different from zero).

By removing the effect of all other variables, GGM can distinguish between direct and indirect associations as seen in Figure 1C. However, it requires that the covariance matrix be full rank for a well-defined matrix inversion, so the sample size should be at least as large as the number of variables. This poses a challenge for most omic datasets, which typically involve thousands of variables but much less number of samples. Furthermore, even when the sample size is large enough, GGM could lead to unreliable result as seen in Figure 2C since it only considers the (p-2)-th order partial correlation.

Rather than conditioning on all other variables, LOPC conditions on only a few of them. The order of the partial correlation coefficient is determined by the number of variables it conditions on. The advantage of using LOPC relies on a recursive equation (i.e., a higher order partial correlation coefficient can be computed from its preceding order) [17].

For X={x1, x2, x3, x4} modeled in Figure 1, without loss of generality, we assume σs2=σn2=1 and e1=0, then the covariance matrix Σ is:

| (6) |

From Eq. 2, the conditional covariance matrix of {x1, x2} given x3 is:

| (7) |

Since partial correlation is equivalent to conditional correlation under Gaussian distribution, the first order partial correlation coefficient between x1 and x2 conditional on x3 can be computed from Eq. 7:

| (8) |

When the zero-th order partial correlation coefficients ρ12, ρ13, ρ23 are computed from Eq. 6 and compared with Eq. 8, the following relationship exists between zero-th order and the first order partial correlation coefficients:

| (9) |

Eq. 9 can be generalized so that higher order partial correlation coefficient can be calculated from its preceding order. For example, similar equation exists between the first order and the second order partial correlation coefficients:

| (10) |

Theoretically, in order to obtain the exact undirected graph for p variables, one needs to potentially calculate the partial correlations from zero-th order up to the (p-2)-th order [7]. Correlation considers only the zero-th order; GGM consider only the (p-2)-th order. It was previously reported that neither of them is sufficient to uncover the conditionally independent relationships between variables [8]. Surprisingly, though the idea behind LOPC is simple, it can serve as a good approximation to the true network as seen in Figure 2. In addition, LOPC has the advantage of working well when the sample size is small and the number of variable is large.

If only zero-th order and first order partial correlations are considered, the resulting network is called a 0–1 graph. The network is constructed based on the following rule: the edge between nodes xi and xj is connected iff all rij and rij·k are significantly away from zero, where k considers each possible xk in X\{xi, xj}.

Similarly, if we calculate up to the second order partial correlation, the resulting network is constructed based on the rule that the edge between nodes xi and xj is connected iff all rij, rij·k and rij·kq are significantly different from zero, where k and q correspond to every possible xk and xq in X\{xi, xj}.

2.2 Test statistics

The test statistics for non-zero correlation coefficient is and follows a t-distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom under the null hypothesis.

In contrast, the test statistics for non-zero partial correlation can be calculated using the Fisher’s z transformation [18]:

| (11) |

where Q̃ corresponds to the elements of X\{xi, xj} conditional upon and |Q̃| is the order of the partial correlation.

For a zero partial correlation coefficient with sample size equal to n, z is approximately normally distributed with zero mean and variance. Given a partial correlation coefficient, the two-sided p-value is:

| (12) |

2.3 Algorithm

The proposed algorithm contains four parts:

calculate the zero-th, first and second order partial correlation coefficients;

calculate test statistics and corresponding p-values to evaluate the null hypothesis that the corresponding partial correlation coefficient is zero;

calculate adjusted p-values for multiple testing correction;

construct the network.

Among the four steps, most of the computation time is spent on calculating the second order partial correlation coefficient rij·kq since one needs to consider all possible xk, xq in X\{xi, xj}. It was previously suggested that the distribution of connections in metabolic, regulatory and protein-protein interaction networks tends to follow a power law [19, 20]. Thus, the resulting networks are very sparse.

Here, we present an efficient algorithm taking advantage of this sparsity property of biological networks. Instead of calculating the second order partial correlation coefficients rij·kq for all possible xi, xj, we only calculate those whose corresponding zero-th and first order partial correlation coefficients are significantly different from zero. Since the true biological networks are sparse, this step can exclude most of the possible spurious edges before calculating the second order partial correlation. As a result, LOPC can dramatically reduce the computational burden.

The detailed algorithm is outlined below:

| Algorithm LOPC | |

|---|---|

| 1: | Zero-th order partial correlation: |

| 2: | for each pair (xi, xj) do |

| 3: | Calculate an estimate of the zero-th order partial correlation coefficient rij; |

| 4: | Construct the test statistic for rij and compute the corresponding p-value p(rij); |

| 5: | Compute the multiple testing adjusted p-value for the zeroth order partial correlation coefficient p̄(xij) across all pairs. |

| 6: | end for |

| 7: | First order partial correlation: |

| 8: | for each pair (xi, xj) do |

| 9: | Calculate estimates of the first order partial correlation coefficients rij·k for all possible xk ∈ X/{xi, xj}; |

| 10: | Select the maximum in terms of absolute value as r̂ij·k; |

| 11: | Construct test statistics for r̂ij·k using Fisher’s z transformation and compute corresponding p-value p(r̂ij·k); |

| 12: | Compute the multiple test adjusted p-values for the first order partial correlation coefficient p̄(r̂ij·k) across all pairs. |

| 13: | end for |

| 14: | Second order partial correlation: |

| 15: | for each pair (xi, xj) do |

| 16: | if max {p̄(rij), p̄(r̂ij·k)} < 0.05 then |

| 17: | Proceed to compute the second order partial correlation: |

| 18: | Calculate estimates of the second order partial correlation coefficients rij·kq for all possible xk, xq ∈ X/ {xi, xj}; |

| 19: | Select the maximum in terms of absolute value as r̂ij·kq; |

| 20: | Compute the multiple test adjusted p-values for the second order partial correlation coefficient p̄ (r̂ij·kq) across all pairs. |

| 21: | else |

| 22: | Do not need to compute the second order partial correlation: |

| 23: | Set p̄(r̂ij·kq) to be 1. |

| 24: | end if |

| 25: | end for |

| 26: | Connect xi and xj iff p̄(r̂ij·kq) < 0.05. |

2.4 Summary

LOPC is an efficient algorithm for constructing a simplified undirected network that captures the direct associations between variables (genes, proteins, and metabolites) based on high-throughput omics data. The input, output, tools and databases involved are listed below.

Input: The input of the proposed algorithm is a p × n matrix with p variables (genes, proteins, or metabolites) and n samples. The elements in the matrix either represent the expression level of the corresponding genes and proteins or the intensity of the associated metabolites.

Output: The output of the algorithm is a p × p matrix, also known as adjacent matrix, along with a p × p weight matrix. The elements of the adjacent matrix are either 1 or 0, indicating whether there exists a connection between two variables or not. The weight matrix includes the value of the second order partial correlation between different pairs.

Tools: Tools such as Matlab and Cytoscape are used for implementing the algorithm and visualizing the network, respectively.

Databases: While no databases are involved in the algorithm, databases such as DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp), Reactome (http://www.reactome.org/), and KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) are often used to look into the resulting networks for functional interpretation and pathway analysis.

3. Results and discussion

This section presents two numerical simulations (A and B) to infer undirected network based on correlation, GGM, 0–1 graph, and LOPC, as well as one real application of LOPC on a metabolomics dataset.

3.1 Analysis on simulated data

In simulation A, we consider an example where variables X={x1, x2, x3, x4} form a cyclic structure as shown in Figure 2A. The relationships between x1, x2, x3, x4 were modeled as: x1=s+ε1, x2=λ·x1+ε2, x3=μ·x1+ε3, x4=α·x2+β·x3+ε4 assuming s ~N(0,σs2), denoting the signal; ε1, ε2, ε3, ε4 ~N(0, σn2), denoting the i.i.d. noise; signal and noise are independent; λ, μ, α, β are non-zero constants. Without loss of generality, we set σs2=1, σn2=0.01 and λ=μ=α=β=1. The resulting covariance matrix for X is:

| (13) |

We generated dataset fromN(0,Σ)with a sample size of n=50 and inferred networks based on correlation, GGM, 0–1 graph and LOPC as seen in Figure 2.

The correlation, partial correlation for each pair of variables and the corresponding adjusted p-values are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Correlation, partial correlation and p-values for each edge

| Edge | Correlation | GGM | 0–1 graph | LOPC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| x1x2 | 0.994 | 9.00E-47 | 0.533 | 9.00E-04 | 0.278 | 5.00E-03 | 0.533 | 9.00E-04 |

| x1x3 | 0.996 | 9.00E-51 | 0.658 | 4.00E-06 | 0.518 | 2.00E-07 | 0.658 | 4.00E-06 |

| x1x4 | 0.995 | 1.00E-50 | −0.257 | 0.774 | 0.33 | 8.00E-03 | −0.257 | 0.774 |

| x2x3 | 0.991 | 5.00E-45 | −0.543 | 7.00E-04 | 0.148 | 8.50E-01 | 0 | 1 |

| x2x4 | 0.997 | 4.00E-53 | 0.798 | 1.00E-10 | 0.704 | 0 | 0.798 | 1.00E-10 |

| x3x4 | 0.997 | 7.00E-53 | 0.754 | 6.00E-09 | 0.634 | 2.00E-12 | 0.754 | 6.00E-09 |

In Figures 2B and 2C, we see that both correlation and GGM-based networks yield spurious edges. This is because correlation confounds direct and indirect associations, while GGM are insufficient to uncover the network structure faithfully in this model by only considering the (p-2)-th order partial correlation. In fact, from the perspective of probabilistic graphical models [21], x1 is a common ancestor of x2 and x3, while x4 is a causal descendent of x2 and x3. Since conditioning on any common causal descendent would introduce a correlation between two variables, there is a dependence estimated between x2 and x3 by conditioning on both x1 and x4 using GGM.

The resulting networks based on 0–1 graph and LOPC are shown in Figures. 2D and 2E, respectively. For 0–1 graph, since there are multiple paths from x1 to x4 either through x2 or x3. By only calculating up to the first order partial correlation, it is insufficient to remove the indirect association between x1 and x4. However, when we calculate up to the second order partial correlation, the cyclic structure can be faithfully recovered. In fact, Figure 2E can be viewed as the result of merging Figures. 2B, 2C and 2D together and only keeping common edges.

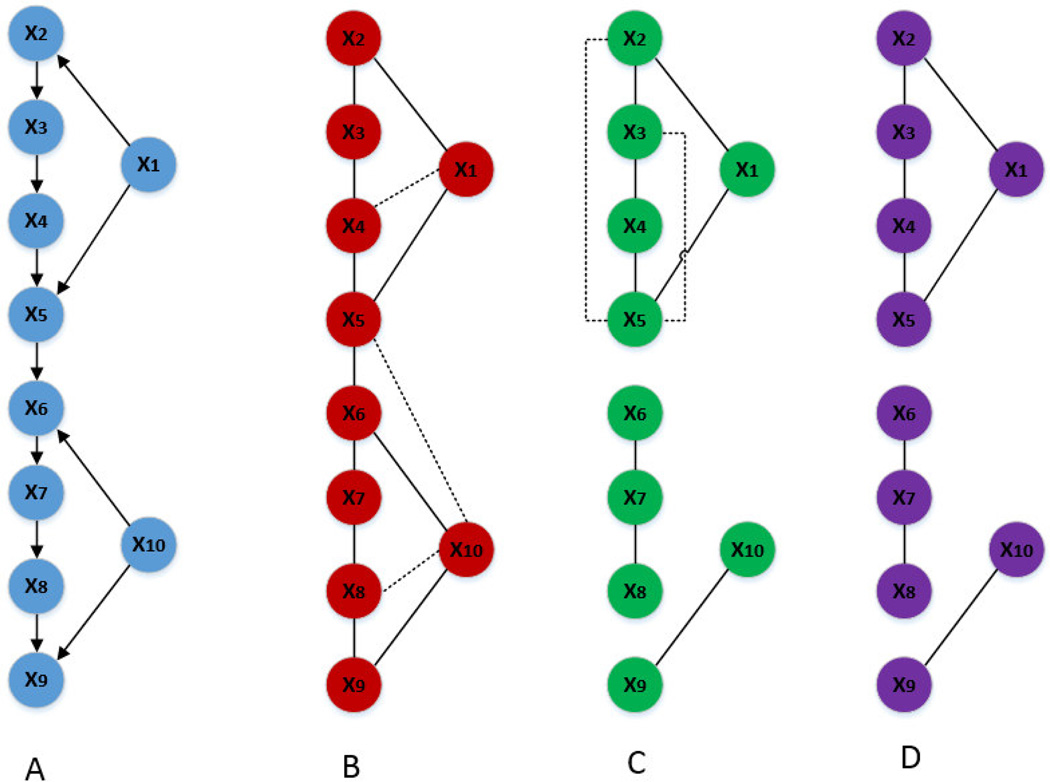

In simulation B, we consider a more complex structure where ten variables X={x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7, x8, x9, x10} were involved and their relationships were modeled as: x1=s1+ε1, x10=s2+ε10, x2=λ1·x1+ε2, x3=α1·x2+ε3, x4=α2·x3+ε4, x5=α3·x4+λ2·x1+ε5, x6=α4·x5+μ1·x10+ε6, x7=α5·x6+ε7, x8=α6·x7+ε8, x9=α7·x8+μ2·x10+ε9 with s1, s2 ~N(0,σs2), denoting the signal; ε1, ε2, …, ε10 ~N(0, σn2), denoting the i.i.d. noise; signal and noise are independent; λ1, λ2, μ1, μ2, α1, α2, …, α7 are non-zero constants. The network structure is shown in Figure 3A. In this network, x1 and x10 can be interpreted as regulators while x2 to x9 represent genes, proteins or metabolites being regulated. Correspondingly, λ1, λ2, μ1, μ2 denote the strength of the regulation. Without loss of generality, we set σs2=1, σn2=0.01, all the coefficients (i.e., λ1, λ2, μ1, μ2, α1, α2, …, α7) to be 1. The resulting covariance matrix for X is seen in Eq. 14.

Figure 3.

Complex structure networks inferred based on GGM, 0–1 graph and LOPC. (A) The true network from the model. (B) Network inferred based on GGM: the dot lines represent the spurious edges. (C) Network inferred based on 0–1 graph (up to first order): by only conditioning on up to first order, the resulting inferred network has similar number of spurious edges (false positives) as that from GGM but has several missed edges (false negatives). (D) Network inferrred based on LOPC (up to second order): while the missed edges are inherited from 0–1 graph, calculating up to the second order successfully removes spurious edges in the inferred network.

We generated dataset fromN(0,Σ)with a sample size of n=50 and inferred networks based on correlation, GGM, 0–1 graph and LOPC. For the correlation-based network, the number of spurious edges (false positives) increases dramatically with nearly every possible variable pair being connected. In Figures 3B to 3D, we show the inferred networks based on GGM, 0–1 graph and LOPC.

| (14) |

As shown in Figure 3B, GGM-based network yields a few false positives. This is because GGM only considers the (p-2)-th order partial correlation. As seen in Figure 3C, the 0–1 graph yields similar number of false positives compared with GGM-based network but starts to have missing edges (false negatives). The network inferred with LOPC (Figure 3D) also has false negatives, but calculating up to the second order removes all the false positives.

Using a similar model, we generated 100 simulation datasets for varying number of variables and sample sizes and calculated the mean of false positives and false negatives for each method as shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Mean of false positives and false negatives for varying number of variables and sample sizes

| Variable Number |

Sample Size |

Correlation | GGM | 0–1 graph | LOPC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP | FN | FP | FN | FP | FN | FP | FN | ||

| 10 | 50 | 28.78 | 0.11 | 2.93 | 0.23 | 1.95 | 3.08 | 0 | 3.31 |

| 20 | 50 | 54.91 | 1.42 | 1.29 | 15.06 | 1.4 | 10.84 | 0.09 | 15.98 |

| 100 | 57.19 | 0.41 | 5.28 | 2.17 | 3.64 | 6.37 | 0 | 7.47 | |

| 50 | 51 | 142.55 | 2.09 | 7.33 | 54.61 | 6.29 | 20.9 | 0.42 | 32.57 |

| 100 | 145.85 | 0.33 | 13.73 | 9.98 | 9.73 | 15.21 | 0.21 | 16.86 | |

| 100 | 101 | 299.51 | 0.47 | 0 | 109.98 | 19.62 | 30.43 | 1.56 | 33.34 |

| 200 | 299.44 | 0 | 39.16 | 0.78 | 20.04 | 29.48 | 0.83 | 29.87 | |

| 500 | 501 | 1491.71 | 0 | 0 | 550 | 89.78 | 151.32 | 7.31 | 171.38 |

| 1000 | 1495.25 | 0 | 150.78 | 10.34 | 114.25 | 99.75 | 1.35 | 105.19 | |

| 1000 | 1001 | 2990.13 | 0 | 0 | 1100 | 181.27 | 271.78 | 13.77 | 301.13 |

Generally speaking, we expect LOPC to lead to far less number of false positives compared to GGM and 0–1 graph with a possible drawback of selecting a few more false negatives. In real application, this is desirable since one would usually prefer to be confident about the existence of edges already detected, though some edges might be missed. As shown in Table 2, when the sample size is slightly larger than the number of variables, LOPC works well, whereas GGM’s performance begins to decline due to the difficulty of inverting singular matrix. To address this, further technique such as graphical lasso has been incorporated into GGM [9].

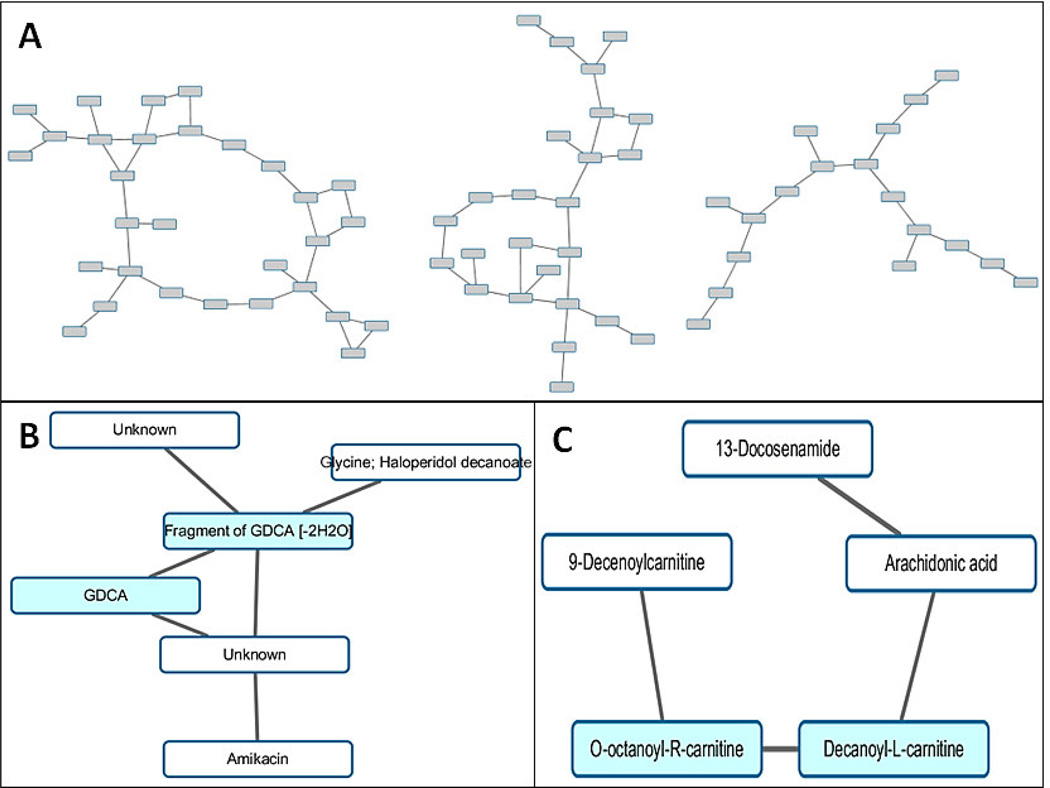

3.2 Application to real data

In this section, we applied LOPC on a real untargeted metabolomics dataset previously collected and analyzed by our group for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) biomarker discovery study [22]. The data were acquired by analysis of sera from 40 HCC cases and 50 patients with liver cirrhosis using liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Following preprocessing, a data matrix was obtained with 984 input variables - larger than the sample size 90. In [22], we identified 32 metabolites with intensities significantly different between the HCC cases and cirrhotic controls.

Rather than looking into each statistically significant metabolite, in this paper, we generated undirected network using LOPC after normalization of the preprocessed data matrix. The aim of the normalization is to bring the intensities of the metabolites in both cases and controls to a comparable level. The resulting networks are depicted in Figure 4A. We then mapped the 32 statistically significant metabolites onto Figure 4A and extracted functional modules which contained multiple metabolites. Two interesting functional modules are shown in Figures 4B and 4C, respectively, with blue nodes representing the metabolites and white nodes representing non-significant ones. Due to the limitation in metabolite identification, some of the nodes have been assigned multiple putative IDs (e.g., Glycine; Haloperidol decanoate) or have no IDs (unknowns).We see that metabolites connecting with each other tend to be involved in the same chemical reaction and have similar functionalities. The extracted functional modules may help identify other non-significant metabolites that might be missing from the statistical analysis due to subtle differences in ion intensities.

Figure 4.

Undirected network and functional modules inferred from real data by LOPC. (A) Undirected network encoding the direct associations between different nodes (B–C) Functional modules extracted from the undirected network. Blue nodes represent the candidate biomarkers previously reported. White nodes represent the non-significant ones.

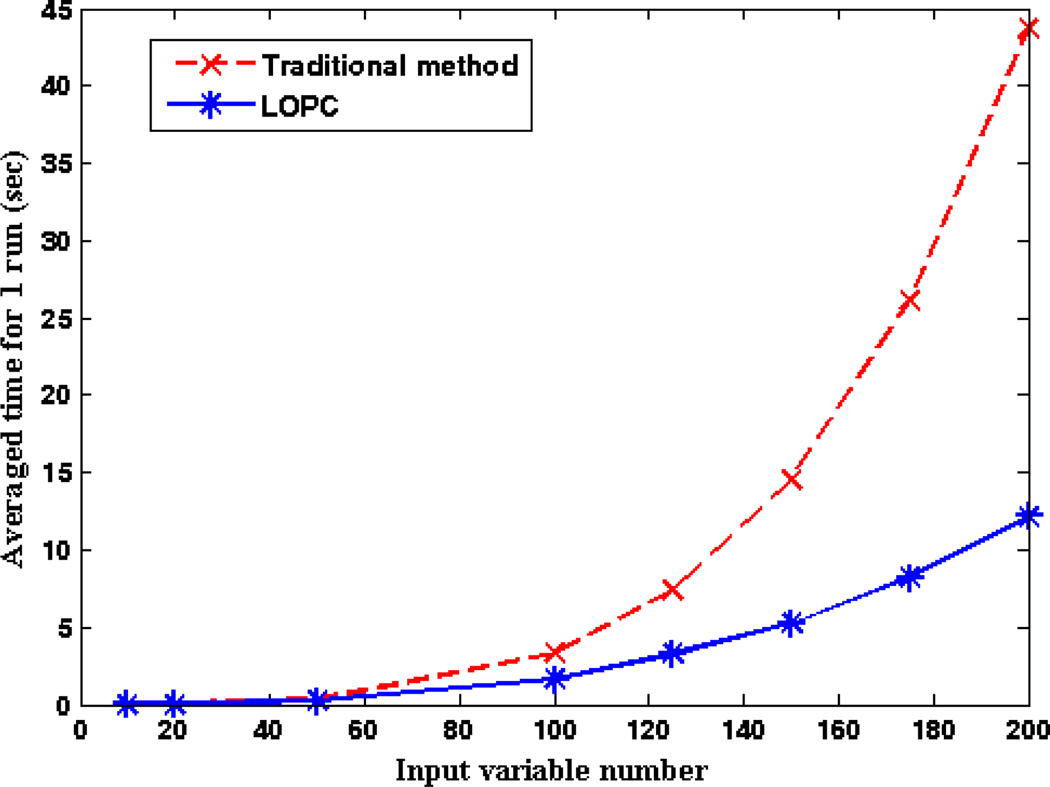

Finally, we evaluated the efficiency of LOPC by randomly sampling various numbers of metabolites from the above dataset to generate 100 undirected networks. We compared the averaged run-time between LOPC and the traditional method to calculate up to the second order partial correlation. While the traditional method calculates the 0th, 1st, and 2nd order partial correlations, LOPC evaluates the outcome of the 1st order partial correlation to determine whether or not the calculation of the 2nd order partial correlation is needed. As shown in Figure 5, when the input variable number increases beyond 50, LOPC starts to become more efficient than traditional method. With an input variable number of 200, LOPC can be as 4 times fast as the traditional method. The run-time comparison was performed using a PC with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-2600 CPU @ 3.4GHz and 16.0 GB RAM.

Figure 5.

Run-time comparison between LOPC and the traditional method in calculating up to the second order partial correlation.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose an efficient algorithm, LOPC, to infer biological networks by calculating up to the second order partial correlation. Compared with other undirected network inference methods (correlation, GGM, and 0–1 graph), LOPC offers better solution for inferring networks with less spurious edges (false positives). It also has the advantage of handling well cases that involve a large number of variables but a small sample size. These properties make LOPC a promising alternative to infer from omic datasets relevant gene co-expression, protein-protein interaction and metabolic networks, which may give insights into the mechanisms of complex diseases. A real application on metabolomics dataset validates the performance of LOPC and shows its potential in discovering novel biomarkers. Future research will focus on incorporating prior knowledge from the existing database and causal information from time course data to build directed network.

TABLE 3.

Correlation, partial correlation and p-values for each edge.

| Edge | Correlation | GGM | 0–1 graph | LOPC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| x1x2 | 0.994 | 9.00E-47 | 0.533 | 9.00E-04 | 0.278 | 5.00E-03 | 0.533 | 9.00E-04 |

| x1x3 | 0.996 | 9.00E-51 | 0.658 | 4.00E-06 | 0.518 | 2.00E-07 | 0.658 | 4.00E-06 |

| x1x4 | 0.995 | 1.00E-50 | −0.257 | 0.774 | 0.33 | 8.00E-03 | −0.257 | 0.774 |

| x2x3 | 0.991 | 5.00E-45 | −0.543 | 7.00E-04 | 0.148 | 8.50E-01 | 0 | 1 |

| x2x4 | 0.997 | 4.00E-53 | 0.798 | 1.00E-10 | 0.704 | 0 | 0.798 | 1.00E-10 |

| x3x4 | 0.997 | 7.00E-53 | 0.754 | 6.00E-09 | 0.634 | 2.00E-12 | 0.754 | 6.00E-09 |

TABLE 4.

Mean of false positives and false negatives for varying number of variables and sample sizes.

| Variable Number |

Sample Size |

Correlation | GGM | 0–1 graph | LOPC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP | FN | FP | FN | FP | FN | FP | FN | ||

| 10 | 50 | 28.78 | 0.11 | 2.93 | 0.23 | 1.95 | 3.08 | 0 | 3.31 |

| 20 | 50 | 54.91 | 1.42 | 1.29 | 15.06 | 1.4 | 10.84 | 0.09 | 15.98 |

| 100 | 57.19 | 0.41 | 5.28 | 2.17 | 3.64 | 6.37 | 0 | 7.47 | |

| 50 | 51 | 142.55 | 2.09 | 7.33 | 54.61 | 6.29 | 20.9 | 0.42 | 32.57 |

| 100 | 145.85 | 0.33 | 13.73 | 9.98 | 9.73 | 15.21 | 0.21 | 16.86 | |

| 100 | 101 | 299.51 | 0.47 | 0 | 109.98 | 19.62 | 30.43 | 1.56 | 33.34 |

| 200 | 299.44 | 0 | 39.16 | 0.78 | 20.04 | 29.48 | 0.83 | 29.87 | |

| 500 | 501 | 1491.71 | 0 | 0 | 550 | 89.78 | 151.32 | 7.31 | 171.38 |

| 1000 | 1495.25 | 0 | 150.78 | 10.34 | 114.25 | 99.75 | 1.35 | 105.19 | |

| 1000 | 1001 | 2990.13 | 0 | 0 | 1100 | 181.27 | 271.78 | 13.77 | 301.13 |

Acknowledgments

This work is in part supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA143420 and R01GM086746 awarded to HWR.

Appendix

Conditional independence relationship is crucial for network inference. Here, we prove the equality of partial correlation and conditional correlation involving three variables under Gaussian assumption so that we can use partial correlation to infer conditional independence relationships between nodes and build a network.

By definition, the partial correlation coefficient between x and y conditional on z (rxy·z) is obtained by first regressing x on z and y on z separately and then calculating the correlation between the residuals of the models for x and y:

| (15) |

| (16-1) |

| (16-2) |

where ε̂x,ε̂y are the residuals of x and y after regressing on z; â, b̂, ĉ, d̂ are regression coefficients.

Conditional correlation coefficient between x and y given z (rxy|z) is defined as:

| (17) |

where Ex|z, Ey|z and Ex,y|z denote expectations of the marginal and joint distribution of x and y conditional on z.

To show the relationship between partial correlation and conditional correlation, we consider the following case of x=b0+b1·z+a and y=d0+d1·z+c, where b0, b1, d0 and d1 are constants, x, y, z, a and c are random variables. Under this assumption, the conditional correlation between x and y given z is reduced to:

| (18) |

From Eq. (4), the partial correlation equals to conditional correlation. To be more general, these two correlations are the same when the conditional variance and covariance of x and y given z are free of z [15, 16]. The above condition is satisfied in normal distribution.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedman N, Linial M, Nachman I, Pe'er D. Using bayesian networks to analyze expression data. Journal of Computational Biology. 2000;7:601–620. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alon U. Network motifs: Theory and experimental approaches. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butte AJ, Tamayo P, Slonim D, Golub TR, Kohane IS. Discovering functional relationships between RNA expression and chemotherapeutic susceptibility using relevance networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:12182–12186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220392197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steuer R. Review: On the analysis and interpretation of correlations in metabolomic data. Brief Bioinform. 2006;7:151–158. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart JM, Segal E, Koller D, Kim SK. A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science. 2003;302:249–255. doi: 10.1126/science.1087447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schafer J, Strimmer K. Learning large-scale graphical gaussian models from genomic data. Science of Complex Networks from Biology to the Internet and WWW. 2005;776:263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shipley B. Cause and Correlation in Biology: A User's Guide to Path Analysis. Structural Equations and Causal Inference. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Fuente A, Bing N, Hoeschele I, Mendes P. Discovery of meaningful associations in genomic data using partial correlation coefficients. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3565–3574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics. 2008;9:432–441. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magwene PM, Kim J. Estimating genomic coexpression networks using first-order conditional independence. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wille A, Bühlmann P. Low-order conditional independence graphs for inferring genetic networks. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2006;5.1 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reverter A, Chan EK. Combining partial correlation and an information theory approach to the reversed engineering of gene co-expression networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2491–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Campos LM, Huete JF. A new approach for learning belief networks using independence criteria. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning. 2000;24:11–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauritzen SL. Appendix B. linear algebra and random vectors, in Graphical Models. Oxford University Press, USA; 1996. pp. 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrance A. On conditional and partial correlation. The American Statistician. 1976;30:146–149. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baba K, Shibata R, Sibuya M. Partial correlation and conditional correlation as measures of conditional independence. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Statistics. 2004;46:657–664. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson TW. An Introduction to Multivariate Statistical Analysis. 3rd ed. Wiley-Interscience, NJ; 2003. 2.5.3. Some formulas for partial correlations; pp. 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher RA. Frequency distribution of the values of the correlation coefficient in samples from an indefinitely large population. Biometrika. 1915;10:507–521. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabási A. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000;407:651–654. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslov S, Sneppen K. Specificity and stability in topology of protein networks. Science. 2002;296:910–913. doi: 10.1126/science.1065103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards D. Introduction to Graphical Modelling. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao JF, Varghese RS, Zhou B, Nezami Ranjbar MR, Zhao Y, Tsai T, Di Poto C, Wang J, Goerlitz D, Luo Y. LC–MS based serum metabolomics for identification of hepatocellular carcinoma biomarkers in egyptian cohort. Journal of Proteome Research. 2012;11:5914–5923. doi: 10.1021/pr300673x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]